Abstract

Previous studies have shown that strong parent-youth relationships serve as a protective factor inhibiting early alcohol use onset among youth, while parental alcohol use as a risk factor. However, little is known about the moderating effect of parental alcohol use on the relationship between parent-youth relationships and youth alcohol use. Using a nationally representative sample of 2,667 junior high school students entering eighth grade (aged 14 to 15) in Taiwan, this study examined the moderating role of parent use of alcohol on the relationship between parent-youth relationships and youth alcohol use. Results show that parent-youth relationship only remains a protective factor for youths whose parents do not drink alcohol; parent-youth relationship increases the likelihood of youth alcohol use if the parents use alcohol. Results suggest that parents and practitioners aiming to prevent early alcohol use onset among junior high school students should be aware of the potential influence of parental alcohol use behaviors and educate youths to assess their health behaviors regardless of their parents’ alcohol use behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Alcohol use among junior high school students in Taiwan is extremely high. According to a recent national report on youths’ health behavior (Health Promotion Administration, 2022), 49.7% of enrolled junior high school students in Taiwan have drank alcohol, and 14.1% have drank in the past 30 days. The prevalence of lifetime alcohol use among junior high school students (49.7%) is significantly higher than cigarette smoking (12.9%), the second most prevalent type of substance use among the same population (Health Promotion Administration, 2022). The prevalence of alcohol use among Taiwanese junior high students is also higher than that in the USA, where in 2019, about 24.6% of youth ages 14 to 15 reported having had at least one drink in their lifetime. This could be because, in Taiwan, alcohol—displayed on shelves and sold openly in grocery stores and convenience stores—can be easily accessed compared to other types of controlled substances; youths can buy alcohol at a low price with an identification showing the buyer is 18 or older. Youth who start using alcohol at an early age are more likely to experience long-term health and social issues and tend to use alcohol to cope with stress from violence, mental distress, or a sense of loneliness (Colder et al., 2002; Englund et al., 2008). Alcohol onset in early adolescence predicts alcohol dependence in later adolescence and can extend psychological symptoms from late adolescence to early adulthood (Brook et al., 2010).

Numerous studies have shown parents’ influence on adolescent alcohol involvement. While children who receive supportive care and company from their parents are less likely to seek alcohol as a pastime or to use alcohol to relieve anxiety or mental distress, children who grow up with alcohol-involved parents are more likely to start using alcohol at an early age (Brook et al., 2010). In Taiwan, 64.7% of junior high school students who have used alcohol acquired that alcohol from parents, siblings, or other family members, indicating more attention should be paid to understanding parents’ influence on their young adolescents’ access to and use of alcohol (Health Promotion Administration, 2022). Given parents’ protective and risk effects, the present study focuses on the interactive effect of parent-youth relationships and parental alcohol use, examining how parent-youth relationships and parental alcohol use, when taken together, impact adolescent alcohol use.

The Protective Effect of Parent-Youth Relationship for Early Adolescents’ Alcohol Use

Early adolescence is a time youths develop their identity and independence from their parents. Studies have shown that a youth’s relationship with parents in early adolescence can be a protective factor that thwarts youth from substance use of alcohol in later developmental stages (Brook et al., 2009; Skeer et al., 2011). Some researchers have highlighted the impact of parental control on reducing adolescents’ involvement in underage alcohol use, showing that parents with clear and strict alcohol-specific rules postpone their children’s drinking initiation and lower the intensity of subsequent adolescent alcohol use (Mares et al., 2012; Van Der Vorst et al., 2005, 2010; Yu, 2003). Other researchers have emphasized relationship quality rather than behavioral control. Stattin and Kerr (2000) argued that parental monitoring (i.e., tracking and surveillance) is limited to cases in which children are willing to disclose their school life with parents, whereas close and affectively positive parent-youth relationships increase the potential for better parent-youth communication. As autonomy increases at the junior high school level, past and continuing interactions with parents can result in the internalization among youths of a sense of personal efficacy and self-esteem, thereby influencing their unsupervised interactions with peers (Burk et al., 2012; Stattin & Kerr, 2000). This will expand the opportunity for greater parental monitoring of the youth’s behaviors when the parents are absent (Stattin & Kerr, 2000).

