Abstract

Total knee replacement (TKR) infection represents only a small percentage of all the potential complications in joint replacement, but one that can lead to disastrous consequences. Two-stage revision, which has been proven to be the most effective technique in eradicating infection, includes prosthesis removal, positioning of an antibiotic-loaded spacer, and systemic antimicrobial therapy for at least 6 weeks. It has been suggested that there is better performance in terms of range of motion, pain, extensor mechanism shortening, and spacer-related bone loss if articulating spacers are used instead of fixed spacers. In this paper, we describe our results in two-stage revision of infected total knee arthroplasty with a minimum follow-up of 12 months on 14 patients treated by antibiotic-loaded custom-made articulating spacer as described by Villanueva et al. (Acta Orthop 77(2):329–332, 2006). The mean flexion achieved after the second stage of the revision was 120°, ranging from 97° to 130°. The mean Hospital for Special Surgery score was 84. At 1 year after surgery, none of the knees showed any evidence of recurrence of the infection. Articulating spacers are a suitable alternative to fixed spacers with good range of motion after reimplantation and effectiveness against total knee replacement deep infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Deep infection rates in total knee joint replacement vary in the published literature between 0.3% and 2.9% [2, 3]. Although newer surgical techniques and modifications in preoperative and postoperative care have lowered the overall rate of infections, infection remains a devastating complication for a patient. There are several options to treat an infected knee replacement, the choice of which depends on the time of onset, the microorganism, and radiological exams. These options range from prosthesis retention [13] for early infections up to revision arthroplasty, resection arthroplasty, and arthrodesis.

Literature data [4–7, 10, 16] support the effectiveness of two-stage revision using cement antibiotic combined with intravenous therapy spacers. Fixed spacers are not without their own potential complications including bone loss, pain, and muscle and extensor mechanism contracture.

In an attempt to obviate these problems, surgeons have considered using mobile spacers, which allow partial weight bearing and a limited range of motion up to 90° of flexion [11]. Mobile spacers can be fashioned in different manners. In one technique, the removed femoral component is steam-sterilized and loosely reimplanted with antibiotic-loaded cement [10]. On the tibial side, a new polyethylene insert is again loosely implanted with antibiotic-loaded cement. In another technique [12], premolded antibiotic spacers (Stage One [Biomet, Warsaw, IN] or Prostalac) are used. In a third technique, first described by Villaneuva et al. [1], Ha [14], and Goldstein [15], custom-molded spacers were used. This is the technique that we used in our series.

Materials and methods

Between June 2005 and February 2006, we performed 14 (11 females, 3 males) two-stage revision arthroplasties (TKR) revisions using custom mobile spacers. Each patient was diagnosed as having a deep infection, supported by joint fluid aspiration, leukocytes bone scan, and radiological signs of loosening.

Patients’ mean age at the time of revision was 68 years (range 60–76 years). The mean period since index knee replacement was 2.3 years, ranging from 12 months to 3 years. The mean flexion was 73.5° with a mean flexion contracture of 4°.

The isolated microbial agent was Staphylococcus epidermidis in 10 cases, whereas the others were Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Every agent was found sensible to Tobramicyn, except for the two cases of S. aureus isolation that were found sensible to Vancomicyn.

Each patient was treated with a two-stage revision using an articulating antibiotic-loaded spacer as described by Villanueva et al. [1]. Simplex bone cement (Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA) was mixed with powdered antibiotic, the choice of which was dependent on the microbial isolation. We added 1 g/dose of Vancomicyn to the cement in those cases in which microbial contamination was resistant to Tobramicyn (already in the powered part of Simplex added cement). The cement is then molded on the debrided bone using curved retractors and a drill to reproduce the trochlear groove (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11).

The postoperative rehabilitation protocol was the same for each patient. On the first postoperative day, patients were started on continuous passive motion. They were also allowed to begin ambulating bearing weight on the affected extremity, using a brace to lock the knee in full extension. No patient was allowed to flex the knee above 90° till the revision. Parenteral organism specific intravenous antibiotics therapy was started as soon as joint aspiration confirmed infection, and continued for at least 6 weeks. Before revision, a new aspiration was performed, confirming no microbial contamination and no signs of inflammation in joint fluid. The second stage consisted of the removal of the articulating spacer and then reimplantation of a new prosthesis. The minimum time for reimplantation was 6 weeks and the maximum was 11 weeks with a mean value of 9 weeks. In four patients, a rotating RHM hinge (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) was used and in three patients, Genesis II prosthesis (Genesis II, Smith & Nephew, Memphis, TN) was implanted, whereas in seven further patients, a constrained condylar CCK (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) was used.

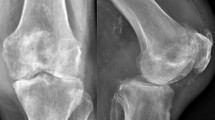

At the time of the second stage of the revision, we observed neither further bone loss nor patellar tendon shortening in any case. The mean flexion achieved after the second stage of the revision was 120°, ranging from 97° to 130°. The mean Hospital for Special Surgery score was 84. At 1 year after surgery, none of the knees showed any evidence of recurrence of the infection. Flexion after the revision was increased over the prerevision situation in all cases. In 1 case, there was a residual flexion contracture (10°) (Figs. 12 and 13).

