Abstract

-

The literature on multinationality and firm performance has generally disregarded the role of geography. However, the location of FDI assumes particular importance in terms of the link between multinationality at the firm level. The purpose of this paper is to consider the multinationality-performance relationship within the context of greater emphasis on the importance of location, but also emphasising the importance of the location decision.

-

This paper draws on firm-level data covering over 16,000 multinationals from 46 countries over the period of 1997–2007 and allows for different effects upon the performance of the multinational firm depending on the level of development of the host economy.

-

In our results, we find a clear positive relation between multinationality and firm performance. However, investment in developing countries is associated with larger effects on performance than in the case of investment in developed countries. We also find that the return to investing in developing countries is U-shaped.

-

This indicates that multinationals are likely to face losses in the early stage of their investment in developing countries before the positive returns are realized. Overall, our results suggest that the net gains for multinationals from greater geographical diversification have not yet been fully explored. Geographical diversification into developing countries may be an important source of competitive advantages that deserves more serious consideration from business leaders and academics alike.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This paper seeks to link the importance of location to the well understood debate concerning the multinationality-performance (MP) relationship. To date, critiques of the multinationality-performance (MP) literature have largely focussed on the measures of internationalisation that are employed, such as the scope of geographic dispersion, and measures of assets dispersion across countries on the one hand, and the measures of performance on the other. Equally, attempts to link this issue to the theory of international business have tended to focus on whether the link between these two measures is linear, (see recent surveys by Li (2007) and Contractor (2007) and Meta-analysis by Yang and Driffield (2012)).

However, the literature in general ignores the importance of location. One of the most enduring contributions to international business has been the plea of Dunning (1998) for scholars to consider fully the importance of location. Location advantages are at the centre of IB theory, in that multinationality allows firms to exploit economies of scale and scope, while internalising their tangible and intangible assets and to relocate activities to reduce cost (Buckley and Casson 1976; Rugman 1986; Dunning 1988; Helpman et al. 2004). Indeed, this is at the heart of the MP debate, with well established empirical studies providing evidence of such a positive link between multinationality and performance, in particular when drawing on firm-level data (Tallman and Li 1996; Goerzen and Beamish 2003; Pangarkar 2008). However, while the existing literature has made an important contribution, one shortcoming is that it has generally disregarded the role of location choices, opting instead for an aggregate view of overseas investment.

One important aspect in this context is that these new FDI destinations in developing countries typically exhibit considerable heterogeneity, particularly in terms of indicators typically associated with the likely success of inward FDI. This includes infrastructure, political stability and transportation costs, as well as labour quality and trade flows. In this context, an important question for academics and practitioners alike is whether performance gains from FDI differ with respect to the location choice made by multinational firms.

In this paper, we focus specifically on the role of the host country’s level of economic development. In particular, whether the returns to investment in developing countries are different from the returns in developed countries. We employ a data set covering some 16,000 multinational firms with headquarters in 46 different countries, and investments in 202 host countries.

As in previous related research, we find a clear positive relation between multinationality and firm performance (Tallman and Li 1996; Goerzen and Beamish 2003; Pangarkar 2008). However, investment in developing countries is associated with larger improvements in performance than investment in developed countries. In addition, the return to investing in developing countries is U-shaped. We interpret these results as indicating that while the investment in developing countries is riskier (with potentially a higher spread of returns) than the investment in developed countries (Berry 2006; Qian et al. 2008), the potential of globalisation in terms of net gains from greater geographical diversification most likely has not yet been fully explored by multinational firms.

The remainder of our paper is organized as follows. We continue with a brief review of the relevant literature and build our hypotheses, after which Section 3 discusses our approach, data and empirical methodology. Section 4 then presents the results and robustness checks. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes.

Literature and Hypotheses

The theoretical paradigm on which this paper is based is the one presented by Dunning (1979, 1998). As is well understood, this outlines not only the motivation for firms to engage in FDI, but presents the benefits of becoming a multinational. This focusses on the ability of the firm to arbitrage in capital markets, combine different firm specific and location specific advantages, instigate international division of labour, and exploit market failures in terms of internal scale economies and market structures. Multinational firms have opportunities to achieve greater returns from international exploitation of intangible assets. Allied to this are the benefits of internalisation, including economies of scale and scope, and the ability to relocate activities to reduce costs. These features of multinationality lower the costs and increase productivity, leading to increased financial performance (Buckley and Casson 1976; Rugman 1986; Dunning 1988; Tallman and Li 1996; Helpman et al. 2004).

Within this, location plays a key role, as re-stated by Dunning (1998). More recently however, analysis has turned to a wider range of location factors, both in explaining location of FDI, and also the relationships between location and performance. Work that seeks to link multinationality to performance attempts to determine how widely such technology can be managed and exploited before returns start to decline (Mariotti and Piscitello 1995). However, it is important here to distinguish between tangible firm-specific assets, and more intangible assets, which by their nature are harder to exploit through the market mechanism. The importance of intangible assets in relating multinationality to performance is often ignored.

This extends the traditional OLI paradigm, and re-emphasises the role of location, but combined with the importance of non-material assets. Multinationality allows firms to transfer intangible assets more easily, such that the emphasis then turns to the creation of these assets, and the location of activities such as innovation. This then offers a general framework emphasizing transactions costs, and has recently been extended by Dunning and Lundan (2008), Dunning (2009), Buckley and Casson (2009, 2010), Hennart (2010). Cantwell et al. (2010) then extend this to consider the co-evolution of firms and locations, considering institutional development in its broadest form. This presents two general conclusions; firstly that growing complexity of organizational structures may lead to higher transaction costs, and therefore greater autonomy of subsidiaries, but secondly that firms most able to interact successfully with the host economic and institutional environment will be those that gain most from multinationality. This literature also however presumes that the boundaries of the firm are in some sense “correct”, in that the firm is able to identify the point at which the marginal benefit of international diversification is zero, and that in terms of seeking to examine the MP relationship, one has to control for the sample selection effect, of “better firms making better decisions” (Dastidar 2009).

The purpose of this paper is then to consider the multinatilonality-performance relationship within the context of greater emphasis on the importance of location, but also emphasising the importance of the location decision. Previous analyses suggest several reasons why increased multinationality should be linked to firm performance, see for example Kogut (1985), Benvignati (1987), Grant (1987), Tallman and Li (1996), Gomes and Ramaswamy (1999) and Contractor et al. (2003). Greater geographic dispersion facilitates the undertaking of domestic ventures that are high-risk but also highly profitable. A linear and positive correlation was evidenced in Kim et al. (1993), Grant (1987), Goerzen and Beamish (2003), Castellani and Zanfei (2007) and Pangarkar (2008). On a theoretical level, this is consistent with firms having opportunities to achieve greater returns from internalizing their intangible assets, leveraging their market power, achieving economies of scale, or drawing on less expensive inputs from foreign locations. On the other hand, other studies find a negative correlation between multinationality and performance (Michel and Shaked 1986; Collins 1990). These results are consistent with the view that multinational firms face liabilities from increased coordination and management costs and from cultural diversity.

However, there is considerable evidence that this may not be linear, and that the returns to internationalisation are initially negative. A large literature has tested empirically this multinationality-performance relationship. In particular, several studies have examined the MP link by drawing on firm-level data, which allows one to control for a number of potential biases present in more aggregated data. However, this empirical literature has not yet provided a clear picture. In part, this relates to methodological and data set differences across studies, as suggested by surveys (Li 2007) and meta-analysis (Wagner and Ruigrok 2004; Bausch and Krist 2007; Yang and Driffield 2012).

