Abstract

Although interest in substance abuse in psychiatric patients has received increasing attention, there is scant study of hazardous and harmful drinking patterns in Arab/Islamic societies where socio-cultural patterning imposes total abstinence on drinking. However recent globalization has eroded such prescription. An aim of this study is to examine the severity of harmful and hazardous drinking in Oman. From Omani nationals seeking psychiatric consultation, an assessment of alcohol dependence or hazardous or harmful drinking was elicited using the World Health Organization’s assessment measure, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Clinical interviews were also conducted to ascertain the severity of alcohol dependence. The results from this convenience sample of patients suggest the presence of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption among non-psychotic attendees seeking psychiatric consultation. The clinical interview revealed that 49 patients of the consenting patients (n = 56) have persistent and clinically significant alcohol intoxication. Fifty patients scored in the pathological range of indices of harmful and hazardous alcohol consumption. There was no relationship between the socio-demographic variables and indices of AUDIT. The result is discussed in terms of the speculated increase in harmful and hazardous drinking among Omanis and the inherent limitation of undertaking a study where the topic of interest is socio-culturally abhorred.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It has been suggested that approximately 10% of alcohol consumers will at some time experience serious health problems related to their drinking habit. More than 15 million people are disabled because of alcohol use. Alcohol abuse is the fourth leading cause of worldwide disability (Room, Babor & Rehm, 2005). There is a dearth of reports on the pattern of alcoholic beverage consumption in societies of the Arabian Gulf. These societies are predominately Muslim. Alcohol has been known in this region as testified by the finding that some Pharaohs of ancient Egypt did produce an alcoholic beverage that is similar to present day beer (Mandelbaum, 1965). The English word alcohol, derived from the Arabic, al-kuhl, refers to distilled substances such as essence (Edwards, 2003). The pleasurable effects of alcohol have been metaphorically celebrated in the vernacular of Arabic poems and stories of Abu Nawas. He captured life in taverns and epicureans and advised on convivial drinking (Colville, 2004). Such glorification of alcohol consumption occurred despite Islamic teaching that alcohol is an intoxicant, repugnant spiritually and should be avoided (AlBar, 1997). More recently, emerging anecdotal reports and impressionalistic observations suggest that there is a rise of alcohol related illnesses and deaths. More adverse alcohol related social problems are being noticed in Islamic societies (Maghazaji & Zaidan, 1982; Younis & Saad, 1995; Karam, Maalouf & Ghandour, 2004: Koronfel, 2002; Eapen, Jakka & Abou-Saleh, 2003).

The social problems precipitated by harmful and hazardous alcohol consumption have not yet been reported in Oman, a country in the Arabian Gulf. Due to its perceived isolation and mediaeval-like society, Oman has been labeled as a ‘beleaguered hermit kingdom’ (Peterson, 2004). However, in the past decades, rapid development triggered by the discovery of oil has rapidly modernized and acculturated Omani society. The population, the majority of which is under the age of 20, is estimated to be nearly 3 million. It is scattered around 300,000 km2 of mainly desert terrain accentuated by coastal enclaves attracting monsoon rains, high altitude plateaus with blooming green pastures and oasis in the midst of sand dunes. With such geographic features, Oman is labeled by some commentators (e.g., Palgrave, 1864) as a ‘garden Peninsula,’ which is conducive for the growing of ingredients for brewing alcoholic beverages. Except for a few ‘moonshine’ type breweries scattered around its impenetrable mountains (Wellsted, 1838), to our knowledge there is no study on alcohol beverage consumption in Oman. Before the advent of oil and the vast developments that resulted, alcoholic beverages are not sold in Oman. With increasing globalization and westernization and as the country is working to diversify its economy by developing and boosting tourism (Looney, 1990; Oman: Economy, 2001), there seems to be an implicit ‘relaxed’ attitude towards the availability of alcoholic beverages. Now alcohol is available in hotels and restaurants. Some private companies have clubs that sell alcohol to both their Omani and expatriate staff. From these clubs alcohol could be purchased for consumption at home. There are also dedicated shops that sell alcohol to non-Omanis upon the presentation of a special permit (P. J. Ochs & P. Ochs, 1999). Little is known about harmful and hazardous alcohol consumption in Oman in light of the limited availability.

