Abstract

This paper describes the methodological changes that occurred across cycles of the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS), specifically outlining the rationale for tracking investigations of families with children at risk of maltreatment in the CIS-2008 cycle. This paper also presents analysis of data from the CIS-2008 examining the differences between those investigations focusing on risk of maltreatment and those investigations focusing on an incident of maltreatment. The CIS-2008 uses a multi-stage sampling design. The final sample selection stage involves identifying children for which (a) there was a concern of a specific incident of maltreatment, and (b) there was no specific concern of past maltreatment but the risk of future maltreatment was being assessed. The present analysis included 11,925 investigations based on specific inclusion criteria. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to better understand maltreatment and risk only investigations in the CIS-2008. Families investigated for alleged maltreatment, compared to those investigated for future risk, were more likely to live in a home that was overcrowded, live with the presence of at least one household hazard, and run out of money for basic necessities. Younger children were more likely to be the subject of a risk investigation. Caregiver alcohol abuse, household hazards, and certain child functioning issues were associated with an increased likelihood in a finding of substantiated maltreatment. Several primary caregiver functioning concerns were associated with the decision to substantiate risk, as well as household hazards and overcrowding. This study represents the first exploration of a national profile of risk only investigations. The analyses provided an opportunity to examine differences in the profile of children and families in risk only investigations and child maltreatment investigations, revealing several important differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The child welfare field continues to distinguish between situations where a child is at risk of maltreatment and situations where incidents of maltreatment have occurred (Berger and Brooks-Gunn 2005; Hamilton-Giachritsis and Browne 2005; Jaudes and Mackey-Bilaver 2008; Mullick et al. 2001; Portwood 1999; Scannapieco and Connell Carrick 2003). In practice, child welfare workers investigate and intervene in many situations in which children have not yet been physically harmed but have been maltreated, and situations where children live in environments and with caregivers whose risk factors increase the likelihood that they will experience maltreatment (Bala 2004; Trocmé et al. 2010a). The conceptual validity of risk of maltreatment is debated (Baird and Wagner 2000; Baumann et al. 2005; Shlonsky and Wagner 2005), and the distinction between substantiated and unsubstantiated maltreatment is questioned by many researchers (Drake et al. 2003; Fluke et al. 2001). Some studies have found that key risk factors for maltreatment such as poverty, caregiver substance abuse issues and child functioning concerns are as likely to be present in unsubstantiated maltreatment investigations as investigations that verify a specific act has been perpetrated against a child (Kohl et al. 2009).

Information on children and families who receive child welfare services across Canada is generally not available at a national level. Some provinces have fairly elaborate province-wide information systems, while in other provinces most service information is only available at a local level. Variations in provincial and territorial statutes and service delivery models further complicate the task of producing national child welfare statistics. The Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS) was developed to overcome these limitations by directly surveying child welfare staff responsible for intake investigations. The CIS is designed to collect information about the children and families who are investigated by child welfare services on a periodic basis from every jurisdiction in Canada using a standardized set of definitions. There have been three cycles of the study conducted in 1998 (Trocmé et al. 2001) 2003 (Trocmé et al. 2005) and 2008 (Public Health Agency of Canada 2010). In 2008, a major change in the study’s definition of an investigation occurred. Where the first two cycles had collected information on only suspected or alleged events of maltreatment, in 2008, workers were asked to complete data collection instruments on both investigations involving events of maltreatment and investigations where there was no specific event of maltreatment but risk of maltreatment. A validation file study using CIS-2003 cases revealed that in some instances child welfare workers were using maltreatment investigations to describe situations where no specific incident had been investigated, but where the concern was risk of future maltreatment (Trocmé et al. 2007). Typically these risk only cases involve situations where concerns about parents, such as substance abuse or mental health, lead to an investigation to determine the risk of future maltreatment. Investigations of children at risk of maltreatment were tracked explicitly in the CIS-2008 by distinguishing between maltreatment investigations and risk-only investigations. In such cases, the investigating worker was asked to specify whether there was significant risk of future maltreatment. This paper discusses the rationale for this change in methodology and uses data from a national Canadian child welfare study (the CIS) to examine the following research questions:

-

1)

How do the profiles of families and children differ across investigations for an event of maltreatment versus risk of maltreatment;

-

2)

Are there differences in the characteristics of families and children in substantiated maltreatment investigations versus substantiated risk investigations;

-

3)

Do the predictors of substantiated maltreatment investigations differ from the predictors of substantiated risk investigations?

Literature Review

Risk is discussed in the literature across two levels: primary and secondary intervention, reflecting two distinct service points. Primary intervention may be defined as service involvement before maltreatment occurs (i.e., risk of maltreatment only). Examples of primary intervention include situations in which the child welfare sector is involved at the time of a child’s birth; maltreatment has not yet occurred in such situations, although the child may be apprehended at birth because certain environmental or caregiver factors indicate a risk of future maltreatment. Secondary intervention may be defined as service involvement after maltreatment has occurred. In secondary intervention, risk is understood as the likelihood that maltreatment will reoccur.

