Abstract

This article uses the informal governance framework to elucidate the connection between regime transition and participation in regional international organizations (IOs). In particular, this study focuses on non-democratic regional IOs and examines the empirical case of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). We investigate how the level of regime transition of each CIS member state affects its participation in the CIS. The paper utilizes an original dataset that contains information regarding the number of CIS-related agreements that have been signed by each CIS member state during the 1991–2010 time period, which can be used to measure the level of participation of each state in the CIS. We find that states with a lower level of democratization and a higher level of marketization are more likely to participate in agreements within the CIS. The paper contributes to the wider application of informal governance framework by demonstrating the usefulness of these theories for understanding the nature and dynamics of regional IOs, such as the CIS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The post-Cold War world has witnessed a recent wave of democratization, which has been accompanied by the extensive development of regional international organizations (IOs). The interconnections between IO membership and democratization have become a topic of intense debate. In particular, the extant literature regarding this topic has primarily focused on international organizations that have been created by democratic states and are largely composed of democracies. In fact, these types of regional IOs have been the most successful IOs in the world. However, another group of regional IOs with members that are predominantly non-democratic also exists in the world.Footnote 1 For the purposes of the following discussion, we will define a non-democratic IO as an organization in which the leading state and most of the member states of the IO are not democracies (these states are not necessarily consolidated autocracies; instead, different forms of hybrid regimes may be included). Similarly, we use the term democratic IO to refer to an IO in which the leading state and most of the member states of the IO are democracies. It is important to note that our definition of non-democratic IOs refer not to their formal governance but rather to the political regimes of the member states, particularly the leading state.Footnote 2

It appears plausible that different links between democratization and IO membership or a nation’s level of participation in an IO could be observed for non-democratic IOs than for democratic IOs. Previous studies have demonstrated that for a democratic IO, democratization is associated with a higher level of participation in the IO. Is this association applicable in the context of non-democratic IOs? To investigate this issue, we apply the framework of informal governance in IOs that was developed by Stone (2011). From this perspective, international organizations are governed by two sets of rules: formal and informal ones. Leading states in IOs have the opportunity to override a policy that member states would otherwise have chosen according to formal rules. This phenomenon is referred to as manipulation. Hence, member states that decide to join an organization or select a particular level of participation in an organization are aware of the fact that they may later be subjected to manipulation under circumstances in which the costs of exiting the regional IO may be too high for these member states to avoid following the policy dictated by the leading state. This time-consistency problem determines the conditions that impact individual countries’ decisions to join an IO.

The present article uses the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) as a case study. The CIS appears to be a good example of a non-democratic regional IO, given that both its leading state (Russia) and a majority of its members are non-democracies or hybrid regimes that demonstrate strong authoritarian tendencies. The unique dataset that is utilized in this study offers the opportunity to measure the levels of formal participation of individual member states across different areas of collaboration and different time periods during the past 20 years (1991–2010). The paper finds that in contrast to democratic IOs, the level of participation in the CIS is higher for member states that are less democratic. After controlling for democracy-related considerations, states with more advanced economic reforms and lower energy dependences on other states are more likely to engage in a higher level of participation in the CIS. These results confirm the arguments of the informal governance literature, which states that participation in an IO is driven by the availability of the exit options and that countries with stronger structural power are more likely to demonstrate higher levels of participation in a non-democratic regional IO.

2 Theory and hypotheses

There are two main types of arguments in the extant literature that explain the participation of countries in regional IOs. The IO-as-a-commitment-device argument suggests that IOs serve as a tool to enhance the credibility of commitments towards democratization (Pevehouse 2002; Snidal and Thompson 2003; Mansfield and Pevehouse 2006, 2008) and market reforms (Dreher and Voigt 2011; Fang and Owen 2011). As a result, democratization and participation in the IOs should be mutually reinforcing phenomena. However, this theoretical argument has only been developed for the case in which “the organization is composed primarily of democratic members” (Mansfield and Pevehouse 2006: 137); thus, this reasoning does not necessarily yield predictions with respect to the non-democratic IOs that we are more interested in studying in the current investigation. The alternative point of view, which can be derived from the informal governance literature, suggests that the ability of IOs to act as commitment devices may be compromised by the manipulations of the leading states of these IOs. These manipulations occur during crises; i.e. at the times when the stakes of certain actions are high for the leading state, which therefore feel compelled to override the existing formal rules. The ability of the leading state of an IO to engage in these manipulations and the capabilities of the other IO member states to prevent these manipulations are dependent on structural power, i.e., the opportunity of individual countries to exit the regional IO and thereby impose additional costs on remaining IO members (Stone 2002, 2004, 2008, 2011; Dreher and Jensen 2007).

The apparent contradiction between these two arguments is resolved differently for individual IOs, depending on both the decision-making mechanisms of each IO and the balance of power between the leading state and the weaker states of a particular IO. For non-democratic regional IOs, both of the aforementioned predictions of the literature must be modified. In particular, one could expect that relative to democratic IOs, non-democratic IOs may be much less likely to serve as commitment devices. Moreover, manipulations by the leading state of an IO, a key element of the informal governance of these organizations, are expected to be even more prominent in a non-democratic regional IO than in a democratic IO. These effects can be caused by two sets of factors. First, relative to democratic IOs, the lower credibility of non-democratic IOs and the higher propensity of the leading states of these IOs to engage in manipulations may be driven by the fact that the decisions that are reached by politicians and bureaucrats in these leading states lack both internal constraints and transparency. In democratic IOs, credibility can be enhanced by audience costs, which are typically believed to be smaller in non-democracies than in democracies (Fearon 1994; Bueno de Mesquita and Smith 2012), and by the multiplicity of veto players in democratic nations (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 1999). Second, another potential cause of both of the aforementioned features of non-democratic IOs is that within the context of these IOs, the bureaucrats and politicians of non-democratic member states may mimic the decision-making practices that they use within their own nations; certainly, other actors will likely expect this phenomenon to occur.Footnote 3

Under these conditions, one could describe the cost-benefit calculation of a country that is deciding to either join a non-democratic IO or increase its level of participation in this type of IO by focusing on three groups of factors. First, this decision should be driven by the costs and benefits during “ordinary times,” i.e., situations in which the formal governance of the IO is not overridden by informal manipulations. The benefits of IO participation in these scenarios could include access to new markets; economies of scale in the production of regional public goods; mutual insurance from external shocks; and financial, military and political assistance from the leading state, among other considerations. The use of IOs as a credible commitment device is another example of this type of benefit. Similarly, the costs of IO membership or participation are associated with efficiency losses through trade diversion; potential adverse reactions from certain domestic groups and/or the general public; and, more generally, risks that are associated with the propensity of the formal procedure to make decisions that conflict with the interests of the individual country in question. Second, the decision to join or participate in an IO should account for the risks of manipulations and the ability of a nation to avoid these manipulations, especially the availability of exit options. Third, this decision is influenced by access to alternative regional IOs that may provide their own costs and benefits.

