Abstract

In this article we share the Academic Communities of Engagement (ACE) framework, which describes a student’s ability to engage affectively, behaviorally, and cognitively in an online or blended course independently and with support. Based on Vygotsky’s (Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1978) zone of proximal development, the framework examines how a student’s ability to engage in online or blended courses increases with support from two types of communities. The course community is organized and facilitated by those associated with the course or program. The personal community is comprised of actors not officially associated with the course who have typically formed relationships with the student before the course or program began and may extend well beyond its boundaries. Actors within each community have varying skills and abilities to support student engagement, and a student is most likely to reach the necessary engagement for academic success with active support from both. The framework identifies the community actors most likely to provide specific support elements, aligning them to the different types of student engagement. The article outlines implications for practice and research, concluding with illustrative examples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Online learning has increased dramatically at all levels of education for varied reasons: among them to improve availability, to better align with individual needs, and to overcome access barriers (Gemin et al. 2016; Seaman et al. 2018; Watson et al. 2012). Despite these potential benefits, online courses have higher attrition rates than in-person courses (Freidhoff 2018; Su and Waugh 2018), particularly for underserved and minority students who enroll in them to access educational opportunities unavailable to them otherwise (Dziuban et al. 2018). Rovai (2003) identified contributing factors external to a course that may impact online student attrition, including employment demands, life crises, family responsibilities, and inadequate support from those not directly involved with the course such as family and friends. Other studies have similarly indicated that student success in online learning depends partially on their personal support communities.

Analyzing over 1000 survey responses from students at an online independent secondary school, Oviatt et al. (2018) found students reported more support from those in their local personal community than from their online course instructor or online peers, although the online program did not facilitate these local support efforts. Families also strongly impact student learning in higher education, though their role in supporting online students is more commonly accepted and sought after in kindergarten through grade 12 (K-12). Roksa and Kinsley (2018) examined over 700 first-year low-income students and found that their families’ emotional support positively impacted academic outcomes more than even financial support.

Despite strong evidence for the powerful influence of students’ personal community on their learning, researchers have focused mostly on Moore’s (1989) three within-course interactions: student-content, student–teacher, and student–student. For instance, the highly influential, frequently cited Community of Inquiry (CoI; Garrison et al. 2000) came at a time when the internet enabled high levels of student–student interaction and collaboration. The CoI framework significantly impacted the field by drawing researchers’ attention to the importance of fostering a community where learners can project their full personality into mediated communication resulting in community-constructed knowledge.

However, as Archer (2010), one of the original authors of CoI, noted, CoI use “has been largely restricted to analysis of online discussions” (p. 69). Archer called researchers to “broaden the scope of the CoI framework” by taking a “new look at the overall rationale for the framework” (p. 69). Not only does the framework need to be broadened to include more types of learning activities, it has ignored the out-of-class interactions and support that can strongly impact student learning and performance. We need better theoretical frameworks that explain the role and interaction of important supplemental relationships and personal communities (e.g., families and friends) that support students’ engagement in online and blended learning.

In this article we argue for a new framework, Academic Communities of Engagement (ACE), for online and blended learning, which provides a more complete examination of both the course community and students’ personal support communities. This framework builds and expands on our previously proposed framework, the Adolescent Community of Engagement (Borup et al. 2014b), that described effects of teacher, peer, and parent interactions on adolescent engagement in online learning. Over the last 6 years we and our colleagues have refined and expanded the previous framework using a series of case studies in K-12 online and blended learning environments specifically designed to explore teacher engagement (Borup et al. 2014a; Borup and Stevens 2016, 2017; Borup and Stimson 2019; Borup et al. 2019a); parent and family engagement (Borup et al. 2015; Borup 2016a, 2019b; Oviatt et al. 2016, 2018); and peer engagement (Borup 2016b). Additionally, we saw evidence of how an expanded framework could be valuable for maturing learners in higher education (see three articles in dissertation by Spring 2018).

The purpose of this paper is to synthesize what we have learned from those case studies as well as emerging literature to formalize the expanded Academic Communities of Engagement framework. Several significant updates are identified and elaborated.

- 1.

Inclusion of higher education settings The framework applies specifically to all contexts where formal learning occurs. Previous use of the term adolescent emphasized age rather than the learning maturity and development of the students. For example, some adolescents are able to regulate their learning better than some adults. The updated framework changes the focus from age to learner ability.

- 2.

Expansion to include blended and online learning contexts The previous framework, which focused only on online learning contexts, has been extended to apply directly to blended learning as well.

- 3.

Inclusive view of personal support communities The previous framework focused on support from parents. The new framework has extended its view of the personal support network of family and friends.

The new ACE framework can guide practitioners in understanding how to best utilize all support structures to engage student learners, while also providing direction for researchers to examine new and previously under-explored aspects of students’ online experiences. In this paper we first discuss the framework, including the three main types of student engagement, the various support communities and their actors, and the elements of support that can help students succeed. We then offer a discussion of implications for practice and future research, followed by illustrative examples.

Academic Communities of Engagement

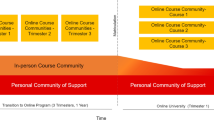

ACE is a theoretical framework focused primarily on how learning support communities can help maximize student academic engagement. Figure 1 represents its core elements which will be explained in greater detail later in the manuscript. The outer edge of the model represents the level of engagement necessary for academic success, distributed across three distinct dimensions of engagement: affective, behavioral, and cognitive (the dotted triangle). At the center of the model, students are represented as having an ability to engage independently (the black triangle). Two support communities can help students fill gaps between their independent ability and the engagement necessary for academic success:

The inner black triangle represents a student’s engagement independent of support from others. The engagement resulting from course community support is represented in yellow, and the engagement resulting from personal community support is represented in red. The order of the support the student receives is interchangeable in the figure and does not reflect a necessary sequence. The goal of the support communities is to help the student increase engagement to the level of engagement necessary for academic success, as represented by the dotted line

The course community, made up of peers, teachers, and administrators, provided with a course or program for formal support roles (the orange triangle).

The personal community, made up of family, friends, and others within students’ social networks, who can provide informal support (the red triangle).

A central tenet of the framework is that specific sources of the academic support, though important, are secondary to ensuring an appropriate level of support for all three dimensions of student engagement.

Model of student academic engagement

The term student engagement is frequently used in research, often positively correlated with valued educational outcomes including achievement (Hughes et al. 2008; Kuh et al. 2007; Skinner et al. 1990; Trowler 2010) and satisfaction (Filak and Sheldon 2008; Mountford-Zimdars et al. 2015; Wefald and Downey 2009; Zimmerman and Kitsantas 1997). However, the ways student engagement is defined and operationalized vary widely (Halverson and Graham 2019; Macfarlane and Tomlinson 2017; Reschly and Christenson 2012). Also, student engagement can be measured at a variety of levels, including engagement at the institutional level, the course level, and the activity level (Skinner and Pitzer 2012). The ACE framework considers engagement that is directly related to student involvement with academics (including engagement with course tasks and activities) rather than the institutional/school level. We refer to this as academic engagement to distinguish it from broader forms of student engagement discussed in the literature that focus on participation in extracurricular activities and institutional belonging beyond the course level.

