Abstract

The changes in the prevalence of designer drugs and their legal status in Japan were investigated on the basis of the analyses of 686 different products containing synthetic cannabinoids and/or cathinone derivatives obtained from 2009 to February 2012. In the early stages of distribution of herbal-type products containing synthetic cannabinoids, cyclohexylphenols and naphthoylindoles were mostly found in the products. In November 2009, however, cannabicyclohexanol, CP-47,497 and JWH-018 were controlled as “designated substances” under the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law in Japan, and the cyclohexylphenols have since disappeared from the illegal drug market and been replaced by various analogs of the naphthoylindoles, phenylacetylindoles and benzoylindoles. These compounds, which have high affinities for the cannabinoid CB1 receptor, have become very popular, and the number of emergency hospitalizations associated with their use has dramatically increased from 2011. Other synthetic compounds with different structures and pharmacological effects, such as cathinone derivatives, have been detected together with the synthetic cannabinoids in herbal-type products since 2011. Moreover, many new types of synthetic cannabinoids, different from the four typical structures described, have also begun to appear since 2011. In addition to the synthetic cannabinoids, liquid or powdery-type products containing cathinone derivatives have been widely distributed recently. In 2009, the most popular cathinone derivative was 4-methylmethcathinone. After this compound was controlled as a designated substance in November 2009, cathinone derivatives, which have a pyrrolidine structure at the nitrogen atom and a 3,4-methylenedioxy structure, or analogs of 4-methylmethcathinone, became popular. In the present analysis, tryptamines were also detected in 31 % of the products containing cathinone derivatives. Local anesthetics such as procaine, lidocaine, benzocaine and dimethocaine were also frequently detected. In total, we identified at least 35 synthetic cannabinoids and 22 cathinone derivatives during this survey.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, many analogs of narcotics have been widely distributed as easily available psychotropic substances and have become a serious problem in Japan. To counter the spread of these designer drugs, the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law in Japan was amended in 2006 to establish a new category, “designated substances,” to more strictly control these drugs. Since 31 compounds and 1 plant were first controlled as designated substances in April 2007, 77 substances (13 tryptamines, 17 phenethylamines, 11 cathinone derivatives, 4 piperazines, 23 synthetic cannabinoids, 6 alkyl nitrites and 3 other compounds) and 1 plant (Salvia divinorum) have been listed in this category (data from July 2012). However, simultaneously with the control of these designer drugs, new analogs of the controlled substances began to appear one after another on the illegal drug market, and the identification and control of these compounds are rapidly devolving into a cat and mouse game. In particular, the recent spread of products containing various analogs of synthetic cannabinoids and/or cathinone derivatives has been a matter of great concern in Japan [1].

Before 2007, the major compounds distributed in the illegal drug market were tryptamines, phenethylamines and piperazines [1–11]. Alkyl nitrites, such as isobutyl nitrite and isopentyl nitrite, were also widely distributed [9, 12]. After they were listed as narcotics or designated substances in 2007, these compounds, especially the tryptamines, quickly disappeared from the market. In their place, various analogs of cathinone derivatives in the forms of liquid or powdery products, called “legal drugs” or “aroma liquids,” have been widely distributed, as well as different phenethylamines and piperazines [1, 2, 13–17]. Since 2008, herbal-type products containing various synthetic cannabinoids have appeared in Japan under names such as “legal herbs” and “incense” [1, 2, 18, 19]. These synthetic cannabinoids had been originally synthesized by medicinal chemistry during the development of new medicines affecting the central nervous system. They have been reported to have high affinity actions on cannabinoid CB1 and/or CB2 receptors [20, 21]. At present, the synthetic cannabinoids and cathinone derivatives are the most popular designer drugs sold on the illegal drug market in Japan [1, 2, 22–34]. Among the 27 designated substances that have been controlled since 2011, 89 % of the compounds were either synthetic cannabinoids (18 compounds) or cathinone derivatives (6 compounds).

In this study, we analyzed two types of products, the herbal-type products sold as “legal herbs” or “incense” and the liquid/powdery-type products sold as “legal drugs” or “aroma liquids” on the Internet during the last 3 years, and the changes in the prevalence of these designer drugs and their legal status in Japan were investigated.

