Abstract

The expansion of simulated ‘free-to-play’ gambling-themed activities on social media sites such as Facebook is a topic of growing research interest, with some conjecture that these activities may enable, or otherwise be associated with, gambling and problem gambling. This paper describes findings from an in-depth qualitative study which aimed to explore the interrelationships between social casino games, gambling, and problem gambling. Social casino games are typically promoted via social media sites (e.g., Facebook) and involve structurally realistic simulated forms of gambling (e.g., poker, slot machines). Ten adult users of social casino games were asked to describe: (1) their history of experiences with these activities, (2) their exposure to promotions relating to social casino games, and, (3) the perceived influence of these activities on their gambling behaviour. Respondents reported frequent exposure to promotions for social casino games and that being connected to a social network of players was a significant factor in determining their engagement in these activities. However, involvement in social casino games did not appear to affect the likelihood of gambling or the risk of problem gambling. Some problem gamblers did report, however, that these games could sometimes trigger a desire to engage in gambling. Interestingly, social casino games were commonly perceived as a safe activity that may act as a substitution for gambling. Further empirical research should investigate this possibility in more detail.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The introduction and rapid adoption of new technologies is often accompanied by concerns about their potential negative social impact. Such concerns have been raised in relation to various forms of Internet gambling given their potential to influence gambling-related problems (Gainsbury, Russell, Hing et al. 2014; Gainsbury et al. 2014a, b, c, d; Griffiths et al. 2009; Wood and Williams 2011). Similarly, the advent of online video games that feature virtual worlds with almost limitless content has enabled individuals to play excessively to the detriment of their health and psychological wellbeing (King and Delfabbro 2009; Yau et al. 2012). In this paper, we examine a new class of online activities, termed ‘social casino games’, which contain features of both gambling and gaming activities (see Gainsbury et al. 2014a, b, c, d). These games involve simulated (i.e., non-financial) forms of gambling and are typically hosted on and promoted via social media sites. The primary aim of this study was to explore potential interrelationships between social casino games, gambling, and problem gambling, as well as examine any similarities between social casino gaming experiences with video gaming and gambling. Given that research in this area is in its infancy (King et al. 2014), the focus of this study was to obtain in-depth qualitative information to guide and inform larger and more directed empirical studies of simulated gambling in both normal and vulnerable populations, such and young people and problem gamblers.

The Growth of Social Media

The widespread availability of the Internet means that online activities are now easily accessible ‘24/7’ throughout the developed world. One of the most popular online activities and sites involve the use of social media. Social media refers to sites that facilitate communication between dyads as well as groups of individuals, including organisations, the sharing of information, social rankings and comparisons, and access to a wide variety of games and other entertainment-related activities. Approximately 26 % of the world’s population are active social network users, including 56 % of the population of North America, and more than 43 % of Western Europe, Oceania, South America and East Asia (We Are Social 2014). Australia is one of the most ‘connected’ countries, with 89 % of the total population having a social network account that is used for an average of two hours per day (We Are Social 2014).

Social Casino Games

Social casino games refer to online gambling-themed games that do not require payment to play or provide a direct payout or monetary prizes (Gainsbury, Hing et al. 2014). They are hosted on or interact with a social media platform, including through mobile applications (apps). Their central theme is a simulation of a gambling activity (e.g., poker, slots, roulette, bingo, keno, betting). These games have massively increased in popularity since their inception and are currently played by an estimated 173 million people worldwide, with the number of users doubling between 2010 and 2012 (Morgan Stanley 2012). Social casino games occupy a prominent place within ‘casual’ gaming marketplaces, and are often presented or categorised in these markets under a broad classification of ‘games’ rather than having a special designation for their gambling themes (e.g., ‘gambling games’). Social casino games represented five of the top 23 Facebook games in 2013 based on user popularity, Facebook implementation, growth and overall quality (Takahashi 2013). Although these games are free to play, users may in some games opt to purchase virtual currency using real world currency (i.e., “freemium”), but this currency is not refundable or redeemable for real money at any point in the game. The estimated value of the global social casino game market was US$2.9 billion in 2013 and is forecast to rise to US$4.4 billion by 2015 (SuperData 2013).

Social casino games are typically not classified as gambling activities as they do not do not award monetary prizes, do not require payment, and the outcomes of games are not necessarily randomly determined or identical to real world gambling activities (Gainsbury, Hing et al. 2014; King et al. 2010; Owens 2010). The Internet gambling market is estimated to be twelve times larger than the social casino game market in terms of revenue, but approximately three times as many people play social casino games than participate in gambling activities (Morgan Stanley 2012). There has been significant convergence between the social casino gaming and Internet gambling industries in an attempt to capture people interested in gambling-themed activities by offering alternate products and game platforms (Gainsbury, Hing et al. 2014; King et al. 2010; Schneider 2012). This has resulted in gambling products being offered on social media platforms and through mobile apps, and gambling and gaming companies offering both social and gambling products using similar brand names and graphics. Unlike gamblers, who by definition wager money, only an estimated 2 % of all social casino game players ever pay to play (Morgan Stanley 2012). Preliminary research shows that some individuals engage in both of these activities (Gainsbury et al. 2014a, b, c, d).

