Abstract

This paper analyses the challenges created by the liability of foreignness and the associated country-of-origin bias and their effect on Western managers’ decisions about whether to leave following their company’s acquisition by an emerging-economy multinational. Using a manipulated scenario-based survey conducted with American, French and German managers, the results show that managers are more likely to resign if their company is acquired by a company from an emerging economy (specifically, China or India) than by a company from their home or another Western, developed country. Furthermore, the results do not support previous research findings that show the role of prior alliance between the acquirer and its target, previous experience with successful acquisitions, previous experience with the local market and minimal post-acquisition integration to be forces helping to counterbalance the adverse effects of the liability of foreignness, country-of-origin bias and the ‘emergingness’ nature of foreign acquirers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

To what extent would Western managers choose to resign if their company were suddenly taken over by a foreign multinational? Would their intention to leave be higher in cases of acquisition by foreign companies than in purely domestic acquisitions? And, would this intention be significantly higher if the acquisition were by a Chinese or Indian company?

These three questions deal first with the liability of foreignness (LOF), which represents the additional costs arising from operating across national boundaries and large geographic distances in countries with unfamiliar environments (Zaheer 1995), which can have adverse consequences on post-acquisition performance due to an increase in the loss of key target company managers. The negative reactions and subsequent higher departure rate of target company managers when the acquiring company is a foreign multinational are considered to be one of the factors of the LOF (Krug and Nigh 2001; Krug 2003).

Moreover, the three questions posed above suggest that the importance of the LOF may vary from one foreign acquirer to the other: whereas all multinationals are subject to the LOF, some foreign acquirers seem to be more ‘foreign’ than others (Sauvant et al. 2009). According to this perspective, emerging-economy acquirers, especially Chinese- and Indian-owned companies, may suffer from the additional “costs of doing business abroad” (Zaheer 1995, p. 342).

National cultural differences, psychic and geographic distances, and the acquiring company’s general unfamiliarity with the local environment may produce adverse reactions in target company managers leading to a high likelihood that they will make a decision to resign (Buckley et al. 2012; Forsgren 2002; Chatterjee et al. 1992; Johanson and Vahlne 1977; Krug and Nigh 2001; Larsson and Lubatkin 2001; Schweiger and Very 2003). However, other factors related to the foreign acquirer’s home country and target company managers’ unfavourable perceptions of it may also contribute to costs and hurdles for foreign acquirers. When a foreign acquisition is conducted, local managers often, for instance, form an opinion of the acquirer based on stereotypes and a negative national image.

The foreign acquirer’s home country and the target company managers’ (favourable or unfavourable) perceptions of it are two underlying factors of the LOF. They are included in the list of sources of LOF—specifically defined by Zaheer (1995, p. 343) as “costs resulting from the host country environment” and “costs from the home country environment”—and directly affect the relative importance of the LOF to foreign acquirers depending on their country of origin. These two factors have to be analysed jointly as the extent of the impact of the LOF will differ according to the varying perceptions that managers of different host countries might have of an acquirer’s country of origin. As a consequence, different combinations of home country/host country may lead to a higher or lower LOF.

The influence of perceptions of the foreign acquirer’s home country on management reactions within the target company can be particularly problematic when the acquisition is conducted by newly globalised emerging-economy companies. Emerging-economy acquirers may suffer from negative images and stereotypes generated by a combination of country-of-origin bias and the very nature of their “emergingness” (Madhok and Keyhani 2012). As pointed out by Thite et al. (2012, p. 253), “The MNCs [multinational companies] from emerging economies face a ‘double hurdle’ of liability of foreignness and liability of country of origin with perceived poor global image of their home country”. In the context of cross-border acquisitions, this ‘double hurdle’ may result in a higher LOF relative to foreign acquirers from more developed countries or regions of the world.

The aim of this paper is to support this hypothesis and demonstrate that in the context of target companies from developed countries (e.g., Western companies), emerging-economy acquirers, especially Chinese- and Indian-owned companies, experience a significantly higher LOF than companies from elsewhere in the world. We examine this hypothesis using a sample of 252 managers from three major developed economies (France, Germany and the US) who were asked to share their decisions about whether they believed they would stay or leave their companies in different takeover scenarios. Since this research is focused on potential future decision making, we employed the policy-capturing method. Through the use of a series of manipulated scenarios, this survey method allowed us to predict whether French, German and US managers would be more likely to leave their job if their existing employer were to be acquired by a Chinese- or Indian-owned company as opposed to a locally-owned company or a company from another Western country (i.e., a European acquirer for US managers or a US acquirer for French and German managers).

In order to further isolate and analyse the importance of the LOF to emerging-economy acquirers, we examined whether the direction and magnitude of Western manager reactions are likely to differ (1) when the acquirer and its target are known to each other through a previous inter-organisational alliance, (2) when the acquirer’s top management is experienced in successful acquisitions, (3) when the acquirer has previous experience with the local market (or with the target company’s domestic market), and (4) when the target company is to be preserved or assimilated by the acquirer. The inclusion of these moderating variables is important because they are commonly viewed in the acquisition research literature as key determinants of the target company’s employee reactions at early post-acquisition stages. More specifically, (1) these four acquisition-related dimensions may be considered as pre-acquisition due diligence tools (Arend 2004) helping potential acquirers to better understand the target’s organisation and culture and to reduce information asymmetries, which in turn may decrease the likelihood of adverse selection; and (2) when combined with the question of the target company’s preservation or autonomy, they may facilitate the development of mutual awareness and familiarity between the acquirer’s as well as the target’s management teams, thereby enhancing the acquirer’s image and reputation and mitigating the risk of post-acquisition culture clashes and key talent loss (Stahl et al. 2003; Stahl and Sitkin 2010; Very et al. 1997; Zaheer et al. 2010). Hence, we examined the role of prior alliance, experience with successful acquisitions, local market experience and the degree of post-acquisition integration as possible forces able to counterbalance the degree of LOF to be borne by emerging-economy acquirers.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. First, we review the extant literature on the relationship between an acquirer’s LOF and target company managers’ perceptions of the acquirer’s country of origin and its influence on their decisions on whether or not to leave. Next, we introduce four common factors from the established acquisition literature stream in order to analyse whether they produce any significant moderating effects on the post-acquisition retention of key talent. Based on this information, we formulate five sets of research hypotheses. We then test the hypotheses and present the statistical results. The main findings and limitations of the paper, as well as directions for future research, are discussed in the final section.

2 Hypothesis Development

2.1 Liability of Foreignness and Country-of-Origin Bias in the Context of International Acquisitions

“The odds that executives will leave increase significantly when a firm is acquired by a foreign multinational” (Krug and Nigh 2001, p. 85). Building on this finding, literature dealing with the human side of acquisitions has begun to examine the adverse consequences this contributes to the LOF. According to the literature, when high numbers of managers resign following an acquisition by a foreign company there is an associated loss of managerial knowledge, social capital (Kiessling et al. 2008) and “leadership continuity” (Krug 2003). The loss of these critical organisational resources can create a shock wave throughout the target company resulting in additional stress and anxiety among lower-level employees, thus prompting them to leave as well (Krug and Nigh 2001). This high loss of key staff is very likely to disrupt the post-purchase integration process, thereby jeopardising the future performance of the acquisition (Buono and Bowditch 1989; Butler et al. 2012).

