Abstract

Business model change processes are a still underresearched phenomenon. Especially barriers to business model change and in this context path dependence of business models lack a deeper understanding. We address this issue by examining business model change processes of manufacturing firms that pursue service transition against the background of a multiple-case study. The contribution of our paper is twofold: (1) We show how business model change processes take place in detail. In doing so, we considerably enhance business model literature that employs a processual perspective on business model change. (2) Our findings allow for a new perspective on business model change as we provide empirical evidence that path dependence needs to be considered in this context. We are able to identify determinants and mechanisms that influence to which extent path dependence affects business model change processes. Hence, we enrich business model literature by applying the path dependence concept on a business model level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

During the last decade business models have become an increasingly important topic for research (Schneider and Spieth 2013; Zott et al. 2011) as well as for managerial practice (IBM Global Business Services 2006; Lindgardt et al. 2009). Quickly changing ecosystem conditions (Casadesus-Masanell and Zhu 2013; Teece 2010) that are triggered by technological innovation (Chesbrough 2010; Magretta 2002; Teece 2010) force firms more and more to think outside the box and following to redesign their way of doing business. In this context, adjusting internal structures and processes is not enough as effectively dealing with these ecosystem changes also calls for redefining firm-external relations (Amit and Zott 2012; Chesbrough 2011). Therefore, firms are challenged to adjust their business model in order to be able to benefit from new market conditions.

However, changing the business model may not be an easy task for firms as the change process is likely to be affected by the extant business model that influences possible transformation patterns (McGrath 2010). In other words: managerial decisions made in the past very often still cast a shadow on the firms’ scope of action related to business model change (Chesbrough and Rosenbloom 2002; DaSilva and Trkman 2014). Nevertheless, by now this aspect has not been researched sufficiently. Research (e.g. Cavalcante et al. 2011; McGrath 2010) only mentions path dependence as side aspect and especially fails to define what path dependence of business model change really is. We aim at closing this research gap by explicitly analyzing business model change against the background of path dependence.

Our research is embedded in a manufacturing industry setting as we assume that business model change follows different rules in different industries. Especially manufacturing firms are recently challenged by a need to change their business model. Literature (e.g. Kindström et al. 2013; Ulaga and Loveland 2014) points to an ecosystem-driven need for manufacturing firms to change their value creation processes by shifting their traditional product focus in the direction of a more service-oriented perspective on how to do business. This so-called service transition results in a need for business model change. Researchers already refer to well-known firms such as Rolls Royce (e.g. Neely 2008; Ng et al. 2012), IBM (e.g. Amit and Zott 2012; Chesbrough 2007, 2011), or Xerox (e.g. Chesbrough 2007; Chesbrough and Rosenbloom 2002) in order to exemplify the relevance of business model change for manufacturing firms that undergo a service transition process. Therefore, a manufacturing industry setting is especially suitable to analyze business model change processes in detail.

Furthermore, according to literature (Gebauer et al. 2005; Ulaga and Reinartz 2011) only a few manufacturing firms are able to benefit from implementing service-focused strategies and following from redesigning their business models. Business model change is often a process that is driven by experimentation and trial-and-error learning (Khanagha et al. 2014; McGrath 2010; Sosna et al. 2010). Moreover, experimenting with new business model designs requires resources as implementing a new business model design is costly and time-consuming (Bohnsack et al. 2014; Sosna et al. 2010). Researchers (e.g. Chesbrough 2010; Chesbrough and Rosenbloom 2002) emphasize that cognitive constraints of managers prevent firms from changing their business models that have been successful in the past and lead these firms to being trapped in inappropriate business model designs. Manufacturing firms very often mainly exploit existing capabilities (Ulaga and Reinartz 2011) although they need to develop new service-related capabilities to follow a service transition (Neely 2008; Neu and Brown 2005). All these aspects point to path dependence as determinant of business model change in the context of manufacturing firms and therefore also support the choice of our research setting.

Against this background we ask: (1) How do manufacturing firms change their business model in order to respond to challenges caused by service transition? (2) How does path dependence affect the business model change process of manufacturing firms in this context?

In doing so, we follow a call by Demil et al. (2015) who explicitly point to the need for further research focusing on business model change processes in established firms. Moreover, our research also aims at answering the question “[…] how path dependency constrains future changes in a business model” raised by DaSilva and Trkman (2014; p. 387). The importance of this question is also emphasized by George and Bock (2011, p. 85) who state that “[…] questions of business model path dependence remain unresolved”. We answer these questions and provide empirically grounded insights how path dependence influences business model change processes of manufacturing firms in the context of service transition.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. We base our research on a commensurable theoretical framework that is enrooted in the well-established business model conceptualization by Amit and Zott (2001) and enhanced by insights drawn from the path dependence approach (Sydow et al. 2009; Vergne and Durand 2011). The elements of this framework are explained in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3, we present research propositions that are thoroughly developed out of our theoretical background. The propositions depict an extension of our basic research questions and therefore allow us to analyze path dependent business model change processes triggered by service transition in a more detailed way. Section 4 is dedicated to the explanation of our research methodology. Our research is based on a multiple-case study approach; the design of our study follows suggestions by Yin (2009). The findings of this multiple-case study are highlighted in Sect. 5 and discussed against the background of existing literature in Sect. 6. The main insights of our study and their implications for research and business practice as well as limitations of our research are presented in Sect. 7.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Business model concept and business model change

Business model research was triggered by the rise of e-businesses during the internet boom in the late 1990s. Since then, the importance of this research stream considerably increased and is still growing (DaSilva and Trkman 2014; Morris et al. 2005; Osterwalder et al. 2005; Zott et al. 2011). Despite the increasing number of publications, there is by now neither a clear definition of a business model itself (DaSilva and Trkman 2014; Zott et al. 2011), nor of business model change (Bucherer et al. 2012; Spieth et al. 2014) available. In general, business models can be understood as a blueprint or a framework that helps to explain how value is created, delivered, and captured by the focal firm and its network partners (e.g. Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010; Demil and Lecocq 2010; Morris et al. 2005; Teece 2010; Zott and Amit 2010, 2013). However, researchers emphasize different roles of business models (see Spieth et al. 2014 for an overview). Therefore, it is important to explain our understanding of the business model concept in detail.

In this paper, we follow Zott and Amit (2010, see also Amit and Zott 2001; Zott and Amit 2013; Zott et al. 2011) who regard the business model concept as a new unit of analysis that is conceptualized “[…] as a system of interdependent activities that transcends the focal firm and spans its boundaries” (Zott and Amit 2010, p. 216). Hence, the business model concept does not only focus on firm-centric activities, but also considers how the focal firm is embedded in its business ecosystem (Zott and Amit 2010, 2013). According to Amit and Zott (2001, 2012; see also Zott and Amit 2010), a business model consists of the three design elements content, structure, and governance. Content refers to the activities that are performed within the activity system. This involves the exchange of products, services, and information between the various network partners as well as the capabilities required to facilitate this exchange. Next, structure depicts the linkages and the sequencing of the system’s activities. Furthermore, aspects such as network size or the flexibility and adaptability of the system are explained. Last, governance describes by whom the activities are performed as well as the locus and nature of control of transactions within the activity system. When configuring these three design elements, firms can make use of four different so-called design themes that depict the value drivers of a firm’s business model. First, a novelty-centered design involves an innovative (new to the market) conceptualization of the business model elements content, structure, and governance. Next, a lock-in-centered design comprises a business model conceptualization that aims at achieving a high degree of customer and other network partners’ retention. Third, by designing complementarities-centered business models firms can make use of value-enhancing effects of interdependent activities. Last, the value driver of efficiency-centered designs refers to the reduction of transaction costs.

