Abstract

Long association with a mathematics teacher at a Grade 4–6 school in Sweden, is basis for reporting a case of teacher–researcher collaboration. Three theoretical frameworks used to study its development over time are relational knowing, relational agency and cogenerative dialogue. While relational knowing uses narrative perspectives to explore the experiential and relational nature of collaboration; relational agency, draws on activity theory perspectives and identifies the change in the purpose of collaboration, from initially conducting classroom interventions to co-authoring research. Finally, cogenerative dialogue, deploys hermeneutic-phenomenological perspectives and investigates the dialogue that transpired between Lotta and the author, as they co-authored their research report. Such analysis sheds invaluable light on a case of expansive learning activity.

Svensk sammanfattning

Denna artikel undersöker ett långvarigt samarbete mellan Lotta, en matematiklärare på en mellanstadieskola, och författaren, en universitetsbaserad forskare. Samarbetet inleds med att författaren observerar Lottas undervisning och kulminerar i deras samförfattande av en forskningsrapport som beskriver en intervention de tillsammans genomfört. I detta samarbete är både Lotta och författaren forskare, där Lottas professionella kontext är platsen för forskningen och Lottas undervisningspraktik är i fokus för undersökningen. Tre teoretiska ramverk används för att analysera och förstå detta samarbete. För det första, relationellt vetande (relational knowing, Hollingsworth, Dybdahl, & Minarik 1993), som bygger på narrativa perspektiv och utforskar den erfarna och relationella karaktären hos ett samarbete. För det andra, relationell medverkan (relational agency, Edwards 2005), som bygger på perspektiv från aktivitetsteori och identifierar förändringen av samarbetets syfte från att initialt genomföra klassrumsinterventioner till att samförfatta forskning. För det tredje, medgenererande dialog (cogenerative dialogue, Roth and Tobin 2002), som bygger på hermeneutiska-fenomenologiska perspektiv och undersöker den dialog som försiggick mellan Lotta och författaren då de samförfattade forskningsrapporten. Förutom att ge empiriska belägg för samarbete mellan lärare och forskare, sprider en sådan insats ovärderligt ljus över hur författarens samarbete med Lotta blev ett fall av expansiv inlärning (expansive learning, Engeström 2001).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In an early paper relating to development of theory and practice in action research, John Elliott (1978) makes a useful distinction between research on education and educational research. As different from developing formal theory with definitive concepts in the former, the latter develops substantive theory of action with sensitising concepts. Reflecting similarly on the difference between teacher effectiveness research and research based teaching, in more recent writing Elliott (2009) draws on Martha Nussbaum and clarifies the former to look for general rules and the latter for universal rules. Unlike general rules born of abstraction from particularities of circumstance and time, universal rules applicable to particular cases are relevant in similar ways and represent the voice of concrete practical experience. In line with Elliott (1978) I develop three sensitizing concepts to unpack a single case of teacher–researcher collaboration in this paper, and in line with Elliott (2009) I characterise this collaboration as a universal case of expansive learning activity (Engeström 2001). In such pursuit I draw on my collaboration with Charlotta Blomqvist, a mathematics teacher at a Grade 4–6 school in Sweden. I was introduced to Lotta, as Charlotta is known, in January 2009 after which I visited her classroom regularly until the summer break of 2010. Beginning with my observing her classroom teaching, we have since been able to conduct whole classroom intervention and also begun to co-author research reports pertaining to these. It is the historical trajectory of our collaboration that is the unit of analysis and focus of this paper. It is also for such analysis that I draw on cultural historical activity theory and/or CHAT perspectives whose premise, as articulated by one of its founders Leont’ev, reads,

Consciousness is co-knowing… Consciousness is originated by society; it is produced. For this reason consciousness is not a postulate and not a condition of psychology but its problem, a subject for concrete scientific psychological investigation. (1978, p. 60)

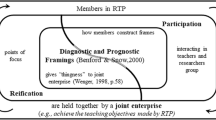

In investigating collaboration or co-knowing with Lotta, I am guided by Kurt Lewin’s expression, that there is nothing more practical that a good theory. Yet in line with practical-theoretic emphasis of CHAT I find Anna Stetsenko’s (2004) reformulation of Lewin just as valid, that there is nothing more theoretically rich than good practice. I consider my collaboration with Lotta as good practice, in terms of our continued ability to take instructional action as well as build theory simultaneously. While Lotta summarised our collaboration in terms of doing a professional development course in an interview, I reflect on our collaboration in five sections that follow. First, I outline the history of our collaboration before deploying three analytical constructs. Drawing on narrative perspectives in the first of these, I explore the experiential and relational nature of collaboration through relational knowing (Hollingsworth, Dybdahl and Minarik 1993). I next draw on activity theory perspectives to analyse the change in the purpose of our collaboration, from initially conducting classroom interventions to later co-authoring research, with relational agency (Edwards 2005). In the third, I draw upon hermeneutic perspectives to investigate the dialogue that transpired between both of us during co-authorship, with cogenerative dialogue (Roth and Tobin 2002). In conclusion I portray teacher–researcher collaboration as a case of expansive learning activity (Engeström 2001). I thus ask, how do relational knowing, relational agency and cogenerative dialogue shed light on teacher–researcher collaboration, as well as expansive learning activity.

In analysing my collaboration with Lotta I draw on arguments in practitioner inquiry, a genre of research in which practitioners are researchers, professional contexts are research sites and practices themselves are foci of investigation (Cochran-Smith and Donnell 2006). Understandably, such inquiry could focus upon and shed light on underexplored aspects which risk being overlooked by research on education (Elliott 1978). As example there is opportunity to blur boundaries between teachers and researchers, knowers and doers as well as experts and novices (Cochran-Smith and Lytle 1999), for deepening the dialectic between relevant research and wise practice (Cochran-Smith 2005), for developing tools that enable practitioners to build cumulatively on each other’s work (Cochran-Smith and Zeichner 2005), for K-12 teachers to themselves theorise K-12 teacher research (Cochran-Smith and Donnell 2006) and finally for teachers to examine their teaching in relation to their students’ learning (Cochran-Smith and Fries 2008). In pursuing some of these opportunities in my writing, I perceive the experiences that Lotta and I encountered as a patchwork of insights gained from the theoretical lenses I deploy (Winter, Buck and Sobiechowska 1999) and explore the professional development our collaboration was able to foster in each of us as practitioners (Wardekker 2010). Such a study is recognised as important not only for its ability to pose questions that could capture nuances of the particular (Craig and Ross 2008) but also correct an imbalance in research literature which tends to lay emphasis on research technique, at the expense of human correspondence in collaborative research (Day 1997).