As persons at risk of drinking problems cannot be easily identified, attempts have been made to develop quick screening instruments. Among the varied and widely used instruments, the World Health Organization’s Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) has been specifically designed to transcend cultural barriers. AUDIT was initially designed to elicit the quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption, drinking behavior and alcohol related problems or reactions among those who were attending primary health care centers. As AUDIT was designed to detect hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption prior to the onset of alcohol related disorders, the AUDIT was found to be suitable for use across a variety of health care settings and among patients of different cultural backgrounds (Volk, Steinbauer, Cantor, & Holzer, 1997; K. B. Carey, M. P. Carey, & Chandra, 2003; Gache et al., 2005; Leonardson et al., 2005; Adewuya, 2005). “Hazardous” was defined by Volk et al. (1997) as “established pattern of use, placing the user at greater risk of future damage to physical and mental health, but which has not yet resulted in significant medical or psychiatric consequences” while harmful use is defined as “a pattern of alcohol use which has already caused damage to health, either physical or mental, but does not meet criteria for dependence” (p. 198, Volk et al., 1997). The AUDIT was developed to identify persons ‘at-risk’ of developing alcohol use disorders. Observation in Oman suggests that some of the patients who seek psychiatric consultation appear to have tendency of alcohol dependence (Al-Sinawi & Al-Adawi, 2006). A study to explore incidence of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption among non-psychotic psychiatric clinic attendees in Oman using AUDIT is therefore essential.

While there is a large amount of data on the impact of alcohol prices on various outcomes related to alcohol consumption (Sloan, Reilly, & Schenzler, 1994; Farrell, Manning, & Finch, 2003), there is scant attention paid to the relationship between accessibility/availability and pattern of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption. Oman may represent a fertile ground to explore drinking patterns and characteristics of drinkers’ vis-à-vis accessibility/availability, the potential for religion to act as a deterrent and or whether sub-cultural differences have any effect on alcohol consumption. Therefore a study to examine the relationship between the composite score of AUDIT and the socio-demographic variables is indicated.

Oman has strong historical ties with the Indian subcontinent, East and Central Africa (Nicolini & Watson, 2004). A sizeable number of Omanis were born and or educated in these places. Since alcohol is freely available on the Indian subcontinent, East and Central Africa one could speculate that Omanis with contact with these places may have a different level of alcohol use. Previous studies have suggested that ethnicity can either be a protective or independent predictor of harmful and hazardous alcoholic consumption (Marsiglia, Kulis, Hecht, & Sills, 2004; Wallace et al., 2002; Rissel, McLellan, & Bauman, 2000). Some of these studies explored this relationship where alcohol is readily available. To our knowledge, there is no study that has explored the trajectory between ethnicity and propensity toward hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in a region where sociocultural teaching depicts alcohol as repugnant spiritually and many ethnic groups co-exist.

In the light of the above-mentioned background, this paper has the following aims. Firstly, to explore the incidence of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption among non-psychotic psychiatric clinic attendees in Oman using AUDIT. Secondly, to explore the relationship between pattern of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption as indexed by AUDIT and demographic variables. The final interrelated aim is to explore whether ethnicity plays a part in the expression of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption.

Materials and Methods

Setting

The sampling plan for this study was a convenience sampling procedure among patients who came for psychiatric consultation in the Department of Behavioral Medicine at the Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH). SQUH serves an ethnically diverse community. Being the only teaching hospital in Oman, it also caters for referrals from all the regions of the country. The annual patient-visit volume per year for SQUH is in excess of 100,000. Approximately 11,000 of these seek psychiatric consultation per year (Al-Sinawi & Al-Adawi, 2006). The present sample consists of consecutive patients attending outpatient psychiatric clinic for mood, anxiety and or personality disorders between 2001 and 2002. Inclusion criteria were that the patient should be Omani, the patient’s clinical picture should be independent of general medical conditions and that the patient admits to alcohol use.

A total of 75 patients admitted to alcohol use during the period and were invited to participate in the study. Fifty-six of the 75 patients agreed verbally to participate in the study and were interviewed using the structured interview and UDIT. All females who admitted to alcohol use except one declined to participate in the study. The subjects were explicitly informed that information sought would remain anonymous and their participation would not in anyway affect their treatment for psychiatric distress. If the patient deemed their problem was alcohol related options for seeking detoxification was also offered. As Islamic teaching teaches abstinence and since Omanis are Moslems with a culture where shame plays a strong social patterning (Dwairy, 1997), it was assumed that those Omanis who consume alcohol may try to conceal the behavior from other Omanis. Therefore it was reasoned that patients were more likely to open up about alcohol to non-Omanis. The strategy and rationale for screening population with sociocultural teaching that call for total abstention has been detailed elsewhere (e.g., Dotinga, van den Eijnden, Bosveld, & Garretsen, 2004). Therefore only non-Omani members of the research team conducted the interviews.

