Abstract

All professions include work and pay and some prior studies have pointed to the role that professional identity might play in the relationship between work conditions and job satisfaction. Based on data collected from rural teachers in mainland China, this study used two-level modelling to examine the moderating effects of teacher’s professional identity (TPI) on their job satisfaction. Our research findings confirm that longer work hours, larger class size, and lower perception of income status are significantly associated with lower levels of job satisfaction, and TPI can moderate the negative effects caused by work hours and income status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For most employees in most professions, what they desire is little more than less work and more pay. This traditional understanding of profession has been theorised and examined repeatedly in a large body of literature in the social sciences, notably in personnel management and applied psychology (Kifle 2013; Boxall and Macky 2014). From the perspective of personnel management, the productivity of any employee depends on a trade-off between leisure and work given an appropriate level of wages. From the perspective of applied psychology, workers tend to report higher level of satisfaction with greater rewards in a less stressful environment. However, to those who enter and stay in the teaching profession, the value they place on their job goes above and beyond this trade off. As highlighted by the report of Primary Sources: America’s Teachers on Teaching in an Era of Change (Scholastic 2013), 85% of American teachers surveyed shared the same opinion that their choice of being a teacher was to make a difference in children’s lives. Moreover, a striking fact is that these teachers have to face a challenging working time of more than 10 h per workday. Unsurprisingly, this recognition of the teaching profession is not unique in the US, but also in other parts of the world, especially those developing countries like China. We are not arguing that teachers are workaholics who completely violate the conventional rules of work and pay, but suggest that researchers should go beyond the traditional links between work or pay and job satisfaction, and explore what the their perceptions of the teaching professions can enrich the understanding on their job satisfaction.

China, a country characterised by its huge population and fast pace of transformation, is considered one of the ideal laboratories for social experiments. Based on a sample of rural teachers in mainland China, this study seeks to contribute in two aspects. First, despite of numerous studies on the relation between work conditions and job satisfaction in general professions (Kifle 2013; Angrave and Charlwood 2015; Grund and Rubin 2017; Piasna 2018), the multi-facet nature of work conditions has not been completely examined in teaching profession, especially with Chinese samples. Thus, with varied measures of work conditions ranging from workload (time and intensity) to income (real and relative), the present study seeks to identify the most pronounced factors that predict rural teachers’ job satisfaction. Second, the important role of professional identity has been discussed thoroughly in educational research for decades (Beijaard et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2016), while quantitative studies are relatively rare (Lentillon-Kaestner et al. 2018), with a lack of in-depth analysis focused on its moderation mechanism on the association between work conditions and job satisfaction. The present study also seeks to fill this literature gap with empirical evidence from rural China.

Literature Review

Workload and Job Satisfaction

Workload is a broad concept, which can be further clarified from two facets - time and intensity. (Fiksenbaum et al. 2010). Work time is used frequently in empirical studies, since it is a straightforward notion with conventional principles and clear measures (Angrave and Charlwood 2015). On the other hand, intensity is characterised by the process and organization of specific work, resulting in a relatively limited amount of research. More recently, Piasna (2018) proposed that time and intensity are two separate yet interrelated dimensions to characterise work, and we follow this claim to review the existing literature with a focus on the relation between workload and job satisfaction.

There is a large body of literature examining the association between workload and job satisfaction (or broadly speaking, well-being). At the international level, some cross-cultural (Spector et al. 2004) and cross-country (Drobnic et al. 2010) comparisons have been made. At the national level, empirical studies have been conducted with national survey data from developed economies such as New Zealand (Boxall and Macky, 2014) and UK (Angrave and Charlwood 2015), while developing economies like China are rarely touched. An early study of Spector et al. (2004) found insignificantly negative correlations between work time and job satisfaction in a sample of 768 Chinese managers. More recently in a sample of Chinese hotel managers, Fiksenbaum et al. (2010) also found that neither work hours nor work intensity were significant predictors on job satisfaction.

In the context of school, workload is a preferred term used to indicate the hours worked for teaching and teaching-related tasks, while in some cases, it can also be interpreted as work intensity (Ballet and Kelchtermans 2009). The work of teachers is usually characterised as challenging and complex (Scholastic 2013), thereby resulting in a variety of workload measures such as actual work hours, perceived workload, and class size (Ost and Schiman 2017) in the empirical literature. Compared with other similar professions, teachers tend to work longer and more intensively. Therefore, researchers are inclined to presume workloads as a major source of work stress or burnout, and accordingly link it with teacher job satisfaction (Klassen and Chiu 2010). A search of related literature revealed that only a few empirical studies have been conducted based on Chinese samples. With a rural teacher sample from Chinese Gansu province, Sargent and Hannum (2005) found that longer work time measured by teaching hours and lesson planning was significantly positively related to job satisfaction. However, the limitations of this study are quite clear: (1) first, it oversimplified the measures of job satisfaction, with just one single item of ‘Is teaching your ideal career?’ (1 = yes, 0 = no); (2) second, it did not include any variable to measure the intensity facet of workload in the regression model. These literature gaps will be filled in the present study, with better measurement and rich variables in terms of both work time and intensity.