The U-shaped relationship suggests an initially negative MN-Performance relationship due to organizational costs and complexity associated with overseas expansion outweighing benefits, before the positive returns of foreign direct investment more than compensate the former costs (Qian 1997; Ruigrok and Wagner 2003). An inverted U-shaped relationship suggests that multinationality is initially associated with positive returns but, beyond an optimal desirable level, is again detrimental to performance. The possible reasons for this downturn in returns include the liabilities associated with overseas expansion and the difficulties of organizational coordination across different cultures and legal environments (Gomes and Ramaswamy 1999; Qian et al. 2008). A horizontal S-shaped (also known as the three-stage model) relationship suggests multinational firms experience a performance downturn at low degree of multinationality, followed by a increasing performance at moderate degree of multinationality, and eventually a second and final performance downturn at high level of multinationality (Contractor et al. 2003; Lu and Beamish 2004). The interpretation of this “curvilinear hypothesis” has been discussed in detail in Contractor (2007). However, the shapes of curvilinear MP relations are in part due to the sampling selection, for further discussion see (Li 2007; Yang and Driffield 2012). Yang and Driffield (2012) find in a meta-analysis that the MP relationship for non-US firms is usually U-shaped. In this paper, we investigate the shape of the curvilinear MP relationship for a wide set of countries.

Multinational firms face the liability of foreignness (LOFs) when establishing subsidiaries abroad. Foreign subsidiaries faced increased costs associated with the coordination and management of workers from different cultures (Michel and Shaked 1986; Collins 1990; Denis et al. 2002; Laudien and Freiling 2011), as well as the need to adapt ownership advantages to foreign environments. Externally, institutional differences between home and host countries lead to increased transaction cost and uncertainty (Calhoun 2002). They also have to overcome unfamiliarity with their brand, associated with newness as well as foreignness (Li 2007; Zaheer 1995; Zaheer and Mosakowski 1997), and issues surrounding the external business networks (Stinchcombe 1965; Lu and Beamish 2004). It is these, along side the complexity of managing foreign exchange fluctuations (Sundaram and Black 1992; Kostova and Zaheer 1999; Guisinger 2001) that have been used to justify negative to multinationality at the early stages, reported elsewhere in the literature (Zaheer 1995; Ghemawat 2001; Hymer 1976).

Institutional distance (cognitive, normative and regulatory) between the home and host country is the key driver behind LOF when multinationals go abroad (Eden and Miller 2004). In order to overcome liabilities of foreignness, it is crucial for multinationals to establish legitimacy in the host country (Denk et al. 2012), gaining the acceptance from local customers (Yildiz and Fey 2012).

Increasing embeddedness of both tangible and intangible assets within the host country, through local networking, resource commitment, and input localization increases the legitimacy of the assets, following the argument of Luo et al. (2002), such that over time these incremental commitments alleviate LOF (Moeller et al. 2013). In turn this increased embeddedness improves knowledge flows between the host economy and the firm, increasing the returns to multinationality.

In addition, multinationals gain international experience through its incremental commitment and learning effect through overseas market (Johanson and Vahlne 1977, 2009), and international experience mitigates the level of LOF (Mezias 2002), and overseas operations provide multinationals substantial benefits from leveraging knowledge from multinational enterprise’s subsidiaries that strengthen competitive advantage in all overseas markets (Sethi and Judge 2009), leading to positive returns to FDI at later stage of investment.

Hypothesis 1:

The relationship between multinationality and performance is U-shaped. The returns to internationalisation only occur once the initial costs of internationalisation have been incurred. As such, the relationship is initially negative, but increases after a given level of internationalisation.

The Interaction Between Location Advantages and Ownership Advantages

The motivation to engage in FDI is based around the interaction between ownership advantages and location advantages, and the importance of intangible assets as the key ownership advantage in this context (Hall 2001; Markusen 1995). Much of the MP literature also uses this interaction in order to explain the nonlinearities discussed above, but ignores the importance of geography in the specifications. A recent review paper by Beugelsdijk et al. (2010) explains that one of the major remaining weaknesses in the convergence of the economics, geography, strategy and international business literatures is that lack of focus on how the firm’s organizational characteristics relate to its geographical characteristics. In fact, the role of geography is rarely the main object of previous research (Beugelsdijk 2007).

Driffield and Love (2007) link the FDI decision to certain measurable characteristics that are essentially proxies for the level of development of an industry, and the extent to which a firm can leverage its ownership advantages in order to successfully engage in FDI. This is an important consideration within the MP debate. Multinationals have opportunities to internalise or transfer their resources among different geographic market through international exploitation of intangible assets with their controlled overseas affiliates (Buckley and Casson 1976; Hennart 1982; Rugman 1981). Developing countries have the greater distance to the technological frontier, and the latest technologies may not have sufficiently diffused, so the MNEs’ resources advantages derived from internal markets and/or the MNC network are more likely to be exploited well in developing countries due to market imperfections are more prevalent there (Pantzalis 2001). Multinationals are more likely to reduce cost of production and exploit their technological advancement when investing in developing countries where there are abundant inputs and low competition. Equally however, one must consider this in the light of the discussion on risk presented above, in that both political and economic risk associated with FDI to developing countries may generate a higher spread of returns. However, multinationals are capable of hedging risk through developing country operations. In finance literature, multinationals go abroad due to the imperfection in the product and factor markets, different taxation, and the imperfection of international financial markets, and they earn excess returns through international investment (Doukas and Travlos 1988; Mikhail and Shawky 1979). Although risks due to entry barriers in developing nations are high, once a firm has crossed that threshold, profitability could also be higher in developing countries because of a lower intensity of competition, the MNEs resource advantages doing well in developing markets, and since much of the R&D and fixed overheads of the MNE are already amortized, and multinationals are capable of hedging the risk from developing country operation across geographical space, and the existing multinational “networking” (Kogut 1983; Doukas and Travlos 1988) facilitates the flexibility to internalise resources across border, leading to a positive returns (Agmon and Lessard 1977; Errunza and Senbet 1981, 1984).

In contrast, high proportions of FDI between developed countries are based on strategies that may be considered more ‘defensive’, and in the terminology of Rugman and Oh (2010) may be considered regional rather than global investments. Market conditions, including demand and cost conditions, as well as levels of technology across the host and source country are similar. Equally, the potential of immediate short term gains from such investments are more limited, higher proportions of FDI between developed countries represent M&A activity for example, and the many studies in this area point to only marginal benefits of such FDI.

The attractiveness of markets in developed countries has been characterized in terms of their technological or knowledge advantage, and in terms of managerial capability that allows an extension of the value chain of foreign multinational enterprise into this market (host countries with market conditions similar to the home market is preferable) or allows technological acquiring (especially in merge and acquisition investment among developed countries. As such, multinational firms may self-select or choose the location of FDI, and the motivation of technology sourcing of mergers and acquisitions and FDI activities between western countries has hitherto been ignored in the MP literature. Driffield et al. (2010) for example highlight multinational enterprises as sources of international technological flows, and explain how the location choice of FDI activities and technology sourcing relate to subsequent performance. This kind of investment may lead to growth in size and the technology capacity of firms, while it may not lead to higher firm profitability (Doukas and Kan 2006; Driffield and Yang 2011).