Socio-demographic information such as gender, residence, education and marital status were sought. Also ethnicity according to ones geographical origin was sought. For example subjects were asked if their parents or grand parents were born and or educated in the Indian sub-continent, Indian Ocean rim, East or Central Africa or if any ancestors have ever lived outside Oman.

Assessment Measures

Hazardous and Harmful Alcohol Consumption Instrument

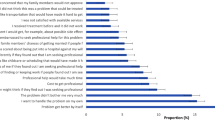

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) is a 10-item questionnaire designed to screen for hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption (Babor & Grant, 1989). Individual items of AUDIT are shown in Table 2. The AUDIT uses International Classification of Diseases (Lima et al., 2005: Pal, Jena, & Yadav, 2004; Volk et al., 1997) criteria to identify patients with symptoms of alcohol dependence (three items) and harmful alcohol consumption (four items). It also includes three consumption-based items, serving as indicators of hazardous alcohol consumption. A diagnosis of alcohol dependence is made if at least three of these criteria are present during the past 12 months. Responses to each question are scored from 0 to 4. A total score of eight or more is taken to indicate hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption (Conigrave, Saunders & Reznik, 1995).

Many studies have examined the reliability and concurrent validity of AUDIT (Kelly, Donovan, Chung, Cook, & Delbridge, 2004; Mendoza-Sassi & Beria, 2003; Selin, 2003; Shields, Guttmannova, & Caruso, 2004). In the majority of these studies AUDIT has been found to have good psychometric properties with impressive accuracy (Carey et al., 2003; Assanangkornchai, Pinkaew, & Apakupakul, 2003; Volk et al., 1997; O’Hare, Sherrer, LaButti, & Emrick, 2004; Hiro & Shima, 1996). AUDIT has been used to screen for the presence of hazardous and harmful drinking in many clinical populations (O’Hare et al., 2004; Philpot et al., 2003; Reid, Tinetti, O’Connor, Kosten, & Concato, 2003). To make the AUDIT dialectically adaptive to an Omani sample, experienced staff members produced an Arabic-language version of the scale by using the method of back-translation (Al-Adawi, Dorvlo, Burke, Moosa, & Al-Bahlani, 2002). For consistency and to make sure that the subjects understood the questions, the items were read to the subjects rather than allowing them to self-administer the AUDIT, even though it was designed as a self-report questionnaire (Babor & Grant, 1989). During preparation for the study interviewers were trained to reliably read out the items of the translated AUDIT and to rate the responses accordingly. As a result, there was substantial inter-rater agreement of the various items of the scales (r = 0.86, p < 0.001). The Cronbach’s α was equal to 72.6%, which shows a high internal consistency for the ten questions.

In addition to AUDIT, clinical interviews were conducted. These clinical interviews were based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV: American Psychiatric Association, 1994) guidelines and are used to diagnose the presence of persistent and clinically significant alcohol intoxication and the presence of functional incapacitating alcohol withdrawal. Two different people administered the clinical interview and the AUDIT questionnaire to each patient.

Statistical Analyses

The data was analyzed using SPSS. Cross tables were generated. Chi-square measures of association were calculated with their corresponding Fisher exact p values. To further understand the effect of the demographic variables, log linear modeling was employed.

Result

Fifty-six patients agreed to participate in the present study, all males except one female. Approximately 30% reached the unit via self-referral or direct contact with the hospital. Another source of referral was the national military hospital or Accident and Emergency unit of Sultan Qaboos University Teaching Hospital. Seventy-three percent (n = 41) of the patients have previously sought psychiatric consultation. The youngest in the present cohort was 18 years old while the oldest was 63 year old. The average age was approximately 36 ± 10 years. Approximately 71% of the subjects resided in an urban area. Nearly 29% of the subjects were single, 57% were married and the rest were divorced. Only Muslims were included in the sample. In terms of educational attainment, only one subject did not acquired modern education; 59% acquired either primary or secondary education while the rest have undertaken professional degrees or graduate studies. The sample consisted of patients from all walks of life. There were teachers, students, engineers, accountants, military personnel and business people. There were seven subjects who were unemployed at the time of the interview.

