Abstract

The illicit supply of new psychoactive substances (NPS) in and from China has become a global concern. In line with the international prohibitionist regime, China has instituted a “zero tolerance” supply reduction policy, enacted various laws to regulate controlled substances, and punished related criminal behaviors severely. However, how the NPS supply is organized and how the national laws are interpreted and implemented at the local level have rarely been addressed. Data from qualitative interviews with governmental and judicial actors are used to investigate the experiences concerning the illicit supply of methcathinone and the dynamic ways in which drug policy and laws are implemented practically. Findings show the significance of Changzhi city as a distribution center for illicit supply of methcathinone, the fixed supply patterns, the prioritized measures for controlling methcathinone supply and demand, and the personal strategies used by individual actors to cope with political pressures and job requirements. This study concludes that the unbalanced coexistence of campaign-style and conventional governance results in active institutional arrangements and passive personal strategies in implementing the drug policy and further contributes to a discrepancy between policy formulation and its implementation in practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

New psychoactive substances (NPS) are defined as substances, either in a pure form or a preparation, that are not controlled by the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, as amended by the 1972 Protocol (1961 Convention) or the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances (1971 Convention), but which may pose a threat to public health (The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC] 2013). The emergence of NPS is not an entirely new phenomenon (Seddon 2014). Some NPS were initially synthesized for pharmacological and toxicological purposes and were used in chemical and pharmaceutical areas many years ago. For example, fentanyl was introduced as a prescription medicine in 1960 to replace morphine and other opioids for use in cardiac surgery (Nelson and Schwaner 2009). Around the same time, ketamine was also synthesized and developed to be a safe anesthetic drug with potent analgesic properties (Mion and Villevieille 2013). In addition, there are some NPS that have little or no history of medicinal use, such as JWH-007, JWH-018, and JWH-015 (UNODC 2013). In these cases, the pharmacology and toxicology of these substances have not been well characterized (King and Kicman 2011). However, the increasing emergence of NPS and the rapid growth of NPS misuse have become a global issue that threatens public health, drug policy, and the legal system in many countries (EMCDDA 2016, 2017; EMCDDA and Eurojust 2016; UNODC 2017; Seddon 2014). In response, the international community insists on a prohibitionist model in order to reduce the spread of NPS. Traditional legal bans under the prohibitionist framework have been endorsed by much research, as a substantial reduction in the emergence and use of NPS in drug marketplaces has been noted in several countries (Kavanagh and Power 2014). Accordingly, controlling unauthorized supply of NPS through criminal law has been the default national response (Hughes and Winstock 2012).

In line with the prohibitionist and reactive regime at the international level (Chatwin 2017), policies such as “zero tolerance” and “war on drugs” have been the touchstones of drug legislation in China. Under this system, NPS with medical value are regulated by the Regulation on the Administration of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Drugs (RANDPD), while NPS without medical value are prohibited by the Regulation on the Administration of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substance for Non-medical Use (RANDPSN). The RANDPD establishes an approval system that allows substances to be legally manufactured and sold with licenses. These substances are listed in the Catalog of Narcotic Drugs and the Catalog of Psychotropic Drugs, which was amended in 2005, 2007, and 2013, resulting in a list of 270 controlled substances. In contrast, the RANDPSN prohibits the manufacture, distribution, use, and exportation of those NPS considered to be without medical value. When the controlled substance list under this Regulation was first issued in 2015, 116 NPS without medical value were included in it. Subsequently, twenty-two new substances were added to the list in 2017. The last update on August 28, 2018 added thirty-two more NPS to the list, bringing the total to 170 NPS prohibited under the RANDSPN. In response to the rapid increase in the emergence of new substances, the RANDPSN also provides a basic procedure for assessment and regulation. For example, the China National Narcotics Control Commission (CNNCC) may submit proposals on regulating new substances to an expert committee, which assesses the following aspects: 1) addiction or addiction potential; 2) health risks; 3) illicit manufacture, transportation, and smuggling; 4) consumption status; and 5) harm to society at the national and international level. The assessment must be completed within 3 months, and the results should be submitted to the CNNCC, which then provides recommendations to legislators on whether the new substances should be controlled or not.

Despite the prohibitionist regime in China, however, the illicit supply of NPS appears to have increased, as suggested by the significant increase in new emerging NPS and recent NPS seizures (EMCDDA 2018; UNODC 2018; Zhao 2019). For example, ketamine seizures amounted to around five metric tons in 2013, while they increased to 19.6 metric tons in 2015. In addition to ketamine, the country has witnessed a growing number of manufacturing facilities being dismantled by national authorities, resulting in a significant increase in NPS seizures which have increased from 20 in 2015 to 800 kg in 2016 (CNNCC 2016, 2017). In 2017, Chinese authorities identified 34 new substances, in addition to the 230 NPS already known substances seized in various parts of the country (International Narcotics Control Board [INCB] 2018). Thanks to the growing supply of NPS in and from China over the last few years, the global NPS market continues to be characterized by the emergence of large numbers of new substances belonging to diverse chemical groups (DEA 2016; EMCDDA 2015, 2017; Reuter 2011).

Taken together, the increased supply in a circumstance of prohibition legislation suggests that regulating the illicit supply of NPS depends not only on policy and legislation but also on the practical impact of enforcement (Hughes and Winstock 2012). In this respect, the ways in which Chinese drug policy and laws are implemented in practice could be an essential parameter for effective regulations (Scott 2004). In addition to the generally important role of the enforcement, the dynamic and diverse ways in which drug policy and laws are interpreted, manipulated, and implemented are also important (Lipsky 2010), because it is through the actions of practitioners that policy takes effect in practice (Frank et al. 2008). However, little attention has been focused on the enforcement process, which involves legislation, multiple actors with capacities for enforcement, the way in which these capacities are organized and structured, and the supply patterns experienced by these actors (Ayres and Braithwaite 1995; Seddon 2014). As a result, there may exist a knowledge gap that could limit our understanding of Chinese drug policy, in particular, the implementation of drug policy at the local level.

