Abstract

Purpose

To determine role of surgical intervention for Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis with hepatolithiasis at a North American hepatobiliary center.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of 42 patients presenting between 1986 and 2005.

Results

Mean age is 54.3 years (24–87). Twenty-seven patients (64%) underwent surgery, after unsuccessful endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or percutaneous intervention in 19/27 patients. Surgical procedures were: 10 common bile duct explorations with choledochojejunostomy and a Hutson loop and 17 hepatectomies (10 with, 7 without Hutson loop). Liver resection was indicated for lobar atrophy or stones confined to single lobe. Operative mortality was zero; complication rates for hepatectomy and common bile duct exploration were comparable (35% vs. 30%). Median follow-up was 24 months (3–228). Of 21 patients with Hutson loops, only seven (33%) needed subsequent loop utilization, with three failures. At last follow-up, 4/27 (15%) surgical patients had stone-related symptoms requiring percutaneous intervention, compared to 4/11 (36%) surviving nonoperative patients. Cholangiocarcinoma was identified in 5/42 (12%) patients; four were unresectable and one was an incidental in-situ carcinoma in a resected specimen.

Conclusion

Surgery is a valuable part of multidisciplinary management of recurrent pyogenic cholangitis with hepatolithiasis. Hepatectomy is a useful option for selected cases. Hutson loops are useful in some cases for managing stone recurrence. Cholangiocarcinoma risk is elevated in this disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hepatolithiasis, the presence of stones in the intrahepatic biliary tract, is often a progressive and complicated problem. Whereas cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis are usually effectively treated with cholecystectomy and common bile duct (CBD) exploration, the treatment of hepatolithiasis tends to be more difficult, with frequent recurrence of stones and symptoms. A multidisciplinary approach, integrating interventional radiology, interventional endoscopy, and surgery is key.

The causes of hepatolithiasis vary. In the West, the disease is most often associated with stricturing conditions of the biliary tree (e.g., primary sclerosing cholangitis [PSC], benign postoperative strictures, malignancy) or stasis (e.g., choledochal cysts). However, in other populations, particularly in East Asia, hepatolithiasis occurs in the absence of these conditions. Theirs is a progressive biliary disease characterized by diffuse biliary tract ectasia with primary biliary stone formation, limited focal stricturing, and repeated episodes of bacterial cholangitis. Hepatic segmental or lobar atrophy may result from longstanding obstruction of a major intrahepatic duct or thrombosis of a portal vein branch.

This disease has been known by a variety of names, including “Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis (RPC)”, “oriental cholangitis”, “oriental cholangiohepatitis”, and “Hong Kong Disease”. In addition to affecting East Asian populations, it is also prevalent among Latin Americans, and has been associated with lower socioeconomic status and rural environments. During the 1960s, complications of primary hepatolithiasis were the third most common abdominal surgical emergency and most common hepatobiliary disease at Queen Mary Hospital in Hong Kong.1 Since then, a decline in incidence has been observed in East Asia, which has been attributed to improved living conditions and Westernization of diet.1 Of interest, an inverse pattern has been observed in Western countries, where RPC with hepatolithiasis was previously rare but has become increasingly more prevalent, particularly in regions receiving migrants from endemic regions.

The pathogenesis of this condition is incompletely understood. Although hepatolithiasis and recurrent cholangitis have been associated with Clonorchis sinensis and Ascaris lumbricoides infections, the evidence for these infections is absent in most patients.1 The common finding of biliary tract ectasia, often diffuse, in the absence of distal obstruction suggests that the disease may result from a primary abnormality of the wall of the biliary tree or chemical components of bile. The pathophysiologic outcome in this disease is the formation of calcium bilirubinate stones within extra- and intrahepatic biliary ducts, although it may be that the stones are the primary event. Morbidity occurs from recurrent episodes of bacterial cholangitis and their sequelae, such as chronic biliary obstruction from stones and strictures, parenchymal atrophy, and liver abscesses. In addition, a significantly elevated risk of cholangiocarcinoma has been reported in patients with RPC.2