We define academic engagement as the energy exerted towards productive involvement with course learning activities (Ben-Eliyahu et al. 2018; Halverson and Graham 2019) and identify three key dimensions where that energy can be measured. Because it is common for researchers to conflate the facilitators of engagement with engagement itself, we use Fig. 2 to help distinguish between facilitators, indicators, and outcomes of student academic engagement (Skinner et al. 2008; Ben-Eliyahu et al. 2018; Halverson and Graham 2019). In the following sections we elaborate these concepts and provide examples of how engagement facilitators, indicators, and outcomes are represented in the ACE framework.

Adapted from Halverson and Graham 2019, p. 147

General model of student engagement distinguishing facilitators, indicators, and outcomes

Engagement outcomes in the ACE framework

Student engagement is not typically an end in itself. We want students to be engaged because it leads to outcomes that we value such as achievement, satisfaction, or increased motivation. The outcome that the ACE framework focuses on is what we call academic success. We conceptualize academic success broadly, to encompass achieving the desired outcomes of a course. Course outcomes are often articulated in terms of knowledge, skills, and dispositions (what students should know, be able to do, and what they are becoming). This perspective goes beyond only equating success with the narrow definition of achieving a particular grade in a course, as grades are not always accurate or complete measures of students’ achievement of desired learning outcomes. For example, it is possible for a student to achieve course outcomes and still fail a course because she has submitted work late, or it is also possible for a student to go through the motions to pass a course without achieving more than the most surface-level course outcomes.

Engagement indicators in the ACE framework

Skinner et al. (2008) stated, “Indicators refer to the features that belong inside the construct of engagement proper, whereas facilitators are the causal factors (outside of the construct) that are hypothesized to influence engagement” (p. 766). Early synthesis research by Fredricks et al. (2004) as well as the seminal work found in the Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (Christenson et al. 2012) identified three core dimensions to engagement: affective, behavioral, and cognitive. However, there has been a persistent “conceptual fuzziness” in the body of engagement research (Halverson and Graham 2019, p. 151), particularly related to distinctions between indicators of behavioral and cognitive engagement (Henrie et al. 2015). The challenge arises because observable behaviors are typically the window into cognitive processes, therefore it is easy to conflate observations of cognitive and behavioral engagement. Halverson and Graham (2019) dealt with this issue by eliminating behavioral engagement as a key indicator while the research of Ben-Eliyahu et al. (2018) led to the creation of a combined indicator they call “behavioral-cognitive engagement.”

The ACE framework maintains the three classical dimensions of student engagement: affective, behavioral, and cognitive. However, we try to draw clearer lines between the observable indicators that make behavioral and cognitive engagement distinct (see Table 1).

Behavioral engagement is identified by the surface-level, physical behaviors required to complete course learning activities or tasks while indicators of cognitive engagement would be evidence of a deeper mental energy being exerted. For example, attendance or participation in a class might be evidence of behavioral engagement, while indicators of focused attention or absorption would be evidence of cognitive engagement. Similarly, submitting a course assignment or spending time in a learning management system (LMS) would indicate behavioral engagement while evidence of a student’s mental energy focused on asking questions, taking notes, checking understanding etc. would be evidence of cognitive engagement.

While there may often be a strong correlation between the three dimensions of engagement, especially for the most capable of learners, we believe that the three can also exist independently of each other and that low engagement in one dimension can lead to challenges in achieving academic success. Ben-Eliyahu et al. (2018, p. 88) provided three possibilities,

- 1.

“one could be behaviorally active but not cognitively or emotionally engaged in the task at hand”

- 2.

“one could be emotionally involved while not thinking about the learning task”

- 3.

“one could be thinking about materials and experiencing emotions, without implementing learning behaviors”

Learning standards tend to focus on “what students know and can do” (Kuh et al. 2014, p. 5). We also recognize that while not commonly measured in learning standards or grades, affective engagement supports students’ ability to behaviorally and cognitively engage in a course. A meta-analysis examining the influence of teacher-student relationships concluded that this type of affective engagement could be a “starting point for promoting school success” (Roorda et al. 2011, p. 520). For instance, Oldfield et al. (2019) found that university students failed to attend class when they felt isolated, did not like the personality of the instructor, or did not enjoy the course content. Meta-analyses have also found an important relationship between student emotions and academic outcomes (Roorda et al. 2011; Tze et al. 2016).

Affective engagement is especially important to academic success if students are expected to apply their knowledge and skills independently following the course. For example, a preservice teacher who has mastered the learning outcomes in a technology integration course may be highly dissatisfied if she believes that technology harms learning and does not intend to use it. A history teacher who realizes that many students come to class with negative attitudes toward the subject may have a goal of increasing students’ enjoyment in the course although it is not an official target outcome. Thus, while often unstated in learning standards, affective learning outcomes are important in reaching the larger goals of education (Shephard 2008).

Engagement facilitators in the ACE framework

Engagement facilitators are the factors that influence engagement. Student characteristics influence a student’s ability to engage. Long term interest in a subject or intrinsic motivation might be an antecedent to a student’s level of academic engagement. Similarly, the ability a student has developed to regulate her own learning could influence engagement levels. On the other hand, the course environment is what educators have the most control over. Teachers adjust their pedagogical strategies to try and directly or indirectly influence the engagement of their students. For example, a teacher might use a problem-based learning approach to try and influence students’ cognitive engagement. Or a teacher might use personal storytelling as a way to influence student interest in a topic, which in turn would affect the willingness to engage in the course activities. Teachers can also indirectly influence a student’s personal environment through direct invitations to the student and others in the personal environment. For instance, K-12 online and blended teachers and programs can extend invitations to parents to engage in their students’ learning in specific ways (Hoover-Dempsey et al. 2005). These types of invitations are especially important when those in the personal environment are unfamiliar with online and blended learning. Others have also advocated for increased supports for individuals within a student’s personal environment to help them better learn and fulfill their responsibilities (Oviatt et al. 2018; Hasler Waters and Leong 2014). The engagement facilitators that the ACE framework focuses on are the personal and course support communities available to the students. The individuals in these two networks fulfill roles that support increased engagement in all three dimensions.

ZPD for engagement

Bandura (1986) explained that ability to master course material is hindered considerably when a student relies only on individual efforts. Similarly, Vygotsky (1978) maintained that students’ independent performance provides a limited view of their capabilities, that what they “can do with the assistance of others might be in some sense even more indicative of their mental development than what they can do alone” (p. 85). What the individual can do only with the assistance of a more knowledgeable other is what Vygotsky (1978) termed the zone of proximal development (ZPD).

