Abstract

Studying public attitudes toward rehabilitation is not a new phenomenon. However, not much research is available on this topic from Asian countries. The present study explores public attitudes among Taiwanese people toward rehabilitation efforts in general, and the Rehabilitation and Protection Act (RPA) in particular. Using a sample of N = 333, we asked Taiwanese residents age d18 and older about their support for the RPA, and their support for rehabilitation initiatives for three types of criminals: drug offenders, violent offenders, and sex offenders. Using a univariate model, we found that only two variables—age and stereotypical knowledge—had a statistically significant effect on whether an individual supported rehabilitation initiatives. Findings also indicate overwhelming support for the RPA and rehabilitation in general. We discuss these findings in a cultural context, and make recommendations for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With about 23 million people living on an island of just 36,000 square kilometers (14,400 square miles), Taiwan is an extremely densely populated country. One of the central issues in Taiwanese society is the increasing crime rate, which is often attributed to this population density, as well as to an increasing gap between rich and poor (Ministry of the Interior of Taiwan; Study of Taiwanese crime trend and its future (in Chinese). Retrieved from http://www.cib.gov.tw/CibSystem/RE_UPLOAD_FILE/2007912191345.pdf). Nonetheless, the rate of violent crime in Taiwan is still relatively low: in 2007, it was about 36.57 per 100,000 people.Footnote 1 Among those convicted, only 15% were violent criminals (Ministry of Justice of Taiwan; Statistics of Justice 2007 Annual Report (in Chinese). Retrieved from http://www.moj.gov.tw/public/Attachment/810161538670.pdf).Footnote 2 But the recidivism rate, by contrast, is a serious issue, especially with drug-related crimes. Footnote 3 According to Taiwan’s Ministry of Justice, the general recidivism rate in 2007 was about 65.2%, and the recidivism rate for use or possession of a drug was 94.3%.Footnote 4 Even leaving aside drug-related crimes, recidivism rates for robberies and thefts were more than 70%.Footnote 5 Compared to the United States, sentences in Taiwan are much shorter. In 2007, about half (49.7%) of prisoners were sentenced to less than 5 years, and on average, inmates served 70% of their actual sentences. Consequently, it is common for drug offenders, robbers, and thieves to go in and out of prison several times during their criminal careers.

In dealing with criminals, Taiwan’s criminal justice system has adopted a rehabilitative perspective drawn from Confucianism and Japanese legal regulations.Footnote 6 Liu (2003) argues, for example, that the Confucian attitude relies very little on law and punishment for maintaining social order. In the Confucian worldview, he explains, the rule of law is applied only to those who have fallen beyond the bounds of civilized behavior. In addition, as Chan (1963) explains, Confucianism promotes the idea that people can be reformed through proper education. Meng TzuFootnote 7 advocated that human beings are born good and possess the ability to do good. Any evil action is the result of an inability to avoid evil external influences. Thus society—in the form of both government and community—must make efforts to restore the original good (Chan 1963).

In 1976, the Taiwanese government instituted the Rehabilitation Protection Act (RPA) to manage released prisoners, parolees, and people sentenced to probation. The goal of the act was to prevent recidivism and maintain social order. The act established the Rehabilitation and Protection Association to handle the business of rehabilitation. The RPA and its association have never received intense scrutiny from the public and politicians. Commenting on the effectiveness of the Rehabilitation and Protection Association, Chow (n.d.) says that lack of community involvement has restricted the effectiveness of its programs. Chow proposes that, to rehabilitate released prisoners, programs must not only give them training but also help them establish their own legitimate social networks. But the key element in transforming ex-convicts into productive members of society is the community’s willingness to accept released offenders.

In 2002, in response to increasing recidivism and the critiques of the Rehabilitation and Protection Association, the Legislative Yuan of Taiwan mandated that the association change its name to the After-Care Association (ACA), and forced county governments to set up local branches to reflect its mission of integrating offenders after their release. One unique point of this mandate is that it requires the ACA to not only manage rehabilitation programs but also recruit, sponsor, and supervise nonprofit organizations and other treatment programs in local communities.Footnote 8 All these efforts were made to encourage local communities to support and help released prisoners in order to further reduce the recidivism rate and maintain social order.

If community members are willing to support the rehabilitation of drug users, the logic goes, they may devote more social power to helping these drug offenders. Thus, a community-based drug rehabilitation program may be a more effective policy choice compared to a program that keeps such offenders isolated from the community. On the other hand, if community members generally hold a punitive attitude toward rapists, for instance, community-based rehabilitation programs may not be an effective policy choice for sex offenders. If policy makers and program directors can foresee community members’ attitudes, they can more effectively allocate resources for various rehabilitation programs. Therefore, it is important to examine public attitudes toward punitiveness and rehabilitation to help policy makers deploy more effective correction programs. It is within this context that the present study aims to examine public attitudes toward rehabilitation initiatives. Specifically, the present study seeks to identify the factors that shape Taiwanese public support for rehabilitation.

Literature review

Increasing crime rates and high recidivism rates in recent years suggest that crime is an increasing concern in Taiwan. Most studies on the public’s punitive attitudes and support for rehabilitation have been conducted in the United States and other Western countries; Taiwan itself has very little published material on its population’s attitudes. Consequently, we must draw a review from these previous studies in an attempt to create a comparative dimension for Taiwan.

Previous research suggests that people’s punitive attitudes differ based on several demographic characteristics, such as gender, age, ethnicity, level of education, and economic status (Applegate et al. 2002; Cullen et al. 2000; Lambert et al. 2007; Morri et al. 1995; Sundt et al. 1998). Such characteristics are usually used in studies to differentiate among degrees of punitiveness and perceptions of rehabilitation in different segments of a given population. Yet some researchers claim that these demographic differences are unclear and inconsistent because punitive and rehabilitative attitudes are often a result of several external factors, such as fear of crime, victimization experience, and political affiliation, to name a few. Nonetheless, these factors, which vary from one culture to another, could explain the differences in opinion toward support of rehabilitation and punitiveness (Payne et al. 2004).

