Abstract

Drawing on ecological and dialogical perspectives on language and cognition, this exploratory case study examines how vocabulary learning occurs during a quest-play mediated in English between a Japanese undergraduate student and a native speaker of English. Understanding embodiment as coaction between the player-avatar and player–player relations (Zheng and Newgarden 2012; Zheng et al. 2012), as situative embodiment in a perceptually and narratively rich context (Barab et al. in Sci Educ 91:750–782, 2007), and as a dialogical achievement (Zheng and Newgarden 2012; Zheng et al. 2012), this research provides an alternative explanation of how players embodied in their avatars appropriated semiotic resources imbued in World of Warcraft (WOW). Two hours of co-quest play provided instances of vocabulary learning unique to the WOW environment and co-play. Through iterative multimodal analysis, vocabulary learning became salient as we analyzed both chat and avatar action data and provided a thick description and dynamic process of co-play. Using the eco-dialogical model, we display how language learning as appropriation of resources and as result of eco-dialogical embodiment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Traditional language teaching methods reduce language into learnable units: grammar or vocabulary drilled by rote in grammar-translation or functions and topics in more communicative methods. Learners have limited contexts in which to engage in skilled linguistic action—a full coordination between form, meaning, pragmatics and emotions—which is necessary and consequential in a given action for pursuing learning goals (Cowley 2013; Newgarden et al. 2015). Instruction of lexicogrammar knowledge usually follows a linear path of abstract knowledge to which second language learners cannot relate through embodied experiences. Even action-based curriculum reduces meaningful communication through imagined production lacking situated embodiment in rich contexts (Barab et al. 2007). Furthermore, current models of second language acquisition and use assume that language must be acquired before it can be used (Linell 2009). This underlying problem permeates research such that mainstream instructed SLA focuses on acquisition of code-like language in individual brains.

In contrast, emergent embodied cognitive science prioritizes materiality, embodiment, and co-actionality, collectively referred to as Distributed Cognition/Language (Cowley 2012; Gibson 1979; Hodges 2009; Hutchins 1995; Steffensen 2013). “The distributed perspective challenges the mainstream view that what we do with language can be explained by individual competencies or microsocial rules” (Distributed Language Group, n.d.). Language permeates beyond individual brains to co-construction in dialog, manipulation of objects, and gestures and body movement, which give meaning and values dynamically (Järvilehto 2009). This view suggests a need for meaningful and sustainable learning and co-actionality in situ, with whole body sensory involvement and immersion in social, cultural, and historical artifacts.Footnote 1

Whereas traditional computer assisted language learning (CALL) software is designed specifically for language learning, users can purpose Web 2.0 tools however they wish by seeking their own materials and cohorts and collaboratively producing text and multimedia online. Web 2.0 tools thus help learners use appropriate lexical items, syntax, or rhetoric (Sykes et al. 2008). Focusing specifically on one Web 2.0 application, the present study addresses vocabulary learning in World of Warcraft (WOW), a massively multiplayer online game (MMOG). Scholars have examined language learning in other MMOGs through vocabulary acquisition (Rankin et al. 2006), achievement (Suh et al. 2010), and attitudes (Zheng et al. 2013), but studies focused specifically on WOW (Rama et al. 2012; Thorne 2008; Zheng et al. 2012) have not probed vocabulary learning. Because the collaborative play environment of MMOGs offers meaningful contexts for language use and practice (Thorne 2008), as opposed to the decontextualized traditional classroom, we depict the vocabulary learning process through an eco-dialogical lens (Zheng 2012). This research orientation centers on understanding how language learning occurs in the particular space and time, rather than demonstrating evidence of improvement of vocabulary learning. Building on a framework of eco-dialogicality, this study extends Zheng’s (2012) theorizing of caring in the dynamics of virtual space and activities design and languaging to consider one specific phenomenon among the rich tapestry of communicative activities afforded by WOW (Zheng et al. 2012), vocabulary acquisition. We examine social gameplay in MMOGs and the implications for language learning through the players’ coordination of their actions in two languages. Using multimodal analytical tools, we analyze chat and avatar action data to answer the following research questions:

-

1.

How do language learners appropriate resources in co-play between a new and an expert player?

-

2.

What does vocabulary learning look like within an eco-dialogical framework?

Background

Second language acquisition and MMOG studies of vocabulary learning

Much past research both in and out of game-based environments has used mainstream second language acquisition (SLA) theories based on computational assumptions of learners processing a fixed code of input and output. Taking this SLA perspective, experimental work by deHaan (2005) and deHaan et al. (2010) examined specific constructs such as vocabulary learning through video games, but these studies isolated learners from a natural gameplay environment. deHaan et al. (2010) found that video game players retained less vocabulary than did watchers. Ranalli (2008) found the opposite when supplementary learning materials accompanied gameplay. Interaction between native and non-native English speaking dyads created a positive effect on L2 vocabulary acquisition (Rankin et al. 2009).

Aside from Rankin et al. (2009), however, participants were denied incidental opportunities to learn vocabulary. They were unable to interact within a wider community of practice (Piirainen-Marsh and Tainio 2009; Ranalli et al. 2013; Squire 2008) where players discuss characters, levels, or other topics. These factors are part of linguistic and social environments that are rich in action potentials for learners (Peterson 2010; Rama et al. 2012; Thorne 2008; Zheng et al. 2012), factors missed by game writers concerned instead with providing linguistic “inputs.” Non-experimental research has similarly failed to provide thick description of the eco-dialogical processes by which vocabulary learning takes place.

Some non-experimental work has focused on constructs such as achievement, agency, or general L2 proficiency. Suh et al. (2010) found that elementary school-aged children in Korea had higher achievement scores in instruction through an MMOG called Nori School than in face-to-face classroom instruction. Analyzing learners’ actions and agency in virtual environments, Peterson (2010) found that while L1 Japanese learners of English could initiate target language interactions with native speakers in Allods Online, those without prior MMOG experience or with lower language proficiency had trouble contributing. Sylven and Sundqvist (2012) found that L2 proficiency (reading, listening, and vocabulary) correlated positively with frequency of gameplaying in extramural English L2 learning.

While all the above studies report benefits of gameplay in the outcomes of language proficiency, they still do not reveal the process by which gamers gain that higher proficiency. Thus, there is a gap in the literature concerning how language learners can appropriate resources for successful gameplay and learning in MMOGs and the implications resource appropriation has on their learning both in and outside of the virtual environment.