The initial paper on business models by Amit and Zott (2001) is deeply embedded in an e-business setting. However, the resulting business model conceptualization can be easily transferred to the context of manufacturing firms as its theoretical foundation is built upon well-established theories and approaches that predate the e-business era such as transaction cost economics (e.g. Williamson 1975), network theory (e.g. Katz and Shapiro 1985), resource-based view (Barney 1991; Wernerfelt 1984) or Schumpeterian innovation (Schumpeter 1934). This cross-theoretical perspective also distinguishes Amit and Zott’s (2001) business model conceptualization from other business model conceptualizations (Morris et al. 2005). As the business model concept stems from managerial practice, researchers often fail to explicitly explain the theoretical underpinnings of the concept (George and Bock 2011; Schneider and Spieth 2013). Therefore, we are sure that employing Amit and Zott’s (2001) theoretically well-defined business model conceptualization is appropriate in the context of our research.

Nevertheless, business models are not static. They need to be adjusted over time to be viable especially in the context of changing environmental conditions (Amit and Zott 2012; Bucherer et al. 2012; McGrath 2010). Hence, a transformational approach is required that regards the business model as a tool to handle organizational change (Demil and Lecocq 2010). However, researchers refer to different terms which are used inconsistently and interchangeably in this context. When describing changes of a firm’s business model, they for instance refer to business model innovation (e.g. Amit and Zott 2012; Chesbrough 2007; Cortimiglia et al. 2015), business model evolution (e.g. Bohnsack et al. 2014; Demil and Lecocq 2010; Doz and Kosonen 2010), or business model experimentation (McGrath 2010; Sosna et al. 2010), just to name a few. While business model innovation is mainly seen as the introduction of a fundamentally different, game-changing business model to an existing industry (e.g. Comes and Berniker 2008; Markides 2006; Snihur and Zott 2013), some researchers emphasize that a continuous process of change that leads to business models that are new to the firm also requires further analysis (e.g. Bucherer et al. 2012; Schneider and Spieth 2013). In this paper, we clearly distinguish between business model innovation that leads to a radically different business model that is new to the market and business model transformation that involves changes in a firm’s business model in general. In this context, researchers (e.g. Bucherer et al. 2012; Chesbrough 2010) emphasize that product innovation or process innovation may lead to business model transformation if adjustments in the business model are necessary to benefit from these innovation types. However, Cavalcante et al. (2011) argue that not all organizational changes necessarily entail changes in the business model as otherwise the business model concept as a unit of analysis would be obsolete. Hence, we define business model transformation as any changes or refinements that fundamentally affect at least one design element of a firm’s extant business model and thus the development of a business model design that is new to the firm. Furthermore, in contrast to Bucherer et al. (2012) who only consider deliberate changes in their definition, we follow Demil and Lecocq (2010) who argue that changes in the business model can be both, intended and emerging.

2.2 Path dependence

The path dependence concept originates from evolutionary economics (Nelson and Winter 1982) and has widely been discussed in the context of technology development and economic history (e.g. Arthur 1989, 1994; David 1985; Dosi 1982). Later, researchers in the realm of institutional economics (e.g. North 1990) adopted the concept. Only recently it increasingly gains interest from an organizational or managerial point of view (e.g. Sydow et al. 2009; van Driel and Dolfsma 2009; Vergne and Durand 2011). Defining path dependence rather broadly, research often comprises different types of organizational or strategic rigidities (Koch 2008) or various “‘history matters’ kinds of theoretical constructs” (Vergne and Durand 2010, p. 737). In contrast, a more narrow definition of path dependence is necessary in order to analyze path dependent processes in detail (Vergne and Durand 2010). The framework of organizational path dependence developed by Sydow et al. (2009; see also Schreyögg and Sydow 2011) employs such a precise understanding. Furthermore, it is basically in line with Vergne and Durand’s (2010, 2011) perspective on path dependence. To avoid a fuzzy use of the term “path dependence” in the context of researching business model change, we explicitly make use of the path dependence concept and transfer this concept from an originally organizational level to a business model level. In their framework, Sydow et al. (2009; see also Schreyögg and Sydow 2011) describe three phases of path dependent processes. Similarly, Vergne and Durand (2010) define a particular process as path dependent if specific conditions are met. First of all, Sydow et al. (2009) refer to the so-called preformation phase in which the manager’s scope of action is still rather broad, but the effect of particular strategic choices cannot be determined in advance. Vergne and Durand (2010, 2011) also argue that organizational path dependence is triggered by contingent and unpredictable events. The contingent effects of managerial choices then trigger self-reinforcing mechanisms that narrow possible trajectories of future decisions (Sydow et al. 2009; Vergne and Durand 2011). The “critical juncture” at which the firm enters the dynamics of these self-reinforcing mechanisms also sets off the second phase—the formation phase of path dependence (Sydow et al. 2009). Due to dominant action patters that rise in this phase, alternative choices become less attractive. As a consequence, a particular path emerges in which managerial discretion increasingly narrows (Schreyögg and Sydow 2011; Sydow et al. 2009). Self-reinforcing effects further restrict managerial discretion until they finally lead to the third and last phase of path dependence. In this so-called lock-in phase the organization is trapped in a situation in which the managerial scope of action is so limited that endogenous change becomes difficult. Preferred action patterns that are deeply embedded in organizational practice emerge. Usually, exogenous factors are necessary to allow the organization to leave this narrow corridor of strategic choices (Vergne and Durand 2010). Although being trapped in a particular path is not necessarily harmful per se (Vergne and Durand 2011), the inflexibility normally leads to inefficient or inferior solutions as the organization is not able to react to changing conditions and to adopt more efficient options that may emerge over time (Sydow et al. 2009).

3 Proposition development

Traditional manufacturing firms employ a business model that is strongly product-focused and embedded in the firm’s product-based dominant logic (Vargo and Lusch 2004). This “manufacturing orientation” (Bowen et al. 1989, p. 75) that stems from the “mainstream management thinking from the industrial era” (Grönroos 1990, p. 8) is characterized by capital intensive production of tangible outputs in closed systems that allow for a high degree of standardization and an exploitation of economies of scale. Challenged by changing ecosystem conditions that lead to a higher demand for service, manufacturing firms are in a need to rethink and reorganize value creation processes (Lerch 2014; Ramirez 1999) and thus to adjust their business models. However, not all firms recognize the need for business model change at the same time. An efficiency-centered business model design (Amit and Zott 2001) is usually the predominant solution for manufacturing firms that do not actively engage in enhancing service offerings to respond to changing ecosystem conditions. Therefore, to detail research question (1) we propose:

Proposition 1

Manufacturing firms that do not pursue service transition primarily focus on an efficiency-centered business model design.

