Abstract

Background

Diagnosis of complications after laparoscopic surgery is difficult and sometimes late.

Methods

We compared the outcome of patients who had early (<48 h) relaparoscopy for suspected postoperative complication to those where relaparoscopy was delayed (>48 h).

Results

During the study period, 7726 patients underwent laparoscopic surgery on our service. Of these, 57 (0.7%) patients had relaparoscopy for suspected complication. The primary operations were elective in 48 patients and emergent in nine. Thirty-seven patients had early, 20 had delayed, secondary operations. The most common indication in the early group was excessive pain (46%) followed by peritoneal signs in 35%. In the delayed group, the most common indication was signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome in 30% and peritoneal signs in 25%. Relaparoscopy was negative in 16 (28%) patients with no difference between groups. The identified complication was treated laparoscopically in 37(65%) patients, and the rest were converted. The patients in the delayed group had a significantly longer hospital stay (p < 0.003) and had a higher rate of complications (p < 0.05). They also had a higher mortality rate (10% vs. 2.7%), but the difference was not statistically significant.

Conclusions

A policy of early relaparoscopy in patients with suspected complications enables timely management of identified complications with expedient resolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The main advantage of minimally invasive over open surgery is the shorter and more benign postoperative course. Following elective or emergency laparoscopic procedures, most patients are discharged the next day and suffer minimal postoperative pain and discomfort. However, minimally invasive surgery is not without risk. The reported incidence of complications varies with the particular operation and ranges between 0.05% and 8%.1, 2 A delay in diagnosis of these complications is common (40–77%)1,3–5 and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.6–8

When complications are suspected, most surgeons rely on imaging studies for diagnosis; however, at least early on, the radiological findings are nonspecific. Residual fluids or free gas in the peritoneal cavity are common after laparoscopic surgery and are often misinterpreted as normal postoperative findings.1, 9

Most surgeons are reluctant to take patients back to the operating theater, and the aphorism that the operating surgeon is the last one to recognize a complication is well known. However, early relaparoscopy is usually easy and safe, as the old port sites can be used for blunt entry and may be the most efficient route to diagnosis and management.

In this study, we retrospectively compared the outcomes of patients who had early (less than 48 h from the original operation) relaparoscopy to the outcomes of those where the intervention was delayed. We hypothesized that early relaparoscopy would lead to improved outcomes as well as be cost effective.

Material and Methods

General

We reviewed the records of all patients who had relaparoscopy for suspected complications between January 2000 and July 2006. The patients were identified by manual review of the operating room registry. All patients had primary and repeated surgery in our department at Soroka Medical Center tertiary 1100 beds hospital providing medical care to more than one million residents in Southern Israel. One of the principles of our hospital, which is readmission of all patients, is performing to primary service where surgery was done. All patients were instructed before discharge and, in case of any postoperative problem, they may call or return directly to our department. On our knowledge, all patients that had postoperative complications after primary laparoscopic surgery included in this series.

The patients were divided into early (<48 h) or delayed (>48 h) groups based on the interval between the primary operation and the relaparoscopy. Data collected included age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, type of primary surgery, use of imaging studies, indications for reoperation, operative findings, duration of relaparoscopy and rate of conversion, morbidity related to the relaparoscopy, final disposition, and overall length of stay.

Epiinfo v3.3 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA) was used for data entry and analysis. Nonparametric statistics were used for comparing length of stay and Fisher’s exact test for frequencies; p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Surgical Considerations

Repeated laparoscopy was attempted in all patients when complication was suspected after laparoscopic procedure. There were no cases when reexploration was performed by open manner from the beginning.

Reentry into the abdomen was done through one of the previous port sites, using a bluntly inserted 11-mm cannula. Following the establishment of pneumoperitoneum, other cannulas were inserted via the old port sites under vision.

In cases of bile leaks from the cystic duct stump, the stump was closed with an endoloop (Surgitie, Auto Suture, United States Surgical Corporation, Norwalk, CT, USA). When the source of the leak was not readily identified, an intraoperative cholangiogram was performed via the stump. In cases for suspected gastric perforation where the hole was not readily seen, the stomach was filled with methylene blue dye to localize the injury.

