Abstract

Trafficked women are used and consumed in different ways and by different users in Australia. They are used by the traffickers and by the consumer of the destination country. They are used as prosecutorial tools by the national criminal justice agents. They are used by the national politicians to pursue border control policy objectives and to be seen as abiding by international protocols. In all these uses, the identity of the trafficked woman is formed and shaped to fit the users’ need. However, these women’s otherness and abjection is constantly maintained and reinforced. They are used as a commodity. Meanwhile, the discussion on the demand side, and the consequent responsibility of the destination country, is virtually omitted. This paper will raise the question of how the socio-legal analysis and discourse would evolve if a literal interpretation of trafficking women as a commodity was taken into account, exploring an international trade approach. The social construction of trafficked women as a commodity has been identified and criticised by academic scholars, NGOs’ and UN’s rapporteurs. By pursuing this line of approach, the destination country is forced to take more responsibility for how the woman is demanded within its territory. As a consequence of this international trade approach, the State should deliver equality and non-discrimination. Rather than being a cynical application of a trade framework to trafficked women, this approach aims to highlight the paradox of such a situation in legal terms. It is highlighted that approaching trafficked women from this legal and jurisprudential way may offer more possibilities to expand their claims against the State. Currently, in Australia, when a trafficked woman is located by the State, she would attract limited and temporal rights, her being the ‘other’ as well as an abject entity remains, notwithstanding the fact the she was imported because there is a demand within the territory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The human rights approach and discourse fail women (Irigaray 1985). This is evident in the case of trafficked women for sexual servitude. In Australia, trafficked women are portrayed and maintained as the ‘other’, as unbelonging matter of the moral and legal community. Trafficked women are dealt with as an external issue—to the point that their conditions and situation are unable to affect domestic policy objectives. Their status as irregular immigrants is used to re-establish a social and moral order, a social identity of the Australian system, which is disturbed by the unwanted presence of trafficked women (Dauvergne 2004). In this context, the socio-political construction of legality internalises a sense of belonging and of citizenship (Bauman 2000).

The portrayal of trafficked women as external to Australia’s domestic issues is manufactured and contrived. In fact, there is a clear connection between the trafficked woman and the internal community. These women are present in Australia due to an existing domestic demand (Fergus 2005); there is an internal market that requires and consumes their sexual services. This connection between trafficked women and the domestic market has mostly been disregarded by national policy makers, and consequently has been overlooked and under-researched. This is why, for example, Costa, the Executive Director of UN Office on Drugs and Crime, emphasises the importance of focusing on the demand side of trafficking as well as other strategies and approaches (2006 United Nations Report on Trafficking in Persons, hereafter 2006 UN Report).

This paper argues that an international trade approach may contribute to the analysis of the problem of trafficking in women through a different lens. This proposal of approaching trafficking in women using various lenses has been already explored (Munro 2006; Bruch 2004). We aim to continue this investigative-process and to offer a further interdisciplinary approach. The twin international trade themes of the consumers’ role in characterising ‘likeness’ and the State responsibility for equality of treatment is explored in the context of trafficked women. It is argued that consumers of trafficked women demand them in their gendered capacity. As a consequence, consumers establish a fixed identity of these women as ‘women’ within the Australian community. The trafficked women are therefore not the ‘other’, but are ‘like’ and equal to national women. Accordingly, the State has a corresponding duty to treat them as equals, regardless of nationality or origin.

Therefore, and controversially, if trafficked women are used and consumed as a commodity through an international trade legal analysis, these women should acquire a stable identity. While it is extremely confrontational, as well as socially, politically and ethically problematic to use the language of commodification in relation to any person, the reality is that a human rights approach has failed these women. Even the most inappropriate approach may offer more real protection than abstract rights. This approach is even more purposeful in the Australian context, where a national human rights bill is still a vague notion rather than a realistic proposition.

Focusing on this demand side of trafficking, whereby the trafficked women’s connection with the domestic market is stressed, challenges several socio-political objectives. According to the mainstream political narrative, once the crime of trafficking in women is cleaned up, the Australian Government has achieved a number of policy objectives, including its safety aims and its border protection goal. Moreover, the Government, while accessing international consensus and abiding by international protocols, has sheltered the internal moral community. In doing so, the community does not face a confronting reality: these women are imported because there is a demand in Australia. It is therefore the argument of this paper that the destination country’s market can, when properly analysed, provide a useful lens through which to consider the role of the demander.

The above discussion is achieved dividing the paper into three sections. In the first section, the recent Australian legal framework is introduced. It is argued that trafficked women’s status of ‘other’ and ‘abject’ (Kristeva 1982) remains. In the second section, the international trade approach is explained and applied to trafficking in women. It is emphasised how Australia should acquire more responsibility towards these women, because of the demand in the destination country. In the third section, demand is contextualised in broader terms, to include the public as consumer of information. By informing the public of the problem of trafficking in women in Australia, the public could demand a better-targeted and more diversified approach.

Trafficked Women as Outsiders in High Gender-Related Developed Australia

Australia is reported to be a high importer of trafficked women, according to the citation index produced by the 2006 UN Report. 1[Predominantly, women are reported to be victims of trafficking; trafficking is mostly reported to be for the purpose of sexual exploitation (UN Report: 100); and Thailand is reported as the main origin country. For a methodology of the Trafficking Database, see UN Report 2006, chapter 4, sections 3 and 4. As a way of a summary, 23 sources mentioned Australia as a destination country. In order to be classified as a ‘high’ destination country, the country needs to be mentioned by a number of reliable sources, which range between 11 and 24, and duplication of data is removed (UN Report 2006: 4.4, and Fig. 58). To be classified as a ‘very high’ destination country, the country needs to be mentioned by a minimum of 25 different sources. This means that Australia is on the verge of being classified as a very high importer.] At the same time, according to the 2005 Human Development Report, Australia is ranked second under the gender-related development index (GDI). 2[The case of Australia is not unique: high to highest importers of trafficked women are also ranked in the top countries for gender-related development].

There is a distinctive dichotomy fleshed out by these two reports: on the one hand, Australia is a high importer of trafficked women, and, on the other, Australia is a country with an excellent rating on gender-related development. The contradiction is essentially that trafficked women are exploited in their gender capacity, yet they do not count as a gendered group in the county of destination.

It may be questioned how these two reports about Australia sit alongside one another, without undermining or impacting upon each other. In fact, they represent a functional and versatile compromise: simply put, transnational criminal matters are dealt with separately from domestic issues of equality. Trafficked women are perceived as peripheral to national governance, and, as such, do not have an impact on gender, equal opportunities and rights in internal political discussions.