As alluded to earlier, the first aim of this study is to explore the presence of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption among non-psychotic attendees seeking psychiatric consultation. The clinical interview of the consenting patients (n = 56) based on DSM-IV and ICD-10 found in 49 patients the presence of persistent and clinically significant alcohol intoxication and the presence of functional incapacitating alcohol withdrawal. Fifty patients scored 8 or more on the composite AUDIT score. This indicates that 89% of the patients are prone to harmful and hazardous alcohol consumption. The sensitivity and specificity of AUDIT are thus 89.8 and 85.7% respectively for this group of patients. The average composite AUDIT score was 15.8 with a standard deviation of 7.6 units.

The AUDIT was made to identify three criteria of alcohol abuse—‘alcohol dependence,’ ‘harmful alcohol consumption’ and ‘hazardous alcohol consumption.’ A diagnosis of alcohol dependence is made if at least three of these criteria are present during the past 1 year. Only five patients have only one or two AUDIT criteria present. Hence 91% of the patients are alcohol dependent. The incidence of abuse, when measured by the different sub-scales, is high among this group of patients. Based on the first three criteria of AUDIT, ‘alcohol dependence,’ 40 out the 56 patients scored two or more suggesting the presence of alcohol dependence (Table 1). On the ‘harmful alcohol,’ 51 patients scored in the clinical range. On ‘hazardous drinking,’ 50 patients scored in the clinical range. The proportion of indices of ‘alcohol dependence’ is significantly lower than the proportion of indices of ‘hazardous drinking’ and ‘harmful alcohol’ consumption (p value < 0.001).

Table 2 illustrates the distribution of all the items of AUDIT. Approximately 66% of the subjects have an alcoholic beverage on more than four occasions a week. On a typical day when they were drinking they consumed more than six drinks and this happened almost on a daily basis for 50% of them. Also on a daily basis in the past year about 45% could not stop themselves once they started drinking. Only 14% were able to continue their normal functions after drinking while over 44% could not function properly after a night of drinking. About 54% usually did not remember what happened the night before and 37% needed a ‘pick me up’ the following morning. Fortunately over 71% reported that nobody was injured because of their drinking in the past year. Friends, relatives and doctors have been concerned about the drinking habit of about 68% of the patients. On the whole, this suggests that 56 non-psychotic psychiatric clinic attendees have a marked harmful drinking and hazardous drinking pattern.

The second integral aim of this study is to explore demographic correlates of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption as indexed by AUDIT. Table 3 shows the test of independence of the AUDIT questions over demographic variables such as residence, marital status, education. Availability is defined as the place where the patients work. Ethnicity, education and availability are all independent of the AUDIT composite scores. That is there is no relationship between ethnicity, education, availability and the AUDIT questions. Also there is no relationship between urban–rural, marital status and all the AUDIT questions except marital status depends on “How often during the last year have you failed to do what was normally expected from you because of drinking.” The results show that divorcees were more prone to heavy drinking. “How often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking” depended on place of residence. A large proportion of the urban residents never felt guilt after drinking. Since the sample size is relatively small, multilevel cross tables (many empty cells) and log-linear model analysis cannot be used to study the interrelationship between all the demographic variables at the same time. All possible three way models were tried and no significant association found among the demographic variables. A future study with much larger sample sizes is warranted to study the inter-relationship between the demographic parameters.

Another level of aggregation was to address the hypothesis that accessibility is related to alcoholic beverage use. The specific question was how does place of work influence alcohol consumption. Fifty-four percent (30 out of 56) of the subjects work in a place where alcohol was freely available for its employees, 14% did not have such privileges at their workplace. There was no information on availability from 14% of the subjects. Place of work as a measure of accessibility is not related to alcohol use (p value = 0.63). The log-linear model analysis did not show any significant differences.

The final level of aggregation was to address whether ethnicity as reflected by ones place of birth, may be central to cultural affinity. Fifty percent of the subjects (28 out of 56) were born and lived all their lives in Oman. Twenty-five out of these 28 tested positive on the indices of alcohol dependency. Sixteen and twelve of the patients that grew up or went to school on the Indian sub-continent or East/Central Africa respectively also tested positive. In this sample there was no difference in the level of alcohol consumption based on ethnicity (p value = 0.734). Ninety percent of the urban residents were positive while 87.5% of those in the rural area were positive. The high incidence of harmful and hazardous drinking is the same in both the urban and rural residents (p value = 1.0).