The concomitant increase in the popularity of social casino games and Internet gambling has led to concerns that social casino games may be harmful if consumers have difficulties distinguishing gaming from gambling (Torres and Goggin 2014). Demonstration (“demo”) or practice play on casino games with inflated payout rates (see Smeaton and Griffiths 2004) has been shown to promote user confidence in gambling abilities, resulting in significantly greater betting in subsequent gambling sessions (Bednarz et al. 2013). Some evidence suggests that adolescents can distinguish between social casino games and online gambling, although a minority focus on the structural similarities of both games and perceive the purchase of credits with real money to constitute gambling (Carran 2014). The increasing popularity of social casino games has been suggested to produce several possible outcomes for the gambling landscape, including (a) further normalisation of gambling and increased availability of gambling activities, (b) increased public knowledge and acceptance of these activities, including favourable attitudes and impressions of gambling among gambling-naïve populations such as children, and (c) less reliance on land-based gambling venues for gambling opportunities.

Currently, there is limited evidence on the impact of promotions of gambling and social casino games on actual uptake of other gambling activities. Survey-based studies have shown an association between the use of social casino games and online gambling and related problems in samples of adolescents and young adults (Byrne 2004; Floros, Siomos, Fisoun, and Geroukalis 2013; Forrest et al. 2009; King et al. 2014; McBride and Derevensky 2012). However, such studies do not allow causal inferences or insights into the potential influence of these games on gambling. Additionally, such work has not examined the possibility of ‘third variable’ explanations for associations between simulated and monetary gambling, such as personal preferences, personality and other psychological factors, social and environmental factors, family background, and existing gambling problems.

A recent survey in Great Britain (Parke et al. 2013) reported that approximately two-thirds of gambling counsellors (n = 19) had clients who had engaged in social casino games. However, there was no consensus among counsellors as to whether social casino games had contributed to gambling problems. Some counsellors reported that social casino games were helpful for clients in allowing them to manage their gambling urges without spending money. For others, social casino games triggered an urge to gamble, particularly in instances when they experiences ‘wins’ in the social casino game. Some clients reported that social casino games were their first experience with gambling-type activities, but their role in the individual’s transition to gambling and related problems was not clear, indicating that it was difficult to extricate the specific influence of these games within a complex history of gambling experiences. Another study involving focus groups of university students reported that, for some individuals, the motivation of playing ‘just for fun’ transferred to their online gambling, thereby devaluing the perceived amount of money spent (Wohl et al. 2014). Social casino games were also perceived by some participants as being helpful in the acquisition of gambling skills in preparation for online play. Preliminary findings from a survey of social casino gamers (n = 182) reported that 20 % of players had taken up online gambling at the six month follow-up (Wohl et al. 2014), suggesting that a minority of players may migrate to ‘riskier’ gambling activities.

The available literature on social casino games is relatively sparse, thus far indicating a range of possible relationships to financial forms of gambling and problem gambling. However, the emerging research base suggests that social casino games may potentially exert some proximal influence on gambling thoughts and behaviours, thereby highlighting the need for further research in this area. The current study provides in-depth insights into the interrelationships between social casino games, gambling and problem gambling by exploring the range of player experiences from the perspective of gamers and gamblers. It was hoped that the collection of data on user experiences would supplement academic conjecture to assist in informing larger scale investigations in this area.

Method

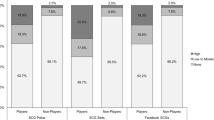

Participants were recruited from an existing sample of social casino gamers, Internet gamblers and social media users who had agreed to be contacted for future research. Participants were recruited by email and interviewed by phone using a structured interview. A summary of the characteristics of the 10 participants (6 males, 4 females) is provided in Table 1. The study attempted to recruit the following categories of users: (1) those who were experiencing problems with gambling and who gambled online; (2) those who gambled and used social casino games; and (3) those who only used social casino games. Social media use included active use of sites such as Facebook, Twitter and other sites that facilitated comparable social activities. Ethics approval was granted for this study by the Human Research Ethics Board of the third author’s institution.

Procedure

Interviews were conducted by a registered psychologist in September 2013 and were recorded and transcribed in preparation for thematic analysis. Each participant was provided with a $50 shopping voucher as compensation. Each interview required 30 to 45 min. Studies have shown that telephone interviews facilitate higher levels of disclosure of high-risk and socially undesirable behaviours, such as addictions, compared to face-to-face research (Novick 2008). This method also enabled participants to be recruited from across Australia to avoid potential bias in any region-specific sample.

The interview included questions relating to the following areas:

-

(a)

Social media and social casino game experience: Participant’s experience with social media, social casino games, how they learnt about the games, and associated promotions;

-

(b)

Gambling experience: Participant’s experience of gambling online and offline; use and experiences with practice sites; and changes in their gambling resulting from recent advances in online technologies;

-

(c)

Gambling promotions: Participant’s exposure to promotions for gambling via social media;

-

(d)

Problems with gambling: Perceptions of the extent to which social media influenced people’s involvement with gambling; whether social casino games contribute to the development of problem gambling; and any personal experiences indicating links between social casino games and gambling problems.

Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis is a method for identifying and analysing patterns of meaning in a data set (Braun and Clarke 2006). Thematic analysis was chosen as the most appropriate qualitative method as this enabled a range of ideas and concepts to be mapped out and for the most salient themes to be summarised within categories (Harper 2012). A theme refers to a specific pattern of meaning, which contains concepts manifested directly and indirectly within interviews (Joffe 2012). Thematic analysis is suitable for preliminary investigations as it recognises all themes that are discussed, but focuses on the most prevalent themes, without sacrificing depth of analysis. Unlike interviews conducted in broader areas of enquiry (e.g., in journalism or the law) where views are often combined in a tendentious manner to fulfil the objectives of a story, systematic qualitative analysis takes all views into account and presents them objectively. The aim is to highlight the diversity of opinion, to highlight common or more dominant views, and to capture these in a way that places people’s experience into a meaningful context. Given the nature of the topic, our focus was on factual accounts of people’s experience rather than to capture the depth of subjective experience. At the present time, the extent of social media based gambling is relatively unclear, so our aim was to take the first steps towards understanding the nature of people’s behaviour. It was hoped that this would provide a foundation for more nuanced questions relating to experiences that this study would confirm as being of relevance to people who interact with these new technologies.

