Abstract

This article describes the process of integrating trauma-informed behavioral health practices into a pediatric primary care clinic serving low-income and minority families while facing barriers of financial, staffing, and time limitations common to many community healthcare clinics. By using an iterative approach to evaluate each step of the implementation process, the goal was to establish a feasible system in which primary care providers take the lead in addressing traumatic stress. This article describes (1) the process of implementing trauma-informed care into a pediatric primary care clinic, (2) the facilitators and challenges of implementation, and (3) the impact of this implementation process at patient, provider, and community levels. Given the importance of trauma-informed care, especially for families who lack access to quality care, the authors conceptualize this paper as a guide for others attempting to integrate best behavioral health practices into pediatric clinics while working with limited resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

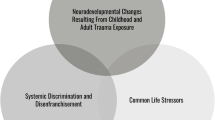

Pediatric traumatic stress exposure, defined as exposure to events and environments that are scary, violent, lacking in resources, or otherwise undermine a child’s sense of safety, is prevalent and serious in the USA.1 About 25% of children and adolescents experience at least one traumatic event in their lifetime, including life-threatening accidents, natural disasters, maltreatment, and family and community violence. Many more children experience other stressors that have been linked to poorer outcomes in behavioral and physical health, such as family chaos, parents working multiple jobs, parents struggling with mental health or legal problems, lack of adequate and/or safe housing, unavailability of transportation, and absence of adequate community and academic resources.2 A large body of literature has detailed the deleterious impact of traumatic stress exposure using a variety of terms to refer to experiences or situations that threaten one’s psychological or physical wellbeing, including childhood adversity, adverse childhood experiences, and toxic stress.3 For some youth, traumatic stress exposure will result in significant difficulties in development and profound long-term health consequences.4

Children and families living in poverty are at-risk for increased rates of exposure to traumatic stress.5 Ethnic minority and refugee families, who are often overrepresented in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations due to current and historical systemic racism, experience higher rates of trauma. For example, one representative US study found that over 75% of Latino youth had experienced at least one traumatic event in their lifetime.6 Significantly higher proportions of Latino children are exposed to violence, physical assault, sexual assault, and polyvictimization (experiencing multiple traumatic events) compared to their European American counterparts.7,8,9,10 Refugee children also experience high rates of traumatic events including, but not limited to, social upheaval, violence and chaos in their country of origin, displacement from homes, transitional placements, uncertainty about the future, loss of home and family members, and resettlement (in addition to the trauma and stressors common to those living in poverty in America).11, 12 Cumulative exposure to such traumatic events is associated with poor academic performance, high rates of risky and acting-out behaviors, internalizing symptoms, problems in social relationships, and poorer health and occupational status in adulthood.13,14,15

Compounding these risks, many experience poor access to high-quality mental health services, especially children living in poverty from ethnic or cultural minority or refugee families. Low-income and minority children are less likely to receive adequate mental healthcare in part due to pragmatic barriers (lack of insurance or finances, scarce or unavailable transportation, and limited clinic hours), community barriers (unavailability of community resources and health clinics), cultural barriers (stigma, beliefs about mental healthcare, and beliefs about the nature/cause of problems), and provider barriers (lack of accurate identification of problem and referral, lack of providers who speak their language, and stigma or lack of trust in providers).16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 Research on health disparities has demonstrated that the mental health needs of minority and refugee children consistently go unidentified and untreated, leading to poorer outcomes throughout development including low educational achievement, increased adversity, and more severe mental health, physical health, and substance use symptoms.6, 20

Integrated care

Given the need of and barriers to mental health services, recent emphasis has been placed on finding innovative and integrated approaches to providing behavioral healthcare to underserved populations who experience higher than proportional rates of traumatic stress. One tactic to solving the need for services has been to use pediatric primary care clinics as key entry points for trauma-exposed children and families.26 Primary care clinics are useful targets of intervention for several reasons. First, youth and families are more likely to access behavioral healthcare services through primary care clinics than through clinics specializing in mental health services. While 75% of children see a pediatrician or primary care provider at least once per year, only 4% see a mental health provider.2, 26 Second, highly stressed children and adolescents, especially those with exposure to multiple stressful or traumatic events, are often involved in multiple systems of care, including child welfare, juvenile justice, mental health services, and physical health services that may or may not coordinate care with one another.27, 28 Primary care clinics can serve as starting points, where providers can identify at-risk youth, make referrals, and coordinate care across other systems. Finally, identifying trauma and other behavioral healthcare needs through routine screening may be an effective early intervention strategy in order to identify and support families before they need higher levels of care.27

Using these ideas, some primary care clinics are implementing trauma-informed protocols into wellness visits to help guide medical providers to have discussions and make treatment decisions that align with the mental health needs of patients. One common best-practice strategy is the use of brief self- or caregiver-reported screeners during every healthcare visit. A wide variety of trauma and stress-related screeners have been developed and recommended for use in primary care settings. Clinics that integrate screeners increase the accurate detection of internalizing, externalizing, and functional impairment in pediatric primary care settings.29 Multiple trauma screeners, including A Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK), have demonstrated clinical validity and utility in child and adolescent samples.29,30,31,32 In recent reviews of the literature, screening has been shown to provide additional information to healthcare providers which helps guide and inform care, detect untreated behavioral health problems, improve the likelihood of family acceptance of behavioral health referrals, and reduce future incidents of trauma (including child abuse and neglect).29, 33,34,35 These screeners are also considered practical for use in primary care settings as they can take very little time and provide information on trauma, stress, and the current functioning and needs of the family.16, 17

