Abstract

A growing body of international relations literature examines the delegation of state authority to international organizations. Delegation is a conditional grant of authority from a principal to an agent in which the latter is empowered to act on behalf of the former. This paper explores the effect of agent permeability to interested third parties on the efficacy of control mechanisms established by principals. Our central argument is that higher levels of agent permeability are likely to lead to higher levels of agent autonomy. Because of this, principals who face a potentially permeable agent are likely to delegate more cautiously—partially, in stages, or with clear limits. We illustrate our argument with a case study of the European Convention of Human Rights and its two principal institutions, the Commission and the Court. We find that principals (contracting states) historically delegated quite cautiously to the Court, clearly concerned about the Court’s autonomy. Court behavior in its first two decades reassured principals while increasing the Court’s permeability. Over time, that increased permeability increased Court autonomy in conjunction with the Court’s growing visibility and experience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A growing body of international relations literature examines the delegation of state authority to international organizations (IOs) (Abbott and Snidal 2000; Barnett and Finnemore 2004; Goldstein et al. 2000; Moravcsik 2000; Nielson and Tierney 2003; Pollack 2003). Delegation is a conditional grant of authority from a principal to an agent in which the latter is empowered to act on behalf of the former. This grant of authority is limited in time or scope and must be revocable by the principal. In any instance of delegation, there is a central tradeoff between the gains from delegation and the agency losses that arise from the opportunistic behavior of the agent.

Two main questions arise: Why do principals delegate authority to others? How do principals structure the agency relationship to maximize their interests in a manner that is compatible with the incentives of the agents? A large literature ably addresses these two questions (e.g., Epstein and O’Halloran 1999; Kiewiet and McCubbins 1991). Generally, principals delegate to achieve the gains that come from specialization, including the expertise, decision-making abilities, and credibility that other actors can provide (Hawkins et al. 2006). Likewise, scholars have identified a number of control mechanisms that are generally thought to adequately control agent behavior, including sanctioning agent behavior through rewards and punishments.

We build on this theoretical tradition by focusing on a relatively neglected factor, agent permeability, that shapes the costs that drive delegation. We argue that agent permeability (access by third parties) has a strong influence over agent autonomy vis-a-vis principals. Generally, the higher the levels of permeability, the greater the scope of agent autonomy, though extremely high levels of permeability might actually reduce agent autonomy. We also explore one important implication of this argument: Principals who create agents with potentially high levels of permeability will be very cautious about the timing and the manner in which they delegate authority to the agent.

PA approaches suggest that principal control over agents is incomplete, but have not fully specified the alternative sources of influence over agent behavior. The dominant approach in the literature sees agent autonomy as a function of principal control mechanisms and information advantages agents have over principals (McCubbins and Schwartz 1984; Weingast 1984). More recently, a revisionist position in the literature suggests that agents are more active than previously suspected in shaping the political context in which they act. Moe (2006) sees agents as active in shaping the composition of their principals—his example is U.S. teachers who seek to influence the composition of their own school boards. Barnett and Coleman (2005) argue that agents can increase their own relevance and resource base. This paper shares this revisionist emphasis on agent action, but focuses instead on agent efforts to leverage the role of third parties in the PA relationship. Specifically, we stress that third parties such as NGOs, interest groups, and businesses are a potential source of agent autonomy whose importance should grow along with their access.

Of course, principals are not blind to permeability issues and realize that third-party access may create more autonomy in the agent. Yet principals may still delegate, either because the payoffs from such delegation are still high relative to the evident costs and risks or because they lack ex ante information about how successfully they can control the agent or to what extent circumstances may change. As a result, principals delegating to agents with potentially high levels of permeability are likely to be very cautious about that delegation, often delaying delegation as long as possible while they verify agent behavior and delegating only partially or for limited periods of time.

The paper proceeds by first fleshing out these arguments and then by illustrating them through a Cold War-era case study of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and its two main organizations, a Commission (defunct after 1998) and a Court. The ECHR is among the world’s most important and influential IOs. A comprehensive survey of 32 member states found that every one has had to change important domestic policies, practices or legislation in response to ECHR rulings (Blackburn and Polakiewicz 2001; see also Shelton 2003). Nor are these rulings limited to a few prisoners in a local jail cell. Rather, they affect domestic policies and institutions with broad scope. For example, the Court has required Great Britain to reform its sodomy laws, allow gays in the military, curtail wiretapping and other police powers, and ban corporal punishment in public schools (Jackson 1997; Stiles and Wells 2007). In Turkey, the Court has ruled repeatedly against the government’s security policies with respect to Kurds, including a March 2003 ruling that Abdullah Öcalan—the well-known Kurdish guerrilla leader—received an unfair trial. Despite Court rulings against states in increasingly important and contentious issue areas, state compliance is so routine that top legal scholars argue that the Court has “almost uniform respect and obedience rendered to judgments” (Janis et al. 1995: 8). But it was not always so. Before gaining compliance, the Court first had to win autonomy without losing state respect for its decisions. Our case study traces the long, slow development of Court autonomy during the Cold War era, from 1949 to 1990.

In using this case, we add novel information on the ECHR to the literature on international courts (ICs) and IOs, and we create new connections between that literature and a general principal-agent approach that has been used to analyze a wide variety of economic and political phenomena. While the existing literature on ICs is rich and sophisticated and marked by higher levels of agreement than once existed, important questions involving the interaction between states and ICs remain unanswered (Alter 1998; Burley and Mattli 1993; Cichowski 2004; Conant 2002; Garrett 1995; Garrett et al. 1998; Kelemen 2003; Keohane et al. 2000; Mattli and Slaughter 1998; Stone Sweet 2004; Weiler 1991). One such question concerns whether ICs can even be fruitfully compared to other IOs or whether they are fundamentally too different. Consistent with most theoretical treatments of IOs, we include ICs under that rubric, yet we are cautious in generalizing from our case since it is possible that ICs act differently with respect to permeability and autonomy than other IOs.

Our analysis enriches the existing debates about delegation and autonomy in IOs and ICs. Many IO scholars view agent autonomy as a design choice of the state principals (Koremenos et al. 2001) or as a result of agent information (Weingast 1984). Much of the IC literature, however, suggests that autonomy is a result of third-party permeability or accessibility (Alter 1998; Keohane et al. 2000). Where ICs are relatively open to individual complaints, they are more likely to act autonomously. Our analysis generally confirms the importance of permeability as a source of court autonomy in a case other than the ECJ, but we show how this can work within a PA approach. In doing so, we offer a bridge between the IO and IC literatures and suggest that IO scholars should take permeability more seriously. While some scholars argue that courts are not agents (Alter 2006), states and ICs meet our definitions of principals and agents because states originally set up the ICs and can withdraw from their authority or disband them while the converse is obviously not true.

