Abstract

Dual-earner couples with adolescent children face increased challenges to manage work and family roles. This study aims to analyse the effect of two sources of support (organisational and supervisor support) on work-family conflict (WFC) and psychological detachment from work, according to a couple-dyadic model. More specifically, we propose a model in which WFC acts as a mediator for the relationship between organisational and supervisor support, and psychological detachment. A sample of 198 dual-earner couples with at least one adolescent child (aged 13–18 years) participated. We analysed actor, partner and gender effects using the Actor–partner interdependence mediation modeling and found that the association between supervisor support and WFC is stronger for women, while the association between organisational support and WFC manifests with the same intensity for men and women. In the case of men, it is organisational support (i.e., broad source of support) that is associated with psychological detachment through WFC, while in the case of women, it is supervisor support (i.e., specific source of support) that is associated with psychological detachment, also through WFC. No partner effects were found. Our results highlight the need for organisations to implement work-family balance measures that take dyadic interactions and gender differences into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The increase in women’s participation in the labor market contributed to the growing number of dual-earner couples (Wall, 2005). These couples face particular challenges when managing work and family domains, which can be linked to a more conservative view of gender roles in most societies (Lucas-Thompson et al., 2010; Matias, 2019; Matias et al., 2022). Work-family conflict (WFC), that occurs when multiple roles played by the individual compete with each other in terms of time or energy, is one of the most studied constructs capturing these difficulties in managing different life roles (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). These may interfere with the ability to recover after work (Sonnentag et al., 2017), including the ability to distance from work during non-work time (i.e., to psychologically detach), which is essential for the recovery of energy and for workers’ well-being (Bakker, 2011; Fritz et al., 2010; Sonnentag et al., 2012). In addition, different sources of social support within the work context (e.g., organisational or supervisor support) are key to prevent WFC (Cohen & Wills, 1985) and may be an important asset to help workers to psychologically detach from work-related activities during non-work time. Although supervisor and organisational support may have a positive effect on an individual recovery experience, the crossover effects on couples with children are still not clear. With few exceptions (e.g., Lawson et al., 2014; Matias & Recharte, 2020), the major bulk of research has focused on the work-family interface of families with younger children. However, families with adolescents face the need for an interactional reorganization and a readjustment of the relationship between parent and child (Carter & McGoldrick, 2005). These specificities call for the need to find a new equilibrium and can also pose heightened challenges for parents. Nonetheless, no studies have applied a dyadic approach with these families when analysing the role played by the perception of a supportive supervisor and organisational support in workers’ WFC and their subsequent ability to psychologically detach from work.

Psychological Detachment from Work

The importance of recovering from work stressors is consensual. It has an influence in psychological well-being and health, work engagement and exhaustion (Bakker, 2011; Fritz et al., 2010; Sonnentag et al., 2012, 2017). Psychological detachment (i.e., the experience in which the individual disconnects from work-related thoughts during off-job time), is one of the most studied recovery dimensions and can be of major relevance to allow the individual to effectively engage with the family role (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007). Psychological detachment and WFC are negatively related (Demsky et al., 2014) and psychological detachment has been found to moderate the negative effect that WFC poses on the worker’s well-being (Moreno-Jiménez et al., 2009). Considering a longitudinal approach, WFC and psychological detachment were found to be both linked to the workers’ extended availability to work during off-job time, leading to a continuous depletion of resources (Dettmers, 2017).

While most research on recovery and psychological detachment has focused on the role of work stressors in reducing the individual’s ability to detach from work, there is also evidence that job resources (such as organisational support) may facilitate recovery (see Sonnentag et al., 2017 review). Indeed, if the supervisor and/or the organisational context are supportive of individuals' investments in other roles and work-family balance, this may promote higher psychological detachment from work. As Sonnentag et al. (2017) claim, when supervisors expect their subordinates to work while being at home, employees are more likely to worry about their work during non-work time. However, the association between organisational support and psychological detachment via WFC has not been studied in a dyadic approach. We expect that more organisational support (i.e., more resources), will lead to fewer difficulties in conciliation, less WFC and, in turn, greater psychological detachment from work.

Organisational Support, Supervisor Support and WFC

According to the Social Support theory, perceptions of support are strongly related to WFC (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Sources of support may be at the organisational-level (e.g., supportive organisational perceptions) as they may also derive from individuals in the work context (e.g., supervisors) (French et al., 2018).

The concept of organisational support for work-family balance is based on perceptions that the employer: (a) cares about the employee's ability to effectively perform family and work-related roles and (b) promotes a supportive social environment by providing resources towards work-family balance (Kossek et al., 2011b). Since policies alone are insufficient to promote a better balance, Allen (2001) introduced the concept of family-supportive organization perception, that refers to the individual's perceptions of the organization as being sensitive and supportive of the employee's efforts to balance work and family commitments and responsibilities. This perception is associated with greater job satisfaction, sense of commitment to the organization, and reduced WFC (O'Driscoll et al., 2003). When workers have support aimed at managing family and work-related issues, they can transfer this positive experience to the family role (spillover), which also reduces WFC (Frone et al., 1992). Organisational support not only buffers the stress of work demands, but also helps conserve resources in both the family and work domains (Allen, 2001), as it provides support to manage the demands of both (Hammer et al., 2009).

