Abstract

Today’s dynamic environment demands firms to adapt their business models as a new source of competitive advantage. This poses significant challenges to firms that are locked in their long-established structures, like family firms. We quantitatively test (n = 154) how dynamic capabilities (DC) affect business model innovation (BMI) in family firms and how this relationship is moderated by socioemotional wealth (SEW). DCs are essential for all types of firms to exploit opportunities and respond to technological changes in general. For family firms, they are particular important due to the desire to succeed for future generations. Given that family involvement in business creates idiosyncratic motivations and long-term characteristics that considerably affect the firm’s behavior, we state that their SEW endowment may influence the relationship between DCs and BMI. Measuring the constructs independently, our findings reveal strong sensing and seizing as well as transforming capabilities as relevant antecedents of BMI and stress upon the positive moderating role of SEW for the relationship between reflecting and BMI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In today’s dynamic environment, industry barriers are broken down by digital technologies that now spread into all markets and areas (Teece 2018; Archibugi 2017; Zott and Amit 2017). They provide novel ways of value creation while long-successful business models (BM) are replaced. Thus, firms need to adapt their BMs as a new source of competitive advantage (Ritter and Lettl 2018; Teece 2018; Schneider and Spieth 2013; Hienerth et al. 2011). Business model innovation (BMI) is defined by the search for new logics of the firm with the aim to develop new value offerings, new value chain structures or forms of value creation and capturing (Teece 2018; Foss and Saebi 2017). These result in new or renovated business models (Schneider and Spieth 2013). The dynamic capabilities (DC) approach in this regard is taking the rapidly changing environment into account (Teece and Pisano 1994; Schilke 2014). Striving for and recognizing new opportunities demands for the ability to reconfigure a firm’s existing resource base (Teece 2018; Chesbrough 2010; Mezger 2014), which poses significant challenges to companies that are locked in their long-established structures (Christensen et al. 2013), like family firms.

Family firms offer idiosyncratic characteristics (e.g., family ownership, management, and involvement) and motivations (e.g., transgenerational succession) that substantially affect the firm’s strategic behavior (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007; Kammerlander and Ganter 2015; Brumana et al. 2017). Such influence stems from the close overlap between the family coalition and the firm (Dyer and Whetten 2006), and from the family firm specific resources that family members often offer to the firm, such as time, labor, expertise, information or moral support. It is mainly consented that a large part of BMI phenomena can be better understood when both family and firm dimension are considered (Marchisio et al. 2010; Pieper 2010). Nevertheless, the direction of such influence still remains unclear (Chrisman et al. 2015). Most of the studies are mainly conceptual. The few empirical ones are largely consistent in identifying a negative effect of family involvement on technological innovation inputs (e.g., Block 2012; Kotlar et al. 2013) but they remain mixed regarding the relationship between family involvement and technological innovation outputs (e.g., Classen et al. 2014; Matzler et al. 2015). To account for these mixed findings, a theoretical perspective that allows a nuanced understanding of the family firm-specific phenomena is required (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007). Within the context, the multi-dimensional socioemotional wealth framework (SEW; Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007) has been proposed as an umbrella concept to capture the different noneconomic goals and emotional utilities that family members derive from owning a firm over an extended period of time (Calabró et al. 2016; Urbinati et al. 2017; McKelvie et al. 2014). Their aim to preserve the family dynasty or maintain family values through the firm may foster a commitment to building DCs (Berrone et al. 2012; Barros et al. 2016). Because the translation of DCs into BMI is a choice associated with the attitude of the family to contribute to organizational effectiveness—even when employing these capabilities is personally costly (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2018), family firms offer a specific context for studying the role of DCs as driving factors of BMI.

The purpose of this study is to address the question in how far dynamic capabilities affect business model innovation in family firms, and how these relationships are moderated by socioemotional wealth. We quantitatively test our hypotheses on a sample of 154 German family firms. In doing so, we find support for the importance of strong sensing and seizing, and strong transforming capabilities for BMI as well as a positive moderating effect of SEW on the relationship between reflecting capabilities and BMI in family firms. With this study, we contribute to entrepreneurship theory in a twofold way. First, we add to the scarce empirical evidence on which dynamic capabilities are needed to adapt a firm’s BM within a thriving business environment (Cozzolino et al. 2018). Studies have primarily been driven by explorative and individual case studies (Hacklin et al. 2018; DaSilva and Trkman 2014; Zott et al. 2011; Schneider and Spieth 2013) but a systematic understanding of the underlying capabilities and processes is necessary and missing (Cozzolino et al. 2018; Schneider and Spieth 2013; Sosna et al. 2010). We sought to overcome the predominantly static view adopted towards BMs in the literature (Demil and Lecocq 2010) by following general strategic management researchers who suggest DCs to be important facilitators of BMI (DaSilva and Trkman 2014; Mezger 2014; Schneider and Spieth 2013). Second, a large amount of studies in the family firms research field focuses on family influence on entrepreneurship (Sciascia and Bettinelli 2016; Kammerlander and Ganter 2015; Samei and Feyzbakhsh 2015) but the BM as the main model of analysis remains largely unobserved. In fact, research focuses mainly on technological innovation (Calabrò et al. 2018; Röd 2016; De Massis et al. 2013). Calabrò et al. (2018) recently conducted a thorough literature review on family firm innovation. They pointed out that a recurrent focus on the direct relationship between family involvement and innovation outputs is needed to broaden our limited understanding of the moderating role of family involvement on the innovation inputs-innovation activities and innovation activities-innovation outputs relationships. Therefore, we contribute to research by operating a detailed measurement of BMI, DC, and SEW to obtain very fine-grained results that enhance our understanding of the moderating role of family involvement (Zahra 2007).

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. The following section depicts the conceptual background and the derivation of our hypotheses. We then explain our sample and method, present our results, and discuss these. We conclude with implications and limitation of our study.

2 Conceptual basis

2.1 Business models and business model innovation

BMs are subject to change over time as in BMI (Teece 2018). For example, the German family firm Schoeller Group entered into the wood processing industry in the 20th century before pioneering bottle and food transportation (Rondi et al. 2019). They managed to constantly adapt their BM of the wood factory in Silesia. The Schoeller Group wooden firm previously produced wooden boxes and containers and become a large producer of crates. They realized that developing plastic bottle crates could dramatically increase service life, elasticity, reusability as well as hygiene of the bottle crates. This enabled them to individually brand the crates and use them as an advertising medium, thereby innovating the industry’s established BM.

The most common conceptualizations of BMs resemble the definition given by Teece (2010) who denotes a BM as the way in which a firm “delivers value to customers, entices customers to pay for value, and converts those payments to profit” (Teece 2010, p. 172). Given this definition, a BM comprises three main dimensions. The first one is value creation, which describes how a firm generates value along its value chain (Teece 2010; Schneider and Spieth 2013). This includes decisions as to which operative processes, which internal and external resources, and which organizational structures are necessary to create products and services (Fjeldstad and Snow 2018; Ritter and Lettl 2018). The second dimension is value proposition and describes how a firm delivers its created value by including a firm’s stakeholders, such as its customers, suppliers or other value partners (Chesbrough 2010; Teece 2010). This includes questions as to what needs or problems customers have and how the firm could offer solutions that go beyond the mere product or service by aligning its entire (service) package (Teece 2018). Lastly, value capture comprises aspects of how a firm earns money with the help of value creation and value proposition by encompassing the flows of revenues, costs and profits of the BM (Teece 2010, 2018; Spieth and Schneider 2016). It thus determines the value it generates for its owners. Although these three dimensions can be viewed as distinct entities, however, in a successful BM they should not be considered separately. A BM is not particularly successful because of the success of one of its components, but due to coordinated functioning of all its components (Zott and Amit 2017; Amit and Zott 2012). Foss and Saebi (2017) show in a recent review that we still have only limited understanding of where BMs come from—especially compared to the well-established literatures on product, process and service innovation. A reason for the lack of theorizing on BM dynamics may lie in the predominantly static view adopted towards BMs in the literature (Demil and Lecocq 2010). Hence, research on the antecedents that trigger changes in the BM architecture and on its facilitators, drivers and hindrances are only emerging (Foss and Saebi 2017). Due to the complexity of both BM and BMI terms, so far only few studies empirically investigated the BMI phenomenon. First studies connect the role of changes in the competitive environment with BMI (Laudien and Daxböck 2016; Buliga et al. 2016). These changes can be new information and communication technologies (Rindfleisch et al. 2017; Schilke 2014) or external stakeholders (Ferreira et al. 2013). Mezger (2014) and Günzel and Holm (2013) construed in multiple case analyses BM changes resulting from the advent of technological innovation in the specialized publishing industry. Hereby, they identify DCs as internal resources, which can be leveraged to be important facilitators that are required to face the necessary BM changes (Mezger 2014). Also Achtenhagen et al. (2013) conducted a systematic within and cross-case analysis of a longitudinal dataset from 25 small and medium-sized firms. They identified DCs as micro-aspects of successful BM change. Being increasingly permeated with environmental changes, like e.g. digital technology, has significant implications on the manner how firms sustain a competitive advantage.