Discussion

The infected total knee replacement is a difficult challenge for the orthopedic surgeon. The soft tissues and bone are often necrotic; there is loss of bone; and exposure of the knee is difficult because of scar tissue. The golden standard in the treatment of an infected total knee arthroplasty is a two-stage protocol using an interval antibiotic spacer and intravenous administering of antibiotics for a period of 6 weeks [14].

Articulating spacers have been proposed as a way of preserving range of motion, bone stock, and length of soft tissues in two-stage revision total knee arthroplasty [2, 3, 8]. Premolded spacers have been described as being effective [2, 9, 10]. The problem with premolded spacers is that they are expensive and many times do not fit an individual patient. For that reason, we have considered using the method of molding an articulating spacer as described by Villanueva et al. [1]. However, there is no agreement in the literature about the best fixed or mobile spacer to be used. [4–6, 8, 17–20]

This technique allows the surgeon to mold a spacer on single case anatomy. The advantage is perfect matching with residual bone (no further bone loss) and gap filling, so postoperative motion is preserved as collateral ligaments and patellar tendon length are maintained.

In this prospective study, although we have followed-up our patients for only 1 year after surgery, we have noted no recurrence of infection and good range of motion. We will continue to follow-up these patients over the next years; but for the present, we feel that this is a viable option for the patient who requires a two-stage reimplantation. However, a larger number of patients and a more prolonged follow-up are necessary to confirm the positive impressions obtained in this study.

References

Villanueva M, Rios A, Pereiro J, Chana F, Fahandez-Saddi H (2006) Hand-made articulating spacers for infected total knee arthroplasty: a technical note. Acta Orthop 77 (2):329–332

Patel VP, Walsh M, Sehgal B, Preston C, DeWal H, Di Cesare PE (2007) Factors associated with prolonged wound drainage after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007 89 (1):33–38

Soohoo NF, Zingmond DS, Lieberman JR, Ko CY (2006) Optimal timeframe for reporting short-term complication rates after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 21 (5):705–711

Goldman RT, Scuderi GR, Insall JN (1996) 2-stage reimplantation for infected total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res (331):118–124

Wilde AH, Ruth JT (1988) Two-stage reimplantation in infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res (236):23–35

Teeny SM (1990) Treatment of infected total knee arthroplasty. Irrigation and debridement versus two-stage reimplantation. J Arthroplasty 5:35–39

Borden LS, Gearen PF (1987) Infected total knee arthroplasty. A protocol for management. J Arthroplasty 2:27–36

Fehring TK et al (2000) Articulating versus static spacers in revision total knee arthroplasty for sepsis. The Ranawat Award. Clin Orthop Relat Res (380):9–16

Emerson RH Jr et al (2002) Comparison of a static with a mobile spacer in total knee infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res (404):132–138

Hofmann AA et al (1995) Treatment of infected total knee arthroplasty using an articulating spacer. Clin Orthop Relat Res (321):45–54

Haddad FS et al (2000) The PROSTALAC functional spacer in two-stage revision for infected knee replacements. Prosthesis of antibiotic-loaded acrylic cement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 82:807–812

Meek RM (2003) Patient satisfaction and functional status after treatment of infection at the site of a total knee arthroplasty with use of the PROSTALAC articulating spacer. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85-A:1888–1892

Dixon P, Parish EN, Cross MJ (2004) Arthroscopic debridement in the treatment of the infected total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 86:39–42

Ha CW (2006) A technique for intraoperative construction of antibiotic spacers. Clin Orthop Relat Res 445:204–209

Goldstein WM, Kopplin M, Wall R, Berland K (2001) Temporary articulating methylmethacrylate antibiotic spacer (TAMMAS). A new method of intraoperative manufacturing of a custom articulating spacer. J Bone Joint Surg Am 83-A(Suppl 2 Pt 2):92–97

Windsor RE, Insall JN et al (1990) Two-stage reimplantation for the salvage of total knee arthroplasty complicated by infection. Further follow-up and refinement of indications. J Bone Joint Surg Am 72:272–278

McPherson EJ, Lewonowski K, Dorr LD (1995) Use of an articulated PMMA spacer in the infected TKA. J Arthroplasty 10:87–89

Duncan CP, Beauchamp CP, Masri B et al (1992) The antibiotic loaded joint replacement system: A novel approach to the management of the infected knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 74-B(Suppl III):296

Booth RE Jr, Lotke PA Jr (1989) The results of spacer block technique in revision of infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res (248):57–60

Calton TF, Fehring TK, Griffin WL (1997) Bone loss associated with the use of spacer blocks in infected TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res (345):148–154

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pascale, V., Pascale, W. Custom-made Articulating Spacer in Two-stage Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. An Early Follow-up of 14 Cases of at Least 1 Year After Surgery. HSS Jrnl 3, 159–163 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11420-007-9048-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11420-007-9048-1