Abstract

Coteaching is an effective structure for the pre-service practicum as it immerses student teachers in the culture of the school and helps them to learn by working closely at the elbows of their mentor teacher. The collaborative nature of the model fosters beliefs and practices based on shared perspectives and coresponsibility for the quality of the learning environment. Cogenerative dialogues with students insure the inclusion of their voice in the collaboration and foster increased emotional energy and classroom solidarity. The work by Wassell and LaVan (2009) fills an important void in our research on coteaching as it seeks to understand which practices and beliefs survive the transition to professional service. While both teachers included cogenerative dialogues in their interactions with students, we suggest that the reflective practices of a single teacher are qualitatively different from reflections based on the dynamic interactions of multiple adults’ coteaching together. We explore strategies that will help administrators and school staff find the human and material resources needed to staff the multiple teacher classroom. Our comments on this paper are informed by our experiences as the academic coordinator and mentor teacher of the learning community in which Jen and Ian completed their pre service practicum and are meant help disseminate this model to as many educational environments as possible.

Abstracto

El Coteaching es una estructura eficaz para la practica antes del servicio profesional, porque esto sumerge los estudiantes de maestría en la cultura de la escuela y los ayuda a aprender trabajando estrechamente “a los codos” de su profesor consejero. La naturaleza de colaboración del modelo fomenta creencia y prácticas basadas en perspectivas compartidas y co-responsabilidad por la calidad del ambiente de aprendizaje. Los diálogos-cogenerativos con estudiantes aseguran la inclusión de voces estudiantiles en la colaboración y aumentan la energía emocional y la solidaridad del aula. El trabajo por Wassell y Lavan llena un vacío importante en nuestra investigaciones sobre coteaching porque trata de entender qué prácticas y creencias sobreviven la transición al servicio profesional. Mientras ambos estudiantes de maestría fueron capaces de incluir diálogos-cogenerativos en sus interacciones con estudiantes, sugerimos que las prácticas reflexivas de un profesor solo son cualitativamente diferentes de reflexiones basadas en las interacciones dinámicas de varios adultos enseñando juntos. Exploramos estrategias que ayudarán a administradores y personal escolar encontrar los recursos humanos y materiales necesarios para proveer la aula con varios profesores. Nuestros comentarios sobre este papel son informados por nuestras experiencias como las de el profesor consejero y coordinadora académica de la comunidad en la cual Jen e Ian completaron su practica, y son escritas con la intención de diseminar este modelo a tantos ambientes educativos como posible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Recent research has shown the coteaching model to be an effective teaching modality that allows teachers to engage in a dynamic collaboration informed by multiple perspectives on the unfolding classroom reality. The collaborative nature of coteaching fosters a shared responsibility for the learning environment and makes possible the immediate response to circumstances detrimental to successful student engagement. Post teaching reflections allow for more substantive articulation of each coteacher’s perspective on the enacted curriculum and help guide the coplanning of subsequent lessons (Roth et al. 2000). These aspects of the coteaching model make it a superior alternative to the traditional pre service practicum as it immerses student teachers in the classroom culture and allows them to learn the craft of teaching by working closely “at the elbows” of an experienced mentor teacher (Roth et al. 2004).

The literature on coteaching is however, limited, as the majority of the collaborations have occurred during preservice student teacher internships. Thus, the extant research base has not addressed the vital question of the transferability of the practices of coteaching from the pre service practicum to professional service. This article fills a much needed void in the literature as it seeks to determine which practices (and beliefs) of the coteaching experience survive the transition to professional service and remain as viable components of the teacher’s daily praxis.

