Abstract

This paper to the 2016 Beijing meeting of the Asian Criminological Society is the first of two lectures on the theme of The Silk Road of Restorative Justice. The second is the annual lecture of the European Forum for Restorative Justice held jointly with the Asia-Pacific Forum for Restorative Justice in Milan (Braithwaite 2017). This first paper opens the idea of restorative justice as a way of thinking that flows back and forth along the Silk Road with a special focus on the development of relational, republican, and feminist thought in ancient and modern China and Persia. Both contemporary China and Iran are left today with quite a universal yet modest national policy of support for restorative justice. Some co-optation of restorative justice by the state and disengagement from it by many key justice professionals are evident in both China and Iran. The second paper argues more normatively for openness to hybridity along the Silk Road. It identifies virtues of being a republican-socialist-capitalist-feminist advocate of restorative justice in light of what we learn along the Silk Road. The unifying message of both papers is that excellence in restorative justice is nurtured by travelling many roads in search of helpful hybrids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The plan of this paper is first to consider the thought of Confucius as a traveller along the Silk Road (see Fig. 1) that enabled the flow of ideas and trade from Western Europe and North Africa to East and South Asia from around five centuries before Christ. This was also the time when Cyrus the Great expanded the Persian Empire west into Europe, south to Egypt and east to Afghanistan. We connect this to a history of mediation and restorative justice in China, then Persia and modern Iran. Then we consider the history of women’s rights along the Silk Road, followed by the history of forgiveness as an example of a restorative justice value that resonates at both ends of the Silk Road and in between (but less so in the West). Finally, we consider republican political thought conceived as azadi (freedom as non-domination) in Iranian jurisprudence and in Sun Yat Sen’s republican constitution that Mao Zedong initially embraced in China. We argue that today’s travellers from China to Iran can learn lessons about the challenges of struggles for justice and against the domination of women, just as historical travellers along the Silk Road learned lessons of this kind.

Trading routes used around the first century CE centred on the Silk Road. The routes remain largely valid for the period 500 BCE to 500 CE (source: ancient History Encyclopedia http://www.ancient.eu/image/146/)

Confucius

The philosopher whose restorative thought most influentially travels the Silk Road is Confucius. Confucius believed in healing and reconciliation rather than punishment and litigation. He was a campaigner against capital punishment. There is a good argument for healing as the most fundamental of restorative values (Weitekamp and Parmentier 2016) and for the centrality of the idea that restorative justice is relational justice, its essence as relational reconciliation (Llewellyn and Philpott 2014) especially in Asia (Liu 2016; Liu 2017).

Relational justice depends on reciprocity between citizens. Until the arrival of Jesus Christ and Mohammad, Confucius was the most influential communicator of the most widely spoken principle of reciprocity;Footnote 1 some would say the first principle because it is called The Golden Rule. This is ‘Do unto others as you would have then do unto you’ (Csikszentmihalyi 2008). The Confucian principle shu (‘Do not impose on others what you yourself do not desire (Analects, XV. 24)’) found its way into ancient Greco-Roman religion and philosophy (Berchman 2008), Jewish (Singer 1963), Christian (Chilton 2008), and Muslim (Homerin 2008) scriptures and is also found in Hindu (Klostermaier 2007; Davis 2008; Bakker 2013) and Buddhist (Scheible 2008; Hallisey 2008) thought. Some argue that a variant of the Golden Rule may have been taught in ancient Egypt before Confucius (Hertzler 1934). If true, this would not change our contention that the most influential teachers of the Golden Rule were Confucius, then the Greek philosophers, then Jesus Christ, then the Prophet Mohammad. The teaching travelled back and forth building social capital along the Silk Road, enabling the possibility of business contracting, peaceful co-existence, and trade from the far East to the West.

The most fundamental (and quantitatively most recurrent) concept in Confucian thought is ren. When Confucius was asked the meaning of ren, he said ‘Ren means loving others’ (Liu and Palermo 2009:49). Confucius saw ren as the spirit of the second most recurrent concept in Confucian writing, li, which has had many meanings, but came to mean the harmonious ordering of society (Liu and Palermo 2009: 52). It can also be read as an ethical code that averts what should be a last resort—fa or law and punishment. Li can therefore be read as the opposite to anomie or normlessness (anomia—absence of norms—in the ancient Greek). In terms of responsive regulatory theory, li can be read as moral persuasion that is presumptively preferred to the last resort of the blunt tool of law enforcement. ‘Since the time of the Western Han Dynasty (202 CE–9 AD), the combination of li and fa, with li dominating, has been the most important feature of the Chinese legal tradition’ (Liu and Palermo 2009: 53). Likewise, persuasion (including restorative justice) dominating punishment has been the most important feature of responsive regulatory theory (Braithwaite 2002).

De Zhu Xing Fu means that de, or education, is the major approach in the administration of law, while xing, or punishment, is only a supplemental measure. Another form of this expression is Chu Li Ru Xing; that is, only when li does not resolve the problems is punishment used (Liu and Palermo 2009: 54).

Again, this corresponds to the pyramid of regulatory strategies of responsive regulation in Fig. 2, where the presumptive prescription is to start at the base of the pyramid and work up. The Confucian preference for mediation over litigation grounded Chinese investment in mediation programs with a spirit of ren that enabled the harmony and order of li from ancient times to the present.

The problem with Confucianism is that it evolved during some of the many extremely patriarchal periods of Chinese history. This allowed harmony to be co-opted as a tool of gendered domination by national and family patriarchs. This paper opens up the suggestion that this challenge of domination by harmony continues to plague the justice of restorative justice along the Silk Road today. That is why we argue for a republican-feminist synthesis of restorative justice advocacy in The Silk Road of Restorative Justice II. In this paper, we do point to Genghis Khan, Mao Zedong, and Sun Yat Sen as towering historical figures of Chinese empire who do introduce some important and fertile feminist or republican contestation of uncontested patriarchal harmony.