Other complications were managed by either conversion to a formal laparotomy, a small target incision, or laparoscopically at the discretion of the operating surgeon.

Results

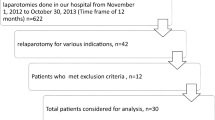

During the study period, 7726 patients had laparoscopic surgery on our service. Of these, 57 patients (0.7%) had relaparoscopy for suspected complications and were included in the present series. Of these, 37 had early (48 h or less) relaparoscopy, and in 20, the secondary operation was delayed. Three patients in early (8%) and ten in late group (50%) were discharged after surgery and readmitted to our department. The distribution of age, sex, and ASA score was similar between the groups, but there were slightly more emergency operation in the delayed group (Table 1).

The distribution of primary operations is listed in Table 2. All patients with suspected complications after either primary or revisional laparoscopic banding for morbid obesity were reoperated on early. Two thirds of the 27 relaparoscopies following cholecystectomy were in the early group. Other primary operations were more or less evenly distributed between the groups.

The decision to perform relaparoscopy was made by the attending surgeon involved in the case; however, input from other group members, including residents, was often influential. The indications for relaparoscopy are listed in Table 3. The most common indication in the early group was excessive pain and increased demand for narcotics (46%) followed by peritoneal signs (tenderness, guarding) in 35%. In the delayed group, the most common indication was signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome in 30% and peritoneal signs in 25%. Excessive pain was the indication in only 20% of the patients in the delayed group.

Although 30% of patients had some sort of imaging study, the studies had little influence on the decision to operate. In the early group, 18% of the patients had an imaging study, all of which were negative (with a false negative rate of 67%). In the delayed group, 55% of the patients had an imaging study. This includes four patients with intestinal obstruction evident on plain films. One patient had a US examination which was a true negative, and six patients had an abdominal computed tomography (CT) with five true positives and one false negative.

The findings at relaparoscopy by timing group are summarized in Table 4 and described according to primary procedure in Table 5. Bile leaks and bleeding were the most common identified complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, followed by gastric perforation after bariatric surgery and small bowel obstruction and adhesions after incisional hernia repair. Gastric perforations were all in the early group, while the rest were more or less evenly distributed between the groups. The rate of negative reexplorations was similar in both groups (10/37 and 6/20, or 27% and 30%, respectively). All 16 patients with negative explorations had no further complications and were discharged uneventfully after 2 or 3 days. In both groups, negative explorations were more common when the primary operation was cholecystectomy and when the only indication was excessive pain.

In both groups, the majority (85%) of the complications could be handled laparoscopically. In particular, early diagnosis of hollow viscus injury enabled successful laparoscopic suturing in six out of ten patients where it was identified. One patient with cecal injury following laparoscopic appendectomy was managed by tube cecostomy. Laparoscopic release was possible in all five cases of small bowel obstruction.

The outcome of relaparoscopy is summarized in Table 6. The patients in the delayed group had a significantly longer hospital stay (p < 0.003 by the Wilcoxon rank sum test) and had a higher rate of complications (p < 0.05 by Fisher’s exact test). They also had a higher mortality rate (10% vs. 2.7%), although the difference was not statistically significant.

There were three deaths in this series. One was a 57-year-old woman who had a bile leak from the gallbladder bed following cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. The indication for relaparoscopy was septic shock and acute renal failure; the source of the leak could not be identified, and leak was drained initially. She failed to improve, and we attempted to drain the biliary tree via a tube in the cystic duct. She was found to harbor invasive gallbladder carcinoma in the resected specimen.

The second death was a young man with a congenital immune deficiency disorder who also went into septic shock following a rather minor bile leak from an accessory cystic duct. He actually went home following the original cholecystectomy and was readmitted 3 weeks later in severe sepsis. He died despite successful closure of the leak and adequate drainage.

The third death was a woman who had a gastric injury following laboratory-measured blood gases. She had a water soluble contrast study, which failed to identify the leak but led to a significant delay in diagnosis. She had multiple operations and a stormy course in the intensive care unit and died of multiple organ failure.

