Abstract

In culturally diverse and immigrant receiving societies, immigrant youth can be subject to prejudice and discrimination. Such experiences can impact on immigrant youth’s cultural identity and influence their psychosocial outcomes. This paper presents findings of a study that examined cultural identity and experiences of prejudice and discrimination among Afghan (N = 9) and Iranian (N = 17) immigrant youth in Canada. The study had a prospective, comparative, longitudinal qualitative design. Data was gathered through focus groups, interviews, journals and field logs. Four main themes emerged on participants’ experiences of prejudice and discrimination: (a) societal factors influencing prejudice; (b) personal experiences of discrimination; (c) fear of disclosure and silenced cultural identity; and (d) resiliency and strength of cultural identity. Drawing from Rosenberg’s (Conceiving the self, Basic Books, New York, 1979) self-concept framework and Romero and Roberts (J. Adolesc., 21:641–656, 1998) distinction between prejudice and discrimination, results indicated that youth’s extant and presenting cultural identity were affected. Inclusive policies and practices are needed to promote youth integration in multicultural and immigrant receiving settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Prejudice and discrimination in post-migration contexts can impact on the cultural identity of immigrant youth. Such experiences can also shape the settlement, integration and sense of belonging of newcomer youth. Different immigrant groups can experience varying degrees of prejudice and discrimination in their countries of settlement, which often are influenced by broader historical and contextual factors, that can ultimately influence their cultural identity and acculturation process (Jasinskaja-Lahti et al. 2003; Phinney et al. 2001, 2006). Adolescent attitudes towards the larger society can range in strength from a positive sense of belonging to feelings of exclusion (Phinney and Devich-Navarro 1997). This paper critically examines the experiences of prejudice and discrimination among a group of Afghan and Iranian immigrant youth in Toronto, Canada. The findings emerged as part of a prospective longitudinal study entitled “Immigrant Youth and Cultural Identity in a Global Context”. The overall study explored the relationships between cultural identity and self-esteem of youth from traditional and new source countries of immigration to Canada; the focus of this paper is on the youth participants from new source countries.

Prejudice and Discrimination and Mental Health

Romero and Roberts (1998) distinguish between notions of ethnicity and culture, and prejudice and discrimination. They suggest that an ethnic group can be defined as a group in which members have a similar social heritage, and that culture is a more inclusive concept. According to Romero and Roberts, prejudice describes negative attitudes toward out-groups and discrimination describes negative behaviours toward out-groups. These negative beliefs and attitudes about out-groups may lead individuals to categorize and reject groups of people resulting in social inequity and differential opportunities and rights (Romero and Roberts 1998). Researchers have acknowledged discrimination and social exclusion to be increasing and a part of daily life for many minority ethnic youth (Anisef and Kilbride 2003; Galabuzi 2002). Further, prejudice and discrimination may negatively affect the process of settlement and integration of youth into multicultural societies (Anisef and Kilbride 2003).

There is a growing body of research examining the relationships between perceived discrimination, mental health and well-being, and ethnic/racial identity of immigrant youth populations (DuBois et al. 2002; Jakinskaja-Lahti and Liebkind 2001; Phinney and Devich-Navarro 1997; Shrake and Rhee 2004; Verkuyten 2002; Yoo and Lee 2005). However, studies present contrasting views suggesting that perceived discrimination can lead to both negative and protective psychosocial outcomes.

The negative psychosocial effects of perceived discrimination by ethnic minority groups have been documented. Theoretical perspectives in social psychology, such as the social identity theory, indicate that experiencing prejudice and discrimination will have damaging effects on self-esteem (Tajfel and Turner 1986). In turn, experiences of prejudice and discrimination are major factors contributing to stress during the acculturation process (Berry and Sam 1997). Some studies in Canada and the United States found negative physical and psychological health outcomes, such as elevated stress, lowered self-esteem, depression and behavioural problems (e.g. violence and drug use) related to perceived discrimination and experiences of racism (Dubois et al. 2002; Noh et al. 1999; Surko et al. 2005). International studies also provide support for the negative impacts of perceived discrimination on psychosocial well-being (Jasinskaja-Lahti et al. 2006; Liebkind and Jasinskaja-Lahti 2000).

The literature also suggests relationships between perceived discrimination and in-group, out-group ethnic identification. High ethnic identification may be predictive of the perception of more discrimination by out-groups (Romero and Roberts 1998). In addition, perceptions of discrimination may strengthen immigrant identification with their own ethnic group (Branscombe et al. 1999; Schmitt et al. 2002), which in turn may provide the social support and sense of belonging needed to buffer the negative effects of perceived discrimination (Crocker and Major 1989; Phinney 1990). Further, research has indicated that when faced with negative treatment from others, people often discount those experiences in order to protect their self-esteem (Branscombe et al. 1999). Strong ethnic identification may subsequently weaken ties to the national group (Phinney et al. 2006). However, a stronger sense of belonging to one’s ethnic group can also be associated with more positive attitudes towards out-groups (Romero and Roberts 1998).

Several studies have examined ethnic identity in multi-ethnic contexts (Phinney et al. 2006; Verkuyten 2002; Verkuyten and Martinovic 2006). One study investigated perceptions of personal and group discrimination among ethnic majority and minority group in early adolescents (ages 10–12 years) living in a multi-ethnic context of the Netherlands (Verkuyten 2002). All adolescents reported more group than personal discrimination. This phenomenon was found to exist independent of ethnic identity. However, minority group participants (Turkish youth) perceived significantly more discrimination overall than majority group early adolescents (Dutch youth) and reported significantly more discrimination to be directed at in-group members than at themselves. Recent work by Verkuyten and Martinovic (2006) investigated youth’s attitudes toward multiculturalism by examining ethnic majority and minority group adolescents in the Netherlands. The endorsement of multiculturalism was examined in relation to in-group identification, perceived structural discrimination, out-group friendships and ideological notions of communalism and individualism (Verkuyten and Marinovic 2006). Ethnic minority group participants were found to be much more in favour of multiculturalism than the majority group.