Many studies in this literature stream have therefore assessed the adverse impact that the LOF can have on the unsolicited post-acquisition exodus of managers, and have compared it to the general liability of acquisition. Such studies show, first, that post-acquisition managerial departure in domestic (i.e., non-international) acquisitions is significantly higher than ‘normal’ management departure rates unrelated to acquisition, often reaching as high as 60% within the first 5 years (Walsh 1988). Second, they reveal that in the first 5 years following cross-border acquisitions the likelihood that acquired company managers will leave goes up even higher to 75% (Krug and Nigh 2001; Krug 2003).

Negative reactions and subsequent higher management departure rates are often attributed in the literature to well-established factors of the LOF, such as national cultural differences, psychic and geographic distances, and, more generally, unfamiliarity with the local environment (Chatterjee et al. 1992; Krug and Nigh 2001; Larsson and Lubatkin 2001; Schweiger and Very 2003). However, other elements contributing to the LOF related to the acquirer’s country of origin and the way in which it is perceived may also negatively influence reactions and increase the likelihood of target company managers choosing to leave. In their numerous studies on employees’ reactions to international acquisitions, Stahl and colleagues (Stahl et al. 2003; Stahl et al. 2011; Stahl and Sitkin 2010) find that among the significant criteria affecting the positive or negative perceptions of employees experiencing a takeover, the attractiveness of the foreign acquirer’s structure and internal human resource system scores higher than the often-championed four classic indicators of acquisition success: prior relationship between the acquirer and its target, type of post-acquisition control, mode of takeover and cultural differences (Buono and Bowditch 1989). Perceptions of the acquirer’s structure and internal systems play a key role in influencing target company managers’ reactions and these perceptions are, in turn, influenced by the host country’s perceptions of the foreign acquirer’s country of origin. Dependent upon the shifting nature of global alliances, geopolitical affairs and changing public perceptions, a company’s country of origin may be perceived in either a positive or negative light (Bell et al. 2012). The fact that a negative bias can be generated based solely on the host country’s perceptions of a company’s country of origin is an underlying component of the LOF. A striking example of how country-of-origin perceptions can dramatically change was illustrated by the recent scandal in the US faced by the German automobile manufacturer Volkswagen. Following the company’s admission of knowingly falsifying emissions test results on their diesel-powered cars, the perception previously shared by many Americans that Germans make cars that are the best in their class (i.e., a positive country-of-origin bias) was suddenly in danger of being changed to one of scepticism of all German-made cars (i.e., a negative country-of-origin bias).

The country-of-origin-biased perceptions of local staff may significantly increase the impact of the LOF on some internationalising companies (Sauvant et al. 2009). Further, the foreign acquirer’s nationality and host country company managers’ perceptions of it may influence positive or negative views on the acquirer’s acquisition experience, its ability to conduct post-acquisition integration, its past acquisition successes and failures, and, more generally, its attractiveness and credibility as a future employer.

2.2 Liability of Foreignness and Country-of-Origin Bias Affecting Chinese and Indian Acquirers in Western Countries

There are many differences between the various nations and associated companies included under the heading ‘emerging economies’. However, when analysing their expansion into foreign markets, especially developed Western countries, the adverse effects of country-of-origin bias is exacerbated by the fact that many of these companies are new to Western managers and relative latecomers to globalisation (Ramachandran and Pant 2010; Ramamurti 2009). Thus, in the case of emerging-economy companies’ foreign direct investment (FDI) into Western economies, country-of-origin bias may compound the traditional costs and disadvantages associated with the LOF.

As mentioned above, Western managers often lack awareness and are distrustful of emerging-economy companies, their acquisition experience, their acquisition success rate, and their post-acquisition management practices (Klossek et al. 2012). Whereas no multinationals undertaking an acquisition in a Western country automatically benefit from a positive acquisition reputation among target company managers, emerging-economy acquirers seem to be collectively plagued by a widespread diffusion of negative perceptions. Consider, for example, the response of a senior French manager when asked about the likelihood of their company being acquired by a Chinese or Indian multinational:

If my company is absorbed by another company, I will naturally look for opportunities in other firms […]. My feeling, I guess, will be naturally influenced by the nationality of the owner of the new entity […]. For Chinese and Indian companies, I will say that it is my lack of knowledge regarding management practices that will make me fear for the future of my job (survey response).

As indicated in both the above quotation and in previous research, the prospect of working for an emerging-economy company may not be well perceived by many Western managers (Alkire 2014). In Germany, for example, it is estimated that Chinese parent companies now own over 60 subsidiaries, employing some 5000 employees (German Federal Bank 2014). Yet Alexander Tirpitz, a China expert and founder of the German Center for Market Entry, says this about the perceptions of German managers and workers of Chinese-led acquisitions: “Chinese investors have a miserable image. It is often falsely assumed that following a takeover all of the production equipment will be dismantled and shipped back to China. This [image exists] even though such a case is not known”Footnote 1 (Ziegert and Hug 2011).

Emerging economies are often seen in Western countries as fast-growing markets, but they can also be portrayed as environments with a high degree of corruption, underdeveloped market mechanisms, strong government intervention and insufficient legal and regulatory conditions (Chang et al. 2009; Hoskisson et al. 2000; Khanna and Palepu 2006; Thite et al. 2012). As Western managers may have little knowledge of emerging-economy companies, their perceptions and opinions may be subject to cognitive shortcut mechanisms and influenced by a country-of-origin bias based mostly on a generalised national image and stereotypical representations (Ramachandran and Pant 2010). As a consequence, they may associate such companies’ acquisition and post-acquisition integration practices with these perceptions. Negative national stereotypes may contribute to an adverse bias that may also be a result of a general lack of transparency, a perceived failure to establish corporate legitimacy, the aggressive nature of previous, high-profile acquisitions and an internationalisation strategy driven mostly by national interests (Bangara et al. 2012; Klossek et al. 2012). However, as pointed out by Luo and Tung (2007, p. 494), “when global stakeholders harbor stereotypes about poor governance of firms in emerging markets, even some well-governed EM MNEs [emerging market multinational enterprises] could fall victim to such negative images”.

Unfavourable perceptions of the country of origin of an emerging-economy acquirer can be expected to be deep seated and pessimistic and contribute to a higher LOF. As Cartwright and Price (2003, p. 84) maintain, “as a frame of reference, the emotional nature of stereotypes can often override logic and lead to irrational decisions”. The combination of these negative dimensions increases the LOF, often creating an atmosphere of panic and fear among Western target company managers, leading them to make emotional decisions. This higher LOF may result in managers perceiving the emerging-economy acquirer to be an undesirable employer, and if “they expect the acquisition to affect them negatively; they are likely to exhibit nonproductive behaviors, even quit the organization” (Davy et al. 1988, p. 58).

We thus hypothesise that a higher LOF resulting from such unfavourable perceptions will contribute to a significantly higher level of undesired post-acquisition loss of managerial talent through voluntary resignation. Furthermore, we hypothesise that a target company manager will be more likely to leave their job if their existing employer were to be acquired by a Chinese- or Indian-owned company as opposed to a locally owned company or a company from another Western developed economy (i.e., a European acquirer for Americans or a US-owned acquirer for Europeans). Hypotheses 1a, 1b, 1c and 1d are therefore stated thus:

Hypothesis 1a: the post-acquisition resignations of target company managers will be higher when the acquirer is a Chinese company.

Hypothesis 1b: the post-acquisition resignations of target company managers will be higher when the acquirer is an Indian company.

Hypothesis 1c: the post-acquisition resignations of target company managers will be lower when the acquirer is a domestic company.

Hypothesis 1d: the post-acquisition resignations of target company managers will be lower when the acquirer is a developed-economy company.