It is difficult to interpret the direction of the relationship between risk factors and maltreatment or risk of maltreatment. Most of the published literature relating to risk in child welfare is cross sectional and, as a result, the correlates of maltreatment could either be risk factors or sequelae or both. That is, it is unclear if maltreatment precedes the characteristics noted below or, alternatively, if such characteristics precede maltreatment. In order to keep the direction consistent in this literature review, studies focusing on maltreatment as a predictor of the risk of long-term outcomes such as physical health issues (e.g., MacMillan 2010) were not included.

Child Characteristics

Certain characteristics of children may increase the likelihood that an investigation for risk of maltreatment will be conducted by a child protection service. An investigation for risk of maltreatment can be triggered by a chronic condition (Fluke et al. 2005; Fudge Schormans and Brown 2002; Jaudes and Mackey-Bilaver 2008; Kahn and Schwalbe 2010), a disability (Fluke et al. 2005), or a sibling being maltreated (Baldwin and Oliver 1975; Greenland 1987; Hamilton-Giachritsis and Browne 2005; Wilson 2004). These risk investigations may be initiated because child welfare workers are aware that children who possess certain characteristics are at heightened risk of maltreatment.

Research indicates that young children with a chronic condition are twice as likely to experience maltreatment in comparison to children without a chronic condition (Jaudes and Mackey-Bilaver 2008). Previous literature has also found increased risk of maltreatment in children who have physical or intellectual disabilities (Fluke et al. 2005; Fudge Schormans and Brown 2002; Kahn and Schwalbe 2010), early histories of abuse or neglect, or emotional or behavioural difficulties (Browne and Saqi 1988; Hamilton and Browne 2002; Jaudes and Mackey-Bilaver 2008). The child welfare system may assess risk of maltreatment in families with children with such physical, cognitive, emotional or behavioural issues, given that these children are at increased risk of maltreatment.

Children with the characteristic(s) noted above are also at increased risk of being repeatedly reported to child protection services. Fluke and his colleagues (2005) found that children with disabilities were approximately 1.5 times more likely to be re-reported than children without disabilities. Similarly, Kahn and Schwalbe (2010) found that children with developmental disabilities were at higher risk of re-reports. Based on this literature, it appears that child protection systems are more likely to identify children as in need of an investigation for risk of maltreatment if they are struggling with developmental concerns.

Early research identified that siblings of abused or neglected children were also at risk of maltreatment (Baldwin and Oliver 1975; Greenland 1987). Debate exists around the mechanisms that mediate the risk of maltreatment for siblings of children who have experienced abuse or neglect. The presence or absence of certain factors may heighten or attenuate the risk of maltreatment for siblings of children who have been maltreated. For instance, the age and gender of the sibling may influence the risk of maltreatment, as well as the relationship of the sibling to both the victim and the perpetrator (Wilson 2004). Hamilton-Giachritsis and Browne (2005) examined the risk of maltreatment among siblings of children referred to child protection services in England for abuse or neglect. The authors found that parental difficulties (i.e., mental health issues, self-harm, substance abuse, intellectual disability, etc.) and family stressors (i.e., large family size, unstable lifestyle, etc.) increased the risk of maltreatment to all siblings.

This literature suggests that certain children are at higher risk of abuse and neglect because of the difficulties they struggle with. Once again, it is important to recognize that causality is difficult to untangle and that it is highly likely that the relationship between children’s physical, cognitive, emotional, behavioural, and developmental issues and their risk and experiences of maltreatment is multi-directional.

Caregiver Characteristics

The presence of certain parental characteristics may increase the likelihood that the child protection system will assess future risk of maltreatment. These parental characteristics include parental mental illness (Hamilton-Giachritsis and Browne 2005; Hindley et al. 2006; Kahn and Schwalbe 2010; Mullick et al. 2001), low-birth weight children (Berger and Brooks-Gunn 2005), and substance misuse (Dixon 1989; Fluke et al. 2005; Hamilton-Giachritsis and Browne 2005; West 1999). In the province of Ontario, the Eligibility Spectrum screening tool subsumes this type of investigation under the category “Caregiver with a Problem” (Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies 2006).

Research indicates that mothers with major psychiatric disorders are at increased risk for perpetrating child maltreatment, with personal insight into mental illness identified as a protective factor reducing the risk of maltreatment (Mullick et al. 2001). Families are also investigated at the child-birth stage for a variety of reasons. One study assessed nurses’ perception of the risk of maltreatment among low-birth-weight children, reporting that risk of maltreatment is influenced by parental knowledge and behaviours (Berger and Brooks-Gunn 2005).

Caregivers with the characteristic(s) noted above are also at increased risk of being re-reported to child protection services. Research indicates that the presence of caregiver alcohol abuse increases the likelihood of a child being re-reported to child welfare (Fluke et al. 2005). Hindley and colleagues (2006) conducted a systematic review of risk factors for child maltreatment recurrence, identifying parental mental health issues as a predictor of recurrent maltreatment. Similarly, Kahn and Schwalbe (2010) found that poor caregiver health was a significant risk factor of re-reports.