Using this perspective, we can develop specific hypotheses for both democratization and marketizationFootnote 4 as factors that determine a nation’s participation in non-democratic regional IOs. First, as opposed to democratic IOs, a democratizing state cannot credibly signal its intent to democratize by joining a non-democratic IO. In fact, a country’s decision to lower its level of participation in a non-democratic IO can be perceived by outsiders as a signal that it has decided to strengthen its efforts towards democratization: for the purpose of democratization, this nation may be prepared to disregard the economic gains that it obtains from membership in a non-democratic IO and to instead rely solely on possible support from democratic IOs, which feature much higher requirements with respect to adopting political reforms. Thus, the specific benefits during “ordinary times” for democratizing states are lower for non-democratic IOs than for democratic IOs.Footnote 5 Second, in IOs, the structural power of non-democratic states should be larger than the structural power of democratic states because ceteris paribus, the former states will have greater exit options due to their lack of internal constraints (such as audience costs and multiple veto players, for instance). In addition, relative to democracies, non-democracies might find it easier to adjust their decision-making style to the way in which decisions are made by the leading state of an IO; thus, non-democracies may be able to more readily anticipate the extent of manipulations by the leading state of the IO and plan possible responses to these manipulations. Third, many democratic IOs require their members to adopt an explicit agenda that supports democratization, whereas non-democratic IOs may act as tools that promote autocratic practices (Allison 2008; Collins 2009; Cameron and Orenstein 2012). The severe constraints on membership that may be imposed by democratic IOs can render it more difficult for non-democratic countries to join these organizations. Thus, based on both the IO-as-a-commitment device and the informal governance arguments, we can formulate the following hypothesisFootnote 6:

H1: A country’s level of participation in a non-democratic IO is likely to decrease if the country in question becomes more democratic.

With respect to marketization, we derive our hypothesis in a similar fashion. First, the IO-as-a-commitment-device argument is not applicable to non-democratic IOs unless there are reasons to believe that the leading state will promote economic reforms in the neighboring countries for purely egoistic reasons (this phenomenon may occur under certain circumstances, such as if the economic liberalization of neighboring states provides greater access to these states for multinationals in the leading state of an IO, but is unlikely to be present in any systematic fashion in non-democratic IOs). Second, economic reforms could enhance a nation’s options to exit an IO by providing the country in question with access to other IOs that have higher barriers to entry; thus, these reforms would cause a nation to be less dependent on a particular IO (or on particular countries as economic partners). Third, broader access to various IOs around the world could make countries that have implemented advanced market reforms less inclined to participate in a non-democratic regional IO. Thus, the IO-as-a-commitment-device and the informal governance arguments actually produce different predictions with respect to the impact of marketization on membership in non-democratic regional IOs. The former rationale suggests that increased marketization should reduce the inclination of countries to join these IOs. However, by the latter reasoning, if there are substantial benefits during “ordinary times” that can be extracted from membership in a non-democratic IO, countries with more advanced economic reforms may be less concerned about the threat of manipulation and may therefore be more interested in participation in the IO in question. Thus, we can formulate two contradicting hypotheses for this variable:

H2.1: The level of participation in a non-democratic IO is likely to decrease if a country becomes more advanced with respect to economic reforms (IO-as-a-credible-commitment-device argument).

H2.2: The level of participation in a non-democratic IO is likely to increase if a country becomes more advanced with respect to economic reforms (structural power argument).

Hypothesis 2.2 is particularly interesting in the case of the CIS because it offers an interesting contrast to the arguments of Darden (2009), who investigated the impact of economic ideas on participation in post-Soviet regional IOs. Darden found that liberal ideas from a nation’s elites (the promotion of both market reforms and integration into global IOs, such as the WTO) are negatively correlated with a nation’s extent of participation in the CIS. Hypothesis 2.1 is consistent with Darden’s argument, whereas Hypothesis 2.2 suggests the opposite. However, the relationship between liberal ideas, marketization and IO membership can be complex. First, although liberal ideas are crucial for reforms, these ideas do not necessarily correlate precisely with the implementation and success of these reforms. Hellman (1998) demonstrates how reforms can be captured by interest groups, causing the failure of liberal governments’ attempts to facilitate marketization. Second, active participation in the CIS may also be an involuntary outcome of a need to cope with internal or external conflicts. Finally, there may be differences of positions within the bureaucratic apparatus of a particular country; in almost all of the CIS member states, this apparatus includes a division that is responsible for CIS affairs, which may be populated by individuals with different sets of ideas than the principles that are held by the remainder of the nation’s government.

Finally, in accordance with the informal governance framework, we can also formulate an additional hypothesis. Stone (2011) conjectured that countries are more likely to delegate decisions to IOs in areas that are expected to involve lower potential for conflict (causing manipulation by the leading state to be a less threatening prospect). In other words, structural power and exit options are more important if there is a higher potential for conflicts to arise. If the effect of democratization and marketization on participation in non-democratic IOs is driven by structural power considerations, we should expect these factors to be more important if conflict potential is significant. If the conflict potential is low, there is a lower probability that manipulation will occur; therefore, exit options will be less relevant. Hence, we consider the following hypothesis:

H3: The effect of political regime and economic reforms on the level of participation in non-democratic IOs should be stronger in areas that are more prone to conflict.

3 Informal governance in the post-Soviet context

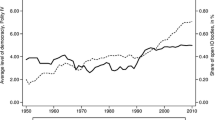

The empirical case that is used to test the aforementioned hypotheses is the CIS. This organization includes Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan; between 1993 and 2009, Georgia also belonged to this organization. In the Supplementary Material to this paper, which is available online at this journal’s webpage, we report the average level of democratization in the CIS and the share of countries in the CIS that can be denoted as non- or semi-democratic using several measures of democracy that are regularly employed in the literature: the Freedom House (FH) index of political rights; the Polity IV index; the most recent version of the binary index of democracy (Cheibub et al. 2009) that was first suggested by Alvarez et al. (1996), which we denote as the DD index; and several sub-indices of the FH Nations in Transit report. According to all of these indicators, most of the CIS countries have been non-democratic throughout their histories. All of the aforementioned measures (except Polity IV) indicate that the leading country of the CIS, Russia, has been non-democratic or hybrid throughout the entire period that is examined by this study. Thus, the CIS is a good example of a non-democratic regional organization; from the original founding of the CIS, most of the organization’s members have been either non-democracies or hybrid regimes with strong authoritarian tendencies.