Indeed, gender reports and statistics on equal opportunities are a reflection of an internally progressive emancipated society. The pursuit and achievement of equality of opportunities between men and women at a national level has reshaped national governance, through recentring priorities and values of a nation-state through a long term process. This trajectory of purposes, aims and practical achievements symbolises how internal social developments have evolved. The 2007 Report on Women in Australia (Report on Women in Australia hereafter), published by the Australian Federal Government, reflects such an approach. Women are localised within Australia, and their condition and opportunities are scrutinised according to different topical areas—from family to work; from health to crime. The Report on Women in Australia aims to highlight the advancement in equal opportunities of this gendered group. Bishop, Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Women’s Issues, emphasises how “[i]n a rapidly changing world, the women of Australia have much of which to be proud” (foreword, Report on Women in Australia).

However, in a more dynamic and post state-centred world, equal opportunities and gender equalities have started indicating a value that is less nationally based and more of universal significance and impact. The Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW hereafter), adopted in 1979 and ratified in Australia in 1983, is a clear example of this international movement to recognise and promote advancement of women’s rights, opportunities and conditions, and to fight violations of women’s human rights (Acar 2004). This process is guaranteed by the constant review work of CEDAW Committee, to which state-parties submit reports about domestic conditions of women and relevant issues. In this forum, when Australia submitted its report, trafficking in women was briefly acknowledged (CEDAW Committee 716/2006). 3[For an explanation of the role of the CEDAW and its Committee, including how the CEDAW Committee addresses the problem of trafficking in women, see Dairiam (2004).]

Predominately, however, when trafficking in women for sexual exploitation is discussed, the narrative is framed as external of a given country, as a transnational, rather than a domestic issue. Trafficked women, as a group, are not counted in national statistics and in domestic reports on women’s conditions and improvements. They are classified as alien to a system. Their status as irregular immigrants, rather than women living in a country, is the categorising condition. On the basis of this, they are excluded from internal policies and politics, from debates and databases about Australian women, or about ‘Australianised’ women—those women who become Australian and are accepted as regular, legal Australians. For instance, the Report on Women in Australia highlights that 25% of Australian overseas-born women are from the UK, around 10% from New Zealand, 6% from Italy, and less than 20% are of Asian origin (Report on Women in Australia: 2, Fig. 1.1). Evidently, this report refers to admissible, visible and regular women in Australia—women who can be counted officially in statistics of national interests.

There are other women in Australia who were born overseas but remain invisible. In statistics dealing with trafficking, women are disregarded as not belonging to a given territory. They represent an external issue, and are maintained and contained as an external problem. They are classified as illegal; they are criminalised for being unwanted immigrants in Australia. The dichotomy inherent in the two reports is justifiable: trafficked women are perceived and categorised as a hindrance to the ideal of a progressive society. A logical national policy response is to ignore and remove the aberration. The State’s othering strategy works in terms of precluding these women from being considered belonging to the moral community, categorising them as ‘the others’. The unilateral action of the State in the area of immigration policy allows Australia to minimise the impact of the problem of trafficking in women on Australian soil. Only in April 2003, the Minister for Immigration, Philipp Ruddock, when questioned what people trafficking meant, pointed out that if a trafficked woman had knowledge of the aims of her journey to Australia, that is to work in the sex industry, the treatment and conditions during and at the end of her journey would still not contribute to qualify her as trafficked person, but only to maintain the status of smuggled person (Gillard 2003). 4[For the general problem of governments’ contradictory signals on the strategy to adopt in the area of trafficking in human beings, see, in general, Jordan (2002).] Defining a person as trafficked or smuggled does play a major role, as trafficking and smuggling have different political significance (Di Nicola 2005). Denying access to trafficking-definition means denying a level of protection as a victim. This would imply that immigration policy has a cohesive, punitive, all-comprehensive approach to those who are deemed as irregular outsiders.

The New Legislative Framework in Australia and its Little Impact on Immigration Policy

At the end of 2003, the Howard Government shifted its policy orientation (Ellison et al. 2003). The Government announced the investment of Australian $20 million in the fight against trafficking, launched an Action Plan (2004), established a 23-member Transnational Sexual Exploitation and Trafficking Strike Team within the Australian Federal Police, and proposed legislative changes to adopt the 2000 UN Protocol supplementing the Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime, namely the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children (referred to as the Palermo Protocol).

The Palermo Protocol entered into force on 25 December 2003. Australia ratified the Palermo Protocol in September 2005, and legally recognised trafficked women as victims with the Criminal Code Amendment (Trafficking in Persons Offences) Act 2005, section 271.3. The preparation for the ratification of such a Protocol revolutionised the way the Australian Federal Government embraced the problem, reflecting important progressive developments at an international level (Goodey 2003; Segrave 2004).

Under this new legislative framework, emphasis has finally been put on the victims. Trafficked women are now recognised as victims of a specific crime, but on a temporary basis. In order to secure the role of witness, and pursue the objective of eradicating the root cause of the problem (Action Plan 2004), the trafficked women in Australia can now join a thirty day thinking and recovering period, accessing a bridging F visa (Action Plan 2004: 13). Over this period, they can access support, counselling and legal services. Also, these women are asked to consider collaborating with Australian authorities and assist in their investigations. If their being a victim is combined with their willingness to collaborate with Australian Federal Police and other criminal justice agencies, they can be granted a Criminal Justice Stay Visa (Action Plan 2004: 13), and access the witness protection scheme for as long as the criminal trial continues (Fergus 2005; Burn et al. 2005).

In this new regime, these women become classifiable as victims for a term of thirty days, and re-classifiable as valuable witnesses, in which case they can be used as prosecutorial tools (Goodey 2003; Segrave 2004). Once the criminal process concludes, the most likely alternative is to be deported back to their country of origin. The Action Plan (2004: 12) mentions a rather obscure eligibility to a further temporary or permanent Witness Protection (Trafficking) Visa. This visa scheme should protect those women who are at risk of repercussion for their assistance to the Australian criminal justice system, if they returned to their home country of origin. However, further information is not provided, and Burn (2007) refers to this as a confusing and misleading visa regime.

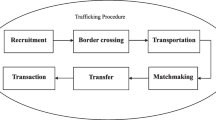

The condition to stay in Australia is strictly limited to their status as a victim of a crime committed almost in its entirety in Australia. The trafficked woman is recognised as a victim, but one that has a specific use and role. She will be used to secure a prosecution, and subsequently deported. The condition to stay is temporary. Her being unwanted remains. This strategy of the Federal Government further emphasises the commodifiable and instrumental role of these women (Maltzahn 2004; see Fig. 1).

Also, this method of tackling the problem of trafficking, by centralising the role of the criminal justice system and its retributive aims, is described inaccurately as ‘new’. It may be innovative in the Australian context; however, it has been already employed and criticised in Western Europe for its lack of concrete results in the fight against traffickers and, generally, in the fight against organised crime (Goodey 2003: 428). In fact, this is what Australia is experiencing under the new legal regime. In Hansard 2006, it was reported that since 1999, more than 150 victims have been referred to the Australian Federal Police, and despite the recent introduction of the visa protection schemes, there have been no successful prosecutions. 5[It should be noted that there have been two successful prosecutions for sex slavery in late 2006, where ‘success’ refers to brothel owners, not the victims and not even the traffickers.] Hubber (Hansard 2006: 13) comments that:

“[the new visa schemes] provide no long-term security or access to rehabilitation support. Without this security, they [the women] risk being deported back to the place they were trafficked from, where the people who trafficked them may still be present and where there is possibly a hefty debt bondage still to be paid. No wonder they are reluctant to give evidence”.