My own approach to investigating teacher–researcher collaboration is two fold. In the first, I draw on CHAT perspectives in a theory/practice and close-to-practice manner,

Close-to-practice research, which keeps its roots in robust theoretical frames can throw light on immediate pedagogical affordances, can highlight tensions and contradictions at the system level and can become integrated as informed problem-solving into professional practice. Additionally it can itself be open to questions from practice that can help disrupt the assumptions that support theory… (Edwards, Gilroy and Hartley 2002, p. 123)

Adopting such a stance allows me to conceive Lotta as theoriser as well as produce knowledge by utilising scientific concepts with which to interpret classroom instruction (Vygotsky 1978). This has allowed me to be agentive and keep alive the relation between theory-which-informs and theory-being-built, as well as existing-practice and steered-practice (Gade 2012b). For example, Lotta and I drew on self-directed mediated activity and conducted action research in relation to the faulty use by her students of the mathematical = sign (Gade 2012a). Another CHAT based study is that of Viv Ellis (2011) who used historically produced knowledge in his interventions with participating teachers, to stimulate their professional creativity. In the second, I draw on narrative perspectives to obtain a storied and temporal understanding of our longitudinal collaboration,

Narrative inquiries produce a storied description of a practice process carried out in a concrete life space. Unlike theoretically driven research, they do not produce a list of techniques or procedures that are promised to work in every setting. They offer their readers a vicarious experience of how a practice was conducted in a concrete situation. From this the readers’ experiential background is enlarged, their repertoire of possible actions is increased, and the judgments about what might be done in their own practice in similar situations is sharpened. (Polkinghorne 2010, p. 396)

Polkinghorne’s reference to theoretical driven research in the above quote is in line with generalised laws that Elliott (2009) refers to, one which treats knowledge in a synchronic manner. Yet, my own attempts are diachronic and treat research as a practice and a product of actions that I took over time (Polkinghorne 1997). As example, I examined students’ narratives as they negotiated the mathematics expected of them within Lotta’s instruction (Gade 2010). I thus argued narrative as unit of analysis ably suited to grasping teaching–learning praxis and practitioner action (Gade 2011). Another study adopting a narrative and action research approach is that by Tracey Smith (2008) who, by laying emphasis on praxis in pre-service teacher education, provided teacher students an opportunity to reflect on the relationship between theory and practice. It is with combined CHAT and narrative perspectives that I thus understand my collaboration with Lotta, whose history I turn to.

Historical outline of collaboration

My association with Lotta, which began in January 2009, coincided with my exploring perspectives of narrative inquiry as researcher, adding these to my CHAT-based repertoire. While Lotta taught at grade six, I attempted to understand students’ narratives as they learnt mathematics in various pedagogical modes (Gade 2010). Over summer and in anticipation of collaboration with students at grade four in the following year, Lotta took the initiative of applying for project funding handed out by Swedish school authorities (Skolverket Dnr 2009:406; http://www.skolverket.se). Focused on communication for mathematics, it was Lotta’s project aims which reoriented our collaboration. In line with CHAT perspectives we drew on Neil Mercer’s (2004) writings, which argue classroom talk to be a social mode of thinking, and conducted many talk-based interventions including the game of Yes and No to have students deliberate place value, a plenary of exploratory talk in relation to the topic of measurement (Gade and Blomqvist, submitted), and a problem posing classroom practice (Gade and Blomqvist 2014). In sections that follow I first draw on my study with Lotta’s Grade six students and finally dwell on Lotta’s plenary with her grade four students.

Two aspects in the above outlined trajectory are worthy of mention as we search for tools with which to enable practitioners to build cumulatively on each other’s work (Cochran-Smith and Zeichner 2005). The first of these is practitioner reflexivity which is explicit identification by Lotta and myself of our interaction with her students, each other, our data and our theoretical interpretations (Etherington 2006), an aspect I greater detail in our conduct of action research (Gade 2012a). The second is outing of a researcher with respect to his or her own research, explicating one’s theoretical perspectives and intersubjectivity inevitable for integrity and trustworthiness in qualitative research (Finlay 2002), an aspect I trace in relation to my use of narrative as unit of analysis (Gade 2010). Our very conduct of classroom interventions also has backing in contemporary debate, of which I cite three examples. First, a plenary at an annual international conference in mathematics education research which urged teachers and researchers to become stakeholders in each other’s practices, so as to formulate situated hypothesis that other practitioners could examine (Krainer 2011). Second, a summary in a handbook of mathematics education research which identified any understanding of how mathematics teaching–learning takes place as its most formidable task (Niss 2007). Finally, guidelines issued by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics so as to facilitate the linking of research and practice (Arbaugh, Herbel-Eisenmann, Ramirez, Knuth, Kranendonk and Quander 2010). My CHAT and narrative inspired response to such calls is to examine mutual co-knowing with Lotta (Leont’ev 1978), deepen the dialectic between research and practice (Cochran-Smith 2005), and support her contribution to research as a teacher (Cochran-Smith and Donnell 2006). In doing so I examine a collaborative environment which vitally promoted practitioner ontology and agency in our collaborative development of practitioner knowledge (Kincheloe 2003). I now turn to examine relational aspects of such a symbiosis.

Relational knowing: narrating shared practice

Two writings guide deployment of relational knowing, my first theoretical construct. The first argues for suitability of narrative inquiry in studying school practice and the second its suitability for studying teaching within school practice. Sigrun Gudmundsdottir (2001) argues school practices to mediate cultural and social meanings of any society through narratives, in which they are both ubiquitous and embedded. Articulated in what she terms language of practice, these narratives allude say to norms like addressing a teacher by first name or being treated on equal terms with the other gender. World making, these narratives constitute the unique experiences students have of schooling. Gudmundsdottir argues narratives to thus access situated experience, enabling research to unpack societal issues of significance that they in turn connote. Portraying teachers as knowledgable people in culturally saturated schools, Jean Clandinin and Michael Connelly (1998) emphasise a narrative understanding of teaching in terms of personal practical knowledge. They show such a construct to grasp not only past, present and future scenarios, but also the personal, professional and practical nature of teachers’ experiences. Clandinin and Connelly thus visualise educational reform in epistemological terms, accessible in terms of school stories that practitioners live by. It is to such relational aspects in narrative inquiry that I turn.