The diagnosis is based on clinical presentation in conjunction with findings on imaging, primarily ultrasound (U/S), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as well as cholangiography. Management is directed toward controlling acute episodes of biliary sepsis, extraction of stones, and correction of anatomic abnormalities or sources of chronic infections. Treatment may also require dilatation of strictures and/or resection of atrophic or lobe-dominant disease. Patient care should be multidisciplinary and may include interventional percutaneous cholangiographic (PTC) biliary drainage, ERCP, or surgery. PTC and ERCP approaches to stone extraction and stricture dilatation are often limited by the inability to access diffuse intrahepatic stones. The surgical options include CBD exploration with extraction of stones, resection of lobe- or segment-dominant disease, and the construction of a Hutson biliary access loop of jejunum (Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy that is fixed to the abdominal wall) to facilitate the subsequent percutaneous retrograde extraction of residual or recurrent intrahepatic stones.2 Some surgeons have utilized indwelling transhepatic stents as an accessory to surgical procedures with a similar intention of facilitating percutaneous removal of recurrent stones.3

The objective of this retrospective study was to assess the role of surgical intervention in the management of patients presenting with symptomatic Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis caused by intrahepatic stones, at a North American center. A retrospective analysis of patients with RPC who were referred to the hepatobiliary surgeons at the Toronto General Hospital was performed to determine the outcomes of their treatment.

Methods

Patients included were referred to one of the hepatobiliary surgeons at the Toronto General Hospital between 1986 and 2005. Data were gathered from office/clinic records as well from charts identified through a search of Toronto General Hospital health records, using the ICD-9 codes 574.5, 121.1, 576.1, and the ICD-10 codes K80.30, K80.31, K80.50, K80.51 corresponding to the key words “Calculus of bile duct without mention of cholecystitis”, “Clonorchiasis”, “Cholangitis”, “Calculus of bile duct with cholangitis”, or “Calculus of bile duct without cholangitis or cholecystitis”. All patients included in the study were diagnosed with “Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis” based on history (recurrent episodes of abdominal pain, fever, and jaundice; born in an endemic region; absent or stone-free gallbladder) and consistent radiological appearance (hepatolithiasis, intrahepatic duct dilation, lobar/segmental atrophy.) Cases were excluded if radiological appearance and/or surgical specimen was more consistent with an alternate diagnosis such as choledochal cyst or Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Additional information was obtained from records of the gastroenterologists who performed diagnostic and/or therapeutic ERCPs. Approval for this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Board of the Toronto General Hospital on December 2005.

Abstracted data included date of birth, gender, ethnicity, date of first presentation, date of presentation to Toronto General Hospital hepatobiliary surgeon, symptoms at presentation, anatomic distribution of disease, status of gallbladder stones, history of ERCP attempts at stone extraction, history of percutaneous attempts at stone extraction, surgical procedures performed for management of disease, prevalence of cholangiocarcinoma, and morbidity, and mortality. For each surgical procedure, data were collected on success at stone clearance, rate of stone recurrence, and subsequent management, and complications.

Therapeutic ERCP was performed by a gastroenterologist or surgeon to identify and remove biliary stones and dilate or stent biliary strictures. If a patient had only a diagnostic ERCP, this was not considered part of therapeutic management.

Percutaneous transhepatic management by an interventional radiologist included drainage of an obstructed biliary tree and attempt at stone extraction via the PTC drain. We distinguished between stone retrieval via choledochojejunostomy (Hutson) access loop and via the percutaneous transhepatic route.

The surgical procedures performed included: CBD exploration with extraction of stones, or liver resection, with or without construction of a side-to-side choledochojejunostomy and Hutson access loop. All choledochojejunostomies performed in this series by Toronto General Hospital surgeons were done in conjunction with a Hutson access loop. All cases of liver resection included a CBD exploration. The technique used for the Hutson biliary access loop was the construction of an antecolic Roux-en-Y limb of proximal jejunum with a choledochojejunostomy to a point near the tip of the Roux. A point of the Roux limb between the biliary anastomosis and the distal entero-enterostomy was affixed to the anterior abdominal wall and marked with metal clips to facilitate subsequent localization with x-ray imaging for percutaneous access. No transhepatic stents were placed intraoperatively in this series.

Intraoperative cholangiography was used more frequently in the early part of the series, but not if either diagnostic ERCP or MRC had defined the anatomy and stones accurately within weeks of the surgical procedure. Choledochoscopy was routine when the bile duct was explored for stone extraction.

