Abstract

Against a background of public health, we sought to examine and explain gambling behaviours, motivations and consequences of Indigenous Australians in northern New South Wales. Adhering to national Aboriginal and ethical guidelines and using qualitative methods, 169 Indigenous Australians were interviewed individually and in small groups using semi-structured interviews. Over 100 in-depth interviews were conducted. Using thematic analysis, the results indicate a range of contrasting social and more problematic gambling behaviours, motivations and consequences. Acknowledging the cultural distinctiveness of Indigenous gambling and distinguishing between their social and more problematic gambling behaviours, motivations and consequences can assist with public health prevention, harm reduction and treatment programs for Indigenous gamblers in all parts of Australia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Interest in gambling as a public health issue is increasing (Korn and Shaffer 1999; Productivity Commission 2009). The aim of public health is to increase control over and improve the health of a population (World Health Organisation (WHO) 1986). Taking a public health approach to gambling has shifted the focus away from analysis of individual gambler behaviour toward an analysis of influences that assist the majority of gamblers to increase their control over gambling (Korn and Shaffer 1999). Numerous prevalence studies have examined gambling among large populations (Cox et al. 2005; Petry et al. 2005; Productivity Commission 1999; Volberg 2004). They have revealed valuable information about gambling behaviors, motivations, and consequences in dominant cultural groups (Wynne and McCready 2005). However, responses from smaller population sub-groups such as Indigenous Australians have proved much more difficult to capture (Young et al. 2006).Footnote 1 For example, telephone surveys have been found to be highly skewed to urban and more affluent Indigenous Australians who have reliable telephone services (McMillen and Togni 2000; ACIL Tasman Consulting 2006). There is a paucity of research about gambling by Indigenous Australians. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine and explain Indigenous gambling behaviours, motivations and consequences in northern New South Wales, Australia.

More than 300 years ago Macassan traders introduced card gambling to Indigenous Australians in the north (Breen 2008). Today, card gambling is still widely apparent in many Indigenous communities (Breen et al. 2010). Also apparent is the use of commercial forms of gambling, such as gaming machines, casinos and TABs, by Indigenous Australians (McMillen and Donnelly 2008). However, little public knowledge exists about most aspects of contemporary Indigenous gambling, cards or commercial gambling.

The international knowledge base about Indigenous gambling is meagre, providing little insight into gambling as a socio-cultural activity (Wynne and McCready 2005). However, international research has found that Indigenous peoples are often at higher risk of gambling problems than non-Indigenous peoples. Epidemiological surveys of First Nation populations in Canada, the United States and New Zealand have described high rates of problem gambling (McGowan and Nixon 2004). From a public health view, Shaffer and Korn (2002) suggested gambling exists on a behavioural continuum ranging from no gambling and healthy gambling up to intensive and unhealthy gambling. They argue that seeing gambling as a continuum is an important point for identifying treatment strategies and interventions for problem gamblers as well as those who maybe at risk of gambling problems including, for example, a range of brief treatments and measures for harm reduction. When gambling behaviour is considered on a continuum from healthy to unhealthy (Korn and Shaffer 1999) these international studies have found higher proportions of Indigenous populations to be at the unhealthy end of the scale.

Like Korn and Shaffer (1999), the Productivity Commission (2010) also noted that problem gambling can be seen as a continuum of increasing severity, from no risk or harm up to significant risk. For example, at one end is the recreational gambler; at the other end are people who are experiencing (or causing) severe harm from gambling such as poverty, family breakdown and suicide. ‘Between these two extremes, there are people facing either heightened risks of future problems or varying levels of harm’ (Productivity Commission 2010:5.8). Although there is scant research into gambling by Indigenous Australians, what has been done suggests higher problem gambling rates than for non-Indigenous Australians (McMillen and Donnelly 2008).

In terms of prior research, only 14 studies specific to Indigenous Australian gambling have been published. Ethnographic studies have focused on Indigenous card gambling, each presenting a case of one remote community with limited generalisability (Altman 1985; Goodale 1987; Hunter 1993; Hunter and Spargo 1988; Martin 1993; Paterson 2007). Four published studies have focused specifically on Indigenous participation in commercial gambling. They obtained convenience samples of just 222 Indigenous people in New South Wales (Dickerson et al. 1996) and 128 in Queensland (Queensland Department of Families, Youth and Community Care 1996) to quantitatively analyse some aspects of gambling behaviour. An observational study of people of Indigenous appearance was conducted in one casino (Foote 1996). Young and Stevens (2009) analysed secondary data linking negative life events and reported gambling problems among the Indigenous population by jurisdiction and remoteness.

Four other specific studies relied on key informant consultation to describe Indigenous gambling activities, to speculate on impacts and recommend gambling health promotion and help services for Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council (AHMRC), 2007; Christie and Greatorex 2009; Cultural Perspectives 2005; McDonald and Wombo 2006). These were not underpinned by any empirical data on Indigenous gambling behavior, although the consultations by Christie and Greatorex (2009) were based in the Yolgnu Indigenous community in the Northern Territory.

Non Indigenous-specific population surveys have also captured some data on Indigenous Australian gambling. These telephone surveys yielded small skewed samples of Indigenous respondents and so prevent meaningful conclusions (McMillen and Donnelly 2008); for example a statewide telephone survey of gambling in the Northern Territory excluded the two-thirds of Indigenous residents without a home phone, with the 126 responses representing only more affluent urban residents (Young et al. 2006). Two Queensland surveys found Indigenous people are over-represented among at-risk/problem gamblers, but no other Indigenous data were reported (Queensland Government 2005; 2008).