As the literature describes, certain caregiver characteristics are linked both with increased surveillance by child protection authorities and the perpetration of maltreatment. Caregivers who struggle with mental health issues, substance misuse, and physical health issues appear to be more likely to be subject of an investigation for risk of maltreatment by child welfare authorities, due to the evidence suggesting these caregiver characteristics create situations that have the potential to be harmful for children. Again, it is possible that these difficulties arise as a result of involvement with child welfare services, rather than representing causes of involvement with child welfare services.

Societal Characteristics

Literature consistently identifies poverty as a factor relevant to understanding maltreatment and risk of maltreatment (Berger and Brooks-Gunn 2005; Cash 2001; Kahn and Schwalbe 2010; McDaniel and Slack 2005; Scannapieco and Connell Carrick 2003). Family poverty influences access to safe and secure housing, which in turn is associated with child maltreatment. Research indicates that families for which maltreatment is substantiated are more likely to live in dangerous home environments (i.e., unsanitary conditions, household hazards, and exposure to environmental dangers) compared to non-maltreating families (Scannapieco and Connell Carrick 2003). Literature also suggests that families who report difficulty in meeting their financial responsibilities are at higher risk of recurrent reports to child welfare authorities (Kahn and Schwalbe 2010), and that assessments of risk by professionals are influenced by familial socioeconomic status (Berger and Brooks-Gunn 2005). In addition, major family life events (i.e., moving, new child, child suspension or expulsion from school) are associated with an increased risk of child maltreatment investigation, even after controlling for parental stress, harsh discipline, and material hardship (McDaniel and Slack 2005). This literature suggests that indicators of poverty are linked with identification to the child welfare system, risk of maltreatment, and experiences of maltreatment.

It appears that factors at the child, family, and societal levels influence the likelihood that a family will be reported to and investigated by child welfare authorities. However, the presence of these factors does not necessarily increase the likelihood that a child will be maltreated, nor does it imply a direction of causality. It is important for the child welfare field to explore the differences between child maltreatment investigations and investigations for risk of maltreatment, in order to understand the clinical nuances distinguishing these two unique contacts with the child welfare system. Exploring these distinctions will assist the child welfare field in designing appropriate services to meet the needs of children and families investigated for both risk of maltreatment and incidents of maltreatment.

In the CIS-2008 sample, families investigated for risk of future maltreatment and families investigated for incidents of maltreatment are considered separately. In reality, certain children within the same family may be maltreated, while certain children may be at risk of being maltreated, and still other children may be both at risk of being maltreated and victims of maltreatment. Although the CIS is unable to capture the intricacies of these situations, the inclusion of risk as a separate type of investigation in the 2008 cycle allows for analysis that will expand the current knowledge base on investigations involving risk of maltreatment in child welfare. The present analysis aims to determine the differences between investigations of maltreatment and investigations of risk of maltreatment, as well as explore the situations in which maltreatment or risk of maltreatment has been substantiated.

Risk Assessment

In the late 1990s, most provinces and territories implemented some type of formalized risk assessment process (Barber et al. 2008). A variety of risk assessment tools and methods have been adopted in a growing number of jurisdictions, in order to aid in the evaluation of future risk of maltreatment. Risk assessment tools are designed to promote structured, thorough, and informed decisions. Various factors are assessed using risk assessment tools, including child strengths and vulnerabilities, caregiver addictions, caregiver mental health, expectations of the child, and sources of familial support and familial stress. Risk assessment tools are intended to supplement clinical decision making and are designed to be used at multiple decision points during child welfare interventions. By 2003, risk investigations were part of standard child welfare investigatory processes in Canada. The CIS-2003 trained workers to only include investigations where there was either alleged maltreatment or a clinical concern during the investigation that the child had experienced an event of maltreatment. However, the possibility that workers had included risk investigations where no specific event of maltreatment had occurred became evident while conducting secondary analyses of the CIS-2003.

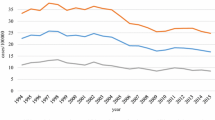

Findings from the CIS-2003 (Trocmé et al. 2005) study revealed a dramatic increase in child maltreatment investigations from 1998 to 2003 in Canada excluding Québec.Footnote 1 The incidence of investigations grew by 86% from 24.6 to 45.7 per 1,000 children. The rate of substantiated maltreatment increased 125%, from 9.6 substantiated cases per 1,000 children in 1998 to 21.7 in 2003. Part of the increase in substantiated cases appears to reflect a shift in the way investigating workers classify cases, with a much smaller proportion of cases being classified as suspected (13% in 2003 compared to 24% in 1998 in Canada, excluding Québec). The challenge in examining these changes was determining the extent to which they were a result of differences in child welfare policies and practices or variation in the types of cases being referred. Like most public health statistics, the CIS is designed to track incidence of investigated maltreatment by child, not by family. Many jurisdictions, however, process investigations at the family level. The dramatic increase in the rate of investigated and substantiated children appeared to be due in part to a shift in investigation practices. The average number of investigated children per family increased from 1.41 to 1.66. This increase may reflect a greater understanding of the impact of maltreatment, as well as changes in the types of maltreatment investigated, and possibly, in some jurisdictions, changes in administrative procedures.