Relational knowing focuses on teachers and practitioners relating to themselves, one another and their students as a primary manner of knowing. Drawing on Sandra Hollingsworth’s (1992) struggle to conceive teaching in terms of feminist praxis, one discerns here an ethic of valuing experience and being changed in that very process, as a source of knowledge. Standing up against normative expectations that could devalue such contributions, Hollingsworth argues for the need to remain in sustained relationships to bring about epistemological change, which, besides being practice based, draws upon personal biographies. Relational knowing thus lies at the intersection of three domains—the social construction of knowledge, one’s knowing through relationships with oneself as well as other’s, and the feminist perspective of existential awareness (Hollingsworth, Dybdahl and Minarik 1993). Their citing educational philosopher Maxine Greene on the serious problem with alienated teachers is worth quoting again,

Alienated teachers, out of touch with their own existential reality, may contribute to the distancing and even to the manipulating that presumably takes place in many schools. This is because, estranged from themselves as they are, they may well treat whatever they imagine to be selfhood as a kind of commodity, a possession they carry within, impervious to organizational demand and impervious to control. Such people are not personally present to others or in the situations of their lives. They can, even without intending it, treat others as objects or things. (Greene 1979, p. 29, As in Hollingsworth et al. 1993, p. 10)

Pointing to the importance of building relationships between educators and students, educational reform is here conceived in terms of relational knowing, rather than on basis of teacher competence in disciplinary knowledge and best practices of curricular standards alone (Gallego et al. 2001). Relational knowing is finally recognised as surfacing in open conversations, wherein practitioners spend time to deepen, enrich and understand each other’s ideas and not just conclude business (Hollingsworth and Dybdahl 2007). In school narratives being situated in the present and tradition simultaneously, such knowing is finally recognised as coming to fruition in long term sustained relationships with explicit attention to issues of identity and power.

Relational knowing between Lotta and me commenced in January 2009, when we were introduced by a colleague at my department, after which I asked to observe Lotta’s teaching her grade six. With Lotta’s consent, I was able to observe her when she used the whiteboard say or an accentuated voice to call her students’ attention. I also got to know her as a person by exchanging notes about our lives or observe her share a dress code with Cecilia, the class teacher, every Friday. Our banter endures to this day and includes her having ruined her son’s phone by having washed his shorts in the washing machine, my learning Swedish, or our noticing the castle her students built on the mound of cleared snow during dark winter days. Our relationship with Lotta’s students was also close at hand as we shared aspects like who had a strict father or a demanding mother, even as we took extra care of a pair of twins who had just lost their mother. As argued by Nel Noddings (2012) in such manner of relational caring we were ethically relating to life itself. My being observant of classroom life along with my propensity to engage students with a mathematical problem or two led Lotta to direct students to me over time. These students had accomplished what Lotta had asked of them, or needed individual attention which she was herself unable to provide. It was such manner of growing into Lotta’s teaching that facilitated my conduct of narrative inquiry. Illustrative of gaining relationships between educators and students (Gallego et al. 2001) I now offer an extract from this study. In recognition of early days in our association where, in keeping with researcher ethics, I also anonymise Lotta as Lea and her class teacher Cecelia as Sofia. Lotta’s students however remain anonymised at all times. I relate my engagement with Alex,

… Lea asked if I could work individually with Alex, who she said would ask her once again something she had mentioned to him a moment or two ago. During her meetings with Lea and Sofia, Alex’s mother would agree that Alex needed to work additionally at his mathematics. Looking to explain his performance she would surmise “He is a humanist, like his father.” Lea wrote to her saying I would work with him. “I will also encourage him at home,” she replied. Alex had a sensitive command over English making it easy for me to work with him. He struggled with reducing fractions to their lowest terms…. (Gade 2010, p. 105)

My narrative of working with another student Felix reads

When asked if he enjoyed his problem solving session, Felix chose his words in English and said “This was special!” My interaction with Felix was mainly when he attempted a numerical crossword in one of Lea’s worksheets. He worked through the clues to arrive at numbers that were to fill the crossword. Occasionally he turned to me to solve say 2 × 47 × 5. On blanking out 47 with my finger and asking him what 2 × 5 was, he saw the point of not multiplying 2 and 47 first. He turned to me again when the clue asked 124 + 89 – 123 where my finger on the number 89 was followed by his saying “90”…. (Gade 2010, p. 106)

My two narratives of Alex and Felix shed light on how inextricably linked their learning as students was, with relationships they had developed. In Felix’s case this involved my showing him how to simplify clues to his numerical crossword. I remember sitting quietly beside Felix, implicitly offering help if he were to ask. Assisting him to locate his error when he made a mistake led to his completing the puzzle with great satisfaction, an aspect I would have robbed him of had our relationship been otherwise. Unlike Felix, my relationship with Alex was based on relationships that Lotta and his mother also had. It was on Lotta’s initiative that Alex’s mother encouraged him to work with me. I guided Alex to observe patterns in tables of multiplication which he found difficult to master. This lead him to recognise numerator and denominator of fractions that were multiples of a common factor. Alex and Felix’s coming to know lay in relationships we nurtured.

However crucial, my ability to work with Alex and Felix was only part of the alliance of trust I developed with Lotta, for our becoming stakeholders in each other’s practice involved my shouldering Lotta’s responsibilities (Krainer 2011). This included helping Cecilia organise the annual Kängaru competition (http://ncm.gu.se/kangaru) when Lotta had a meeting to attend. Lotta too was keen to read research literature, which we drew upon to conduct talk-based interventions. Such history took a crucial turn when I received the following email from her,

We worked today at multiplication of numbers that combined addition and subtraction. For example 5 x 7 + 3 + 9 =. I discovered that many students have not understood the meaning of the = sign. We discussed a lot that the two sides of the equality sign must be equal. (Gade 2012a, p. 553)

The above email turned my thus far respectful collaboration with Lotta into action research. I narrate the steps I took soon after I received the above mail,

I surmised Lea’s email to be a significant step in that Lea was now sharing her problem, beyond merely welcoming my research. While we found ways to resolve this problem, along with Lea’s expectation that I would do so, her mail also symbolised the kind of expectations that educational practice could have of educational research. Curious to find out how it was that Lea came upon the problem, I arranged to meet Lea before my weekly visit. With a body language that many primary teachers effectively use, Lea recreated for me the events that prompted her email. Lea narrated how she had asked one of her students, Jan, to attempt a particular question on the whiteboard. While I detail Jan’s usage of the equality sign in the next section, Lea’s narrative expressed dismay in finding that none of her other students objected to Jan’s faulty usage. Lea’s act of sharing the problem with me was symbolic in one other respect – of her exhibiting a distinct sense of reflexivity. Not only was Lea reacting critically to events that transpired, it was Lea who was initiating action and seeking solutions. (Gade 2012a, p. 557).