Republicanism is conceived here in the way found in the work of Philip Pettit (1997). It means an architecture of governance to protect people from domination through checks and balances and a rule of law. It conceives freedom from domination as the important kind of freedom to pursue. Feminism is conceived here as the politics of guaranteeing women (and all gendered identities) freedom from the kind of domination by patriarchs that held appeal to Confucius.

A Short History of Mediation and Restorative Justice in China

China has the largest and perhaps the most diverse mediation programs in the world (Braithwaite 2002; Cloke 1987). People’s mediation is the most massive program among them. It is aimed at civil conflicts yet often deals with serious crimes of domestic violence and some other crimes that the state does not want to overwhelm the courts. In 2014, the number of cases that entered People’s mediation was 9.3 million, while civil cases flowed in the courts that year were only 8.3 million (China Statistical Yearbook 2015). People’s mediation was a pioneering practice which emerged in the wake of the peasant movement led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) (Zhou 2012). It started as a tool of the CCP’s ‘mass line’ policy to prioritize the needs of the rural poor to obtain support for settling disputes and to help sustain its own political regime (Mo 2009; Lubman 1967). However, during the Cultural Revolution, people’s mediation was labelled counter-revolutionary because it blurred the boundaries between different social classes and ignored the protection of working class interests (Hong 2011; Glassman 1991). The formal criminal justice system was completely destroyed, and people’s mediation was also abolished in the process of upheaval.

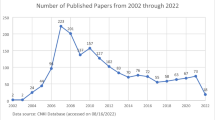

After prolonged stagnation and a sense of despair among the Chinese people, people’s mediation was re-affirmed and became valued again in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when China implemented the ‘open-door’ policy and entered an era of rapid economic development (Clarke 1991). As the social, economic, cultural, and political circumstances under which people’s mediation functioned changed dramatically, it faced unprecedented challenges. Its popularity experienced ups and downs (Zhang 2013, Wu 2013; Hu and Zeng 2015), as seen in Fig. 3. Statistics from the China Statistical Yearbook (1982–2015) display that for around 30 years, people’s mediation fell and rose in a rough ‘U-shaped’ trend. People’s mediation enjoyed high favour during the 1980s. Then it declined from 7.4 million in the early 1990s to 3.1 million in 2002. Since then, the number of disputes settled by people’s mediation has grown substantially, peaking at 9.4 million at the end of 2013 with the launch of the People’s Mediation Law by the National People’s Congress in 2010.

People’s mediation is part of the Chinese legal system for resolving grassroots social conflicts outside the Chinese judicial system, including conflicts that often lead to criminality and many conflicts over minor crimes. Historically, we can see that people’s mediation changed from a politicalized ‘mass line’ tool to a mechanism for maintaining social stability and preserving the communist regime. For the sake of political and social stability under pressure of mass incidents of civil protest, a series of ‘top-down’ decisions statistically reversed the downward trend of people’s mediation after 2002. Fieldwork of Yan Zhang in 2016 in a mediation room of a local police station found this ‘mass line’ mechanism is still energetically playing a crucial role in resolving civil disputes and sometimes even criminal ones. For example, people’s mediation is often used to reconcile domestic violence, which in fact is a serious criminal offence and minor business frauds and sometimes frauds that are not so minor. Police were more willing to have cases closed by stakeholders themselves so they could spare more energy for cracking crimes which are considered as top priorities on the governmental agenda. As found in the fieldwork, the tradition of mediating disputes is still flouring among Chinese people. One interesting case involved a middle-aged male who was dragged into the quagmire of a financial conflict and was staying in the mediation room for more than 1 week, proudly said to the researcher that he helped the mediator to get five conflicts resolved during his stay (Yan Zhang’ interview SV003).

Another groundbreaking restorative justice moment for the Chinese criminal justice system was the official launch of nation-wide criminal reconciliation. On March 14, 2012, the 5th Session of the 11th National People’s Congress passed a Decision of the National People’s Congress on Amending the Criminal Procedure Law (CPL) of the People’s Republic of China. It was the first ever comprehensive enactment in China’s Criminal Procedure Law of a criminal reconciliation system. This mechanism legitimized opportunities for reconciling criminal cases that are caused by civil disputes. The criminal cases caught by the law are categorized as crimes stipulated in chapter four and chapter five of the 1997 Criminal Law (article 277). Article 278 stipulates that victims and offenders may reach reconciliation if offenders (1) show sincere remorse for their crimes and (2) receive the forgiveness of the victim(s) following the offender’s compensation, apology, or other measures (NPC 2012). This is the first time that forgiveness has been officially emphasized in the law of China in terms of criminal reconciliation.

Yan Zhang’s fieldwork in China in 2016 showed that most interviews with prosecutors expressed their warm welcome to the restorativeness of criminal reconciliation, especially when they reflect on what is best for society. However, when it comes to practice, prosecutors in China showed considerable inertia in the face of the 2012 restorative reform. One of the interviewed prosecutors simply said that minor criminal cases only need one page of paperwork for him if directly passed to the judge, so why should he waste his time in preparing ten pages for the reconciliation process (Yan Zhang’ interview CJ009). Another prosecutor was concerned that if he made a decision of non-prosecution after the reconciliation, much stricter scrutiny by the senior office would impose on him then he will be at a risk of taking the accountability (Yan Zhang’ interview CJ028). The inertia is revealed statistically in Fig. 4 through the percentage of criminal cases that got criminal reconciliation in all procuratorates from 2008 to 2013 in Chongqing. The average rate of reconciliation was 2% and there was no increase after the 2012 CPL was passed.