Two background studies were undertaken to test this hypothesis: the Validation Study (Trocmé et al. 2007) and the Focus Group Study (CIS Research Team 2007).

Validation Study

In order to assess the validity of instrument items prior to the commencement of the 2008 study cycle, study team members conducted both secondary analyses and a file review of maltreatment investigations from one agency that had participated in the CIS-2003 (Trocmé et al. 2007). This agency allowed researchers to review 25% of the 560 maltreatment investigations that were included in the CIS-2003. Five CIS research team members retrieved file information for 144 investigations. The files were reviewed in order to understand specific findings from the CIS-2003 by examining the record of the investigation on the agency’s information system.

The file review found differences in the presentation of the investigated maltreatment on the data collection form compared to the agency file. Four specific types of investigations were reviewed: infant placements from the hospital, those classified as “other physical abuse”, those classified as “other sexual abuse”, and those with an abandonment classification. An examination of investigations involving infants placed in out-of-home care from the hospital was important in beginning to understand the confusion around an investigation of maltreatment and an investigation of a child whose caregiver (s) presented with significant enough functioning concerns to assess the future risk to a child. It was clear that infants placed from hospital had not been maltreated but rather were apprehended based on a serious mental health concern for the caregiver or a substance abuse issue.

For families with investigations of multiple children, the “other physical abuse” and “other sexual abuse” maltreatment categories on the data collection instrument (which were intended to describe situations of severe physical and sexual abuse) were sometimes used to describe the investigation of a sibling of a referred child. These categories were used by workers to document that they remained concerned for the other child(ren) in the home given the context of the event of maltreatment for the referred child, although there had been no specific allegation for the sibling(s). Investigations involving abandonment as the primary maltreatment concern sometimes reflected not the abandonment of a child but rather parent-teen conflict situations that might result in maltreatment if there was not intervention.

Focus Testing

Focus groups were conducted in order to assess the CIS-2008 data collection instrument (CIS Research Team 2007). Using a convenience sample, the CIS-2008 Research Team conducted six focus groups with front-line child protection workers and supervisors across Canada from July to October 2007. The number of workers involved in each focus group ranged from four to 20, and the discussions lasted approximately 2 h at each site. Workers interviewed consistently reported that child protection investigations took place when there was no specific concern of maltreatment but rather focused on the home environment and the impact of specific caregiver concerns such as mental health, alcohol use or drug use on the children in the home.

Methods

The CIS-2008 sample was drawn in three stages: first a representative sample of child welfare agencies from across Canada was selected, then cases were sampled over a 3 month period within the selected agencies, and finally child investigations that met the study criteria were identified from the sampled cases (Trocmé et al. 2010b). The final sample selection stage involved identifying children who had been investigated as a result of concerns related to possible maltreatment. Maltreatment related investigations that met the criteria for inclusion in the CIS included situations where there were concerns that a child may have already been abused or neglected as well as situations where there was no specific concern about past maltreatment but where the risk of future maltreatment was being assessed (Trocmé et al. 2010b). In most jurisdictions cases are open at the level of the family, and therefore procedures had to be developed to determine which specific children in each family had been investigated for maltreatment-related reasons (Trocmé et al. 2010b). In jurisdictions outside of Québec, children eligible for inclusion in the final study sample were identified by having child welfare workers complete the Intake Face Sheet from the CIS-2008 Maltreatment Assessment Form (see Instruments and Data Collection procedures for more details). The Intake Face Sheet allows the investigating worker to identify any children who were being investigated because of maltreatment related concerns (i.e., investigation of possible past incidents of maltreatment or assessment of risk of future maltreatment). In Québec, the identification of maltreatment related investigations was done by including all “retained”Footnote 2 cases with maltreatment-related case classification codes (Trocmé et al. 2010b).

Sample

These procedures yielded a final sample of 15,980 children investigated because of maltreatment related concerns (Trocmé et al. 2010b). For this study, investigations involving families with one child identified for an event of maltreatment and at least one child the focus of an investigation for risk of maltreatment (n = 1,340) were excluded from the analysis in order to compare the profile of investigations with only a maltreatment concern and those with only a risk concern. Investigations focusing on exposure to intimate partner violence as a primary reason for referral (n = 2,715) were also excluded from the sample because these investigations involve a very high rate of both substantiation (78%) and case closure, which makes them systematically different than other maltreatment investigations. The final sample was comprised of 11,925 maltreatment related investigations involving children 15 years of age and younger; 9,092 were investigations focusing on an alleged or suspected incident of maltreatment and 2,833 were investigations focusing on risk of future maltreatment.

Measures

The information was collected using a three-page data collection instrument. Data collected by this instrument included the following: type of investigation (maltreatment or risk only); functioning concerns for the children and their caregivers; whether the household runs out of money; household hazards; and, information about short-term service dispositions. Key clinical variables were included in the model in order to reflect an ecological theory and to determine the relative contribution of clinical variables to the decision to substantiate maltreatment or risk of maltreatment.