Our comments in this forum are informed by our experiences as administrator and mentor teacher in the learning community in which Ian and Jen completed their student teacher practicum. They are grounded in our genuine belief in the efficacy of the model and are intended to help extend it to as many academic institutions as possible. Our critiques are based on our understanding that, in all cultural fields, contradictions exist in a dialectical relationship with coherences (Sewell 1992) and that is through the exploration of those contradictions that one can discover resolutions to problematic circumstances. We will therefore highlight the contradictions in this paper in order to explore possible solutions to factors that may limit the feasibility of coteaching. We feel that this is a necessary focus of this forum because many experienced educators will quickly recognize the many fiscal and staffing issues that problematize coteaching collaborations and erroneously assume the model impractical. We begin with comments on the preservice practicum.

The preservice practicum

Cristobal: The professional relationship between participants is central to the coteaching model because coteachers rely on each other’s support in the interpretation of classroom events and the enactment of the shared curricular goals (Tobin et al. 2003). Each teacher in this study noted that the professional relationship with their fellow teacher was intellectually fruitful, contributed significantly to the development of their teaching practices and enhanced the quality of interactions in the learning environment. I would point out that these collaborative relationships extend beyond the classroom field, and include administrators, other members of the instructional staff, and school support personnel because their participation is necessary for the successful enactment of this model. Thus, the successful enactment of coteaching depends on a complex of professional relationships and collaborations in several cultural fields within the school. The centrality of collaboration between a variety of individuals in the many coteaching fields, might suggest that amicable, collegial relationships, and shared educational perspectives are the norm or that they are indispensable components of the coteaching model. While it is true that collaborations function more smoothly when participants are guided by similar belief systems, readers of this forum will know that it is unrealistic (given the many different life histories that converge in most school settings), to expect that administrators, teachers, and support staff will have similar educational perspectives. The teachers in this study were members of a graduate program in education, thus they shared common epistemological and pedagogical perspectives, which contributed to their collegial relationships and successful collaboration. It is important to note that in most schools, participants in the coteaching field will have dissimilar orientations on many key aspects of teaching and learning.

My experiences with coteaching have been generally positive, however, some events have proven that less positive, fractious situations can unfold when coteachers hold different views of the curriculum or pedagogical practice. When this occurs, they are unable to build solidarity between themselves or with their students and the environment is no longer conducive to shared perspectives or coresponsibility for student engagement (Tobin et al. 2003).

Although I am suggesting that dissimilar orientations are a source of friction and disharmony, I am not arguing against them. I would suggest that difference (pedagogical, epistemological, philosophical disagreements) between coteachers is (under the right circumstances) a powerful motive for self-examination and change. Difference achieves this because it does not allow for the reinforcement of the acceptable or the familiar, rather it provokes the examination of one’s assumptions, and challenges our orthodox, habituated thoughts.

[The] new – in other words difference – calls forth forces in thought which are not the forces of recognition, today or tomorrow, but the powers of a completely other model from an unrecognized and unrecognizable terra incognita. (Deleuze 1994, p. 136)

This is certainly true in my experience because I find (in retrospect), that the more difficult coteaching events forced me to reexamine my perspectives in light of those represented by my coteachers. Recognizing new models of thought and respecting difference within the classroom field does not necessarily guarantee successful collaborations. The functionality that helps foster positive collaboration within differences is the cogenerative dialogue, which has been proven effective at establishing communication across cultural and philosophical borders. Cogenerative dialogues promote frank, open discussions of contradictions in the learning environment and produce resolutions that honor the perspectives of all participants in the coteaching field (Roth et al. 2000). Difference among coteaching participants can remain productive as long as there is constant communication during the lessons (huddles), genuine, open debriefings between teachers and regular cogenerative dialogues between coteachers and with their students.