Vygotsky’s theory focused largely on a student’s ability to learn course material or perform content-related tasks; however, it can be applied to the capacity “to learn how to learn” (Lowes and Lin 2015, p. 18). Vygotsky’s insight that “any learning… has a previous history” (p. 84) can be extended to anticipate that those without experience learning in online and blended courses will likely require more extensive support.

Because online and blended learning provide students with a more flexible learning environment than in-person courses, students are required to exercise more autonomy. Roblyer et al. (2007) acknowledged, “Student ability to handle distance education courses appears to depend more on motivation, self-direction, or the ability to take responsibility for individual learning” (p. 11). We also echo Moore’s (1980) warning that “a learner cannot learn effectively if the educational transaction demands more autonomy than he is able to exercise” (p. 29). Students who lack self-regulation abilities or online and blended learning experience will need support to fully engage in learning activities.

A major tenet of the ACE framework is that, similar to Vygotsky’s concept of ZPD, students are limited in their ability to independently engage in their online and blended learning, but they can more fully engage in the activities when scaffolded by others (see Fig. 3). Similar to Vygotsky (1978), we emphasize that all students have a “dynamic developmental state” (p. 87) that requires support to be dynamic and to adjust to students’ abilities to independently engage in course activities.

While possibly correlated, age alone does not determine a student’s development, and a teenager may have more self-regulation than an older graduate student. Furthermore, the level of required support can vary substantially based on characteristics of both the student and the course. Some younger or less prepared students may not be able to engage at the levels required for academic success in challenging courses regardless of the amount of support they receive. Inversely, highly developed and experienced students may be able to achieve academic success with limited or no support.

As explained in the previous section, student’s ability to engage—and the type of support that the student would require—varies depending on the type of engagement. For instance, a student with high levels of interest in a topic (affective) but low self-regulation skills (behavioral) or metacognitive skills (cognitive) (as reflected in the shape of the black triangle in Fig. 4) would need high levels of support for cognitive and behavioral engagement but little support for affective engagement to achieve academic success. Students’ abilities to engage independently can also be subject-dependent or even activity-specific. For instance, a student’s ability to independently engage in a history class may look similar to Fig. 4, but the same student might have very low independent motivation for learning math and so would need greater support to engage affectively in a way that leads to academic success.

Support communities and actors

We argue that two primary communities can support each student’s affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement: a personal community and the course community.

Personal and course communities

A student’s personal community, extending well beyond the context of the course, is typically formed before the course or program begins—starting in some instances at birth. Personal community members know the student on a personal level, often including academic history, tendencies, interests, strengths, and limitations. The personal community exists within the local environments, but increasingly includes some who interact with the student at a distance and some who interact only online. Members of a student’s personal community may also tap into their own networks to arrange help they cannot provide themselves. For instance, parents who lack specific content expertise could hire a tutor or ask someone within their social network to voluntarily support the student. Students may also curate their own online support using social media. While the personal community can always impact student learning, its actors become especially important when students are enrolled in an online course with insufficient course community support (Oviatt et al. 2018).

The course community is organized and facilitated by those associated with the course or program who have knowledge of course content, expectations, and procedures. The course community is generally made up of peers with similar knowledge as the student as well as professionals who are experienced at supporting students in learning both course content and ways to learn in online and blended environments. While course community actors can form close, caring relationships with students, these are typically formed during the course and do not extend in meaningful ways beyond students’ course or program participation. However, enduring relationships formed in a course community can eventually become part of a student’s personal support community following the course. Table 2 summarizes some of the core characteristics that distinguish course and personal support communities.

Community actors

A student’s personal and course communities include different actors, who we group either instructors, peers, or family, categorized based on their skills, background, and relationship to the student. Actors can support the student through interactions that occur in person, online, or both.

Peers have similar understanding of the course content and procedures. They may also have similar backgrounds and experiences, which can include friendships formed in and out of the course or program. Family actors include individuals within the family social network who may or may not be directly related to the student: for example, a friend of a parent who agrees to provide some math tutoring. Students’ age and life circumstances can change the family actors as well as their influence on the students’ engagement. For instance, parents’ role is critical in supporting children’s and adolescents’ engagement, while for adult students their spouses/partners or their own children may have a more significant influence on their engagement.

Instructors have content expertise along with particular understanding of the course procedures and requirements—roles increasingly undertaken by multiple individuals (Harms et al. 2006). Online students may receive support from both an instructor, who delivers content and provides feedback, and facilitators, who build relationships with students and help them understand and meet online learning expectations. Depending on the learning model, facilitators can work with students at a distance or in person. Supplemental K-12 online programs are increasingly requiring students’ local schools to provide them with an on-site facilitator (Borup 2018; Hendrix and Degner 2016; Taylor et al. 2016). Other full-time programs for which students do not attend a local school may provide their students with an online facilitator or with academic coaches in addition to their online teacher (Drysdale et al. 2014). Similar models in higher education provide online students with a learning coach or have them meet regularly in local facilitated centers (Farrell 2007; Lehan et al. 2018; Ludwig-Hardman and Dunlap 2003; Spring 2018) where they may also interact with peers who are not enrolled in their specific course section. Thus, in blended and online courses the same peer or instructor can support the student in-person and online, but some instructor and peer actors may interact with the student only in one context or the other.

Support elements

In developing the original ACE framework, we consulted existing literature to identify support elements aligned to specific types of support actors (see Borup et al. 2014b), then used case studies to refine and expand the originally hypothesized support elements. But in the case studies we found considerable overlap in the supports that different actors were providing to students; in several cases, who was actually providing the support was less important than that the individual providing the support had a background and skills necessary for students’ needs. For example, many students required help troubleshooting technological issues. However, whether that support came from a parent, teacher, or peer did not seem to matter so long as the person providing the support had the required knowledge and skills. Similarly, our research examining a cyber charter secondary school found students likely to turn to their parents for content support when their teacher was not readily available, especially parents with a level of content expertise (Borup et al. 2015).

Thus, we aligned the support elements not to a certain actor, but to the type of engagement they would be most likely to influence (Fig. 5), although the list of possible support elements is not comprehensive and not all would be observed or needed across all students and environments. Students’ ability to engage in the activities and receive the desired support depends on their development and experience (Halverson and Graham 2019). While not all students require all support elements at equal levels, this section identifies specific support elements that are likely to increase student engagement.

Support elements for cognitive engagement

Two support elements are aligned with cognitive engagement: instructing and collaborating. Instructing occurs when knowledge is shared by a knowledgeable teacher enabling students to increase their understanding. Anderson et al. (2001) identified indicators of instruction, which included presenting content, asking questions, summarizing information, confirming understanding, providing feedback, diagnosing misconceptions, and providing resources. While Anderson et al. (2001) and the original ACE framework (2013) also included technological support, we consider this type of support most likely to impact behavioral engagement; we discuss it in the following section termed as troubleshooting and orienting. Instruction can be provided by course instructors or by peers and family who are more knowledgeable than the student in the content area. Peers and family who lack content knowledge can provide instructional support in more general ways, such as proofreading writing assignments.