The above exchange describes our taking action to be an instance of feminist praxis, in that Lotta and I valued our experiences (Hollingsworth 1992). Lotta did not devalue her coming upon Jan’s faulty use of the = sign and her dismay spoke of personal experience which she did not relegate to the background. Three aspects constituted our relational knowing (Gallego et al. 2001)—our shared experience with the curriculum, the relationships with each other and her students, and the semiotic practice we set up to rectify the problem. In taking these actions we not only drew on theoretical constructs of self-directed activity (Bodrova and Leong 2007) and explicit mediation (Wertsch 2007) but also dealt with practice and theory on even terms (Blomqvist and Gade 2013). It goes without saying that in obtaining knowledge which was actionable, our history of collaboration was cornerstone. Our heightened awareness of experiences followed by actions was relational, socially constructed and nurtured through our relationships (Hollingsworth et al. 1993). On one hand we shared thoughts as two individuals, on the other we drew on praxis and took action as practitioners. I now turn to examine relational agency in our collaboration.

Relational agency: altering the object of activity

Lotta’s obtaining of project funding brought along a set of experiences and expectations that went beyond classroom teaching. For one she had to report to Skolverket, her funding agencies, on the progress she made in her project. Interestingly, the expertise she herself gained in this process was also utilised by them in helping them evaluate project proposals of other teachers in the next cycle of funding. After this Lotta worked with Skoleverket for a year giving our collaboration a break, even as I continued to work with Cecilia at Grades 5 and 6. During this period while Lotta observed firsthand the efforts that Skolverket made with respect to improving instruction of mathematics at schools across Sweden, I too reported our conduct of action research (Gade 2012a). For a brief eight week period Cecilia signed up for a professional development course at my university, allowing me opportunity to collaborate with her substitute teacher. With empowering of practitioners playing out in my role as a researcher, Lotta’s return from Skolverket was fertile ground for further change when my suggestion of co-authoring research reporting renewed our collaboration once more. Our co-knowing, in circumstances quite different from the one we first entered into, is now the focus of my investigation (Leont’ev 1978). While I defer analysis of our conversation that transpired during co-authorship to the next section, I dwell presently on the purpose of our newer collaboration or the object of our activity. I draw upon Leont’ev once again,

The main thing which distinguishes one activity from another, however, is the difference of their objects. It is exactly the object of an activity that gives it a determined direction. According to the terminology I have proposed, the object of the activity is its true motive. It is understood that the motive may be either material or ideal, either present in perception or existing only in the imagination or in thought. The main thing is that behind activity there should always be a need, that it should always answer one need or another. (1978, p. 62)

Leont’ev allows me to nuance my growing collaboration with Lotta, as amounting to participating in two different activities with two different objects. Where the object of the former was to intervene in Lotta’s classroom instruction, that of the latter was to build theory and co-author research. In line with Leont’ev these objects motivated our collaboration differently and satisfied needs which we perceived as practitioners. It is such change in the object of our continued activities over time that Yrjö Engeström (2001) characterises as expansive learning activity. The need for such expansion, Engeström (2008) would argue, arose from mid level systemic contradictions we faced in teaching which lay inbetween rules, regulations and budgets on one hand and curricula, textbooks and study materials on the other. The contradictions we faced were characterised by wider concerns of falling standards in mathematics by Swedish students as shown by international tests, and our wanting to advance communication for mathematics so as to meet Lotta’s project goals. In such pursuit both Lotta and I had to be resourceful and draw on expertise that either of us had. This meant we aligned and realigned our thoughts and actions to meet with issues we now faced as practitioners, whose pursuit Anne Edwards (2005) terms as relational agency,

In working towards an understanding of purposeful practice with others I want to introduce the concept of relational agency i.e., a capacity to align one’s thought and actions with those of others in order to interpret problems of practice and to respond to those interpretations. (pp. 169 – 170)

By focusing on relational agency Edwards (2009) allows us to shift attention from systemic issues that practitioners encounter, to actions that practitioners can take in consultation with each other. In my collaboration with Lotta, this of course began with our becoming stakeholders in each other’s practice (Krainer 2011) and our able to conceive her classroom in close-to-practice terms (Edwards et al. 2002). For example, in action research conducted in relation to the = sign we spoke in terms of self-directed activity (Bodrova and Leong 2007) and explicit mediation (Wertsch 2007). Similarly, in Lotta’s plenary conduct we used exploratory talk as theoretical basis to deliberate on her students’ responses (Mercer and Dawes 2008). Edwards (2009) highlights two significant aspects in our taking such actions. First, that both Lotta and I were not simply responding to each other but responding also to interpretations that either of us brought to bear. Second, our response to contradictions we faced (Engeström 2008) resulted in questioning the boundaries that lay between classroom teaching and research, with the resources at our disposal. Edwards explains,

In CHAT terms, relational agency is a capacity to work with others to expand that one is working on and trying to transform by recognising, examining and working with the resources that others bring to bear as they interpret and respond to the object…. It is therefore an enhanced version of personal agency that involves looking across organisational boundaries to make possible aligned and mutually supportive action outside the institutional shelters of specialist organizations.’ (2009, pp. 208–209)