2.3 Moderating Effect of Prior Alliance

A prior alliance between the acquirer and its target can play a crucial role in the ultimate success or failure of an acquisition (Arend 2004; Stahl and Sitkin 2010; Zaheer et al. 2010). First, a prior inter-organisational relationship, and, more generally, connections with various stakeholders involved in the target company’s business system provide useful information for the acquirer. Pre-existing long-term alliances between the acquirer and the target company creates mutual understanding between the respective management teams of each other’s organisations and corporate culture. Long-term alliances may also help both sides of the acquisition to identify any prospective problem areas, thereby decreasing information asymmetries and reducing potential post-acquisition hindrances, such as interpersonal conflicts and the unwanted resignation of key managers (Arend 2004; Porrini 2004). Second, prior alliances can facilitate the development of relationships based on mutual awareness and familiarity between the acquirer’s management team and target company employees (Stahl and Sitkin 2010). A long history of previous interactions and/or collaborations is particularly helpful in reducing suspicion and mistrust between the acquirer’s management team and target company employees (Stahl and Sitkin 2005).

Information gathering and establishing familiarity are thus expected outcomes of a prior alliance between the acquirer and the target company (Klossek et al. 2012). It helps to reduce the country-of-origin bias and related emerging-economy acquirers’ international operations costs, thus moderating the adverse effects of the LOF which contributes to the unwanted loss of Western managers following an acquisition. The counterbalancing function of a prior alliance relies on the assumption that the collaborative process encourages target company managers to judge the emerging-economy acquirer not only on stereotypical perceptions of its country of origin but also on its (perceived and real) organisational dimensions. In addition, a prior alliance can be viewed as a reversed due diligence tool allowing target company managers to assess the emerging-economy acquirer’s potential, resources and capabilities. Repeated exposure to and interaction between alliance partners provides them with the opportunity to check whether acquirer managers have the experience and skills required to successfully manage the acquisition and post-acquisition integration processes. If this reversed due diligence leads to positive and favourable perceptions and conclusions, it will leave the emerging-economy acquirer in a strong position. If the reversed due diligence turns out to be negative, target company managers may be relied upon to play a more active and enabling role than they would in a more traditional acquisition and post-acquisition integration process. In such a context, the emerging-economy acquirer may rely on the mutual awareness and familiarity established during the pre-acquisition alliance (1) to grant a broad managerial autonomy to the acquired company and (2) to greatly enhance the role of target company managers following the acquisition.

In summary, a prior alliance and the knowledge it provides may help target company managers to perceive the emerging-economy acquirer as a more desirable future employer. Therefore, we can formulate a second set of hypotheses predicting a moderating effect of prior alliance on the LOF–country of origin relationship and the target company managers’ decisions to stay or leave following an acquisition:

Hypothesis 2a: a prior alliance between the acquirer and the target company will be a significant moderator of post-acquisition resignations of target company managers when the acquirer is a Chinese company.

Hypothesis 2b: a prior alliance between the acquirer and the target company will be a significant moderator of post-acquisition resignations of target company managers when the acquirer is an Indian company.

2.4 Moderating Effect of Previous Experience with Successful Acquisitions

Another important factor influencing an undesired post-acquisition exodus of target company managers is whether or not the acquirer has a positive track record with previous cross-cultural acquisitions (Shenkar 2001). For any acquirers, a positive track record with international acquisitions indicates that a company (1) is able to successfully and repeatedly manage the human, organisational and cultural challenges faced during the post-acquisition integration phase; (2) has initiated a learning process and learned lessons from such repeated experiences over time; and (3) has developed an “acquisition capability” (Zollo and Winter 2002), which is often linked to the existence of multi-functional teams of “acquisition veterans” (Marks and Mirvis 2001).

Various studies have shown that, over time, companies with high levels of cross-border acquisition experience gain the capability of incorporating higher levels of human, organisational and cultural sensitivity as a means of resolving post-acquisition integration issues (Dikova and Rao Sahib 2013; Morosini et al. 1998; Very et al. 1997). Such studies indicate that, over time, experienced acquirers are more able to identify their cultural differences with target companies, anticipate any resulting cultural collision and adapt integration procedures to the target company’s human and cultural context than less experienced acquirers. Dikova and Rao Sahib (2013) find support for the moderating effect of the acquirer’s level of cross-border acquisition experience on the negative relationship between acquirer-target cultural distance and post-acquisition performance. This is also supported by Shenkar (2001), whose research indicates that acquirers may be able to mitigate the negative impact of cultural distance through the accumulation of knowledge and know-how derived from multiple experiences with cross-border acquisitions. Further, some studies show that prior successful cross-border acquisition experience can mitigate the stress, anxiety and resistance of target company employees. It has been observed in these studies that acquirer managers with acquisition experience (acquisition veterans) are more likely to engage in culturally sensitive pre- and post-acquisition communication and practices, thus rendering the acquirer and the post-acquisition integration process less threatening in the eyes of target company employees (Shenkar 2001; Very et al. 1997).

We thus propose that emerging-economy companies having conducted previous successful acquisitions and having managed the tension and discontent resulting from a cross-border acquisition, will develop a more positive acquisition reputation allowing them to reduce the costs associated with the LOF and country-of-origin bias, and thus moderate the unwanted departure of target company managers in Western countries. We argue further that the adverse effects of the LOF and country-of-origin bias will be stronger when emerging-economy acquirers have had no previous successful acquisition history. It is therefore hypothesised that the positive acquisition reputation gained from emerging-economy acquirers with successful acquisition experience will lead to the perception that they are more attractive future employers than companies with no previous successful acquisition experience:

Hypothesis 3a: previous experience in successful cross-border acquisitions by the acquirer’s management team will be a significant moderator of post-acquisition resignations of target company managers when the acquirer is a Chinese company.

Hypothesis 3b: previous experience in successful cross-border acquisitions by the acquirer’s management team will be a significant moderator of post-acquisition resignations of target company managers when the acquirer is an Indian company.

2.5 Moderating Effect of Previous Experience with Local Market

Experience with previous investments and transactions in the same local market, whatever the investment mode (wholly owned subsidiary, joint venture with a local partner or acquisition), is another key acquisition-related dimension. Such experience allows emerging-economy acquirers (1) to develop country-specific knowledge and (2) to build up local legitimacy, which together may reduce costs associated with foreignness and country-of-origin bias.

A learning process is usually generated on the basis of these cumulative investments and transactions, allowing foreign companies to better understand the human, organisational and cultural specificities of the host country (and its companies) and to properly manage local operations (Meschi and Métais 2015; Very et al. 1997). The country-specific knowledge resulting from the learning process can significantly reduce both the likelihood of cultural collision between an acquirer and their target and the level of suspicion of target company employees towards their future employer. Repeated exposure to the local market should enhance the acquirer’s capability of resolving cross-cultural issues in the post-acquisition process. In addition, foreign companies enjoying a strong local presence can rely on experienced and trusted local or bi-cultural managers who can play a significant role in the transference of positive signals for the motivation of target company employees following the announcement of the acquisition (Weber et al. 1996).

Previous research supports the relationship between the acquirer’s local experience and post-acquisition performance. For instance, Li’s (1995) study of the survival and successful performance of foreign acquisitions by multinational companies finds that acquirers with previous experience in the target country have a higher success rate in managing subsequent acquisitions in that country.

Furthermore, these accumulated investments in the local market and the consequent stronger local presence of emerging-economy companies may help to enhance their local legitimacy and progressively create a ‘quasi local player’ image in the eyes of local customers, companies, government and employees. The establishment of such an image plays a critical role which can positively affect the human and cultural side of a cross-border acquisition. As pointed out by Teerikangas (2012, p. 618), “once the news of the buying firm is known, employees began to speculate on ‘Who is the buyer?’ and ‘What is the buyer like?’ An immediate concern therein relates to whether the buying firm is known to the target firm or not. The less the buying firm is known, the more suspicion it was found to arouse among acquired firm employees”.