The CIS was established immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 as a type of continuity organization that attempted to foster cooperation among the former Soviet republics in various economic, political and military spheres. Although the agenda and the ambitions of the CIS are vast (full-fledged economic union; political and military cooperation; and common social and labor standards), this organization has produced only limited results to date (Libman 2007; Kubicek 2009; Obydenkova 2011). Nevertheless, membership in the CIS can provide substantial benefits during “ordinary times” (see Libman and Vinokurov 2012). First, the CIS shares highly integrated and commonly governed infrastructure in the areas of electricity and railroad transportation. Second, the CIS has managed to maintain a relatively integrated labor market through its implementation of a visa-free regime for migration; during the previous decade, several post-Soviet countries have received very large remittances from migrants who are operating in other CIS countries. Third, participation in the CIS has been actively used by the leadership of several countries in the contexts of internal policy debates; in some countries, public opinion continues to largely favor post-Soviet integration. Fourth, Russia has also typically been ready to provide higher levels of informal support to countries that are more active in the CIS. This support may take various forms, such as low energy prices or favorable references on Russian TV stations (which remain dominant in many countries of the region).Footnote 7 Fifth, the CIS has offered an informal forum for regular meetings of presidents and high-ranking bureaucrats from post-Soviet countries; these meetings may have been instrumental for resolving a subset of the differences among these countries. Sixth, participation in the CIS has traditionally been favored by certain domestic interest groups in CIS member states (Abdelal 2001; Darden 2009). There is also a specific set of benefits from CIS membership and participation that is only applicable to non-democratic nations; namely, the CIS often supports non-democratic regimes in the region (Ambrosio 2006). By contrast, a country that wishes to lower its level of participation in the CIS could experience Russian pressure. It is important to understand that with the exception of the common infrastructure that exists among CIS members, the benefits from participating in the CIS do not actually result from the implementation of the CIS agreements, which feature ambitious goals. By signing these agreements, countries merely demonstrate their willingness to maintain ties to Russia to both the Russian leadership and their own domestic populations; in exchange for these demonstrations, these nations receive Russian support and access to the Russian labor market. However, CIS members are free to avoid implementing the agreements that they sign; as a result, the CIS members often repeatedly sign identical agreements, which they subsequently ignore.

Thus, in the case of the CIS, the informal governance argument should be modified as follows. Under normal circumstances, member states are free to ignore most of the commitments that they make and benefit from Russian support and the existence of partial areas of cooperation in the CIS. In the case of extraordinary events, i.e., if the risks are especially high for Russia, the leading state of the CIS, to damage its dominance or image as a strong state, the situation changes dramatically; in this situation, the leading state could attempt to revive the legal framework of the CIS and exploit the opportunities that are provided by the CIS’s formal arrangements. The formal commitments of CIS members actually do provide the CIS with substantial opportunities to influence its members. In particular, these commitments include a comprehensive network of agreements; if the literal content of these agreements were enforced, the actions of CIS member states would be severely restricted. Many of the restrictions that are imposed by existing CIS treaties favor Russia either economically (by providing attractive opportunities for the business expansion of Russian multinationals) or politically (by restricting the opportunities of CIS members to participate in outside regional IOs). As Hale (2008: 212) observes, the CIS faces a credible commitment problem, which can be defined as “the difficulty involved in guaranteeing to a potential union’s would-be member states that they will not later be exploited in that union but will instead partake in a share of the benefit.”

During two major crises that Russia encountered during its interactions with post-Soviet states over the course of the previous decade, it immediately attempted to use the CIS framework as one of its tools for exerting political pressure on its neighbors. The first major crisis occurred in 2003–2004; during this period, several post-Soviet countries (Ukraine, Georgia and Kyrgyzstan) experienced “color revolutions,” i.e. massive protests after falsified election results resulting in the loss of power for the existing non-democratic regimes of these nations. The contagion of the colored revolutions was perceived as a serious threat to the Russian regime. To address this challenge, Russia intensified the work of the electoral observers from the CIS.Footnote 8 The positions of the CIS observers are strongly motivated by politics: in many cases, the conclusions of CIS observers conflict with the conclusions of international observers from the OSCE or similar organizations. CIS observers have been known for both describing falsified elections as conforming to democratic standards and criticizing legitimately democratic elections. Thus, Russia manipulated the CIS to exert pressure on CIS governments. Governmental changes in CIS nations that were not supported by Russia resulted in a critical report from CIS observers; to an extent, these reports could undermine the legitimacy of the criticized election or be used by internal political opponents.

During another major crisis, the Russian war against Georgia in 2008, Russia attempted to ensure that the post-Soviet regional organizations supported its actions. In particular, Russia sought to use three consecutive meetings of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO; the former security branch of the CIS, which has become an independent organization over time), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the CIS (these structures have mostly overlapping memberships) to achieve this purpose. In September 2008, the CSTO decided to condemn Georgia’s aggression against South Ossetia, but refused to accept any collective course of action with respect to the recognition of the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The SCO summit merely declared its concern regarding the military confrontation (at this summit, the position of China, the only non-post-Soviet member of the organization, was considered to be crucial to the SCO perspective). The CIS summit did not make any statements regarding this war. Thus, although it could be argued that Russia’s strategy was somewhat successful in the case of Ukraine (i.e., the Orange Revolution in Ukraine was not followed by similar events in Russia or in other key post-Soviet countries), Russia’s use of non-democratic regional IO failed with respect to the Georgian war.

A further feature of the CIS is of crucial importance for our research design. In contrast to participation in many other IOs, participation in the CIS is not a binary decision. Within the legal framework of the CIS, each country is free to select the intensity of its involvement in the organization, a trait that we will call the level of participation for each CIS member. CIS members are allowed to abstain from participation in any decision of CIS institutions or any CIS agreement that is signed. Thus, the CIS has essentially produced what might be termed a “regional organization a la carte,” or a menu of different agreements, decisions and acts from which member states are (almost) free to choose. Of course, these choices are subject to external influences and informal bargaining, which are often heavily affected by Russia and other major players, such as Belarus and Kazakhstan. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no instances in which Russia explicitly forced CIS states to join any agreement through the use of military force.Footnote 9 However, Russia has actively used informal pressures of various sorts, such as the price of natural gas or delays in withdrawals from military installations. As a result, the countries of the CIS exhibit high variation in terms of the number of agreements that they have signed across different policy areas (see the Supplementary Material for further details).

