Abstract

Retrospective studies suggested a benefit of first-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment continuation after response evaluation in solid tumors (RECIST) progression in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. The aim of this multicenter observational retrospective study was to assess the frequency of this practice and its impact on overall survival (OS). The analysis included advanced EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients treated with first-line TKI who experienced RECIST progression between June 2010 and July 2012. Among the 123 patients included (67 ± 12.7 years, women: 69 %, non smokers: 68 %, PS 0–1: 87 %), 40.6 % continued TKI therapy after RECIST progression. There was no difference between the patients who did and did not continue TKI therapy with respect to progression-free survival (PFS1: 10.5 versus 9.5 months, p = 0.4). Overall survival (OS) showed a non-significant trend in favor of continuing TKI therapy (33.0 vs. 21.2 months, p = 0.054). Progressions were significantly less symptomatic in the TKI continuation group than in the discontinuation group (18 % vs. 37 %, p < 0.01). Univariate analysis showed a higher risk of death among patients with PS >1 (HR 4.33, 95 %CI: 2.21-8.47, p = 0.001), >1 one metastatic site (HR 1.96, 95 %CI: 1.06-3.61, p = 0.02), brain metastasis (HR 1.75, 95 %CI: 1.08-2.84, p = 0.02) at diagnosis, and a trend towards a higher risk of death in cases of TKI discontinuation after progression (HR 1.62, 95 %CI: 0.98-2.67, p = 0.056 ). In multivariate analysis only PS >1 (HR 6.27, 95 %CI: 2.97-13.25, p = 0.00001) and >1 metastatic site (HR 2.54, 95 %CI: 1.24-5.21, p = 0.02) at diagnosis remained significant. This study suggests that under certain circumstances, first-line TKI treatment continuation after RECIST progression is an acceptable option in EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients.

Clinical trial information: NCT02293733

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In Europe and North America, 10 % to 15 % of patients diagnosed with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have an activating mutation of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) gene. In France since 2010, NSCLC patients are screened for such mutations through a network of molecular biology laboratories [1]. Several phase III trials in patients with EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC [2–6] given first-line treatments have shown the superiority of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) over conventional chemotherapy in terms of progression-free survival (PFS). Three such drugs (gefitinib, erlotinib, afatinib) are now authorized in France for first-line treatment of NSCLC. However, almost all TKI-treated patients experience disease progression, as defined by the RECIST criteria [7]. These criteria, developed for patients undergoing chemotherapy, are not perfectly suited to targeted therapies that have different modes of action (blockade of signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation, angiogenesis, apoptosis, or metastasis) [8–10]. In 2010, Jackman et al. proposed specific criteria for disease progression during TKI therapy [11]. Moreover, several studies, although often small, retrospective, and conducted in a single center, suggest that TKI continuation after RECIST progression may sometimes postpone the need for second-line treatment and also improve survival [12–14]. The aim of this observational, retrospective, multicenter study was to determine the frequency of this practice in France, the characteristics of the patients concerned, and the possible impact on overall survival (0S).

2 Patients and Methods

The main objectives were to assess the frequency of continued EGFR TKI administration after RECIST progression in patients with advanced EGFR-mutated NSCLC and its impact on OS. A secondary objective was to describe the characteristics of disease progression in these patients.

This was a multicenter, observational, retrospective study including patients with advanced EGFR-mutated NSCLC treated with first-line EGFR TKI and experiencing RECIST progression between 1 January 2010 and 30 June 2012. The patients had to be over 18 years old and have a RECIST target lesion at inclusion. The following patient characteristics were recorded: socio-demographic characteristics, performance status (PS) at diagnosis, the type of EGFR mutation, disease extension, the mode of progression (site, symptoms), and treatment after disease progression. We compared patients in whom the TKI was continued as the primary treatment after the first RECIST progression (continuation group) with patients in whom the TKI was no longer the main treatment (discontinuation group). For each patient, we calculated progression-free survival (PFS) during first-line TKI treatment (PFS1), defined as the period between the start of TKI therapy and the first RECIST progression or death, as well as PFS between the first and second RECIST progression (PFS2), PFS between the second and third RECIST progression (PFS3), and overall survival (OS). RECIST progressions were diagnosed by the individual investigators, and a random sample of 30 files was reviewed centrally by a panel of experts convened by GFPC. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov under number NCT02293733