Based on the above, we hypothesise that the acquirer’s previous experience with the local market will have a moderating effect on the LOF–country-of-origin relationship and the target company’s managers’ intention to leave or remain employed by the company:

Hypothesis 4a: an acquirer’s previous experience with the target market will be a significant moderator of the post-acquisition resignations of target company managers when the acquirer is a Chinese company.

Hypothesis 4b: an acquirer’s previous experience with the target market will be a significant moderator to post-acquisition resignations of target company managers when the acquirer is an Indian company.

2.6 Moderating Effect of Post-Acquisition Integration

Acquisition research literature suggests that a target company’s employee perceptions of an impending acquisition are not always a predictable product of the change itself, but can be affected by the acquirer’s behaviour and proposed future intentions (Teerikangas 2012). A pivotal intention is the degree of assimilation or preservation that the acquirer has in mind for the target company. This degree of integration between the acquirer and its target has been defined as “the degree of post-acquisition change in an organization’s technical, administrative, and cultural configuration” (Pablo 1994, p. 806). It is based on the level of autonomy that the acquirer is planning to allow the target company. As defined by Datta and Grant (1990, p. 31)”, autonomy, in the context of acquisitions, can be described as the amount of day-to-day freedom the acquired firm management is given to manage its business”. Integration is therefore pivotal to the development of post-acquisition value creation, and the model of integration used during the process is directly tied to the subsequent success or failure of the acquisition (Pablo 2007).

In making their decision on which kind of post-acquisition integration to implement, the management of emerging-economy acquirers have two fundamental choices: either control and preserve the target company from a distance with a minimum degree of integration, or absorb and assimilate the acquired company into the parent company, thus replacing the culture, routines and procedures of the acquired company with those of the acquirer (Marks and Mirvis 2001).

Nahavandi and Malekzadeh (1988) argue that regardless of the degree of post-acquisition integration intended, a major consideration of the target company’s management is the evaluation of the desire to preserve their own culture versus the attractiveness of the acquirer’s cultural practices. The level of post-acquisition stress will be highest when the target company managers’ strong desire to protect their existing culture coincides with the acquirer’s call for a significant degree of organisational integration (Seo and Hill 2005). In the case of many emerging-economy acquirers, a stereotypical image of their home country may be the default used by the employees of most Western target companies to evaluate the attractiveness of the acquirer’s organisational culture (Luo and Tung 2007).

When considering the impact of a proposed acquisition, the degree of intended post-acquisition integration, whether preservation ‘as is’ or total assimilation, will be viewed by the managers of the target company from the point of view of how it impacts their own unit (Vaara 2003). Previous studies have found that the higher the degree of intended integration (i.e., the greater the perceived loss of autonomy by the target company’s managers) the greater the likelihood that target company managers will feel helpless and hostile (Datta and Grant 1990; Pablo 1994; Stahl and Sitkin 2010; Stahl et al. 2012). As Very et al. (1997, p. 596) suggest, “the lowest performance outcomes [from an international acquisition] may occur when the buying firm is perceived as holding an undesirable culture and is seen as aggressively removing the acquired executives’ autonomy”. This means that acquirers announcing that the target company’s culture, routines and procedures will be fully assimilated (i.e., that there will be no post-acquisition autonomy) will be seen as less attractive employers by the target company’s managers than acquirers intending to fully preserve the target company’s autonomy. Further, the development of resistance, and possibly even hostility, in target company employees resulting from tighter post-acquisition control procedures and autonomy removal (Kiessling et al. 2008) is likely to be exacerbated if the acquirer is an emerging-economy company. On the basis of the above, we therefore formulate a final set of hypotheses predicting that the degree of intended post-acquisition integration will have a moderating effect on the LOF–country-of-origin relationship and the unwelcome loss of target company management talent:

Hypothesis 5a: the preservation by the acquirer of the target company’s culture and autonomy will be a significant moderator of the post-acquisition resignations of target company managers when the acquirer is a Chinese company.

Hypothesis 5b: the preservation by the acquirer of the target company’s culture and autonomy will be a significant moderator of the post-acquisition resignations of target company managers when the acquirer is an Indian company.

3 Methods

The primary focus of this paper is to determine if the loss of target company management through unwanted resignations is greater when the acquirer is from an emerging economy than in acquisitions by locally owned or developed-economy companies. To this end, we focused on acquisitions conducted by Chinese- and Indian-owned companies and we surveyed American, French and German managers on their intentions to either stay with or leave their companies using a policy-capturing method. We chose to conduct our survey in France, Germany and the US because they are all members of the original G-6 group of developed nations, and companies from these three countries have all been heavily involved in cross-border acquisitions for many years (Vasconcellos and Kish 1998). The focus on Chinese and Indian acquirers as an illustration of outward FDI from emerging economies, the final sample of surveyed managers, the rationale for the use of the policy-capturing method and the variables used are discussed below.

3.1 Focus on Chinese and Indian Acquirers as an Illustration of Emerging-Economy Foreign Direct Investment

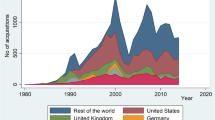

We decided here to focus on the specific context of acquisitions conducted by Chinese- and Indian-owned companies in Western countries for the following reasons. First, China and India have so far been the most active in pursuit of FDI in developed nations (Economist 2010). The increase in FDI activity in 2013 consisted of a total of 313 projects. Of these, 153 were conducted by Chinese and 103 by Indian companies. Furthermore, of the 16,900 jobs created by emerging-economy FDI in 2013, the vast majority (84%) were created by Chinese (7135) and Indian (7000) companies (Ernst and Young 2014). As such, this study will consider Chinese and Indian companies as being representative of the phenomenon of emerging-economy outbound FDI.

Further support for our focus on Chinese- and Indian-owned companies is provided by the most recent report (2014) of the United Nation’s Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) on global FDI. UNCTAD forecasts the most promising sources of outbound FDI and reports that China was selected in a survey of 80 diverse investment promotion agencies to be the second most likely source of FDI during the 2014–2016 period. India was in sixth place following the developed economies of Japan, the United Kingdom and Germany.

3.2 Sample

We initially asked 2720 managers from two online professional networking sites (LinkedIn in France and the US and XING in Germany) to participate in our survey. We sent contact requests/survey invitations on a random basis to individuals who were working at all managerial levels in established organisations. Managers working in situations where an acquisition by a foreign company would not be a plausible scenario, such as those who were self-employed or employees of governmental and not-for-profit organisations, were not contacted. Approximately 900 contact requests/survey invitations were sent out to managers in each of the three countries. A total of 1046 managers expressed an interest in completing the survey. From this initial sample we then received 336 surveys (32% of initial sample), of which 84 were removed due to inconsistencies or missing data. The participants were further selected based on their nationality so that the sample population was evenly divided between the three nationalities: French, German and US.

This process resulted in a final sample of 252 respondents (84 from each of the three nationalities) from 225 different companies involved in 12 primary industries: service (42%), manufacturing (20%), high technology and communications (13%), food and beverage (5%), aerospace (5%), energy (4%), medical and pharmaceutical (4%), engineering and construction (3%), luxury goods (2%), and consumer goods (2%).