Outcome Variable

Substantiated Maltreatment/Risk of Maltreatment

Substantiation was a dichotomous variable, comparing substantiated maltreatment to unfounded maltreatment. Substantiated maltreatment was defined as “the balance of evidence indicates that abuse or neglect had occurred” (CIS-2008 Study Guidebook). Unfounded was defined as “the balance of evidence indicates that abuse or neglect had not occurred”. Suspected investigations were dropped from the multivariate analysis (n = 17,918) because previous research has demonstrated that suspected investigations differ from both unfounded and substantiated investigations (Trocmé et al. 2009).

Substantiated Risk

Substantiated risk was a dichotomous variable, comparing substantiated risk investigations to no risk of future maltreatment. For risk of maltreatment investigations, risk of future maltreatment was measured by the investigating worker indicating that, in his or her clinical judgment, the child was at significant risk of future maltreatment. If the worker answered no to this question, the child was judged not to be at any future risk of maltreatment. Investigations with a finding of “unknown future risk” were not included in the multivariate analysis.

Independent Variables

Professional Referral

Did the referral to the child welfare office/agency come from a professional source. This is a dichotomous variable: yes or no.

Primary Caregiver Functioning

Workers could note up to nine functioning concerns for the primary caregiver. Concerns were: alcohol abuse, drug/solvent abuse, cognitive impairment, mental health issues, physical health issues, few social supports, victim of domestic violence, perpetrator of domestic violence, and history of foster care/group home. Caregiver functioning variables were dichotomous variables with a suspected or confirmed concern coded as ‘noted’ and no and unknown coded as ‘not noted’.

No Second Caregiver in the Home

Workers were asked to describe up to two caregivers in the home. If there was only one caregiver described and there was no second then the home was classified as a single caregiver home.

Home Overcrowded

Worker indicated if the household was made up of multiple families and/or was overcrowded. This was a categorical variable: yes, no or unknown.

Number of Moves in the Past Year

How many times had the family moved in the past year. This was an ordinal variable: none, one, two, three or more or unknown.

Household Regularly Runs out of Money for Basic Necessities

Workers were asked if the household regularly ran out of money for necessities (food, clothing). This was a categorical variable: yes, no or unknown.

Household Hazards

Workers were asked to note if the following hazards were present in the home at the time of the investigation: accessible weapons, accessible drugs, production/trafficking of drugs, chemicals/solvents used in drug production, other home injury hazards, and other home health hazards. This is a dichotomous variable: yes (at least one household hazard was present) or no.

Case Previously Opened

Workers indicated if the case had been previously opened and if it had whether it had been opened one, two or three or more times. This was an ordinal variable.

Child Functioning

Workers could note up to 18 functioning concerns for the investigated child, indicating whether the concern had been confirmed, suspected, was not present or whether it was unknown to the worker. Child functioning variables were dichotomous variables with a suspected or confirmed concern coded as ‘noted’ and no and unknown coded as ‘not noted’. Child functioning concerns included: depression/anxiety/withdrawal, suicidal thoughts, self-harming behaviour, ADD/ADHD, attachment issues, aggression, running (multiple incidents), inappropriate sexual behaviours, Youth Criminal Justice Act involvement, intellectual/developmental disability, failure to meet developmental milestones, academic difficulties, FAS/FAE, positive toxicology at birth, physical disability, alcohol abuse, drug/solvent abuse, other functioning concern.

Data Analysis

A first set of descriptive bivariate analyses were conducted to explore the characteristics of investigations classified as either maltreatment or risk only for all investigations and for substantiated investigations.

Bivariate analyses were also conducted to determine the relationship between the outcome variable (substantiated risk and substantiated maltreatment) and each theoretically relevant predictor variable. For the multivariate models, the goal was to understand which predictors of the decision to substantiate a maltreatment investigation and a risk investigation were significant. Logistic regression was used to predict the outcome variable ongoing service provision. Logistic regression is suited to the type of data that are consistently found in social and behavioural research, where many of the dependent variables of interest are dichotomous and the relationships among the independent and dependent variables are not necessarily linear (Walsh and Ollenburger 2001). In a marginal model, the regression of the outcome on the predictor variables is estimated separately from the within-level correlations and the variances of the regression coefficients.

A two-step analysis procedure was used. All analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 18.0. Only significant predictor variables at the bivariate level (p < .05) were included in the multivariate model. The choice of cutoff point for the decision to substantiate the investigation was set at 0.45 for maltreatment investigations which reflects the proportion of maltreatment investigations substantiated and 0.25 for risk-only investigations. From the first model were extracted predictors with a significant relationship (p < 0.05) to the decision to substantiate the investigation. The model was then run with this smaller set of predictors, only retaining significantly associated predictors (p < 0.05). This last set of independent variables finally leads to a model where all regression coefficients were significantly different from zero (p < 0.01) (Tables 3 and 4). In this analysis, missing data were not included in the bivariate or mutilvariate analysis.

Results

Research Question #1: How Do the Profiles of Families and Children Differ across Investigations for an Event of Maltreatment Versus Risk of Maltreatment?