Studies of neurocognitive development have also documented the linkage between responsive parenting, cohesive family relationships, and the development of higher-order behavioral control capacities contributing to moderating the rewarding effect of risk behavior and risk-taking peers (Qu et al., 2015; Taber-Thomas & Pérez-Edgar, 2015). Positive parent-child relationships featuring open communication and closeness can reduce substance use in middle and high school youths (Tharp & Noonan, 2012). Parent-child bonding in early and mid-adolescence can reduce personality attributes (e.g., rebellion, impulsivity) that cause vulnerability when the young person reaches their early twenties—which, in turn, can reduce the selection of drug-using peers/partners and the development of substance use disorders (Brook et al., 2009). Youth who perceive their parents as loving and caring are more likely to foster friendships and social niches that are advantageous to achievement, which are seen as protective factors preventing risk-taking behaviors; in contrast, youth alienated from their parents are more likely to be attracted to risk-taking peers and risky behaviors (Kogan, 2017). In a recent study, Rusby and colleagues (Rusby et al., 2018) narrowed the investigation scope and confirmed that positive parent-child relationships do reduce alcohol use, binge drinking, and marijuana use onset in early adolescence.

Relationships Between Parental Alcohol Use and Youth Alcohol Use

Studies have shown that maternal and paternal drinking were strong predictors of early adolescence alcohol use, and the impact may last to late adolescence and adulthood (Alati et al., 2014; Brody et al., 2000; Brook et al., 2010; Rusby et al., 2018). Genetic studies attributed such relationships to a substantial genetic component of alcoholism. While alcohol tolerance results from drinking substantial amounts of alcohol over long periods of time, alcohol intolerance (i.e., immediate unpleasant reactions after drinking alcohol such as stuffy nose and skin flushing) is caused by genetically driven problems with alcohol metabolism associated with the ability of the body to break down alcohol efficiently (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, 2015). As such, children of heavy drinkers may be more predisposed to or more susceptible to alcoholism as a result of these hereditary factors. Other than genetic factors, children who grow up in households where alcohol use is prevalent may also have greater access to alcohol and be more likely to experiment with it at an earlier age. Such relationships between youth proclivities to alcohol use can be attributed to the modeling effect and the internalization of alcohol-use norms learned from adults around them, which was suggested by social learning theory (Bandura & Walters, 1963). When a parent uses alcohol heavily or problematically, it may normalize or encourage that behavior in the child (Brody et al., 2000; White et al., 2000).

The Combined Effect of Parental Alcohol Use and Parent-Youth Relationship

A few studies have examined the combined effect of parental alcohol use and parent-youth relationships on youth alcohol use or, more specifically, how parental alcohol use moderates the protective effect of parent-youth relationships. Andrews and colleagues (Andrews et al., 1997) tested the impact of parent-youth relationships on youths’ alcohol, cigarette, and tobacco use with 657 youths and their parents, controlling for age, gender, and father or mother use on their alcohol use. Interactive effects were found, with the father’s alcohol use and the child’s relationship with their father increasing alcohol use among younger girls and older boys. They concluded that parent-youth relationships were not always protective, and caution should be applied in assuming that good relationships with a parent always serve as a protective factor (Andrews et al., 1997). The above study provided insights into the moderating effect of parental alcohol use on adolescent alcohol use. Yet, the results were based on a convenient sample whose parents were more educated than average and tended to have more liberal attitudes toward their children’s substance use.

More recently, studies showed that while the parents’ alcohol-related problems increased drinking and alcohol-related problems in adolescents, they simultaneously increased the parents’ communication about alcohol with children, which in turn counteracted adolescent drinking and alcohol-related problems (Brincks et al., 2022; Mares et al., 2012). Alcohol misuse histories may raise a parent’s consciousness about the effect of alcohol use and urge them to discuss the negative consequences of alcohol use with the youths. Researchers concluded that alcohol-specific communication (i.e., verbal communication with which parents express their thoughts, rules, and concerns about alcohol to their children) serves as an intervention that moderates the relationship between parental alcohol-related problems and excessive adolescent drinking and alcohol-related problems (Mares et al., 2011). Once again, however, results were not based on nationally representative data from the general population, thus limiting the generalizability of the results.

