Abstract

Background

The increased incidence of early gastric cancer in several Asian countries has been associated with an increase in gastric stump carcinoma (GSC) following gastric cancer surgery. The clinicopathological characteristics of GSC remain unclear because of the limited number of patients with GSC.

Methods

The clinicopathological characteristics, including the 5-year survival rate of patients with GSC following distal gastrectomy (167 patients), were compared with those of patients with primary upper third gastric cancer (PGC; 755 patients). The clinicopathological characteristics of patients with GSC were also compared between those who had initial surgery for gastric cancer (GSC-M group, 78 patients) and for benign lesions (GSC-B group, 89 patients).

Results

The GSC-B group has a greater male/female ratio (13.8 vs. 3.1) and a longer interval between initial gastrectomy and surgery for GSC (31.0 vs. 9.4 years) than the GSC-M group. The 5-year survival rate was not significantly different between the GSC-B group (49.0 %) and the GSC-M group (59.3 %, P = 0.359). A comparison between the GSC group and the PGC group revealed a poorer 5-year survival rate for the GSC group (53.6 %) than the PGC group (78.3 %, P < 0.001), and the same trend was observed even after stratification by the pathological stage.

Conclusions

Stump carcinoma arises earlier following gastrectomy for malignant disease than for benign disease. The prognosis was poor in patients with GSC compared to those with PGC. Early detection of GSC is necessary and an appropriate follow-up program should be established.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The incidence of gastric stump carcinoma (GSC) has been reported as 1.1–3.0 % following distal gastrectomy.1–3 GSC following gastrectomy for benign lesions, such as gastric or duodenal ulcers, has been documented.2,4–6 Recently, an increased incidence of early gastric cancer has been observed, especially in several Asian countries, and has resulted in long survival times after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. This has been associated with an increased incidence of GSC following gastric cancer surgery.7–10 Regular follow-up checks after gastrectomy for gastric cancer can also help to detect GSC.11

Although GSC following both distal gastrectomy and primary upper third gastric cancer (PGC) originates in the same area (the upper third of the stomach), the metastatic pattern can be different because patients with GSC have a different lymphatic flow to PGC patients as a result of the initial surgery.12,13 Moreover, intra-abdominal adhesions in patients with GSC may affect the quality of the lymph node dissection and complete local tumor control. Although the clinicopathological characteristics of both GSC and PGC have been compared previously, this aspect still remains controversial, partly because of the limited number of patients with GSC.4,12,14–17

Clinicopathological features and survival may differ between patients with GSC following gastric cancer surgery (GSC-M) and those following gastrectomy for benign lesions (GSC-B). This occurs because both the primary operation and the background of the patients are generally different. GSC-M cases are diagnosed at an earlier stage7 and with a shorter interval between the initial surgery and surgery for GSC than occurs for GSC-B.7–9,11,16,18,19 However, the number of patients in each group was also limited in previous studies.

The aim of the present study was to clarify the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with GSC including their long-term outcome.

Methods

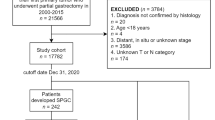

During the period from 1980 to 2007, a total of 8,102 patients underwent surgery for gastric cancer at the Cancer Institute Hospital, Japan. Of these, 239 patients had a stump carcinoma. Patients were excluded if the initial surgery was not a distal gastrectomy (18 proximal gastrectomies and 10 segmental gastrectomies) or if they did not undergo gastrectomy for GSC (bypass or exploratory laparotomy, 12 patients). Six patients with incomplete initial surgical details were also excluded from the study. In addition, if the duration between primary gastrectomy and operation for GSC was shorter than 5 years, we carefully checked the patient’s medical chart in detail. If the surgeon recorded that the surgery was not for GSC but for recurrent PGC or for a positive margin at the primary gastrectomy, patients were also excluded from the study (26 patients). The remaining 167 patients were included in the study and classified as the GSC group.

During the same period from1980 to 2007, 755 patients underwent gastrectomy for PGC at the Cancer Institute Hospital and the characteristics of these patients (PGC group) were compared with those of the GSC group. In this study, the PGC group was characterized by tumors confined to the upper third of the stomach that did not infiltrate the middle or lower third.