Barriers to integration

In recent years, there has been a large push for methods which integrate behavioral healthcare services within medical clinics, but numerous barriers and practical considerations face community clinics as they attempt this integration. For example, despite frequent opportunities to intervene and support stressed families, medical providers receive very little training in methods of behavioral health and trauma-informed care.36 Provider surveys explain that this training gap results in lack of confidence in discussing the results of the screening, absence of knowledge about trauma and traumatic stress, unavailability of resources and referral sites, lack of time or institutional support, and the perception that talking about mental health difficulties is not part of their role as medical practitioners.37, 38 Often times, providers may recognize the mental health needs of their patients, but are unaware of how to discuss this need or what community services are available.26 Therefore, a trauma-informed approach would need to ensure that all staff have the necessary institutional support, knowledge, and skills to identify and support families with trauma exposure.26, 27

Additionally, providers are confronted with numerous external or systematic barriers which make discussing trauma and stressors difficult. These barriers include time constraints in completing all tasks in brief well-child visits, insufficient funding for behavioral health support services, inadequate scope or number of referral services, and a lack of institutional support and established protocols.39,40,41,42 Such systematic changes are even more challenging to implement in clinics in under-resourced communities. Community healthcare clinics that challenge “treatment as usual” in attempting to meet the needs of highly stressed families face additional barriers, including large caseloads without protected time or funding to plan treatment changes, inability to bill for certain behavioral health services, and lack of dedicated space in which behavioral health providers may work.43 Although research shows that successful behavioral and medical healthcare integration requires extensive time, finances, and training, these are often seen as inaccessible luxuries for community clinics in low-income areas. These clinics face a dilemma: Providers are often overworked and underfunded, making integrating behavioral healthcare challenging, despite serving populations who may be in the greatest needs of such practices.

The clinic: Young Children’s Health Center

The University of New Mexico’s Young Children’s Health Center (YCHC) is a pediatric primary care clinic that serves the Southeast Heights neighborhoods of Albuquerque, New Mexico. This region of Albuquerque is 85% Hispanic (self-identified) and 5% Native American and has a growing refugee population. Many of these families speak Spanish or another language other than English as the primary language in their home.44 Eighty-five percent of families live 300% below the federal poverty level with high rates of community violence, prostitution, family and domestic violence, teen pregnancy, single parent households, and unemployment.44 A recent study conducted by the city of Albuquerque found that the Southeast Heights area was disproportionately affected by violence and crime, housing only 6.7% of the people in the city (about 37,600) but home to 27% of the city’s murders and 37% of the nonfatal shootings over a three-year period.45 During this same time period, an incident of violent crime was reported for one in every 10 homes and property crimes were reported in one and every four homes in the area.24

Founded in 1981, YCHC is a community-based, family-oriented Patient-Centered Medical Home with a purpose to serve the needs of the community. YCHC has a strong behavioral health team working alongside physical healthcare providers, including psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, case managers, and trainees in these fields. Despite continued growth and support for behavioral health services, YCHC continuously struggles with limited resources (e.g., lack of funds and time, staffed by only one part-time psychiatrist and one part-time psychologist) to implement change and meet the behavioral health needs of their patient population. In 2012, The UNM Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences was awarded a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) grant as part of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) to fund its Addressing Childhood Trauma through Intervention, Outreach, and Networking (ACTION) program.

In 2014, ACTION partnered with YCHC as part of the Pediatric Integrated Care Collaborative (PICC) sponsored by Johns Hopkins University and also funded by a SAMHSA grant through the NCTSN. The purpose of this collaborative was “to improve access to trauma prevention and treatment services for families with young children by identifying and developing the best practices for trauma-informed integrated care.”25(p.2) The collaboration began when the co-principle investigator of the ACTION grant (a child psychologist in the UNM Department of Psychiatry and second author of this article) approached the Division Chief of Child Psychiatry about the learning community. The Division Chief, the child psychiatrist on the PICC team, had been a provider at YCHC and invited YCHC leadership to meet to learn about the opportunity. The learning community required specific roles on the team, which, in addition to the aforementioned child psychologist and psychiatrist, included the YCHC Medical Director, Behavioral Health Manager, a Home Visiting Supervisor, and a Community Member whose family received services at the clinic. The child psychologist had expertise in providing therapy and community programming to refugee families that experienced war and oversaw the evaluation of the ACTION grant which included screening and assessment of trauma. The child psychiatrist had experience working with traumatized youth in an inpatient psychiatric hospital. While the YCHC team members did not have formal expertise in addressing trauma, they provided services to families with extensive trauma backgrounds and recognized the need to do more to formally address trauma in their clinic.

