Abstract

The active participation of young adults with serious mental illnesses (SMI) in making decisions about their psychotropic medications is beneficial to their care quality and overall health. Many however report not expressing treatment preferences to psychiatrists. Qualitative methods were used to interview 24 young adults with SMI about their experiences making medication decisions with their psychiatrists. An inductive analytic approach was taken to identifying conceptual themes in the transcripts. Respondents reported that the primary facilitators to active participation were the psychiatrist’s openness to the client’s perspective, the psychiatrist’s availability outside of office hours, the support of other mental health providers, and personal growth and self-confidence of the young adults. The primary barriers to active participation reported were the resistance of the psychiatrist, the lack of time for consultations, and limited client self-efficacy. Young adults with SMI can be active participants in making decisions about their psychiatric treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Young adults with serious mental illnesses (SMI) who actively participate in making health care decisions gain a variety of benefits, from reduced symptoms and improved self-esteem to increased service satisfaction and improved adherence.1 , 2 Unfortunately, young adults have generally not been active participants in making decisions about the psychotropic medications they take, even though a large majority of them want at least a collaborative approach.1 , 2 Thus, this study was designed to explore the following research question: What are young adults’ perceived facilitators of and barriers to their active participation in making psychotropic medications decisions with their psychiatrists?

Young adult mental health care has drawn increasing interest from policy makers and researchers in the last 10–15 years. According to the GAO (2008), an estimated 2.4 million young adults aged 18 through 26 have a serious mental illness, approximately 6.5% of young adults living in US households.3 Approximately half of all lifetime mental disorders emerge by the time individuals reach their mid-teens and three fourths by their mid-20s.3 There is now a recognition that young adults with mental illnesses are at a particular developmental stage and thus have different service and support needs from older adults.4 Neither youth nor adult services have been appealing to young adults, resulting in relatively low service utilization even though the need is high.5

Besides individual therapy, the most common treatment provided to young adults is psychotropic medications.6 While medications can be beneficial, they frequently have emotional, cognitive, and physical side effects of sufficient magnitude to cause great discomfort and/or negatively impact the person’s lifestyle.7 For a young person, significant medication risks such as obesity are seen as particularly difficult in relation to their developmental life stage. Thus, young adults prescribed these medications have a significant rate of non-adherence.8 Because psychotropic medications by class are similarly efficacious, medication choice is preference-sensitive, meaning the best choice is how individuals value the risks, benefits, and side effects of treatments.7 Thus, medication treatment will be more effective when the client is an active participant—aware of the benefits and side effects profiles of medications and makes a choice based on that information.2

“Active” participation has been defined in several ways in mental health treatment.9 This definition is drawn from the work of Finfgeld, who defines active participation as utilizing one’s own capacity (knowledge, skills, and beliefs) to exert direct influence over decisions about his/her treatment.10 Finfgeld identifies two broad levels of active participation.9 , 10 At the “Choosing” level, the client expresses feelings about his/her treatment options and/or assertively selects from them. A higher level of participation is “Negotiating,” by which the client is able to not only take a position and express a treatment choice but also to reach a compromise with the provider who may start from a different position. This fourth level is characterized by a greater sense of mutual respect between the client and provider, and requires a heightened degree of effort and skill from both parties.

Many young adults with SMI find it difficult to engage in a treatment decision making process because of a self-stigma associated with their diagnosis that impacts their sense of agency and autonomy.11 Those who started treatment as youth often did not have role models to help them acquire the capacity to make complex decisions. And youth who have spent time in a locked hospital unit or been detained in the criminal justice system often are unaware that they have a right to participate.12 Their confidence to participate is particularly low when their schooling has been interrupted and/or they have not completed a degree.12 Some are challenged to enter into a decision making process because of cognitive and trust issues, particularly where anticipated outcomes are not well-defined.13

Young adults also face significant external barriers to active participation. Most prominent is the paternalism of many psychiatrists who believe that both mental illness and youth render a client largely incapable of making “good” treatment decisions, even in the face of research to the contrary.8 , 14 As a result, psychiatrists often do not ask their young adult clients about their preferences for involvement or about their values and preference regarding medications.15 Psychiatrists frequently do not provide sufficient information with which young people can make informed treatment decisions, often leaving out medication alternatives.1 The participation of young adults in medication decision making is thus often limited to providing information to the prescriber but not being part of deliberations.