The current study aims to examine the different factors that help shape Taiwanese public support for rehabilitation, and how these factors can affect public policies regarding criminal sanctions. Specifically, this study will examine how demographic variables such as gender, age, level of education, and income, affect support for rehabilitation in general, as well as the Taiwanese Rehabilitation and Protection Act (RPA) in particular. In addition, political affiliation will be examined to determine its effect on public support for rehabilitation and the Taiwanese RPA. Factual and stereotypical knowledge is another dimension that will be examined in order to understand its effect on support for rehabilitation of convicted offenders.

Gender

Previous studies on the role of gender in support for offender rehabilitation generally concur that women are less punitive than men (Applegate et al. 2002; Morri et al. 1995; Sundt et al. 1998). For example, Gault and Sabini (2000) examined American college students on the effects of gender and concluded that men support punitive attitudes significantly more than women do. Morri and her colleagues (Mori et al. 1995), who compared white students’ punitive attitudes in rape cases with those of Asian students, also found that males were less punitive than females, and that Asian students held more prejudiced attitudes about rape victims (e.g., the victim’s behavior was assumed to be promiscuous) and thus were less punitive than the white students examined.

Gilligan (1982) developed a theory about the differences between men and women in their attitudes toward crime. She argued that men and women have different moral reasoning: Whereas men base their decisions on the “ethic of justice,” or what they consider to be right or wrong behavior and the appropriate punishment for these actions, women base their decisions on “ethic of care,” or sensitivity and fairness towards others. Therefore, men tend to be more punitive in their opinion on criminal policies, while women tend to be more rehabilitative. Applegate et al. (2002) also examined these differences. In a sample of 559 respondents in Ohio, they found that men and women were nearly equally supportive of general punishment policies; however, when a specific offender was considered, women were less punitive than men. Moreover, when the gender of the offender was considered, women were more supportive of rehabilitation when it was a female offender, though such a level of support was not evident in the male respondents. In addition, men favored capital punishment more than women did.

Some other studies, however, have suggested that women are more punitive than men in certain situations. Payne et al. (2004) surveyed 734 respondents in Virginia and concluded that women are more punitive than men when a crime involves victims. Women may favor punishment when specific deterrence is involved—that is, in order to prevent an offender from committing an additional crime in the future—or for general deterrence, to prevent potential offenders from committing criminal offenses, thereby protecting innocent victims. In addition, Haghighi and Lopez (1998) examined data from a public opinion survey of 1,005 students in Texas and found that women appear to be more oriented toward punishment than men. This may be attributable to a belief that crime is on the rise, which causes women to feel unsafe. Therefore, the less safe one feels, the more punitive he or she will be (Sprott 1999). Nonetheless, women are more likely than men to believe that criminals who commit violent crimes can be rehabilitated if given early intervention with the right program (Haghighi and Lopez 1998).

There are also apparent differences between the genders in regard to juveniles. Schwartz et al. (1993) examined 1,000 adults from Ann Arbor, Michigan, and found that males were more supportive of punitive practices such as juveniles being tried in adult courts, receiving adult sentences, and being confined to adult prisons. These findings were also supported by Jan et al. (2008), who examined data from the American National Opinion Survey of crime and justice.

From the above, there is a general agreement that females tend to be more supportive of rehabilitative initiatives than are men. Consequently, this present study hypothesizes that gender will have an effect on rehabilitative attitudes; in particular, women will be more supportive of rehabilitation than men.

Political affiliation

Another major factor in how the public regards criminals and forms of punishment appears to be an individual’s stated political affiliation. King and Wheelock (2007) found that respondents who identified themselves as social conservatives and Republicans are on average more punitive. Furthermore, Sims and Johnston (2004) found that Republicans, who affiliate with conservatives, were more in favor of the death penalty than independents or Democrats, associated with liberals; the latter were more likely than Republicans to support rehabilitation and early intervention programs for criminals. For juvenile drug-related crimes, Jan et al. (2008) found that conservatives were more supportive of juvenile waivers to adult courts than those who did not identify themselves as conservative.

The difference in punitive attitudes between conservatives and liberals is rooted in their different perceptions of crime and its consequences. Typical conservative views on punishment are a result of their belief in rational choice and moral responsibility, and the conviction that criminals choose their own fate by committing crimes and therefore should be held accountable for their actions (Walker 2006). Additionally, conservatives believe that punishment serves two purposes: specific deterrence and general deterrence. Liberals, on the other hand, tend to believe that crime is a result of social influences such as family structure, peer groups, economic opportunities, and the environment, and therefore they have less punitive attitudes and are more oriented toward rehabilitation (Walker 2006). So it can be concluded that conservatives tend to be more punitive in comparison with those who identify themselves as liberals and who tend to be more supportive of rehabilitation. Therefore, this study hypothesizes that participants who identify themselves as conservatives will be less supportive of rehabilitation than liberals.

Age

Different age groups tend to view crime and punishment in a slightly different fashion, with older people being more punitive than younger people (Payne et al. 2004). In addition, Sims and Johnston (2004) examined data drawn from a poll of 849 respondents in Pennsylvania and found a positive correlation between age and punitiveness. Specifically, they found that as age increases, support for rehabilitation decreases. Additionally, they found that older people were more likely to be in favor of the death penalty. Haghighi and Lopez (1998) found that as individuals age, they tend to more strongly oppose reduction in sentences and the use of parole for criminals who have previously been granted parole for a serious crime.

The notion that older people tend to be more punitive has also been examined in relation to juveniles. For example, Jan et al. (2008) found that for drug offenses, older respondents were more in favor of juvenile waivers to adult court than younger respondents were. Schwartz et al. (1993) claimed that younger people (up to the age of 49) are less supportive of giving juveniles the same sentences as adults. The reason for the increase in punitive attitudes along with age may be due to an increased feeling of vulnerability and the perception that violent crimes are often committed against the elderly (Schwartz et al. 1993), although the reality is that elderly victimization rates are very low (Clemente and Kleiman 1977). Accordingly, this study hypothesizes that as age increases, support for rehabilitation will decrease.