The link between permeability and autonomy has important implications for principal efforts to delegate in the first place. Much of the current PA literature suggests that principals delegate for functional reasons: to gain information or credibility and to cut transaction costs. Such arguments may be found among studies of both IOs generally (Hawkins et al. 2006) and ICs specifically (Alter 2006; Garrett 1995; Pollack 2003). In perhaps the most influential study of the ECHR, Moravcsik (2000) argues that states established the regime in order to prevent domestic backsliding on democratic commitments. These theoretical approaches do a fine job of laying out the benefits of IOs and ICs, but pay less attention to the costs (Goodliffe and Hawkins 2006). Agent permeability can increase those costs. The higher the levels of potential permeability, the more cautious principals should be about delegating in the first place. As our empirical analysis will show, states frequently delayed delegating to the ECHR while they examined the behavior of the Commission and the Court. Other states delegated in a gradual and incremental fashion that also is not fully anticipated by theories that focus only on the benefits of IOs without emphasizing state concerns about potential costs. Those potential costs included not merely IC autonomy, which states indeed sought to control, but also agent permeability, which, over time, generated a new source of agent autonomy and hence potential new costs for states.

2 The Effects of Agent Permeability

Agents receive conditional grants of authority from a principal, but agents do not always do what principals want. Existing literature contains two concepts that cover different aspects of this basic insight. Agency slack is independent action by an agent that is undesired by the principal. Yet principals may well want agents to have some scope for independent action. Autonomy is the range of independent action available to an agent after the principal has established mechanisms of control by selecting screening, monitoring, and sanctioning mechanisms intended to constrain agent behavior. Thus autonomy is broader than slack: autonomy is the range of independent action that is available to an agent and can be used to benefit or undermine the principal, while slack is undesired behavior actually observed (Carpenter 2001; Huber and Shipan 2002; Pollack 2003). We focus in this paper on autonomy.

While much of the PA literature has naturally focused on principals and agents, we wish to draw attention to third-party actors that can influence this relationship, and especially those with direct access to the agent. Principals are identified by the fact that they grant authority to others by means of a contract. A wide variety of third-party actors do not grant authority but nevertheless seek to influence the agent. In the international arena, such external actors may include states who are not principals, nongovernmental organizations, businesses, churches, or other interest groups or individuals. Their motives range from material self-interest to principled values, and their efforts to influence the agent are likely to increase as the agent gains more authority. Third-party actors might seek to influence the agent by first influencing the principal, as Nielson and Tierney (2003) have argued with respect to environmental groups seeking to alter the World Bank’s practices. Our concern, however, is in examining third-party actors who seek to influence the agent directly.

The comparative social movement literature has probably made the most progress in conceptualizing institutional characteristics (usually of states) that are amenable to third-party influence. Tarrow (1994: 85) defines political opportunity structures as “consistent—but not necessarily formal or permanent—dimensions of the political environment that provide incentives for people to undertake collective action by affecting their expectations for success or failure.” The well-known difficulty with this definition is that it covers a variety of components that vary widely by the scholar who operationalizes the term (Meyer and Minkoff 2004: 1459–60). These factors—historical precedence, cultural understandings, institutional rules, political allies, and so forth—do not necessarily covary, and hence it seems better to disaggregate the term into its component parts and focus on those that are likely to have the greatest influence.

Institutional permeability, a continuous rather than a discrete variable, can be conceptualized as the extent to which formal and informal rules and practices allow third-party access to agents’ decision-making processes. Access rules comprise three dimensions: the range of groups that are allowed to participate, the decision-making level where the third party gains access, and the relative transparency by which decision-making is conducted. The most accessible institutions are open to an array of third parties regardless of political ideology, national origin, or other criteria. Highly accessible institutions grant access at the most important decision-making levels. They also hold open meetings and debates, issue reports that provide reasons for their decisions and facilitate knowledge of institutional procedures. At the other end of the spectrum, impermeable institutional rules carefully select the third parties who may gain access, limit their access to peripheral decision-making levels, and refuse to provide them with information. In their analysis of court accessibility, Keohane et al. (2000) focused only on the first dimension of range of third-party access. This focus could easily be misleading in cases where anyone can formally participate, but where their participation is limited to peripheral issues and bodies or where their information about the decision process is limited.

Due to substantial variation in the function and structure of IOs, it is difficult to create a single operational list for measuring these dimensions. No court, for example, would allow third parties into chambers where decisions are actually made, but some UN bodies allow third parties to be present during decision-making debates. Yet both courts and political bodies are agents, and both are subject to third-party influence. Hence, we lay out a fairly generalizable operational scale, recognizing it may have to be modified for particular cases, depending on the issue area or functional purpose under study.

Range of access, the first dimension, refers to the range of social and political actors who can bring information or arguments to the attention of the agent, either through formal legal mechanisms or informal consultations. Some organizations have few if any formal rules allowing third-party access, such as the Security Council and the Permanent Court of Arbitration (Keohane et al. 2000: 462–466). At moderate levels, third-party communications are first screened either by governments or by other IOs. For example, businesses claiming unfair trade practices elsewhere must first convince their own government to bring suit in the World Trade Organization, and individuals suffering human rights violations in the Western Hemisphere must first persuade an independent commission to bring a case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. The highest range of access is available when a wide range of actors can present information and arguments to an agent at relatively low cost and with no pre-screening by another body. Although such cases appear to be rare, examples include various human rights committees, such as the Committee on Children’s Rights, where some states allow direct individual petition.

In the second dimension, the decision-making level at which access is granted, third-party access may be banned altogether or limited to peripheral issues on the low end or include direct access to key decision-making bodies on the high end. The WTO dispute settlement panels fall near the low end because although anyone can file an amicus curie brief (thus, the range of potential third parties is high), the panels in practice accept few of them due to state objections, and third parties have no other avenues for making their case. At moderate levels, IOs allow third-party information and comments on a variety of their activities but shield key decision-making processes from third-party input. The World Bank, for example, has a variety of fora in which civil society actors can speak directly with Bank officials, including strategic policy workshops, and an electronic Development Forum, but allows no access to weekly board meetings or to staff discussions on loans. IOs with high levels of permeability allow third parties to provide information or arguments in the most important decision-making fora. A prominent example is the Preparatory Commission to create an International Criminal Court, where NGOs interacted intensively with national delegations in the negotiating process (Benedetti and Washburn 1999).

In the third dimension, transparency, impermeable IOs provide little information about either the process or the substance of their decision-making to third parties. NATO, for example, allows some third-party participation via an inter-parliamentary assembly, but never divulges much information used in its decision-making process or an explanation of how the decision was made. IOs with moderate transparency release some decision-making information and disclose their logic after reaching the decision, as when courts publish their rulings and dissents. High transparency IOs offer access to almost all of the same information they have and allow third parties to observe government positions during the negotiation process, a practice that is fairly common in UN committees tasked with drafting treaties.

We hypothesize that the higher the level of permeability, the higher the level of agent autonomy.Footnote 1 By definition, higher permeability means that a wider array of third parties can access the agent at more important decision stages with better information about the agent’s decision process. Permeability allows third parties the opportunity to provide information and arguments that strategic agents can choose to utilize in their decisions or that influence agents to alter their behavior. Because agents lack information and need information to carry out their tasks, shaping the nature of the information reaching agents can also shape agent decisions. Principal-agent theorists have long recognized agent information as a key source of agent autonomy (Hawkins et al. 2006; Kiewiet and McCubbins 1991: 25; Martin 2006). Where agents are exposed to a wider range of third parties, they are more likely to encounter information that they can use to shape their decisions and to act contrary to principal preferences, should they choose. Martin (2006) uses the example of International Monetary Fund staff using specialized information about political and economic situations to shape lending decisions in ways that run counter to principal preferences. Some of that information is provided by third parties with access to the Fund.

