Abstract

In current management research, a variety of different activities are summarized under the generic term “nonmarket strategy”. Simultaneously, “sub-categories” of nonmarket strategies such as political or social strategies are treated as isolated activities, making it difficult to realize cross-concept relations or commonalities. This article bundles, maps and critically evaluates the rising number of publications in the field of nonmarket strategy research. Based on an integrative framework, we work up insights that have been developed since Baron’s (Manag Rev 37:47–65, 1995) seminal publication. Doing so, our analysis extends previous studies by including internal and external antecedents that influence the development of nonmarket strategies, by analyzing the impact of nonmarket strategies on firm performance and the possibility of strategy integration, on a national as well as multinational level. Key empirical and conceptual papers are reviewed and major findings, relationships, patterns and contradictions are revealed. By consolidating and synthesizing dispersed knowledge, we identify implications for nonmarket strategy elaboration as well as several directions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

What determines the choice and the design of corporate activities to strategically shape the social, political and legal environment? A large body of literature addresses the question of how organizations attempt to influence their ‘nonmarket environment’. Governmental regulations, legal restrictions, boycotts by activist groups or nongovernmental organizations have a significant impact on the corporate competitive environment (Baron 2013; McDonnell 2016). In the past, companies perceived their nonmarket environment as more or less exogenous. Nowadays however, many corporations extend their scope of strategic thinking by including activities to take an influence on decisions of political, legal or social actors (Funk and Hirschman 2017; Guo et al. 2014; Werner 2015). Ever since Baron’s (1995) publication, activities to strategically shape the nonmarket environment in order to achieve corporate objectives are referred to as nonmarket strategies (Baron 1995; He et al. 2007; Kobrin 2015; Mellahi et al. 2015). ‘Strategically’ here means that nonmarket activities are suitable to create future success potential (Johnson et al. 2003) or a competitive advantage (Husted et al. 2012). Nonmarket strategies frequently show a certain consistency in behavior, which distinguish them from purely operative ‘stand-alone’ nonmarket activities (Mintzberg 1979).

Nonmarket strategies are classified into social and political sub-strategies. Despite their common core objective to influence the nonmarket environment, empirical studies rather look at either social or political strategies implying a content-related distance or even diversity. As a result of the empirical fragmentation, most contributions to the nonmarket strategy research field are isolated and stand-alone articles restricting comparative analyses (De Figueiredo 2009; Hillman et al. 2004; Lawton et al. 2013). Even though empirically different measures for political and social strategies are applied, it can be assumed that antecedents of those strategies will not be completely different. Looking at multinational corporations for example shows that they often design a series of parallel (social and political) activities to shape their environment, which might not be triggered by completely different factors. A first attempt to integrate political and social antecedents was made by Mellahi et al. (2015), who, however, point particularly to performance implications of nonmarket strategies. Thus, a comprehensive review that considers both social and political nonmarket strategies and consolidates findings across research areas is still missing.

With this article, we make two specific theoretical contributions. First, we provide a synthesis of current research findings by conducting a systematic literature review. In contrast to studies and reviews which address the topic in a partial and isolated way, only examining (facets of) nonmarket sub-strategies, the present review aims at a holistic perspective that integrates previously unconnected research streams. Our analysis extends previous studies, such as Mellahi et al. (2015) or Lawton et al. (2013) by including two different aspects: (1) we are going to analyze internal and external antecedents that refer to nonmarket sub-strategies and their impact on firm performance, and (2) we will explicitly consider the modes of nonmarket strategy coordination with market strategies into an integrated strategy. This approach contributes to nonmarket strategy research by consolidating knowledge from different research fields and creates connections between them. The importance of such connections for progress within a discipline is generally regarded as high (Suppe 1979). Particularly in young or heterogeneous research fields the landscape can be characterized by playing different ‘language games’ in the sense of Wittgenstein’s (2010) philosophy of language. Research streams as language games can be considered as communications that are fundamentally bound up with their research context in which they are embedded (Seidl 2007). As a direct transfer of knowledge between these contexts is regarded as difficult, integrative reviews unfold their scientific significance because they are able to reveal connections (Chomsky 1988).

Second, previous nonmarket strategy research receives only little methodological benefit from market strategy research. In the majority of cases the terms nonmarket strategy and nonmarket activity are used synonymously. In strategy research, however, only activities that meet certain requirements are referred to as ‘strategic’ (Johnson et al. 2003; Mintzberg 1979; Porter 1996). Therefore, we are going to analyze how the term ‘nonmarket strategy’ is defined and which viewpoint of strategy is applied in current nonmarket research. By focusing on strategy content and process research, we propose to open up future research by embedding nonmarket strategy research more strongly into ‘traditional’ strategy research, at the end of this paper. To reach the outlined objectives we conduct a systematic literature review based on a conceptual framework that sheds light on nonmarket research from a strategic perspective.

2 Framework

Our literature search and review process is guided by an analytical framework (Ginsberg and Venkatraman 1985; Goranova and Ryan 2014; Rajagopalan et al. 1993) that builds on two central arguments. Firstly, the framework turns towards a content-based perspective. Strategy content research focuses on the causes and consequences as well as on characteristics of a content-related strategic object, such as nonmarket strategies (Chakravarthy and Doz 1992; Fahey and Christensen 1986; Pettigrew 1992; Huff and Reger 1987). Therefore, in our framework, nonmarket strategies are considered to be directly influenced by the (internal or external) corporate context. Secondly, the implementation of nonmarket strategies leads to certain corporate outcomes (performance) that are in turn assumed to be both directly and indirectly moderated by internal and external factors.

Based on these arguments, we propose a content-based framework that incorporates ideas from contingency and configurational approaches (Short et al. 2008; Zeithaml et al. 1988; Miller 1986) as well as from a fundamental action-oriented perspective (Parsons and Shils 2001). The conceptual framework consists of the following components (see Fig. 1): To explain the choice of nonmarket strategies, recently discussed and highlighted internal and external antecedents will be summarized (research stream 1–3, research stream 2–3). Diverse antecedents are identified as having a direct impact on strategy as well as an indirect impact on firm performance (research stream 3–1–4 and 3–2–4). In which way firm performance is (or is not) directly influenced by nonmarket strategic behavior is part of a third research stream (research stream 3–4). Finally, recent publications on the integration of market and nonmarket strategy, as suggested by Baron (1995), are considered to gain a thorough understanding of the research field (research stream 3).

Overall, we promote an ex-ante (deductive) framework to improve the comprehensiveness of the review, since it provides a generic meta-structure and thus allows a systematic identification of existing research gaps (Ginsberg and Venkatraman 1985). In addition to integrating antecedent and consequence variables associated with content-oriented strategy research, the framework helps to serve as a convenient analytical scheme to categorize and review past conceptual and empirical publications on nonmarket strategy research. Furthermore, the model can assist to guide future studies in the research field.

3 Methods

We conduct a systematic literature review (Cooper 1998; Petticrew and Roberts 2009) to map and assess the body of knowledge on nonmarket strategies and to point out prevailing research gaps (Chalmers et al. 1993). A review can be seen as a systematic, transparent and replicable approach to create a reliable knowledge base that goes beyond the analysis of individual studies (Davies 2004; Petticrew 2003). The selection of databases and journals, which form the basis of the literature search, as well as the definition of inclusion and exclusion criteria will be outlined subsequently (Fink 2005).