The Current Study

Given limited evidence on the moderating effect of parental alcohol use on the relationship between parent-youth relationships and an early onset of youth alcohol use, the current study seeks to address the research gap. A national study on general school students was launched to investigate the influence of parent-related factors on youth’s early onset of alcohol use. The research question leading the study is: How do parent-youth relationships and parental alcohol use affect early youth alcohol use onset? The social learning theory and social control theory guided the study. Social control theorists posit that strong social bonds, such as attachment to family, deter individuals from engaging in deviant behaviors like alcohol abuse (Hirschi, 2015). Social learning theorists tell us that individuals learn behaviors, including alcohol use, through observation, imitation, and reinforcement in their social environment from the people they value (Bandura & Walters, 1963). Taken together, these theories suggest that a strong parent-youth relationship (characterized by intimacy with parents) may serve as a protective factor, deterring youths from alcohol use when parents are not exhibiting those behaviors. Conversely, parental alcohol use may compromise the protective effect of the parent-youth relationship by inadvertently contributing to social learning patterns of alcohol use.

Based on the literature and the theories, the authors generated three hypotheses: (1) Youth with better parent-youth relationships are less likely to use alcohol at an early age; (2) Youth of parents who use alcohol themselves are more likely to use alcohol at an early age; (3) Youth whose parent-youth relationships are strong are more likely to use alcohol at an early age if the parents use alcohol. Figure 1 shows the research model illustrating the moderating effect of parental alcohol use on the relationship between parent-youth relationships and an early onset of youth alcohol use. To our knowledge, this study is among the first studies to examine the moderating role of parental alcohol use on parent-youth relationships. In addition, the study is the first to examine the relationships with a sample of Asian cultural backgrounds. Most extant studies in this area have been based on Western samples (e.g., Brincks et al., 2022 on Hispanic youths; Mares et al., 2012 on Dutch youths).

Methodology

Sampling

This study is the third wave of a nationwide longitudinal study on children’s and adolescents’ family and social experiences (LSCAFSE) conducted in 2018 in Taiwan. The sample comprised 2,667 junior high school students in eighth grade, aged 14 to 15 years old. The students were first invited and participated in the study with their parents or guardians’ and their own consent in 2014 when they were enrolled in one of the proportionately stratified list of primary schools pulled from all counties and cities in Taiwan (Shen et al., 2019).

Data Collection

Before administering the survey, the research team contacted the students to provide them and their parents with a letter explaining the study’s purpose and the study’s voluntary, anonymous, and confidential nature. Students and parents who agreed to participate in the study returned an informed consent signature. The research team then scheduled sessions to distribute self-reporting paper-and-pen study questionnaires and acquire responses from those students who themselves and their parents agreed for them to participate in the study. Depending on the school’s schedule, group sessions were scheduled during or after regular class hours. All student participants received stationery as a reimbursement for their time. The study received IRB approval from the Research Ethics Committee of National Taiwan University Hospital.

Measures

The questionnaire contained measures related to demographics, family and peer relationships, parental and youth alcohol use, and health behaviors. The measures were selected by a team of health, child welfare, and family researchers and approved by IRB. Before the measures were administered to participants, seven experts, including four child development scholars, one sociologist, one clinical social worker, and one statistician, reviewed the measures to ensure their content validity (Shen et al., 2019). The authors also conducted a pilot study to test the measures’ reliability and validity—having modified some measures to incorporate recommendations from the expert panel and findings from the internal consistency and principal component analyses of data collected during the pilot phase. Psychometrics of measures was calculated after every wave of data collection. The measures used in the current study are presented below.

Parental Alcohol Use

The student participants were asked two questions on father and mother’s alcohol use: “Does your father often drink alcohol?” and “Does your mother often drink alcohol?” (0 = No, 1 = Yes). The scores for both questions were then added as the parental alcohol use score.

Parent-Youth Relationships

Parent-youth relationships were measured by the parental relationship quality scale that has been tested on a randomized sample of Taiwanese students (Shen, 2009). The scale consisted of four items, with two regarding the father and two regarding the mother. The questions were “I have a good relationship with my father” (mother) and “My father (mother) is my role model.” Participants were provided with a 5-point scale (from 1 = never to 5 = always) to answer each item. A total score was calculated by summing each response of these four items, ranging from 4 to 20. Higher scores indicated better parent-youth relationships. The internal consistency reliability of the scale was 0.75, demonstrating good internal reliability in this study.