2.2 The dynamic capabilities view

The Schoeller Group could only advance BMIs by harnessing the firm’s resources to a coherent, yet adaptive strategy that took the rapid environmental changes and new external circumstances into account. The family owner and managers constantly used their capacity to learn, sense, filter, and shape opportunities. Thereby they realized the huge opportunity of producing crates from only one piece of material rather than from dozens of separate pieces by using injection molding, which was much more efficient than the competitors’ production (Rondi et al. 2019). This example demonstrates very nicely the specifics, and in case of the Schoeller group advantages, of family influence on the entrepreneurial behavior of the firm because the exploitation of capabilities is often dependent upon the capacities of the family owner managers.

Dynamic capabilities are the firm’s ability to identify, integrate, build, and reconfigure internal competences to address, or in some cases to bring about, changes (e.g., environmental or technological) (Teece and Pisano 1994; Teece 2007). Many scholars lately emphasized that DCs comprise external as well as internal components (Babelytė-Labanauskė and Nedzinskas 2017; Kump et al. 2018). Externally, they entail a firm’s capacity to continuously sense and seize the environment in order to develop or assess technological opportunities in relationship to customer needs. The focus lies on scanning, accumulating and filtering information on the organizational environment. Their core lies in recognizing whether specific information is of potential value, converting valuable information into concrete business opportunities and accordingly making decisions (Teece 2007). Especially in the context of BMI, these capabilities are required to identify opportunities and the need for adaptation based on information within the firm. Internally, the capabilities entail reflecting on implicitly held knowledge for learning, renewal and continuous optimization, and have been recognized by several strategic management scholars (Hodgkinson and Healey 2011; Bingham et al. 2015). Further, an essential capability is the actual realization of decisions into practice, e.g. for adjusting new advantageous (business model) configurations. Transforming the required structures and routines, providing the infrastructure and ensuring that the workforce has the required skills (Teece 2007; Kump et al. 2018) help firms to stay competitive. This shows how vital DCs are for maintaining long-term profitability. The capabilities firms already have are static (zero-order) abilities because they cannot convert unless they are acted on by DCs (Winter 2003). These, on the other hand, are “higher-order dynamic capabilities” (Zahra et al. 2006, p. 921) because whereas a novel routine for product development would be a new substantive base level capability, the actual ability to change such new capability is then a DC (Teece 2018). These DCs may vary in their strength (Zahra et al. 2006). Some existing conceptual research already states the importance of strong DCs for crafting new business and corporate strategies (Bowman and Ambrosini 2003), introducing programs that stimulate strategic change (Repenning and Sterman 2002), or even for BMI (Teece 2018; Wu et al. 2012). Especially to family firm entrepreneurship research, the importance of the DC view has lately been emphasized (Sirmon and Hitt 2003; Chrisman and Patel 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al. 2014; Fitz-Koch and Nordqvist 2017; Samei and Feyzbakhsh 2015). Building upon dynamic capabilities that help a firm to adapt to the ever-changing environment is especially important to established organizations like family firms who follow a desire to maintain successful for future generations.

2.3 Socioemotional wealth

Over the generations, the Schoeller group passed on their entrepreneurial heritage (Rondi et al. 2019). Members of the current 8th generation decided to set up an own business right after graduating from university with the aim to generate and exploit as many synergies as possible between their start-up and the family firm. The start-up offers environmentally friendly and reusable removal crates made of recyclable plastic fabric. The conversion of essential capabilities into entrepreneurial activities is largely contingent upon the attitude and values of the entrepreneurial family.

In family firms, the borders between family and firm are often blurred and inseparable ties between the dominant family coalition and firm exist. In this paper, we define family firms by a family’s ownership and control of a firm and a vision for how the firm will benefit the family, potentially across generations (Chua et al. 1999). Our conceptual frame is supported by the behavioral agency theory (Wiseman and Gómez-Mejía 1998), which sees decision makers not as constantly risk averse but as loss averse. Decision makers try to protect their endowments (Martin et al. 2013). The theory entails the assumption that emotional attachment and judgment of family members are inseparably intertwined (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007). Gómez-Mejía et al. (2007) developed the socioemotional wealth (SEW) paradigm, which is a multi-dimensional framework that has been established to reflect the complexity and heterogeneity of family influence (Calabró et al. 2016; Urbinati et al. 2017; McKelvie et al. 2014). It covers dimensions like a family’s intention to pass on the firm to the next generation, the employment of family members, the exercise of authority within the enterprise, emotional benefits derived from close identification with the firm and its employees, and the ability to retain family control (Berrone et al. 2012). One specific aspect about the family-firm context is that whenever family members are involved in the management they are able to transfer their vision and values to the firm through interaction and mutual trust (Sirmon and Hitt 2003). Hence, in these types of firms, the primary reference of potential gains or losses is SEW (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007, 2018), and decision-making processes and outcomes, e.g. regarding R&D expenses or the introduction of digital technologies, tend to be motivated by the family owners’ perception of threats to their SEW endowments (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007, 2018). These SEW reference points can be even more important than economic ones. Due to the blurred borders, the strong interaction among the family, its individual members and the business (Nordqvist and Melin 2010; Jaskiewicz et al. 2015; Minola et al. 2016), family firms build a specific context for BMI. They have been found to pursue diverse business initiatives across multiple-generations (Nordqvist and Melin 2010; Jaskiewicz et al. 2015; Minola et al. 2016). Also their desire to hand over a successful business to the next generation can motivate family firms’ owners to focus on business growth (Eddleston et al. 2008). Because strategic changes and BMI are always related to risk, SEW has recently been applied to predict family firm entrepreneurial behavior. Nevertheless, the direction of family influence on entrepreneurship still remains unclear (Chrisman et al. 2015).