Importantly, and although family-friendly measures provide employees with more options to manage work and family roles, if supervisors do not value them or do not support a family-friendly environment at the workplace, the efficacy of these measures is threatened (Allen, 2001; Allen & Finkelstein, 2014). Employees who perceive their organization and their supervisors as family-supportive feel more comfortable utilizing the available benefits, while employees who perceive their work environment as not family-supportive may fear criticism and a negative impact on their career if they use such benefits (Allen, 2001; Thompson et al., 1999). In this regard, Allen (2001) provided evidence that emotional, practical, and social support from supervisors reduces WFC, alongside working in an environment perceived as more family-supportive; both factors add to the decrease in work to family conflict (Allen, 2001).

Support received at the work context may have a differential impact on WFC depending on whether it is broader (i.e., organisational) or more specific (i.e., supervisor support). Given the inconsistency of findings from research comparing both sources of support (French et al., 2018), the present study aims at introducing a dyadic lens that may contribute to this analysis.

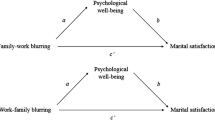

Based on this theoretical framework, we propose that supervisor support and organisational and support are expected to be directly and positively associated with psychological detachment from work (H1a; H1b). The relationship between supervisor’s support and organisational support and psychological detachment is also expected to be mediated by the own’s WFC (H2a; H2b). This mediation will be supported by the direct and negative effect of supervisor’s support and organisational support on WFC (H3a; H3b) and by the direct and negative effect of WFC on psychological detachment (H4).

Crossover Processes and Gender

In the case of dual-earner couples, the issue of work-family interface has an additional layer that is important to consider. Besides the spillover effect (i.e., the intra-individual transference of experiences, resources and strains from one domain to the other), it is also important to analyse how each partner's experience may influence the other partner's work-family conciliation, in a logic of reciprocal influence—crossover processes (Bakker & Demerouti, 2013). In fact, the negative emotions and stress experienced by a partner may be caused not only by their own work and family demands, but also by the transmission of their partner's experience (Bakker et al., 2008; Demerouti et al., 2005; ten Bremelhuis et al., 2010).

In dual-earner couples, as these individuals meet their significant other after work, there is a unique context for research on recovery processes. In these couples, there is a greater need for coordination so that both can recover physically and psychologically after work (Saxbe et al., 2011). For example, the fact that one of the members of the couple experiences more demands at work may limit the time that they can spend together which, in turn, may cause negative feelings such as pressure, stress and emotional exhaustion (Demerouti et al., 2005). Indeed, the spouse’s ability of psychologically detaching from work impacts affective well-being outcomes of the other member of the couple (Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2018). However, this effect may depend on whether couples have children (Hahn et al., 2014). Different sources of support, such as organisational or suppervisor’s have shown to be key at promoting employees’ recovery experiences (Sonnentag et al., 2022), so it is now relevant to further investigate how these sources of support may have a differential effect within a couple.

Thus, we expect that the support obtained by one of the members of the dyad reduces the partner's WFC (H5a; H5b) and promotes psychological detachment (H6a; H6b). High levels of WFC of one of the dyad members are also expected to reduce the partner's psychological detachment (H7).

Studies seeking to relate crossover effects and gender differences have not been conclusive. Nevertheless, according to the gender role theory, the family domain, compared to the professional domain, is of high importance for women (ten Brummelhuis et al., 2010). On the other hand, men are perceived as more responsible for the professional domain, attributing a higher value to it themselves (ten Brummelhuis et al., 2010). However, as research consistently states, women combine their professional activities with a greater responsibility for family tasks (Matias, 2019; Perista et al., 2016). This accumulation of roles leads to greater conflict, stress and tension (Hill, 2005; Marshall & Barnett, 1993), which may determine that men and women use different strategies to cope with the demands of conciliation (Matias & Fontaine, 2015). In fact, in a dyadic study with dual-earner couples with preschool aged children, workplace family support impacted women’s and men’s levels of WFC, while men’s workplace family support only impacted men’s levels of WFC (Matias et al., 2017). Despite the lack of research on crossover effects of workplace resources, we propose that, based on the premise that women have a more active participation in the family domain, involving domestic tasks and childcare, both organisational and supervisor support may have an effect not only on their own indicators of WFC and psychological detachment, but also on their partners'.

We therefore expect that women's attainment of supervisor’s support or organisational support shows a stronger association with their own and their partners’ levels of WFC (H8a; H8b) and psychological detachment (H9a; H9b; H10) than men’s attainment of support.

Method

Design and Data Collection

This study obtained approval by the Ethics Committee of the authors’ institution (Approval 5–9/2015) and received a favorable opinion from the National Data Protection Committee. A set of selection criteria were defined for the sample, such as: both members of the couple should live together, be engaged in a paid professional activity and have at least one child aged between 13 and 18 years old.