3.3 Policy-Capturing Method and Manipulated Scenario-Based Survey Instrument

The policy-capturing method, which enables an analysis of the way in which people reach decisions, was applied to determine the judgment criteria used by managers faced with the decision to remain or leave a company following its unanticipated acquisition by a company from one of the following: an emerging economy, a locally owned company, or a company from a developed economy. Policy capturing is used in a variety of decision-based research studies, including those modelling strategic acquisition assessments of executives (Stahl and Zimmerer 1984); the decisions made during the goal-setting process (Hollenbeck and Williams 1987); the decisions involving job, group and organisational fit (Kristof-Brown et al. 2002); the institutional effects on strategic alliance partner selection in emerging economies (Hitt et al. 2004); strategic decision making in mergers and acquisitions (Pablo 2007); and the decision to persist with underperforming alliances (Patzelt and Shepherd 2008).

Policy capturing allows the researcher to analyse decision-making behaviour by means of ‘real-life’ scenarios that are more focused than the comparatively abstract questions asked in opinion surveys (Dülmer 2007). Policy capturing, or conjoint analysis, also affords the researcher the ability to conduct “a posteriori decomposition” of the decision process as the respondents are asked to make an actual decision based on the information given in the scenarios (Cooksey 1996). This enables real-time data on the judgments of the respondents, based on having several decision criteria presented to them selected from the literature on mergers and acquisitions, to be collected (Priem and Harrison 1994). One of the main advantages of policy capturing is that the method can be used not only to examine individual decision making but also in group analysis (Karren and Woodard Barringer 2002). According to Karren and Woodard-Barringer (2002, p. 338), “the method overcomes many of the limitations inherent in other, more direct approaches… [and] asking individuals to make overall judgments about multi-attribute scenarios is more similar to actual decision problems, and [is] hence more realistic”.

Consistent with the policy-capturing method, we developed a survey instrument comprising different manipulated scenarios based on five judgment criteria as well as questions on the respondent’s individual characteristics and company. The five judgment criteria used in the survey were: (1) the acquirer’s geographical country of origin, which was randomly switched from one of four possibilities: India, China, local, US (for French and German respondents) or European (for American respondents); (2) the existence of a prior alliance between the acquirer and its target, which was measured using two possibilities: ‘the acquirer is known to your company through a previous strategic alliance’ or ‘the acquirer is unknown and has had no previous dealing with your company’; (3) the level of the acquirer’s experience with successful acquisitions, which was measured using two possibilities: ‘the acquirer’s management team is experienced in managing the tension and discontent resulting from an acquisition’ or ‘the acquirer’s management team is not experienced in managing the tension and discontent resulting from an acquisition’; (4) the level of the acquirer’s experience with the local market, which was measured using two possibilities: ‘the acquirer has previous experience operating in your country’ or ‘the acquirer has no previous experience operating in your country’; (5) the degree of intended post-acquisition integration of the target company, which was measured using two possibilities: ‘your company’s culture, brand, identity and products will be fully assimilated by the acquirer’ or ‘your company’s culture, brand, identity and products will be fully preserved by the acquirer’.

A sample of one of the scenarios is shown in Fig. 1. The cues shown in bold within the < > symbols present the five judgment criteria used in this study. The actual individual scenarios were presented to the respondents in a random format that contained one of each of the decision criteria.

Since there are numerous other factors that may come into play when news of an acquisition is received, the overall description of the situation given within the context of each scenario was that the respondent had also recently been given a standing job offer from the CEO of a competitor company. The hypothetical offer of another job opportunity outside the respondent’s company is consistent with the reality of many key managers who are highly likely to be attractive to other employers and have the power to leave the company for other job opportunities (Kiessling et al. 2012). This manipulation was included to allow greater survey participant concentration on the various possibilities presented in the scenarios by removing any potential of the respondent feeling trapped in their job.

When designing a decision-making experiment using policy capturing, researchers are faced with the dilemma of whether to use a full factorial design or a confounded or fractional factorial design (Karren and Woodard Barringer 2002). The advantage of a full factorial design is the ability it provides to measure the independent effects of each variable as it relates to each respondent’s decision (Graham and Cable 2001). The typical disadvantage of a full factorial design is that with five or more judgment criteria the number of scenarios that respondents are required to read can become overwhelming (Aiman-Smith et al. 2002). In this study, a full factorial design would have presented each respondent with five cues, with the first cue having four levels and the remaining four having two (4 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2), amounting to a total of 64 decision-based scenarios per respondent (Gunst and Mason 1991). Initial pilot testing immediately indicated that 64 scenarios resulted in respondent fatigue and the refusal of many subjects to complete the survey. After completing a pilot study, which included interactive feedback from several subjects, it was determined that a full factorial design aimed at a general population of managers was not feasible given the budget and time constraints of this study.

The policy-capturing method typically relies on the assumption of orthogonality, wherein potential correlations between the five decision variables are not included and are assumed to be zero (Patzelt and Shepherd 2008; see Table 1). This treatment is based on choosing primary constructs with inherent stand-alone qualities which, as demonstrated in the hypothesis development above, are associated with distinct notions to be found in the acquisition research literature. Due to the comprehensive nature of the hypothetical scenarios presented to the respondents and in order to construct an instrument of acceptable length while maintaining the orthogonality of the judgment criteria, a simulated experiment was designed using a fractional factorial survey. As suggested by Dülmer (2007), the specific number of scenarios was generated using the orthogonal design function of the software program IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0; a function designed specifically for fractional factorial designs. The orthogonal design function determined that the optimal level of scenarios for this study was 26 plus 2 duplicate test–retest scenarios for a total of 28. Given that each scenario has 5 cues, the 26 scenarios (plus 2 duplicates) presented to each respondent meets the recommended minimum scenario-to-cue ratio of 5 to 1 (Aiman-Smith et al. 2002; Cooksey 1996). The two replicated scenarios were inserted randomly within the survey in order to check for respondent fatigue and within-rater decision-making consistency. These 2 duplicates were not included in the data analysis. In synthesis, there were 26 decisions per respondent which in total corresponded to 6552 decisions nested within 252 respondents.

3.4 Variables

3.4.1 Dependent

This variable corresponds to the respondent’s likelihood to resign in the event of an unanticipated acquisition. Each scenario required the respondent to assume that their company was the target of an unanticipated acquisition. All the scenarios in the survey were concluded as follows: ‘Based on the information given in the scenario how likely is it that you would plan to actively pursue employment at another company?’ (see Fig. 1). Respondents had to assess this likelihood on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (‘highly unlikely’) to 7 (‘highly likely’).

3.4.2 Independent and Moderating

The acquirer’s country of origin constituted the independent variable. It corresponded to the first judgment criterion used to build the scenarios. There were four geographical categories of acquirers: Indian, Chinese, locally owned, and developed economy. In order to differentiate between these various acquirer’s countries of origin, we created four dummy variables: Chinese, Indian, locally owned (which matched the acquirer’s country of origin with that of the respondent), and EU or US (i.e., a European acquirer for American respondents or a US acquirer for European respondents). In establishing this baseline, it should be noted that the emphasis of this study was to compare companies from emerging economies such as China and India with companies from Western or developed economies. The use of the descriptor ‘European owned’ was considered sufficient to convey the desired status of ‘Western’ to the US survey respondents. Therefore, the option given to the US respondents of a generic EU- or European-owned company was based on this logic as well as on expediency (there are currently 28 EU countries). It is not our intention to imply that all European companies are perceived as being equal by American managers.

The four other judgment criteria, prior alliance, experience with successful acquisitions, experience with local market, and intended integration were considered potentially to have significant moderating effects on target company managers’ likelihood to leave. There were two categories of each judgment criterion: prior alliance—prior alliance/no prior alliance, experience with successful acquisitions—previous experience/no previous experience, experience with local market—previous experience/no previous experience, and intended integration—full assimilation/full preservation.