World of Warcraft

MMOGs are rich in linguistic text, and communication with other players is central to gameplay experience, so players of MMOGs not only learn language, but also develop multimodal literacy skills that are essential in the digital present. Modern media allow meaning to be conveyed through an interspersing of words, images, and use of space (Gee 2003). Video games in particular are fertile sites for learning and developing an expanded notion of what it means to be literate in the 21st century (Gee 2003). Like many MMOGs, WOW is replete with resources for learning. An important affordance in WOW is questing. Quests, specific tasks given to players by the game environment, afford different negotiations for action (Zheng et al. 2009) depending upon the quest requirements and provide structure in what is otherwise a very open and free world. Quests may be undertaken collaboratively with other players, thus creating a need to coordinate and communicate (Zheng and Newgarden 2012) and attend to game environment resources.

Other resources in WOW work in concert with quests. Players manipulate their avatars to perform actions such as attacking, healing, or taking treasure from slain enemies. Quest and game logs explain what players must do to complete a quest and situate the quest within the larger lore of the game world. In addition, WOW’s text chat box and system logs (located at the bottom left of the screenshot depicted in Fig. 1) present important information to players. The system logs (indicated within box A in Fig. 1) of players’ actions display dynamic information from non-playing characters (NPCs) as in-game dialogue. The chat box (indicated within box B in Fig. 1) allows sending and receiving messages visible to different groups of players. Players can take as much time as they need to construct messages, and other players tolerate errors in spelling or syntax, which is advantageous to language learners’ in-game communicative competence (Rama et al. 2012).

The surrounding 3D graphic environment offers players forests, cities, and other locales to explore. The way in which players and NPCs appear and disappear from the environment is itself a potential resource. When monsters or players are killed, their corpses remain briefly in the game environment (to be either looted or revived) before disappearing from the landscape. New monsters materialize out of thin air, a concept players call “popping.” Zheng et al. (2012) reported a rich tapestry of communicative activities afforded by different types of activities, landscapes, and places, such as “Gameplay knowledge distributing, Reporting on actions, and Responding with language or action” during travel, and there is a concentration of communicative activities for “Coordinating, Expressing need, Distributing gameplay knowledge, Understanding others’ perspective, Reporting on actions, Seeking help, and Responding with language and/or action” (p. 350). These activities illustrate the myriad opportunities for language learning available in an MMOG environment like WOW.

Ecological-dialogical embodiment to language learning

In contrast with the SLA perspective, this study assumes an ecological theory of language learning derived from Gibson’s (1979) ecological psychology theory of direct perception. Key to this theory are affordances, defined as “what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill” (Gibson 1979, p. 127). For example, upon seeing keys printed with letters and numbers, technologically literate people perceive a laptop keyboard as an input affordance for the computer and type. However, a pet cat perceives the keyboard’s flatness and warmth as an ideal napping affordance. Extended to language learning in terms of ecological perspectives, van Lier (2004) defines affordances as things available to learners to do something with. They are a potential for action by the learner; perception, action, and interpretation are in a cyclical relationship with learners’ environment (van Lier 2004).

Through ecological theory, language learning is not discrete units and objects such as grammatical rules or vocabulary but rather first-order languaging, which Thibault (2011) defines as “the focus on the dynamics of real-time behavioral events that are co-constructed by co-acting agents rather than the more usual view that persons ‘use’ a determinate language system or code” (pp. 2–3). Thus, instead of learning about language in terms of second-order (Thibault 2011) constructs such as words or phrases, taking an ecological perspective reveals how learners engage in learning to be (Brown 2005), through first-order languaging, as they apprentice and enculturate in real social contexts (Zheng 2012; Zheng et al. 2012). They engage with interlocutors and socio-cultural artifacts within a situation and with absent third parties (Linell 2009) or other imagined socio-cultural situations and environments across timescales of past, present, and future.

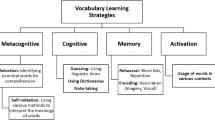

Zheng’s (2012) model of ecological dialogical language development (Fig. 2), with the action-perception cycle of the environment working around the languaging behavior, views language learning as potentially situation-transcending. Learners do not merely learn lexico-grammar from a teacher in a classroom in the situated “here,” but can move beyond, making use of resources in the environment and in their own experiences in a situation-transcending “not-here.” Dufva (2013) further argues that “learning occurs in collaboration and [is] mediated by other people and/or different tools and artefacts of the social world” (p. 2) and is a process through which learners appropriate resources across time and space, social situations, and contexts.

Zheng’s (2012, p. 546) Eco-dialogical model

Relevant to CALL research, studies of multimodal resources and affordances in MMOGs (Rama et al. 2012; Zheng et al. 2012) have found that the design of these game environments can promote communicative activities and provide opportunities for learning that cannot be easily replicated in a classroom. Zheng (2012) argues that MMOGs can “provide learners with social, historical, and cultural materials to augment action and interaction across space and time” (p. 557). These rich contexts allow learners to experience situative embodiment, “fostering a deep sense of embodiment in which the learner enters into a situation narratively and perceptually, has a goal, has a legitimate role, and engages in actions that have consequence” (Barab et al. 2007, p. 751).

These perspectives, namely affordances, situation-transcending first-order languaging with a projective stance, and situative embodiment, focus on relationships rather than objects, relationships van Lier (2004) suggests are both between language and the physical and social environments and between the learner and the learning context. This paper utilizes ecological-dialogical embodiment to frame the research questions, analysis, and discussion. We thus move away from computational models of cognitive science and mainstream SLA approaches that locate individual cognition and learning as a unit of analysis, to place emphasis on human interactivity as a unit of analysis. Cognitive and communicative activities are equally dependent on other individuals and artifacts or tools (Farr et al. 2012; Hutchins 1995). Specifically, we demonstrate how vocabulary learning arises in WOW game play by relating players’ coordination with other players, artifacts, and situation narrative (game world lore). This approach aligns with Zheng and Newgarden’s (2012) theorization of embodiment in terms of two inseparable layers of coaction afforded by 3D virtual environments: coaction within avatar and player, and between avatar and other avatars.Footnote 2