Clare: I agree that coteaching is a very useful teaching collaboration, but I think that finally the model is meant to improve student achievement. This paper and most of the research literature focuses on the teacher’s practice or the quality of interactions in the classroom, but little is said about student achievement. Even though I fully support coteaching I know that in order to fully substantiate the claims of the merits of this model, it might prove useful to know how it affects student’s understanding of the science curriculum. If coteaching is to get a stronghold in classrooms, we need to be able to quantify how the model affects student achievement. This is a crucial concern in the environment that No Child Left Behind (NCLB) has created where accountability for student performance is the central preoccupation of administrators and district science supervisors. Ethical teachers have always held themselves accountable for their students and their achievement, but performance scores on standardized tests are the currently accepted measures of the efficacy of a learning environment. Although it is implied that students are more engaged and responsive in the coteaching environment, there is no proof that the increased solidarity and emotional energy translated into increased student achievement. I think those of us who have experienced coteaching feel that this is likely true, but other readers might question our claims without “hard evidence”.

Cristobal: Accountability should be a central concern because the reality in most schools is that teachers (and their administrators) are held responsible for student performance on high stakes standardized tests. Interested educators will wonder how we address this issue given our nation’s current fixation with standardized measures of achievement. The focus of this study is on the teacher’s practice thus it is understandable that student performance data is not a primary concern however it is necessary that our future studies on coteaching address student achievement as it is a reality that few educators can avoid. The research literature of the DUS group has shown that the learning of science is positively affected when teachers address structures in the classroom field that diminish student agency or create impenetrable cultural barriers (Carambo 2009). All of the work provides extensive ethnographic data to support the claims of increased student engagement, heightened emotional energy, and a genuine communal responsibility to the learning of science. Although these are all primarily ethnographic qualitative data, all educators will recognize that heightened engagement and communal responsibility are prerequisites to increased achievement in science learning. The short vignette of Jen’s cogenerative dialogue clearly shows students that are engaged and able to contribute to the structures of their learning. The comment by the student Tanya in Jen’s class is evidence of the heightened engagement and sense of solidarity of the students in this learning environment.

Ms. Beers does not always just tell us what we need to know anymore. We have real conversations about what we think about the topics. (Wassell and Lavan 2009)

It would be helpful however, if future studies included some measures of quantitative data so as to address concerns of more skeptical readers, so as to more fully substantiate our claims that coteaching positively affects student achievement.

Clare: The question of who is “officially” accountable to students, parents, and administrators is central to the issue of accountability because all schools will designate a “teacher of record” who is responsible for grades, parent conferences, official records, and all problems in the classroom. Their administrator will also be responsible to the principal for teacher performance and student outcomes. We were fortunate in our small learning community because when we began the coteaching experiments, the principal, the mentor teachers, and the university partners were all of the same mindset and felt a shared responsibility for accountability. Therefore, no one person was “officially” accountable: we shared the responsibilities equally. Recently I spoke with a teacher in a coteaching field and he was very concerned because whenever “problems” arose, he was expected to “handle” them alone. The coteaching did not extend to the interactions with parents, problem students, or the administration because his name appears as the teacher assigned to that class. This problem can be resolved if the coteachers, and administrators create a system of sharing the duties and responsibilities as part of their coteaching field, then the teacher of record will not need to take sole responsibility for the problems that arise. One teacher’s name may be the “official” name, but the important tasks and responsibilities will be shared. We can accomplish this in the preplanning conferences between administrators and coteachers.

Cristobal: We have mentioned that coteaching model is vastly superior to the traditional student internship, which privileges the voice of a solitary teacher and perpetuates the veteran/novice teacher dichotomy. The student teacher in these circumstances remains isolated from the class and fails to develop any tools for understanding student cultures (Roth et al. 1999). An extremely important aspect of the coteaching model is the space it provides for teachers and students to break down cultural borders in a trusting atmosphere. The structure of the coteaching experience helps teachers develop the tools and insights needed to genuinely value and interact with cultural others. Both teachers mention the development of their understanding of student perspectives and their ability to cross cultural borders as one of the more important abilities they developed during their preservice coteaching experiences. Their understanding of students and willingness to eliminate cultural borders carried over into their first year praxis and helped them to quickly build trusting relationships across the cultures in their new schools.