Li (2015) has argued that the agenda of the Communist Party in so wholeheartedly committing China to restorative justice was fear that ‘strike hard’ policies in the past had kindled defiance. So restorative justice was seen as a tool to placate such resistance by creating a more harmonious justice system (Liu et al. 2012). China is often, with some justification, perceived as a society where the separation of powers is a doctrine that has little leverage. Yet our findings here reveal prosecutors rather effectively resisting a very clear directive from the centre, from the Communist Party, to create a more harmonious society by using restorative justice. Prosecutors are referring cases to restorative justice much less widely than in the policy intent articulated by the central organs of the Communist Party. Contrary to the edicts of both Confucius and the Communist Party, prosecutors are rather effectively showing their independence by insisting on fa in preference to li.

An Even Shorter History of Restorative Justice in Iran

Modern Iran shares with China a recent history of ‘strike hard’ criminal justice policy. While China accounts for most of the world’s executions, Iran has the second highest absolute number. These are the two societies with the highest rates of capital punishment per capita today (Hood and Hoyle 2015: 172). Like China, Iran is currently looking to reduce capital punishment and has a top-down policy to dramatically expand criminal mediation. Article 1 of the Code of Criminal Procedure Reform Act of 2013 (with 2015 amendments) guarantees victims of crime a right to mediation and rights to forgive in ways that transcend victim rights in western law.Footnote 2 The new law combines this with victim rights to reparation, to ‘medical-emotional’ services, to access to a lawyer, to ‘confidentiality of the victim’s identity’, and more (Ahmadi 2016). All this is administratively facilitated by the Conflict Reconciliation Councils Act 2015, which empowers more than 10,000 local mediation councils that cover the country.Footnote 3

Victim reparation and support rights are adjudicated first (and speedily compared to the west) to a civil standard of proof based on the philosophy that the law’s first duty is to stem the suffering of the victim. Then criminal adjudication proceeds more slowly and carefully. This seems a potentially fertile radical legal reform from a restorative perspective. It is worthy of detailed empirical evaluation. In western law, particularly with complex corporate crimes or war crimes, victims can be left to suffer for many years before a court decides criminal responsibility. In Iran, activists and scholars are engaged with a promising social movement to give these top-down law reforms restorative justice content bottom-up. While the reform opens the door to victims requesting the settling of their criminal case primarily through mediation rather than criminal prosecution, the outcomes recommended in any restorative mediation must be approved by a judge.

As in China, Iran’s contemporary restorative justice reform is in part a renewal of ancient traditions that actively encouraged mediation and forgiveness in serious criminal matters, including homicide, actually particularly with homicide, because of fear that disharmony between tribes and families could lead to blood feuds of unstoppable violence.

A paradox of the politicized closure of secular courts and replacement with shariat (Islamic) courts after the Islamic Revolution in 1979 was an energizing of mediation and ancient shora (consultation) traditions. This was necessary when courts were closed and nothing had yet been established to replace them. Traditional mediation helped manage complaints that were beyond the capacity of a disintegrating post-revolution judiciary. The regime noticed that mediation’s speedier, cheaper resolution of cases than the Shah’s (king’s) courts had enabled was popular, especially in rural areas where people wanted to re-connect to tribal and shari’a traditions. Mediation was therefore legitimating for the revolutionary legal system. At all stages of Iranian history, traditional mediation had an important role. It always fitted many of the definitional features of what is today called restorative justice. Even under the secularizing rule of the Pahlavi dynasty (1925–1979), ‘justice houses’ were established throughout Iran, particularly to deal not only with disputes concerning the regime’s rural land reforms but also other disputes and crimes. In a sense, each transformation in Iranian legal history created a space for re-invigoration of Iranian restorative traditions of various kinds but particularly neighbourhood mediation by ‘greybeards’ or ‘whitebeards’ (Mahmoudi 2006; Miller 1964).

Interviews in Iran in 2016 revealed one similar motivation for the 2013 Iranian and 2012 Chinese Criminal Procedural Law, respectively. This was to moderate defiance stoked by strike hard policies and to promote political harmony. Also, as in China, John Braithwaite’s research interviews in Iran in 2016 revealed that prosecutors successfully pushed back against the 2013 law reforms to push a large proportion of criminal cases to mediation. There seemed to be great variation among prosecution offices in the extent to which prosecutors embraced the concept of restorative justice. Some enthusiastically did. Most continued on the traditional formal criminal adjudication track of sending cases straight to trial in ways they had done before 2013. As in China, it seemed personally risky to them to empower citizens with restorative mediation that might result in citizens acting in controversial ways or recommending something controversial. Many prosecutors calculated that if they just sent the case to the judge, what happened was the judge’s problem, but if they sent it to restorative justice, they could be blamed. One prosecutor described the challenge as a fear of the unfamiliar. Another said that prosecutors resisted restorative justice simply because this took more of their time than simply passing responsibility on to the court (where it took up an even greater amount of the court’s time). Yet another described the Iranian legal system as abusing mediation as no more than a case management path to increasing the efficiency of the system through diverting adjudication from the courts, without providing the more moderate funding needed for restorative justice to work well.

Women’s Rights Along the Silk Road

Modern Iran is an exceptionally inhospitable society to women’s rights of a variety of important kinds. There are no female judges in Iran. Notwithstanding this fact, restorative justice is providing a path where women become de facto judge-mediators on a large scale. In contradistinction to traditional law that requires Iranian judges to be male, all mediation councils affiliated with prosecutors’ offices are mandated to have at least one female mediator and during John Braithwaite’s 2016 fieldwork, he encountered one mediation council where 8 of the 20 of the mediators were women. While Islam is interpreted in Iran to mean that women cannot be judges, they are, sometimes reluctantly, accepted as restorative justice mediators.