However, one also has to consider the particular context of the differences between developed and developing countries. The existing literature emphasises the cost of internationalisation raised from cultural and institutional distance between home and host countries. Both Mani et al. (2007) and Spencer and Carolina (2011) emphasise the need to consider both the host market conditions, but also crucially the difference between host and home countries when evaluating FDI projects. Most commonly this is expressed in terms of either cultural distance, or institutional distance, see for example Henisz and Swaminathan (2008) or Habib and Zurawicki (2001). Analysis of cultural of psychic distance dates back to Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul (1975) and Johanson and Vahlne (1977, 1990). It has been applied to language, legal system and culture (Ghemawat 2001). Habib and Zurawicki (2002) make a direct link to the ability of the firm to manage unfamiliarity and its likelihood of success, while Davidson (1980) argues that unfamiliarity may lead to higher levels of risk aversion on the part of decision makers. Thus, firms with experience of certain conditions may be expected to gain earlier from investing in similar locations, building on Cuervo-Cazurra (2006).

Our analysis of the importance of distance, and therefore of the differences in the initial returns to investing in developing countries is then based on this argument, linked to the analysis of Bruton et al. (2010), who links institutional framework of the host country to the nature of the agency conflicts within the firm. While Bruton et al. (2010) focus on the links between governance and ownership, we extend this by considering the returns to the investment in this context. It is important here to further consider the difference in risk attached to investing in developing countries rather than developed countries. Much of the IB literature here focuses on political risk, that is the possibility of government intervention, in the most extreme case expropriation of the investment by the government or its agents (Busse and Hefeker 2007). However, as Frynas et al. (2006) suggest, there is the possibility of links between government and business providing a degree of firm’s mover advantage or entry barriers to certain firms, thus protecting their investment. However, such uncertainty may act to increase the spread of potential returns from such investments, rather than necessarily increasing the average return, as suggested by Tallman (1988). Further, Buch et al. (2009) also find that banks charge higher rates for risky investments, such that on average this may negate the gross returns when considering net profitability. This argument links to the issue of the liability of foreignness discussed above. While investing in a developing country may be perceived as risky, the technological capacity in the home country, along with institutional quality and product quality and reputation, means that the LOF may be easier overcome by a developed country firm in a developing country. This is similar to the argument made by Cantwell et al. (2010) concerning the co-evolution of foreign affiliates and host country institutions, which increases the legitimacy of the firm in the host country. As such, the returns to this type of investment may increase faster once LOF is overcome.

Along with globalization pace in recent years, economic and institutional facilities in developing countries are offering better environments where the core competence of multinationals could be efficiently utilized. Further, much of the recent FDI in developing countries is attracted by the traditional market seeking motives such as the case of China and India, the abundant low-cost production costs and natural resources (Dunning and Lundan 2008). The achievement of economies of scale and low marginal cost in developing country locations are expected to lead to higher profit relative to investment into developed countries location.

Hypothesis 2:

Multinational firms have a higher return to investing in developing countries than in developed countries, and the turning points in the nonlinear relationship occurs earlier.

Source Country Effects

Our final contribution concerns another issue seldom examined in the literature, which is the distinction between developing country and developed country firms, not in terms of the host, but the source country. Firms in developing countries have a greater distance to the technological frontier, relative to firms in developed countries (Martins and Yang 2009). While the resource-based theory would suggest that high technology from richer countries are well placed to coordinate international activities, but across a more limited number of available locations. Firms in medium technology industries however are more likely to experience the benefits of coordinating technology flows across countries, while at the same time having a wider range of potential locations.

There is a growing literature on FDI from emerging or developing economies, dating back to late seventies; the phenomenon of FDI by developing and emerging country MNEs was examined in a series of papers that emphasised the ability of such firms to use technologies that were well suited for the factor costs, input characteristics and demand conditions in the host countries (Wells 1983; Lall 1983; Lecraw 1983, 1984). This early literature argued that, for the developing country MNES (DMNEs), the incentive to invest overseas came largely from market protection by potential export destinations, and risk diversification by locating part of their assets outside their respective home countries. They typically entered the overseas markets as junior partners in joint ventures with host country companies, reflecting their low bargaining power vis-à-vis the latter (Lecraw 1983, 1984).

There has only been a limited attempt to theoretically or empirically model the behaviour of the new breed of MNEs from emerging or developing countries, and the factors that influence their decisions to invest overseas. It has been argued however that the main driver of outward investment by these firms is acquisition of tangible and intangible resources (Makino et al. 2002; Mathews 2002, 2006; Luo and Tung 2007). In particular, MNEs from developing countries use international expansion to acquire knowledge and capabilities in which they have comparative disadvantage (Barlett and Ghoshal 1988; Madhok 1997; Luo 2000). This is in contrast to the established MNEs from the developed world, which typically seek tangible resources and markets by leveraging their proprietary knowledge of technology, products and processes.

This literature is discussed in detail in Bhaumik et al. (2010) who outline both the motivations and limitations for firms from emerging or developing countries to engage in FDI. This is explained in the context of firms, who have generated certain core competences at home, but now seek to extend this abroad. Bhaumik et al. (2010) show that many firms who are market leaders in emerging and transition economies are successful in relatively standardised products, such as generic pharmaceuticals. Such firms internationalise to acquire such firm-specific advantages (Mathews 2002; Luo and Tung 2007). Rugman (2008) has argued that MNEs from developing countries might, therefore, be more reliant on country-specific advantages such as scale and scope economies, access to key natural resources or support from the state and its apparatus (Buckley et al. 2007, 2008; Fleury and Fleury 2008).

If a DMNE’s strategy involves using outward FDI as a vehicle for acquiring world class technology (e.g., product patents), their ability to leverage the acquired knowledge in the global market would critically dependent on the stock of their own embedded tacit knowledge. In sum, innate or firm-specific capabilities that lie at the heart of the OLI paradigm facilitate outward FDI of emerging market firms to both developed and developing countries, albeit for very different reasons. Bhaumik et al. (2010) extend these arguments however, by linking the FDI decision to home country institutions. They argue that certain extremely successful firms from developing or emerging countries may be less likely to engage in FDI. This is as a result of the specific ownership structures that evolve in developing countries, in response to weak institutions. As such, many successful firms from such countries are hesitant about engaging in FDI, and do so in order to acquire certain assets or new technology, much more readily than to engage in market seeking. This suggests therefore, that it may not be the most successful firms from these countries that engage in FDI, and where they do, it is more likely to be asset seeking behaviour, which in the short term is less likely to generate profits than market seeking.

As multinationals increase geographical diversity, the importance of the LOF of one particular subsidiary in terms of its impact on the parent, but also as firms become recognisable as global brands the LOF in a given location reduces. As Cantwell et al. (2010) outline, the coevolution of host country institutions and multinationals play a part on this, placing the emphasis on host country institutions as part of the firms global competitiveness. Equally, institutionals from the home country may be transferred within the MNEs (Cantwell et al. 2010), and as such country of origin governance and legal structures help develop a multinational’s reputation, thus speeding the acceptance of a foreign firm in the host country (Moeller et al. 2013). Multinationals from developing countries however face the reverse problem, and have less experiences and resources to overcome LOF the host country (Calhoun 2002).

Hypothesis 3:

Developing country firms will gain through investing in other developing countries, though these gains occur at a slower rate than for developed country firms.

A detailed synopsis of the literature is presented in Yang and Driffield (2012) who also discuss the varying results in some detail. Specifically, the different estimated rate of returns and its shape across studies are in part explained by sampling and methodological heterogeneity.

