Abstract

Work-to-family conflict has been consistently found to be one of the factors impacting workers’ life satisfaction. Prior research has also highlighted how type of employment (self-employed versus employee) impacts life satisfaction. No prior research, however, has examined how type of employment moderates the association between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction. This study adds to the existing literature by examining whether the relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction is moderated by type of employment. Using data from the 2008 National Study of the Changing Workforce (N = 3204), the study finds that work-to-family conflict is negatively correlated with life satisfaction, and that this negative correlation is stronger for those who are self-employed. Overall, this study contributes to the literature by highlighting the moderating effect of type of employment, and therefore deepens the understanding of the relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the main challenges among contemporary US workers is the struggle to balance time and resources between paid work and family responsibilities. Accordingly, much work-family literature has examined work-family conflict (Byron 2005; Michel and Hargis 2008). As noted in some prior studies (Minnotte et al. 2013, 2015; Nelson et al. 2012), work-family conflict implies a reciprocal relationship between work and family, with work affecting family negatively (i.e., work-to-family conflict) and family affecting work negatively (i.e., family-to-work conflict) (Frone et al. 1992; Hill 2005; Voydanoff 2007). Since the present study focuses mainly on work stressors, it only considers work-to-family conflict. The literature examining the consequences of work-to-family conflict is well-established. Prior research has found that higher work-to-family conflict is associated with several negative mental and physical health outcomes (Allen et al. 2000; Bellavia and Frone 2005; Frone 2000). Moreover, higher work-to-family conflict is associated with some negative work-related outcomes (such as lower job satisfaction and decrease in work performance) (Bruck et al. 2002; Netemeyer et al. 1996; van Steenbergen and Ellemers 2009) and some negative non-work outcomes (such as decreased satisfaction with one’s family and lower marital satisfaction) (Aryee et al. 1999; Rupert et al. 2012; Amstad et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2010).

The main goal of this study is to examine the moderating effect of type of employment on the relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction. Overall, prior studies have concluded that higher work-to-family conflict is associated with lower life satisfaction (Kinnunen and Mauno 1998; Netemeyer et al. 1996; Rupert et al. 2012; Wayne et al. 2004). Although this relationship is well-established, only few studies have tested how other variables may strengthen or weaken the negative effects of work-to-family conflict (Huynh et al. 2013; Ngo and Lui 1999; Ugwu and Agbo 2010). Motivated by a comparative lack of scholarly attention to testing such moderating effects, this study specifically explores whether the relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction varies between self-employed workers and traditional employees.

One major limitation in work-family literature, as noted in some prior studies, is that it has focused almost exclusively on individuals who are employed in large businesses and other organizations (Parasuraman and Simmers 2001). Far less attention has been given to understanding work-family balance among self-employed workers and those who operate their own businesses (Loscocco 1997). Despite the recent attention to these workers in some studies (Nordenmark et al. 2012; Annink et al. 2016; Lofstrom 2013), the literature on type of employment is still scant. Moreover, literature on the effect of type of employment on work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction has not been consistent, and has thus produced mixed findings. Some research suggests that self-employed workers might have less work-to-family conflict than traditional employees (Georgellis and Wall 2000; Loscocco 1997; Stephens and Feldman 1997), whereas some other research suggests the opposite trend: higher work-to-family conflict among self-employed workers (Greenhaus and Callanan 1994). In terms of the relationship between type of employment and life satisfaction, prior research is also not consistent (Blanchower and Oswald 1998; Alesina et al. 2004; Markussen et al. 2014).

Using the job demand-control model (Karasek 1979), this study argues that the association between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction varies between self-employed workers versus employees. This study asks the following two research questions: 1) Does work-to-family conflict have an association with life satisfaction for all types of workers? 2) Does type of employment (i.e., self-employed versus employee) moderate the association between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction? To test these research questions, this study uses data from the 2008 National Study of the Changing Workforce (N = 3204). The findings underscore the importance of type of employment in understanding the relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction among US workers.

Work-To-Family Conflict and Life Satisfaction

Prior research has defined work-family conflict as “a form of interrole conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect. That is, participation in the work [or family] role is made more difficult by virtue of the participation in the family [or work] role” (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985, p.77). Work-family research has been founded in role stress theory, which mainly focuses on inter-role conflicts (Barnett and Gareis 2006). The main assumption of role stress theory is that multiple work and family demands are incompatible, which leads to stress. Using this theory, this study conceptualizes work-to-family conflict as the incompatibility between work and family demands arising when one’s responsibilities and roles at work negatively interfere with one’s family roles and responsibilities. In line with the theory, this study expects that higher work-family conflict will be associated with lower life satisfaction.