Positive youth development (PYD) is an approach now used to empower youth and young adults to take an active role in decisions about their lives. With this approach, young people are provided with opportunities to set life goals that they find meaningful, and providers offer the support and direction to attain them.16 PYD and related research embrace the development of decision support tools for client independence and self-determination. This includes treatment decision aids, which provide concrete information about a health condition and the potential outcomes of different treatment options, helping the client to clarify his or her personal values.2 While these approaches to client activation have been tested and used with older adults with SMI, they have not with younger adults.17

The conceptual framework for this study is Finfgeld empowerment model for psychiatric treatment decision making (Fig. 1).10 This broad psychosocial approach is based on concept analyses and qualitative research findings and is consistent with Floersch’s framework on adolescents and psychotropic medication decision making.9 , 13

This empowerment model is based research that demonstrates that mental health outcomes are based not simply on the treatment provided but also on the wider context of the client’s and provider’s environment (Fig. 1). The Finfgeld model contains four interlinked categories: (1) antecedents, (2) barriers mitigated by health care providers (“barriers”), (3) attributes, and (4) outcomes. The “attributes” represent several “stages” or “levels” of patient activation, including the Choosing and Negotiating levels discussed above.9 The levels of activation are driven by interrelationships with the components of the other three categories: antecedents, barriers, and outcomes. In the antecedents category, there are systemic and individual prerequisites, including a patient’s capacity and willingness to be assertive in a medical decision making context. “Barriers” refers to factors that interfere with the development of an empowering relationship with a provider, including impaired cognitive ability, medication side effects, lack of motivation, and resistance of the psychiatrist. The empowerment model suggests that positive health outcomes such as symptom reduction will encourage active participation, and that more active participation will lead to improved health.

Recent studies have looked to understand the psychotropic medications perspectives of college students and of young adults with depression. This study is the first to examine the psychotropic medication decision making perspectives and experiences of young adults with SMI who have aged out of the adolescent mental health system. This descriptive study used qualitative methods in order to explore the facilitators of and barriers to the active participation of such young people in making medication decisions with their psychiatrists.

Study Methods

This is a cross-sectional qualitative study on young adult perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to active participation in psychotropic medication decisions. The sole method of data collection was interviews conducted by the primary Principal Investigator (PI) (first author) with young adults with SMI. All participants received an explanation of the research aims, study design, and risks and benefits of participation; voluntarily agreed to participate; and signed written informed consent forms. The Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Participants and recruitment

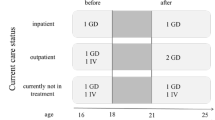

The study population consisted of English-speaking young adults (aged 18–30) currently diagnosed with a SMI who were active participants in making psychiatric medication decisions with their outpatient psychiatrists. SAMHSA’s definition of SMI is a mental or behavioral disorder of meeting diagnostic criteria specified within DSM-IV, and which has resulted in functional impairment which substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities.3 In this study, “functional impairment” is defined as having been on governmental disability benefits within the previous 5 years and/or having been hospitalized at least twice in the previous 10 years.18

A convenience sample of young adults was recruited through the posting and distribution of flyers in clinical and non-clinical settings in eastern Massachusetts. Interested participants called a toll-free number and were screened by the first author for eligibility according the inclusion/exclusion criteria stated above. Callers were asked a prescribed series of questions to screen them in or out based on the criteria listed above. With regard to their level of activation, callers were asked whether they had expressed a preference for a particular medication with their current psychiatrist and/or expressed disagreement with their psychiatrist about a prescription and reached a mutually acceptable decision; those answering “yes” to either were screened into the study. Of 42 callers, eight were screened out because they were not active participants with their current psychiatrist. If someone met the inclusion criteria, the screener scheduled a time to meet with the caller for an interview. Of 34 eligible scheduled, ten did not show up, for a total of 24 interviews conducted.

The mean age of the participants was 24 years (range = 19–30); 67% were female and 33% were male. Most were White. They all had been hospitalized psychiatrically at least twice during their adulthood (after 18 years of age) and had received therapy as an adolescent. The mean age of starting services was 13, with 25% before the age of 10. Most were seeing a therapist regularly (along with a psychiatrist). A large majority of clients were eligible for state-financed specialized support services, including housing and vocational supports. Remaining demographics are at Table 1.