It is also worth distinguishing between research on Computer-Medicated Communication (CMC) and communication for coordination. The established research on CMC mainly relies on discourse or conversational analytical tools to look at characteristics of language use and interaction for language learning mediated by electronic devices and applications, such as email, audio/text chat, or list-serv. These media are usually based in text or audio technology, and the environment in which communication takes place is a simple interface for text-or audio-based interaction, such as Skype. CMC research is still biased towards prioritizing the linguistic modality. In comparison, communication for embodied coordination, on which this research centers, recognizes the full multimodal capacity of the WOW environment, calling for a new way to look at the role of language and language learning. On the one hand, under the umbrella of the eco-dialogical framework, media and tools shape ways of communication and action potentials. On the other, WOW is a multimodal medium that is rich in resources for coordination as mentioned in the previous section. With these two groundings, this work steps away from traditional studies of CMC and looks at language learning when learners are engaged in socially embedded and actionally embodied activities in WOW. The construct of languaging encompasses not just coordination with language to negotiate next action, but also meta gaming languaging relevant to advancing WOW gaming knowledge, and avatar actions.

Method

This case study examines one 2-hour gameplay session in which the object of study (Merriam 1998) is Conan’s learning to be a WOW player. This single session provides more than adequate data, as Conan and Mediziner played twelve quests and engaged in twenty-four communicative projects (Linell 2009), to reveal a process of vocabulary learning through ecological-dialogical embodiment. The case is bounded at the beginning with Conan’s first participation in the game and at the end with the two players’ mutual agreement that Conan had learned gameplay basics enough to play on his own in the future.

One may find two hours of game play may limit the scope of generalizing findings for claiming new ways of vocabulary learning. However, our method is one of abductive reasoning (Magnani 2004; Newgarden et al. 2015; Peirce 1982; Zheng 2012; Zheng et al. 2012) in that we rely on theoretical grounding, multimodal text, and context to identify saliency. Such a process is highly contextual, and requires more than a “leap of faith” to make selective decisions (Levinson 1995). Dependability was accounted for through contextual judgments and alignment with the conceptual framework to ensure consistent and systemic coding and analysis.

Participants

This paper reports a case study of two players’ (one a native speaker of Japanese and the other of English) coordination of gameplay (mostly in English and sometimes English-Japanese translanguaging). In the eco-dialogical framework, both players, as well as the WOW resources, are considered as parts of the eco-system. There are distinct individual biographies that contributed to the interactivity, and specific affordances of certain resources are actualized for certain actions (Linell 2009). However, there is no distinction of participants and researchers in terms of particular competencies, but rather the emphasis is on how coordination and communication are accomplished by appropriating all aspects of resources. Therefore, it is necessary to trace each player’s background relevant to game play and languaging experiences.

At the time of data collection, Conan (pseudonym), a Japanese national, was an undergraduate student in the United States. Having studied English for 9 years, he had achieved a high level of proficiency in his L2 and was taking content courses in English at the university. He said that he liked to play video games and had played English-language video games to help in learning English, but had never played an English-language MMOG prior to the study. Thus, Conan was a novice player in WOW.

Author 2 (Bischoff) joined in the gameplay as a participant observer and co-player with the avatar name Mediziner. An L1 speaker of English, he was a graduate student in applied linguistics at the time of the study. He had studied Japanese as an L2 as an undergraduate; through living and working in Japan as an English instructor, he had achieved intermediate proficiency in Japanese. Author 2 is also an experienced video game player and had played other MMOGs at a high level. At the time of the study, he had limited previous experience in WOW, having played for about thirty levels, long enough to be familiar with the basic mechanics and systems the game. As the expert WOW player in the dyad, he offered Conan advice and assistance regarding the game world ontology and explained unfamiliar vocabulary Conan encountered. Mediziner joined Conan in completing tasks and quests in the game.

Materials

This study was primarily conducted within the game environment of WOW. As of the time of writing this paper, WOW was the most popular MMOG in the world (Activision Blizzard 2014), with 7.8 million subscribers from around the world. Developed and maintained by Blizzard Entertainment, WOW is typical of the MMOG genre. WOW is set in the virtual world of Azeroth, a land torn between the forces of the Alliance and the Horde. One of the first acts of the game is avatar creation, in which players choose which side to play for and which race to play as. Players then select a combat class such as Warrior or Mage (i.e. front line attacker or back line support), which not only defines their role in battle, but can also affect the kinds of role-playing players engage in. Players’ avatars are then placed in the starting city for their chosen race, and the entire world is open to explore. This rich detail immerses players within the world and provides a basis for all their actions: completing quests, delving into the complex economic system of the game world, or slaying monsters for fun and profit. This explicit structure is exactly what Thorne (2008) argued MMOGs exhibit. To facilitate installation and setup of WOW, Mediziner used Skype for instant message (IM) communication with Conan prior to gameplay. Skype also served as backup communication when unexpected technical problems with WOW required logging out of the game.

Data and procedures

The data in this study come from co-play between Conan and Mediziner. Demographics, including players’ gameplay background, foreign language learning experiences, and current status, serve as data points for an eco-dialogical framework. The main data were collected directly from in-game interactions and text instant messages in Skype. TechSmith’s Camtasia screen recording software was used on Mediziner’s computer to record nearly 2 hours of gameplay. The multimodal data sets record communication and action between players displayed in the chat logs and system logs. Chat logs display players’ languaging resulting from coordination. System logs display critical information about what was happening in the game world, such as damage players dealt a monster or their success in crafting an item. Both logs represent key WOW design and grammar features that capture dynamic player–player and player-WOW interaction. When playing together, Conan and Mediziner primarily communicated through the /whisper command, a private chat channel.Footnote 3

Another mode of interaction is the visual depiction of the game world, with the screenshot in Fig. 1 showing a typical scene from WOW. Players can manipulate the camera to look around in all directions and choose whether to view their avatar from a third-person perspective or to see the world from their avatar’s first-person view. Because we could not record Conan’s screen, Mediziner remained in close visual proximity with Conan as a participant observer. Data analysis and results thus are based on the screen recording of Mediziner’s screen.

Transana, a multimodal transcription tool, was used for transcription and analysis. The transcription conventions used to produce the chat logs can be found in Appendix 1. Due to a technical error, timestamp logs were not automatically generated, so text chat data were transcribed manually. The transcript included not only the textual linguistic turns taken between Conan and Mediziner, but also details such as actions of the players’ avatars or avatars’ orientation toward one another and other artifacts in the game environment.