In addition, third parties can use their access to define problems and identify solutions and to persuade agents of their views. These mechanisms differ from pure information-provision because they result in deeper conceptual changes in agent worldviews, provide new ways of categorizing and thinking about problems, and even alter agent preferences and values. Barnett and Finnemore (2004) have argued that agents matter because of their ability to create categories that identify ways of perceiving the nature of problems and solutions. While agents can create their own categories, problem definitions, and solutions, it also seems likely that they will look for ideas provided by others. Along the same lines, third parties routinely engage in dialogue and argumentation that could persuade agents of their viewpoints (Checkel 2005). Where third parties can access key decision-making functions and are not limited to providing information in agent-defined schemas and categories, they are more likely to influence agents through concept-definition and persuasion. Where third parties and agents can interact on relatively equal terms, persuasion and learning is more likely to occur (Risse 2000). The more third parties know about agent preferences and decision-making through transparency, therefore, the more likely they are to engage in influential dialogue and persuasion. By way of illustration, when the UN General Assembly tasked a Preparatory Committee to prepare a draft statute of an International Criminal Court, the Committee allowed extremely wide access to NGOs supporting the Court. These NGOs played a key role in conceptualizing the Court in terms of the demands of justice rather than as a tool for states to employ (Benedetti and Washburn 1999; Fehl 2004).

None of this implies that third parties set out to create more autonomy in an agent or that they are even aware of principal-agent dynamics. In many cases, third parties undoubtedly simply want to win a particular case, insert wording into a specific contract, or redistribute money toward a clearly delimited problem. Yet savvy agents can use these opportunities, especially as they accumulate, to explore a wider range of behaviors than they had previously (Hawkins and Jacoby 2006). Agents are strategic actors in their own right, not the passive tools of either principals or third parties. Self-interested third parties provide the raw materials (information, arguments) for agents to expand their own autonomy. Agents are capable of picking and choosing which third-party information and arguments they wish to utilize to reach and justify decisions. Where third parties have a broader view of agent behavior and call for more systematic reforms (as with the NGOs calling for reforms in the World Bank and IMF), strategic agents can either use or fail to use those efforts in conjunction with particular cases or more myopic third parties to achieve outcomes they desire.

Third-party influence on the agent does not imply that the agent automatically has more autonomy vis-à-vis principals. Strategic agents might prefer not to carve out more autonomy because their preferences align with those of the principals. Alternatively, third parties might actually influence an agent to conform more closely with the preferences of the principals. This logic underlies the whole idea of fire alarms and police patrols in the principal-agent literature, where third parties report on agent activities to principals so the principals can reign in the agents (McCubbins and Schwartz 1984). In our view, however, police patrols and fire alarms imply relatively low levels of permeability because principals usually structure these mechanisms in such a way that not all third parties can engage in police action or can pull a fire alarm. Moreover, third parties have rather limited access to agent decision-making in such cases; they mostly have the ability to warn others of agent behavior. As a result, the idea of principal-sponsored third-party monitoring is completely consistent with our argument that lower levels of permeability help produce lower levels of agent autonomy.

This argument raises two additional issues: Why do principals delegate in the first place to agents with high permeability or potential permeability? Why don’t principals recontract to reduce high levels of permeability? High permeability can occur either through principal design, the strategies of third parties, or the efforts of agents. While agents have more specialized knowledge than principals, they often have less information than third parties. Hence, principals might design higher levels of permeability in order to provide agents with more third-party information to better perform their tasks. Principals know of course that information can lead to influence and in designing permeability they accept those risks. Other times, agents work to increase their own permeability by opening themselves to access by third parties. Agents are likely to prefer higher levels of permeability when they are committed to improving outcomes and need better information or when their preferences diverge somewhat from those of the principals and they can use third-party information or preferences to justify their actions to the principals.

Principals, in this model, are sensitive to these possibilities. Where permeability is high or seems likely to grow over time, principals are likely to be more cautious about delegating in the first place. This is a major testable implication of our argument. Principal-agent theory already expects principals to be cautious. Kiewiet and McCubbins (1991: 29–31) argue that principal screening and selection are essential because it is frequently too costly for principals to impose workable sanctions on agents already hired. When agent permeability is likely to be high, however, there is an additional, if subtle, implication: principals may choose to do the job themselves or cooperate with others without formal delegation rather than delegating authority to an agent. Our claim, then, is not just that principals choose to delegate and then select a good match from available agents (e.g. the well-established screening and selection argument), but, when permeability is high, they examine agent behavior carefully before deciding whether to delegate in the first place.

This argument highlights the dynamic and fluid nature of the delegation decision. Whether to delegate is not itself a single decision, but rather is likely to be disaggregated by states, who are likely to pursue delegation in incremental steps, avoiding sudden “lock-in” even when such commitments are otherwise in their interests. Principals anticipating possible agent autonomy due to permeability will make initial commitments in incremental ways.

With regard to the second issue, the PA literature suggests that principals can and do recontract to reign in wayward agents. We do not disagree, but we do note that recent studies suggest that recontracting is quite difficult, especially within a collective principal as characterizes many IOs (Nielson and Tierney 2003). Moreover, the gains from delegation may still outweigh the costs of expanded agent autonomy, leaving principals without strong motives to recontract. Thus, we are not arguing that principals are blind or indifferent to expanded agent autonomy. Principals will still react (or not) depending on their specific costs and on whether the expanded autonomy brings them unexpected benefits. Put differently, we are not arguing that principal demand for agents is highly inelastic; indeed, states may exit international organizations if the costs grow too high. Rather, our main point here is that once principals have delegated, it changes the political dynamic between agents and principals by offering opportunities and incentives to third parties.

3 Case Study: European Convention of Human Rights

We illustrate the arguments above by examining the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and its two main organizations, the Commission and the Court, from their founding until the end of the Cold War in 1990. Their prominence and influence make them an important subject for study. The ECHR is a good choice from the research design perspective because the Commission’s and Court’s permeability and autonomy changed over time, as did the number and types of states delegating to these institutions, thus offering opportunities to analyze changing relationships among these variables. Because principals endow judicial bodies with substantial autonomy in order to fill their functional tasks, the case also poses a relatively difficult test for the argument that additional autonomy results from third-party permeability rather than principal preferences. Because we focus on permeability and autonomy, the empirical sections that follow are out of order chronologically. We first explain how and why the Commission and the Court gained permeability and autonomy, a process that occurred from the 1960s to the present. We then explain how and why states would delegate authority to a Commission and Court that they had reason to fear might gain more permeability and autonomy, a process that occurred from the 1950s to the 1970s.

Though ECHR permeability and autonomy continued to rise after the end of the Cold War, we limit our investigation to the Cold War period. We take this route because other factors affecting Commission and Court decision-making also changed dramatically after 1990, making it difficult if not impossible to sort out the effects of permeability on autonomy. Variation in an independent variable is less useful when it is highly correlated with variation in other relevant independent variables such as the centrality of the Court to European identities, the rise of soft forms of EU conditionality pushing ECHR membership for prospective member states, and power differentials between existing ECHR members and those seeking membership. None of those factors seem centrally important from the 1950s to the 1970s, but all became very important after 1990. The existing literature on international courts certainly emphasizes structural changes wrought by the end of the Cold War. Merely focusing on the ECHR alone, existing scholarship emphasizes several major shifts including the shift from a focus on protecting individual rights to a major emphasis on protecting minority rights (Furtado 2003), the struggle over whether to protect “pre-existing rights” or promote “fresh policy initiatives” (Kay 1993), or the tension between protecting pluralism and promoting democracy (Leuprecht 1998). After 1990, therefore, the ECHR undergoes some fundamental changes, and the states seeking to join do not face the same set of choices as those faced earlier. A truly comprehensive account of the effect of permeability on Court autonomy would have to control for more variables than we are able to account for in this paper.