Blackburn, First Assistant Secretary, Criminal Justice Division at the Attorney General’s Department, admits that her Department launched enquiries to search the reasons why there have not been successful prosecutions in Australia. It appears that both the Australian Federal Police and the Commonwealth Department of Public Prosecution estimate the quality of the investigation high and the court had accepted the material as sufficient for committal (Hansard 2005: 8).

Blackburn also reveals that the jury’s perception of the problem may be a further reason to explore why there has been a lack of successful prosecutions. She claims:

“you can draw the conclusion that you potentially have juries that either do not perceive the victims of these crimes as victims or do not perceive the crime as one that is worthy of punishment in the particular circumstances of these cases” (Hansard 2005: 8).

The jury may perceive trafficked women as non-ideal victims, or may judge the crime not as ruthless as it actually is, considering the worthlessness—and otherness—of these women. Either way, this point should be discussed in a more comprehensive approach as it embodies an important key concept. The trafficked women are perceived in their otherness, as not belonging to Australia, as irregular. The gender-related crime of trafficking becomes a side issue; the discriminatory treatment before, during and after the criminal process is thus overlooked.

These women become a new global product of the concept of double-deviancy, in which case a re-classification of triple deviance can be introduced. These women pay for their faults, including that fact that they do not occupy the appropriate gender role, and are judged doubly deviant by society and the criminal justice system (Gelsthorpe 1989). Prostitutes are stigmatised for their work and corrupting role in a moral society (Brock 1998), they are criminalised for their activity; they are classified as abject. However, some prostitutes are more abject than others: trafficked women are stigmatised for working in the sex industry and for being sexually exploited (Kartusch 2001).

Furthermore, these women are also irregular immigrants. This adds a new layer of social stigmatisation. These women are triply-deviant. Illegal immigration has been a national priority that Australia has dealt with as a problem of security and public order (Pickering 2005). Trafficking is still seen as a public order issue. This is evident from the explanation the Federal Government proposed recently when it announced the investment of a further Australian $21 million to promote cooperation and sharing intelligence, as well as evidence (Downer and Ellison 2006). Most focus on the counter-trafficking package is devoted to the tracking down and punishment of traffickers (Burn et al. 2005; Steele 2007). Border protection measures tap into the Australian public’s imbedded anxiety and fear of an Asian invasion (Crock et al. 2006). A hostile climate towards outsiders (Crock et al. 2006) is heavily ingrained within Australian society to allow for any shift in attitude left alone retraction by the relatively recent discussion of women as victims, rather than complicit exploiters of opportunities. This rhetoric about undocumented immigrants applies to human trafficking as well, and can be linked to a time when illegal smuggling, trafficking and asylum seeking shared overlapping meanings, understanding and ‘solutions’ (Pomodoro 2001). Improving border controls and hindering women’s migration into Australia, part of this anti-trafficking package (Segrave 2004), is certainly the Australian Government’s reminiscent of the ‘old’ strategy to keep undesirable nationals out of the ‘Australian dream’.

These women are not only violating Australian borders, they are violating Australia’s good moral values. So, trafficked women are unwanted, are irregular and are corrupting a moral society. Trafficked women become a symbol of abjection. As abject, these women are located outside the normality of the moral community. Through the recognition of trafficked women as victims, society is forced to face an abject entity, which is cast out of the acceptable moral values. Society is forced to face these women, which had been part of it, silently and invisibly. As Kristeva (1982) puts it: “it is thus not a lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules” (1982: 4, emphasis added).

Alternatively, an expedient is formulated to remedy the anomaly. Their irregular status is exploited to solve the problem. Australian society can jettison the unwanted others, the abject entity, employing the otherness strategy. The concept of border control is shifted in time and space (Weber 2006). Borders, which do not produce the desired effect at the periphery of Australia, when trafficked women enter the country, or when their temporary entry visa expires, are shifted forward, and acquire both spatial extension and temporal duration. Borders can be used to revert the status of trafficked women from irregular to regular and vice versa. Through this interpretation, the concept of borders can be modified in both space and time to adapt to the new legislative framework, in a three tiered process (Fig. 1).

Firstly, the presence of some trafficked women in the territory is denied, dismissed or minimised. They are invisible to the vast majority of the Australian society: with no legal identity and with no voice or media presence, they are present with their body, and are reached by the users. In this phase trafficked women’s commercial value is high, and their civil status is low or non-existent.

Secondly, these women are avowed in the guise of being victims; as a consequence of this, they are recognised officially, they are valued as prosecutorial tools, and provided with a documented identity. This part of the process enables the Government to change these women’s status from irregular to regular, granting some civil utility while affirming and protecting values of society—these values being limited to the fight against traffickers. Trafficked women’s abject value is suspended.

In the third phase, the regular status of trafficked women is expended. They are disavowed and devalued, their position is reverted to the irregular and abject status. Their civil utility is consumed, and subsequently rejected as unbelonging matter. The Australian community do not need to fully face abject entities; this traumatic and confrontational experience is avoided. Their commercial value is diminished, notwithstanding whether they had collaborated with Australian authority or not. They are deported back to their country of origin, where they may restart the cycle again, or may need to pay off the remaining debt.

In this three-tiered process, their irregularity within the borders comes to use once a number of policy objectives have been met. These women’s nationality and otherness never leaves them. The disadvantage of such a position is that the Government becomes a conscious exploiter of these women’s condition, using them and rejecting them after criminal justice process. From a position of almost denial, the Government has placed itself in a position of responsiveness, and has chosen the punitive approach, placing emphasis on the traffickers, and maintaining a sense of moral detachment from these abject entities.

The exploitation of these women in their gender capacity is reduced to a detail in the pressing need of Australian society to defend its borders and its moral values. This may be the view held by a group of Australian people sitting in a jury, and judging this form of crime not particularly brutal, or the victims not particularly deserving of protection (Hansard 2005, see section 3). The reaction of the jury can be framed as mirroring the reaction of a society. Thus far, certainly it has been the view shared by the Australian Government. In the context of trafficked women, the irregularity of their status is exploited by the State, once a number of policy objectives are met, including approval by the international community, and abiding by the Palermo Protocol. These women’s civil utility is achieved and expended, and their status is retrieved to the initial position of abject entities. The consequences of such a crime are removed from Australia. The external status of this transnational crime is maintained by guarantying its invisibility. Little emphasis is put on why trafficked women have a market in Australia: the demanders, the users and consumers.