Materials and methods

Materials

Five hundred sixty-two different herbal-type products, sold as “legal herbs” or “incense” for their expected cannabis-like effects in Japan, were purchased via the Internet from January 2009 to February 2012. Most of them contained mixtures of dried cutting leaves, although some of the products contained powders or resin-like solids without herbal mixtures. In addition to herbal-type products, 124 different liquid or powdery-type products, sold as “legal drugs” or “aroma liquids,” were also purchased via the Internet from September 2009 to February 2012.

Chemicals and reagents

Most of the authentic synthetic cannabinoids and cathinone derivatives were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA), LGC standards (Luckenwalde, Germany) and Sigma-Aldrich Co., LLC (St. Louis, MO, USA). Other authentic compounds were isolated from products and identified as described in our previous studies [18, 19, 27, 31]. All other common chemicals and solvents were of analytical reagent grade or HPLC grade.

Sample extraction procedures

The products consisting of a mixture of dried cutting leaves (10 mg) were crushed into powder and extracted with 1 ml of methanol under ultrasonication for 10 min. The powdery product (2 mg) or liquid product (20 μl) was dissolved with 1 ml of methanol. After centrifugation (5 min at 3,000 rpm), the supernatant solution was passed through a centrifugal filter (Millex LG filter, 0.45-μm; Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). When necessary, the solution was diluted with methanol to a suitable concentration before instrumental analyses.

Instrumental analyses

The methanol extracts were analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry in the electron ionization mode (GC-EI-MS) and by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI-MS). The identification of unknown compounds was mainly carried out by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis and by direct analysis in real time (DART) ion source coupled to a time-of-flight mass spectrometer (TOF–MS). The analytical conditions were described in detail in our previous report [33].

Results and discussion

Survey of herbal-type products sold as “legal herbs” or “incense”

In the last 3 years, synthetic cannabinoids described as “legal highs” or “synthetic marijuana” have been the most popular non-controlled designer drugs in the world. In July 2012, 23 synthetic cannabinoids were controlled as designated substances in Japan, as shown in Fig. 1. Table 1 shows the summary of our survey of 562 different herbal-type products purchased via the Internet under the descriptions “legal herbs” or “incense” from January 2009 to February 2012. Most of these products were in the form of dried cutting leaves (522 products), although some of them were in the forms of powders (35 products) or resin-like solids (5 products) without herbal mixtures, as shown in Table 1. The synthetic cannabinoids were detected in 556 of the 562 products. The other six products, which were purchased in 2009 and 2010, contained no synthetic compounds, and one of them contained some active constituents derived from typical psychotropic cacti and plants. Typical constituents of marijuana (Cannabis sativa), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and cannabinol, were detected together with the synthetic cannabinoids in an herbal product in 2009. Before 2011, there was no product that contained other types of synthetic compounds except caffeine. However, cathinone derivatives [e.g., 1-(4-methylphenyl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)propan-1-one (4-MePPP), 4-methylethcathinone, 1-phenyl-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)pentan-1-one (α-PVP), ethcathinone, N-ethylbuphedrone (NEB), 1-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)pentan-1-one (MDPV) and pyrovalerone; the structures are shown in Table 2], tryptamines [e.g., α-methyltryptamine (AMT), which has been controlled as a narcotic in Japan since 2005; N,N-diallyl-5-methoxytryptamine (5-MeO-DALT), which has been controlled as a designated substance since 2007; and N,N-diethyl-4-hydroxytryptamine (4-OH-DET)], and local anesthetics (e.g., lidocaine, procaine and dimethocaine) have been detected together with the synthetic cannabinoids from 2011. Methoxetamine (a derivative of ketamine), 2-diphenylmethylpyrrolidine and some phenethylamines were also found in the products in 2011. Overall, the average number of synthetic compounds detected per product was 2.6 over the 3 years. In 2009 and 2010, most products contained only one or two synthetic compounds, except caffeine and a trans-form of cannabicyclohexanol, which was mostly detected together with cannabicyclohexanol [25]. However, the numbers of the synthetic compounds detected in the products dramatically increased in 2011, with one of the products containing as many as ten synthetic compounds.

