Abstract

Recent literature suggests that multinational companies pursue regional rather than global strategies. Therefore, this study investigates regional management structures, using French multinational companies (MNCs) in the Asia–Pacific region as an empirical context, to address two research questions: first, do MNCs split Asia into subregions and, if so, what are the resulting clusters of countries and clustering criteria? Second, what kind of regional management structures do MNCs establish in Asia, and what are their roles and functions? Factors, such as MNC size, the size of host markets, or the nature of their activities, might explain some differences. The authors conducted 77 face-to-face interviews with expatriated managers in charge of the subsidiaries or regional management structures of 47 French MNCs located in 11 countries in Asia, then crossed these data with secondary sources of information. Nearly half the MNCs subdivide the Asia–Pacific region into clusters of countries, where they locate regional management centres (regional headquarters, regional offices, distribution centres, local offices) with substantial functions and roles. The main drivers of a regional Asian strategy and organisation are the overall size of the MNC and its sales in Asia; the presence of manufacturing activities does not exert any influence. This research identifies ten clusters of countries in Asia, determined by the French MNCs in our sample, on the basis of four main criteria: market orientation/economic logic, geographical and institutional proximity, cultural differences, and the MNC’s own characteristics. Smaller MNCs do not slice Asia into clusters but rather centralise regional decisions and control procedures, implementing few regional management centres in Asia and giving them limited roles and functions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Even in the modern era of globalising economies, multinational companies (MNCs) appear to pursue regional rather than global strategies, focusing on one or two big regions instead of targeting the entire world simultaneously (Rugman and Verbeke 2008; Delios and Beamish 2005; Osegowitsch and Sammartino 2008; Ambos and Schlegelmilch 2010). These “semi-globalising” MNCs (Ghemawat 2005) and their regionalised strategies have significant implications for academic research and managerial practice, yet they remain poorly investigated (Piekkari et al. 2010; Alfoldi et al. 2012).

In response, we investigate the regional management structures of MNCs empirically, using French multinational companies in the Asia–Pacific region as an empirical context to find answers to two complementary research questions. First, do MNCs consider Asia as a single, unique region, or do they split Asia into subregions and clusters of countries? If the latter, what criteria do they use for this clustering, and do factors affect it, such as the nature of their activities, the industrial sector, or the size of the host markets in which the MNC operates? Second, what kind of regional management structures do MNCs establish in Asia? Specifically, what is their nature, and what are the roles and functions of such structures? We consider factors that might explain differences in regional management structures, such as the size of the MNC, the size of the host markets, or the nature of their activities.

In addressing these questions, we seek to fill several gaps in current research. Piekkari et al. (2010, p. 514) worry that though “regional structures are considered increasingly important in today’s regionally-structured world, this topic has attracted relatively limited scholarly attention” and Nell et al. (2011, p. 3) assert that “we still know little about regional management and how it complements other organizational mechanisms in managing and coordinating dispersed activities”. Studies instead have focused mainly on individual regional management centres (RMCs) (e.g., Daniels 1987; Lasserre 1996; Schütte 1997), lacked a clear focus, and tended to offer lists of advantages and disadvantages instead of detailed functions. Ambos and Schlegelmilch (2010) offer similar observations for the particular cases of US and Japanese firms in Europe. Moreover, as Enright (2005a) notes, literature on RMCs tends to be based on small samples, such as Schütte’s (1997) 29 interviews or Lehrer and Asakawa’s (1999) 19 cases. This trend has continued in recent studies, published in leading academic journals, that use single case studies (Paik and Sohn 2004; Piekkari et al. 2010) or just a few cases, such as Li et al.’s (2010) study of six Taiwanese MNCs. Our qualitative investigation instead relies on 77 face-to-face interviews, conducted with expatriated managers in charge of the subsidiaries or regional management structures of 47 small, medium, and large French MNCs, located in 11 countries in Asia.

In this large sample, we identify a group of nearly half of the MNCs that cluster the Asia–Pacific region into homogeneous subregions, then locate RMCs in these clusters, including both regional headquarters (RHQs) and regional offices with substantial, differentiated functions and roles. The main factors driving such regional Asian strategies and organisations are the global size of the MNC and its sales in Asia. We also identify ten different country clusters in this zone, determined by the French MNCs in our sample on the basis of four main criteria: market orientation/economic logic, geographical and institutional proximity, cultural differences, and the MNC’s own characteristics. Surprisingly, the number of factories and the importance of manufacturing localisation in Asia have little effect. In addition, small MNCs, even when they achieve most of their sales in Asia, still tend to centralise their regional decisions and control procedures at headquarters.

In the next section, we present our theoretical background, focusing on four interconnected topics: the regionalisation of MNCs, the regional organisation resulting from it, the nature of MNCs’ regional management structures, and the roles and functions of these structures. After we explain our qualitative interview methodology, we detail our main findings and offer answers to our two research questions. These findings lead into a set of six research propositions. We finish by highlighting how our research contributes to international management theory, before concluding with some general insights.

2 Theoretical Background

2.1 Regionalisation of MNCs

Globalising MNCs often concentrate their sales and production activities in one or two regions (Osegowitsch and Sammartino 2008; Rugman and Verbeke 2008). Rugman and Verbeke (2008) confirm that many of the world’s largest firms are not truly global but are regionally based, in terms of the breadth and depth of their market coverage. Ghemawat (2005) also acknowledges that it is often a mistake to design a worldwide strategy; better results can come from strong regional strategies, brought together as a global whole. According to Mahnke et al. (2012), academic research similarly emphasises the increasing importance of regions and regional management within MNCs.

Egelhoff (1988, p. 3) identifies an “area division structure” that MNCs can use to divide the world into geographic areas, each with its own headquarters, responsible for all products and businesses within that geographic area. Egelhoff (1982) also notes that such area division structures are more suitable for large, complex, overseas operations that require regional economies of scale, especially if the inter-regional differences are greater than intra-regional ones. Moreover, Egelhoff (1988) finds that headquarters organised into geographical area structures are more responsive than those organised into international divisions. Rugman and Verbeke (2008) concur, stating that “the importance of each triad region suggests the introduction of geographic components in the MNE structure”. With this claim, they refer to Ohmae’s (1985) triadic split of world markets—into North America, the European Union and Japan—which today seems out of date, particularly considering the massive development of emerging economies (e.g., Brazil, Russia, India, China).

Accordingly, Delios and Beamish (2005) find that Japanese multinationals organise their subsidiaries into seven regions: Asia, Oceania, Africa, Europe, Middle East, North America and South America. Paik and Sohn (2004) cite Toshiba’s four regional headquarters, in America, Europe, and the Asia–Pacific (which mirrors the classical triad), plus China, which Toshiba regards as a stand-alone region. This designation is not particularly surprising; China alone contains more inhabitants than the entire European region. In addition, various denominations, such as Asia–Pacific, Oceania, or Australasia, designate the Asian region overall and its subregions. In a valuable classification, Lasserre (1995) differentiates five types of countries in Asia: Platform (Singapore, Hong Kong), emerging (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos), growth (China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines), maturing (Taiwan, Korea) and one established country (Japan). Poon and Thompson (2003, p. 211) also underline “the highly disparate nature of markets in Asia. China alone [can be] seen as a country with several discrete regions”.