Results

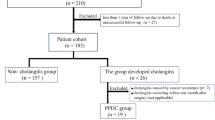

A total of 42 patients with Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis and hepatolithiasis were identified through a search of 2,700 patient records associated with seven hepatobiliary surgeons. Twenty-seven underwent a surgical procedure and 15 did not. The two groups were similar in their presenting characteristics (Table 1). The median age was 54.3 years, with nearly equal gender distribution (55% female: 45% male). The majority of the patients were immigrants to Canada from East Asia. All patients had recurrent episodes of cholangitis. Nearly half of all patients, 20/42 (48%), had a previous cholecystectomy; among the others, the majority had no gallbladder stones on imaging (13/22, 59%). The left lobe was involved in the majority of patients, with 16 left lobe only and 19 bilobar involvement (Fig. 1). All patients demonstrated hepatolithiasis. Twenty-four patients (57%) had parenchymal atrophy: 8/24 affecting left lateral segment, 6/24 affecting entire left lobe, 5/24 affecting right lobe, and 5/24 involving segments bilaterally. The biliary tree appeared ectatic on imaging in most patients (Fig. 1). Median follow-up was 24 (3–228) months.

The number of referrals of patients with RPC and hepatolithiasis to the Toronto General Hospital hepatobiliary surgeons rose significantly over time (Fig. 2). The median time interval between patients’ initial symptoms and their referral to the HBP surgeon was 108 (2–480) months.

Of the 15 nonoperative patients, 12 (80%) had undergone nonsurgical therapy before referral to surgeon, including therapeutic ERCP in nine and PTC stone removal in six. A previous biliary-enteric anastomosis had been performed in two (13%) cases. Reasons for nonoperative management were: five patients declined the offer of surgery, four presented with unresectable tumors (three cholangiocarcinoma; one squamous cell carcinoma), five were considered stable at the time of presentation, and one was lost to follow-up.

In the surgical group, 19/27 (70%) had undergone prior attempts at nonoperative stone extraction: 10/27 had unsuccessful therapeutic ERCP attempts, 8/27 had unsuccessful attempts at percutaneous stone removal, and one patient had attempts at both ERCP and PTC. Four patients (15%) had a previous biliary-enteric anastomosis.

The surgical interventions performed are outlined in Fig. 3. Ten patients underwent CBD exploration with construction of side-to-side choledochojejunostomy and Hutson access loop. In this group, 7/10 had CBD dominant or bilobar stones, two had parenchymal atrophy but no significant intrahepatic stones, and one had right-sided stones with no atrophy and was felt to be amenable to extraction via Hutson loop.

Liver resection was performed in 17 of the 27 surgical patients, of whom 11 also had a choledochojejunostomy with Hutson access loop constructed (ten patients had loop construction at the same time as hepatectomy, and one underwent a subsequent operation to construct an access loop when symptomatic stones in the remaining lobe could not be cleared nonoperatively.) A segment 2/3 resection was performed in four patients, a left lobectomy was performed in 10 patients, and a right lobectomy was performed in three patients. The indications for a liver resection were lobar atrophy in 11/17 patients and for stones confined to one lobe in 5/17 patients. One patient underwent a segment 2/3 resection in the context of bilobar disease and required a second operation 2 years later to resect segment 6 for recurrent symptoms.

The operative morbidity and mortality for CBD exploration was similar to that of hepatic resection (Table 2). Overall, CBD exploration had a 35% complication rate compared to 30% for hepatectomy, and both procedures had zero 30-day mortality. The complication rate for liver resections in conjunction with the construction of choledochojejunostomy with Hutson access loop was no greater than the rate for liver resections alone (3/10 vs. 3/7, respectively).

A total of 21 choledochojejunostomies with Hutson access loops were constructed. At last follow-up, only 7/21 (33%) access loops had been subsequently used for percutaneous removal of stones. There were three failures to access and/or clear stones. In the four successful access procedures, two were performed for symptomatic recurrent stones and two for asymptomatic stones.

At last follow-up, four of the nonsurgical patients had died of unresectable cancer. Of the remaining eleven patients, four (36%) experienced ongoing hepatolithiasis-related symptoms. In the surgical group, only four (15%) patients had recurrent or ongoing symptoms unrelieved by the operative procedure with or without Hutson loop access; three were the patients in whom attempt to use the Hutson loop was unsuccessful, and a fourth patient developed a caudate lobe abscess requiring percutaneous drainage.