In terms of the relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction, previous research, including the results from two systematic reviews, shows that these variables are negatively related to each other, with higher levels of work-to-family conflict associated with lower levels of life satisfaction (e.g., Adams et al. 1996; Allen et al. 2000; Hill 2005; Kossek and Ozeki 1998; Netemeyer et al. 1996). Using three samples of elementary and high school teachers and administrators, small business owners, and real estate salespeople, Netemeyer et al. (1996) confirmed significant negative correlations between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction among all three samples. This negative correlation was further supported in two meta-analyses (Kossek and Ozeki 1998; Allen et al. 2000). Some other studies have tested various mediating factors to understand the relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction better (Netemeyer et al. 1996; Perrewe et al. 1999). For instance, an increase in work-to-family conflict leads to lower job satisfaction, which in turn lowers the quality of life (Netemeyer et al. 1996; Rice et al. 1992). Perrewe et al. (1999) examined the mediating role of value attainment, defined as “the extent to which a job helps a worker to attain life values” (George and Jones 1996, p. 319), in the relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction. The results showed that higher work-to-family conflict prevents the attainment of values, which then lowers life satisfaction. Overall, the results showed that value attainment partially mediated the negative effect of work-to-family conflict on life satisfaction.

Some other studies have tested the moderating effects of variables such as self-efficacy, and social support on the relationship between work-to-family conflict and well-being. Self-efficacy, which is defined as “the quality of performance in a specific domain and the level of persistence when one meets adverse or negative experience” (Bandura 1994, p.74), was shown to moderate the effect of work-to-family conflict on occupational stress (Matsui et al. 1995). Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) demonstrated that the negative effect of work-to-family conflict is intensified when work or family roles are very important for one’s self-concept. Huynh et al. (2013) found that family and friend support moderated the relationship between work-family conflict and exhaustion, as well as the relationship between work-to-family conflict and cynicism, measured as the extent to which “one doubts the significance of their work” (p. 11). The same study also found a significant relationship between work-to-family conflict and organizational connectedness, defined as “the strong sense of belonging with other workers and the recipients of one’s service” (Huynh et al. 2013, p. 9). Overall, prior research consistently suggests a negative relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction. Thus, this leads to the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 1:

Work-to-family conflict will be negatively related to life satisfaction.

The Moderating Effect of Type of Employment

To my knowledge, no empirical study has tested whether type of employment moderates the association between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction. In light of this gap in the literature, and informed by the job demand-control model (Karasek 1979), this study explores the combined impacts of work-to-conflict and type of employment on life satisfaction. Karasek’s (1979) theory suggests that high levels of job control and job demand interact and negatively impact the work environment, which is then expected to impact family life negatively as a spillover effect.Footnote 1 This cycle leads to high conflict between work and family, conflict expected to affect work-life balance negatively. Prior research has consistently shown that high demand at work increases the risk of experiencing work-family conflict (Chung 2011; Fagan and Walthery 2011; Gronlund 2007), whereas the research on the influence of high levels of job control shows mixed results.Footnote 2 Some research has argued that high levels of job control at work improve the interaction of work and family life, but other studies concluded that high levels of job control have a negative impact on work-life balance (Fagan and Walthery 2011; Nordenmark et al. 2012). The latter effect can be due to the fact that a high level of job control at work requires the individual to be available at all times, which might negatively impact work-family balance (Nordenmark et al. 2012). Applying the job demand-control model to self-employed workers, prior research has consistently shown that self-employed have higher levels of job control and demand compared to employees (Hundley 2001; Stephan and Roesler 2010). However, due to the contradictory arguments regarding the effects of job control on work-life balance, there is no consistent finding as to whether self-employed workers are better or worse in terms of well-being and work-life balance.

While no prior research has empirically tested the moderating effect of type of employment on the relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction, some studies have suggested that this relationship might differ among self-employed workers. Overall, as Annink et al. (2016) pointed out, studies that have investigated the experience of work-to-family conflict among the self-employed are inconclusive. Most studies showed that the self-employed experience more work-to-family conflict than employees (Frone 2000; Nordenmark et al. 2012; Parasuraman and Simmers 2001), whereas a few other scholars found the opposite result (Craig et al. 2012; Prottas and Thompson 2006). Specifically, some researchers have suggested that certain characteristics of self-employment, such as flexibility in work schedule and working from home, may reduce work-to-family conflict (Georgellis and Wall 2000; Loscocco 1997; Stephens and Feldman 1997). Conversely, other scholars have found that self-employed workers might have higher work-to-family conflict compared to employees (Annink et al. 2016). One reason for this might be because self-employed workers have a higher burden due to having the main responsibility for their own professional survival (Greenhaus and Callanan 1994).