Immigrant Youth’s Cultural Identity

Experiences of prejudice and discrimination can influence the cultural identity and sense of belonging of immigrant youth. In the context of immigration and acculturation studies, Berry et al. (2006) have examined immigrant youth populations across and within various national contexts. The concept of cultural identity is located under the field of acculturation as a broad concept that refers to the “changes that take place following intercultural contact” (Phinney et al. 2006, p. 71). Acculturation plays an important role in how well immigrant youth adapt both psychologically and socio-culturally (Phinney et al. 2006). Although most youthFootnote 1 face the challenges of developmental transitions, immigrant youth may be exposed to additional challenges due to their intercultural status (Anisef and Kilbride 2000; Phinney et al. 2006). Research related to cultural identity of immigrants primarily addresses ethnic identity, with less focus on their identification with their national identity. Ethnic identity is the degree of one’s sense of belonging and attachment to one’s group, and national identity is a broader construct involving feelings of belonging to and attitudes toward the larger society (Phinney et al. 2006). The concept of cultural identity is more inclusive of the diversity of identities through which adolescents can define themselves, including ancestral, national, hyphenated, racial and migrant identities (Khanlou and Crawford 2006). Cultural identity is recognized “as a component of the identity of an individual who through living in a multicultural context, where as a member of a major or a minor group, and through daily contact with other cultures, is aware of the cultural component of the self” (Khanlou 1999, p. 5). This contextual conception implies cultural identity manifests itself in the presence of culturally different other(s).

Global valuation can play an important role in exploring the cultural identity and acculturation of immigrant youth. The concept of global valuation emerged from a study of cultural identity and self-esteem among Canadian-born and immigrant youth (Khanlou 1999, 2004). Global valuation is defined as the prevailing societal-esteem of a particular cultural group; it entails how that group is judged by the post-migration society as well as levels of exposure to it (for example through mass media). Historical relationships between the particular cultural group with others as well as its present status in global political and economic structures influence this judgment. The concept implies that a cultural group’s current global valuation will influence both youth’s level of identification with that group and their self-esteem. Global valuation can influence experiences of identity during the immigration, resettlement and acculturation process. It is therefore important to consider the influence of prejudice and discrimination on cultural identity and sense of belonging of youth in multicultural settings while contextualizing the findings within current global trends.

There is limited but growing research examining the cultural identity of immigrant youth within multicultural contexts. However, there is a paucity of research exploring the cultural identity of Afghan and Iranian groups. In addition, research has predominantly examined the ethnic identity of adults, with limited attention on children and adolescent populations (Sam 2000). This study focused on cultural identity, as it is an important aspect of identity (Khanlou 2005; Phinney 1990), and recognized it as a psychosocial construct.

Changing Demographics in Canada

The demographics of multicultural contexts such as Canada are changing. Canada has the second largest proportion of foreign-born individuals in the world after Australia (Statistics Canada 2003). In the 2001 census, Canadians listed more than 200 ethnic groups in response to their ethnic ancestry (Statistics Canada 2003). The Canadian Council of Social Development reported that youth immigrants (between the ages of 15–25) are one of the fastest growing populations in Canada (Kunz and Harvey 2000). In turn, the highest source countries of youth (15–24 years) migrating to Canada are from Asian and Pacific countries (49.7%) and Africa and the Middle Eastern countries (23.1%; Citizenship and Immigration Canada 2004). Among those from the Middle East, Iran was identified as one of the top five source countries immigrating to Canada (Citizenship and Immigration Canada 2002).Footnote 2 The Iranian community is a relatively new component of Canada’s immigrant population, making up less than 2% of Canada’s immigrant populationFootnote 3, however, immigration from Iran has increased in recent years. Afghanistan is also among the top ten source countries of immigration to Canada (Citizenship and Immigration Canada 2004). In the midst of the on-going political conflict in Afghanistan upwards of 5 million Afghan refugees fled directly to Pakistan, India, and Iran. Therefore, most refugees from Afghanistan came to Canada by way of third countries (Kelly and Trebilcock 1998; Norquay 2004). The vast majority of Afghans in Canada are first-generation immigrants; however, there is a small percentage of second-generation Afghan youth (Norquay 2004). In light of these changing trends and global context, it is important to consider the cultural identity of Afghan and Iranian youth to gain better insight of their integration into multicultural and immigrant receiving settings.

Purpose of Study

The existing body of research indicates that perceived discrimination can negatively affect mental health and self-esteem, while also strengthening one’s sense of belonging to one’s ethnic/racial identity. Few studies were found that investigated cultural identity related to multicultural contexts and global valuation. The majority of studies reviewed focused on racial and ethnic identities, which may be narrower concepts than cultural identity. In addition, few studies explored the experiences of discrimination by youth. Of the studies reviewed, several were conducted in the USA, with a focus on specific racial groups such as African-American, Hispanic, and Asian youth. There is limited work examining discriminatory experiences of youth and cultural identity in Canada in general, and of Afghan and Iranian youth in particular. To address this knowledge gap, the current study explored the experiences of cultural identity among Afghan and Iranian youth living in a multicultural context. The study utilized Rosenberg’s (1979) theoretical framework on self-concept and Romero and Robert’s (1998) definitions of prejudice and discrimination (discussed further in the analysis). It also considered the influence of global valuation and its influence on cultural identity and experiences of prejudice and discrimination.

Method

Sample Population and Procedures

The “Immigrant Youth and Cultural Identity in a Global Context Project” (IYCIP) had a prospective, comparative, longitudinal design and employed a range of quantitative and qualitative data gathering methods. This mixed methodological approach enabled an in-depth exploration of immigrant youths’ experiences of migration, cultural identity and self-esteem. Ethics approval for the study was received from the university Research Ethics Board. The sample population consisted of English speaking youth who were immigrants or descendants of immigrants and were between 17 to 22 years of age. A two-part non-random sampling method was utilized. The first stage used snowball sampling and the second stage used purposive sampling to ensure diversity along the key dimensions of the study, including gender (female and male), source country of immigration (traditional source countries: Italy, Portugal and new source countries: Afghanistan, Iran), and family social status (education level of parents/ significant caretakers). The selected attributes of diversity can have a significant influence on post-migration settlement experiences (Anisef and Kilbride 2003; Beiser 1988; Khanlou et al. 2002). The first step of participant sampling involved identifying potential community partners and sources through the extensive network of community-based agencies through the Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants as well as collaborative networks of the study researchers. Contact was made with key cultural community groups through distributing user-friendly posters and through other recommended community venues, such as on-line cultural group list-serves. As potential participants were identified, the second step used a purposive sampling technique in relation to the inclusion criteria outlined above (Burns and Grove 2001).

Data Collection

Data collection was achieved through focus groups, interviews, journals, self-esteem questionnaire, and youth focus group evaluations. In addition, notes were taken during the meetings and an on-going field log was maintained over the course of the study. Prior to the first focus group session with each cultural group, a pre-focus group session was held to describe the project and attain informed consent (Khanlou and Peter 2005). Four focus group meetings were held with each cultural group (Afghan, Iranian, Italian, and Portuguese), resulting in 16 focus group sessions. Meetings were held every two to three months over a 1-year period. In-depth interviews were also conducted, individually, with two members (one male and one female) from each cultural group to further explore issues raised during focus group sessions. A total of nine interviews were conducted. Participants were requested to keep an optional journal (diary) for the study’s duration and to write about any issues which they believed were important in relation to cultural identity and self-esteem. Twenty-one of the 45 study participants (47%) completed journals over the course of the study.