In collaborating, individuals work together to co-construct knowledge that neither had previously or to develop a product they could not have created individually. Collaboration has been recognized as an important component of quality online courses (iNACOL 2011), although in practice, online courses have tended to emphasize providing students flexibility over facilitating meaningful collaboration (Garrison 2009; Gill et al. 2015). Thus, collaboration may be more commonly observed in blended environments. However, collaboration is becoming more common in online courses as online communication and collaboration tools are making it easier to collaborate at a distance.

Support elements for behavioral engagement

Three support elements are aligned with behavioral engagement: (a) troubleshooting and orienting, (b) organizing and managing, and (c) monitoring progress. These elements do not apply directly to student learning of course content, but focus on helping students more fully engage in the learning process.

Support for troubleshooting and orienting helps the student become familiar and comfortable with the course platforms, tools, expectations, and procedures. Ability to effectively use course platforms and tools is essential, as “inability to interact successfully with the technology will inhibit… active involvement” in course activities (Hillman et al. 1994), especially in fully online courses that rely heavily or entirely on mediated interactions. In fact, de la Varre et al. (2014) found technological issues a major contributing factor to students dropping out of an online course.

As students commonly underestimate the time and effort required to complete online learning activities (McClendon et al. 2017), they may also require support orienting them to the rigors of online and blended learning along with the learning strategies that will help them to be successful. In addition to the rigors of online and blended learning and the skills required to be successful, those who provide orienting support must understand the attributes and background of the learner. Thus, students and instructors who are experienced in learning online comprise important communities to provide advising and orienting support. Those who share the physical space with the student can be especially helpful when troubleshooting technological issues.

Organizing and managing is another form of support for improving behavioral engagement in online and blended learning. Students are often unprepared to learn in highly flexible learning environments. Success in these courses depends in part on the student’s ability to manage time and environment (Michinov et al. 2011) and to prioritize tasks; thus support these areas can be critical (Hendrix and Degner 2016; Repetto et al. 2010).

While the internet is essential in online and blended courses, it also provides countless digital distractions that challenge time management (Cho and Littenberg-Tobias 2016). Social media can be especially distracting; even while students are not actively using social media, associated issues and content cause mind wandering (Hollis and Was 2016). When learning outside of a structured physical classroom, online and blended students may also require support to help them organize and manage their physical learning environment (Borup et al. 2015).

Monitoring and encouraging progress is another form of support for improving behavioral engagement. A primary advantage of online and blended learning is for students to have some control over their learning pace. Some online courses provide only recommended pacing benchmarks but no hard deadlines except the end of the semester. Lacking deadlines makes it easier for students to procrastinate, which, of course, is negatively correlated with online course performance (Michinov et al. 2011). The more flexibility available in pacing, the more support some students will need in monitoring their progress to ensure on-time completion. When a student’s progress is insufficient, others can offer encouragement; depending on the relationship, incentives or punishments may be set (Borup et al. 2015).

Support elements for affective engagement

Students may have difficulty with affective engagement if they do not value the course topic or expect to succeed (Wigfield and Eccles 2000). Also blended and online students can feel isolated and disconnected from the course when they do not receive adequate communication (Symeonides and Childs 2015). Thus, actors can support a student’s affective engagement by facilitating communication and developing relationships.

Because communicating online requires different skills than doing so in person, online and blended learning students may lack the necessary skills and confidence. Supporting communication can include helping students understand and practice netiquette guidelines, but even students who have the necessary knowledge and skills may be reluctant to communicate online. These students may require encouragement or need someone else to initiate communication with them or even on their behalf (Borup and Stimson 2019).

Students may also need help beyond facilitating communication to help them develop relationships. Online communication can be impersonal, in part due to lacking interpersonal cues that help develop sense of immediacy. To strengthen relationships while online, participants need to establish their social presence: “the ability of participants… to project their personal characteristics into the community, thereby presenting themselves to the other participants as ‘real people’” (Garrison et al. 2000, p. 89). While social presence is important, alone it is not sufficient. As Repetto et al. (2010) noted, “All human communities should be characterized by the value and care they invest in their members” (p. 95).

Discussion

Lokey-Vega et al. (2018) posited, “Any discipline that perceives itself as scholarly gives theory a substantial consideration” (p. 71). Graham et al. (2014) added that frameworks are especially valuable in developing knowledge because “by their very nature [they] attempt to establish a common language and focus for the activities that take place in a scholarly community” (p. 13). Frameworks can also guide researchers’ efforts to identify research questions, to collect data, and to analyze and interpret data (Mishra and Koehler 2006). In fact, frameworks are indicators of the maturity and strength of a field of inquiry (Graham et al. 2014).

While online learning has established helpful frameworks, the field of blended learning has lagged behind despite its popularity in both K-12 and higher education (Graham et al. 2014). Furthermore, established frameworks tend to focus only on activities or interactions within the course and ignore the influence of actors outside the course on student learning. And most frameworks have been developed with higher education environments, ignoring the unique characteristics of K-12 students and contexts. The ACE framework is intended to draw attention to communities and actors both within and outside of the course as well as those who work with the student in person and online. While there are important differences between K-12 and higher education, the core constructs of the ACE framework likely exist in both, with implications that can help guide both research and practice.

Implications for practice

A strength of this new ACE framework is that it provides a clearer understanding of a student’s support communities, including how actors within those communities can promote the student’s engagement. By understanding important factors affecting students’ communities, practitioners can attend to designing and building each support community more explicitly. One of the strengths of a student’s personal community support is that it is not course bound. Too often relationships formed during a course end with that course. More effort should be made to develop strategies in online and blended programs for a student to carry forward learning and relationships from one course to another (Noddings 1984). For instance, student cohorts are increasingly used as a retention intervention (Martin et al. 2017). However, more work is needed to develop best practices for establishing student–student relationships and leveraging those relationships to improve student engagement.

Based on the chosen model of learning, the course community should clearly highlight their available support and their expectations for a student’s personal community. A student’s engagement is likely to increase with better integration of personal and course communities. While personal community actors are typically separate from the course community, actors within the course community may foster support from a student’s personal support community. For example, family actors are more likely to engage in a student’s learning when course community actors extend specific invitations to do so (Hoover-Dempsey et al. 2005). Online and blended programs can provide resources to help family actors understand the challenges of learning online and ways that they can help the students to more fully engage in the course. When appropriate, learning and behavior data can be provided to actors such as parents within students’ personal community to enable them to better monitor and motivate student engagement (Borup et al. 2019b).