Interview transcripts were classified into themes and coded by the interviewer for each of the principal interview questions. These extracts were then provided to a second independent rater who coded the responses according to the same categories. Inter-rater reliability was high, with 90 % of responses classified identically by both researchers. The discrepant 10 % of responses were then discussed so that agreement was reached concerning classification. Individual responses are presented to demonstrate dominant themes and the range of themes in respondents’ experiences and perceptions.

Results

Table 2 summarises the main themes and sub-themes identified in this analysis.

Introduction to Social Casino Games

Participants’ decision to try social casino games was most strongly influenced by peers and family members. Seven participants identified social influence as the principal factor leading to their involvement in these activities. For example, one respondent recalled that ‘friends on Facebook said ‘Hey look check this out, you can play the slots and it costs nothing’ (7, F, 25-39, SCG, MG, PG). Another respondent was influenced by the numerous ‘likes by friends and relatives’ (8, M, 30+, SCG, MG, PG). For two participants, advertising on social media was their principal means of introduction to social casino gaming. One participant, who had experienced gambling problems and had self-excluded from several monetary gambling sites, emphasised the continuous nature of solicitations to play and the prominence and ubiquity of advertising in social media:

They’re always advertised on Facebook … it keeps coming up down one side only on the news feed even when you ask them to stop putting them on there. They still come back eventually and there are so many different ones, it’s ridiculous. (4, F, 45+, SCG, MG, PG)

Only one respondent reported being introduced to social casino games by actively searching for them on social media.

Promotions for Social Casino Games

Four participants identified that the primary types of promotion received for social casino games were links, popular posts (i.e., ‘likes’ on posts promoting the game), and emails or notifications generated either by the system or peers and family. One participant pointed out how ‘refer-a-friend’ incentives encouraged sharing of links and engagement in the game to earn and use the associated free credits:

… those invites have say a small amount of in-game currency attached to it, so if you do click on that invite the incentive is that you will receive that much money. Your friends also … receive an incentive for sending you that invite …There’s an incentive on both sides. (10, M, 25-39, SCG, MG)

Another interviewee questioned the personalised nature of the invitation automatically generated by friends sending the link:

The invite frames itself [as] … ‘I’m playing this, why don’t you join me’ … But I never felt like I was really playing with them but it’s making out as if you are.’ (1, M, 20-24, SCG)

Social media provides frequent and possibly automated reminders to engage in gaming through the offer of additional tokens or free games. One participant noted how a social casino site she uses ‘provides free coins every hour’ (8, M, 30+, SCG, MG, PG) and another, a frequent social media user, described his experience when logging on to a social media platform:

Every time I log into Facebook or social media there is always a new promotion… You need to receive the incentive… You need to sign up and register your details on the sites to get that incentive. You might get free spends and then a login bonus code. Sometimes it’s for new account holders only. (10, M, 25–39, SCG, MG)

Cross-Promotions for Gambling

Cross-promotions for real money gambling rarely occurred while participants were using social media sites and games. One described by a problem gambler involved her needing to be present in a land-based venue to win vouchers for gambling; she could also win social casino game currency by ‘liking’ the venue on Facebook:

… they want you to like Facebook [and] they want you to like their bingo centre on Facebook. If you do that you go in the draw to win $50 bingo vouchers … you are given further credits and games in terms of tokens if you like these sites or direct people to real bingo. If you like them on Facebook every Sunday they call out names [for] this draw (7, F, 25–39, SCG, MG, PG)

One participant noted that the same products were appearing in both social casino games and land-based gambling venues. Presumably, offering replicated products build users’ familiarity with them:

I'm seeing more and more slots at the bricks and mortar establishments online or vice versa, ’cause obviously they’re developed online before they might come out for real here. … Yep, same bonus features and all that same sort of stuff. (6, M, 25–39, SCG, MG)

As one participant pointed out, many of the controls in land-based venues are not available or effective in social media platforms:

I used to gamble poker machines and switched to online gambling using Facebook … I gambled for money prior to going on Facebook but then the problem continued with Facebook and I’ve had to have myself excluded from multiple sites. I get very angry and frustrated with it because it keeps drawing them in. I started gambling pokies in pubs out of loneliness and then I got hooked. Even though I had myself excluded from venues, with Facebook it is always advertised on there and even when you arrange to stop it, stuff keeps on coming up. (4, F, 45+, SCG, MG, PG)

Practice sites were also noted as a pervasive promotional vehicle for monetary gambling and are discussed below.