Thus, according to academic literature, MNCs are unlikely to consider Asia as a single, unique region but instead divide it into several clusters or subregions. Flores et al. (2013), on the basis of an in-depth literature review, identify criteria that MNCs likely take into account when designing supra-national regional groups: (1) geographic proximity; (2) cultural and institutional issues, including religion, political openness, and legal systems; and (3) economic development, trade, and investment flows. However, few empirical investigations have considered how these varied criteria, or others, might influence the design of MNC clusters in a particular area, such as Asia. Nor have any studies specified which Asian clusters might result from such intra-regional grouping. This identification represents a main aim of our research.

2.2 Regional Organisation

In an empirical survey of 130 regional headquarters, Yeung et al. (2001) propose three reasons MNCs set up regional headquarters in Asia. First, vast geographical distances require Western (though not Japanese or Taiwanese MNCs) to set up RHQs in Asia. Secondly, MNCs wish to better coordinate their globalized activities and exercise greater control over their Asian subsidiaries. Third, the MNCs want to be closer to local market conditions and make faster decisions to benefit from business opportunities. Thus, MNCs appear to establish RHQs in Asia as part of a wider regionalisation strategy.

For the 20-year period at the end of the twentieth century, Picard et al. (1998) determined that European RHQs gained power and autonomy. However, Piekkari et al. (2010), in their case study of Kone, show that the level of responsibilities that MNCs grant to their regional structures varies in different periods. In the early 1990s, Kone allocated substantial resources to regions; by the late 1990s, emphasising more global integration, it had stripped down the regional structures and downsized regional management. Seeking a balance between the regional and product dimensions in its organisational structures, Kone then reinforced its regional Asia–Pacific office in 2004.

The importance that headquarters assign to regional structures might be related to the country of origin of the MNC. Enright (2005b) does not find significant differences between the roles and functions that North American versus European MNCs assign to their RMCs in the Asia–Pacific region. Clearer differences emerge from a comparison of Western with Japanese MNCs though, in that the latter grant less prominent roles to their Asia–Pacific regional structures. Japanese RHQs have little decision-making autonomy, because the strategic business units at Japanese firms’ headquarters make the important decisions pertaining to regional strategies. The regional structures simply execute these strategic decisions, coordinate daily activities, and support the local subsidiaries (Lehrer and Asakawa 1999; Mori 2002; Paik and Sohn 2004). Geographical distances might explain such differences; cultural and institutional differences between the home countries of the MNCs (i.e., Japanese versus Western) may also explain the level of centralisation for strategic decisions.

Yeung et al. (2001) find that European MNCs place a high priority on establishing RHQs as part of their regionalisation strategy in the Asia–Pacific. They indicate that MNCs establish regional headquarters in emerging markets that are geographically too distant from their home country to be coordinated and managed efficiently by global headquarters. Piekkari et al. (2010, p. 526) confirm that the “persistence of cultural, geographic and language distances, the lack of social integration and strong economic growth (in the Asia–Pacific) strengthened the position of the regional organisation”, leading to “an expansive, more autonomous regional system in the turbulent, distant region of Asia–Pacific” (Piekkari et al. 2010, p. 527). Yeung et al. (2001) also note that US and European MNCs often set up two RHQs in Asia with different subregional scopes: those in Hong Kong tend to control and manage subsidiaries in North Asia (China, Taiwan, South Korea), whereas RHQs in Singapore take charge of subsidiaries in South-East Asia, including Australia and New Zealand. Piekkari et al. (2010) show that the Finnish company Kone has two RHQs in Asia, in Taiwan and Hong Kong.

Thus prior literature suggests that MNCs tend to establish RHQs in regions that are geographically and culturally distant from their main headquarters, in an effort to integrate their activities in such far-away zones. Because French headquarters are culturally and geographically far from the Asian countries of our empirical investigation, we address the conditions in which the MNCs in our sample establish regional management structures in Asia, following an approach similar to the one Ambos and Schlegelmilch (2010) adopted to study US and Japanese MNCs in Europe.

2.3 Nature of Regional Management Structures

Various regional management structures with differing management mandates (i.e., responsibilities and functions) emerge from prior literature, such as regional headquarters (Lehrer and Asakawa 1999; Mori 2002; Schütte 1997; Yeung et al. 2001; Ambos and Schlegelmilch 2010), regional operating headquarters (Yin and Walsh 2011), regional offices (Poon and Thompson 2003; Yeung et al. 2001), RMCs (Enright 2005a, b; Piekkari et al. 2010) or subregional headquarters (Li et al. 2010). So what does the term “regional headquarters” indicate precisely?

According to Mori (2002), an RHQ is a kind of headquarters, which differentiates it from liaison offices, regional offices, or holding companies; it constitutes the core of an organisation that carries out headquarter-like functions, including strategic decision making for the region. Schütte (1997) considers RHQs as organisational units, focused on the integration and coordination of an MNC’s regional activities, such that they constitute the link between the region and the headquarters. Yeung et al. (2001) define RHQs as business establishments that have control and management responsibilities for the operations of subsidiaries located in the same region, whereas regional offices lack any important decision power and execute only regional operating functions. According to Poon and Thompson (2003), RHQs take control over the operations of other subsidiaries located in other countries of a region, without having to refer too frequently to parent headquarters. In contrast, regional offices have less autonomy but are responsible for general business activities in the region. This view coincides with Lasserre’s (1996) assertion that RHQs, compared with regional offices, perform more integrative activities and have more autonomy. Li et al. (2010), studying six Taiwanese multinationals, identify four geographical decision-making levels: global headquarters, regional headquarters, subregional headquarters, and local subsidiaries. They designate North and South Asian “subregional headquarters” as falling just “under the Asia headquarters” (Li et al. 2010, p. 7).

According to Ambos and Schlegelmilch (2010), a key parameter for success in a host region is to work out strategy at the regional level, not at the global one. It is a means of dealing with both global and local pressures simultaneously. Their study suggests that regional headquarters are becoming increasingly important in managing global businesses (Ambos and Schlegelmilch 2010, pp. 59–60). They stress the potential advantages of RHQs: (1) the parenting advantage helps organise economic activity within the region—RHQs play a traditional parental role with local subsidiaries; (2) the knowledge advantage—“RHQs fulfill the mission of translating the global headquarters’ targets into successful strategies for local markets” (Ambos and Schlegelmilch 2010, p. 62); (3) the organizational advantage—RHQs may function as a “safety valve” as, on the one hand, RHQs handle pressure from global integration and regional adaptation to the corporate parent and, on the other hand, they deal with the dual pressure from regional integration and local adjustment to regional subsidiaries.