Demanders Creating a Market in Australia: The International Trade Approach

Through excluding trafficked women from the domestic cohort of women to whom the State has an obligation, the State reinforces its control over its own borders. Munro (2006), in her comparative analysis of legal regimes dealing with trafficking, has observed that the Palermo Protocol “permits its provisions to be manipulated in line with domestic agendas of border integrity” (2006: 332). Indeed as Munro (2006: 319) notes:

“Australia’s signing of the UN Protocol [Palermo Protocol] was dependent on a declaration that it would not admit or retain within its borders persons to whom it would not otherwise owe this obligation”.

Australian laws provide a sophisticated version of border protection and control. They allow the trafficked women to stay, temporally, on a conditional basis of assisting prosecutions. This is different from the border security policy used, for example, in relation to refugees who arrive by sea and who are immediately detained and deported, to neighbouring islands such as Nauru, for processing. 6[See for example Migration Act 1958 (Cth) Section 198 A.] Through initial analysis, the border protection policy, as it relates to trafficked women, appears more reasonable. In reality, the outcome of being deported to the country of origin is the same.

Besides border protection, control over trafficking in women also shows that the Australian Government is combating transnational crime. The mere presence of trafficked women is an example of how criminal organisations can and do infiltrate Australia. By returning them to their country of origin, there is at least the perception that the problem is being sent off shore. The crime is being cleaned up.

Despite the attempt to quarantine trafficked women, and thereby controlling borders and transnational crime, the reality is that both of these policy objectives have been compromised. The reality is that there is an ever-ready supply of trafficked women into Australia, and there is no indication of a behavioural pattern that shows a decrease in the supply of trafficked women, considering the strength of the Australian economy in the Asia-Pacific area. The resultant demand for trafficked women, the vicinity of Australia to a number of poor countries, the relatively easy access to cross-border transportation and sophisticated operations of trafficking syndicates mean that this transnational crime of trafficking women will not be declining (Samarasinghe and Burton 2007: 52).

As trafficking appears to be a growing world-wide trade (Samarasinghe and Burton 2007; Leman and Janssens 2006), there is increasing international pressure to treat women more humanely. This is illustrated, for example, in the 2006 meeting of the Committee of the CEDAW at the United Nations, where a Committee member directly appealed to the Australian Government representative “to reconsider its stance on assistance to victims of human trafficking” (CEDAW Committee 716/2006, para 5). The Committee member observed that trafficked women in Australia “should be accorded protection, regardless of whether or not they had agreed to cooperate with the police” (CEDAW Committee 716/2006, para 5). This comment reinforces the view that a suitable and reasonable approach to the issue should be planned and considered from a humanitarian perspective.

Given this continuing international scrutiny coupled with the reality that trafficked women are not going to cease being trafficked, this section aims is to introduce a new lens through which to analyse the treatment of trafficked women so that Australia can develop and respond to trafficked women in a more humane manner. The idea of using different ‘lenses’ to describe and analyse trafficking in women is not a new one. Munro (2006: 322) has highlighted that the problem of trafficking for sexual servitude can be approached “through the lens of numerous frameworks—amongst them human rights, criminality, immigration, labour, gender and prostitution policy”.

The lens through which this section considers the issue of trafficked women is that of international trade law. We aim to illustrate that consideration of international trade principles can be extrapolated and applied to improve the position of trafficked women, in particular the treatment she receives from the destination country. Ochoa (2003: 58) has observed that “because economics, globalization, and human rights are not entirely independent of one another, they experience cross-pollination of their communities and specialty languages”. There is an exchange of ideas between each framework. This section aims to explore further these intersections and possibilities for ‘cross-pollination’, to include concepts, language and jurisprudence.

Indeed, the Special Rapporteur on Human Trafficking, Huda has, with ‘caution’, embraced economic terms in her 2006 Report, noting that “this report employs concepts such as supply and demand in discussing trafficking.” (Huda 2006, para 56) The Rapporteur noted that the overall objective was to provide, through an economic analysis, “a meaning of demand which is consistent with a human rights approach to trafficking” (Huda 2006: para 56).

Furthermore, some international trade analysis is conducted considering that the key driver for trafficking is the economic gain (Diep 2005: 310). Economic gain is the foundational reason for trafficking: past, present and future existence. It has been estimated that trafficking is one of the most profitable transnational criminal activities, which generates seven billion American dollars annually (Diep 2005: 311). As a matter of fact, Diep claims that the whole problem should be seen through an economic lens, in which he describes human trafficking as “an international, market-driven, economic problem that requires an international, economic solution” (2005: 310).

Furthermore, a trade analysis echoes some perceptions of those who demand services from trafficked women. In an important multi-country pilot study into the effects of demand on trafficking, it was noted that:

“the interview research found that those clients who knowingly used [trafficked women]… seemed to think that in prostitution, women/girls actually became objects or commodities, and that clients could therefore acquire temporary powers of possession over them. This was well illustrated in an interview with a client who described prostitution as a market where the woman is selling herself” (GAATW 2001: 23, emphasis added).

Through an international trade law lens, it is possible to reverse the emphasis from the clients’ rights as demanders and consumers to the consequences of such a demand on the trafficked women. In this new legal framework, the analysis will underline and consider the actual effects of demanders’ actions on these women. The key purpose of the international trade approach is to create a theoretical framework to explain how the demanders’ actions can and should create increased rights for the trafficked women to be treated as part of the national community, rather than as non-nationals to be returned to the country of origin.

In order to transfer some aspects of international trade into the discourse of the protection of trafficked women, the following points are discussed below. Firstly, an introduction to the international trade law is presented; in particular, the role of the demander as consumer is examined employing international trade law, to underline how the State takes responsibility for the market created by the demanders. Secondly, this analysis will be transplanted into the role of the demander and consumer of trafficked women. It is highlighted that demand in this problematic area is largely silent in shaping Australia’s policy responses. From this analysis, a new critique of the State’s limited responsibility towards trafficked women will emerge.

International Trade Law: The Role of the Consumer as Demander of Goods

Public international trade law is a set of lawful and enforceable obligations undertaken by up to 150 States under the umbrella of the World Trade Organisation. It is one of the most developed and enforceable international legal systems. International trade law can be considered as a form of international constitutional system under which States conduct themselves (Petersmann 2002: 644).

In International trade law, there is a principle known as the national treatment principle. This principle is contained in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade [hereinafter GATT], article 111(4). This article requires States to treat non-national goods and national goods that are alike in an equal fashion. This national treatment principle is a primary obligations under the WTO, and requires that States treat national and non-national goods ‘like each other’—that is equally, without reference to origin. International trade law requires that the concept of nationality should be removed, as far as possible, in the treatment of goods. Article III (4) reads:

“The products of the territory of any contracting party imported into the territory of any other contracting party shall be accorded treatment no less favourable than that accorded to like products of national origin in respect of all laws, regulations and requirements affecting their internal sale, offering for sale, purchase, transportation, distribution or use” [emphasis added].