The review includes articles meeting the following three criteria: it must be (1) an anglophone article, (2) published in a high-level academic journal, (3) published in the period from 1995 to 2016. David P. Baron’s article: “Integrated Strategy: Market and Nonmarket Components”, published in 1995 in California Management Review, builds the foundation for the literature review. This article marks the beginning of nonmarket strategy research within the discipline of strategic management and limits the literature search to 1995 and later. To guarantee a high publication standard, the VHB-JOURQUAL ranking (version 2.1) serves as a validation base, whereof all A, B and C ranked journals are included in the search. Hence, books, dissertations, practical reports or other articles published in journals that have a lower ranking or are not ranked and articles that were not written in English as well as articles that were published before 1995, are excluded from this review.

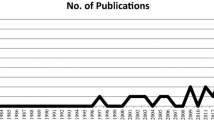

The search for literature was conducted in two ways. First, all articles which cite Baron’s article were collected and second a keyword search (“Nonmarket strategy”, “Social strategy” and “Political strategy”) was conducted to complement the literature search (for both searches the three filter criteria: language, time period, journal ranking were applied). The specific inclusion of the keywords political and social strategy underlines the holistic approach, as already outlined in previous parts of this paper. Moreover, the keyword search is explicitly addressing the term “strategy”, to assure a connection of the reviewed publications to strategy. This is of particular importance, since many publications are addressing single activities, such as network building or lobbying the government on operative grounds. Accordingly, only those papers are included that are explicitly addressing a strategic perspective.Footnote 1 To run the search, the following online databases were selected: EBSCO Business Source Premier, Science Direct, JSTOR and WISO. After separating articles with a content misfit, 191 articles remain for analysis. Since nonmarket strategy research is considered a relatively young research field, we include empirical as well as conceptual studies for our analysis. Conceptual papers published in high ranked journals can provide valuable insights on the phenomenon and can help to form and develop assumptions for subsequent empirical studies. However, presented key findings are mainly based on empirical results. Whenever considerations or propositions based on conceptual papers are included in the review, they are carefully highlighted and distinguished.

4 Review

4.1 Structure, streams, and summary of the review

Based on the developed conceptual framework, four nonmarket research streams were identified and articles were collected accordingly. Streams 1–3 and 2–3 examine internal and external antecedents of nonmarket strategies that are discussed within academic literature. Stream 3–4 summarizes findings on performance implications of nonmarket strategies. Whereas these streams are based on a solid number of empirical findings, research stream 3 (referring to strategy integration and how market and nonmarket strategies can be incorporated into a so-called integrated strategy (Baron 1995, 1997b) can be seen as an emerging one, based on a scarce amount of empirical as well as conceptual studies. Key findings, underlying research methods and sample size of the considered articles are summarized in Table 1. In the following we are going to alternately consider important findings that derive from both research streams. Additionally, in line with our objective to synthesize findings from political as well as social strategy research, we logically generalize i.e. antecedents and consider them as relating to nonmarket strategies, if they are discussed analogously in both research streams.

4.2 Stream 1–3: internal factors

From a corporate perspective, several factors can be identified as having an influence on the nonmarket strategy choice. As predominantly discussed within current academic literature, corporate demographics, management orientation and market strategy can be outlined as superordinate categories. These categories and their corresponding internal factors will be discussed subsequently.

4.2.1 Corporate demographics

Corporate demographics and key figures, such as firm size and age, market share or resource dependencies can have an impact on the choice of nonmarket strategies. Within the reviewed literature, it is frequently argued that larger firms have more financial resources to spend on political and social strategies (Lux et al. 2011; Hillman et al. 2004). Accordingly, it is assumed that large firms tend to be more engaged on a social, legal and political level, than small firms, due to budget restrictions (De la Cruz Déniz-Déniz and Garcia-Falcón 2002; Schuler 1996). In addition to the argument that firm size has an impact on financial resources, it is further argued that large firms do possess an above average amount of stakeholders and might therefore be more visible and hence need to be more committed on a nonmarket level in comparison to small and medium sized firms (Hillman and Wan 2005). Furthermore, it is argued that the largest firms in terms of market share face the highest exit costs in their industry. Therefore, nonmarket strategies become more valuable for these firms, which are suitable to stabilize prices or margins (Schuler 1996). Firm size as an antecedent for nonmarket behavior can be identified in several empirical publications, which measure “size” based on varying factors, such as number of employees, market share or turnover (Cook 2015; De la Cruz Déniz-Déniz and Garcia-Falcón 2002; Hillman and Wan 2005; Lux et al. 2011; Meznar and Nigh 1995; Schuler 1996; Schuler et al. 2002a, b). Besides those resources owned by a firm, resource dependencies might also impact nonmarket behavior. High external resource dependencies might pressure the corporation to actively engage in nonmarket dialogue and to build up strategic relationships. Thereupon, Shirodkar and Mohr (2015a) examine the impact of corporate resource dependencies on strategy development. The authors argue that a political information strategy will primarily be implemented by foreign subsidiaries in emerging markets depending on intangible resources rather than on tangible ones. Even though this research setting seems rather specific, a first deduction can be drawn, namely that external resource dependencies might have a positive impact on nonmarket strategy adoption.

Firm age is another internal antecedent identified in the reviewed literature. It is argued that firms, which are active in a market for a long time, do have a greater credibility and reputation due to their accumulated experience. In turn, this might lead to potentially higher chances of success in the political, social or legal sphere. On this basis, it is argued that a higher firm age accompanied by experience increases the likelihood of the adoption of corporate nonmarket strategies. This reasoning can be traced in conceptual (Lamberg et al. 2004) as well as empirical studies (Lamberg et al. 2004; Schuler and Rehbein 1997). As an example, Schuler and Rehbein (1997) argue that past political experience has a positive effect on a firm’s ability and willingness to become politically involved. This is explained by an increased rootedness of the activity within corporate behavior.

4.2.2 Management organization

A further internal antecedent impacting the development of a firm’s nonmarket strategy is the management organization regarding the involvement and attitude of its managers as well as its organizational structure. It is argued that the organizational structure, like the existence of a separate department for public relations, and the number of employees working there, indicates how active the firm is trying to position itself on a nonmarket level (Schuler 1996). Following this reasoning, we can assume that a firm possessing nonmarket departments and a comparatively large number of specialized employees correspondingly develops more nonmarket activities. Nevertheless, being engaged in a greater amount of nonmarket activities can also require more employees or specialized departments, which questions the outlined correlation. Following this logic, organizational structure can also be regarded as an outcome of having a nonmarket strategy rather than an antecedent.

Besides the organizational structure we further find that differences in orientation, attitude, and experience of owner or management are important factors when it comes to the choice of nonmarket strategies (Rehbein and Schuler 1999; Schuler and Rehbein 1997). In the identified articles, it is argued that the strategic positioning in the market as well as in the nonmarket environment is influenced by individual opinions and assumptions of the company’s managerial board. This effect is strengthened by the circumstance that managers or the owner mainly determine the financial resource allocation, which also includes the budget allocation for nonmarket activities. This reasoning finds support in conceptual (Wilts 2006) as well as empirical studies (Husted et al. 2012; Ozer 2010). The influence of top management teams on strategic decision-making is inter alia studied by Ozer (2010), who quantitatively finds that personal involvement of top management teams is positively related to the choice of political activities.