Youth Alcohol Use

Participants were asked if they had ever drank alcohol with response options of yes or no (1 = Yes; 0 = No).

Control Variables

The control variables in the model included gender, academic achievement, and alcohol-involved peer affiliation. Literature on adolescent alcohol use behaviors has shown that early onset of alcohol use was associated with male gender (Adolfsen et al., 2014; Rose et al., 2001), lower academic performance (Patte et al., 2017), and affiliation with alcohol-using peers (Leung et al., 2014; Mundt, 2011; Trucco et al., 2011). Gender was measured by a binomial question asking the respondents’ gender (1 = male; 0 = female). Academic performance was measured by a question: “What is the average grade you received in the past semester?” (under 60 = 1; 60 to 69 = 2; 70 to 79 = 3; 80 to 89 = 4; 90 or above = 5). Finally, the researchers asked the respondents if their friends usually drink alcohol with response options of yes or no.

Data Procedures

The study used SPSS version 28 to perform statistical analysis. First, a descriptive analysis was done to determine the distribution of youth alcohol use, gender, peer alcohol use, academic performance, parental alcohol use, and parent-youth relationships. Second, t-test and chi-square analyses were done to test the association between parental alcohol use and youth alcohol use and the association between parent-youth relationships and youth alcohol use. Finally, a hierarchical logistic regression analysis was done examining the effect of the interaction of parental alcohol use and parent-youth relationship on youth alcohol use. The study data are available only to the research team, as stated in the IRB protocol.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

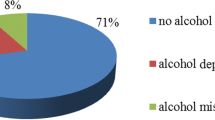

Approximately one out of four (28%) youths have drank alcohol. The gender ratio for the participants was approximately 1 to 1 (males = 51%; females = 49%). Only 4% of the youths had friends that usually drank. Nine percent of the participants reported that their father often drank, and 2% said that their mother often drank. Overall, the mean score of parental alcohol use was 0.1, ranging from 0 to 2 (S.D. = 0.33). The mean score of parent-youth relationships was 15.21, ranging from 4 to 20 (S.D. = 3.61) (see Table 1).

Youth Alcohol Use and Correlates

According to the results of bivariate analyses, the likelihood of alcohol use does not differ by gender but is different for youths with varying levels of academic performance. Better academic performance is associated with a lower likelihood of alcohol use (t = 6.25, p < 0.000). The existence of alcohol-involved friends is also related to more likelihood of youth alcohol use (X2 = 60.15, p < 0.000).

Youth alcohol use is also associated with parental alcohol use and parent-youth relationships. Higher levels of parental alcohol use related to more likelihood of youth alcohol use (t = − 4.818, p < 0.000) and better parent-youth relationship related to less likelihood of youth alcohol use (t = 6.24, p < 0.000) (see Table 2).

Effects of Parental Alcohol Use and Parent-Youth Relationships on Youth Alcohol Use

Table 3 illustrates the effects of parental alcohol use and parent-youth relationships on youth alcohol use, controlling for gender, academic performance, and peer alcohol use. Results show that parental alcohol use significantly increased the likelihood of youth alcohol use for this sample population. One additional point of parental alcohol use increased the likelihood of youth alcohol use by 68% (OR = 1.68, p < 0.000). On the other hand, the parent-youth relationship significantly reduced the likelihood of youth alcohol use (OR = 0.95, p < 0.000) (see Table 3, Regression 2).

Regarding the interaction terms of parental alcohol use and parent-youth relationships, results show that parental alcohol use moderated the protective effect of the parent-youth relationship on parental alcohol use. For youths whose parents used alcohol, the protective effect of parent-youth relationships was eliminated, and parent-youth relationships even became risk factors. In this scenario, higher levels of parent-youth relationships predicted a higher likelihood of alcohol use (OR = 1.11, p < 0.000) (see Table 3, Regression 3).

Discussion

The results revealed how family and school factors predict the early onset of alcohol use among Taiwanese junior high school students entering eighth grade. Parental alcohol use and peer alcohol use increase the likelihood of early alcohol use, while academic performance and parent-youth relationships protect the youths from drinking at an early age. The result that parental alcohol use increased youth alcohol use supports the first hypothesis: Youth of parents who use alcohol themselves are more likely to use alcohol at an early age (Hypothesis 1). Past studies on adolescents in Western countries have shown that parental alcohol use is associated with the early onset of alcohol use (Alati et al., 2014; Brody et al., 2000; Brook et al., 2010; Rusby et al., 2018). The present finding adds to the literature by showing a same pattern among a nationally representative Asian youth sample.