This article emphasises the key idea that if there are two like products, they are to be given equal treatment. However, the dense language of article III(4) has caused complex debate, and has offered fertile ground to the development of jurisprudence on the concepts of equality and non-discrimination (Howse and Regan 2000). As Tsai (1999: 27) observed in relation to article III(4): “The meaning of the term ‘like’, as in ‘similar’, is ambiguous. It produces all manners of metaphysical and epistemological questions”.

Qin (2005: 222) has argued, in her work on the WTO, that indeed this concept of likeness or similarity is the key to apply any type of non-discrimination or equality based framework. She notes that:

“It is a deeply-rooted moral principle in Western thought that it is just to treat the equals equally and to treat the unequals unequally. Accordingly, the question almost never rests in whether the similarly situated should be treated equally, but how to classify the equals or the similarly-situated” (2005: 222).

There have been decisions from the WTO Appellate body, the highest dispute settlement body in the WTO, as to how to interpret when a good is ‘like’ another good, and hence deserving of non-discrimination and equality. The leading decision is the WTO Appellate Body Report: European Communities—Measures Affecting Asbestos and Asbestos-Containing Products.7[AB-2000–11 WT/DS135/AB/R (00–1157), adopted by Dispute Settlement Body, 5 April 2001.] In this decision, the Appellate Body has introduced the key role of demander, acting as the consumer, in determining if one goods item is ‘like’ another. 8[Consumer demand is only one test for characterising ‘likeness’; however, this approach to demand and likeness is the focus of this paper (Ortino 2005: 19). For an extensive list of references on the jurisprudence on likeness see Ortino 2005: 16].

“We have also stated that, in a case such as this one, where the physical properties of the fibres are very different, an examination of the evidence relating to consumers’ tastes and habits is an indispensable … aspect of any determination that products are ‘like’ under Article III:4 of the GATT 1994” (Para 139).

Stevenson (2002), analysing this decision, has noted that the consumer needs not to decide whether the products are identical, but that the products are utilised in a similar fashion. If a consumer perceives a non-national product as interchangeable, as ‘like’ a national product, consequently, this way of perceiving the product is a rationale reason for treating the product in the same regulatory manner. The Appellate Body decision established that consumer’s demand is one of the elements that shapes and establishes the ‘likeness’ of goods. 9[Again, it should be noted that there are a series of exceptions and qualifications available under international trade law that deflect and modify the state responsibility. See, for example, GATT (Article XX). These are not the subject of this article. The article is considering the basic normative value of article 111(4).] Once this has been established, the State has the responsibility pursuant to article III(4) to accept this characterisation of the goods. Consequently, if the character of the non-national goods is deemed as equivalent to the national goods, the State has the responsibility to deliver equality of treatment.

Applying the International Trade Role of the ‘Demander’ to the Area of Trafficking in Women

The reference to women as commodity, something to be exchanged, traded, demanded and consumed has been discussed by many feminists, including Luce Irigaray (1985):

“In our social order, women are ‘products’ used and exchanged by men. Their status is that of merchandise, ‘commodities’” (1985: 84).

This section addresses two deliberately disturbing questions. How would the socio-legal analysis and discourse evolve and develop if a literal interpretation of Irigaray’s observation was taken into account? What would occur in the case of trafficked women treated as commodities in legal terms? As discussed above, the jurisprudence on international trade law, which contains themes of non-discrimination, accountability and equality, is frequently applied to commodities. If the trafficked woman was a commodity in legal terms, a non-national commodity, she would have access to this legal approach, and a different discourse could be arising.

Rather than being a cynical application of a trade framework to women, this approach aims to highlight the paradox of such a situation in legal terms. It demonstrates, at a theoretical level, that international trade law has invested and developed a legal jurisprudence supported by Government implementation that overcomes the otherness of goods. However, the same legal and Governmental approach in the area of trafficked women has not been explored. It is clear that the argument proposed is not about women conceived of as a commodity, and, consequently, practical and legal claims cannot be proposed under WTO law. Currently, in Australia, when a trafficked woman is located by the State, she attracts limited rights, her fate with the status of ‘other’ is largely sealed, her being an abject remains as an illegal or legal entity within the territory. A commodity would attract more rights: this is the key point of this paradox. Therefore, this international trade approach challenges and undermines our complacency in her otherness. An international trade analysis reveals the depths of her current alienation, if only through the fact that such an analysis, while not literally transferable to trafficked women, in a theoretical sense would paradoxically have the potential to highlight inequities in the legal treatment of the trafficked woman.

Irigaray (1985), using similar reasoning of the Appellate Body report, describes the central role of consumption, in this case referring to women. Consumption creates an identity through the use of the consumer. Irigaray’s critique is more complex as it is not based solely on commodification, but also on the ability to endlessly exchange the commodity. Referring to the current social order, she claims:

“what makes such an order possible, what assures its foundation, is thus the exchange of women. The circulation of women among men” (1985: 184).

This circulation is endless, and results in endless modified identities and likenesses, as the woman is consumed. In the case of trafficked women, they are consumed by different users, the traffickers, the local demanders, the criminal justice agents. All of them create an identity of the trafficked woman based on how they exchange and use the ‘product’.

While Irigaray rejects the analogy of women used and exchanged as commodities, the approach this article suggests is the opposite. An international trade investigation of the problem can offer the instruments and legal input required to bring the discussion to a different level.

International trade requires that consumption is limited in a temporal and physical sense. The consumer consumes the property to create only one identity. The commodity can not be endlessly reconsumed and reconfigured. To apply article III(4) and the concept of non-discrimination, there is a need to stabilise an identity. If the consumer, in international trade, could endlessly redefine the one commodity, then the product could never be located. This obviously not only refers to a stable geographical and physical location, but also to how—the way the commodity is consumed by the demanders.

Currently, the trafficked woman can never be officially located. She does not belong to the community of the destination country, either as an irregular or regular entity. She, in terms of her identity, is exchanged continually, to make social order ‘possible’, to protect the moral community. The trafficked woman is exchanged from the trafficker, to the demander, from the State understood as the destination country to the State understood as the country of origin. All these actors consume her in a different way.

International trade would disturb this onward flow of consumption. This approach would require the destination country, the physical space where the trafficked woman domiciles, to view this woman as ‘woman’, as she was ‘created’ in only one time and space and in only one identity, as a woman with access to basic rights like regular Australian or ‘Australianised’ women, by and through the consumption of the original demander, the man who demanded her presence in Australia.

Such a view would hold and stabilise her identity: not as an irregular or abject or prosecutorial tool, but in her gendered capacity. As the Special Rapporteur notes:

“Buying sex is a particularly gendered act. It is something men do as men. It is an act in which the actor conforms to a social role that involves certain male-gendered ways of behaving, thinking, knowing and possessing social power” (Huda 2006, para 64).

An identity is established and is maintained by focusing on the market, by analysing the demand side in Australia, and on the basis of what these women are demanded for—their gendered capacity.