Piekkari et al. (2010) assert that only recently has managerial research, at the unit level of MNCs’ structures, produced insights into the roles and functions of RMCs. For example, Mori (2002) studies the European headquarters of Japanese MNCs and finds that, though RHQs sometimes participate in decision making for regional European strategies, the real decision power remains with the strategic business units (SBUs) at the global headquarters in Japan. Therefore, “RHQs are established to manage existing subsidiaries efficiently [whereas] the development of new business is not a primary function of RHQs,” leading to the conclusion that “RHQs are not SBUs” (Mori 2002, p. 14). Paik and Sohn (2004) confirm that Japanese RHQs are not powerful but are mainly responsible for supporting activities, operational integration, and local responsiveness in a specific region.

Further to an extensive literature review of authors frequently quoted in the research field (Kidd and Teramoto 1995; Lasserre 1996; Schütte 1997; Lehrer and Asakawa 1999), Mori (2002) classified these various concepts of regional organisation along two main lines: those with a decision-making role and those with a coordination–integration role. The resulting matrix identifies four types of regional structures: (1) RHQs, which have strong decision-making autonomy and a wide regional integration scope; (2) regional offices, with high decision-making autonomy but limited regional integration scope, often under the strong control of headquarters; (3) distribution and parts centres, which are widely regionally integrated but lack any strategic decision-making power; and (4) liaison or representative offices and holding companies, which exhibit both low regional integration and minimal strategic decision-making power. This typology is consistent with Enright’s (2005b, pp. 84–85) “office types”, distinguishing between RHQs, regional offices and local offices. However, Mori adds distribution centres to it, which were frequently mentioned during our interviews.

Thus, it appears that MNCs in Asia establish different types of regional management structures, to which they assign different goals, strategic or operational, and different levels of regional decision-making autonomy. We aim to study the nature of the regional management structures that the French MNCs of our sample set up in Asia, mainly with the help of Mori’s (2002) classification.

2.4 Roles and Functions of Regional Management Structures

Enright (2005a) uses a large sample of 696 observations to identify four types of RMCs. The “coordination and support centres” mainly support, monitor and coordinate regional operations and are responsible for reporting to the parent company; “full functional centres” adopt all these roles but also assume important central functions, such as regional strategy formulation, senior human resource management, marketing, sales and customer services. “Marketing and customer service centres” serve marketing and sales functions and have moderate importance in terms of strategy formulation, competition intelligence, coordination or the integration of regional operations. Finally, a “peripheral centre” performs relatively unimportant functions for the parent company.

Li et al. (2010) investigate the subregional headquarters of six Taiwanese MNCs in Asia. They rank decision-making levels at local, subregional, regional, or global categories for 22 upstream, downstream, and supporting activities. The parent headquarters in Taiwan centralise fundamental R&D and technology transfer; regional intermediate structures (e.g., RHQs, sub-RHQs) take on upstream and supporting functions, including regional supply chain management, production rationalisation, regional human resource management, budgeting, and portfolio investments. The subsidiary level takes mainly downstream responsibilities related to local sales, marketing, promotion, and advertising.

Freiling and Laudien (2012) argue that RHQs are administrative units, hierarchically located between the HQ and the local subsidiaries and governed by the firm’s HQ. Yet RHQs increasingly are becoming intermediate governance structures, with core coordination and integration functions and the ability to offer more flexibility than HQs. Paik and Sohn (2004) confirm that RHQs offer an effective organisational form for achieving concurrent goals of globalisation and local responsiveness. The simultaneous transfer of governance capabilities to RHQs, while subdividing the immense Asia Pacific region into clusters, might offer a solution to the global integration versus local responsiveness dilemma. Regional management structures also might reflect Ambos and Birkinshaw’s (2010) observation that headquarters managers pay only scarce attention to subordinated units, but such structures might have bottom-up influences on global corporate decisions.

Hoenen et al. (2013) recognise the varying entrepreneurial capabilities and responsibilities of RHQs, whose activities are not limited to the coordination and control of subsidiaries under their supervision. Rather, RHQs might be in charge of identifying local opportunities and initiating their exploitation or setting up new subsidiaries, for example. They also find that RHQs’ entrepreneurial capabilities grow with their increasing embeddedness in the regional environment, as measured by the density of their external linkages, and the degree of dissimilarity of markets on which they have responsibilities.

With this theoretical background, we derive several specific insights related to questions about clusters and regional management structures, summarised as follows:

-

The disparate nature of Asian countries might lead MNCs with regional Asian strategies to slice Asia into clusters of countries.

-

Because of geographical distance, and possibly cultural and institutional differences, Western and Japanese MNCs do not establish the same kinds of regional management structures with the same kinds of responsibilities in Asia.

-

Western MNCs in Asia set up different kinds of regional management structures, which might be hierarchically organised, with different kinds of responsibilities; some participate in strategic decision making, while others have more strictly functional and operational roles.

Additional empirical investigations are required to determine how to articulate the roles of different regional management structures of a given MNC. This is a question that our research tries to address, using a qualitative investigation of French MNCs in Asia.

3 Methodology: Data Collection and Analysis

We adopted a qualitative approach and conducted semi-structured, in-depth interviews with managers of subsidiaries in 11 Asian countries. Asia is the focus of our investigation for two main reasons. First, despite persistent global economic struggles, especially in Europe, Asia continues to register strong economic growth rates. Second, the forces of globalisation keep accelerating, prompting political, institutional, demographic, and technological changes in Asia that have reduced the barriers to and costs of doing business.

In order to obtain a sufficiently large sample of participating firms we contacted most of the large French MNCs in Asia. On the basis of interviews conducted between 2008 and 2010, we carefully selected 47 MNCs operating in multiple Asian countries. We sought to ensure variety with regard to pertinent international business performance variables, such as firm size and organisational characteristics (e.g., location, with and without production activities), so that we could obtain contrasting, comparative information to help us understand the phenomenon better (Miles and Huberman 1994). In this sense, our sample is purposive (Yin 2011), rather than being obtained randomly, on a convenience basis, or with snowballing. The purpose underlying our sampling approach is to ensure that our sample offers “the broadest range of information and perspectives on the subject of study” (Kuzel 1992, p. 37). Accordingly, we sought to include units that might offer contrary evidence or views, which enabled us to test for rival explanations as well (Kuzel 1992). In some cases, we interviewed managers in different countries working for the same MNC, so that the total number of interviews on which our research is based is 77 (cf. Table 1).

Our choice of French MNCs was practical as well; the author team consists of researchers in French institutions. Furthermore, Enright (2005b) confirms the similarity between European and North American MNCs for questions comparable to those that we investigate. Moreover, Jaussaud and Schaaper (2007) reveal similarities among MNCs from different European countries, so that investigating French MNCs might produce results with a reasonable degree of generalisability to MNCs from other Western nations.