The results also support the second hypothesis: Youth with better parent-youth relationships are less likely to use alcohol at an early age (Hypothesis 2). Findings indicate that a positive parent-youth relationship can protect youth from an early onset of alcohol use, regardless of the effect of parental alcohol use. That is, for both children of parents who use drugs and children of parents who do not use drugs in Taiwan, a better parent-youth relationship tends to reduce the possibility that the child starts drinking alcohol at an early age. This finding contributes to and supports the literature on the protective role of parent-youth relationships (Brook et al., 2009; Rusby et al., 2018; Skeer et al., 2011). Furthermore, the finding confirms the protective role of parent-youth relationships in restraining the youths from using alcohol demonstrated in Western-based studies. Even given the fact that alcohol is the most accessible controlled substance in Taiwan, the protective effect remained even when alcohol was available and visible in the household (i.e., the parents often use alcohol themselves). This result resonates with neurocognitive studies that have shown that responsive parenting and cohesive family relationships help children develop higher-order behavioral control capacities that prevent them from conducting risk behaviors with immediate rewards (Qu et al., 2015; Taber-Thomas & Pérez-Edgar, 2015).

Finally, the result supports Hypothesis 3: Youth whose parent-youth relationships are strong are more likely to use alcohol at an early age if the parents use alcohol. For youth whose parents use alcohol, closer relationships with their parents lead to an increased likelihood of early alcohol use onset. Explanations for the result could be that youth who are closer to their parents are more likely to model their parents’ health behaviors and that alcohol-involved parents are more likely to carry out parenting behaviors that encourage their children’s alcohol consumption. The finding expands the literature by showing the interacting effect of parental alcohol use and parent-youth relationship, highlighting the vulnerability of children living in loving families where the parents drink.

Overall, our model shows that the effect of the parent-child relationship is two-fold. It serves as a social bond that keeps youths from drinking at an early age while also strengthening youths’ modeling of their parents, including the parents’ drinking behaviors. The findings suggest that while reinforcing the parent-youth relationship is a way to reduce the risk of early onset of youth alcohol use, it can lead to counteractive effects, pushing the youth to recognize and model their parents’ drinking behaviors, resulting in early alcohol use. The degree to which the impact of parental alcohol use or parent-youth relationships is stronger needs to be further explored for the purpose of developing intervention strategies and public policies. Also, the parent’s attitudes and parent-youth conversations on alcohol use may influence the consequences of parent-youth intimacy (Brincks et al., 2022; Mares et al., 2011; Trucco, 2020; Yap et al., 2017). These aspects of parent-youth relationships must be further explored and confirmed in future research.

Limitations

This study has limitations regardless of its strengths. The primary limitation of the study is that the original survey did not address the exact time the participants first used alcohol. Thus, the authors could not confirm the temporal precedence of parent-related factors relative to the participants’ alcohol onset. It was unclear if the youths first used alcohol after their parents used it. Future studies should use longitudinal data to confirm the causal relationship between parental alcohol use and youth alcohol use. Another limitation was that many items in the survey were significantly shortened to accommodate the limited attention spans of youths; this was needed, given the large number of variables in the survey that was administered to a nationwide randomized sample of youths. It is recognized that the truncated nature of some measures used in the study might not have measured the concepts of interest as delicately as scales and, in turn, this may have limited the findings. For example, it can be that only parental alcohol use that reaches a certain degree of severity counteracts the protective effect of parent-youth relationships. Future research could refine the measures to better assess for how parental alcohol use histories’ impact differs when controlling for use patterns and severity. Lastly, all data were self-reported by youths, raising the risk of self-report bias, especially for often-stigmatized factors such as parental alcohol use.