3 Conceptual model and development of hypotheses

It is widely recognized that strong DCs lead to more flexibility and superior innovation output (De Massis et al. 2016) because resources and substantial abilities are directly involved in the process of converting inputs into outputs (Miller et al. 2015). Today, BMI often involves an entrance into areas with high technological intensity, which is independent from a firm’s core business and thus new strategic assets have to be integrated within the business (Nambisan et al. 2017). Because new technologies entail a high speed of development, establishing strong sensing capabilities is very prosperous for BMI. Especially at an exploratory stage of a BMI, when new BMs are being conceptualized, decision-makers face the unpredictability of fast-evolving markets (Sosna et al. 2010). Existing research state that BMI demands for a high level of market expertise and internal tacit knowledge (Baden-Fuller and Morgan 2010; Teece 2010; Wirtz et al. 2010). In this sense, strong DCs ensure the survival of a firm against competitors (Carnes and Ireland 2013; De Massis et al. 2016). For example, firms with strong sensing and seizing capabilities were found to use a variety of media to scan information from a wide array of sources (Liao et al. 2009). Only those firms that manage to recognize trends impacting the socio-economic business environment and constantly adapt to these changing conditions are able to survive. An early recognition enables a firm to proactively act instead of having to react to external circumstances. The sensing capability, in this regard, depicts the identification of technological possibilities or new technology developments at an early stage and enhances a greater knowledge of best practices and competitor’s activities in the market (Teece 2007; Kump et al. 2018). While the development of DCs is relevant to all types of firms, family firms build a specific context for studying the importance of DCs for BMI (Calabrò et al. 2018) due to their long-term strategic focus (Bammens et al. 2015). Especially for making forward-looking decisions regarding value creation (Spieth and Schneider 2016), like a change in distribution channels, target customer groups or the overall positioning of the company in the market, the capability to scan the organizational environment and accumulate and filter this information is of essential importance. The seizing capability then bridges external and internal knowledge, and outlines how these opportunities and threats are addressed and exploited (Teece 2018). Further, being strong in seizing may also profit the value proposition dimension of BMI. When firms are increasingly open to the concerns of their customers, they may put these into a broader relation and for example introduce a wider range of products and services more quickly. We hypothesize:

H1a

Stronger sensing and seizing capabilities lead to more business model innovation activities in family firms.

BMs today cannot be static (Demil and Lecocq 2010) or be fully anticipated in advance. Rather, they must be learned over time through experimentation and reflection (McGrath 2010). So one of the main challenges in BMI is that it requires extensive commitment to experimentation and learning (Baden-Fuller and Morgan 2010; Chesbrough 2010). It demands for a flexible and dynamic business practice where firms have to constantly reflect on obtained information to be able to remodel their businesses and take lessons from the past (Crossan and Berdrow 2003). Thus, recognizing when processes have become outdated is an essential capability that helps a firm to introduce system wide changes like a re-definition or innovation of its BM. The reflecting capability includes regular critical considerations of success factors and analyses of errors to find out their causes. This is especially needed for the value creation dimension of BMI (Spieth and Schneider 2016). Also for value proposition and value capturing innovation it is important to enable the organization and their employees to learn quickly by reflecting and thereupon build strategic assets (Teece 2007). Family firms, in this regard, stand out as being particularly rich in tradition (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007, 2011; Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2014) and should constantly seek strategic renewal. De Massis et al. (2016) employed in their qualitative study a product innovation strategy based on tradition. They highlight the importance of an underlying reflecting capability for internalizing potentially useful internal knowledge from the past, and reinterpret and combine this knowledge to generate new product functionalities. Hence, we hypothesize:

H1b

Stronger reflecting capabilities lead to more business model innovation activities in family firms.

For BMI, especially the transforming capability is of substantial importance. BMI demands for a certain openness to gain and internalize new knowledge from other firms and from the market, and an adjustment of the resource configuration to support these activities (Wu et al. 2012). In an in-depth case study Riviere et al. (2018) recently highlighted the particular importance of transforming capabilities. By creating changes to the firm’s business structure, they are fundamental for capturing and integrating insight across the firm (Riviere et al. 2018). Especially at an implementation stage of new BMs, organizational realignment is required (Sosna et al. 2010). Decision makers need to mobilize their resources and adjust organizational structures to promote the necessary adaptation. The transforming capability hereby leads to a flexible redeployment of resources, both from employees and financially, throughout the firm. It helps a firm to consistently see through the change projects, even when unforeseen interruptions occur, and to put them into practice alongside the daily business. Teece (2018) already highlighted the very significance of transforming by indicating that the strength of a firm’s capabilities is implicated when BM changes are translated into organizational transformation. One of the great challenges hereby is that BMI activities are internally quite difficult to manage because people tend to abandon creative and novel actions in favor of familiar routines (Cavagnou 2011). BMI thus demands for strong leadership tasks (Chesbrough 2010) that encourages on employees to be committed and willing to work in a flexible environment (Smith et al. 2010). Strong transforming capabilities support a firm in these challenges and help to solve the dilemma of well-established routines vs. important flexibility (Teece 2018). Transforming capabilities refer to putting decisions for BMI into practice by implementing and reconfiguring the required routines, providing the infrastructure and ensuring that the workforce has the necessary skills (Kump et al. 2018). Transforming is thus the actual realization of strategic renewal within the organization. It is needed for changing the mechanisms and logic of how costs arise and revenues are generated, and for adjusting the core competencies and internal value creation processes of the company. In the realm of the desire for long-term survival and growth, having strong transforming capabilities might be especially essential for family firms. We thus hypothesize:

H1c

Stronger transforming capabilities lead to more business model innovation activities in family firms.

In family firms, the close overlap between family and firm and the associated family goals and values may be either an advantage or a disadvantage for the translation of dynamic sensing and seizing capabilities into BMI. One of the main goals of owning families is to preserve their firm’s heritage. They develop a long-term strategy that aims at renewing family bonds by dynastic successions (Barros et al. 2016). The SEW consideration to pursue the aim for renewing family bonds in family firms may strengthen the positive effect of sensing and seizing capabilities on the identification of technological possibilities (Fitz-Koch and Nordqvist 2017) as part of BMI. Further, family firms internally establish strong relationships with their employees who usually reside very long within the company (Berrone et al. 2012; Bammens et al. 2015). Thus, the employees derive a special, externally oriented tacit knowledge and know for example about best practices in the market and competitor’s projects. If family managers are motivated to focus on the long-term establishment of these relationships and bind such social ties, they can make better use of their abilities because the employees’ tacit knowledge allows them to recognize more quickly what information they need and utilize it accordingly. Resulting, the effect of sensing and seizing market developments on BMI might be strengthened. BMI may easier be implemented because it demands for a high level of market expertise (Baden-Fuller and Morgan 2010; Teece 2010; Wirtz et al. 2010) and the ability to recognize momentous trends (Teece 2007; Kump et al. 2018), which can only come into effect upon the family’s willingness to engage in strong relationships with the typically long-term employed workforce. Nevertheless, this unique family firm attribute of binding social ties can also be extended to external factors, e.g. by cultivating and nurturing strong relationships with long-time suppliers, vendors or clients (Berrone et al. 2012). These result in feelings of relational trust (Fitz-Koch and Nordqvist 2017) that ultimately lead to special access to important networks featuring insider information and knowledge (Cennamo et al. 2012), and higher awareness of demands in the firm’s environment. The relationship between sensing and seizing capabilities and BMI is therefore very likely to be strengthened by this family specific social dimension. In contrast, if there is no motivation for binding strong social ties, fluctuation among the workforce might be higher and tacit knowledge goes missing. The family’s focus on relationship building both internally and externally does not necessarily have to encourage the translation of an ability to recognize trends into an enhancement of BMI, but may also leave the firm more prone to rigidity (Capaldo 2007). In family firms, procedures and assets are usually long established and employees’ need to be open for establishing sensing and seizing capabilities. But due to their risk-aversion (Block 2012; Chrisman and Patel 2012; De Massis et al. 2013), family members often refuse to change their firms’ path and do not feel compelled to act (Beckhard and Dyer 1983), especially if they proved to be successful in the past. Therefore, family influence can also impede the translation of a firm’s sensing and seizing capabilities into novel BMI activities (Block et al. 2013; Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2014), and might thus also have a negative side. Researchers find family firms to be driven by enhanced concerns for survivability and preference for the status quo and tradition (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007, 2018; Carnes and Ireland 2013; Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2014). In addition, their typical desire to stay in control may result in financial constraints that can cause the pursuance of conservative strategies. Especially because all change projects demand for a strong commitment by management and workforce (Baden-Fuller and Morgan 2010; Sosna et al. 2010; Spieth and Schneider 2016), the family needs to be willing to flexibly make use of their financial resources for turning the capabilities of recognizing market developments into BMI. If this is not the case, family influence and a potentially accompanied market caution may weaken the relationship between the firm’s sensing and seizing capabilities and BM changes that can be expensive and associated with external financing (Schilke 2014). As outlined, there are arguments for both a positive and a negative moderating influence. We therefore hypothesize:

H2a

Socioemotional wealth positively and significantly moderates the relationship between the sensing and seizing capabilities of a family firm and its business model innovation in the sense that the higher the level of socioemotional wealth is, the stronger is the positive effect of sensing and seizing on BMI.