Level of education and socioeconomic status

Another key factor in public attitudes toward rehabilitation of offenders relates to the respondent’s level of education and what that person’s socioeconomic status is. Past studies have shown a direct link between economic insecurity and harsh punitive attitudes toward criminals. Maruna and King (2009) examined punitive attitudes in social and psychological contexts and found that higher education in combination with higher socioeconomic class (but not necessarily personal income, however) predict lower levels of punitiveness, and thus these people were more open to the idea of rehabilitation. Moreover, King and Wheelock (2007) found that respondents with a higher level of education are less punitive than those who have attained only lower education levels. In addition, those who perceive certain groups in society to pose threats to their own economic resources and security or to public safety tend to be more punitive, and thus less supportive of rehabilitation. Brown (2006) examined data from the US General Social Survey on the role of public opinion in American penal culture and found that the professional middle class (slightly younger, whites, males, a higher level of education and an above-average income) were less supportive of the death penalty for murder and expressed less agreement with the notion that courts are too lenient.

In the context of juvenile sentencing, research has shown that as formal education increases, support decreases for trying juveniles in adult courts, giving them adult sentences, and confining them to adult prisons (Schwartz et al. 1993). While examining the public’s views regarding the goals of imprisonment, Sims and Johnston (2004) found that those with a higher education named rehabilitation as the most important goal of prison, while those with less education were more likely to say that prison’s goal was retribution or incapacitation. Income affected views differently, however. Those with higher income were more likely to name retribution as the most important goal, and those with lower income were more likely to say deterrence.

When it comes to punitive attitudes, education and income intersect with other demographic characteristics such as gender and ethnicity. Costelloe et al. (2009) conducted a survey of 2,250 respondents across the state of Florida and found that blacks with higher levels of education are less punitive than those with a lower education level, and that for white men, economic insecurity is related to punitive levels: as economic status worsened, white men tended to be more punitive.

Punitive attitudes may serve as “compensatory satisfaction” for those who are unsuccessful in their occupations. Job insecurity can cause feelings of anger at being an economic failure, and people with low socioeconomic status may channel these feelings of anger and blame toward certain groups in society (Costelloe et al. 2009). The typical objects of anger include beneficiaries of affirmative action, welfare recipients, immigrants, and criminals—all perceived as “undeserving poor” (Hogan et al. 2005). This is a form of “scapegoating” and is known as the “angry white male” phenomenon. In America, white males with a low education level have suffered the most economic decline in the past several decades, and therefore tend to be the “angriest,” according to Costelloe et al. (2009), and as a result have less tolerance for rehabilitation initiatives.

It is clear from previous studies that a higher level of education is negatively associated with punitiveness and that higher levels of socioeconomic status are also negatively associated with level of punitiveness. Consequently, it is hypothesized that as the level of education increases, support of rehabilitation will also increase. With respect to socioeconomic status, it is hypothesized that the higher the socioeconomic status of a respondent, the more supportive of rehabilitation that respondent will be.

Legal obedience

Past studies have also explored how an individual’s degree of legal obedience correlates with punitive attitudes, and results suggest that attitudes toward social control change when one has prior experience with the criminal justice system or has an association with individuals with prior experience (Clear et al. 2001). A study conducted by McCorkle (1993) examined punitive attitudes among individuals with prior experience in the system—the sample included both those who were incarcerated and those who were affiliated with someone who was incarcerated. The results suggested that less favorable attitudes toward punitiveness were strongest among those with a higher chance of being incarcerated—that is, among the young, poor, and minorities. Moreover, a study by Mylonas and Reckless (1963) explored such attitudes among prisoners in relation to several demographic characteristics and concluded that African American prisoners, as well as single prisoners, were less in favor of the law and legal institutes, whereas married, divorced, and white prisoners had a higher acceptance of the law.

Legal obedience is a sociological result of higher education and age. It is commonly known that people with a higher level of education tend to manifest more respect for laws and social norms, as these serve their interests. The same goes for age: older people tend to be less rebellious and thus more compliant with the laws of society, which they also perceive as their protector. Consequently, it is hypothesized that higher levels of legal obedience will have an effect on support for rehabilitation.

Knowledge: Factual vs Stereotypical

Perception is a strong component that guides our knowledge and behavior; however, it is not possible to perceive everything that occurs at all times. In order to identify the most important factors, people rely on selective perceptions, using their beliefs and ideologies to guide them as to what needs to be observed, and the manner in which they interpret these observations (McShane and Williams 2007). People process information in two ways. One is to evaluate, integrate, and interpret all the information that is provided in order to form an opinion; this is known as systematic processing. The second way is to form a decision based on certain environmental cues as well as emotions and values. This is called heuristic processing, a method used by most people, as it permits them to take shortcuts in order to judge a situation (Stalans 2002). The knowledge that results from systematic processing of data and concrete facts is typically called factual knowledge; the results of common beliefs and heuristic processing are called stereotypical knowledge (Stalans 2002).

People’s views about crime and the criminal justice system are diverse; however, their formation of these views is influenced by several sources, such as personal experience, the experiences of family and friends, information distributed by the government, and information provided by the media (McShane and Williams 2007). The public receives most of its news and knowledge regarding crime from the media, which permits the media to control the type and quantity of information that the public is exposed to (Indermaur and Hough 2002). The media generally does not report crime in a way that portrays an accurate picture of the event, but rather presents a distorted picture to maximize the media’s audience, emphasizing information that will appeal most to the public. News that contains severe disruption or danger to the community has a strong dramatic effect on the viewers (Sheley and Ashkins 1981), but also tends to create a false construction of the actual crime reality. For example, Roberts (1992) argued that the media provides a biased view of crime and the criminal justice system, one that often shows violent crime and the system’s lenient reaction. By doing this, the media inflates public perception of the frequency of such violent crimes, which are actually the least frequent (Warr 1980). Consider the crime of murder—it is overrepresented in the media relative to its actual occurrence and frequency in crime statistics. This distorted representation prevents the public from rationally evaluating events, demonstrating the differences between reality and public knowledge of that reality (Roberts 1992).

A study conducted by Warr (1980) explored the accuracy of public beliefs about crime by comparing how respondents estimated the frequency of offenses reported to the police with the actual number of offenses documented by official statistics. Four surveys were conducted in a major American southwestern metropolitan area, with a total of 2,400 respondents. The results of the study revealed that the least frequent offenses were the ones that respondents overestimated the most, and that respondents most underestimated the frequencies of the most frequent offenses. But when it came to the severity of the offenses, the respondents were rather accurate in comparison with the official incidences. On the other hand, Black (2002) found that the public is more inclined to overestimate crime rates and underestimate the severity of existing sentencing practices. These findings suggest that there is a weak correspondence between official information and public perceptions, and that it is accurate to say the public holds misperceptions about criminal offenses.