There were some significant differences between the family and child profiles in investigations classified as risk investigations and child maltreatment investigations. Families investigated for alleged maltreatment were more likely to have a home that was overcrowded, have the presence of a least one household hazard and run out of money for basic necessities. Investigations classified as risk were more likely to involve a single caregiver home, to be transient (3 or more moves in 1 year) and to have a primary caregiver concern noted for alcohol abuse, drug abuse, mental health issues, physical health issues, history of foster care, and victim of domestic violence. Younger children were more likely to be the subject of a risk investigation. Child functioning issues were reported more often in maltreatment investigations except in the case of positive toxicology at birth which was reported at a higher rate in risk only investigations. Please see Table 1 for these results.

Research Question #2: Are There Differences in the Characteristics of Families and Children in Substantiated Maltreatment Investigations Versus Substantiated Risk Investigations?

Table 2 differs from Table 1 with regard to substantiation as it describes only substantiated child maltreatment investigations, and risk investigations where there is confirmed risk of future harm to the child. Substantiated investigations involving maltreatment were more likely to have a professional referral than substantiated risk investigations. All primary caregiver functioning concerns were more likely to be identified in investigations with verified risk of future harm. Investigations with verified risk of future harm were more likely to involve families who were transient (2 or more moves in 1 year) and who ran out of money for basic necessities. Younger children were more likely to be the subject of a substantiated risk investigation. Similarly to the previous table, child functioning issues were identified more often in substantiated maltreatment investigations except for positive toxicology at birth which was more often identified in investigations with verified risk of harm.

Research Question #3: Do the Predictors of Substantiated Maltreatment Investigations Differ from the Predictors of Substantiated Risk Investigations?

Table 3 shows the final model predicting substantiated maltreatment. Together the predictor variables explain 22% of the variance in the substantiation decision, with an overall classification rate of 65%, correctly predicting 68% of substantiated maltreatment investigations. Noted alcohol abuse concerns for the primary caregiver were almost two times more likely (OR = 1.94) to result in a finding of substantiated maltreatment, and the presence of at least one household hazard increased the likelihood of substantiation by over 300% (OR = 3.27). Presence of two family moves in the past year decreased the likelihood of substantiation (OR = .696), whereas three or more family moves in the past year increased the likelihood of substantiation (OR = 1.49). Noted child depression (OR = 1.84), attachment issues (OR = 1.75), aggression (OR = 1.31), and FAS/FAE (OR = 1.96) increased the likelihood that a maltreatment investigation would be substantiated.

Table 4 shows the final model predicting substantiated risk. Seven primary caregiver functioning concerns were related to the decision to substantiate risk. Cognitive impairment, alcohol abuse and few social supports were the concerns most likely to result in substantiated risk. Home overcrowding (OR = 1.21) and at least one household hazard (OR = 2.06) were also significant in the model. Younger children were more likely to have a finding of substantiated risk (OR = .77). Depression and positive toxicology at birth were related to the finding of substantiated risk. The predictors in the final model explained 26% of the variance in the decision to substantiate risk, and the model had an overall classification rate of 68%, 75% of substantiated risk investigations were classified correctly.

Discussion

During the instrument development for the CIS-2008, a decision was made to change the data collection instrument to include risk of future maltreatment as a category workers could endorse as best characterizing the type of investigation they conducted. This assessment was made after recognizing the wide-spread use of risk assessment instruments in most Canadian child welfare jurisdictions, conducting focus groups with child protection workers across Canada, engaging in secondary analyses of data from the previous two cycles of the CIS, and completing a validation study.

Caution should be used in interpreting the results of this study. Data from the CIS-2008 are collected directly from the investigating worker and are not independently verified. These data only represent the concerns that present during an average 6 week investigation period. Additional concerns for the child and the caregiver could arise after the initial investigation. The data used may reflect the focus or approach taken by a worker for a risk investigation versus a maltreatment investigation.

Twenty six percent of investigations conducted by child welfare authorities in Canada in 2008 were categorized as risk investigations where there was no allegation or suspicion of an event of maltreatment but the worker was focusing on the possibility that the child was at risk for future maltreatment. This study provided an opportunity to examine differences in the profile of children and families in risk only investigations and child maltreatment investigations.

This is the first time that a national profile of risk only investigations emerges. A comparison between investigations of events of maltreatment (74% of investigations included in the CIS-2008) and risk only investigations (24% of investigations) reveals some important differences. Families and children in both types of investigations are presenting with similar concerns with respect to the high number of moves within the past year, running out of money for basic household necessities and the presence of a household hazard. However, there are more concerns noted for the primary caregiver in risk investigations (mental health issues, substance abuse issues) than in maltreatment investigations. Conversely, there are fewer concerns noted for children in risk investigations (behavioural and emotional issues) than in maltreatment investigations. Although children under three are more likely to be the subject of a risk investigation and the child functioning concerns may be more appropriate as a measure of functioning for older children, nonetheless approximately one quarter of the investigations conducted in Canada involve situations where the overriding concern for the case is that the caregivers are struggling with an issue of mental health, substance abuse or cognitive impairment.