3 Statistical Analysis

The analysis was done on an intention-to-treat basis. Qualitative variables were described in terms of frequencies, percentages (with their 95 % confidence intervals calculated using an exact method), while quantitative variables were described in terms of the mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range. OS and PFS were analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier method. The TKI continuation and discontinuation groups were compared using Fisher's exact test or the Mann–Whitney U test. Univariate and multivariate analysis of OS and PFS1 used the Cox regression model and included the following covariates: age, gender, PS, histology, brain metastasis, EGFR mutations (deletions in exon 19, L858R vs. other mutations), TKI continuation or discontinuation after progression, and the number of metastatic sites. SAS statistical software v9.3 was used (INC Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Role of the sponsors: the sponsors had no role in the design or performance of the study, data analysis, or manuscript preparation. The results belong to GFPC. The data were analyzed by the GFPC statistician and interpreted by the authors.

The protocol was approved by an independent ethics committee in Saint Etienne on behalf of all participating centers, and the study complied with good clinical practices and the Helsinki Declaration.

4 Results

4.1 Patients Characteristics

The study included 123 patients treated in 29 centers. The patients (Table 1) were typical of the EGFR-mutated NSCLC population, with a median age of 67.7 ± 12.7 years and a predominance of women (69 %), non-smokers (68 %), performance status (PS) 0/1 (87 %), and adenocarcinomas (99 %). The mutations were located in exon 19, exon 21, or another exon in, respectively, 66 %, 30 %, and 4 % of cases. First-line treatment consisted of gefitinib and erlotinib in, respectively, 77 % and 23 % of cases. The vast majority (82 %) of patients were symptomatic at diagnosis (stage IV, 98 %), and only 33 % had one metastatic site (Table 2). The best responses to TKI therapy were complete, partial, and stable in, respectively, 5 %, 63 %, and 32 % of cases. Median PFS1 was 9.9 months.

4.2 First and Subsequent Progression: Therapeutic and Clinical Outcomes

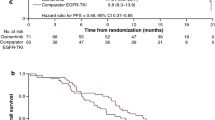

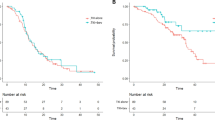

First progressions (Table 3) were characterized by an increase in the size of existing lesions (74 % of cases) and/or the appearance of new metastases (60 % of cases). After this first progression, 40.6 % of patients (n = 50) continued EGFR TKI as their primary treatment (continuation group), together with local radiotherapy (brain, bone, lung, cervical lymph node, liver) and/or vertebroplasty in 19 cases. The other patients (discontinuation group, n = 73) received either chemotherapy (n = 49), sometimes combined with a TKI (n = 10), or supportive care alone (n = 14) (Fig. 1). There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of clinical, mutational, or metastatic features at diagnosis (Table 2). However, although there was no difference in the mode of progression (main site/metastasis or new lesions), significantly fewer patients in the continuation group than in the discontinuation group were symptomatic at the time of progression (Table 3). Major new symptoms were pain, respiratory, neurological, and others (Table 3). There was no significant difference in PFS1 between the continuation and discontinuation groups (10.5 versus 9.5 months, respectively, p = 0.4) (Table 4). A second progression occurred in 79 patients (35 in the continuation group and 44 in the discontinuation group). There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of PFS2 (respectively 4.1 and 4.8 months, p = 0.55). Treatment after the second progression is summarized in Fig. 1. There was a highly significant difference in PFS3 (10.2 months vs. 3.6 months, p = 0.0096) between the continuation and discontinuation groups (Table 5). Finally, there was a non-significant trend towards longer overall survival (Fig. 2) in the continuation group than in the discontinuation group (33 months vs. 21.2 months, p = 0.054).

4.3 Re-Biopsy at Progression

This first and second progression gave rise to re-biopsy in 24 % and 17 % of cases, respectively (Table 5). In this study, the impact of re-biopsy on patient management has not been evaluated. However, we can assume that the histological (one case) or mutational changes (six cases of detection T790M mutation) have influenced the treatment.