Our Contribution

This paper departs from the empirical studies presented above in three major aspects. Our contributions are based on the analysis of a large muti-country data set, providing information on the parent-affiliate links of some 16,835 firms, across 46 countries, including developed, transition and developing country firms as both host and home country firms. Crucially we have information for both the parent and affiliate. This contrasts with much of the previous literature which is based on a small number of countries (many are single country studies) and typically fewer than 200 firms. This enables a more sensitive and sophisticated form of analysis, including examining sections of the data separately, contrasting different types of location for example.

Based on this, we then develop the second contribution, which concerns the identification of the importance of location in the MP relationship, the distinction between developing and developed countries as host locations in particular. We argue that the location choices of overseas investment—in particular the developed/developing nature of the host country—may be a crucial aspect to explain the performance of multinational firms. In our view there are important areas of differentiation between developed and developing countries—infrastructures, political stability, raw materials, transportation costs—that can play a significant role in explaining how well multinationals do in their expansion strategies. Therefore, these two types of countries should not be lumped together when assessing the effects of international expansion upon firm performance, unlike in previous research. We consider the location choice of investing in developed versus developing countries as particularly important to inducing differential effects on the performance of firms engaged in FDI, in terms of the expected returns of investment in different locations.

Finally, this paper explores the importance of the source country. We provide a perspective of the internationalization of developing country MNEs investing in other developing countries, by comparing the impact of overseas investments on this subsample of multinationals with other multinationals on different source-destination country combinations.

The Empirical Specification

We estimate the relationship between multinationality and firm performance from the two following main equations:

and

where \({Y_{it}}\) is the return on sales of firm i in year t. \(OST{S_{it}}\) refers to the ratio of number of foreign subsidiaries in relation to total subsidiaries over the same period. \(OSTS_{it}^{D\prime ed}\) \(( {OSTS_{it}^{D\prime ing}} )\) is the ratio of number of overseas subsidiaries in developed (developing) countries in relation to total subsidiaries, i.e., \(OST{S_{it}} = OSTS_{it}^{D\prime ed} + OSTS_{it}^{D\prime ing}\). As mentioned above, the equation also includes other control variablesFootnote 1, including assets, firm age, ownership structure, industry and country effectsFootnote 2 \(( {{X_{it}}} )\) and business cycle effects \(( {{\gamma _t}} )\). The key parameters in terms of testing the three hypotheses are \({\beta _1}\), which indicates the average change in performance driven by changes in overall multinationality, \({\beta _2}\) and \({\beta _3}\), which indicate the average change in performance attributed to changes in the overseas presence in developed and developing countries, respectively. These are then derived for different types of firms, in line with the hypotheses 1–3. Our initial focus is on \({\beta _1}\) in the baseline model, to determine the average impact that increased internationalisation has an average firm.

Hypothesis one then extends this to examine the nature of this relationship, and the existence of nonlinearities with the inclusion of higher terms, using the following specifications:

and

in which we add the squares of \(OST{S_{it}}\) and of \(OSTS_{it}^{D\prime ed}\) and \(OSTS_{it}^{D\prime ing}\) to Eqs. 1 and 2, respectively. The focus therefore again is on the terms \({\varphi _1}\) and \({\varphi _2}\) in terms of hypothesis 1, and on \({\varphi _3}\)–\({\varphi _6}\) in terms of hypotheses two and three.

Data

Our analysis draws on the Orbis dataset, which provides detailed accounting and financial information for the largest firms across the world. The data are collected and made available by Bureau van Dijk, a large international consultancy firmFootnote 3.

The records of each company include information on whether the company has ownership stakes in its subsidiaries (defined as a minimum 25.01 % shares control over its overseas subsidiary) and the subsidiary location. Therefore, we are able to calculate the ratio of subsidiaries in foreign countries in relation to its total number of subsidiaries—the proxy for the level of multinationality of a firm that we consider in this paper. The financial and operational information of the firms in our data is generally available for the period 1997–2007, but multinationality information concerns only the latest year available in the data, which in most cases in 2005 and 2006.

We consider firms that have information available on expenditure on employees, assets, firm age, return on sales, and number of subsidiaries (including overseas subsidiaries). Firms without at least one of these variables are excluded from our sampleFootnote 4. As all monetary measures are reported in home currencies, we convert them to euro using annual exchange rates retrieved from the IMF.

In the data set that we consider, firms’ home countries are concentrated in the US, European Union, and some developing countries. These are significant numbers of firms based in France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK, the US and Taiwan. Moreover, we also find that the pattern of firm location is broadly consistent with typical patterns of investment.

Key Variables

The main variables considered in this study are the following:

Firm Performance.

During the last 30 years, several performance measures have been considered in the MP literature, including accounting-based variables (return on assets, return on sales, return on equity, etc), market-based variables (Tobin’s q, risk-adjusted returns, etc), innovations, patents, and technical efficiency. Accounting- and market-based variables became predominant in the last decade, as can be seen from Yang and Driffield (2012). In our paper, multinational performance is measured using (consolidated) return on sales (ROS), an accounting-based variable defined as after-tax profits divided by total sales. Return on equity and return on assets were excluded because they are sensitive to capital structure differences (Hitt et al. 1997; Li et al. 2007; Qian et al. 2008), which will be used as independent variables in our estimation equation. Market-based performance variables were excluded as they are not available for all countries. In any case, ROA and ROS are highly correlated, generating similar results (Hitt et al. 1997; Capar and Kotabe 2003).

Multinationality.

Although a considerable number of studies have tested the MP relationship, almost all of them have used aggregate measures to calculate a firm’s multinationality level. Our paper uses one common multinationality measurementFootnote 5, the ratio of the number of overseas subsidiaries in relation to all subsidiaries (OSTS)Footnote 6. We exploit the availability in our data set of information on whether the company has an ownership stake on its subsidiaries. Moreover, we also draw on information about the subsidiary location to separate domestic from overseas subsidiaries released. All information on subsidiaries refers to the latest year in which the firm appears in the Orbis dataset.

However, as we mentioned above, OSTS or other typical measures of international involvement cannot capture any differentiated effects from location choices upon performance. In particular, the costs and benefits associated with various country environments may vary widely. Therefore, our paper takes different location choices of overseas investment into consideration (Pantzalis 2001; Berry 2006; Qian et al. 2008). Specifically, we split the locations of investment in terms of developed and developing countries, considering the latest World Bank definitionFootnote 7. We then measure the level of multinationality of each firm in three complementary ways: OSTS, the ratio of the number of overseas subsidiaries in relation to the firm’s total subsidiaries: \(OST{S^{D\prime ed}}\), the ratio of the number of subsidiaries in developed countries in relation to the firm’s total subsidiaries; and \(OST{S^{D\prime ing}}\), the ratio of the number of subsidiaries in developing countries in relation to the firm’s total subsidiaries.

We also consider firm size, as a proxy for the physical and financial resources of a firm, in terms of the log of total assets (Pantzalis 2001) and the log of the number of employees (Elango 2004; Qian et al. 2008).

Other controls.

As in other studies, we also control for a number of other variables that may also influence firm performance and be correlated with multinationality, including firm age, ownership structure and business cycle (year) effects. Firm age is measured as the log of actual duration of existence of a firm since the starting year of its operations (Qian et al. 2008). In addition, ownership structure is controlled for by calculating the ratio of shares owned by foreign firms in relation to total shares (Pantzalis 2001). We also control for industry and country effects in our analysis.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents summary statistics from our data set. There is a total of 16,835 multinationalsFootnote 8, defined here as firms with at least one foreign subsidiary. The left panel of the table presents the summary statistics, while the right panel reports the correlation among the variables included in our estimations.

