Abstract

We applied the “informed citizen” thesis to public confidence in the police in the Philippines—a topic that has surprisingly received little research attention. We analyzed four waves of survey data from the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS), and we applied propensity score matching (PSM) method and regression models to the data. We operationalized education, interest in politics, and Internet usage as indicators of an informed citizen. We tested whether they are predictive of confidence in the police. Confidence in the Philippine police has gradually improved from 2002 to 2014. Regression analysis found that citizens with more education and more Internet usage displayed lower levels of confidence in the Philippine police. We also found that an interaction effect between education and political interests, with education having a stronger connection to confidence in the police among those with greater political interests. Our findings support the informed citizen thesis and shed new light on the study of confidence in the Philippine police.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Confidence in the police is a growing sub-area study of criminology related to police legitimacy, procedural justice, and willingness to comply with the law (Cao et al. 1996; Correia et al. 1996; Dai et al. 2019; Hu et al. 2015; Li et al. 2016; Marien and Hooghe 2011; Manning 2010; Mazerolle et al. 2013; Payne and Gainey 2007; Reisig and Giacomazzi 1998; Tyler 1990, 2002; Weitzer and Tuch 2004; Wu and Cao 2018). Researchers have identified determinants of confidence in the police across the world (Cao and Dai 2006; Cao et al. 2012; Hu et al. 2015; Jang et al. 2010; Lai et al. 2010; Stack and Cao 1998; Sun et al. 2012, 2016, 2018; Wu 2014). However, the informed citizen thesis—the argument that well-educated and informed citizens would be critical against authorities (Hagen 1997; Mihailidis and Thevenin 2013; Milner 2002)—has not been adequately tested in the criminological literature.

In this study, we selected the Republic of the Philippines (hereafter the Philippines) as a focal case to examine the informed citizen thesis on confidence in the police. The Philippines is selected primarily for three reasons. First, the Philippines is an emerging new democracy, and the public confidence in the police has understudied while similar studies have been conducted in other newly democratic Asian societies (Kim 2010; Sun et al. 2016). Second, it is a country that is uniquely different from its surrounding nations. It is not a part of the Confucian circle nor a part of Muslim nations. If anything, it is a predominantly Christian nation with multi-languages, multi-religious, and multi-ethnic groups. Third, the recent political campaigns against crimes and police corruption in the Philippines have raised an eyebrow around the world. As a result, there has been a rising curiosity about policing in this country (Cao and Dai 2006; Inoguchi 2017; Lasco 2018), and we hope to add more evidence into this field with the present study.

Specifically, the Philippines consists of thousands of islands. There is no dominant ethnic group, and the country has 182 living languages. Formerly a colony of the USA and Spain (Japan also briefly occupied it), its colonial past has left a highly diverse cultural heritage: it is a predominantly Christian nation but has a strong Muslim minority. Its southern neighbors—Malaysia and Indonesia—are Muslim societies. To its north and east, the Philippines shares the South China Sea with Vietnam, Mainland China, and Taiwan, but culturally, it has never been a part of the “Confucian circle,” which makes it a deviant case of the “Asian values” (Inoguchi 2017). It established one of the earliest republics in Asia, although its existence was short (1899–1901), and the nation’s transition to democracy was relatively more chaotic than those happening during the same period in South Korea and Taiwan (Cao and Dai 2006). Inequality and corruption have been severe for a long time, which have generated negative impacts on social governance and political trust (Azfar and Gurgur 2008).

Police corruption in the Philippines has been pervasive and tolerated both during authoritarian regimes and under democratic governments (France-Presse 2017; Hapal and Jensen 2017; Maxwell 2019; SCMP 2017), which could hurt people’s confidence in the police. In more recent years, President Rodrigo Duterte and his government have initiated intensive campaigns against corruption and drugs, yet his populist approach is controversial (Curato 2017; Maxwell 2019). Considering the Philippines’ historical heritage, cultural diversity, and political conditions, we believe focusing on this country could further enhance our understanding of confidence in the police in a transitional society. In this study, we focus on public confidence in the police and pay attention to the informed citizen thesis (Delli Carpini 2000; Hagen 1997; Mihailidis and Thevenin 2013; Nisbet et al. 2012; Schudson 1998; Schutz 1976). We used four waves (2002–2014) of survey data collected by the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS) to test the applicability of the thesis in the Filipino context.

Confidence in the Police: Conceptualization

“Confidence in the police represents generalized support for the police as an institution” rather than particular incumbents (Cao 2015, p. 244). Besides, confidence in the police is often regarded as an embodiment of democratic policing (Cao and Dai 2006; Lai et al. 2010; Manning 2010), as the potential paramount performance indicator for the police (Ren et al. 2005), and as an indicator for police legitimacy (Cao and Graham 2019). Trust and confidence in the police are important because they are associated with a broader concept, institutional trust (Stack and Cao 1998). Institutional trust usually refers to people’s confidence in the overall integrity and performance of legislatures, executives, judiciaries, military services, and law enforcement agencies; it has also been extended to include people’s trust in the media, religious groups, NGOs, and other social organizations (Tyler 2001). In other words, confidence in the police is a part of a larger confidence complex (Stack and Cao 1998), and findings on citizens’ confidence in the police could have implications for institutional trust in general.

Confidence in the police is intertwined with perceptions of legitimacy (Tyler 1990, 2002; Wu and Cao 2018), sometimes measured by subjective legitimacy (Ren et al. 2005; Tyler 2002) or audience legitimacy (Bottoms and Tankebe 2012; Cao and Graham 2019). This intertwined relation between confidence in the police and institutional legitimacy, in general, is an important theme in criminology, sociology, and political science (Cao et al. 1996; Manning 2010; Payne and Gainey 2007; Sun et al. 2018; Weitzer and Tuch 2004). Although trust and confidence can be used interchangeably, confidence is generally the preferred term than that of trust because of its comparatively narrower meaning (Cao 2015).