In recognising relational agency as distributed across organisational boundaries, Edwards allows me to focus on pedagogical actions that Lotta brought to our collaboration and theoretical perspectives that I brought to her project. In doing so Edwards draws attention to two final aspects. First, she draws on Stetsenko (2005) to point out that the pursuit of any object impacts an individual’s subjectivity and changes how an individual approaches his or her object. This follows Leont’ev’s (1981) exposition in which any object is subjectivised in the individuals taking part in any activity, just as subjects are objectivised during their pursuit of the same. It was such a dialectic which informed our ability to take action as practitioners in Lotta’s classroom (Gade 2014). Second, Edwards highlights an issue of even greater importance, which is the conception of teacher as a collaborating professional. With significance to wider debate in contemporary times, Edwards (2010) forwards a relational turn in a teacher’s professional practice. Removed from conceiving teachers as heroic individuals with status of being able to work independently, Edwards argues that in order to deal with systemic issues, inescapable in teaching, the realisation of relational agency allows practitioners to draw on motives in response to objects of activities. I argue that it is such manner of relational agency between Lotta and me that expanded the object of our initial activity (Engeström 2001). Edwards explains the dynamic nature of such a two-stage process,

… I described relational agency as a capacity that emerges in a two-stage process within a constant dynamic, which involves: (i) working with others to expand the ‘object of activity’ or task being working on by recognising the motives and the resources that others bring to bear as they too interpret it; (ii) aligning one’s own responses to the newly enhanced interpretations, with the responses being made by the other professionals as they act on the expanded object. (2010, p. 64)

In jointly pursuing the expansive object of our collaborative activity, Edwards (2010) underscores such collaboration as being far from apprenticeship, one in which she would become more and more able over time. Rather, in a democratic manner and on very much an equal footing Lotta, as teacher, was contributing to the transformation that we were together were bringing about. I now turn to explore cogenerative dialogue, that lined our shared intersubjectivity.

Cogenerative dialogue: discussing shared praxis

My third and final construct understands teacher–researcher collaboration in terms of cogenerative dialogue, developed by Wolff-Michael Roth and Kenneth Tobin (2002) while coteaching with new teachers in ongoing science classrooms. In their book aptly titled At the elbow of another, Roth and Tobin develop this construct to highlight the importance of dialogue that transpires between a more experienced faculty and a new teacher. Developing their approach under an agentive framework of activity theory (Engeström 2001), Roth and Tobin combine critical psychology with hermeneutic-phenomenology to deal with and report on issues that new teachers face and need guidance with in classrooms set in challenging contexts. In doing so they direct attention to talk or discussion about actions taken in teaching, which they call cogenerative dialogue. Such talk (logos) about actions (praxis) which they term praxeology is both context specific, first-person and put forward as an alternative to the abstract theory which is then supposedly applied to any context. Roth and Tobin (2004) argue cogenerative dialogue to be a more effective investment in teacher education than teacher workshops, since dialogue generative in the contexts in which the teacher is to teach goes a longer way than prescriptive examples that may not be utilisable at all. I utilise the construct of cogenerative dialogue to analyse talk or dialogue that transpired between myself and Lotta as we analysed and prepared drafts during our co-authoring (Gade and Blomqvist, submitted). Unlike Roth and Tobin’s examples where they discuss actions taken with teachers in ongoing classrooms, the cogenerative dialogue I refer to transpired when Lotta and I met for four sessions during which we analysed Lotta’s plenary conduct of exploratory talk in relation to the topic of measurement (14th and 29th May 2012, 11th and 26th June 2012). During these sessions and towards our object of co-authorship, Lotta took on majority role of translating classroom talk which transpired with students in Swedish and I took on major role of transcribing talk, drafting and redrafting the research report for a journal article. In these sessions we dealt with issues related to Swedish and English usage on one hand and implications our work had in relation to societal contradictions at mid-level systemic levels on the other (Engeström 2001). I elaborate below the observations we made in these sessions giving our step-wise rubric of analysing students’ talk in Gade and Blomqvist (submitted). Such discussion or meta-talk is what Roth and Tobin (2004) identify as praxeology.

Gleaned from audio-recordings of our analytical sessions, cogenerative dialogue between Lotta and myself touched upon a variety of issues. I elaborate too that in Lotta’s plenary we had asked student pairs to respond to measures which were improbable like, Can Eva and Anton measure the length of Sweden on foot?, or Can Lars and Iris measure their age in decimeters? Via these questions we wished to challenge normative conceptions students had about measurements being made in their everyday. Lotta’s own role in conducting such a plenary included her guiding the use of talk by students, establishing and holding ground rules in place, making herself clear when necessary, nominating turn taking and directing attention of students who were distracted (Mercer and Dawes 2008). In summarising the issues that found voice in our cogenerative dialogue I first allude to the very reality of its conduct. As example we reflected on the sheer advantage of our being able to revisit Lotta’s plenary by listening to its audio-recording. The dilemma of students making meaning of improbable scenarios brought with it a lot of fun, leading us to break into laughter on many an occasion. In fact both of us were reminded of the popular Swedish children’s character Pippi Longstocking who did not want to bother with her lessons anymore, as she thought it important to look out for the next day’s weather. “This is not only about mathematics, there is so much more in it” Lotta said, adding that she learnt all the time from our exercise, enabling her to think of what she could do next time round in teaching. Our discussing the audio-recording was beneficial to see how various theoretical concepts forwarded by Lev Vygotsky or Douglas Barnes or Neil Mercer or Gordon Wells or Mikael Bakhtin was applicable to various snippets of students talk. Given that the topic of measurement was fertile ground for conceptualisation of both everyday and scientific concepts, we chose the Vygotskian (1978) bridge between everyday and scientific concepts belonging to students as our analytical rubric.