4 Data and methodology

The dependent variable of this study is derived from the CIS Register of Official Acts, which includes all of the CIS-related agreements, decisions and protocols that have been signed by the CIS members. Each document is assigned to a particular area of consideration from the six primary areas distinguished by our analysis: organization of the CIS; economic cooperation; political cooperation; social and humanitarian cooperation; legal cooperation; and military, police and security cooperation.Footnote 10 Furthermore, for each document, the CIS reports the exact countries that have decided to sign this agreement.Footnote 11 In the main specification of our model, we only include agreements that were signed without reservations. Our work is related to studies by Malfliet et al. (2007), Hale (2008) and Darden (2009), who also examine the number of agreements that have been signed in the CIS, although these researchers assess time periods and questions that differ from the specific considerations that are addressed in the current paper.

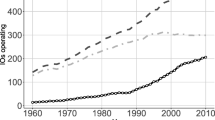

The empirical design of our study faces a significant challenge with respect to the choice of the unit of observation. Agreements often require several years of preparation and discussion and are signed in large packages at certain occasions that only occur every few years; thus, the use of annual data regarding agreements is impractical and even misleading. However, if we merge the annual data into periods that encompass several years, we substantially decrease the number of observations that can be examined; for instance, if 5-year increments are used to assess the agreements from 12 countries, only 48 observations are produced. Because participation in the CIS can be strongly associated with country-specific effects, the estimation of regressions without country fixed effects would not be prudent, but the inclusion of these effects would further reduce the degrees of freedom of the estimation. Thus, to obtain a reasonable sample size but also avoid misleading conclusions from annual data, we employ the following approach. We apply as the unit of observations the number of agreements in a particular area that were signed by a particular country during a particular period. We divided the entire period into 5-year increments (1991–1995, 1996–2000, 2001–2005 and 2006–2010) and calculated the total number of agreements that were accepted for each period. Thus, we observe each country for four periods and six areas of cooperation. This method provides us with 24 observations per country. We include in our sample all twelve of the former Soviet republics that were members of the CIS during the majority of the 1991–2010 time period. Thus, there are 288 overall observations in the baseline specification of the model of this study. We understand that treating the number of agreements in different areas for the same country as separate observations may produce econometric problems; therefore, we also examine the total number of agreements per country in all areas as the dependent variable and assess separate areas of cooperation through separate regressions.

Several observations may be offered regarding the composition of the sample for this study. First, we exclude three Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) from the sample because these countries have never been members of the CIS, were recognized as independent states before the USSR was actually dissolved (and therefore before the CIS was created as a supplement for the USSR) and became EU members during the 2000s. Furthermore, we include Georgia, which was a member of the CIS for nearly the entire period of our investigation but officially left the organization in 2009.Footnote 12 Finally, we also include Russia in the main regressions of this study. As the leading state of the CIS, Russia may encounter costs and benefits from its participation in the CIS that are not experienced by other CIS members. However, there are several reasons to include Russia in the regressions of this study. First, the general research question of this paper addresses the role of democratization and marketization as determinants of participation in a non-democratic IO. It is therefore important to understand whether the driving factors of CIS participation differ substantially between the leading state and the other member states of the organization (as we will show in the following sections, significant differences do not exist in this respect). Moreover, although the Russian political regime has remained non- or semi-democratic during the past two decades, it has evolved substantially over the course of this time; thus, it is important to understand the effects of this evolution on CIS participation.Footnote 13 Second, the structural power of Russia vis-à-vis other CIS states has also changed greatly during the course of the past two decades. Empirically, we observe that during certain periods, Russia has lagged behind several other CIS countries with respect to participation in CIS agreements. In several cases, major post-Soviet integration initiatives have been blocked by Russia (e.g., the Eurasian Union in 1994 or the more radical elements of the formation of the Commonwealth of Belarus and Russia in 1996). One could hypothesize that Russia’s recent increases in structural power, which rendered the nation more capable of manipulating other CIS institutions, caused it to become more eager to increase its level of participation in the CIS. This increase in structural power could have been driven by the economic development of the country (which was associated with the progress of economic reforms) and the consolidation of the Russian political regime (which took the form of the creation of Putin’s non-democratic regime). However, we assess our results for robustness by excluding Russia and Georgia.

We use the following two key explanatory variables (all of which are averaged over 5-year periods). First, to capture the effect of marketization, we utilize the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) index of structural reforms, which has been actively used in a variety of research on transition countries. We consider the average EBRD index over all areas of structural reforms. This index varies between 1 (low progress) and 4.3 (standards and performances that are typical for advanced and industrialized economies). Second, we use the FH index of political rights as the primary measure of democratization in the regressions. This index varies from 1 to 7, with 1 indicating a full-fledged democratic country and 7 representing a strict authoritarian regime. We use other democracy indices for robustness checks.

In addition to these key variables, we add a set of further controls that capture other elements of the cost-benefit considerations that were discussed in section 3. First, we control for the level of economic development and economic potential of each nation by considering each country’s GDP per capita (in constant US dollars at price levels from the year 2000, averaged over each five-year period), total GDP (in constant US dollars at price levels from the year 2000, averaged over each 5-year period) and log total GDP.Footnote 14 Second, we control for both the economic openness of each country and the extent of each nation’s economic dependence on the CIS (again, averaged over a 5-year period). Economic openness is measured as the share of a country’s GDP that is composed of foreign trade. Economic dependence on the CIS is captured by the share of total trade turnover (exports plus imports) that is composed of CIS trade turnover (this variable is reported by the CIS Interstate Statistical Committee). Third, we control for WTO participation through the use of a dummy variable that is set equal to 1 for countries that joined the WTO (Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Georgia and Ukraine) during an examined time period.Footnote 15 Fourth, a topic of crucial importance for participation in post-Soviet regional IOs is the issue of the ethnic composition of each nation’s population (Abdelal 2001; Hale 2008). More specifically, there are two variables that we use to control for ethnic composition: the share of ethnic Russian population in each nation and the share of the titular ethnicity that is present in each CIS nation, i.e., Armenians in Armenia, Ukrainians in Ukraine, etc.Footnote 16

We estimate the main regressions using OLS. For a robustness check, we use negative binomial regressions; these negative binomial regressions may be more appropriate for the current investigation because we use a dependent count variable, but they are more difficult to estimate for models that incorporate fixed effects (see discussion in Hausman et al. 1984; Cameron and Trivedi 1998; Allison and Waterman 2002). However, with minor exceptions, the regression results are consistent over both estimation techniques. Each regression includes not only a full set of time and country fixed effects but also fixed effects for individual areas where agreements are signed. We also cluster standard errors by area because it is likely that the number of agreements that are signed by each country in a particular area will be interdependent.