Public confidence in the police provides a critical foundation for the effectiveness, efficacy, and legitimacy of any government. High confidence indicates people’s willingness to comply with and accept decisions made by the police, while low confidence suggests less public participation in crime control and less voluntary cooperation with authorities (Cao et al. 1996; Correia et al. 1996; Dai et al. 2019; Mazerolle et al. 2013; Reisig and Giacomazzi 1998; Ren et al. 2005; Tyler, 1990; Wu and Cao 2018). Confidence in the police is especially crucial for any democratically elected government, and it is pivotal for any reform-minded government because no successful policy can be implemented without the strong support of the police. As the police represent state power and authority (Cao et al. 1996; Skogan and Frydl 2004; Weitzer and Tuch 2004), confidence in the police reflects broader social attitudes related to moral consensus and social cohesion (Cao 2015).

Informed Citizen Thesis: Education, Information, and Political Involvement

The thesis of the “informed citizen” (Milner 2002; Norris 1999; Schudson 1998; Schutz 1976) is a potential theoretical framework to explain confidence in the police, but it has neither been fully developed nor well tested in the criminological literature. The informed citizen thesis posits that citizens with more education, more exposure to information, and more political involvement will be, in general, more critical and judgmental of authorities. For decades, scholars from communication studies, political science, philosophy, and sociology have linked “informed citizens” with a critical mindset. Critical citizens can be expected to check the political powers, thus acting as the foundation for a robust democracy (Bennett 2002; Dalton 2015; Delli Carpini 2000; Hagen 1997; Kim 2010; Mihailidis and Thevenin 2013; Milner 2002; Schudson 1998).

Several mechanisms are posited to lead to the link between education and information and a critical mindset (Cao, Huang, and Sun 2016). First, people will become cognitively sophisticated and learn critical thinking when they are exposed to diverse information and opinions (Bennett 2002; Highton 2009). Second, those with access to education and information are usually associated with a more liberal and critical way of thinking (Andersen and Fetner 2008; Cao et al. 2016; Zhang 2018), leading to a healthy skepticism in traditional and political authorities, including the police.

The thesis has not been formally tested within criminology or in the study of confidence in the police. Education is usually treated as a control variable (Cao and Dai 2006; Cao et al. 1996; Cao et al. 2012; Cao and Stack 2005; Dai et al. 2019; Eschholz et al. 2002; Hu et al. 2015; Jang et al. 2010; Lai et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2019; Stack and Cao 1998; Sun et al. 2012; Sun et al. 2016; Wu 2014), and its effect on confidence has been mixed. Sometimes it is not statistically significant (Cao et al. 1996; Cao et al. 2012; Cao and Stack 2005; Dai et al. 2019; Jang et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2019; Ren et al. 2005; Sun et al. 2016; Wu 2014; Wu and Sun 2009). When it is significant, it is generally negative, as the informed citizen thesis would suggest (Cao and Dai 2006; Eschholz et al. 2002; Hu et al. 2015; Lai et al. 2010; Stack and Cao 1998; Sun et al. 2012). That is, the more educated people are, the less confident they are in the police. Of particular note, relying on data from the World Values Surveys collected 1995–1997, Cao and Dai (2006) found the level of confidence in the police was significantly lower in the Philippines than in South Korea and Taiwan, and the effect of education was statistically significant, consistent with the expectation of the informed citizen thesis. They reported that “better-educated people in democratic transitional societies are less confident than those less well educated” (p. 82). Other effects from the thesis, such as exposure to information and interest in politics, were not controlled for in that study. Also, the data were collected during Fidel Ramos’ presidency (1992–1998), and much has changed since then. The current study, therefore, is an extension of that study with more variables from the “informed citizen thesis.”

Other components of informed citizens, such as interest in politics or frequent use of the Internet as an information source, are infrequently tested in the literature of confidence in the police, and the variables used in these tests are inconsistent. Boda and Szabó’s (2011) qualitative analysis revealed that while exposure to “reality” crime television and tabloid media could increase fear of crime and punitive attitudes, it also had the surprising effect of increasing confidence in the police. In a quantitative study, Eschholz et al. (2002) reported that watching “reality” police programs in the USA increased confidence in the police, as did watching news. They interpreted this positive relationship as a “cultivation effect” because of the underlying pro-police messages in both. Similarly, Sun et al. (2016) found that when controlling for education, income, and gender, negative media reports on police reduced trust in the police in Taiwan, as did believe the media reports on police. Lai et al. (2010) found that interest in politics enhanced confidence in the police in both Taiwan and China; notably, their control variables included education.

Finally, based on data from the Asian Barometer Survey collected from 2006 to 2008, Wu (2014) found that education as a control variable was not significant for the Chinese sample, but it was significant for the Taiwanese sample. She reported that while the frequency of consuming domestic and international news, watching TV, and following the Internet did not relate to confidence in the police, trust in media increased trust in the police in both China and Taiwan, controlling for the effects of age, gender, marital status, and education. Villagers, who are generally considered less informed, were more trusting than urbanites.

Case: The Philippines

Since confidence in the police is deeply embedded in social and political contexts, the Philippines is an interesting case to test the informed citizen thesis. As mentioned earlier, the Philippines is a developing country that regained democracy during the third wave of democratization. Unlike advanced industrial societies and long-term democracies, the Philippine people still have vivid memories of the autocratic rule when the free expression of opinions was surprised or retaliated. Inequality in education and social stratification in the Philippines is severe, which could lead to diverging public opinions. Furthermore, the Philippine police have been notorious for corruption, and despite many years of efforts, police violence and corruption have been difficult to root out (Hapal and Jensen 2017; SCMP 2017). Therefore, it would be interesting to study public opinion in a democracy where citizens are liberated without any fear in their expression of opinions, and the public has become more demanding from their elected government. With the rise in an egalitarian, democratic culture, the public would develop a higher expectation for democratic policing (Cao and Dai 2006), and the well-educated citizens with better information and interest would lead such movement.