To prepare for the interviews, we wrote a semi-structured interview guide in two languages: French and English (some managers in subsidiaries were of nationalities other than French). The interview guide started with two opening questions about the history of the MNC in the country and the entry modes for both the interviewed subsidiary and other subsidiaries of the MNC in the same country. Then, through a series of open-ended questions and several subquestions, we encouraged managers to describe the Asian countries in which their MNC engaged in activities, their clusters, the criteria for clustering, and the names of these clusters. We also invited them to describe the regional organisation of their MNC, the existence of logistic platforms in Asia, the existence of RMCs, their locations, the countries that the RMCs supervised, the role of regional headquarters in the organisational structure, reporting lines across the subsidiaries and headquarters, the role of regional headquarters in strategic decision making and regional human resource practices (e.g., expatriation, short-term assignments), and so on. We purposefully asked about a large variety of roles and functions, to gain insights into the actual situation. We also asked the respondents to explain, whenever relevant, the reasons for a specified degree of implementation (or non-implementation) of each regional function. We thus explored a broad set of potential justifications for any role and function. By pushing respondents to engage in deeper reasoning, we pursued an inductive posture, which was particularly useful for understanding and contextualising their specific practices (Silverman 2005).

We interviewed high-ranking managers in 47 French MNCs with subsidiaries in 11 Asian countries. We conducted 77 interviews across these 47 MNCs so as to achieve saturation not only with regard to the overall sample of MNCs in Asia, but also within every visited country. Saturation within a country was reached when additional interviews supplied no fresh significant information on the research questions (Symon and Cassel 1998). The saturation obtained within each country strongly enhanced the reliability of our results both at the country level and when it comes to the overall Asian sample. Table 1 contains an overview of the sample.

At the request of some of the interviewees, we do not provide the names of the MNCs here. This anonymity encouraged respondents to speak freely without asking for permission from their supervisors. For the same reason, we indicate their industries only in very broad terms. All the MNCs in our sample are major players in their respective industry.

The interviews all lasted between 1 and 2 h, and their contents were fully transcribed. We entered the transcripts of the 77 discourses into a thematic content analysis grid, with one column per subsidiary or regional headquarters, and one row per question or subquestion from the interview guide and per specific significant topic spontaneously addressed by the respondents.

Columns related to the same MNC (e.g., AA, from which we interviewed expatriates in five different countries) were grouped together, producing a content table with 47 columns, each representing a different French MNC. Then we systematically added various contextual variables drawn from the annual reports of these 47 MNCs. These additional variables enabled us to understand better and contextualise the organisational choices made by the interviewed MNCs—especially the industry or service sector, number and location of manufacturing units in Asia, countries with a commercial and/or production presence in Asia, global employment, employment in Asia, Asian employment as a percentage of global employment, turnover worldwide, turnover in Asia and Asian turnover as a percentage of the global turnover.

For the data analysis, we followed the methodological steps established by Silverman (2005) and Miles and Huberman (1994), including full transcription of the interviews, development of a coding frame that fit the theoretical background, a pilot test, revision of the codes, assessment of the reliability of the codes, real coding, preparation of a data file, and an exploratory analysis. On the basis of our research questions and expectations, we drafted an initial list of starting codes, including keywords, short sentences, and chunks of text (Symon and Cassel 2012; Yin 2011). Through a horizontal reading of each question or item in the thematic content analysis grid, we carefully reduced the interviews according to these codes, MNC by MNC, cell by cell. This first analysis revealed some supplemental regularity pertaining to our research questions, which prompted us to add a small series of emerging codes to the initial list (Miles and Huberman 1994). As a check of the reliability of our coding (Miles and Huberman 1994), each research team member performed individual coding; any differences were resolved through discussion. We then selected specific variables from the reduced content analysis and created a data file featuring the following key variables: industry, MNC size, turnover in the Asia–Pacific region, production subsidiaries in Asia, number of countries with subsidiaries in Asia, number of clusters and their labelling, number, nature and location of regional management organisations in Asia, functions and roles of regional management organisations. Details and data files can be requested from the authors.

We looked carefully for similarities and contrasts related to each dimension of our research questions. Finally, in a repeated reading of the interviews, we identified verbatim comments and brief examples to illustrate our derived reasoning. Table 2 summarises the successive steps of our qualitative approach.

4 Main Findings

We organise our findings into four complementary sections: clusters of countries in Asia, the number and location of RMCs that French MNCs establish in Asia, their nature, and their roles and functions.

4.1 Clusters of Countries in Asia

The MNCs in our sample slice the Asia–Pacific area into separate regional zones, to which they appoint specific management teams with dedicated functions. We call these subregional zone “clusters”—not to be confused with the concept of “industrial clusters”. Verbatim comments from our interviews confirm that MNCs assign dedicated management teams to clusters of countries, such as “one chief per cluster” (FB, SB, WB, BB), “country managers for country clusters” (EA, MA, LA) or “operational management teams per cluster” (GB, BA, GA).

Nearly half of the MNCs of our sample (22 of 47) slice Asia in subregional zones or clusters. Conversely, 25 MNCs consider the Asia–Pacific region a singular world region, to which they appoint one management team, which might be still located at the central headquarters or in a prominent Asian city. The MNCs that subdivide the Asia–Pacific region use two to five clusters. To explain this cluster strategy in Asia, we note first that the median turnover earned by MNCs that engage in clustering equals 12 billion euros worldwide and 1.6 billion in the Asia–Pacific region, whereas MNCs without clusters earn a median turnover of 1.8 billion worldwide and 0.3 billion in the Asia–Pacific. The Mann–Whitney non-parametric test (p < 0.01) as well as the test of differences in median values (p < 0.03) are significant. Furthermore, MNCs with clusters manage subsidiaries in ten Asian countries; those without them host subsidiaries in only seven countries. The Mann–Whitney’s non-parametric test (p < 0.01) as well as the test of differences in median values (p < 0.03) are again significant.

We therefore deduce that the global size of the MNCs and the extensiveness of their presence or amount of sales in the Asia–Pacific region help explain why MNCs segment Asia into subregions. In contrast, the importance of their production activities and the number of factories they manage in Asia do not appear to influence these cluster strategies.

On a more qualitative basis, our interlocutors confirmed that the main reason for MNCs to subdivide the Asia–Pacific was that huge sales increases and greater activities in the region during the past decade had made Asia too big in size and strategic importance to be managed as a singular whole. Complementary reasons included recognition of the important cultural and institutional differences among Asian countries, different entry modes into various Asian countries, and requirements related to MNCs’ business activities, such as specific veterinary norms (EA), medicine regulations (LA, UB), electricity equipment standards (QA), or installation of GPS relay antennas (AB). That is, the products themselves needed to be adapted for specific countries or groups of countries.

We also asked respondents from the 22 MNCs that adopted cluster strategies in Asia about the underlying logic. Each explained, in his or her own words, the criteria that led to the constitution of their clusters, as summarised in the “codes” column of Table 3. As suggested by Yin (2011), we gathered similar rationales into four categories: market orientation (i.e., looking for markets with close characteristics and/or high economic importance), geographical closeness (often in combination with institutional proximity), cultural differences between consumers of various Asian countries, and the particular characteristics of the interviewed MNCs. These categories also resonate with the clustering factors identified by two recent articles. Flores et al. (2013) identify, on the basis of an extensive literature review, geographic proximity, economic similarity (which includes multilateral trade agreements), and cultural and institutional factors as criteria for grouping countries regionally. Hoenen et al. (2013) instead measure intra-regional (dis)similarity in Europe according to five dimensions: economic environment, regulatory environment, customers’ attitudes and consumption patterns, competitive intensity, and market size. Both studies identify the clustering criteria using theoretical considerations, yet they align well with the factors we identify with interviews. Thus these approaches represent strong complements, as we detail in Table 3, and our method specifies an additional category (specific characteristics of the MNC) that extends beyond those identified in prior research.