Our data analysis takes a dialogical theory of communicative projects (CPs) (Linell 2009) as an alternative to studying utterances as links in chains or as monological speech acts. A project in action is often centered around a task that required concerted effort by two or more individuals. “A project is dynamic through its course-of-action; it progresses through different phases or moments, such as planning, development, performance and retrospective evaluation” (Linell 2009, p. 190). Within a CP, the smallest analytical unit includes three utterance turns taken by persons A and B (in the form of ABA) as the minimal communicative interaction.

Guided by work by Zheng and colleagues (Newgarden et al. 2015; Zheng 2012; Zheng et al. 2012) on methodological integration and advancement of multimodal transcription and text analysis tools (Baldry and Thibault 2006) and using the CP as a unit of analysis (Linell 2009), we identified salient vocabulary learning examples situated in CPs, resulting from verbal utterances, text chat, and avatar movements. Multimodal analysis is concerned with perceptually salient features in that structures repeat themselves in a patterned way and allow variance within a fixed framework. When a salient pattern was identified based on contextual flow of CPs, analysis took into consideration events before and after the focal CP. We identified five CPs that we considered evidence of vocabulary learning. To achieve dependability, analysis was extended to more than two adjacent CPs as needed. Furthermore, analysis was co-conducted between Authors 1 and 2 (Zheng and Bischoff), and findings were confirmed through following up with the research participant.

Findings and discussion

In this section, we first outline the overall trajectory of the gameplay session between Conan and Mediziner and then provide a multimodal account of how WOW supports vocabulary learning in three specific instances.

Summary of gameplay

After Mediziner used Skype to direct Conan’s installing the WOW software client and creating his avatar, both players logged into the game and discussed which combat classes to play as. Conan chose Warrior, taking on the role of attacker. To support Conan, Mediziner chose Priest, a healing class. Their avatars appeared in a forest in Northshire, a common starting ground for new players of the game. Mediziner and Conan added one another as friends in-game to communicate privately with one another; Mediziner then demonstrated to Conan game basics such as moving his avatar around.

They next completed some quests that teach new players like Conan basic gameplay mechanics of WOW. Mediziner showed Conan how to speak with and accept quests from NPCs (non-player characters), how to battle enemies and retrieve items from their corpses after defeating them (looting), and how to tell player characters apart from NPCs. After these orientation quests, Conan and Mediziner co-played the following quests in which we identified representative occurrences of vocabulary learning. We numbered these major quests to index the context in which the vocabulary learning example occurred, but they are not necessarily played in this order depending on avatars’ role and level. To distinguish them from training quests, we call these co-quests. Training quests are mandatory for new players to complete and are not accessible to players who chose a different avatar or with a different avatar role. An example of such can be found in the section on “Appropriation of Resources: Forest.”

Co-Quest 1: Lions for Lambs

Co-Quest 2: Join the Battle!

Co-Quest 3: Blackrock Invasion

Co-Quest 4: Ending the Invasion!

Co-Quest 1, Lions for Lambs, involved locating and killing eight enemy NPC Blackrock Spies in a forest. When Conan and Mediziner had difficulty finding them, they explored the game world outside Northshire. Both players were defeated by higher-level enemies, which forced them to revive as spirits in a cemetery and find and reanimate their avatars’ corpses. Conan and Mediziner eventually found the orcs in the forest just outside the chapel where gameplay had begun earlier and proceeded to slay them to finish the quest.

After a quest where Conan learned new combat abilities for his avatar to use in battle, Conan and Mediziner then moved to Co-Quest 2, Join the Battle!, a simple quest that required locating and speaking to an NPC. From there, Mediziner and Conan were given Co-Quest 3, Blackrock Invasion, which required exterminating more orcs. This time the quest description told them to cross a river to the east. Conan and Mediziner could see the forest was burning, so the game environment made the orcs’ location obvious. Although Co-Quest 3 did not produce any noteworthy examples of learning, we mention it as it is a prerequisite for Co-Quest 4.

The final quest of the gameplay session, Ending the Invasion!, involved finding and defeating a single enemy NPC simultaneously with other players in the game world. Other players engaged and defeated the enemy before Conan and Mediziner could, necessitating a wait for the NPC to “repop” and become available for them to claim. Unfortunately, many attempts at trying to engage this NPC resulted in failure. At this point Conan and Mediziner decided to end the gameplay session. A full list of quests and embedded CPs can be found in Appendix 2.

Appropriation of resources: forest

The first CP picks up after Conan and Mediziner accept the Lions for Lambs quest to locate and kill eight enemy NPC Blackrock Spies. This is the first co-quest they have rights to play together. The players are confused about where these enemies are.

CP 1: Misspelling

-

1.

(0:00:52.6) Mediziner: did you make any progress on that quest?

-

2.

(0:01:00.7) Conan: im still looking for spies

-

3.

(0:01:16.8) Conan: quest description said they are hiding in the forrest so

-

4.

(0:01:36.8) Mediziner: haha, the things you can find out by taking the time to read

-

5.

(0:01:47.3) Conan: yeah lol

-

6.

(0:02:14.7) Mediziner: well, lets go orc hunting

The Misspelling CP is situated within Elwynn Forest, located just outside the village of Northshire, where Conan and Mediziner began their gameplay. Conan mentions in line three that it is a natural place to be looking for the spies. This line also indicates that he has utilized one of the in-game resources, the quest log. Conan misspells the word ‘forest’ here, but Mediziner either does not notice or overlooks it. Mediziner had told Conan before they began playing that they would be simply playing the game and that Mediziner would not be actively correcting his spelling or grammar or any other errors. Furthermore, it is clear from context what Conan meant. With the forest as the primary play environment, further opportunities to use and see the word used would come later. Both players continue running around the forest a few minutes more, encountering higher-level enemies and getting killed in the process.

CP2: Wayfinding

-

1.

(0:06:01.1)/Conan dies again./

-

2.

(0:06:06.8) Conan: NNOOOOOOO

-

3.

(0:06:11.5) Mediziner: :(

-

4.

(0:06:19.4)/Mediziner opens map and reads quest description./

-

5.

(0:06:31.7) Conan: I found my corpse but that enemies were still there

-

6.

(0:06:57.6) Mediziner: oh i think i got it

-

7.