A good part of Lotta’s reflections during our cogenerative dialogue was about her students. For one Lotta felt they were very loyal to her. Putting her hand up in a manner her students would, Lotta understood her students as saying to her “Yes, you ought to have an answer… I give you an answer… Doesn’t matter even if it is crazy.” Lotta felt her students were loyal to each other too. She said “Mark needs to answer, let’s find an explanation for him.” In acknowledging the importance of the rules she implemented, Lotta laughed when she heard herself asking Jan or Noel or Iris or Karl to be quiet and concentrate. Yet Lotta said she made an effort to make her students feel comfortable. It was good enough if they took part in her plenary she thought, even if they did not necessarily have the right answers. As outlined in Gade and Blomqvist (submitted) and in line with this ethic, Lotta made special efforts to equalise the power relationships between herself and her students, by even standing in for a student. “I wanted to create trust and make the students comfortable because this was not an exercise from the textbook, but a new kind of lesson.” This concern was reflected in Lotta’s ending her plenary with asking students to respond to each of the ten questions they addressed with a yes or no. Asked why she conducted this exercise at the spur of the moment, one not planned for at all, Lotta explained that she wanted to bring closure to her lesson and show that “it was important work they had done today, not something fancy.” Just like starting a lesson, Lotta was keen that she closed the lesson, wanting to imply that a lesson with no page number to correspond with in an exercise book was just as important. “Next time I work with these questions I will be able to say, the goal for today is this and this and so and so” she said. Lotta also spent considerable time reflecting on Noel, a student who had voiced his skepticism. Unlike some other students who conceived the improbable questions we set to take place in a world where anything could happen Noel repeatedly exclaimed in disbelief “What, I don’t understand anything.” Lotta spoke poignantly and said Noel was hard work for a teacher, as it was difficult to bring him into discussion when he stood up and protested. He was taking part in the talk based lesson she said, but not engaging with the questions in the pedagogical game that unfolded. She also feared Noel stood up and spoke for many others who may have been quiet during her plenary.

It comes as no surprise that in our cogenerative dialogue we touched on other teachers we had also worked with. For example, I was reminded of my Rektor at the school I taught in India who insisted children have fun and develop a love for their subject content (Gade 2011). She would have enjoyed this I thought, acknowledging the extended influence her mentoring had on me. Lotta who spent time as a facilitator for mathematics in the local community recounted her own experience as well with a teacher whom I also knew. Lotta found Erik asking his students to follow an exercise routine of doing one question after another from their textbook. When Lotta showed him an activity with dice so that students would talk math, she found Erik to be concerned with the noise his students would make. “It is hard work to make teachers comfortable with talk based lessons, for they have no way of assessing how such lessons progress” Lotta said, even as she added “But how will students show to the teacher the knowledge they have?” Addressing more systemic issues that our collaboration was concerned with, Lotta recognised the need teachers had of a knowledgable partner, one who was able to be of assistance in their classrooms. She acknowledged this was hard to do since even if some researchers were willing, teachers often closed the door on themselves anyway. Almost as an answer to the problematic she raised, in the final moments of our fourth session Lotta asked me to mention in our article that I had been in her class for a long time. “The children are comfortable with you and that is really important” she concluded. “I have had many researchers who came to my class, sit for an hour at the back and leave thereafter.”

A case of expansive learning activity

In bringing my paper to a close by arguing my collaboration with Lotta to be a case of expansive learning activity, I first draw attention to an article by Jon Wagner (1997) in which he details three kinds of teacher–researcher agreements that could be entered into for empirical investigations—data-extraction, clinical and co-learning. While the first portrays the researcher outside school and practitioner inside, the second acknowledges special skills brought to any collaboration. Only in co-learning partnerships did researchers and practitioner engage in action and reflection so as to learn from each other. Seeking more explicit models of how researchers and practitioners make decisions, Wagner argues the issue of how they jointly determine which form of cooperation is best for them remains a key question. My response to Wagner lies in the historical trajectory of my collaboration with Lotta, wherein we invested ourselves in each other and nourished its growth one step at a time. More than learning in a cognitive sense, we were able to transform teaching with the resources we had at our disposal. Such transformation was built on our own praxis, from initially intervening in Lotta’s classroom to co-authoring research and contributing to human knowledge.

A good part of our transformation was guided by the strength of perspectives we brought to bear in our collaboration. In the first we recognised our co-knowing as our consciousness, one that originated in society, in which it was dynamically and dialectically produced (Leont’ev 1978). My study of such co-knowing however remained a methodological challenge, in that we conducted educational research aimed at coming upon sensitising concepts with which to articulate our theory of action (Elliott 1978). In these efforts I based my study on both CHAT and narrative perspectives. Two of the three constructs I deployed drew on experiential accounts that narrative perspectives so ably allow empirical access to, in concrete contexts (Polkinghorne 2010). The first of these was relational knowing (Hollingsworth et al. 1993) with which I focused on knowing that resulted for Lotta’s students, and Lotta and myself due to relationships we entered into, that were either intentional or resulted from our praxis as practitioners. My sitting silently beside Alex while he attempted his numerical crossword or Lotta’s talking to Felix’s mother when she wanted him to work with me, were examples of actions both of us took in building relationships to which students’ knowing was inextricably tied. In addition to students, the relationships we had with ourselves were critical in formulating action that we thought necessary (Hollingsworth 1992). Both in the action research we conducted (Gade 2012a) and in expanding the object of our activity (Leont’ev 1978) we at first acknowledged and then attempted to overcome our experiences of the contradictions we faced in our professional lives (Engeström 2008). The other construct that was narrative in spirit was that of cogenerative dialogue (Roth and Tobin 2002) which being hermeneutic-phenomenological and critical in outlook took into account the reflections that either of us had, when our dialogue or meta-talk was mediated by our experiences of Lotta’s plenary conduct (Gade and Blomqvist, submitted). This provided access to a depth of issues that praxis or praxeology as construct could encapsulate (Roth and Tobin 2004). On one hand there was expressed concerns of dealing with a student like Noel who, while taking part in Lotta’s plenary, was unable to fathom the pedagogical game that was played out since the measures being discussed were improbable. Listening to the audio-recording gave Lotta an opportunity to re-interpret the hands her students raised and the loyalty she thought they showed both to her and their peers. On the other there was pedagogical concern about how a talk based plenary could be given the status of a normative lesson in mathematics, as concerns of assessment overrode the opportunity that teachers could offer students wherein they could share the knowledge they themselves had. Finally we spent time on how to enrich praxis of teachers, when they might themselves shut the door in a hegemonic manner to any kind of assistance researchers may have to offer (Roth and Tobin 2004). It did not help either if researchers from the university came by to visit classrooms and did not contribute in any way to the nourishment of the praxis of students as well as teachers. The importance of stakeholder self, one’s being or ontology, therefore seemed as critical to curriculum reform (Kincheloe 2003) as methodological concerns in research for its conduct having educative, catalytic and tactical potential (Guba and Lincoln 1989).