Furthermore, decision-making processes (Mathur et al. 2013; Ozer 2010), ownership structure of a company (Husted et al. 2012) or the origin of the management (De la Cruz Déniz-Déniz and Garcia-Falcón 2002) can affect the development of political strategies. Accordingly, De la Cruz Déniz-Déniz and Garcia-Falcón (2002) argue that the employment of a majority of local managers leads to an increased region-specific social awareness and knowledge of local environmental conditions. Awareness and knowledge of local environmental or social challenges can build the foundation for social strategy choice. An informed and aware manager is able to develop and implement social activities that help to increase public reputation and support the overall firm strategy. Thus, it seems arguable that a majority of local managers might initiate social strategies. The more local a board of managers is, the more nonmarket engagement on a social level can thus be expected.

We further find support for the argument that the length of employment and the rootedness of the management might have an impact on nonmarket strategy. Ozer (2010) for example, argues that CEO tenure has a positive impact on the development of political strategies. The author further argues, that a long-tenured CEO might have a better understanding and sense of how developments within the political environment impact firm strategy. Thus, a long-tenured CEO is more willing to initiate corporate commitments to political activities. Correspondingly, it can be summarized that the more tenured a CEO is the more he will implement nonmarket strategies. This goes in line with the previously outlined antecedent of top management experience.

4.2.3 Market strategy

Within the literature review we identify the strategic market positioning of a company as another internal antecedent. Numerous of the reviewed articles investigate the impact of a diversification strategy (Blumentritt and Nigh 2002; Hillman 2003; Hillman and Wan 2005; Lux et al. 2011; Shaffer and Hillman 2000; Shirodkar and Mohr 2015b; Urbiztondo et al. 2013; Wan 2005). The basic idea is that a highly-diversified company with different divisions might benefit from synergies while engaging in nonmarket activities. Lobbying for example might have positive effects not only for one business division but for others as well. This in turn might lead to cost savings as well as to an increased awareness of policy makers and social actors. Hence, due to synergy effects, a diversification strategy positively impact nonmarket strategic behavior. This connection between nonmarket strategy and product diversification is conceptually highlighted in a paper by Hillman and Hitt (1999) and finds empirical support in a publication by Hillman (2003). In a quantitative study the author examines the influence of international diversification on political strategy choice. The scholar finds that international diversification does have a significant positive impact on the development of political financial incentive strategies. It can furthermore be stated that impact of diversification on nonmarket strategies can be specified more precisely on the question of what is diversified and certainly also to which degree. Especially the heterogeneity of diversified business units might explain the impact on nonmarket strategic behavior. Whereas corporations diversifying in rather homogeneous markets do not significantly benefit from synergy effects on a nonmarket level, corporations diversifying in heterogeneous markets do, since synergy effects increase in impact. Heterogeneity of markets increases on an international level, which is why it is assumable that international diversification does have a significant positive impact on nonmarket strategies (Hillman and Hitt 1999; Hillman 2003; Shaffer and Hillman 2000).

Although there is strong evidence that (international) diversification is positively related to nonmarket strategies, it also has to be said that some scholars come to divergent findings concerning the direction of influence. Accordingly, Schuler (1996) argues within a quantitative study that diversification (related diversification in terms of internal synergies by sharing resources and expertise, as well as the emergence of economies of scope) has no significant influence on the adoption of political strategies. However, he explained this lack of significance particularly with methodical/measurement weaknesses so that there might be some caveats to consider the negative effect strongly. Another market strategy identified in the literature as having an impact on nonmarket strategies is highlighted by De la Cruz Déniz-Déniz and Garcia-Falcón (2002). The authors argue that an international growth strategy can lead to an increase in social activities. Here, the authors distinguish between the desire to grow on an international level and the desire to only expand internationally to take advantage of lower costs (e.g. production, labor). The latter one in turn might lead to a decrease in social activities. This finding supports the previously outlined assumption that an international diversification has a positive impact on nonmarket strategy choice due to synergy effects.

4.3 Stream 2–3: external factors

In addition to the internal antecedents we aim to shed light on external antecedents that might have an impact on nonmarket strategies choice. For reasons of clarity, the subsequent section of this paper is divided into external antecedents arising in the market and nonmarket environment.

4.3.1 Market environment

The market environment is characterized by interactions between corporations, suppliers and customers that are either governed by markets or private agreements (Baron 1995, 2013). Within the reviewed literature, these interactions as well as related contextual factors were identified as having an impact on nonmarket strategies. Accordingly, the reviewed literature reveals that industry affiliation might act as an external antecedent (Breitinger and Bonardi 2016; De la Cruz Déniz-Déniz and Garcia-Falcón 2002; Husted et al. 2012; Husted and Allen 2007; Lamberg et al. 2004; Lux et al. 2011; Rehbein and Schuler 1999; Schuler et al. 2002a). This can be explained by factors such as industry dynamics, industry concentration and regulation or strength of bargaining power of operating actors within the industry. To give an example, it is argued that firms belonging to a particular competitive market or facing a high amount of competitors tend to be more prone to develop social strategies to achieve a competitive advantage (Husted and Allen 2007; Husted et al. 2012). In this case, competition acts as a pressure intensifier to adopt social strategies. Hence, it can be assumed that the more competition within an industry exists, the more social strategies will be applied to improve corporate reputation. The industry affiliation is furthermore discussed as an external antecedent, since industries differ significantly in terms of governmental regulations or subsidies. Resource-related industries, such as the steel-, oil-, telecommunications- or the pharmaceutical industry can be summarized as highly regulated industries. Correspondingly, it is assumed that firms belonging to these industries are more likely to adopt political strategies than firms belonging to industries with a low degree of regulation (Bonardi 2008; Husted and Allen 2007). Therefore, we can assume that the more regulated an industry is, the more political strategies will be applied to influence political actors in ways favorable for the firm (Hillman et al. 2004). It is further argued that firms operating in so called “controversial industries” (e.g. mining, tobacco) or industries close to respective customers (e.g. personal goods, food/beverage) do face a greater need to implement nonmarket strategies. This is due to the fact that firms in these industries are frequently targeted by activists’ campaigns because they sell unhealthy or dangerous products/services or damaging their reputation is less costly than harming an industrial products company (Breitinger and Bonardi 2016; Lenox and Eesley 2009). The assumption that the industry affiliation of a firm influences the adoption of nonmarket strategies can be traced in numerous publications (Husted and Allen 2007; Husted et al. 2012; Lamberg et al. 2004; Lux et al. 2011; Rehbein and Schuler 1999; Schuler et al. 2002a). Consequently, we can assume that the more controversial or “close-to-consumer” an industry is, the more nonmarket strategies will be applied.

Within the reviewed literature various market stakeholders, such as competitors or customers, are discussed as having an impact on the adoption of nonmarket strategies. Nonmarket activities of competitors are considered as having a positive impact on the intensity of a firms own nonmarket strategy. Thus, it is suggested that firms whose direct competitors are heavily socially or politically active will also align their activities accordingly to avoid a competitive disadvantage. Lux et al. (2011) amplify this argument to international competition and the intensity of lobbying. Additionally, the determining influence of market stakeholders on nonmarket strategies is discussed in various articles (De la Cruz Déniz-Déniz and Garcia-Falcón 2002; Husted et al. 2012; Kassinis and Vafeas 2006; Reimann et al. 2012; Schuler and Rehbein 1997). As further antecedents, the firm’s country of origin as well as the country in which it operates are identified in the literature. For instance Hillman and Hitt (1999) conceptually distinguish between firms operating in pluralist and corporatist countries and outline a relation to the chosen approach of political behavior. Given features of a society are thus outlined as having an impact on applied strategies. Since within corporatist countries cooperation is emphasized, the authors assume that companies tend to adopt more relational strategies to build up social capital in contrast to more individual and competitive strategies in pluralist countries. Hillman (2003) endorses this reasoning by providing empirical support for the proposition that the institutional context impacts political strategy development. Summarizing, characteristics of the industry, such as rivalry, concentration, regulation, or strategic intents of competitors positively stimulate political as well as social nonmarket strategies, on the basis of which firms try to obtain legitimacy and support.