5 Results

Hypotheses 1 and 2

Table 1 reports the main results of our study. Regression (1) includes only the progress of economic reforms and democratization; regressions (2), (3) and (4) also control for the GDP, GDP per capita or log GDP for each examined nation, respectively; regressions (5) and (6) add the trade structure considerations to the set of covariates; regression (7) controls for WTO membership; and regression (8) simultaneously controls for WTO membership and trade structure. Similarly, regressions (9) and (10) control for the share of ethnic Russians (we exclude the Russian Federation itself from this analysis, given that this variable obviously does not apply for Russia itself), with trade structure considerations excluded and included, respectively. Regressions (11) and (12) replicate regressions (9) and (10) but replace the share of ethnic Russians by the share of the titular ethnic group of each nation (again, we exclude Russia). The econometric tests suggest that the model is of adequate quality. Both the R-squared and the adjusted R-squared values of the model are above 0.7, and the likelihood ratio test suggests that the model performs significantly better than the intercept-only model without fixed effects in predicting the number of agreements that are signed by each nation.

We obtain two striking findings. First, democratization has a persistent and negative impact on the number of agreements that are signed by each nation. This result is consistent with our hypothesis that countries with lower levels of democracy would be more inclined to join and participate in a non-democratic IO. In specification (1) of the model, we find that an increase in the FH index by one unit causes a ceteris paribus increase of 7.8 units in the number of agreements that are signed by each CIS member. For example, if Tajikistan managed to improve its level of democracy from 6 (its actual level) to 3 during the 2006–2010 time period, this nation would be expected to reduce the number of CIS agreements in economic area that it signed by 23.4 from its actual level of 182 agreements (for comparison, Ukraine signed 114 agreements during this period). Second, in accordance with Hypothesis H2.2 (the structural power argument) but contrary to Hypothesis H2.1 (IO-as-a-commitment-device), economic reforms have a persistent and positive impact on levels of CIS participation. In specification (1), an increase in the EBRD score by 1 unit increased the number of agreements that were signed by 24.82 units. If Kazakhstan (with an average EBRD score of 2.98 in 2006–2010) were as unsuccessful as Turkmenistan (with an average EBRD score of 1.39) with respect to marketization, Kazakhstan would have signed 39 fewer agreements in the economic area, which would reduce its overall number of agreements signed (169) by approximately one-fourth.

With respect to the results regarding economic reforms, we should also stress a second set of explanations that may be applicable to certain CIS countries. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, individual countries demonstrated various degrees of dependence on post-Soviet economic and political ties. One of the reasons that certain countries were unsuccessful in achieving economic independence and were forced to resort to Russian support was the presence of significant external threats to these nations or the strong possibility of internal conflicts within these countries. Because of their long-established historical traditions, these countries were strongly motivated to maintain their ties with the CIS but also sought to advance economic reforms to strengthen their position in external conflicts, overcome domestic pressures (Doner et al. 2005), and receive support not only from Russia but also from various extra-regional entities, such as the EU, the US or the World Bank (Obydenkova 2012). The three countries that best fit this pattern are Armenia (which engaged in conflicts with Azerbaijan), Kazakhstan (which included large Russian minorities and was exposed to the strong threat of irredentism) and Kyrgyzstan (which possessed limited economic resources and experienced tensions between the populaces of its northern and southern regions), which have been among the most successful CIS nations with respect to implementing economic reforms. This explanation, however, appears to apply only to certain CIS countries. Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia did not react to their vulnerability by increasing their cooperation with Russia (although these nations were also unsuccessful until the second half of the 2000s with respect to implementing economic reforms).

As a robustness check, we re-estimate our regressions using negative binomial and Poisson regressions (using different ways to include fixed effects in this setting). We also replicate our results but use the DD indicator, the Polity IV indicator, or the FH Nations in Transit indicator of democracy. We find that our results are robust for different measures of democracy and various estimation techniques. In addition, the magnitude of effects remains large in the negative binomial regressions (which are estimated using the CLARIFY program (King et al. 2000; Tomz et al. 2003)), and the binomial regression model possesses a high goodness of fit.Footnote 17 Furthermore, as we mentioned above, the way in which we define the observations in our analysis may be problematic for various reasons. Thus, we also check our results using a different approach: we calculate the total number of agreements that were signed by each country in all areas of cooperation over the course of a particular time period and regress this total on democratization and marketization variables, log GDP, and time and country fixed effects. The results from this approach are reported in Table 2 (and the corresponding negative binomial results are provided in the Supplementary Material). We completely confirm our results for the FH index (although not for all of the other democracy indicators). However, if we shift from using 5-year increments to examining annual data, we find strong and significant results regardless of the way in which we measure democratization. These results are consistent with the findings that we have reported above. The partially insignificant results in the examination that assessed 5-year increments were most likely driven by the low number of degrees of freedom; given that these increments only produce 48 observations, the fact that we obtain significant results at all is striking and strongly supports our hypotheses.

Exit options

Both of our results suggest that participation in the CIS is heavily driven by the structural power of individual countries, i.e., the availability of exit options. We can use several additional tests to corroborate these findings. First, we examine the interaction between the economic reforms index and the share of intra-regional trade. If economic reforms strengthen participation in the CIS because they provide more palatable exit options, one would expect this effect to be weaker for countries that are more dependent on CIS trade ties because these countries should also have weaker exit options. For our main specification (using OLS and the FH index), the interaction term is insignificant. However, if we either replace the FH index with the Polity IV index or use negative binomial regressions, we obtain a significant and negative interaction term.Footnote 18 This result is consistent with our main argument, indicating that states with more marketized economies and weaker levels of trade dependence on the CIS are more likely to increase their levels of CIS participation. However, we should note that the share of CIS trade and marketization variables are substantially correlated (with a correlation coefficient of −0.66); thus, these estimates may be subject to multicollinearity problems and should therefore be regarded with caution.