This limited research is reflected in inadequate culturally sensitive public health strategies for Indigenous gamblers (AHMRC 2007). Understanding a range of different gambling behaviors, motivations and consequences is crucial for developing culturally relevant public health programs that might assist Indigenous gamblers increase their control over gambling.

Methods

Cultural considerations and ethical issues were key factors in deciding on an appropriate research design. As a team of three researchers, one Indigenous man and two non-Indigenous women, we considered that a qualitative research design was a culturally sensitive method. According to Hepburn and Twining (2005), the qualitative style is a familiar, comfortable, sharing technique for Indigenous Australians. This investigation was also situated within an interpretive paradigm using a social constructivist approach. A social constructivist approach assumes that reality is constructed by people within their social and cultural contexts (Gubrium and Holstein 2000). Reality is created by people as they attempt to interpret and make sense of their surrounds (Guba and Lincoln 1989). This approach provided rich in-depth and valuable data.

Cultural considerations and relationship building were perceived as vital. Atkinson (2002), an Indigenous researcher, states that relationships are a fundamental feature of Indigenous philosophies. Relationships were built in this study by being introduced to people, taking time to talk to and learn from people, identifying and using dominant communication styles, active listening, ongoing consultation, feedback, and being respectful as suggested earlier by Steane et al. (1998). Thus, appropriate permissions were sought, negative and positive aspects of gambling were reported, and only what had been negotiated was reported.

Three sets of ethical guidelines underpinned this research. The first is a national statement on human research ethics (National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2007); the second set guides general Indigenous research (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) 2002); and the third set focuses specifically on health-related Indigenous research (NHMRC 2003). The research responsibilities for abiding by ethical and cultural considerations were treated seriously. We sought and were granted permission from several Elders to conduct the research. Issues such as privacy, confidentiality, safety, consent, equitable treatment, lack of deception, responsible stewardship of the research process and materials were vitally important. Ethical approval was also obtained through the university Human Research Ethics Committee.

Participants and Setting

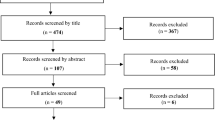

We attempted to capture the experiences and views of a broad range of Indigenous Australians living in northern New South Wales. Participants had to be over 18 years of age and belong to, or identify strongly with, a local Indigenous community. From past contacts with local Indigenous people we compiled an initial list of knowledgeable participants. We asked each person to identify others who might be well-informed about gambling and able to contribute to the project. The selection of knowledgeable people was guided by the expert judgment of the participants (Patton 1990). Snowball sampling was used for recruitment until saturation was reached.

This iterative process yielded participation of 169 Indigenous people in 103 interviews. There were 42 individual and 61 small group interviews involving 95 women and 74 men. Participants included Indigenous community members, gamblers and non-gamblers, and representatives of Indigenous organisations, government departments, health, legal, social, community, financial and welfare agencies. Most participants had grown up in families or communities where gambling was present and visible. Many had gambled themselves even if they were non-gamblers now.

Describing the setting, in northern New South Wales the eastern corner is comprised of six adjoining local government areas (LGAs). Although each LGA has a different geographic, social and economic profile, the Indigenous people of the six LGAs make up one tribal group. We visited these six LGAs several times to explain the project, ask for cooperation and provide feedback. On average, 30 Indigenous people were interviewed in each LGA, although only 20 were interviewed in one LGA where the population was small and widely dispersed.

Data Collection

The overarching research goal was to generate rich, thick descriptions (Geertz 1983) of gambling behaviour, motivations and consequences as seen by Indigenous Australians in northern NSW. To collect information to meet the research goal, typical methods of qualitative inquiry, such as personal interviews and extended observations, were used (Creswell 2007). The principal source of information was personal interviews, but participant observation was used to enhance some aspects of the project (for example, observations in commercial gaming venues). Thus, in-depth, semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted with the 169 participants by two or three of the researchers. Some interviews were conducted with small groups of two or three people. Initially phone calls were made to contact people. Then, in most cases, letters were sent to people explaining the research project. Potential participants were given both written and verbal information about the research project and its aims. With further follow-up phone calls, appointments were made for interviews. Interview procedures were explained. All who agreed to participate signed an informed consent form.

The interviews were conducted at participants’ workplaces, community centres, coffee shops and even at home. Participants chose their own site and time. We tried to avoid any perception of researcher dominance as recommended by Indigenous researcher Phillips (2003). To respect cultural and gender roles, interviews with men’s groups were conducted by the Indigenous male researcher. He also took the lead in all other interviews. They lasted between 30 and 60 min. In most cases, these interviews were not recorded, because this was considered culturally too intrusive. Instead, extensive notes were taken and transcribed immediately.

Analysis

The interviews were analysed using thematic analysis, a method of identifying, analysing, and reporting on thematic patterns in the data (Braun and Clarke 2006). A theme captures something important about the data in relation to the research aim (Borrell 2008). Themes might be generated inductively from the raw data or generated deductively from theory and prior research (Braun and Clarke 2006). Data coding, analysis and interpretation processes are not really linear. They usually occur simultaneously, in a circular and iterative way through immersion in the data, in generating codes, searching for and reviewing themes, interpreting and naming themes and finally writing up an account (Spradley 1980). To explain how data interpretation was conducted revealing major themes, the approach adopted was to follow Braun and Clarke’s (2006:87) six stages. These include:

Becoming Familiar With the Data

Immersion in the data was ongoing through repeated reading of the interviews and returning to the field. The processes of research were repeated to get feedback or to clarify matters arising from earlier procedures. Immersion required the development of a meta-awareness of the research while revisiting the data (interview transcripts, observations, notes) and at the same time a micro-awareness of the research in searching through both old and new meanings (Martin 2008). Familiarity with the data and its meaning was formed through immersion, reading and reflection.