The laws and regulations in China have provided increased legal grounds for different actors at the local level to engage in the NPS reduction framework. Moreover, as a policy instrument, Chinese law is constantly subject to interpretation and intervention by police officers, narcotics control commission officials, prosecutors, and judges, who could develop their own strategies and coping mechanisms to overcome stressful dilemmas or try to push their personal agendas through by actively interpreting policies (Qin 2008). Hence, the application of legal and regulatory requirements often depends on political priorities and individual actors at the local level rather than on the text of law itself (Potter 2013). With the aim of exploring the law enforcement process in relation to the illicit supply of NPS in China, our central research question focuses on three dimensions: the supply patterns of methcathinone, the local legal responses, and the law enforcement process. In short, this study examines how drug policy and laws are implemented by institutional and individual actors to respond to the illicit supply of methcathinone at the local level.

To answer this research question, we narrowed our research focus to Changzhi city, where the illicit supply and abuse of methcathinone has been a primary concern for local authorities. We investigated actors’ experiences of implementing the drug policy and laws against the illicit production, transaction, distribution, and consumption of methcathinone. Through this investigation, three dimensions have been highlighted: Firstly, the illicit supply of methcathinone, including the establishment of a methcathinone market, the trafficking mode, and the role of the Internet; secondly, the local legislation and prioritized measures for controlling supply and abuse; and thirdly, the implementation of drug policy and laws, involving the operation of law enforcement at institutional and individual levels.

Method

Changzhi, one of the administrative regions in Shanxi, was chosen as the case study due to the number of NPS-related cases addressed by law enforcement agencies in this region, in comparison with others. In total, 859 criminal cases relating to the illicit supply of methcathinone were documented by Chinese courts between 2012 and 2018; of these, 580 cases originated in Shanxi. Of the 580 cases originating in Shanxi, 511 originated in the district of Changzhi. This significant number of cases in Changzhi offers a valuable sample for understanding the supply patterns of methcathinone and the consequent law enforcement and supply reduction measures. It also allows for scrutiny of the manner in which national law and policy are localized and implemented through law enforcement and judicial practices in a bureaucratically political system.

Data were generated through face-to-face meetings and interviews with respondents directly involved in policy-making, law enforcement operations, prosecutions, and trials in the city center and its four districts. Based on the important roles of narcotic control commissions, police departments, courts, and procuratorates on the frontline of controlling NPS (Fang 2011; Qin 2008, 2011; Sun 2016), the following departments were included in the study: the Municipal Narcotics Control Committee (MNCC), the Municipal Public Security Bureau (MPSB), the Intermediate People’s Court (IPC), the Municipal People’s Procuratorate (MPP), at the city level, as well as the Narcotics Control Committees (NCC), the Public Security Bureau (PSB), the Basic People’s Courts (BPC), and the Basic People’s Procuratorates (BPP) at the county level in four districts (Fig. 1). Two interviewees were recruited from each department, arriving at a total of forty individual interviewees.

Considering the high sensitivity of information regarding the illicit supply of methcathinone and the law enforcement process, it was necessary to obtain the trust of the actors (policymakers, police officers, judges, prosecutors) to mobilize their willingness to participate in interviews. Hence, snowballing could be an effective strategy to reach potential participants willing to engage in this research (Quinney et al. 2016; Sadler et al. 2010). Two prior positive relationships involving kinship and friendship were used to establish trust with successive interviewees. After receiving their informed consent, each interviewee was interviewed using a semi-structured topic list. The topic list was primarily developed on the basis of literature review which identified several features of the illicit supply of NPS at the street level, such as the involvement of the Internet, the organization of offenders, and the mode of communications (Qin 2011; Seddon 2014; van Amsterdam et al. 2015; Werse et al. 2018; You et al. 2017). On average, each interview lasted about 1 hour. The contents were only recorded in the form of notes because of the sensitive nature of the issue, which may negatively impact the development of the city and the promotion of local officials. The interviews were conducted in a closed office between 28 June 2018 and 22 December 2018.

The collected data was coded through the common approach of starting with some general categories, and then moving to more specific detail in Nvivo (Coffey et al. 2017). Through this approach, some initially pre-defined nodes based on the three dimensions included in the research question and the existing literature were developed into a tree of nodes (see Fig. 2). Under the guidance of the tree structure, the contents were coded. The initial coding processes were conducted after each interview. Several new nodes were added after the second coding process, such as abuse, reason for use, and personal strategy. After having gone through all the materials, these nodes, the result of the coding, were reviewed; separate nodes were analyzed and linked to documented evidence as well as literature.

Results

The Supply Patterns of Methcathinone at the Local Level

The Role of Changzhi in the Methcathinone Market

As a municipal administration region of Shanxi, Changzhi comprises of four municipal districts and eight counties with a total population of 3.3 million. Changzhi possesses rich mineral resources, particularly coal. The coal industry has been the primary driver of the local economy and accounts for almost half of the local revenue of the last three decades (Zhang 2013). Due to this industry, Changzhi ranks second in Shanxi in terms of GDP and is home to a large number of coal mining enterprises (state-owned enterprises, authorized private companies, and unlicensed individuals), coal workers, and other physical laborers, such as transporters (Office 2017).

The presence of large numbers of manual workers has been considered to be closely related to the prevalence of “mianmian,” a polydrug consisting of sodium benzoate and caffeine, since the 1990s (Fan 2008; Xiao 2018). Existing research has observed that the majority of “mianmian” users were physical workers who aimed to reduce fatigue and drowsiness and improve work performance (Berridge 2013). The spread of such consumption generated a huge demand for caffeine, which resulted in Changzhi becoming a primary destination for the illicit supply of caffeine in China in the 1990s (Fan 2008).