From January 2015 to December 2018, YCHC implemented a clinic-wide and trauma-informed procedure including screening, identifying and discussing traumatic stressors, and providing support to all families who attended wellness visits at the center. In doing this, the team recognized the very real difficulties of implementing clinic-wide changes in settings with few resources. Therefore, the goal of this article is to (1) describe the process of implementing trauma-informed care into this clinic, (2) explore implementation challenges and lessons learned and what was done to meet these challenges, and (3) describe the impact of this implementation process at patient, provider and community levels. The purpose of this article is to serve as a resource for community, provider, and research discussions of how trauma-informed practices and behavioral health integration can be successfully conducted in under-resourced clinics as well as provide a model and guidelines for other clinics to embark on similar projects.

Identifying Need and Creating an Implementation Strategy

At the first PICC meeting, the team identified the need to develop a process to systematically assess risks for exposure to trauma and current stressors and to work collaboratively with families to address their concerns. The team recognized that traumatic stress was pervasive in the patient population, but there was a need for a multi-dimensional approach to support families in speaking about and addressing their behavioral health needs. Important to this initial planning stage was the awareness by everyone on the team that families were unlikely to report trauma or stress on their own and were unlikely to open up to a physical healthcare provider even if asked. Because of this, the team decided that it was up to the clinic staff to create an environment in which a young person, caregiver, or family would feel comfortable disclosing, recognizing that it may take several times being asked before patients choose to disclose trauma or talk about their needs. This framework was important for buy-in from the leadership at YCHC. Leadership at YCHC was committed to having the pediatricians and pediatric residents, as those most likely to maintain long-term relationships with families, rather than other providers in the clinic lead the process to identify trauma and other life stressors during visits with family members.

In recent years, many leading healthcare researchers and policy makers have recommended healthcare clinics and organizations to transition into “learning health care systems” in which stakeholders (clinicians, administrators, and researchers) participate in a “continuous improvement cycle.”47(p.1019) The goal of this process is to provide higher quality care at lower costs through an ongoing process of guiding clinical care by using the best evidenced-based clinical practices available, collecting ongoing data from these clinical practices, and using this data to continuously inform and make changes with the overarching goal of improving patient outcomes. Given the team’s goals of providing the highest quality care as soon as possible, a unique opportunity was available to study in real time the facilitators and challenges of the implementation process. As is common for research conducted in continuous learning environments, the team had involvement from a wide variety of stakeholders including clinic leadership, a pragmatic focus on using best available evidence to care for patients, and the goal of implementing this process in a timely matter which made the best use of limited resources.47 As part of the PICC learning community, the team utilized a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) model of implementation with the goal of creating a sustainable, non-cumbersome process for identifying children and families with traumatic stress exposure and connecting them to appropriate interventions, if wanted by the family.48, 49 PDSA is a process to support sustainable improvement through quickly testing hunches and adapting practices accordingly. These improvements can be done by a few invested people who can test out small changes, using current best practices and research. It allows them to make adaptations quickly, based on results, before implementing major changes throughout a clinic.50,51,52,53 The PDSA model is frequently used in learning healthcare settings where clinicians and researchers can Plan (predict and strategize how new clinical programs or techniques can be employed to improve outcomes), Do (implement these new programs), Study (collect ongoing data and analyze how implementation of new programs has influenced outcomes), and Act (standardize the new programs or establish future plans for additional adjustments).50, 52 This process was ideal for this setting where ideas were tested for short periods of time with a few providers before clinic-wide implementation. The implementation process is described through several cycles below.

The team collected data throughout the PDSA process. These data included the number of (1) well-child visits at the clinic, (2) screeners administered and the families’ unique responses to the screeners, (3) families identified as at-risk, (4) referrals to behavioral health services, and (5) families who attended their referred behavioral health appointment. Data collection related to the screening process took place from January 2015 until December 2018. The clinic also collected behavioral health referral data prior to the implementation of the screening (January 2011 to December 2014). In addition to patient data, feedback on the process was also collected from providers through several focus groups in March 2017. Given the goal to have providers create a safe environment for families to discuss sensitive information, these focus groups were an instrumental part of the PDSA process which allowed the collaborative to receive feedback on the implementation process from YCHC providers. Focus group participants consented to being audio recorded and their responses were transcribed and qualitatively explored for feedback and common themes. The following section describes three PDSA cycles of implementing trauma-informed interventions that each built on the previous cycle.

PDSA cycle one

In the first cycle of the process, PDSA was used to select and implement the systematic use of A Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) questionnaire to engage families in a discussion about trauma and stressors.26 The goal of this initial screening was to build a relationship between the primary care provider and the family and aid in the start of a discussion about the family’s current functioning and needs. The SEEK is a 20-item parent report screener that asks about their child’s trauma history, the parent’s mental health, family and home safety, and access to resources (e.g., adequate food and shelter). SEEK questionnaires are available in English and Spanish, as a large proportion of YCHC patients are primarily Spanish speaking and meeting the families where they are is a primary goal of this process.54 Previously, the SEEK was used sporadically in well-child visits at YCHC and pediatricians often did not follow up with the families regarding their responses. So, as part of the planning phase of the PDSA process, the team examined the questions on the SEEK and other screeners to determine which screener met the purpose of screening for trauma. They decided that they should first test whether the SEEK was a useful tool since it was already part of the YCHC screening practice. As part of the doing phase of PDSA, an initial two-week period was set up in which families completed the SEEK at all their well-child visits and a small team of providers followed up with families about their responses regardless of whether they were positive or negative.