Generating Initial Codes

Coding of prominent features of the data was systematically conducted across the entire data set by description, by interpretation and by pattern (Jennings 2001). As a similar set of guiding questions was asked of all research participants, the collected responses from each question were collapsed into one document with their identity attached. The guiding question became the descriptive code label. Paragraphs in that document were numbered and initial coding took place manually. Codes were linked by bracketing units of text, as suggested by Jennings (2001). Interpretive codes were developed at a deeper level of analysis by the text unit, either by a key sentence or a paragraph. These codes were highlighted to distinguish between them as they emerged. Notes were kept to record observations on coding and analysis and to follow new directions.

Searching for Themes

After collating the interpretive codes, further analysis was conducted, to search for patterns and themes. This was done by following Creswell’s (2007:152) advice in reviewing and rearranging the text, by ‘winnowing the data’. The initial themes tended to correlate with the main areas of questioning such as descriptions of gamblers behaviour, motivations and consequences. These were labelled accordingly. Sub-themes were also identified. Groups of sub-themes supported major themes through relatedness and definition. The names of these sub-themes were often derived from quotations or ‘in vivo’ (Creswell 2007:152).

Reviewing Themes

To be confident about the emerging themes, the coding of text was re-visited using a software program Nvivo software V.8 (QSR International 2008). Data were coded by text units (key paragraphs and/or sentences) into broad ‘higher order’ themes. Multiple codes were used if a text theme fitted similar codes to ensure that data and meaning were not lost. As a review tool, the program was effective in handling a large amount of textual data. As a data management tool it helped to ensure nothing was overlooked. It was also useful for exploring ideas and potential relationships.

Defining and Naming Themes

A process of critique, Braun and Clarke (2006) suggest, is involved in reviewing what has emerged from the research from the beginning (at the level of the coded extracts) and towards the end (in relation to the entire data set) of the analysis. Drawing on Martin’s (2008) theory of relatedness, themes were looked at repeatedly to see their relationship to the research aim. Themes were sifted through, compared, contrasted and drawn together using the materials and experiences of the research. This process ensured the authenticity of the range of emerging themes. The result is a representation of a ‘family’ of themes with ‘children’ as sub-themes (Creswell 2007:153). This is depicted as a small set of main over-arching themes with a broader set of sub-themes underneath. A tree diagram represents this family of themes as layers of analysis, with levels of abstraction descending from the top (Creswell 2007). At the bottom, the tree diagram shows a broad data base consisting of relevant research materials. Moving up to the next level, several specific patterns are seen as sub-themes. Then at the top, the diagram narrows to show one or a few main over-arching themes at a more abstract level. For a representation of a tree diagram representing the family theme ‘to win’, see Table 1.

Producing a Report

A research report and several research articles have and will be produced as a result of this research project. Based on a selection of extracts that demonstrate the essence of the research themes, these reports and papers relate the analysis and findings back to the research aim and literature (Braun and Clarke 2006). Reporting the research transforms the tensions and pressure of the investigation into new forms of knowledge.

Results

Emerging from the analysis was a range of themes and sub-themes relating to gambling behaviours, motivations and consequences for card and commercial gambling. These results are now presented.

Card Gambling Behaviour

The popularity of card gambling across the six locations was believed to be in decline compared to people’s memories of card gambling activity in the past. Card gambling had “fallen away as a practice” and disappeared altogether in two locations. One person said “Elders confronted players in early days and stamped it out ... it was not a good lifestyle.” Another person described card gambling as “small nowadays compared to the old days” and “fallen away”, while in the past “growing up, all mothers played cards, the kids were there.” In a different location, a contrasting view about the role of children was put forward where “cards were played in the old days at someone’s house—a social thing. Kids had to sit away from table, not allowed to play. Only adults played cards at Nan’s house on Friday nights. Not done now.” Yet there were still locations now where “both men and women” were said to play “some cards.” In one location this was said to occur “two or three times a week.”

Where card gambling was still being conducted, the majority of research participants reported “mainly female players” and “women were the main players.” In fact one person said that is was “a cultural thing that women gamble”. However, extended family, cousins, friends, social groups and visitors gambled together occasionally. Young males were observed gambling on cards in the main street of one town. Although this was very unusual, people here said “kids play in the street nearly every day, 16 year olds.” Card gambling mainly occurred “in someone’s house” but some people gambled in the open “under trees” especially within designated Indigenous communities.

In most locations, card gambling was said to be more irregular than regular, depending on the presence of an adequate number of players. Yet for some, card gambling was very obvious on “on pay day.” Describing a nearby situation one person stated, “(people) usually play when they get their pay or their pensions and often will gamble all or nearly all away over 2 or 3 days after pay day.”

Gambling sessions varied from short (a couple of hours) to long “sometimes all day or all night” and even longer for a few who “go on for ages”. Card gambling expenditure per session was reported to range from low (about AUS$5) to high (more than AUS$200).Footnote 2 A few people were said to “spend their whole pay sometimes.” The attraction was that others were seen to “walk away with $700–$800 from a $20 start.” Some participants expressed concern about youth card gambling, particularly in developing gambling behaviours that might affect their future as they progress from “underage gambling on cards in the main street ... (to) at 18 they go to the venues.” These gamblers were seen to “learn from older blokes”.