This contribution that international trade can offer may increase the lenses through which the trafficked-women problem is discussed. This approach can stem the consumption cycle, because it requires the State to acknowledge that the trafficked woman has been consumed and demanded as a woman. Under the international trade legal framework, such demand characterises and changes her identity from an ‘outsider, trafficked woman’, to become simply a woman.

This could be seen as a small victory. It has not disturbed the central problem of demand, nor the deep problem of commodification of these women. It has, however, at least in a theoretical sense disturbed the social order slightly, as it would require the State to become accountable for how and where the woman is demanded. It would require the State to address the cycle of endless consumption.

Furthermore, through the international trade approach, trafficked women could at least make a logical claim to be treated as equal to national women, within any national policy framework or regulatory response. By way of analogy, WTO law and the concept of demand are used as a framework to construct a theoretical picture of how trafficked women are being used as women within the Australian territory, to which they have been imported. This theoretical framework would suggest that these women would have a claim to argue for equal restorative justice, community concern, Government programmes of intervention and support. And this access to equal treatment would be given to them because they are demanded within the Australian community. Through engaging with this framework, a conceptual work is introduced to demonstrate that focusing on nationality, when it comes to trafficked women as irregular outsiders, may determine an embracing policy response, because they are consumed in Australia, and, hence, they belong—rather than a negative response of ejection and abjection from the Australian community.

However, in Australia, demand has not been a central policy focus. There has not been a concerted policy shift to acknowledge that trafficked women are demanded by men in Australia for their consumption. There has been no policy admission about Australia’s demand for woman as commodity. These women are still treated as present on the Australian territory only for as long as the State tolerates their presence.

In contrast, a trade approach would claim that trafficked women have the right to be present for as long as they need to access equal rights of restorative treatment from the State, on the same basis as national women. In fact, because demand is euphemistically referred to as a physical and psychological demand, the consequences of such a demand result in serious health problems, including infectious diseases, sexually transmitted diseases as well as a range of other physical and mental health issues (Shigekane 2007; Zimmerman et al. 2006; Cwikel et al. 2004). The right to restorative health, counselling and opportunities as a woman is foreseeable as a long-term project. Yet, only a State which had come to some level of acceptance for its role in housing the demanders, for being a destination country, would be willing to provide the financial, political and legal responses and resources to support long-term restorative projects. Instead, Australia constructed its response of the problem of trafficked women focusing on border protection and nationality.

It is this shift that the Special Rapporteur, Huda, has called for in her 2006 Report. There should be a more formal recognition that the transnational crime of trafficking is, in part, created, constructed and demanded by the local actor:

“It is happening everywhere-in our own local villages, towns, cities—mostly carried out by men who are part of the core fabric of our local communities” (Huda 2006 para 78).

A trade approach to trafficking as explained above requires destination countries to take responsibility for how our communities demand and perceive the trafficked women.

It is acknowledged that the trade approach is not a directly applicable theoretical framework, in that international trade law quite obviously does not apply to trafficked women. However, the trade approach reveals that Australia has not accepted the gendered way in which the demander has used the trafficked woman, and is therefore able to maintain the rhetoric of her otherness. There has been, unlike in international trade law, no analytical space in which the State has been required to accept responsibility for how the demander has used and consumed the trafficked women.

Demanding a Cultural Shift

The discourse on demand can be developed further by the Australian Government in the field of trafficking in women. Demand, understood as an impact-shaper on specific issues, can be an inclusive socio-legal term to include general public demand. Demand, in this new interpretation, does not only refer to users of a specific product, in this case trafficked women. It can refer to a social and political expectation of a comprehensive approach to these women, based of the demand of a better, more comprehensive treatment by Australian Government. Demand, in this context, refers to a new category of consumers: not the users of women, but the consumers of accurate information about trafficked women in Australia and their exploitation by men in Australia. These new consumers can shape a market based on their demand of fair and just treatment. This can be reached through a cultural educational movement on the real condition of these women.

Pomodoro (2001) suggests that counter-actions should be continuously updated, and that such updating should be dual, to enable repressive policy and action to be accompanied by restorative aims towards the victims. Thus, assistance is a crucial element. Pomodoro’s innovative analysis argues that part of this restorative counter-action should include a cultural movement able to impact on public opinion. The same aspect, the importance of public reaction, is the subject of a point submitted to the Federal Government by the NGO Scarlett Alliance (Fawkes et al. 2003) to support their discussion on granting working visas or sponsorships to victims of trafficking to enable them to remain in Australia and work regularly in this sector. This NGO highlights that the Federal Government may not proceed along these lines because of fear from public backlash, which would take place “due to the plethora of misinformation on the subject which exists and needs to be countered” (Fawkes et al. 2003: 23). This misinformation is clearly based on, and sustained around the status of abjection that surrounds prostitution, trafficked women and illegal immigrants discussed insofar.

In order to tackle this issue of extending and expanding the level of information around trafficking in women in Australia, the Federal Government aimed to introduce a Community Education Package (Action Plan 2004: 4). This Package is an awareness strategy to augment knowledge of the problem of trafficking within the sex industry, in line with Recommendation 2 of the UN Report 2006. The Community Education Package would include a two-stage process. The process consists of information-gathering from international sources and experiences as well as national consultation, before developing the internal campaign product (Hansard 2005).

Some elements of the Community Education Package are destined to produce little results as conceived in its original approach and planning. It is clear to us that the Federal Government is in near denial on estimates on trafficked women—claiming that “Australia is a destination country for a small number of victims of trafficking” (Action Plan 2004: iii) in open contrast with the UN report classifying Australia as a high destination country. This reflects the lack of understanding and appreciation of the problem. This lack of appreciation of the problem can cause damage to the very system the Federal Government is trying to implement with the new legal regime.

The Community Education Package has “taken longer that one would have hoped” (Hansard 2005: 7) to commence and develop, and should have started running in 2004 (Action Plan 2004: 15). Despite Blackburn’s attempt to claim the opposite before the Joint Committee (2005), the Community Education Package has not been classified as a ‘priority’ in the Action Plan (Hansard 2005).

Also, the campaign is under-budgeted and under-resourced; only Australian $400.000 were allocated over a 4-year period (Hansard 2005), against approximately Australian $40 million invested in this area. This means that less effective methods, such as posters, will be used. In addition, the campaign risks being reduced to the status of a localised temporary project, rather than a massive on-going national campaign.

Furthermore, the campaign is ill-conceived in its aims and targets. The original plan was to target people in the sex industry and its victims. This is perhaps the most problematic area. The failure to prosecute traffickers since the implementation of the new visa schemes can be attributed to several factors, including the fact that the entire Australian community is in need of further awareness and education about the problem of trafficking, because trafficking is not an external issue which has no impact on the Australian community. Burn et al. (2005) stated that some Australian media have dedicated some space to women trafficked in the sex industry in the recent past, but acknowledged that:

“the broader issues of human trafficking [..] have attracted little community attention, despite their strong human rights implications” (Burn et al. 2005: 543).