Discussion

Dealing with complications is part and parcel of the practice of surgery. Laparoscopic surgery is no exception. Following laparoscopic surgery, complications occur in between 0.05% to 8% of patients.1,2,10,11 The key to obtaining a favorable outcome despite the complications is early recognition and prompt attention.

When injuries are recognized during the procedure, the outcome is usually favorable, as they can be primarily repaired. However, delayed diagnosis is often associated with increased morbidity and mortality. From one half to two thirds of injuries5,12 are discovered belatedly, and it stands to reason that earlier diagnosis may improve outcome.

Following laparoscopic surgery, the postoperative course is usually smooth and is characterized by minimal pain and early mobilization. Whenever the postoperative course does not follow the usual pattern and recovery is delayed, a complication should be suspected.6 Lee4 argues, and we agree, that suspicion should be raised when a patient is not doing well after a cholecystectomy and exhibits extraordinary abdominal pain, anorexia, or fever. He suggested that such findings require appropriate diagnostic studies.

Diagnostic studies can be some sort of imaging or laboratory tests. Laboratory tests are rather nonspecific and have a poor diagnostic yield,1 so most surgeons rely on imaging studies. The results of the present study suggest that these, too, are often misleading and can cause an unnecessary delay in diagnosis.

In the present series, imaging studies had a high false negative rate and led to a delay in diagnosis, with at least one death. Similar findings were also reported by Schrenk,1 who emphasized that negative investigations do not exclude a serious complication. Even positive findings are not always conclusive. For instance, Dexter9 showed that following laparoscopic cholecystectomy, as many as 43% of patients have free fluid in the abdominal cavity by CT scan or ultrasonic examination and that this finding is nonspecific and usually meaningless.

A formal laparotomy is overkill for diagnostic purposes. Most surgeons resort to a formal laparotomy when a bowel injury is identified.12 However, a formal laparotomy is associated with pain, ileus, and increased risk of abdominal infection. Consequently, it is only employed after a definitive diagnosis or clear indications that the patient is in trouble.

In contrast, relaparoscopy is simple and, if negative, does not increase morbidity. When done early, the old port sites are still open and access and pneumoperitoneum can be achieved bluntly (even when the Veress needle was used during the initial laparoscopic operation); consequently, its use as the primary diagnostic modality in suspected complications can be justified.

In the present series, we were able to make the correct diagnosis by relaparoscopy in all cases. Our findings are supported by similar results in other recent series.9,13–15 Laparoscopy allows visualization of entire abdominal cavity, recognition of a complication, and its treatment. Often, an identified complication can be handled laparoscopically, and a formal laparotomy can be avoided. In this series, as many as 80% of the complications were handled laparoscopically. This enhances patients’ (and surgeons’) satisfaction with the overall process despite the complication and shortens hospital stay.

The range of laparoscopic procedure-associated complications including Veress needle and trocar injuries, iatrogenic tears of distended and inflamed bowel wall, and tears during dissection of adhered bowel loops after previous abdominal surgery, injuries following use of cautery for dissection. In our series, gastric tears occurred following perigastric dissection during laparoscopic gastric banding placement. During relaparoscopy, small bowel and colonic tears were found after cholecystectomy, appendectomy, and revision bariatric procedure. Small bowel obstruction was the most frequent complication following laparoscopic incisional hernia repair.

Twenty-seven of 57 patients underwent relaparoscopy following suspected complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. In this group, eight patients (30%) had bile leaks, all were successfully managed during relaparoscopy. Alternative management options for bile leaks include percutaneous drainage and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with stenting or sphincterotomy. Percutaneous drainage alone requires prolonged hospitalization, as the drain may remain in situ for a while until drainage stops, or must be supplemented by ERCP if the leak persists.

ERCP is not a benign procedure. Its morbidity and mortality is usually underestimated. Most series report “ERCP-related mortality” or “Procedure-specific mortality” or other similar terms, which are vague and open to obvious biases. In series that report overall or 30-day mortality, the mortality rate ranges from 1.4–4%*****. Deaths are more common with interventions, such as sphincterotomy and repeat procedures.

In addition, a stent, if placed, must be removed 1–3 months later. Removing the stent involves additional exposure to the risk of ERCP and increases costs. The data presented here suggest that the mortality and morbidity of early relaparoscopy is lower than that of ERCP.