The ACE framework has the potential to help researchers and practitioners understand both workings of online and blended courses and ways “to improve how things work” (Stake 2010, p. 14). The framework can also help direct students to courses in which they are most likely to succeed. When students are asked if online learning is right for them, this question assumes that online courses are all relatively similar. Rose et al. (2015) explained that “this is clearly the wrong question. Rather than, ‘Is online learning right for you?’ students should consider, ‘What support systems do you need to be successful in online learning?’” (p. 75). This “simple” question requires a complex response. The student (or person advising the student) must first understand the level of engagement required to reach the individual’s goals in a particular course, then estimate the student’s ability to independently engage in the course. If the student is unlikely to reach these goals independently, available support from the course community and the students’ personal community should be considered in terms of being sufficient for student success.

In previous research, we found considerable variety in types of support provided by the course community. In independent study models, students have little to no interactions with online peers and limited access to an online instructor who may or may not proactively monitor and initiate student interactions (Oviatt et al. 2016, 2018). In other online courses and programs, students are provided with rich and continuous learner-instructor (Borup et al. 2014a; Borup and Stevens 2016) and learner–learner interactions (Borup 2016b).

Additionally, models should be explored that blend support from the online instructor with personalized in-person support from individuals who are experts in the course content and/or in facilitating the learning process (see Taylor et al. 2016). This model has been particularly effective with K-12 students, especially when the in-person facilitators have received professional development (Hannum et al. 2008). Similar models have also proven effective for adult learners. An example can be seen in changes occurring in massive open online courses (MOOCs). Where students have received little or no personal support from the instructor and possibly only peer interaction, the inadequate support has been reflected in low student pass rates, even for determined students who indicated that they intended to pass the course. To improve student engagement and pass rates, increasing numbers of MOOC students are now attending MOOC camps where they are able to meet in person with facilitators and other MOOC participants (Maitland and Obeysekare 2015).

The ACE framework highlights communities that have often been overlooked in online settings, particularly within higher education. When ACE is applied, instructors and program faculty can assess (a) students’ situation in terms of cognitive, behavioral, and affective engagement, (b) additional supports they may need, and (c) ways to cultivate both personal and course communities to help provide necessary assistance. For instance, an increasing number of students are requiring additional course-related support through academic mentors and dedicated staff in addition to help from their instructors. One of the largest universities in the United States, Arizona State University (ASU), with over 30,000 full-time online students, has begun to integrate academic success coaches to work one-on-one with students, helping them navigate online courses and degree programs. The role of the success coach is to foster community, motivate students, help with goal setting, provide time management strategies, and offer additional support for keeping students on track, including connecting students to various resources at ASU. This course community support beyond the role of the instructor demonstrates how the framework can be applied to increase persistence and completion of course and program requirements among students (ASU 2017). Due to this systematic effort to improve and expand the course community by adding success coaches and peer mentors, the university’s freshman retention rate, a reliable indicator for future graduation, increased 11 points over the past 15 years to 85.2% in 2018 (Faller 2018).

However, limited resources may prevent expanding the course community by broadly adding personnel and infrastructure. If additional course community supports are limited, students can still reach their goals by receiving support from their personal community (Oviatt et al. 2018; Borup et al. 2019b). Unfortunately, students’ personal community support varies considerably, influenced by actors’ educational experiences, skill levels, support models in their own lives, and other demands on their time, in addition to whether they are invited to support by the student and the course community, and the extent of their self-efficacy to actually improve student engagement (Hoover-Dempsey et al. 2005). Despite differences, both K-12 and higher education models would benefit from examining the ACE framework and identifying where course community and personal community supports can be leveraged to strengthen learner engagement.

Implications for research

The ACE framework provides a useful perspective for viewing blended and online learning contexts. Considering a learning environment, a scholar can apply the ACE framework structure to analyze personal and course communities and the levels of support provided by each. Doing so can provide a structure for writing descriptive cases as well as categories for analysis. In addition, the ACE framework suggests many opportunities for further research. The following are a few possible research topics:

The role of existing personal communities in students’ engagement

Ways disruption of typical class schedules and terminations may affect learning communities

Differences in support communities for K-12 and higher education students

Effects of these communities on student well-being

Comparative importance of various communities for influencing student engagement, and possible effects of student demographics and characteristics

While qualitative research should not be used to test a framework, it can be helpful to refine and expand on the elements identified in the framework (Merriam 1998), as well as provide transferable cases explaining how these community elements support students. Thus, we encourage qualitative and mixed-methods case studies in a variety of settings. Case studies can lead to identifying community actors and support elements not currently included in the framework. Similarly, case studies may find that some actors and support elements included in the framework have little impact on students’ engagement.

Additionally, researchers should be aware of what Whetten (1989) described as “the competing virtues of parsimony and comprehensiveness” (p. 490) when identifying factors to include in a framework. The goal of the framework should be to highlight best practices, because highlighting all practices would actually prove distracting (Ferdig et al. 2009). One of the primary benefits of frameworks is to help researchers focus on factors that are most and least important (Mishra and Koehler 2006). We also acknowledge that students’ interactions with their personal and course communities could actually inhibit student engagement, and qualitative research may help to identify potential negative factors.

Qualitative research can also help inform development of instruments that can be validated quantitatively. Validated instruments would be especially valuable in efforts to quantitatively identify and measure the communities, actors, and support elements that most impact student engagement and ultimately student success. Similarly, it is especially important for researchers to identify and create validated measures of affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement in both online and in-person learning environments. These instruments and corresponding quantitative research could assist in identifying the types of community support that are most essential for various categories of students in specific types of learning arrangements. For example, it would be supremely beneficial to understand the comparative role of personal and course communities for different stages of a students’ career, and better understand the interplay and the relative importance of each. We may find that these communities grow and wane at different times of a student’s pursuit of lifelong learning. This type of research would help programs to better provide and encourage the elements of support that students require.

Also, when resources are limited, instruments can help to identify the types of support that are provided by the personal community so that the course community can focus on students’ greatest needs that they can best address. Finally, diagnostic tools for ascertaining the strength of a student’s personal and course community, and the readiness of these community members to support the student may lead to understanding about how to grow and prepare the community surrounding a student, and the effects this plays on the students’ learning and engagement.

All of these future research directions could also be conducted within a critical research lens. For example, it would be important to understand differences in how personal communities and course communities support linguistically and culturally diverse learners, and whether greater institutional support is needed for these personal communities. In addition, in more collectivist cultures, the personal learning community of a student may be more expanded than we would expect through our U.S.-centric frames of reference, and this could be critically examined as well.

Finally, our model assumes a sociocultural view on learning through communities, and additional research and theoretical work could explore how the ACE framework deepens sociocultural theories on learning. For example, sociocultural theory argues that students construct understanding through interacting with their context and culture, and the ACE framework better describes this social context. More research could better explore which actors and characteristics of personal and course communities support this important student framing and constructing of knowledge.

ACE framework illustrative examples

In this section, we provide a few examples to illustrate how personal and course communities may function in practice to support students’ engagement. The figures are also included to help readers visualize how the model could be applied. However, because actual case studies have yet to be conducted using the ACE framework, these examples are placed in actual settings but the students represented in Figs. 6 and 7 are hypothetical.