Pay and Job Satisfaction

It seems reasonable that the more you get paid, the better you feel about your job. However, doubt has been cast on this link, first by economists, then by psychologists and political scientists (Clark et al. 2008), which increasingly found evidence that well-being does not accompany increased income. Investigations into this paradox enrich scholars’ understanding on the pay-satisfaction link, and some explanations have been made by developing alternative measures of income, not in terms of its exact indicators (such as salary, wage, compensation, or remuneration), but in terms of absolute (or real) and relative (or comparative) indicators. Owing to a long-established tradition in economics to hypothesise and examine the relation between relative income and satisfaction (or more economically, utility) (Duesenberry 1949; Easterlin 1973), volumes of empirical studies have been accumulated, with renewed interest in developing different instruments to deliberately quantify the effects of absolute and relative income on job satisfaction (Ferrer-i-Carbonell 2005; Kifle 2013; Grund and Rubin 2017). Notably, most of these instruments are derived variables by transforming the actual income data, seldom taking account of individual’s perception of their income status. Recently, this research gap has been addressed by some preliminary explorations with instruments from a subjective or psychological perspective, and some empirical evidence has been provided in European samples (Pereira and Coelho 2013a; Camfield and Esposito 2014).

For teaching profession, salary level is also a key determinant on teachers’ choice, attrition, and turnover (Guarino et al. 2006). Therefore, empirical evidence on the relationship between pay and job satisfaction is easy to find, though the results seem to be mixed across countries. With two studies of cross-sectional data collected in the UK in 1962 and 2007, Klassen and Anderson (2009) found that compensation was always one of the most important factors for teachers’ job satisfaction. A newly-published work completed by Roch and Sai (2017), with data from School and Staffing Survey of the US, revealed that salary level (measured by academic year based school-related income) was significantly positive related with job satisfaction, and also a major reason for lower satisfaction among Charter school teachers. Nevertheless, relevant studies with Chinese data are very rare. In an early study with a rural Chinese sample (Sargent & Hannum, 2005), the absolute monthly salary was found to have a negative but insignificant effect on job satisfaction, but the dummy variable indicating salary paid on time was extraordinarily positive and significant.Footnote 1 To the best of our knowledge, the measure of perceived income has seldom been used in studies related to teacher job satisfaction, let alone a comparison between real income and perceived income with Chinese data. This literature gap (mainly in educational studies) will be addressed in the present study, by including the variables of real income and perceived income status in the model, and comparing their effects on job satisfaction.

Teachers’ Professional Identity (TPI) and its Moderation Role

Despite of its lengthy heritage in provoking intellectual debates, identity can be generally defined as an individual’s subjectively construed understanding of who they are in certain settings (Brown 2015). Modern society continuously enriches notions of identity, and distinctions have been made between personal identities, social identities, role identities, and organizational identities from different disciplinary perspectives (Knights and Clarke 2017). Concerning individual’s perception of ‘self’ as a worker in her/his profession or occupation, the notion of professional identity is often employed and discussed. For educational researchers, conceptualizing professional identity is also a tough task - one should not only answer to the general question of ‘Who am I at this moment?’ (Beijaard et al. 2004), but also the more in-depth question of ‘How do I see my role as a teacher?’ (Cheung 2008). The long journey of answering these questions has been accompanied with the rising role of TPI in understanding teachers’ choice, devotion, turnover, and retention (Beijaard et al. 2004; Beauchamp and Thomas 2009).

A substantial literature has focused on clarifying the definition of TPI (Beijaard et al. 2004; Day et al. 2006; Beauchamp and Thomas 2009), while no explicit agreement was achieved to date. This partly reflects the complexity of the notion, with its multidimensional, integrated, and dynamic nature embedded in the teaching profession in various school settings. The nature of multidimensionality can be found in its close relations with relevant notions such as teacher value, belief, commitment, engagement, as well as agency. However, all these elements are integrated rather than fragmented in professional identity. As suggested in by Beijaard et al. (2004), TPI consistent of sub-identities that more or less harmonise. The nature of dynamics has been discussed thoroughly by Day et al. (2006), concluding that the notion of TPI is sometimes interwoven with not only teachers’ work but also teachers’ life, thus entailing certain dynamics caused by a number of life and career factors. This dynamic nature has also drawn much scholarly attention to investigate the formation and development of professional identity, for both in-service teachers (Sachs 2001) and student teachers (Lamote and Engels 2010; Izadinia 2012).

There is a tradition in educational studies to investigate teacher professional identity through a qualitative approach, particularly featured by narrative analysis of interview data (Lentillon-Kaestner et al. 2018). Some quantitative analyses have emerged more recently, overemphasise the multidimensionality of the notion, and are inclined to use a package of different instruments to measure some separate sub-identities, such as professional orientation, teacher self-efficacy, and commitment to teaching (Schepens et al. 2009; Lamote and Engels 2010; Eren and Söylemez 2017). More recently, a teacher-specific instrument has been proposed and validated by Zhang et al. (2016), with its unique application in a Chinese sample of student teachers. Nevertheless, most of the existing scales seem not to be appropriate for measuring TPI in rural context. In this circumstance, the present study goes back to the substantive questions of ‘How do I see myself as a teacher?’ (Cheung 2008), and employs an operational definition of TPI as how teachers value and recognize their profession.