Using the ECHR as a case study also raises the question of whether judicial institutions are fundamentally different from other IOs with respect to permeability. While a full examination of that issue is well beyond the scope of this paper, two features essential to judicial institutions make them more permeable and more prone to autonomy: their mandates require them to listen to both sides of an argument and to reach decisions based on legal principles rather than political influence.Footnote 2 While it seems likely that non-judicial strategic agents also have incentives to listen to all sides of a dispute and search for apolitical grounds for decisions, we acknowledge that judicial institutions are particularly biased in these directions, thereby encouraging caution in thinking about the generalizability of this case study.

3.1 Permeability and Autonomy

Adopted in 1950, the ECHR went into effect in 1953 when a sufficient number of states had ratified it.Footnote 3 The Convention committed states to human rights principles defined chiefly in terms of civil liberties and political rights, excluding social and economic rights. The Convention created a Commission, which began operating in 1954, that processed complaints about human rights violations, weeded out those that did not meet the criteria for admissibility, gathered information about the cases, attempted to reach friendly settlements between the disputants, published reports and recommendations, and forwarded unresolved disputes to other decision-making bodies.Footnote 4 In 1959, a Court was established when a sufficient threshold of states accepting its jurisdiction was reached. States delegated to the Court the ability to decide if the Convention had been violated and to pass binding judgments requiring states to alter their practices. When European states disbanded the Commission in 1998, they transferred its functions to the Court.Footnote 5

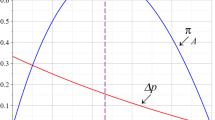

We measure autonomy as the percent of Court rulings against states, a measure consistent with the definition of autonomy in the literature on judicial politics (Helmke 2002; Larkins 1996). We measure the Commission and Court’s permeability by examining both their official rules regarding access and the number and percent of complaints admitted by the Commission. A measure focusing only on the former would neglect the possibility that formal rules do not always translate into actual practice, and such paper permeability would not have the expected effects on the agent. A measure focusing only on the latter would neglect the possibility that those numbers do not measure changing permeability but rather something more limited, such as visibility. Our central claim in this section is that the permeability of both institutions was an important factor in increasing Court autonomy. We also show that this increasing permeability was not the result of state decisions. Rather, states reacted to a agent-led increases in permeability by finally accepting the expanded permeability in 1994.

Our unit of analysis for autonomy is a Court finding of a violation or nonviolation of a substantive Convention article, where each judgment issued by the Court (pertaining to a particular case) often has more than one finding.Footnote 6 In each judgment, the Court itself identified the number of findings for and against states. Our data simply adopt the Court’s coding of its own judgments. Looking at judgments (cases) as a whole would present serious aggregation problems: If the Court rules against states on one of three substantive issues in a given judgment, does the judgment count as for or against states? Hence, it makes more sense to disaggregate the judgments and to look at individual findings reported by the Court. As the last column in Table 1 demonstrates, the Court ruled against states 25% of the time in the 1960s and 1970s, but this increased to around 50% in the 1980s. These contrary rulings cannot be dismissed as a simple matter of the Court ruling against states in obscure and isolated cases, especially because the increase in negative rulings came at the same time as increases in the number of cases decided.Footnote 7 Moreover, during this period the Court was increasingly exercising its authority in key public policy issues, including security issues.Footnote 8

What drives this increase in agent autonomy over time? Pollack (2003) and Garrett et al. (1998) argue that principal interests and control mechanisms determine the range of agent autonomy. Where agents, such as the European Court of Justice, have enormous autonomy, it is because principals have designed control mechanisms that way in order to resolve information and credibility problems facing the principals. In this view, the range of agent activity depends on principals. This argument constitutes a useful starting point for analyzing the Court. From the beginning, states imposed relatively few control mechanisms on the Court, suggesting that they intended it to enjoy substantial autonomy. But states did insist on some crucial limits. The most important control concerned permeability; in particular, procedural rules governing access to the Court. States attempted to limit individual access to the Court in a variety of ways. The most important were treaty clauses that treated both an individual’s ability to petition the Commission and compulsory Court jurisdiction as optional rather than mandatory features. States were able to commit to those two measures (and rescind those commitments) separately from each other and separately from ratification of the Convention. Furthermore, states established the Commission specifically to screen individual applications, and allowed only the Commission or states (not individuals) to take cases to the Court. Of equal importance, states wrote rules to ensure that individuals had no standing before the Court and no way to represent themselves there, even after the Commission referred their case to the Court. States instructed the Commission to bring complaints to the Court but then to act not in the interests of the individual but rather as the “defender of the public interest.” States did not even make provisions in the rules to inform individuals of proceedings before the Court in which they were the chief complainant (Robertson and Merrills 1993: 303–310).

States did not formally alter these control mechanisms regarding permeability until October 1994 when Protocol 9 went into effect (though the Court’s permeability changed independently, as we discuss below). As a result, the nature of the controls cannot explain the Court’s increasing autonomy in the 1980s. Protocol 9 amended the Convention to allow individuals—in addition to the Commission or to states—to bring a case to the Court and to receive copies of the Commission’s reports on their cases. Prior to this protocol, states had amended the Convention several times, but never altered the rules governing permeability or other key control mechanisms. By the time states adopted Protocol 9, however, the Court’s rulings against states had been typically running about 50% each year during the 1980s, double the 25% average in the 1960s and 1970s (see Table 1).

We argue instead that agent-led increases in permeability played a key role in the Court’s growing autonomy. Individuals began to gain greater access to the Court long before states reformed the control mechanisms because the Commission and Court themselves began to alter the rules governing permeability. When they set up their control mechanisms, state principals likely underestimated the durability of these barriers to permeability. Most importantly, both the Commission and the Court operated in professional environments that gave weight to individual complainants. The Convention tasked the Commission and Court with upholding individual rights against state abuses, and Western norms of justice deem that all parties deserve to be heard in court. As a result, the Court repeatedly found that it had a fundamental duty to be fully informed of the applicant’s point of view (Robertson and Merrills 1993: 303–308).

Although states objected strongly, the Court, in a series of rulings from 1960 to 1982, chipped away at the official rules preventing direct individual access to the Court. In Lawless v Ireland, the Court’s first case, decided in 1961, the Commission informed the complainant of the Court proceedings, submitted written information from the complainant to the Court, and invited the complainant’s representative to assist it in preparing information for the Court (Robertson and Merrills 1993: 304–308). Over Ireland’s protests, the Court ruled that all the Commission’s actions were acceptable, arguing that: “The Court must bear in mind its duty to safeguard the interests of the individual....” (quoted in Janis et al. 1995: 67). Mindful of state concerns, the Court required the Commission, rather than the individual complainant, to present the applicant’s views to the Court. Ten years later in the Vagrancy cases, however, the Court went further by allowing the applicant’s lawyer to assist the Commission in the presentation of the case before the Court. Still cautious, the Court insisted that the lawyer only be able to act when called upon by the Commission to assist it and thus did not grant the lawyer an independent voice (Robertson and Merrills 1993: 307). Then in 1982, the Court amended its own rules of procedure to allow individuals to represent themselves directly before the Court.