At this point, the team also established activities that promoted a trauma-informed atmosphere in the clinic, increasing the likelihood of families feeling comfortable discussing trauma. For example, all YCHC staff received training on an overview of the PICC project and on trauma-informed care by non-clinicians. Clinic leadership and supervisors took an active role in promoting and supporting the use of screeners and supported clinicians in its use.

PDSA cycle two

After completing a PDSA cycle for selecting and implementing a screening tool, the collaborative reviewed the process. As the process was expanded to more clinic providers, feedback was given that although they recognized the importance of discussing trauma and stressors with their patients, providers did not feel they had the skills or tools to have a discussion and plan for next steps if stressors and challenges were identified. Given that feedback, the team developed a second PDSA to develop a simple set of questions for the pediatricians to start and guide the discussion of the SEEK and each family’s strengths, stresses, and needs. See Fig. 1 for the complete script for the surveillance questions developed the Young Children’s Health Center team.

Providers were taught that these questions were an opportunity to meet the family where they were currently, gaining an understanding of their patients and their needs, but also promoting family strengths and building resilience. Training on using these surveillance questions prepared providers to collaboratively identify the needs and strengths of the family, come up with a plan to better support the family, and refer the family to clinic or community resources (behavioral health treatment, case management, Autism Spectrum Disorder behavioral and occupational therapy, parent training programs and respite care resources). Once the surveillance questions were tested in the PDSA cycle, all primary care providers at the clinic received training on reviewing the SEEK with families and on asking the surveillance questions in well-child visits. SEEK data was collected clinic wide (see Table 1). For data collection purposes, providers completed a brief form for each well-child visit that inquired about whether the surveillance questions were asked, if any risk was identified, and whether any referrals were generated, using the existing referral network at the clinic (see Table 2).

PDSA cycle three

As described in a later section, use of the SEEK and surveillance questions led to a large increase in behavioral health and case management services. In the third PDSA cycle, it was identified that the clinic could not currently staff all of the families who needed behavioral health support. Gaps between service needs and the ability to meet those needs are common at community clinics such as YCHC, which have limited time and resources. Worries about not being able to provide services to all those in need often hold clinics back from implementing behavioral health screening. However, during the PDSA process, the team discussed that creative measures were needed to address the increase in referrals until additional funds and resources could be secured. Therefore, the team decided that the clinic would temporarily triage the large number of referrals, refer to outside community agencies when urgent or appropriate, and continue to collect data on the number of behavioral health referrals generated to use this information to justify the hiring of new staff and applying for new grants.

To triage the referral process and empower families to address challenges themselves, the team used the PDSA process to develop a set of questions to classify the urgency of a problem and referral level based on Motivational Interviewing principles.55, 56 If a need was identified through the SEEK or surveillance questions, two triage questions were asked (see Fig. 1). Based on the families’ responses, the provider determined whether a referral to the behavioral health team was necessary and classified the referrals as either immediate, urgent, or routine. This process allowed providers and families to gauge the current severity of symptoms and motivation of the family to engage in care. With this information, providers were able to refer to in-clinic behavioral healthcare providers or outside agencies as needed. As the clinic secured additional funding for behavioral health services and was able to hire additional providers to meet the needs of the clinic, the triaging was removed from the process.

Focus groups

Getting feedback from the healthcare providers who were performing the screening process was instrumental in implementing these practices. To do this, three focus groups were held for YCHC providers. Two focus groups were specifically for residents (N = 5, N = 3) who were primarily staffing the well-child visits. The third focus group was open to all providers at the clinic, including residents and attending pediatricians (N = 9). The purpose of having two resident-only focus groups was to ensure providers felt safe discussing their experiences without their supervisors present, thus removing potential power imbalance or a reflection on their quality of care. The third focus group was aimed at getting a better picture of how all providers, including supervisors felt about the implementation process of trauma-informed screenings. At all three focus groups, semi-structured and open-ended interview questions were used to prompt an open dialogue between providers. The team was particularly interested in understanding providers’ experiences and asking about trauma and stress before and after the implementation of the screening process. Questions asked and topics discussed at the focus groups included providers’ comfort level and personal thoughts and feelings about discussing trauma with patients, their opinions on how the process facilitated referrals or provided other services, what challenges they experienced, and any recommendations on the process. As described later, feedback from providers contributed important insight into the outcomes and impact of the screening process on patients, providers, and the clinic as a whole (see Table 3).