Since the transition from authoritarian rule to democracy in 1986, Philippine democracy has neither matured nor collapsed. Instead, it has become trapped in a gray zone where weak political institutions coexist with widespread economic disparities, governance deficits, and persistent communist or Muslim insurgencies (Arugay 2017). In 2001, President Joseph Ejercito Estrada was the first president in Asia to be impeached and resign from an executive role. President Maria Gloria Macaraeg Macapagal Arroyo was sworn into the presidency later that year. Four years later, she was elected to a full 6-year presidential term in a controversial and fraudulent election. She finished her presidency in 2010 as one of the most unpopular presidents in the Philippines’ history (Mangahas 2005).

President Benigno Aquino III’s election in 2010 was mainly based on the public’s contempt for corruption. His “Daang Matuwid” reforms improved the country’s internal credit rating and generated high economic growth rates, but his accountability campaign was selective: it punished his party’s political opponents, while his political allies remained unscathed (Arugay 2017). His rule from 2010 to 2016 failed to clean up the deep-seated problems of corruption. He hesitated to strengthen democratic institutions by promoting greater transparency through the freedom of information law. He left behind a stagnant democratic regime, one that was defective, exclusionary, and institutionally hollow. However, he remained popular until the end of his term.

The first wave of the survey data used in this study (see below for more information) covers the arrival of Macapagal-Arroyo. The last wave covers the end of Aquino’s term. Given the Philippines’ political and geographic contexts, we expected Filipinos’ views of the police would diverge significantly across waves of survey and different social statuses. Specifically, we tested the following hypotheses based on our previous discussions and research interests:

-

Hypothesis 1: Education is negatively related to confidence in the Philippine police.

-

Hypothesis 2: Internet usage is negatively related to confidence in the Philippine police.

-

Hypothesis 3: Interest in politics makes people trust the police less.

-

Hypothesis 4: Interest in politics could moderate the educational effects on confidence in the police: education’s impact would be greater for people with high-level political interests.

Data and Method

Data: Asian Barometer Survey from the Philippines, 2002–2014

We selected the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS) as our primary data source. The ABS is a comparative survey project that now covers 14 societies and territories in East and Southeast Asia. Since 2001, the ABS project has conducted four waves of surveys, focusing on Asian societies. It contains information on a wide range of questions concerning people’s views of family and gender, religion and beliefs, traditions and norms, economic growth, environments, and politics and governments. The project used stratified random sampling as its sampling technique (Asian Barometer 2018). During the sampling, the ABS team considered such variables as gender, age cohorts, and area to ensure representativeness within each nation. As a result, respondents in each nation all had an equal probability of being selected in the survey. After respondents were recruited, the survey was conducted via face-to-face interviews. The four waves of ABS surveys interviewed a total of 72,118 respondents in all 14 societies. The ABS dataset is of high quality and has a low rate of missing data.

We selected the ABS Filipino project not only for its concerns about values and opinions but also for its representativeness. The Philippines appeared in all four waves: 2002, 2005, 2010, and 2014.Footnote 1 There are 4800 observations for the country. The distribution of cases between waves of surveys is even: each wave of data contains 1200 cases. Given the survey’s period and research scope, the ABS data perfectly serve our research purpose.

Furthermore, the ABS dataset is of high quality and contains only a minimal amount of missing information. Even before the multiple imputation step, the data show high response rates on most variables. Variables like location, gender, religious affiliation, and location of residence have fewer than 0.1% missing responses. Marital status and level of education have fewer than 5% missing. The highest missing rate is for the variable “self-reported income status in quintiles,” with a missing rate of 17.10%.Footnote 2 To handle the remaining missing information, we used multiple imputation methods provided by the R package “Amelia II” (Honaker et al. 2011).Footnote 3 We generated five imputed datasets, fitted models on all of them, and pooled the estimates for interpretation. After the imputation procedure, all 4800 observations (100%) from the Philippines’ four waves of data were retained in our analysis, and all observations were complete on all variables in use.

Variables

The three main predictors of confidence in the police that we selected for testing the informed citizen thesis were education, frequency of using the Internet, and interest in politics. We operationalized education in two ways. The first measure was a dichotomous variable, measuring whether the respondent had completed university or college-level education (= 1) or not (= 0, the reference group). Table 1 contains the descriptive information of the complete data. As the table shows, 645 out of 4800 respondents reported having a university degree (13.44%). The second measure of education was a continuous measure of how many years of education the respondent had completed. We argued that using a continuous variable would yield a more accurate and detailed picture of how much influence education had on the dependent variable, confidence in the police. In the Philippines, the mandatory elementary school education lasts at least 6 years; even so, about 13% of the population has not completed elementary school, mostly older generations and rural residents.

We chose the frequency of using the Internet as the second indicator of an informed citizen (Nisbet et al. 2012). ABS respondents were asked: “How often do you use the Internet?” The options for answers were: “almost daily,” “at least once a week,” “at least once a month,” “several times a year,” “hardly ever,” and “never.” We categorized people who responded “do not understand the question” or “Not aware of the Internet” as “never”Footnote 4; those responding “cannot choose” or “decline to answer” were considered missing. Since some categories contained a very small number of responses, we collapsed the existing categories into three levels, from the least often to the most often: “no/hardly ever” (the reference group = 0), “from yearly to monthly,” and “from weekly to daily.” The third main variable was the overall level of interest in politics. We converted this into a dummy variable: people who were “very interested” in politics (= 1), and all other respondents (= 0, reference group).