Persistence in a specific business model design choice is not necessarily the result of a deliberate decision. According to path dependence literature (Sydow et al. 2009; Vergne and Durand 2011), persistence is very often the result of self-reinforcing effects. A traditional product-based business logic seems to be the first and most serious barrier that hinders manufacturing firms to change their business model to allow for a more service-oriented way of doing business (Kindström et al. 2013; Matthyssens and Vandenbempt 2008). Furthermore, enhancing service offerings very often leads to a cost increase that is not accompanied by a respective increase of returns (Gebauer et al. 2005). Hence, although managers of manufacturing firms might recognize the growing importance of service offerings, a time lag with respect to profitability may lead managers to stick to the extant efficiency-centered business model design. Additionally, Schreyögg and Kliesch-Eberl (2007) highlight the important role core competences play as a trigger of path dependence. This has to be regarded related to manufacturing firms that are confronted with service transition challenges as their core competences are usually product-based and can therefore not or not easily be transferred to a service setting. Against this background and specifying research question (2), we state:

Proposition 2

Self-reinforcing effects prevent manufacturing firms from changing their business model and force them to persist in an efficiency-centered business model design.

A precondition for business model change is that manufacturing firms are able to break out of their dominant, product-based business logic in order to consider new ways of value creation (Matthyssens et al. 2006). Breaking path dependence requires according to Sydow et al. (2009) factors that are to a certain degree exogenous in nature. Examples of these factors are shocks or crises that severely threaten the firm, organizational demographic changes, or unintended consequences of organizational decisions triggered by changes in the business ecosystem. In the context of manufacturing firms, a commoditization of products (Kowalkowski et al. 2012) and the fact that customers actively seek for service-enhanced solutions (Jaakkola and Hakanen 2013) can be regarded as external triggers to break free from a path dependent business model design. However, by now path-breaking mechanisms in the context of business model change are widely underresearched. Therefore, path-breaking mechanisms need to be examined when trying to understand the role of path dependence in business model change processes. Hence, to illustrate research question (2) in more detail, we propose:

Proposition 3

Path-breaking mechanisms enable manufacturing firms to overcome obstacles to business model change.

When integrating service offerings into the traditionally product-based portfolio of offerings, manufacturing firms are challenged by rising transaction costs (Bowen and Jones 1986) that force them to abandon their traditional efficiency-centered thinking (Grönroos and Ojasalo 2004). As a consequence, an efficiency-centered business model design is no longer suitable for manufacturing firms. Instead, we assume that manufacturing firms need to find new ways to configurate the content element, structure element, and governance element of their business model and thus to thrive for implementing a novelty-centered business model design. Changing all three business model elements is necessary in the context of service transition (Clauß et al. 2014). Implementing service offerings does not only affect the content element of a business model. It also calls for the development of new organizational processes and structures (Kindström et al. 2013; Neely 2008) as very often new network partners need to be integrated and deep customer-specific knowledge needs to be acquired (Hakanen et al. 2014) in order to allow for facilitating the provision of service (Storbacka et al. 2013). This also affects the governance element of the business model as integrating network partners goes along with a need to develop new ways to monitor and control network relations (Matthyssens and Vandenbempt 2008).

However, radical business model innovation seems to be unfeasible for many manufacturing firms as studies (Gebauer and Fleisch 2007; Kowalkowski et al. 2012) show that the pursuit of service-related opportunities very often happens stepwise. Resources (Fang et al. 2008) as well as managerial attention (Gebauer 2009) are limited which may decelerate business model change. In this context, two different alternative business model change processes are possible. Firms can either pursue a complementarities-centered business model design or a lock-in-centered business model design in a first step on their way to finally implementing a novelty-centered business design. This choice determines the order in which the business model elements content, structure, and governance need to be changed. When striving for a complementarities-centered business model design, firms start to offer services that are strongly tied to core products by leveraging existing resources and capabilities (Ulaga and Reinartz 2011). Over time, they are able to develop new service-related capabilities on their own and to provide advanced services that are linked to their products (Salonen 2011) or services that support the customer’s value creation activities (Copani 2014; Mathieu 2001). Hence, in order to benefit from a complementarities-centered business model design, the type of offerings as well as resources and capabilities—and thus the content element (Amit and Zott 2001)—are mainly affected. To specify research question (1), we therefore propose:

Proposition 4a

Manufacturing firms that employ a stepwise approach to service transition by initially implementing a complementarities-centered business model design predominantly change the content element of their business model.

However, firms may decide not to change the content element of their business model in a first step, but to put more emphasis on a stronger customer-centered perspective on value creation (Priem 2007). These firms pursue service transition by implementing a lock-in-centered business model design in a first step. In doing so, they have to change the structure element as outside-in processes such as market sensing or channel bonding (Day 1994) need to complement the traditional closed-system perspective of manufacturing firms (Grönroos and Ojasalo 2004). Furthermore, these firms are also in a need to change governance mechanisms as collaborative, relational exchange replaces rather anonymous, automated transactions (Day 2000). Again specifying research question (1), we propose:

Proposition 4b

Manufacturing firms that employ a stepwise approach to service transition by initially implementing a lock-in-centered business model design predominantly change the structure element and the governance element of their business model.

As any kind of change process, innovating or transforming the business model is a complex and highly challenging task (Mezger 2014; Smith et al. 2010). Due to its complexity, business model change necessitates several interdependent decisions. To reduce complexity, managers very often make use of prior experience and decide in favor of solutions they are familiar with (Gavetti and Levinthal 2000; Maitland and Sammartino 2014). The basic mechanisms that determine these decision making processes are invisible and may represent patterns that trigger path dependence. This is in line with Sydow et al. (2009) and explains why some researchers focusing on business model innovation (e.g. Bohnsack et al. 2014; McGrath 2010) point to the possibility that the process of changing a business model may be path dependent. Especially the stepwise approach toward implementing a novelty-centered business model design is susceptible to the influence of path dependence as decisions that lead to implementing a complementarities-centered or a lock-in-centered business model design in the first step may not be in line with decisions necessary to implement a novelty-centered business model design. Garud et al. (2010) highlight that such purposeful decisions may narrow managerial choices and thus represent triggering events that can initiate the emergence of path dependence. Although Vergne and Durand (2010) as well as Arthur (1989) argue that triggering events are usually contingent and non-purposive in nature, this does not contradict our reasoning as pursuing business model change can be the result of a series of deliberate and emergent decisions (Demil and Lecocq 2010). Triggering events narrow managerial discretion (Sydow et al. 2009). However, they do not cause firms to persist in a complementarities-centered or in a lock-in-centered business model design. Following research question (2), we argue:

Proposition 5a

Triggering events decelerate the implementation of a novelty-centered business model design by manufacturing firms.

Apart from triggering events, path dependent persistence in a business model design requires the existence of self-reinforcing effects (Sydow et al. 2009; Vergne and Durand 2011). Thus, to detail research question (2), we propose:

Proposition 5b

Self-reinforcing effects cause manufacturing firms to persist either in a complementarities-centered business model design or a lock-in-centered business model design.

We also need to take into account that manufacturing firms could be willing and able to change all three business model elements at once by developing a value creation logic that breaks the “existing rules of the game” (Matthyssens and Vandenbembt 2008, p. 326). In this case, the business model change process cannot be affected by path dependence. To cover this possibility and to specify research question (1), we propose:

Proposition 6

Manufacturing firms that pursue service transition by directly implementing a novelty-centered business model design change the content element, structure element, and governance element of their business model.