Card Gambling Motivations

Major card gambling motivations were reported be “to win money and to socialize.” Comments describing motivations to win included “the hope of a big win”, “chasing the big win” and “opportunity to win money.” Social motivations were said to be a “way of getting together” and a place to hear “the best stories” to “yarn, joke.”Footnote 3 Others said “card motivations—social, play with friends and family” and “sometimes cousins or friends of cousins”. To a lesser extent, other motivations were reported to be “to reduce boredom” and “to escape” from problems. Some participants combined these motivations as opportunities to “socialise when bored”, for “stress relief, a place to escape” and “they’re chasing the big win—it seems to numb the reality of their lives and they can escape from their problems”.

Consequences of Card Gambling

Both positive and negative consequences flow from gambling conditional on the gambler’s behavior and resources. Positive consequences of card gambling were reported to include social connectedness with other Indigenous people, an occasional win and sharing in a social activity. This was seen by one person as “(cards are) only a social thing—when you haven’t got much money you have to find your own social outlet, therefore cards for women might be footy (football) for men”. Another person summarised this as “social, play with friends and family” and also “to get more money.” Another consequence noted by a few people was that “money stayed in the community” from card games and was not lost to commercial gambling operations.

Negative consequences were said to include individual financial losses, borrowing from others and underage gambling. Some people were said to lose their welfare payments “Seen full pensions go through on cards”. After some people lost their funds and wanted to recover losses, they might ask “if they can borrow from someone.” The expectation of a loan rests on traditional Indigenous reciprocity of sharing resources with those who are in need. Thus, both the lender and borrower were at risk of financial losses. In one location, youth gambling, said to be motivated to win money to purchase desirable goods, was seen as setting youth up to see gambling as a regular way to make money “young kids play cards for money, sets them up for later patterns of gambling.” This was a matter of concern for many participants in this location.

Commercial Gambling Behaviour

Commercial gambling was reported to be much more popular than card gambling with these Indigenous gamblers. Most research participants reported that “a mixture of men and women of all ages” participated in commercial gambling. There was also some evidence that older women “get the bug for gambling” and some “younger people” gambled in their social groups. Gamblers were equally as likely to be “employed and unemployed.” Generally, commercial gambling was seen as a social activity engaged in by couples or small groups rather than a solo activity.

Indigenous commercial gamblers were reported to prefer poker machines, TAB gambling, keno and bingo (in that order).Footnote 4 A few gamblers were said to gamble on both cards and commercial gambling. Generally, poker machine gambling was seen as a “more female” activity, whereas TAB gambling on racing and sports betting was preferred by “mostly men.” Yet one man said his wife “might like to punt too” (on the TAB) and some men were observed to gamble on poker machines. For keno and bingo, both numbers games, participants reported that women played these games in their regular social groups. Keno and bingo were “popular” with groups of all ages “when they are out socially.” One person remarked “we take it in turns to take Aunty to bingo” and another recalled:

My grandfather used to gamble and would start off by taking us all to bingo. We would go to bingo, that church at the back there, the Seventh Day Adventist, then all of us kids and all of our sisters and daughters, he would take all of us kids and we would go to bingo. We were taught how to play bingo when we were kids and then from that any of our social occasions when we would take Nan out for her birthday or anything like that, would involve taking her to a bingo game and pokies.

The most popular day for commercial gambling was said to be pay day and the few days afterwards. Although a few gamblers gambled “three times a week”, the majority gambled “weekly” or “fortnightly” usually linked to their pay cycle. For some gamblers, their gambling frequency “depends on how much money they have” because some might “stay there till they’re broke.” Those who preferred the TAB gambled “mostly at weekends” when racing and sports events were held. Bingo players played in regular sessions, often every week.

In terms of session length, most respondents said a typical poker machine session was “around 2 or 3 hours a day.” However another person remarked “the hours range; with gambling you could be there for an hour, you could be there for 10 hours depending on how quick it takes to get rid of your money.” Less common were very long gambling sessions, all day or all night. “Big gamblers” were recognised as solo gamblers who preferred to gamble alone and for long sessions. In long sessions, these gamblers often spent all their money plus their winnings. Then, “when their money is gone, some scam money from others” to extend their session. TAB gamblers were more likely to gamble in shorter sessions, linked to a racing or sports events. Some TAB gamblers called into gambling venues “two or three times on race day” to place bets.

Typical gambling expenditure was more commonly reported to be in the lower rather than higher range. One person remarked “I don’t gamble very much money, fortnightly event, meet other commitments first.” Many Indigenous people were said to have limited incomes and thus gambling expenditure “depends on whether they have kids or not and whether they have other responsibilities.” However, higher range expenditure was reported as “their whole pay” regardless of the source “whether that’s an unemployment pay or whether that’s a general working pay ... put their whole pay through it and be scratching the next week.”

Higher amounts of money appeared to be spent on poker machines compared to TAB gambling. Poker machine expenditure was reported as being $5–$300 per session. TAB gambling expenditure was said to involve $1–$2 bets, with most people spending $5–$20 over a whole day. A comparison made by one participant was “TAB spending is less than on machines (and) over a longer time” and “if someone wins on a horse they usually keep the winnings”. However some gamblers pooled funds with their social or family group and shared any joint winnings. Gambling “with a group” was seen as having a “social aspect for families to get together.” A comparison between social and more problematic gamblers was seen as “problem gamblers do it on their own, social gamblers do it with their mob.” Older people were perceived to have “limits with money” whereas younger people who “have no responsibility” tended to spend more. The majority of gamblers were said to “set limits” on gambling expenditure and meet their financial commitments first but some gambled all their money hoping to increase their income. Some gamblers “create a ripple effect of borrowing from one another” by spending more than they can afford. One person linked expenditure to motivations with this remark: “People who are addicted spend everything, all their pay. People who are in control only spend what they can afford.”