We see the same phenomenon of the greater possibilities for feminizing the administration of justice through institutions of mediation than through the common law courts in South Asia. Panchayats (assemblies of elders) were a key ‘village republicanism’ reform advocated by Mahatma Gandhi. Rajiv Gandhi picked it up to become the 73rd Amendment to the Indian Constitution in 1993. These reforms slowed greatly after his death, but Sonia Gandhi did reenergize panchayat reform in the second decade of the twenty-first century. This included a push to shift panchayat power from corrupt local government apparatchiks further down to very local village assemblies of the district-block-village hierarchy of panchayats. This has been associated with village-level panchayats taking control of the largest anti-poverty program the world has seen. It operates in 778,000 Indian villages. This is the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. It is a ‘right to work’ reform that seeks to guarantee 100 days of publicly funded work every year, mostly on water conservation projects in rural areas, to the poorest people of India. It too has been exposed to critiques of its corruption by the Indian government’s own Comptroller and Auditor General and media (Times of India 2013), social audits by Indian state governments, as well as critical analyses by academic researchers (Shankar 2010; Nagarajan et al. 2013).

There is reason for some feminist and restorative hope for the village panchayats, as opposed to the higher-level panchayats that have also been riddled with corruption and maladministration in Nepal, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Hope for the village-level panchayats persists notwithstanding formidable problems revealed by audit contestation. The hope is that the checks and balances that the audit society can occasionally deliver can be complemented with taking India back to the checks that assembly democracy might deliver in a village.

The Indian Constitution requires one third of elected panchayat voting members to be women and proportional representation of scheduled castes such as ‘untouchables’. This has elevated more than a million women to become elected representatives for the first time. Probably, that has contributed to an outcome for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act of 54% of the days worked going to women and 39% to scheduled (lowest) castes or adivasi (‘tribal peoples’) in 2013.

The republican Constitutional and law reforms in Nepal that followed from the peace agreement ending the Maoist insurgency in 2006 also guaranteed that one third of panchayat members must be women (Braithwaite 2015a). It is (comparatively) easier for state law and state administration to enforce the feminization of local justice than it is to feminize the more entrenched power of national judiciaries. That is a great lesson of contemporary Asian experience along the Silk Road from Iran to India and Nepal. It is little understood in the West.

Elected village assemblies are not a remote form of representative democracy; one chats with one’s elected member on a daily basis in the village. In addition, those elected must deliberatively account to the whole village in a kind of assembly democracy. Mahatma Gandhi hoped that panchayats would assume the functions of courts of law and state police in the villages. This happened with many village panchayats, though only a small minority of them. The contemporary research agenda of some of India’s most distinguished criminologists, such as M.Z. Khan, is to study how justice works in villages where panchayats have seized justice back from the police and courts through village-level restorative justice. These Indian criminologists are interested in reviving ancient Indian nyaya panchayats (village courts), hybridized with learning from the global social movement for evidence-based restorative justice (Khan and Sharma 1982; Latha and Thilagaraj 2013; Thilagaraj and Liu 2017).

In Punjab province of Pakistan, there are also village panchayats that run a kind of restorative justice. Even more interesting have been jirgas in the Pakistan provinces bordering Afghanistan that compete not only with the law courts of the Pakistan state but also with the Shari’a courts offered by the Taliban. In spaces where ordinary people live in constant fear of violence, winning the competition for hearts and minds against the Taliban and ISIS by offering people a form of justice that they feel protects them is politically critical. One response by the Pakistan police has been to establish hybrid state-traditional restorative justice Muslahathi (reconciliation) committees inside the heavily fortified walls of police stations. After observing more than 100 of these deliberatively democratic institutions of criminal justice, Braithwaite and Gohar (2014) concluded that they are succeeding in interrupting many cycles of revenge killing, particularly through their handling of murder cases.

All these South Asian hybridity innovations can and should be criticized for gender inequality. Yet the reformer’s question is which hybrids contribute most to pushing back entrenched gender inequalities? Panchayats that resolve village legal conflicts may be dominated by traditional male village leaders, yet the percentage of judges who are female in Indian state courts is much lower than with panchayats. With jirgas, innovations with women’s jirgas in which ‘whitehairs’ replace ‘whitebeards’ have both promise and limits. The more fundamental point about jirgas is that they can make a contribution to preventing the Taliban from seizing local power, an outcome that is opposed to women’s interests.

Finally, data from Lawrence Sherman and Heather Strang’s RISE experiment in Australia suggest that restorative justice as a form of deliberation can structurally benefit women. In criminal cases randomly assigned to courts or restorative justice, women speak for a lower percentage of the time and report more discrimination on the basis of age, income, race, or sex in cases randomly assigned to Canberra courts compared to cases assigned to restorative justice (Braithwaite 2002: 152–3).

The journey of women’s rights along the Silk Road makes for a radically different narrative than the western narrative of feminist history that privileges first wave feminism as something that culminates roughly a century ago with many western states granting votes to women and second wave feminism as something that rises again in the 1970s. The rise of communist political parties and regimes, which along the Silk Road produced transformations to communism between the two western waves of feminism that affected much larger numbers of women than western social change, was comparatively much more supportive of women holding positions of power than western regimes of their day. This was true of Mao’s China. Afghanistan is an instructive case study of the modernist distorted western lens of the history of women’s rights. Laura Bush sought to co-opt feminism to support for her husband’s decision to invade Afghanistan in 2001 with the appeal that this would liberate the women of Afghanistan from partriarchal oppression. While liberation has been limited, there can be no doubt that the regime in Afghanistan that currently clings to power, however tenuously, is granting greater access to women’s rights than the Taliban regime that preceded it. Yet far greater progress on women’s rights was made under the communist regime that ruled Afghanistan from 1978 to 1992 than any progress made this century under the NATO-backed regime. Much later, Maoists coming to power after 2006 in Nepal are associated with a surge in women’s rights (Braithwaite 2015a).