With regard to the conventional claim on the positive relationship between professional identity and job satisfaction in other professions (Mottaz 1986; Magee 2015), relatively little empirical evidence has been provided for the teaching profession. Owing to the continuing interest in studying the relation between TPI and teacher attrition, empirical evidence can be found to support the claim that TPI play an influential part in teachers’ career decisions, especially for those teaching in disadvantaged settings like urban schools in the US (Schepens et al. 2009; Lamote and Engels 2010). More prominently, some strong evidence can be found in the latest working paper completed by Mostafa and Pál (2018). Using data from the PISA 2015 teacher questionnaire, their research confirms that pursuing a professional career is highly related to teacher job satisfaction in most participating economies, which is even stronger in China. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that this positive relationship can be found in the sample of rural Chinese teachers in the current study.

Lastly, as the research boundary of job satisfaction is pushed forward in applied psychology, increasing interest has been extended to social cognitive factors like organizational support (Baranik, Roling, & Eby, 2010), and also to the moderators between job satisfaction and its determinants (e.g., work hour or salary). For instance, Malka and Chatman (2003) examined the moderating role of work orientation on the relationship between income and job satisfaction in a sample of MBA graduates, and Pereira and Coelho (2013b) used data from European Social Survey to test the moderating role of occupational identity on the relationship between work hours and job satisfaction. Similar examination has also been conducted with a sample of front-line workers in a Chinese manufacturer. However, to the best of our knowledge, no such research has been conducted within teaching professions. To this end, the moderation analysis with Chinese rural teacher data can be a major contribution to the existing literature.

Method

Research Context

As the most prominent emerging economy, people in mainland China have experienced unprecedented changes of modernization and urbanization over past decades, whereas some pronounced differences and gaps in terms of economy, society and culture have been debated by researchers (Xie and Hannum 1996; Wu and Li 2017). These differences demands the data for analysis to be as inclusive as possible, in order to achieve certain degree of representativeness. To this end, the survey was conducted in 10 provinces located in different regions of China: Jiangsu, Fujian, and Jilin in the east; Hunan, and Henan in the central; and Sichuan, Inner Mongolia, Guizhou, and Gansu in the west. In each province, three counties with rich, moderate and poor economic conditions were selected respectively.Footnote 2 The final sample included a total of 3757 rural teachers from 29 counties surveyed in the summer of 2015.

Some facts on the economic status of the surveyed counties would be illustrative. Table 1 presents a list of the surveyed counties with four indicators attached to demonstrate their overall economic conditions (GDP per capita) and economic inequalities (Urban-rural income ratio). Obviously, substantial regional economic gaps can be found between provinces. Two typical cases are the rich Jiangsu province in East China and the poor Gansu province in West China. Moreover, within the same province, there also exist considerable economic gaps between counties. In Gansu province, the GDP per capita of Dunhuang county is more than 10 times that of Dongxiang county. Additionally, across all counties on the list, the rural areas are generally left far behind the urban areas, with the urban-rural income gap ranging from 1.43 to 3.44.

The urbanisation rate presented in Table 1 reveals that a high proportion of Chinese people are still living in rural areas where millions of teachers are urgently needed. According to latest data released by China Ministry of Education, there are over 3 million teachers working in rural schools, most of which are surrounded by high poverty, limited teaching resources, and the neediest students. The work conditions for rural teachers are extremely hard, followed by heavy workload and disproportionate compensation. As suggested by an early survey conducted in Gansu Province, the weekly hours spent by rural teachers on instructing students and grading homework were 39 on average, plus some 4 or 5 h a week for other teaching-related activities (Sargent & Hannum, 2005). In today’s rural schools with an increasing demand for accountability, extra burdens are put on rural teachers as required by local government such as submission of monthly monitoring reports or regular visits to the left-behind children with no parents at home.

Rural teachers’ salary level is fairly good when compared with their rural neighbours, largely owing to their status being recognised as state employees which secures their salaries to be part of county government’s budget. For those who teach in the poorest rural areas characterised by remoteness, minority, and high deprivation, remote allowance is added to compensate for the hardships. However, even taking these into account, the total salary of rural teachers is still far less than those urban counterparts, as demonstrated by the indicator of Province-county teacher income ratio in Table 1.

Sample

The quantitative analysis of present study is mainly based on the survey sample mentioned above. Focusing on analysing rural teacher job satisfaction considering workload, salary, and professional identity, we processed the original sample by excluding those cases with missing values on the relevant items, which reduced the sample into 3041 teachers. The final sample consisted of 1764 female teachers (58.01%) and 1277 male teachers (41.99%), demonstrating that teaching is a female-preferred profession in rural China. The majority of teachers were aged over 30 (75%), with an average age of 37.8. All these teachers had obtained a teaching certificate, though many teachers had not earned a bachelor degree (36.15%), giving them an average of 15.5 years of schooling.