Motivations for Playing Social Casino Games

Motivations for playing social casino games varied, with some directly linked to gambling. Some participants wanted to learn about new games before gambling on them, suggesting that social casino games can be used as a ‘training ground’ before transitioning to gambling. One participant explained:

I haven’t … played poker at the casino … so I was probably more interested in playing poker online to get an idea of how it went without having to stake any money. … I can just learn and then see how I go, and if I like it well then I can go and do it for real. (1, M, 20–24, SCG)

Other respondents with a history of financial gambling reported that they used social gaming equivalents to practice and hone their skills, presumably to enhance their likelihood of winning when gambling for money. While there was some agreement that the social casino game equivalent emulated the real money forms sufficiently for them to improve their gambling skills, it was noted that practice sites in particular provide artificially better outcomes and could therefore distort a user’s assessment of personal skill level. A typical comment was:

I’m really aware of like the online casino games … you know the little trials they do, you think you’re really good at it and know what you’re doing, and then when it comes to the real thing, that’s not the case. (9, M, 25–39, SCG, MG, PG)

One respondent, a casino dealer, used social casino games as a substitute for gambling and to improve his skills for when he gambled on casino games interstate (as he was not allowed to gamble in his workplace which was the only casino in his home state). He noted ‘as a dealer you realise in time that exposure is a key advantage over other players, so … definitely there’s an element of practice and exposure that social media enables me to have’ (10, M, 25–39, SCG, MG). Interestingly, this participant also practised on social casino games to enhance his on-the-job training. He explained:

… most recently I got introduced to… American craps, and in preparation for training for that game I accessed a lot of online tools and social media too to learn the basics of the game … Oh it was invaluable really … you can really see how the game works in real time. … (I gained) proficiency and understanding. (10, M, 25–39, SCG, MG)

One problem gambler substituted social casino gaming for gambling in attempting ‘to control my urge to gamble real money’ (4, F, 45+, SCG, MG, PG). This participant further explained:

I used to gamble poker machines and switched to online gambling using Facebook. This is now controlled by exclusion from real money gambling sites and using only token sites. (4, F, 45+, SCG, MG, PG)

Similarly, another described using social casino games to try to rehabilitate her boyfriend who had a gambling problem, although with limited success:

… my partner has a serious gambling problem. And so when I first … found out about these apps I tried to … get him to have a go with them … At first he wasn’t much interested but here and there he’ll … just sit and play on them for hours and hours and hours, which is better than being gone for hours and hours and hours. On the odd occasion it has, yeah, saved some money. (3, F, 20–24, SCG)

Other participants, including problem gamblers, used social casino games to substitute for gambling when they were short of money. Some perceived social casino games as an inexpensive gambling substitute that also offered better value for money through longer playing time. Many participants spoke about how social media, especially through mobile technology, has increased the time they spend on gaming. One explained:

I’m happy to spend $20 online knowing I get credits to last me for a few weeks [whereas] in a bricks and mortar establishment I could spend 20 bucks in two minutes … I think that the social media has probably increased my time-wise, but not … necessarily the amount-wise of what I’m doing. (6, M, 25–39, SCG, MG)

However, others appeared to enhance their enjoyment from social casino games by extending their playing time through bonuses, which appeared to increase with frequency of play. One interviewee took up a particular social casino game promotion that gave players $100 for the chance to win real money, explaining:

If you accumulate the money you’d get to keep it as long as you played … about 1,000 hands … it took me maybe a couple of months to play … I finished with about $106 … I got a free tee-shirt … (and) about six dollars (5, M, 35–44, SCG, MG)

Player Experiences with Social Casino Games

In addition to the insights above, other aspects of participants’ social casino gaming highlight similarities and differences with gambling. One important discussion point was the topic of financial expenditure in social casino games. Seven participants, including two who indicated that they had wanted to play at no cost, suggested that social casino gaming had enticed them into spending money on the game. Several examples of the methods used to entice gamers to spend money were identified, accompanied by the user rationale of ‘by the time you’re practised it is very tempting to stay in the game’ (5, M, 35–44, SCG, MG). Another participant, a problem gambler, noted:

You can play the slots and it costs nothing … it did at first, and then gradually they sort of want you to buy more credit. … sometimes I’d spend up to $80 or $100 just purchasing credit. (7, F, 25–39, SCG, MG, PG)

However, it should be noted that the interviewees who spent money generally did so infrequently and with small amounts. Five respondents were content to play without spending money. Another noted that he only spent money when provided with particularly good offers. In general, however, this participant considered that spending money on social casino games ‘is definitely not value for money … in something that’s virtual … a virtual world’ (6, M, 25–39, SCG, MG).

Two other participants were explicit that if they were going to spend money on social casino games, they may as well gamble with money instead. For one participant, spending the money on gambling would at least provide the chance to win money back, while for another, gambling had the extra bonus of social interaction:

… if I was going to play a slot machine on Facebook I might as well just do it at the pub and talk to the people there at the pub if that’s what I wanted to do. (1, M, 20–24, SCG)

A few gamblers reported that the social casino game experience did not match the level of thrill experienced in gambling. This was the experience of one respondent, especially for the social game equivalents of gambling forms he had used. Having played slots in land-based venues, he took up the social game version ‘for a bit of fun and it’s initially attractive but then I got a little bored … it wasn’t the thrill of actually getting real money’ (1, M, 20–24, SCG). This experience was in contrast to social poker games which he enjoyed more because he had less experience playing poker for money. Even so, he noted ‘I still … didn’t have a great experience there … because I’ve played poker with friends before’ (1, M, 20–24, SCG). Similarly, in relation to practice sites, one problem gambler stated:

Actually I don’t like them … I much prefer dealing with money. I mean win or lose I much prefer it. … I know I’ve got that option and sometimes I use it if I, you know, don’t have any money in my debit card … but I’ll try for free things and no deposit bonuses. (7, F, 25–39, SCG, MG, PG)

Another participant noted that social casino games offered most excitement and most closely matched a real gambling experience when the stakes were high, that:

… you can kind of emulate the real thrill of gambling, even with in-game currency that’s not connected to real currency, as long as those levels of play are high stakes. That’s the kind of thrill that you try to copy. (10, M, 25–39, SCG, MG)

Another potential difference between social casino gaming and many forms of gambling are its social aspects. However, there was only limited discussion of social interaction by participants, except for being introduced to social casino games by friends and family. In fact, others noted how social casino games did not feel very social. In relation to Zynga Poker, one said ‘I felt that I was playing with machines’ (1, M, 20–24, SCG). Even though a social media site might ‘show your friends who are playing it … and their scores …it doesn’t mean that they’re playing it now or that they’ve continued to play it’ (1, M, 20–24, SCG). However, two respondents made reference to playing social casino games with friends. One did so infrequently, while the other discussed how he prefers social casino games on Facebook rather than on apps because ‘it’s got that element of a real interaction, so you have to deal with people making real, more realistic decisions instead of actually playing against a computer’ (10, M, 25–39, SCG, MG).

Participants shared other negative experiences of social casino gaming. One of these was a perception that games were rigged, which led to distrust, particularly in relation to practice sites. A further drawback was the potential for long hours of play and addiction. One problem gambler estimated spending 100 h per week on social casino games in sessions of up to 18 h (8, M, 30+, SCG, MG, PG). Another interviewee considered that high stakes social casino gaming could lead to addiction:

… the thrill of gambling is directly related to how addictive it is and how addicted the player will become to that thrill. So if you play on a casual basis with a bit of in-game money it’s harder to emulate that thrill, so the negative aspect to gambling might not impact too much on that type of player. Only when those stakes are higher that you might actually develop a bit more of an addiction to it even if it’s not real. (10, M, 25–39, SCG, MG)

Transitions Between Social Casino Games and Gambling

Only one participant, a problem gambler, was explicit that her experience with social casino games had led her to gambling. She described how social media platforms may provide a trigger for problem gambling through encouraging ongoing engagement in simulated gambling and using online credits to continually extend playing time. This may be problematic if transferred to online gambling:

I ended up starting just for fun, then I would pay for … credit …. just to extend your time playing… and then I just decided well if I’m gonna do that… …I might as well just play online slots with the real money … I just play the slots on casino sites. It depends on whether I’ve got money. (7, F, 25–39, SCG, MG, PG)

However, two participants, neither of whom had a gambling problem, had the opposite experience. One recalled ‘I was playing poker with friends just around a real table, but then I found out about Zynga and … it just grew from there’. Another explained how playing social casino games had lessened his attraction to monetary gambling, ‘that it didn’t have such a pull anymore … [and] lessened my involvement in the real world at going to the casino. (1, M, 20–24, SCG).

Interactions with Problem Gambling

Four interviewees were experiencing problems with gambling. They also gambled online and played social casino games. These participants related mixed influences of their social casino gaming on their gambling. One spoke about the potential trigger for gambling that social casino gaming can provide:

I do still tend to play the DoubleDown at the moment, but it’s not making me want to gamble at the moment, not anymore, so I seem to have got through that … it has made me in the past want to go and try win some money somehow. (4, F, 45+, SCG, MG, PG)

This same participant also implied that prolific gambling promotions seen on social media sites when playing non-monetary casino games are a constant reminder of gambling ‘because you go on Facebook all the time and it’s there in your face all the time’ (4, F, 45+, SCG, MG, PG). However, this participant’s gambling problem appeared to be lessening, with some of this reduction attributed to her social casino game play. Interestingly, she explained that this was because losing on social casino games reminds her of the likelihood of losing at gambling:

It’s good for me to go on there and just lose everything … even though it’s free you still don’t necessarily do any good, and it reminds me that I don’t do any good when I go and play pokies myself. (4, F, 45+, SCG, MG, PG)

Another problem gambler reported spending less on gambling following her social casino game experiences, although any causal pathway appeared indirect. She commenced her gambling on land-based slot machines, transitioned to online social slots, and then to online real money slots. Her experience with social casino games led her to prefer the online environment. In her home environment, she feels more in control and spends about 70 % on online gambling of what she used to spend on land-based gambling. She explained: ‘I have no control over my money at a venue … whereas online… it’s generally much better with protecting my money’ (7, F, 25–39, SCG, MG, PG).

A third problem gambler, and a heavy user of social casino games, was ambivalent about any links between social casino games and problem gambling. His gambling problem was related to slot machines and he also played social slots. Additionally, he used practice sites and social casino games to hone his skills for land-based poker tournaments. However, when asked whether social casino games can make it more likely that someone develops problems with gambling, he replied:

Yes and no. First of all if you’re going to gamble, regardless of whether you’re doing it on social media or not, you’re going to do it anyway. And that’s most probably influences from your past experience with it, your family environment and numerous other factors … but if you’re not doing it for money, you’re probably just a social interaction that you have with your friends. It could be just a time filler until you’re doing something else, so … it can go either way. (8, M, 30+, SCG, MG, PG)

The fourth problem gambler was a light user of social casino games and his online gambling was mainly on sports betting. While his use of Twitter to gain information on sports betting had increased his gambling, his use of social casino games did not appear to have any influence. While he played social slots, roulette and blackjack, he was not attracted to the online gambling forms of these games, saying he would rather ‘play a personal game … at least you’re there for the experience, at least you’re there in person. What’s the point of being at a computer and playing those games?’ (9, M, 25–39, SCG, MG, PG).