Analysis and Rigor

The qualitative data analysis was a collaborative and iterative process, with text being approached dialectically as a whole, and particular parts in relationship to each other. Data came from four sources: focus groups; interviews; field notes kept by researchers; and, journals written by participants. The process began with reading focus group transcripts as they were completed for each cultural group, followed by readings of interview transcripts and finally participant journals. All data sources were read several times. Each member of the team independently compiled a list of themes and sub-themes from the transcripts. Using a process similar to Wilms and Johnson (1990), themes and sub-themes were both descriptive (code driven) and interpretive (context driven). These lists were then discussed and compared and one central working list was created. From this initial working list, a conceptual framework was drafted. The conceptual framework offered a way to account for all the themes and sub-themes and the relationships between them and was used to schematically represent the overall final analysis (Earp and Ennett 1991). Both the list and the conceptual framework were used as guideposts for interpretations, and in turn, the interpretations informed further revisions to the list and the conceptual framework. Triangulation was the next stage in which analyses from all data sources were combined into one comprehensive summary for each cultural group. All four cultural group summaries (that included quotes and interpretations from all four data sources) were incorporated into a final conceptual analysis of themes.

Trustworthiness was addressed in this study through several simultaneous processes. Triangulation of data collection methods and sources, as well as investigators, was implemented in order to minimize the risk of losing an objective perspective from which to make interpretations and ‘holistic fallacy’ (Sandelowski 1986, p. 32). Two of the three approaches to triangulation described by Farmer et al. (2006, p. 379) were used. They were intuitive, meaning each member of the research team intuitively related information from focus groups, interviews and journals to each other, and inter-subjective, in which the team reached agreement about the common themes across all data sources by meeting regularly to discuss information from each of the three sources. The trustworthiness of the final analysis itself is grounded in the reflexivity of the investigators, an interactive process of thinking and dialoging, and made explicit through the documentation of personal ideas and reactions to the text as we read it as well as through the detailed notes made for each of the team meetings. Member checking, or the practice of returning to the participants of a study to validate the researchers’ taxonomies and adequacy of analysis (Murphy et al. 1998), was also utilized in this project. At the final focus group session with each cultural group, the themes and sub-themes arising from the transcripts of that group were presented to participants. This allowed an opportunity for participants to give feedback in two ways: by their comments on the adequacy of themes in capturing the key ideas discussed as the participants remembered them and, clarification of intended meanings, and any cultural translations or words to verify for the researchers’ understanding.

Additional analysis was conducted using Romero and Roberts (1998) definition, which distinguishes between prejudice (negative attitudes) and discrimination (negative behaviours) as well as Rosenberg’s (1979) framework on self-concept. Rosenberg defined self-concept as “the totality of the individual’s thoughts and feelings with reference to himself as object” (p. ix). He also recognized three aspects of the self including: extant, desired and presenting self-concept. The extant self-concept relates to how one sees oneself; the desired self-concept is how one would like to see oneself; and the presenting self-concept is how one shows oneself to others (Rosenberg 1979). Across all data sources, participants reported experiences of prejudice and discrimination that impacted their internal experiences (recognized here as their extant cultural identity—ECI) and external expressions (recognized here as their presenting cultural identity—PCI).

Results

Sample Profile

The study sample included a total of 45 youth who were immigrants or descendants of immigrants from traditional and more recent source countries of immigration to Canada. Traditional immigration source countries included Italian (N = 11) and Portuguese (N = 8) youth. Recent immigration source countries included Afghan (N = 9) and Iranian (N = 17) youth. The focus in this paper is on the latter group of youth.

Table 1 presents demographic information of the participants. The Afghan group consisted of first generation immigrant youth between the ages of 18 to 21 yearsFootnote 4. The majority were university students, and on average had been in Canada for seven years. Due to the political turmoil and war in Afghanistan over the last few decades, many of the participants had migrated to Canada from other countries, such as Germany, Iran and Pakistan. Three of the eight participants had never been to Afghanistan because their families fled to escape the war before they were born. A total of four focus group sessions and two interviews were conducted and four journals were completed by Afghan youth over the course of the study. Participants in the Iranian group consisted of youth from the ages of 17 to 20, who had completed either grade 11 or 12 of high school and were all living with family. The Iranian youth had been in Canada for the least amount of time, ranging from 7 months to 2.5 years. A total of four focus group sessions were held with the Iranian group. In addition, three interviews were conducted with two Iranian females and one male. A total of seven Iranian participants completed journals over the course of the study.

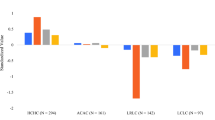

Four main themes emerged from the subset of project data on participants’ experiences of prejudice and discrimination in Canada. The first two themes relate to influences on youth’s internal experiences (ECI) through (a) societal factors influencing prejudice, and (b) personal experiences of discrimination. The last two themes relate to youth’s external expressions (PCI) through (a) fear of disclosure and silenced cultural identity, and (b) resiliency and strength of cultural identity. Fig 1. illustrates the relationships between youth’s internal experiences (ECI) and youth’s external expressions (PCI) and how they can influence cultural identity. There is the potential for diverse pathways in which both internal and external factors may combine to affect and can be affected by youth’s cultural identity.

Youth Experiences of Prejudice and Discrimination

Societal Factors Influencing Prejudice

Participants in both groups discussed experiencing prejudicial attitudes regarding world events in the Middle East and religious faiths, as a result of the geopolitical events related to ‘9/11’ and the on-going war in Afghanistan. Afghan youth talked more about these issues than Iranian youth, and males typically dominated these conversations in both groups. Media influence and misrepresentation emerged as a sub-theme from the societal factors influencing prejudice. In turn, media influenced youth’s ECI, shaped through their experiences of prejudice.

Media Influence and Misrepresentation

The power and influence of media in various forms such as TV, radio, newspaper, movies, and marketing advertisements were continually referenced by most of the participants. Focus group discussions did little to present media as a positive influence on their cultural identity. The majority of examples by participants related to broader systemic prejudice depicted through the media as both shaping and reflecting culture. One Iranian youth described the media’s powerful influence on mainstream attitudes about other cultures:

News is the one that everyone watches for it and newspapers are the one everyone reads. People don’t come to me and ask me what is your culture.....news is the one that everyone listens to and everyone believes in it. Everyone believes that the truth comes from the news (18 year old, Iranian male).