Nested within the first and third, my second construct of relational agency (Edwards 2005) explicitly recognised the relational turn in expertise needed by teachers, if they were to meet with systemic issues that plague school teaching (Engeström 2008). Just as Edwards (2010) is critical of a false status of heroism that teachers are said to have in working independently, Roth and Tobin (2004) too caution that societal or institutional contradictions which teachers face at school can be hegemonic as well as internalised by them in classroom and/or subject teaching. The resources of project funding by Skolverket and my close-to-practice research stance (Edwards et al. 2002) had however placed teacher–researcher collaboration between Lotta and me in a resourceful position. It was based upon these that Lotta and I were able to realise enhanced agency and cross the boundary between university research and classroom teaching (Edwards 2009). It was these aspects too that contributed to changing the object of our activity, from classroom intervention to co-authoring research (Edwards 2010). With invaluable light shed on practitioner agency with relational knowing (Hollingsworth et al. 1993) and cogenerative dialogue (Roth and Tobin 2002) our collective activity was transformatory in line with what Engeström identifies as formative interventions,

Formative interventions may be characterized with the help of an argumentative grammar which proposes (a) the collective activity system as a unit of analysis, (b) contradictions as a source of change and development, (c) agency as a crucial layer of causality, and (d) transformation of practice as a form of expansive concept formation. (2011, p. 598)

I argue too that the forms of engagement or patterns of activity that Lotta and I engaged with over extended time exemplifies what Engeström terms as expansive learning activity,

The object of expansive learning activity is the entire activity system in which the learners are engaged. Expansive learning activity produces culturally new patterns of activity. Expansive learning at work produces new forms of work activity. (2001, p. 139)

By this is meant that in our collaboration Lotta and I carefully built upon nascent beginnings, like at first observing one another as professionals, while also conceiving our roles to be expansive in spirit so as to deal with societal and systemic contradictions and bring about transformation and change. In such conduct we not only addressed readership in research (Gade and Blomqvist, submitted) but also readership in teaching (Blomqvist and Gade 2013). This has not only meant that we treated our theory on par with practice, but vitally recognise that schools need to be for teachers, as much as they are also for students (Gade 2014). Such a stance has benefitted from conducting educational research and not research on education (Elliott 1978) inextricable linked as the former is also with ongoing educational practice (Cochran-Smith and Donnell 2006). Such efforts did produce new patterns of activity and forms of work, which we did not hesitate to take up in order to realise an expansive learning activity. I thus forward the insightful analytical constructs I deployed to be tools with which to study good practice and build good theory (Stetsenko 2004). Such tools have potential besides to sensitise both research and practice to develop a theory of action (Elliott 1978) and allow research to build cumulatively across similar situated collaborations (Cochran-Smith and Zeichner 2005). In other words the manner of consciousness and co-knowing Lotta and I were able to realise can always be produced (Leont’ev 1978). The notion of expansive learning activity which draws on shared praxis in everyday classrooms is thus far from a localised concept, but one universal both in appeal as well as conduct (Elliott 2009). Lotta initiated one when she entered into collaboration. “I will not die” she had thought, willing to take risks. On how else our collaboration will journey, is something that lies ahead.

References

Arbaugh, F., Herbel-Eisenmann, B., Ramirez, N., Knuth, E., Kranendonk, H., & Quander, J. R. (2010). Linking research and practice: The NCTM research agenda. Retrieved October 23, 2010, from website: http://www.nctm.org/news/content.aspx?id=25315.

Blomqvist, C., & Gade, S. (2013). Att kommunicera om likamedtecknet. Nämnaren, 4, 39–42.

Bodrova, E., & Leong, D. J. (2007). Tools of the mind—The Vygotskian approach to early childhood education. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (1998). Stories to live by: Narrative understandings of school reform. Curriculum Inquiry, 28(2), 149–164. doi:10.1111/0362-6784.00082.

Cochran-Smith, M. (2005). Teacher educators as researchers: Multiple perspectives. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(2), 219–225.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Donnell, K. (2006). Practitioner inquiry: Blurring the boundaries of research and practice. In J. L. Green, G. Camilli, & P. B. Elmore (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (pp. 503–518). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Fries, K. (2008). Research on teacher education: Changing times, changing paradigms. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, & D. J. McIntyre (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education: Enduring questions in changing contexts (3rd ed., pp. 1050–1093). New York: Routledge.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. (1999). The teacher research movement: A decade later. Educational Researcher, 28(7), 15–25.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Zeichner, K. (2005). Executive summary. In M. Cochran-Smith & K. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education (pp. 1–36). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Craig, V. J., & Ross, V. (2008). Cultivating the image of teachers as curriculum makers. In M. F. Connelly, M. F. He, & J. Phillion (Eds.), The Sage handbook of curriculum and instruction (pp. 282–305). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Day, C. (1997). Working with different selves of teachers: Beyond comfortable collaboration. In S. Hollingsworth (Ed.), International action research: A casebook for educational reform (pp. 190–203). London: Falmer Press.

Edwards, A. (2005). Relational agency: Learning to be a resourceful practitioner. International Journal of Educational Research, 43, 168–182.

Edwards, A. (2009). From the systemic to the relational: Relational agency and activity theory. In A. Sannino, H. Daniels, & K. Gutierrez (Eds.), Learning and expanding with activity theory (pp. 197–211). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Edwards, A. (2010). Being an expert professional practitioner: The relational turn in expertise. Dordrecht: Springer.

Edwards, A., Gilroy, P., & Hartley, D. (2002). Rethinking teacher education: Collaborative responses to uncertainty. Cornwall: RoutledgeFalmer.

Elliott, J. (1978/2007). Classroom research: Science or commonsense. In J. Elliot (Ed.), Reflecting where the action is: The selected works of John Elliott (pp. 91–98). Wiltshire: Routledge.

Elliott, J. (2009). Research-based teaching. In S. Gewirtz, P. Mahony, I. Hextall, & A. Cribb (Eds.), Changing teacher professionalism: International trends, challenges and ways forward (pp. 170–183). London: Routledge.

Ellis, V. (2011). Reenergising professional creativity from a CHAT perspective: Seeing knowledge and history in practice. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 18(2), 181–193.

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 133–156.

Engeström, Y. (2008). Crossing boundaries in teacher teams. In Y. Engeström (Ed.), From teams to knots: Activity-theoretical studies of collaboration and learning at work (pp. 86–107). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y. (2011). From design experiments to formative interventions. Theory and Psychology., 21(5), 598–628.

Etherington, K. (2006). Reflexivity: Using our ‘selves’ in narrative research. In S. Trahar (Ed.), Narrative research on learning: Comparative and international perspectives (pp. 77–92). Oxford: Symposium Books.