Implementation Outcomes and Impact

The implementation of a trauma-informed screening procedure had influences at the patient, provider, and clinic level. At the patient level, this procedure increased the number of families identified, referred to, and engaged in behavioral health services. At the provider level, clinicians reported increased confidence and value in asking families about the traumatic stress. At the clinic level, this procedure went from being used sporadically to being consistently used at all well-child visits. Additionally, the use of this screening changed the culture of the clinic, increasing collaboration between providers and other healthcare professionals and strengthening the clinic’s relationship with the community it serves.

Identification of families in need

From 2015 until 2018, the clinic saw a rise in the number of SEEK questionnaires administered (see Table 1). By 2018, 97.5% of well-child visits had a SEEK completed by the family. The other 2.5% is likely made up of families who elected not to complete the SEEK, despite being offered it by the provider, or did not speak either English or Spanish. The authors see the consistent use of a trauma-informed screening as a major success given that prior research in this area has identified many barriers to implementing a consistent trauma-informed protocol with healthcare providers.12, 13, 17, 18

When SEEK administration was sporadically completed at well-child visits, in 2015 and 2016, the clinic saw high rates of families identified as needing additional behavioral health support. In 2015, 110 out of the 113 who completed a SEEK questionnaire were positively identified as needing additional behavioral health support (i.e., family endorsed at least one item on the SEEK questionnaire). In 2016, 229 out of the 231 completed were positively identified (see Table 1). This large proportion of families identified suggests that providers were initially using the SEEK with families who they already suspecting might have traumatic stress exposure or were in need of behavioral health resources. This utilization of the trauma screening protocol has both positive and negative consequences. Positively, it shows that providers were able to rely on the screening in order to talk about trauma and stressors with their patients. Given previous research that suggests that many healthcare practitioners feel unsure or lacking the competence to talk to their patients about trauma, the SEEK questionnaire and surveillance questions can be seen as a tool for providers to open up the discussion about the effects of trauma, behavioral health needs, and possible resources available to families.37, 38 On the other hand, lack of consistent use of this protocol may lead to families falling through the cracks when providers fail to ask about trauma or stressors for those families they assume do not need support. In focus groups, multiple providers shared that it took them time to feel comfortable initiating and engaging in conversations about trauma with their patients (see Table 3).

Over time, the clinic was able to transition from sporadic to consistent screening. In 2017 and 2018, the SEEK was being consistently administered at all well-child visits (see Table 1). During this time, significantly higher numbers of families were identified as needing behavioral health support, suggesting that universal screening identified families who were not otherwise reporting or discussing trauma with their providers. However, as higher numbers of patients were being identified with this consistent screening protocol, the percentages of patients screened positively out of the total number screened dropped. For example, in 2018, 1443 families were identified as needing behavioral health support, a drastically higher number than what was seen in 2015 and 2016. However, as a percentage of the total families screened, only 37.13% of the families were identified as needing support (see Table 1). In other words, as the clinic was now identifying higher numbers of families in need, they were also screening many families who denied traumatic stress or did not need and/or want behavioral health support.

As the clinic transitioned into one where each and every family was asked about their trauma and behavioral health needs, providers began to notice qualitative differences in their interactions with families. In focus groups, some providers noted that it appeared that parents were not expecting a question about strengths and were caught off guard, which led them to open up. Other parents had difficulty identifying things going well and then opened up about challenges they were experiencing. Many providers noted that the small steps they took to engage with families made a big difference. While families completed the screener, the surveillance questions were often the point at which they began sharing difficulties such as multi-generational trauma. Providers also noticed that families returned for check-ups; they formed relationships with providers, seemed to have an increased level of trust and comfort in sharing experiences, both positive and stressful, and asked for help from the clinic (see Table 3).

Impact on providers and the clinic

A major result of this multi-year process is that the clinic staff and clinical services became more trauma-informed. As the screening procedure was implemented and used more and more frequently, the clinic saw a rise in behavioral health referrals made (see Table 2 and Fig. 2). Before the implementation of the screening process (2011–2014), the clinic made between 121 and 259 referrals per year. In the years 2015 and 2016, when the screening process was used sporadically, the number of referrals jumped to 403 and 466 per year respectively. By 2017 and 2018, the fully implemented process yielded 916 and 1187 behavioral health referrals in each respective single year. In addition to the increase in referrals, the percentage of families attending their behavioral health appointments also increased (see Table 2). By 2018, 85.17% of families referred for behavioral health services attended their first appointment. The authors interpret these trends as incredibly positive: not only was this clinic able to refer more families to behavior health services, they were also successful in increasing engagement with behavioral health services. Focus group participants noted that the use of a strengths-based and trauma-informed protocol helped make families more comfortable and engaged in their healthcare decisions, leading to increased access of behavioral healthcare services (see Table 3).

Additionally, providers reported an increased awareness of families affected by trauma and their role in addressing traumatic stress. As time went on in the implementation process, staff appeared to be more comfortable asking about trauma and behavioral health needs. Many providers reflected on initial apprehension, but over time they came to appreciate the importance of discussing and treating trauma as part of high-quality patient care (see Table 3). Some, however, did not feel comfortable with the process developed to discuss trauma with families. They provided useful feedback in the focus groups for improving the process that would help with their comfort in discussing trauma, including additional training and practice (see Table 3).