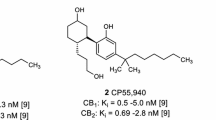

The synthetic cannabinoids detected in Japan were divided mainly into four groups, cyclohexylphenols, naphthoylindoles, phenylacetylindoles and benzoylindoles, as shown in Fig. 1. The changes in the rates of these four types and other types of synthetic cannabinoids, detected in the herbal-type products purchased from January 2009 to February 2012, are shown in Fig. 2. In the earliest stage, only cyclohexylphenols and naphthoylindoles were found in the products. However, following the control of cannabicyclohexanol, CP-47,497 and JWH-018 in November 2009, the cyclohexylphenols disappeared from the illegal drug market, and various analogs of naphthoylindoles, phenylacetylindoles and benzoylindoles were widely distributed. Furthermore, in 2011, various compounds began to appear that had structures different from those of the four groups described above.

Figure 3 shows the changes in the detailed prevalence of each synthetic cannabinoid and their legal status on the basis of our survey of the 562 herbal-type products sold as “legal herbs” or “incense” during the last 3 years. We identified at least 35 synthetic cannabinoids in the products during this survey. As described above, cannabicyclohexanol, CP-47,497 and JWH-018 were the most frequently detected until November 2009. After these three compounds were listed as designated substances in that month, the synthetic cannabinoids in herbal products were quickly replaced by JWH-073 and JWH-250. After the prohibition of these two compounds in September 2010, various analogs, such as JWH-081, JWH-122 and JWH-210, began to be widely distributed. At that time, the analogs, structures of which featured the introduction of a halogen substituent, appeared on the drug market; these included JWH-203, AM-2201 and AM-694. Compounds having higher affinities to the cannabinoid CB1 receptors, such as JWH-122 (the K i value for binding the CB1 receptor was 0.69 nM) [35], JWH-210 (0.46 nM) [21] and AM-694 (0.08 nM) [36], have also become popular, and the number of emergency hospitalizations associated with the products containing these synthetic cannabinoids has increased since 2011.

Changes in the prevalence of synthetic cannabinoids and their legal status on the basis of our survey of 562 herbal-type products sold as “legal herbs” or “incense” on the Internet between January 2009 and February 2012. The horizontal axis shows the number of products.  : products purchased from January 2009 to November 2009;

: products purchased from January 2009 to November 2009;  : from November 2009 to September 2010;

: from November 2009 to September 2010;  : from September 2010 to May 2011;

: from September 2010 to May 2011;  : from May 2011 to October 2011;

: from May 2011 to October 2011;  : from October 2011 to February 2012

: from October 2011 to February 2012

In 2011, a total of 11 synthetic cannabinoids were added to the designated substance list in May and October. However, new synthetic cannabinoids were simultaneously emerging throughout Japan. After the six synthetic cannabinoids were listed in October 2011 (Fig. 3), new compounds, such as APICA and APINACA, appeared on the illegal drug market [31]. Many of the synthetic cannabinoids have a 3-carbonyl indole moiety, while these compounds belong to a new type of synthetic cannabinoids having each adamantylcarboxamide structure. APINACA additionally has an indazole group in place of an indole group. The adamantyl groups are also found in the structures of AB-001 and AM-1248, which have been distributed since 2011 [31, 33]. AM-1220 and AM-2233 were the most popular synthetic cannabinoids together with APICA and APINACA at the beginning of 2012. AM-1220 and AM-2233 have a (1-piperidin-2-yl)methyl structure at the nitrogen atom in an indole structure [31]. AM-1248, AM-1241 and cannabipiperidiethanone also have this structure and were also found in some products. Moreover, CB-13, JWH-030 and JWH-307 do not have an indole group and are newly found compounds [31, 33]. Although the data are not shown in this study, we also identified UR-144 and XLR-11 (having a tetramethylcyclopropyl structure), [1-(5-fluoropentyl)-1H-indol-3-yl](pyridin-3-yl)methanone and URB754 (which was originally reported to be a potent inhibitor of monoacylglycerol lipase [37]) as synthetic cannabinoids having novel structures distinct from those described above in the second quarter of 2012 [33]. As shown in Fig. 2, after October 2011, about 50 % of the synthetic cannabinoids consisted of new types that do not belong to the typical four types of structures mentioned above. Seven synthetic cannabinoids, APICA, APINACA, AM-1220, AM-2233, CB-13, JWH-022 and cannabipiperidiethanone, were controlled as designated substances in July 2012. Additionally, cannabicyclohexanol and JWH-018 will be changed from designated substances to narcotics in August 2012 in Japan.