In addition to the three main predictors, we fitted the models with other covariates as control variables. First, we added categorical variables for the waves of the survey, where the first ABS survey was the reference, and the other three waves were dummy variables to capture the changes over time in the overall confidence in the police. Second, we fitted the models with age (measured in years).Footnote 5 Third, we included dummy variables of gender (female = 0, male = 1) and location of residence (rural = 0, urban = 1). A few other categorical variables, such as marital status and self-reported income level, were controlled for as well. Marital status had three levels: single (reference group), married, and other situations. Self-reported income level was a five-level item, where respondents rated themselves in one of five quintiles based on their annual income. The size of the household was a continuous variable asking how many people lived in the same household as the respondent. Household size is important, as it is associated with economic and social status, living conditions, attitudes, and values on family, traditions, and Asian culture.

Religious affiliation was a final dichotomous measure. Since most Filipinos are Roman Catholic, we treated it as the reference category (= 0); all other possibilities (e.g., non-religious, Buddhist) were assigned a value of 1. As Table 1 shows, 93% of the surveyed respondents reported themselves to be Catholic; less than 7% belong to the “other” category. Please note that in the final models, marital status, income level, and size of the household were not included in the regression analysis as they were insignificant; however, we still used them in the propensity score matching step to identify comparable cases. We discuss the descriptive data in more detail in the results section.

The dependent variable was confidence in the police. The ABS project asked respondents to answer this question: “I am going to name a number of institutions [the police]. For each one, please tell me how much trust do you have in them?” The options included “none at all (= 1),” “not very much trust (= 2),” “a great deal (= 3),” and “quite a lot of trust (= 4),” making four levels.Footnote 6 This variable could be used as either a 4-level ordinal variable or a continuous variable ranging from 1 to 4 (from low to high trust). That is to say, we could use either ordered probit models or OLS regression models for this dependent variable. We tried both, and the patterns were consistent across modelsFootnote 7; for convenience, we adopted OLS regression.

Analytical Plan and Robustness Checks

We fitted the OLS regression models in the following sequence:

Model 1: All covariates + years of education + political interest (hypotheses 1, 2, and 3).

Model 2: All covariates + years of education × political interest (hypothesis 4).

Before interpreting the modeling results, we need to address reliability and robustness concerns. First, we fitted the models with various measures of education, including a dichotomous measure of “high school or above” and “less than high school,” another dichotomous measure of “university or above” and “less than university,” and our continuous measure, years of education. All three educational variables yielded similar findings in terms of the significance level and the direction, as reported in Table 3, making the results more convincing.

Second, we used the propensity score matching (PSM) method to deal with a potential selection bias related to the variable of education. Selection bias is a valid concern as education is achieved status, not an ascribed one. Individuals who complete their university/college degrees may differ from those who fail to do so, and the differences could be family backgrounds, parental socio-economic statuses, biological attributions, behavioral dispositions, exposures to various environmental factors such as neighborhoods, schools, and peers, and so on. To ensure that we were analyzing comparable populations, we adopted the nearest neighbor algorithm in PSM (Austin 2014). We tried other PSM algorithms as well, including caliper matching, interval matching, and kernel matching; we compared their estimates and found no noteworthy discrepancies. For the PSM, we matched on the conditional probability of mobility given a series of observed variables. We adopted the ignorable treatment assignment assumption (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983), whereby individuals’ assignment to treatment or control is independent of the potential outcomes if observable covariates are held constant.

As previously mentioned, among the 4800 respondents, only 645 reported a university/college degree. PSM methods could select the most comparable individuals (N = 645) from the remaining 4155 cases to compare with the university/college degree holders (N = 645). After matching, differences between people who have a university degree and those who do not could be seen as purely an educational effect, not confounded by other covariates. We held the following variables constant in our nearest neighbor PSM procedures: gender, age, marital status, religious affiliation, location of residence, size of household, and self-reported income level. The matching results appear in Table 2, along with a comparison of the complete data and the post-matching sample. As Table 2 indicates, the matched sample shows minimal differences in all variables included in the matching process. We fitted the same OLS models on the matched samples,Footnote 8 as well as the original unmatched samples, and the interaction effect for education and political interest was consistent with what we report here in the final models shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1. Thus, we consider the findings from the models to be robust.

Results

Descriptive Results

We begin our analysis with the descriptive information shown in Table 1. The table shows the frequency distributions of independent and dependent variables in the Philippine sample. For the categorical variables, we show the corresponding numbers of observations and percentages; for the continuous variables, we list the averages and the standard deviations. First, we can see that all waves of data contain the same number of observations, and the observations are equally distributed in terms of gender, showing that all waves of surveys were carried out consistently and systematically. The average age of surveyed respondents is 41.44 years old, with a standard deviation of 15.37; most are married (74.94%), living in an urban area (60.90%), and Christian (93.81%).Footnote 9

For education, a main variable in the informed citizen thesis, 13% of respondents report having a college degree. Now, turning to the continuous measurement of education, we find the average years of education is 9.29, with a standard deviation of 3.50. Although the elementary schooling education became mandatory in 1987, soon after the toppling of the authoritarian regime, many never had a chance to enjoy it: 13% of the sample has little or no formal education. The patterns of the two educational measures are consistent with each other. For the second focal variable, frequency of Internet use, we see that a slight majority still does not use the Internet as the main information source; 56.85% never go online and only 19.85% surf online at least weekly. The final focal variable is the respondent’s interest in politics. We find only a small proportion of the population is “very interested in politics” (13%).

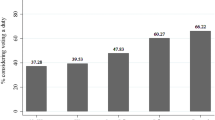

The average score of confidence in the police is 2.53, with a standard deviation of 0.88, which could be seen as moderately supportive overall. We further look into how this variable differs across waves of surveys. The mean values for confidence in the police for the four waves of ABS data are 2.43, 2.45, 2.6, and 2.62, respectively, which shows a moderate yet steady trend of increasing trust in police. This trend could be explained by the rising accountability and reducing corruption in the Filippino police system in the past years. We will discuss further findings in the next section of the regression analysis.