Clinic-wide efforts have also been taken to further train providers on trauma-informed care, including an introduction to trauma and how it affects patients for all staff, not just healthcare providers. This included training clerical staff to understand that many families may have experienced trauma and how they interact with these families can promote a safe, welcoming environment. This training also included how to recognize that when a patient appears upset or agitated, it may be a result of a trauma reminder. Behavioral health and medical staff have received additional training through the ACTION grant on the Attachment, Regulation, Competency (ARC) model, a trauma-specific evidence-based practice. YCHC staff participated in two ARC learning communities (2015 and 2018) where they attended a two-day training and participated in 10 monthly 90-minutue consultation calls. ACTION staff also provided booster sessions specifically for YCHC staff and conducted a day long trauma-informed care training for 12 YCHC home visiting staff and supervisors. ACTION staff supervised pre-doctoral psychology interns at YCHC, one of whom joined YCHC staff after completing her training. Finally, training on the use of the SEEK and surveillance questions have been built into training procedures. During clinical precepting, pediatric faculty teach medical students, pediatric residents, and other students rotating through from various disciplines about the model. The process is integrated into learning plans, just as other health topics are, and is required in their presentations, clinical notes, and practice. Additionally, every pediatric intern at UNM completes a four-week rotation on the subject of Advocacy and Community Engagement, during which they learn the strengths-based trauma-informed care model.

As a result of this screening process, additional steps have been taken in making clinic-wide changes to support at-risk children and families. For example, the clinic used data collected in the PICC initiative to advocate for the hiring of a part-time psychologist and received a grant from the Bernalillo County for additional funds for trauma services. Because YCHC staff saw the benefit of data collection, leadership hired an epidemiologist to support data collection, which is used for grant writing and justifying hiring additional behavioral health staff. There appears to be an increased energy among clinic staff, providers, and administrators to provide the highest quality of services to the families they care for. In focus groups, many staff members commented that the process has impacted families receiving services at the clinic, even when the family may not have experienced trauma. Staff noticed that the strengths-based approach has led to very meaningful conversations with parents (see Table 3).

Limitations and Future Directions

Several factors limit the scope of this study that should be explored in the future. As is expected from research generated in a learning healthcare system, this initiative was not developed as a laboratory-enclosed research study or clinical trial, but as a description of the process of implementing change within a working healthcare clinic.46, 47 Therefore, the data was collected within the limits of an active clinic with the main priority of serving patients and does not have the same methodology that would be seen in a formal research study. For example, the data collection procedures used make it impossible to track the specific SEEK data with behavioral health outcomes of individual patients and families. While this article allows correlations to be made between aggregate, clinic-wide data for both SEEKs administered, referrals made, and behavioral health appointment attendance, it is unable to track the progress of specific families over time. Therefore, the team was not able to differentiate the impact of administering the SEEKs versus the impact of the surveillance questions on behavioral health outcomes. Additionally, because in-session conversations between providers and families were not recorded, the team was unable to make specific comments on content of the conversation guided by the surveillance questions. The current data indicates if a provider engages in the process, but does not indicate the quality of that process or how it influenced family, provider, or clinic outcomes. Since this was not a controlled study, future research could be conducted on various parts of this implementation process. For example, future research could separate the SEEK from the surveillance questions to determine if one is more impactful than the other or if both tools should be used together. Future studies could also analyze the content of the trauma-informed process, for example, by evaluating the extent to which provider’s conversations were aligned with trauma-informed principles. Finally, future research should continue to focus on best practices that support primary care providers in discussing trauma and helping families receive the support they desire.

Implications for Behavioral Health

This study can be seen as a promising exploration of how busy, community-based pediatric primary care clinics with limited resources can implement trauma-informed screening processes and teach medical care providers how to discuss trauma and behavioral health needs with their patients. Given the numerous barriers and lack of resources that are often available to research-funded academic clinics, YCHC’s ability to consistently administer the procedure at all well-child visits successfully led to patient-, provider-, and clinic-level changes. Importantly, the changes have significant implications for the behavioral health and wellbeing of YCHC patients: Children and families receiving medical care at the clinic have access to providers trained in recognizing, discussing, and providing support and referrals for behavioral health conditions. Given many barriers to quality mental healthcare socioeconomically disadvantaged and minority families face, including stigma, distrust of healthcare providers, lack of identification of behavioral health concerns and lack of referrals, the team sees this project as successful in creating a clinic environment which allows providers to form safe and trusting alliances with their patients and creates opportunities for collaborative and strengths-based conversations about trauma, behavioral health needs, and services.16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 This has led to higher rates of identification of trauma and behavioral health needs and higher rates of families receiving behavioral healthcare. The team foresees continued advancements to support behavioral health needs. For example, YCHC made a commitment to the process and collected data that was later used to justify hiring additional staff and in funding proposals. This paper is particularly relevant for clinics that do not have the budget or ability to conduct a large study on the impact of screening for traumatic stress. This is an example of how such clinics can support their patient populations through the implementation of behavioral health and trauma-informed procedures.