Data collection

All interviews were conducted by the first author between May and October 2010. The in person 60-minute interviews took place at the person’s home, a nearby library, or a quiet coffee shop. Each person who agreed to participate had been provided with informed consent and signed a consent form. Twenty dollars was paid to each person completing the interview as compensation for time and transportation. Interviews were audio-recorded, professionally transcribed verbatim entered into HYPERRESEARCH software, and reviewed by the first author for accuracy.

The semi-structured interview guide was based on the Finfgeld (2004) empowerment framework. The interview schedule contained a series of four categories of cross-cutting questions about the barriers to and facilitators of active participation each with four to six questions (Table 2).

Additionally, respondents were asked to describe how they participate in decision making and the outcomes of that participation. Also collected by participant self-report were demographic information and treatment variables. Attentive listening and probing provided opportunities for the respondents to steer the discussion and/or for the interviewer to introduce new questions.

Data analysis

An inductive analytic approach was used to identify conceptual themes related to the factors impacting decisional participation in the transcripts.19 This study drew on the iterative and in-depth inductive process outlined by Ulin and colleagues: immersion, coding (broad labels related to study questions, followed by continuous content-driven coding), data reduction (identification of themes and subthemes), and interpretation.20

The primary PI immersed himself in the data by writing reflexive field notes after each interview to document his primary impressions of the interview and the respondent’s demeanor. After every five to six interviews, the Principal and the co-Principal Investigator (second author) met to review and discuss the field notes with respect to the following: (1) new and emerging codes, (2) saturation, (3) additional questions to pursue, and (4) questions to remove as not yielding significant information. Based on his knowledge of the topic at hand, the co-PI asked focused questions of the primary PI to generate new ideas. Several strong “activation” codes emerged in the first six to eight interviews, the most prominent being access to the psychiatrist outside of office hours. A codebook was created based on the Finfgeld framework and supplemented by emerging codes identified through the immersion process. Several questions were added to the interview guide around those topics, and several not yielding information were removed. The recruitment process ended upon the completion of 24 interviews, the point at which theoretical saturation had been achieved. Theoretical saturation takes place when “gathering fresh data no longer sparks new theoretical insights” pertaining to the research question.21

After data immersion, the primary PI used HYPERRESEARCH to assign initial open codes, create coding/analytical memos, and flag quotations representative of each code.20 Subsequent coding sessions were used to discern and confirm themes, to identify the categories that comprised them, and to delineate the interrelationships among the various codes and themes that emerged. An iterative process for identifying and modifying the themes was conducted through numerous readings and analyses of congruent transcript segments. The primary PI coded the data and consulted with the co-PI regarding the salience of emerging themes and categories.

The research software was used for data reduction, building a level of themes representing concepts from the data that shared common features.20 In this fashion, 38 preliminary codes were collapsed into 14 second-level themes. Eight final themes were developed by connecting and consolidating all of the second-level themes without loss of any key concepts. The primary researcher engaged in an interpretative process by reviewing the relevant literature and verifying the robustness of the analysis.

To enhance the quality of the research design, steps were taken to enhance its dependability and credibility.22 For dependability, a thick description of the study’s methodology is provided herein for the reader to make his/her own assessment. The researchers’ documentation of data collection and analysis also helps to ensure dependability. Credibility is based on the researchers’ ability to interpret qualitative data in a manner consistent with the data while having true value to readers.20

The first author was the sole data interviewer and coder and the primary data analyst for this research. There are various perspectives on the use of singular analysts with inductive content analysis.23 A singular analyst may be able to attain an in-depth analysis that a research team would be challenged to achieve since the team members would not have conducted all the interviews together and might not be equally invested in the study. Also, a principal investigator working within a team structure may need to compromise his/her more focused analysis in order to reach a consensus with his/her team members. On the other hand, a limitation of this analysis technique is the possibility for subjectivity and bias that may be introduced by a sole analyst. This limitation was addressed directly, as described in the previous paragraph, through continued reflexivity throughout the research and by discussing field notes and initial findings with the co-PI while the data were being collected and after data collection ceased.