Discussion

Alcohol is becoming a major public health problem globally, including the Arab/Islamic world. There is therefore the need to find culturally sensitive ways to elicit the presence of alcohol related disorders. In the Arab part of the world, various assessment measures have been validated to Arab populations. (Bilal, Kristof, Shaltout, & El-Islam, 1987; Amir, 1994; Al-Ansari & Negrete, 1990). To our knowledge, none of them have used AUDIT. The present study suggests that AUDIT has adequate psychometric properties for eliciting the presence of hazardous and harmful drinking in patients seeking psychiatric intervention. The high sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value for a series of cut-off points collaborates the results of some previous studies (Carey et al., 2003; Assanangkornchai et al., 2003; Volk et al., 1997). Furthermore, there was no indication that AUDIT was marred by linguistic and conceptual misunderstandings as was the case with other instruments that were developed in one culture and then applied to another (Al-Adawi et al., 2002). The AUDIT has performed well in a culture where drinking alcohol is a habit that is viewed as repugnant.

As the efficacy of AUDIT indicates that it can be used to study the pattern of hazardous and harmful drinking in Oman in a broader representative sample, this paper has focused on three interrelated aims. The first aim of the paper is to explore the incidence of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption among non-psychotic psychiatric clinic attendees in Oman using AUDIT. As indexed by most scoring highly on the AUDIT, it appears the level of hazardous and harmful drinking is quite high among this group of patients. Studies from Northern America and Scandinavia suggest that non-psychotic patients with mood, anxiety and or personality disorders are prone to alcohol induced problems (Cantor-Graae, Nordstrom, & McNeil, 2001; Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2005; Landheim, Bakken, & Vaglum, 2006). There are suggestions that these patients consider the consumption of alcohol as ‘self-medication.’ Also a significant portion of the patients with alcohol related disorder meet diagnostic criteria for mood, anxiety and some personality disorders (Hasin, Goodwin, Stinson, & Grant, 2005; Thomas, Randall & Carrigan, 2003). Alcohol has also been suggested to ‘mask’ some psychiatric disorders (Alford, 2004; D. W. Brook, J. S. Brook, Zhang, Cohen, & Whiteman, 2002).

Within these constrains and the absence of a readily available national survey data, one of the central aims of this study was to explore socio-demographic correlates of hazardous and harmful drinking of patients seeking treatment so that educational and interventional strategy could be identified. One of the worthwhile socio-demographic factors that are relevant to Oman is the relationship between accessibility and pattern of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption. Previous studies have suggested that availability is a strong risk factor of whether or not individuals fall prey to substance dependence (Mandelbaum, 1965). In support of this view, until more recently, adverse effect of alcohol was rare in those communities where temperance movement prevails or alcohol is prohibited. In contrast, the incidence of gambling which is increasingly being recognized as ‘pathological’ and therefore ‘addictive’ (Petry, 2006; Hollander, Buchalter, & DeCaria, 2000) has become widespread. This has coincided with the growth of the gaming industry. On a historical note, some aborigine populations around the world have become devastated when alcohol became available (Mandelbaum, 1965). We examined whether one’s place of work influence the AUDIT score. The presently defined index of accessibility was not significantly related to degree of hazardous and harmful drinking.

The third aim of this paper is to explore whether ethnicity plays a part in the expression of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption. Oman has had long historical ties with areas on the Indian Ocean rim where alcohol is freely available. For the present purpose, in order to gauge the effect of ethnic ties, the subjects were asked whether they were born or have any ethnic ties with East and Central Africa, the Indian sub-continents or otherwise. On the whole, the patients’ place of birth has little or no influence on harmful alcohol consumption. Studies from other multicultural societies suggest that ethnicity is a significant predictor of adverse effect of alcoholic consumption. Some studies have suggested that there is significant variation in use of dependency substances including alcohol by ethnic groups. It is suggested that a sense of ethnic belonging do protect some from succumbing to hazardous and harmful drinking (Wallace et al., 2002). Among this group of patients, there is no indication that ethnicity plays a part, protective or otherwise, in so far as hazardous and harmful drinking is concerned.