3.4.3 Control

Besides examining the impact of the judgment criteria, we also included control variables with the potential to affect the respondent’s likelihood to resign. Using the respondent’s individual characteristics, we first controlled for age (measured in years, logarithmically transformed), gender (binary variable, 1 for male and 0 for female), executive manager (dummy variable, 1 for respondents working at an executive management level and 0 otherwise), tenure with the current employer (measured in years, logarithmically transformed), and EU origin (binary variable, 1 if the respondent was of EU origin and 0 if from the US). Using company-specific data, we also controlled for industry (dummy variable, 1 for service and 0 otherwise), size (ordinal variable, 1 for companies with less than 500, 2 for companies with 500–1000, 3 for companies with 1000–5000 and 4 for companies with more than 5000 employees), ownership type (binary variable, 1 for publicly listed companies and 0 for private companies) and current competitive position (ordinal variable, 1 when the respondent ranked their company ‘below most competitors’, 2 when the ranking was ‘even with most competitors’, 3 when it was ‘above most competitors’ and 4 when ranked as ‘industry leader’).

3.5 Model Specification

The research hypotheses of this paper were analysed using hierarchical linear modelling (HLM) (Bryk and Raudenbush 1992). HLM is particularly well suited to the policy-capturing method used here because the 6552 decisions made in this experiment may not have been totally independent of each other and therefore an examination of within-respondent and between-respondent variance was warranted (Kristof-Brown et al. 2002; Patzelt and Shepherd 2008; Shepherd et al. 2013).

Since the sample consisted of three nationalities, a broad range of age and a diverse level of manager responsibility, it was felt safe to assume that there would be some differences between respondent decision-making models. The data collected is therefore hierarchical and consists of two levels. Level I data include the five judgment criteria (see Tables 2, 3, 4, 5) as presented to all respondents, regardless of individual and company-specific attributes. Level II data pertain to individual and company-specific attributes. As pointed out by Patzelt and Sheperd (2008, p. 1232), “Level I is the decisions of the individuals, Level II is the individuals”. In accordance with previous studies (e.g., Choi and Shepherd 2004; Hitt et al. 2004), once the research hypotheses were tested at Level I, they were subsequently tested with individual and company-specific control variables at Level II in order to check for between-respondent variance.

4 Results

4.1 Statistical Analyses

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix for all (dependent, independent, moderating and control) variables. As the five judgment criteria are orthogonally designed, their correlations are equal to zero.

Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5 present different series of HLM estimation in which the dependent variable (the respondent’s likelihood to resign in the event of an unanticipated acquisition) acts as the criterion against which the acquirer’s country of origin (India, China, local or developed economy) and the four other judgment criteria [prior alliance (see Table 2), experience with successful acquisitions (see Table 3), experience with local market (see Table 4), and intended integration (see Table 4)] are entered in the regression as predictors (see models 1a, 2a, 3 and 4 across all tables) and moderators (see models 1b and 2b across all tables). In all series of HLM estimation, Level II variables control for basic differences based on individual and company-specific data.

The results across all tables indicate that the likelihood that American, French and German managers will resign following an acquisition by a Chinese or an Indian company is positive and statistically significant (β = [0.82–0.87], p < 0.001 for a Chinese acquirer-model 1a and β = [0.35–0.38], p < 0.001 for an Indian acquirer-model 2a), thus supporting hypotheses 1a and 1b. Conversely, the regression coefficients for home country (see locally owned variable in model 3 across all tables) or developed-economy acquirer (see EU or US variable in model 4 across all tables) are negative and significant (at p < 0.001), thus supporting hypotheses 1c and 1d. Overall, results across all tables indicate that target company managers’ intention to resign following an acquisition is higher if the acquirer is from an emerging economy (China or India) than if the acquirer is from the home or a Western, developed-economy country.

To elaborate further on the findings and check whether the differentiated impact of an acquirer’s country of origin was statistically significant, we compared the regression coefficients in Table 2 for Chinese, Indian, locally owned, and EU or US variables using the z score technique proposed by Clogg et al. (1995). Table 3 presents z scores testing for the difference between two regression coefficients across the different models in Table 2. The z scores show that the likelihood that managers will choose to leave their job following an acquisition by an emerging-economy company is significantly higher than if the acquirer is from the home country (z = 7.65, p < 0.001 when compared to a Chinese acquirer and z = 4.66, p < 0.001 when compared to a an Indian acquirer) or a developed-economy company (z = 6.40, p < 0.001 when compared to a Chinese acquirer and z = 3.53, p < 0.001 when compared to an Indian acquirer). These results provide additional support to hypotheses 1a, 1b, 1c and 1d. Moreover, Table 6 presents other interesting findings. First, while the acquisition by an emerging-economy company had the most positive effect on increasing management intention to resign, this effect appeared to be significantly stronger with a Chinese than with an Indian acquirer (z = 2.49, p < 0.05). Second, the z score for locally owned and EU or US variables shows no significant difference in lowering the management’s intention to resign. As might be expected, the acquisition by a locally owned company had the most positive effect on reducing key management’s likelihood to choose to resign (β = −1.00, p < 0.001, see Table 2). However, this positive effect is not statistically distinguished from that observed for the acquisition by developed-economy multinationals (β = −0.65, p < 0.001, see Tables 2 and 6).

Models 1b and 2b across all tables indicate the test results for hypotheses 2a and 2b through to 5a and 5b which predict the moderating effects of prior alliance (hypotheses 2a and 2b), experience with successful acquisitions (hypotheses 3a and 3b), experience with local market (hypotheses 4a and 4b) and intended post-acquisition integration (hypotheses 5a and 5b) on the LOF–country-of-origin relationship and the likelihood of target company managers to resign. When regressed as stand-alone variables, the only traditional acquisition-specific variable displaying a significant moderating effect is an existing prior alliance. As shown in Table 2, the prior alliance variable is significant across all models. In order to test directly for Chinese- and Indian-owned acquirers, two interaction variables were created: Chinese × prior alliance and Indian × prior alliance. The results of these variables, which are included in Table 2, indicate that the interaction coefficient of prior alliance is not statistically significant for either Chinese- or Indian-owned companies. In other words, we did not observe any significant moderating effects of prior alliance when the acquiring company was an emerging economy company, thus hypotheses 2a and 2b are not supported.

As indicated in Tables 3, 4 and 5, when regressed as stand-alone variables the remaining acquisition-specific variables, which include experience with successful acquisitions, experience with local market, and intended integration, were not significant either as stand-alone variables or as country-specific interaction variables. Therefore, there is no statistical support for either parts a or b of hypotheses 3, 4 and 5.

With regard to the control variables at Level II, five out of nine individual and company-specific attributes seem to have had a significant impact on the target company manager’s likelihood to resign: age, gender, industry, size and ownership type (see Tables 2, 3, 4, 5).