The recruitment procedure included contacting educational institutions, study support centers and sports clubs directed at youngsters. After permission was obtained from the directors of the respective institutions, the approach to participants was carried out in two main ways: through the parents themselves or through the adolescents. In the first contact with potential participants, the objectives and modalities of the study participation, alongside the confidentiality and anonymity procedures, were clarified. In cases where the contact was direct with the adolescents, the information on the study was first provided in an informative leaflet containing the contacts of the research team to clarify any doubts. Only after this leaflet was returned together with the parents' consent form, the envelope containing the questionnaires was provided to each participating family. Parents were instructed to fill in their questionnaires separately. All questionnaires were returned in a sealed envelope directly to the researcher or, in some cases, to the teacher/coach who subsequently handed them over to the research team. Another route of recruitment occurred by convenience, through a snowball procedure. The response rate to the questionnaire was 80.6%.

The initial pool of participants corresponded to 252 families. However, families in which only one of the members of the couple participated (n = 14), in which one of the members was unemployed (n = 13) and those in which one of the participants did not answer all the items of one of the measurement scales (n = 29) were disregarded. The final sample was then composed of 196 dual-earner couples aged between 31 and 62 years (M = 45.71, SD = 5.09). The couples in the sample maintain a marital relationship over a minimum period of 120 months (approximately 10 years) and a maximum of 441 months (approximately 37 years) (M = 251.34 (approximately 21 years), SD = 55.90 (5 years); 14.2% of the sample have one child, 66.1% have two children, 19.6% have three or more children; with an average age of approximately 15 years (M = 14.97; SD = 3.35).

Most of the parents in the sample had only completed basic education (Men: 57.5%; Women: 40.4%) and there were more women than men with higher education (Men: 19.2%; Women: 29.0%). In terms of professional situation, one man simultaneously studies (0.5%) and works, and another is benefiting from sick leave (0.5%). In terms of working time, both men and women were mostly working full-time (Men: 93.9%; Women: 90.0%) and on a fixed schedule (Men: 79.7%; Women: 72.4%). Regarding the employment regime, most of the sample had a permanent employment contract (Men = 65.6%; Women = 70.1%), in a small company (up to 50 employees) (Men = 53.7%; Women = 44.9%).

Measures

Sociodemographic Characterization

Participants indicated their age, education, marital status, duration of the marital relationship, number and ages of children, professional situation of the participants, number of hours of work per week, employment regime, working hours and the size of the company where they work.

Support from the Supervisor

Support from the supervisor was assessed with a brief instrument composed of three items designed for this study based on the literature (1—My supervisor/chief shows a lot of understanding towards my situation (e.g., on work distribution, holiday scheduling, etc.); 2 – My supervisor/chief cares about my well-being; 3—My superior/chief pays little attention to my family situation), answered on a 5-point Likert scale from (1) Strongly Disagree to (5) Strongly Agree. The internal consistency was close to acceptable (α = 0.65).

Organisational Support

Organisational support was assessed with the Family Supportive Organization Perceptions scale (Allen, 2001; translated into portuguese by Chambel & Santos, 2009). The scale is composed of 14 items, rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) Strongly Disagree to (5) Strongly Agree (e.g., Expressing involvement and interest in nonwork matters is viewed as healthy). The internal consistency was acceptable (α = 0.68).

Work-family Conflict

Work-family conflict was assessed with the Work Family Conflict Scale (Carlson et al., 2000; Portuguese adaptation by Vieira et al., 2014). In the present study, we only considered the work to family direction, composed of 7 items (e.g., "My work means that I cannot be with my family as much as I would like"), ranging on a 5-point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5). The internal consistency was high (α = 0.88).

Psychological Detachment from Work

Psychological detachment was assessed with the Recovery Experience Questionnaire (REQ; Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007; Portuguese adaptation by Lobo & Pinheiro, 2012). This dimension is composed of 4 items (e.g., "After the end of a working day, I forget about work") answered on a 5-point Likert scale, from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5). The internal consistency was high (α = 0.83).

Data Analysis

Preliminary data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences), version 21. After confirming the randomness of missing data using Little's test, data imputation was performed using the Expectation Maximization procedure. As in this study we considered the dyad as the unit of analysis of the different constructs addressed, Pearson's bivariate correlations were used to address interrelations between the target variables of the study; across partners, a T-Test for paired samples was used to compare male and female partner’s means.

The AMOS (Analysis of Moment Structures), version 24, was used to test the hypotheses. The study hypotheses assume an Actor-Partner Interdependence Mediation Model (APIMeM) which allows analysing mediation in dyads by estimating both actor and partner effects. This model intends to test the mediating role of WFC for both members of the couple, in the association between the two sources of support (supervisor support and organisational support) and psychological detachment. Consequently, in the present study, two different models were tested, as there are two different predictors, one model for the predictive effect of supervisor support and another one for organisational support. The proposed models were tested using the Maximum Likelihood Method (Arbuckle, 2010). The use of the structural equation method to test the APIMeM model allows considering the non-independence of data from the two members of a couple, analysing actor and partner effects in an integrated way, and also estimating both direct and indirect effects to verify the mediation hypotheses.