Findings

Thematic analysis of respondent interviews identified three themes of barriers to and five themes of facilitators of achieving and maintaining active participation in psychiatric medication decision making (Table 3).

Client perspectives on facilitators to active participation

Psychiatrist’s openness to and/or direct interest in the client’s perspective on treatment

Respondents reported that their current psychiatrists expressed an openness to their perspectives on treatment. These psychiatrists demonstrated good listening skills, though not all of them made it a practice to ask directly for the client’s opinion. As one respondent noted: “She doesn’t treat you like a little kid, um, who doesn’t really know anything. She treats you like an adult. She gives you the impression that it’s important to her that she listen.” The respondents’ assessments here were buttressed by an existing trusting relationship with the psychiatrist, whom they respected and liked. At times, the psychiatrists may have disagreed with the client’s choice, but ultimately respected his/her right to make the treatment decisions. They didn’t just abandon the client, but worked with them as best as they could.

According to one respondent:

I wanted to go off meds. She said she didn’t want to do it but it was my decision and she’d help me do it a way that would be most effective, and we can catch anything if I have an issue. She told me to call if I was having any delusions to call the crisis line here; she wanted to make sure that nothing bad happens, or something, we can stop.

Clients who expressed a higher level of activation (i.e., not just expressing preferences but negotiating towards an agreed course of medication) reported that their psychiatrists had actively encouraged them to participate and express opinions, often early on in the relationship:

She said that she wanted to hear what I wanted to when we worked together. She would give me information about a medication, and it would be up to me if I should take it. And if I didn’t want to take it, we’d talk about it, and see if we could make that medication work by a change in dose or whether another treatment made sense.

Many of these psychiatrists even asked the client to describe what they saw as their problems, not focusing so much on a diagnostic category initially. This was essentially an “ice-breaker” that set the tone for the ongoing relationship.

Support of other mental health providers

Respondents generally had some level of functional disability and were thus eligible for an array of supportive or rehabilitative services by virtue of their being Medicaid eligible or their being a client of the state Department of Mental Health. Several of the respondents lived in group homes and/or had case managers, and attributed their active participation in making medication decisions in part to the assistance of that support staff. In some instances, staff offered to coach residents on how to interact with psychiatrists in a way that promoted their concerns and preferences, such as helping them writing down meeting preparation notes:

The [group home staff] encouraged me to write down what I wanted to say, or the questions I had. That way I didn’t have to verbalize it. Having that paper in front of me, I was able to bring up medication problems right when we first sat down.

When residents reported that the psychiatrist was a particularly dismissive person or the client remained nervous despite meeting preparation support, staff might attend the meeting with the client, and if necessary act as an advocate. In one case, a client informed his case manager that he was having a difficult side effect and his psychiatrist didn’t seem interested in discussing it. The case manager offered to drive him to the next appointment:

But by the time we got there I was a wreck; he offered to come up with me and I was for that. At the meeting, he was really insistent that I was suffering and there really should be some change in medication. There was tension in the room, but there didn’t seem to be any disagreement. And the medication was changed. I also felt I could be more honest with GH because of the case manager’s support, and that perhaps GH would take my concerns more seriously in the future.

A large majority of respondents were seeing a therapist for counseling. Therapy for them tended to include practical advice on dealing with life’s day to day difficulties and/or cognitive behavioral therapy. In some cases, the client used the therapist as a conduit to the psychiatrist because s/he had more time with the therapist. One respondent noted:

A lot of it’s talking to my therapist, and then my therapist reports that to my psychiatrist, so she can have a grasp of where I’m going. And then she [psychiatrist] just talks to me briefly, maybe even about topics that I talk to my therapist about. This is ‘cause she doesn’t have enough time to see me for long periods of time.

Personal growth leading to greater participation

Most respondents entered legal adulthood (e.g., age 18 or 19) as at best passive participants in most aspects of their mental health treatment decision making. When asked them how they had become more active over time, many could not specify any specific reason or action; more frequently, they referred to a process of “personal growth” that a person experiences during young adulthood. As one person noted: I think as I got older, I have more of a voice, now… I’ve been around the block a few times with a… you know, therapists and psychiatrists, and stuff like that. Like, I know how to get the help I need.