The market orientation criteria for subdividing Asia into regional zones confirm the general opinion that Asia has become too big in size (sales logic, size of operations, turnover on key markets) or strategic importance (key countries, maturity of markets) to be managed as a unique whole, leading to a “regional organisation of customers” (AB). The geographical proximity between Asian countries can be combined with institutional proximity, such as regulation and norms for specific sectors (healthcare, pharmacy, electricity, GPS communication). Institutional differences are also mentioned for sectors where contracts need to be discussed with local or national administrations (waste, water cleaning, gas and oil exploration). The ASEAN free trade zone and future economic communities were mentioned as an important cluster criterion, because of the interpenetration of the markets of the ASEAN countries.

Cultural differences pertain mainly to mass consumption sectors, such as household appliances, beauty and personal care, or food and beverages, where high local responsiveness and product adaptation is necessary to meet consumers’ specific demands. Finally, specific MNC characteristics also lead to clustering, often on the basis of entry mode differences in various Asian countries. For example, some MNCs manage countries differently depending on whether they maintain joint ventures with local partners or manage wholly owned subsidiaries. Other MNCs separate countries containing subsidiaries from countries with licensed distributors or representative offices. Some MNCs distinguish their management practices for countries with production subsidiaries versus those with only commercial activities. Finally, some MNCs explain that clusters began forming with their first historical Asian entry.

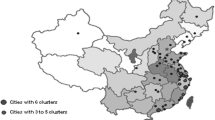

These four criteria lead 22 MNCs of our sample to subdivide the Asia–Pacific region into clusters, to which they appoint specific management teams. Table 4 regroups the ten main clusters, ranged roughly from north to south in the Asia–Pacific region; we also highlight the main criteria that gave rise to these clusters.

The first clustering logic is economic, based mostly on the importance of sales in subregions or specific markets. Thus, 18 MNCs manage clusters for mature Asian countries, especially Japan and Korea, from which they realise the majority of their Asian sales. For instance, the MNC TB, which is a well-known actor in the luxury industry, considers Japan a separate country cluster, because Japan is its biggest market worldwide. In addition, 12 MNCs regard China and, to a lesser extent, India (5 MNCs) as unique country clusters because these two emerging economies offer immense sales opportunities.

The second clustering logic is geographic, which often combines with institutional proximity, separating North Asia (5 MNCs) from South East Asia (14 MNCs). In addition, four MNCs consider the ASEAN free trade zone as a specific cluster. A third clustering logic is cultural proximity, which clearly is the case for clusters such as Greater China (4 MNCs) or Australia-New Zealand (5 MNCs).

Other clusters seem more surprising, such as MNC EA’s decision to combine India with Japan, Korea, China, and Taiwan and not with its ASEAN cluster, while the norms for registering veterinary products in India are closer to the legal requirements in North Asia. The automobile manufacturer QB includes Hong Kong and Taiwan within the ASEAN cluster, not within its country cluster China, because it considers China as a specific SBU with dedicated factories, which is also its very first worldwide market. The MNC EB includes India in the Middle East zone, not within the South Asia cluster, “because of specific links between India and the Middle East”. The MNC OB (luxury goods) manages a specific “Asian Airports” cluster. Finally, BA sees Thailand as a stand-alone cluster, distinct from both North Asia and South Asia, “because of the historical links between the Thai subsidiary and the top management”.

4.2 Number and Localisation of Regional Management Centres in Asia

Based on our literature review, we expected that French MNCs would set up varying types of RMCs in the Asia–Pacific region with different functions. We also expected to find a relationship between RMCs and clusters. We found that the number of RMCs that the MNCs in our sample set up in the Asia–Pacific region varies from 0 (CB, TA, VA, VB, WA, XA) to 4 (LA, LB). It clearly correlates with the number of clusters the MNC manages in Asia (r = 0.47; p < 0.01). The 22 MNCs with cluster strategies set up a total of 49 RMCs, for an average of 2.2 per MNC versus 25 RMCs for the 25 MNCs without cluster strategy, which makes an average of only 1 per MNC (t = 4.4, p < 0.01). The number of RMCs also correlates with the number of countries in Asia where the MNCs manage subsidiaries (r = 0.27, marginally significant as p < 0.06), which means that the more an MNC manages subsidiaries in a substantial number of Asian countries, the more it tends to set up intermediate regional management structures. Finally, the trend to establish RMCs seems linked with the global size of the firm: MNCs qualified as giant (Table 1) set up an average of 2.0 RMCs in Asia, versus 1.5 for big and medium-sized MNCs and only 0.9 for small MNCs.Footnote 1

Incidentally, regarding the localisation of regional management structures, our data reveal that Singapore is where French MNCs implement most of their RMCs (22 MNCs, or 29 % of the total RMCs), followed by Shanghai (16 MNCs, 21 % of RMCs) and Hong Kong (10 MNCs, 13 % of RMCs), whereas Beijing hosts only 6 RMCs. Overall, 60 % of the sample (28 of 47) maintain at least one RMC in China, and sometimes two (QA, AB, BA, NB). Furthermore, eight French MNCs locate RMCs in Tokyo, four do so in Bangkok, and two MNCs set up a RMC in Seoul and in Sydney; one MNC each locate a RMC in Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur, and Delhi.

The correspondence between clusters and the geographic location of RMCs is obvious. From the 18 MNCs managing a South Asia or ASEAN cluster, 14 set up RMCs in Singapore, with 2 others in Kuala Lumpur (QB) or Bangkok (BB). Thus, 85 % of the MNCs managing a South Asian cluster have an RMC within that region. From the 21 MNCs managing a China, Greater China, or North Asia cluster, 15 have set up one or more RMCs in China, equivalent to 75 % of cases. But only half of the MNCs managing a specific Japan and/or Korea cluster (18 cases) have established an RMC in Tokyo and/or Seoul.

4.3 Nature of RMCs

As highlighted by prior literature (Enright 2005a; Poon and Thompson 2003; Li et al. 2010), MNCs in Asia establish different types of regional management structures with different levels of regional decision-making autonomy. To clarify this point and understand the nature of regional management structures, in Table 5 we reproduce the terminology our respondents used when they talked spontaneously about their regional management structures in Asia. In the third column, we attempt to match their expressions with Mori’s (2002) and Enright’s (2005b) typologies.

Table 5 reveals the great diversity in terminology, which may indicate that the nature of the regional management structures is disparate, or it might reflect specific corporate vocabularies adopted by each firm. In the following section, we study the roles and functions that MNCs assign to their RMCs more closely, to determine whether they are regional headquarters or regional offices.

4.4 Roles and Functions of RMCs

After our respondents described their RMCs in Asia, we asked them an open-ended question, without any pre-coding, requesting that they describe the roles and functions of these regional management structures. Moving on from Enright’s (2005b) “office types”, we provide a list of distinctive functions of regional headquarters (Table 6) and regional officesFootnote 2 (Table 7).