In the first stage, the adjustment of the two proposed models was tested using the following indicators: comparative fit index (CFI), χ2/gl ratio and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). According to Schweizer (2010), when the χ2/gl ratio is lower than 2, there is a good fit of the model; when it is lower than 3, the model fit is acceptable. As for CFI values, if framed between 0.90 and 0.95, we should consider the adjustment acceptable, and if between 0.95 and 1.00, good. Finally, for RMSEA values higher than 0.08, the model fit will be considered mediocre, between 0.05 and 0.08, good and, below 0.05, very good. Due to the sample size (n = 196) and the number of parameters to be estimated, all variables were considered as observed variables.

In a second step, and in order to test the hypotheses regarding gender-differentiated relations, gender invariance between trajectories was tested by comparing nested models, in which the equivalent trajectories were constrained to be equal (i.e., the trajectory between the man's supervisor support and the man's WFC (actor effect) and the trajectory between the women's supervisor support and the women's WFC (actor effect) were constrained to be equal, and the same was done for the remaining actor trajectories). Similarly for partner effects, the path from the man's supervisor support for the women's WFC and the path from the women's supervisor support for the man's WFC were constrained to equality and so on for the remaining trajectories. Models with and without this constriction were compared using chi-square difference test (a non-significant difference test is evidence of an equivalence between the models, so equivalences in the trajectories can be assumed (Gonzalez & Griffin, 2001).

The trajectories that were found to be equivalent between men and women were constructed to equality before testing the significance of the indirect effects in the third and final step. These effects were tested using the bootstrapping resampling procedure. This procedure is recommended over Sobel's (1982) test or other conventional approaches because of its statistical power (MacKinnon et al., 2004). Thus, the sample was repeated 2000 times (with replacement) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. An indirect effect is considered significant if the value of zero is not contained in the confidence interval.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations and correlations between all variables of the model. There were significant differences only on organisational support, which is higher among women than men. WFC scores were around average and psychological detachment had low scores, indicating that couples were not managing to psychologically distance themselves from work.

Supervisor support and organisational support were negatively associated with both couple members' WFC. Regarding actor effects, men’s WFC was negatively associated with their own psychological detachment. In the case of women, there were no significant associations between WFC and their psychological detachment. There were no significant associations between supervisor support and organisational support and psychological detachment for both members of the couple.

As for the partner effects, no significant associations were found between the supervisor support and organisational support and WFC, with the exception of women’s perception of supervisor support, which was negatively associated with her partner’s psychological detachment. There were also no significant associations between the WFC of one spouse and the psychological detachment of the other, as well as between organisational support, in its two dimensions, and psychological detachment.

Direct and Indirect Effects of Supervisor Support on WFC and Psychological Detachment

The model presented in Fig. 1 concerning supervisor support with all direct and indirect trajectories between the study variables was fitted to the data. In order to simplify the model, we tested for gender invariance in the equivalent trajectories of actor and partner effects by comparing models with free estimates with models with constraints on actor effects and partner effects (as explained in the data analysis procedure section).

For the model concerning supervisor support, we found that the model with constrictions on partner trajectories did not differ significantly from the free model (Δ χ2 (3) = 2.411, p = 0.492), but the model with constrictions on actor trajectories differed significantly from the free model (Δ χ2 (3) = 8.721, p = 0.033). An analysis of which trajectories differed indicated that the actor trajectory between men's supervisor support and the men's WFC and the actor trajectory between women's supervisor support and the women's WFC differed from each other (Δ χ2 (1) = 4.344, p = 0.037). Thus, a final model with all remaining actor and partner trajectories constrained to equality was tested, showing a good fit (χ2(5) = 6.537; p = 0.257; χ2/df = 1.307; CFI = 0.979; RMSEA = 0.040). The model explains about 2.8% of the variance in men’s WFC indicators, 11.5% of the variance in women’s WFC, 2.2% in men’s psychological detachment, and 2.7% in women’s psychological detachment.

A negative association was found between supervisor support and WFC, and this association was higher for women (β = -0.336, p < 0.001; men—β = -0.160, p = 0.018). There was also a negative association between WFC and psychological detachment (β = -0.132, p = 0.015) for both men and women. None of the partner effects were significant. The remaining trajectories coefficients can be found on Table 2.

The analysis of indirect effects between supervisor support and psychological detachment, obtained using the bootstrapping resampling procedure, revealed a significant indirect effect between supervisor support and psychological detachment only for women (β = 0.039; 95% CI = 0.002 to 0.089; p = 0.036).