Survey of liquid or powdery-type products sold as “legal drugs” or “aroma liquids”

In addition to synthetic cannabinoids, the products containing cathinone derivatives have also been widely distributed throughout the world, often under the names “legal highs” or “bath salts.” In Japan, cathinone, methcathinone and methylone are controlled as narcotics, and pyrovalerone and amfepramone are controlled as psychotropics under the Narcotics and Psychotropics Control Law. As of July 2012, 11 cathinone derivatives had been controlled as designated substances in Japan (Table 2). Two of these derivatives, 4-methylmethcathinone and MDPV, will be changed from designated substances to narcotics in August 2012, together with cannabicyclohexanol and JWH-018.

Table 3 shows the summary of our survey of 124 different liquid or powdery-type products (111 liquid and 13 powdery-type products) purchased via the Internet from September 2009 to February 2012, all of which were sold as “legal drugs” or “aroma liquids.” We detected cathinone derivatives in all 124 products. These products also contained various kinds of synthetic compounds having different pharmacological effects. A few powdery products contained both synthetic cannabinoids and cathinone derivatives, although synthetic cannabinoids have never been detected in liquid products. The failure to detect synthetic cannabinoids in these products may be due to their high hydrophobicities, which would prevent their dissolution in liquids. Tryptamines such as AMT, 5-MeO-DALT and 4-OH-DET were detected in 31 % of the products together with cathinone derivatives. In particular, in 2011, 32 of the 75 products contained tryptamines. In addition to tryptamines, local anesthetics such as procaine, lidocaine, benzocaine and dimethocaine were frequently detected in the liquid or powdery-type products from 2011. Caffeine, methoxetamine, methiopropamine (an analog of methamphetamine), 2-diphenylmethylpyrrolidine and other compounds have also been found together with the cathinone derivatives in these products. Since 2010, the average number of synthetic compounds detected in these products has risen steadily from 2.0 to 3.1, as shown in Table 3. In this survey, 48 of the 124 products contained only one compound, while there was a liquid product containing as many as eight synthetic compounds (data not shown).

Figure 4 shows the changes in the prevalence of cathinone derivatives and their legal status on the basis of our survey of the 124 liquid or powdery-type products sold as “legal drugs” or “aroma liquids” during the last 3 years. We have identified 22 cathinone derivatives [including isopentedrone: 1-(methylamino)-1-phenylpentan-2-one] in this survey. Table 2 shows non-controlled and controlled cathinone derivatives detected in this survey as well as those detected in our other studies [11, 33]. In 2009, the most popular cathinone derivative was 4-methylmethcathinone (mephedrone). After this compound was listed as a designated substance in September 2010, the cathinone derivative in the products was replaced by its analogs, 4-methoxymethcathinone (methedrone) and 4-methylethcathinone, in addition to 3- and 4-fluoromethcathinone (flephedrone). Following the control of these compounds in 2011, cathinone derivatives, which have a pyrrolidine structure at the nitrogen atom [such as α-PVP and 1-phenyl-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)butan-1-one (α-PBP)], a 3,4-methylenedioxy structure (such as pentylone), and analogs of 4-methylmethcathinone (such as 3,4-dimethylmethcathinone) have become popular. Methylone (narcotic), pyrovalerone (psychotropic), ethcathinone and MDPV (designated substances), which were controlled before September 2009, were also detected in this survey.