(0:07:04.3) Mediziner: we need to go to the forest to the NW

-

8.

(0:07:19.6) Conan: finally found y

-

9.

(0:07:24.5) Conan: you

-

10.

(0:07:29.0) Mediziner: k, follow me

In the Wayfinding CP, after consulting the Lions for Lambs quest description, Mediziner mentions that he thought the spies were hiding within the same forest, but in the northwestern portion. Here, Mediziner uses the correct spelling of the word. The word ‘forest’ does not come up again for some time, however, as Conan and Mediziner are lost trying to locate the enemies to be vanquished. Eventually they find the orcs and complete the quest. The next CP begins with Conan finishing a training quest and describing his task for the Join the Battle! quest.

CP3: Learning

-

1.

(0:44:13.7) Conan: k now i have to goback to trainer

-

2.

(0:44:17.9) Conan: thank you!

-

3.

(0:44:28.7) Mediziner: yw

-

4.

(0:44:50.0) Mediziner: he should give you the next quest

-

5.

(0:45:23.4) Conan: K now I have to go see Seargeant Wilem behind Northshire Abbey in Elqynn Forest

-

6.

(0:45:37.4) Mediziner: me too

-

7.

(0:45:53.2) Conan: I thought the word forrest need two rs

-

8.

(0:46:08.5) Mediziner: just one!

-

9.

(0:46:26.5) Conan: im learning! lol

-

10.

(0:46:32.1) Mediziner: awesome :D

The next mention of the word ‘forest’ appears in the CP Learning, line 5. Conan uses the dictionary spelling of the word when repeating information he had read in his quest log. Line 7 displays Conan’s realization that the word is not spelled with two Rs, and in line 9 he remarks on his learning.

Conan mentions reading the quest description, which is a rich linguistic in-game resource stating a reason and motivation for players to complete the quest. Mediziner provided the correct spelling of forest in the Wayfinding CP, but without calling Conan’s attention to it. Conan picks up on the spelling after accepting the Join the Battle! quest. He demonstrates having read the quest description and then uses the correct spelling. It is noteworthy that the action up to this point has been situated in a virtual forest. The word being learned (or relearned) is not an abstract concept, but a narrative context in which the players are situatively embodied. Through a combination of shared coaction and Conan’s perception and appropriation of the quest log and environmental resources, he comes to the correct spelling of the word on his own. This example illustrates how coaction in languaging with an expert and the game narrative affordances facilitate the realization of “forest” with one “r.” It also aligns with the cyclical nature of the eco-dialogical model where perception and action widen and broaden with attunement of the environment and dialogical partner, and learning never ceases.

Situation transcending: loot

Conan often asks for the meaning of new words he either does not know or is not sure of how they are being used in the context of WOW gameplay. He indicates this by simply asking what a word meant. The Looting CP from the Lions for Lambs quest offers one example of this.

CP4: Looting

-

1.

(0:28:30.2) Mediziner: i can’t believe they were here the whole time

-

2.

(0:29:26.0)/Conan loots enemy NPC Blackrock Spy./

-

3.

(0:29:31.5) Conan: nee

-

4.

(0:29:42.7) Conan: sorry I misunderstood the description

-

5.

(0:30:01.1) Mediziner: no worries, i didn’t really get it either

-

6.

(0:31:16.4) Conan: whats the difference between

-

7.

(0:31:19.6)/Mediziner defeats enemy NPC Blackrock Spy./

-

8.

(0:31:22.0)/Mediziner loots 1 copper./

-

9.

(0:31:26.0) Conan: verb loot and find?

-

10.

(0:31:42.9) Mediziner: good question

-

11.

(0:31:43.6) Conan: is it like to gain something? i havent seen this verb before

-

12.

(0:32:00.9) Mediziner: yeah, there’s lots of vocabulary in this game that may be new

-

13.

(0:32:12.4) Mediziner: loot is kinda like to find something valuable

-

14.

(0:32:30.4) Conan: I learned new vocabulary today :)

-

15.

(0:32:37.7) Conan: is it used only in WOW?

-

16.

(0:32:45.2) Mediziner: it’s used a lot in other games

-

17.

(0:32:58.7) Mediziner: but you can use it like

-

18.

(0:33:08.3) Mediziner: say during a riot

-

19.

(0:33:17.3) Mediziner: people break into a shop and steal all the stuff inside

-

20.

(0:33:24.5) Conan: aaaa!

-

21.

(0:33:25.1) Mediziner: we would say they’re looting

-

22.

(0:33:30.6) Conan: I see

-

23.

(0:33:41.7) Conan: so its kinda like robbing + finding

-

24.

(0:33:52.2) Mediziner: in a way

-

25.

(0:34:06.0) Mediziner: but in this game you can only loot from corpses

-

26.

(0:34:25.6) Conan: I see

In this CP, the players continue with Quest 1 by killing enemy NPCs to fulfill the objectives for Lions for Lambs. Figure 3 below illustrates the following actions. After defeating an enemy, players can check its corpse for items, action the game terms ‘looting,’ as Conan does in line 2 (in box A in Fig. 3). Whenever items are taken from a corpse, the text log indicates that players ‘loot’ something, which is indicated within box B in Fig. 3. Conan sees the same thing appear on his screen and asks in lines 6 and 9 what loot means. Mediziner explains in lines 12 and 13, with Conan confirming his understanding in line 14. In line 15 he then checks to see if this use of the word is limited to the game world. Mediziner elaborates on the meaning and links it to a real world context in lines 17 through 19. Conan appears to grasp this extension of the word’s meaning in lines 20, 22, and 23.

In this rich narrative of gameplay, a new word appears as a result of Conan’s action. As this CP shows, Conan “harvests” his loot in action, but he does not know the meaning of the word. This contrasts sharply with non-action or materially deprived environments such as classroom language learning situations where new words are usually introduced first in an abstract way so learning begins from Learning About. Even in incidental vocabulary learning situations such as picking up vocabulary in reading comprehension (e.g., Cho and Krashen 1994; Nation 2001) and conversations (Laufer and Hulstijn 2001), learners must deduce meaning from the linguistic context, but in WOW-like gameplay, experiential and multi-sensory tinkering and manipulation precede second-order formalism. Here, looting is directly enacted, mimicking child first language acquisition in a way rarely experienced by second language learners.