“Many coalminers started to use “mianmian” to refresh themselves and relieve pains in the late 1990s in Changzhi. Later, the number of users increased and the consumption habit has been widely accepted because of the low price. It is much cheaper than cigarettes.”

In response, local authorities prioritized measures for the regulation of the illicit supply of caffeine. For instance, local authorities instituted the “100-day anti-drug campaign” and the “strike hard campaign” in 1995. As a result, the number of users and registered cases dropped in the subsequent 5 years. However, in the early twenty-first century, a new drug called “jin,” consisting of caffeine and ephedrine, emerged in Changzhi’s drug market, and the number of users increased dramatically (Xiao 2018). Subsequently, “jin” seemed to become integrated into normal daily life. It was not limited to specific social groups such as farmers and manual workers who did physical work, but was also being used by officials, juveniles, teachers, and retirees. Moreover, the drug was being consumed in pursuit of particular sensations rather than to improve work performance. In this way, consumption began to be regarded as recreation, and the drug found its way into social settings such as weddings, funerals, and other events. Thirdly, the supply of “jin” in public areas such as hotels, restaurants, and even roadside stalls became common (Fan 2008). Thus, in this period, “jin” no longer appeared to be subcultural drug used within a particular social group (Goode 1989). Rather, its use became normalized and integrated into the daily lives of people across different classes in Changzhi city.

“With the development of the economy in both rural and urban areas, farmers and citizens had money to sustain their daily needs; they also had the extra money to buy “jin” for recreation. Recently the consumption of “jin” has come to be regarded as a symbol of wealth and nobility. “Jin” became the substitute for other hospitality products at weddings and funerals. In some cases, it was even used to bribe local officials.”

Partially due to the normalization of “jin” consumption, the act of selling or sharing it with friends and colleagues was not perceived as “drug dealing.” As a result, demand reduction appeared difficult to achieve. In response to the limited availability of ephedrine in the context of strict regulations in the late 2010s, drug producers began to add methcathinone into “jin” as a substitute, which turned out to be a successful strategy (Xiao 2018). With the integration of methcathinone in “jin,” this drug began to be described as “better tasting, more powerful, not drugs, and not addictive” (Interview LPB2; GPB 1). As noted by Xiao (2018), the tradition of consuming “mianmian” and the improved taste of “jin” appear to have contributed substantially to the increased number of methcathinone users in 2016 (CFDA 2016).

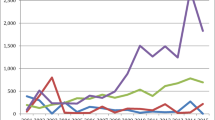

In line with the increased number of users and the corresponding demand, the illicit supply of methcathinone increased dramatically, as partly indicated by the rising number of cases prosecuted and offenders convicted in the last five years, as documented by MPP. While 128 drug cases were recorded in 2013, this number increased to 497 in 2017. The number of drug-related offenders also increased from 213 in 2013 to 619 in 2017. Of these, more than half involved the illicit supply of methcathinone. Compared with other cities in Shanxi and in other provinces, it appears that Changzhi has been the primary consumption and distribution center for methcathinone at both the provincial and national levels.

“Changzhi has been the distribution center for methcathinone. Drug dealers and users in other cities and provinces come to Changzhi because they know it is the place where they can sell or buy methcathinone. Most of the methcathinone is not produced in Changzhi, but in other provinces where precursor chemicals are easily obtained.”

Despite the size of the methcathinone market and the scope of harms being unknown, the experiences of policymakers, policy officers, procurators, and judges appear to suggest that Changzhi plays an important role in methcathinone distribution, but not production, in Shanxi as well as nationwide. However, Changzhi has not been found to have a noticeable role in smuggling methcathinone to other countries.

“There is no smuggling case in our administrative region. The majority of the cases involve drug dealing, including large package distribution and small sales at the street level. Changzhi is not a big city and the transportation system is backward. The dealers in this city do not have the knowledge to communicate with foreign clients, nor do they have the capacity to smuggle methcathinone to other countries.”

Methcathinone Trafficking Models in Changzhi

The organization of traffickers in the illicit supply of methcathinone ranges from individuals in charge of buying, transporting, and selling methcathinone within the sub-region to crime groups consisting of two to five members moving large volumes of the substance trans-regionally. However, there is no evidence of highly structured, hierarchical crime organizations involved in the drug market.

Individual traffickers are usually low-profile actors who engage sporadically in the supply of methcathinone to maintain their consumption. These small local operations usually involve short-distance trafficking flows at the street level. Sophisticated strategies, advanced communications technologies, and concealed packages were not noted among this group. Rather, their operations are quite simple. Normally, drug users directly communicate with the dealer via everyday communication tools, such as telephones, and more frequently, Internet apps, such as WeChat. The powdery substance, a mixture of methcathinone and caffeine, is packed in small transparent plastic bags (0.3–0.5 g/per bag), which is most commonly consumed nasally. The purity of methcathinone is estimated to be quite low, since there have been no documented cases of overdose in this city. The small amounts of substance trafficked in these local operations has resulted in several cases but few large seizures.

“Most of the individual traffickers are addicts. They are less educated and jobless. They are involved in drug dealing because they need money to support their use. I have cracked down many drug trafficking cases, involving small amounts and low purity. We only measured the weight, not the purity, because the latter is not necessary for conviction and sentencing.”

Small-to-medium criminal groups are a second model in the supply chain of methcathinone at the local level. These criminal groups function as medium- and large-scale operations within Shanxi province or across borders in different provinces. They are formed on the basis of ethnic, familial, or kinship bonds or other such unifying relationships. The number of members in such groups is limited, ranging from two to five in most cases. However, there have also been some family-based criminal groups with more than ten members. In contrast to groups based on ethnic and other relationships, family-based groups operate with a certain level of organization and hierarchy. Usually, the head of the family functions as the ringleader in charge of the business, while other family members undertook individual responsibilities under the head’s leadership.