The publication of the 2006 UN Report received some attention via Australian newspapers, but has failed to general enough public reaction to produce a cultural shift. This has major practical consequences, as highlighted by the Joint Committee (2005). Since there have been no convictions, the Joint Committee raised specific questions on whether “[were] we doing something wrong in our evidentiary process to not get convictions?” (Richardson, Hansard 2005: 8). Blackburn’s reply highlighted the shortfall of the Community Education Package and the role of the jury, indicating the jury’s approach as representative of the general public opinion. In section one, Blackburn is reported as arguing that either the jury does not perceive the crime as particularly bad or does not perceive the victim as an ideal victim. She then continues this point, questioning the limited scope of the Community Education Package:

“For us, in our community awareness package [..], it raises the question of whether we ought to be undertaking a broader exposure of the nature of this activity and its impact both on the Australian community and on the victims.” (Hansard 2005: 9).

This is part of the problem that has not found enough discussion and emphasis. Firstly, demand for trafficked women is clearly localised in Australia, yet trafficked women is an under-discussed problem, and estimates about the number of imported trafficked women were doubted rather than investigated (Hawley 2005). By introducing an over-arching community awareness campaign, public opinion can be influenced and shaped (Bindel 2007), and could reach those very people who would sit in a jury, and therefore, would develop a better and more comprehensive approach to the problem through such a campaign.

Secondly, once the existence of the problem is openly discussed, the public and the media can put further pressure on the Federal Government, generating a demand for action, to include better protection of trafficked women. Knowledge of the problem is a way of fighting trafficking in different terms. Costa (2006 UN Report: 10) argues:

“if people are aware of the dangers of human trafficking, the chances of avoiding its consequences should be improved”.

A holistic approach, rather than a purely punitive approach, with the limiting prospect of victims being used as prosecutorial tools, should include raising public awareness. By continuing putting pressure on the Federal Government, some further actions may occur. Thus far, Australia has failed to generate demand for a cultural shift; nevertheless, the Government has now the opportunity to take responsibility about being a destination country, and can produce a cultural shift in Australia.

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper has been to explore how the actors involved in trafficking of women can be recast. The perception and treatment of trafficked women can be described in a cyclical way. They are imported, used and consumed by the sex industry first and by the legal system later. The legal system aims to protect and affirm the values of Australian society, targeting the traffickers. At this stage, trafficked women assume a civil utility; they are avowed, valued and sheltered in the guise of being a witness. Later, they are disavowed, devalued and not sheltered, when their status reverts to the initial position, with the disadvantage of having lost partial commercial value.

An international trade analysis requires the State to accept responsibility for demand occurring on its territory, recasting the trafficked woman not as ‘other’ and ‘abject’, but as a ‘woman’, deserving equal national treatment. Insisting on the supply side means insisting on territoriality and nationality: this is a misleading way of assessing the problem of trafficked women and setting up benchmarks. International discussions about the problem of trafficking are focusing on demand as well. An invitation of reducing demand implies an initial step towards acknowledging the fact that there is a demand in the destination country. Therefore, framing the problem differently implies reframing the discourse around policy and inclusiveness. The approach to the problem may change if seen from a different angle, tracking women as a woman-issue and centralising the discourse around demand. Localising the crime in the destination country, developing ownership for the demand side, taking action in this sense are part of a more comprehensive solutions to the problem of trafficking.

References

Acar, F. (Chair, CEDAW Committee) (2004). Recent Key Trends and Issues in the implementation of CEDAW. In T. Jonhson (Ed.), Gender and Human Rights in the Commonwealth, Some Critical Issues for Action in the Decade 2005–2015 (pp. 16–30). London: Commonwealth Secretariat.

Action Plan (2004). Australian Government’s Action Plan to Eradicate Trafficking in Persons. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Bauman, Z. (2000). Social Issues of Law And Order. British Journal of Criminology, 40(2), 205–221.

Bindel, J. (2007). Press for Change: a Guide for Journalists Reporting in the Prostitution and Trafficking of Women, Generic Press Resource funded by governments of Sweden and the United States of America and coordinated by the Coalition against Trafficking in Women (CATW) and the European Women’s Lobby (EWL).

Brock, D. (1998). Making Work, Making Trouble: Prostitution as a Social Problem. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Bruch, E. (2004). Models Wanted: The Search for an Effective Response to Human Trafficking. Stanford Journal of International Law, 40, 1–45.

Burn, J. (2007). Liberating the Captives. The Rise of the Global Slave Trade. Sydney: UTS Community Law Centre & Anti-Slavery Project, 27/03/07.

Burn, J., Blay, S., & Simmon, F. (2005). Combating Human Trafficking: Australia’s Responses to Modern Day Slavery. Australian Law Journal, 79(9), 543–552.

CEDAW (1979). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. United Nations.

CEDAW Committee 716 (2006). Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, 34th Session, Summary Record of the 716th meeting (20/01/06). Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention. CEDAW/C/SR.716.

Criminal Code Amendment (Trafficking in Persons Offences) Act 2005, No. 96, 2005.

Crock, M., Saul, B., & Dastyari, A. (2006). Future Seekers II: Refugees and Irregular Migration in Australia. Annandale: Federation Press.

Cwikel, J., Chudakov, B., Paikin, M., Agmon, K., & Belmaker, R. H. (2004). Female Sex Workers Awaiting Deportation: Comparison With Brothel Workers. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 7(46), 243–249.

Dairiam, S. (2004). Using CEDAW to Address Trafficking in Women. In T. Jonhson (Ed.) Gender and Human Rights in the Commonwealth, Some Critical Issues for Action in the Decade 2005–2015 (pp. 164–178). London: Commonwealth Secretariat.

Dauvergne, C. (2004). Making People Illegal. In P. Fitzpatrick, & P. Tuitt (Eds.) Critical Beings: Law, Nation and the Global Subject (pp. 83–100). Aldershot: Ashgate Press.

Di Nicola, A. (2005). Trafficking in Human Beings and Smuggling of Migrants. In P. Reichel (Ed.) Handbook of Transnational Crime and Justice (pp. 181–202). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Diep, H. (2005). We Pay – The Economic Manipulation of International and Domestic laws to Sustain Sex Trafficking. Loyola University Chicago International Law Review, 2, 309–332.

Downer, A. (The Hon, Minister for Foreign Affairs), & Ellison, C. (The Hon, Minister for Justice and Customs) (2006). Australia Increases Commitment to Combating People Trafficking in Asia. Media Release AA 06 061 (15/09/06).

Ellison, C. (The Hon., Minister for Justice and Customs), Vanstone, A. (The Hon., Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs), Downer, A. (The Hon., Minister for Foreign Affairs), Ruddock, P. (The Hon., Attorney-General), & Patterson, K. (The Hon., Minister Assisting the PM for the Status of Women) (2003). Australian Government announces Major package to Combat People Trafficking. Joint Media Release (13/10/03).