Modeling Results

Table 3 displays the results from the OLS regression models of trust in police. We begin with model 1, which includes all the covariates and the focal variables’ main effects. Model 1 tests hypotheses 1 and 2 that education and Internet usage will reduce confidence in the police, and hypothesis 3 that interest in politics will reduce confidence.

First, we notice respondents in later waves, compared to earlier waves, have more confidence in the police. Second, age in years has a significantly negative impact, but the effect size is small (− 0.0017). Under such an effect size, a 70-year-old would only be 0.085 lower than a 20-year-old young person in terms of confidence in the police. Third, males, on average, trust the police more than females by 0.05 points on a 1–4 scale. Religious affiliation also matters: a non-Christian has higher confidence in the police than a Christian Filippino. Living in the urban area lowers people’s confidence quite significantly, by 0.22 points. Not surprisingly, trust in the national or central government in Manila is a variable highly correlated with confidence in the police. For people who say they “very much trust” the national government, confidence in the police is 1.04 points higher than the reference group, which does not trust the national government at all. The corresponding numbers for “some trust in national government” and “not very much trust in national government” gradually decrease to 0.72 and 0.33, respectively. The model explains 18% of the variance in confidence in the police.

Now we turn to the focal variables, Internet usage, education, and interest in politics. Model 1 shows that using the Internet lowers people’s confidence in the police, but this only applies to the group, which heavily relies on web news. The model also finds supportive evidence for an educational effect but no significant evidence of the role of interest in politics. Each year of education brings a 0.02 point drop in confidence. When we compare people who completed a university degree (i.e., 16 years of education) to those who only finished elementary school (6 years of education), we find the former is 0.2 points lower than the latter in terms of confidence in the police. However, interest in politics shows neither significance nor a noteworthy effect size. In other words, model 1 supports hypotheses 1 and 2 on the effects of education and the Internet, but it does not support hypothesis 3 on the effect of interest in politics.

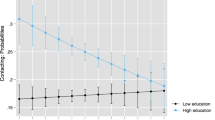

Our second model tested hypothesis 4. We retained all the previously used covariates from model 1 and added the interaction term between the interaction effect between education and interests in politics. Table 3 shows our results. The R-square value for model 2 is 0.18. As the table indicates, the control variables do not change much from model 1, and the findings for these variables are the same, as are the findings for the roles of age, gender, religious affiliation, location of residence, and Internet usage. Our focal term is shown in the last row of Table 3: here, we see that the estimate from the interaction term is significant, and the effect size is − 0.02. In other words, interest in politics moderates the influence of education; if a person is highly interested in politics, his or her education will have a greater impact on confidence in the police.

Such an interaction effect is also seen in Fig. 1, a visualization of the effects of the focal predictors. The X-axis is years of education, ranging from 0 to 20 years; the Y-axis is the dependent variable, confidence in the police. Though confidence in the police ranges from 1 to 4, the figure only displays from 2 to 3 for better presentation. The other predictor, interest in politics, is represented by the two lines—the dashed red line stands for people who are highly interested in politics and the solid black line for those who are not as interested. The patterns of the matched and unmatched samples are almost the same, and they are consistent with our previous findings from the regression analysis: educated people are more critical, and high interest in politics makes their critical attitudes even more apparent, as indicated by the steeper slopes in both figures. In sum, our regression analysis supports hypotheses 1, 2, and 4.

Conclusion and Discussion

Aas (2012) argues that there has been a geopolitical imbalance in the production of criminological knowledge in English. The Philippines is one of the nations with little information on the sources of confidence in the police. This study attempts to add some situated criminological knowledge to the Philippine police (Cao et al. 2016). The study investigated the effects of informed citizen thesis on confidence in the Philippine police. We drew on the Asian Barometer Survey data from 2002 to 2014, a period covering two presidencies: President Arroyo (2001–2010) and President Aquino III (2010–2016). Our regression analysis yielded a few noteworthy findings.

First, we have found a wave effect in the Philippines: confidence in the police improved for every new survey from 2002 to 2014. Regardless of any remaining issues, then, Filipinos have gradually improved their confidence in the police over the years. This suggests tangible progress in Philippine democracy during the survey period: as the democratic consolidation thesis would predict, a stabilized democracy would experience an elevated level of trust in the police (Cao et al. 2012). Second and more importantly, with more controlled variables in our model, Filipinos with more years of education tend to trust the police less. This finding is consistent with previous work on Filippino confidence in the police (Cao and Dai 2006) and, more generally speaking, with studies of trust in authorities (Hakhverdian and Mayne 2012; Kim 2010; Wang 2005; Zhang 2020; Zhang et al. 2017). Besides, frequent Internet users (with the caveat that only 19% of Filipinos use the Internet daily) are more critical of the police, supporting the informed citizen thesis. More broadly, urban residents are less confident in the police than rural residents. This is consistent with the findings reported by Wu (2014) for China and Taiwan. Collectively, we have found supportive evidence for the informed citizen thesis: more education and more information making people more critical. The mechanism explaining such an association is well established: education enlightens people by exposing them to information and encouraging critical thinking. We note that such an association cannot be fully explained away by claiming that people who attain more education are more affluent. Our analysis of the PSM matched, and unmatched samples partially eased the concern of selection bias.

Another key finding was the role of political interest. In the Philippines, having an interest in politics does not make someone trust the police more or less. Although hypothesis 3 on the effect of an interest in politics was not supported, we found supportive evidence for hypothesis 4. Specifically, an interaction effect between education and interest in politics on confidence in the police was revealed. In other words, interest in politics could moderate the previously found association between education and confidence. Education’s enlightenment effect was more salient for those who were very interested in politics. For those who were less interested, education still had an influence, but a much weaker one, as indicated by both Table 3 and Fig. 1. Again, this finding was true for both matched and unmatched data.