“Most of the offenders are organized in small groups that are difficult to detect. There are a few large criminal groups. In 2011, we cracked down on a supply chain of methcathinone operated by a family, resulting in seizures of 375 kilograms and seven suspects arrested. All of them are of the same family.”

The Role of the Internet

The Internet has increasingly become an online marketplace for NPS users (Dargan and Wood 2013; van Amsterdam et al. 2015). It also facilitates several dynamics of this criminal activity, including drug trafficking (Lavorgna 2014). In our case, the Internet has not been used extensively in the supply chain, but seems to be an important facilitator for methcathinone trafficking.

An Aid for Production

The Internet has simplified the efforts involved in gaining production skills, exchanging experiences, and purchasing precursor chemicals by providing the public access to global media. Cyberspace has weakened or removed geographical, language, and psychological barriers, leading to a wide range of NPS-related information becoming available to the public and increasing the desire for access to such information. Notwithstanding the “most complex Internet censorship system in China” (Xu et al. 2011:133), it is still easy for local producers to circumvent firewalls through virtual private networks (VPNs). Broadly speaking, the Internet has offered many opportunities for potential producers to get involved in the production process.

The anonymity of the Internet has facilitated the dissemination of drug-related information (Gordon et al. 2006). Applications like Tencent QQ (QQ) and WeChat have been widely used for dispersing knowledge related to production methods. QQ chat rooms and WeChat groups have been the primary places for drug users, cooks, and dealers to share experiences and make transactions. However, access to such chat rooms and groups has been quite limited, and only those known by the administrators to be drug users, cooks, or dealers have been allowed to join in. The number of members in such groups could vary from a minimum of three to a maximum of 500. All the information in such chat rooms or groups is available to all the members. Cooks usually advertise their methods, skills, experience, and benefits and wait until potential targets take the bait. Once a deal is struck, the cook is responsible for teaching the producer how to produce NPS step by step, and in return, the producer pays thousands of yuan (Chinese currency).

“The Internet plays an important role in methcathinone production. The skills and inputs for methcathinone production are quite simple; you just need precursors and some simple equipment, which are available on the Internet. Sometimes, the dealers sell not only the precursor, but also the skills, or provide the “recipe” for free. Some offenders also learn the production process by themselves on the internet.”

The Internet has also been used as a channel for purchasing precursor chemicals, including controlled chemicals and legal chemical products, from chemical companies and individuals. Two types of transactions have been noted between corporate suppliers and their clients. The first involves producing chemicals legitimately but selling them illegally, while the second involves producing and selling chemicals illegally. For example, chemical companies might advertise their products on websites to attract local and international clients, including “pick-up-service” at the local level and the logistics companies delivery at the international level. Alternatively, purchase orders noting the specific chemicals needed may be sent to chemical companies in advance. Following this, corporations might produce the necessary chemicals and transport them through logistics companies.

A Tool for Supply Operations

The Internet has also been used for the distribution of methcathinone by individuals. In such cases, traffickers use the Internet to purchase, sell, package, and transport methcathinone. This eliminates the need for a physical presence, as all activities can be conducted through social media platforms. In this process, traffickers first advertise their product on websites to attract clients. Once contacted by clients, the trafficker purchases the amount of substance needed from his/her online sources and then transports the products by express consignment.

Among criminal groups, the Internet plays a more complex role. It is used not only to establish illicit business between different actors but also to mobilize and organize group members. The loose criminal networks are managed by single individuals through the use of QQ and Wechat, both of which have functions that can be used for surveillance, such as location services and video chat. This allows the organizer to grasp the overall situation and process details through remote visualization of production and transportation. In contrast to traditional single line communication, Internet apps such as QQ, Wechat, and others also offer users multiple ways of communication. In particular, chat groups allow information to be shared and exchanged by all members at the same time. This seems to be closely related to the simple hierarchical structure of these family-based criminal groups in which the ringleader has a higher status and is in charge of everything, while signals of status differentiation among other members are unclear. Thus, the Internet helps the organizers to manage the supply operations effectively and minimize the risk of being arrested and prosecuted.

A Channel to Extend the Market

The Internet has also been used to maximize profits by bringing a wider pool of potential targets from various socio-economic and geographic backgrounds within reach of retailers. Most often, retailers would start online shops on e-commerce platforms, such as Taobao, Tmall, and JD.com. In the early 2010s, e-commerce enabled retailers to advertise and sell their products quite openly, though some of these online marketplaces have since been controlled. Following the legalization of liability for Internet intermediaries in 2015, several special campaigns have been conducted against the illicit supply of methcathinone through the Internet. Hence, many online shops have been closed. However, several retailers have tried to continue online sales under the guise of legitimate businesses, such as cloth shops and tea stores. Their advertisements seem no different from those of other legitimate online stores, but contain links directing clients to a dark shop where various NPS are available. Some online stores have tried to circumvent law enforcement by labelling their products as “not for sale” on their websites. However, the platforms are used to conduct transactions and receive payments, as well as to send out shipments by express consignment.

A Tool to Facilitate Financial Transactions

Ultimately, the Internet has been used as a tool for making payments, which simplifies the transaction process and makes it difficult for law enforcement to collect evidence. For online retailers, online platforms function as a guarantor in facilitating the transaction. When clients make payments, the money is not automatically transferred to retailers’ accounts. Rather, it is held by the online platforms and transferred to the retailers only after confirmation from clients that they have received their parcels. For street dealers, the Internet also offers forms of electronic payment. Two payment instruments frequently used by dealers and users were Alipay and WeChat. Here, the payment process is simple and quick. Dealers show a Quick Response Code on their phones, and users scan the code and complete the transactions immediately. After that, transaction records are deleted to avoid the risk of checking by law enforcement.