The relationship between type of employment and life satisfaction in general is also understudied, and the results are not consistent. Some studies found that self-employment was positively associated with both job and life satisfaction (Blanchower and Oswald 1998; Andersson 2008). On the other hand, a more recent study (Crum and Chen 2015), using data from the World Values Survey from 80 different countries, found that there is a significant positive relationship between being self-employed and both happiness and life satisfaction. This relationship, however, only existed for women in highly developed countries. In lesser developed countries, results suggested that self-employed men are significantly happier than men working for someone else. Some other studies have found that self-employment is positively associated with subjective well-being, but with some exceptions. For instance, Alesina et al. (2004) found a positive effect between self-employment and happiness, but only for wealthy individuals. In addition, Markussen et al. (2014) showed that self-employment is positively correlated with life satisfaction, but only in specific employment sectors such as the agriculture sector.

Overall, prior research suggests that self-employed workers have different levels of work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction than employees, which might be due to different working conditions and broader motivations for self-employment. These mixed findings cannot tell us about the direction of the moderating effect of type of employment. However, prior research leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Type of employment will moderate the relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction.

Data and Methods

Sample

This study uses data from the 2008 National Study of the Changing Workforce (NSCW) to address the proposed hypotheses. The 2008 NSCW survey is based on a questionnaire developed by the Families and Work Institute. Between November 2007 and April 2008, 3502 interviews with employed American adults were completed. Each interview took 50 min on average, and interviews were conducted by telephone using a computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) system. A random-digit dialing method was used to obtain a nationally representative sample of employed adults, with interviewers determining if a potential respondent was eligible for participation in the study at the time of the telephone call (Families and Work Institute 2008). There were several criteria for sample eligibility. The individual had i) “to work at a paid job or operated and income-producing business, ii) be 18 years or older, iii) to be employed in the civilian labor force, iv) to reside in the contiguous 48 states, and v) to live in a non-institutional residence- i.e., a household- with a telephone. If there was more than one eligible person in the household, one was randomly selected to be interviewed” (Families and Work Institute 2008, p. 3).

Of the total sample of 3502 interviewed adults (with an overall response rate of 54.6 % for potentially eligible households), “2,769 are wage or salaried workers who work for someone else, while 733 respondents work for themselves, including 255 business owners who employ others and 478 independent self-employed workers who do not employ anyone else” (Families and Work Institute 2008, p. 5.). This study focuses on workers who are between 18 and 64 years old. This restriction reduced the sample size to 3210 workers. There were six individuals who were missing information on life satisfaction. Deleting these missing cases reduced the sample size to 3204.

Measures

The first part of the study tests the association between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction. The second part of the study tests whether the association between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction is moderated by type of employment (self-employed versus employee).

Dependent Variable: Life Satisfaction

The measure for life satisfaction is adapted from Bjørnskov et al. (2010), and respondents are asked the following question: “All things considered, how do you feel about your life these days?” The answer categories range from 1 to 4, where 1 indicates “very satisfied” and 4 indicates “very dissatisfied.” This question is reverse coded so that higher scores indicate greater life satisfaction. The distribution of this variable is highly skewed; only 2 % of the sample reported being very dissatisfied. Therefore, those who report being very dissatisfied or somewhat dissatisfied are grouped into one category (coded 1), while those who report being somewhat satisfied or very satisfied remain in separate groups (coded 2 and 3, respectively). The recoded scale for life satisfaction thus ranges from 1 to 3.

Main Independent Variable: Work-To-Family Conflict

The main independent variable is work-to-family conflict. The measure for work-to-family conflict is adapted from some prior studies (Hill 2005; Voydanoff 2005). Respondents were asked to respond to the following questions: (a) “In the past 3 months, how often have you not had enough time for your family or other important people in your life because of your job?” (b) “In the past 3 months, how often has work kept you from doing as good a job at home as you could?” (c) “In the past 3 months, how often have you not had the energy to do things with your family or other important people in your life because of your job?” (d) “In the past 3 months, how often has your job kept you from concentrating on important things in your family or personal life?” (e) “In the past 3 months, how often have you not been in as good a mood as you would like to be at home because of your job?” Responses ranged from 1 = very often to 5 = never. The responses were first reverse coded, summed and then averaged to create an index, with higher scores indicating higher levels of work-to-family conflict. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86, showing high internal reliability.