In addition to reporting individual offenses, the media reports crime trends based on summaries that they receive from the police, but the media has a tendency to give minor coverage to decreasing crime rates and exceptionally thorough coverage to increasing crime rates. The public bases most of its knowledge about crime on information available from the media, and thus gains a sense that crime is on the rise, a phenomenon identified by Sheley and Ashkins (1981). The two researchers compared police statistics with newspaper and television reports, as well as public ideas of crime trends, the frequency of these crimes, and the characteristics of the individuals committing them. Their findings suggest that although the media and police statistics do not present a constant crime trend, 76% of the respondents believed that crime had increased. As for how crime is distributed across categories, the media does not reflect an accurate distribution as it appears in police reports, but rather gives a great amount of attention to violent crimes, suggesting they occur more frequently than they actually do. This finding corresponds with those of Roberts (1992), discussed previously. Although the public has a more realistic view than the one presented by the media, as suggested by Warr (1980), the public’s view is still closer to the view of the media than to the reality presented by the police (Sheley and Ashkins 1981).

Furthermore, the media presents only certain aspects of the justice system. For example, many media reports on lenient sentences focus on a detailed description of the crime, while the judicial reasoning for the sentence remains unknown. This leads to a perception of injustice and an overall view that the system is unacceptably lenient (Roberts 1992). The public’s discontent stems from the belief that its preferred punishment is harsher than the current judicial punishment (Stalans and Diamond 1990). However, interestingly enough, Sheley and Ashkins (1981) found that the majority of the respondents in their study believed that judicial sentencing is too lenient, but this same group would have assigned less severe sentences than legally permitted. Roberts (1992) argues that this is a result of inaccurate information provided by the media, contributing to the public’s lack of true knowledge about the criminal justice system. When the public feels that the system is too lenient, it might lose faith in the fairness and efficiency of the system (Sheley and Ashkins 1981).

Perhaps more damaging, the media associates criminal behavior with stereotypical images of offenders and certain social groups. Because of this, even if the public’s beliefs about crime are unfounded, they might have far worse ramifications than the acts of crime themselves (Warr 1980), as certain groups in society may suffer negative consequences as a result of such beliefs (Gilliam and Lyengar 2000).

Furthermore, the media also informs policy makers on the views, attitudes, and desires of the public regarding crime control and institutional response to crime. Politicians take advantage of the lack of knowledge among the public and exploit the people’s misperception and fears in order to preserve their electoral positions (Indermaur and Hough 2002). Gideon and Loveland (2011) argue that such misperceptions may very well be accounted for by the lack of understanding and inflated levels of fear of crime and criminals. A poll of Americans conducted in 1974 found that four out of five respondents claimed they would vote for a political candidate who supported harsher sentencing (as cited in Zimring et al. 2001). The public’s demand for a stricter justice system has led public officials to respond accordingly and has brought about many changes, including judges in many jurisdictions imposing harsher sentences, legislators advocating for more severe penalties, mandatory sentencing laws being enacted, and more restrictions being placed on parole. These have usually contributed to an increase in the prison population (Roberts 1992).

All of these previous studies suggest that members of the public have, overall, a strong negative view toward crime and the criminal justice system, and that such a view is caused largely by a lack of substantial knowledge or by inaccurate information in the media, which remains the public’s main source of crime news and information. Accordingly, it is hypothesized in this study that the less factual knowledge people have and the more they rely on stereotypical knowledge, the less supportive they will be of rehabilitation initiatives and legislation.

Research methodology

The present study aims to explore the factors shaping Taiwanese public support for rehabilitation. We were interested in how specific variables such as gender, age, level of education, income, political affiliation, legal obedience, and amount of factual and stereotypical knowledge affect public support for rehabilitation of Taiwanese convicted offenders. In order to achieve the above goals, we used a combination of non-probability sampling techniques (convenience, quota, and snowball) to draw a sample of N = 333 adult men and women ages 18 and above that resided in Taiwan between May 2009 and August of 2009. This method is considered appropriate for exploratory studies, and was the most appropriate sampling strategy available in lieu of our difficulties in obtaining a representative sample frame of all adult Taiwanese age 18 and older. In addition, we were limited by the number of research staff that was able to administer the surveys in Taiwan. Consequently, potential participants were approached randomly at bus stops, on trains, and in stations; in shopping malls of major cities; and in schools during the national examination period for both high schools and college admission exams. Such a sampling method, although not necessarily representative, enabled us to describe and measure trends in support of rehabilitation.

The sample covered 15 cities in the four main regions of Taiwan: Taipei, Taichung, Kaohsiung, and Yilan. Taipei, in the north, is the capital city and the economic and political center of Taiwan; 13.3% of our sample came from Taipei city and the surrounding region, which includes two other cities and a total of four counties. The northern region is also the high-tech and commercial center of Taiwan; as such, it is also the richest and most educated region of the country. Taichung is the biggest city of the central region, and 18.2% of our sample came from this city and region, which comprises four counties. High-value agricultural products such as flowers and fruits, as well as a mix of Taoist and Buddhist temples, are the notable characteristics of Taichung and the surrounding areas, much of which is small towns and countryside. Kaohsiung, representing 21.3% of our sample, is located in the south and is the second most important city for economy and politics in Taiwan, with a major steel industry and Taiwan’s biggest port. The second-biggest city in the south is Tainan, which is also the oldest city in Taiwan (4% of our sample came from this city). Southern Taiwan, which has a total of three cities and four counties, is also the center of rice and sugar production. The eastern region, with three counties, is the poorest, with the largest aboriginal Taiwanese population (Han Chinese are still the majority group in Taiwan); tourism and fishing are the major industries here. Yilan is the most developed city in this eastern region, and 8.4% of our sample came from here. The rest of the sample came from various cities located within the above mentioned regions, such as Keelung, Taoyuan, Miaoli, Hualian, Taidong, Chiayi, and Natou.