Discussion

This study has highlighted the diverse range of experiences that social casino gaming provides to its user base. Notably, most respondents reported very high levels of exposure to gaming and gambling advertising on social media sites. Some participants described the degree of exposure as ‘relentless’, suggesting that this advertising had assumed a prominent place on social media. Similar marketing strategies appear to be used by both social casino games and online gambling sites. Promotions for social casino games most often involved pop-up advertisements in social media sites and email invitations with refer-a-friend incentives. A notable feature of social media advertising is that promotions are propagated via the social network in a similar manner to a contagious virus (see LaPlante and Shaffer 2007), ‘infecting’ all users in the network irrespective of their profile characteristics or gambling preferences. Although some participants described an experience of attempting to ‘block’ such promotions, they nevertheless continued to be exposed to further gambling promotional material. This may suggest, therefore, that it is very difficult for social media users to avoid (or be ‘inoculated’ from) all gambling promotions in this medium. There were also reports of promotions in which support for the social media site (e.g., ‘likes’ for Facebook) was connected to opportunities to engage in gambling and gaming activities. Respondents indicated that gaming promotions offered a variety of free credits, bonuses, and special offers to attract new recruits. Taken together, these findings appear very similar to previous studies of advertising for online gambling (e.g., Hing et al. 2014).

There was strong support that the ‘social’ component of social media sites plays an important role in the promotion of both gambling and gaming. Respondents reported that information concerning social casino games was relayed by their social connections either via their endorsement (or ‘liking’ of the activity) or via direct communication. This highlights the influential role of friends, family members, online connections and personal recommendations in encouraging people to try a new online activity. It suggests that the ability to share between online connections on social media platforms may be more influential than paid advertisements and direct emails from gambling or gaming companies. At the same time, preliminary research suggests that socializing is not a common motivation for playing social media games (Wohl et al. 2014), and few respondents in the current study discussed social interaction as a motivator or a feature of their social casino game play. This may suggest that gamers are motivated to share their involvement in social casino games to receive additional credits to facilitate ongoing play, rather than to share their status with their networks. Despite this, these results are consistent with marketing literature that has demonstrated the significant impact of word-of-mouth on consumer decisions because it is created and delivered by a more trustworthy source of information than company-generated advertisements (Chu and Kim 2011). A recent survey in the US found that social media users were most likely to trust recommendations of family and friends, and two-thirds were influenced by advertising with a social content (Nielsen 2011). Our results also indicate that personal recommendations via social media are highly influential, although social media advertising can also be persuasive.

Our interviews captured a wide range of player motivations and experiences for social casino games, which likely reflects the complex nature of the phenomenon. For some people, social casino games were a way to gamble without spending money and provided a lower risk activity than conventional land-based gambling. Social casino and practice games also allowed respondents to learn about gambling and identify whether they enjoyed the activity, and practice playing without risking money or as a form of entertainment. Some respondents described social casino games as less exciting than gambling because they did not present the opportunity to win money, which was directly related to the addictive potential of gambling, however social casino games did satisfy several other important gambling motivations such relieving boredom or escapism. These responses were consistent with Wohl and colleagues’ (2014) preliminary survey findings that social casino gamers are motivated to play for a variety of reasons, including entertainment and stress reduction, as well as the opportunity to build skills.

This study also explored the extent to which simulated gambling may lead some players toward financial gambling, or vice versa. There was some evidence that gambling operators were using social casino games to ‘test’ gambling products before these were launched in venues as well as to encourage venue visitation. The present study is the first to highlight this phenomenon, which may have some serious implications. If social casino games are used to promote venues and/or gambling products, these could be considered a form of advertising. As such, it may be queried as to whether such activities should be regulated under gambling advertising codes of conduct, in order to comply with requirements such as ensuring that advertisements do not appeal to children and adolescents, do not glamorise gambling, and do not unrealistically represent the chances of winning. Some participants specifically expressed views that the social casino and practice games were not trustworthy and overinflated the odds of winning, which is consistent with previous findings (Smeaton and Griffiths 2004). As interest in social casino games increases among regulators, the classification of social casino games offered by gambling operators as advertisements may attract greater interest.

Despite some apparent efforts to encourage customers to transfer to gambling, participants were more likely to report a transfer of interest from gambling to social casino gaming. For some respondents, this was a deliberate action to reduce their gambling and retain control over excessive gambling expenditure, sometimes in combination with self-exclusion from gambling venues and sites. These results are similar to a preliminary survey of social casino gamers (n = 182) that found, at a six-month follow-up, only 22 % had commenced online gambling (Wohl et al. 2014). Preliminary results from a study of university students (n = 28) found that participants reported significantly lower desire to gamble after playing a social casino game, as compared to a non-gambling-themed social game (Wohl et al. 2014). Therefore, it is possible that social casino games may reduce interest in gambling, rather than increase the likelihood of migration to gambling; however, more research is required to test this hypothesis.

Some limited evidence supported concerns that social casino gaming might lead to or exacerbate problem gambling. One participant described developing gambling problems after being introduced to social casino games. However, some participants with pre-existing gambling problems described how playing social casino games could trigger and remind them of gambling, and that spending money to buy virtual credits for social slot games could encourage online gambling so that prizes could be won. Similarly, there was some evidence of respondents spending large amounts of money on virtual credits, which may be considered somewhat speculatively as an emerging subtype of problem gambling, i.e., negative financial consequences without the possibility of the player ‘chasing’ or otherwise recovering monetary losses. Similar to other gambling advertising research findings, including for online gambling (Binde 2009; Derevensky et al. 2010; Grant and Kim 2001; Hing et al. 2014), it may be that the marketing of social casino games presents most risk for existing problem gamblers. Nevertheless, participants in our study more commonly reported that engagement in social casino games had lessened their monetary gambling activities by helping them to manage gambling urges, pass the time, and remind them of the likelihood of losing at monetary gambling. Other problem gamblers reported no apparent influence of their social casino play on their gambling.