More specifically, Afghan participants discussed how negative media portrayal of their culture and of Muslims in general fueled prejudice about their culture and religion within other countries. These youth reported that false representations of their culture not only affected how others viewed them as individuals, but how they viewed themselves. One participant reported that:

We are from that country, we are from that religion and when we see it being discriminated so negatively on TV it affects us. So it rubs off on society, I mean,... now these youth... they watch TV and it has an effect on them and then... they may stereotype you because they have seen whatever on TV (18 year old, Afghan female).

Participants also spoke directly of media misrepresentation that led to “unfair judgment” of their culture and saw little critical reflection on Western involvement and global issues surrounding the war, but rather a general adoption that Afghan culture is simply “wrong”. A number of participants provided specific examples of experiencing prejudice through ignorance. One participant related the misrepresentation of the media to prejudiced societal attitudes that led people to associate her identity with Osama Bin Laden or having “links to terrorist groups” (19 year old, Afghan female).

Iranian participants also reported that the media perpetuated stereotypes of their culture and misrepresented information by referring to “Persian” and “Iranian” interchangeably (18 year old, Iranian male). One participant suggested that the media intentionally misrepresented and portrayed their culture negatively, as he reported “...I really don’t understand why when they want to present Iran, or the Middle East, on the news... they go and find the worst piece of news... and they go ahead and play it,” (18 year old, Iranian male). These examples indicated participants’ experiences of prejudice through the influence of and misrepresentation by the media in shaping a negative global valuation of their culture and subsequently influencing their ECI within the host country.

Personal Experiences of Discrimination

Participants raised the issue of discrimination as impacting their cultural identity and adjustment to life in Canada. Both Afghan and Iranian youth shared personal experiences of discrimination as immigrants in Canada, however, these stories were predominantly shared in their interviews and journals as opposed to focus group settings. Personal experiences of discrimination included (a) visible difference, (b) rationalizing jokes, and (c) school experiences.

Visible Difference

Afghan and Iranian youth reported a number of experiences related to discriminatory experiences based on their visible difference. One Iranian male youth talked about feeling upset when people asked the notorious question, ‘where are you from?’ and offered the example of a friend who “was born here” to experience common conversations with strangers such as:

So where are you from?, she goes, ‘I’m Canadian’, the other person goes ‘no, where are your parents from?, she’s like ‘no, they were born here too’, they go ‘oh, how about their parents?’, ... how far are you going to go back just because they look like an East Asian? (17 year old, Iranian male).

This participant later shared other experiences of discrimination including being stopped 28 times by airport officials when traveling to the USA to attend summer camp, which suggested discrimination based on visible difference. Another participant expressed his frustration with discrimination of Iranians, citing the example of people assuming him to have emigrated from a rural area: “it’s like, ‘oooh, how is it like to be in a city like Toronto?’ and I’d say, ‘it’s just as crowded as the city I was in before,” (17 year old, Iranian male). In some cases participants wrote poignant statements in their journals of discrimination based on visible difference. One participant reported his experiences of discrimination while working at a high-end clothing store and how he was often misperceived as being Italian or Greek and that “they just don’t expect someone from the Middle-East to be working at Tommy Hilfiger... says a lot about people’s attitudes towards Asians,” (19 years old, Iranian male). An Afghan female participant reported that due to her skin colour, regardless of her culture and ethnicity, she faced a lot of discrimination as people would make comments to her such as “Paki go home and Paki-dot,” (name-calling in reference to the circle placed on the forehead; 20 year old, Afghan female).

Several participants described their frustration with being called an “immigrant” in relation to their visible difference. One Afghan female participant highlighted the fact that with the exception of First Nations people, Canadians were all immigrants from somewhere. At the time of the first focus group meeting, this participant had only been in Canada for two years yet was already frustrated with the label of immigrant, as evident by her remark “everybody is immigrant here... if another immigrant asks you suddenly where are you from... So doesn’t matter, why, you are also immigrant here,” (19 year old, Afghan female). Another participant described the pressure felt when identified as an immigrant. His comment also indirectly revealed that this is especially the case for immigrants who are visibly different in their attire, “there is definitely pressure if you are a person who is an immigrant and also wearing a hijab... Like when I am walking with someone who is in full hijab, I kind of feel self-conscious,” (25 year old, Afghan male). These examples express direct and indirect experiences of discrimination towards youth related to their visible appearance and in relation to youth’s ECI.

Rationalizing Jokes

Experiences of prejudice through rationalizing jokes emerged predominantly in the Afghan focus group discussions. Participants provided examples of jokes stemming from negative attitudes about their culture. Participants did not report these experiences as prejudiced or discriminatory, possibly as a way to rationalize or minimize the experience. However, for the participants, the jokes clearly impacted on their cultural identity and self-esteem. For example one participant reported that “at school or at work, the people are like, you know joking, when they ask you where you’re from and immediately they are like, oh, Osama Bin Laden, Al Queda but it’s like friendly, it’s not meant to hurt you.” The participant continued to reflect on the day the blackout occurred in Toronto in 2003, “I was at work and one of my co-workers actually goes to me and [said] your cousin did this or something like that ... and then they were laughing. It was innocent, there’s no harm,” (20 year old, Afghan female).

Further, a participant reflected on occurrences related to the war in Afghanistan and reported while carrying her knapsack at work:

This guy comes to me and goes... I think you have some explosives in that bag, trying to blow up this place. He said it in a joking way but still... it gets to you. Why do you say that? I asked him [and he responded] well, you are from Afghanistan, aren’t you? ... the only thing that you’re good at is war and...killing people (18 year old, Afghan female).

Youth from both groups described experiences of prejudice and discrimination, predominantly related to broader global events of 9/11 which influenced their ECI.

School Experiences

Several Afghan and Iranian youth, indicated incidences of discrimination at school from both teachers and students. One participant reported that “I never say that I am Afghan. I just be quiet with other kids at school.” She explained that when she had disclosed her cultural identity, the response from others had been one of questioning, first of her being “not like those people,” and then questioning of Afghan people in general, asking “what is wrong with those people?” (19 year old, Afghan female). One Iranian male participant reported that his teacher asked him how he arrived in Canada, “do you come by airplane? You guys have airplanes? Wow. I can’t believe you have more than donkeys,” (18 year old, Iranian male). Afghan youth also reported negative discriminatory experiences with teachers who quickly associated their problems to their culture: “... when we have a problem we ask them, [and teachers respond] okay ‘forget about your own Afghanistan, forget about that, this is not Afghanistan.” She continued to give an example of bringing a doctor’s note to school, “the teacher said, ‘it must be the Afghan doctor who gave you this note to not write your test or exam or don’t do the work or something,” (19 year old, Afghan female). Another participant reported, in reference to a classmate’s comment to another Afghan girl, “I know your country. I know your people... I watch your country on CBC [Canadian T.V. news channel],” which resulted in a fight at school (19 year old, Afghan female). The examples highlight daily experiences of discrimination influencing the ECI of youth at school and provide evidence of the influence of the global context on participant’s experiences of prejudice and discrimination.