Implications

The study’s findings highlight the critical role of parents in youth alcohol use and suggest several potential areas in which prevention or treatment interventions may be effective. First, parents and practitioners aiming to prevent early alcohol use onset among youths should work on enhancing parent-youth relationships; for youths in their early adolescence, attention and positive interaction with parents are overarching protection for them to defer from deviant or risk-taking behaviors. Also, the results suggest that when boosting parent-youth relationships, practitioners should endeavor to raise parents’ awareness of their alcohol use behaviors (Brincks et al., 2022). Parents who drink alcohol should be prepared to discuss with children about alcohol use and the impact that early alcohol onset can have on youth. Practitioners should also work with youth to build their discretion on their parents’ behaviors and their capability to assess their health behaviors. Educational outreach with youth on the difference between positive relationships and blind modeling could positively impact the early onset use of alcohol rates.

Conclusion

The national representative study confirmed that positive parent-youth relationships might increase the likelihood of early onset of alcohol use for adolescents whose parents use alcohol themselves. The result expanded the literature on the protective role of parent-youth relationships, indicating that close relationships between parents and youths could be risky for youths if the parents drink alcohol. The current study informs substance use services for youths and families, suggesting a need to guide youths in their decision-making process of alcohol use and help alcohol-involved parents build positive relationships with their children without inducing the children’s early onset of alcohol use.

References

Adolfsen, F., Strøm, H. K., Martinussen, M., Natvig, H., Eisemann, M., Handegård, B. H., & Koposov, R. (2014). Early drinking onset: A study of prevalence and determinants among 13-year-old adolescents in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 55(5), 505–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12151

Alati, R., Baker, P., Betts, K. S., Connor, J. P., Little, K., Sanson, A., & Olsson, C. A. (2014). The role of parental alcohol use, parental discipline and antisocial behaviour on adolescent drinking trajectories. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 134, 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.030

Andrews, J. A., Hops, H., & Duncan, S. C. (1997). Adolescent modeling of parent substance use: The moderating effect of the relationship with the parent. Journal of Family Psychology, 11(3), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.11.3.259

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1963). Social learning and personality development. Holt.

Brincks, A., Perrino, T., Estrada, Y., & Prado, G. (2022). Preventing alcohol use among Hispanic adolescents through a family-based intervention: The role of parent alcohol misuse. Journal of Family Psychology, 37(1), 105–109. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0001038

Brody, G. H., Ge, X., Katz, J., & Arias, I. (2000). A longitudinal analysis of internalization of parental alcohol-use norms and adolescent alcohol use. Applied Developmental Science, 4(2), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0402_2

Brook, J. S., Brook, D. W., Zhang, C., & Cohen, P. (2009). Pathways from adolescent parent-child conflict to substance use disorders in the fourth decade of life. American Journal on Addictions, 18(3), 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550490902786793

Brook, J. S., Balka, E. B., Crossman, A. M., Dermatis, H., Galanter, M., & Brook, D. W. (2010). The relationship between parental alcohol use, early and late adolescent alcohol use, and young adult psychological symptoms: A longitudinal study. The American Journal on Addictions, 19(6), 534–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00083.x

Burk, W. J., van der Vorst, H., Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2012). Alcohol use and friendship dynamics: Selection and socialization in early-, middle-, and late-adolescent peer networks. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73(1), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2012.73.89

Colder, C. R., Campbell, R. T., Ruel, E., Richardson, J. L., & Flay, B. R. (2002). A finite mixture model of growth trajectories of adolescent alcohol use: Predictors and consequences. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(4), 976.

Englund, M. M., Egeland, B., Oliva, E. M., & Collins, W. A. (2008). Childhood and adolescent predictors of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood: A longitudinal developmental analysis. Addiction, 103, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02174.x

Health Promotion Administration (2022). 2021 Youth health behaviors survey. Health Promotion Administration Youth Health Behaviors Survey. Retrieved June 6, 2023 from https://www.hpa.gov.tw/Pages/Detail.aspx?nodeid=257&pid=16037

Hirschi, T. (2015). Social control theory: A control theory of delinquency. In F. Williams III & M. McShane (Eds.), Criminology theory (2nd ed., pp. 289–305). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315721781

Kogan, S. M. (2017). The role of parents and families in preventing young adult alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(2), 127–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.019

Leung, R. K., Toumbourou, J. W., & Hemphill, S. A. (2014). The effect of peer influence and selection processes on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Health Psychology Review, 8(4), 426–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2011.587961

Mares, S. H. W., van der Vorst, H., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A. (2011). Parental alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, and alcohol-specific attitudes, alcohol-specific communication, and adolescent excessive alcohol use and alcohol-related problems: An indirect path model. Addictive Behaviors, 36(3), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.013