Based on our findings, we conclude that from 2002 to 2014, better-informed and better-educated Philippine citizens were more critical of the police, an arm of state authority. Besides, the enlightenment role played by education has had a greater impact on Filipinos who care about politics more than those who are indifferent. The discovered associations between education, interest in politics, and confidence in the police have larger implications and could shed light on other social phenomena in the Philippines and other societies. First, they show the importance of both education and political involvement in democratic transitional societies. Education matters for a liberal mindset, as previously found by many scholars (Andersen and Fetner 2008; Milner 2002; Norris 1999; Stack et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2017; Zhang and Brym 2019); however, education cannot fully exert its influence unless the person pays attention to politics and is interested and engaged. In other words, to foster a robust civil society, we not only need more education, but we also need more civic participation (Hu et al. 2015).

Second, the finding of the diverging attitudes may illuminate the issue of value polarization. For indifferent people, the variations in attitudes matter less, but for those who are very interested in politics, going to university or not going to university matters greatly—their opinions could be very different. This moderating effect could help us understand why in today’s world, online debates are so argumentative; when people are committed to politics and come from different social, economic, and cultural backgrounds, such differences are likely to be enhanced and therefore less likely to be easily reconciled.

The study of the Philippine confidence in the police is important because confidence not only represents an indicator of contemporary social sentiments but likewise constitutes an indicator for future social reform (Cao et al. 2016; Ren et al. 2005; Stack et al. 2010). The policy implication from the current study is that the impact of education on confidence in the Filipino police should be of special concern to law enforcement administrators. As the most visible and symbolic formal social control agents (Manning 2010), police officers furnish the technological and organizational answer to the Hobbsian question of social order, the deus ex machine (Cao and Dai 2006). Like many neighborhood problems, even though the police exercise no control over the population’s educational level, citizens’ confidence in the police is related to it. This result has sent a strong signal to the Filipino police administration that they need to overcome the past autocratic inertia and hasten to embody democratic values in their practice. They must rebuild confidence, especially with those who are better educated. In general, intelligentsia serves as the opinion leaders in a functional democracy. Their opinions matter more. Police have no other options, such as to oppress them during the authoritarian regime, but to respect their opinion and further reimage and reform its force to act in consistency with what the democratic policing demands in providing impartial services to citizens, upholding procedural justice, and maintaining political neutrality (Cao et al. 2016; Manning 2010). All suggestions and programs of confidence-building should be taken seriously. This policy recommendation is especially important in the era of Duterte’s regime, where the police are ordered to take draconian measures in solving the perceived “drug problem,” which has fueled deeper mistrust toward the police (Lasco 2018; Maxwell, 2019). Under the current situation, improving citizens’ confidence is likely to be a daunting challenge and a long-term task for police agencies.

The study has some limitations, and we hope future work will overcome them. First, since the Asian Barometer Survey is a multi-wave cross-sectional dataset, instead of a panel study, our findings do not serve as direct causal evidence. The links we found between education, use of the Internet, interest in politics, and confidence in the police should be interpreted cautiously. The effect of education and access to information could lead to certain attitudes or certain political orientations, and opinions, in turn, may change the way people use media and information sources. In the future, scholars may build a stronger case using panel data. Second, we analyzed secondary data, and the survey items are still too general to reveal the rich complexity of the concepts being measured. For example, the dependent variable confidence in the police is a single item. Also, we may know how often a person uses the Internet, but we do not know what websites and mobile apps he or she uses or which media sources he or she mainly relies on. We now know frequency matters; the next step is to know “frequency of what”? Knowing the details will clarify the link between information, political interests, and confidence in the police.

Third, although the survey claims to be random, Christians and middle-class citizens may be over-represented, with an inadequate number of non-Christians or remote island residents with little education. Timing is also important for all surveys (Cao and Stack 2005). The gradually improved confidence in the police may partially account for the current support for President Duterte’s highly controversial anti-drug and anti-corruption campaigns (Curato 2017; Lasco 2018; Maxwell 2019). Maxwell (2019) has analyzed the reasons for Duterte’s anti-crime popularity, and it will be interesting to see whether Filipinos remain confident in the police under his regime and afterward.

Notes

In other countries, the ABS surveys were conducted in slightly different years within the same wave. The first wave of surveys was carried out in 2001–2003, the second wave in 2005–2008, the third and the fourth in 2010–2012 and 2014–2016, respectively.

The variable “self-reported income status” was excluded in our later data analysis because of its high missing rate and non-significance. To ensure robustness, we fitted the models both with and without income levels, and the main findings did not differ in either condition. Data and codes are available upon request.

R package “Amelia II” employs EMB (expectation maximization with bootstrapping) methods. We reported the descriptive and regression results based on the pooled, complete data with 72,118 observations for the entire ABS data and 4800 observations from the Philippines; this means all the original data were retained in the analysis.

From the very few cases who reported “do not understand the question,” most of them are from less-educated groups (less than elementary school) or the elder cohorts. Therefore, we assume they choose this item because they sincerely do not understand and it implies, they do not use the Internet. This step is taken for ensuring higher valid response rate; and we tried both with and without these respondents, which does not change our main findings at all.

In preliminary analyses, we fitted the models with age and age’s quadric term; the results of an ANOVA showed age was sufficient.

The respondent could give the following responses as well: “Do not understand the question,” “Cannot choose,” and “Decline to answer.” These responses would be considered missing information.

Codes and results of ordered probit models are available from the authors upon request.

Codes and results are available from the authors upon request.

The variables of marital status and religious affiliation were used in the propensity score matching steps, so we included them in the descriptive analysis; they were excluded from the final regression models because of lack of significance.