Outcome Variable: Job Satisfaction

Drawing on some prior studies on job satisfaction (Bowling et al. 2010; Lent et al. 2011) as well as a job satisfaction scale from the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2013 teacher questionnaire (OECD 2014), the present study measured job satisfaction using a 4-point scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’, 2 = ‘slightly disagree’, 3 = ‘slightly agree’, 4 = ‘strongly agree’). Rural teachers surveyed were asked to respond to the following four items, ‘I’m positive towards my teaching career’, ‘I’m satisfied with current work conditions’, ‘I feel happy as an educator’, and ‘Teaching makes the value of my life fulfilling’. All the responses were summed to create a continuous variable, with higher scores indicating higher levels of job satisfaction. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.801, demonstrating high internal consistency.

Main Explanatory Variables

Class hour and work hour are variables to measure teachers’ work time. Class hour refers to the average in-class hours a rural teacher should spend teaching the lessons and instructing the students in the classroom. It contributes to the main body of the required school hours. The number of class hours that each rural teacher reported in the questionnaire was used as a continuous variable for instruction hours. Work hour refers to the average hours a rural teacher should spend on all teaching-related activities including but not limited to in-class instruction, student tutoring and supervision before and after class, lesson planning, grading and documenting student work, and communication with colleagues and parents, etc. The number of work hours reported by rural teachers in the questionnaire was also used as a continuous variable.

Class size and class number are variables to measure teachers’ work intensity. Class size refers to the average number of students in the classrooms that a rural teacher teaches. An index of class size is generated by recoding the actual numbers reported by rural teachers, ranging from 1 (=less than 10 students) to 11 (=more than 100 students). Class number refers to the total number of classes that a rural teacher teaches in one semester. The actual numbers reported by rural teachers are used as a continuous variable.

Real income refers to the net compensation in terms of Chinese yuan earned by rural teachers on average in each month. Considering that teacher salary is usually paid on a monthly base in China, we use the actual money that a rural teacher earned every month on average to measure their real income.

Perceived income status refers to rural teachers’ perception of their relative income status compared with reference groups. Participants rated two items (‘compared with those public servants in your county, your salary level is’, ‘compared with your friends, your salary level is’) with five options (1 = much lower, 2 = slightly lower, 3 = almost the same, 4 = slightly higher, 5 = much higher). All the responses were reverse coded and then averaged to generate a new variable of perceived income status. Higher scores indicate lower perception of income status compared with public servants and friends.

Moderating Variable: TPI

The measure for TPI was adapted from some prior studies (Lamote and Engels 2010). Respondents were asked to rate on the following 4 items: ‘Teaching is a decent profession’, and ‘I would like to tell my relatives and friends that I am a teacher’,‘I would let my children be a teacher’, ‘I would let my children choose teaching profession’. Each item was provided with 4 options labelled as 1 = ‘strongly disagree’, 2 = ‘slightly disagree’, 3 = ‘slightly agree’, 4 = ‘strongly agree’. All The responses were averaged to create an index, with higher scores indicating higher levels of professional identity. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.824, showing high internal consistency.

Control Variables

Considering the hierarchical structure of the survey data, an array of control variables at individual and county level was included in our quantitative analysis. At the individual level, there are three commonly used demographic variables, gender (1 = female, 0 = male), age (continuous), and education (9 = lower secondary, 12 = higher secondary, 15 = higher vocational, 16 = bachelor, 19 = master). At the county level, GDP per capita was used to control for local economic conditions, and urban-rural income ratio was used to control for the economic inequality within the same county.

Analytical Approach: Two-Level Linear Modelling

The sampling design formulated the data into a hierarchical structure with individual teachers nested within counties, and thus called for the application of a two-level linear modelling technique for our quantitative approach. With reference to the empirical guidance made by Raudenbush and Bryk (2002), a random-intercept model has the advantage of better estimation of level 1 (in this case the teacher-level) standard errors by considering clusters, and allowing for the intercept to be randomised caused by some county level (level 2) factors. To capture the moderation effects of TPI, interaction terms of the main explanatory variables with TPI are also included in the teacher-level equation. Therefore, the full model addressing our research question can be specified as follow:

-

Level 1 (teacher level):

-

Level 2 (county level):

In the two equations above, subscripts i and j denote teacher and county respectively. All variables included in the above equations have been clarified in the previous section. The econometric package Stata 13 will be used for estimating the model, with the latest updated command mixed.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 2 presents the brief description and descriptive statistics for all variables. Table 3 presents the correlation matrix for the main variables. Job satisfaction for rural teachers was found to have a negative and statistically significant correlation with all four variables regarding workload. Among the four variables, class size and work hour have the strongest relationship with job satisfaction, while the association between class hours and class numbers are much weaker. Concerning the variables for teacher salaries, both are significantly correlated with job satisfaction – positively for real income and negatively for perceived income. The most strongest correlation to job satisfaction is found in the variable of professional identity, demonstrating that higher level of professional identity is associated with higher level of job satisfaction.