References

Peterson S. About Child Trauma. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Published January 22, 2018. Accessed Dec 19, 2019. https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/about-child-trauma

Costello EJ, Pescosolido BA, Angold A, et al. A family network-based model of access to child mental health services. Research in community and mental health. 1998;9:165–190.

Adverse childhood experiences are different than child trauma, and it’s critical to understand why. Child Trends. Published April 10, 2019. Accessed Apr 17, 2020. https://www.childtrends.org/adverse-childhood-experiences-different-than-child-trauma-critical-to-understand-why

Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM, Schreiber MD, et al. Children and Families: A New Framework for Preparedness and Response to Danger, Terrorism, and Trauma. In: Psychological Effects of Catastrophic Disasters: Group Approaches to Treatment. Haworth Press; 2006:83-112.

Yoshikawa H, Aber JL, Beardslee WR. The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: Implications for prevention. American Psychologist. 2012;67(4):272-284. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028015

Bridges AJ, de Arellano MA, Rheingold AA, et al. Trauma exposure, mental health, and service utilization rates among immigrant and United States-born Hispanic youth: Results from the Hispanic family study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010;2(1):40-48. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019021

López CM, Andrews AR, Chisolm AM, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Trauma Exposure and Mental Health Disorders in Adolescents. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psycholology. 2017;23(3):382-387. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000126

Crouch JL, Hanson RF, Saunders BE, et al. Income, race/ethnicity, and exposure to violence in youth: Results from the national survey of adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(6):625-641. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(200011)28:6<625::AID-JCOP6>3.0.CO;2-R

Phipps RM, Degges-White S. A New Look at Transgenerational Trauma Transmission: Second-Generation Latino Immigrant Youth. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 2014;42(3):174-187. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2014.00053.x

Cleary SD, Snead R, Dietz-Chavez D, et al. Immigrant Trauma and Mental Health Outcomes Among Latino Youth. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2018;20(5):1053-1059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0673-6

Betancourt TS, Newnham EA, Layne CM, et al. Trauma History and Psychopathology in War-Affected Refugee Children Referred for Trauma-Related Mental Health Services in the United States. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25(6):682-690. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21749

Lustig SL, Kia-Keating M, Knight WG, et al. Review of Child and Adolescent Refugee Mental Health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(1):24-36. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200401000-00012

Appleyard K, Egeland B, Dulmen MHM, et al. When more is not better: the role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(3):235-245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00351.x

Evans GW, Kim P, Ting AH, et al. Cumulative risk, maternal responsiveness, and allostatic load among young adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(2):341-351. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.341

Sousa C, Mason WA, Herrenkohl TI, et al. Direct and indirect effects of child abuse and environmental stress: A lifecourse perspective on adversity and depressive symptoms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2018;88(2):180-188. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000283

Derose KP, Escarce JJ, Lurie N. Immigrants And Health Care: Sources Of Vulnerability. Health Affairs. 2007;26(5):1258-1268. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1258

Flores G. Language Barriers to Health Care in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006; 355:229-231. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp058316.

Morris MD, Popper ST, Rodwell TC, et al. Healthcare Barriers of Refugees Post-resettlement. Journal of Community Health. 2009;34(6):529-538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-009-9175-3

Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, et al. Race, Socioeconomic Status and Health: Complexities, Ongoing Challenges and Research Opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186:69-101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x

Bear L, Finer R, Guo S, et al. Building the gateway to success: An appraisal of progress in reaching underserved families and reducing racial disparities in school-based mental health. Psychological Services. 2014;11(4):388-397. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037969

Flores G, Research TC on P. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Health and Health Care of Children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e979-e1020. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0188

Slade EP. Effects of School-Based Mental Health Programs on Mental Health Service Use by Adolescents at School and in the Community. Mental Health Services Research. 2002;4(3):151-166. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019711113312

Yeh M, McCabe K, Hough RL, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Parental Endorsement of Barriers to Mental Health Services for Youth. Mental Health Services Research. 2003;5(2):65-77. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023286210205

Kodjo CM, Auinger P. Predictors for emotionally distressed adolescents to receive mental health care. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35(5):368-373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.005

Gudiño OG, Lau AS, Hough RL. Immigrant Status, Mental Health Need, and Mental Health Service Utilization Among High-Risk Hispanic and Asian Pacific Islander Youth. Child Youth Care Forum. 2008;37(3):139-152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-008-9056-4

Ko SJ, Ford JD, Kassam-Adams N, et al. Creating trauma-informed systems: Child welfare, education, first responders, health care, juvenile justice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39(4):396-404. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.39.4.396

Briggs EC, Fairbank JA, Greeson JKP, et al. Links between child and adolescent trauma exposure and service use histories in a national clinic-referred sample. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2013;5(2):101-109. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027312

Gillespie CF, Bradley B, Mercer K, et al. Trauma exposure and stress-related disorders in inner city primary care patients. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):505-514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.05.003

Chaffin M, Campbell C, Whitworth DN, et al. Accuracy of a Pediatric Behavioral Health Screener to Detect Untreated Behavioral Health Problems in Primary Care Settings. Clinical Pedatrics. 2017;56(5):427-434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922816678412