H2b

Socioemotional wealth negatively and significantly moderates the relationship between the sensing and seizing capabilities of a family firm and its business model innovation in the sense that the higher the level of socioemotional wealth is, the stronger is the negative effect of sensing and seizing on BMI.

An inherently unique aspect of family firms is the close identification of family members with their firm (Casprini et al. 2017; Suess-Reyes 2017), which is often considered as an extension of the family itself. Family members desire to proudly represent a successful company. Usually, they are well considered and engaged about the image formed by their decisions and the consequential entrepreneurial actions (Berrone et al. 2010), for example scope and direction of their business. Hence, it is very likely that such desire strengthens the relationship between a firm’s capabilities to regularly reflect the success factors of their current BM, analyze errors, past mistakes and their causes (Teece 2007), and the consequential entrepreneurial actions like scope and direction of a BMI. Further, also emotions play an important role in a family firm’s motivation and decision to translate their capabilities into effect (Ashforth and Humphrey 1995). Due to long history and shared experiences the borders between family and firm are blurred (Bammens et al. 2015) and such close overlap can lead to an emotional attachment by the owning family (Berrone et al. 2012). Just as with the identification, these feelings of relatedness and attachment result in family members’ desire to protect their welfare and positive self-concept, and ultimately lead the families’ main decision-makers to engage in the translation of capabilities to reflect on past processes into BMI projects. Additionally, this relationship might be acted upon by the strong internal relations that are typically built within family firms, both with their long-employed workforce (Bammens et al. 2015; Rothaermel and Hess 2007) and top management (Kammerlander and Ganter 2015; Röd 2016). When the family is motivated to build these relationships and work on the entailing entrepreneurial knowledge about internal problems and weak points (Carr and Ring 2017; Calabró et al. 2016), the novel combination of traditional resources and assets can be approved in pioneering ways and their implementation into BMI may be enhanced, as errors from past projects and processes can be internalized and more easily avoided. However, some studies state that family firms are also underlying certain locked-in effects (Capaldo 2007; Maurer and Ebers 2006). Just as a lack of motivation of the family to encourage their employees to translate strong external sensing and seizing capabilities into the pursuance of BMI is negative, it may also impede the ability to convert knowledge learned from past projects into BMI. In family firms, the workforce may be stuck to old structures and functioning (Capaldo 2007). Over time, these incumbent firms become blind to necessary change and adaptation because structures are entrenched (König et al. 2014). If the family is not willing to overcome their status as rather incremental innovators (Carnes and Ireland 2013) and actively use their power to translate capabilities of constant reflection of internal processes and work structures (Crossan and Berdrow 2003) into BMI activities, the family’s’ SEW endowment might be debilitating for the underlying relationship between reflecting capabilities and BMI. Ultimately, considering both positive and negative arguments, we hypothesize:

H3a

Socioemotional wealth positively and significantly moderates the relationship between the reflecting capabilities of a family firm and its business model innovation in the sense that the higher the level of socioemotional wealth is, the stronger is the positive effect of reflecting on BMI.

H3b

Socioemotional wealth negatively and significantly moderates the relationship between the reflecting capabilities of a family firm and its business model innovation in the sense that the higher the level of socioemotional wealth is, the stronger is the negative effect of reflecting on BMI.

There are numerous arguments both for a positive and for a negative family influence on the relationship between a firm’s transforming capabilities and its BMI. In family firms, the commitment to hand a successful business over to the next generation may motivate the owning family to focus on business growth (Eddleston et al. 2008). Hereby, they try to preserve the maintenance of family values through the firm. With such a long-term orientation, family owners can focus more on ensuring that their transforming capabilities of flexible resource allocation within the firm lead to more sophisticated BMI pursuance. Nevertheless, a BMI’s earnings may take several years to produce tangible returns, even if consistently pursued (Urbinati et al. 2017; Bucherer et al. 2012). Under such long-term orientation, family owners are less pressurized for rapid performance and thus motivated to flexibly use their financial resources and transform internal structures towards BMI. Investments and high costs of transforming the organizational structure towards facilitating and supporting projects like BMI are not evaluated on a short-term basis (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007). Since in family firms, family members often provide management positions as major agents of change (Tagiuri and Davis 1996), their strong motivation to quickly decide upon the necessary reallocation of resources to implement planned BMI changes without great bureaucratic effort (Chesbrough 2010; Bucherer et al. 2012) is fundamental. As a strategic endeavor, deciding upon organizational restructuration and the implementation of plans for changing, reviewing and renewing a firm’s BM demands for a strong conviction and long-term commitment by both employees and top management (Baden-Fuller and Morgan 2010; Sosna et al. 2010; Spieth and Schneider 2016). By clearly defined responsibilities, family firm managers can quickly decide upon the necessary reallocation of resources to implement planned BMI changes without great bureaucratic effort. Also Bogers et al. (2015) empirically show that owning families play the key role in balancing internal and external influences. This balance affects the scope and complexity of employing transforming capabilities for BMI. Further, owner-managers internally aim to engage all employees in an involving working environment (Bammens et al. 2015, Calabrò et al. 2018). Consequently, if the focus is on developing an inspirational workforce, transforming capabilities are more likely to positively influence BMI and lead to higher levels of entrepreneurship (Miller et al. 2008). Family firms are especially suited to develop such leadership style that is indispensable for transforming capabilities into impacting BMI (Chesbrough 2010; Smith et al. 2010). Additionally, the specific long-term employment of the workforce (Bammens et al. 2015) secures that this positive effect is not only temporary but can be established in the long run. On the other side again, family firms can in contrast also be resistant to change due to the emotional attachment of family managers to their firm’s traditional strategies, and their strong identification with the family firm and family control (Nieto et al. 2013; Beckhard and Dyer 1983). Family managers often seek to maintain the reputation in their respective communities (Berrone et al. 2010; Sharma and Manikutty 2005), are subject to institutional expectations or simply try to justify their dominant role (Berrone et al. 2010; Sharma and Manikutty 2005). Research has suggested that this may be detrimental to family firms, as it can cause family members to feel locked into and dependent upon the firm resulting in being stagnant to major internal changes (Schulze et al. 2002). As a result, family managers are less willing and hesitate to engage in the successful transportation of their transforming capabilities into BMI, ultimately resulting in the adoption of industry-compliant strategies like generally accepted BMs (Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2014). Furthermore, the overlap of family wealth and firm equity leads to family managers being more reluctant to debt and external equity financing (Steijvers and Voordeckers 2009) and they may avoid taking risky decisions and hinder necessary but venturesome changes in the organizational structure. In this way, the direction of transforming capabilities towards an encouragement of potentially disruptive adjustments in the BM is weakened—even if these could anticipate their financial success (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2018). As outlined, there are both positive and negative arguments for the moderating role of family influence on the relationship between transforming capabilities and BMI. Hence, we hypothesize:

H4a

Socioemotional wealth positively and significantly moderates the relationship between the transforming capabilities of a family firm and its business model innovation in the sense that the higher the level of socioemotional wealth is, the stronger is the positive effect of transforming on BMI.

H4b

Socioemotional wealth negatively and significantly moderates the relationship between the transforming capabilities of a family firm and its business model innovation in the sense that the higher the level of socioemotional wealth is, the stronger is the negative effect of transforming on BMI.