Finlay, L. (2002). “Outing” the researcher: The Provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qualitative Health Research, 12(4), 531–545.

Gade, S. (2010). Narratives of students learning mathematics: Plurality of strategies and a strategy for practice? In C. Bergsten, E. Jablonka, & T. Wedege (Eds.), Mathematics and mathematics education: Cultural and social dimensions Proceedings of the seventh mathematics education research seminar MADIF7 (pp. 102–112). Stockholm: Stockholm University.

Gade, S. (2011). Narrative as unit of analysis for teaching-learning praxis and action: Tracing the personal growth of a professional voice. Reflective Practice, 12(1), 35–45. doi:10.1080/14623943.2011.541092.

Gade, S. (2012a). Teacher researcher collaboration at a grade four mathematics classroom: Restoring equality to students usage of the ‘=‘ sign. Educational Action Research, 20(4), 553–570.

Gade, S. (2012b). Close-to-practice classroom research by way of Vygotskian units of analysis. Paper presented at Topic Study Group (TSG 21) Research on classroom practice. In Proceedings of the 12th international congress on mathematics education (ICME), (pp. 4312–4321) 8–15 July 2012, Seoul, South Korea.

Gade, S. (2014). Practitioner collaboration at a grade four mathematics classroom—By way of relational knowing and relational agency. In F. Rauch, A. Schuster, T. Stern, & A. Townsend (Eds.), Promoting change through action research—International case studies in education, social work, health care and community development. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers B.V.

Gade, S., & Blomqvist, C. (2014). “Crooked Carsson had 160 kronor. He bought a robot for 50 kronor and the entire universe for 50 kronor” From problem posing to posing problems by way of explicit mediation at grades four and five. In F. M. Singer, N. Ellerton, & J. Cai (Eds.), Problem posing: From research to effective practice. New York: Springer.

Gade, S., & Blomqvist, C. (submitted). Investigating everyday measures through talk: Whole classroom intervention and landscape study at Grade four.

Gallego, M. A., Hollingsworth, S., & Whitenack, D. A. (2001). Relational knowing in the reform of educational cultures. Teachers College Record, 103(2), 240–266.

Greene, M. (1979). Teaching as personal reality. In A. Liberman & L. Miller (Eds.), New perspectives of staff development (pp. 23–35). New York: Teacher College Press.

Guba, E., & Lincoln, Y. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Gudmundsdottir, S. (2001). Narrative research on school practice. In V. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (4th ed., pp. 226–240). Washington, DC: American Education Research Association.

Hollingsworth, S. (1992). Learning to teach through collaborative conversation: A feminist approach. American Educational Research Journal, 29(2), 373–404.

Hollingsworth, S., & Dybdahl, M. (2007). Talking to learn: The critical role of conversation in narrative inquiry. In J. Clandinin (Ed.), Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping a methodology (pp. 146–176). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hollingsworth, S., Dybdahl, M., & Minarik, L. T. (1993). By chart and chance and passion: the importance of relational knowing in learning to teach. Curriculum Inquiry, 23(1), 5–35. doi:10.2307/1180216.

Kincheloe, J. (2003). Critical ontology: Visions of selfhood and curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 19(1), 47–64.

Krainer, K. (2011). Teachers as stakeholders in mathematics education research. In B. Ubuz (Ed.), Proceedings of the international group of psychology of mathematics education (PME) (pp. 1–47, 1–62) 10th–15th July, Ankara, Turkey.

Leont’ev, A. N. (1978). Activity, consciousness, and personality. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Leont’ev, A. N. (1981). The problem of activity in psychology. In J. V. Wertsch (Ed.), The concept of activity in Soviet psychology (pp. 37–71). Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Mercer, N. (2004). Sociocultural discourse analysis: Analyzing classroom talk as a social mode of thinking. Journal of applied linguistics, 1(2), 137–168.

Mercer, N., & Dawes, L. (2008). The value of exploratory talk. In N. Mercer & S. Hodgkinson (Eds.), Exploring talk in schools (pp. 55–71). London: Sage.

Niss, M. (2007). Reflections on the state of and trends in research on mathematics teaching and learning. In F. Lester (Ed.), Second handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (pp. 1293–1323). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishers.

Noddings, N. (2012). The caring relation in teaching. Oxford Review of Education, 38(6), 771–781.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1997). Reporting qualitative research as practice. In W. G. Tierney & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Representation and the text: Reframing the narrative voice (pp. 3–21). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (2010). The practice of narrative. Narrative Inquiry, 20(2), 392–396.

Roth, W.-M., & Tobin, K. (2002). At the elbow of another—Learning to teach by coteaching. New York: Peter-Lang Publishing.

Roth, W.-M., & Tobin, K. (2004). Coteaching: From praxis to theory. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 10(2), 161–179.

Smith, T. (2008). Fostering a praxis stance in pre-service teacher education. In S. Kemmis & T. Smith (Eds.), Enabling praxis: Challenges for education (pp. 65–84). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Stetsenko, A. (2004). Introduction to scientific legacy: Tool and sign in the development of the child. In R. W. Rieber & D. K. Robinson (Eds.), The essential Vygotsky (pp. 501–512). New York: Kluwer/Plenum Publishers.

Stetsenko, A. (2005). Activity as object-related: resolving the dichotomy of individual and collective planes of activity. Mind, Culture and Activity, 12(1), 70–88.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wagner, J. (1997). The unavoidable intervention of educational research: A framework for reconsidering researcher-practitioner cooperation. Educational Researcher, 26(7), 13–22.

Wardekker, W. (2010). Afterword: CHAT and good teacher education. In V. Ellis, A. Edwards, & P. Smagorinsky (Eds.), Cultural-historical perspectives on teacher education and development (pp. 241–248). New York, NY: Routledge.

Wertsch, J. V. (2007). Mediation. In H. Daniels, M. Cole, & J. V. Wertsch (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to Vygotsky (pp. 178–192). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Winter, R., Buck, A., & Sobiechowska, P. (1999). Art of professional reflection. London: Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Lead Editor: K. Tobin.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gade, S. Unpacking teacher–researcher collaboration with three theoretical frameworks: a case of expansive learning activity?. Cult Stud of Sci Educ 10, 603–619 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-014-9619-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-014-9619-7