Abstract

Background

Several techniques of laparoscopic bile duct exploration and intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) have been developed to treat patients with common bile duct (CBD) stones in one session and avoid the complications of ES. With all these options available, very few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been undertaken. This review analyzes those studies.

Methods

We searched PubMed. Four RCTs and a Cochran Database Systematic Review were found.

Results

Two RCTs compared preoperative ES and laparoscopic CBD exploration (E) for known CBD stones. Laparoscopic CBDE had shorter length of hospitalization. Two RCTs compared immediate and delayed treatment and found that length of stay was less with laparoscopic CBDE, but clearance rates and morbidity/mortality were similar.

Conclusions

Studies suggest that CBD stones discovered at the time of cholecystectomy are best treated during the same operation. The transcystic approach is safest if applicable. Individual surgeons must be aware of their own capabilities and those of the available endoscopists and perform the safest technique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The incidence of choledocholithiasis in patients undergoing cholecystectomy varies with age, ranging from 6% in patients less than 80years old to 33% in patients more than 80 years of age.1 It is estimated that 5% to 12% of patients with choledocholithiasis may be completely asymptomatic and have normal liver function tests.2–4 The vast majority of common bile duct (CBD) stones originate from the gallbladder, and only a small percentage of patients will develop CBD stones de novo. Choledocholithiasis is diagnosed during cholecystectomy under two scenarios: 1.) Intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) performed on patients with a high suspicion of CBD stones based on history, ultrasound or other imaging, and liver function tests; and 2.) IOC performed on patients as part of a protocol of routine cholangiography.

The treatment of common bile duct calculi was uniform before the adoption of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC). In the prelaparoscopic era, patients suspected of harboring CBD stones underwent intraoperative cholangiography. If CBD calculi were discovered, choledochotomy, stone extraction, and T-tube placement were performed. The introduction of therapeutic laparoscopy altered the surgical approach to CBD stones. In the 1990s, preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) became the standard approach for patients suspected of having choledocholithiasis to avert subsequent intraoperative conversion to open common bile duct exploration (CBDE). Postoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) became the preferred approach to treat CBD stones encountered during LC or discovered afterwards. In some communities, ERC/ES increased 243%.2

In an effort to treat patients with CBD stones in one session and avoid the potential complications of ES (especially in younger patients with small-diameter CBD), several techniques of laparoscopic transcystic common bile duct exploration (LTCBDE) and laparoscopic choledochotomy were developed. Also, intraoperative ES has been advocated. With all of these options available, only a few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been undertaken to define the best treatment algorithms for patients with CBD stones. This review analyzes those studies, i.e., the highest level of evidence.

Methods

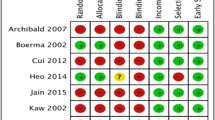

A search of PubMED (a service of the U.S. National Library of Medicine; www.pubmed.gov) was performed. The search terms used for the review include “common duct stones,” “common duct,” “common duct exploration,” “common bile duct exploration,” “endoscopic sphincterotomy,” “transcystic,” “choledochotomy,” and “bile duct stones.” The primary search was then distilled to include randomized controlled trials (RCT). Two RCTS were found that compared treatment for preoperatively known CBD stones and two RCTs compared treatments of intraoperatively discovered CBD stones. A Cochrane Database Systematic Review was also found. This Level I evidence along with other relevant studies are analyzed here.

Results and Discussion

Laparoscopic techniques of CBDE were developed in the early 1990s to decrease the need for preoperative ERC and treat patients in one session. Two RCTs compared the treatment of known CBD stones—preoperative ES vs. laparoscopic CBDE.5,6 The results are described in Table 1. The results of the two approaches are similar, although the length of hospital stay is shorter with LCBDE in the Cuscheiri, et al. study. The weakness inherent in these studies is that they fail to include the morbidity of negative preoperative ERC.

During the early experience with LC, many patients underwent preoperative ERC/ES. Freeman presented a multicenter 30-day outcome study of ES at the 1994 World GI Congress in Los Angeles. This study, which included 1,494 patients, revealed an overall complication rate of 7.4%, procedure-related mortality of 0.5%, and all-cause mortality of 2.2%.7 Although the days of routine preoperative ERC are over, laparoscopic techniques of CBDE still have not been widely embraced.

Several options are available when confronted with CBD stones during cholecystectomy: open CBDE, laparoscopic CBDE, and intraoperative ES. Laparoscopic CBDE involves either transcystic CBD stone extraction (fluoroscopic guided wire basket or choledochoscopy) or laparoscopic choledochotomy and stone extraction. Several cohort studies have shown that two thirds of the stones detected by intraoperative cholangiography can be removed via the transcystic approach.8 For patients in whom transcystic extraction of CBD stones fails, laparoscopic choledochotomy and stone extraction may be performed. However, this approach requires experience in laparoscopic suturing and a CBD of adequate diameter.