Moderation Analysis

Four steps were taken to achieve the final analysis of moderation effects. In the first, an unconditional model of rural-teacher job satisfaction was examined to examine the appropriateness of applying HLM, as suggested by Raudenbush and Bryk (2002). The intra-class correlation (ICC) coefficient reported by Stata was 0.08 (p < 0.01), reaching the criterion of above 0.05 for multi-level modelling. This result also demonstrates that some proportion of the total variance of job satisfaction (8%) is attributed to county-level factors, and a larger proportion is dependent on teacher-level factors. A Likelihood-ratio test was also conducted to check the fitness of a two-level model against a linear regression model, and the results showed that the two-level model was a better fit to our data than linear regression (χ2 = 196.18, p = 0.00 ).

In the second step of the analysis, we ran model 1 with the four main explanatory variables for workload (control variables at both individual and county levels were included). The aim of this step was to investigate which workload factors are the most important to rural teacher job satisfaction. The results of model 1 are presented in the first column of Table 4. Clearly, all four variables are negatively related to job satisfaction as expected, but differ in significance and effect size. In the time dimension for workload, the effect of work hours is significant (β2 = − 0.130, p < 0.01), but not the effect of class hours(β1 = − 0.013, p > 0.1), and the effect size of the former is almost ten times that of the latter. This finding demonstrates that job satisfaction of rural teachers is more sensitive to the time spent beyond teaching tasks in required school hours. In the intensity dimension for workload, the effect of class size is significant(β4 = − 0.151, p < 0.01), but not the effect of class number(β3 = − 0.034, p > 0.1). This finding demonstrates that, compared with more frequent class changes in daily teaching, rural teachers tend to be less satisfied with large class sizes. Class change means shifting between different groups of students, while class size means control of classroom discipline.

In the third step of the analysis, we ran model 2 with two main explanatory variables of for salary. The aim of this step was to compare the effects of perceived income to real income. The results of model 2 are presented in the second column of Table 4. As revealed by the correlation results in Table 3, both real and perceived income have a significant relationship with job satisfaction. However, the results of two-level linear regression show an entirely different picture; perceived income still has a significantly negative effect on job satisfaction (β6 = − 0.907, p < 0.01), but the effect of real income (β5 = − 0.223, p > 0.1) becomes negative though no longer significant. This finding demonstrates that the rural teachers’ perception of relative income is a much stronger predictor of their job satisfaction.

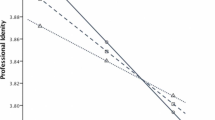

In the final step of the analysis, we ran the full model (or model 3) with all main explanatory variables, moderation variables, and the interaction terms. The aim of this step was to examine the moderating effects of TPI on the relationship between workload or income and job satisfaction. As the results show in the last column of Table 4, of all seven main effects, two are statistically significant: work hours (β2 = − 0.266, p < 0.01) and perceived income (β6 = − 0.643, p < 0.01); similarly, the interaction effects of these two variables with TPI also reach acceptable statistical significance: TPI × Work hour (β9 = 0.097, p < 0.01) and TPI × Perceived income(β13 = 0.147, p < 0.01). These results confirm that TPI moderates the negative effects of work hours and perceived income on rural teacher job satisfaction. These results confirm that TPI moderates the negative effects of work hours and perceived income on rural teacher job satisfaction. More specifically, despite the significantly negative effect that work hours has on job satisfaction, those teachers with higher levels of TPI tend to feel more satisfied than those with lower levels of TPI. Similarly, though perceived income significantly attenuates job satisfaction, those rural teachers with higher levels of TPI are more likely to feel more satisfied.

Discussion

Workload and Rural Teachers’ Job Satisfaction

It is no doubt that most rural teachers in China are struggling with high workloads; however, what aspects matter more is far from clear in the existing literature. Our study examined teaching load from dimensions of time and intensity, and singled out two specific variables that significantly attenuate teachers’ job satisfaction – work hours and class size. In rural classrooms consisting mainly of economically and academically disadvantaged students, teachers spend a disproportionate amount of time on non-teaching work. When dealing with large class sizes, the situation may be worsened due to inadequacy of infrastructure and equipment. Both factors are devastating, resulting in higher work stress and lower job satisfaction, and consequently lower teaching quality and higher attrition rate. These findings enrich our understanding of teachers’ work in high poverty settings, and suggest possible solutions for how to improve the levels of job satisfaction.

First, more efficient ways can be developed to help rural teachers save their non-teaching time and set them free from overwork after class. The time for lesson planning may be an appropriate case. As a Chinese proverb goes, ‘ten years preparation for one minute on the stage’, which means that teachers spend much more time on lesson planning than classroom teaching. In this vein, if teachers could be more efficient on lesson planning, their job satisfaction would possibly soar. Actually, the teaching and research section (or jiaoyanzu in Chinese) is just a feasible choice. As highlighted repeatedly by some PISA official report (OECD 2016), this section is well established and highly institutionalised in Chinese schools located in large cities like Shanghai (Cheng 2011), and works like a small professional learning community consisting of junior and senior teachers, usually in the same field. Through regular activities (about once a week) with colleagues in the same field, teachers reflect on their instructions and make progress through joint lesson planning. Metaphorised by Sargent and Hannum (2009) as ‘doing more with less’, a well-organised section has evidenced to be an effective model in resource-constrained rural schools, and its positive link with job satisfaction has also been confirmed (Sargent & Hannum, 2005).