Youth Expressions of Cultural identity

Fear of Disclosure and Silenced Cultural Identity

The negative, and often difficult, experiences the youth had with discrimination and prejudice impacted on their expressions of cultural identity. For many of these youth, such experiences often resulted in their consciously silencing or fearing to disclose their identity. A number of Iranian participants reported in their journals and interviews that they did not want to disclose they were Iranian in certain circumstances. For example, one participant wrote in her journal that despite having pride in her Iranian heritage, she acknowledged that she often did not want to disclose her cultural identity for fear of negative repercussions, including discrimination (17 year old, Iranian female). Similarly, another participant admitted that at times, he did not want to disclose his Iranian identity for fear of repercussions and discrimination, such as a fight that ensued at school (18 year old, Iranian male). Furthermore, another participant commented that although he recognized himself as Iranian, he consciously introduced himself as “Persian” due to ignorance about and discrimination of Iranians (18 year old, Iranian male). In an interview, a participant indicated that she did not want to put her Iranian identity on her passport, suggesting that she would be discriminated against. She reported that:

Yeah it is sometimes better to say that I am not Iranian, for example, when I went to go get my passport, I tried not to put my place of birth because I was going to the U.S., but that is because of others, not because of me. I want to be Iranian but because others think different about me...I prefer not to put my place of birth on my passport (18 year old, Iranian female).

Through interviews and journals, Afghan participants too spoke of fear of disclosing their cultural identity. Both male and female Afghan youth spoke of keeping their Afghan identity private, fearing that disclosure would bring discrimination. An Afghan male youth described difficulty telling people where he was from, for example, “even though I wanted to say I was born in certain places or I speak or I come from certain background, I did not think that it was necessary for me to do that or to explain it, because I had a fear about being discriminated against all that,” (25 year old, Afghan male). In addition, a participant cited in her journal an experience of discrimination in which she chose to stay silent while overhearing others “thrash Afghans and Muslims” due to fear of repercussions (18 year old, Afghan female). This participant also articulated in a focus group that her fear of disclosure and silencing of identity takes a toll on one’s energy, “there comes a time when you say, you know, there’s this dead end, when you just don’t wanna do it anymore. Whenever somebody does say to me, terrorist or whatever, I just give up and I may not say anything and just walk on.”

These examples reveal the impetus for participants’ need to suppress the expression of their cultural identity in various situations to avoid discrimination. Experiences of discrimination and prejudice influenced youth’s PCI. The examples provide further evidence of the influence of the global context on participants’ experiences of prejudice and discrimination.

Resiliency and Strength of Cultural Identity

While participants reported discriminatory experiences, a number of participants expressed personal strength and resilience as a coping reaction to their experiences of discrimination. For the Afghan group, in particular, experiences of discrimination appeared to strengthen in-group Afghan identity. As illustrated by one female participant’s comment who had been in Canada with her family for 15 years, and who still experienced discrimination as an immigrant, “sometimes when you feel that sense of unwantedness it makes you appeal more to your own culture because you’re seeing something that you can relate to,” (22 year old, Afghan female). Her comment points toward the paradoxical effect of discrimination on strengthening her sense of belonging within the group and thereby contributing to a sense of identity and personal resiliency. “I think what gave me my most strength, discrimination... I think that if I wasn’t discriminated I wouldn’t be who I am today. It has given me the strength that I have today.” This female participant went onto describe overcoming challenges in school in Toronto:

I felt like an outcast. I felt like I wasn’t wanted in the environment... and then I made the decision to myself that once I go to grade seven I’m gonna make sure I have a lot of friends and I’m gonna feel wanted... it’s not like I couldn’t read it but because I was discriminated against when I was younger, it was like a mental thing for me... internal struggle and I’ve overcome most of them.

Many of the Afghan participants articulated a renewed sense of interest and pride in their heritage after 9/11. Most participants described some amount of longing and commitment to Afghanistan as their home. Similarly in the Iranian group, a participant highlighted the current news coverage of Iraq being confused with Iran, and how this confusion impacted on the need to defend one’s cultural identity.

Despite the fact that youth in both groups reported accounts of prejudice and discrimination, they also indicated impressive youth participation in Canadian society and praise for multiculturalism in Canada. For example, both a male and female Iranian youth discussed their involvement in a program at school that promoted and celebrated multiculturalism and that they actively tried to correct and dispel myths about their culture. One 18 year old Iranian male participant reported being the president of a student program linking new students to the school. In addition, a 19-year old Afghan female participant who recounted numerous experiences at school describing discriminatory treatment from her teachers and prejudicial jokes also spoke positively of Canada, and reported that overall she “feels Canadian” and “connection to Canada.” She acknowledged Canada for positive aspects such as the ability to practice her religion in mosques, citizenship rights and access to education. Another participant who described herself as “always being the outcast” due to her skin colour, also reflected that these “past experiences have shaped who I am a lot,” (22 year old, Afghan female). The discussions indicated that while the youth had experienced challenges they were also positive about their own strengths. Their post-migration experiences had propelled youth to take personal action and learn more about their culture. Hence, negative experiences of being discriminated against or stereotyped due to their heritage prompted several participants to take social action and educate themselves and others to dispel inaccurate stereotypes and images that emerged in the post 9/11 global climate.

Discussion

Local Cultural Identity and Global Politics

Findings of this study indicated that cultural identity was by no means a benign or abstract concept for the youth. Across all data sources prejudice and discrimination was a powerful and explicit theme influencing cultural identity. However, it is important to note that despite numerous descriptions of prejudice and discrimination, the youth did not name or identify these experiences as such, but rather reported them as common everyday occurrences. Examples of prejudice, or negative attitudes towards their culture, were described mostly in terms of media and jokes that were related to societal and global influences and events. Personal experiences of discrimination were discussed in terms of their visible difference and negative experiences at school. The experiences of prejudice and discrimination led to paradoxical expressions of fear in disclosing their cultural identity and silencing of their cultural identity and also expressions of resilience and strength in their cultural identity. Given the timing of this study, occurring after 9/11 and with the ensuing war in Afghanistan, the experiences stemmed from the global valuation of the Middle East.