“The wide use of Alipay and WeChat in retail cases challenges the traditional methods of law enforcement. If we find cash and drugs at the same time, we can arrest suspects and prosecute them for drug trafficking. But now there is almost no cash any more in drug trafficking cases at the street level. They make payments with Alipay and WeChat, and delete the records, so there is no evidence for drug trafficking, only for possession.”

Interpretation of the National Drug Policy and Laws

Concerning the implementation of laws and the supply reduction policy, the municipal authority is legally authorized to draft rules to specify the provisions that are necessary for law enforcement at the local level. Although the Municipal People’s Congress and Its Standing Committee (MPCSC) in Changzhi have not formulated any local regulations to respond to the illicit supply of methcathinone, there have been many administrative documents concerning prioritized measures for regulating methcathinone and the consolidation of the “zero tolerance” ideology.

Since 2015, when methcathinone trafficking in the city caught national attention, the local authority has put in place prioritized measures that have made targeting the production, distribution, transportation, and trafficking of methcathinone a primary task for the police at both municipal and county levels. The 2018 Report on the Work of the Government of Changzhi highlighted two tasks for the MPSB: a three-year special campaign against organized crimes and a routinized campaign against drug crimes without a time limitation. While there is no express documentation regarding arrangements for judicial departments, procurators are required to adhere to the “swiftness” principle in prosecution (Interview MP2), while judges have been “encouraged to give drug-related offenders severer punishments” (Interview MC1).

The local authority has also issued several documents aiming at strengthening the ideology of “zero tolerance” among governmental and social actors, including citizens, students, and offenders in communities and prisons. For example, all public officials were required in 2018 to visit the Drug Prevention and Education Base to learn the harms, threats, and challenges posed by various drugs, especially methcathinone. Concurrently, more than twenty publicity programs have been conducted by various departments in public areas, schools, communities, and prisons to target illicit supply and potential drug use, in particular methcathinone misuse. Although the effects of such publicity have not been measured, all the interviewees believed it to be useful and necessary for reducing methcathinone supply and demand.

“Publicity always comes first in our country. When your thoughts are corrected, you will think differently, you know it is morally wrong to use and supply drugs, and you do not want to try or use drugs anymore. When you know drug crimes will be punished severely, you don’t want to do it anymore.”

Law Enforcement Responses at the Local Level

The Structure and the Operation of Law Enforcement

In line with the plans of the local authority, the law enforcement response to illicit methcathinone supply directly involves two governmental branches: the MNCC and MPSB. As a coordination agency specifically focusing on drug issues, the MNCC was established to organize, coordinate, and guide the narcotics control operations in Changzhi city. However, the MNCC’s role has not been substantialized, and much of its specific work is undertaken by the MPSB, resulting in a low efficiency of narcotics control (Schurmann 1971). In the context of the spread of methcathinone, the narcotics control commission (NCC) in Xiangyuan county has been substantialized for the first time by the local authority, dividing the mixed structure of narcotics control into two independent groups, focusing on drug use and drug crimes respectively.

The first group aims at reducing demand, including through publicity and education programs, community drug treatment, and social workers’ training. These are conducted specifically by the NCC. Thanks to the substantialization of its role, the NCC has been able to recruit enough staff members to strengthen its publicity and education efforts. For example, the NCC has conducted more than 500 publicity and education programs in the last three years. In addition, it has also organized 55 teams of drug rehabilitation volunteers to help drug users to learn knowledge and skills. Simultaneously, a new rehabilitation model based on family mobilization, which regards the family as the main body and patients as the center and brings together drug users, their families, and doctors for drug rehabilitation, has been established and commonly used.

The second group of activities, conducted by the MPSB and its subordinate branches, focuses on the supply side of drugs. The MPSB has issued several handbooks specifically focusing on drug testing and administrative penalties for the illicit supply of controlled chemicals. The style of policing consists of urine tests, drug checkpoints, and special campaigns. Urine tests have been conducted randomly for all governmental staff members to prevent the involvement of local officials in drug use and supply. Moreover, mineral enterprises and express companies are also required to establish drug testing rooms and regularly conduct tests for their employees, at least twice a year. In addition, many drug checkpoints have been established at arterial points to curb the transportation and diversion of controlled substances to other cities and provinces. Special campaigns have also been frequently conducted by police to target the illicit supply of drugs, in particular methcathinone, which have resulted in 1511 drug-related cases and 2160 offenders being convicted and punished in the last 5 years in this city.

It is interesting to find that individual police officers are involved in the special campaign in two ways. The first involves the campaign-style policing organized by the MPSB, which are large-scale and target-oriented, but occasional operations (Ni and Yuan 2014). In these cases, individual police officers are well organized and their actions are unified and precise. The second involves conventional governance, focusing on the illicit supply of controlled substances as part of their daily work. In contrast to campaign-style policing, it is routinized but risky.

“Except the organized initiatives, we also go out on patrol regularly to check and investigate potential cases during the special campaign period. This is also a part of the campaign. When we check and notice someone who may be involved in drug trafficking, we need to decide if detention is necessary based on our experience. Because the drug analysis takes several days. So, it is risky. If the substance they have is confirmed to be drugs, then it’s OK. If it is not a drug, then I have big problems.”

Judicial departments including procuratorates and courts also play a role in implementing the supply reduction policy through the “swiftness” principle, reflected in the “speed” of prosecution and the severity of punishment. Concurrently, mass trials are also organized by the courts in public areas to achieve an intended deterrence effect. In these mass trials, criminals are exposed to a large audience and their crimes are denounced, followed by public sentencing and even executions in extreme cases (Liang 2005). For example, in 2018, the IPC organized an open trial with more than 200 spectators in a square, in which three major drug trafficking cases were tried, five offenders received the death penalty, and thirteen offenders were sentenced to life imprisonment (Table 1).