These agent-initiated rule changes altered the Court’s permeability by allowing greater individual access in particular cases. They affected the second dimension of permeability by granting individual complainants an increasing ability to address the Court directly. They impacted the third dimension of transparency by providing individual complainants with more information about the Court’s decision-making. By 1982, the participatory role of complainants and the information they received had become much closer to that of states.

The first dimension of permeability, the range of third parties with access, was always extensive on paper but depended greatly on Commission practice. Formally, anyone claiming to be a victim could submit a complaint against states. The Commission, however, had the authority to dismiss claims that were not well-founded and had the sole discretion of whether to send a claim onto the Court. In practice, the Commission accepted only a very small percentage of these complaints for further investigation—less than 3% of the 8,352 complaints it examined from 1955 to 1979 (Table 1, Column 2). The Commission recommended even fewer of those 215 cases to the Court, which issued judgments on only 34 cases in those years, some 16% of those admitted by the Commission (Gomien 1995). Table 1 provides evidence that beginning around 1980, the Commission altered the Court’s permeability on this dimension by admitting a gradually increasing percentage of claims at the same time that the number of those claims was also gradually increasing. The result was a substantial jump in admitted claims. Column 2 of Table 1 reports the number of applications on which the Commission made a decision, which is closely related to the number of applications received and thus is best conceptualized as a measure of the Court’s visibility. As the number of applications rose, the Commission could have maintained the number it admitted in the range of two percent, its previous average (Column 3). Yet the Commission increased its own permeability by admitting a larger percentage of these growing numbers of applications, an average of eight percent of the applications in the 1980s. It increased the Court’s permeability by referring more cases to the Court. In the 1980s, the Court produced judgments on 169 cases out of 455 that the Commission declared admissible, around 37% (Gomien 1995).

This increase in permeability appears to have facilitated the Court’s growing autonomy. When the Court was issuing only a few findings each year, it did not rule much against states. From 1960–1979, the Court issued only 84 total findings (representing 34 judgments or cases; most judgments include multiple findings) and found against states just 25% of the time. But as permeability increased through both rule changes and the number and percent of cases admitted and sent to the Court, so did the percentage of findings against states. In the 1980s when the court issued from 7 to 41 findings a year, its rulings against states doubled to nearly 50%.

Beyond these general patterns, evidence that permeability fuels autonomy can be found in a number of substantive Court decisions. Once applicants were able to present their own cases, the Court frequently adopted reasoning offered by those applicants in its decisions. As the types of cases reaching the Court expanded, the Court was able to identify new issues where states were violating their human rights commitments. Any number of cases could illustrate these points, but we focus on a prominent one. In the 1979 Marckx v Belgium case, the Court reaffirmed a 1978 ruling that under certain circumstances individuals could lodge cases as “victims” even if they had never personally suffered violations. Having expanded its own permeability by allowing the petition over Belgium’s objections, the Court then ruled that Belgian law could not discriminate against illegitimate children, thereby expanding the definition of a family in fundamental ways (Ovey and White 2002: 231). The Court based this ruling on its reading of Article 8 of the Convention, which says in part that “Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life....” The wording of this article, granting individuals only a right of “respect,” and the drafting history both suggest that states wished to maintain as much flexibility as possible on these issues (Janis et al. 1995: 229–231). In this and subsequent cases, however, the Court transformed this right into “a general charter of individual autonomy” (Janis et al. 1995: 230). In the Marckx case, third-party access provided the Court with new information and, more importantly, with alternative conceptualizations of the family that have set important precedents for later Court decisions. We cannot know whether the judges actually altered their own conception of the family as a result of the arguments they encountered in the Marckx petition or whether they simply used the petition as an opportunity to assert their own preexisting views. Either way, permeability directly led to a key moment in the evolution of the Court’s autonomy.

We see four apparent alternatives to our argument that increasing agent permeability explains the increase in Court autonomy. The first alternative—that increasing autonomy is the result of state principals redesigning the Court—has already been rejected. We have shown that there were no major changes in the Court’s formal design during the period of growing autonomy and that subsequent design changes—in particular, Protocol 9 in 1994—long postdated the rise in autonomy.

Second, it is possible that increasing autonomy led to increasing permeability. This seems theoretically plausible because increasing autonomy makes efforts to engage the Court far more attractive to third parties and increases third-party pressure for greater access to the Court. Quantitative trends in Table 1 indicate that increases in each were roughly coterminous. The process-tracing evidence presented above regarding rule changes and Court decision-making, however, suggests that permeability actually preceded autonomy. The Commission and Court were altering the rules governing permeability from the Court’s first case in 1961 until the early 1980s, yet autonomy did not grow substantially until 1979 when findings against states first reached a consistent floor of around 40%. At the same time, it seems likely that once autonomy started expanding, it created a feedback mechanism that helped expand permeability, which grew steadily throughout the 1980s (Table 1, Column 3). In short, permeability and autonomy likely reinforced each other, but the Court first developed permeability and then used the increasing cases and the stronger voice that it allowed plaintiffs in those cases as the raw materials to achieve greater autonomy.

Third, it is possible that the Court exercised more autonomy because states had fully committed to the Court. This also seems theoretically plausible because strong state commitments would have allowed the Court to exercise more autonomy with fewer fears that states would exit the Court or refuse to comply. Some evidence supports this alternative because Court autonomy increased in the early 1980s, about the same time that most states had finally accepted the optional clauses of individual petition and compulsory jurisdiction (with the notable exceptions of Cyprus, Greece, Malta, and Turkey; see next section). At the same time, this hypothesis probably works better as a complement to the permeability argument. Consider a counterfactual scenario in which the Court enjoyed strong state commitments but very little permeability. Would it have increased its autonomy? We cannot know, but it would have fewer cases with which to work, fewer arguments from plaintiffs to consider, and hence fewer raw materials from which to carve out autonomy. Moreover, any increase in rulings against states in the absence of increasing cases would have been more easily interpreted as punishments for commitments rather than the natural result of a growing body of law. In practice, permeability provided both the cases and the political cover for the Court to increase its rulings against states. At the same time, increasing state commitments allowed the Court to rule against states with less fear of state defection.

A fourth alternative is that increasing Court autonomy was caused by the Court’s growing experience and its increasing visibility. Yet these mechanisms are both entirely complementary to our focus on permeability. The visibility mechanism could help explain why potential plaintiffs are aware of and drawn to the Court, but, by itself, cannot explain why their grievances are accepted by the Commission and used by the Court to limit state behavior. Similarly, the experience mechanism can explain why, as it gained experience and its officials gained confidence, the Court might become more assertive, but it underspecifies how that assertiveness is given scope to operate. Even a legally sophisticated and experienced Court needs cases and arguments with which to operate. Put differently, our explanation is theoretically neutral as to whether the source of increased autonomy lies with the second thoughts of principals (redesigning control mechanisms), the level of principal comfort with the agent (commitment), the growing capacities of agents (experience), or the rising pressure of third parties (visibility). Of these, only the first has been refuted here, but to the extent the others matter, they matter through the mechanism of permeability that we have outlined.Footnote 9

3.2 Delegation and Recontracting

We have shown that increasing Court permeability has been closely associated with increased autonomy, though that autonomy may be partially driven by other factors as well. Good arguments should generate multiple observable implications for which evidence is available. A major implication of our argument is that state principals should be able to anticipate the possibility of growing agent autonomy, and should attempt to mitigate it. One specific implication is that principals will design agents whose permeability is limited and is subject to principal checks. A second implication is that principals will delegate cautiously, in stages or with conditions, carefully observing agent practices with respect to permeability and autonomy, before delegating fully.