The importance of considering global valuation in cultural identity research is supported by the findings. Experiences of prejudice and discrimination influenced by societal and global contexts emerged as a powerful and explicit theme within the Afghan and Iranian groups. Youth in the study expressed strong sociopolitical and historical awareness of Afghanistan and Iran. Afghan youth spoke more strongly about sociopolitical issues than the Iranian group, likely due to the on-going war in Afghanistan, the global post-9/11 context, and the participants being on average older compared to the Iranian participants. Youth spoke defensively and supportively about their cultural background, referred to the war in Afghanistan and ensuing experiences of prejudice and discrimination they faced in Canada. The findings indicated cultural identity may be directly affected by the global valuation of different cultures, or the societal-esteem of Afghan and Iranian identities within the Canadian context. Youth’s cultural identity and experiences in Canada were shaped by events occurring in their country/culture of origin and by how these events were portrayed or responded to in their country of settlement. Despite experiences of prejudice and discrimination, the youth expressed an overall supportive position toward Canada and its multiculturalism.

However, the experiences of exclusion in the daily lives of the youth cannot be ignored. The negative global valuation of their cultures, portrayed by the media, was seen as a major contributor to shaping prejudicial attitudes and behaviours, and subsequently leading to fear and silencing of their cultural identity. The findings indicate the need to critically acknowledge both the global valuation and de-valuation of non-dominant cultures and the effect on the cultural identity of youth living in multicultural and immigrant receiving contexts.

Schools as Sites of Daily Experiences

Accounts of discriminatory experiences attributed to youth’s visible difference at school also emerged in the findings. Youth reported discrimination due to their skin colour, cultural practices and ethnic and cultural identity. It has been suggested that adolescents who are the most highly visible in appearance report more discrimination from prejudicial comments to discriminatory behaviours in the school setting (Berry et al. 2006). However, it is important to note that youth participants in this study were living in a multiracial and multicultural city (Toronto) and appeared to be referring to marginalized identities in combination with racialized ethnicities.

Youth reported discriminatory experiences from both teachers and students. School is one of the first places youth may encounter discrimination (Anisef and Kilbride 2003). In their study of immigrant youth in Ontario, Anisef and Kilbride (2003) found that prejudice and discrimination by peers was one of the most significant barriers to settlement (such as expressions of hate, teasing, experiences of rejection, shunning, bullying, and name calling). They too found immigrant youth were critical of their teachers for not being supportive and imposing assumptions and expectations on youth due to their culture. Other research has indicated that schools in multicultural and immigrant receiving settings are among the important environmental influences on adolescents’ self-esteem (Khanlou 2004). Research recommendations have identified the need to foster inclusive educational curricula encompassing multicultural, anti-sexist and anti-racist values of justice and equity (Anisef and Kilbride 2003; Khanlou et al. 2002). In addition, critical perspectives within school settings, that acknowledge global events in racializing and marginalizing cultural identities within the host country, are required to minimize the repercussions for members of non-dominant cultures.

Coping: A Paradoxical Response

The study’s findings also indicated a sense of struggle as well as a sense of personal resilience and socio-political awareness among the youth. Despite reported experiences of discrimination and prejudice within focus groups, interviews and journals, many of the participants stated that they had positive self-esteem and overall had a positive view of living in Canada. In concert with the literature, youth were found to respond to prejudiced and discriminatory experiences in both negative and positive ways. Similar to literature relating negative experiences of discrimination on ethnic identity and negative psychosocial outcomes (Berry and Sam 1997; Branscombe et al. 1999; Dubois et al. 2002), the youth in this study had a fear of disclosing their cultural identity and often chose to remain silent about their identity. The concept of silenced self has been documented by other work (Khanlou et al. 2002; Khanlou and Crawford 2006). In a study of mental health promotion among newcomer female youth, examining post-migration experiences and self-esteem, the theme of silenced self emerged as a coping strategy for youth to avoid situations where they were unable to communicate in English but wanted to have others respond to them in a positive way (Khanlou et al. 2002). Examples from youth in the current study were not specifically related to language difficulties, but rather their understanding of negative perceptions of others related to their culture, and in order to avoid systemic discrimination and altercation, as in airports, school or employment settings. These findings highlight the need to address systemic discrimination.

Contrarily, some youth expressed resilience and strength in reaction to experiencing prejudice and discrimination. Youth reported numerous “jokes” from others in their daily experiences. It may be suggested that the youth were trying to cope with the negative personal experiences of prejudice and discrimination by rationalizing them as “jokes”. This finding is supported by other research examining “forbearing” and “confrontational” responses by refugees in Canada to discriminatory experiences (Noh et al. 1999). Noh et al. (1999) found that forbearing responses, such as passively accepting discriminatory experiences or not reacting to them, led to more adaptive coping and diminished the strength of the link between discrimination and depression. Hence, describing experiences as jokes may have been a strategy to cope with them. The findings may also suggest that the youth chose to downplay experiences as jokes in the focus group settings, while in the presence of peers being more hesitant to fully express their emotions. Another explanation may be that the youth were able to acknowledge group discrimination more than discrimination directed at them individually. This is supported by Verkuyten’s (2002) research in the Netherlands which investigated a phenomenon called the personal/group discrimination discrepancy; minority and majority group adolescents perceived higher levels of discrimination directed at their group as a whole than at themselves personally as members of that ethnic group. It may also be suggested that participants were coping with these experiences by identifying more with their own ethnic group, creating a sense of solidarity and belonging (Branscombe et al. 1999; Schmitt et al. 2002), which may in turn lead to more positive attitudes towards other cultural groups, as found by Romero and Roberts (1998). Therefore, the use of jokes may have been a protective factor that youth utilized for personal resilience. Findings of the study indicate the need for further research to understand the implications of prejudice and discriminatory experiences for immigrant youth and how they may affect their psychosocial well-being.