The negotiation of cultural borders is of paramount importance in fields where participants are from radically different life worlds. Classrooms where cultures function to isolate and protect participants from symbolic violence are not conducive to the building of solidarity or the enactment of a transformative curriculum (Aikenhead 1996). This is one of the central constructs of the sociocultural perspective that informs the coteaching model and is one of the most important understandings of the research literature of the DUS research project (Carambo 2009).

I would suggest that the ability to efficiently build genuine trusting relationships across cultural borders has profound implications for the longevity of a teacher in settings in which they are a cultural other (Ladson-Billings 2001). My personal experience is proof of this as my enculturation into City High would not have been possible without the presence of my coteachers. I ascribe my longevity and ability to successfully interact with a large number of students to my ability to teach across cultural borders. For this reason, I would suggest coteaching as a model for all preservice teachers as it may be the best way to provide them a valuable tool for easing the tensions of the first years of inservice teaching and perchance lowering the attrition rates of teachers in culturally diverse circumstances.

The transition to professional practice

I miss Evan often when I am doing work by myself with no one to bounce ideas of. I don’t feel uncomfortable teaching without him here, but when it is prep time or after school, it is boring. It is true that teaching is lonely. It’s good to discuss the class as it ends with a peer. (Wassell and LaVan 2009)

Most schools are not able to assign two certified teachers to a single classroom. It is therefore not surprising that Jen and Ian were assigned to teach in the traditional one teacher classroom, thus losing a central component (and the associated benefits) of the coteaching model. It is clear from the comment quoted above that the absence of the second coteacher made their teaching a “lonely”, “isolated” experience, that lacked the perspectives and insights of the coteaching partner. Although both teachers made adjustments to their professional practice consistent with the understanding gained during their coteaching experiences, their use of cogenerative dialogues alone does not reproduce the quality of reflective practice or shared responsibility that exists when multiple adults are present. We understand that cogenerative dialogues serve to give teachers an understanding of student’s perspectives of the learning environment, and offer the students a credible mechanism to include their voices in the management of the learning environment. Coteaching however is predicated on the real time collaboration of several adults actively engaged in the creation and assessment of the learning environment (Roth et al. 2000). The nature of reflections and communal understandings developed solely through cogenerative dialogues with students is qualitatively different from understandings that emerge during classroom interactions. Schön (1983) makes a distinction between reflection in action (reflection during the “action present”) and reflection on action (which occurs after an event has transpired) that we find relevant to this discussion. Reflecting with students after classroom instruction is an example of reflection on action and cannot replicate the depth of understanding that emerge when two teachers cohabit the classroom and cooperate on the variety of actions needed to successfully teach a science lesson.

This “being with another” is central to the “development of shared experiences (e.g. during collective reflection-in-action) and therefore a common ground that served as a communicative basis so important for mutual understanding” (Roth et al. 1999, p. 782). For these reasons we feel that any consideration of the practices learned from coteaching must be considered in, circumstances where multiple adults are physically present in the classroom. Our discussion in this part of the forum will therefore address the structural impediments to the coteaching model and explore modifications to the school’s structure that may provide the human and material resources needed to enact the model.

Clare: Students respond positively when they learn meaningful content, in an environment informed by high academic standards, from teachers that believe in their abilities, and are confident that those high standards can be met. While it is true that a good teacher is capable of creating such a learning environment on her own, our experience has shown that when more than one professional is in a class, students pay more attention, there is more activity, less down time, and there are fewer disruptions because they feel their educational needs are efficiently met. Cogenerative dialogues remain an efficient tool for creating a positive learning environment, but they cannot by themselves, replicate the vibrancy of a classroom where coteaching is in place. The model is difficult to enact because most schools are allocated teaching positions based on student enrollment and they cannot assign two certified teachers to a single classroom.