Moderating Variable: Type of Employment

Type of employment is measured by asking the respondents for their employment status. Consistent with prior research (Prottas and Thompson 2006), self-employed workers are defined as those who are either independent and do not employ someone else or those who own a small business with fewer than 100 employees. On the other hand, waged and salaried workers are those who work for someone else. Thus, a dummy variable is created: 1 = business owners who employ others or independent self-employed workers who do not employ anyone, and 0 = waged or salaried employees who work for someone else.

Control Variables

Associations between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction not represent causal relationships. Therefore, it is crucial to account for background and contextual factors that are potentially related to life satisfaction (Angeles 2010; Cheung and Chan 2009; Easterlin 2003; Kaliterna et al. 2004; Lucas et al. 2003; Young 2006). Consistent with this argument and with prior studies, this study controls for the following variables: parenthood status, gender, log of gross annual family income (due to skewness), work hours, nonstandard work hours, relationship status, education, race, and age.

Parenthood status was coded as 1 for those who are the parents or guardians of any child of any age, including the respondent’s own children, stepchildren, adopted children, foster children, grandchildren, or others for whom the respondent is responsible and acts as a parent; and 0 = not being a parent. The gender of the respondent is coded as 1 = male and 0 = female. Annual household income was measured by asking the respondent’s and his or her spouse’s total income from all sources, before taxes, last year. This variable was logged due to skewness. Respondents’ work hours were measured by asking each respondent to report the number of usual hours worked per week. Nonstandard work hours was measured by asking respondents whether they worked a regular daytime schedule (coded 0) or any other shift that differs from the regular daytime schedule (coded 1). Relationship status was coded as 1 for those who are currently married and 0 otherwise. Age was measured in years. Education was measured by creating the following four dummy variables: high school graduate or less (reference category), some college, college degree, and postgraduate degree. Race was also measured by creating the following three dummy variables: those who are self-identified as White (reference category), those self-identified as Black, and those self-identified as another race.

Analytical Strategy

This study used Stata 13.0 statistical software to analyze the data, and employed multiple imputation to handle missing cases in the sample. The dependent variable, life satisfaction, is an ordered categorical variable. Therefore, for life satisfaction, this study uses ordered logistic regression. In the first step, the model tests the zero-order associations of work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction (Model 1). Thus, Model 1 only tests the bivariate relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction (without including any other variable- i.e., an unadjusted model). Model 2 adds the control variables to Model 1 (i.e., an adjusted model). This adjusted model (Model 2) tests Hypothesis 1, showing the association between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction, after taking the control variables into consideration. Model 3 adds the interaction term between work-to-family conflict and type of employment to Model 2. Model 3 tests Hypothesis 2, showing whether type of employment moderates the association between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction. At each step, the total variance in life satisfaction is reported by R2. This shows how much of the variance in life satisfaction is explained by each group of predictors.

For the missing data in our models, this study employed the multiple imputation method (Allison 2002). The imputation models included all the variables in the analyses. After multiple imputation analyses, only the six cases that were missing information on life satisfaction were deleted. This approach, where all cases are used for imputation, but then cases with imputed Y values (i.e., missing values for the dependent variable) are excluded from the analyses, is called multiple imputation, then deletion (MID). This method gives more accurate standard error estimates, and is therefore used to obtain more accurate results (von Hippel 2007). After dropping these six cases in life satisfaction scale, the final sample size was 3204.

Results

Descriptive Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the dependent variable, along with all the independent and control variables. The life satisfaction scale (ranging from 1 to 3) found an average score of 2.31, suggesting high life satisfaction. On the work-to-family conflict scale (1–5), the sample scored an average of 2.54. 19 % of the respondents are small business owners who employ others or independent self-employed workers who do not employ anyone. On average, the sample is 84 % White, 8 % Black, and 8 % of respondents identify as belonging to another race. On average, the respondents in the sample are 45 years of age, with about 61 % of the sample being married. Around 54 % of the sample has at least a bachelor’s degree, and 64 % of the respondents are parents. Around 48 % of the sample is male, and 52 % is female. On average, those in the sample work 41 h per week, and around 27 % of the respondents work nonstandard hours.