The sample had slightly more females (59.7%) than males, and the observed average age was about 38 years old. About 16% of the sample were respondents between the ages of 18 and 25; 28.5% were between the ages of 26 and 32; and 16.2% of respondents were between the ages of 33 and 40. Another 16.5% were older than 40 but younger than 50 years of age with about 21% of the sample being older than 50 years of age.

In terms of marital status distribution, 43.3% of respondents reported being single or never married, 49.8% reported being married, and 6.9% reported being divorced or separated. Slightly more than half of our sample (52.1%) reported having children. A majority of the respondents (70.5%) reported being employed full-time, and had on average 14.4 years of formal education (SD = 2.69). Such a high level of education is not surprising, considering that those who volunteer to respond to surveys tend to be more educated people. Another logical explanation could come from the average age of the sample (38 years old), or this average of 14.4 years of education may just reflect the average educational level of Taiwanese people (actual data on level of education was not available at the time of writing). Taiwanese law mandates only 9 years of school, but 95% of students who complete the mandatory 9 years of formal education go on to high school or vocational school, and then college. High schools are typically 3 years, and vocational schools can be 3–5 years. Students who graduate from both types of schools can go on to college; 61.41% of graduates typically do (Ministry of Education of Taiwan, Department of Statistics; http://www.edu.tw/files/site_content/B0013/98_all_level.doc).

The survey

To examine the present study’s hypotheses, a public attitude survey was used. The survey was a self-administered questionnaire designed to examine public attitudes toward punitiveness. The survey had 99 items spread over five domains that combined to create a full picture of a respondent’s level of punitiveness:

-

(1)

Knowledge component—This was intended to examine respondents’ level of knowledge by asking questions about offender characteristics, causes of crime, and impediments to releasing offenders and reintegrating them. Respondents were asked to agree or disagree with statements such as “Most convicted offenders are suffering from drug addiction”; “Most convicted offenders will return to their community upon release”; “Convicted offenders have difficulty finding legitimate employment”; “Released offenders receive monetary aid from governmental agencies”; and “Generally speaking, people who have served their time in prison for non-violent offenses and are released back into society are more likely to commit further crimes.”

-

(2)

Feeling component—This was designed to examine the respondent’s feelings and concerns and how they pertain to offenders, rehabilitation, and reintegration. This component was measured with items such as “How concerned are you about crimes in your neighborhood?”

-

(3)

Hypothetical action component—This was designed to examine how participants might react when challenged with the efforts of offenders to reintegrate back into society. The survey presented specific scenarios involving reintegration, and asked respondents to mark a level of agreement. Examples included “I would not mind having a convicted offender living in my building/neighborhood”; “I would mind having a convicted and treated sex offender living in my building/neighborhood”; and “If I were an employer, I would not mind hiring a released offender.”

-

(4)

Attitude component—This is a byproduct of the previous three components and reflects the respondents’ personal approach. This component was measured by using items such as “My general view toward offenders is that they should be treated harshly”; “With most offenders, we need to condemn more and understand less”; “We should bring the use of the death penalty for serious crimes more frequently”; and “I do not think convicted offenders should get a second chance.”

-

(5)

Legal compliance component—This attempts to examine whether the respondents are law-abiding citizens and their level of legal obedience. This was measured by using items such as “Have you ever used illegal substances/narcotics?”; “Have you ever been in trouble with the law?”; “Have you ever been on probation?”; and “Have you ever been incarcerated?”

Respondents were given a rehabilitative score, which was constructed using answers to seven specific survey items:

-

(1)

“A convicted felon who has recovered from his drug addiction should get a second chance”;

-

(2)

“A convicted violent offender who has successfully completed anger management treatment in prison should get a second chance”;

-

(3)

“Even the worst young offenders can grow out of criminal behavior”Footnote 9;

-

(4)

“Non-violent convicted offenders should be diverted from the prison system and be dealt with in the community”;

-

(5)

“If I were an employer, I would not mind hiring a released offender”;

-

(6)

“Convicted incarcerated offenders should be permitted to pursue academic degrees in most fields during their incarceration and as a step toward rehabilitation”; and

-

(7)

“To what extent do you support the Rehabilitation and Protection Act (RPA) and its renamed association—After Care Association (ACA)?”

Respondents were asked to mark agreement with these items on a six-point Likert scale. The answers were then compiled to form the rehabilitative score, ranging from a low of 10 (indicating very little support of rehabilitation) to a high of 36 (indicating very high support of rehabilitation), with a sample mean score of 23.6 (std = 4.8). Moreover, the score was found to have high reliability (Chronbach’s α = 0.682).

The survey was written in traditional Chinese, the official writing system in Taiwan. The first draft of the survey was reviewed by a criminal justice scholar who is not only proficient in both Chinese and English but also has knowledge of the content. The draft was then reviewed by a Chinese literature teacher in Taiwan in order to ensure that the survey would be understandable to laypeople. As a result, the language used in the final version of the survey was considered to be correct and appropriate for the general Taiwanese population.

Results

Participants were initially asked about their level of concern about the fact that about 35,000 convicted offenders were due to be released from prisons in the upcoming year after having completed their sentence or being granted parole. About 42% of respondents reported being either “highly concerned” or “concerned,” with an additional 36.2% reporting being “somewhat concerned” (see Fig. 1).

We also asked respondents how supportive they were of the RPA and its recent amendments. As can be seen from Fig. 2, a very strong majority (about 93%) of surveyed Taiwanese said they support the RPA and its amended form, the ACA.

Further, participants were asked whether they supported giving various offenders a second chance. Specifically, three general categories of offenders were presented: drug offenders, violent offenders, and sex offenders. Findings were not surprising, in that people were most open to giving a second chance to drug offenders, and less so to violent offenders. Respondents were least likely to grant a second chance to sex offenders, a category of offenders that is often dehumanized. Nonetheless, almost half (48.3%) of respondents said they would not immediately rule out the option of a second chance to sex offenders, and would leave some room for consideration, suggesting they may first want more information about the actual nature of the crime, and might consider different factors as mitigating circumstances. In fact, Taiwan’s Criminal Law Amendment proposal of 2001 included recommendations to set up a registry of sex offenders, similar to the one created by Megan’s Law in the United States. However, the proposal was abandoned due to enormous negative reactions from various interest groups. The hearing process of the Taiwanese Megan’s Law reveals that not only did the authorities not build their arguments on intensive sexual offender research, but they also failed to illustrate the true nature of sex crimes (Lu, n.d.). There is a need for further research on sex crimes and sexual offenders, so that the public will have a better sense of how to address sex offenses and how to treat sexual offenders.