Therefore, this study suggests that playing social casino games does entail some risks under certain conditions. Several respondents suggested that the associated advertising had enticed them to spend money. Although games were initially free to play, an individual could and was encouraged to pay to access additional game-time. A considerable amount of time could be spent on these games, potentially leading to harm, including addiction. Participants indicated that the currency within these activities was highly tokenised and therefore wins and losses were relatively lacking in psychological value. Unlike land-based gambling, where physical cash is given to a cashier/croupier or inserted into a machine, all social casino game transactions involve credit cards or e-cash which distances the player from the reality that money is being expended. Previous qualitative studies of gaming machine players (e.g., Griffiths 1995) suggest that tokenisation facilitates spending and makes it harder for people to keep track of their expenditure over time. This problem was reported for social casino sites, but can also be a feature of online gambling and gaming, where players can often pay for additional features, often through a series of micro-transactions.

This is one of the first studies to directly examine the relationship between social casino games and gambling, as well as the impact of advertising for social casino games. However, it is important to recognise that the insights revealed in this study require further investigation using a larger and more diverse sample to enable greater generalisability of the findings. The participants included in this study are not representative of a wider population and it not allow sufficient scope to allow more in depth analysis of more specific populations such as young people. In defence of the sampling, however, it can be noted that this was one of the first studies to use a community rather than student sample. A strength of using thematic analysis in early investigations of this topic is that it provides a clear and objective account of people’s experiences in a manner that does not restrict the responses categories to pre-conceived categories or topic areas that may not be inclusive of people’s actual experiences. Although it is possible to analyse qualitative data using more discursive methods that try to understand how people conceptualise and articulate their experiences linguistically, such interpretive methods did not appear appropriate in this paper given our focus on objective reports of social gaming activity. We would, however, suggest that studies of this nature could be extended to encompass more detailed qualitative methods (e.g., Interpretative Phenomological Analysis or IPA) that attempts to capture peoples’ lived experiences more carefully through more structured interviews. Such research could, for example, be used to compare people’s perceptions of social casino gambling and other simular activities with more conventional gambling activities. Greater focus could be given to how these games are experienced as leisure activities; what needs or motivations they address; and, the extent to which players feel that they are able to control the amount of time they spend playing. Other broader sociological analyses could also focus on the social relationships and interactions that revolve around these activities; the networks and social communities and how the desire for challenge and competition embeds these activities in people’s daily lives at home, work or in other settings.

Conclusions

This is the first study that examines the relationship between, and impact of, social casino games on gambling from the perspective of gamers and gamblers. Social media evidently plays an important role in the promotion of gambling and social casino games. Promotions for social casino games may have relatively little impact on gambling and related problems for most users. Experienced users appear able to readily discriminate between games and gambling and understand the substantial differences in activities when monetary risk becomes involved. Further, it is possible that social casino games may actually play a role in harm minimisation for gambling. Nonetheless, for some individuals who may be at-risk for or already experiencing gambling problems, social casino games could have a problematic impact.

The current findings provide only preliminary insights into the interactions between social casino games, gambling, and problem gambling. Our qualitative approach to this growing research area may inform large scale research studies by highlighting key issues for further investigation, such as the role of social casino games in contributing to, exacerbating or reducing gambling disorders. Experimental research could also assess whether specific structural elements of social casino games may influence gambling thoughts and behaviours. Studies are also needed to investigate how social media can be optimally utilised to facilitate responsible use of social casino games and gambling activities.

References

Bednarz, J., Delfabbro, P., & King, D. (2013). Practice makes poorer: Practice gambling modes and their effects on real-play in simulated roulette. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1-15.

Binde, P. (2009). Exploring the impact of gambling advertising: an interview study of problem gamblers. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7(4), 541–554.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

Byrne, A. M. (2004). An exploratory analysis of internet gambling among youth. Doctoral dissertation, McGill University.

Carran, M. (2014). Social gaming and real money gambling – Is further regulation truly needed? Paper presented at the 5th International Gambling Conference, 20 Feb, 2014, Auckland, New Zealand.

Chu, S. C., & Kim, Y. (2011). Determinants of consumer engagement in electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in social networking sites. International Journal of Advertising, 30(1), 47–75.

Derevensky, J., Sklar, A., Gupta, R., & Messerlian, C. (2010). An empirical study examining the impact of gambling advertisements on adolescent gambling attitudes and behaviors. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 8(1), 21–34.

Floros, G. D., Siomos, K., Fisoun, V., & Geroukalis, D. (2013). Adolescent online gambling: the impact of parental practices and correlates with online activities. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29(1), 131–150.

Forrest, D. K., McHale, I., & Parke, J. (2009). Appendix 5: full report of statistical regression analysis, in Ipsos MORI. British survey of children, the national lottery and gambling 2008–09: report of a quantitative survey. London: National Lottery Commission.

Gainsbury, S., Hing, N., Delfabbro, P., & King, D. (2014a). A taxonomy of gambling and casino games via social media and online technologies. International Gambling Studies, 14(2), 196–213. doi:10.1080/14459795.2014.890634.