Commercial Gambling Motivations

Commercial gambling motivations were very similar to card gambling motivations. To win and to socialize were the strongest reported motivations. To a lesser degree, other motivations were to escape, reduce boredom, and fill in time. To win included the opportunity to win money including “looking for a way to get extra money” and “a quick way to make money.” Others noted that people gambled to win money for debt repayment and to make purchases. Some gamblers were “always broke ... living in poverty ... need money to improve life.” Some people were reported to gamble because they have a “belief in luck” or that they “might get lucky” while others gambled to experience the “thrill of winning money.”

Socially, gambling was part of a “social outing” and “a social activity.” One person explained “in pubs and clubs you’d see ... big numbers of Aboriginal people ... that’s a big thing for us, knowing other people are there.” Another suggested that, when gambling together, some Indigenous people felt the “camaraderie” in that they were “being accepted by everyone else (so) they keep doing it.” Some people used gambling “to escape ... to get away from the drinking at home”, from “struggles” and relief from “loneliness, pain and trauma.” One person described gambling to escape this way:

It’s just a way to get away from the terms of life. There are some horrific, in terms of lifestyle, there’s a lot of suicide; there’s a lot of death, a lot of failing health around the place, escapism to get away from that stuff.

In regards to reducing boredom and filling in time, some gambled for “entertainment, not much to do up here”, because it was “relaxing ... a relief” or because they were “bored, nothing to do.”

Consequences of Commercial Gambling

Gambling consequences were reported as positive and negative. The most important positive consequence of Indigenous commercial gambling was socialising according to most participants. To a lesser degree, other positive consequences were having an occasional win, being accepted and comfortable, and easy access to venue facilities.

Socialising included meeting up with others, “having a yarn”, sharing common interests, and enjoying some relaxation together. One person explained they “take Mum to the club, it’s time out and an escape for the week.” For one participant having a drink and gambling on poker machines was socially comfortable and inclusive: “All your mates and everyone else is there. If you’re going to have a beer then you’re going to have a press to be sociable with them.” Footnote 5

Winning at gambling created some excitement, because “if they have a win [there is] joy.” A win can “help family out and buy new things.” Bingo especially was seen to have positive consequences because “it brings people together ... contributes to community.”

Most Indigenous gamblers gambled in venues that were “easily accessible ... in the middle of town, close to the shops and you can walk” to reach them. Gamblers preferred venues where they were able to socialize in “a nice environment ... cool” and “air-conditioned.” Several research participants noted gambling venues also provided affordable services including “access to cheap drinks”, “a cheap meal” and sometimes, free transport. This was relevant “for older people [who] don’t have a lot of public transport.” People tended to avoid venues where they were “constantly getting nagged” for loans. Some gamblers were described as “borrowing from one another ... starts in-fighting in families because you borrow ... to go out and gamble and then you’ve lost it and can’t pay it back. Then families don’t talk to each other.” Socializing and gambling in venues that were physically comfortable and accessible were popular with some Indigenous gamblers.

In contrast, most participants reported several prominent negative consequences of Indigenous gambling. These included financial hardship, family and relationship difficulties, and the spread of negative impacts throughout the community. To a lesser extent, other negative consequences were seen as mental health problems and crime.

Financial hardship was mentioned by almost everyone as a major negative consequence of gambling. One participant said “the biggest one is debt” and then “they just don’t tell anybody” because they feel “embarrassed about exposing how much they spend.” Another participant reflected on their own circumstances: “from my work ... my own life ... and my family experience, I know people are struggling with debt because of gambling.” Financial hardship appeared to have an accumulating effect starting with a gambling loss by “spend(ing) the rent money”, which might eventually lead to “eviction” sometimes to “homelessness” and having “to rely on a refuge or family” which can be “overcrowded.” For others “having bills not paid” sometimes led to “utilities cut off” which meant some people “were eating poorly with low nutrition and fast food.” Lacking essential daily items and having “no food at home” meant parents “cannot meet basic needs, affecting ability to be good parents, child neglect, abuse of kids as a result of stress over losses, no formula for the baby.”

Family difficulties also had an accumulating effect. The “stress on relationships” caused by gamblers who “lie to their family about their bank accounts, credit cards” can lead to other difficulties. These difficulties were said to include “child neglect”, “arguments”, “domestic violence” and “family break-ups.” One person believed gambling “destroys people’s social life, especially with family, as the gambler is always absent from home.” Another participant observed “you see kids sitting in cars outside the club” with no one supervising or “supporting children.” In some cases, cultural roles took over “aunties and uncles step in and look after kids, share in the cycle of care.”

Relationship problems were said to arise from negative gambling-related consequences. For instance, a person “might not know their partner has a problem until they get evicted from home due to not paying rent.” “Arguments and anger over losing money” were seen as “leading to family breakdown.” Some participants mentioned conflict arising when “people don’t have a win, they just blow their money, and they start taking it out on the missus.”

Negative consequences could spread into the Indigenous community where some gamblers were seen as “poor role models” for others. This might lead to a “loss of cultural values or true values” which “affects the whole community.” One participant’s sister who had visitors (gamblers) constantly staying at her home said they bring “alcohol, not groceries, no payments, but they help each other out.” Such sharing and reciprocity is a traditional feature of Indigenous Australian society. Exploitation was said to occur when a few gamblers demanded money by using these reciprocal expectations of sharing to extract money for gambling. They obtained resources by “standing over other people for money.” One person lamented “gambling is controlling our people rather than us controlling gambling.”