Alternative management options have been described, but have not been subjected to RCT. For example, intraoperative ES has been reported in a number of centers. This approach is wholly dependent on the availability of endoscopic expertise in the operating room. Available results, although limited, show high clearance rates in excess of 90%, with minimal morbidity and no increase in the length of hospital stay over that of laparoscopic cholecystectomy alone.9,10

The other alternative to immediate treatment of CBS stones discovered at surgery is delayed treatment. Surgeons can insert a biliary stent through the cystic duct into the CBD and through the sphincter of Oddi.11 This procedure ensures access to the bile duct for postoperative ES.

When CBD stones are discovered intraoperatively, what is the best treatment option? Two prospective randomized studies (Table 2) have evaluated the merits of immediate versus delayed treatment for bile duct stones. Rhodes et al. (1995)12 randomized 80 patients at the time of diagnosis by cholangiography to either laparoscopic exploration or delayed postoperative ES. Patients were excluded if they had preoperative ES, cholangitis, or acute pancreatitis. The laparoscopic approach entailed transcystic exploration (n = 28) of the duct followed, if necessary, by laparoscopic choledochotomy (n = 12) in those patients with CBD exceeding 6 mm in diameter. This study showed that both techniques were associated with a 75% successful bile duct clearance rate at the time of first intervention. Final duct clearance was not significantly different, although there was a trend toward better clearance with the laparoscopic approach. The length of hospital stay was significantly shorter with the single-stage approach (1 day, 3.5 day; p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in morbidity (18%, 15%; p = NS) or mortality (0%, 0%). However, the authors concluded that the transcystic approach was preferred.

Nathanson et al. (2005)8 conducted a more focused study. Patients were included only if the transcystic approach failed to clear the intraoperatively discovered CBD stones. Eighty-six patients were randomized to laparoscopic choledochotomy or delayed postoperative ES. There were no differences between the two approaches in terms of bile duct clearance rates, morbidity, or length of hospital stay. However, the patients undergoing choledochotomy experienced a significantly higher rate of bile leak (14.6%) from the choledochotomy. The authors conclude that both techniques are efficacious, while recognizing that the laparoscopic approach may be limited in less experienced centers.

A Cochrane systematic review by Martin et al. (2006)13 concluded that a single-stage treatment of bile duct stones via the cystic duct approach was recommended for intraoperatively discovered CBD stones. In patients where it is not possible to clear the duct by this approach, a delayed postoperative ES would be the preferred option in most centers. However, it was also noted that the reported experience is limited, and larger randomized trials are warranted to compare these therapeutic options.

A potential study when transcystic exploration fails might be the use of open CBDE in younger patients versus postoperative ES in older people. Open CBDE has been shown in RCTs to result in morbidity ranging from 11% to 14% and mortality of 0.6% to 1%. Interestingly, Morgenstern et al.14 reported on 220 open CBDE before the laparoscopic revolution. Their results revealed no mortality in patients under 60 years of age and 4.3% mortality in those over 60. This suggests that patient age could affect the treatment algorithm, and that ES should be strongly considered in patients above the age of 60.

Other deficiencies in our literature must be considered in addition to the paucity of RCTs. First, we have few data on the natural history of small or “silent” stones and the true morbidity of retained CBD stones. One recent study from the United Kingdom reported a series of patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy with routine cholangiogram. In patients discovered to have CBD stones, a transcystic catheter was left in place for postoperative cholangiogram. Fifty percent of these patients were discovered to be stone-free after 6 weeks.15 Next would be the methodology of future trials. In the aforementioned RCTs, there were numerous exclusion criteria that changed the management of some patients. These exclusion criteria included acute pancreatitis, acute cholangitis, anatomy precluding ERCP, ASA status 3–4, and the need for a drainage procedure of the CBD. Also, the issue of operative experience must be considered.

Over the past 30 years, the number of cholecystectomies performed annually in the United States has increased from approximately 400,000 to 750,000 per year. On the other hand, the rate of CBDE has dropped dramatically from approximately 20% to 2%. In total, only approximately 15,000 CBDEs are performed each year. Experience is therefore limited in the performance of laparoscopic removal of CBD stones. Although the results are generally excellent in the published reports, these usually originate from centers of excellence, and there are no data on the outcomes of procedures performed by less experienced surgeons. Clearly, the incidence of surgical CBD exploration has diminished over the past few decades. A recent report from the national inpatient database suggested that only 7% of CBD stones are treated surgically, with the remainder being managed by endoscopic techniques.16 Furthermore, the number of CBD explorations reported by finishing chief surgery residents has decreased from a mean of 10 in 1990 (all “open”) to means of 1.5 open and 0.8 laparoscopic CBD explorations in 2006. Thus, it is clear that trainees are not gaining adequate hands-on experience in CBD exploration.