The left panel of Table 1 shows that, on average, a multinational firm in our data has 9.9 overseas subsidiaries in total. Almost seven (7.03) subsidiaries are located in developed countries, while the remaining three (2.86) are located in developing countries. In terms of ratios, 56 % of the multinational subsidiaries are located in overseas markets (OSTS), 38 % are located in developed economies \(( {OST{S^{D\prime ed}}} )\), and 19 % are located in developing countries \(( {OST{S^{D\prime ing}}} )\). It also shows that on average the return on sales for multinational firms is 0.07, and multinational firms are 37 years old, and have a value of capital of 1,515 million €, and employ 4,676 workforces.

The right panel of Table 1 shows that the calculated r values are not suggestive of multicollinearity. The correlations among employment, assets, firm age and foreign ownership range from 0.03 to 0.40. Furthermore, the correlation between \(OST{S^{D\prime ed}}\) and \(OST{S^{D\prime ing}}\) is − 0.45, suggesting there is no issue of multicollinearity when including both \(OST{S^{D\prime ed}}\) and \(OST{S^{D\prime ing}}\) simultaneously in the estimationFootnote 9.

Results

Table 2 reports our main estimates. The control variables have the expected signs and sizes in terms of their roles upon our measure of firm performance. Total Assets, age and foreign ownership predict higher levels of firm performance, while employment is negative, suggesting that labour intensive firms perform worse than capital intensive firms. These signs are largely unchanged across all specifications in columns 1–4, when controls for different types of multinationality are included. Our focus however is on the OSTS terms, linked to our hypotheses. Column 1 illustrates a positive and significant relationship between multinationality and firm performance, controlling for firm characteristics. This is important, as it confirms ceteris paribus that a firms’ FDI strategic decision is related to its set of firm specific characteristics and assets, and therefore that our model is consistent with IB theory.

Column 2 represents the test of hypothesis one, and highlights the nonlinear nature of the relationship. Overall, there is a positive and very significant relationship between multinationality (as proxied by OSTS) and firm performance, as illustrated by the coefficient on OSTS2. While the coefficient on the linear term is significant only at the 15 % level when the squared term is included, the coefficients suggest some evidence of a U-shaped relationship, and a turning point of a value of OSTS of 0.4. We now turn to the test of hypothesis 2, and the distinction between FDI to developed and developing countries. Column 3 we control for developed and developing subsidiaries shares, following the specification of Eq. 2. It indicates that the developed subsidiaries coefficient is small and insignificant while the developing subsidiaries coefficient is bigger, at 0.0132, and significant at the 1 % level, suggesting that a 10 percentage-point increase in the share of overseas subsidiaries in developing countries with respect to total subsidiaries translates into an increase of return on sales of 0.00132. Although this point estimate is small, it compares with a mean return on sales of 0.07, suggesting a significant economic effect. Overall, we conclude from this set of results that the developing subsidiaries have a stronger linear effect upon multinational performance.

Column 4 in Table 2 reports our estimates of the equations including the higher order terms, for both total OSTS, and for developed and developing host countries separately. This illustrates little effect in terms of FDI to developed countries, but a significant effect in terms of FDI to developing countries. Interestingly, the turning point value for OSTS to developing countries is under 25 %, such that the value after which the returns to internationalisation in developing countries increase is earlier than for the overall sample. The lack of significant results with respect to FDI to developed countries is indicative of too much heterogeneity within the sample, as it is likely to include FDI motivated by many different factors, including technology sourcing from developing countries to developed countries, market or strategic asset seeking between developed countries, and even efficiency seeking between developed countries. As such, we investigate this relationship further by examining this more closely.

From this set of results, we conclude that the relationship between multinationality and performance appears positive and essentially linear. However, when separating between overseas subsidiaries in developed and developing countries, we find that only the latter appear to induce nonlinear effects, and the \(OSTS_{it}^{D\prime ing}\) corresponding to the turning point is 23.3 %. In other words, performance appears to decrease at early stages of investment in developing countries before positive returns can be realizedFootnote 10. This result may support the views that underline the large costs arise from higher entry barriers, cultural distance, regulatory barriers and delays involved in subsidiaries in developing countries. These costs are then likely to become relatively small only when the size of the investment in such subsidiaries is big enough.

The Importance of Home Country Effects

In order to further examine hypothesis 2, and to test hypothesis 3, we employ the specifications outlined in Eqs 3 and 4, but distinguish between the developed/developing status of the home country of the multinationals in our data. Our interest in this decomposition follows from the evidence of an increasing number of multinationals emerging from developing countries, contrasting with the focus in the literature on multinationals based in the US (and, to a lesser extent, other developed countries too).

Columns 1–4 of Table 3 present our results based on multinationals based in developed countries only. We find, similar to the results for all firms, a positive effect from foreign presence, in particular that in developing –countries. Moreover, when we allow for nonlinear effects, we find again that there are no nonlinear effects in the case of subsidiaries in developed countries, while the effects of developed country firms investing in developing countries are non-linear. The turning point in the U-shaped relationship is reached at a value for OSTS of 24 % in developing countries.

Next in column 5–8 we consider only those multinationals that have their headquarters in developing countries. As expected, the number of observations in this analysis falls considerably, which may have implications in terms of the statistical significance of our results. It finds there is no positive effect from overseas expansion upon multinational performance: The OSTS coefficient in column 5 is − 0.0035 but insignificant. When controlling simultaneously for foreign penetration in both developed and developing countries, both coefficients are insignificant. The developed country coefficient is − 0.0246 (robust standard error is 0.018), suggesting a small insignificant negative effect.

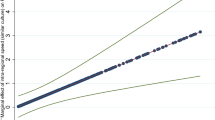

We also extend the analysis of multinationals based on developing countries to nonlinear specifications and in columns 7 and 8 we find no evidence of a curvilinear relationship. The exception is when differentiating between developed- and developing-countries subsidiaries, in which case we find a significant effect from the curvilinear term of 0.084. The turning point however is much later than for developed country multinationals, with a value of OSTS being 0.44 before the returns to internationalisation increaseFootnote 11. We present the plotted U-shaped relationship between firm performance and multinationality in Fig. 1. The four curves represent the different impacts of FDI on firm performance: (1) All FDI; (2) FDI to developing countries; (3) FDI to developing countries by firms from developed countries, (4) FDI to developing countries from developing countries. All demonstrate the U-shaped relationship between FDI and firm performance, while the turning points differ. MNEs from developing countries exhibit the positive returns, but at later stage of their overseas expansions. This figure also highlights the difference between the developed and developing sample. The full sample illustrates a relatively flat U-shape, while the relationship is much more pronounced for the developing country sample. The effect of developing countries MNEs investing in other developing countries highlights both the losses that the firm will face in the short run, and the length of time for which these will be incurred, before eventually seeing greater returns. This contrasts with firms from rich countries investing in developing countries, where the gains are much faster, and sustained.

Curvilinear U-shapes. We present the plotted U-shaped relationship between firm performance and multinationality. The four curves represent the different impacts of FDI on firm performance: (1) All FDI reported in column 2 of Table 2 (the solid line); (2) FDI to developing countries reported in column 4 of Table 2 (the dot line); (3) FDI to developing countries by firms from developed countries reported in column 4 of Table 3 (long dash dot); (4) FDI to developing countries by firms from developing countries reported in column 8 of Table 3 (short dash dot)

Finally, we conducted a number of additional robustness tests, which are reported in Table 4. First of all, we consider our measure of multinationality, and the fact that that a firm with one domestic and one foreign subsidiary and a second firm with 50 domestic and 50 foreign subsidiaries will have the same degree of multinationality as measured by OSTS. We therefore include an alternative set of multinationality measures: The number of foreign subsidiaries (Overseas Subsidiaries), the number of foreign subsidiaries in developed countries (Overseas \(Subsidiarie{s^{D\prime ed}}\)), and the number of foreign subsidiaries in developing countries (Overseas \(Subsidiarie{s^{D\prime ing}}\)). Columns 1 and 2 show that there is a positive MP relationship, and multinational firms have a higher return to investing in developing countries, compared with investing in developed countries.