A longer-term view of women’s rights along the Silk Road reveals more regress than progress and far greater and earlier empowerment of women in many spaces than existed after second wave feminism in the west. Foundational Marxist Friedrich Engels (1884) in The Origin of Family, Private Property and the State was one of the first to link the coercive acquisition of property to ‘the world historical defeat of the female sex’. Riane Eisler’s (1988) influential research concluded that feminine rule was common in the ancient world until Indo-European (Ayrian) and Semitic men on horses swept down from the north to south, west, and east during the bronze age 6,000 years ago, using the swords forged by bronze, to replace feminized rule with patriarchal governance. She argues from the archaeological record that conquest by men on horseback with swords was conducive to a dominator model of governance as the kind that was most likely to survive. A dominator model that replaced a partnership model was also associated with the rise of the institution of slavery, particularly the sexual slavery of women, in an archaeological record that links this to armed invasions (Eisler 1988: 49). Hence, even when important female rulers such as Cleopatra in Egypt survived beyond the bronze age, they did so by adopting the dominator model of conquest by the sword.

One hypothesized paradox of the Silk Road comes 5,000 years later when Genghis Khan (1162–1227 AD) is touted by revisionist Mongolian historians as an incipient feminist who ‘suffered a bad press’ in the West. Weatherford’s (2011) book on the subject assembles the historical evidence for this in the most evocative way. But these authors are particularly indebted to conversations with our ANU colleague Narantuya Ganbat, whose grandmother was one of the most influential women in the history of the Mongolian Communist Party, for this revisionist Mongolian take on the history of feminism.

As Genghis Khan organized men to ride West and South to conquer, he left women behind in charge of many powerful domestic administrative roles in Mongolia. The Great Wall of China still stands as a monument to the awe in which one of those powerful female Mongolian rulers was held. When he conquered large empires, including China, Persia, and what became the Mughal Empire traversing beyond contemporary Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, he married daughters and later granddaughters and other more distant relatives of his Borijin clan to the kings of those empires. These female relatives came to rule these great empires as queens when their husbands died. In arranging the marriages Genghis Khan would enshrine political equality between husband and wife into the marriage contract and then send the husband off to lead a battle in a difficult front. When husband kings were fighting and when they perished, Genghis Khan’s relatives took over as empresses of empire. These female daughters and descendants survive ideationally less for their role in the history of feminism than for their ongoing presence in the artistic canon venerated in the West: the Taj Mahal constructed in honour of one of them, the Great Wall of China, Puccini’s Turandot, in Goerte, Schiller, Chaucer, and Milton (Weatherford 2011).

Together, these Mongol queens, through free trade among them along the Silk Road, wove together not only the largest empire the world has ever seen but also the world’s first truly international empire. Genghis Khan may have been history’s greatest mass murderer in terms of the proportion of the planet’s population he was responsible for slaughtering. Nevertheless, the legend of the international cooperation of his daughters is also a legend of a teenage girl being able to travel the length of the Silk Road carrying her family’s most valuable jewellery without being robbed. We will argue that there is a civilizational paradox of empires created by terrible crimes against humanity creating pacified spaces where feminist, republican, and restorative ideas have some space to peacefully germinate. This paradox is equally clear in the way western empires of Britain, France, and America today enjoy pacified spaces in which they draw restorative and republican inspiration from the very peoples they genocidally crushed. The most paradoxical iconography of this paradox is the representation on US dollar bills and coins of the peacemaking of the Iroquois Confederation’s republican non-domination. The Iroquois republic’s reconciliation of warring indigenous peoples is represented by a clasped bundle of arrows (Olsen 2006: 215).

The macro-complexity of the history of how women’s rights travel the Silk Road maps onto the complexity of our discussion in the first half of this section on the history of how women’s participation in restorative justice and state justice ebbs and flows along the Silk Road. The problem is the Western lens that simplifies the complexity, preventing the West from learning almost anything about justice from Muslim societies or Communist societies. The next section uses forgiveness as an example of a justice principle that is suppressed in Western justice discourse, including restorative justice discourse. Again, we trace the relevance to justice of forgiveness at the Chinese and Persian ends of the Silk Road.

Forgiveness

For Confucius, forgiveness was a principle of good justice tightly connected to the Golden Rule of relational reciprocity: ‘Those who cannot forgive others break the bridge over which they themselves must pass’ (Confucius 2004: 139). This is also true of ancient Persian thinking about forgiveness at the opposite end of the Silk Road. We will see later that the Persian Emperor Cyrus the Great, who spread the Persian Empire down across Egypt and beyond and up across Eastern Europe, famously freed and reconciled with the former slaves who had been captured in wars. In the case of the Hebrew slaves freed in Babylon, Cyrus financed their return to Jerusalem and even funded the rebuilding of their holiest temple that had been destroyed in the previous conflict (Briant 2002).

For Iran today, in another paper, Farajiha and Braithwaite (2017) argue that while there is truth in the existence of extremes of punitiveness in Iranian justice, including occasional (actually infrequent) resort to cutting off the hands of thieves, forgiveness is also deeply structured into Iranian law. Farajiha and Braithwaite (2017) argue that forgiveness is an Islamic principle enshrined in Iranian law that can trump punitive shari’a rules. In the context of Iran, forgiveness is the principle, criminal law the field, where there is space for anti-domination principles to trump the dominations of Iranian politics and oppressive Iranian rules at least some of the time. There are respects in which Iranian law takes a stronger stand against domination than western law. For example, once alimony to be paid by a husband to a wife and children is settled in a divorce, failure to pay it is a crime in Iranian law. This is because such failure can dominate the woman and her children. In western law, such a failure triggers only a civil family law dispute.