Second, reduction of class size as a teacher-friendly policy is worth putting into practice in rural China. Though debates continue on its costs and benefits, class size reduction has been highly emphasized by educators in some developed countries. As the analysis made by Barbarin and Aikens (2015) suggests, smaller class size is of great importance for those teaching in disadvantaged settings facing students with low SES and competencies, since it helps lower teachers’ efforts on classroom discipline, and improve students’ achievement and sense of belonging. This has been further evidenced by the latest report based from OECD based on the PISA 2015 data, which confirms that science teachers’ job satisfaction is significantly positively related to students’ sense of belonging (Mostafa and Pál 2018). Notwithstanding the increasing commitment to reduce class size in developing countries as a means to enhancing educational quality, currently in rural China, it is still hard to form a national policy under the constraint of the government budget. More importantly, the class size effects on students’ achievement and teacher outcomes has yet be thoroughly studied, therefore further research is greatly needed.

Pay and Rural Teachers’ Job Satisfaction

The results of model 2 show the dominant effect of perceived income status relative to real income on rural teacher job satisfaction. This finding does not necessarily suggest that rural teachers are not concerned with the amount of money they can get, but rather informs us that how they evaluate their income status is much more important in determining their level of job satisfaction. In fact, compared with the rural residents, the salaries of rural teachers are substantially higher owing to the financing mechanism we have mentioned previously, and this salary premium is particularly prominent in those counties suffering from high deprivation. Some extra calculations are helpful in illustrating this: the income gaps between the average teacher (constructed by using average yearly salary in the sample county) and average rural resident (using disposable income) can range from 1.48 (Changshu county in the rich Jiangsu province) to 8.63 (Dongxiang county in the poor Gannsu province). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the absolute economic status of rural teachers can hardly be a damaging factor attenuating their job satisfaction.

In contrast, the economic status of rural teachers is very low compared with those working and living in the cities, especially in the context of urbanization in which rural land is being lost (Xie and Hannum 1996). Moreover, as a large proportion of rural teachers have received higher education (in our sample above 60%), they are more sensitive to what happens beyond the rural places and teaching profession, and thus more liable to be unhappy with the comparison. Therefore, it is reasonable for those rural teachers with lower perception of salary status to feel less satisfied with their job. The implication of this research finding is quite straightforward.

Lastly, some points should be made to direct our future research on the relationship between income and job satisfaction. Our research made comparisons between real income and perceived income, while leaving out those frequently used measures of relative income in economic studies. It would be better to include some relative income index of rural teachers to other comparable workers in the modelling, and examine effects of real income, relative income and perceived income.

Moderating Effects of TPI

Our quantitative results have shown the moderation effects of TPI on work hour and perceived income. Both effects can be interpreted more illustratively by comparing the groups with mean above and below one standardized deviation (see Figs. 1 and 2). As shown in Fig. 1, for rural teachers with lower level of TPI (Low = mean – 1SD), a negative association emerged between work hour and job satisfaction, while among those rural teachers with higher level of TPI (High = mean + 1SD), a positive association was found. Similarly but differently in Fig. 2, for rural teachers with lower level of TPI (Low = mean – 1SD), a negative association emerged between perceived income and job satisfaction, while among those rural teachers with higher level of TPI (High = mean + 1SD), a slightly less negative association was found.

Moderation effect of TPI on the relation between work hour and job satisfaction. The graph was created with www.jeremydawson.co.uk/slopes.htm. High = mean + 1SD. Low = mean – 1SD

Moderation effect of TPI on the relation between perceived income and job satisfaction. The graph was created with www.jeremydawson.co.uk/slopes.htm. High = mean + 1SD. Low = mean – 1SD

The importance of TPI has been emphasised for decades among educational researchers. Our research finding regarding its moderating effects not only supports this emphasis with empirical evidence, but also enriches our understanding of the relationship between challenging work conditions and rural teachers’ job satisfaction in the teaching profession. With regard to the moderating effect on workload and job satisfaction, our finding accords with those from some larger surveys in the western culture (e.g., Pereira and Coelho 2013b), but a more interesting explanation can be given for our case in the current study. As claimed repeatedly by educational studies that teaching is not merely a job, but a mission to make a difference in children’s lives (Scholastic 2013), there are always a group of teachers (certainly not all of them) more inclined to devote their whole lives to teaching, regardless of the longer hours. Those teachers with stronger professional identity certainly belong to this group, and are usually characterised by their higher level of commitment to teaching, often in terms of longer work hours; heavy workloads are the norm for rural teachers in disadvantaged schools full of left-behind children. However, for those with stronger professional identity, the more time spent with those high-needs students, the more satisfaction they can experience, regardless of all the hardships.