Direct and Indirect Effects of Organisational Support on WFC and Psychological Detachment

The model presented in Fig. 2 concerning organisational support with all the direct and indirect trajectories between the variables of the study, was adjusted to the data. Again, to simplify the model, gender invariance in the equivalent trajectories of actor and partner effects was tested. The model with constrictions on partner trajectories did not differ significantly from the free model (Δ χ2 (3) = 5.675, p = 0.129), but the model with constrictions on actor trajectories differed significantly from the free model (Δ χ2 (3) = 9.720, p = 0.021). Thus, the actor trajectory between WFC and men’s psychological detachment and the actor trajectory between WFC and women’s psychological detachment differed from each other (Δ χ2 (1) = 4.957, p = 0.026). The same was true for the actor trajectory between organisational support and men’s psychological detachment and the trajectory between organisational support and women’s psychological detachment, which also differ from each other (Δ χ2 (1) = 5.630, p = 0.018). A final model with the partner trajectories and the actor trajectory from organisational support and WFC constricted to equality and all the remaining modelled as free was fitted, showing a good fit (χ2(4) = 6.869; p = 0.143; χ 2/df = 1.717; CFI = 0.967; RMSEA = 0.061). This model explained about 7.5% of the variance in the men's WFC, 9.2% of the variance in the women's WFC, 3.6% in the men's psychological detachment, and 2.0% of the women's psychological detachment.

We found a negative association between organisational support and WFC of the same intensity between men and women (β = -0.296, p < 0.001). A negative association was found between WFC and psychological detachment only in the case of men (β = -0.194, p = 0.007). None of the partner effects were significant. See Table 2 for details on coefficients.

Indirect effects analysis between organisational support and psychological detachment, using the bootstrapping resampling procedure, revealed this effect was significant for men (β = 0.049; 95% CI = 0.009 to 0.099; p = 0.015).

Discussion

This study analysed the mediating role of WFC in the relationship between two sources of support – organisational support and supervisor support—and psychological detachment from work in a sample of dual-earner couples with at least one adolescent child. We explored the effects of actor, partner and gender, adopting a dyadic perspective on the effects of support in managing work and family roles. Our results showed that there are differences in psychological detachment and WFC between men and women depending on the source of support. Specifically, the association between supervisor support and WFC is stronger for women, while the association between organisational support and WFC manifests with the same intensity for men and women. In the case of men, it is organisational support that is associated with psychological detachment through WFC, while in the case of women, it is the supervisor’s support that is associated with psychological detachment, also through WFC. Thus, we may conclude that there is a gender difference underlying the link between the source of support and WFC. We also highlight the robustness of the actor effects compared to the partner effects, which were not significant in the models tested in this study, allowing us to conclude that the way WFC and psychological detachment are experienced is more affected by the idiosyncrasies of each member of the couple than by the interactions that may occur through crossover within the dyad.

The hypotheses advocating for direct effects between both sources of support and psychological detachment were not confirmed (i.e., nor organisational support, neither supervisor support were directly associated with psychological detachment (H1a; H1b). However, there was evidence of indirect effects. The confirmed indirect effects of organisational support on psychological detachment via WFC (H2a; H2b) suggest that the main function of organisational and supervisor support is indeed to help individuals achieve a better balance (i.e., less WFC). Thus, these may point that psychological detachment from work is related not to the source of support the individual receives, but to the effects of this support on work-family conciliation. As this support may be related to the degree to which individuals perceive that supervisors care about their well-being at work (Kossek et al., 2011b), the major influence occurs if this support facilitates resources to meet the demands of a given role (work or family). It should be noted, however, that the indirect effect does not occur for men and women in an identical way. In the case of men, it is the organisational support, which is associated with psychological detachment from work, through WFC; whereas for women, it is the supervisor support, which is associated with psychological detachment, also through WFC.

Together, these gender differential results lead us to conclude that closer support, through the figure of the supervisor, is more effective in reducing WFC and promoting psychological detachment from work in the case of women. Previous studies have already highlighted the relevance of close support for conciliation, as well as the fact that women tend to use more informal support, based on negotiation with the supervisor, to promote work-family conciliation (Guerreiro & Abrantes, 2007; Santos, 2010). Following the Social Support theory (Cohen & Wills, 1985), one may assume that broad sources of support (i.e., organisational) are more effective for men, while specific sources of support (i.e., supervisor support) have a stronger effect on women.

The finding that the effect of having organisational support is linked to increased detachment from work (via WFC) for men may derive from differential availability of work-family measures. Typically, men are less likely to be the target of measures to support conciliation and less likely to receive empathy and understanding from their superiors in this domain (Andrade, 2013); on the contrary, men are still pressured not to use family-friendly benefits as they may face stigmatization (Murgia & Poggio, 2009). Thus, men benefit the most when this type of support is more widespread, and the organization climate is perceived as supportive of work-family conciliation.

In addition, we also found a direct and negative association between supervisor support and WFC (H3a), which was higher in the case of women (H8a); and an equivalent association for men and women between organisational support and WFC (H3b; H8b). These results align with past research and indicate that organisational support for work-family conciliation, that is, perceptions that the employer cares about the employee's ability to effectively perform family and work-related roles, reduces WFC for both genders (Kossek et al., 2011a, 2011b). Moreover, a more supportive supervisor also lowers the conflict in balancing work-family roles (Hammer et al., 2009; Thomas & Ganster, 1995). What is specific in our study, and aligns with the indirect effect discussed above, is the fact that this more intense association between the supervisor support and the WFC for women reinforces the role of supervisor support for them.