Several respondents did report that this growth could also be attributed in part to the encouragement of non-psychiatric treatment staff. One person reported that that his adolescent group home staff encouraged and taught him to be a more active participant. Sometimes, that growth could be attributed to the respondent’s increasing knowledge about medications.

Self-confidence

After aging out and over time, some of the respondents found psychiatrists who encouraged their participation in treatment decision making, a major boost to their confidence. Respondents also gained confidence generally through accomplishing tasks that demonstrated various competencies. One respondent commented that s/he didn’t have the confidence to actively participate until becoming educated both formally and through personal efforts:

She [the psychiatrist] made medication recommendations, and she would ask questions or share some concerns… but I still never tried to learn more my situation… so I didn’t have anything to recommend. All I had was my GED and I barely got that. Now I have an Associate’s degree…I had read books on my own, and started reading on the Internet, just got sharper. So I am more critical of the medications—they can cause serious side effects. Now I’m more likely to speak my mind.

Those who at times negotiated with their psychiatrist to an acceptable solution reported high levels of confidence. The actual act of “negotiating” in ways they had not previously raised their confidence level, as well as the “personal growth” reported in the previous section. As one respondent noted:

I was getting to know him and started to feel more comfortable talking about side effects as they occurred. He was OK with that, and we made changes together so I wouldn’t have those problems. I became more confident in myself and had faith in myself. Instead of being scared and worried, I would speak up when he recommended a medication change. Sometimes I didn’t like the side effects he mentioned, and I now say something, where before I wouldn’t have said much.

Growth in confidence also appeared to relate to a respondent’s gaining control over his/her life generally, even while struggling with illness.

Greater availability of psychiatrist, in and outside of the office

Several respondents reported that their current psychiatrists managed to make themselves more available to clients as needed, and this was more likely to occur with clients who reported the highest levels of activation. Some of these psychiatrists reported that they could obtain insurance company approval for longer or more frequent psychiatric meetings, but only by expending a great deal of time dealing with difficult forms and trivial details.

Respondents who were at a negotiating level of activation recognized that that their psychiatrists’ willingness to make him/herself available as needed for consultation or treatment was a critical component. These psychiatrists reportedly informed their clients of a specific way they could be reached (usually a phone number) if the client was having any serious problem. When a person called, the psychiatrist would get back in touch with him/her within 24 business hours and decide with the client for him/her to increase/decrease a dosage, to come in for an immediate appointment and/or plan to increase the frequency and/or length of future meetings. In one instance, a psychiatrist went out of his way to be both accessible and to assist his client with her housing situation:

And he’s like, ‘You know, call me, even with medication changes.’ And he gave me his pager number. He gave me his cell phone number… They wanted $4,000.00 down for two weeks at the residential program. He get me on the top of the list, to help my mental health state. It, it was absolutely amazing!

In essence, the negotiation was not solely office based, but also in the community where the client was experiencing the medication’s effects, and with that new information would re-negotiate at the next appointment or over the phone. As one client noted:

I told her pretty much up-front that I wanted to try to see if I could cope off my medication because of the weight gain and blood sugar issues which could be permanent. She said she wanted to see me for a couple of months before changing meds. And, eventually she helped me lower my medication. But it was small changes every two or three months. When I got to 75, I started having problems and ended up in the hospital. So I learned something, and I guess she did too.

Client reported barriers to active participation

Lack of time for office meetings

Respondents believed that the limited time they had to meet with their psychiatrist could be a major factor interfering with their active participation (referring almost always to previous psychiatrists). Respondents discussed this issue mostly in the context of the clinical appointment duration, which averaged 15 minutes. Psychiatrists informed many of these respondents that the shorter visits and limited time was due to health insurance requirements. Respondents reported that these meetings tended to be very structured around the psychiatrist’s need to prescribe medications that supported the client's stability. Aware of the psychiatrists desire to move quickly, respondents often do not feel comfortable “slowing down” the meeting by expressing a medication preference inconsistent with what’s being prescribed; they didn’t want to dissatisfy the psychiatrist and in some cases feared being dismissed out of hand. When respondents tried to discuss medication side effect issues in some detail, psychiatrists appeared bothered and seemed rushed to move on.