With regard to the moderating effect on perceived income and job satisfaction, the above logic is also partly applicable, but the underlying story might be different. As suggested by numerous studies debating the Easterlin Paradox, higher subjective well-being is decisively accompanied by higher income, and is also dependent on individuals’ perception of their relative income status. For a large proportion of rural teachers, they have already obtained considerably higher salaries than local rural residents, but not all of them hold a higher level of perception of their income status. For those with stronger professional identity, they are more likely to accept the income status of rural teachers, be more accustomed to the style of rural living, and be more satisfied with their current situation. We do not mean to argue that these rural teachers are blinded by their professional identity as a teacher, but greatly motivated by their profession to put less weight on how much they can get and more weight on how much they can give.

Concluding Remarks

Based on a large sample of rural teachers in 29 counties across 10 provinces in mainland China, the present study examined the relationship between working conditions and job satisfaction. Our research findings confirmed that rural teachers who worked longer hours and had lower perceived income level tended to experience less job satisfaction, while TPI can play an essential role in moderating this relationship between hardship in work and job satisfaction. These research findings can shed light on how to increase rural teachers’ job satisfaction and improve their quality of life. This is particularly important considering some recent observations on the extremely low level of job satisfaction among Chinese teachers (Mostafa and Pál 2018).

Finally, the limitation of this research should be noted. Some instruments used in the study need to be improved. Though some scholars have claimed the feasibility of using a concise instrument or even a single-item instrument to measure complex constructs such as job satisfaction (Dolbier et al. 2005), the complexity and multidimensionality of some constructs (particularly TPI) still call on us to utilise some newly-developed instruments (e.g. Zhang et al. 2016; Lentillon-Kaestner et al. 2018) in future research.

Notes

This partly reflects the special context in rural China at that time, when local government budgets were extremely limited, and their payment to teachers was usually postponed. Thereby, compared with the amount of money, the money that can be obtained on time is much more important. However, this situation has been changed following the reform of financing mechanism in 2005. See (Zhao 2009) for details.

The exception is Jilin province, where the data of the county with moderate economic condition are all missing.

References

Angrave, D., & Charlwood, A. (2015). What is the relationship between long working hours, over-employment, under-employment and the subjective well-being of workers? Longitudinal evidence from the UK. Human Relations, 68(9), 1491–1515.

Ballet, K., & Kelchtermans, G. (2009). Struggling with workload: Primary teachers' experience of intensification. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(8), 1150–1157.

Baranik, L. E., Roling, E. A., & Eby, L. T. (2010). Why does mentoring work? The role of perceived organizational support. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(3), 366-373.

Barbarin, O. A., & Aikens, N. (2015). Overcoming the educational disadvantages of poor children: How much do teacher preparation, workload, and expectations matter. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(2), 101–105.

Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 175–189.

Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on Teachers' professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 107–128.

Bowling, N. A., Eschleman, K. J., & Wang, Q. (2010). A meta-analytic examination of the relationship between job satisfaction and subjective well-being. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4), 915–934.

Boxall, P., & Macky, K. (2014). High-involvement work process, work intensification and employee well-being. Work Employment & Society, 28, 963–984.

Brown, A. D. (2015). Identities and identity work in organizations. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(1), 20–40.

Camfield, L., & Esposito, L. (2014). A cross-country analysis of perceived economic status and life satisfaction in high- and low-income countries. World Development, 59(3), 212–223.

Cheng, K. (2011). Shanghai: How a big city in a developing country leaked to the head of the class. In M. S. Tucker (Ed.), Surpassing Shanghai: An agenda for American education built on the world's leading systems (pp. 21–50). Cambridge: Harvard Education Press.

Cheung, H. Y. (2008). Measuring the professional identity of Hong Kong in-service teachers. Journal of In-service Education, 34(3), 375–390.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. A. (2008). Relative income, happiness and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1), 95–144.

Day, C., Kington, A., Stobart, G., & Sammons, P. (2006). The personal and professional selves of teachers: Stable and unstable identities. British Educational Research Journal, 32(4), 601–616.

Dolbier, C. L., Webster, J. A., McCalister, K. T., Mallon, M. W., & Steinhardt, M. A. (2005). Reliability and validity of a single-item measure of job satisfaction. American Journal of Health Promotion, 19(3), 194–198.

Drobnic, S., Beham, B., & Prag, P. (2010). Good job, good life? Working conditions and quality of life in Europe. Social Indicators Research, 99(2), 205–225.

Duesenberry, J. S. (1949). Income, saving and the theory of consumer behavior. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (1973). Does money buy happiness? The Public Interest, 30, 3–10.

Eren, A., & Söylemez, A. R. (2017). Pre-service teachers' ethical stances on unethical professional behaviors: The roles of professional identity goals and efficacy beliefs. Teaching and Teacher Education, 68, 114–126.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2005). Income and well-being: An empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. Journal of Public Economics, 89, 997–1019.

Fiksenbaum, L., Jeng, W., Koyuncu, M., & Burke, R. J. (2010). Work hours, work intensity, satisfactions and psychological well-being among hotel managers in China. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 17(1), 79–93.

Grund, C., & Rubin, M. (2017). Social comparisons of wage increases and job satisfaction. Applied Economics, 49(14), 1345–1350.

Guarino, C. M., Santibañez, L., & Daley, G. A. (2006). Teacher recruitment and retention: A review of the recent empirical literature. Review of Educational Research, 76(2), 173–208.