Table 6 refers to 15 MNCs (AA, AB, EA, FB, HB, JA, LA, LB, NA, OA, PB, QA, QB, RA, UB) that have set up RMCs with high decision-making autonomy in strategic fields, such as investment choices, financing, business development, management of subsidiaries, executive HRM, and intra-Asian short-term assignments. These roles and functions are rather strategic in nature. Academic literature suggests that a regional management structure is a regional headquarters if it performs headquarter-like functions, including strategic decision making or control over subsidiaries, and when it does not have to refer frequently to central headquarters; therefore, we qualify these RMCs as RHQs. These roles and functions mirror the distinctive functions of RHQs cited by Enright (2005b), namely, business development, finance, investment, and senior human resource management. Eight respondents from the 15 MNCs spontaneously qualified their regional management structure with the term “regional headquarter” (AB, FB, HB, LA, LB, NA, QA, UB). Six others inaccurately noted a regional office (AA, EA, JA, OA, PB, RA), whereas the interviewee from MNC QB mentioned the company’s “Business Unit Asia”.

Prior research suggests that a RMC is a less autonomous regional office if it falls under strong control of the headquarters or RHQ and when it has responsibilities over a limited scope of activities. With these general definitions, we considered the roles and functions of the RMCs in our sample and thereby identified 27 MNCs that had set up one or more RMCs that could be qualified as regional offices (AA, AB, BB, DA, DB, EA, EB, GB, HA, IA, IB, JA, JB, KA, KB, LA, LB, MA, MB, NB, OA, OB, PA, PB, QA, QB, WB).

Table 7 reveals that regional offices take charge of operational roles and functions, such as reporting, consolidation of accounts, coordination of activities, information processing in a broad sense, local human resource management, and applied R&D. These roles and functions match the distinctive roles of regional offices, according to Enright (2005b): coordination, support, monitoring, and reporting.

The distinctive roles and functions of distribution centres are supply (DA, FA, IA, PB, QB, SA, TB), distribution (FA, GA, GB, LB), logistics (CA, JA, PB, QA, QB), and Asian sourcing (IA, JA). In total, 13 MNCs (CA, DA, FA, GA, GB, IA, JA, LB, PB, QA, QB, SA, TB) in our sample set up distribution centres in Asia, especially in cities with harbours, such as Singapore, Shanghai, and Hong Kong.

Among the 27 MNCs in Table 7 with regional offices, 9 also set up a RHQ (see Table 6: AA, EA, LA, LB, OA, PB, QA, QB and FB). Some MNCs thus maintain two regional management structure levels, featuring both RHQs and regional offices, whereas others have only one level, whether RHQs (6 MNCs) or regional offices (18 MNCs).

5 Discussion

Our qualitative research explores two complementary research questions. The first asks if MNCs split the Asia–Pacific region in subregions. If they do, what criteria do MNCs use to subdivide Asia into clusters, and can factors explain why certain MNCs adopt cluster strategies while others do not? The second question asks what kind of regional management structures MNCs establish in Asia. In other words, what is the nature of their RMCs, and what are their roles and functions?

With respect to the first research question, we find that nearly half of our sample (22/47 MNCs) considers Asia too big, in terms of turnover, number of countries with subsidiaries, or strategic importance, to address as a single market. In particular, the two giant emergent economies, China and India, and two mature markets, Japan and Korea, make an overall Asian strategy ineffective. Therefore, these MNCs subdivide Asia into two to five clusters of countries, to which the headquarters appoint dedicated management teams. The other half of our sample (25/47 MNCs) still considers Asia a unique whole. Compared with the first group, these MNCs tend to be smaller, earn fewer sales, and manage fewer countries with subsidiaries in Asia. Noting these results, and in line with Poon and Thompson (2003) and Yeung et al. (2001), we offer a first proposition:

Proposition 1: When strongly developed in the Asia–Pacific region, in terms of sales, number of countries, or in countries with strategic importance, MNCs subdivide the region into two or more clusters, to which they appoint dedicated management teams with distinctive responsibilities.

Building on this proposition, we investigated the criteria that MNCs use to cluster Asia into homogeneous subregions. We identified ten typical Asian clusters (see Table 4), which result from four main types of logic. The first is economic and based mainly on the amount of sales in subregions, together with the size and maturity of markets. The second logic reflects the geographical proximity of countries, which often is associated with institutional proximity and produces typical clusters, such as North Asia, South-East Asia, ASEAN, and Australia–New Zealand. The third cluster logic uses cultural differences between countries, which are especially important for MNCs with activities on mass consumption markets. Finally, the last logic is linked to the specific characteristics of MNCs, including entry modes (joint ventures, wholly owned subsidiaries, distribution licenses), the presence of production factories, and historical ties with specific countries. As a matter of fact our results are closely akin to the implementation logic highlighted by Ambos and Schlegelmilch (2010, pp. 69–70) concerning MNCs operating in Europe. Ambos and Schlegelmilch (2010) actually emphasize five grouping criteria used by MNCs to define the boundaries of regions and sub-regions: geographic proximity, market similarities, managerial, political and cost efficiency.

These findings lead us to derive a second proposition, which is in line with Lasserre (1995), Hoenen et al. (2013), and Flores et al. (2013):

Proposition 2: The constitution of clusters of countries in Asia is based on (1) economic criteria, (2) geographic closeness, (3) institutional and cultural proximity, and (4) the specific characteristics of the MNC.

With our second research question, we explored the regional management structures that MNCs establish in Asia. The French MNCs in our sample establish between zero and four RMCs in the Asia–Pacific region. Most MNCs (39/47) establish at least one RMC with more or less important functions that provides a basis for regional proximity. The number of RMCs relates closely to the number of clusters of countries that MNCs have constituted in the Asia–Pacific region. Clearly, MNCs with cluster strategies set up more RMCs in Asia than do MNCs without cluster strategies. The number of RMCs that MNCs establish also depends on the number of countries in which they have activities and, to a lesser extent, on its worldwide size. This result confirms Enright’s (2005a) conclusion that an MNC’s global size has less influence on the number of RMCs that it runs in the Asia–Pacific than does the geographical extent of its operations. We thus propose:

Proposition 3: When MNCs increase their turnover, the number of countries with subsidiaries, or the number of clusters in the Asia–Pacific region, they establish one or more regional management centres in the area.

Propositions 1, 2 and 3 clearly draw upon theories that were developed for explaining the worldwide regionalisation for large companies (Ohmae 1985; Delios and Beamish 2005; Paik and Sohn 2004). For instance, Delios and Beamish (2005) identify firm sales, the number of subsidiaries, and the number of countries with FDI as variables that determine the number of world regions in which MNCs internationalise. According to propositions 1, 2 and 3, the same clustering logic which prevails worldwide is increasingly applicable to smaller groups of countries within the world regions, like Asia, our studied case.

When we asked our respondents to describe the nature of their regional management structures in Asia freely, they used a great variety of expressions. By determining the functions and roles of the RMCs through these open-ended questions, we can align the variety of RMCs we identified with Mori’s (2002) and Enright’s (2005b) classifications. These results are also in line with Ambos and Schlegelmilch’ (2010) subregions approach in the European case.