This example also shows how the virtual world can link resources of in-game linguistic resources, actions within the game, and text chat with other learners or teachers to help situate words in a wider social context. The expert’s role is more salient in this CP, contextualizing the meaning of the word and the action in the wider outside world and prompting further critical questioning and discussion of the situations in which looting may or may not be acceptable practice. Through gameplay, Conan learned to be a looter rather than learning about looting in a decontextualized fashion. Returning to Fig. 2, Mediziner’s contribution to Conan’s looting practice allowed both players to engage with a sociocultural “we” to transcend the immediate situation, as they both imagined a social situation in which real looting takes place.

Learning-to-be: repop

The Repop CP below displays another example of action and context before linguistic information, this time of a word that is specific terminology to WOW and other MMOGs. At the start of the CP, both players are embarking on the last quest in their play, Ending the Invasion!

CP5: Repop

-

1.

(1:09:58.5) Mediziner: okay, i think i know where the orc is we have to kill

-

2.

(1:10:05.6) Conan: K!

-

3.

(1:11:18.3) Mediziner: it says look for the passage leading into the mountains

-

4.

(1:12:27.8) Mediziner: haha, someone else killed it

-

5.

(1:12:39.7) Conan: ahaha

-

6.

(1:12:40.5) Mediziner: we’d have to wait for it to repop

-

7.

(1:12:47.0) Conan: repop?

-

8.

(1:12:54.5) Mediziner: reappear

-

9.

(1:13:07.9) Conan: naruhodoo!

-

10.

(1:13:22.8) Mediziner: pop kinda describes how they just pop out of thin air

-

11.

(1:13:26.3) Mediziner: which you just saw

-

12.

(1:13:32.2) Conan: heee!

-

13.

(1:13:57.2) Mediziner dances with the corpse of Kurtok the Slayer

-

14.

(1:14:01.0)/Kurtok the Slayer repops./

-

15.

(1:14:02.8)/Other PCs who are present engage Kurtok the Slayer./

-

16.

(1:14:08.6)/Kurtok the Slayer is killed./

-

17.

(1:14:28.1) Mediziner: did you get credit for killing it?

-

18.

(1:14:38.3) Conan: Nope

Here, Conan and Mediziner are trying to fulfill the quest’s objective of slaying a single enemy NPC. Figure 4 shows them and the other players in the game world working on the same quest, waiting for the enemy NPC to repop so they can complete the quest. The enemy does indeed repop, but neither Conan nor Mediziner is fast enough to target it and they must wait for the next repop. Mediziner points this out to Conan in line 6, which leads to an immediate questioning in line 7 by Conan. In line 8 Mediziner recasts the word with a synonym, of which Conan confirms his understanding in line 9. In this case, naruhodoo is a Japanese word that roughly translates as “I see.” Mediziner further explains the word in lines 10 and 11, and Conan again displays that he understands in line 12 by using the Japanese heee!, which in this context can be translated as “Woooow!” In Line 14, the system log displays the result of Mediziner’s action (line 13) and Kurtok the Slayer repops.

Learning the word “repop” here might not have happened at all without that very thing occurring at that moment. As an expert, Mediziner could have explained the concept of repop to Conan before undertaking the quest, but we suspect that even with a definition, repopping likely still does not make much sense to any non-MMOG players who are reading. However, in WOW there is simply no need to do so. The gameplay has progressed to the point that the players need to slay the enemy, but because of their limited skills, they must wait for the enemy to repop. As with looting, Conan experiences the context of the new word, repop, and then hears it from Mediziner. Conan asks Mediziner, who explains it by referring to what they have just seen, the NPC popping out of thin air. This CP captures the phenomenon that in WOW, learners first experience the context of words necessary to reify an event, problem, or phenomenon, then witness actions relevant and consequential to the next movement, and finally hear an expert co-player dialogically summarize the event with the target word. Both expert and novice utilize the affordance of game features—text chat, system logs, and repop function—to make this learning event significant. In contrast, word-learning sequences usually occur reversely, when a teacher introduces a new word first and provides a context to explain the word meaning. Action opportunities in classrooms are rarely bound tightly with learners’ next action possibilities. We argue that the WOW sequence of vocabulary learning reflects the participatory, collaborative, and distributed nature of learning. Returning to Brown’s (2005) concept of learning about and learning to be, this CP shows how the WOW environment provided Conan learning that he could simultaneously see and do.

Conclusion

We conclude this study by orienting to the two research questions. To answer the first, how language learners appropriate resources in co-play, we witnessed Conan pick up vocabulary utilizing the resources of WOW and actively “taking advantage” of his co-player to better understand meaning and form than would have been possible in a textbook or classroom. While two of the examples in our analysis show Conan learning words that are more specific to the game environment, this study is not solely about vocabulary learning in MMOGs. More importantly, MMOGs allow transcending the immediate situation of gameplay, facilitating learners’ learning to be through languaging in myriad contexts.

Seen in this light, instead of learning about language in terms of second-order constructs, Conan was engaged in learning to be in first-order languaging (Linell 2009). Beyond recounting an ecological and dialogical analysis of vocabulary learning occurring in coordination with co-players afforded by WOW game interfaces, such as quest goals, chat boxes, and NPC generated responses, all three examples demonstrate Conan as an agentic language learner. He languaged his cognitive process, sharing with Mediziner his realization that forest has one “r” and initiating questions about the meaning of “loot” and “repop.” Although classrooms expect teachers to foster agency in learners, WOW naturally encourages learner agency. While playing WOW, language and meaning surrounded Conan, who made use of its affordances and resources (including Mediziner) to recognize and learn new vocabulary.

Answering research question two, what vocabulary learning looks like within an eco-dialogical framework, vocabulary learning became salient as we analyzed both chat and avatar action data through iterative multimodal analysis and provided a thick description and dynamic process of co-play. Both players engaged in cycles of perception and action, identifying available affordances and using them to achieve skilled linguistic action and learning. However, recognizing and employing such affordances may depend on the language learner’s experience. If Conan were to rely upon classroom knowledge of English or a dictionary for unknown words, he might stumble in an unpracticed or unexpected situation. In his WOW play, which required attuning to environmental affordances in service of completing quests, Conan effectively problem-solved and made skilled linguistic actions (Newgarden et al. 2015; Zheng et al. 2012). These skills can be applied from the game to the real world.