Mental health problems were seen by some participants as a consequence of gambling. One person considered that gambling losses “affect self-esteem and mental health.” Mental health problems mentioned included “depression”, “a self-destructing cycle”, “addiction” and “suicidality.” For a few people “gambling becomes an addiction and it becomes controlling” and “people can get that desperate, suicide is an option.” Some spoke of poker machine gambling as being addictive, for example:

We talk about the boredom and trying to get a quick fix but after a while it’s kind of, it’s addictive. You’re addicted to it. I’m not a gambler but I can just imagine it’s like opal, mate. People see opal in their mind, they want a big strike.

Crime linked to gambling was often reported to be “theft” and “stealing” where “desperation leads to crime.” Some gamblers were said to resort to “selling their items and other people’s for money.” Others had been found “ripping off their workplace.”Footnote 6 For example, one gambler “had a really bad gambling problem. She started ripping off (her employer) and got caught big time. She ripped off (her employer) to feed her gambling problem.” A generational issue was raised by two participants who commented that “stealing food and money, gambling and drinking gets transferred to kids as they watch that behavior” with “(gambling) leading to stealing and crime by kids if they are hungry and not supervised.”

Discussion

The purpose of this article was to examine and explain Indigenous gambling behaviours, motivations and consequences in northern New South Wales. Drawing together these thematic results and taking into consideration that gambling behaviour can be seen as ranging from healthy to unhealthy on a public health continuum (Korn and Shaffer 1999) these results reveal a variety of healthy and unhealthy gambler behaviours, motivations and consequences.

The majority of gamblers were reported to gamble mainly for social reasons and to win money while using low stakes. About once a week of fortnight they gamble in small groups with family and friends, sometimes pooling their money. They usually gamble for a few hours and prefer to gamble on poker machines and bingo in local venues. Preferred venues are those where facilities are comfortable, access is easy and Indigenous people are treated equally. Women appear to gamble more on poker machines and cards while men appear to prefer TAB gambling. Bingo players and card gamblers are mostly women who gamble for recreation and relaxation with family and friends.

On the contrary, a minority of gamblers were reported to be frequent, heavy gamblers who gamble for long sessions whenever they have money. They usually gamble until their money is exhausted and often seek loans to continue. Some call on cultural reciprocity to borrow. Gambling duration depends on their wins, losses and loans. They always gamble to win money. Their gambling peaks on payday. These gamblers include both women and men. They usually play as individuals, although they might be loosely connected to a social group.

Common positive aspects of gambling reported among the respondents included socialising, connectedness, enjoyment, comfort and an opportunity to win money, although it is noted that little card gambling was reported overall. These motivations and consequences of gambling align with those found in prior research, where both card and commercial gambling have been reported to be enjoyable leisure and recreation activities for many Indigenous Australians (AHMRC 2007; McMillen and Togni 2000). For example, McDonald and Wombo (2006) reported that card gambling provides social interaction, leisure opportunities and financial benefits for winners and that commercial gambling is mostly perceived as a social activity with positive outcomes. Paterson (2007) asserted that card and commercial gambling are mostly social activities and only perceived as problematic when gambling becomes individuated, including gambling by oneself and in a secluded place alone. Some gambling in venues, Foote (1996) observed, encourages social interaction, particularly where stakes are pooled and gambling winnings are shared. McMillen and Togni (2000) reported that most Indigenous gamblers do not appear to experience problems with commercial gambling. In addition, Breen (2010) found in north Queensland that many social gamblers were drawn together by the enjoyment they get from socialising and gambling together.

In contrast, common negative aspects of gambling arising from frequent, intensive gambling included solo gambling, long sessions, high expenditures, chasing losses, motivations to always win money, financial hardship, family difficulties, relationship problems, extended negative community impacts, exploitation of vulnerable others, mental health issues and crime. Financial hardship is usually the first crisis most gamblers confront when they spend more money than they can afford at gambling. Financial hardship, particularly chasing losses, accumulating debts and borrowing money, was recognised for Indigenous commercial gambling by the Queensland Department of Families, Youth and Community Care (1996), Dickerson et al. (1996) and Young et al. (2006), and for Indigenous card gambling by Hunter (1993) and Hunter and Spargo (1988). These characteristics were also displayed by a small group of frequent gamblers in the current study. The ripple effects of financial hardship were described by Phillips (2003) as affecting those closest to the gambler (their family) and then those around them (community members). The current study also found that financial hardship suffered by these gamblers could permeate into their community.

Family and relationship problems arising from negative gambling consequences included child neglect, domestic violence and abuse and relationship breakdowns. Ignoring children while gambling was identified in previous Indigenous-focused research as being neglect of children’s physical, emotional and psychological welfare (Hunter 1993; McDonald and Wombo 2006). In New Zealand, Schluter et al. (2007) found that household food and shelter problems were related to gambling by young Pacific Island mothers living in Auckland. These young mothers were supporting children on their own and gambled to supplement their social security payments and fund everyday activities. Gambling losses led to some being unable to provide the essential needs of children. Children suffered through poor nutrition and parental absence, with far-reaching consequences for their development.

For some gamblers who lost all their funds at gambling, domestic violence was a consequence. This situation was described earlier by Phillips (2003:68) as “men blame women’s gambling for their drinking, and women blame men’s drinking or marijuana use for their gambling.” As an outcome of gambling, domestic violence was found in north Queensland resulting in some family dysfunction and relationship breakdown (Breen 2010).