Changes in the prevalence of cathinone derivatives and their legal status on the basis of our survey of 124 liquid or powdery-type products sold as “legal drugs” or “aroma liquid” on the Internet between September 2009 and February 2012. The horizontal axis shows the number of products.  : products purchased from September 2009 to November 2009;

: products purchased from September 2009 to November 2009;  : from November 2009 to September 2010,

: from November 2009 to September 2010,  : from September 2010 to May 2011;

: from September 2010 to May 2011;  : from May 2011 to October 2011;

: from May 2011 to October 2011;  : from October 2011 to February 2012; 4-MePPP 1-(4-methylphenyl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)propan-1-one, MDPBP 1-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)butan-1-one, α-PVP 1-phenyl-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)pentan-1-one, α-PBP 1-phenyl-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)butan-1-one, MDPV 1-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)pentan-1-one

: from October 2011 to February 2012; 4-MePPP 1-(4-methylphenyl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)propan-1-one, MDPBP 1-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)butan-1-one, α-PVP 1-phenyl-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)pentan-1-one, α-PBP 1-phenyl-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)butan-1-one, MDPV 1-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)pentan-1-one

Conclusions

After the introduction of the category “designated substances” into the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law in 2007, the conventional designer drugs (such as tryptamines and piperazines) disappeared from the illegal drug market in Japan, and the active entries of various synthetic cannabinoids dramatically changed the situation in the market. These compounds were originally invented in medicinal chemistry. Until now, their numerous analogs have been synthesized during the development of new medicines affecting the central nervous system, and only some of these analogs have appeared as designer drugs in the illegal drug market. Therefore, we are sure that other analogs that have strong activities will appear one after another. In fact, the actual composition in terms of synthetic additives in the products is dynamically changing and rapidly responding to the newly implemented control measures. This fact makes it difficult to control these compounds using the existing systems. The number of emergency hospitalizations associated with synthetic cannabinoid use has increased dramatically from 2011. There have been some fatal cases, which are possibly related to the smoking of these products. Another group of designer drugs extensively appearing on the illegal drug market in Japan is cathinone derivatives; we have detected as many as 22 kinds of this group in this survey. To avoid health problems caused by these new designer drugs, we have to continuously monitor the distribution of these dubious products.

References

Kikura-Hanajiri R, Uchiyama N, Kawamura M, Ogata J, Goda Y (2012) Prevalence of new designer drugs and their legal status in Japan (in Japanese with English abstract). Yakugaku Zasshi (in press)

Kikura-Hanajiri R, Uchiyama N, Goda Y (2011) Survey of current trends in the abuse of psychotropic substances and plants in Japan. Legal Med 13:109–115

Nagashima M, Seto T, Takahashi M, Miyake H, Yasuda I (2004) Screening method of the chemical illegal drugs by HPLC-PDA (in Japanese). Ann Rep Tokyo Metrop Inst Public Health 55:67–71

Kikura-Hanajiri R, Hayashi M, Saisho K, Goda Y (2005) Simultaneous determination of 19 hallucinogenic tryptamines/β-calbolines and phenethylamines using GC–MS and LC-ESI–MS. J Chromatogr B 825:29–37

Seto T, Takahashi M, Nagashima M, Suzuki J, Yasuda I (2005) The identifications and the aspects of the commercially available uncontrolled drugs purchased between Apr. 2003 and Mar. 2004 (in Japanese). Ann Rep Tokyo Metrop Inst Public Health 56:75–80

Matsumoto T, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Kamakura H, Kawamura N, Goda Y (2006) Identification of N-Methyl-4-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)butan-2-amine, distributed as MBDB. J Health Sci 52:805–810

Takahashi M, Suzuki J, Nagashima M, Seto T, Yasuda I (2007) Newly detected compounds in uncontrolled drugs purchased in Tokyo between April 2006 and March 2007 (in Japanese). Ann Rep Tokyo Metrop Inst Public Health 58:83–87

Kikura-Hanajiri R, Kawamura M, Saisho K, Kodama Y, Goda Y (2007) The disposition into hair of new designer drugs; methylone, MBDB and methcathinone. J Chromatogr B 855:121–126

Kikura-Hanajiri R, Kawamura M, Uchiyama N, Ogata J, Kamakura H, Saisho K, Goda Y (2008) Analytical data of designated substances (Shitei-Yakubutsu) controlled by the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law in Japan, part I: GC–MS and LC–MS (in Japanese with English abstract). Yakugaku Zasshi 128:971–979