Second, we look at a set of additional variables that could measure the exit options of the CIS countries. This exercise is also important to ensure that our results for democracy and economic reforms are not driven by an omitted variable bias. Our main check is associated with the role of energy dependence. Indeed, this factor is of extreme importance for both energy-exporting countries and energy importers in the CIS. The latter are often heavily dependent on other CIS countries, particularly Russia; this dependence severely restricts the exit options of these countries. The former are particularly dependent on Russia for routes of energy export. Russia controls the access of most of these countries to international markets because it possesses large portions of the network of energy pipelines that are available to these nations (although significant improvements have occurred with respect to this consideration over the course of the previous few years). Very often, we observe the mutual interdependence of countries that lie along these pipeline networks. However, access to energy resources could also significantly influence domestic democratization and marketization (as suggested by the resource curse and rentier state literature). Thus, we control for the following variables: (a) the ratio of crude oil extraction to petroleum consumption in the country, which we label “resource independence” and calculate based on data from the Energy Information Administration (EIA)Footnote 19; (b) crude oil exports in thousands of barrel per day, which are again obtained from EIA data; (c) the crude oil exports to the CIS; and (d) the share of oil exports that are attributed to the CIS (extracted from data provided by the CIS Interstate Statistical Committee).Footnote 20

After controlling for these variables, we continue to be able to confirm our main results for democratization and marketization. Resource variables are highly significant and have an effect that is consistent with the predictions of informal governance theory. Countries with low oil independence are more vulnerable to manipulation by Russia and can encounter energy-related pressures from Russia. Unsurprisingly, then, we find that higher energy independence is positively correlated with the number of agreements within the CIS that a CIS member country accepts. Countries that export more oil are also more likely to increase their level of participation in the CIS because their resources provide them with an attractive exit option. However, this effect changes if we introduce an interaction term that considers the share of CIS exports; for countries with large exports of oil to the CIS, the marginal effect of oil exporting actually becomes negative. The structural power of these countries is severely weakened because their resources are primarily exported either to the CIS itself or through CIS territory; therefore, these countries have fewer realistic options for exiting the CIS.

Geography may also be an important factor that influences the exit options that are available to individual countries. One key factor in the post-Soviet region that has received attention in the extant literature (e.g., Lankina and Getachew 2006; Obydenkova 2008) is geographical proximity to Europe. Because we ran fixed effects regressions, it is not possible to simply include this variable in the set of covariates; however, we can investigate the interaction between geographical considerations and the key explanatory variables of this study (the EBRD index and the FH index). To capture geographical proximity to Europe, we calculated the distance between the national capital of each examined nation and Brussels (in kilometers). If we include these interaction terms into the set of covariates, we continue to obtain significant direct effects of democratization and marketization, which maintain their signs and significances. However, the interaction terms are also significant. We find that non-democracies are indeed more likely to increase their level of participation in the CIS, however, this effect is stronger for countries that are closer to Europe. With respect to the marketization, we also find that more marketized countries are more likely to increase their participation in the CIS but that this effect is weaker for nations that are closer to Europe. The first result may relate to the fact that non-democracies in Europe experience significant restrictions in obtaining access to other regional IOs (because the EU has very strict rules in this respect) and are therefore forced to participate in the CIS. The second result may reflect the aforementioned phenomenon that certain active countries in terms of CIS participation in the Central Asia and Caucasus regions are also more advanced in terms of marketization.

Hypothesis 3

The third hypothesis we intend to investigate suggests that decisions to increase the level of participation in the CIS could be area-specific and vary across different types of agreements. To investigate this conjecture, we re-estimated separate regressions for each of the six policy areas that we examined (Table 3 for OLS and Supplementary Material for negative binomial regressions). There is another reason why this approach is important; namely, if the costs and benefits of participation in the CIS are area-specific, then the practice of pooling data over different areas would be a questionable analytical approach. For the FH measure of democracy, our model’s findings remain significant and robust for OLS and negative binomial regressions only for two areas: economic cooperation and the organization of the CIS. For the negative binomial regressions, the model’s results are also significant for military cooperation, whereas for OLS, the model’s results are significant for political and legal cooperation. For the Polity IV measure, the results are significant for both the OLS and negative binomial approaches with respect to military cooperation and the organization of the CIS, and significant negative binomial results are obtained with respect to economic cooperation; by contrast, we find no robust results if we consider the DD index. This result is very much in accordance with Hypothesis 3. Both military aspects and political and economic cooperation (in an environment that involves the transformation of the planned Soviet economy and the requirement to address the disconnection of economic ties between countries) are clearly more important for CIS countries than cooperation with respect to social, humanitarian or even legal issues (which primarily refer either to purely technical aspects of the functioning of the CIS or to cooperation in the area of civil litigation). Military, political, and economic considerations also constitute topics with large potentials for conflict. For instance, in the economic realm, potential conflicts include the division of common property that remains from the era of the USSR, trade tariffs and conditions (which affect multiple enterprises that possess cross-border trade relationships) or prices for key commodities; in the military field, putative conflicts may arise regarding the status of common borders, border disputes, the presence and status of military bases abroad and the use of common military facilities by CIS nations. The organization of the CIS is also clearly important for CIS function because this organization determines both the formal governance institutions for the CIS and the opportunities for the leading state of the CIS to engage in manipulation.Footnote 21

Robustness checks

To validate our findings, we performed a battery of robustness checks. We (a) use a log dependent variable; (b) modify the way in which we treat fixed effects and cluster standard errors in the regressions; (c) extend our measure of agreements by including agreements that were signed with a caveat or reservation in the count of agreements that we use as our dependent variable; (d) exclude individual countries from the regression; (e) replicate our results with different periodizations, including regressions that use each year as a separate observation; (f) examine the interaction between the variables of democratization and marketization; (g) calculate the dependent variable as a percentage of the total number of agreements signed in a particular period and as a percentage of the agreements that were signed during a particular period by Russia; (h) control for the trade dependence to Russia in particular; and (i) control for access to foreign aid from the EU, the US and the IMF. Our results demonstrate a high level of robustness throughout the course of these modifications.

6 Conclusion

The aim of the paper was to examine the impact of political regimes and economic reforms on countries’ levels of participation in a non-democratic regional IO, i.e., an international organization in which most of the organization’s members and the leading state are non-democratic. Our hypotheses were derived from two main arguments in the extant literature. The IO-as-a-commitment-device argument suggests that participation in a regional IO is driven by the willingness of countries to credibly commit to implementing democratization and economic reforms. The informal governance argument suggests that participation in a regional IO is driven by the structural power of the member states, which affects their vulnerability to manipulation by the leading state. For the non-democratic IOs, both arguments suggest that democratization and level of participation should be negatively correlated, given that non-democratic IOs cannot be used as credible commitment devices and that although the threat of manipulation from a non-democratic leading country may be particularly high, higher levels of structural power are possessed by non-democracies than by democracies. With respect to marketization, the predictions of the two aforementioned arguments differed. The IO-as-a-commitment-device argument would imply that countries that are more advanced in terms of economic reforms should be less likely to participate in non-democratic IOs because these IOs cannot be used to generate credible commitments. From the informal governance argument, marketized countries should be more likely to participate in non-democratic IOs because these countries possess a greater range of feasible exit options to address potential manipulations.

