Abstract

Objectives

This study seeks to discuss the management and diagnosis of Amyand’s hernia, an exceedingly rare diagnosis.

Methods

The case of a 60-year-old female found to have inguinal appendicitis on preoperative computed tomography imaging is presented.

Results

The patient underwent concomitant laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair and appendectomy.

Discussion

Laparoscopic management of Amyand’s hernia should be strongly considered for repair and resection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Clinical History

A 60-year-old female presented with a 1 day history of abdominal pain accompanied by anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. She denied fevers or chills at home. During the time preceding her presentation to our institution, she reported that her pain was becoming increasingly intense in her right lower quadrant. On physical examination, her abdomen was minimally tender in the right lower quadrant but without evident peritoneal signs. Additionally found on clinical exam was a tender right inguinal mass. Laboratory work was significant only for a leukocytosis of 12,500.

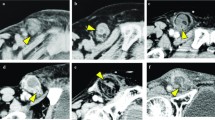

Concern was immediately for incarcerated femoral hernia. However, given her history of periumbilical pain migrating to the right lower quadrant in the face of leukocytosis, there was great concern for an intraperitoneal process; namely appendicitis. For this reason, a high resolution helical computed tomography (CT) scan was performed of her abdomen and pelvis with imaging to mid-femur. The images clearly demonstrated a right inguinal hernia containing the distal portion of the appendix (Fig. 1).

The patient was taken to the operating room for laparoscopic appendectomy. At this time, the appendix was found to be passing through the internal inguinal ring (Fig. 2). An appendectomy and inguinal hernia repair were completed laparoscopically without complication. Final pathology confirmed acute appendicitis with necrosis of the distal appendix. The patient was discharged home on postoperative day 1.

Discussion

The first described appendectomy was performed in 1735 by Claudius Amyand at St. George’s Hospital in London.1–8 The patient was a small boy who presented with the apparent symptoms of an incarcerated inguinal hernia. Upon exploration, it was immediately evident that the patient instead suffered from appendicitis in an unusual location. Authors, since this initial description, note that appendicitis in the inguinal canal occurs in approximately 0.1–0.3% of cases of acute appendicitis.4 It is thus an exceedingly rare culmination of the two most common general surgery diagnoses.

The presentation of Amyand’s hernia is generally quite similar to our patient. The natural history begins with typical visceral symptoms, many of which are ignored by patients. As the course progresses, the patient generally reports intense groin pain that does not abate rather than acute abdominal pain. The physical exam findings are nearly always consistent with incarcerated inguinal hernia. With the widespread use of helical CT scans in current practice, the diagnosis of appendicitis in the inguinal canal is made increasingly preoperatively.

Operative management and postoperative course should not differ from patients with the separate diagnoses of appendicitis or incarcerated inguinal hernia. The approach to operative repair of Amyand’s hernia has historically been described as via a groin incision; in essence, a standard open herniorraphy approach. This approach remains from a time when helical CT scans were not as widely available and thus the preoperative diagnosis was nearly always incarcerated inguinal hernia. This is not the case today. With the widespread availability of high quality CT scans, there should not be uncertainty regarding the preoperative diagnosis. Herniorraphy and appendectomy may safely be undertaken simultaneously, and several authors report preference for non-mesh repair as the field is nearly always contaminated.1, 8, 9 In one large series, risk of recurrence was no greater in those patients with a non-mesh, tension-free repair, but the incidence of postoperative infection was nearly 50% in those with mesh repair.6

In our case, we chose to perform laparoscopy initially to confirm the diagnosis, insure no other intraperitoneal pathology, and finally, as a method of operative repair. We believe that laparoscopy can be an efficacious and safe method for undertaking an operation for Amyand’s hernia. Initially, this approach allows for identification of potentially more serious intraperitoneal processes. Should the preoperative diagnosis be confirmed, resection and repair can be undertaken with minimal morbidity to the patient. With current widespread experience in laparoscopic hernia repair and appendectomy, it seems only reasonable to address such a historic diagnosis with such a modern technique.

References

Logan M, Nottingham J. Amyand’s Hernia: A Case Report of an Incarcerated and Perforated Appendix within an Inguinal Hernia and Review of the Literature. The American Surgeon. 2001; 67(7):628–629.

Milanchi S, Allins AD. Amyand’s hernia: history, imaging, and management. [Internet]. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2008; 12(3):321–2. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17990042

Cankorkmaz L, Ozer H, Guney C, Atalar MH, Arslan MS, Koyluoglu G. Amyand’s hernia in the children: a single center experience. [Internet]. Surgery. 2010; 147(1):140–3. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19910011

Inan I, Myers PO, Hagen ME, Gonzalez M, Morel P. Amyand’s Hernia: 10 Years Experience [Internet]. The Surgeon. 2009; 7(4):198–202. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1479666X0980084X

Meinke AK. Review article: appendicitis in groin hernias. [Internet]. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2007; 11(10):1368–72. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17394046

Hutchinson R. Amyand’s hernia [Internet]. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1993; 86(5):104–105. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19917948

Hiatt J, Hiatt N. Amyand’s Hernia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1988; 318(21):1402.

Ranganathan G, Kouchupapy R, Dias S. An approach to the management of Amyand’s hernia and presentation of an interesting case report. [Internet]. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2009; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20039085

Carey LC. Acute Appendicitis occurring in hernias: A Report of 10 Cases. Surgery. 1967; 61(2):236–238.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mullinax, J.E., Allins, A. & Avital, I. Laparoscopic Appendectomy for Amyand’s Hernia: A Modern Approach to A Historic Diagnosis. J Gastrointest Surg 15, 533–535 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-010-1386-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-010-1386-5