Ordered Logistic Regression Results

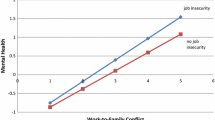

Ordered logistic regression results are used to test the predictors of life satisfaction. Table 2 shows the results. The results of the first model (Model 1) suggest that those who experience more work-to-family conflict have worse life satisfaction (b = −0.809, p < .001). This model explains 6 % of the variance. After adding the control variables in Model 2, the association between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction is still significant, and in the expected direction (b = −0.917, p < .001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Turning to the control variables, higher family income is associated with higher life satisfaction (b = 0.208, p < 0.001). Males report lower life satisfaction (b = −0.190, p < .01). Those who work longer hours report higher life satisfaction (b = 0.011, p < .001). Those who have higher than a bachelor’s degree report higher life satisfaction compared to those who have less than a high school degree (b = 0.278, p < .01), whereas older individuals report lower life satisfaction (b = −0.008, p < .05). R2 in Model 2 increases to 13 %. Model 3 tests the moderating effect of type of employment. The interaction term between work-to-family conflict and type of employment is added to the model. The significant interaction term (b = −0.260, p < .05) indicates that the negative association between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction is stronger for those workers who are self-employed. After adding this interaction term, R2 in Model 3 improves to 15 %. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is also supported.

Discussion

There is substantial literature on the effect of work-to-family conflict on well-being, job satisfaction, and life satisfaction (Allen et al. 2000; Bruck et al. 2002; Carlson et al. 2011; Frone 2000; Kinnunen and Mauno 1998; Netemeyer et al. 1996; Rupert et al. 2012; Wayne et al. 2004). However, only a few studies examine under what specific conditions work-to-family conflict impacts these outcomes, i.e., moderating factors such as gender, friend and family support, and supervisor support (Huynh et al. 2013; Ngo and Lui 1999; Ugwu and Agbo 2010). With this in mind, this study deepens our understanding of how work-to-family conflict is associated with life satisfaction by specifically testing the moderating effect of type of employment. These research questions are tested using data from 3204 workers from the 2008 National Study of the Changing Workforce (NSCW). As hypothesized, the results suggest that higher work-to-family conflict is associated with lower life satisfaction. Moreover, this study finds that the negative association between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction is stronger among self-employed workers.

This study has several strengths. To my knowledge, this is the first study that empirically tests the moderating effect of type of employment on the relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction, using an extensive dataset with rich measures on work characteristics. Given its findings, this study underscores the importance of examining the conditions under which work-to-family conflict is associated with life satisfaction, in this case type of employment. Overall, the results suggest a further need to distinguish between different types of employment while analyzing work-family balance among workers. With this in mind, this study adds to the literature by focusing on a rather neglected population: self-employed workers. The finding that the negative association between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction is stronger among self-employed workers might be due to the fact that self-employed workers have higher work-to-family conflict compared to traditional employees, which is supported in some prior studies (Frone 2000; Nordenmark et al. 2012; Parasuraman and Simmers 2001).

There are several limitations of this research. The main limitation of this study is that the current data has a cross-sectional design, which prevents inferring causality between variables. In the future, researchers may measure work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction at different points in time to demonstrate a causal relationship between the variables. Second, without longitudinal data, the long-term impact of work-to-family conflict on life satisfaction cannot be explored. Third, all the predictors included in the analyses are individual-level variables, so the current analyses cannot disentangle any multi-level variations. As stated in Annink et al. (2016), there has been some support from prior research that the level of work-to-family conflict varies across some countries, mainly due to differences in state-level support (such as family leave policies and childcare availability) (Abendroth and Den Dulk 2011; Allen et al. 2015; Annink et al. 2015b; Ruppanner 2013; Stier et al. 2012). Despite this, as noted in the same study (Annink et al. 2016), there has been very little attention to the impact of wider societal and institutional contexts in work-family literature (Drobnicˇ and Le’on 2014). Therefore, it is important that future scholars consider both individual-level and country-level variables while studying work-family dynamics, given available datasets with rich measures. Altogether, such future work will build on prior work, including the present study, to strengthen our knowledge about the relationships between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction.

Some evidence from prior research also suggests that work-to-family conflict might operate differentially across occupational groups (e.g., Burke and Greenglass 2001; Cinamon and Rich 2005). This might lead to differential effects on life satisfaction. Thus, further research can explore in more detail the mechanisms and conditions under which work-family conflict might impact life satisfaction across different occupations. Self-employed workers can be quite a heterogeneous group, so future research should take this fact into account. For instance, some prior research found significant differences between independent contractors and small business owners (Prottas and Thompson 2006), and between opportunity-driven versus necessity-driven self-employment (Binder and Coad 2013).Footnote 3 A few studies found that women enter self-employment to balance work and family responsibilities, whereas men prefer self-employment to increase their earnings (Hundley 2000; Boden 1999; Matthews and Moser 1996).Footnote 4 More broadly, prior research concluded that financially, self-employment is more advantageous among high-skilled workers whereas wage/salary employment is a more financially rewarding option for most low-skilled workers (Lofstrom 2013).Self-employment might also bring many advantages for parents, especially as a strategy to balance work and family responsibilities due to self-employment’s flexibility and control over work hours, work schedule, and effort (Craig et al. 2012; Haddock et al. 2006). Therefore, it would be beneficial for future research to explore the variations within this group of self-employed workers to understand better the overall impact of type of employment in work-family literature. Such future research can help work-family scholars better understand the relationship between work-to-family conflict and life satisfaction, and the vital role of type of employment in studying work-family dynamics.