Farajiha and Braithwaite (2017) discuss four tiers to forgiveness as a principle that can trump punitive rules in Iranian criminal jurisprudence. The first is mercy, compassion, and azadi (freedom as non-domination) as principles that can trump shari’a rules. The second is empowerment of victims with a right to forgive in a much wider range of circumstances than in western law. The third is redemptive forgivability (which has much in common with Brent Fisse’s (1982) principle of ‘reactive fault’). Reactive fault acquits criminal liability when a defendant responds well in terms of repairing harm and preventing recurrence. The fourth is presumptive forgivability, meaning if there is doubt about whether a crime is formally defined to be ‘forgivable’ in Iranian law, presume it to be so until it is clearly proven unforgivable. This is a reform proposal advanced by the University of Shiraz scholar Dr. Ibrahimi as a way of formalizing the presumptive forgivability in the legal reasoning of the Prophet Mohammad (which shari’a judges are expected to emulate).

The purpose of Farajiha and Braithwaite’s (2017) work here is to use Iranian law to open our imaginations concerning techniques that can be deployed, even in difficult circumstances, to foster freedom. The key to this insight are principles of non-domination that are empowered to trump rules that can be dominating. This also becomes the central issue followed up in The Silk Road of Restorative Justice II (Braithwaite 2017).

Western criminal lawyers and restorative justice theorists are wary of giving too much weight to forgiveness as a justice principle because they fear pressuring of victims to forgive when they do not wish to forgive. The argument in Braithwaite’s work, however, is that a victim right to trump punishment by forgiving is important. This right is a more important emergent principle along the ancient Silk Road than an obligation to forego punishment by forgiving. There is much that we can learn today from elements of this wisdom at both ends of the Silk Road. One reason is the view that there is one more important outcome of good criminal justice institutions than crime reduction or justice. That is death. In Australia, for example, aboriginal deaths in custody are not necessarily a lesser problem than aboriginal crime. A good justice system prevents the death of more people. The relevance of this to a justice system that allows a victim right to forgive in a wide range of circumstances is that forgiving people live longer (Toussaint et al. 2012).

Restorative Justice Along the Silk Road

A history of restorative justice along the Silk Road is embedded in each section of this paper so far. We have described the emergence of restorative justice in modern history in China and Iran at each end of the Silk Road. We have described how this modern restorative justice is influenced by more ancient traditions of restorative justice in Persia and China. We have described how ancient principles such as the Golden Rule of reciprocity, relational justice, and forgiveness echo along the Silk Road from China to Persia, from Confucius to Cyrus to the Greek philosophers to Jesus Christ and Mohammad. We have described how more restorative forms of justice such as panchayats in the Gandhian village republican vision, and indeed modern restorative justice, can create greater spaces for women’s rights than formal state justice (Braithwaite 2002).

Just as there is no unidirectional civilizational progress along the history of the Silk Road in women’s rights, likewise, there is no unidirectional evolution of restorative ideas and practices but rather ebbs and flows of the restorative justice project across space and time. A comparative sociological imagination and an historical imagination can help us to see that there is no inevitability to the suppression of women’s rights or the suppression of restorative justice. Equally, they help us to see that struggles for them must confront entrenched power and deploy deft ju-jitsu that uses entrenched forms of power against themselves.

All along the Silk Road can be found instructive survivals of traditions that embody empowering restorative practices from which Western audiences can learn from the East and vice versa. An example discussed previously in the pages of this journal from the western hills of Nepal is the Kachahari, which means street forum (Braithwaite 2015b). Westerners might think of it as a speakers’ corner institution, but the focus of the speech is not on a political issue of the day but on a personal injustice one has suffered. Kachahari can be initiated by any citizen who stands and speaks at a well-known meeting place. This attracts a crowd and eventually the wisest community elders. So, the initial process is an opportunity for anyone to articulate injustice to call unresponsive justice processes, dominating male officials or indigenous leaders to account for their failure to give them justice. Elders are expected to respond by offering to work with them to resolve the matter. As such, this is an institution that disadvantaged people can use restoratively to call male power to account to contest an appearance of harmony that is a reality of domination.

Hence, there is a lot of local contesting of patriarchal harmony along the Silk Road that can manifest restorative values, as Kachahari does. Robust republican freedom as non-domination can benefit from a combination of such bottom-up local contestation of abuse of power with top-down checks and balances in a separation of powers.

A Short History of Republicanism Along the Silk Road

The tablet of Cyrus the Great of Persia in the sixth century BC is said to lay down the first codification of human rights law, including a right to protection from slavery that was put into place, as famously recorded in the bible, by freeing Hebrew slaves. More broadly, Cyrus liberated the underclass of his empire (Xenophon 2002: 5). Codification of other kinds of law goes back much further in this region to the Code of Hammurabi carved in stone in Babylon in 1754 BC. Persian law became shari’a law after the Arab Muslim conquest of the Persian Empire. Then it became heavily overlaid with the French republican tradition of civil law after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Hence, republican elements enter the law through both ancient and modern paths. Shari’a principles like azadi (freedom as non-domination) regained prominence with the transition to an Islamic Republic in 1979 that did indeed have both Islamic and republican elements.

This parallel is not so clear in the history of China. The ideal of an independent judiciary and prosecutor suffered major reversals during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s. Only a degree of independence has been restored since. Sun Yat Sen, the founder of the Chinese republic in 1912, is still a revered figure in China. He was a great modern contributor to republican thought on the separation of powers. Sun Yat Sen’s Constitutional vision in the former Republic of China, and still in the Constitution of Taiwan, is just one path to invigorating checks and balances. His fourth branch beyond the judiciary, the legislature, and the executive was an examination branch that protected the integrity of the first three branches from cronyism by ensuring that one could only achieve high positions in other branches by beating less able candidates in exams. The fifth branch was an accountability yuan. A regulatory branch can be elected for a single term to oversee impeachment in the three core branches, an anti-corruption commission to expose corrupt judges and central bankers, an audit office, a human rights commission, an election commission, ombudsman, a commission to regulate the media, and other checks and balances such as regulation of abuse of power by NGOs. The 1997 People’s Constitution in Thailand adapted Sun Yat Sen’s idea of such an accountability branch, but it was dismantled after Thailand’s 2006 military coup.