Personal Strategies in Implementing Local Arrangements

Local officials were reluctant to talk about the illicit supply of methcathinone, especially when they were told that this study would be written in English and would be available to have an international audience. In their opinion, the illicit supply of methcathinone is a crime that makes China “lose its face.” Thus, all of them supported the prohibitionist system and punitive measures against illicit supply behaviors.

However, with regard to local arrangements, several expressed complaints because of the great pressure and long work-hours generated by special campaigns. All of the departments have faced too many undertakings with limited human resources. For example, the criminal unit of a subordinate branch of the MPSB had only four regular police officers for responding to all criminal cases within a 100-square-kilometer area, with a population of one hundred thousand.

“Methcathinone trafficking should be targeted in priority and punished severely, that’s right. However, when the special campaign starts, we are required to report on our work every day, and have to spend many hours on paperwork, filling dozens of forms. At the same time, we still need to finish our jobs on time. This makes me exhausted.”

Thus, the prioritized policing measures impose an extra, seemingly unnecessary, workload on police officers, prosecutors, and judges. In response, many work extra to fulfill political requirements and their regular tasks at the same time, because their performance impacts their salary, promotions, and the yearly bonus. Alternatively, some departments recruit temporary employees to cope with the huge volume of work, resulting in a large number of temporary untrained-employees and limited regular staff members. Some officials in relatively top levels choose to focus on the political documents, rather than their regular tasks because more work means higher risk, which results in political inaction in the law enforcement process.

“There are so many tasks. I cannot finish all of them. So I choose to meet the political requirements firstly. For example, I report my work on time every day, and I prefer to assign the investigation and arrest tasks to other colleagues. I do not want to make mistakes in my job.”

Discussion

Our results suggest that Changzhi has been a distribution and consumption center rather than a source of methcathinone at the provincial and national levels, which is in line with the prevalence report on drug use in China (CFDA 2016), as well as the large number of drug trafficking cases documented by the Supreme People’s Court in the past 5 years. The reasons for this appear to be related to the high number of coal workers and the use certain drugs to improve work performance. At one point, this contributed substantially to the establishment of a coherent, closed, homogeneous, and normative drug subculture (Williams 1990; Yin et al. 2018). Under the impact of the subculture, the normalization of drug use appears to be an important facilitator for increased demand and the correspondingly increasing supply.

The two trafficking models in this city seem to suggest that a cottage industry, composed of a large number of small groups and individuals with weak organizational structures, is the main form of domestic drug trafficking (Eck and Gersh 2000; Zhang and Chin 2003). The use of the Internet in production, transportation, sale, payment, and communication has been noted, but such use appears relatively simplistic. Methcathinone is primarily obtained from sporadic dealers, rather than the Internet, which is in contrast to Europe and Australia, where the Internet has been an important source for many NPS (Burns et al. 2014; van Amsterdam et al. 2015). In addition, the use of the Internet for communication and payment may not imply a specific intent to circumvent law enforcement (Hao and Zhao 2012); rather, it appears to mirror the broader trend of informatization in China (You et al. 2017). As noted by Eck and Gersh (2000), drug traffickers use standard technologies available to most people, and secured telecommunication was rarely noticed in any of the interviewees’ work.

The interpretation and implementation of the supply reduction policy and laws in this city offer unique insights into the dynamic ways in which different departments, branches, and individual actors interpret policies and laws to respond to local concerns. Because of the political emphasis on methcathinone, various institutional arrangements have been instituted to strengthen law enforcement. Among them, campaign-style governance has been highlighted, recast, routinized, and further incorporated into the daily work of local departments, which results in huge pressure and extra workload for public officials. It seems that the coexistence of campaign-style governance and conventional governance aims at mobilizing individual actors to focus on prioritized issues and short-term objectives. At the same time, as a response to the political priority, judicial agencies including the IPP and the IPC, try to resort to a “swiftness” principle against NPS related crimes.

In contrast to these active institutional arrangements, the implementation of local arrangements at the individual level shows a range of personal strategies. Some individual actors show enthusiasm towards finishing their jobs, while others seem to respond to these arrangements in a passive way, such as the political inaction noticed in the local mechanisms of governance in most provinces in China (Ouyang 2010; Zhou 2008). As a result of the incompatibility between local arrangements and personal strategies, the implementation of the national drug policy and laws could be negatively affected. Namely, campaign-style governance could be gradually subsumed into political bureaucracy and has limited sustainable power to achieve Pareto optimality (Ni and Yuan 2014). Therefore, a discrepancy in policy formulation and its implementation in practice may exist (Lipsky 2010). The reason for the choice of personal strategies is still unknown. However, the experiences of the interviewees seem to suggest that the huge workload and the limited discretion in the execution of their work at the street level in the bureaucratic political system are two important facilitators.

Conclusion

Our study shows that qualitative interviews could obtain rich data from public officials in respect to drug markets, legal responses, and law enforcement measures. On this basis, our results have demonstrated that Changzhi has been a distribution center for methcathinone at the provincial and national levels, but not the international level. The supply patterns related to methcathinone, such as trafficking models, communication, and payment may not be specific to methcathinone, since they have been noticed in other drug cases. In addition, we have put great emphasis on the role of the Internet, which has been highlighted to be an important source of NPS by Western scholars. However, our results only suggest the ostensible involvement of the Internet in production, distribution, communication, and payment, rather than extensive involvement in retail at the street-level.