4 Methodology

4.1 Benefits of case study research

Rigorous empirical research on business models that goes beyond single-case studies is still rare (Demil et al. 2015). Business model change processes are usually fuzzy (Dimitriev et al. 2014). Hence, a research approach is necessary that allows for contextualization (Welch et al. 2011). Against this background, we decided for a multiple-case study approach as such an approach is especially suitable in a complex and novel research context (Orum et al. 1991; Wright et al. 1988) such as business model change. Moreover, a qualitative research approach does not only seem to be appropriate in the context of research on business model change processes, but also when considering path dependence. Although by now there is still no consensus with respect to methodological issues when it comes to analyzing and testing path dependence (Dobusch and Kapeller 2013), Sydow et al. (2009) point out that studying path dependence requires a research design that allows for a detailed analysis of underlying social mechanisms that lead to path dependence. Therefore, case study research is especially appropriate as it allows gathering rich data (Yin 2009) and helps to provide an in-depth understanding of processes within an organization (Bluhm et al. 2011). Furthermore, case studies are often used to gain insights on specific managerial problems (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007).

In contrast, Vergne and Durand (2010) argue that case studies are not appropriate to analyze path dependence and instead recommend controlled research designs such as simulations or experiments. However, controlled research designs are based on predetermined scenarios that neither go along with Dimitriev et al.’s (2014) reasoning in the context of business model research, nor with Sydow et al.’s (2009) suggestions related to path dependence research. As Garud et al. (2010) already emphasize, the “imagined worlds” of controlled research designs cannot depict the contingencies that influence processes in real world situations. Hence, with controlled research settings we are not able to examine the challenges manufacturing firms experience when pursuing service transition-triggered business model change and the possible role path dependence plays in this context. Moreover, prior research in the realm of business model change as well as path dependence often uses case studies (e.g. Bohnsack et al. 2014; Khanagha et al. 2014; Koch 2008, 2011; van Driel and Dolfsma 2009) and shows that a case study can be utilized to gain valuable insights into this research context.

We decided to follow a case study approach that is explanatory in nature as we aim at building upon the theoretical framework developed by Sydow et al. (2009) to analyze path dependence in the context of business model change. Following a grounded theory approach (e.g. Glaser 1992; Glaser and Strauss 1967) and thus dismissing prior research—as it is usually done in the context of grounded theory (Langley 1999)—is not appropriate. We regard case studies as natural experiments that help to explain and modify existing theory (Yin 2009). In this context, it is important to understand that our objective is not to test the propositions we developed out of theory—they are not formulated in a way that allows falsifying them. Instead, the propositions are an extension of our basic research questions and thus help us to guide our case analysis in the right direction and to extend and enhance existing theory (Yin 2009).

4.2 Research setting and data collection

For our empirical analysis we had to identify case firms that are (a) affected by service-related ecosystem changes and (b) have the opportunity to respond to these changes by adjusting their business models. Hence, we chose firms operating in mechanical engineering or very similar industries as firms belonging to these mature industries are said to benefit in particular from service-related business model change (Kowalkowski et al. 2012; Oliva and Kallenberg 2003). Following theoretical sampling (Eisenhardt 1989; Eisenhard and Graebner 2007; see also Yin 2009) we selected case firms based on information we gathered from firm websites. In detail, case firms were chosen based on the following criteria: (1) the case firm’s core business needed to be product-based at least before service transition had eventually occurred; (2) the case firm needed to be characterized by one business model as case firms with parallel, competing business models (Markides and Charitou 2004) are difficult to compare. Therefore, we decided to select case firms with no more than 500 employees; and (3) we needed to get access to information on the firm and to a competent key informant (Kumar et al. 1993) willing to participate in an interview. Additionally, all our case firms are German capital-based firms that operate in a business-to-business setting. The focus on these specific selection criteria allows for controlling extraneous variation (Eisenhardt 1989). A description of the case firms is presented in Table 1.

We base our analysis on two data sources. First, we conducted semi-structured interviews with CEOs. This approach, on the one hand, allows us to benefit from open answers that provide deeper insights into the “lived experience” of our interviewees (Gioia et al. 2013). On the other hand, it also enabled us to guide the interviews and thus link them to our developed propositions (Yin 2009). Following suggestions by Yin (2009), we developed an interview guideline that considers our research propositions—and in this context especially the business model conceptualization by Amit and Zott (2001) and the research suggestions by Sydow et al. (2009). Related to the business model, we did not directly ask for the business model as a whole but for its design elements content (e.g. Which products and services do you currently offer?; Which resources and capabilities are necessary to provide your portfolio of offerings?), structure (e.g. How are customers and other network partners integrated into value creation processes?; Please specify the main network ties you consider essential for value creation processes?), and governance (e.g. Which control mechanisms do you employ to safeguard value creation processes?; How do you incentivize customers and other network partners to contribute to value creation?). Furthermore, we asked the interviewees whether the business model elements have been stable or experienced change over time. If the interviewees reported change, we asked them to explicitly describe the change process by naming and explaining critical incidents. When no change was reported, we further investigated the reasons for this persistence. This was necessary to be able to identify strategic persistence, self-reinforcing effects and triggering events—the three aspects Sydow et al. (2009) highlight as being crucial in the context of path dependence research.

The interviews were conducted by two researchers at the firm locations as suggested by Eisenhardt (1989) between April 2014 and July 2014 and lasted on average about 90 min each. We carefully transcribed the interviews and sent the transcripts back to our informants for a double-check to prevent misunderstandings. Data from firm reports, press releases, websites, or additional information provided by our informants represents our second data source. The additional information gathered was used for data triangulation (Yin 2009). This was necessary to enhance the validity of our study (Gibbert et al. 2008) as retrospective reports might be biased due to the CEOs’ individual perception of the past (Golden 1992; Huber and Power 1985). An accurate description of historical events is especially in the context of path dependence research a necessary precondition (Sydow et al. 2009). To protect informants’ interests we promised anonymity (Gioia et al. 2013). Therefore, we will present the collected case data without mentioning firms by name.

4.3 Data analysis

To analyze our data, we first developed case histories of each case firm by synthesizing data from both data sources in order to generate a rich account (Eisenhardt 1989; Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007). These write-ups included reduced data, selected quotes as well as tables showing timelines and key facts. We then divided our case analysis in two parts. First, we examined each case individually. Our propositions helped us to organize this within-case analysis (Yin 2009). We analyzed the current business model elements of each case firm as well as the events that led to the particular configuration of the case firm’s business model. We used pattern matching (Trochim 1989) and explanation building techniques (Yin 2009) to compare empirical data with our theoretical assumptions. Only in a second step after all individual case histories were finished, we conducted a cross-case analysis. This second type of analysis enabled us to compare identified patterns across cases and allowed us to evaluate our propositions and gain additional insights. In doing so, we followed Eisenhardt (1989) who suggests comparing pairs of case firms for differences and similarities in an iterative process. Charts and tables helped us to systematically match and contrast data from different cases.