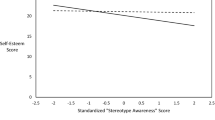

In order to examine the different hypotheses that are the focus of this study, a main-effect univariate generalized linear model (GLM) model was calculated to examine how the independent variables (gender, political affiliation, age, years of formal education, legal obedience, factual and stereotypical knowledge, and socioeconomic status) affected the respondents’ level of support for rehabilitation. As seen in Table 1, only age and stereotypical knowledge were found to have a significant effect on participants’ support for rehabilitation. Specifically, the older the respondent, the more supportive he or she will be of rehabilitation initiatives. This is contrary to our hypothesis, as well as to previous research, which found age to be associated negatively with rehabilitation and positively with punitiveness. We believe our contrary outcome was due to our relatively young sample, with an average age of 38; it is also fairly educated, with an average of 14.4 years of education. More discussion is presented in the next section.

Our main-effect univariate GLM model supports the common wisdom that stereotypical knowledge is associated negatively with support for rehabilitation. Specifically, the model shows that the more stereotypical knowledge the respondent has (that is, the more he or she relies on media reports, rather than actual crime data), the less supportive of rehabilitation he or she will be. Consequently, our hypothesis was confirmed. We discuss this finding further in the next section.

Although not significant, the results from Table 1 are in accordance with previous studies regarding gender. In the model examined above, gender was used as a dummy variable with males as the reference group. Although the results show that females are more supportive of rehabilitation compared with males, this is not significant, and thus we are unable to confirm our research hypothesis with regard to gender.

The results for political affiliation were also interesting. We found that identifying as a conservative (equivalent to an American Republican) is associated with lower support for rehabilitation, as we proposed in our hypothesis. But although the effect observed is very strong (−1.690), it is not significant according to the statistical parameters of the social sciences (α ≤ 0.05). The effect does, however, show borderline significance (α ≤ 0.082), suggesting that such an effect may become significant if examined in larger and more representative samples.

Neither education nor socioeconomic status were found to have a significant effect on support for rehabilitation. However, results from the GLM suggest that higher education does have an effect in the direction hypothesized, that is, that higher education is associated with a higher level of support for rehabilitation. On the other hand, and contradictory to the hypothesis, higher socioeconomic status did not associate with higher levels of support for rehabilitation, nor did legal obedience. But again, these findings were not statistically significant and thus do not allow us to reject or confirm our hypotheses.

Discussion and conclusion

Our results show that the majority of the Taiwanese sample (about 78%) were highly concerned, concerned, or somewhat concerned about the fact that 35,000 convicted offenders would be released from incarceration. This may be due to the high recidivism rate in Taiwan reported earlier in this study. According to the Ministry of Justice in Taiwan, the general recidivism rate in 2007 was about 65.2%, and the recidivism rate for use or possession of a drug was 94.3%. Also, fear of crime and victimization has increased in Taiwan in the last few years. Without a doubt, this also contributes to the results received in this study. Nonetheless, Taiwanese respondents resoundingly supported the RPA. In fact, more than 93% of the respondents supported the act and thus, by proxy, the idea of rehabilitation.

In studying public attitudes toward correctional policies in Taiwan, it is difficult not to notice that most Taiwanese people lack sufficient information about crime and justice policies, as well as basic knowledge about prison inmates. In terms of education, only a few higher-education institutions have criminal justice courses and majors. In politics, crime is a hot-button issue in election campaigns at every level, but rarely does any candidate focus specifically on correctional policies.

Generally speaking, we believe that traditional Chinese social values and the influences of Confucianism may be the answer to the question of why most Taiwanese support the idea of rehabilitation. Basically, Confucianism proposes that education, especially moral education, is essential to correct wrongdoing and the wrongdoers themselves. Choosing not to rehabilitate offenders would keep them in a barbaric state that would require the use of the rule of law. Such use of laws will, according to Liu (2003), interfere with the civilized balance of society. Unfortunately, we did not have any specific items that addressed Confucianism and the importance of moral reform, and thus we suggest that future studies aiming to examine public attitudes toward rehabilitation of offenders in Taiwan should address such an omission. Also, Chinese society values the ability to make contributions to the community. So if offenders can be reformed through rehabilitation and become a valid social workforce, the reasoning goes, why not give them a second chance? The prerequisite, however, is that offenders need to pay for their wrongdoing first, in a variation of reintegrative shaming (Braithwaite 1989).

Although most Taiwanese seem to support the idea of rehabilitation, their support varies according to which type of offender is under consideration. As shown in Fig. 3, most people support the idea of rehabilitation for drug offenders. In Taiwan, the vast majority of drug offenders—83.2% of all drug charges—are those who are arrested and charged with use or possession of illegal drugs.Footnote 10 Using illegal drugs is not a new social problem in Chinese history. The first ban on nonmedical use of opium was instituted in 1834. Nevertheless, most members of society have viewed, and still do view, these opium smokers and users of illegal drugs as patients of addiction. Like alcoholism, drug addiction is a disease, not an unforgivable sin (Chao, n.d.). Thus it is not surprising that most Taiwanese support rehabilitating drug offenders.

Moreover, although the support of rehabilitation for violent offenders is less than the support for drug offenders, the level of opposition remains low. The result may also be explained by the cultural influences of Confucianism. But when it comes to giving a second chance to sex offenders, most Taiwanese seem to be more hesitant to make a decision and express a clear opinion, as can be seen in Fig. 3. One possible explanation is that people do not know much about the specific nature of sex crimes. People who oppose rehabilitation for sex offenders may think that these notorious offenders, such as child molesters and violent rapists, deserve harsh punishment; on the other hand, those who support rehabilitation may think some sex crimes may be forgiven (for instance, teenage couples, one of whom is under age, having sex). Nonetheless, the major issue is that most Taiwanese know little about the nature of sex crimes and the characteristics of sex offenders. As Lu (n.d.) has pointed out, the Taiwanese government fails to provide reliable statistics for sex crimes. As this was not the focus of the present study, but an interesting finding, we suggest that future studies examine attitudes toward sex offenders in more depth, using more representative samples, and survey items that are more focused on the type of sexual crime and corresponding social reaction to it.