In this paper, we used the case of the CIS as an empirical example of a non-democratic regional IO. Our findings were consistent with the predictions of the informal governance literature. We showed that democratization results in lower levels of participation of individual countries in the CIS. By contrast, marketization is associated with higher levels of participation in the CIS. In addition, several further tests confirm the importance of exit options for CIS participation. We show that countries with higher levels of energy independence display higher levels of participation in the CIS and that the effect of marketization is weaker for countries with greater share of intra-regional trade (as these countries are more dependent on the CIS and have fewer palatable exit options). In addition, we demonstrate that the effects of democratization and marketization are significant for areas of cooperation that display greater potential for conflict and insignificant for less important topics.

Caveats exist regarding the possible global implications of the findings with respect to other non-democratic IOs. First, the CIS is unusual because it is the direct descendant and product of the USSR. Thus, it is non-trivial to find IOs that are equivalent to the CIS in the modern world, although certain partial equivalents (e.g., in the post-colonial world) could constitute intriguing subjects of investigation. Second, the verification of the global implications of this study’s findings would require additional data collection and the launching of a new project to test this hypothesis. The inclusion of this type of project in this paper would have radically shifted the focus of this study from its main topic of investigation. However, the tendencies that were observed in the case of the CIS may hypothetically be found in other non-democratic IOs; this possibility should be examined through future research.

Notes

Examples of this type of IO include the Gulf Cooperation Council, the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America, ASEAN (during the early years of its existence) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

For example, there is much debate regarding whether EU decision-making processes are democratic. However, by the standards of the definition that is provided above, it is a democratic IO.

Compared with democracies, non-democracies are generally more likely to use informal governance mechanisms in their internal political procedures (Gel’man 2012); furthermore, in non-democracies, domestic political processes are typically less tolerant of any types of restrictions to the power of the incumbent. Therefore, decisions that appear to restrict a leader’s power should be more frequently overruled by a non-democratic leader than by a democratic leader.

We use “marketization” and “economic reforms” interchangeably to refer to the extent to which market economy institutions are established and functional.

This statement does not imply that there are no other benefits of IO membership and participation during “ordinary times.” However, these benefits are equally relevant for countries with different political regimes and therefore cannot yield predictions regarding whether democratization should be correlated with levels of IO participation.

Note that although a number of papers have identified a mutually reinforcing relationship between democratization and regional cooperation, in a study of a regional IO consisting of nations that have not experienced high levels of democratization (Mercosur), Remmer (1998) finds much less evidence of the existence of this relationship.

An obvious question in this context is why Russia provides these benefits to CIS countries. One reason could be internal political gains, given that the Russian population is strongly in favor of post-Soviet integration (Rose and Munro 2008). Another benefit is ensuring that the “dormant” institutional framework of the CIS functions and can be re-activated at any point in the future.

Prior to the revolutionary wave, the CIS regularly dispatched its observers to elections in the post-Soviet countries; however, in the second half of the 2000s these practices have been institutionalized (Status of the Mission of Observers in 2004, International Institute of Monitoring of Development of Democracy, Parliamentarianism and Protection of Human Rights in 2006) and expanded.

One possible case of this type of enforcement is Russia’s support of Abkhazia during its secession war against Georgia in 1992–93. This support could be interpreted as an instance in which Russia used force to compel Georgia to join the CIS, although the empirical evidence underlying this interpretation is certainly debatable. We appreciate the remark of an anonymous referee who noted the existence of this case.

We do not include agreements from other areas into our analysis: however, these areas (e.g., inter-parliamentary cooperation) are of minor importance and produce an insignificantly small number of agreements.

All of the acts of the CIS that have been signed by CIS members (or passed by any CIS institution, which all possess an intergovernmental nature and operate on the principles of voluntary participation in each decision) have the same de jure binding legal status (although, depending on the laws of individual CIS countries, certain of these acts may require different forms of ratification). These acts refer to very different types of decisions, such as the establishment of new norms; the specification of budget contributions and allocations of funds; and personnel decisions. However, it is virtually impossible to rank these acts in terms of importance. Personnel decisions, for example, may play a crucial role in affecting the ability of Russia, the leading state of the CIS, to manipulate the organization, and greater disagreements have frequently arisen among the CIS states with respect to these decisions than with respect to more general treaties.

Although it is reported that Georgia requested permission to continue participating in certain CIS agreements (Mikhailenko 2011).

During certain time periods Russia has been more democratic than the remaining members of the CIS (see debate in Obydenkova and Libman 2012), whereas during other periods, it became less democratic than other CIS members.

Unless otherwise stated, these data are derived from the World Development Indicators.

More specifically, we set the dummy equal to 1 if the country was part of the WTO in the last year of a particular 5-year period; we also use the same convention for our robustness checks.

Unfortunately, the quality of data for this metric is rather low. Typically, data on ethnic composition are collected as part of census data; however, these census data are often not sufficiently precise to address the complex issues of ethnic identification and they may suffer from misreporting. In addition, all countries do not implement their censuses in a timely fashion. Finally, because a census is typically administered only once per decade, only 1 to 3 census observations are available for most of the examined post-Soviet states for the examined time period. Thus, we set both of these variables to be equal to the latest possible census data that are available for a particular period.

Details regarding all of the robustness checks that are not presented in the main text of the paper are available in the Supplementary Material.

We should note that the interpretation of the interaction term in non-linear models can be subject to difficulties (Ai and Norton 2003). In linear models (OLS), this interpretation should be conducted based not only on the magnitude and significance of the interaction term but also on the analysis of the changes in the direction, magnitude and significance of marginal effects, as described in Brambor et al. (2006). We follow this approach, plotting the marginal effects; the appropriate graphs are provided in the Supplementary Material.

The variable was constructed in the following way. For Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, we used the average share of CIS oil exports that were reported by the CIS Interstate Statistical Committee. If no information was available regarding this metric for a particular period, then data from the previous period or from the closest subsequent period were used. For all other countries, the share was set to zero. We had to drop Turkmenistan from this examination because no information was available regarding this nation’s oil exports during the examined time period. We also excluded Russia from consideration because of its special status in the system of CIS pipelines.

We also used a different approach in which we estimated regressions for the full sample, but relaxed the assumptions of the initial model, allowing for policy-area-specific slopes. The results of this procedure are discussed in the Supplementary Material.

References

Abdelal, R. (2001). National purpose in the world economy: Post-soviet states in comparative perspective. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80, 123–129.

Allison, P. D., & Waterman, R. P. (2002). Fixed effects negative binomial regression models. Sociological Methodology, 32, 247–265.