Notes

Spillover refers to “the transfer of mood, energy, and skills from one sphere to the other” (Grosswald 2015, p.32). Negative work-family spillover occurs “when strains and conflicts in one domain (work or family) negatively affect one’s mood and behavior in the other domain” (Roehling et al. 2005, p.841).

Job control is defined as “having authority over job performance that allows the employee to decide how and when a job task is completed, as well as having the control over the use of the employee’s initiative and skills on the job” (Nordenmark et al. 2012, p. 2). Job demands refer to “factors that are related to time pressure, mental load and coordination responsibilities, such as work-hours, working at a short notice, job insecurity and being a supervisor” (Nordenmark et al. 2012, p. 2; Annink et al. 2016, p. 574).

Specifically, results suggest higher job pressure associated with owning a business among small business owners and lower levels of job pressure among independent contractors (Prottas and Thompson 2006). Given these differences, future research can benefit from distinguishing between these two categories of self-employment. Another study by Binder and Coad (2013) found that only those who move from regular employment into self-employment experience an increase in life satisfaction (i.e., opportunity-driven self-employment) whereas those who move from unemployment to self-employment (i.e., necessity-driven self-employment) are not more satisfied than their counterparts who move from unemployment to regular employment. This suggests the need to distinguish between opportunity-driven and necessity-driven self-employment, as argued in some recent research (Annink et al. 2016).

This might help explain why some research found that self-employed women experience a higher level of work-family balance (compared to traditionally employed women), whereas there was no difference in work-family balance between self-employed men and traditionally employed men (Nordenmark et al. 2012).

References

Abendroth, A. K., & Den Dulk, L. (2011). Support for the work-life balance in Europe: the impact of state, workplace and family support on work-life balance satisfaction. Work, Employment and Society, 25(2), 234–256.

Adams, G. A., King, L. A., & King, D. W. (1996). Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work–family conflict with job and life satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 411–420.

Alesina, A., Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: are Europeans and Americans different? Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2009–2042.

Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to- family conflict: a review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(2), 278–308.

Allen, T. D., French, K. A., Dumani, S., & Shockley, K. M. (2015). Meta-analysis of work–family conflict mean differences: does national context matter? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 90, 90–100.

Allison, P. D. (2002). Missing data. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Amstad, F. T., Meier, L. L., Fasel, U., Elfering, A., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of work– family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching- domain relations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16, 151–169.

Andersson, P. (2008). Happiness and health: well-being among the self-employed. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(1), 213–236.

Angeles, L. (2010). Children and life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(4), 523–538.

Annink, A., Den Dulk, L., & Steijn, B. (2015b). Work–family state support for the self-employed across Europe. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 4(2), 187–208.

Annink, A., Den Dulk, L., & Steijn, A. J. (2016). Work-to-family conflict among employees and the self-employed across Europe. Social Indicators Research, 126, 571–593.

Aryee, S., Luk, V., Leung, A., & Lo, S. (1999). Role stressors, interrole conflict, and well-being: the moderating influence of spousal support and coping behaviors among employed parents in Hong Kong. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(2), 259–278.

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71–81). New York: Academic Press.

Barnett, R. C., & Gareis, K. C. (2006). Role theory perspectives on work and family. In M. Pitt-Catsouphes, E. E. Kossek, & S. Sweet (Eds.), The work and family handbook: multi-disciplinary perspectives and approaches (pp. 209–221). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bellavia, G. M., & Frone, M. R. (2005). Work-to-family conflict. In J. Barling, E. K. Kelloway, & M. R. Frone (Eds.), Handbook of work stress (pp. 113–147). London: Sage.

Binder, M., & Coad, A. (2013). Life satisfaction and self-employment: a matching approach. Small Business Economics, 40(4), 1009–1033.

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. A. V. (2010). Formal institutions and subjective well-being: revisiting the cross-country evidence. European Journal of Political Economy, 26, 412–430.

Blanchower, D., & Oswald, A. (1998). What makes an entrepreneur? Journal of Labor Economics, 16(1), 26–60.

Boden, R. J. (1999). Flexible working hours, family responsibilities, and female self- employment: gender differences in self-employment selection. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 58(1), 71–83.

Bruck, C. S., Allen, T. D., & Spector, P. E. (2002). The relation between work-to-family conflict and job satisfaction: a finer-grained analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(3), 336–353.