The aim of this present study was to explore Taiwanese public attitudes and support for rehabilitation using several factors as independent variables. To that end, seven hypotheses were presented to guide the analysis. Of these seven hypotheses, we were able to confirm only one: that stereotypical knowledge had a negative effect on support for rehabilitation. (Of the remaining hypotheses, the results were insignificant, except for one, that age had a negative effect on support for rehabilitation, but this was likely refuted by the mean age of the sample.)

Focusing on stereotypical knowledge, our findings confirm the hypothesis that heavy reliance on stereotypical knowledge promotes lower support for rehabilitation initiatives and legislation. The principal purpose of the criminal justice system is to maintain law and order by preventing future crime and protecting the public from harmful criminals. Public perceptions and desires for appropriate reaction are often viewed as shaping the decisions and proceedings of the criminal justice system. This role is an extremely sensitive one and comes with grave responsibility. Because the system is meant to serve and protect the public, it is necessary to address the public’s concerns and respond adequately to them. But it is also imperative to understand what actually shapes public perception, as this has an enormous impact on legislation, the justice system, and eventually the public (Gilliam and Lyengar 2000).

Since most knowledge comes from the media, many people develop a distorted sense of reality, or a false construction of reality. This in turn leads people to make judgments based on common misleading stereotypes. It is likely due to this effect that respondents in our survey showed skepticism toward the possibility that offenders could be rehabilitated. Accordingly, we recommend that the ACA and other criminal justice agencies make an effort to provide the Taiwanese public with more accurate information about (1) the general causes of crime and recidivism; (2) the nature and characteristics of criminal offenders; and (3) which programs are available to which offenders. Such information will reduce stereotypical knowledge, which will have a positive effect on public support for rehabilitation and thus eventually lead to better governmental funding.

In regard to age, our findings contradict to previous research findings (Payne et al. 2004; Haghighi and Lopez 1998) that show that older respondents tend to be more punitive and thus less supportive of rehabilitation. The result may be explained somewhat by the effects of traditional culture in Taiwan—older people are more influenced by traditional Chinese culture and Confucianism (which hold that education and rehabilitation may correct wrongdoers), while younger people are more Westernized. Another potential explanation for the contradiction is the fact that our sample is relatively young (about 38 years old), even though only 16.4% of the sample were aged 18–25 years. Although the level of education in our sample was not found to be significant, the respondents did for the most part have more than a high school education, with an average of 14.4 years in school. These two variables combined may be able to provide us with a better understanding about the interaction between age and education. But because education was not found to have a significant effect in our models, such interaction was not examined. Also the effect for “age” was by itself very weak (B = 0.064).

The current study explored and examined public support for rehabilitation. To date, we are unaware of any other study that has attempted to examine this issue in Taiwan. Although we did not use a probability sampling method in this study, we did attempt to survey people randomly in different geographical areas of the country. We believe that such geographical diversity was achieved to some degree, as described in the methods section. Yet the findings do not allow us to generalize the results of this study to the entire Taiwanese population. It is in this regard that we recommend future studies to attempt replicating our study using a more representative sample. It will also be beneficial to examine a slightly larger sample. A larger sample will enable better and more accurate examination of the hypotheses set forward by this study.

Notes

In 2007, 8,412 people were arrested for violent crimes, including murder, aggravated assault, rape, robbery, kidnapping, and the crime of intimidation.

Of 34,991 convicted offenders, 5,400 were violent criminals.

According to Taiwanese laws, recidivists are people who have been convicted again for the same type of crime.

In 2007, 22,805 out of 34,991 convicted offenders were recidivists.

The recidivism rate for robberies was 79.8%; for thefts, 73.6%.

Taiwan adapted many cultural characteristics and legal principles from Japan during the Japanese colonial era between 1895 and 1945.

Meng Tzu was viewed as the successor of Confucius and the second most important philosopher in Confucianism. His work—Mencius—is one of the Four Books of Confucianism.

See Rehabilitation and Protection Act, Legislative Yuan of the Republic of China (1976). Retrieved from http://lis.ly.gov.tw/lgcgi/lglaw (in Chinese)..

This item was adopted from Maruna and King (2009).

See Ministry of Justice of Taiwan, Drug Case Statistics (in Chinese). Retrieved from http://www.moj.gov.tw/site/moj/public/MMO/moj/stat/new/newtxt5.pdf.

References

Applegate, B. K., Cullen, F. T., & Fisher, B. S. (2002). Public views toward crime and correctional policies: is there a gender gap? Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(2), 89–100.

Black, C. M. (2002). Improving public knowledge about crime and punishment. In: J. V. Roberts & M. Hough (Eds.), Changing Attitudes to Punishment: Public Opinion, Crime and Justice (pp. 184–196). Cullompton, UK: Willan.

Braithwaite, J. (1989). Crime, Shame and Reintegration. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, E. K. (2006). The dog that did not bark: punitive social views and the “professional middle class. Punishment and Society, 8(3), 287–312.

Chao, H. K. (n.d.). A lifestyle approach in analyzing drug addiction and rehabilitation and policy implementations (in Chinese). Ministry of Justice of Taiwan: Criminal Justice Policy and Crime Research, 1(11), 237–260. Retrieved from http://www.criminalresearch.moj.gov.tw/public/Data/9929171941925.pdf

Chan, W. T. (1963). A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Chow, C. (n.d.). Looking into the future of Taiwan’s After-Care Association (in Chinese). Ministry of Justice of Taiwan. Retrieved from http://www.criminalresearch.moj.gov.tw/public/Data/993018307670.pdf

Clear, T. R., Rose, D. R., & Ryder, J. A. (2001). Incarceration and the community: the problem of removing and returning offenders. Crime & Delinquency, 47(3), 335–351.