Nearly one-third (15/47) of the MNCs of our sample created RMCs with strategic functions and roles, such as financing, investment decisions, strategic planning, business development, senior human resource management and intra-Asian short term assignments. Because they benefit from great decision-making autonomy, we can qualify them as regional headquarters. Nearly two-thirds of our sample (27/47 MNCs) set up RMCs in Asia with only operational roles and functions, including account consolidation, regional reporting, activity coordination, local human resource management, training, or applied R&D. Under the supervision of the HQs, or sometimes RHQs, these RMCs have less decision autonomy, so we consider them regional offices. These roles and functions match those identified by Enright (2005b) for, respectively, RHQs (business development, trade finance, capital investment finance, audit, planning) and regional offices (coordination of operations within the region, support, monitoring, regional reporting). Finally, we identified 13 MNCs with supply chain management centres in Asia. For seven of them, they constituted the only RMC the firm had in Asia.

These RHQs and regional offices clearly reflect each MNC’s cluster strategies. When MNCs manage two or more clusters, they set up RHQs, regional offices, or both. If MNCs manage Asia as a unique whole, they instead create more often a singular supply chain management centre or even smaller structures, such as liaison offices. However, we could not identify any variables to explain the choice between more autonomous RHQs and more operational regional offices. This discussion leads to three propositions:

Proposition 4: MNCs with cluster strategies in Asia often set up an RHQ with strategic roles and functions that benefit from great decision-making autonomy.

Proposition 5: MNCs with cluster strategies in Asia often set up one or more regional offices with operational roles and functions, under the supervision of headquarters or RHQs.

Proposition 6: MNCs without cluster strategies in Asia set up regional management centres with few roles or functions and little decision-making autonomy, such as distribution centres, liaison or representative offices.

6 Contributions to Theory

The integration/responsiveness framework (Prahalad and Doz 1987) offers a potentially appropriate theoretical lens for interpreting our empirical findings. Freiling and Laudien (2012) confirm that MNCs face the dilemma of exploiting both global and local business opportunities. They suggest a capability-based perspective to address the specific coordination roles of regional headquarters. Hoenen et al. (2013) consider the entrepreneurial capabilities of RHQs, derived from both their embeddedness in the regional environment and market dissimilarities in the region. Paik and Sohn (2004) assert that regional headquarters provide an organisational form for achieving the concurrent goals of globalisation and local responsiveness. According to De la Torre et al. (2011), among North American and European MNCs in Latin America, greater regional integration pressures combined with global efficiency demands lead simultaneously to increasingly centralised decision making and more regional coordination of activities. Li et al. (2010) explore organisational adjustments in Asia when MNCs switch to more regional strategies and also find evidence of subregional headquarters that manage subsidiaries within this subregion, under the supervision of regional headquarters. The emergence of such subregional headquarters appears to be a response to the need for more balance between global integration and local responsiveness.

In line with such research findings, our contribution sheds light on how clusters and regional management structures help overcome the distance challenge, in terms of geographic, cultural, and institutional distance, and thus better exploit local business opportunities from a global perspective. We find that when the Asia–Pacific region becomes too large, in terms of sales, number of countries to manage, or strategic importance, MNCs split it into two or more subregions, or what we call clusters. We also confirm the criteria that MNCs use to cluster Asia in homogeneous groups of countries, such that we offer real-world evidence in support of the theoretical predictions offered by Flores et al. (2013) and Hoenen et al. (2013). Moreover, our qualitative methodology enabled us to identify a complementary cluster criterion, the specific characteristics of an MNC, which is especially influential with regard to entry mode differences in various countries. The ten main clusters of countries in Asia that we identify (Table 4) should be useful for ongoing research into clustering questions.

In addition, within the various clusters, MNCs set up one or more RMCs with strategic (RHQs) or operational (regional offices) roles and functions. Like Li et al. (2010) we find that regional offices might fall under the supervision of regional headquarters, though not always. As De la Torre et al. (2011) note, it is a complex issue.

Our research provides useful insights for articulating the different kinds of regional structures that MNCs set up in Asia, as well as their specific functions (Tables 6, 7). Thus we offer an explanation for why regional structures exhibited varying levels of embeddedness in their environment. For example, because RHQs engage in both strategic and operational functions, they likely have stronger external linkages with their regional environment than regional offices, which in turn contributes to their entrepreneurial capabilities (Hoenen et al. 2013). Finally, we demonstrate that the relations between local subsidiaries and regional headquarters or offices are becoming more formalised (De la Torre et al. 2011). In parallel, MNCs without clusters in the Asia–Pacific region are reinforcing centralised decision making at global headquarters, while implementing few, if any, RMCs in Asia, and then granting them only minor roles and functions, mostly in the field of logistics and marketing.

7 Conclusion

With a large sample of French MNCs, we add evidence that regional management structures can be designed as intermediate organisational structures to maintain control over production and sales operations in Asia while also increasing proximity to local realities and thereby responding better to local opportunities and constraints. The design of MNCs’ regional organisation depends mainly on the size of the MNC and its sales in Asia, but localisation of manufacturing activities does not influence this design. Clustering decisions reflect four main criteria: (1) market orientation, (2) geographical closeness, (3) the cultural differences across various Asian countries, and (4) the characteristics of the MNCs. Regional structures vary in nature, from mere operational centres and regional offices to RHQs with both strategic and operational functions; we identify these variations precisely. Thus the results represent an important complementary contribution to existing findings while also filling a persistent research gap.

The economic crisis and stagnation of sales on many European markets has increased the need for Western MNCs to take more advantage of growing Asian markets. We recommend that to do so, MNCs should reinforce their regional structures. The manager of LB, who has extensive experience in Asia, warned though that MNCs “must find a balance between localisation and globalisation and not switch too much to one side or to the other”.

This research also suffers some shortcomings that might be overcome through further work. Our qualitative approach generates deep insights into why multinational firms divide Asia in clusters and implement RMCs, but even with the relatively large number of cases we consider, generalising our conclusions demands caution. Most of our findings are in line with previous research; however, they may not apply strictly to MNCs from countries other than France. Further research could investigate the cases of US or German MNCs in Asia for example. Moreover, a quantitative approach eventually may help test our propositions and shed more light on the questions we investigate.

The rise of corporate social responsibility is one of the striking developments of the modern globalised economy. Calls for MNCs to demonstrate greater responsibility, transparency, and accountability are leading to the establishment of new governance structures (rules, norms, codes of conduct, standards) that constrain and shape MNCs’ behaviour (Levy and Newell 2006; Kolk and Van Tulder 2005). On this point, RMCs contribute to the question. Some of the roles and functions we have highlighted, combined with additional material gathered in our interviews, suggest that the proximity of RMCs to operational units helps them control the implementation of the MNC’s global policy, particularly regarding working conditions in local factories and corruption.

Notes

However, the non-parametric k-sample test from Kruskal–Wallis was not significant (p < 0.17).