4.3.2 Nonmarket environment

The nonmarket environment can have an impact on nonmarket strategies as well. Pressure from NGOs, associations or activist groups often leads to so-called passive nonmarket strategies, including activities such as adjustments or reactions to external changes (Blumentritt 2003; Dieleman and Boddewyn 2012; Lawrence 2010; Meznar and Nigh 1995). Beyond that, the nonmarket environment can also trigger a corporation to implement active nonmarket strategies to influence social, political or legal actors to achieve corporate objectives. Within the reviewed literature, it is argued that the number of NGOs and activist groups in the environment has a positive impact on the adoption of nonmarket strategies. Likewise, Vachani et al. (2009) conceptually outline that pressure from social actors might influence firms either to adapt or to actively seek change via social strategies. Empirically it can be shown that a higher amount of social nonmarket stakeholders leads to an increased amount of nonmarket activities (Husted et al. 2012; Reimann et al. 2012; Vachani et al. 2009; Kassinis and Vafeas 2006; Spar and La Mure, 2003; Schuler et al. 2002a; Schuler and Rehbein 1997). Within reviewed publications this is explained by the related fear of a possible threat or the development of pressure by activist groups such as campaigns or boycotts, which might force businesses to adapt certain practices (Schuler et al. 2002a). Schuler et al. (2002a) further stress that union density within an industry may also have a positive impact on pursued political strategy. Hence, within an environment characterized by a high number of nonmarket actors, corporations tend to operate proactively by implementing nonmarket activities.

Another antecedent can be seen in the lack of control over the social, political and legal environment. This reasoning is inter alia brought up by Doh et al. (2015) who conceptually compare social strategies of multinational enterprises (MNEs) in emerging and developed market economies. The authors find that a lower presence of NGOs and a lower awareness of and knowledge about environmental and social problems detain MNEs from engaging in social activities, which goes in line with the previously outlined antecedent of nonmarket activities namely the number of nonmarket stakeholders. Since developing countries appear to be characterized by a lower presence of NGOs and a lower awareness and sophistication concerning social and environmental issues, the authors question why corporations operating in those regions nevertheless implement nonmarket strategies. They conclude that not the absence of nonmarket stakeholders, but the presence of institutional voids force MNEs to engage in social activities such as pursuing corporate social responsibility. This reasoning is supported by Zheng et al. (2015), who empirically confirm that political activities in emerging market economies are triggered by institutional voids. Nevertheless, it is also argued that high levels of governmental regulations, such as strong restrictions or taxations, might lead to an increase in nonmarket activities. This reasoning is explained by an expected improvement of corporate conditions by implementing lobbying activities, such as a loosening legal constrictions (Lux et al. 2011). Summarizing, characteristics of the nonmarket environment, such as number of NGOs and activist groups, social stakeholders, or the presence of institutional voids have a positive impact on the adoption of nonmarket strategies.

Within the reviewed literature, it is increasingly argued that environmental uncertainties threaten a firm’s core activities (Akbar and Kisilowski 2015; Heidenreich et al. 2015; White et al. 2015). To overcome environmental uncertainties firms can complement market strategies by implementing nonmarket strategies. Particularly international or multinational firms operating in developing or emerging markets are strongly affected by environmental uncertainties, because they operate in different institutional regimes with diverse regulations and stakeholders. Therefore, multinational firms can be regarded to be in an exposed role for nonmarket strategy adoption (Blumentritt 2003; Keim and Hillman 2008; Puck et al. 2013). Increased attention by (international) NGOs and the news media as well as legal and political instabilities can be seen as impellers of an uncertain nonmarket environment. Within the reviewed literature empirical contributions show that internationally operating firms try to influence nonmarket actors via nonmarket strategies in order to overcome such uncertainties (Akbar and Kisilowski 2015; Heidenreich et al. 2015; Meznar and Nigh 1995; Parnell 2015; White et al. 2015). Uncertain environmental conditions are further found to have an impact on the type of implemented nonmarket strategy. In a qualitative study Shirodkar and Mohr (2015b) conclude that firms operating in emerging markets increasingly implement short-term activities (such as reactions to new regulations), in contrast to long-term activities (such as relationship building) in developed markets.

Besides environmental uncertainties in general, institutional changes or shocks are particularly discussed as a potential antecedent within the reviewed literature (Darendeli and Hill 2016; Lamberg et al. 2004; Sun et al. 2015b). Even though environmental uncertainties might trigger nonmarket activities and thus initiate legitimacy and assist firm survival (Darendeli and Hill 2016), especially political-ties need to be handled with caution since they are threatened by political shocks or turnovers (Lamberg et al. 2004; Sun et al. 2015b). Summing up, it can be said that a number of studies have found that a wide range of external factors influence nonmarket strategies. Industry characteristics such as rivalry or concentration, strategic intents of incumbents, political competition, governmental regulations and perceived environmental uncertainty are among the most frequently observed determinants of nonmarket strategies.

4.4 Stream 3: the phenomenon of an (integrated) nonmarket strategy

4.4.1 Definition of nonmarket strategy

Stream 3 refers to the phenomenon under study—nonmarket strategy, its understanding and integration attempts. As a first step, we analyze how the phenomenon is defined in the reviewed literature. Surprisingly, although all reviewed articles deal with political or social nonmarket strategies, our analysis reveals that only few scholars explicitly specify the dependent variable ‘nonmarket strategy’. A large part of articles refer to specific political or social activities without devoting emphasis to explain, under which conditions nonmarket activities can be categorized as ‘strategic’. Bonardi et al., for example, define nonmarket strategies as “coordinated actions firms undertake in public policy arenas” (Bonardi et al. 2006, p. 1209). However, it can be assumed that not all of these actions will turn out as strategic: a certain proportion may be operative in nature. More precisely, Husted et al. (2012) aim to replicate the intention of ‘market’ behavior and only refer to those activities that seek to create competitive advantage and economic value. They define social strategy as “a portfolio of social projects organized with the purpose of creating value for the firm” (Husted et al. 2012, p. 6).

In such articles scholars explicitly define nonmarket strategies, they predominantly take the viewpoint of strategies as specific activities or maneuvers. Hillman, for example, defines political strategies as “proactive actions taken by a firm to affect the public policy environment in a way favorable to it” (Hillman 2003, p. 455). Hillman and Hitt (1999) refer to those maneuvers as corporate lobbying, press conferences, grass root mobilization or public relations. However, in the ‘market strategy domain’, the term ‘strategic orientation’ refers to another commonly used perspective of ‘strategies’ (e.g. Mintzberg 1979). Pursuing a ‘strategic orientation’ means that a company develops a shared perspective or plan about what kind of (nonmarket) activities should be pursued. From the reviewed articles, only Husted and Allen (2007) and Husted et al. (2012) consider a similar view. In their study about antecedents of corporate social strategy Husted and Allen (2007) distinguish between ‘social strategic planning’ and ‘social strategic positioning’. In sum, most of the reviewed articles do not explicitly specify what makes a nonmarket activity strategic and only few scholars consider differences within the term ‘strategy’. We are going to discuss potential benefits of a comprehensive strategy view point for nonmarket strategy research in the implications section below.