Our theory and the observable implications do not, however, explain why states might be motivated to delegate to the Court in the first place. Rather than devise a separate theory of those motives, we turn to the leading explanation of the ECHR, provided by Moravcsik (2000). Moravcsik argued that new or unstable democracies have incentives to “lock in” human rights and democracy policies against possible domestic authoritarian reversals by delegating authority to international institutions. According to Moravcsik (2000: 229), established authoritarian and established democratic regimes both lack this incentive to yield sovereignty to international human rights institutions because they gain little or nothing but have to pay substantial sovereignty costs. Moravcsik’s theory makes a clear prediction that new democracies will delegate and delegate quickly (lest they lose the chance through the coming of the very authoritarian reversal that they fear) while established democracies will “support rhetorical declarations” while “remaining opposed” to “reciprocally enforceable rules” (2000: 229).

Operationalizing Moravcsik’s logic, ruling governments in new democracies should be eager to secure the benefits of delegation before they leave office. Specifically, newly democratic states should delegate to the Court and Commission within 4 years of 1950, when the Convention was adopted, or, for states admitted to the Council of Europe after 1950, within 4 years of their transition to democracy. New democratic governments should want to lock in prior to ending a first term in office, and 4 years is the modal length of European parliaments.Footnote 10

Our argument implies that new democracies will be much more cautious than Moravcsik suggests. While new democracies have a motive for delegation, they also have grounds for concern. Specifically, they should delay acceptance of individual petition and compulsory Court jurisdiction beyond the 4-year “lock-in” window while they observe Court and Commission behavior with respect to permeability and autonomy and verify that those factors remain at relatively low levels. Of course, not everyone can delay delegation or the Court and Commission would never function. Hence, we expect early delegators to limit their delegation in other ways, either through sunset clauses that limit delegation to specific periods of time and are subject to renewal or through domestic rules that limit the effects of international delegation. We expect state delays to show up quantitatively in terms of the number of states actually delaying acceptance and qualitatively in the historical record in terms of state elites discussing Commission and Court behavior and citing that behavior as a reason to delegate or not. Finally, when state delegation is still in question, we expect the Commission and Court to interpret their mandate in ways that states prefer; that is, by limiting individual applications and by ruling in favor of states. In our terms, the former move demonstrates limited permeability, and the latter move demonstrates restricted autonomy.

For states to delegate authority they first had to ratify the Convention and second had to accept—in writing—the principle of individual petition and compulsory Court jurisdiction (possibly accepting one without the other). Without both individual petition and Court jurisdiction, the Convention could not realistically be enforced in that state (Moravcsik 2000). Without individual petition, cases would have to be submitted by other states—an unlikely occurrence because any state submitting a complaint could have a complaint submitted against it in retaliation. Without compulsory Court jurisdiction, states likely would not participate in Court proceedings and would be unlikely to implement principles the Court articulated in other cases. Hence, states ratifying the Convention without accepting these optional clauses in fact delegated very little authority, a point state elites were clear on at the time. Together, individual petition and compulsory jurisdiction constitute a significant transfer of sovereignty, as individuals could essentially sue their state for human rights violations in an international court with compulsory decision-making authority.

We report the dates that states delegated authority to the Commission and Court in Table 2.Footnote 11 Among new democracies from 1945 to 1990, only Portugal delegated full authority within 4 years of its democratic transition. Germany and Austria are borderline cases for Moravcsik’s argument, delegating fully only 5–8 years after 1950. Spain is also a borderline case, fully delegating 5 years (and two governments) after its 1977 democratic transition. None of these states delegated within the first democratic government’s term in office, as would be expected of governments seeking to lock in democratic gains before they lost power. Among the five other postwar democracies, France and Italy waited 36 and 28 years, respectively, while Cyprus waited 24 years, Greece 33 years, and Turkey 39 years, not including any nondemocratic interludes in those three states. Surprisingly, and contrary to Moravcsik’s expectations, some stable democracies delegated relatively quickly: Belgium, Denmark, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, and perhaps (depending on measurement) The Netherlands. It was mostly these countries, and not the new democracies, who got the Commission and Court rolling, providing a larger challenge to Moravcsik’s argument than we initially anticipated.

A necessary condition for delegation where potential permeability is high, according to our argument, is that agent behavior relating to permeability and autonomy should remain quite conservative while states remain uncommitted. As discussed above, the Commission and the Court moved slowly and gradually on permeability issues. Though the Commission and Court steadily altered the rules governing complainants’ access, they consistently behaved in very conservative ways with respect to the number of cases they admitted and the rulings they adopted. Even while the rules were changing to allow plaintiffs greater direct access to the Court in the first 20 years, the Commission did not actually accept many applicants and passed even fewer onto the Court. In the end, the Court ruled on only 31 of the 8,352 applications declared admissible by the Commission from 1955 to 1979. Some of the cases rejected by the Commission would have undoubtedly brought it substantial attention, yet the Commission was quite deferential, refusing to accept petitions from former Nazis such as Rudolph Hess and disallowing any petition on any grounds from the German Communist Party, which had been dissolved by the German government (Weil 1963: 809–11).

The Court was even more cautious in demonstrating autonomy in its rulings. It its much-watched first case, Lawless v. Ireland, the Court decided that Ireland had indeed denied due process rights to an alleged member of the outlawed Irish Republican Army, but that this denial was lawful and consistent with the Convention because Ireland had first implemented a state of emergency (Robertson and Merrills 1993: 66–67, 184–89). From their earliest cases, both the Commission and the Court articulated a doctrine of a “margin of appreciation,” which recognized that governments have important interests in maintaining law and order and that governments are better positioned to judge those interests than international judicial bodies (Yourow 1996: 15–21).

To explore our and Moravcsik’s arguments in more detail, we examined the delegation decisions from several states that joined the Council of Europe prior to 1960: Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.Footnote 12 This process-tracing evidence of domestic decision-making underscores that most states were quite concerned about the Commission’s and Court’s permeability and autonomy and that states delayed delegation while they could observe the agents’ behavior. The nature and quality of the available evidence varies greatly by country. In the following analysis, we cite evidence from all these cases, but go into greater detail in the Swedish and British cases. As established democracies who delegated to the Court, Sweden and Britain constitute difficult cases for our theory emphasizing the costs of delegation and also for Moravcsik’s lock-in logic. If theories offer insights into difficult cases, scholars can have greater confidence in those theories.