Allison, R. (2008). Virtual regionalism, regional structures and regime security in central Asia. Central Asian Survey, 27, 185–202.

Alvarez, M., Cheibub, J. A., Limongi, F., & Przeworski, A. (1996). Classifying political regimes. Studies in Comparative International Development, 31, 3–36.

Ambrosio, T. (2006). The political success of Russia-Belarus relations: Insulating minsk from a ‘Color’ revolution. Demokratizatsiya, 14, 407–434.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14, 63–82.

Bueno de Mesquita, B., & Smith, A. (2012). Domestic explanations of international relations. Annual Review of Political Science, 15, 161–181.

de Mesquita, B., Bruce, M., James, D., Siverson, R. M., & Smith, A. (1999). An institutional explanation of the democratic peace. American Political Science Review, 93, 791–807.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (1998). Regression analysis of count data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cameron, D. R., & Orenstein, M. A. (2012). Post-soviet authoritarianism: The influence of Russia in its near abroad. Post-Soviet Affairs, 28, 1–44.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2009). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143, 67–101.

Collins, K. (2009). Economic and security regionalism among patrimonial authoritarian regimes: The case of central Asia. Europe-Asia Studies, 61, 249–281.

Darden, K. A. (2009). Economic liberalism and its rivals: The formation of international institutions among the post-soviet states. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Doner, R. F., Ritchie, B. K., & Slater, D. (2005). Systemic vulnerability and the origins of developmental states: Northeast and Southeast Asia in comparative perspective. International Organization, 59, 327–361.

Dreher, A., & Jensen, N. M. (2007). Independent Actor or Agent? An Empirical Analysis of the Impact of U.S. Interests on International Monetary Fund Conditions. Journal of Law and Economics, 50, 105–124.

Dreher, A., & Voigt, S. (2011). Does Membership in International Organizations Increase Government Credibility? Testing the Effect of Delegating Powers. Journal of Comparative Economics, 39, 326–348.

Fang, S., & Owen, E. (2011). International Institutions and Credible Commitments of Non-Democracies. The Review of International Organizations, 6, 141–162.

Fearon, J. D. (1994). Domestic Political Audiences and the Escalation of International Disputes. American Political Science Review, 88, 577–692.

Gel’man, V. (2012). “Subervsive Institutions and Informal Governance in Contemporary Russia”, in International Handbook on Informal Governance, eds. Thomas Christiansen and Christine Neuhold. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hale, H. E. (2008). The foundations of ethnic politics: Separatism of states and nations in eurasia and the world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hausman, J., Hall, B. H., & Griliches, Z. (1984). Econometric models for count data with an application to the Patents-R&D relationship. Econometrica, 52, 909–938.

Hellman, J. S. (1998). Winners take all: The politics of partial reform in postcommunist transitions. World Politics, 50, 203–234.

King, G., Tomz, M., & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 347–61.

Kubicek, P. (2009). The commonwealth of independent states: An example of failed regionalism? Review of International Studies, 35, 237–256.

Lankina, T., & Getachew, L. (2006). A geographic incremental theory of democratization: Territory, aid, and democracy in postcommunist regions. World Politics, 58, 536–582.

Libman, A. (2007). Regionalization and regionalism in the post-soviet space: current status and implications for institutional development. Europe-Asia Studies, 59, 401–430.

Libman, A., & Vinokurov, E. (2012). Holding-together regionalism: Twenty years of post-soviet integration. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Malfliet, K., Verpoest, L., & Vinokurov, E. (Eds.). (2007). The CIS, the EU and Russia: Challenges of integration. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Mansfield, E. D., & Pevehouse, J. C. (2006). Democratization and international organizations. International Organization, 60, 137–167.

Mansfield, E. D., & Pevehouse, J. C. (2008). Democratization and the Varieties of International Organizations. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52, 269–294.

Mikhailenko, A. (2011): “Tendencii Postsovetskoi Integracii.” Svobodnaya Mysl (12)

Miller, E. A. (2006). To balance or not to balance: Alignment theory and the commonwealth of independent states. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Obydenkova, A. (2011). Multi-Level Governance in Post-Soviet Eurasia: Problems and Promises. In H. Enderlein, S. Walti, & M. Zuern (Eds.), Handbook on multi-level governance (pp. 292–308). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Obydenkova, A. (2008). Regime transition in the regions of Russia: The freedom of mass media: Transnational impact on sub-national democratization? European Journal of Political Research, 47, 221–246.

Obydenkova, A. (2012). Democratization at the grassroots: The European Union’s external impact. Democratization, 19, 230–257.

Obydenkova, A., & Libman, A. (2012). The impact of external factors on regime transition: Lessons from the Russian regions. Post-Soviet Affairs, 28, 346–401.

Pevehouse, J. C. (2002). With a little help from my friends? Regional organizations and the consolidation of democracy. American Journal of Political Science, 46, 611–626.

Remmer, K. L. (1998). Does democracy promote interstate cooperation? Lessons from the Mercosur region. International Studies Quarterly, 42, 25–51.

Rose, R., & Munro, N. (2008). Do Russians see their future in Europe the CIS? Europe-Asia Studies, 60, 49–66.

Snidal, D., & Thompson, A. (2003). International Commitments and Domestic Politics. Institutions and Actors at Two Levels. In D. W. Drezner (Ed.), Locating the proper authorities. The interaction of domestic and international institutions. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Stone, R. W. (2002). Lending credibility: The international monetary fund and the post-communist transition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stone, R. W. (2004). The political economy of IMF lending in Africa. American Political Science Review, 98, 577–591.

Stone, R. W. (2008). The Scope of IMF Conditionality. International Organization, 62, 589–620.

Stone, R. W. (2011). Controlling institutions: International organizations and the global economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tomz, Michael, Wittenberg, Jason, and Garry King (2003): “CLARIFY: Software for Interpreting and Presenting Statistical Results.” Mimeo

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to their universities, the Frankfurt School of Finance and Management and the Universitat Pompeu Fabra (Barcelona). They would also like to thank both the Ramon y Cajal program of the Ministry of Innovation and Science of Spain (Madrid) and the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad de Gobierno de España for financing the project “Influencias Externas y Democratización: ¿Eurasia contra La Unión Europea?” We are also grateful to Randall W. Stone, the guest editor of this special issue, for his insightful comments on our paper and to three anonymous reviewers of the journal for their very important suggestions and recommendations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(ZIP 945 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Libman, A., Obydenkova, A. Informal governance and participation in non-democratic international organizations. Rev Int Organ 8, 221–243 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-012-9160-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-012-9160-y