References

Aas, K. F. (2012). The earth is one but the world is not: criminological theory and its geopolitical divisions. Theoretical Criminology, 16(1), 5–20.

Andersen, R., & Fetner, T. (2008). Economic inequality and intolerance: attitudes toward homosexuality in 35 democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 942–958. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00352.x.

Arugay, A. A. (2017). The Philippines in 2016: the electoral earthquake and its aftershocks. Southeast Asian Affairs, 277–296. https://doi.org/10.1355/9789814762878-019.

Austin, P. C. (2014). A comparison of 12 algorithms for matching on the propensity score. Statistics in Medicine, 33(6), 1057–1069. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.6004.

Azfar, O., & Gurgur, T. (2008). Does corruption affect health outcomes in the Philippines? Economics of Governance, 9(3), 197–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-006-0031-y.

Asia Barometer. (2018). The Asia barometer survey data. https://www.asiabarometer.org/en/data [].

Bennett, S. E. (2002). Americans’ exposure to political talk radio and their knowledge of public affairs. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 46(1), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4601_5.

Boda, Z., & Szabó, G. (2011). The media and attitudes towards crime and the justice system: a qualitative approach. European Journal of Criminology, 8(4), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370811411455.

Bottoms, A., & Tankebe, J. (2012). Beyond procedural justice: a dialogic approach to legitimacy in criminal justice. The Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 102, 119–170.

Cao, L. (2015). Differentiating confidence in the police, trust in the police, and satisfaction with the police. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 38(2), 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1108/pijpsm-12-2014-0127.

Cao, L., & Dai, M. (2006). Confidence in the police: where does Taiwan rank in the world? Asian Journal of Criminology, 1(1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-006-9001-0.

Cao, L., & Graham, A. (2019). The measurement of legitimacy: a rush to judgment? Asian Journal of Criminology, 14(4), 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-019-09297-w.

Cao, L., & Stack, S. (2005). Confidence in the police between America and Japan: results from two waves of surveys. Policing, 28(1), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510510581020.

Cao, L., Frank, J., & Cullen, F. T. (1996). Race, community context, and confidence in the police. American Journal of Police, 15(1), 3–22.

Cao, L., Lai, Y. L., & Zhao, R. (2012). Shades of blue: Confidence in the police in the world. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.11.006.

Cao, L., Huang, L., & Sun, I. (2016). The development and reform of police training and education in Taiwan. Police Practice and Research, 17(6), 531–542.

Correia, M. E., Reisig, M. D., & Lovrich, N. P. (1996). Public perceptions of state police: an analysis of individual-level and context variables. Journal of Criminal Justice, 24, 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2352(95)00049-6.

Curato, N. (2017). Flirting with authoritarian fantasies? Rodrigo Duterte and the new terms of Philippine populism. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 47(1), 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2016.1239751.

Dai, M., Hu, X., & Time, V. (2019). Understanding public satisfaction with the police. Policing: An International Journal, 42(4), 571–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/pijpsm-08-2018-0110.

Dalton, R. J. (2015). The good citizen: how a younger generation is reshaping American politics. CQ Press.

Delli Carpini, M. X. (2000). In search of the informed citizen: what Americans know about politics and why it matters. The Communication Review, 4(1), 129–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714420009359466.

Eschholz, S., Blackwell, B. S., Gertz, M., & Chiricos, T. (2002). Race and attitudes toward the police: assessing the effects of watching “reality” police programs. Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(4), 327–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0047-2352(02)00133-2.

France-Presse, A. (2017). A long history of corruption in the Philippine police force. South China Morning Post on January 18th, 2017. Accessed on may 15th, 2019. Link via: https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/2063245/long-history-corruption-philippine-police-force

Hagen, I. (1997). Communicating to an ideal audience: news and the notion of the “informed citizen.”. Political Communication, 14(4), 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/105846097199209.

Hakhverdian, A., & Mayne, Q. (2012). Institutional trust, education, and corruption: a micro-macro interactive approach. The Journal of Politics, 74(3), 739–750. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381612000412.

Hapal, K., & Jensen, S. B. (2017). The morality of corruption: a view from the police in the Philippines. Corruption and Torture: Violent Exchange and the Everyday Policing of the Poor, Aalborg: Aalborg University, 39-68.

Highton, B. (2009). Revisiting the relationship between educational attainment and political sophistication. The Journal of Politics, 71(4), 1564–1576. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381609990077.

Honaker, J., King, G., & Blackwell, M. (2011). Amelia II: a program for missing data. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(7), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i07.

Hu, R., Sun, I. Y., & Wu, Y. (2015). Chinese trust in the police: the impact of political efficacy and participation. Social Science Quarterly, 96(4), 1012–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12196.

Inoguchi, T. (2017). Confidence in institutions. In T. Inoguchi (Ed.), Trust with Asian characteristics: Interpersonal and institutional (pp. 143–167). New York, NY, UK: Springer.

Jang, H., Joo, H. J., & Zhao, J. S. (2010). Determinants of public confidence in police: an international perspective. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(1), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2009.11.008.

Kim, S. (2010). Public trust in government in Japan and South Korea: does the rise of critical citizens matter? Public Administration Review, 70(5), 801–810. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02207.x.

Lai, Y.-L., Cao, L., & Zhao, J. (2010). The impact of political regime on confidence in legal authorities: a comparison between China and Taiwan. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(5), 934–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.06.010.

Lasco, G. (2018). Kalaban: Young drug users' engagements with law enforcement in the Philippines. International Journal of Drug Policy, 52, 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.11.006.

Lee, H., Cao, L., Kim, D., & Woo, Y. (2019). Police contacts and confidence in the police in a medium-sized city. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 56, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2018.12.003.

Li, Y., Ren, L., & Luo, F. (2016). Is bad stronger than good? The impact of police-citizen encounters on public satisfaction with police. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 39, 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1108/pijpsm-05-2015-0058.