Cholangiocarcinoma was identified in five of the 42 patients (12%). Three cases were identified at the time of initial presentation and were unresectable. One was identified as in-situ carcinoma in a resected left lobe specimen, and this patient underwent a re-resection to obtain clear margins. One patient presented as a right hepatic mass 2.5 years after the CBD exploration and choledochojejunostomy with Hutson loop construction. At last follow-up, three of the five patients (60%) had died of their malignancy.

Discussion

This study is an analysis of a 25-year experience managing patients with symptomatic RPC and hepatolithiasis at a major hepatobiliary surgery center in North America (Toronto, Canada). The North American experience with this disease is limited in comparison to East Asia, and the patient populations described in the literature are often heterogeneous. A series published by the Hopkins group in 1994 emphasized the multidisciplinary approach to hepatolithiasis in a series of 54 patients, the majority of whom were Caucasian, and most of whom had stones secondary to biliary stricturing disease (CBD injury, PSC).3 Forty of 54 patients underwent surgery, including 36 Roux-en-Y hepatico- or choledochojejunostomies with large-bore transhepatic stents. Eighteen of 40 operated patients required subsequent percutaneous procedures for stone and/or symptom recurrence. At mean follow-up of 60 months, 94% of the population was stone-free and 87% was symptom-free. Another series published in 1998 by Harris et al. from San Francisco4 describes 45 patients with Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis of whom 39 patients had surgery. All patients were born in Southeast Asia. The surgical procedures included CBD exploration, biliary-enteric anastomoses, and hepatectomies, with average follow-up of 3 years. Details on outcome after surgery were limited but included a complication rate of 6.7% and 10% incidence of postoperative hepatic failure, ultimately needing liver transplantation. In 1999, Cosenza et al.5 published a series of 16 patients treated at the LAC/USC Medical Center, University of Southern California. Except for one, patients were either Asian or Hispanic. The majority (14/16) underwent surgery including construction of a Hutson loop, and two had partial hepatectomy for atrophied left lateral lobe. At 16-month follow-up, 4/14 cases were completely free of stones, whereas 8/14 patients had ongoing minor symptoms related to recurrent stones managed with retrieval via the Hutson loop. An earlier report by Stain et al.6 described a series of 20 RPC patients treated surgically at a University of Southern California Medical Center between 1980 and 1994. Seventeen patients were of Asian origin and three were Hispanic. Four patients underwent hepatectomy only, eight patients had a hepaticojejunostomy, and eight patients had a hepaticojejunostomy with temporary cutaneous stoma for subsequent access and stone retrieval. Three of the hepatectomy patients had postoperative biliary sepsis, with one mortality, and five of eight hepaticojejunostomy patients (without access loop) required reoperation for biliary sepsis. None of the access loop patients required further surgery for stone recurrence or cholangitis.

In this study, most patients were of East Asian origin. As reported previously, the left lobe was affected in the majority of cases, although nearly half of our patients had bilateral hepatic involvement. In our series, there was a long time interval between first presentation of the disease and referral to a surgeon at our institution (mean 9 years), which highlights the chronic and progressive nature of this condition.2,7 Almost half of the patients had previous biliary surgery including cholecystectomy and/or biliary-enteric anastomoses. The relatively short median follow-up time in this study (24 months) reflects the distribution of case referrals, which increased substantially during the time period of the study. Follow-up was based on surgeons’ and hospital records as Research Ethics Board permission to contact the patients for follow-up was not granted.

The changing epidemiology of RPC and hepatolithiasis has been noted previously. In the East, the prevalence is falling, whereas in the West, the incidence is increasing. The prevalence has fallen from 58% to 12% of all patients with biliary calculi at Hong Kong’s Queen Mary Hospital.1 Moreover, in China, the ratio of intrahepatic stones to gallbladder stone disease has dropped from 1:1.5 to 1:7.36 over a 10-year period.8 In the West, this disease has become increasingly more prevalent in centers that receive immigrants from endemic regions. Harris et al.4 describe a doubling of RPC patients presenting to their center in San Francisco during 1984–1995 relative to 1970–1983. Our own experience is similar. The number of patients seen at our center rose sharply after 1995, and has continued to increase. This trend likely reflects an actual increase in the number of patients with symptomatic hepatolithiasis resulting from the changing demographics in a multicultural city such as Toronto, but may also be caused by increasing recognition of the disease by Western radiologists, physicians, and surgeons.