Exploitation of people and organisations was also reported as a negative consequence of gambling by Martin (1993) in north Queensland. Exploitation of people was “relentless pressure” (Martin 1993:106) to provide gambling money or resources. Also in north Queensland, Breen (2010) identified a group of disadvantaged, disabled, less experienced or more naïve gamblers who were invited to join card games and/or were humbugged for their winnings by other gamblers.Footnote 7 This pressure often constituted an abuse of traditional Indigenous reciprocity. Exploitation of organisations was more likely to be theft and fraud. In either case Indigenous people and their organisations suffered from these negative consequences of gambling.

These results represent people with gambling behaviours, motivations and consequences that range all along a gambling continuum from no risk of harm up to significant risk, as explained by the Productivity Commission (2010) and Korn and Shaffer (1999). While reports in this research suggest that the majority of these Indigenous gamblers are social gamblers, sitting towards the healthy end of the continuum, there is evidence that other gamblers sit at all points along the continuum with increasing risk severity, leading towards those who are at significant risk with their gambling.

Conclusion

In this article we have presented an explanation of Indigenous gambling behaviours, motivations and consequences in northern New South Wales. Gambling is a complex topic and this research has presented a range of contrasting social or recreational gambling and more problematic gambling behaviours, motivations and consequences. These findings and interpretations raise public health concerns. Well-planned, evidence-based public health prevention and harm reduction programs are designed to assist in maintaining recreational gambling and reducing problematic gambling. However governments, public health experts, gambling help services and counsellors need to be aware of the needs of smaller groups in the population, such as Indigenous gamblers and especially those exhibiting more problematic gambling behaviours, to ensure that appropriate services are available. For these gamblers, culturally appropriate gambling treatment is a necessity to address their particular needs. Gambling industries could develop more culturally appropriate harm minimisation and consumer protection measures. It is hoped that this research has provided a useful platform from which such actions can proceed.

However, some limitations of the research must be noted. While the sample size was large for a qualitative study, it was not representative of the population, due to snowball sampling and the voluntary participation of interviewees. In addition, the sensitive topic of the research may have yielded some social desirability bias. While limited to one region additional research could compare these findings with other regions in Australia and other nations to tease out other characteristics and explore fine differences. Further, the use of quantitative methods to investigate this topic would allow for generalisability of results. This would be useful for encouraging and promoting more social rather than intensive gambling behaviour from a public health perspective.

Notes

The authors are aware of the debate around titles used to describe Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Alternative terms such as Indigenous, Aboriginal, Koori and Murri are in common use. In this literature review, we use the terms Indigenous Australian and Aboriginal interchangeably.

All money references are in Australian currency.

Yarn is a colloquial word for story or anecdote (research participant).

Poker machines are also called electronic gaming machines, gaming machines, pokies or slots depending on source or use in that particular jurisdiction. TAB or Totalisator Agency Board is the name of an agency which operates a computerised system of betting calculating all bets and pay outs in a pari-mutuel style (McPherson 2007).

A press is a colloquial word for gambling on a poker machine (research participant).

Ripping off is a colloquial term for theft or fraud (participant response).

Humbug is a commonly used colloquial Indigenous word for harassment and pestering people for money with the expectation of receiving it (McDonald and Wombo 2006).

References

Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council of NSW (AHMRC). (2007). Pressing problems, gambling issues and responses for NSW Aboriginal communities. Sydney: AHMRC of NSW.

ACIL Tasman Consulting. (2006). The economic impact of gambling on the Northern Territory. Darwin: Charles Darwin University.

Altman, J. (1985). Gambling as a mode of redistributing and accumulating cash among Aborigines: A case study from Arnhem Land. In G. Caldwell, B. Haig, D. Sylvan, & L. Sylvan (Eds.), Gambling in Australia (pp. 50–67). Sydney: Croom Helm.

Atkinson, J. (2002). Trauma trails recreating songlines: The transgenerational effects of trauma in indigenous Australia. Melbourne: Spinifex Press.

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). (2002). Guidelines for ethical research in Indigenous studies. Canberra: AIATSIS.

Borrell, J. (2008). A thematic analysis identifying concepts of problem gambling agency: With preliminary exploration of discourses in selected industry and research documents. Journal of Gambling Issues, 22, 195–218.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

Breen, H. (2008). Visitors to Northern Australia: debating the history of indigenous gambling. International Gambling Studies, 8(2), 137–150.

Breen, H. (2010). Risk factors and protective factors associated with Indigenous gambling in North Queensland. Doctoral dissertation, Southern Cross University, Lismore, Australia.

Breen, H., Hing, N., & Gordon, A. (2010). Exploring indigenous gambling understanding indigenous gambling behaviour, consequences, risk factors and potential interventions. Report prepared for Gambling Research Australia. Lismore, Australia: Centre for Gambling Education and Research, Southern Cross University.

Christie, M., & Greatorex, J. (2009). Workshop report, regulated gambling and problem gambling among aborigines from remote Northern territory communities: A Yolgnu Case Study. Darwin: Charles Darwin University.

Creswell, J. (2007). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Cox, B., Yu, N., Afifi, T., & Ladouceur, R. (2005). A national survey of gambling problems in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 50(4), 213–217.

Cultural Perspectives Pty. Ltd. (2005). Problem gambling research report for Indigenous communities. Melbourne: Victorian Department of Justice.

Dickerson, M., Allcock, C., Blaszczynski, A., Nicholls, B., Williams, J., & Maddern, R. (1996). A preliminary exploration of the positive and negative impacts of gambling and wagering on Aboriginal people in NSW. Sydney: Australian Institute of Gambling Research.