Clinical, pathological, and surgical findings for the PGC group were collected retrospectively from our prospectively acquired database. These were collected retrospectively for the GSC group from each patient’s medical chart. Pathological T, N, and M stages were assigned according to the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) classification, 6th edition.20

Comparison of Clinicopathological Characteristics and Survival Curves Between Groups

Clinicopathological characteristics were compared between the GSC-M group (78 patients), the GSC-B group (89 patients), and the PGC group (755 patients). In the present study, age, gender, surgical procedure, pathological findings (tumor depth [pT], number of metastatic lymph nodes [pN], and pathological stage [pStage]), and 5-year survival rate were compared among the three groups.

The reconstruction method of the initial gastrectomy, tumor location (anastomotic site, whole stomach, and other site), early surgical outcomes (operation time and bleeding), and interval between surgeries were also compared between the GSC-M and GSC-B groups.

Statistical Analyses

All continuous variables are presented as the median (range). Statistical analyses were performed using the chi-square test, Student’s t test, and Mann–Whitney test. The 5-year survival rate was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test was used to compare the groups. Patients whose surgery was noncurative were excluded from the survival analysis. The Bonferroni test was used during multiple comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Clinicopathological Comparison Among the Three Groups

Patient clinicopathological characteristics are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The male/female ratio in the GSC-B (13.8) group was higher than that in either the GSC-M group (3.1) or the PGC group (3.4). The GSC (GSC-M and GSC-B) group had a significantly higher proportion of advanced disease compared to the PGC group. There was no significant difference in the macroscopic types, pathological tumor depth, lymph nodes status, pathological stage, and curability of the surgery between the GSC-M and GSC-B groups.

Comparison Between GSC-M and GSC-B Groups

The preferred reconstruction method in the GSC-M group was Billroth I (76 %), whereas Billroth II was preferred in the GSC-B group (74 %) (Table 3). Tumors identified in the stump were most frequently located at the anastomotic site in the GSC-B group, whereas they were located at non-anastomotic sites in the GSC-M group. In addition, the operation time was found to be significantly longer in the GSC-M group than in the GSC-B group, but blood loss was similar between the two groups.

The interval between the initial gastrectomy and surgery for GSC was shorter in the GSC-M group (9.4 years) than in the GSC-B group (31.0 years, P < 0.001). A total of 21 patients (27 %) in the GSC-M group were diagnosed with GSC within 5 years of their initial surgery and 22 patients (28 %) within 5 to 10 years. By comparison, only 5 (6 %) of the 89 patients in the GSC-B group were diagnosed with GSC within 10 years of their initial surgery.

Long-Term Outcome of GSC and PGC

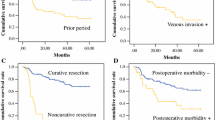

The survival curves for the GSC-M and GSC-B groups are shown in Fig. 1. The 5-year survival rates for patients in the GSC-M and GSC-B groups were 59.3 and 49.0 %, respectively, and the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.359). The results were the same even after stratification by the tumor depth, nodal status, or pathological stage.

The 5-year survival rate was significantly better in the PGC group (78.3 %) than in the GSC group (53.6 %, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). A comparison within each pathological stage also showed a trend of better 5-year survival rate in the PGC group than in the GSC group: stage I (90.6 vs. 79.0 %, P = 0.083), stage II (68.8 vs. 47.4 %, P = 0.114), stage III (50.0 vs. 28.4 %, P = 0.028), and stage IV (11.1 vs. 5.3 %, P = 0.115) (Fig. 3a–d). The difference between groups was statistically significant only in those with stage III disease.

Survival curves of patients following curative gastrectomy stratified by pathological stage (gray PGC, black GSC). a Stage I, the 5-year survival rate was 90.6 % in the PGC group and 79.0 % in the GSC group (P = 0.083), b stage II, the 5-year survival rate was 68.8 % in the PGC group and 47.4 % in the GSC group (P = 0.114), c stage III, the 5-year survival rate was 50.0 % in the PGC group and 28.4 % in the GSC group (P = 0.028), d stage IV, the 5-year survival rate was 11.1 % in the PGC group and 5.3 % in the GSC group (P = 0.115)

Discussion

The standard treatment for peptic ulcer disease in previous decades was surgery that included a gastrectomy.21 Recent advances in peptic ulcer therapy, including specific treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection, have decreased the prevalence of affected individuals for whom gastrectomy is indicated. It is likely that the incidence of GSC following gastrectomy for benign diseases will decrease in the future. On the other hand, the incidence of early gastric cancer with long-term survivability is increasing, especially in several Asian countries.22 As a result, GSC following gastric cancer surgery has been increasing overall.7,10

A number of investigations have previously been conducted on GSC. Some of them focused on GSC following gastrectomy for gastric cancer.7,8,11,16,18 Ohashi et al. reported the largest number (n = 108) of such cases, including those treated with endoscopic mucosal resection (n = 25).7 The present study only dealt with surgical patients with GSC whose initial gastrectomy had been for benign disease (89 patients) and gastric cancer (78 patients). Therefore, this study includes the largest number of GSC patients treated in a single institute.