In our series, patients who underwent surgery were compared to those who did not, recognizing the inherent bias that all patients had been referred to a Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary (HPB) surgeon. In most cases, there was a long duration of disease before referral to a surgeon. Nevertheless, the patient and disease characteristics for both groups were similar, and in both subgroups the majority had undergone ERCP and percutaneous attempts at stone extraction and/or biliary drainage, effectively exhausting the nonsurgical options. There is good evidence for the utility of therapeutic ERCP in managing some patients with RPC and hepatolithiasis, primarily for those with extrahepatic stones. In a series of 134 RPC patients in whom the majority had CBD-dominant disease, stone clearance was achieved by ERCP in 91.7% of cases.9 In a report by Sperling et al.,10 which compared 41 patients treated with ERCP, immediate surgery, or no intervention, a subgroup of 15 patients had isolated extrahepatic stones. Of these, 7/9 (71%) of patients treated with ERCP remained asymptomatic at a 2-year follow-up. The use of percutaneously placed transhepatic access catheters has also been reported to have good outcome in the Hopkins series, where this was performed as part of a combined radiologic and surgical team approach that safely allowed for complete stone clearance 51/54 (94%) of patients at 60-month follow-up.3 In our study, the majority of patients had residual stones in the intrahepatic ducts, and the entire study population is biased toward those patients who might have exhausted nonsurgical treatment options; hence, their referral for consideration of surgery. The present series does, however, emphasize the importance of the multidisciplinary approach to the management of patients with RPC and hepatolithiasis.

In the 27 surgical patients, the decision to perform a liver resection was based predominantly on the presence of lobar atrophy (with or without portal vein thrombosis) and/or stones confined to one or more anatomical segments or one lobe. There was no additional morbidity or mortality associated with the resection compared with CBD exploration, nor was there any significant difference in disease control. Serendipitously, in one patient the liver resection identified an in-situ cholangiocarcinoma. Previous studies have described the value of liver resection in managing symptomatic hepatolithiasis. Lee et al.11 reviewed 123 patients who underwent hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis, with median follow-up of 40.3 months. Immediate stone clearance rate was 92.7% and final stone clearance rate 96%. Complication rate was 33.3%. Similarly, Chen et al. reported a 90% immediate stone clearance rate and 98% long-term stone clearance in a series of 103 hepatolithiasis patients who underwent hepatectomy, with a 28% complication rate.12

Three quarters of the surgical patients received a choledochojejunostomy with Hutson access loop as part of their procedure. The purpose of this loop is to provide a more direct route for percutaneous, retrograde access to the entire biliary tree for residual, or recurrent intrahepatic stones. Interestingly, 15% of our patients had previously undergone a biliary-enteric anastomosis before their referral to our center. Creation of a Hutson loop did not appear to increase the morbidity of the operation. To date, the need to utilize the loop has arisen in only one third of patients (7/21) who had the procedure, similar to results described by others. Liu et al.13 found that 22/70 (23%) patients who had hepaticocutaneous jejunostomy for primary biliary stones required postoperative choledochoscopic removal of residual stones. Similarly, 12/41 (29%) patients with a loop for hepatolithiasis required use of the loop at a 27-month follow-up in another report.14

Failure to access and clear the stones occurred in three of the seven Hutson loop attempted utilizations. Those patients, plus one other who required percutaneous drainage of a caudate lobe abscess, constitute the 15% of surgical patients whose disease was not adequately treated with the surgical procedure alone. On the other hand, in 85% of patients the surgical strategy was successful in controlling their disease. The relatively short follow-up time in this study raises the possibility of underestimating recurrence rates. Nonetheless, given the improved outcome among patients who underwent surgery within the available follow-up period, this study supports the important role for surgery in the multidisciplinary management of patients with RPC and hepatolithiasis.