Next we re-estimate the MP relationship, distinguishing between four sub-samples, i.e., (1) MNEs who have predominantly expanded into developed nations (\(OST{S^{D\prime ed}}> OST{S^{D\prime ing}}\) in column 3); (2) MNEs who have predominantly expanded into developing nations (\(OST{S^{D\prime ed}} < OST{S^{D\prime ing}}\) in column 4); (3) MNEs who have expanded only into developed nations (\(OST{S^{D\prime ed}} = 1\) in column 5); and (4) MNEs who have expanded only into developing countries (OSTSD′ing = 1 in column 6). The results in all columns reaffirm that multinationals have higher returns to investing in developing countries relative to developed countries.

Furthermore, in column 7 we introduce a variable which measures the average GDP per capita for the nations in which each firm has overseas subsidiaries (GDP (Host country)). We find both multinationality (as proxied by OSTS) and host country GDP coefficients are positive, while the interaction between OSTS and host country GDP is negative, suggesting the MP relationship is lower when overseas subsidiaries are located in advanced countries. Lastly, the specification in column 8 only includes firms which have at least one domestic subsidiary, in order to rule out that the results are driven by firms which do not have domestic subsidiaries while they report high domestic sales from the headquarters. The results are robust to this specification, and we again find the MP relationship is higher when overseas subsidiaries are located in developing countries.

Extension

Our data include information on whether the company has an ownership stake in a foreign affiliate and identifies affiliates by name. We are therefore able to find matches between multinational parents and their matched foreign subsidiaries. Over the period 1996–2007, we find 6,442 parents and 19,070 foreign subsidiaries.

In this extension, we exploit this different version of our data to study the relationship between overseas subsidiaries’ assets and the parents’ performance. This approach is in many ways more satisfactory than the traditional methods used in the literature, as one can measure with some precision the actual relevance of a subsidiary in terms of the conglomerate, rather than just assuming that all subsidiaries are equally important, for instance. The cost of this approach is that we have to draw on a smaller data, even if still large by the standards of the previous literature.

In the case of this new data set, including information about characteristics of parents and subsidiaries, we find that the parents are concentrated in developed countries, with significant numbers in France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, the UK and the US (60.84 % of all parents). The majority of overseas subsidiaries are also found in these countries as well as Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Ireland, Poland, Portugal, Singapore and Spain, where they account for 68.47 % of total overseas subsidiaries. The average net profit for each parent is 6.4 million €, and average overseas assets in developed (developing) countries of each parent are 31.7 (67) million €.

The relationship between parents’ profit and overseas subsidiaries’ assets in our analysis is estimated from the following equations:

Where \({Y_{it}}\) is the net profit of firm i in period t in logarithm. OAitD′ed(OAitD′ing)\(OA_{it}^{D\prime ed}( {OA_{it}^{D\prime ing}} )\) is the overseas assets in developed (developing) countries of firm i in period t (measured in logarithms). The equation also includes industry and region effects (\({X_{it}}\)) and business cycle effects (\({\gamma _t}\)). The key parameters are \({\beta _1}\) and \({\beta _2}\), which show the average change in performance related to overseas presences in developed and developing countries, respectively.

We also test the curvilinear MP relationship, drawing on the following equations:

in which we add the squares of \(\textit{OA}_{it}^{D'ed}\) and \(\textit{OA}_{it}^{D'ing}\) to equation 5 to test the curvilinear MP relationship.

Table 5 reports our estimates of the equations above. The main results prove to be similar to our previous analysis as there is a positive effect from foreign presence, in particular that in developing countries. Columns 2 and 3, presenting the results from the separate estimation of the role of developed and developing subsidiaries on parents’ profit, indicate that the latter are much more positive and significant. Column 2 indicates that the developed subsidiaries coefficient is 0.010 (and only significant at the 10 % level), while column 2 shows that the developing subsidiaries coefficient is almost twice as big, at 0.019, and significant at the 5 % level. However, both coefficients become insignificant when we control for both \(\textit{OA}_{it}^{D'ed}\)and \(\textit{OA}_{it}^{D'ing}\) in column 4.

In columns 5–8 we then consider the curvilinear nature of the MP relationship. In columns 5 and 6 we find evidence of an inverted U-shaped model in the case of all and developed-country-only subsidiaries, given that the linear term is positive and the quadratic term is negative, and they are both significant. However, in column 7 we find no evidence of nonlinearities in the case of developing-country subsidiaries as all terms are insignificant. Finally, when we pool the quadratic controls for developed- and developing-country subsidiaries, we find again that all terms are insignificant.

We regard these results as supportive of our main findings about the greater role of developing-country subsidiaries than their developed-country counterparts in terms of multinationality performance. However, unlike in the case of our main analysis, drawing on the OSTS measure, here not all results are particularly robust (not reported but available upon request). This can be explained by taking into account the data restrictions in this extension. For instance, while on average each parent has ten overseas subsidiaries (see Table 1), here, again on average, we could only draw on information on three of those subsidiaries. Moreover, missing observations force us to drop multinationals that have both developing- and developed-country subsidiaries, which makes the contrast between the effects of each type of affiliate less robust.

Conclusions

The large literature on the relationship between multinationality and performance is almost exclusively based on data from specific home countries (typically the US) and a period of time focused on the 1990s. Moreover, the literature typically does not distinguish between different host economies (Beugelsdijk et al. 2010), in particular in terms of their level of economic development. We believe these can be important shortcomings, in particular the aggregation of subsidiaries into a single variable, regardless of the level of development of the host economy. Since globalisation has been opening up new destinations for FDI which typically exhibit considerable heterogeneity, the performance effects from multinationality can be more diverse than from previous periods.

This paper fills these research gaps by examining a large sample of multinationals (over 16,000) from a very large number of countries (46) over a recent period (1997–2007). Our central finding is that while the relationship between multinationality and performance follows a positive pattern in general, that relationship is not only positive but also bigger for the case of investment in developing economies. In other words, our estimates indicate that the effects from investing abroad on firm’s return on sales are stronger in the case of developing-country subsidiaries when compared with developed-country counterpartsFootnote 12. This is to some extent consistent with recent work by Doukas and Kan (2006) and Driffield and Yang (2011), suggesting that FDI between developed countries is motivated by merger and acquisition activity and firm growth that may not necessarily result in profit growth.