Mangahas, M. (2005). Gloriagate: can the Filipinos forgive Arroyo’s faux pas? https://www.khaleejtimes.com/editorials-columns/gloriagate-can-the-filipinos-forgive-arroyo-s-faux-pas

Manning, P. (2010). Democratic policing in a changing world. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Marien, S., & Hooghe, M. (2011). Does political trust matter? An empirical investigation into the relation between political trust and support for law compliance. European Journal of Political Research, 50(2), 267–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01930.x.

Maxwell, S. R. (2019). Perceived threat of crime, authoritarianism, and the rise of a populist president in the Philippines. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 43(3), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2018.1558084.

Mazerolle, L., Antrobus, E., Bennett, S., & Tyler, T. R. (2013). Shaping citizen perceptions of police legitimacy: a randomized field trial of procedural justice. Criminology, 51(1), 33–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2012.00289.x.

Mihailidis, P., & Thevenin, B. (2013). Media literacy as a core competency for engaged citizenship in participatory democracy. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(11), 1611–1622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213489015.

Milner, H. (2002). Civic literacy: how informed citizens make democracy work. UPNE.

Nisbet, E. C., Stoycheff, E., & Pearce, K. E. (2012). Internet use and democratic demands: a multinational, multilevel model of internet use and citizen attitudes about democracy. Journal of Communication, 62(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01627.x.

Norris, P. (1999). Critical citizens: global support for democratic government. OUP Oxford.

Payne, B. K., & Gainey, R. R. (2007). Attitudes about the police and neighborhood safety in disadvantaged neighborhoods: the influence of criminal victimization and perceptions of a drug problem. Criminal Justice Review, 32(2), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734016807300500.

Reisig, M. D., & Giacomazzi, A. L. (1998). Citizen perceptions of community policing: are attitudes toward police important? Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 21(3), 547–561. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639519810228822.

Ren, L., Cao, L., Lovrich, N., & Gaffney, M. (2005). Linking confidence in the police with the performance of the police: community policing can make a difference. Journal of Criminal Justice, 33(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2004.10.003.

Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41.

Schudson, M. (1998). The good citizen: a history of American civic life. New York: Martin Kessler Books.

Schutz, A. (1976). The Well-Informed Citizen. In The well-informed citizen, In Collected papers II (pp. 120–134). Dordrecht: Springer.

Skogan, W., & Frydl, K. (2004). Fairness and effectiveness in policing: the evidence. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press.

Stack, S. J., & Cao, L. (1998). Political conservatism and confidence in the police: a comparative analysis. Journal of Crime and Justice, 21(1), 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648x.1998.9721066.

Stack, S., Adamczyk, A., & Cao, L. (2010). Survivalism and public opinion on criminality: a cross-national analysis of prostitution. Social Forces, 88(4), 1703–1726. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2010.0029.

Sun, I., Hu, R., & Wu, Y. (2012). Social capital, political participation, and trust in the police in urban China. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 45(1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865811431329.

Sun, I. Y., Wu, Y., Triplett, R., & Wang, S. K. (2016). The impact of media exposure and political party orientation on public perceptions of police in Taiwan. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 39(4), 694–709. https://doi.org/10.1108/pijpsm-08-2015-0099.

Sun, I. Y., Li, L., Wu, Y., & Hu, R. (2018). Police legitimacy and citizen cooperation in China: testing an alternative model. Asian Journal of Criminology, 13(4), 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-018-9270-4.

Tyler, T. R. (1990). Why people obey the law. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Tyler, T. R. (2001). Public trust and confidence in legal authorities: what do majority and minority group members want from the law and legal institutions? Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 19(2), 215–235. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.438.

Tyler, T. R. (2002). A national survey for monitoring police legitimacy. Justice Research and Policy, 4(1–2), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.3818/jrp.4.1.2002.71.

Wang, Z. (2005). Before the emergence of critical citizens: economic development and political trust in China. International Review of Sociology, 15(1), 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906700500038876.

Weitzer, R., & Tuch, S. (2004). Reforming the police: racial differences in public support for change. Criminology, 42, 391–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2004.tb00524.x.

Wu, Y. (2014). The impact of media on public trust in legal authorities in China and Taiwan. Asian Journal of Criminology, 9(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-013-9177-z.

Wu, Y., & Cao, L. (2018). Race/ethnicity, discrimination, and confidence in order institutions. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 41(6), 704–720. https://doi.org/10.1108/pijpsm-03-2017-0031.

Wu, Y., & Sun, I. (2009). Citizen trust in police: the case of China. Police Quarterly, 12(2), 170–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611108330228.

Zhang, T. H. (2018). Contextual effects and support for liberalism: a comparative analysis. Doctoral dissertation: University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

Zhang, T. H. (2020). Political freedom, education, and value liberalization and deliberalization: a cross-national analysis of the world values survey, 1981-2014. The Social Science Journal, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03623319.2020.1727221.

Zhang, T. H., & Brym, R. (2019). Tolerance of homosexuality in 88 countries: education, political freedom, and liberalism. Sociological Forum, 34(2), 501–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12507.

Zhang, T. H., Brym, R., & Andersen, R. (2017). Liberalism and postmaterialism in China: the role of social class and inequality. Chinese Sociological Review, 49(1), 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2016.1227239.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editor Professor Jianhong Liu and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Dr. Tony Huiquan Zhang’s contribution to this paper is supported by a research grant (Grant Number: SRG2019-00171-FSS) provided by the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Macau.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

This article only uses archival data and does not contain any studies with human participants; therefore, it does not require informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T.H., Sun, J. & Cao, L. Education, Internet Use, and Confidence in the Police: Testing the “Informed Citizen” Thesis in the Philippines. Asian J Criminol 16, 165–182 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-020-09323-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-020-09323-2