Other results of this study confirmed the hypothesis concerning the direct and negative effects of WFC on psychological detachment (H4). This result indicates that the lower the WFC, the greater the distance of thoughts and concerns from the work domain. According to Jansen et al. (2003), WFC is associated with higher levels of fatigue and, consequently, a greater need for recovery. In fact, WFC is negatively associated with psychological detachment (Demsky et al., 2014) and, consequently, with recovery (Moreno-Jiménez et al., 2009).

The hypotheses regarding partner effects were not confirmed (H5a, H5b, H6a, H6b, H7). Nevertheless, it should be noted that the fact that these effects were estimated and considered in the models reinforces the results obtained by revealing a greater robustness of the actor effects. The process that we sought to study—how organisational support is associated with WFC and psychological detachment—seems to be more marked by the individual experience of organisational support than by dyadic interactions. Another explanation for the absence of partner effects may stem from the developmental stage of the families studied. The sample is composed of couples with adolescent children, whose parental challenges are quite different from the challenges faced by couples with younger children, namely as their children are more autonomous and do not need constant care and supervision. As the child's age increases, WFC tends to decrease, since the child becomes less dependent and couple articulation may be less required (ten Brummelhuis et al., 2009). In fact, most research on the issue of conciliation focuses on families with pre-school or school aged children, where parental strategies may be more articulated, and partner effects between the resources received by one element of the dyad and the spouse are potentially more evident.

Limitations

Some limitations should be considered when analysing the results of this study. First, regarding the sample, although this is a relevant and understudied sample on work-family studies, it is not representative, which limits the generalization of results. Secondly, although the empirical model tested underlies a theoretical model based on previous literature, causal relationships cannot be established with accuracy given the cross-sectional nature of the data collected. Future studies are encouraged to test these models using longitudinal data and assuming reciprocal interferences between psychological detachment and WFC. Thirdly, as far as recovery experiences are concerned, other dimensions besides psychological detachment (control, relaxation and mastery experiences) were not considered. In order to enhance the contribution to the body of knowledge on recovery experiences, future studies should include this construct’s multidimensionality.

Our study clearly identified a differential pattern on the effects of different sources of support for men and women, with implications for WFC and psychological detachment. Future studies could build on these findings and address interrelations among these types of support. For instance, analyse if the effects of supervisor support on reducing WFC and increasing psychological detachment are magnified when the culture is also seen as supportive; or analyse if supervisor support does indeed buffer an organisational culture that is less supportive.

Implications

Despite its limitations, this study makes great contributions both theoretically and practically. It adds an innovative approach to the existing literature by articulating concepts such as organisational support, supervisor support, WFC and psychological detachment through a dyadic lens. For a better understanding of possible associations, the data collected was tested through a refined methodology, where besides actor and partner effects, indirect mediation effects and gender effects were considered.

Thus, this study raises awareness for organisations to provide resources to support conciliation that go beyond policies imposed by law. Additionally, as research indicates, the availability of measures is not enough, and it is necessary that the supervisor and the organisational culture support these practices by not judging the employees who use them, neither their commitment to the organization. Often, family support policies, such as the possibility of reduced working hours or greater flexibility, are perceived as penalizing for professional progress and stability, thus inhibiting employees from using them (Andrade, 2015). Particularly, our finding that more informal support is the most effective to promote women's psychological detachment from work (and consequently well-being) by reducing their own levels of WFC may point out that women are in a position of greater vulnerability in their work context, precisely because they use a resource which relies on the quality of the worker-supervisor relationship, which can be quite volatile. The social and organisational issues that arise should be given attention to, since they may be reflected in negative effects for employee’s well-being.

Finally, we believe this study promotes a greater understanding about the relationship between organisational support, supervisor support, WFC and psychological detachment from work, as well as about the specificities of dyadic interactions and gender issues. In line with what has been suggested by Sonnentag and colleagues (2022), supervisor and organisational norms may embody a culture of segmenting or integrating work and home life, thus leading to different impacts for employees’ recovery experiences. The present study adds that these norms are not only important for employees to be able to psychologically detach from work, but that this effect is different based on gender. We expect that these results raise awareness to organisations and supervisors regarding the idiosyncrasies of their employees, encouraging not only the adaptation of available support measures, but also the improvement and fostering of resources that may reduce WFC and increase employees’ well-being. Supervisors should be supportive of their employees’ recovery (e.g., by not interrupting them during non-work time) and organisations should provide the necessary and most effective resources (i.e., ones who are designed to specific employee’s needs) that enable them to engage with their family role.