We interpret these results as indicating that the potential of globalisation, in particular in terms of increasing investments in developing countries, has not yet been met by multinational firms. In particular, geographical diversification into developing countries may be an important source of competitive advantages that deserves more serious consideration from business leaders and academics alike. Moreover, the most promising expansion strategies may involve setting up more subsidiaries in developing countries. This can be rationalised by taking into account not only the many obstacles in developing countries but also the likely similarities of such obstacles across developing countries. Despite the negative returns to investing in developing countries at early stages, due to foreignness liabilities, the positive return will be realized at later stages. Indeed, a comparison of the turning points derived in this analysis is also informative. Overall, 40 % of a firms assets must be held abroad before the firm starts to gain from internationalisation, while for developed country firms investing in developing countries, this falls to 25 %, and increases to 44 % for developing country MNEs investing in other developing countries. This not only confirms the importance of location in the MP relationship, but also highlights the theoretical contribution of these links. The key ownership advantages of developing countries MNEs concern economies of scale, and the ability to work within a potentially weak institutional framework. As such, these advantages are less easily exploited in other countries. Western MNEs however are characterised by technological or managerial advantages, and so the returns to linking those to the location advantages offered by developing countries, in terms of low labour costs for efficiency seeking, or low levels of competition for market seeking firms. The returns to investing in developing countries then occur more quickly for western MNEs investing in developing countries. DMNEs make no apparent gain from investing in developed countries, and make gains from investing in other developing countries when their overseas assets ratio reaches 44 % which is the highest turning point in our results. This suggests that a good deal of learning is required for gains from internationalisation to be realised by DMNEs, and that their ownership advantages are the least transferable internationally.

The final result concerns the success of developing country firms who invest in other developing countries. This is where the U-shape is most pronounced. Initially, such firms suffer the most from the LOF, having the fewest resources to overcome these constraints, and a lack of institutional and technological support at home. However, over time as they overcome LOF, their familiarity with relatively weak institutions means that they face less uncertainty, and fewer constraints from the weak institutional environment because they are used to operating in such an environment at home. Bhaumik and Driffield (2011) for example show that for India, firms that have developed through business links, or family connections, perhaps in lieu of institutional support are less likely to invest in developed countries, but more likely to invest in other developing countries.

One limitation of our study is the cross-sectional nature of our data set that do not allow for controlling unobserved fixed effect at the firm level. This also prevents us from relating the changes in multinationality within firms to the changes in their performance over time, holding constant time-invariant factors that may affect both multinationality and firm performance. Our estimates also do not rule out some form of reverse causality: Maybe only sufficiently profitable multinationals can afford to establish subsidiaries in developing countries, and also our estimates do not rule out some form of sample selection bias. Finally, additional robustness checks would involve the consideration of complementary measures of multinationality. We leave these topics for future research.

Notes

We re-ran our estimation regressions including variables, such as intangible assets, long term debt, and average earnings (as a proxy of labour quality) as different indicators or measures of firm heterogeneity. We find the results are robust. However, these are not available for the full sample of firms, and they are available for just over half, and only available for developed countries firms. These are available upon the request.

Without controlling for firm age, assets, ownership and number of employees, we again find there is U shape correlation between multinationality (OSTS) and firm performance. However, we are not concerned that interpretation of point estimates, when key control variables are missing may be open to misinterpretation, especially as a key role of these variables is to control for unobserved heterogeneity. We believe the estimates without controlling for firm heterogeneity are biased. These estimates are available upon the request.

Orbis also contains further detail such as news, market research, ratings and country reports, scanned reports, ownership and mergers and acquisitions data. Orbis has a large number of additional reports per company, in particular about listed companies, banks and insurance companies, and other major private companies. See Ribeiro et al. (2010) for more information on the Orbis data set and Bhaumik et al. (2010) and Martins and Yang (2010) for other papers that use this data set.

This criterion leads to the exclusion of several firms in some countries, in particular Canada and India. However, this is not a relevant problem for the overwhelming majority of countries.

Another common aggregate multinationality measure used in the literature, i.e., the foreign to total sales ratio, is not available in the Orbis data set. However, one potential problem with this variable is that the level of the firm’s sales in foreign countries typically does not exclude intermediate goods exported from the home country and resold by its overseas subsidiaries, resulting in possible bias to the MP estimate (Geringer et al. 2000; Tallman and Li 1996; Qian et al. 2008).

In our data, developed countries include the members of G8 (except Russia), most EU members, Norway, Iceland, Switzerland, New Zealand, Australia, Bermuda, Israel, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and Hong Kong.

Firms are concentrated in some EU countries, most G8 countries and some developing countries. Taken together firms from US, UK, France, Germany, Italy and Japan, account for 56 % of the sample. The distribution of firms by country, along with the mean of most important variable by country used in our analysis are available upon the request.

We also tried a scatter plot of both the number of overseas subsidiaries in developed countries (Overseas \(Su{b^{D\prime ed}}\)) and in developing countries (Overseas \(Su{b^{D\prime ing}}\)), and we find some evidence of a trade-off between the two variables. This is available upon the request.

We tested for the potential of an S-shaped by including a cubic term in the regressions and also by the inspection of the summary statistics in Table 1. However, the average multinationality of firms investing in developing countries is 0.19 with a standard deviation of 0.27. Very few attain a 73 % degree of multinationality in developing countries, such that the existence of a third stage is moot.

Furthermore, we extended our analysis by incorporating weights of outward FDI of the country and then rerun our main specifications applying those weights. These results were robust and are available upon request.

While developing nations FDI affiliates are smaller and therefore have smaller net total profit compared with developed nations FDI affiliates, they are not less profitable in terms of return on assets or return on sales. In line with the literature, we use return on sales as the measure of profitability, making our results comparable with many previous studies of MP relationship (e.g., Geringer et al. 1989; Grant 1987; Tallman and Li 1996; Capar and Kotabe 2003), this measure indicates how much net income is earned from each sales per revenue.

References

Agmon, T., & Lessard, D. (1977). Investor recognition of corporate international diversification. Journal of Finance, 32(4), 1044–1055.

Annavarjula, M., & Beldona, S. (2000). Multinationality-performance relationship: A review and reconceptualization. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 8(1), 48–67.

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. (1988). Creation, adoption and diffusion of innovations by subsidiaries of multinational corporation. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(3), 365–388.

Bausch, A., & Krist, M. (2007). The effect of context-related moderators on the internationalization-performance relationship: Evidence from meta-analysis. Management International Review, 47(3), 319–347.

Benvignati, A. M. (1987). Domestic profit advantages of multinational firms. Journal of Business, 60(3), 449–461.

Berry, H. (2006). Shareholder valuation of foreign investment and expansion. Strategic Management Journal, 27(12), 1123–1140.

Beugelsdijk, S. (2007). The regional environment and a firm’s innovative performance: A plea for a multilevel interactionist approach. Economic Geography, 83(2), 181–199.

Beugelsdijk, S., McCann, P., & Mudambi, R. (2010). Introduction: Place, space and organization-economic geography and the multinational enterprise. Journal of Economic Geography, 10(4), 485–493.

Bhaumik, S., & Driffield, N. (2011). Direction of outward FDI of EMNEs: Evidence from the Indian pharmaceutical sector. Thunderbird International Business Review, 53(5), 615–628.

Bhaumik, S., Driffield, N., & Pal, S. (2010). Does ownership structure of emerging-market firms affect their outward FDI quest? The case of the Indian automotive and pharmaceutical sectors. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(4), 437–450.

Buch, C., Kesternich, I., Lipponer, A., & Schnitzer, M. (2009). Financial constraints and the margins of FDI. CEPR Discussion Papers 7444.

Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. C. (1976). The future of the multinational enterprise. New York: McMillan.

Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. C. (2009). The internalisation theory of the multinational enterprise: A review of the progress of research agenda after 30 years. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9), 1563–1580.

Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. C. (2010). The multinational enterprise revisited: The essential Buckley and Casson. New York: Macmillan.

Buckley, P. J., Clegg, J., Cross, A., Liu, X., Voss, H., & Zheng, P. (2007). The determinants of Chinese outward foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(2), 499–518.

Buckley, P. J., Cross, A., Tan, H., Xin, L., & Voss, H. (2008). Historic and emergent trends in Chinese outward direct investment. Management International Review, 48(6), 715–748.