Gainsbury, S., Russell, A., & Hing, N. (2014b). An investigation of social casino gaming among land-based and internet gamblers: a comparison of socio-demographic characteristics, gambling and co-morbidities. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 126–135. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.031.

Gainsbury, S., Russell, A., Hing, N., Wood, R., Lubman, D., & Blaszczynski, A. (2014c). The prevalence and determinants of problem gambling in Australia: assessing the impact of interactive gambling and new technologies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi:10.1037/a0036207. Published online May 2014.

Gainsbury, S., Russell, A., Wood, R., Hing, N., & Blaszczynski, A. (2014d). How risky is internet gambling? a comparison of subgroups of internet gamblers based on problem gambling status. New Media & Society. doi:10.1177/1461444813518185. Published OnlineFirst Jan 15, 2014.

Grant, J., & Kim, S. (2001). Demographic and clinical features of 131 adult pathological gamblers. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62, 957–962.

Griffiths, M. (1995). Adolescent gambling. London: Routledge.

Griffiths, M. D., Wardle, H., Orford, J., Sproston, K., & Erens, B. (2009). Sociodemographic correlates of internet gambling: findings from the 2007 British gambling prevalence survey. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 12, 199–202.

Harper, D. (2012). Choosing a qualitative research method. In D. Harper & A. R. Thompson (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: a guide for students and practitioners (1st ed., pp. 83–97). Oxford: Wiley.

Hing, N., Cherney, L., Blaszczynski, A., Gainsbury, S., & Lubman, D. (2014). Do advertising and promotions for online gambling increase gambling consumption? An exploratory study. International Gambling Studies, (ahead-of-print), 1-16. DOI:10.1080/14459795.2014.903989.

Joffe, H. (2012). Thematic analysis. In D. Harper & A. R. Thompson (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: a guide for students and practitioners (1st ed., pp. 210–223). Oxford: Wiley.

King, D. L., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2009). The general health status of heavy video game players: comparisons with Australian normative data. Journal of Cybertherapy and Rehabilitation, 2, 17–26.

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., & Griffiths, M. D. (2010). The convergence of gambling and digital media: implications for gambling in young people. Journal of Gambling Studies, 26, 175–187.

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., Kaptsis, D., & Zwaans, T. (2014). Adolescent simulated gambling via digital and social media: an emerging problem. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 305–313.

LaPlante, D. A., & Shaffer, H. J. (2007). Understanding the influence of gambling opportunities: expanding exposure models to include adaptation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(4), 616–623.

McBride, J., & Derevensky, J. (2012). Internet gambling and risk-taking among students: an exploratory study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 1, 50–58.

Morgan Stanley (2012). Social gambling: Click here to play. Morgan Stanley Research.

Nielsen (2011, Oct 14). How social media impacts brand marketing. Nielsen Newswire. Retrieved from http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/newswire/2011/how-social-media-impacts-brand-marketing.html.

Novick, G. (2008). Is there a bias against telephone interviews in qualitative research? Research in Nursing and Health, 31(4), 391–398.

Owens, M. D., Jr. (2010). If you can’t tweet’em, join’em: the new media, hybrid games, and gambling law. Gaming Law Review and Economics, 14, 669–672.

Parke, J., Wardle, H., Rigbye, J., & Parke, A. (2013). Exploring social gaming: Scoping, classification and evidence review. London: Report commissioned by the UK Gambling Commission.

Schneider, S. (2012). Social gaming and online gambling. Gaming Law Review and Economics, 16, 711–712.

Smeaton, M., & Griffiths, M. (2004). Internet gambling and social responsibility: an exploratory study. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7(1), 49–57.

Superdata (2013). Social casino metrics. Superdata. Retrieved from http://www.superdataresearch.com/market-data/social-casino-metrics/.

Takahashi, D. (2013, Dec 9). Facebook names its top games of 2013. Venture Beat. Retrieved from http://venturebeat.com/2013/12/09/facebook-names-its-top-games-of-2013/.

Torres, C. A., & Goggin, G. (2014). Mobile social gambling: poker’s next frontier. Mobile Media & Communication, 2(1), 94–109.

We Are Social Singapore (2014, Jan 8). Social, Digital & Mobile Around the World. Slideshare. Retrieved from http://www.slideshare.net/wearesocialsg/social-digital-mobile-around-the-world-january-2014.

Wohl, M., Gupta, R., & Derevensky, J. (2014). When is play-for-fun just fun? Identifying factors that predict migration from social networking gaming to Internet gambling. Paper presented at the New Horizons in Responsible Gambling Conference, Vancouver, Canada, January, 2014. Retrieved from http://horizonsrg.bclc.com/past-conferences/2014-speakers-and-presenters/michael-wohl.html.

Wood, R., & Williams, R. (2011). A comparative profile of the internet gambler: demographic characteristics, game play patterns, and problem gambling status. New Media & Society, 13, 1123–1141.

Yau, Y. H., Crowley, M. J., Mayes, L. C., & Potenza, M. N. (2012). Are Internet use and video-game-playing addictive behaviors? biological, clinical and public health implications for youths and adults. Minerva Psichiatrica, 53(3), 153.

Acknowledgments

This study was commissioned by Gambling Research Australia - a partnership between the Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gainsbury, S.M., Hing, N., Delfabbro, P. et al. An Exploratory Study of Interrelationships Between Social Casino Gaming, Gambling, and Problem Gambling. Int J Ment Health Addiction 13, 136–153 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-014-9526-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-014-9526-x