The need for adequate, effective mental health and substance abuse treatment programs is very apparent in situations where the investigating worker has identified a concern that places a child at future risk of child maltreatment as well as for children who have been victimized. Substance abuse and mental health issues comprise the majority of concerns noted for the families as well as being highly predictive of the decision to substantiate maltreatment and future maltreatment. Families who have theoretically not crossed the line into readily proven child abuse or neglect, still need services to address abusive or neglectful parenting practices or substantial family dysfunction that threatens the safety of children require no less an urgent, thoughtful approach than children who have been maltreated (Fallon et al. 2011). Younger children are more likely than older children to have a finding of substantiated risk which means that there is an opportunity to prevent emotional or physical harm to the child by treating the caregiver’s condition. Although the data used for this study are cross sectional, more research and precise instrumentation is required to understand what level of improved functioning is necessary to ensure that a child’s safety and well-being is no longer a child welfare concern (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2010a). Both investigations focusing on future risk and investigations of specific events of maltreatment have similar high rates of recurrence of case openings, 24% of risk investigations and child maltreatment investigations had been previously opened more than 3 times. There is a lack of coordination and collaboration between child welfare, courts, and the substance misuse service sector with models of collaborative intervention varying widely and little research on the effectiveness of collaborative approaches (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2010b).

Differential response has been proposed as a possible solution to providing services to families with these complex needs and its efficacy has been addressed elsewhere (Anselmo et al. 2003; Waldegrave and Coy 2005; Waldfogel 2004). It reflects an attempt to adjust our policies and programs to the importance of distinguishing between protection investigations, where forensic evidence gathering must be a critical priority, from assessments where family functioning and children’s needs should be at the forefront. More research is needed to identify which families are best served by an alternative response. This analysis offers some evidence that children identified as being at risk for future maltreatment may present with different concerns than children who have been identified as victims. Understanding important clinical differences between these children and families will lead to interventions that address their specific needs in policy, practice and research.

Limitations

This study used cross sectional data; therefore, it is unclear if maltreatment precedes the substance and/or mental health issues noted or, alternatively, if such characteristics precede maltreatment. There is a lack of reliability/validity of caseworker assessment of risk (Barber et al. 2008). The data used in the study relies, to a large extent, on the opinion of a social worker as to whether they think a child will be maltreated in the future. This is a limitation of the data source (Grove and Meehl 1996).

Notes

In the CIS-2003 data from Quebec was collected electronically from an information system. Only level of substantiation and maltreatment type was matched to the rest of Canada data.

Agencies in Quebec use a structured phone screening process whereby approximately half of all referrals are “retained” for evaluation. In Québec, the CIS sampled retained maltreatment related reports that involved cases that were not already open.

References

Anselmo, S., Pickford, R., Goodman, P. (2003). Alberta response model: Transforming outcomes for children and youth. Ottawa, ON: Centre of Excellence for Child Welfare. http://www.mcdses.co.monterey.ca.us/reports/downloads/P2S PrgramandDataReview CombinedReport 6–20.pdf

Baird, C., & Wagner, D. (2000). The relative validity of actuarial and consensus-based risk assessment systems. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(11/12), 839–871.

Bala, N. (2004). Child welfare law in Canada: An introduction. In N. Bala, M. K. Zapf, R. J. Williams, R. Vogl, & J. P. Hornick (Eds.), Canadian child welfare law (pp. 1–26). Toronto: Thompson Educational Publishing Inc.

Baldwin, J. A., & Oliver, J. E. (1975). Epidemiology and family characteristics of severely abused children. British Journal of Preventative and Social Medicine, 29, 205–221.

Barber, J. G., Shlonsky, A., Black, T., Goodman, D., & Trocmé, N. (2008). Reliability and predictive validity of a consensus-based risk assessment tool. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 2(2), 173–195.

Baumann, D. J., Law, J. R., Sheets, J., Reid, G., & Graham, J. C. (2005). Evaluating the effectiveness of actuarial risk assessment models. Children and Youth Services Review, 27(5), 465–490.

Berger, L. M., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2005). Socioeconomic status, parenting knowledge and behaviors, and perceived maltreatment of young low-birth-weight children. The Social Service Review, 79(2), 237–267.

Browne, K. D., & Saqi, S. (1988). Approaches to screening for child abuse and neglect. In K. D. Browne, C. Davies, & P. Stratton (Eds.), Early prediction and prevention of child abuse (pp. 57–86). Chichester: Wiley.

Cash, S. J. (2001). Risk assessment in child welfare: The art and science. Children and Youth Services Review, 23(1), 811–830.

CIS Research Team. (2007). Focus groups summary. Unpublished manuscript, University of Toronto

Dixon, S. D. (1989). Effects of transplacental exposure to cocaine and methamphetamine on the neonate. The Western Journal of Medicine, 150, 436–442.

Drake, B., Jonson-Reid, M., Way, I., & Chung, S. (2003). Substantiation and recidivism. Child Maltreatment, 8(4), 248–260.

Fallon, B., Trocmé, N., & MacLaurin, B. (2011). Should child protection services respond differently to maltreatment, risk of maltreatment, and risk of harm? Child Abuse & Neglect, 35, 236–239.

Fluke, J. D., Parry, C., & Baumann, D. (2001). Dynamics of unsubstantiated reports of child abuse and neglect. Denver: Annual Research Conference, Child Welfare League of America.