The authors conducted this data analysis process independently in order to ensure data reliability. The emerging results from the within-case analysis and later from the cross-case analysis were then compared. The patterns independently identified by the authors fully matched. As in no instance a conflict between the two authors’ interpretations emerged, the identified patters can be regarded as reliable. Furthermore, we reexamined the original interview transcripts and archival data in order to ensure that our results are consistent with the original data sources. Additionally, we discussed emerging results of the within-case analysis with some of our informants to get additional feedback regarding the accuracy of our findings.

5 Findings

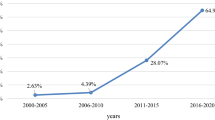

By making use of the propositions developed in Sect. 3 as guiding principles for our research (Yin 2009), we first of all analyzed the business model change of each case firm in detail. The results of this within-case analysis are provided in Table 2 (see appendix). The follow-up cross-case analysis allowed us to identify overarching patterns in service transition-triggered business model change of manufacturing firms. We found four development paths that differ in the way how a firm’s business model change process takes place. Figure 1 summarizes the findings of our cross-case analysis.

Our case data provides evidence that all case firms started off with an efficiency-centered business model design. Making use of such a design is mainly a consequence of a product-based business logic that manufacturing firms traditionally employ. The interviewed CEOs told us that their firms experience an enhanced demand for service. However, the CEOs pointed to the fact that reacting to service-related market changes is difficult as established structures, routines as well as a basic understanding of the firm’s way of doing business prevent firms from encompassing business model changes. The CEO of case firm 1, for instance, explained:

“Our expertise in developing high quality machinery dates back to the inception of the firm. We are famous for our products. Suddenly, we also need to offer service. Changing this perspective is difficult.”

This statement points to the relevance of rigidities that trap firms in their initial efficiency-centered business model design. While the development paths II, III, and IV are characterized by case firms that were able to change their initial business model design, a persistence in an efficiency-centered business model design can be observed for development path I (case firms 2, 9, and 13). According to the statements of the CEOs of these case firms, service transition is not regarded as an opportunity. The CEO of case firm 2, for example, told us:

“In the end, customer decisions are price-driven. Therefore, we primarily focus on a cost-efficient production.”

Hence, our case findings are in line with Proposition 1. According to the CEOs of case firms 2 and 9, primarily focusing on efficiency is suitable for these firms in order to exploit existing capabilities in the best possible way.

However, we need to question whether focusing on an efficiency-centered business model design is a deliberate decision. The interview data provides evidence that this decision may also be an emergent one that is caused by path dependence. The CEO of case firm 9 emphasized:

“We know our competitors very well – and they know us. Basically, we are all bound to the same conditions and we all follow the same practices that are established in our area of business.”

This benchmarking perspective prevents case firm 9 from even considering business model change as an opportunity. In this case, the fear of losing legitimacy plays an important role that delimits the firm’s scope of action. Long-established and well-accepted market rules seem to be of special relevance in this context. Firm offerings are to a great extent exchangeable so that competition is based on product prices. On the one hand, the risk of establishing an innovative business model that allows for differentiation is considered as being too high by the CEO of case firm 9. On the other hand, transforming the business model in small steps does according to the CEO of case firm 9 not provide a sufficient competitive advantage in terms of differentiation. Therefore, reducing costs seems to be the only opportunity for case firm 9 to improve the market position. For case firm 2, we see that the scope of action is heavily affected by a strong focus on exploiting existing resources and capabilities. This firm benefits from its resource base and product-related capabilities. Acquiring new resources and capabilities does not stand at the forefront for case firm 2 as according to the CEO making the best out of existing resources and capabilities is considered as the most promising way to ensure market survival. In other words: exploiting an area the firm is already familiar with is seen as being superior to a risky exploration of new opportunities. Path dependence literature (Sydow et al. 2009) classifies these effects as self-reinforcing effects (adaptive expectation effects and learning effects) that trap firms in a specific development path. Therefore, our findings are in line with Proposition 2. Related to development path I this means that these firms are not able to encompass business model change as these self-reinforcing effects act as a blinder to the recognition of business opportunities that are not in the scope of the extant business model. Also being part of development path I, case firm 13 is a special case. In contrast to case firms 2 and 9, case firm 13 is able to think outside the box. This is a result of business succession which allows the firm to discard the blinder of self-reinforcing effects and thus to consider new opportunities. However, this recognition is by now not reflected in a business model change as case firm 13 still struggles with overcoming the deeply enrooted structures and routines of an efficiency-centered business model design. Therefore, case firm 13 is still affected by path dependence and thus still belongs to development path I.

The results related to case firm 13 already point to the importance of path breaking mechanisms in overcoming path dependent business model designs. In line with Proposition 3, we found that business model change is in all case firms triggered by a path-breaking mechanism. However, our case data reveals that different path-breaking mechanisms account for the initiation of business model change. In detail, we identified three main path-breaking mechanisms that are of relevance in the context of service transition-triggered business model change: (1) customer initiatives, (2) business succession, and (3) crisis. Customer initiatives have to be regarded as path-breaking mechanism for our case firms 1 and 5. We understand customer initiatives as a process that is characterized by customers actively approaching a firm and presenting new ideas and demands. Thereby, customers cause the firm to rethink its value proposition. Hence, customer initiatives can serve as a path-breaking mechanism as they represent a new interface with the business ecosystem. The CEO of case firm 5 emphasized:

“Of course, our products represent the main source of revenues. Without products, we cannot offer services. However, recently we realized that customers increasingly demand services and now we also proactively sell services to our customers. With respect to products, we need to wait for the customers to approach us. Regarding services, we are able to generate recurring revenues.”

Hence, customer requests enabled case firms 1 and 5 to recognize new customer needs. Following, the firms were able to transform their business models accordingly and thus to actively pursue service-related opportunities.

Business succession is the second path-breaking mechanism we identified (case firms 4, 8, 12, and 13). When a new CEO with a different background and different experiences takes over, a process of rethinking established practices can be observed. Our case data shows that a new CEO does not hesitate to question the extant, well-established business model even if it is still profitable. The CEO of case firm 4 explained:

“My predecessor was mainly concerned about continuously increasing product quality and optimizing production processes. Customer relations and network-related aspects have never been an issue for him. When I took over the responsibility for the firm I instantly tackled these problems and initiated changes.”

Business succession provides an opportunity to bring an external perspective into a firm. As a consequence, firms are able to proactively implement business model changes before external pressure calls for these changes.

The third main path-breaking mechanism is according to our case data a crisis that threatens firm survival. Such a crisis forces a firm to actively search for new opportunities to overcome the threat of failure. In this situation, the extant business model is proven wrong so that the idea of abandoning the extant business model does not cause much resistance. To ensure firm survival, questioning the whole way of doing business is no longer off-limits. We observed such a reaction to a crisis in case firms 3, 10, and 11. The CEO of case firm 3 explained:

“We knew that if we did not change we would not have survived. Therefore, everything that was taken for granted in the past needed to be questioned.”

Case firm 7 experienced intensified competition. Although this competitive pressure was not critical in terms of firm survival, it has to be regarded as a threat. While both, intensified competition as well as a crisis are a threat that forces firms to react and to change the business model, the identified path-breaking mechanisms customer initiatives and business succession provide the opportunity for business model change.

In general, path-breaking mechanisms result from external developments. This insight holds true for all case firms except for case firm 6. Related to this special case, we were not able to identify an external influence that caused path-breaking. Instead, business model transformation was the unintended consequence of a series of unrelated firm-internal decisions. As business model transformation seems to be a random development in this case, we do not consider this internal progress as a specific category of path-breaking mechanisms in the context of business model change.