Implications

Video games already show great promise in allowing learners to transcend the situation of “here and now.” Kerbal Space Program, a rocket-building game, has been utilized by introductory engineering design teachers to teach concepts better than might be possible in a textbook or traditional classroom setting (Ranalli et al. 2013). Civilization, a historical simulation game, gives students a chance to experiment with geography, resource distribution, and technological development, rather than viewing history through the lens of so-called “great people” (Squire 2008). In language learning, deliberately designed experiences in virtual worlds with more directed gameplay with groups of language learners have enabled wider possibilities of languaging for students (Zheng and Newgarden 2012).

Both language educators and language learners must recognize that learning in this digital era requires shifting from content mastery to critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration, participation, and distribution in digital environments (Black 2006; Gee 2006). CALL must broaden its scope from “assisting” learning to embodying coordination and cooperation (Thorne 2008; Zheng and Newgarden 2012). In this study, by connecting embodied cognitive sciences and other game and virtual world research by scholars who stress the socio-material embodiment (Gee 2003), invariant and variant features (Velleman 2008), projective stance with avatars and the situating context (Dourish 2001; Gee 2008), and coaction affordances for player-avatar and avatar player–player coactions (Zheng and Newgarden 2012), we harness eco-dialogical embodiment that considers affordances of narratively and perceptually rich environments and social gameplay as coordination of action in languaging. Importantly, this study demonstrates the power of MMOG environment in which context and action are experienced before abstract words that can contribute to a diverse pedagogical toolbox.

Notes

The Distributed Language Group (n.d.) rejects all forms of cognitive centralism, including both theories of disembodied cognitivism and cognitive embodiment, and posits instead that language is “spread across bodies in time and space”.

Our work differs from physical sensory embodiment enabled by technology, such as work done by the Virtual Human Interaction Lab (http://vhil.stanford.edu/projects/), which centers on simulating self into virtual reality and seems to rely on within-avatar-player embodiment, in contrast with eco-dialogical embodiment and co-actional embodiment (Zheng and Newgarden 2012).

Because they used a free trial version of the game, the participants had to communicate entirely through private messages and could not work with other players in the game.

References

Activision Blizzard, Inc. (2014). Activision Blizzard announces fourth quarter and CY 2013 financial results. http://investor.activision.com/results.cfm. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

Baldry, A., & Thibault, P. J. (2006). Multimodal transcription and text analysis: A multimedia toolkit and coursebook. London: Equinox.

Barab, S., Zuiker, S., Warren, S., Hickey, D., Ingram-Goble, A., Kwon, E.-J., & Herring, S. C. (2007). Situationally embodied curriculum: Relating formalisms and contexts. Science Education, 91(5), 750–782. doi:10.1002/sce.20217.

Black, R. (2006). Digital design: English language learners and reader reviews in online fiction. In M. Knobel & C. Lankshear (Eds.), A new literacies sampler (pp. 115–136). New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Brown, J. S. (2005). New learning environments for the 21st century. http://www.johnseelybrown.com/newlearning.pdf. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

Cho, K., & Krashen, S. (1994). Acquisition of vocabulary from the Sweet Valley Kids series: Adult ESL acquisition. Journal of Reading, 37(8), 662–667.

Cowley, S. J. (2012). Cognitive dynamics: language as values realizing activity. In A. Kravchenko (Ed.), Cognitive dynamics in linguistic interactions (pp. 15–46). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press.

Cowley, S. J. (2013). Naturalizing language: human appraisal and technology. Artificial Intelligence & Society, 28, 443–453.

deHaan, J. (2005). Acquisition of Japanese as a foreign language through a baseball video game. Foreign Language Annals, 38(2), 278–282.

deHaan, J., Reed, W. M., & Kuwada, K. (2010). The effective of interactivity with a music video game on second language vocabulary recall. Language Learning & Technology, 14(2), 74–94.

Distributed Language Group. (n.d.). Retrieved February 18, 2015, from http://www.psy.herts.ac.uk/dlg/.

Dourish, P. (2001). Where the action is. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dufva, H. (2013). Language learning as dialogue and participation. In E. Christiansen, L. Kuure, A. Morch, & B. Lindstrom (Eds.), Problem-based learning for the 21st century: New practices and learning environments (pp. 51–72). Aalborg, Denmark: Aalborg University Press.

Farr, W., Price, S., & Jewitt, C. (2012). An introduction to embodiment and digital technology research: Interdisciplinary themes and perspectives. Retrieved from http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2257/.

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gee, J. (2006). Pleasure, learning, video games, and life: The projective stance. In M. Knobel & C. Lankshear (Eds.), A new literacies sampler (pp. 95–114). New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Gee, J. P. (2008). Video games and embodiment. Games and Culture, 3(3–4), 253–263.

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Hodges, B. H. (2009). Ecological pragmatics: values, dialogical arrays, complexity and caring. Pragmatics & Cognition, 17(3), 628–652.

Hutchins, E. (1995). Cognition in the wild. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Järvilehto, T. (2009). The theory of the organism-environment system as a basis of experimental work in psychology. Ecological Pyschology, 21(2), 112–120.

Laufer, B., & Hulstijn, J. (2001). Incidental vocabulary acquisition in a second language: Same or different? Applied Linguistics, 19(2), 255–271.

Levinson, S. C. (1995). Interactional biases in human thinking. In E. N. Goody (Ed.), Social intelligence and interaction (pp. 221–260). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Linell, P. (2009). Retinking language, mind, and world dialogically: Interactional and contextual theories of human sense-making. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing Inc.

Magnani, L. (2004). Model-based and manipulative abduction in science. Foundations of Science, 9, 257–259.

Nation, P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Newgarden, K., Zheng, D., & Liu, M. (2015). An eco-dialogical study of second language learners’ World of Warcraft (WoW) gameplay. Language Sciences, 48, 22–41.

Peirce, C. S. (1982). Writings of Charles S. Peirce: A chronological edition (Vol. 1, pp. 1857–1866). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Peterson, M. (2010). Digital gaming and second language development: Japanese learner interactions in a MMORPG. Digital Culture & Education, 3(1), 56–73.

Piirainen-Marsh, A., & Tainio, L. (2009). Collaborative game-play as a site for participation and situated learning of a second language. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 53(2), 167–183.