References

Allen, T. D. (2001). Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58(3), 414–435. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1774

Allen, T. D., & Finkelstein, L. M. (2014). Work–family conflict among members of full-time dual-earner couples: An examination of family life stage, gender, and age. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(3), 376–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036941

Andrade, C. (2013). Relações trabalho-família e género: Caminhos para a conciliação [Work-family relations and gender: Ways for conciliation]. Editora Coisas de Ler.

Andrade, C. (2015). Trabalho e vida pessoal: Exigências, recursos formas de conciliação [Work and personal life: Demands, resources and ways of conciliation]. Dedica: Revista de Educação e Humanidades, 8, 117–130. https://doi.org/10.30827/dreh.v0i8.6913

Arbuckle, J. L. (2010). IBM SPSS Amos 19 user’s guide. Amos Development Corporation.

Bakker, A. B. (2011). An evidence-based model of work engagement. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(4), 265–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411414534

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Dollard, M. F. (2008). How job demands affect partners’ experience of exhaustion: Integrating work-family conflict and crossover theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(4), 901–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.4.901

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2013). The spillover-crossover model. In J. G. Grzywacz, & E. Demerouti (Eds.), New frontiers in work and family research (pp. 54–70). (Current Issues in Work and OrganisationalPsychology). Psychology Press.

Carlson, D., Williams, L., & Kacmar, K. (2000). Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(2), 249–276. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1999.1713

Carter, B., & McGoldrick, M. (Eds.). (2005). The expanded family life cycle: Individual, family and social perspectives (3rd ed.). Allyn & Bacon Classics.

Chambel, M. J., & Santos, M. V. (2009). Work-family facilitation: Mediating the relationship between practices of conciliation and job satisfaction. Estudos De Psicologia, 26(3), 275–286. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-166X2009000300001

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2005). Spillover and crossover of exhaustion and life satisfaction among dual-earner parents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 266–289. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.07.001

Demsky, C. A., Ellis, A. M., & Fritz, C. (2014). Shrugging it off: Does psychological detachment from work mediate the relationship between workplace aggression and work-family conflict? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(2), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035448

Dettmers, J. (2017). How extended work availability affects well-being: The mediating roles of psychological detachment and work-family-conflict. Work & Stress, 31(1), 24–41. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/02678373.2017.1298164

French, K. A., Dumani, S., Allen, T. D., & Shockley, K. M. (2018). A meta-analysis of work-family conflict and social support. Psychological Bulletin, 144(3), 284–314. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/bul0000120

Fritz, C., Sonnentag, S., Spector, P. E., & McInroe, J. A. (2010). The weekend matters: Relationships between stress recovery and affective experiences. Journal of OrganisationalBehavior, 31(8), 1137–1162. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.672

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65

Gonzalez, R., & Griffin, D. (2001). Testing parameters in structural equation modeling: Every “one” matters. Psychological Methods, 6(3), 258–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.6.3.258

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources and conflict between work and family roles. The Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/258214

Guerreiro, M. D., & Abrantes, P. (2007). Transições incertas: Os jovens perante o trabalho e a família [Uncertain transitions: Young people faced with work and family]. CITE.

Hahn, V. C., Binnewies, C., & Dormann, C. (2014). The role of partners and children for employees’ daily recovery. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.03.005

Hammer, L., Kossek, E., Yragui, N., Bodner, T., & Hansen, G. (2009). Development and validation of a multi-dimensional scale of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB). Journal of Management, 35(4), 837–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308328510

Hill, J. (2005). Work-Family facilitation and conflict, working fathers and mothers, work family stressors and support. Journal of Family Issues, 26(6), 793–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X05277542

Jansen, N., Kant, I., Kristensen, T., & Nijhuis, F. (2003). Antecedents and consequences of work-family conflict: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 45(5), 479–491. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jom.0000063626.37065.e8

Kossek, E., Baltes, B. B., & Matthews, R. A. (2011a). How work-family research can finally have an impact in organizations. Industrial and OrganisationalPsychology, 4(3), 352–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2011.01353.x

Kossek, E., Pichler, S., Bodner, T., & Hammer, L. (2011b). Workplace social support and work–family conflict: A meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organisationalsupport. Personnel Psychology, 64(2), 289–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01211.x

Lawson, K. M., Davis, K. D., McHale, S. M., Hammer, L. B., & Buxton, O. M. (2014). Daily positive spillover and crossover from mothers’ work to youth health. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(6), 897–907. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000028

Lobo, F., & Pinheiro, M. (2012). Recovery experiences questionnaire. Adaptação para a população portuguesa [Adaptation for the portuguese population]. Atas do Congresso Internacional de Psicologia do Trabalho e das Organizações, 361–370.

Lucas-Thompson, R. G., Goldberg, W. A., & Prause, J. (2010). Maternal work early in the lives of children and its distal associations with achievement and behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(6), 915–942. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020875

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Multivariate behavioral confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4

Marshall, N. L., & Barnett, R. C. (1993). Work-family strains and gains among two-earner couples. Journal of Community Psychology, 21(1), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(199301)21:1%3c64::AID-JCOP2290210108%3e3.0.CO;2-P

Matias, M. (2019). Género e papéis de género no fenómeno da conciliação trabalho-família: Revisões concetuais e estudos empíricos [Gender and gender roles in work-family conciliation: Conceptual reviews and empirical studies]. In C. Andrade, S. Coimbra, M. Matias, L. Faria, J. Gato, & C. Antunes (Eds.), Olhares sobre a Psicologia Diferencial (pp. 141–162). Mais leitura.