Research stream 3 furthermore examines possibilities of market and nonmarket strategy integration. The necessity of strategy integration is highlighted by Baron (1995), who speaks of an integrated strategy. Such an integrated strategy needs to be aligned with firm specific competencies as well as market and nonmarket environmental conditions. Thus, it contains market and nonmarket components, which should be coordinated by the management. Baron extends this reasoning in two constitutive publications in which he conceptually analyzes the Kodak/Fujifilm case (Baron 1997a, b). The author examines the competition between Kodak and Fujifilm within the Japanese market. As an US-based corporation, home and host country nonmarket strategies of Kodak are compared. Doing so, the author highlights the importance of the corporate environment on strategic choice. He concludes that an integrated strategy needs to be region specific since the nonmarket environment is subject to regional institutions, regulations and cultures (Baron 1997b). However, it remains unclear how international corporations delegate responsibilities regarding the development of market and nonmarket strategies across borders and how an integrated strategy can be coordinated.

Besides a small amount of conceptual and empirical papers highlighting its importance, in recent academic publication the question of strategy integration only finds scarce attention. Conceptual papers, stressing the importance of an integrated strategy are for example published by Salorio et al. (2005), Rudy and Johnson (2013) or White et al. (2014). Empirical studies, published inter alia by Mahon and McGowan (2016) or Wei et al. (2015). Salorio et al. (2005), stress that an integration of political and economic strategies has to be carried out in order to be able to meet environmental requirements. Based on an outlined “strategy cube”, the authors argue that an integrated strategy can become the source of a rent-creating competitive advantage. Besides highlighting this necessity and profitableness, the authors however fail to explain how a successful integration can be achieved and which implementation mechanisms can be applied. A similar argument can be traced in a publication by White et al. (2014) who also emphasize a link between an integrated strategy and a sustainable competitive advantage and an increased business performance.

Moreover, Levy and Egan (2003) support Barons argument that strategy integration is a central task of the management. They additionally claim that market- and nonmarket strategies should be treated as one, since both environments are strongly connected and interdependent. Similarly, Holburn and Vanden Bergh (2014) emphasize the importance of an integrated research approach and criticize that academic discussions have evolved mainly separated from each other. Within their quantitative analysis, the authors raise the question how nonmarket strategies, such as financing of political campaigns, can support market strategies, such as mergers. As a result, the authors point out that firms involved in valuable market transactions (such as mergers) tend to invest more into nonmarket activities when there is an increased risk of government dissipation of economic rents (inter alia through regulatory mechanisms). Correspondingly, the authors are able to demonstrate that a greater integration of nonmarket activities is observable during valuable market transactions. By analyzing a specific event in the market environment (such as a corporate merger with the potential to create high economic rents), the authors are able to demonstrate how corporations integrate and adapt nonmarket strategies during the time around the event in contrast to business-as-usual. Thus, it might be assumed that nonmarket strategies are likely to be introduced complementary to market strategies (Holburn and Vanden Bergh 2014).

Within the systematic literature review we reveal that until this day only few studies deal with the question of an integrated strategy and rarely go beyond highlighting its importance. Nevertheless, we identify two streams of discussion: A first one focuses on the question how market and nonmarket strategies can be integrated and a second one deals with the allocation of responsibilities during an integration process. The latter one is mainly focusing on multinational corporations operating in various market and nonmarket environments.

4.4.2 How to integrate

The question how market and nonmarket strategies can be integrated is for example discussed by Maxwell et al. (2002). By conducting a qualitative case study analysis, the authors examine how environmental strategies can be integrated into an overall firm strategy. The authors find that the analyzed companies attempt to achieve an integrated strategy by developing and tailoring their nonmarket activities to their organizational competencies. According to this, product and financial issues as well as a corporation’s philosophy are discussed as having an impact on nonmarket strategy development and integration. The degree of consistency thus determines whether an existing core strategy is disrupted by nonmarket strategy implementation. Therefore, it can be argued that a greater degree of market and nonmarket component consistency triggers a greater feasibility of strategy integration. Additionally, the authors observe integration methods such as the adaption of company structures (i.e. implementation of groups at division level or lower level managers to set up goals) or the implementation of competence centers to position nonmarket strategies within the company. Formal and informal control mechanisms, such as employee trainings or reporting systems are found to positively affect strategy integration. Moreover, the authors observe that an alignment of nonmarket activities with corporate culture can be applied as an informal mechanism to integrate strategies. This might inter alia be achieved by tailoring activities to an existing brand management culture (Maxwell et al. 2002).

However, strategy integration is not always possible, it is dependent on specific external and internal conditions, such as laws and regulations or scarce financial resources. Bonardi (2004, 2008) for example argues that market and nonmarket strategies are not always integrable, since they are not in any case perfect complements (Bonardi 2004). The author empirically confirms and refines this proposition by elaborating further limitations of strategy integration (Bonardi 2008). From a corporate perspective, the author argues that successful nonmarket strategies often depend on the input of specific market factors (e.g. human resources). Thus, these nonmarket activities regularly become alternatives for market activities, as resources are scarce. Certainly, this describes a trade-off decision faced by the management, which stresses that market and nonmarket activities do not always act as complements but in some cases as substitutes. Management needs to decide whether financial and human resources are used for market or nonmarket activities. Bonardi (2008) argues that in such trade-off situations, firms would usually give priority to market strategies to secure the core business. This approach points out that the integration of market and nonmarket strategies is bound to certain conditions which do not only arise out of external constraints (such as by laws or regulations), but also out of internal limitations (such as scarce resources).

4.4.3 Allocation of responsibilities

As described above, the second research strand deals with the distribution of power in course of a strategy integration process. This is for instance examined by Shaffer and Hillman (2000), who analyze within a qualitative case study how large, diversified corporations with different business units decide which political strategies are implemented into the overall firm strategy. The authors particularly focus on financial resource allocation of subsidiaries as well as on political resource allocation. Thus, next to limited financial capital, the corporation has limited political capital (such as the ability to influence political decisions and government policy). Within diversified firms, individual business units need to compete for those scarce resources. Their findings indicate that strategy integration induces internal coordination challenges concerning the allocation of competencies between headquarters and subsidiary. Shaffer and Hillman (2000) recap their empirical findings in a matrix to present different options of authority distribution between company units. Therein, the scholars distinguish between companies that carry out the integration centralized, shared or decentralized. Within the centralized corporation, a single business unit will determine strategy development and integration (the authors do not speak explicitly of headquarters/subsidiary-relationships). In contrast, within the decentralized corporation each individual business unit decides independently on regional political situations and develops individual strategies. In the divided or shared corporation, strategy decisions are made jointly and coordination problems are solved together. This shall be achieved through a so-called coordination unit, which brings together representatives of each business unit to discuss strategic options jointly.

Windsor (2007) takes a similar research perspective and focuses on multinational corporations operating in diverse environments. The author conceptually tackles the question, how the resource allocation influences the development and integration of particularly political strategies within subsidiaries. The author concludes that market and nonmarket strategy formation within multinational companies can be seen as a dynamic process that is strongly dependent on resource allocation processes and changing regional environmental conditions. The author states that the typology of subsidiary role-models proposed by Bartlett and Ghoshal (1986) can be used to identify core business units to reduce resource allocation to a selected set of business units. However, resource allocation needs to be handled across boarders as well as across divisions (political, social and market divisions within each business unit), which makes it a multi-level problem. Thus, Windsor (2007) calls out for further empirical research.