In the West, it is common to think of Montesquieu (1977) as the only constitutional thinker who contributed a fundamental foundation to the separation of powers. Even more so, Greeks, Romans, Northern Italians, and Americans dominate the Western image of innovators in republican political thought. The only point made here is that one needs to continue further east along the Silk Road to see the full range of innovation in republican political thought from Persia to China. A Sun Yat Sen style of independent accountability branch of governance is something many corroding Western democracies might benefit from where they only open to looking east.

Conclusion

In The Silk Road of Restorative Justice II, Braithwaite (2017) will argue that a particularly fundamental kind of contestation is of rules by principles. Principles contesting rules is one of the most important forms of contestation of fa by li. Contestation of rules by principles is a path to resolving the challenges of domination discussed in this article. In particular, Braithwaite (2017) will advocate a law reform whereby restorative justice is a legal principle that can trump sentencing rules and guidelines. This means that, as in many of the circumstances provided for freedom (azadi) to trump rules in Iranian law, the principles of forgiveness and freedom from domination should be able to trump proportionality in punishment.

This paper has argued for invigoration of local justice by keeping the flow of ideas about restorative justice open along the Silk Road. It has argued for republican contestation and feminist contestation of those ideas. That contestation is helpful for creating new justice hybrids and new constitutional architectures within which restorative justice and women’s rights might better flourish. We have called harmony into question as a core restorative justice value because of the way it has been co-opted to projects of state domination along the Silk Road. Yet this is no argument for discarding relational justice and forgiveness that have such a vibrant history along the Silk Road. Finally, the article shows that the unusually universalist and potent top-down commitment to restorative justice that we find to be emergent in Iran and China in recent years may achieve limited change. This is because the social movement for restorative justice has not dissuaded the entrenched power of the legal profession from resisting restorative reform.

Notes

Reciprocity, mutuality, and harmony were central to Confucian ways of seeing: [Analects XXIII] Tsze-kung asked, saying, ‘Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one’s life?’ The Master said, ‘is not RECIPROCITY such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not do to others.’ (Confucius 1974: 123).

In John Braithwaite’s interview (051606) with Grand Ayatollah Musavy Ardabily (who was in recent times head of the Iranian Judiciary), he qualified it by summarizing the detailed and complex rules regulating forgiveness in this way: ‘Yes you also have a right to forgive as a victim but not for all types of crime and not in all circumstances.”’ Yet ‘Forgiveness is the priority above everything…Forgiveness is desired by God. You are closer to God”’s course, to God’s will when you forgive.’ He went on to explain why forgivability for murder was needed in order to maintain peace on earth, but forgiving rape was not possible on earth because of the threat it involves to God’s moral order.

In Lorestan Province, for example, with a population of less than one million, there were 270 local mediation councils during our 2016 fieldwork with 1700 trained mediators (meeting 051614 with Lorestan judiciary and mediation leadership).

References

Ahmadi, A. (2016). The rights of victim in the Iranian Code of Criminal Procedure Act 2013. Review of European Studies, 8(3), 279.

Bakker, F. L. (2013). Comparing the golden rule in Hindu and Christian religious texts. Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses, 42(1), 38–58.

Berchman, R. M. (2008). The golden rule in Greco-Roman religion and philosophy. The golden rule: the ethics of reciprocity in world religions, London: Continuum, 40–54

Braithwaite, J. (2002). Restorative justice and responsive regulation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Braithwaite, J. (2015a). Gender, class, resilient power: nepal lessons in transformation. RegNet Research Paper, (2015/92)

Braithwaite, J. (2015b). Rethinking criminology through radical diversity in Asian reconciliation. Asian Journal of Criminology, 10(3), 183–191.

Braithwaite, J. (2017 forthcoming). The Silk Road of restorative justice II. Restorative Justice: An International Journal

Braithwaite, J., & Gohar, A. (2014). Restorative justice, policing and insurgency: learning from Pakistan. Law & Society Review, 48(3), 531–561.

Briant, P. (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: a history of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns

Chilton, B. (2008). Jesus, the golden rule and its application. The golden rule: the ethics of reciprocity in world religions, London: Continuum, 76–87.

Chongqing Bureau of Statistics.2009–2014 Chongqing Statistical Yearbook. China Statistics Press

Chongqing People’s Procuratorate. 2009–2014 The annual working report of the municipal procuratorate of Chongqing

Clarke, D. C. (1991). Dispute resolution in China. J. Chinese L., 5, 245.

Cloke, K. (1987). Politics and values in mediation: the Chinese experience. Mediation Quarterly, 17, 69.

Confucius. (1974). The philosophy of Confucius. Trans. James Legge. New York: Crescent Books

Confucius. (2004). Science and spirituality. Trans. Mary Mann. AuthorHouse

Csikszentmihalyi, M. A. (2008). The golden rule in Confucianism. The golden rule: the ethics of reciprocity in world religions, 157

Davis, R. H. (2008). A Hindu golden rule, in context. The golden rule: the ethics of reciprocity in world religions, 146, 161–164.

Eisler, R. (1988). The chalice and the blade

Engels, F. (1884). The origin of the family, private property and the state

Farajiha, M & Braithwaite, J. (2017). Forgivability and the deep structure of iranian law. Forthcoming RegNet Working Paper, Australian National University

Fisse, B. (1982). Reconstructing corporate criminal law: deterrence, retribution, fault, and sanctions. S. Cal. L. Rev., 56, 1141.