Burke, R. J., & Greenglass, E. R. (2001). Hospital restructuring, work-to-family conflict and psychological burnout among nursing staff. Psychology and Health, 25(6), 583–594.

Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work-to-family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 169–198.

Carlson, D. S., Grzywacz, J. G., Ferguson, M., Hunter, E. M., Clinch, C. R., & Arcury, T. A. (2011). Health and turnover of working mothers after childbirth via the work–family interface: an analysis across time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 1045–1054.

Cheung, H., & Chan, A. W. H. (2009). The effect of education on life satisfaction across countries. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 55(1), 124–136.

Chung, H. (2011). Work-family conflict across 28 European countries: a multi-level approach. In S. Drobnicˇ & A. M. Guıllen (Eds.), Work-life balance in Europe-the role of job quality (pp. 42–68). Chippenham and Eastbourne: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cinamon, R. G., & Rich, Y. (2005). Work-to-family conflict among female teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21, 365–378.

Craig, L., Powell, A., & Cortis, N. (2012). Self-employment, work–family time and the gender division of labour. Work, Employment and Society, 26(5), 715–734.

Crum, M., & Chen, Y. (2015). Self-employment and subjective well-being: a multi-country analysis. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 19, 15–26.

Drobnicˇ, S., & Le’on, M. (2014). Agency freedom for worklife balance in Germany and Spain. In B. Hobson (Ed.), Worklife balance. The agency and capabilities gap (pp. 126–150). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (2003). Explaining happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100, 11176–11183.

Fagan, C., & Walthery, P. (2011). Job quality and the perceived work-life balance fit between work hours and personal commitments: A comparison of parents and older workers in Europe. In S. Drobnic & A. M. Guille’n (Eds.), Work-life balance in Europe-The role of job quality (pp. 69–94). Chippenham and Eastbourne: Palgrave Macmillan.

Families and Work Institute (2008). National study of the changing workforce guide to public use files. New York, NY: Families and Work Institute.

Frone, M. R. (2000). Work-to-family conflict and employee psychiatric disorders: the National Comorbidity survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(6), 888–895.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 65–78.

George, J. M., & Jones, G. R. (1996). The experience of work and turnover intentions: interactive effects of value attainment, job satisfaction, and positive mood. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 318–325.

Georgellis, Y., & Wall, H. J. (2000). Who are the self-employed? Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, November/December, pp. 15–23.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10, 76–88.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Callanan, G. A. (1994). Career management. Ft. Worth, TX: The Dryden Press.

Gronlund, A. (2007). More control, less conflict? Job demand-control, gender and work-family conflict. Gender, Work and Organization, 14(5), 476–497.

Grosswald, B. (2015). Shift work and negative work-to-family spillover. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 30(4), 31–56.

Haddock, S. A., Zimmerman, T. S., Lyness, K. P., & Ziemba, S. J. (2006). Practice of dual earner couples successfully balancing work and family. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 27(2), 207–234.

Hill, E. J. (2005). Work-family facilitation and conflict, working fathers and mothers, work-family stressors and support. Journal of Family Issues, 26(6), 793–819.

Hundley, G. (2000). Male/female earnings differences in self-employment: the effects of marriage, children, and the household division of labor. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 54(1), 95–114.

Hundley, G. (2001). Why and when are the self-employed more satisfied with their work? Industrial Relations, 40, 293–316.

Huynh, J. Y., Xanthopoulou, D., & Winefield, A. H. (2013). Social support moderates the impact of demands on burnout and organizational connectedness: a two-wave study of volunteer firefighters. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(1), 9–15.

Kaliterna, L. L., Prizmic, L. Z., & Zganec, N. (2004). Quality of life, life satisfaction and happiness in shift-and non-shiftworkers. Revista de Saúde Pública, 38, 3–10.

Karasek, R. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285–308.

Kinnunen, U., & Mauno, S. (1998). Antecedents and outcomes of work-to-family conflict among employed women and men in Finnland. Human Relations, 51(2), 157–177.

Kossek, E. E., & Ozeki, C. (1998). Work-to-family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfaction relationship: a review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 139–149.

Lofstrom, M. (2013). Does self-employment increase the Does self-employment increase the economic well-being -skilled workers? Small Business Economics, 40(4), 933–952.

Loscocco, K. A. (1997). Work-family linkages among self-employed women and men. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50, 204–226.

Lucas, R. E., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2003). Reexamining adaptation and the set point model of happiness: reactions to changes in marital status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 527–539.

Markussen, T., Fibaek, M., Tarp, F., & Nguyen Do Anh, T. (2014). Self-employment and subjective well-being in rural Vietnam. WIDER Working Paper, 2014/108.