Concluding, it can be stated that conceptual and empirical publications addressing the issue of strategy integration are rather scarce. Despite some publications highlighting individual formal or informal coordination mechanism, a thorough examination is missing. Moreover, it remains more or less unclear who should bear the responsibility for strategy integration, especially considering multinational corporations. This finding is somehow unexpected, since the importance and value of an integrated strategy finds broad agreement within the current research discussion.

4.5 Stream 3–4: consequences on economic performance

Research stream 3–4 examines the impact of nonmarket strategies on firm performance. As will be described in greater detail hereafter, it can be anticipated that a strategic impact on nonmarket stakeholders, such as political or social decision-makers, via nonmarket activities, such as strategic network building or representation of interests, can have a beneficial effect on firm performance in the long-run. Within the reviewed literature numerous publications examine this relationship (Bonardi et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2015; Hillman et al. 1999; Johnson et al. 2012; Lux 2013; Rajwani and Liedong 2015; Rudy and Johnson 2013; Shaffer et al. 2000; Tang and Tang 2012; Wagner 2007; Wei 2014). Given the broad spectrum of nonmarket activities and strategies, it is not surprising that the results vary depending on the analyzed strategy type and activity as well as on the applied indicator to measure firm performance.Footnote 2 Reasons for these ambiguities are discussed in the ‘implications’ section below. Since the topic of performance implications is often referred to in the individual reviewed studies, this point will also be included in the following abstracts.

4.5.1 Positive impact

A broad majority of the reviewed studies suggest a positive impact of nonmarket strategies on firm performance. In a quantitative study Shaffer et al. (2000) assess the impact of market and nonmarket activities on firm performance of airlines operating in the North Atlantic region. The authors measure performance via three indicators: profits, market share and capacity utilization. They come to the conclusion that nonmarket activities have a significantly positive impact on firm performance in terms of all three tested indicators. In contrast, the results of the study illustrate a non-significant impact of activities within the market environment on firm economic performance (Shaffer et al. 2000).

Several scholars empirically demonstrate a positive impact of nonmarket strategies and especially social strategies on firm performance (Hawn and Ioannou 2016; Husted et al. 2012; Kiessling et al. 2015). Husted et al. (2012) for example, examine the impact of social activities on firm economic value. Building on resource-based and resource-dependence theory, the scholars investigate the impact of strategic social planning and strategic social positioning via a quantitative research design in 110 major Spanish companies. They come to the conclusion that both strategy types do have a positive impact on firm economic value. However, a significantly stronger impact could be identified for social positioning. A positive relationship between social strategies and firm performance is further affirmed by Kiessling et al. (2015). The authors explain their quantitative findings by stressing the importance of a social positioning in times of global competition and information accessibility. Maurer et al. (2011) argue conceptually that particularly cultural and social activities do have a positive impact on the economic value associated with a firm’s strategy. The authors explain this reasoning with an increased possibility of gaining public legitimacy within the organizational field. Since the organizational field is able to create or destroy economic value, engaging in cultural or social work can preserve or even enhance a firm’s position.

Besides the above argued positive impact of social strategies on firm performance, there are also scholars proposing a positive impact of political strategies on firm performance (Chen et al. 2015; Hillman et al. 1999; Lux 2013; Lux et al. 2011; Mathur et al. 2013). In a quantitative study Mathur et al. (2013) for example examine the influence of lobbying as part of a nonmarket strategy on firm value, measured by return on assets. The authors figure that lobbying activities positively influence corporate value creation. They explain this finding by pointing out that lobbying activities are able to serve as an instrument to align the interests of management and shareholders (Mathur et al. 2013). Lux et al. (2011) come to a similar conclusion. Within a meta-analysis, the authors examine the impact of corporate political activities such as lobbying on firm performance. Performance is measured on the one hand via return on assets and on the other hand via the survival or failure of the company. The authors find that corporate political activities have a significant positive impact on firm performance. Based on these findings, they argue that the strategic influence of political actors in the corporate environment can generate a competitive advantage. Lux (2013) approves this result in a further study, by examining the influence of political strategies on firm performance. As an explanation for a positive impact Holburn and Vanden Bergh (2008) argue that by engaging in regulatory or political arenas, corporations have the chance to reduce the risks of unexpected or detrimental policy change.

Likewise, Hillman et al. (1999) test the influence of political strategies on firm value and come to a positive result. Within their quantitative study the authors focus on personal services of managers in political positions, such as political consultants or memberships in political committees. At multiple times, the authors measure firm performance comparing the market return with the market return of the entire industry in order to exclude external, cross-industry factors. The authors conclude that personal services as part of a political strategy do positively impact firm performance. Also, political relationships and socio-political reputation are found to positively impact firm performance (Brown et al. 2015; Werner 2015). In summary, there is broad empirical evidence that nonmarket strategies are positively related to performance. Some caveats to this interpretation, however, should be considered. On the one hand, it is important to notice that in some cases empirical studies provide evidence to negative effects of nonmarket strategies on corporate performance. We are going to discuss examples of these studies in the next section. On the other hand, it should be realized that studying nonmarket strategy effects on performance is part of a general success factor research. Nonmarket strategy-performance studies are therefore affected by all criticisms that are assigned to the success factor research strand, such as a highly complex dependent variable with heterogeneous measurements driven by a large number of factors (March and Sutton 1997). We are going to return to this issue in the ‘implications’ chapter more detailed.

4.5.2 Negative or ambiguous impact

In contrast to the previous section, the literature review also revealed opposing results suggesting a conditional or negative relationship between nonmarket strategies and firm performance. It can be argued that especially political activities can include social investments, such as building up networks and relationships with decision-makers, that might be dependent on election periods or stable developments within a system. This is examined in a quantitative publication by Leuz and Oberholzer-Gee (2006), who assess the long-term impact of political strategies of corporations operating in Indonesia. The authors argue that a close cooperation with political decision-makers might have negative consequences on firm performance when it comes to regime changes, because connections and ties to the government break away. Within this study this lead to a financial loss and a negative impact on firm performance. Guo et al. (2014) also examine the relationship between political strategies and firm performance with a focus on emerging markets, but do not come to a definite result. As a political strategy, the authors examine political ties of the management, such as interpersonal relationships with political decision makers. The authors focus on three different coherencies of political ties, which can lead to a positive performance impact: (1) political ties can support firms to achieve institutional support, which can manifest itself through resource procurement and lead to a competitive advantage; (2) political ties can contribute to build legitimacy and thus, reduce uncertainty and improve business performance; and (3) political ties can also help to identify and exploit business opportunities, by influencing policy makers and performance-related regulations. In a quantitative study, the scholars test these coherencies by analyzing survey data of 195 Chinese corporations. The authors measure firm performance by various financial (sales volume, ROA) and non-financial (market share growth, productivity) indicators. The results indicate that although a significantly positive relationship between performance and political bonds can be traced, only two of the three tested coherencies are significant. No significant impact was identified for legitimacy building on firm performance (Guo et al. 2014).

Such an ambiguous result can also be found in a study by Hadani and Schuler (2013), who quantitatively test the relationship between political strategies and firm performance of 943 large and mid-cap ‘Standard&Poors 1500’ firms in the period between 1998 and 2008. Firm performance is measured by market value and return on sales. On the one hand, the authors examine political strategies in terms of political investments (investments in lobbying or political campaigns) and on the other hand in terms of human capital investments (recruitment of staff with former political experience). Short- and long-term effects on firm performance are examined. Hadani and Schuler (2013) find that political investments do not have a negative impact on market value and return on sales. Human capital investments do also negatively impact the market value of a company and neutrally impact return on sales. The only positive exception in their study is shown for firms operating in highly regulated industries. Here, a positive relationship between political investment and market value was confirmed.