Cristobal: Nearly all of the studies that inform the coteaching model include a veteran and a student teacher from a local university. Given that student teachers are not “official” teachers, they do not affect the school’s budget or teacher allocation ratio. This is not the case in most school districts where structural and fiscal constraints seriously limit a school’s resources and thus preclude the assignment of two teachers to a single classroom. Any educator who considers coteaching to be a viable pedagogical model may therefore deem the model unrealistic. While we agree that such constraints are formidable, we feel that the benefits of coteaching are such that we must explore possible models that one may present to school administrations. These suggestions might allow for the assignment of two teachers (or other professionals) to one classroom on a limited or if possible permanent basis. Our first concern should be on finding the additional human resources or changes to the school’s structure (for example: modified teacher schedules, split rosters, alternating block schedules) that will permit us to assign multiple adults to one classroom.

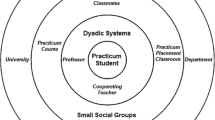

Clare: I think we are obliged to address the other fields and structural components that intersect with the coteaching model in order to establish it as a viable and fiscally responsible teaching method. We need to include everyone because coteaching when done well affects the entire school community but it needs the support of a wide range resources. Let me begin with the roles of various members of a school community and examine how their involvement can help establish coteaching collaborations.

Applying a coteaching model can’t be properly done without the consent of the school administrator, so the question we have is how to persuade school administrators to regard the coteaching model as deserving of major budget and roster deliberations and design. Administrators begin thrashing out budget figures after the first of the year and any requests from teachers must be on the table at this point. Those requests include teacher requests for resources, roster changes, and classroom supplies. If we can establish the coteaching assignments, content area, and budgetary considerations in the early months of the year, we will garner administrative support and the time to plan the September co-teaching.

One strategy that we used in our school was pairing teachers from different learning communities together. Our block schedule allowed us to roster small classes to these teachers which they could coteach together. The pairing allowed us to create a two teacher classes while avoiding the scheduling and budgetary issues. Schools with block schedules can explore this option to make the model less of a strain on budgets and teacher allocation. Once we had organized our ideas, we took the plans to the administration for their input and support.

Our experience with coteaching is that it demands more material and human resources than most schools have. We therefore recommend that schools pursue partnerships with local universities, community agencies, and the business community. Partnerships with professional and educational institutions may provide needed material resources to offset the financial limitations of most school budgets. School administrators can establish partnerships with the businesses, local community groups, other educational institutions (i.e. libraries, museums), and community entrepreneurs as potential sources of coteachers. These institutions can underwrite the budget for the time these professionals spend in the classroom. The coteachers from these institutions can involve students in professional internships or research projects that would extend student learning beyond the classroom field. We have introduced pairing teachers of different content areas on a block schedule and developing partnerships with community, professional, and educational groups as potential resources for the coteaching model. Schools wishing to enact coteaching may look closely at all members of the school community as potential human resources. Building engineers, maintenance workers, cafeteria workers, office staff, nurses, and administrators are untapped resources, whose experiences and real world knowledge can contribute significantly to student learning.

Cristobal: Our experience with the first coteaching experiment in our Science Engineering class was just this type of collaboration. This was the class where Ian cotaught with Evan. It involved a mentor teacher, the coteachers, and an experienced automobile mechanic from another learning community in the school. The auto mechanic teacher’s budget line was partially underwritten with funds that were not part of the general operating budget. He was not a certified teacher, however his expertise in auto mechanics was an indispensable component of the physics–engineering course. The initial planning meetings were dedicated to establishing the epistemological and pedagogical context of the class. Ongoing cogenerative dialogues between all participants ensured that the environment remained responsive to the needs of the four coteachers and the students in the class. We were able to use him as a coteacher because the principal helped modify his teaching schedule so that there was a common time for the two classes to meet. Roistering kept the classes small enough so that the two teachers were able to teach at the same time. Planning and debriefings were held during common preps. A similar type of scheduling plan could allow teachers to teach at the same time. This type of scheduling demanded the help of the principal, roster chair and (in our school, the academic coordinator). Our partnerships with two local university and their outreach programs, provided the needed material resources. Without the assistance and belief of the varied participants in these different fields, we would not have been able to enact coteaching.