The male/female ratio of patients with PGC usually ranges between 2 and 4.22–24 In the present study, the male/female ratio was 3.1 in the GSC-M group, 3.4 in the PGC group, and 13.8 in the GSC-B group. Most previous reports have found a higher ratio in GSC-B patients, ranging between 6.0 and 12.0,8,16,19,25–28 which may result from a higher rate of ulcer surgery in males.21,29

The interval between the initial gastrectomy and surgery for GSC was far longer in the GSC-B group than in the GSC-M group, whereas the ages at GSC surgery were similar. These observations have been reported in previous studies and most likely result from the different ages of the initial gastrectomy in the two groups: GSC-M, 54 years and GSC-B, 32 years.16

The 5-year survival rate of patients with GSC following curative resection has been reported as 22.2–57 %,12–14,19,27,30 which is significantly different from the rate for PGC.4,12,14,27 In this study, we found a significantly worse 5-year survival rate in patients with GSC, partly because the GSC group included more advanced cases. However, the PGC tended to have better survival even in the same stage, particularly in stage III. Morita et al. reported that the long-term outcome of patients with T3 disease was poorer in patients with GSC than in those with PGC.7 Sasako et al. and Imada et al. reported that the pattern of lymph node metastasis was different between stump and primary cancers probably because the lymphatic flow had been totally altered after lesser curvature lymphadenectomy at the initial surgery.12,13 This altered lymphatic stream could affect the long-term survival of GSC patients, particularly those with advanced stage.

Early detection of disease is essential to improve the poor 5-year survival rate of patients with GSC. Endoscopic surveillance is mandatory for the GSC-M group because the stump mucosa has a higher carcinogenic potential than the stomach of the general population.3 The optimal period of surveillance has not been determined, but the reported median intervals between the initial and second surgeries (7.8–11.7 years) should be considered.8,11,18,19 The period of surveillance for recurrence after gastric cancer surgery usually finishes at 5 years, but we propose that gastric stump surveillance should continue longer. We do not propose a surveillance program for patients who underwent distal gastrectomy for benign lesions, as a result of this study.

An et al.16 conducted an analyses similar to ours comparing the clinicopathological characteristics among patients with GSC-M, GSC-B, and PGC. They, too, found a better overall 5-year survival rate in patients with PGC (62.9 %) than in those with GSC (53.7 %), but the difference was not statistically significant presumably due to the limited number of patients with GSC (38 patients). In the present study, to the best of our knowledge, the largest number of patients was included in a single institute having enough power for statistical analysis.

In conclusion, clinicopathological features were similar between the GSC-M and GSC-B groups, except for a higher male/female ratio and a longer interval between the two surgeries in GSC-B group. The prognosis was poor in patients with GSC, particularly those with an advanced stage, compared to those with PGC. Early detection of GSC is necessary to improve the poor long-term outcome of this disease. It should be noted that many stump carcinomas can arise more than 10 years after the initial gastrectomy for cancer. Therefore, endoscopic surveillance for stump cancer should be considered separately from the usual follow-up checks for cancer recurrence after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer.

References

Viste A, Bjornestad E, Opheim P, et al. Risk of carcinoma following gastric operations for benign disease. A historical cohort study of 3470 patients. Lancet 1986; 2(8505):502–5.

Toftgaard C. Gastric cancer after peptic ulcer surgery. A historic prospective cohort investigation. Ann Surg 1989; 210(2):159–64.

Nozaki I, Nasu J, Kubo Y, et al. Risk factors for metachronous gastric cancer in the remnant stomach after early cancer surgery. World J Surg 2010; 34(7):1548–54.

Mezhir JJ, Gonen M, Ammori JB, et al. Treatment and outcome of patients with gastric remnant cancer after resection for peptic ulcer disease. Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18(3):670–6.

Tersmette AC, Offerhaus GJ, Tersmette KW, et al. Meta-analysis of the risk of gastric stump cancer: detection of high risk patient subsets for stomach cancer after remote partial gastrectomy for benign conditions. Cancer Res 1990; 50(20):6486–9.