Clemente, F., & Kleiman, M. B. (1977). Fear of crime in the United States: a multivariate analysis. Social Forces, 56(2), 519–531.

Costelloe, M., Chiricos, T., & Gertz, M. (2009). Punitive attitudes toward criminals: exploring the relevance of crime salience and economic insecurity. Punishment and Society, 11(1), 25–49.

Cullen, F. T., Fisher, B. S., & Applegate, B. K. (2000). Public opinion about punishment and corrections. Crime and Justice, 27, 1–79.

Gault, B., & Sabini, J. (2000). The role of empathy, anger, and gender in predicting attitudes toward punitive, reparative, and preventive public policies. Cognition and Emotion, 14(4), 495–520.

Gideon, L., & Loveland, N. (2011). Public attitudes toward rehabilitation and reintegration: How supportive are people of getting-tough-on-crime policies and the Second Chance Act? In L. Gideon & H. E. Sung (Eds.), Rethinking corrections: rehabilitation, reentry, and reintegration (pp. 19–36). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gilliam, F. D., & Lyengar, S. (2000). Prime suspects: the influence of local television news on the viewing public. American Journal of Political Science, 44(3), 560–573.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Haghighi, B., & Lopez, A. (1998). Gender and perception of prisons and prisoners. Journal of Criminal Justice, 26(6), 453–464.

Hogan, M. J., Chiricos, T., & Gertz, M. (2005). Economic insecurity, blame, and punitive attitudes. Justice Quarterly, 22(3), 392–412.

Indermaur, D., & Hough, M. (2002). Strategies for changing public attitudes to punishment. In J. V. Roberts & M. Hough (Eds.), Changing attitudes to punishment: public opinion, crime and justice (pp. 198–215). Cullompton, UK: Willan.

Jan, I., Ball, J., & Walsh, A. (2008). Predicting public opinion about juvenile waivers. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 19, 285–300.

King, R. D., & Wheelock, D. (2007). Group threat and social control: race, perception of minorities and the desire to punish. Social Forces, 85, 1255–1280.

Lambert, E. G., Jiang, S., Jin, W., & Tucker, K. A. (2007). A preliminary study of gender differences on views of crime and punishment among Chinese college students. International Criminal Justice Review, 17(2), 108–124.

Liu, H. C. K. (2003, July 24). The Abduction of modernity—Part 3: Rule of law vs. Confucianism. Asia Times Online. Retrieved from http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China/EG24Ad01.html

Lu, Y. J. (n.d.). Study of sexual crime mapping and recidivism rate—illustrations of Germany and Taiwan (in Chinese). Criminal Justice Policy and Crime Research, 7(9), 317–383. Ministry of Justice of Taiwan. Retrieved from http://www.criminalresearch.moj.gov.tw/public/Data/9107194037983.pdf

Maruna, S., & King, A. (2009). Once a criminal, always a criminal? “Redeemability” and the psychology of punitive public attitudes. European Journal of Criminology and Policy Research, 15, 7–24.

McCorkle, R. C. (1993). Research note: punish and rehabilitate? Public attitudes toward six common crimes. Crime & Delinquency, 39(2), 240–252.

McShane, M. D., & Williams, F. P. (2007). Myths and Realities: How and what the public knows about crime and delinquency. In M. D. McShane & F. P. Williams (Eds.), Youth violence and delinquency: monsters and myths (pp. 1–10). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Morri, L., Bernat, J., Glenn, P., Selle, L., & Zarate, M. (1995). Attitudes toward rape: gender and ethnic differences across Asian and Caucasian college students. Sex Roles, 32(7/8), 457–467.

Mylonas, A. D., & Reckless, W. C. (1963). Prisoners’ attitudes toward law and legal institutions. The Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science, 54(4), 479–484.

Payne, B. K., Gainey, R. R., Triplett, R. A., & Danner, M. J. (2004). What drives punitive beliefs? Demographics characteristics and justification for sentencing. Journal of Criminal Justice, 32(3), 195–206.

Roberts, J. V. (1992). Public opinion, crime, and criminal justice. Crime and Justice, 16, 99–180.

Schwartz, I. M., Guo, S., & Kerbs, J. J. (1993). The impact of demographic variables on public opinion regarding juvenile justice: implications for public policy. Crime & Delinquency, 39(1), 5–28.

Sheley, J. F., & Ashkins, C. D. (1981). Crime, crime news, and crime views. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 45(4), 492–506.

Sims, B., & Johnston, E. (2004). Examining public opinion about crime and justice: a statewide study. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 15(3), 270–293.

Sprott, J. (1999). Are members of the public tough on crime? Dimensions of public punitiveness. Journal of Criminal Justice, 27(5), 467–474.

Stalans, L. J. (2002). Measuring attitudes to sentencing. In: J. V. Roberts & M. Hough (Eds.), Changing Attitudes to Punishment: Public Opinion, Crime and Justice (pp. 15–30). Cullompton, UK: Willan.

Stalans, L. J., & Diamond, S. S. (1990). Formation and change in lay evaluations of criminal sentencing: misperception and discontent. Law and Human Behavior, 14(3), 199–214.

Sundt, J. L., Cullen, F. T., Applegate, B. K., & Turner, M. G. (1998). The tenacity of the rehabilitation ideal revisited: Have attitudes toward offender treatment changed? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 25(4), 426–442.

Walker, S. (2006). Sense and Nonsense About Crime and Drugs: A Policy Guide. Florence, KY: Wadsworth.

Warr, M. (1980). The accuracy of public beliefs about crime. Social Forces, 59(2), 456–470.

Zimring, F. E., Hawkins, G., & Kamin, S. (2001). Punishment and democracy: three strikes and you’re out in California. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Hung-En Sung, Professor of Criminal Justice from John Jay College of Criminal Justice of CUNY, NY, and Ms. Ching-Fen Lu, teacher of Chinese literature at Sung-Sang Senior High School of Taipei, Taiwan, for their valuable assistance in translating and validating the survey. We would also like to thank Zora O’Neill for her helpful editorial comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gideon, L., Hsiao, Y.G. Stereotypical Knowledge and Age in Relation to Prediction of Public Support for Rehabilitation: Data from Taiwan. Asian Criminology 7, 309–326 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-011-9120-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-011-9120-0