Fawkes, J., McMahon, M., Baker, T., Futol, J., & Jeffreys, E. (2003) Scarlet Alliance Submission to Parliamentary Joint Committee on the Australian Crime Commission Inquiry into Trafficking in Women for Sexual Servitude.

Fergus, L. (2005). Trafficking in Women for Sexual Exploitation, Briefing 5/06/2005, Australian Institute of Families Studies.

GAATW (2001). The Demand Side of Trafficking, A Multi Country Study Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW) (2001–2002).

Gelsthorpe, L. (1989). Sexism and the Female Offender. Aldershot: Gower Publishing.

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, Oct. 30, 1947, 61 Stat. A-11, 55 U.N.T.S. 194 (1994). (GATT 1947), which has been incorporated into General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994, Apr. 15, 1994, WTO Agreement, Annex IA, 1867 U.N.T.S. 187, 33 I.L.M. 1153.

Gillard, J. (2003). Call for Immigration Action on Sex Trafficking. The World Today, transcript, http://www.abc.net.au/worldtoday/content/2003/s823818.htm (30/04/07).

Goodey, J. (2003). Migration Crime and Victimhood: Responses to Sex Trafficking in the EU. Punishment & Society, 5(4), 415–431.

Hansard (2005). Joint Committee on The Australian Crime, Commission, Trafficking in Women for Sexual Servitude, 23/06/05, Canberra.

Hansard (2006). Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee, Migration Amendment (Employer Sanctions) Bill 2006, 26/04/06, Canberra.

Hawley, S. (2005). Ellison Rejects Estimate of Sex Slave Numbers, http://www.abc.net.au/news/newsitems/200508/s1439347.htm (30/04/07).

Howse, R., & Regan, D. (2000). The Product/Process Distinction - An Illusory Basis for Disciplining ‘Unilateralism’ in Trade Policy. European Journal of International Law, 11(2), 249–289.

Huda, S. (2006). Economic and Social Council. Commission on Human Rights, 62nd Session, Item 12 of provisional agenda entitled ‘Integration of the Human Rights of Women and a Gender Perspective’. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the human rights aspects of the victims of trafficking in persons especially women and children, E/CN.4/2006/62.

Human Development Report (2005). United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Irigaray, L. (1985). This Sex Which Is Not One. New York: Cornell University Press.

Joint Committee (2005). Supplementary Report to the Inquiry into the Trafficking of Women for Sexual Servitude. The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia.

Jordan, A. (2002). Human Rights or Wrongs? The Struggle for a Rights-Based Response to Trafficking in Human Beings. In R. Masika (Ed.) Gender, Trafficking, and Slavery (pp. 28–37). Oxford: Oxfam.

Kartusch, A. (2001). Reference Guide for Anti-Trafficking Legislative Review: with Particular Emphasis on South-Eastern Europe. Vienna: Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Human Rights.

Kristeva, J. (1982). Powers of Horror: an Essay on Abjection. New York: Columbia University Press.

Leman, J., & Janssens, S. (2006). An analysis of Some Highly-Structured Networks of Human Smuggling and Trafficking from Albania and Bulgaria to Belgium. Migracijske I etnicke teme, 22(3), 231–245.

Leman, J., & Janssens, S. (2006). An analysis of some highly-structured networks of human Smuggling and trafficking from Albania and Bulgaria to Belgium. Migracijske I etnicke teme, 22(3), 231–245.

Maltzahn, K. (2004). Paying for Servitude: Trafficking in Women for Prostitution. Women’s Electoral Lobby Pamela Denoon Lecture 2004.

Migration Act (1958).

Munro, V. (2006). Stopping Traffic? A Comparative Study of Responses to the Trafficking in Women for Prostitution. British Journal of Criminology, 46, 318–333.

Ochoa, C. (2003). Advancing the Language of Human Rights in a Global Economic Order: An Analysis of a Discourse. Boston College Third World Journal, 23, 57–115.

Ortino, J. (2005). From ‘Non-Discrimination’ to ‘Reasonableness’: a Paradigm Shift in International Economic Law? Jean Monnet Working Paper 01/05. New York: New York University School of Law.

Petersmann, E. -U. (2002). Time for a United Nations ‘Global Compact’ for Integrating Human Rights into the Law of Worldwide Organizations: Lessons from European Integration. European Journal International Law, 13(3), 621–650.

Pickering, S. (2005). Refugees and State Crime. Annandale: Federation Press.

Pomodoro, L. (2001). Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation of Women and Children. In P. Williams, & D. Vlassis (Eds.) Combating Transnational Crime: Concepts, Activities and Responses. London: Frank Cass.

Qin, J. (2005). Defining Non-discrimination Under the Law of The World Trade Organization Boston. University International Law Journal, 23, 215–299.

Report on Women in Australia (2007). Office for Women. Canberra: Australian Government.

Samarasinghe, V., & Burton, B. (2007). Strategising Prevention: a Critical Review of Local Initiatives to Prevent Female Sex Trafficking. Development in Practice, 17(1), 51–64.

Segrave, M. (2004). Surely Something is Better Than Nothing? The Australian Response to the Trafficking of Women into Sexual Servitude in Australia. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 16(1), 85–92.

Shigekane, R. (2007). Rehabilitation and Community Integration of Trafficking Survivors in the United States. Human Rights Quarterly, 29, 112–136.

Steele, S. (2007). Trafficking in People: the Australian Government Response. Alternative Law Journal, 32(1), 18–21.

Stevenson, P. (2002). The World Trade Organisation Rules: A Legal Analysis of Their Adverse Impact On Animal Welfare. Animal Law, 8, 107–138.

Tsai, E. (1999). “Like” is a Four-Letter Word - GATT Article III’ s “Like Product” Conundrum. Berkeley Journal of International Law, 17, 26–60.

UN Report (2006). Report Trafficking in Persons: Global Patterns, Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

Weber, L. (2006). The Shifting Frontiers of Migration Control. In S. Pickering, & L. Weber (Eds.) Borders, Mobility and Technologies of Control (pp. 21–43). Dordrecht: Springer.

Zimmerman, C., Hossain, M., Yun, K., Roche, B., Morison, L., & Watts, C. (2006). Stolen Smiles: a Summary Report on The Physical and Psychological Health Consequences of Women And Adolescents Trafficked in Europe. London: The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Derek Dalton for his comments on earlier versions of this paper, and Prof. David Bamford and Prof. Margaret Davies for their support; also we are grateful to the organisers of the Conference on Organised Crime in Singapore, Dr. Narayanan Ganapathy and Dr. Mark Craig.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marmo, M., La Forgia, R. Inclusive National Governance and Trafficked Women in Australia: Otherness and Local Demand. Asian Criminology 3, 173–191 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-007-9042-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-007-9042-z