To be clear, RHQs perform strategic planning for the Asia–Pacific region, unlike both regional offices and distribution centres. Regional offices typically perform reporting and consolidation of regional subsidiary accounts, which distribution centres do not. However, RHQs might engage in regional reporting, in addition to strategic planning. Thus, we list the functions that RHQs, but not lower hierarchical levels, perform. In the same way, we list the functions of regional offices, which RHQs might perform but that lower hierarchical levels do not. Thus, we can refer to distinctive functions.

References

Alfoldi, E., Clegg, J., & McGaughey, S. (2012). Coordination at the edge of the empire: the delegation of headquarters functions through regional management mandates. Journal of International Management, 18(3), 276–292.

Ambos, B., & Birkinshaw, J. (2010). Headquarters’ attention and its effect on subsidiary performance. Management International Review, 50(4), 449–469.

Ambos, B., & Schlegelmilch, B. B. (2010). The new role of regional management. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Daniels, J. D. (1987). Bridging national and global marketing strategies through regional operations. International Marketing Review, 4(3), 29–45.

De la Torre, J., Esperança, J. P., & Martínez, J. I. (2011). Organizational responses to regional integration among MNEs in Latin America. Management International Review, 51(2), 241–267.

Delios, A., & Beamish, P. W. (2005). Regional and global strategies of Japanese firms. Management International Review, 45(1), 19–36.

Egelhoff, W. G. (1982). Strategy and structure in multinational corporations: an information processing approach. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27(3), 435–458.

Egelhoff, W. G. (1988). Strategy and structure in multinational corporations: a revision of the Stopford and Wells model. Strategic Management Journal, 9(1), 1–14.

Enright, M. J. (2005a). Regional management centers in the Asia-Pacific. Management International Review, 45(1), 69–82.

Enright, M. J. (2005b). The role of regional management centers. Management International Review, 45(1), 83–102.

Flores, R., Aguilera, R., Mahdian, A., & Vaaler, P. (2013). How well do supranational regional grouping schemes fit international business research models? Journal of International Business Studies, 44(5), 451–474.

Freiling, J., & Laudien, S. (2012). Regional headquarters capabilities as key facilitator of the coordination of transnational business activities. ZenTra Working Paper in Transnational Studies, No. 2/2012.

Ghemawat, P. (2005). Regional strategies for global leadership. Harvard Business Review, 83(12), 98–108.

Hoenen, A., Nell, P., & Ambos, B. (2013). MNE entrepreneurial capabilities at intermediate levels: the roles of external embeddedness and heterogeneous environments. Long Range Planning. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2013.08.009. Accessed 1 Oct 2013.

Jaussaud, J., & Schaaper, J. (2007). European and Japanese multinational companies in China: organization and control of subsidiaries. Asian Business & Management, 6(3), 223–245.

Kidd, J. B., & Teramoto, Y. (1995). The learning organization: the case of the Japanese RHQs in Europe. Management International Review, 35(2), 39–56.

Kolk, A., & Van Tulder, R. J. M. (2005). Setting new global rules? TNCs and codes of conduct. Transnational Corporations, 14(3), 1–27.

Kuzel, A. (1992). Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In B. F. Crabtree & W. L. Miller (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (pp. 31–44). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Lasserre, P. (1995). Corporate strategies for the Asia-Pacific region. Long Range Planning, 28(1), 13–29.

Lasserre, P. (1996). RHQ: the spearhead for Asia Pacific markets. Long Range Planning, 29(1), 30–37.

Lehrer, M., & Asakawa, K. (1999). Unbundling European operations: regional management and corporate flexibility in American and Japanese MNCs. Journal of World Business, 34(3), 267–286.

Levy, D. L., & Newell, P. (2006). Multinationals in global governance. In S. Vachani (Ed.), Transformations in global governance; implications for multinationals and other stakeholders (pp. 146–167). Cheltenham: Edward Elgard Publishing.

Li, G. H., Yu, C. M., & Seetoo, D. H. (2010). Toward a theory of regional organisation: the emerging role of subregional headquarters and the impact on subsidiaries. Management International Review, 50(1), 5–33.

Mahnke, V., Ambos, B., Nell, P. C., & Hobdari, B. (2012). How do regional headquarters influence corporate decisions in networked MNCs? Journal of International Management, 18(3), 293–301.

Miles, M., & Huberman, A. (1994). Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Mori, T. (2002). The role and function of European regional headquarters in Japanese MNCs. Working paper No. 141, Hirosaki University.

Nell, P. C., Ambos, B., & Schlegelmilch, B. B. (2011). The benefits of hierarchy: exploring the effects of regional headquarters in multinational corporations. In C. G. Rasmussen (Ed.), Advances in international management (Vol. 24, pp. 85–106). Bingley: Emerald Publishing Ltd.

Ohmae, K. (1985). Triad power, the coming shape of global competition. New York: Free Press.

Osegowitsch, T., & Sammartino, A. (2008). Reassessing (home-) regionalisation. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(2), 184–196.

Paik, Y., & Sohn, J. H. D. (2004). Striking a balance between global integration and local responsiveness: the case of Toshiba corporation in redefining RHQ’s role. Organisational Analysis, 12(4), 347–359.

Picard, J., Boddenwyn, J. J., & Grosse, R. (1998). Centralisation and autonomy in international-marketing decision making: a longitudinal study. Journal of Global Marketing, 12(2), 5–24.

Piekkari, R., Nell, P. C., & Ghauri, P. N. (2010). Regional management as a system: a longitudinal case study. Management International Review, 50(4), 513–532.

Poon, J. P. H., & Thompson, E. R. (2003). Developmental and quiescent subsidiaries in the Asia-Pacific: evidence from Hong Kong, Singapore, Shanghai and Sydney. Economic Geography, 79(2), 195–214.

Prahalad, C. K., & Doz, Y. L. (1987). The multinational missions: balancing local demands and global vision. New York: Free Press.

Rugman, A. M., & Verbeke, A. (2008). A new perspective on the regional and global strategies of multinational services firms. Management International Review, 48(4), 397–411.

Schütte, H. (1997). Strategy and organisation: challenges for European MNCs in Asia. European Management Journal, 15(4), 436–445.

Silverman, D. (2005). Doing qualitative research; a practical handbook. London: Sage.

Symon, G., & Cassel, C. (1998). Qualitative methods and analysis in organisational research. Newbury Park: Sage.

Symon, G., & Cassel, C. (2012). Qualitative organizational research: core methods and current challenges. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Yeung, H. W., Poon, J., & Perry, M. (2001). Towards a regional strategy: the role of regional headquarters of foreign firms in Singapore. Urban Studies, 38(1), 157–183.

Yin, R. (2011). Qualitative research from start to finish. New York: Guilford Press.

Yin, M. S., & Walsh, J. (2011). Analyzing the factors contributing to the establishment of Thailand as a hub for regional operating headquarters. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 2(6), 275–287.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amann, B., Jaussaud, J. & Schaaper, J. Clusters and Regional Management Structures by Western MNCs in Asia: Overcoming the Distance Challenge. Manag Int Rev 54, 879–906 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-014-0222-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-014-0222-7