Finally, the indications for a surgical drainage procedure or an endoscopic sphincterotomy must be considered. A Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, a choledochojejunostomy, or a surgical sphincteroplasty may be indicated for sphincter of Oddi stenosis/dysfunction, primary CBD stones, patients with duodenal diverticula, multiple CBD stones, or intrahepatic stones. Similarly, ES is indicated for patients with CBD stones with severe preoperative cholangitis or pancreatitis, and for sphincter of Oddi stenosis/dysfunction. When these indications overlap, open CBDE and ES are often complementary. However, open CBDE remains the “gold standard” for selected, rare patients such as those with Mirizzi syndrome, Billroth II anatomy, and those requiring a drainage procedure. Because experience is now limited, these procedures should be performed by a hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) surgeon with advanced training.

Conclusion

The results of studies over the last decade suggest that stones detected in the CBD at the time of LC are best treated via a transcystic laparoscopic approach during the same operation. If this fails, alternate approaches such as intraoperative or postoperative ES, laparoscopic choledochotomy or open CBDE may be used. Alternatively, a stent may be placed through the cystic duct and across the sphincter of Oddi to facilitate postoperative ES. These data reveal areas that require future study that will help clinicians treat their patients with CBD stones (Table 3).

Figure 1 illustrates a proposed algorithm for treating CBD stones detected on intraoperative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. However, it is unrealistic to extrapolate standards of care based on the available RCTs given the wide variation in skills and resources available in different communities. Individual surgeons must recognize their own limitations and the limitations of available endoscopists and perform the safest approach.

References

Johnson AG, Hosking SW. Appraisal of the management of bile duct stones. Br J Surg 1987;74:555–560.

Acosta MJ, Rossi R, Ledesma CL. The usefulness of stool screening for diagnosing cholelithiasis in acute pancreatitis. A description of the technique. Am J Dig Dis 1977;22:168–172.

Murison MS, Gartell PC, McGinn FP. Does selective peroperative cholangiography result in missed common bile duct stones? J R Coll Surg Edinb 1993;38:220–224.

Rosseland AR, Glomsaker TB. Asymptomatic common bile duct stones. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;12:1171–1173.

Sgourakis G, Karaliotas K. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and cholecystectomy versus endoscopic stone extraction and laparoscopic cholecystectomy for choledocholithiasis. A prospective randomized study. Minerva Chir 2002;57:467–474.

Cuschieri A, Lezoche E, Morino M, Croce E, Lacy A, Toouli J, Faggioni A, Ribeiro VM, Jakimowicz J, Visa J, Hanna GB. E.A.E.S. multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing two-stage vs single-stage management of patients with gallstone disease and ductal calculi. Surg Endosc 1999;13:952–957.

Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ, Lande JD, Pheley AM. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med 1996;335:909–918.

Nathanson LK, O’Rourke NA, Martin IJ, Fielding GA, Cowen AE, Roberts RK, Kendall BJ, Kerlin P, Devereux BM. Postoperative ERCP versus laparoscopic choledochotomy for clearance of selected bile duct calculi: a randomized trial. Ann Surg 2005;242:188–192.

Enochsson L, Lindberg B, Swahn F, Arnelo U. Intraoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to remove common bile duct stones during routine laparoscopic cholecystectomy does not prolong hospitalization: a 2-year experience. Surg Endosc 2004;18:367–371.

Cox MR, Wilson TG, Toouli J. Peroperative endoscopic sphincterotomy during laparoscopic cholecystectomy for choledocholithiasis. Br J Surg 1995;82:257–259.

Martin CJ, Cox MR, Vaccaro L. Laparoscopic transcystic bile duct stenting in the management of common bile duct stones. Aust NZ J Surg 2002;72:258–264.

Rhodes M, Nathanson L, O’Rourke N, Fielding G. Laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct: Lessons learned from 129 consecutive cases. Br J Surg 1995;82:666–668.

Martin DJ, Vernon DR, Toouli J. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;CD003327.

Morgenstern L, Wong L, Berci G. Twelve hundred open cholecystectomies before the laparoscopic era. A standard for comparison. Arch Surg 1992;127:400–403.

Collins C, Maguire D, Ireland A, Fitzgerald E, O’Sullivan GC. A prospective study of common bile duct calculi in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Natural history of choledocholithiasis revisited. Ann Surg 2004;239:28–33.

Poulose BK, Arbogast PG, Holzman MD. National analysis of in-hospital resource utilization in choledocholithiasis management using propensity scores. Surg Endosc 2006;20:186–190.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Phillips, E.H., Toouli, J., Pitt, H.A. et al. Treatment of Common Bile Duct Stones Discovered during Cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 12, 624–628 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-007-0452-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-007-0452-0