Youth also expressed resilience and strength of their cultural identity through their overall positive sense of belonging, and promotion of multiculturalism in Canada. These findings are similarly supported by Verkuyten and Martinovic’s (2006) study in the Netherlands which examined youth attitudes towards multiculturalism in ethnic majority (Dutch) and ethnic minority (Morrocans and Turks) adolescents. They found that minority youth were more in favour of multiculturalism, despite more reported perceived discrimination than majority youth. They also suggested that minority groups favour multiculturalism as it offers the possibility of maintaining their own culture and obtaining higher social status in society, where majority group members may view ethnic minority retention of their culture as a threat to their status. In addition, it has been indicated that multicultural societies offer a degree of protection for minority group identification as a strategy to protect the self when challenged with prejudice and discrimination (Branscombe, Schmitt and Harvey 1999). In the current study, it appears that multiculturalism was embraced for the opportunity to maintain one’s culture. However, the findings also indicate daily encounters of prejudice and discrimination which also call into question the success of multiculturalism. In turn, participants may be adapting and integrating over time, therefore becoming more resilient and better able to address experiences of discrimination. Research also supports that the more integrated into society youth become, the higher their psychosocial functioning (Phinney et al. 2006). The findings suggest that further research is required to examine the role of multiculturalism on youth identity and integration. Given the changing and challenging global context, it is necessary for multicultural societies to better promote integration and minimize marginalization of immigrant group identities.

Study Limitations

The study’s limitations with regards to sampling and analysis are considered here. In order to ensure inclusion of youth from specific cultural backgrounds, purposive, nonrandom sampling was utilized. Participants in the study were educated youth (Afghan youth were mostly university students and Iranian youth were mostly high school students). In turn, it is possible that immigrant youth who volunteer to participate in research studies involving focus groups and interviews may reflect youth who are more adjusted to Canadian society, confident and resilient, rather than youth that may be more marginalized. In addition, although youth experiences from two particular cultural backgrounds were described, it is acknowledged that their individual life trajectories varied within and among these cultural groups. In order to address the sampling limitation a number of steps were taken to ensure the rigor of the study. First, because the goal of qualitative research is not to generalize but rather to provide sufficient information in order to consider its transferability, as much information as possible, within manuscript space limitations, has been provided here on the study’s methods along with extensive incorporation of participants’ quotes to enhance a thick description. In addition, triangulation approaches (data collection methods, investigator) were employed in order to add to the trustworthiness of the findings. Furthermore, reflexivity is important to consider. Reflexivity entails an ongoing process through which the researchers are cognizant of how their own personal beliefs, values, and experiences influence the research process. As the authors of this manuscript, we were involved in different capacities in the study and came from different cultural backgrounds. As the principal investigator of the study, the first author (NK) was involved in all phases and her cultural background was similar to one of the groups (Iranian) considered. The second author (JK) was for the most part involved in the analysis while the third author (CM) was involved for the most part in data gathering and data analysis. Their cultural background was different from the youth participants. In combination, our cultural and educational backgrounds and our experiences as immigrants or descendants of immigrants have contributed to sensitivities in considering the youth experiences from different positions.

In relation to analysis, the findings of the study were influenced by Romero and Roberts (1998) definition of prejudice and discrimination and Rosenberg’s (1979) framework on self-concept. Although this organization was representative of much of the data, other accounts of prejudice and discrimination and psychosocial outcomes may not have been represented in this paper. However, the use of multiple data sources (focus groups, in-depth interviews, journals and field notes) enhanced the study’s rigor. Multiple data sources also provided a means to improve the degree of comfort in discussing experiences of prejudice and discrimination and the depth of disclosing them. Participants had opportunities to talk with each other through focus groups and also describe experiences in journals and interviews. Participants disclosed more personal experiences of prejudice and discrimination in their journals and interviews than in the focus group settings. Focus groups lent to discussions of prejudice about broader societal and global factors. These broader issues appeared to be more generalized or shared notions, which may have been easier to disclose and talk about with peers, and possibly created a sense of solidarity and heightened cultural identification.

Conclusion

This paper examined the cultural identity of Afghan and Iranian immigrant youth in Canada. Influenced by Rosenberg’s framework on self-concept, the youth’s extant cultural identity and presenting cultural identity were found to be influenced by experiences of prejudice and discrimination. Findings indicate the importance of considering how youth’s cultural identities can be shaped by societal and global contexts and provide support for the concept of global valuation. In addition, findings suggest that experiencing prejudice and discrimination at societal levels poses challenges for youth yet, paradoxically, can also promote their resilience and sense of in-group identity among a sub-group of youth who are more socially involved and participative. Further research is needed to explore how fear and resilience related to experiences of prejudice and discrimination affect psychosocial well-being.

The implications arising from this study include the need to consider broader systemic policies and initiatives that acknowledge the global context in shaping youth’s identities. The sociopolitical climate of the host country, as well the larger global political milieu, can affect how youth relate to their identity, and their sense of connection and belonging to or exclusion from the host country. Inclusive policies and practices are needed that acknowledge and address cultural identity of youth in multicultural societies and settings, and also consider changing and challenging global context that can influence the daily lives of those living within multicultural societies. Through such efforts, among others, multicultural and multiracial societies can promote better integration of youth with marginalized identities.

Notes

The term youth is used here interchangeably with the term adolescent and is related to middle adolescence (grades 9–10) and late adolescence (grades 11–12). The secondary school period, instead of chronological age is suggested to capture the psycho-social developmental tasks associated with this period of development.

Dilmaghani (1999) believes that the actual Iranian population is larger than is captured by Statistics Canada. Due to multiple ethnicities, including Kurds, Turks, Asurians and Armenians, some Iranians may not identify their ethnicity as Iranian.

Based on place of birth.

One participant was a 25 year old undergraduate student, however given his interesting experiences and perspectives he was included in the study.

References

Anisef, P., & Kilbride, K. (2000). The needs of newcomer youth and emerging best practices to meet those needs: Final report. Retrieved May 1, 2006 from http://www.ceris.meropolis.net/Virtual%20 Library/other/anisefl.htm.

Anisef, P., & Kilbride, K. (2003). Managing two worlds: Immigrant youth in Ontario. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Beiser, M. (1988). After the door has opened: Mental health issues affecting immigrants and refugees in Canada. Ottawa: Health and Welfare Canada.

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (2006). Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity and adaptation across national contexts. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Berry, J. W., & Sam, D. L. (1997). Acculturation and adaptation. In J. W. Berry, M. H. Segall, & C. Kagitcibasi (Eds.) Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Vol 3. Social behaviour and applications (2nd ed., pp. 291–326). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Branscombe, N. R., Schmitt, M. T., & Harvey, R. D. (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 135–149.

Burns, N., & Grove, S. K. (2001). The practice of nursing research: Conduct, critique and utilization (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada. (2002). Facts and Figures 2002: Immigration overview. Ottawa: Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Retrieved March 17, 2006, http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/pub/facts2002/immigration/immigration_5.html.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada. (2004). Facts and figures 2004: Immigration overview. Ottawa: Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Retrieved March 17, 2006, from http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/pub/facts2004/permanent/10.html.

Crocker, J., & Major, B. (1989). Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review, 96, 608–630.