4 Methodology

4.1 Sample and procedure

Primary data were collected through mail surveys referring to the last 3 years of company activity. We received access to a hand-collected data set of 3714 personal Email addresses via university mailing lists and several German family firm federations. Emails were sent directly to family CEO’s, family top managers and well-informed family board members. Respondents at this level of operation were expected to be well informed about the firm’s BMI strategies, which was a prerequisite of ensuring the suitability of the answers (Covin and Slevin 1989). Data collection took place between December 2017 and March 2018. Following the initial mailing of surveys, a reminder E-mail was sent out in January 2018 to increase the response rate. Family firm owners from 154 companies returned usable questionnaires, resulting in an overall response rate of 4,16 percent from all firms that initially received the survey. This response rate is usual for a study targeting for primary data and confidential topics from top management in family firms (Zellweger, Nason and Nordqvist 2012). We received answers from 69 CEOs, 37 managers, and 25 advisory board members, 14 members of the family council and 9 from other functions. The respondents were ensured confidentiality and offered a summary of the results. Our final dataset consists of entries from 4 small-sized (10-50 employees), 39 medium-sized (50–249 employees) and 111 large (more than 250 employees) family firms. In more than 80% of the final companies the family owned 100% of the shares of their respective firms. In 82 firms, two and more generations were involved in the management and only one generation was involved in 72 firms. Lastly, in order to test for non-response bias we followed the approach of Armstrong and Overton (1977) and compared early and late respondents utilizing t-tests. The approach is based on the assumption that the manner of answering questionnaires of late respondents is similar to non-respondents. The results showed no significant difference between the two groups and our findings thus mitigate the concerns for non-response bias.

4.2 Measures

4.2.1 Business model innovation

Since previous studies on business model innovation were mainly qualitative, literature demanded future research to deepen current findings quantitatively (Schneider and Spieth, 2013). Recently, Spieth and Schneider (2016) developed and empirically validated a first quantitative measurement model based on a study among 200 German firms. Such measurement set a clear focus on the aspect of change during a BMI, for example a change in the target customer groups, the range of products and services, the positioning of the company in the market, and the core competencies and resources of the company (Spieth and Schneider 2016). Accordingly, our dependent variable BMI contains eight items that capture a value offering dimension, a value creation dimension and the revenue model, which explains how a firm generates profits. All items were taken from Spieth and Schneider’s (2016) item catalogue. The adequacy of the items was tested and confirmed in a principal component analysis (PCA; KMO measure of 0.700, significant Bartlett’s test (p < 0.001). The variable was assessed with a 6-point Likert-type scale (Nunnally and Bernstein 1994) and its internal consistency was α = 0.890.

4.2.2 Dynamic capabilities

There are many attempts to operationalize our first independent variable dynamic capabilities but so far research does not agree upon a unitary measuring instrument. Therefore Kump et al. (2018) have subjected the item catalogues of total 72 articles from peer-reviewed journals to a multi-stage development process based on Teece (2007) and empirically validated 19 items for seizing, sensing (divided into reflection and search) and transforming. In order to evaluate the appropriateness of using the 19 items of the DC construct, a PCA was conducted. The adequacy of the data was shown by a KMO measure of .938, and a significant Bartlett’s test (p < 0.001). The results revealed three factors: sensing and seizing of opportunities and market situations and reacting quickly, reflecting and learning of the organization’s errors and past processes, and finally, transforming competences into new product functionalities and innovations. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scales were α = 0.921 (sensing and seizing), α = 0.897 (reflection) and α = 0.920 (transforming).

4.2.3 Socioemotional wealth

For measuring our moderator variable socioemotional wealth, we used the multi-dimensional FIBER-Scale from Berrone et al. (2012), which originally includes five dimensions: (1) F: Family control and influence; (2) I: Family members’ identification with the firm; (3) B: Binding social ties; (4) E: Emotional attachment; and (5) R: Renewal of family bonds to the firm through dynastic succession, and claims to measure the fundamental characteristics of family firms that are said to emerge from the interaction between family and firm. These family-firm specific characteristics considerably affect the firm’s strategic behavior with a reciprocal relationship existing between economic and non-economic value created through the combination of the two systems (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007). The only exception we made regards the F-dimension, which in a recent empirical test of the FIBER scale from Hauck et al. (2016) was particularly criticized and could not be clearly reproduced in their statistical validation among a sample of 216 family-owned and -run businesses. In addition, Family Control and Influence showed overlaps with Renewal of Family Bonds through Dynastic Succession (R; Chua et al. 2015), e.g.’Preservation of family control and independence are important goals for my family business’ (Berrone et al. 2012, p. 266). Hauck et al. (2016) hence argue that it lacks a sufficient conceptual separation between present and prospective SEW (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2015). However, since current family influence is also regarded as a prerequisite for the formation of current SEW (Berrone et al. 2012) and thus remains a necessary, albeit not sufficient, condition (Chrisman et al. 2005) for SEW, Hauck et al. (2016) suggest not to abandon this aspect completely. Therefore, the items regarding family control and influence resemble a components-of-involvement concept and should be measured directly instead of using a Likert-scale. In this study we follow Audretsch et al. (2013) and Hauck et al. (2016) and use family management as the share of family members in the top management team. The remaining four dimensions showed adequate internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of α = 0.882.

4.2.4 Control variables

In our model, we controlled for several variables, which have been related to BMI in past research. First, we included firm size (logarithm of the number of employees) and firm age (logarithm of years since foundation), because larger firms are said to accumulate more slack resources that encourage innovation (Zahra 2005) but could also suffer under inertia due to rigid structures (Chesbrough 2010). Young and small firms on the other hand could benefit from less established structures and a stronger corporate orientation (Rauch et al. 2009) but may have fewer resources at their disposal. For our family firm definition, we further controlled for the percentage of family members in the management. Next, we controlled for generational involvement (two or more generations involved), which may also influence BMI given that founder-centered firms often lose their innovative momentum until the second or third generations join the firm and contribute to an increased knowledge heterogeneity (Zahra 2005; Zellweger et al. 2012). Also, the younger generation is said to be more prone to using state-of-the-art technology (Becker et al. 2012), which is important for spotting BMI opportunities (Liao et al. 2009). Finally, theory suggests controlling for industry types because the organizational context can play an important role in understanding the entrepreneurial behavior of firms (Zahra 2007). It can be assumed that industries that are under particular pressure to innovate will pursue more BMIs than others. We grouped the industries regarding the United Nations industry classification system ISIC (International Standard Industrial Classification).

4.3 Data analysis and results

We are aware of threats regarding common method bias (CMB) since the data collected for dependent and independent variables were from the same respondents. First, we followed a careful designing procedure of our study in order to minimize the influence of CMB (Podsakoff et al. 2003; William et al. 2010). Second, we used statistical remedies in order to control the impact of CMB after data collection. The Harman one-factor analysis (Harman 1967) is the most common test that is carried out by the researchers to examine the CMB in their studies (Tehseen et al. 2017), even though it only provides information regarding the absence or presence of CMB but cannot control or correct it if present in a study. The purpose of this post hoc procedure is to check whether a single factor is accountable for variance in the data (Chang et al. 2010), which would indicate the presence of CMB. Test results revealed that only 28.90% of the variance is explained by one factor. Since this is less than 50%, no single factor accounts for majority of the covariance. This means CMB was not a problem in our study (Chang et al. 2010).