Fluke, J. D., Shusterman, G. R., Hollinshead, D. M., & Yuan, Y. Y. T. (2005). Rereporting and recurrence of child maltreatment: Findings from NCANDS. Washington: U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Fudge Schormans, A., & Brown, I. (2002). An investigation into the characteristics of maltreatment of children with developmental delays and the alleged perpetrators of this maltreatment. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 9(1), 1–19.

Greenland, C. (1987). Preventing CAN deaths. London: Tavistock.

Grove, W. M., & Meehl, P. E. (1996). Comparative efficiency of informal (subjective, impressionistic) and formal (mechanical, algorithmic) prediction procedures. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 2(2), 293–323.

Hamilton, C. E., & Browne, K. D. (2002). Predicting physical maltreatment. In K. D. Browne, C. Davies, & P. Stratton (Eds.), Early prediction and prevention of child abuse. Chichester: Wiley.

Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. E., & Browne, K. D. (2005). A retrospective study of risk to siblings in abusing families. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(4), 619–624.

Hindley, N., Ramchandani, P. G., & Jones, D. P. H. (2006). Risk factors for recurrence of maltreatment: A systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 91, 744–752.

Jaudes, P. K., & Mackey-Bilaver, L. (2008). Do chronic conditions increase young children’s risk of being maltreated? Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 671–681.

Kahn, J. M., & Schwalbe, C. (2010). The timing to and risk factors associated with child welfare recidivism at two decision-making points. Children and Youth Services Review, 32, 1035–1044.

Kohl, P. L., Jonson-Reid, M., & Drake, B. (2009). Time to leave substantiation behind: Findings from a national probability study. Child Maltreatment, 14(1), 17–26.

MacMillan, H. (2010). Commentary: Child maltreatment and physical health: A call to action. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35(5), 533–535.

McDaniel, M., & Slack, K. (2005). Major life events and the risk of a child maltreatment investigation. Children and Youth Services Review, 27, 171–195.

Mullick, M., Miller, L. J., & Jacobsen, T. (2001). Insight into mental illness and child maltreatment risk among mothers with major psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Services, 52(4), 488–492.

Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies. (2006). Eligibility spectrum. Toronto: Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies.

Portwood, S. (1999). Coming to terms with a consensual definition of child maltreatment. Child Maltreatment, 4(1), 56–68.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2010). Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect 2008 (CIS-2008): Major findings. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada.

Scannapieco, M., & Connell Carrick, K. (2003). Families in poverty: Those who maltreat their infants and toddlers and those who do not. Journal of Family Social Work, 7(3), 49–70.

Shlonsky, A., & Wagner, D. (2005). The next step: Integrating actuarial risk assessment and clinical judgement into an evidence-based practice framework in CPS case management. Children and Youth Services Review, 27, 409–427.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010a). Drug testing in child welfare: Practice and policy considerations. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2010b). Substance abuse specialists in child welfare agencies and dependency courts: Considerations for program designers and evaluators. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Trocmé, N., Fallon, B., Black, T., Felstiner, C., Parker, J., Singer, T. (2007). CIS validation study: Summary report. Unpublished manuscript, University of Toronto

Trocmé, N., Fallon, B., MacLaurin, B., Daciuk, J., Felstiner, C., Black, T. et al. (2005). Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect–2003: Major findings. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada

Trocmé, N., Fallon, B., MacLaurin, B., Sinha, V., Black, T., Fast, E., et al. (2010a). Rates of maltreatment-related investigations in the CIS-1998, CIS-2003, and CIS-2008. In PHAC (Ed.), Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect–2008: Major findings. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada.

Trocmé, N., Fallon, B., MacLaurin, B., Sinha, V., Black, T., Fast, E., et al. (2010b). Methods. In PHAC (Ed.), Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect–2008: Major findings. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada.

Trocmé, N., Knoke, D., Fallon, B., & MacLaurin, B. (2009). Differentiating between substantiated, suspected, and unsubstantiated maltreatment in Canada. Child Maltreatment, 14(1), 4–16.

Trocmé, N., MacLaurin, B., Fallon, B., Daciuk, J., Billingsley, D., Tourigny, M., et al. (2001). Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect 1998 (CIS-1998): Final report. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada.

Waldegrave, S., & Coy, F. (2005). A differential response model for child protection in New Zealand: Supporting more timely and effective responses to notification. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 25, 32–48.

Waldfogel, J. (2004). Welfare reform and the child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review, 26, 919–939.

Walsh, A., & Ollenburger, J. (2001). Essential statistics for the social and behavioral sciences. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall.

West, K. (1999). Overview: The drug endangered children’s project. Drugs and Endangered Children, 1, 4–5.

Wilson, R. F. (2004). Recognizing the threat posed by an incestuous parent to the victim’s siblings: Part I. Appraising the risk. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13(2), 263–276.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fallon, B., Trocmé, N., MacLaurin, B. et al. Untangling Risk of Maltreatment from Events of Maltreatment: An Analysis of the 2008 Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS-2008). Int J Ment Health Addiction 9, 460–479 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-011-9351-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-011-9351-4