Our case data shows that the type of path-breaking mechanism determines how the change of a manufacturing firm’s initial efficiency-centered business model takes place. Firms that experience customer initiatives as path-breaking mechanism follow development path II (see Fig. 1). In this context, case firms (1 and 5) transform their business models in a first step by changing the content element as customers call for enhanced service offerings. Interestingly, while the case firms mainly offer services that support the firms’ products, services that support customers’ actions are not in the main focus of the two case firms. The CEO of case firm 1 explained:

“We only offer services that are directly linked to our core products. Recently, customers increasingly demand services. This is a new source of revenues for us. However, as we are a manufacturing firm, the product business is our main focus.”

Hence, these case firms tie their service business strongly to their product business in order to benefit from economies of scope. Structures and processes that support the product business are also used for the service business. Moreover, products and services are sold to the same group of customers. Therefore, these firms benefit from complementarities and make use of a complementarities-centered business model design. With respect to the business model development path, this insight is in line with our Proposition 4a.

When business succession is the path-breaking mechanism that initiates business model change, our case data shows that case firms (4, 8, 12) transform primarily the structure element and the content element and move toward a lock-in-centered business model design in a first step (development path III, see Fig. 1). The CEO of case firm 4 told us:

“For us it is important to cooperate with our customers and our business partners in order to find new solutions for specific customer problems. On a technological level there is nothing our competitors cannot also do. However, it is the close interaction with our network partners that defines our exceptional position in the market.”

Besides this structural change, case firms 4, 8, and 12 also strongly benefit from new, rather informal governance mechanisms. The informal governance of transactions stands in a strong contrast to the formal, contract-based governance mechanisms used in the realm of their former efficiency-centered business models. This business model transformation allows firms to enhance customer and network partner retention by building trustful, long-term relationships. This finding is consistent with Proposition 4b. Our findings related to case firm 13 do not contradict the insight that business succession leads to development path III as this case firm did despite experiencing business succession by now not successfully break the initial efficiency-centered business model design path. For the future, it would be interesting to know if case firm 13 will be able to finally break the initial path dependence and following to enter development path III.

Our case data shows that the incident of a crisis itself does not determine the business model development path. Instead, the characteristic of the crisis has to be considered. Case firm 3 that was threatened by a severe crisis caused by disruptive changes in the firm’s business ecosystem changed all three business model elements in one step and thus directly implemented a novelty-centered business model design. This direct move toward an innovative business model is in line with Proposition 6. In contrast, case firms 10 and 11 experienced crises that were not fostered by disruptive changes in the business ecosystem, but by rather firm-centric factors such as a lack of strategic foresight or disagreements in the top management team. Case firm 7 only experienced intensified competitive pressure that might have caused a firm-level crisis if no changes had been made. Therefore, these three case firms did not question all three business model elements at once like case firm 3 did, but decided for a stepwise adjustment of specific business model elements. However, case firms 10 and 11 had to recognize that these incremental changes were not enough to overcome the crisis. The CEO of case firm 10 highlighted:

“It was not enough to develop expertise in the realm of services. Last year, I needed to reorganize the whole firm, to outsource production processes, and to develop a network of partners that allow us to offer more integrated product-service solutions. Otherwise, the firm would not have survived.”

We see that a crisis in general is a strong driver of business model transformation that pushes firms toward the implementation of a novelty-centered business model design.

Our case data shows that not all firms that were able to overcome the efficiency-centered business model design by now make use of a novelty-centered business model design. Related to business model development paths II and III (see Fig. 1), we can observe that some case firms experienced persistence in either a complementarities-centered business model design (case firm 1) or a lock-in-centered business model design (case firms 4, 7, 8, 12). The CEOs of these case firms explained that the first step of changing the business model had been challenging and costly to their firms. Therefore, the CEOs of case firms 1, 4, 8, and 12 highlighted that after a period of changes they wanted to capitalize on the newly established business model design. As they were able to considerably enhance their revenues, they did not see a necessity to further transform their business models at that point in time. The CEO of case firm 1 stated:

“We are quite satisfied with the development of our business at the moment. By now, we just do not see how we could do things better.”

In these cases the firms showed a strong tendency to strive for exploitation after a period of exploring new business model-related opportunities that followed a path-breaking event. This change of tactics can be regarded as a triggering event that causes firms to enter a new path—a finding that is in line with our Proposition 5a. However, case firms 6, 10, and 11 are not affected by triggering events that narrow the scope of action. Instead, they move on in their development toward a novelty-centered business model design. For these firms we did not find evidence that they experience path dependence after being able to break free from the initial path dependent efficiency-centered business model. Our case data indicates that the CEOs of case firms 6, 10, and 11 regard business model change as a continuous process, while the CEOs of case firms 1, 4, 8, and 12 highlighted a discontinuous nature of change. This provides evidence for a specific influence of managerial perception on business model change.

In contrast to the explanations provided by the CEOs of case firms 1, 4, 8, and 12 that they are quite satisfied with their employed business model, we see a strong indication that their prolonged persistence in a business model design can also be the result of path dependence. The CEOs of all firms that are currently making use of a lock-in-centered business model design (case firms 4, 7, and 12) or experienced a persistence in a lock-in-centered business model design in the past (case firm 8) explained that their business model strongly benefits from linkages to the network of partner firms and customers. The CEOs further emphasized that they are in a position to manage the network. In doing so, they are able to bundle and make use of their network partners’ resources and capabilities. Therefore, changing established routines and structures that determine network collaboration does not seem to be an advantage as deviating from these practices would endanger the network-based supply with resources and capabilities. These aspects indicate the existence of certain externally-triggered complementary effects in the context of case firms that follow development path III (see Fig. 1). Moreover, the CEO of case firm 1 (development path II) strongly emphasized the need to adhere to specific rules and compliance guidelines in the context of transactions. He explained that all processes, no matter whether they are product-related or service-related, have to follow the same basic principles. This idea of unification is a remainder of the traditional product-based business logic. An emphasis on internal consistency and fixed practices points to coordination effects that seem to hinder business model transformation with respect to the structure element and the governance element. The identified complementary effect (development path III) as well as the coordination effect (development path II) are self-reinforcing effects that trap firms in either a lock-in-centered business model design or a complementarities-centered business model design. A statement of the CEO of case firm 7 illustrates this unintended persistence:

“Most of the time our service offerings are only a means to increase customer retention. We try to generate revenues out of our service business, but unfortunately by now only 10 % of our revenues are service sales.”

Later on in the interview he further explained:

“We already improved our structures and adjusted processes among business partners. We do not see a potential for further changes that might push our service business.”

The identified self-reinforcing effects are in line with Proposition 5b.