The black triangle represents a student who is able to engage relatively well cognitively but has low potential to independently engage behaviorally or affectively. The student is also enrolled in an independent study program that provides low levels of support. The higher levels of support provided by the student’s personal community were insufficient to close the gap for the student to achieve academic success

This represents a student low in cognitive and behavioral but high in affective engagement. The student has not been successful previously in traditional higher education but has enrolled in the Pathways program because of motivation to succeed. The student’s course community provides extensive support both in person and online, reducing the level of engagement needed from the student’s personal community

K-12 settings: independent study and parent-facilitated courses

While K-12 students enroll in online courses for various reasons, students and schools often turn to online learning to recover credit failed in a traditional in-person learning environment (Watson et al. 2012). Many of these students are capable of engaging cognitively in learning activities, but behavioral issues and low affect for the teacher or subject area prevent them from doing so independently. This type and level of independent student engagement is reflected by the center black triangle in Fig. 6.

Because the reflected student’s ability to engage independently in learning activities is insufficient for academic success, the student is unlikely to succeed if both the course community and personal community support are low. In our previous research we examined an independent study program where students received little behavioral or affective support from the course community (Oviatt et al. 2018), which focused on providing feedback and responding to content-related questions. Thus, the student represented in Fig. 6 would need to receive and accept high levels of support from her personal community to be successful. While students in our research reported that they received high levels of support from their personal community, this support was too frequently insufficient to overcome the lack of course community support. A student in this situation would be more likely to reach academic success if the course community provided more support.

To illustrate, we conducted research at a cyber charter school where teachers were highly proactive at contacting and supporting students (Borup et al. 2014a), in contrast to the independent study model where no such contact was made. Students were also assigned to an online facilitator who helped to increase their affective engagement. However, even with this high level of course-provided support, the teachers found it difficult to support students’ behavioral engagement because they were not physically able to monitor and support students’ efforts (or lack thereof). We found these teachers relied heavily on students’ parents to support them in ways that increased their behavioral engagement. However, when parents are unable to fulfill this responsibility, the type of students represented in Fig. 6 may be most likely to achieve academic success in a learning model where they work with an on-site facilitator and are provided with additional course community supports (see Borup et al. 2019a).

Higher education settings: academic mentors and on-site facilitators

Some students in higher education may be highly motivated to succeed but lack sufficient metacognitive abilities to engage cognitively or self-regulation skills to engage behaviorally. These students may also come from families in which they are the first to attend college or families that lack a tradition of academic success. Such students may have difficulty curating high levels of personal community support other than affective support and encouragement. To succeed academically, these individuals require high levels of support from their course community (see Fig. 7 for an example representing the support required).

We can see the elements of the ACE framework in the Pathway Connect program, administered by Brigham Young University-Pathway Worldwide. The program provides students with high levels of support using an online teacher and an on-site facilitator (Spring 2018). The program is designed for non-traditional adult learners of all ages who have not been able to access higher education through traditional means. It attracts and focuses on serving students who are underrepresented in higher education and thus may be less prepared than typical students for rigorous courses in general or online learning in particular. The program is set apart by its low barriers to admissions (no entrance exam requirement) and low cost, which continues as students matriculate into a fully online program to receive an accredited certificate, associate, and/or bachelor’s degree. Recognizing that these students likely lack the type of personal community support they may require to thrive in the traditional learning environment, the Pathway Connect program provides an extensive support system within the course.

As part of the Pathway Connect program, students participate in a year-long, blended learning experience that provides a course community, combining an online course and weekly in-person “gatherings” where learners study together, teach one another, and provide encouragement. In the online course, a skilled expert instructor delivers curriculum and the students submit assignments, earn grades, and participate as part of the online course community. Each in-person gathering is led by two volunteer facilitators who, though not content experts, are skilled at organizing meetings and supporting and caring for students. The in-person course community (called “gatherings”) exists to support students in their online courses. While the course community exists because of the program and officially ends with the course, many students report that peer relationships formed as part of the program endure after their studies are complete (Spring 2018). Students who report higher levels of support in both of these communities, but especially the in-person course community, also report higher perceived affective and cognitive engagement (Spring 2018).

Conclusion

With the increase in online and blended learning at both K-12 and higher education levels, taking courses online is common. However, this popularity has been accompanied by high attrition rates and frequent failure of students to thrive in such learning environments. A major contributing cause may be inadequate understanding regarding the students’ needs for support, from both a personal and a course community.

The ACE framework, refined and adapted from previous work for broader application, suggests solutions for this need. This framework represents a conceptual understanding of the forms of support necessary to promote students’ academic success as well as the communities that can provide them. Frequently overlooked but pivotal to student learning is the role of families, and the ACE framework highlights this community. Although more commonly recognized at the K-8 level, it is still central throughout secondary school and even into higher education.

Those who teach online as well as those who oversee online programs would benefit from ensuring that adequate support is provided to students regardless of who offers it. Only by carefully examining and promoting affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement and by facilitating the communities providing this support can we ensure the academic success of future generations of online and blending learning students.

References

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks,5(2), 1–17.

Archer, W. (2010). Beyond online discussions: Extending the community of inquiry framework to entire courses. The Internet and Higher Education,13(1–2), 69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.005.

Arizona State University Online. (2017). ASU Online launches success center. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from https://asuonline.asu.edu/newsroom/online-learning-tips/asu-online-launches-success-center/.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc.

Ben-Eliyahu, A., Moore, D., Dorph, R., & Schunn, C. D. (2018). Investigating the multidimensionality of engagement: Affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement across science activities and contexts. Contemporary Educational Psychology,53(1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.01.002.

Borup, J. (2016a). Teacher perceptions of parent engagement at a cyber high school. Journal of Research on Technology in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2016.1146560.

Borup, J. (2016b). Teacher perceptions of learner-learner engagement at a cyber high school. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v17i3.2361.

Borup, J. (2018). On-site and online facilitators: Current and future direction for research. In K. Kennedy & R. Ferdig (Eds.), Handbook of research on K-12 online and blended learning (2nd ed., pp. 423–442). Halifax: ETC Press.

Borup, J., Chambers, C., & Stimson, R. (2019a). K-12 student perceptions of online teacher and on-site facilitator support in supplemental online courses. Online Learning,23(4), 253–280.

Borup, J., Chambers, C., & Stimson, R. (2019b). Online teacher and on-site facilitator perceptions of parental engagement at a supplemental virtual high school. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v20i2.4237.

Borup, J., Graham, C. R., & Drysdale, J. S. (2014a). The nature of teacher engagement at an online high school. British Journal of Educational Technology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12089.

Borup, J., & Stevens, M. (2016). Parents’ perceptions of teacher support at a cyber charter high school. Journal of Online Learning Research.,2, 227–246.