Kodera Y, Yamamura Y, Torii A, et al. Gastric stump carcinoma after partial gastrectomy for benign gastric lesion: what is feasible as standard surgical treatment? J Surg Oncol 1996; 63(2):119–24.

Ohashi M, Katai H, Fukagawa T, et al. Cancer of the gastric stump following distal gastrectomy for cancer. Br J Surg 2007; 94(1):92–5.

Kaminishi M, Shimizu N, Yamaguchi H, et al. Different carcinogenesis in the gastric remnant after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Cancer 1996; 77(8 Suppl):1646–53.

Kaneko K, Kondo H, Saito D, et al. Early gastric stump cancer following distal gastrectomy. Gut 1998; 43(3):342–4.

Fujita T, Gotohda N, Takahashi S, et al. Relationship between the histological type of initial lesions and the risk for the development of remnant gastric cancers after gastrectomy for synchronous multiple gastric cancers. World J Surg 2010; 34(2):296–302.

Ahn HS, Kim JW, Yoo MW, et al. Clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes of patients with remnant gastric cancer after a distal gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2008; 15(6):1632–9.

Imada T, Rino Y, Takahashi M, et al. Clinicopathologic differences between gastric remnant cancer and primary cancer in the upper third of the stomach. Anticancer Res 1998; 18(1A):231–5.

Sasako M, Maruyama K, Kinoshita T, Okabayashi K. Surgical treatment of carcinoma of the gastric stump. Br J Surg 1991; 78(7):822–4.

Schaefer N, Sinning C, Standop J, et al. Treatment and prognosis of gastric stump carcinoma in comparison with primary proximal gastric cancer. Am J Surg 2007; 194(1):63–7.

Kodama M, Tur GE, Shiozawa N, Koyama K. Clinicopathological features of multiple primary gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 1996; 62(1):57–61.

An JY, Choi MG, Noh JH, et al. The outcome of patients with remnant primary gastric cancer compared with those having upper one-third gastric cancer. Am J Surg 2007, 194(2):143–7.

Rabin I, Kapiev A, Chikman B, et al. Comparative study of the pathological characteristics of gastric stump carcinoma and carcinoma of the upper third of the stomach. The Israel Medical Association journal : IMAJ 2011, 13(9):534–6

Sowa M, Onoda N, Nakanishi I, et al. Early stage carcinoma of the gastric remnant in Japan. Anticancer Res 1993; 13(5C):1835–8.

Hu X, Tian DY, Cao L, Yu Y. Progression and prognosis of gastric stump cancer. J Surg Oncol 2009; 100(6):472–6.

Sobin L, Wittekind D, (eds). TNM classification of malignant tumors (6th edition). Japanese 2002.

Svanes C, Salvesen H, Stangeland L, et al. Perforated peptic ulcer over 56 years. Time trends in patients and disease characteristics. Gut 1993; 34(12):1666–71.

Maruyama K, Kaminishi M, Hayashi K, et al. Gastric cancer treated in 1991 in Japan: data analysis of nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer 2006; 9(2):51–66.

Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(1):11–20.

Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med 2007; 357(18):1810–20.

Safatle-Ribeiro AV, Ribeiro U, Jr., Reynolds JC. Gastric stump cancer: what is the risk? Dig Dis 1998; 16(3):159–68.

Pointner R, Schwab G, Konigsrainer A, et al. Gastric stump cancer: etiopathological and clinical aspects. Endoscopy 1989; 21(3):115–9.

Ikeguchi M, Kondou A, Shibata S, et al. Clinicopathologic differences between carcinoma in the gastric remnant stump after distal partial gastrectomy for benign gastroduodenal lesions and primary carcinoma in the upper third of the stomach. Cancer 1994; 73(1):15–21.

Tanigawa N, Nomura E, Lee SW, et al. Current state of gastric stump carcinoma in Japan: based on the results of a nationwide survey. World J Surg 2010; 34(7):1540–7.

Sanchez-Bueno F, Marin P, Rios A, et al. Has the incidence of perforated peptic ulcer decreased over the last decade? Dig Surg 2001; 18(6):444–7; discussion 447–8.

Viste A, Eide GE, Glattre E, Soreide O. Cancer of the gastric stump: analyses of 819 patients and comparison with other stomach cancer patients. World J Surg 1986; 10(3):454–61.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tokunaga, M., Sano, T., Ohyama, S. et al. Clinicopathological Characteristics and Survival Difference Between Gastric Stump Carcinoma and Primary Upper Third Gastric Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 17, 313–318 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-012-2114-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-012-2114-0