Foote, R. (1996). Aboriginal gambling: A pilot study of casino attendance and the introduction of poker machines into community venues in the Northern Territory. Darwin: Centre for Social Research, Northern Territory University.

Geertz, C. (1983). Blurred genres: The reconfiguration of social thought. In C. Geertz (Ed.), Local knowledge: Further essays in interpretive anthropology (pp. 19–53). New York: HarperCollins.

Goodale, J. (1987). Gambling is hard work: Card playing in Tiwi society. Oceania, 58(1), 6–21.

Guba, E., & Lincoln, Y. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Gubrium, J., & Holstein, J. (2000). Analysing interpretive practice. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 487–508). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Hepburn, R., & Twining, C. (2005). Be with us feel with us act with us: Counselling and support for Indigenous carers. Melbourne: Carers Victoria.

Hunter, E. (1993). Aboriginal health and history, power and prejudice in remote Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hunter, E., & Spargo, R. (1988). What’s the big deal? Aboriginal gambling in the Kimberley region. The Medical Journal of Australia, 149, 668–672.

Jennings, G. (2001). Tourism research. Brisbane: Wiley.

Korn, D., & Shaffer, H. (1999). Gambling and the health of the public: Adopting a public health perspective. Journal of Gambling Studies, 15(4), 289–365.

McDonald, H., & Wombo, B. (2006). Indigenous gambling scoping study—Draft report. Darwin: Charles Darwin University.

McGowan, V., & Nixon, G. (2004). Blackfoot traditional knowledge in resolution of problem gambling. Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 24, 7–35.

McMillen, J., & Donnelly, K. (2008). Gambling in Australian Indigenous communities: the state of play. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 43(3), 397–426.

McMillen, J., & Togni, S. (2000). A study of gambling in the Northern Territory 1996–97. Sydney: Australian Institute of Gambling Research.

McPherson, J. (2007). Beating the odds, the complete dictionary of gambling and games of chance. Melbourne: GSP Books.

Martin, D. (1993). Autonomy and relatedness: An ethnography of Wik people of Aurukun, Western Cape York Peninsula. Doctoral dissertation, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia.

Martin, K. (2008). Please knock before you enter, Aboriginal regulation of Outsiders and the implications for researchers. Brisbane: Post Pressed.

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). (2003). Values and ethics: Guidelines for ethical conduct in aboriginal and torres strait islander health research. Canberra: NHMRC.

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). (2007). National statement on ethical conduct in human research. Canberra: NHMRC.

Paterson, M. (2007). The regulation of ‘unregulated’ Aboriginal gambling. In G. Coman (Chair), 17th Annual National Association for Gambling Studies Conference. Cairns, QLD, Australia, November.

Patton, M. (1990). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Petry, N., Stinson, F., & Grant, B. (2005). Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: results from the national epidemiologic survey of alcohol and related conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 665, 564–574.

Phillips, G. (2003). Addictions and healing in Aboriginal Country. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Productivity Commission. (1999). Australia’s Gambling Industries. Inquiry Report No. 10. Canberra: Ausinfo.

Productivity Commission. (2009). Gambling draft report. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

Productivity Commission. (2010). Gambling, Inquiry Report, No. 50. Canberra, Australia: Productivity Commission.

QSR International. (2008). QSR V.8. Melbourne: QSR International Pty. Ltd.

Queensland Department of Families, Youth and Community Care. (1996). Long term study into the impact of gaming machines in Queensland: An issues paper: The economic and social impact of gaming machines on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities in Queensland. Brisbane: Australian Institute for Gambling Research, University of Western Sydney and the Labour and Industry Research Unit, University of Queensland.

Government, Q. (2005). Queensland household gambling survey 2003–04. Brisbane: Queensland Treasury.

Government, Q. (2008). Queensland household gambling survey 2006–07. Brisbane: Queensland Treasury.

Schluter, P., Bellringer, M., & Abbott, M. (2007). Maternal gambling associated with families’ food, shelter, and safety needs: findings from the Pacific Island families study. Journal of Gambling Issues, 19, 87–90.

Shaffer, H., & Korn, D. (2002). Gambling and related mental disorders: a public health analysis. Annual Review of Public Health, 23, 171–212.

Spradley, J. (1980). Participant observation. Forth Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

Steane, P., McMillen, J., & Togni, S. (1998). Researching gambling with Aboriginal people. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 33(3), 303–315.

Volberg, R. (2004). Fifteen years of problem gambling prevalence research: What do we know? Electronic Journal of Gambling Issues: eGambling, 10, February, no paginated.

Young, M., & Stevens, M. (2009). Reported gambling problems in the Indigenous and total Australian population. Melbourne: Gambling Research Australia.

Young, M., Barnes, T., Morris, M., Abu-Duhou, I., Tyler, B., Creed, E., et al. (2006). Northern Territory Gambling Prevalence Survey 2005. Darwin: Charles Darwin University.

World Health Organization (WHO). (1986). Health Promotion: a discussion document on the concepts and principles. Health Promotion, 1(1), 73–76.

Wynne, H., & McCready, J. (2005). Examining gambling and problem gambling in Ontario aboriginal communities. Ontario: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank the Indigenous people of northern New South Wales for their generous cooperation and collaboration with this research project.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the data, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This project and subsequent authorship of this article was funded by Gambling Research Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The researchers have full control of the primary data and it can be reviewed if requested by the journal editor.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Breen, H.M., Hing, N. & Gordon, A. Indigenous Gambling Motivations, Behaviour and Consequences in Northern New South Wales, Australia. Int J Ment Health Addiction 9, 723–739 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-010-9293-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-010-9293-2