4.4 Univariate and Multivariate Analysis

In univariate analysis, the risk of death was significantly higher among patients with PS >1 (HR 4.33, 95 % CI: 2.21 to 8.47, p = 0.0001), >1 metastatic site (HR 1.96, 95 % CI: 1.06 to 3.61, p = 0.02), or brain metastases (HR 1.75, 95 % CI: 1.08 to 2.84, p = 0.02) at diagnosis, and a non-significant trend towards a higher risk of death when TKI therapy was discontinued after PFS1 (HR 1.62, 95 % CI: 0.98 to 2.67, p = 0.056). In multivariate analysis, the only significant risk factors for death were PS >1 (HR 6.27, 95 % CI: 2.97 to 13.25, p = 0.0001) and >1 metastatic site (HR 2.54, 95 % CI: 1.24 to 5.21, p = 0.02) at diagnosis (Table 6).

5 Discussion

This multicenter study of Caucasian patients with EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC receiving first-line EGFR TKI therapy shows that in a real-world setting in France, 40.6 % of patients continued to receive the same first-line TKI as their main treatment after the first RECIST progression. Disease progression was significantly less symptomatic in this group of patients. This might underline a different biology of disease with less aggressive and symptomatic disease. There was no significant difference between the TKI continuation and discontinuation groups in term of PFS1 (10.5 versus 9.5 months) or PFS2 (4.1 versus 4.8 months), but there was a highly significantly difference in PFS3 (10.2 vs. 3.6 months, p = 0.0096) and a non-significant trend towards better OS (33.0 vs. 21.2 months, p = 0.054) when TKI therapy was continued. Several studies have clearly demonstrated the advantages of first-line EGFR TKI therapy over chemotherapy for advanced EGFR-mutated NSCLC [2–6]. Likewise, benefits of continued blockade of mutated gene pathways after tumor progression have been observed in several types of cancer [15–17]. Only preliminary studies are available for lung cancer, and most were small and conducted in a single center. In a retrospective analysis of 147 NSCLC patients treated with EGFR TKIs in an Italian center from 2004 to 2012, 10 % of patients who had single-lesion RECIST progression were treated with locoregional radiotherapy plus continued EGFR TKI therapy until further progression. Median PFS2 was 10.9 months (range 3–32 months) [18]. However, the population was heterogeneous, many patients having wildtype or unknown EGFR status. In a U.S. single-center study of 56 patients with advanced EGFR-mutated NSCLC, 88 % of patients continued TKI therapy after retrospectively diagnosed disease progression (increase in the target lesion in 97 % of cases, new lesion in 81 %, and both in 83 %). The median time between RECIST progression and TKI discontinuation was 10.1 months [14].

The impact of TKI continuation after RECIST progression on survival has rarely been studied. In a retrospective analysis of 335 Japanese patients with advanced NSCLC who responded to initial gefitinib therapy [19], 18.3 % of patients continued to receive gefitinib after RECIST progression. They experienced significantly better survival (HR for death: 0.726, 95 % CI: 0.538–0.980; p = 0.035) than the other patients, but the difference was not significant in multivariate analysis. More recently, a Japanese team retrospectively assessed a group of 64 patients selected among 186 patients with EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC [20]. Sixty percent of the 64 patients continued EGFR-TKI therapy after progressing. Median OS was significantly better than among patients who switched to chemotherapy (32.2 versus 23.0 months, p = 0.005, HR: 0.42, 95 % CI: 0.21-0.83), but this analysis excluded patients who, after disease progression, received a combination of chemotherapy and EGFR-TKI, those who resumed TKI therapy after a line of chemotherapy, and those who received only best supportive care after progression. Finally, preliminary results from a prospective, phase II trial (ASPIRATION) of EGFR TKI continuation after first RECIST progression show that TKI therapy was continued for a median of 3.7 months in the experimental group [21], a duration very similar to that found here. In our study, PFS3 improved significantly in the continuation EGFR TKI group. But patients in this group received more often chemotherapy and more often platin doublet chemotherapy with a high response rate compared to discontinuation group. This higher therapeutic pressure may explain the trend for better survival.