Drawing upon agency and resource dependency theory Sun et al. (2015a) further highlight the threat of a negative impact of board political capital on firm performance, due to the possibility of an augmentation of bargaining power over corporate surplus. Hadani et al. (2015) similarly argue on, that a politically active CEO might harm the corporation, by over-investing out of personal affairs.

Summarizing, it can be concluded that a disagreement about the consequences of nonmarket strategies on firm performance prevails in the reviewed literature. Next to a majority of studies suggesting and empirically confirming a positive impact, there are also contradicting opinions. Moreover, authors such as Leuz and Oberholzer-Gee (2006) or Hadani and Schuler (2013) even propose a negative impact in form of a deteriorating firm performance as a consequence of nonmarket strategies. This heterogeneity of findings is also highlighted by current publications and reviews (Mellahi et al. 2015; Rajwani and Liedong 2015). Within the following section of this paper reasons behind these differences and possibilities for future research are discussed in more detail.

5 Implications and guidance for future research

With this paper, we aim to provide a systematic overview of the current state of research on nonmarket strategy. We identified 191 articles, which can be assigned to the four previously outlined research streams and shed light on the respective thematic field. The previous sections provided an integrated, multi-perspective review of the nonmarket literature according to the research streams and incorporated findings from both research on social and political strategy. Key determinants are summarized in Fig. 2.

Besides the fact that particularly the structure of the market and nonmarket environment strongly affects the adoption of nonmarket strategies, further antecedents covering the internal configuration of corporations have been unveiled and discussed in this paper. Additionally, it became clear that the internal coordination of nonmarket and market strategies is only scarcely discussed in recent publications. Finally, with regard to performance implications, this review reveals a high ambiguity of the previous empirical results. Thus, within this final section, we aim to outline a research agenda that points out controversies and prevailing literature gaps. We structure our discussion into three main areas of interest: methodological, theoretical as well as practical implications and challenges for nonmarket strategy research.

5.1 Methodological implications and challenges

From a methodological perspective, a number of challenges can be identified. First of all, it can be stated that most empirical studies are focusing on specific types of nonmarket strategies or uncoupled political or social activities. Hence, the majority of papers examine isolated aspects or activities such as corporate social responsibility or corporate lobbying. Both approaches contribute equally to the research field of nonmarket strategies. However, articles bringing together political and social activities to study the complete picture of nonmarket strategies are rather rare. Focusing on partial excerpts comes with the drawback of possibly omitting crucial factors and prematurely attributing findings from one nonmarket activity to another. Apart from that, studies with a restricted research focus might benefit from more specific results and insights. This would in turn further highlight the necessity of scientific literature reviews, such as the paper on hand. Nevertheless, future research needs to empirically address the complexity of nonmarket activities on a political, social and legal level and potential linkages between different strategy types. Furthermore, it would be interesting to analyze whether political and social nonmarket strategies are equally important to corporations (and firm performance). External factors, such as industry structure or corporate environment, might have an impact on the perceived need or importance to implement social or political activities as part of a nonmarket strategy. Advances in this field can help to decrease underspecified research models and at the same time help to increase the current degree of generality in empirical studies. The call for more integrated studies becomes particularly evident on the basis of nonmarket strategy typologies (e.g. Puck et al. 2013). As an example, the information strategy or the financial incentive strategy can target both social and political actors at the same time. Therefore, on the basis of actual strategic nonmarket behavior, the borders between political and social strategies blur.

Another methodological challenge emerges in research stream 3–4. A broad variety of indicators is applied to measure the impact of nonmarket strategies on firm performance. Studies vary in terms of the analyzed type of nonmarket strategy, underlying activities as well as the applied indicator to measure firm performance. Accordingly, we identify controversial results: while some scholars affirm a positive impact of nonmarket strategies on firm performance others state that no impact is verifiable. We further identified articles pointing out that nonmarket strategies might even have a negative impact on firm performance in the long-run. One explanation for those opposing results can certainly be seen in the variety of used indicators to measure firm performance such as return on assets, return on sales, market share, market value or capacity utilization. Research models rarely address this issue, possibly due to the preference of data availability over data relevance (Goranova and Ryan 2014). Further empirical research is needed to investigate these discrepancies more thoroughly and to figure out whether differences in existing findings can be traced back to differences in applied indicators or observed activities. However, it is also questionable whether organizational performance research (in general) is losing its “raison d’être“. Several methodological problems such as the key informant bias, endogeneity, simultaneity, heterogeneity, regression-to-the-mean-problem, or survival bias complicate the development of causal structures (March and Sutton 1997). Mintzberg criticized that the unsuccessfulness of the success factor research lies in its essentially simple quantitative design that makes it possible to state “you never even had to leave your office at university. And that meant you never had to face all the distortions inherent in such research.” (Mintzberg 1994, p. 93). Hence, to find out more about the impact of nonmarket strategies on firm performance, detailed qualitative case studies need to be applied. Gathering deep insights into single cases can help to find out more about complex structures and dynamic links between performance (treated as the dependent variable) and several interacting independent variables (with nonmarket strategies only as one of them).

5.2 Theoretical implications and challenges

Within the literature review we outlined theoretical controversies in terms of understanding and conceptualizing nonmarket strategies as well as on the question of how to integrate market and nonmarket strategies. We aim to address these issues in the following.

5.2.1 Activities and strategies

A first observation and theoretical challenge refers to the above-mentioned distinction between nonmarket strategies and nonmarket activities in current research. Reviewing the articles from the angle of a strategy researcher, it appears that several studies regard nonmarket activities as ‘strategies’ as soon as these activities are perceived as important for whatever reason. However, in strategy research it is established practice to distinguish strategies from a stream of other activities that are performed within corporations. For instance: (1) at the lowest level, a single nonmarket activity can retain the character of a strategy if this activity creates a success potential. A foreign market entry accompanied by a lobbying activity may create an entry barrier for followers and can therefore be regarded as strategic (maneuver). As explained before, most nonmarket strategy research follows this ‘strategy as activity’ view. However, at least two further ‘levels’ of nonmarket strategies may be observed: (2) sometimes a consistency in nonmarket behavior may occur in the course of time that can reveal a higher level of nonmarket strategic behavior. As an example, it could be a result of empirical analyses that a firm always accompanies foreign market entries with lobbying initiatives—its nonmarket behavior becomes consistent. (3) Finally, some firms may develop guidelines or plans how to deal with nonmarket situations (Mintzberg 1979; Mintzberg and Waters 1985; Porter 1996; Whittington 2001). A firm may develop a formal nonmarket strategy plan that prescribes to accompany foreign market entries with lobbying activities. As opposed to example (2) this firm not only behaves in a consistent way but formulates an ex-ante guideline how to act strategically in future situations. Furthermore, this ex-ante plan does not necessarily have to be formally adopted but can be effective by means of a shared understanding (orientation) of top management team members. The fact that current nonmarket strategy research disperses with these notions is critical because it denies access to important research questions. For example, it will be important to examine whether companies do have a strategic plan or orientation towards nonmarket issues that guide their behavior or if they only pursue single strategic maneuvers. As a consequence, research will not only be able to describe the content of nonmarket strategies but to further reflect on different developmental levels.