We are aware that many impediments exist to the successful enactment of this model in circumstances outside of the student teacher practicum. However, we know that committed administrators and teachers can work together to overcome these obstacles (Muraski and Diecker 2004).

The necessity of reflective practice

The authors report that the coteaching experience fostered an affinity for reflective practice that transferred to the teacher’s professional service and will remain a key part of their daily praxis. Although we have commented on the qualitative difference between reflection in action versus reflection on action, we feel that reflective practice (whenever it occurs) is an essential aspect of all quality-learning environment.

Reflective practice is however, a practice that veteran teachers seldom engage in given the hectic pace of our days, the constant influx of new curricular priorities, and the demands from administrators, and parents. The time to reflect on our practice and arrive at reasoned, well-grounded critiques of praxis has become a “luxury” many practicing teachers have lost. This is unfortunate as self-critique and analysis of one’s teaching is the best manner that teachers can contribute to their own growth and development as educators. Reflective practice is not simply mulling over the day’s events. Reflection implies a critical perspective and thus demands input from colleagues and fields outside of one’s classroom. The coteacher’s reflective practice during their practicum was informed by their participation in other fields (the DUS research group, their graduate classes, and fellow coteachers in the school) thus it was scholarly and informed by a multiple perspectives. This continued to a degree during their work with the researchers in this study and their ongoing engagement with members of the DUS. Professional veteran teachers who teach in isolation have no such community or literature base to use in their reflective practice. The collaborative nature of coteaching establishes an intersection of fields, which foster and support reflective practice. We agree with the authors that more research on the structures that enable reflective practice of pre service teachers is warranted. We hope that future research included ways that the coteaching collaboration can reintegrate reflective practice into the lives of practicing teachers.

References

Aikenhead, G. S. (1996). Science education: Border crossings into the subculture of science. Studies in Science Education, 27, 1–52. doi:10.1080/03057269608560077.

Carambo, C. (2009). Evolution of an urban research program: The Philadelphia project. (in press).

Deleuze, G. (1994). Difference and repetition (Trans: Tomlinson, H. & Galeta, R.). Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press (Original work published 1969).

Ladson-Billings, G. (2001). Crossing over to Canaan. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Muraski, W. W., & Diecker, L. A. (2004). Tips and strategies for coteaching at the secondary level. Teaching Exceptional Children, 36(5), 52–58.

Roth, W.-M., Lawless, D., & Tobin, K. (2000). {Coteaching|Cogenerative Dialoguing} as praxis of dialectic method. Forum: Qualitative Research, 1(3). http://qualitative-research.net/fqs/fqs-eng.htm. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

Roth, W.-M., Masciotra, D., & Boyd, N. (1999). Becoming-in-the classroom: A case study of teacher development through coteaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 15, 771–784. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00027-X.

Roth, W., Tobin, K., Carambo, C., & Dalland, C. (2004). Coteaching: Creating resources for learning and learning to teach chemistry in urban high schools. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41, 882–904. doi:10.1002/tea.20030.

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Sewell, W. H. (1992). A theory of structure: Duality, agency, and transformation. American Journal of Sociology, 98, 1–29. doi:10.1086/229967.

Tobin, K., Zurbano, R., Ford, A., & Carambo, C. (2003). Learning to teach through coteaching and cogenerative dialogue. Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 10(2), 51–73.

Wassell, B., & LaVan, S. K. (2009). Tough transitions? Mediating beginning urban teachers’ practices through coteaching. Cultural Studies of Science Education. doi:10.1007/s11422-008-9151-8

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carambo, C., Stickney, C.T. Coteaching praxis and professional service: facilitating the transition of beliefs and practices. Cult Stud of Sci Educ 4, 433–441 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-008-9148-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-008-9148-3