Having checked this important issue, we examined our proposed hypotheses in a series of multiple regression analyses with BMI as our dependent variable. We centered the independent and moderator variables before creating the interaction effects. We entered all independent and interaction variables in a stepwise approach (Hair et al. 2009). The results are portrayed in Table 2. In order to assess the robustness of our results, we conducted a median split of SEW and performed a one-way ANOVA to assess the effects of SEW on the different dynamic capabilities. SEW was divided into high (higher than median value) and low (lower than median value). There were no outliers, according to inspection with a box-plot, and there was homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test, p > 0.05). Table 1 provides an overview of the bivariate correlations between the variables used in this study. The magnitudes were modest, with the highest being 0.724. Bivariate correlations range from − 0.383 to 0.724. As expected, the highest correlations were among the DC dimensions, which belong to one construct, and matched the correlations of the original scale developed by Kump et al. (2018). In order to statistically test for multicollinearity, we checked the coefficient outputs, which indicated that multicollinearity was not an issue in our study (for independent variables: Variance Inflation Factor VIF = 2.199, tolerance = 0.455 for dynamic sensing and seizing capabilities; VIF = 2.792, tolerance = 0.370 for dynamic reflecting capabilities; VIF = 2.050, tolerance = 0.488 for dynamic transforming capabilities. For interaction variables: VIF = 2.677, tolerance = 0.389 for SEW × sensing seizing; VIF = 3.228, tolerance = 0.310 for SEW × reflecting, VIF = 2.570, tolerance 0.389 for SEW × transforming,). According to Urban and Mayerl (2006) the tolerance value should not be below 0.25, and the VIF value should not exceed 5.0.

Table 2 then shows the results of the regression analyses with BMI as dependent variable. Model 1 includes only the control variables and explains 17.9% of variance in the dependent variable. Model 2 includes the first independent variable dynamic sensing and seizing capabilities and explains an additional 15.4% of variance. Model 3 includes dynamic reflecting capabilities and explains an additional 1.9% of variance. In Model 4, the last independent variable, dynamic transforming capabilities, is added, the model then explains 35.7% of variance. Our first hypotheses proposed that sensing and seizing capabilities (H1a), reflecting capabilities (H1b) and transforming capabilities (H1c) would positively influence a family firm’s BMI. Sensing and seizing capabilities (H1a) were significantly positively related to BMI (ß = 0.176; p < 0.05), even though not as strongly as transforming capabilities. Nevertheless, H1a was supported. Reflecting capabilities were not significantly related to BMI (ß = 0.134), thus H1b could not be supported. Lastly, the transforming dimension was very significantly and positively related to BMI (ß = 0.398; p < 0.05). Hence, H1c was supported.

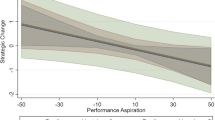

In Model 5 we introduced our moderator variable SEW, and lastly in step 4, we included in model 6 our first interaction variable separately, in model 7 the second one, and in model 8 the last interaction variable, SEW × transforming. The results show that out of the three interaction terms only one was significant. First, for investigating the relationship between sensing and seizing capabilities and BMI, no moderating effect of SEW could to be found [ß = 0.132, (ns)]. Therefore, both H2a and H2b could not be supported. Next, in support of hypothesis H3a, a positive moderating effect of SEW on the relationship between reflecting capabilities and BMI was found (ß = 0.355; p < 0.05). We interpreted the significant positive interaction by plotting the result. The results show that if the family puts a strong focus on noneconomic goals, it is more likely that also the firm’s capabilities to reflect on internal success factors, errors and processes positively influence and enhance the pursuance of a BMI. Consequently, H3b could not be supported.

Lastly, hypotheses H4a and H4c could both not be supported since no moderating effect of SEW on the relationship between transforming capabilities and BMI could be shown [ß = − 0.031, (ns)]. Nevertheless, the result was negative, which, however, indicates that if the family’s noneconomic goals were high, it is more likely that the transforming capabilities of the firm, meaning the actual implementation of changes and consistent pursuance of decisions, negatively influence and thus decline the pursuance of a BMI.

The robustness test results from an ANOVA comparing family firms with high (M = 4.97, SD = 0.61) or low (M = 4.03, SD = 0.99) degrees of SEW showed that the strength of the sensing and seizing capabilities (F (1,152) = 16,65, p < 0.001), reflecting capabilities (F (1,152) = 23,83, p < 0.001), and transforming capabilities (F (1,152) = 17,72, p < 0.001) differed statistically significant for the different levels of SEW. Lastly, although not part of our hypotheses, we found the transport and storage, agriculture, building and construction, trade, and the information and communication industries strongly to be positive supporting environments for BMI activities. We will discuss all findings below (Please see Fig. 1).

5 Discussion

In this paper we explored to what extent dynamic capabilities facilitate BMI in the context of family firms (Teece 2007) and how this relationship is moderated by SEW. Investigating this in the context of family firms is particularly interesting as the translation of DCs into BMI is a choice associated with the attitude of the family to contribute to organizational effectiveness—even when employing these capabilities is personally costly (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2018). In doing so, we found support for the importance of strong sensing and seizing and strong transforming capabilities for BMI as well as a positive moderating effect of SEW on the relationship between reflecting capabilities and BMI in family firms.

We show that sensing and seizing capabilities are important antecedents for BMI. These capabilities are said to help for an early recognition of technological possibilities (Teece 2007; Kump et al. 2018) and to develop a profound knowledge of competitors’ activities by systematically scanning the environment. They help for the identification of target market segments, changing customer needs and customer innovations. This is especially interesting in the context of family firms since they are said to focus more on themselves than on others due to their typically strong embedment (Aldrich and Cliff 2003). Overall, this is in line with initial findings from organizational learning literature that emphasize the importance of trial-and-error learning for BMI (Sosna et al. 2010) in a way that it requires managers to experiment and discover what can work and what fails, incorporating new knowledge and new skills into structures and procedures (Baden-Fuller and Stopford 1994). Family firms need to actively acquire sensing and seizing capabilities and focus on the outside-view of the firm.

Family firms that establish new value-enhancing asset combinations and decentralize their decisions can rapidly implement BMI. We hereby demonstrate that although family firms are known for being rather reluctant to decentralization (Martin et al. 2016), they need to focus on acquiring important transforming capabilities. By this, we confirm the findings from Achtenhagen et al. (2013) who state that one critical capability underlying BMI is an orientation towards experimenting with and exploiting new business opportunities, thus developing a rather forward-oriented vision. BMI demands for the establishment of capabilities that intent for change in order to adapt to the firm’s environment (Zahra et al. 2006; Zott 2003). For advancing BMI, openness for new and proactive ways of value creation and value capturing is most important. Family firms must therefore continuously strive against the rigidity that is often associated with their particular long-term orientation. In family firms, decisions are often distributed among a few decision-makers, but we can show that an active focus on a continuous alignment and realignment of tangible and intangible assets becomes apparent in an improved ability for BMI.

While more reflecting capabilities do not seem to facilitate BMI in our study, Teece (2018) notes that a successful implementation of BMI stems from management’s asset orchestration, architectural design, and learning functions, which are partly assignable to reflecting capabilities. One reason could be that family firms already excel in their reflecting capabilities. Several studies point towards the notion that capabilities of internal reflection on existing success factors and errors, or learning from the past might be high in family firms (Cabrera-Suárez et al. 2001; Eisenhardt and Santos 2002). While relying on these reflected internal processes seems important at first sight, an alternative explanation for its insignificance in the studied context might lie in its retentive, rather past-oriented nature. As outlined, different rules seem to apply for BMI in such a way that previously used processes and success factors do no longer matter. On the contrary, BMI seems to require firms to gather external knowledge, e.g. on customers, technologies, other BMs or best practices, build plans for changes accordingly, and implement these flexibly throughout the firm.

If the family firm wants to leverage the best of the firm’s reflecting capabilities for BMI, the influence of a high SEW is needed. As aforementioned, family managers are motivated by non-financial goals and values that go far beyond passing on merely a pile of bricks or a plain product portfolio. Entrepreneurial family managers have the inner desire to preserve their company for future generations. They intend to pass on their underlying values and ideas (Berrone et al. 2012) as entrepreneurial heritage. In order to survive in the long run, it requires the ability to reflect, and to establish family specific knowledge. This includes awareness about what the firm is good at, underlying critical success factors, strengths but also mistakes that have been made in the past. The family aims at creating transgenerational awareness for the establishment of reinvention skills as a company instead of resting on past successes. Such internal tacit knowledge resonates in the dynamic reflecting capability of a family firm, and is one of its distinguishing features from non-family firms.