More importantly, this study shows the dynamic way in which the national laws and policy are interpreted and implemented by different departments and individual actors. In response to local concerns, municipal authorities try to prioritize active measures for supply reduction of methcathinone, including the consolidation of “zero tolerance” for public staff members, special campaigns of the police department, and the “swiftness” principle for judicial procedure. As a result, large number of methcathinone-related criminal cases have been identified and offenders punished severely, which has been regarded as a success in the short-term.

However, the coexistence of campaign-style governance and conventional governance has not been well balanced in an institutional way, which has a negative effect on some individual actors. In this case, many local officials experienced extra work burden, high pressure, and anxiety, resulting in many of them resorting to political inaction and posturing. This could limit the capacity of law enforcement in practice and further result in discrepancy between policy formulation and its implementation.

This study has several limitations. Its findings only represent the law enforcement situation in Changzhi city, but not in other cities and provinces. In this case study, a snowballing strategy was used to recruit interviewees, which also involves some limitations. For example, the snowballing strategy does not recruit a random sample; as a result, the sample might include an over-representation of individuals with numerous social connections who share similar characteristics (Magnani et al. 2005). Also, the effects of social desirability from respondents may have occurred, as respondents seemed not always completely honest (Phillips and Clancy 1972), particularly since drug-related crimes are a sensitive subject in China. The results are generated based on the experiences of interviewees. All of them work in the governmental and judicial departments, and the data could only reflect their truth rather than the accurate supply patterns in practice, namely the real truth. In addition, drug issues have been regarded as morally wrong, which makes these officials experience a feeling of “losing face.” In this case, there may be some bias regarding their subjective assessment of the laws and supply reduction policy, as well as the objective facts regarding the illicit supply of methcathinone in this city.

Future research could focus on the illicit supply of methcathinone at the local, national, and international levels to investigate the sources of NPS and their supply patterns based on different data sources, particularly the data generated from actors directly involved in NPS use and trafficking, such as drug users and offenders. For example, drug offenders could be an important data source, because researchers could get more personal opinion on the reason of crime and the specific environmental context in which the crime occurs and how offenders manage their relations to other offender groups. This will be beneficial for understanding how the small supply networks are managed by offenders and for the development of global south criminology in generating more reliable data. In addition, more research is needed to understand how local authorities choose their priorities, namely how they balance the requirements of central governments and local concerns. Further, it would also be interesting to investigate how the prosecutors and judges cope with the contradiction between campaign-style governance and rule of law at the individual level.

References

Ayres, I., & Braithwaite, J. (1995). Responsive regulation: transcending the deregulation debate. New York: Oxford University Press.

Berridge, V. (2013). Demons: our changing attitudes to alcohol, tobacco, and drugs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burns, L., Roxburgh, A., Matthews, A., Bruno, R., Lenton, S., and Van Buskirk, J. (2014). The rise of new psychoactive substance use in Australia. Drug Testing and Analysis, 6(7-8), 846–849.

CFDA. (2016). Annual Report on Drug Abuse Monitoring in China. Retrieved 2nd December 2018 from http://www.nncc626.com/2018-06/04/c_129886311_2.htm.

Chatwin, C. (2017). Assessing the ‘added value’of European policy on new psychoactive substances. International Journal of Drug Policy, 40, 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.11.002.

CNNCC. (2016). Annual report on drug control in China. Beijing: National Narcotics Control. Commission. Retrieved from: http://www.nncc626.com/2016-11/21/c_129372086.htm. Accessed 06-05-2019

CNNCC. (2017). Annual report on drug control in China. Beijing: National Narcotics Control. Commission. Retrieved from: http://www.nncc626.com/2017-03/30/c_129521742.htm.

Coffey, A., Beverley, H., and Paul, A. (2017) Qualitative Data Analysis: Technologies and Representations. Sociological Research Online, 1(1):80–91

Dargan, P., & Wood, D. (2013). Novel psychoactive substances: classification, pharmacology and toxicology. Cambridge: Academic Press.

DEA. (2016). Counterfeit prescription pills containing fentanyls: a global threat. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/docs/Counterfeit%2520Prescription%2520Pills.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2018.

Eck, J. E., & Gersh, J. S. (2000). Drug trafficking as a cottage industry. Crime Prevention Studies, 11, 241–272.

EMCDDA. (2015). EMCDDA–Europol joint report on a new psychoactive substance: 1-phenyl-2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-1-pentanone (α-PVP). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

EMCDDA. (2016). EU drug markets report: in-depth analysis. Luxembourg: EMCDDA–Europol Joint publications.

EMCDDA. (2017). High-risk drug use and new psychoactive substances. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

EMCDDA. (2018). EU drug market report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

EMCDDA, & Eurojust. (2016). New psychoactive substances in Europe: legislation and prosecution—current challenges and solutions. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Fan, B. (2008). Caffeine abuse in Shanxi Province. Journal of Shanxi Police Academy, 16, 4.

Fang, Y. (2011). Research of the anti-drug legal (1950-1952). (Doctoral thesis), Southwest University of Political Science and Law, Chongqing.

Frank, V. A., Bjerge, B., & Houborg, E. (2008). Drug policy: history, theory and consequences. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

Goode, E. (1989). Drugs in American society. New York: Knopf.

Gordon, S. M., Forman, R. F., & Siatkowski, C. (2006). Knowledge and use of the internet as a source of controlled substances. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(3), 271–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2005.08.013.

Hao, D., and Zhao, W. (2012). The development and responses of new drugs related offenses. Study and Exploration, 6, 84–87.

Hughes, B., & Winstock, A. R. (2012). Controlling new drugs under marketing regulations. Addiction, 107(11), 1894–1899. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03620.x.

INCB. (2018). Report of the international narcotics control board for 2018. New York: United Nations Publications.