6 Discussion

Changing the business model seems to be a requirement for manufacturing firms to be able to pursue service-related opportunities (Kastalli et al. 2013; Kindström 2010). Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2010) state that a business model reflects a firm’s strategy and comprises a set of managerial choices as well as the consequences of these choices. Therefore, business model change requires rethinking managerial choices made in the past. Our case data shows that manufacturing firms struggle to change their business model in the context of pursuing service transition as these firms experience difficulties in redesigning their traditionally efficiency-centered business model. In this context, literature points to the relevance of cognitive constraints (e.g. Gebauer et al. 2005; Gebauer and Friedli 2005) as well as the lack of service-related capabilities (e.g. Gotsch et al. 2014; Ulaga and Reinartz 2011) that hinder firms to benefit from service-related opportunities. In addition, we show that the initial efficiency-centered business model of manufacturing firms is path dependent. Therefore, manufacturing firms need to be able to break the path of the efficiency-centered business model design in order to pursue service transition. With respect to path breaking, we found three main mechanisms—customer initiatives, business succession, and crisis—that are external in nature and enable manufacturing firms to abandon the initial efficiency-centered business model design. The path-breaking mechanisms we uncovered in the context of business model change support the reasoning by Sydow et al. (2009) who point to similar path-breaking mechanisms in the context of organizational path dependence. This is not surprising as organizational path dependence and business model path dependence are to a certain extent linked.

Although business model literature (Bohnsack et al. 2014; DaSilva and Trkman 2014; George and Bock 2011) already points to the relevance of path dependence, it is by now unclear how path dependence evolves in the context of business models and how it affects business model change. According to our case data, we see that manufacturing firms experience business model change after breaking free from an efficiency-centered business model design in two different ways. One group of firms is no longer affected by path dependence on their way to implementing a novelty-centered business model design. However, a second group of firms is still confronted with path dependence that influences decisions related to business model transformation. This difference can be explained by the fact that breaking the path of a particular business model design does not necessarily completely open up the scope of action, but very often only broadens it (McGrath 2010). We see that path breaking means for some firms that they are able to completely dissolve the initial path dependence, while others are only able to break free from being trapped in a specific business model design, but are not able to completely dissolve path dependence. Our case findings provide a more detailed perspective on this phenomenon. Path-breaking mechanisms have to be taken into account as they differ in terms of the effect they create. Our multiple-case study shows that we need to distinguish between opportunity-driven path-breaking mechanisms (customer initiatives and business succession) and threat-driven path-breaking mechanisms (different manifestations of crises). The latter are more likely to cause path dissolution. This is in line with literature that shows that economic shocks can trigger change, provoke firms to take greater risks (Bromiley 1991), and lead firms to pursue new opportunities that were previously unrecognized (Singh and Yip 2000; Wan and Yiu 2009). However, we need to consider that radical change increases the risk of failure (Chakrabarti 2014; Singh and Yip 2000). Hence, our sample might be affected by a survival bias.

As a consequence, we need to consider that firms can on the one hand directly change their business model to a novelty-centered business model design. On the other hand, they can also employ a stepwise approach to business model change with the aim of finally implementing a novelty-centered business model design. Making use of a direct approach is only possible for firms that were able to completely dissolve the path dependence of their initial efficiency-centered business model. A direct approach requires a simultaneous change of all three business model elements. Therefore, the business model change process of firms that follow this approach is not affected by further path dependence. However, radically changing all three business model elements seems to happen only in case of disruptive ecosystem changes. This finding is in line with Khanagha et al. (2014) who argue that established firms only encompass radical business model changes when groundbreaking developments in the business ecosystem force them to do so. However, we also enhance the findings of Khanagha et al. (2014) as we show that innovative business models can also be the result of many small transformation steps that are not triggered by severe ecosystem changes. Nevertheless, regarding firms that follow a stepwise approach, our case data indicates that path dependence can prevent firms from finally being able to implement a novelty-centered business model design. But why does path dependence affect some firms, while other firms do not experience a restriction of managerial discretion caused by path dependence in their business model change process?

According to our study, firms that successfully completed the stepwise approach or are about to complete it are very much alike to the firms that directly implemented a novelty-centered business model design. These firms approach business model change by employing a market perspective. The decision how to change specific business model elements is strongly influenced by asking what the market needs. Cortimiglia et al. (2015) distinguish between an outside-in and an inside-out perspective on business model innovation. According to their findings, the outside-in perspective is mainly prevalent in entrepreneurial ventures, while the inside-out perspective is linked to established firms. Hence, our results extend the findings by Cortimiglia et al. (2015) as we show that an outside-in perspective is also relevant in the context of established firms. Furthermore, case firms that take an outside-in perspective are more proactive in pursuing service transition-triggered business model change. However, it is important to understand that this proactiveness is not linked to a higher entrepreneurial orientation (Lumpkin and Dess 1996), but rather the result of experiencing threats or the consequence of unanticipated side effects. The latter effect can be observed in case firms that experienced the first step of business model transformation as an emergent process and only later on recognized the benefits of a novelty-centered business model design. A possible emergent nature of business model transformation in the context of service transition is supported by literature (Fischer et al. 2010; Kowalkowski et al. 2012) that points to the relevance of ad-hoc decisions, continuous modifications and incremental change that may for manufacturing firms cause unanticipated side effects.

In contrast, case firms that are affected by path dependence in their business model transformation process rather focus on an inside-out perspective. Starting point for business model change is for these firms always the already employed business model design. Changes are implemented based on existing resources and capabilities that are only adjusted and recombined. The strong focus on retaining existing resources and capabilities is not surprising as for instance Khanagha et al. (2014) already provide first evidence for such a behavior of established firms. In the context of our case firms, limited resources seem to affect business model transformation decisions. Fang et al. (2008) point to the relevance of resource slack in the context of service transition. Furthermore, Ulaga and Reinartz (2011) highlight that manufacturing firms need to develop capabilities in order to leverage resources to be able to pursue service-related opportunities. Especially smaller firms seem to be affected by these challenges (Gebauer et al. 2010; Kowalkowski et al. 2013). Therefore, it is comprehensible why firms in our sample decide to switch from exploration to exploitation after finalizing the first step of business model change. However, this decision is a triggering event that, if accompanied by self-reinforcing effects such as coordination effects and complementary effects, trap a firm in either a complementarities-centered business model design or a lock-in-centered business model design. The self-reinforcing effects we were able to identify in the context of business model path dependence are again also of relevance in the context of organizational path dependence as highlighted by Sydow et al. (2009).

As a last aspect, we need to discuss whether the novelty-centered business model design itself can be affected by path dependence. As only two firms in our sample already finalized the process of implementing a novelty-centered business model design, we have only first insights regarding this aspect. However, the novelty-centered business model designs of both case firms that completed the change process do not show rigidities. Instead, they are characterized by a high degree of flexibility that becomes apparent in dynamic and ongoing adjustments of all three business model elements. This specific flexibility as part of the business model design is something we also observe in the business models of the case firms that are currently changing toward a novelty-centered business model design. Therefore, a novelty-centered business model design seems to encompass certain “discrediting mechanisms” (Garud et al. 2010) that help to prevent negative effects of path dependence. A reason why this might be the case is that the novelty-centered business model designs of our case firms are characterized by a strong customer- and network-orientation. These business model designs allow the firms to sense changes in the business ecosystem more quickly—an insight that supports the theoretical reasoning by Lusch et al. (2007).