4.2 Supplementary Analyses

We conducted four supplementary analyses in order to check the robustness of our results. First, as mentioned above, we included two random duplicate test scenarios in addition to the 26 scenarios that were given to the respondents and were not used in the analysis. One of the concerns in policy-capturing experiments is within-respondent decision consistency (Kristof-Brown et al. 2002). Variable responses in duplicate questions were measured as follows: for each pair of repeated questions, Q 1 and Q 2, we calculated each individual’s value of Var(Q 1,i ,Q 2,i ), where, as usual, Var(X) represents the variance of X. We write the sum of these variances for the two pairs of duplicate questions as σD,i. The overall consistency ΦI was computed for each individual i using the method suggested by Hammond et al. (1975), as \(\Phi _{{\text{\rm I}}} = \sqrt {\frac{{\sigma_{T,i}^{2} - \sigma_{D,i}^{2} }}{{\sigma_{T,i}^{2} }}}\), where \(\sigma_{T,i}^{2}\) represents the individual’s ‘total variance’ (i.e., the variance of all the individual’s responses). Finally, as a measure of overall consistency, we found the mean value of the ΦI measurements, as \(\frac{1}{n}\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} {\Phi i}\). The average test–retest reliability score for all the surveys was 0.94, which is considered a high degree of consistency. This score is quasi similar to that reported by Shepherd et al. (2013) and Kristof-Brown et al. (2002) and is relatively high compared to Choi and Shepherd’s (2004) score of 0.82. A high consistency score indicates that the managers in this experiment used stable decision-making processes when answering the random duplicate test scenarios (Kristof-Brown et al. 2002).

Second, since our sample is comprised of three nationalities (American, French and German), we checked the robustness of the above results by controlling for potential respondent biases induced by cultural differences (proxied by nationality). To this end, we compared the likelihood to resign associated with each of the four geographical categories of acquirers for the three-nation subsamples of respondents. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests did not provide any significant differences in the likelihood to resign across the three respondent subsamples.

Third, since our sample was also comprised of three different levels of management (middle managers, executive managers and CEO/president), further ANOVA tests were conducted to control for any significant differences in the responses based on job level. There were no significant differences found between the different management levels.

Last, in addition to control variables tested and presented in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5, we controlled for variables related to whether the respondent’s company operated as a multinational as well as whether it had previous experience with acquisition activities. The coefficient for these additional control variables were not significant and we therefore dropped these variables from the model.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

In researching the influence of the LOF and country-of-origin bias on the post-acquisition resignation intentions of target company managers, we formulated research hypotheses building on previous research from the literature stream on the human side of acquisitions (e.g., Buono and Bowditch 1989; Chatterjee et al. 1992; Krug and Nigh 2001; Larsson and Lubatkin 2001; Schweiger and Very 2003) as well as more recent studies from the growing international business literature dealing specifically with the foreign entrant’s country of origin and local staff in the host country’s perceptions of it (e.g., Bangara et al. 2012; Luo and Tung 2007; Ramachandran and Pant 2010). This paper extends the conclusions of both of these literature streams by demonstrating (1) the adverse effects for an acquirer originating from an emerging economy (Madhok and Keyhani 2012) and (2) the key role of the acquirer’s country of origin in a manager’s decision to remain with or to voluntarily leave their acquired company.

A first finding of this paper is evidence in support of the widespread existence of the adverse effects of country-of-origin bias among Western managers, particularly applicable to emerging-economy multinationals (Madhok and Keyhani 2012). This finding is further supported by the fact that, in spite of significant differences in age, position and tenure with the current employer between the American, French and German respondents, there was no significant difference in the evaluation of the primary judgment criteria of the acquirer’s country of origin across the three nationalities. Even though emerging-economy origin was observed to have a negative effect in our sample on both Chinese and Indian acquirers, it seems that the effect on the post-acquisition resignation intentions of target company managers was significantly stronger for Chinese than for Indian acquirers. Our results show that the intensity of host country target company managers’ unfavourable perceptions of a foreign acquirer’s country of origin seems to be differentiated according to the nationality of the emerging-economy acquirer. More specifically, this finding indicates that the classification of ‘emerging-economy company’ is not a homogeneous notion. The differentiated reactions of Western managers reflect the importance of country of origin in relation to the notion of emerging-economy status. Not all emerging economies are perceived in the same way by Western managers and, according to their reactions, the liability of being a Chinese acquirer is significantly higher than that of being an Indian acquirer. This stronger liability for Chinese acquirers may be due to often highly charged media coverage of acquisitions conducted by Chinese companies in the EU and the US. These acquisitions are also subject to greater scrutiny by acquisition experts and researchers who disseminate observations and statistics on post-acquisition integration difficulties encountered by Chinese acquirers, which may thus reinforce negative perceptions among Western managers. For instance, Spigarelli et al. (2013) report that as many as 70% of the acquisitions made by Chinese-owned companies prior to 2009 were considered failures. This differentiated impact between Chinese and Indian acquirers is not observed in local and other Western, developed-economy acquirers. Conversely, our detailed comparison shows significantly consistent correlations between a respondent’s likelihood to stay when the acquirer is a local or developed-economy acquirer. In summary, this first finding lends additional support to previous research showing that target company employees typically prefer to be acquired by companies that are more culturally ‘close’ than culturally ‘distant’ (Cartwright and Price 2003; Schweiger and Very 2003).

The primary focus of this study was to assess the impact of the LOF–country-of-origin relationship on key managers’ intention to remain with their company or to resign. Given that the LOF and country-of-origin bias are almost by definition already established drawbacks and hurdles, the first set of our hypotheses (1a, 1b, 1c and 1d) are more confirmatory than revelatory. The fact that the Western managers surveyed indicated a higher likelihood of leaving their company in the event of it being acquired by an emerging-economy company is not in itself surprising. The fact that these findings span equally across three nationalities and several levels of management do, however, make them relevant as research findings. The rather unexpected revelatory findings of this study are to be found instead in the non-significant interaction effects between the emerging-economy acquirer’s LOF and country-of-origin bias and four acquisition-related moderating variables (prior alliance, experience with successful acquisitions, experience with local market, and post-acquisition integration). All four of these moderating variables are considered to be established dimensions in the acquisition literature. Nevertheless, all four hypotheses associated with these interaction effects were not supported in our results. Further discussion of these unanticipated findings is therefore warranted.

The old saying ‘familiarity breeds contempt’ does not hold true in the context of cross-border acquisitions. Classified as an experiential factor, the existence of prior alliance between the acquirer and its target has been shown to have a positive effect on post-acquisition success (Arend 2004; Porrini 2004). The results of this study indicate that prior alliance does play a significant role in post-acquisition managerial resignation behaviour irrespective of the acquirer’s country of origin. However, when combined with both Chinese and Indian acquirers separately, this significant role disappears. Without a post-survey interview of each respondent, it is difficult to find a single explanation for these results. Chinese and Indian companies may simply be seen as more ‘foreign’ than a home country or a developed-economy multinational. In a similar study of LOF and country of origin comparing companies’ willingness to invest in a given country, Bell and colleagues (2012, p. 115) find that when it comes to cultural differences, “investor behavior is not entirely rational as originally believed”, and that “cultural factors circumscribe investor rationality”. It appears that the results of this study make a similar case whereby Western managers’ strong, preconceived country-of-origin biases (irrational as they may be) appear to override the significant and positive effects of any existing pre-acquisition alliance.

As with prior alliance, the hypothesised impact of the other three moderating variables was firmly supported in the literature. Therefore, the rejection of the hypothesised moderating impact of experience with successful acquisitions (Marks and Mirvis 2001), experience with the local market (Very et al. 1997) and the nature of post-acquisition integration of the target company (Stahl et al. 2003, 2012) is interesting in its own right. As with prior alliance, a possible explanation is that these results might have been skewed by the quasi exclusive focus of respondents on the country of origin of the acquirer. In the specific case of this sample, the nationality of the acquirer seems to be the dominating factor despite the design of the scenario which manipulated all five variables in the same way. It is also quite possible that even though acquisitions in Western markets by Chinese- and Indian-owned companies are still relatively new, many Western managers may have had dealings either directly or indirectly with one of these companies. Thus, it may be precisely because of their prior knowledge or experience with an emerging-economy company that these managers would choose to leave their company following such an acquisition. For instance, some Western managers’ prior knowledge may make them wary of the managerial techniques encountered, as may any inherent human, organisational and cultural challenges arising in previous acquisitions conducted by Chinese and Indian companies. Such challenges may make Western managers unsure about whether experience gained by Chinese and Indian acquirers may necessarily be automatically and successfully applied in subsequent cross-border acquisitions (Morosini et al. 1998).