One strength of our study is its multicenter design, ensuring rapid recruitment of a representative patient sample of French national management practices in advanced EGFR-mutated NSCLC [1]. Our efficacy data for first-line TKI therapy are very similar to those of phase III trials in Caucasian populations, in terms of both PFS and OS. The modes of disease progression observed here are also compatible with published data [22]. Although the two groups had similar characteristics at diagnosis, those who continued TKI therapy after RECIST progression were significantly less symptomatic at the time of progression. The mode of disease progression markedly influences management choices. Yang et al [23] attempted to establish a typology of disease progression in EGFR TKI-treated advanced mutated NSCLC. One hundred and twenty consecutive clinical trial patients were used to establish a model based on clinical factors, and another 107 routinely treated patients were used as the validating set, using Bayes discriminant analysis. The cohort was classified into patients with dramatic progression, those with gradual progression, and those with local progression. PFS in the dramatic, gradual, and local progression groups was 9.3, 12.9, and 9.2 months, respectively (p = 0.007), and OS was 17.1, 39.4, and 23.1 months, respectively (p < 0.001). TKI continuation was superior to switching to chemotherapy in the gradual progression group in terms of OS (39.4 months vs. 17.8 months; p = 0.02). In patients with dramatic progression, the difference between TKI continuation and switching to chemotherapy was marginally in favor of chemotherapy (18.6 months vs. 23.9 months; p = 0.07), while median OS was similar between EGFR TKI continuation and chemotherapy in the local progression group (23.6 months vs. 23.7 months; p = 0.66) [23]. In our study, it is likely that the investigators tended to switch to chemotherapy more often for patients with clinical signs of rapid progression.

Several mechanisms of EGFR TKI resistance have been identified, including emergence of the T790M mutation, c-met amplification, and histological transition to small-cell carcinoma [24]. Re-biopsy is required to determine which mechanism is responsible for TKI resistance [25], but few patients in our study underwent re-biopsy after progression (24 % after first progression, 17 % after second progression). This study has several limitations. First, the definition of RECIST progression was left to the individual investigators. Central review of a random sample of 30 files showed good agreement. However, the decision to continue or discontinue TKI therapy was also left to the investigators and was not necessarily guided by the clinical features of progression. Our decision to include in the "discontinuation" group patients (n = 10) who received both chemotherapy and continued TKI therapy is debatable, but the introduction of chemotherapy was considered to represent a real treatment switch. Preliminary results of the IMPRESS study suggest little impact of continued EGFR TKI therapy plus chemotherapy in this situation [26]. Likewise, the inclusion of patients who received only best supportive care after progression may have influenced the median OS in the discontinuation group, but an analysis excluding these patients showed no significant difference in overall survival versus the TKI continuation group (22.6 months vs. 33 months, p = 0.19). Furthermore, the number of patients continuing EGFR TKI is limited. Results observed and their interpretations should be cautious.

6 Conclusion

This retrospective study suggests that in certain circumstances, continued EGFR TKI therapy after first RECIST progression may benefit some patients, particularly those whose progression is pauci-symptomatic, gradual, or accessible to local treatment.

References

Barlesi F, Blons-h, Beau-Faller M, et al. Biomarkers (BM) France: Results of routine EGFR, HER2, KRAS, BRAF, PI3KCA mutations detection and EML4-ALK gene fusion assessment on the first 10,000 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (pts). J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:(suppl; abstr 8000).

Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S et al (2009) Gefitinib or carboplatin–paclitaxel inpulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 361:947–957

Zhou C, Wu YL, Cheng G, Feng J, col (2011) Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment forpatients with Advanced EGFR mutation-positive non small cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CNTONG-0802):multicentre, open- label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 12:735–742

Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A et al (2012) Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as firstlinetreatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer(EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 13:239–246

Gao G, Ren S, Li A et al (2012) Epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy is effective as first-linetreatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR: A meta-analysis from six phase III randomized controlled trials. Int J Cancer 131(5):E822–E829

Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N et al (2013) Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol 31:3327–3334

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J et al (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45:228–247

Choi H, Charnsangavej C, Faria SC et al (2007) correlation of computed tomography and positron emission tomography in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumortreated at a single institution With Imatinib Mesylate: Proposal of New Computed Tomography Response Criteria. J Clin Oncol 25(13):1753–1759

Benjamin RS, Choi H, Macapinlac HA, v (2007) We Should Desist Using RECIST, at Least in GIST. J Clin Oncol 25:1760–1764

Lee HY, Lee KS, Ahn M-J (2011) New CT response criteria in non-small cell lung cancer: Proposal and application in EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Lung Cancer 73:63–69

Jackman D, Pao W, Riely GJ et al (2010) clinical definition of acquired resistance toepidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 28:357–360