7 Conclusion, limitations, and outlook

In this paper, we conduct a multiple-case study analyzing business model change processes of 13 manufacturing firms that are challenged by service transition. Related to our first research question (1) How do manufacturing firms change their business model in order to respond to challenges caused by service transition? we provide evidence that manufacturing firms strive for establishing a novelty-centered business model design when challenged by service transition. Starting from an efficiency-centered business model design, the business model change process can take place either directly or stepwise. The direct approach is characterized by a simultaneous change of the content element, the structure element, and the governance element of the business model. In contrast, firms that employ a stepwise approach do not question the whole business model design, but encompass focused changes of specific business model elements while coevally trying to keep the other business model elements stable. Thus, our findings contribute to process-related research on business model innovation and transformation (e.g. Cortimiglia et al. 2015; Frankenberger et al. 2013) as we are able to uncover the steps of business model change processes in the context of established manufacturing firms in detail. Furthermore, we overcome a deficiency also highlighted by Schneider and Spieth (2013) that most studies on business model change only refer to radical, industry disruptive business model innovation.

We are able to answer our second research question (2) How does path dependence affect the business model change process of manufacturing firms in this context? by identifying four business model development paths that differ in the way how they are affected by path dependence. Our results show that all manufacturing firms under research initially employed a path dependent, efficiency-centered business model design. Business model development path I is characterized by firms that still make use of an efficiency-centered business model design. These firms are due to path dependence by now not able to encompass changes in their business model. In contrast, firms following business model development paths II, III, or IV were due to external influence factors able to break free from the initial efficiency-centered business model design. Business model development paths II and III are characterized by a stepwise approach to business model change. The first step in business model development path II is a business model transformation toward a complementarities-centered business model design. Firms accomplish this business model transformation step by solely changing the content element. Only in a second step, these firms focus on establishing a novelty-centered business model design by changing the structure element and the governance element of their business model. When pursuing business model development path III, firms in a first step transform their business models toward a lock-in-centered business model design by coevally changing the structure element and the governance element. To finally implement a novelty-centered business model design, these firms change the content element in a second step. However, not all firms following business model development paths II or III are able to complete both transformation steps. Triggering events and self-reinforcing effects may prevent firms from achieving a novelty-centered business model design and either trap them in a complementarities-centered (business model development path II) or a lock-in-centered (business model development path III) business model design. Business model development path IV depicts a direct approach to achieving a novelty-centered business model design. When a firm follows this business model development path, it is not affected by path dependence after breaking free from the initial efficiency-centered business model design. Our study provides new insights on business model path dependence and thus contributes to a deeper understanding of barriers to business model innovation and transformation. In doing so, we considerably enhance business model literature (e.g. DaSilva and Trkman 2014; George and Bock 2011) that points to the relevance of path dependence in the context of business model change.

Our findings are of special interest from a managerial perspective. By uncovering the role of path dependence in business model change processes we provide an opportunity for managers to learn from the experience of others. We highlight in detail crucial triggering events and self-reinforcing effects that are of relevance in this context. Being aware of these factors enhances the probability that managers are not being trapped in a narrow scope of action that prevents them from changing an extant business model design that is not favorable for their firm. Nevertheless, an increased awareness of path dependence in the context of business model change does not necessarily prevent managers from being affected by mechanisms that constitute path dependence. Therefore, we point to the importance of external advisors such as business consultants. Due to not being embedded in firm-internal structures and processes, it is easier for them to recognize triggering events and self-reinforcing effects that lead to path dependence in business model change processes.

Naturally, we acknowledge that our study is not free from limitations. First, limitations in the context of our theoretical background have to be mentioned. The business model concept as well as the path dependence concept still lack clarity as researchers employ a variety of different definitions and understandings in this context. However, as we refer to theoretically well-developed and well-established conceptualizations (Amit and Zott’s (2001) business model conceptualization and Sydow et al.’s (2009) path dependence framework) we are confident that our way of proceeding is appropriate. Next, limitations that go along with our qualitative-empirical research need to be considered. Case study research is affected by limited generalizability (Yin 2009). Moreover, our retrospective analysis based on interviews with key informants is challenging as changes in organizational structure or cognitive biases might influence the interviewed CEOs’ perception of the past (Golden 1992; Huber and Power 1985). However, the conducted interviews provided valuable information on underlying decision making processes. As the information drawn from the interviews is completed by exaggerate archival data, we are sure that we were able to minimize possible negative effects related to this aspect. Furthermore, changes in the firms’ business models were made quite recently and all interviewed CEOs were responsible for all business model changes that have been examined in our study.

Another aspect that needs to be considered is related to our case study sample. As we aimed at analyzing business model change processes triggered by service transition, our sample only consists of firms operating in manufacturing industries. We also limited our sample to firms with no more than 500 employees. This was necessary to ensure comparability (Eisenhardt 1989). Hence, we encourage researchers to have a look at other research settings. It would be interesting to learn more about the relevance of path dependence in the realm of business model change in other industries as well as in larger firms. Furthermore, our findings provide first empirical evidence that business model change may—in contrast to business model literature (e.g. Amit and Zott 2012; Mitchell and Coles 2003) that often assumes a deliberate nature of business model change—also be the result of an emergent process. Hence, investigating the deliberate or emergent nature of business model change processes is another area of interest for future research. Additionally, analyzing linkages between business model change, path dependence, and firm performance would also be of interest. As the intriguing field of research we approach in this paper calls for further exploration, future research should take on where we have left off.

References

Amit R, Zott C (2001) Value creation in e-business. Strateg Manag J 22(6–7):493–520. doi:10.1002/smj.187

Amit R, Zott C (2012) Creating value through business model innovation. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 53(3):41–49

Arthur WB (1989) Competing technologies, increasing returns, and lock-in by historical events. Econ J 99(394):116–131. doi:10.2307/2234208

Arthur WB (1994) Increasing returns and path dependence in the economy. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Barney J (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manag 17(1):99–120. doi:10.1177/014920639101700108

Bluhm DJ, Harman W, Lee TW, Mitchell TR (2011) Qualitative research in management: a decade of progress. J Manage Stud 48(8):1866–1891. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00972.x

Bohnsack R, Pinkse J, Kolk A (2014) Business models for sustainable technologies: exploring business model evolution in the case of electric vehicles. Res Policy 43(2):284–300. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.10.014

Bowen DE, Jones GR (1986) Transaction cost analysis of service organization-customer exchange. Acad Manag Rev 11(2):428–441. doi:10.5465/AMR.1986.4283519

Bowen DE, Siehl C, Schneider B (1989) A framework for analyzing customer service orientations in manufacturing. Acad Manag Rev 14(1):75–95. doi:10.5465/AMR.1989.4279005

Bromiley P (1991) Testing a causal model of corporate risk taking and performance. Acad Manag J 34(1):37–59. doi:10.2307/256301

Bucherer E, Eisert U, Gassmann O (2012) Towards systematic business model innovation: lessons from product innovation management. Creat Innov Manag 21(2):183–198. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8691.2012.00637.x

Casadesus-Masanell R, Ricart JE (2010) From strategy to business models and onto tactics. Long Range Plan 43(2):195–215. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2010.01.004

Casadesus-Masanell R, Zhu F (2013) Business model innovation and competitive imitation: the case of sponsor-based business models. Strateg Manag J 34(4):464–482. doi:10.1002/smj.2022

Cavalcante S, Kesting P, Ulhoi J (2011) Business model dynamics and innovation: (re)establishing the missing linkages. Manag Decis 49(8):1327–1342. doi:10.1108/00251741111163142