Glassman, E. J. (1991). Function of medication in China: examining the impact of regulations governing the People’s mediation committees. The. UCLA Pac. Basin LJ, 10, 460.

Hallisey, C. (2008). The golden rule in Buddhism [II]. The golden rule: the ethics of reciprocity in world religions. London: Continuum, 129–145

Hertzler, J. O. (1934). On golden rules. International Journal of Ethics, 44(4), 418–436.

Homerin, T. E. (2008). The golden rule in Islam. In J. Neusner (Ed.), The golden rule in world religions (pp. 99–115). New York: Continuum Press.

Hong, D. (2011). Research on the changes of mediation system in contemporary China. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Press.

Hood, R., & Hoyle, C. (2015). The death penalty: a worldwide perspective. Oxford: OUP Oxford.

Hu, J., & Zeng, L. (2015). Grand mediation and legitimacy enhancement in contemporary China—the Guang’an model. Journal of Contemporary China, 24(91), 43–63.

Khan, M. Z., & Sharma, K. (1982). Profile of a Nyana panchayat. Delhi: National.

Klostermaier, K. K. (2007). A survey of Hinduism. New York: SuNY Press.

Latha, S., & Thilagaraj, R. (2013). Restorative justice in India. Asian Journal of Criminology, 8(4), 309–319.

Li, E. (2015). Towards the lenient justice? A rise of ‘harmonious’ penality in contemporary China. Asian Journal of Criminology, 10(4), 307–323.

Liu, J. (2016). Asian paradigm theory and access to justice. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 32(3), 205–224.

Liu, J. (2017 forthcoming). The new Asian paradigm: a relational approach. In J. Liu, M. Travers & L. Chang (Eds.), Comparative criminology in Asia. New York: Springer.

Liu, J., & Palermo, G. B. (2009). Restorative justice and Chinese traditional legal culture in the context of contemporary Chinese criminal justice reform. Asia Pacific Journal of Police & Criminal Justice, 7(1), 49–68.

Liu, J., Zhao, R., Xiong, H., & Gong, J. (2012). Chinese legal traditions: punitiveness versus mercy. Asia Pacific Journal of Police &Criminal Justice, 9(1), 17–33.

Llewellyn, J. J., & Philpott, D. (2014). Restorative justice, reconciliation, and peacebuilding. USA: Oxford University Press.

Lubman, S. (1967). Mao and mediation: politics and dispute resolution in Communist China. California Law Review, 1284–1359.

Mahmoudi, F. (2006). The informal justice system in Iranian law. In H. J. Albrecht & U. Sieber (Eds.), Conflicts and conflict resolution in middle eastern societies: between tradition and modernity (pp. 411–456). Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Miller, W. G. (1964). Hosseinabad: a Persian Village. Middle East Journal, 18(4), 483–498.

Mo, J. S. (2009). Understanding the role of people’s mediation in the age of globalization. Asia Pac. L. Rev., 17, 75.

Montesquieu, C. D. S. (1977). The spirit of laws: a compendium of the first English edition. In D. W. Carrithers (Ed.) Together with an english translation of an essay on the causes affecting minds and characters. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nagarajan, H. K., Jha, R., & Pradhan, K. C. (2013). The role of bribes in rural governance: The case of India. Available at SSRN 2246525

National Bureau of Statistics PRC. 1982–2015 China Statistical Yearbook. China Statistics Press

National People’s Congress (NPC). (2012). Criminal procedure law of the People’s Republic of China (2012)

Olsen, E. J. (2006). Civic republicanism and the properties of democracy: a case study of post-socialist political theory. Lexington Books

Pei, W. (2014). Criminal reconciliation in China: consequentialism in history, legislation, and practice. China-EU Law Journal, 3(3–4), 191–221.

Pettit, P. (1997). Republicanism: a theory of freedom and government. Oxford: OUP Oxford.

Scheible, K. (2008). The formulation and significance of the golden rule in Buddhism. The golden rule: the ethics of reciprocity in world religions, London: Continuum, 116–128

Shankar, S. (2010). Can social audits count?. Australian National University, Australia South Asia Research Centre Working Paper, 9

Singer, M. G. (1963). The golden rule. Philosophy, 38(146), 293–314.

Thilagaraj, R. & Liu, J. (Eds.). (2017 forthcoming). Restorative justice in India: traditional practice and contemporary applications. New York: Springer.

Times of India 2013 ‘CAG finds holes in enforcing MNREGA’. The Times of India. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/CAG-finds-holes-in-enforcing-MNREGNarticleshow/21498524.cms

Toussaint, L. L., Owen, A. D., & Cheadle, A. (2012). Forgive to live: forgiveness, health, and longevity. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 35(4), 375–386.

Weatherford, J. (2011). The secret history of the Mongol queens: how the daughters of Genghis Khan rescued his empire. Broadway Books

Weitekamp, E. G., & Parmentier, S. (2016). Restorative justice as healing justice: looking back to the future of the concept. Restorative Justice: An International Journal, 4, 141–147.

Wu, Y. (2013). People’s mediation in China. The Routledge Handbook of Chinese Criminology, 116

Xenophon. (2002). Translated and annotated by Wayne Ambler. Xenophon: the education of Cyrus. Cornell: Cornell University Press.

Zhang, H. (2013). Revisiting people’s mediation in China: practice, performance and challenges. Restorative Justice, 1(2), 244–267.

Zhou, Y. (2012). Study report on the development of the people’s mediation system, www.moj.gov.cn/yjs/content/2012-10/18/content_2787430.htm?node=30053

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Braithwaite, J., Zhang, Y. Persia to China: the Silk Road of Restorative Justice I. Asian Criminology 12, 23–38 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-017-9244-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-017-9244-y