The most systematic and strongest evidence of state caution is found in the fact that every state who delegated full authority to the Court in the 1950s also limited that delegation by using sunset clauses or, in the case of Ireland, domestic legislation. Table 3 lists all of the early adopters of individual petition and compulsory Court jurisdiction. For example, Denmark used a 2-year sunset clause with both optional clauses (Partsch 1956/1957: 107–09). Later states continued this practice throughout the 1960s and 1970s (Mikaelsen 1980: 21–23), thus demonstrating a strong interest in caution. While Ireland did not use a sunset clause, it adopted a different method of limiting its own delegation: The highest Irish court declared that the ECHR was not binding as domestic Irish law (Golsong 1958: 811–812). This evidence helps resolve the puzzle introduced above about why some stable democracies would delegate to the Court by showing that they delegated for only 2–5 years or hedged their delegation through domestic rules.

Even Germany, the country that had suffered the most under authoritarian rule and had a strong incentive to lock-in democracy, placed 3-year sunset clauses on its delegation. Such behavior seems fundamentally inconsistent with the whole notion of “lock-in.” The German Parliament empowered the Chancellor to commit Germany to both clauses when it ratified the ECHR in 1952–1953. Yet the Chancellor chose not to make either commitment, a point that the SPD opposition raised again in 1954. In so doing, they led with one of the few instances of the new democracy argument that we could locate: a country with Germany’s past and present had, the SPD opposition spokesman argued, every reason to “speedily pursue every route that promises to secure human rights and freedoms as soon and as securely as possible.”Footnote 13 The government, however, argued that there was “no rush”Footnote 14 and refused to commit Germany to the optional clauses for another 18 months. When in mid-June 1955, Belgium signed both clauses, the Germans followed but put a 3-year sunset clause on each.Footnote 15

In every case where they gave public reasons, government and parliamentary officials cited concerns about agent autonomy in order to justify limited or delayed delegation; seldom did they refer positively to the possibility that such measures will stabilize their own democracies. In fact, the only other reference to the possibility that the convention would provide lock-in is quite dismissive. In a parliamentary debate in the Netherlands in 1959, one Representative Schmal suggested that the idea that the convention could help protect Europe from future dictatorship is “propaganda” put out by the Council of Europe since such an effort would require “something much more” than a mere treaty (Council of Europe 1960: 550).

Rather, government and parliamentary officials seemed keenly interested in how the Commission (and, after 1958, the Court) were likely to behave. They consistently justified judgments based on those organizations’ previous behavior. The Dutch government pushed back on impassioned pleas to commit to the optional clauses by arguing that it would wait to watch the Commission’s behaviour before adopting them (Partsch 1956/1957). Though it initially feared the Commission would make political decisions, the Dutch government ultimately decided that “After the Commission had been established, it became clear that it had no political structure” and that abuse of its authority was non-existent (Council of Europe 1958–1959: 562). The Dutch and British governments both counted the number of petitions the Commission accepted (only 12 of 352 in 1958 when the Dutch examined the issue and 14 of 600 in 1960 when the British counted), expressed satisfaction in the low acceptance rates, and explicitly used this as a key justification for delegating authority (Council of Europe 1958–59: 564; 1960: 600). French officials cited a Swedish case as evidence that its own television monopoly would not be challenged by the Commission (Council of Europe 1973: 18).

As a stable democracy, Sweden seemed to confirm lock-in theory for several years by failing to delegate fully to the Court. But then in 1966, it accepted the Court’s compulsory jurisdiction. Government documents suggest that government officials long viewed the Court as the lock-in argument predicts: it provided no benefits but entailed potential sovereignty costs and was therefore unacceptable. Thus, it took only safe steps. In 1951 the government sent the convention to parliament for adoption because it wanted Sweden to join other governments in expressing its appreciation of human rights as part of the “common cultural heritage” of Europe in “solemn form.”Footnote 16 Parliament accepted the Convention and individual petition in 1953. But if the government saw some value in a formal treaty declaring common European values, it was unwilling to pay the sovereignty costs in the subsequent step of compulsory Court jurisdiction until “experience has shown that there is a practical need of the Court.”Footnote 17

In the early 1960s, Swedish debates over delegation to the Court focused explicitly on agent behavior as the new Court was establishing a track record. Under pressure from other states and some domestic politicians to accept the Court’s jurisdiction, Sweden (and Norway) officially declared in 1960 that they “needed to experience how the Court functioned practically by observation” before deciding whether to delegate.Footnote 18 In 1963, Sweden’s Foreign Minister argued for caution on further delegation to the Court by looking squarely at agent behavior.Footnote 19 For example, he noted the Court’s deference to Ireland’s security needs, but he also saw that the Court dismissed its second case only because Belgium changed its language policies. He concluded that the Court was unnecessary.Footnote 20 Three years later, however, the Swedish government did support approval for automatic Court jurisdiction, noting that “experience has so far shown that the Court’s operations are limited.”Footnote 21 The Court had handed down no judgments from 1963 to 1966, and the Swedish government noted that all pending cases dealt with “language issues in Belgium.” Having concluded that a 6-year observation of the Court’s behavior had revealed nothing troubling, the government concluded that Sweden should recognize the Court’s jurisdiction, and parliament agreed.

Britain actively opposed a strong Convention while it was being negotiated and insisted on the optional clauses for individual petition and Court jurisdiction (Moravcsik 2000; Stiles and Wells 2007). As the foreign minister flatly told Parliament in 1957, “The reason why we do not accept the idea of compulsory jurisdiction of a European court is because it would mean that British codes of common and statute law would be subject to review by an international court” (quoted in Janis et al. 1995: 26). Sentiment began to shift in the late 1950s and early 1960s, largely in response to the early decisions of the Commission and the Court (Simpson 2001: 1072–1090). After an exhaustive study of the British government’s declassified memos, Simpson (2001: 1086) summarized the British government’s reactions by observing that early Court and Commission decisions “gave rise to the conviction that initial fears had been unjustified; it could all have been much worse, and the system had not operated at all badly.” The British government essentially put the Commission and Court on trial from 1958 to 1964, paying particular attention to three cases: two complaints against Britain submitted to the Commission by Greece over British activities in Cyprus, and the Court’s first case in Ireland. The Greek complaint constituted a completely unexpected blindside that rang numerous alarm bells inside the government and led to calls for Britain to renounce the Convention (Simpson 2001: 12–13). The Commission, however, demonstrated its political astuteness by collecting information about possible abuses while simultaneously negotiating a political settlement between Greece and Britain that assured that the information would never be reported (Simpson 2001: 1048–1052).

As a result of this favorable outcome, the British government began to rethink its position. A foreign office memo suggested in May 1964 that Britain’s continued opposition to the optional clauses “looks unduly defensive, and in view of the Colonial Offices’ publicity proclaiming Britain as pre-eminently ‘the land of the free’ faintly ridiculous” (Simpson 2001: 1090). When a new Labour government came to power in October 1964, it initially decided to accept the optional clauses, largely because government officials believed the move would be mostly symbolic.Footnote 22 As Lord Chancellor Gardiner, Britain’s highest judicial official, put it in a letter to the Foreign Secretary (Lord Lester 1998: 239): “I do think that this [accepting the optional clauses] would cost us nothing and would show that a Labour Government is not anti-Europe as such and would hearten all those who want to see as many disputes as possible settled by some form of independent tribunal.” The foreign secretary, other foreign policy officials, and the home secretary all agreed.