Borup, J., & Stevens, M. A. (2017). Using student voice to examine teacher practices at a cyber charter high school. British Journal of Educational Technology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12541.

Borup, J., Stevens, M. A., & Hasler-Waters, L. (2015). Parent and student perceptions of parent engagement at a cyber charter high school. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Network,19(5), 69–91.

Borup, J., & Stimson, R. (2019). Online teachers’ and on-site facilitators’ shared responsibilities at a supplemental virtual secondary school. American Journal of Distance Education,33(1), 29–45.

Borup, J., West, R. E., Graham, C. R., & Davies, R. S. (2014b). The Adolescent Community of Engagement: A framework for research on adolescent online learning. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education,22(1), 107–129.

Cho, V., & Littenberg-Tobias, J. (2016). Digital devices and teaching the whole student: Developing and validating an instrument to measure educators’ attitudes and beliefs. Educational Technology Research and Development,64(4), 643–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9441-x.

Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (2012). Handbook of research on student engagement. New York, NY: Springer.

de la Varre, C., Irvin, M. J., Jordan, A. W., Hannum, W. H., & Farmer, T. W. (2014). Reasons for student dropout in an online course in a rural K-12 setting. Distance Education,35(3), 324–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2015.955259.

Drysdale, J. S., Graham, C. R., & Borup, J. (2014). An online high school “shepherding” program: Teacher roles and experiences mentoring online students. Journal of Technology & Teacher Education, 22(1), 9–32.

Dziuban, C., Graham, C. R., Moskal, P. D., Norberg, A., & Sicilia, N. (2018). Blended learning: The new normal and emerging technologies. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0087-5.

Faller, M. (2018). ASU helps more students return after freshman year and thrive during college. ASU Now. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from https://asunow.asu.edu/20180828-asu-news-freshman-retention-higher-national-average-thrive.

Farrell, E. F. (2007). Some colleges provide success coaches for students: New kind of adviser helps hone life and study skills. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 53(46). https://www.chronicle.com/article/Some-Colleges-Provide-Success/10133.

Ferdig, R. E., Cavanaugh, C., DiPietro, M., Black, E., & Dawson, K. (2009). Virtual schooling standards and best practices for teacher education. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education,17(4), 479–503.

Filak, V. F., & Sheldon, K. M. (2008). Teacher support, student motivation, student need satisfaction, and college teacher course evaluations: Testing a sequential path model. Educational Psychology,28(6), 711–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410802337794.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research,74(1), 59–109.

Freidhoff, J. R. (2018). Michigan’s k-12 virtual learning effectiveness report: 2016-17. Lansing, MI: Michigan Virtual University. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from https://mvlri.org/research/effectiveness-report/.

Garrison, R. (2009). Implications of online learning for the conceptual development and practice of distance education. Journal of Distance Education,23(2), 93–104.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education,2(2–3), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6.

Gemin, B., Pape, L., Vashaw, L., & Watson, J. (2016). Keeping pace with K-12 online learning. Evergreen Education. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from https://www.evergreenedgroup.com/keeping-pace-reports.

Gill, B., Walsh, L., Wulsin, C. S., Matulewicz, H., Severn, V., Grau, E., …, Kerwin, T. (2015). Inside online charter schools. Cambridge, MA: Walton Family Foundation and Mathematica Policy Research. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/~/media/publications/pdfs/education/inside_online_charter_schools.pdf.

Graham, C. R., Henrie, C. R., & Gibbons, A. S. (2014). Developing models and theory for blended learning research. In A. G. Picciano, C. D. Dziuban, & C. R. Graham (Eds.), Blended learning: Research perspectives (Vol. 2, pp. 13–33). New York: Routledge.

Halverson, L. R., & Graham, C. R. (2019). Learner engagement in blended learning environments: A conceptual framework. Online Learning.,23(2), 145–178. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v23i2.1481.

Hannum, W. H., Irvin, M. J., Lei, P., & Farmer, T. W. (2008). Effectiveness of using learner-centered principles on student retention in distance education courses in rural schools. Distance Education,29(3), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910802395763.

Harms, C. M., Niederhauser, D. S., Davis, N. E., Roblyer, M. D., & Gilbert, S. B. (2006). Educating educators for virtual schooling: Communicating roles and responsibilities. The Electronic Journal of Communication,16(1 & 2), 17–24.

Hasler Waters, L., & Leong, P. (2014). Who is teaching? New roles for teachers and parents in cyber charter schools. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 22(1), 33–56.

Hendrix, N., & Degner, K. (2016). Supporting online AP students: The rural facilitator and considerations for training. American Journal of Distance Education,30(3), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2016.1198194.

Henrie, C. R., Halverson, L. R., & Graham, C. R. (2015). Measuring student engagement in technology-mediated learning: A review. Computers & Education, 90, 36–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.09.005.

Hillman, D. C., Willis, D. J., & Gunawardena, C. (1994). Learner-interface interaction in distance education: An extension of contemporary models and strategies for practitioners. American Journal of Distance Education,8(2), 30–42.

Hollis, R. B., & Was, C. A. (2016). Mind wandering, control failures, and social media distractions in online learning. Learning and Instruction,42, 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.007.

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Walker, J. M. T., Sandler, H. M., Whetsel, D., Green, C. L., Wilkins, A. S., et al. (2005). Why do parents become involved? Research findings and implications. The Elementary School Journal,106(2), 105–130.

Hughes, J. N., Luo, W., Kwok, O.-M., & Loyd, L. K. (2008). Teacher-student support, effortful engagement, and achievement: A 3-year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology,100(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.1.

International Association for K-12 Online Learning (iNACOL). (2011). National standards for quality online courses. Vienna, VA. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from http://www.inacol.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/iNACOL_TeachingStandardsv2.pdf.

Kuh, G. D., Jankowski, N., Ikenberry, S. O., & Kinzie, J. (2014). Knowing what students know and can do: The current state of student learning outcomes assessment in U.S. colleges and universities. Champaign, IL: National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from http://www.learningoutcomeassessment.org/documents/2013%20Abridged%20Survey%20Report%20Final.pdf.

Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Buckley, J. A., Bridges, B. K., & Hayek, J. C. (2007). Piecing together the student success puzzle: Research, propositions, and recommendations. ASHE Higher Education Report,32(5), 1–182. https://doi.org/10.1002/aehe.3205.

Lehan, T. J., Hussey, H. D., & Shriner, M. (2018). The influence of academic coaching on persistence in online graduate students. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning,26(3), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2018.1511949.

Lokey-Vega, A., Jorrín-Abellán, I. M., & Pourreau, L. (2018). Theoretical perspectives in K-12 online learning. In K. Kennedy & R. Ferdig (Eds.), Handbook of research on K-12 online and blended learning (2nd ed., pp. 403–422). ETC Press. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from http://press.etc.cmu.edu/index.php/product/handbook-of-research-on-k-12-and-blending-learning-second-edition/.