Dilmaghani, S. (1999). Who are we? The Iranians in Toronto today: Profile, contributions, issues. Toronto: Family Service Association Toronto.

DuBois, D. L., Burk-Braxton, C., Swenson, L. P., Tevendale, H. D., Lockerd, E. M., & Moran, B. L. (2002). Race and Gender influences on adjustment in early adolescence: Investigation of an integrative model. Child Development, 73(5), 1573–1592.

Earp, J., & Ennett, S. (1991). Conceptual models for health education research and practice. Health Education Research Theory and Practice, 6(2), 163–171.

Farmer, T., Robinson, K., Elliott, S. J., & Eyles, J. (2006). Developing and implementing a triangulation protocol for qualitative health research. Qualitative Health Research, 16(3), 377–394.

Galabuzi, G. (2002). Social inclusion as a determinant of health. Ottawa: Health Canada. Retrieved October 9, 2005 from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph- sp/phdd/overview_implications/03_inclusion.html.

Jakinskaja-Lahti, I., & Liebkind, K. (2001). Perceived discrimination and psychological adjustment among Russian-speaking immigrant adolescents in Finland. International Journal of Psychology, 36(3), 174–185.

Jakinskaja-Lahti, I., Liebkind, K., Horenczyk, G., & Schmitz, P. (2003). The interactive nature of acculturation: perceived discrimination, acculturation attitudes and stress among young ethnic repatriates in Finland, Israel and Germany. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27, 79–97.

Jasinkaja-Lahti, I., Liebkind, K., Jaakola, M., & Reuter, A. (2006). Perceived discrimination, social support networks, and psychological well-being among three immigrant groups. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 37(3), 293–311.

Kelly, N., & Trebilcock, M. (1998). The making of the Canadian mosaic: A history of Canadian immigration policy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Khanlou, N. (1999). Adolescent cultural identity and self-esteem in a multicultural society. Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster University, Doctoral dissertation.

Khanlou, N. (2004). Influences on adolescent self-esteem in multicultural Canadian secondary schools. Public Health Nursing, 21(5), 404–411.

Khanlou, N. (2005). Cultural identity as part of youth’s self-concept in multicultural settings. International Journal of Mental Health, 3(2), 1–14.

Khanlou, N., Bieser, M., Cole, E., Freire, M., Hyman, I., & Kilbride, K. (2002). Mental Health Promotion Among Newcomer Female Youth: Post-Migration Experiences and Self-Esteem. Ottawa: Status of Women Canada.

Khanlou, N., & Peter, E. (2005). Participatory action research: Considerations for ethical review. Social Science & Medicine, 60(10), 2333–2340.

Khanlou, N., & Crawford, C. (2006). Post-migratory experiences of newcomer female youth: Self-esteem and identity development. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 8(1), 45–55.

Kunz, J. L., & Hanvey, L. (2000). Immigrant Youth in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Social Development.

Liebkind, K., & Jasinskaja-Lahti, I. (2000). Acculturation and psychological well-being on psychological stress: A comparison of seven immigrant groups. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 10(1), 1–16.

Murphy, E., Dingwall, R., Greatbatch, D., Parker, S., & Watson, P. (1998). Qualitative research methods in health technology assessment: A review of the literature. (Chapter 5) Criteria for assessing qualitative research. Health Technology Assessment, 2(16), 167–198.

Noh, S., Kaspar, V., Beiser, M., Hou, F., & Rummens, J. (1999). Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: A study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40, 193–207.

Norquay, R. (2004). Immigrant Identity and the Non-Profit: A case study of the Afghan’s Women’s Organization. Toronto: CERIS Working Paper No.29.

Phinney, J. (1990). Ethnic Identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 499–514.

Phinney, J., Berry, W. B., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (2006). Understanding immigrant youth: conclusions and implications. In Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity and adaptation across national contexts. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Phinney, J., & Devich-Navarro, M. (1997). Variations in bicultural identification among African-American and Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 7, 3–32.

Phinney, J., Horenczyk, G., Liebkind, K., & Vedder, P. (2001). Ethnic identity, immigration and well-being. Journal of Social Issues, 57(3), 493–510.

Romero, A. J., & Roberts, R. E. (1998). Perception of discrimination and ethnocultural variables in a diverse group of adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 21, 641–656.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books.

Sam, D. L. (2000). Psychological adaptation of adolescents with immigrant backgrounds. The Journal of Social Psychology, 140(1), 5–25.

Sandelowski, M. (1986). The problem of rigor in qualitative research. Advances in Nursing Science, 8(3), 27–37.

Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Kobrynowicz, D., & Owen, S. (2002). Perceiving discrimination against one’s gender group has different implications for well-being in women and men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 197–210.

Shrake, E., & Rhee, S. (2004). Ethnic Identity as a predictor of problem behaviors among Korean American adolescents (2004). Adolescence, 39(155), 601–622.

Statistics Canada. (2003). Canada’s ethnocultural portrait: The changing mosaic. Ottawa Statistics Canada. Retrieved March 3, 2006, from http://statscan.ca/.

Surko, M., Ciro, D., Blackwood, C., Nembhard, M., & Peake, K. (2005). Experience of racism as a correlate of developmental and health outcomes among urban adolescent mental health clients. Social Work in Mental Health, 3(3), 235–60.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel, & W. Austin (Eds.) Psychology of intergroup relations (2nd ed., pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Verkuyten, M. (2002). Perceptions of ethnic discrimination by minority and majority early adolescents in the Netherlands. International Journal of Psychology, 37(6), 321–332.

Verkuyten, M., & Martinovic, B. (2006). Understanding multicultural attitudes: The role of group status, identification, friendships, and justifying ideologies. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(1), 1–18.

Willms, D., & Johnson, N. (1990). Qualitative research methods in health: A notebook for the field. Hamilton, ON: Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McMaster University.

Yoo, H. C., & Lee, R. M. (2005). Ethnic identity and approach-type coping as moderators of the racial discrimination/well-being relation in Asian Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(4), 497–506.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada under its standard research grants. Details are as follows: Khanlou (Principal Investigator), Siemiatycki and Anisef (Co-Investigators), Immigrant youth and cultural identity in a global context (2003–2006). The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Paul Anisef and Dr. Myer Siemiatycki (Co-Investigators) and Amy Bender and Stephanie de Young (Research Assistants) through the various stages of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khanlou, N., Koh, J.G. & Mill, C. Cultural Identity and Experiences of Prejudice and Discrimination of Afghan and Iranian Immigrant Youth. Int J Ment Health Addiction 6, 494–513 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-008-9151-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-008-9151-7