In the present series, 28% of the relaparoscopies were negative. Negative relaparoscopies were not associated with any complications and had minimal impact on patient’s hospital stay. These patients were not doing well and so were not candidates for next day discharge. The negative reexplorations eliminated the need for multiple imaging studies and reassured both patient and surgeon that all was well.

One argument against early relaparoscopy is that it may increase overall costs. Although we did not calculate costs directly (mainly because public hospital care in Israel is free), the mean hospital stay in the delayed group was almost twice as long as the stay in the early group. This represents a potential saving which should far outweigh the added costs of the negative reexplorations.

The morbidity in the early group was also lower than in the delayed group. This result was not due to a higher rate of negative relaparoscopies or to the nature of complications discovered. Both groups had similar rates of negative explorations, and the incidence of hollow viscus injuries was also similar between the two groups

As a matter of departmental policy, the relaparoscopy was almost always done by the attending surgeon who supervised the primary procedure and assisted by a second experienced laparoscopic surgeon who was not involved in the original operation. We feel that this policy enhances both the diagnostic accuracy and the ability to handle most complications laparoscopically.

Conclusions

Although our conclusions are limited by the retrospective nature of this study, we can conclude that clinical findings are highly suspicious for the presence of complications and that in experienced hands, early relaparoscopy is a fast and safe method of identifying and often solving the problem.

References

Schrenk P, Woisetschlager R, Rieger R, Wayand W. Mechanism, management, and prevention of laparoscopic bowel injuries. Gastrointest Endosc 1996;43:572–574.

Schafer M, Lauper M, Krahenbuhl L. Trocar and Veress needle injuries during laparoscopy. Surg Endosc 2001;15:275–280.

Vilos GA. Laparoscopic bowel injuries: forty litigated gynaecological cases in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2002;24:224–230.

Lee CM, Stewart L, Way LW. Postcholecystectomy abdominal bile collections. Arch Surg 2000;135:538–542. discussion 42–44.

Ferriman A. Laparoscopic surgery: two thirds of injuries initially missed. Bmj 2000;321:784.

Shamiyeh A, Wayand W. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: early and late complications and their treatment. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2004;389:164–171.

Papasavas PK, Caushaj PF, McCormick JT, Quinlin RF, Hayetian FD, Maurer J et al. Laparoscopic management of complications following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Surg Endosc 2003;17:610–614.

Perrone JM, Soper NJ, Eagon JC, Klingensmith ME, Aft RL, Frisella MM et al. Perioperative outcomes and complications of laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surgery 2005;138:708–715. discussion 15–16.

Dexter SP, Miller GV, Davides D, Martin IG, Sue Ling HM, Sagar PM et al. Relaparoscopy for the detection and treatment of complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg 2000;179:316–319.

Dixon M, Carrillo EH. Iliac vascular injuries during elective laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc 1999;13:1230–1233.

Mayol J, Garcia-Aguilar J, Ortiz-Oshiro E, De-Diego Carmona JA, Fernandez-Represa JA. Risks of the minimal access approach for laparoscopic surgery: multivariate analysis of morbidity related to umbilical trocar insertion. World J Surg 1997;21:529–533.

van der Voort M, Heijnsdijk EA, Gouma DJ. Bowel injury as a complication of laparoscopy. Br J Surg 2004;91:1253–1258.

Hackert T, Kienle P, Weitz J, Werner J, Szabo G, Hagl S et al. Accuracy of diagnostic laparoscopy for early diagnosis of abdominal complications after cardiac surgery. Surg Endosc 2003;17:1671–1674.

Wills VL, Jorgensen JO, Hunt DR. Role of relaparoscopy in the management of minor bile leakage after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 2000;87:176–180.

Rosin D, Zmora O, Khaikin M, Bar Zakai B, Ayalon A, Shabtai M. Laparoscopic management of surgical complications after a recent laparotomy. Surg Endosc 2004;18:994–996.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kirshtein, B., Roy-Shapira, A., Domchik, S. et al. Early Relaparoscopy for Management of Suspected Postoperative Complications. J Gastrointest Surg 12, 1257–1262 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-008-0515-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-008-0515-x