Kavanagh, P. V., & Power, J. D. (2014). New psychoactive substances legislation in Ireland perspectives from academia. Drug Testing and Analysis, 6(7–8), 884–891.

King, L. A., & Kicman, A. T. (2011). A brief history of ‘new psychoactive substances’. Drug Testing and Analysis, 3(7–8), 401–403.

Lavorgna, A. (2014). Internet-mediated drug trafficking: towards a better understanding of new criminal dynamics. Trends in Organized Crime, 17(4), 250–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-014-9226-8.

Liang, B. (2005). Severe strike campaign in transitional China. Journal of Criminal Justice, 33(4), 387–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2005.04.008.

Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy. Dilemmas of the individual in public service. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Magnani, R., Sabin, K., Saidel, T., & Heckathorn, D. (2005). Review of sampling hard-to-reach and hidden populations for HIV surveillance. AIDS, 19, S67–S72.

Mion, G., & Villevieille, T. (2013). Ketamine pharmacology: an update (pharmacodynamics and molecular aspects, recent findings). CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics, 19(6), 370–380.

Nelson, L., & Schwaner, R. (2009). Transdermal fentanyl: pharmacology and toxicology. Journal of Medical Toxicology, 5(4), 230–241.

Ni, X., & Yuan, C. (2014). How local government campaign-style governance become routinized? A case study for special action. Journal of Public Administration, 2, 005.

Office, L. R. (2017). Changzhi yearbook. Taiyuan: Beiyue wenyi Publisher.

Ouyang, J. (2010). Strategy principle and the maintaining state: the study on the township government between bureaucratization and rural society. (Doctoral thesis), Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan.

Phillips, D. L., & Clancy, K. J. (1972). Some effects of ‘social desirability’ in survey studies. American Journal of Sociology, 77(5), 921–940.

Potter, P. (2013). China's legal system. Cambridge: Polity.

Qin, Z. (2008). A study on changes of new drugs related crimes and responses. Journal of Political Science and Law, 25, 70–74.

Qin, Z. (2011). The characteristics and development of synthetic drug offences. Journal of Chinese People’s Public Security University, 6, 124–130.

Quinney, L., Dwyer, T., & Chapman, Y. (2016). Who, where, and how of interviewing peers: implications for a phenomenological study. SAGE Open, 6(3), 2158244016659688.

Reuter, P. (2011). Options for regulating new psychoactive drugs: a review of recent experiences. London: UK Drug Policy Commission (UKDPC).

Sadler, G. R., Lee, H. C., Lim, R. S. H., & Fullerton, J. (2010). Recruitment of hard-to-reach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nursing & Health Sciences, 12(3), 369–374.

Schurmann, F. (1971). Ideology and organization in communist China. California: University of California Press.

Scott, C. (2004). Regulatory innovation and the online consumer. Law & Policy, 26(3–4), 477–506.

Seddon, T. (2014). Drug policy and global regulatory capitalism: the case of new psychoactive substances (NPS). International Journal of Drug Policy, 25(5), 1019–1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.03.009.

Sun, S. (2016). Investigation report on major cases of drug crime in Tianjin in 2010–2014. (Master’s thesis), Sourthwest University of Political Science and Law, Chongqing.

UNODC. (2013). The challenge of new psychoactive substances. New York: United Nations Publications.

UNODC. (2017). United Nations Office on drugs and crime, world drug report 2017. New York: United Nations Publication.

UNODC. (2018). United Nations Office on drugs and crime, world drug report 2018. New York: United Nations Publication.

van Amsterdam, J. G. C., Nabben, T., Keiman, D., Haanschoten, G., & Korf, D. (2015). Exploring the attractiveness of new psychoactive substances (NPS) among experienced drug users. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 47(3), 5. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2015.1048840.

Werse, B., Benschop, A., Kamphausen, G., van Hout, M.-C., Henriques, S., Silva, J. P., . . . Felvinczi, K.. (2018). Sharing, Group-Buying, Social Supply, Offline and Online Dealers: how Users in a Sample from Six European Countries Procure New Psychoactive Substances (NPS). International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–15.

Williams, T. T. (1990). The cocaine kids: The inside story of a teenage drug ring. Boston: Da Capo Press.

Xiao, K. (2018). On the causes for extension of methcathinon in a city of Shanxi Province and the countermeasures. Journal of Guangxi Police College, 5, 4.

Xu, X., Mao, Z. M., & Halderman, J. A. (2011). Internet censorship in China: where does the filtering occur? Paper presented at the International Conference on Passive and Active Network Measurement. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-19260-9_14.

Yin, H., Zhang, F., Li, L., Su, G., Shi, Q., Jia, Z., & Zhang, Z. (2018). Survey data of methcathinone abuse in 261 cases of Changzhi District. Herald of Medicine, 4.

You, Y., Deng, Y., & Zhao, M. (2017). Research on third generation drug: growing trend assessment, bottleneck of regulation and countermeasure of NPS. Journal of Sichuan Police College, 29, 97–102.

Zhang, Q. (2013). Research on promotion mechanism of tertiary industry development to regional economic transition of resource-based region. (Doctoral thesis), China University of Geosciences, Beijing.

Zhang, S., & Chin, K. l. (2003). The declining significance of triad societies in transnational illegal activities. A structural deficiency perspective. British Journal of Criminology, 43(3), 469–488. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/43.3.469.

Zhao, M. (2019). The illicit supply of new psychoactive substances within and from China: a descriptive analysis. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 0306624X19866119.

Zhou, X. (2008). Collusion among local governments :the institutional logic of a government behavior. Sociological Studies, 06, 22.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all interviewees for their collaboration with the research project on which this paper is based.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, M. New Psychoactive Substances and Law Enforcement Responses in a Local Context in China—a Case Study of Methcathinone. Asian J Criminol 15, 267–284 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-020-09315-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-020-09315-2