Mares, S. H. W., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., Burk, W. J., van der Vorst, H., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2012). Parental alcohol-specific rules and alcohol use from early adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(7), 798–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02533.x

Mundt, M. P. (2011). The impact of peer social networks on adolescent alcohol use initiation. Academic Pediatrics, 11(5), 414–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2011.05.005

National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (2015). Acute alcohol sensitivity. National Academies. Retrieved June 6, 2023 from http://www.nap.edu/catalog/21794

Patte, K., Qian, W., & Leatherdale, S. (2017). Is binge drinking onset timing related to academic performance, engagement, and aspirations among youth in the COMPASS study? Substance Use & Misuse, 52, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1306562

Qu, Y., Fuligni, A. J., Galvan, A., & Telzer, E. H. (2015). Buffering effect of positive parent–child relationships on adolescent risk taking: A longitudinal neuroimaging investigation. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 15(C), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2015.08.005

Rose, R. J., Dick, D. M., Viken, R. J., Pulkkinen, L., & Kaprio, J. (2001). Drinking or abstaining at age 14? A genetic epidemiological study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 25(11), 1594–1604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02166.x

Rusby, J. C., Light, J. M., Crowley, R., & Westling, E. (2018). Influence of parent–youth relationship, parental monitoring, and parent substance use on adolescent substance use onset. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(3), 310. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000350

Shen, A.C.-T. (2009). Self-esteem of young adults experiencing interparental violence and child physical maltreatment: Parental and peer relationships as mediators. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(5), 770–794. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508317188

Shen, A.C.-T., Feng, J. Y., Feng, J.-Y., Wei, H.-S., Hsieh, Y.-P., Huang, S.C.-Y., & Hwa, H.-L. (2019). Who gets protection? A national study of multiple victimization and child protection among Taiwanese children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(17), 3737–3761. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516670885

Skeer, M. R., McCormick, M. C., Normand, S.-L.T., Mimiaga, M. J., Buka, S. L., & Gilman, S. E. (2011). Gender differences in the association between family conflict and adolescent substance use disorders. Journal of Adolescent Health, 49(2), 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.003

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71(4), 1072–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00210

Taber-Thomas, B., & Pérez-Edgar, K. (2015). Emerging adulthood brain development. Oxford University Press.

Tharp, A. T., & Noonan, R. K. (2012). Associations between three characteristics of parent–youth relationships, youth substance use, and dating attitudes. Health Promotion Practice, 13(4), 515–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839910386220

Trucco, E. M. (2020). A review of psychosocial factors linked to adolescent substance use. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 196, 172969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2020.172969

Trucco, E. M., Colder, C. R., & Wieczorek, W. F. (2011). Vulnerability to peer influence: A moderated mediation study of early adolescent alcohol use initiation. Addictive Behaviors, 36(7), 729–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.02.008

Van Der Vorst, H., Engels, R. C., Meeus, W., Deković, M., & Van Leeuwe, J. (2005). The role of alcohol-specific socialization in adolescents’ drinking behaviour. Addiction, 100(10), 1464–1476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01193.x

Van Der Vorst, H., William Burk, J., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2010). The role of parental alcohol-specific communication in early adolescents’ alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 111(3), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.023

White, H. R., Johnson, V., & Buyske, S. (2000). Parental modeling and parenting behavior effects on offspring alcohol and cigarette use: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse, 12(3), 287–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00056-0

Yap, M. B., Cheong, T. W., Zaravinos-Tsakos, F., Lubman, D. I., & Jorm, A. F. (2017). Modifiable parenting factors associated with adolescent alcohol misuse: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Addiction, 112(7), 1142–1162. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13785

Yu, J. (2003). The association between parental alcohol-related behaviors and children’s drinking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 69(3), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00324-1

Funding

This study was funded by the National Taiwan University Children and Family Research Center sponsored by the CTBC Charity Foundation (Grant number:112L9A00405, FR012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. All authors whose names appear on the submission made substantial contributions to the study approve the manuscript to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ Note

The study data are available only to the research team, as stated in the IRB protocol.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, CY., Shen, A.CT., Hsieh, YP. et al. Parent-Youth Relationships and Youth Alcohol Use: The Moderating Role of Parental Alcohol Use. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01177-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01177-w