When the family at the same time influences the leverage of reflecting capabilities as well as transforming capabilities for BMI, their nonfinancial goals negatively moderate the ability to convert transforming capabilities into BMI. Such phenomenon indicates the trade-off between reflecting and transforming capabilities that family firms face. This trade-off builds the core challenge of proper resource allocation for BMI in family firms. A family firm’s SEW seems to have a “dark side”, which comes to light when it weakens the relationship of transforming capabilities to BMI. Transforming capabilities somehow conflict with SEW because transforming means decentralization of decisions, loss of power, keeping resources fluid, etc. They entail organizational and personnel restructuring, which is also needed for BMI, and often include a change in the very processes that have been optimized to make a company successful and profitable. As such, they can lead to a loss of power for a dominant family manager, and may thus be considered as a risky step away from well-known success (Teece 2018). This clashes with the emotional attachment of family managers to a firm’s traditional strategies (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007), their strong identification with the firm (Berrone et al. 2010), and their desire for a dominant family role (Berrone et al. 2010; Sharma and Manikutty 2005). Family managers may on the one hand recognize the firm’s success but on the other hand, due to these changes and restructuring initiatives, feel that they do not understand their own firm anymore. The main difficulty for family firm owner managers is to target the influence of their non-financial values and to find the right balance between exploiting and compensating the distinct capabilities.

This paper contributes to the growing literature on entrepreneurship and especially BMI (Foss and Saebi 2017; Schneider and Spieth 2013; Hienerth et al. 2011) in the context of family firms in a twofold way. First, we add to the scarce empirical evidence on which DCs firms today need in order to adapt their BMs in a disruptive environment (Cozzolino et al. 2018; Foss and Saebi 2017). Traditional BM research builds on the resource-based view (Barney 1991), which deals with methods to develop difficult to replicate resources and assets that increase the value of BMs (Amit and Zott 2012). Our analysis, however, is centered at the analysis of critical capabilities to support BMI for sustained value creation (Teece 2007). We hereby follow some recent calls that emphasize the need for a better understanding of DCs as internal facilitators of BMI (Foss and Saebi 2017, 2018; Teece 2018; Cozzolino et al. 2018). Albeit literature has recognized this need for BMI, empirical research on the facilitators of these changes is rare (Mezger 2014; Lambert and Davidson 2013; McGrath 2010; Teece 2010). So far, the relationship has only conceptually been investigated (Foss and Saebi 2018; Mezger 2014; Amit and Zott 2012; Teece 2010) or explored in individual case studies only (Hacklin et al. 2018). Little generalizable insights are offered, especially compared to the well-established literature on product, process and service innovation (Mazzelli et al. 2018; Kraus et al. 2012). We respond to such demand and ultimately add to BM research by quantitatively measuring the single components of DCs separately. The fine-grained results identify sensing and seizing, and transforming capabilities as crucial conversion factors for BMI. Second, we follow several researchers to deepen our knowledge on the explicit effects of family influence and noneconomic goals when investigating dynamic entrepreneurial BMI activities (Calabrò et al. 2018; Urbinati et al. 2017; Sciascia and Bettinelli 2016). We hereby enhance our understanding of the moderating role of family influence (Zahra et al. 2007). As outlined before, the SEW construct is anchored at a deep psychological level among family owners and may vary between different family managers regarding their motivations and goals (Berrone et al. 2010). Although a certain SEW endowment is characteristic for family firms (Martínez-Romero and Rojo-Ramírez 2017), there can be substantial differences from one family firm to another (Berrone et al. 2012). Family managers may hence assess BMI in distinctive ways, which has yet only scarcely been researched. Within our family firm sample, we found differences between family firms with high and with low SEW, meaning that firms with high levels of SEW sense and seize, reflect and transform significantly different than those with low SEW. Nevertheless, these differences did not moderate the relationship between DCs and BMI. But, as shown, certain trends regarding the endowment of SEW and its role for entrepreneurial processes can be inferred. By deriving and testing our hypotheses both positively and negatively, we were able to reveal a trade-off between reflecting and transforming capabilities and their role on BMI, which indicates a “dark side of SEW”. In doing so, we extend current literature that states the importance of testing the direction of family influence in a fine-grained manner (Calabrò et al. 2018; Zahra 2007).

Our study also offers some practical implications because BMI is considered essential to revitalize family firms (Eddleston et al. 2008; Teece 2018) and ensure long-term success and survival (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010; Sosna et al. 2010; Wirtz et al. 2010). BMI requires firms to significantly reconfigure their organizational structure, resource base, and value chain. Therefore, understanding and determining which resources are required to implement a new BM, acquiring these, and consequently replacing an existing set of abilities is a potentially valuable tool for family firm managers. For family firms, it is especially important to actively work on the decentralization of decisions, since especially sensing and seizing, and transforming are capabilities that demand for a proactive leadership support. Especially family owner managers need to find a balance between their focus on transforming capabilities and their internal reflection, because they seem to build a trade-off when acted upon by family norms and values. Family members can on the one hand bring in an internal view with tacit knowledge reflecting on previous established success factors, which may work on the relationship between the firm’s capabilities and BMI strategy. But on the other hand, the family may impede the firm from pursuing the necessary transforming activities for BMI. Hence, family managers should focus on providing an organizational structure that allows for a flexible redeployment of resources and their employees within the firm. Ultimately, managers have to be aware that whereas few of these routines develop accidentally, most of them require patient investments and foresight, and need to be proactively acquired and developed. Managers need to systematically reflect whether they pay enough attention to establishing and exploiting these capabilities in order to achieve invaluable BMI on a sustainable basis.

6 Limitations and directions for future research

Like every empirical paper, our study has limitations that need to be acknowledged, some of which suggest important avenues for future research. First, our data are cross-sectional in nature, and, therefore, we cannot infer causality from our findings. To overcome this issue, we have been very cautious in the wording and avoided mentioning causal inferences. But, cross-sectional designs are common in family firm research due to the challenge of obtaining primary data from privately held family firms. Second, although this dataset includes a variety of firms representing a broad range of industries, care should be exercised in generalizing the results. Two out of our three moderation hypotheses are not significant which may ale be due to our specific sample characteristics. We have measured all variables within the context of family firms. The results indicate that the measured relationship between DCs and BMI is context-dependent. We believe that future studies should scrutinize our findings in non-family firm settings, possibly also incorporating a greater number of different countries and time periods in order to ensure an even higher level of variance of environmental dynamism in the dataset, which may ultimately lead to more significant results. Regarding the intra-family-firm sample, this study further supports research that points up the heterogeneity of family firms in the emphasis they place on SEW (Chrisman and Patel 2012; Block et al. 2013). Given that SEW appears to increase over generations, future research may investigate whether our results vary when a firm changes status from founder to when family or generations evolve. Third, our study places entrepreneurs and managers at the centered of the process. Therefore, we examine the manner envisioned and deemed appropriate by the firm’s principal decision-maker. We are aware of the threat of common method bias (Podsakoff and Organ 1986) in this regard, which we tried to mitigate by calculating a Harman one-factor analysis (Harman 1967) that luckily did not indicate any common method bias issues. Also, using a single source key informant is common in researching firm capabilities in order to obtain required data on internal processes (Capron and Mitchell 2009; Danneels 2008; Gruber et al. 2010). Next, like most quantitative studies, we tested only a few control variables and did not add any performance measures like ROI or net worth since these are especially hard to access in the context of family firms. Nevertheless, future research may include such variables because performance can have supporting or suppressive effects on strategic activities like BMI (Chrisman and Patel 2012). Lastly, a principal component analysis of our main variables showed different dimensions for measuring DCs than the ones used in previous studies (Teece 2007). Regardless the specific family-firm context, the DC-scale still lacks a thorough development and validation and future research should establish an overall validated scale for DCs. Further, there is research indicating that DCs may partly be dependent on the organizational flexibility that comes from initial BM choices such as whether to outsource the manufacture of a new product or build a factory (Teece 2018), thus indicating the possibility of a reciprocal relationship. These are interesting avenues that may be addressed in future research. To date, the empirical evidence was too little for consequently and comprehensibly deriving corresponding hypotheses in this study. Nevertheless, our detailed measurement leads to novel and interesting insights that allows drawing conclusions of the initial sources of influence in enhancing BMI. While these relationships seemed to be understood at a theoretical level, there is a need for future empirical work to flesh out the details. For example, showing that only transforming and sensing and seizing capabilities enable firms to systematically engage in BMI might lead future researchers to enrich the capability perspective of BMs with organizational antecedents (Danneels 2008) to further derive insights into why some firms are better at BMI than others.