Grasso DJ, Felton JW, Reid-Quiñones K. The Structured Trauma-Related Experiences and Symptoms Screener (STRESS): Development and Preliminary Psychometrics. Child Maltreatreat. 2015;20(3):214-220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559515588131

Choi KR, McCreary M, Ford JD, et al. Validation of the Traumatic Events Screening Inventory for ACEs. Pediatrics. 2019;143(4):e20182546. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2546

Dubowitz H. The Safe Environment for Every Kid Model: Promotion of Children’s Health, Development, and Safety, and Prevention of Child Neglect. Pediatric Annals. 2014;43(11):e271-e277. https://doi.org/10.3928/00904481-20141022-11

Selph SS. Behavioral interventions and counseling to prevent child abuse and neglect: A systematic review to update the US Preventive services task force recommendation. Published online 2013. Accessed Aug 10, 2020. https://calio.dspacedirect.org/handle/11212/1307

Kimberg L, Wheeler M. Trauma and Trauma-Informed Care. In: Gerber MR, ed. Trauma-Informed Healthcare Approaches. Springer International Publishing; 2019:25-56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04342-1_2

Kia-Keating M, Barnett ML, Liu SR, et al. Trauma-Responsive Care in a Pediatric Setting: Feasibility and Acceptability of Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2019;64(3-4):286-297. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12366

Marsac ML, Kassam-Adams N, Hildenbrand AK, et al. Implementing a Trauma-Informed Approach in Pediatric Health Care Networks. JAMA Pediatrics. 2016;170(1):70. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2206

Rodriguez MA, Bauer HM, McLoughlin E, et al. Screening and Intervention for Intimate Partner Abuse: Practices and Attitudes of Primary Care Physicians. JAMA. 1999;282(5):468-474. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.5.468

Weinreb L, Savageau JA, Candib LM, et al. Screening for Childhood Trauma in Adult Primary Care Patients: A Cross-Sectional Survey. The Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;12(6). https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.10m00950blu

Blum RW, Bearinger LH. Knowledge and attitudes of health professionals toward adolescent health care. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 1990;11(4):289-294. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-0070(90)90037-3

Garner AS, Shonkoff JP, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e224-231. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2662

Frankenfield DL, Keyl PM, Gielen A, et al. Adolescent Patients—Healthy or Hurting?: Missed Opportunities to Screen for Suicide Risk in the Primary Care Setting. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2000;154(2):162-168. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.154.2.162

Igra V, Millstein SG. Current Status and Approaches to Improving Preventive Services for Adolescents. JAMA. 1993;269(11):1408-1412. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1993.03500110076039

Stancin T. Commentary: Integrated Pediatric Primary Care: Moving From Why to How. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2016;41(10):1161-1164. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsw074

Phipps E. Southeast Heights Community Profile Albuquerque, NM. Published online August 2009.

Writer EK| JS. Living dangerously in SE Albuquerque. Accessed Dec 19, 2019. https://www.abqjournal.com/1057743/residents-clean-up-southeast-abq-area.html

Stein BD, Adams AS, Chambers DA. A Learning Behavioral Health Care System: Opportunities to Enhance Research. Psychiatric Services. 2016;67(9):1019-1022. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500180

Abraham E, Blanco C, Castillo Lee C, et al. Generating Knowledge from Best Care: Advancing the Continuously Learning Health System. National Academy of Medicine. 2016;Discussion Paper.

Deming WE. Out of the crisis: Quality. Productivity and Competitive Position, Massachusetts, USA. Published online 1986.

Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, et al. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. British Medical Journal Quality & Safety. 2014;23(4):290-298. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862

Leis JA, Shojania KG. A primer on PDSA: executing plan–do–study–act cycles in practice, not just in name. British Medical Journal Quality & Safety. 2017;26(7):572-577. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006245

Coury J, Schneider JL, Rivelli JS, et al. Applying the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) approach to a large pragmatic study involving safety net clinics. BMC Health Serveries Research. 2017;17(1):411. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2364-3

Berwick DM. A primer on leading the improvement of systems. British Medical Journal. 1996;312(7031):619-622. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7031.619

Greene SM, Robert M, Reid J, Larson EB. Implementing the learning health system: From concept to action. In: 2013 by the Authors; Licensee MDPI.

Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, Kim J. Pediatric primary care to help prevent child maltreatment: the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) model. Pediatrics. 2009;123:858-864.

Dayton L, Agosti J, Bernard-Pearl D, et al. Integrating Mental and Physical Health Services Using a Socio-Emotional Trauma Lens. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care. 2016;46(12):391-401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2016.11.004

Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. Guilford Press; 2012.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge data entry student Sarah King, the Pediatric Integrated Care Collaborative, and Johns Hopkins University for their support on this project.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by The Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sala-Hamrick, K.J., Isakson, B., De Gonzalez, S.D.C. et al. Trauma-Informed Pediatric Primary Care: Facilitators and Challenges to the Implementation Process. J Behav Health Serv Res 48, 363–381 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-020-09741-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-020-09741-1