The prevalence of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) in our population was 12%, which is within the previously reported range of 5–18%;2,15 and the mortality for patients with CCA was high at 60%. This suggests an important role for long-term screening for CCA in RPC patients, in a manner similar to those with PSC. Although the surgical options selected in this study were primarily directed toward the management of the benign, acute inflammatory, and infectious complications of RPC, the increased risk of CCA needs to be considered in the management strategy. In the context of hepatolithiasis, cholangiocarcinoma tends to be located in the atrophic hepatic lobe and/or in lobes containing significant stones.16 The managing physician or surgeon must consider the increased risk of CCA in determining the role for liver resection in patients with RPC and hepatolithiasis. Unfortunately, most bile duct cancers in the setting of this disease are diagnosed at an advanced stage and are inoperable.2

Conclusion

Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis with hepatolithiasis is a chronic and progressive disease with significant morbidity and a high risk of cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery is an effective option and important component of multidisciplinary management of patients with this disease. Liver resection is useful in patients with stones or atrophy confined to one lobe or sector, and carries no apparent additional morbidity or mortality compared to CBD exploration and stone clearance alone. The construction of a choledochojejunostomy with Hutson access loop caries no additional morbidity and offers an additional approach to residual or recurrent stone formation.

We suggest the algorithm presented in Fig. 4 for approaching the management of patients with RPC and hepatolithiasis. Patients with extractable stones should have them removed, preferably by ERCP but otherwise by percutaneous approach. Those whose stones are not extractable by either of these methods would need surgical exploration of the CBD with extraction of stones. If they have lobar atrophy and/or stones confined to one lobe, they would likely require liver resection in addition to the CBD exploration. We recommend the choledochojejunostomy with Hutson loop construction for all patients who undergo surgery.

References

Lo CM, Fan ST, Wong J. The changing epidemiology of recurrent pyogenic cholangitis. Hong Kong Med J 1997;3:302–304.

Mori T, Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Management of intrahepatic stones. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2006;20(6):117–1137.

Pitt HA, Venbrux AC, Coleman J, Prescott CA, Johnson MS, Osterman FA, Cameron JL. Intrahepatic stones—the transhepatic team approach. Ann Surg 1994;219(5):527–537.

Harris HW, Kumwenda ZL, Sheen-Chen S-M, Shah A, Schecter WP. Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis. Am J Surg 1998;176:34–37.

Cosenza CA, Durazo F, Stain SC, Jabbour N, Selby R. Current management of recurrent pyogenic cholangitis. Am Surgeon 1999;65(10):939–943, Oct.

Stain SC, Incarbone R, Guthrie CR, Ralls PW, Rivera-Lara S, Parekh D, Yellin AE. Surgical treatment of recurrent pyogenic cholangitis. Arch Surg 1995;130(5):527–532, May.

Thinh NC, Breda Y, Faucompret S, Farthouat P, Louis C. Oriental biliary lithiasis. Med Trop 2001;61(6):509–511.

Zhu X, Zhang S, Huang Z. The trend of gallstone disease in China over the past decade. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 1995;33(11):652–658.

Lam SK. A study of endoscopic sphincterotomy in recurrent pyogenic cholangitis. Br J Surg 1984;71(4):262–266.

Sperling RM, Koch J, Sandhu JS, Cello JP. Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis in Asian immigrants to the United States: Natural history and role of therapeutic. Dig Dis Sci 1997;42(4):865–871.

Lee TY, Chen YL, Chang HC, Chan CP, Kuo SJ. Outcomes of hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. World J Surg 2007;31(3):479–482.

Chen DW, Tung-Ping Poon R, Liu CL, Fan ST, Wong J. Immediate and long-term outcomes of hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. Surgery 2004;135(4):386–393.

Liu CL, Fan ST, Wong J. Primary biliary stones: Diagnosis and management. World J Surg 1998;22(11):1162–1166.

Fan ST, Mok F, Zheng SS, Lai EC, Lo CM, Wong J. Appraisal of hepaticocutaneous jejunostomy in the management of hepatolithiasis. Am J Surg 1993;165(3):332–335.

Chen MF, Jan YY, Wang CS, Jeng LB, Hwang TL, Chen SC, Chen TJ. A reappraisal of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with hepatolithiasis. Cancer 1993;71:2461.

Kim JH, Kim TK, Eun HW, Byun JY, Lee MG, Ha HK, Auh YH. CT findings of cholangiocarcinoma associated with recurrent pyogenic cholangitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;187(6):1571–1577.

Acknowledgment

We thank Allison Foster and Marlene Kennedy for their assistance in data acquisition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Sukhni, W., Gallinger, S., Pratzer, A. et al. Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis with Hepatolithiasis—The Role of Surgical Therapy in North America. J Gastrointest Surg 12, 496–503 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-007-0398-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-007-0398-2