Rama, P. S., Black, R. W., Van Es, E., & Warschauer, M. (2012). Affordances for second language learning in World of Warcraft. ReCALL, 24(3), 322–338.

Ranalli, J. (2008). Learning English with The Sims: Exploiting authentic computer simulation games for L2 learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 21(5), 441–455.

Ranalli, J. & Ritzko, J. (2013). Assessing the impact of video game based design projects in a first year engineering design course. 2013 Frontiers in Education Conference Proceedings (pp. 530–534). Piscataway, NJ: IEEE.

Rankin, Y., Gold, R., & Gooch, B. (2006). 3D role-playing games as language learning tools. In E. Groller & L. Szirmay-Kalos (Eds.), Proceedings of EuroGraphics 25(3), New York: ACM.

Rankin, Y., Morrison, D., McNeal, M., Gooch, B., & Shute, M.W. (2009). Time will tell: In-game social interactions that facilitate second language acquisition. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Foundations of Digital Games (pp. 161–168). New York: ACM.

Squire, K. (2008). Open-ended video games: A model for developing learning for the interactive age. In K. Salen (Ed.), The ecology of games: Connecting youth, games, and learning (pp. 167–198). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Steffensen, S. V. (2013). Human interactivity: Problem-solving, solution-probing and verbal patterns in the wild. In S. J. Cowley & F. Vallée-Tourangeau (Eds.), Cognition beyond the brain: Computation, interactivity and human artifice (pp. 195–221). Dordrecht: Springer.

Suh, S., Kim, S. W., & Kim, N. J. (2010). Effectiveness of MMORPG-based instruction in elementary English education in Korea. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 26, 370–378.

Sykes, J. M., Oskoz, A., & Thorne, S. L. (2008). Web 2.0, synthetic immersive environments, and mobile resources for language education. CALICO Journal, 25(3), 528–546.

Sylven, L., & Sundqvist, P. (2012). Gaming as extramural English L2 learning and L2 proficiency among young learners. ReCALL, 24(3), 302–321.

Thibault, P. J. (2011). First-order languaging dynamics and second-order language: The distributed language view. Ecological Psychology, 23(3), 1–36.

Thorne, S. L. (2008). Transcultural communication in open Internet environments and massively multiplayer online games. In S. S. Magnan (Ed.), Mediating discourse online (pp. 305–327). Philadelphia: John Benjamins North America.

Van Lier, L. (2004). The ecology and semiotics of language learning: A sociocultural perspective. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Velleman, J. D. (2008). Bodies, selves. American Imago, 65, 405–426.

Zheng, D. (2012). Caring in the dynamics of design and languaging: Exploring second language learning in 3D virtual spaces. Language Sciences, 34, 543–558.

Zheng, D., & Newgarden, K. (2012). Rethinking language learning: Virtual World as a catalyst for change. International Journal of Learning and Media, 3(2), 13–36.

Zheng, D., Newgarden, K., & Young, M. F. (2012). Multimodal analysis of language learning in World of Warcraft Play: Languaging as values-realizing. ReCALL, 24(3), 339–360.

Zheng, D., Young, M. F., Brewer, B., & Wagner, M. (2013). Attitude and self-efficacy change: English language learning in virtual worlds. CALICO Journal, 27(1), 205–231.

Zheng, D., Young, M. F., Wagner, M., & Brewer, B. (2009). Negotiation for action: English language learning in game-based virtual worlds. The Modern Language Journal, 93(4), 489–511.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. We received informed consent from the participant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Transcript text was either copied directly from WOW’s chat and system logs or inserted by Author 2 during the transcription process to indicate action recorded in screen capture video. Original typos remain untouched. The following transcription conventions were used:

-

Non-italicized text: Private chat dialog between Conan and Mediziner

-

Italicized text: Emote text that appears in the chat log.

-

/Italicized text in slash marks/: Description of action not initially recorded by the game in either chat or system logs

-

Text in boldface: Points of emphasis by the author

Appendix 2

Table of quests and communicative projects

The gameplay recording was split into two videos due to a recording interruption during gameplay. Runtime for Video 1 is 0:24:56. Runtime for Video 2 is 1:31:56. Quest names were provided by the game. We identified and named communicative projects throughout the recordings. CPs chosen for analysis are given in bold text. Note that multiple quests may be active at any given time. Players are free to complete them at their leisure, so they might work toward one quest’s objectives, and in the process of doing so accept another quest that potentially distracts them from what they were originally working on. CPs are therefore ongoing and at times occur within multiple quests simultaneously.

Time duration | Quest name | Communicative projects |

|---|---|---|

Video 1: 0:10:26–0:16:04 | Beating Them Back! | Slaying 1 Looting 1 Learning to Play 1 Equipping 1 |

Video 1: 0:16:13–0:25:56 Video 2: 0:00:00–0:32:19 | Lions for Lambs | Misspelling 1 (CP1) Wayfinding 1 (CP2) Looting 2 (CP4) Equipping 2 Dueling 1 Dying 1 Chatting 1 Slaying 2 |

Video 2: 0:11:52–0:13:46 | Rest and Relaxation | Wayfinding 1 (CP2) Learning to Play 2 |

Video 2: 0:32:27–0:35:49 | Hallowed Letter | Looting 2 (CP4) |

Video 2: 0:35:58–0:38:20 | Healing the Wounded | Training 1 |

Video 2: 0:38:28–0:46:18 | Join the Battle | Learning (CP3) Training 1 Wayfinding 2 |

Video 2: 0:46:23–0:52:13 | They Sent Assassins | Slaying 3 Thanking 1 |

Video 2: 0:46:54–0:52:07 | Fear No Evil | Slaying 3 Thanking 1 |

Video 2: 0:52:18–0:53:01 | The Rear is Clear | |

Video 2: 0:53:03–1:01:42 | Blackrock Invasion | Collecting 1 Chatting 2 Translanguaging 1 |

Video 2: 1:01:59–Incomplete | Ending the Invasion! | Repop 1 (CP5) Learning to Play 3 Asking for Definitions 1 |

Video 2: 1:02:14–1:19:20 | Extinguishing Hope | Repop 1 (CP5) Learning to Play 3 Asking for Definitions 1 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, D., Bischoff, M. & Gilliland, B. Vocabulary learning in massively multiplayer online games: context and action before words. Education Tech Research Dev 63, 771–790 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-015-9387-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-015-9387-4