Uchiyama N, Kawamura M, Kamakura H, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Goda Y (2008) Analytical data of designated substances (Shitei-Yakubutsu) controlled by the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law in Japan, part II: color test and TLC (in Japanese with English abstract). Yakugaku Zasshi 128:981–987

Uchiyama N, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Kawahara N, Goda Y (2008) Analysis of designer drugs detected in the products purchased in fiscal year 2006 (in Japanese with English abstract). Yakugaku Zasshi 128:1499–1505

Suzuki J, Takahashi M, Seto T, Nagashima M, Okumoto C, Yasuda I (2006) Qualitative method of nitrite inhalants (in Japanese). Ann Rep Tokyo Metrop Inst Public Health 57:115–120

Nagashima M, Seto T, Takahashi M, Suzuki J, Mori K, Ogino S (2008) Analyses of uncontrolled drugs purchased from April 2007 to March 2008 and newly found compounds (in Japanese). Ann Rep Tokyo Metrop Inst Public Health 59:71–77

Uchiyama N, Miyazawa N, Kawamura M, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Goda Y (2010) Analysis of newly distributed designer drugs detected in the products purchased in fiscal year 2008 (in Japanese with English abstract). Yakugaku Zasshi 130:263–270

Nagashima M, Takahashi M, Suzuki J, Seto T, Mori K, Ogino S (2009) Analyses of uncontrolled drugs purchased Apr. 2008–Mar. 2009 (in Japanese). Ann Rep Tokyo Metrop Inst Public Health 60:81–84

Kikura-Hanajiri R, Kawamura M, Miyajima A, Sunouchi M, Goda Y (2010) Determination of a new designer drug, N-hydroxy-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine and its metabolites in rats using ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Forensic Sci Int 198:62–69

Suzuki J, Moriyasu T, Nagashima M, Kanai C, Shimizu M, Hamano T, Nagayama T (2010) Analysis of uncontrolled drugs purchased in fiscal year 2009 (in Japanese). Ann Rep Tokyo Metrop Inst Public Health 61:163–172

Uchiyama N, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Kawahara N, Goda Y (2009) Identification of a cannabimimetic indole as a designer drug in a herbal product. Forensic Toxicol 27:61–66

Uchiyama N, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Ogata J, Goda Y (2010) Chemical analysis of synthetic cannabinoids as designer drugs in herbal products. Forensic Sci Int 198:31–38

Compton DR, Rice KC, De Costa BR, Razdan RK, Melvin LS, Johnson MR, Martin BR (1993) Cannabinoid structure-activity relationships: correlation of receptor binding and in vivo activities. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 265:218–226

Huffman JW (2009) Cannabimimetic indoles, pyrroles, and indenes: structure-activity relationships and receptor interactions. In: Reggio PH (ed) The cannabinoid receptors. Humana Press, New York, pp 49–94

Uchiyama N, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Ogata J, Goda Y (2010) Chemical analysis of synthetic cannabinoids as designer drugs in herbal products. Forensic Sci Int 198:31–38

Nagashima M, Suzuki J, Moriyasu T, Yoshida M, Shimizu M, Hamano T, Nakae D (2011) Analysis of uncontrolled drugs purchased in the fiscal year 2010 (in Japanese). Ann Rep Tokyo Metrop Inst Public Health 62:99–105

Yoshida M, Suzuki J, Takahashi M, Moriyasu T, Nakajima J, Kanai C, Nagashima M, Seto T, Shimizu M, Hamano T, Nakae D (2011) Investigations of designated substances detected from April 2010 to March 2011 (in Japanese). Ann Rep Tokyo Metrop Inst Public Health 62:107–114

Uchiyama N, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Shoda T, Fukuhara K, Goda Y (2011) Isomeric analysis of synthetic cannabinoids detected as designer drugs (in Japanese with English abstract). Yakugaku Zasshi 131:1141–1147

Uchiyama N, Kawamura M, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Goda Y (2011) Identification and quantitative analyses of two cannabimimetic phenylacetylindoles, JWH-251 and JWH-250, and four cannabimimetic naphthoylindoles, JWH-081, JWH-015, JWH-200 and JWH-073, as designer drugs in illegal products. Forensic Toxicol 29:25–37