Some obvious limitations should be acknowledged. This convenience sample is derived from only patients who have admitted to consuming alcohol. This obviously diminishes the generalization of the pattern of alcohol consumption in Oman. Secondly, in a society where drinking alcohol not only offends social norms but also constitutes a sinful act, to determine the magnitude of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption would require special consideration. Also it is possible that those who freely admit to alcohol consumption in this culture are so advanced in the habit that the demographic parameters could not discriminate among them. It is worthwhile to note that approximately 25% of those who admitted to consuming alcohol refused to participate in the study. In some studies conducted among Muslim minorities in Western Europe, where alcohol is easily available, researchers have to use circuitous means to elicit information from these groups (Dotinga et al., 2004). The present study can be questioned on the ground that it relied heavily on self and subjective report. The fact that there is a culture of silence among those who have alcohol problems may imply that subjective measures may not be the most fruitful approach. Future studies ought to use biochemical state markers of alcoholism. Another limitation is that mainly males consented to participate in this study with the exception of one female. The presence of a female in the present study may be an exception or the fact that alcohol consumption is no more limited to males only (Walter, Dvorak, Gutierrez, Zitterl, & Lesch, 2005). Although there is no justification for speculating on an increase in the number of women consuming alcohol, we note that some of the subjects who refused to participate were women. On one hand, studies have suggested that women are less likely to be identified and diagnosed with harmful and hazardous drinking while other reports suggest that alcoholism is the third leading cause of morbidity and mortality among women (Svikis & Reid-Quinones, 2003).

Recent global calls for harm reduction due to alcohol abuse have not focused on areas where the availability of alcohol is restricted. Islamic teaching prescribes total abstinence from alcohol. Therefore dependence on alcohol would be expected to be rare in such societies (cited in Mandelbaum, 1965, p.281). On contrary, this preliminary study, together with others from similar societies (Rissel et al., 2000; Bilal et al., 1987; Hafeiz, 1995; Weiss, Sawa, Abdeen, & Yanai, 1999), unequivocally suggests the existence of harmful drinking among Arab/Islamic populations. It needs to be noted that clinical populations cannot always be generalized to the general public. However, sometimes a clinical presentation may be the tip of a much larger problem that is likely lying dormant. In this case the culture of silence surrounding alcohol consumption may hide the true gravity of the problem. Community surveys will be an essential extension of the present undertaking.

References

Adewuya, A. O. (2005). Validation of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) as a screening tool for alcohol-related problems among Nigerian university students. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 40, 575–577.

Al-Adawi, S., Dorvlo, A. S., Burke, D. T., Moosa, S., & Al-Bahlani, S. (2002). A survey of anorexia nervosa using the Arabic version of the EAT-26 and “gold standard” interviews among Omani adolescents. Eating and Weight Disorders, 7, 304–311.

Al-Ansari, E. A., & Negrete, J. C. (1990). Screening for alcoholism among alcohol users in a traditional Arab Muslim society. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 81, 284–288.

AlBar, M. A. (1997). The problem of alcohol and its solution in Islam. Jeddah: Saudi Publishing & Distributing House.

Alford, D. (2004). Alcohol, drug dependence late in life. Age-associated changes can mask the problem, but the odds of recovery are good. Health News, 10, 6–7.

Al-Sinawi, H., & Al-Adawi, S. (2006). Psychiatry in the Sultanate of Oman. International Psychiatry, 3, 14–16.

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th edn.). American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC.

Amir, T. (1994). Personality study of alcohol, heroin, and polydrug abusers in an Arabian Gulf population. Psychological Report, 74, 515–520.

Assanangkornchai, S., Pinkaew, P., & Apakupakul, N. (2003). Prevalence of hazardous-harmful drinking in a southern Thai community. Drug and Alcohol Review, 22, 287–293.

Babor, T. F., & Grant, M. (1989). From clinical research to secondary prevention: International collaboration in the development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Alcohol Health and Research World, 13, 371–374.

Bilal, A. M., Kristof, J., Shaltout, A., & El-Islam, M. F. (1987). Treatment of alcoholism in Kuwait: A prospective follow-up study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 19, 131–144.

Brook, D. W., Brook, J. S., Zhang, C., Cohen, P., & Whiteman, M. (2002). Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 1039–1044.

Cantor-Graae, E., Nordstrom, L. G., & McNeil, T. F. (2001). Substance abuse in schizophrenia: A review of the literature and a study of correlates in Sweden. Schizophrenia Research, 48, 69–82.

Carey, K. B., Carey, M. P., & Chandra, P. S. (2003). Psychometric evaluation of the alcohol use disorders identification test and short drug abuse screening test with psychiatric patients in India. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64, 767–774.