Weickhardt AJ, Scheier B, Burke JM et al (2012) Local ablative therapy of oligoprogressive disease prolongs disease control by tyrosine kinase inhibitors in oncogene-addicted non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 7(12):1807–1814

Inomata M, Shukuya T, Takahashi T et al (2011) Continuous administration of EGFR-TKIs following radiotherapy after disease progression in bone lesions for non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res 31(12):4519–4523

Nishino M, Cardarella S, Dahlberg SE et al (2013) Radiographic assessment and therapeutic decisions at RECIST progression in EGFR-mutant NSCLC treated with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Lung Cancer 79:283–288

Blackwell KL, Burstein HJ, Storniolo AM et al (2010) Randomized study of lapatinib alone or in combination with trastuzumab in women with ErbB2-positive, trastuzumab-refractory metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 28:1124–1130

Grothey A, Sugrue MM, Purdie DM et al (2008) Bevacizumab beyond first progression is associated with prolonged overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from a large observational cohort study (BRiTE). J Clin Oncol 26:5326–5334

Extra JM, Antoine EC, Vincent-Salomon A et al (2010) Efficacy of trastuzumab in routine clinical practice and after progression for metastatic breast cancer patients: the observational Hermine study. Oncologist 15:799–809

Conforti F, Catania C, Toffalorio F et al (2013) EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors beyond focal progression obtain a prolonged disease control in patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer 81:440–444

Nishino K, Imamura F, Morita S et al (2013) A retrospective analysis of 335 Japanese lung cancer patients who responded to initial gefitinib treatment. Lung Cancer 82:299–304

Nishie K, Kawaguchi T, Tamiya A et al (2012) Epidermal Growth Factor ReceptorTyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Beyond Progressive Disease: A Retrospective Analysis for Japanese Patients with Activating EGFR Mutations. J Thorac Oncol 7:1722–1727

Park K, Ahn M, Yu C et al (2014) Aspiration: first-line erlotinib (e) until and beyond recist progression (pd) in asian patients (pts) with egfr mutation-positive(mut+) nsclc. Ann Oncol 25(suppl4):iv426–iv427. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu349.2

Kim HR, Lee JC, Kim YC, Kim KS et al (2014) Clinical characteristics of non-small cell lung cancer patients who experienced acquired resistance during gefitinib treatment. Lung Cancer 83(2):252–258

Yang JJ, Chen H-J, Yan H-H et al (2013) Clinical modes of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor failure and subsequent management in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 79(1):33–39

Cortot A, Janne PA (2014) Molecular mechanisms of resistance im epidermal growth factor receptor mutant lung adenocarcinomas. Eur Respir Rev 23:356–366

Chouaid C, Dujon C, Do P et al (2014) Feasibility and clinical impact of re-biopsy in advanced non small-cell lung cancer: A prospective multicenter study in a real-world setting (GFPC study 12–01). Lung Cancer 86:170–173

Mok T, Wu Y, Nakagawa K et al. Gefitinib/chemotherapy vs chemotherapy in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after progression on first-line gefitinib: The phase III, randomised IMPRESS study. Ann Oncol. 2014;25 (suppl 4). doi 10.1093/annonc/mud438.5

Acknowledgments

This trial was an academic trial conducted by Groupe Français de Pneumo Cancerologie (GFPC).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

ᅟ

Funding

This study received an unrestricted grant from F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Conflict of Interest

JBA has received personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Hoffman-Roche, Lilly, and Pfizer. CAV has received personal fees from Roche and Astra Zeneca. MP has received personal fees from Roche, Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb. CDPvH has received personal fees from Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim and Bristol Myers Squibb. SBO has received personal fees from Boehringer and Astra Zeneca. RC and GLG have received personal fees from Hoffman-Roche and Lilly. PF and AV have received personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Hoffman-Roche and Lilly. DA has received personal fees from Hoffman-Roche and Novartis. CC has received personal fees from Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffman-Roche, Sanofi Aventis, Lilly, Novartis, and Amgen. RG has received personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Hoffman-Roche and Astra Zeneca. The other authors (CF, AB, FV, NB, RL, BM) declared no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Auliac, J.B., Fournier, C., Audigier Valette, C. et al. Impact of Continuing First-Line EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Therapy Beyond RECIST Disease Progression in Patients with Advanced EGFR-Mutated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): Retrospective GFPC 04-13 Study. Targ Oncol 11, 167–174 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-015-0387-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-015-0387-4