Uchiyama N, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Goda Y (2011) Identification of a novel cannabimimetic phenylacetylindole, cannabipiperidiethanone, as a designer drug in a herbal product and its affinity for cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Chem Pharm Bull 59:1203–1205

Nakajima J, Takahashi M, Seto T, Suzuki J (2011) Identification and quantitation of cannabimimetic compound JWH-250 as an adulterant in products obtained via the Internet. Forensic Toxicol 29:51–55

Nakajima J, Takahashi M, Seto T, Kanai C, Suzuki J, Yoshida M, Hamano T (2011) Identification and quantitation of two benzoylindoles AM-694 and (4-methoxyphenyl)(1-pentyl-1H-indol-3-yl)methanone, and three cannabimimetic naphthoylindoles JWH-210, JWH-122, and JWH-019 as adulterants in illegal products obtained via the Internet. Forensic Toxicol 29:95–110

Nakajima J, Takahashi M, Nonaka R, Seto T, Suzuki J, Yoshida M, Kanai C, Hamano T (2011) Identification and quantitation of a benzoylindole (2-methoxyphenyl)(1-pentyl-1H-indol-3-yl)methanone and a naphthoylindole 1-(5-fluoropentyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-(naphthalene-1-yl)methanone (AM-2201) found in illegal products obtained via the Internet and their cannabimimetic effects evaluated by in vitro [35S]GTPγS binding assays. Forensic Toxicol 29:132–141

Uchiyama N, Kawamura M, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Goda Y (2012) Identification of two new-type synthetic cannabinoids, N-(1-adamantyl)-1-pentyl-1H-indole-3-carboxamide (APICA) and N-(1-adamantyl)-1-pentyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide (APINACA), and detection of five synthetic cannabinoids, AM-1220, AM-2233, AM-1241, CB-13 (CRA-13) and AM-1248, as designer drugs in illegal products. Forensic Toxicol 30:114–125

Nakajima J, Takahashi M, Seto T, Yoshida M, Kanai C, Suzuki J, Hamano T (2012) Identification and quantitation of two new naphthoylindole drugs-of-abuse, (1-(5-hydroxypentyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)(naphthalen-1-yl)methanone (AM-2202) and (1-(4-pentenyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)(naphthalen-1-yl)methanone, with other synthetic cannabinoids in unregulated “herbal” products circulated in the Tokyo area. Forensic Toxicol 30:33–44

Uchiyama N, Matsuda S, Kawamura M, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Goda Y (2012) URB-754: a new class of designer drug and 12 synthetic cannabinoids detected in illegal products. Forensic Sci Int, 2012 Oct 9. pii:S0379-0738(12)00434-3. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.08.047

Takahashi K, Uchiyama N, Fukiwake T, Hasegawa T, Saijou M, Motoki Y, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Goda Y (2012) Identification and quantitation of a cannabimimetic indole JWH-213 as a designer drug in an herbal product. Forensic Toxicol (in press)

Huffman JW, Mabon R, Wu MJ, Lu J, Hart R, Hurst DP, Reggio PH, Wiley JL, Martin BR (2003) 3-Indolyl-1-naphthylmethanes: new cannabimimetic indoles provide evidence for aromatic stacking interactions with the CB(1) cannabinoid receptor. Bioorg Med Chem 11:539–549

Makriyannis A, Deng H (2001) Cannabimimetic indole derivatives. WO patent 200128557

Makara JK, Mor M, Fegley D, Szabó SI, Kathuria S, Astarita G, Duranti A, Tontini A, Tarzia G, Rivara S, Freund TF, Piomelli D (2005) Selective inhibition of 2-AG hydrolysis enhances endocannabinoid signaling in hippocampus. Nat Neurosci 8:1139–1141

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Health Sciences Research Grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is for the special issue TIAFT2012 edited by Osamu Suzuki.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kikura-Hanajiri, R., Uchiyama, N., Kawamura, M. et al. Changes in the prevalence of synthetic cannabinoids and cathinone derivatives in Japan until early 2012. Forensic Toxicol 31, 44–53 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11419-012-0165-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11419-012-0165-2