Lowes, S., & Lin, P. (2015). Learning to learn online: Using locus of control to help students become successful online learners. Journal of Online Learning Research,1(1), 17–48.

Ludwig-Hardman, S., & Dunlap, J. C. (2003). Learner support services for online students: Scaffolding for success. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v4i1.131.

Macfarlane, B., & Tomlinson, M. (2017). Critical and alternative perspectives on student engagement. Higher Education Policy,30(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-016-0026-4.

Maitland, C., & Obeysekare, E. (2015). The creation of capital through an ICT-based learning program: A case study of MOOC camp. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development. Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1145/2737856.2738024.

Martin, K. A., Goldwasser, M. M., & Galentino, R. (2017). Impact of cohort bonds on student satisfaction and engagement. Current Issues in Education,19(3), 1–14.

McClendon, C., Massey Neugebauer, R., & King, A. (2017). Grit, growth mindset, and deliberate practice in online learning. Journal of Instructional Research,6, 8–17.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education: Revised and expanded from case study research in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Michinov, N., Brunot, S., Bohec, O. Le, Juhel, J., & Delaval, M. (2011). Procrastination, participation, and performance in online learning environments. Computers & Education,56, 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.07.025.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record,108(6), 1017–1054.

Moore, M. G. (1980). Independent study. In R. Boyd & J. Apps (Eds.), Redefining the discipline of adult education (pp. 16–31). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Moore, M. G. (1989). Three types of interaction [Editorial]. American Journal of Distance Education,3(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923648909526659.

Mountford-Zimdars, A., Sabri, D., Moore, J., Sanders, J., Jones, S., & Higham, L. (2015). Causes of differences in student outcomes [White paper]. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from King’s College London: http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/23653/1/HEFCE2015_diffout.pdf.

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Oldfield, J., Rodwell, J., Curry, L., & Marks, G. (2019). A face in a sea of faces: Exploring university students’ reasons for non-attendance to teaching sessions. Journal of Further and Higher Education,43(4), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1363387.

Oviatt, D., Graham, C. R., Borup, J., & Davies, R. S. (2016). Online student perceptions of the need for a proximate community of engagement at an independent study program. Journal of Online Learning Research,2(4), 333–365.

Oviatt, D. R., Graham, C. R., Davies, R. S., & Borup, J. (2018). Online student use of a proximate community of engagement in an independent study program. Online Learning,22(1), 223–251.

Repetto, J., Cavanaugh, C., Wayer, N., & Liu, F. (2010). Virtual high schools: Improving outcomes for students with disabilities. Quarterly Review of Distance Education,11(2), 91–104.

Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (2012). Jingle, jangle, and conceptual haziness: Evolution and future directions of the engagement construct. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 3–19). New York: Springer.

Roblyer, M. D., Freeman, J., Stabler, M., & Schneidmiler, J. (2007). External evaluation of the Alabama ACCESS initiative phase 3 report. Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology in Education. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from http://accessdl.state.al.us/2006Evaluation.pdf.

Roksa, J., & Kinsley, P. (2018). The role of family support in facilitating academic success of low-income students. Research in Higher Education,60(4), 415–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9517-z.

Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., Split, J. L., & Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher-student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Review of Educational Research,81(4), 493–529. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311421793.

Rose, R. M., Smith, A., Johnson, K., & Glick, D. (2015). Ensuring equitable access in online and blended learning. In T. Clark & M. K. Barbour (Eds.), Online, blended, and distance education in schools: Building successful programs (pp. 71–83). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Rovai, A. P. (2003). In search of higher persistence rates in distance education online programs. Internet and Higher Education,6, 1–16.

Seaman, J. E., Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2018). Grade increase: Tracking distance education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED580852.

Shephard, K. (2008). Higher education for sustainability: Seeking affective learning outcomes. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education,9(1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676370810842201.

Skinner, E., Furrer, C., Marchand, G., & Kindermann, T. (2008). Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: Part of a larger motivational dynamic? Journal of Educational Psychology,100(4), 765–781. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012840.

Skinner, E. A., & Pitzer, J. R. (2012). Developmental dynamics of student engagement, coping, and everyday resilience. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 21–44). Boston, MA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_2.

Skinner, E. A., Wellborn, J. G., & Connell, J. P. (1990). What it takes to do well in school and whether I’ve got it: A process model of perceived control and children’s engagement and achievement in school. Journal of Educational Psychology,82(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0663.82.1.22.

Spring, K. J. K. (2018). Academic Communities of Engagement and Their Influence on Student Engagement (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University.

Stake, R. E. (2010). Qualitative research: Studying how things work. New York: Guilford Press.

Su, J., & Waugh, M. L. (2018). Online student persistence or attrition: Observations related to expectations, preferences, and outcomes. Journal of Interactive Online Learning,16(1), 63–79.

Symeonides, R., & Childs, C. (2015). The personal experience of online learning: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Computers in Human Behavior,51, 539–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.015.

Taylor, S., Clements, P., Heppen, J., Rickles, J., Sorensen, N., Walters, K., …, Micheiman, V. (2016). Getting back on track: The role of in-person instructional support for students taking online credit recovery (Research Brief 2). Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from https://www.air.org/system/files/downloads/report/In-Person-Support-Credit-Recovery.pdf.

Trowler, V. (2010). Student engagement literature review [White Paper]. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from The Higher Education Academy: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_url?url=https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6d0c/5f9444fc4e92cca76fe9f426bd107e837a9f.pdf&hl=en&sa=X&scisig=AAGBfm3WmhAV9GCJ8rx8hzFi9SZoBMiOYw&nossl=1&oi=scholarr.

Tze, V. M. C., Daniels, L. M., & Klassen, R. M. (2016). Evaluating the relationship between boredom and academic outcomes: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review,28, 119–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9301-y.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, Ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Watson, J., Murin, A., Vashaw, L., Gemin, B., & Rapp, C. (2012). Keeping pace with K-12 online and blended Learning: An annual review of policy and practice. Evergreen Education Group. Retrieved February 10, 2020, from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59381b9a17bffc68bf625df4/t/5949b5db725e25cad52277e2/1498002924767/KeepingPace+2012.pdf/.

Wefald, A. J., & Downey, R. G. (2009). Construct dimensionality of engagement and its relation with satisfaction. The Journal of Psychology,143(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.3200/JRLP.143.1.91-112.

Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical dontribution? The Academy of Management Review,14(4), 490–495. https://doi.org/10.2307/258554.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology,25, 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Kitsantas, A. (1997). Developmental phases in self-regulation: Shifting from process goals to outcome goals. Journal of Educational Psychology,89(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0663.89.1.29.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Research involved in human or animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors and no informed consent was necessary. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Borup, J., Graham, C.R., West, R.E. et al. Academic Communities of Engagement: an expansive lens for examining support structures in blended and online learning. Education Tech Research Dev 68, 807–832 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09744-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09744-x