Matsui, T., Ohsawa, T., & Onglotco, M. (1995). Work-to-family conflict and the stress-buffering effects of husband support and coping behavior among Japanese married working women. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 47, 178–192.

Matthews, C. H., & Moser, S. B. (1996). A longitudinal investigation of the impact of family background and gender on interest in small firm ownership. Journal of Small Business Management, 34(2), 29–43.

Michel, J. S., & Hargis, M. B. (2008). Linking mechanisms of work-to-family conflict and segmentation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73, 509–522.

Minnotte, K. L., Minnotte, M. C., & Pedersen, D. E. (2013). Marital satisfaction among dual–earner couples: gender ideologies and family–to–work conflict. Family Relations, 62(4), 686–698.

Minnotte, K. L., Minnotte, M. C., & Bonstrom, J. (2015). Work–family conflicts and marital satisfaction among U.S. workers: does stress amplification matter? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36, 21–33.

Nelson, C. C., Li, Y., Sorensen, G., & Berkman, L. F. (2012). Assessing the relationship between work- family conflict and smoking. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1767–1772.

Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., & McMurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 400–410.

Ngo, H. Y., & Lui, S. Y. (1999). Gender differences in outcomes of work-to-family conflict: the case of Hong Kong managers. Sociological Focus, 32, 303–316.

Nordenmark, M., Vinberg, S., & Strandh, M. (2012). Job control and demands, work–life balance and wellbeing among self-employed men and women in Europe. Vulnerable Groups and Inclusion. doi:10.3402/vgi.v3i0.18896.

Parasuraman, S., & Simmers, C. A. (2001). Type of employment, work–family conflict and well-being: a comparative study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 551–568.

Perrewe, P. L., Hochwarter, W. A., & Kiewitz, C. (1999). Value attainment: an explanation for the negative effects of work-to-family conflict on job and life satisfaction. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 4, 318–326.

Prottas, D. J., & Thompson, C. A. (2006). Stress, satisfaction, and the work-family interface: a comparison of self-employed business owners, independents, and organizational employees. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11, 366–378.

Rice, R. W., Frone, M. R., & McFarlin, D. B. (1992). Work-nonwork conflict and the perceived quality of life. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 155–168.

Roehling, P., Jarvis, L., & Swope, S. (2005). Variations in negative work-family spillover among white, black, and Hispanic American men and women. Journal of Family Issues, 26, 840–865.

Rupert, P. A., Stevanovic, P., Hartman, E. R. T., Bryant, F. B., & Miller, A. (2012). Predicting work– family conflict and life satisfaction among professional psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(4), 341.

Ruppanner, L. (2013). Conflict between work and family: an investigation of four policy measures. Social Indicators Research, 10(1), 327–346.

Stephan, U., & Roesler, U. (2010). Health of entrepreneurs vs. employees in a national representative sample. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(3), 717–738.

Stephens, G. K., & Feldman, D. C. (1997). A motivational approach for understanding career versus personal life investments. In G. R. Ferris (Ed.), Research in personnel and human resource management (pp. 333–378). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Stier, H., Lewin-Epstein, N., & Braun, M. (2012). Work–family conflict in comparative perspective: the role of social policies. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30(3), 265–279.

Ugwu, L. I., & Agbo, A. A. (2010). Exploring the role of social support, work/family conflict, and gender-role ideology on burnout in a Nigerian sample. African Journal for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, 13(1), 238–250.

van Steenbergen, E. F., & Ellemers, N. (2009). Is managing the work–family interface worthwhile? Benefits for employee health and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(5), 617–642.

von Hippel, P. T. (2007). Regression with missing Ys: an improved strategy for analyzing multiply imputed data. Sociological Methodology, 37, 83–117.

Voydanoff, P. (2005). Work demands and work-to-family and family-to-work conflict: direct and indirect relationships. Journal of Family Issues, 26, 707–726.

Voydanoff, P. (2007). Work, family and community: exploring interconnections. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Wayne, J. H., Musisca, N., & Fleeson, W. (2004). Considering the role of personality in the work-family experience: relationships of the big five to work-family conflict and facilitation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(1), 108–130.

Wu, M., Chang, C.-C., & Zhuang, W.-L. (2010). Relationship of work-family conflict with business and marriage outcomes in Taiwanese copreneurial women. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(5), 742–753.

Young, K. W. (2006). Social support and life satisfaction. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 10, 155–164.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yucel, D. Work-To-Family Conflict and Life Satisfaction: the Moderating Role of Type of Employment. Applied Research Quality Life 12, 577–591 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-016-9477-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-016-9477-4