Izadinia, M. (2012). A review of research on student teachers' professional identity. British Educational Research Journal, 39(4), 694–713.

Kifle, T. (2013). Relative income and job satisfaction: Evidence from Australia. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 8(2), 125–143.

Klassen, R. M., & Anderson, C. J. K. (2009). How times change: Secondary teachers' job satisfaction and dissatisfaction in 1962 and 2007. British Educational Research Journal, 35(5), 745–759.

Klassen, R. M., & Chiu, M. M. (2010). Effects on teachers' self-efficacy and job satisfaction: Teacher gender, years of experience, and job stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(3), 741–756.

Knights, D., & Clarke, C. (2017). Pushing the boundaries of amnesia and myopia: A critical review of the literature on identity in management and organization studies. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(3), 337–356.

Lamote, C., & Engels, N. (2010). The development of student teachers’ professional identity. European Journal of Teacher Education, 33(1), 3–18.

Lent, R. W., Nota, L., Soresi, S., Ginevra, M. C., Duffy, R. D., & Brown, S. D. (2011). Predicting the job and life satisfaction of Italian teachers: Test of a social cognitive model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(1), 91–97.

Lentillon-Kaestner, V., Guillet-Descas, E., Martinent, G., & Cece, V. (2018). Validity and reliability of questionnaire on perceived professional identity among teachers scores. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 59, 235–243.

Magee, W. (2015). Effects of gender and age on pride in work, and job satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(5), 1091–1115.

Malka, A., & Chatman, J. A. (2003). Intrinsic and extrinsic work orientations as moderators of the effect of annual income on subjective well-being: A longitudinal study. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(6), 737–746.

Mostafa, T., & Pál, J. (2018). Science teachers’ satisfaction: Evidence from the PISA 2015 teacher survey. OECD education working papers (No.168). Paris: OECD Publishing.

Mottaz, C. (1986). Gender differences in work satisfaction, work-related rewards and values, and the determinants of work satisfaction. Human Relations, 39(4), 359–377.

OECD (2014). TALIS 2013 technical report. Retrieved from www.oecd.org/education/school/TALIS-technical-report-2013.pdf. Accessed 06 June 2018.

OECD (2016). PISA 2015 results (Volume II): Policies and practices for successful schools, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Ost, B., & Schiman, J. C. (2017). Workload and teacher absence. Economics of Education Review, 57, 20–30.

Pereira, M. C., & Coelho, F. (2013a). Untangling the relationship between income and subjective well-being: The role of perceived income adequacy and borrowing constraints. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(3), 985–1005.

Pereira, M. C., & Coelho, F. (2013b). Work hours and well-being: An investigation of moderator effects. Social Indicators Research, 111(1), 235–253.

Piasna, A. (2018). Scheduled to work hard: The relationship between non-standard working hours and work intensity among European workers (2005–2015). Human Resource Management Journal, 28(2), 167–181.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and aata. Thousand Oaks: Sage publication.

Roch, C. H., & Sai, N. (2017). Charter school teacher job satisfaction. Educational Policy, 31(7), 951–991.

Sachs, J. (2001). Teacher professional identity: Competing discourses, competing outcomes. Journal of Education Policy, 16(2), 149–161.

Sargent, T.C., Hannum, E. (2005). Keeping teachers happy: Job satisfaction among primary school teachers in rural Northwest China. Comparative Education Review, 49(2), 173–204.

Sargent, T. C., & Hannum, E. C. (2009). Doing more with less: Teacher professional learning communities in resource-constrained primary schools in rural China. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(3), 258–276.

Schepens, A., Aelterman, A., & Vlerick, P. (2009). Student teachers' professional identity formation: Between being born as a teacher and becoming one. Educational Studies, 35(4), 361–378.

Scholastic. (2013). Primary sources: America’s teachers on teaching in an era of change (third edition). Retrieved from http://www.scholastic.com/primarysources/PrimarySources3rdEditionWithAppendix.pdf. Accessed 06 June 2018.

Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., Poelmans, S., Allen, T. D., O'Driscoll, M., Sanchez, J. I., et al. (2004). A cross-national comparative study of work-family stressors, working hours, and well-being: China and Latin America versus the Anglo world. Personnel Psychology, 57(1), 119–142.

Wu, X., & Li, J. (2017). Income inequality, economic growth, and subjective well-being: Evidence from China. Research in Social Stratification & Mobility, 52, 49–58.

Xie, Y., & Hannum, E. (1996). Regional variation in earnings inequality in reform-era urban China. American Journal of Sociology, 101(4), 950–982.

Zhang, Y., Hawk, S. T., Zhang, X., & Zhao, H. (2016). Chinese pre-service teachers’ professional identity links with education program performance: The roles of task value belief and learning motivations. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(348), 1–12.

Zhao, L. (2009). Between local community and central state: Financing basic education in China. International Journal of Educational Development, 29(4), 366–373.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, Y. It’s not only Work and Pay: The Moderation Role of Teachers’ Professional Identity on their Job Satisfaction in Rural China. Applied Research Quality Life 15, 971–990 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09716-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09716-1