Colville, J. (2004). Poems of wine and revelry: The Khamriyyat of Abu Nuwas. New York: Kegan Paul.

Conigrave, K. M., Saunders, J. B., & Reznik, R. B. (1995). Predictive capacity of the AUDIT questionnaire for alcohol-related harm. Addiction, 90, 1479–1485.

Dawson, D. A., Grant, B. F., Stinson, F. S., & Chou, P. S. (2005). Psychopathology associated with drinking and alcohol use disorders in the college and general adult populations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 14(77), 139–150.

Dotinga, A., van den Eijnden, R. J., Bosveld, W., & Garretsen, H. F. (2004). Methodological problems related to alcohol research among Turks and Moroccans living in the Netherlands: findings from semi-structured interviews. Ethnicity & Health, 9, 139–151.

Dwairy, M. (1997). Addressing the repressed needs of the Arabic client. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health, 3, 1–12.

Eapen, V., Jakka, M. E., & Abou-Saleh, M. T. (2003). Children with psychiatric disorders: The A1 Ain Community Psychiatric Survey. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 48, 402–407.

Edwards, G. (2003). Alcohol: The World’s Favorite Drug. St. Martin’s Griffin, St. Martin Edition.

Farrell, S., Manning, W. G., & Finch, M. D. (2003). Alcohol dependence and the price of alcoholic beverages. Journal of Health Economics, 22, 117–147.

Gache, P., Michaud, P., Landry, U., Accietto, C., Arfaoui, S., Wenger, O., et al. (2005). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) as a screening tool for excessive drinking in primary care: reliability and validity of a French version. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 29, 2001–2007.

Hafeiz, H. B. (1995). Socio-demographic correlates and pattern of drug abuse in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 38, 255–259.

Hasin, D. S., Goodwin, R. D., Stinson, F. S., & Grant, B. F. (2005). Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 1097–1106.

Hiro, H., & Shima, S. (1996). Availability of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) for a complete health examination in Japan. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi, 31, 437–450.

Hollander, E., Buchalter, A. J., & DeCaria, C. M. (2000). Pathological gambling. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23, 629–642.

Karam, E. G., Maalouf, W. E., & Ghandour, L. A. (2004). Alcohol use among university students in Lebanon: prevalence, trends and covariates. The IDRAC University Substance Use Monitoring Study (1991 and 1999). Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 76, 273–286.

Kelly, T. M., Donovan, J. E., Chung, T., Cook, R. L., & Delbridge, T. R. (2004). Alcohol use disorders among emergency department-treated older adolescents: A new brief screen (RUFT-Cut) using the AUDIT, CAGE, CRAFFT, and RAPS-QF. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 28, 746–753.

Koronfel, A. A. (2002). Suicide in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine, 9, 5–11.

Landheim, A. S., Bakken, K., & Vaglum, P. (2006). What characterizes substance abusers who commit suicide attempts? Factors related to Axis I disorders and patterns of substance use disorders. A study of treatment-seeking substance abusers in Norway. European Addiction Research, 12, 102–108.

Leonardson, G. R., Kemper, E., Ness, F. K., Koplin, B. A., Daniels, M. C., & Leonardson, G. A. (2005). Validity and reliability of the audit and CAGE-AID in Northern Plains American Indians. Psychological Report, 97, 161–166.

Lima, C. T., Freire, A. C., Silva, A. P., Teixeira, R. M., Farrell, M., & Prince, M. (2005). Concurrent and construct validity of the audit in an urban Brazilian sample. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 40, 584–589.

Looney, R. E. (1990). Reducing dependence through investment in human capital: An assessment of Oman’s development strategy. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 24, 65–75.

Maghazaji, H. I., & Zaidan, Z. A. (1982). Alcoholism in Iraq. British Journal of Psychiatry, 140, 325–326.

Mandelbaum, D. G. (1965). Alcohol and culture. Current Anthropology, 6, 281–288.

Marsiglia, F. F., Kulis, S., Hecht, M. L., & Sills, S. (2004). Ethnicity and ethnic identity as predictors of drug norms and drug use among preadolescents in the US Southwest. Substance Use & Misuse, 39, 1061–1094.

Mendoza-Sassi, R. A., & Beria, J. U. (2003). Prevalence of alcohol use disorders and associated factors: A population-based study using AUDIT in southern Brazil. Addiction, 98, 799–804.