Matias, M., & Fontaine, A. M. (2015). Coping with work and family: How do dual-earners interact? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56(2), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12195

Matias, M., & Recharte, J. (2020). Links between work–family conflict, enrichment, and adolescent well-being: Parents’ and children’s perspectives. Family Relations, 70(3), 840–858. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12453

Matias, M., Ferreira, T., Vieira, J., Cadima, J., Leal, T., & Mena Matos, P. (2017). Workplace family support, parental satisfaction, and work-family conflict: Individual and crossover effects among dual-earner couples. Applied Psychology, 66(4), 628–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12103

Matias, M., Ferreira, T., & Matos, P. M. (2022). “Don’t bring work home”: How career orientation moderates permeable parenting boundaries in dual-earner couples. Journal of Child and Family Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02290-5

Moreno-Jiménez, B., Mayo, M., Sanz-Vergel, A. I., Geurts, S., Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., & Garrosa, E. (2009). Effects of work–family conflict on employees’ well-being: The moderating role of recovery strategies. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(4), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016739

Murgia, A., & Poggio, B. (2009). Challenging hegemonic masculinities: Men’s stories on gender culture in organizations. Organization, 16(3), 407–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508409102303

O’Driscoll, M. P., Poelmans, S., Spector, P. E., Kalliath, T., Allen, T. D., Cooper, C. L., & Sanchez, J. I. (2003). Family-responsive interventions, perceived organisationaland supervisor support, work-family conflict, and psychological strain. International Journal of Stress Management, 10(4), 326–344. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.10.4.326

Perista, H., Cardoso, A., Brázia, A., Abrantes, M., & Perista, P. (2016). Os Usos do Tempo de Homens e de Mulheres em Portugal [Time usage by men and women in Portugal]. Centro de Estudos para a Intervenção Social.

Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., Sanz-Vergel, A. I., Antino, M., Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2018). Positive experiences at work and daily recovery: Effects on couple’s well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(5), 1395–1413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9880-z

Santos, G. G. (2010). Gestão, trabalho e relações sociais de género [Management, labor and social gender relations]. In V. Ferreira (Ed.), A Igualdade de Mulheres e Homens no Trabalho e no Emprego em Portugal: Políticas e Circunstâncias (pp. 99–138). CITE.

Saxbe, D. E., Repetti, R. L., & Graesch, A. P. (2011). Time spent in housework and leisure: Links with parents’ physiological recovery from work. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(2), 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023048

Schweizer, K. (2010). Some guidelines concerning the modeling of traits and abilities in test construction. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000001

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In S. Leinhart (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 290–312). Jossey-Bass.

Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). The recovery experience questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(3), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.204

Sonnentag, S., Mojza, E. J., Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). Reciprocal relations between recovery and work engagement: The moderating role of job stressors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(4), 842–853. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028292

Sonnentag, S., Venz, L., & Casper, A. (2017). Advances in recovery research: What have we learned? What should be done next? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000079

Sonnentag, S., Cheng, B. H., & Parker, S. L. (2022). Recovery from work: Advancing the field toward the future. Annual Review of Organisational Psychology and Organisational Behavior, 9, 33–60. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-091355

ten Brummelhuis, L., van der Lippe, T., & Kluwer, E. (2009). Family involvement and helping behavior in teams. Journal of Management, 36(6), 1406–1431. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309350778

ten Brummelhuis, L., Haar, J., & van der Lippe, T. (2010). Crossover of distress due to work and family demands in dual-earner couples: A dyadic analysis. Work & Stress, 24(4), 324–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2010.533553

Thomas, L., & Ganster, D. (1995). Impact of family-supportive work variables on work family conflict and strain: A control perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.80.1.6

Thompson, C. A., Beauvais, L. L., & Lyness, K. S. (1999). When work–family benefits are not enough: The influence of work–family culture on benefit utilization, organisationalattachment, and work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(3), 392–415. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1681

Vieira, J. M., Lopez, F. G., & Matos, P. M. (2014). Further validation of Work-Family Conflict and Work-Family Enrichment Scales among Portuguese working parents. Journal of Career Assessment, 22(2), 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072713493987

Wall, K. (2005). Famílias em Portugal: Percursos, interacções, redes sociais [Families in Portugal: Paths, interactions, social networks]. Imprensa de Ciências Sociais.

Funding

This work was funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology Portugal (CPUP/UIDB/00050/2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Garraio, C., Barradas, M.I. & Matias, M. Organisational and Supervisor Support Links to Psychological Detachment from Work: Mediating Effect of Work-family Conflict on Dual-earner Couples. Applied Research Quality Life 18, 957–974 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-022-10124-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-022-10124-1