Other officials, however, began raising questions about costs. Some worried about Burmah Oil Company using the Court to sue for arbitrary deprivation of property; others wished to restrict the right of Asians in East Africa who were citizens of the U.K. to enter the U.K.Footnote 23 As a result, the Home Secretary opposed mandatory jurisdiction of the Court and wanted to restrict individual petition to citizens living in the British Isles. He argued that Britain needed “utmost flexibility” to avoid “grave embarrassment” (Lord Lester 1998: 248–249). Once these issues were raised, the main debate revolved around the likely behavior of the Commission and Court, based on observations of their past behavior. The Lord Chancellor argued that the feared embarrassment was extremely unlikely because, in large part, “past experience shows how very few cases go to the Court.” The Foreign Office’s legal adviser chimed in that, “The approach of the Commission to this problem has in my experience been reasonable. I do not see why we should expect less of the Court, which is composed of even more eminent men than the Commission” (Lord Lester 1998: 249). The main arguments within the British government, then, revolved around the behavior of the Court. Under mounting political pressure, the Home Secretary acquiesced, but the government heeded his warnings. It notified the Commission that it would accept the right of individual petition for only three years so that Britain might terminate its acceptance if problems arose.

In sum, this evidence provides support for our arguments that states worried about the Commission’s and Court’s permeability and autonomy but were reassured by the conservative positions adopted by those institutions in the 1950s and 60s. With permeability and autonomy apparently in control, increasing numbers of states incrementally delegated more authority to the Commission and the Court. We find little evidence that any state pushed ahead with delegation for lock-in reasons. Even Germany, the most likely lock-in candidate and an early delegator, did not delegate nearly as quickly as some wished and then limited its delegation. Moravcsik’s (2000) argument about lock-in motives focused on the initial stage of setting up the ECHR. His empirical analysis emphasized the negotiations for the treaty establishing the Court and the Commission. Adopting a new treaty imposes few if any costs on states. It is not until ratification that state commitments actually occur and real costs are incurred. From this perspective, it is not surprising that the negotiations for the Commission and Court were driven more by prospective benefits than by analysis of later costs. Once states were asked to make individual commitments, however, they became more cautious.

With states concerned about costs and lock-in not providing much traction, what motivated delegation in the first place? Although we cannot answer this question fully, our examination of Sweden and Britain suggest they were motivated by the reputational benefits of being seen as human-rights-loving states. Hopes for a fundamentally different Europe based on democracy and respect for human rights were strongly present in postwar Europe, and states may have either believed in that vision or wanted to be seen as believing in it. Government officials in both Sweden and Britain referred to these ideals to justify delegation. Of course, not all states were equally motivated by that vision or benefit since some took much longer to delegate than others. Again, we cannot address this issue fully, but the pattern among late delegators is that they believed they needed to maintain some repressive mechanisms to either maintain control of colonies (France, Britain) or of domestic populations (Turkey, Greece). In Britain, government officials explicitly argued that delegation should be delayed until decolonization was well underway.

4 Conclusion

In November 2002, with the “poisoned” US-German relations at their nadir, the BMW Foundation sponsored a conference in Munich on “Transatlantic Challenges.” On the topic of the International Criminal Court, a representative of the Bush Administration urged the German audience to take seriously the Bush Administration’s principled reservations about the International Criminal Court. Calling the impasse a failure of diplomacy, he suggested a pragmatic approach: “Let the ICC develop a track record; let’s see that it depoliticizes judicial appointments and takes special care to appoint judges that will bring enough military expertise to the Court’s deliberations.”Footnote 24 This procedural approach is, as this article has shown, quite familiar. States often play a game of wait and see when it comes to delegations of sovereignty.

By way of summary, we have argued that increasing agent permeability is likely to lead to increasing agent autonomy because third parties can provide information and arguments that allow agents to maneuver beyond principal preferences or that persuade agents to conceptualize the world in new ways. Existing PA analyses, on the other hand, tend to focus on principal control mechanisms as the main determinants of agent autonomy. Some of the IC literature has pointed toward the importance of permeability, an emphasis that gains support in our case study. Principals realize that permeability may lead to autonomy and so are likely to delegate even more cautiously when there is uncertainty about the agent. Moreover, our argument suggests that delegation may not consist of a discrete decision but might be better characterized as an incremental process. Generally, the empirical evidence suggests that European states in the 1950s and 1960s were quite hesitant to delegate to a new and unknown Court and Commission of human rights despite interests in preserving democracy that had led them to negotiate those institutions in the first place. Moreover, the Court gained more autonomy only after it made itself more permeable to individual complainants. States did not change the rules to facilitate that greater permeability until after it was a fait accompli by the Court.

One important question concerns the generalizability of our arguments. It is important to be cautious about this; it seems unwise to assume either that ICs are fundamentally different from other IOs or that they are fundamentally similar (or, at a more basic level, that the ECHR is similar to or different from other ICs). Ultimately, the issue of generalizability is an empirical question that can only be answered by further research. That said, our three underlying dimensions of permeability—range of third-party access, decision-making level at which access is granted, and transparency—are certainly general enough to be applied to all kinds of IOs. It is possible that ICs systematically fall toward the higher permeability end of the scale, but we also note that substantial variation exists within ICs and that other IOs can also be highly permeable. It is also possible that it is easier (and more likely) for states to delay delegation to ICs than to other IOs whose functions include monitoring and information gathering rather than dispute resolution. Yet here again we are struck by the variation within ICs and IOs as much as the systematic variation between those categories. States drafting the ICC, for example, rejected almost all of the attempts to create a Court that would facilitate delegation in stages while states have been quite reluctant to delegate much authority to human rights monitoring committees.

In a more speculative vein and in the spirit of laying out possibilities for further research, we suggest a key condition under which agent permeability is more likely to matter: limited agent pools (Hawkins and Jacoby 2006). The size of agent pools is limited when there are relatively few well-known existing agents capable of taking on a given task and the cost of creating new agents is high. States also have more control over agents when pool size is large because they can more carefully select agents in the first place and because they can make more credible threats to switch to other agents if they are not pleased. States should prefer large pools of well-known agents over all other combinations, but especially over small pools of unknown agents. Unfortunately, it seems likely that principals in international and domestic politics often only have small pools from which to choose their agents.

Limited agent pools are likely to make principals more wary and circumspect than they would be if agent pools were large and mistakes could be easily corrected by switching agents. Faced with small agent pools and high costs of creating new agents, states should test the waters by delegating in stages or otherwise observing the behavior of agents before deciding to delegate. As our findings in this paper have shown, IO scholars may need more subtle codings of dependent variables associated with delegation, including things like provisional delegation, sunset clauses, or delegation in stages. At the very least, scholars should take care to consider all the costs of delegation, including permeability and its effects, and not just benefits in their analyses of IOs.

Notes

Though at very high levels of permeability, the agent may actually begin to actually lose autonomy as it becomes subject to very strong influence of third parties. This phenomenon is known as “capture” in a substantial literature. c.f. Laffont and Tirole (1991).

We thank an anonymous reviewer for making this point.

Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (hereafter, “European Convention”), American Journal of International Law, 1951, vol. 45 (2), Supplement: Official Documents, pp. 24–39, Articles 25–32.

European Convention, as amended by Protocol 11, at http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/EN/cadreprincipal.htm, accessed 8 Sept. 2003.