References

Achtenhagen L, Melin L, Naldi L (2013) Dynamics of business models-strategizing, critical capabilities and activities for sustained value creation. Long Range Plan 46:1–25

Aldrich HE, Cliff JE (2003) The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: toward a family embeddedness perspective. J Bus Vent 18:573–596

Amit R, Zott C (2012) Creating value through business model innovation. Sloan Manag Rev 53:41–49

Archibugi D (2017) Blade Runner economics: will innovation lead the economic recovery? Res Policy 46:535–543

Ashforth B, Humphrey R (1995) Emotion in the workplace: a reappraisal. Hum Rel 48:97–125

Audretsch DB, Hülsbeck M, Lehmann EE (2013) Families as active monitors of firm performance. J Fam Bus Strat 4:118–130

Babelytė-Labanauskė K, Nedzinskas S (2017) Dynamic capabilities and their impact on research organizations, R&D and innovation performance. J Modell Manag 12:603–630

Baden-Fuller C, Morgan MS (2010) Business models as models. Long Range Plan 43:156–171

Baden-Fuller C, Stopford JM (1994) Rejuvenating the mature business. Routledge, London

Bammens Y, Notelaers G, Van Gils A (2015) Implications of family business employment for employees’ innovative work involvement. Fam Bus Rev 28:123–144

Barney J (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manag 17:99–120

Barros I, Hernangómez J, Martin-Cruz N (2016) A theoretical model of strategic management of family firms. A dynamic capabilities approach. J Fam Bus Strat 7:149–159

Becker KL, Fleming J, Keijsers W (2012) E-learning: aging workforce versus technology-savvy generation. Educ Plus Train 54:385–400

Berrone P, Cruz C, Gómez-Mejía LR, Larraza-Kintana M (2010) Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: do family-controlled firms pollute less? Admin Sci Quart 55:82–113

Berrone P, Cruz C, Gómez-Mejía LR (2012) Socioemotional wealth in family firms. Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Fam Bus Rev 25:258–279

Bingham C, Heimeriks KH, Schijven M, Gates S (2015) Concurrent learning: how firms develop multiple dynamic capabilities in parallel. Strat Manag J 36:1802–1825

Block J (2012) R&D investments in family and founder firms: an agency perspective. J Bus Vent 27:248–265

Block J, Miller D, Jaskiewicz P, Spiegel F (2013) Economic and technological importance of innovations in large family and founder firms: an analysis of patent data. Fam Bus Rev 26:180–199

Bogers M, Boyd B, Hollensen S (2015) Managing turbulence: business model development in a family-owned airline. Calif Manag Rev 58:41–64

Bowman C, Ambrosini V (2003) How the resource-based and the dynamic capability views of the firm inform corporate-level strategy. Brit J Manag 14:289–303

Brumana M, Minola T, Garrett RP, Digan SP (2017) How do family firms launch new businesses? A developmental perspective on internal corporate venturing in family business. J Small Bus Manag 55:594–613

Bucherer E, Eisert U, Gassmann O (2012) Towards systematic business model innovation: lessons from product innovation management. Crea Innov Manag 2:183–198

Buliga O, Scheiner CW, Voigt KI (2016) Business model innovation and organizational resilience: towards an integrated conceptual framework. J Bus Econ 86:647–670

Cabrera-Suárez K, De Saá-Pérez P, García-Almeida D (2001) The succession process from a resource- and knowledge-based view of the family firm. Fam Bus Rev 14:37–47

Calabrò A, Vecchiarini M, Gast J, Campopiano G, De Massis A, Kraus S (2018) Innovation in family firms: a systematic literature review and guidance for future research. Int J Manag Rev 21:1–32

Capaldo A (2007) Network structure and innovation: the leveraging of a dual network as a distinctive relational capability. Strat Manag J 28:6585–6608

Capron L, Mitchell W (2009) Selection capability: how capability gaps and internal social frictions affect internal and external strategic renewal. Organ Sci 20:294–312

Carnes CM, Ireland RD (2013) Familiness and innovation: resource bundling as the missing link. Entrep Theory Pract 37:1399–1419

Carr JC, Ring JK (2017) Family firm knowledge integration and noneconomic value creation. J Manag Issues 29:30–56

Casadesus-Masanell R, Ricart JE (2010) From strategy to business models and onto tactics. Long Range Plan 43:195–215

Casprini E, De Massis A, Di Minin A, Frattini F, Piccaluga A (2017) How family firms execute open innovation strategies: the Loccioni case. J Know Manag 21:1459–1485

Cavagnou D (2011) A conceptual framework for innovation: an application to human resource management policies in Australia. Innov Manag Policy Pract 13:111–125

Cennamo C, Berrone P, Cruz C, Gómez-Mejía L (2012) Socioemotional wealth and proactive stakeholder engagement: why family-controlled firms care more about their stakeholders. Entrep Theory Pract 36:1153–1173

Chang S, Witteloostuijn A, Eden L (2010) From the editors: common method variance in international business research. J Intern Bus Stud 41:178–184

Chen J, Nadkarni S (2017) It’s about time! CEOs’ temporal dispositions, temporal leadership, and corporate entrepreneurship. Adm Sci Qu 62:31–66

Chesbrough H (2010) Business model innovation: opportunities and barriers. Long Range Plan 43:354–363

Chrisman JJ, Patel PC (2012) Variations in R&D investments of family and nonfamily firms: behavioral agency and myopic loss aversion perspectives. Acad Manag J 55:976–997

Chrisman JJ, Chua JH, Sharma P (2005) Trends and directions in the development of a strategic management theory of the family firm. Entrep Theory Pract 29:555–576

Chrisman JJ, Chua JH, De Massis A, Frattini F, Wright M (2015) The ability and willingness paradox in family firm innovation. J Prod Innov Manag 32:310–318

Christensen CM, Wang D, van Bever D (2013) Consulting on the cusp of disruption. Harv Bus Rev 91:106–114

Chua JH, Chrisman JJ, Sharma P (1999) Defining the family business by behavior. Entrep Theory Pract 23:19–39

Chua JH, Chrisman JJ, De Massis A (2015) A closer look at socioemotional wealth. Its flows, stocks, and prospects for moving forward. Entrep Theory Pract 39:173–182

Classen N, Carree M, Van Gils A, Peters B (2014) Innovation in family and non-family SMEs: an exploratory analysis. Small Bus Econ 42:595–609

Covin JG, Slevin DP (1989) Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strat Manag J 10:75–87

Cozzolino A, Verona G, Rothaermel FT (2018) Unpacking the disruption process: new technology, business models, and incumbent adaptation. J Manag Stud 55:1167–1202

Crossan M, Berdrow I (2003) Organizational learning and strategic renewal. Strat Manag J 24:1087–1105

Danneels E (2008) Organizational antecedents of second-order competences. Strat Manag J 29:519–543

DaSilva CM, Trkman P (2014) Business model: what it is and what it is not. Long Range Plan 47:379–389