This paper has several management implications, especially for emerging-economy companies aiming to expand into the EU and the US. Importantly, the findings suggest that emerging-economy companies need to be aware that they may be handicapped with a negative reputation mostly brought about by Western managers’ attribution-related or cognitive shortcut mechanisms and poor, stereotypical, perceptions. Given that acquisitions by emerging-economy companies are still a relatively new occurrence in most developed economies, the number of managers having direct employment experience with these companies is limited. This limited exposure means that most of the information available to these professionals may be second or third hand. Doubt and misinformation may therefore result in the premature loss of key human talent if acquisitions by emerging-economy companies are not handled with the proper attention to detail (Vecchi and Brennan 2014; Cartwright and Price 2003; Davy et al. 1988). Previous studies have shown that the loss of such talent in cross-border acquisitions has a negative impact on post-acquisition success (Kiessling et al. 2008). The consistencies of the findings of this study across a diverse sample of three different nationalities of managers particularly highlight the need for emerging-economy companies to pursue strategies for acquisitions in developed economies in order to be mitigate the loss of key target company managerial talent.

In order to reduce or eliminate the unwanted loss of key talent in their newly acquired companies, emerging-economy companies should plan on implementing aggressive socially oriented activities aimed at reducing cultural conflict and promoting the acculturation of target company personnel as quickly as possible following the announcement of an impending acquisition. A working example of just how successful this type of proactive policy can be is exemplified by a programme implemented by Lenovo’s managers following their acquisition of IBM’s PC Division under which groups of IBM PC employees were sent to Lenovo’s Chinese headquarters for training and senior Chinese executives were moved to a newly formed US headquarters in South Carolina to work alongside their American co-workers. In addition, once the acquisition was completed, Lenovo moved its headquarters to New York and made English the official corporate language (Liu 2007; Meschi and Vidal 2013). This proactive approach, targeted specifically at retaining key management and professional talent, has worked well for Lenovo. Despite the difficult challenges faced in its early years (Lemon 2008), the IBM PC acquisition has subsequently proved to be a success as evidenced by Lenovo having gained 16.7% of the world’s PC market surpassing its rival Hewlett Packard’s 16.3% (Gartner 2013). Lenovo is continuing to solidify its lead over Hewlett Packard and the other major PC manufacturers by capturing 19.4% of the world’s PC market (Gartner 2015).

There are several limitations to this paper which can be viewed as possible directions for future research. Most of these limitations relate to the use of the policy-capturing method. The experimental manipulation required for policy capturing, although a rich source of judgment-model data, does raise some concern. First, respondents are given the task of reading a relatively large number of vignettes in a short time span before being expected to make well-reasoned decisions on the various scenarios provided. In order to reduce the potential bias caused by respondents skimming the scenarios resulting in cognitive difficulties with survey completion, we presented the respondents with the same questions at the end of each scenario and presented the scenarios and their cues in paragraph form. The relatively high within-respondent decision consistency and the high test–retest reliability reported in the results section of this paper indicates that the participants paid attention to each scenario and that respondent fatigue was a limited issue.

Another drawback to policy capturing is a limited ability to make real-world generalisations based on the findings. In policy-capturing studies, the external validity of the findings is dependent on the quantity and nature of the scenario cues. Due to the limitations faced when constructing a scenario that is both realistic and not over complicated, it was not possible to include certain psychographics in the overall decision-making model. Influences such as undefined external market factors, personal demographics (i.e., married or single, number of dependent children, etc.) and other cultural factors were thus missing. It was also important for the survey participants to possess a minimum level of familiarity with the subject of the study. In order to address this potential bias, we wrote the scenarios on the basis of discussions with several managers with acquisition experience. Thus we chose the judgment criteria used according to their relative importance and how close they were with respect to real acquisition experience.

As we had to restrict the survey to a relatively small number of scenarios, other important acquisition-related dimensions deemed relevant in the associated literature, such as pre-acquisition performance of target company (e.g., any past need of rescue by another company), relatedness of acquisition parties, relative size of the acquiring company or length and quality of prior alliance between the acquirer and the target, were not examined in this paper.

A fourth limitation is a consequence of a manipulation included in the scenarios in which the respondent is offered a hypothetical job from the CEO of a competitor company. Building on Kiessling et al. (2012), we included this manipulation to remove any potential for making the respondent feel trapped in the target company job, and thus to allow greater respondent concentration on the possibilities presented in the scenarios. This manipulation, although intended to give the respondent more freedom in their decision on whether to stay or quit their company, may have been too simplistic and not totally consistent with real-life situations faced by working professionals. In addition, it turns out that the offer of new employment from a competitor may have influenced the responses of some participants. Depending on the competitive nature of a given industry, and possibly the positional level and nationality of the respondent, switching to a competitor may not be viewed as a positive option, as, for instance, indicated by the comments in our survey of a German CEO who stated that he was ‘highly unlikely’ to quit in every scenario as long as he did not ‘feel unfairly treated’.

This study, although multicultural in design, only included three nationalities. In addition, the choice of using only French, German or US companies as test models for our developed-economy multinationals was based solely on the restriction of time and the need for brevity. Future research should take a more comprehensive look at a much broader selection of developed economies, not only as a respondent base but also to enable further study into any potential differences between the nationality of the developed-economy multinational (i.e., Japanese, Swedish, etc.). In addition, although the impact of respondent industry was not found to be significant in this paper, future research should nevertheless include a more systematic analysis of the role of participant industry as well as the isolation and study of larger sample populations that have actually experienced acquisitions by foreign-owned companies in order to provide a more experienced sample base.

Finally, this paper has focused on emerging-economy companies from China and India. Again, further research should be done employing a more comprehensive assortment of newly globalising companies from other emerging economies. In addition, further analyses of between-country perceptions should be conducted as the results of our study indicate noteworthy differences in Western managers’ perceptions of Chinese- and Indian-owned companies. Future research should also be conducted targeting current and former managers of Western companies that have actually been acquired by Chinese- and Indian-owned multinationals in order to further extend our understanding of the factors affecting post-acquisition retention of key management talent.

Notes

Translation by authors. Original text is as follows: “Chinesische Investoren haben ein miserables Image. Oft gibt es das Vorurteil, dass sie nach einer Übernahme die Maschinen abbauen und nach China verschiffen. Doch ein solcher Fall ist nicht bekannt”.

References

Aiman-Smith, L., Scullen, S., & Barr, S. (2002). Conducting studies of decision making in organizational contexts: A tutorial for policy-capturing and other regression-based techniques. Organizational Research Methods, 5(4), 388–414.

Alkire, T. D. (2014). The attractiveness of emerging market MNCs as employers of European and American talent workers: A multicultural study. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 9(2), 333–370.

Arend, R. J. (2004). Conditions for asymmetric information solutions when alliances provide acquisition options and due diligence. Journal of Economics, 82(3), 281–312.

Bangara, A., Freeman, S., & Schroder, W. (2012). Legitimacy and accelerated internationalisation: An Indian perspective. Journal of World Business, 47(4), 623–634.