The distinction between single actions and strategic orientations is important not only because they portray the understanding of “strategy” quite differently, but also because of a dynamic link between both. On the one hand, strategic nonmarket orientations will frequently guide companies to conduct specific nonmarket maneuvers. A company may develop strategic nonmarket plans that serve as facilitators as well as restrictors for certain maneuvers. However, on the other hand, strategic orientations may also emerge as a result of an ongoing process of single strategic maneuvers, if the management starts reflecting on these (Wrona and Ladwig 2015). Drawing on this perspective, current nonmarket strategy research remains too shallow due to a disregard of important dynamics and the role of nonmarket strategic orientations. As an example, it would be an interesting research question, whether nonmarket maneuvers of companies materialize as an implementation of a strategic orientation towards the nonmarket environment or if certain nonmarket maneuvers are developed separately. The former would indicate a higher development level in nonmarket behavior. Currently, this empirical question is completely neglected in nonmarket strategy research. Summarizing, nonmarket strategy research will significantly benefit from a stronger embedding within strategic management concepts and theories. A repositioning of the research field is recommended and leaves space for future research.

5.2.2 Integration of market and nonmarket strategy

The literature review demonstrates that so far little attention has been paid to the question of how to integrate market and nonmarket strategies. Certainly, the importance of this topic does not primarily arise from its relation to firm performance. If nonmarket strategy research wants to refrain from studying isolated maneuvers, ‘integration’ is an important research field because it sheds light on the question of how firms can coordinate and align market and nonmarket activities. From this point of view, integration also means that nonmarket strategies must be regarded as an equivalent part of the strategic behavior of a firm and are able to influence and be influenced by market strategies. Although Baron already highlighted the importance of an integrated strategy (Baron 1995, 2001, 2013), up to now there are only few publications addressing this issue. Within those, as a consensus it can be hold that the integration of both strategies is regarded as crucial, since it is supposed to have a significant impact on overall business success. However, it is not finally settled what ‘integration’ exactly means, how it takes place and who bears (or should bear) the responsibility. Furthermore, a detailed outline of possible integration mechanisms is missing. Organizational research unveiled several integration mechanisms that can be used to coordinate within organizations, such as personal, structural or technocratic coordination (e.g. Khandwalla 1972). Even though, some scholars highlight detached formal or informal tools, an in-depth systematization of integration mechanisms offers potential for future research. Additionally, the question of how responsibilities are distributed during strategy integration is of particular interest and leaves space for future research. Here, special attention should be paid to multinational corporations with subsidiaries acting in diverse market and nonmarket environments. Regional knowledge of local managers needs to be confronted with hierarchical company structures in order to investigate strategy development and integration. Whether those adjustments are decided centralized or decentralized can also be stated as a prevailing literature gap. As another result, we identify internal obstacles that can hinder the integration process, such as discrepancies between market and nonmarket strategies or substitution effects (Bonardi 2004, 2008). Further empirical investigations are necessary to fully understand these obstacles and to theoretically strengthen the understanding of an integrated strategy.

5.3 Implications for practice

Research on nonmarket strategy has crucial implications for management practice. The findings of the literature review highlight the massive impact of social, political and legal actors on ongoing business procedures and decision-making processes. To address the question of site selection, the management needs to bear in mind dependencies on regional stakeholders and regulatory and institutional conditions. As research stream 2–3 on external determinants highlights, regulation density and stakeholder activism tend to have a substantial impact on corporate nonmarket strategies and business decisions. On these grounds, the examination of antecedents provides useful guidelines for practitioners to gain a thorough understanding on the importance and impact of nonmarket actors and external as well as internal drivers for nonmarket strategies.

A further finding that provides practical implications is the outlined necessity to integrate market and nonmarket strategies. Coordination procedures and integration delegation can support the alignment of an overall firm strategy and promote firm success. Addressing these issues in future empirical studies can strengthen the theoretical understanding of integrated strategies and practically guide companies on how to overcome integration-related obstacles.

6 Conclusion

Our study contributes in many ways to the current research discussion on nonmarket strategy. We systematically display nonmarket strategy research since its early beginnings in 1995 until today and also include subordinate research streams on social and political strategies. This systematic approach and thorough examination of relevant publications enabled us to provide a comprehensive overview of the research field. Via the outlined conceptual framework, we were able to identify relevant research streams that were thereafter applied to scan and evaluate the identified publications. The framework aims to provide a systematic overview and understanding of how and why firms influence social, political and legal stakeholders in order to achieve corporate objectives. It further assists to identify research gaps, as outlined in the previous part of this paper.

Finally, it should be noted that, just as every other literature review, our study is subject to potential limitations. Analyzing literature requires a preceding classification process that demands a thorough categorization, based on specific criteria. As a matter of course, this process underlies the limitation of subjectivity, but was, however, carried out with utmost diligence. Another limitation can be seen in the process of literature selection. It may be possible that important articles in the research field were excluded from the literature search due to the formulated inclusion and exclusion criteria. Taken together, the presented review of empirical findings might be of significant value for nonmarket strategy research in particular because of its integrative character. The highlighted research gaps furthermore indicate that there is significant opportunity to proceed with future nonmarket strategy research.

Notes

Below we are going to speak only of ‘activities’ for the sake of simplicity.

Within this paper firm performance is understood as a term of wide comprehension. Since the reviewed articles refer to economic value or economic performance based on varying indicators, they shall be summarized under the term firm performance. However, differences within the studies shall be highlighted whenever necessary.

References

Akbar YH, Kisilowski M (2015) Managerial agency, risk, and strategic posture: nonmarket strategies in the transitional core and periphery. Int Bus Rev 24:984–996

Baron DP (1995) Integrated strategy: market and nonmarket components. Calif Manag Rev 37:47–65

Baron DP (1997a) Integrated strategy and international trade disputes: the Kodak-Fujifilm case. J Econ Manag Strat 6:291–346

Baron DP (1997b) Integrated strategy, trade policy, and global competition. Calif Manag Rev 39:145–169

Baron DP (2001) Private politics, corporate social responsibility, and integrated strategy. J Econ Manag Strat 10:7–45

Baron DP (2013) Business and its environment, vol 7. Pearson Education, New Jersey

Bartlett CA, Ghoshal S (1986) Tap your subsidiaries for global reach. Harv Bus Rev 64:87–94

Beddewela E, Fairbrass J (2016) Seeking legitimacy through CSR: institutional pressures and corporate responses of multinationals in Sri Lanka. J Bus Ethics 136(3):503–522

Blumentritt TP (2003) Foreign subsidiaries’ government affairs activities: the influence of managers and resources. Bus Soc 42:202–233

Bonardi JP (2004) Global political strategies in deregulated industries: the asymmetric behaviors of former monopolies. Strateg Manag J 25:101–120

Bonardi JP (2008) The internal limits to firms’ nonmarket activities. Eur Manag Rev 5:165–174

Bonardi JP, Holburn GLF, Van den Bergh RG (2006) Nonmarket strategy performance. evidence from US. Electr Util Acad Manag J 49:1209–1228

Breitinger D, Bonardi J-P (2016) Private politics daily: what makes firms the target of internet/media criticism? An empirical investigation of firm, industry and institutional factors. Adv Strat Manag 34:331–363

Brown JL, Drake K, Wellman L (2015) The benefits of a relational approach to corporate political activity: evidence from political contributions to tax policymakers. Am Account Assoc 37:69–102

Chakravarthy BS, Doz Y (1992) Strategy process research: focusing on corporate self-renewal. Strat Manag J 13:5–14

Chalmers I, Enkin M, Keirse MJNC (1993) Systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials. Milbank Q 71:411–437