Busse, M., & Hefeker, C. (2007). Political risk, institutions and foreign direct investment. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), 397–415.

Bruton, G. D., Filatotchev, I., Chanine, S., & Wright, M. (2010). Governance, ownership structure, and performance of IPO firms: The impact of different types of private equity investors and institutional environments. Strategic Management Journal, 31(5), 491–509.

Calhoun, M. (2002). Unpacking liability of foreignness: Identifying culturally driven external and internal sources of liability for the foreign subsidiary. Journal of International Management, 8(3), 301–321.

Cantwell, J., Dunning, J., & Lundan, S. (2010). An evolutionary approach to understanding international business activity: The co-evolution of MNEs and the institutional environment. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(4), 567–586.

Capar, N., & Kotabe, M. (2003). The relationship between international diversification and performance in service firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(4), 345–355.

Castellani, D., & Zanfei, A. (2007). Internationalisation, innovation and productivity: How do firms differ in Italy? World Economy, 30(1), 156–176.

Collins, J. M. (1990). A market performance comparison of US firms active in domestic, developed and developing countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 21(2), 271–287.

Contractor, F. J. (2007). Is international business good for companies? The evolutionary or multi-stage theory of internationalization vs. the transaction cost perspective. Management International Review, 47(3), 453–475.

Contractor, F. J., Kundu, S. K., & Hsu, C. C. (2003). A three-stage theory of international expansion: The link between multinationality and performance in the service sector. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(1), 5–18.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2006). Who cares about corruption? Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 807–822.

Dastidar, P. (2009). International corporate diversification and performance: Does self selection matter? Journal of International Business Studies, 40(1), 71–85.

Davidson, W. H. (1980). The location of foreign direct investment activity: Country characteristics and experience effects. Journal of International Business Studies, 11(2), 9–22.

Denis, D. J., Denis, D. K., & Yost, K. (2002). Global divarication, industrial diversification, and firm value. Journal of Finance, 57(5), 1951–1979.

Denk, N., Kaufmann, L., & Roesch, J.-F. (2012). Liabilities of foreignness revisited: A review of contemporary studies and recommendations for future research. Journal of International Management, 18(4), 322–334.

Doukas, J. A., & Kan, O. B. (2006). Does global diversification destroy firm value? Journal of International Business Studies, 37(3), 352–371.

Doukas, J., & Travlos, N. B. (1988). The effect of corporate multinationalism on shareholders’ wealth: Evidence from international acquisitions. Journal of Finance, 43(5), 1161–1175.

Driffield, N., & Love, J. (2007). Linking FDI motivation and host economy productivity effects: Conceptual and empirical analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(3), 460–473.

Driffield, N., & Yang, Y. (2011). Location choice of FDI: Evidence from matched samples. Working paper.

Driffield, N., Love, J., & Menghinello, S. (2010). The multinational enterprise as a source of international knowledge flows: Direct evidence from Italy. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(3), 350–359.

Dunning, J. H. (1979). Explaining changes of international production: In defence of eclectic theory. Oxford Bulletin of Economic and Statistics, 41(4), 269–296.

Dunning, J. H. (1988). The theory of international production. International Trade Journal, 31(1), 21–46.

Dunning, J. H. (1998). Location and multinational enterprise: A neglected factor. Journal of International Business Studies, 29(1), 45–66.

Dunning, J. H. (2009). The key literature on IB activities, 1960–2006. In A. Rugman (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of international business (2nd ed., pp. 39–71). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, M. (2008). Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Cheltenham: Elgar.

Eden, L., & Miller, S. (2004). Distance matters: Liability of foreignness, institutional distance and ownership strategy. Advances in International Management, 16, 187–221.

Elango, B. (2004). Geographic scope of operations by multinational companies: An exploratory study of regional and global strategies. European Management Journal, 22(4), 431–441.

Errunza, V. R., & Senbet, L. W. (1981). The effects of international operations on the market value of the firm: Theory and evidence. Journal of Finance, 36(2), 402–417.

Errunza, V. R., & Senbet, L. W. (1984). International corporate diversification, market valuation, and size-adjusted evidence. Journal of Finance, 39(3), 727–743.

Fleury, A., & Fleury, M. (2008). Brazilian multinationals: Surfing the waves of internationalization. In R. Ramamurti & J. V. Singh (Eds.), Emerging multinationals from emerging markets (pp. 200–243). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frynas, J. G., Mellahi, K., & Pigman, G. A. (2006). First mover advantages in international business and firm-specific political resources. Strategic Management Journal, 27(4), 321–345.

Geringer, J. M., Beamish, P. W., & DaCosta, R. C. (1989). Diversification strategy and internationalization: Implications for MNE performance. Strategic Management Journal, 10(2), 109–119.

Geringer, J. M., Tallman, S., & Olsen, D. M. (2000). Product and international diversification among Japanese multinational firms. Strategic Management Journal, 21(1), 51–80.

Ghemawat, P. (2001). Distance still matters: The hard reality of global expansion. Harvard Business Review, 79(8), 137–147.

Goerzen, A., & Beamish, P. W. (2003). Geographic scope and multinational enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 24(13), 1289–1306.

Gomes, L., & Ramaswamy, K. (1999). An empirical examination of the form of the relationship between multinationality and performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(1), 173–187.

Grant, R. M. (1987). Multinationality and performance among British manufacturing companies. Journal of International Business Studies, 18(3), 79–89.

Guisinger, S. (2001). From OLI to OLMA: Incorporating higher levels of environmental and structural complexity into eclectic paradigm. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 8(2), 257–272.

Habib, M., & Zurawicki, L. (2001). Country-level investments and the effect of corruption-some empirical evidence. International Business Review, 10(6), 687–700.

Habib, M., & Zurawicki, L. (2002). Corruption and foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(2), 291–307.

Hall, R. E. (2001). The stock market and capital accumulation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1185–1202.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M. J., & Yeaple, S. R. (2004). Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. American Economic Review, 94(1), 300–316.

Henisz, W., & Swaminathan, A. (2008). Institutions and international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(4), 537–539.

Hennart, J.-F. (1982). A theory of the multinational enterprise. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hennart, J. M. A. (2010). Transaction cost theory and international business. Journal of Retailing, 86(3), 257–269.

Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E., & Kim, H. (1997). International diversification: Effects on innovation and firm performance in product-diversified firms. Academy of Management Journal, 40(4), 767–798.

Hymer, S. H. (1976). The international operations of national firms: A study of direct investment. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm: A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23–32.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. E. (1990). The mechanism of internationalization. International Marketing Review, 7(4), 11–24.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. E. (2009). The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9), 1411–1431.

Johanson, J., & Wiedersheim-Paul, F. (1975). The internationalization of the firm: Four Swedish cases. Journal of Management Studies, 8(1), 305–322.

Kim, W., Hwang, P., & Burgers, W. P. (1993). Multinationals’ diversification and the risk-return trade-off. Strategic Management Journal, 14(4), 275–286.

Kogut, B. (1983). Foreign direct investment as a sequential process. In C. Kindleberger & D. Audretsch (Eds.), The multinational corporation in the 1980s (pp. 38–56). Cambridge: MIT press.

Kogut, B. (1985). Designing global strategies: Comparative and competitive value added chains. Sloan Management Review, 27(1), 27–38.

Kostova, T., & Zaheer, S. (1999). Organizational legitimacy under conditions of complexity: The case of the multinational enterprises. Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 64–81.

Lall, S. (1983). The new multinationals: The spread of third world enterprises. Chichester: Wiley.