Nicolini, B., & Watson, P. J. (2004). Makran, Oman, and Zanzibar: Three-terminal cultural corridor in the Western Indian Ocean, 1799–1856 (Islam in Africa, V. 3). London, UK: Brill.

Ochs, P. J., & Ochs, P. (1999). Maverick guide to Oman (2nd ed). London, UK: Pelican.

O’Hare, T., Sherrer, M. V., LaButti, A., & Emrick, K. (2004). Validating the alcohol use disorders identification test with persons who have a serious mental illness. Research on Social Work Practice, 14, 36–42.

Oman: Economy (2001). Politics and government. Business Intelligence Report: Oman, 1, 1–38.

Pal, H. R., Jena, R., & Yadav, D. (2004). Validation of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in urban community outreach and de-addiction center samples in north India. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 65, 794–800.

Palgrave, W. G. (1864). Observations made in Central, Eastern, and Southern Arabia during a journey through that Country in 1862 and 1863. Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, 34, 111–154.

Peterson, J. E. (2004). Oman: Three and a half decades of change and development. Middle East Policy, 11, 125–137.

Petry, N. M. (2006). Should the scope of addictive behaviors be broadened to include pathological gambling? Addiction, 101(Suppl 1), 152–160.

Philpot, M., Pearson, N., Petratou, V., Dayanandan, R., Silverman, M., & Marshall, J. (2003). Screening for problem drinking in older people referred to a mental health service: A comparison of CAGE and AUDIT. Aging & Mental Health, 7, 171–175.

Reid, M. C., Tinetti, M. E., O’Connor, P. G., Kosten, T. R., & Concato, J. (2003). Measuring alcohol consumption among older adults: A comparison of available methods. American Journal on Addictions, 12, 211–219.

Rissel, C., McLellan, L., & Bauman, A. (2000). Social factors associated with ethnic differences in alcohol and marijuana use by Vietnamese-, Arabic- and English-speaking youths in Sydney, Australia. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 36, 145–152.

Room, R., Babor, T., & Rehm, J. (2005). Alcohol and public health. Lancet, 365, 519–530.

Selin, K. H. (2003). Test–retest reliability of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test in a general population sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 27, 1428–1435.

Shields, A. L., Guttmannova, K., & Caruso, J. C. (2004). An examination of the factor structure of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test in two high-risk samples. Substance Use & Misuse, 39, 1161–1182.

Sloan, F. A., Reilly, B. A., & Schenzler, C. (1994). Effects of prices, civil and criminal sanctions, and law enforcement on alcohol-related mortality. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 55, 454–465.

Svikis, D. S., & Reid-Quinones, K. (2003). Screening and prevention of alcohol and drug use disorders in women. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 30, 447–468.

Thomas, S. E., Randall, C. L., & Carrigan, M. H. (2003). Drinking to cope in socially anxious individuals: A controlled study. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 27, 1937–1943.

Volk, R. J., Steinbauer, J. R., Cantor, S. B., & Holzer, C. E. 3rd. (1997). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) as a screen for at-risk drinking in primary care patients of different racial/ethnic backgrounds. Addiction, 92, 197–206.

Wallace, J. M. Jr, Bachman, J. G., O’Malley, P. M., Johnston, L. D., Schulenberg, J. E., & Cooper, S. M. (2002). Tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use: racial and ethnic differences among U.S. high school seniors, 1976–2000. Public Health Report, 117(Suppl 1), S67–S75.

Walter, H., Dvorak, A., Gutierrez, K., Zitterl, W., & Lesch, O. M. (2005). Gender differences: Does alcohol affect females more than males? Neuropsychopharmacology, 7, 78–82.

Weiss, S., Sawa, G. H., Abdeen, Z., & Yanai, J. (1999). Substance abuse studies and prevention efforts among Arabs in the 1990s in Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian authority—A literature review. Addiction, 94, 177–198.

Wellsted, J. R. (1838). Travels in Arabia. London, UK: J. Murray.

Younis, Y. O., & Saad, A. G. (1995). A profile of alcohol and drug misusers in an Arab community. Addiction, 90, 1683–1684.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zaidan, Z.A.J., Dorvlo, A.S.S., Viernes, N. et al. Hazardous and Harmful Alcohol Consumption Among Non-Psychotic Psychiatric Clinic Attendees in Oman. Int J Ment Health Addiction 5, 3–15 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-006-9046-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-006-9046-4