One participant reported:

I [would] go in there and she asks me how I’m feeling, if I’m still working, if the medications are helping, if I’m having any bad effects, and then if I have any questions about them. She may say she wants to change the medications and then at the end she’s typing out prescriptions. There really is not enough time for me give my opinion on the medications. I just kind of go with what she says since she’s very knowledgeable.

Respondents often reported that office visits with previous psychiatrists were too infrequent, and they didn’t believe s/he could talk to that psychiatrist in the interim. Some had specifically asked psychiatrists for more frequent visits, but the psychiatrists often reported that s/he did not think it was necessary or possible due to insurance restrictions.

Psychiatrist’s resistance to the client perspective

Many of the respondents described relationships with previous psychiatrists who resisted or showed a deep disinterest in client participation. In general, resistant psychiatrists were described as poor listeners, rigid, careless, and/or inaccessible. As one person noted: “He wouldn’t listen to anything. He didn’t do anything. With Depakote, when I needed my blood test, he never got my blood test. He never rescheduled my appointments, he just didn’t do ANYTHING for me.”

Some psychiatrists were seen as having a very rigid approach to meetings, leaving very little time for actual discussion about the client’s short- and long-term goals. In some cases, psychiatrists were perceived as being so focused on the client’s short-term mental stability, that the client’s overall wellness didn’t seem to matter. This could occur even when a client brought up a specific concern about a medication to the psychiatrist:

His big thing was, ‘It doesn’t matter if you end up having other side effects from the medication. You’ve gotta deal with those, as long as the medication’s working.’ And I was starting to have blood sugar issues and hypoglycemic attacks. He didn’t want to help me lower or get off my meds.

Limited self-efficacy

“Self-efficacy” is the product of the client’s knowledge and confidence to be an active participant in treatment decision making. Most respondents reported as they had entered the adult mental health system at ages 18 or 19 with limited to no self-efficacy. Many reported that as adolescents they did not have input into treatment decisions because their parents and/or their psychiatrist made those decisions. Thus, they didn’t have experience making informed choices or even knowledge of their legal rights to do so as an adult. They lacked both the confidence and skills to be active participants.

As one respondent noted:

I just didn’t know I could choose which medications I could be on or that I could refuse at all. I continued to see my child psychiatrist when I became an adult, but nothing changed. He kept telling me what I should take… and that was it. So I just didn’t know it was my decision. So I just kept on listening to him. Now I give what I put into my body a lot of thought.

Such instances resulted in great frustration for clients, who generally reported that at the time they had neither the means nor knowledge to find a new psychiatrist, and they would settle into an apathetic funk: “It was frustrating. I knew it wasn’t working. But I was 19 and didn’t know what my options were. I didn’t know that I could call Medicaid and ask for another psychiatrist. I just went along with it… I’m glad I learned I could do this.”

Additional considerations

Although participants were asked about family involvement in medication decision making, no specific theme of family as a barrier or facilitator emerged in this data set. The data did show that when parents joined meetings with the psychiatrist they could be formidable allies to the client.

Most respondents reported using the Internet to review information on medications already prescribed by the psychiatrist. They did so in order to clarify their expectations for a medication’s potential side effects and risks or to check out a current health concern as a side effect. Most of these respondents didn’t reference the Internet information sources during their psychiatric meetings. They didn’t think their psychiatrist would react negatively to Web references, but they also did not see the value of making a Web reference.

A large majority of respondents used the Internet to learn more about their mental illness or their health generally. Many of them relied on the website WebMD for their information needs and considered it a reliable source. WebMD is a comprehensive and the most popular source of medical and health information, featuring specific search options, a section on prescription drugs, and the latest headlines from medical and health communities.24

Discussion

The present study offers first time empirical evidence of perspectives of young adults (ages 18–30) with serious mental illnesses who have aged out of the adolescent system on their barriers and facilitators to active participation in decisions about psychiatric medications. Recent studies on the adult SMI population have focused on the high barriers to active participation, with less focus on facilitators because most of the samples have not been active participants.25 This study has been able to provide a full account of those facilitators because it is the first to present perspective from clients who have become active in the medication decision making process.

The findings reported herein are consistent with those of Drake and colleagues, who described three categories of barriers towards promoting client participation decision making in mental health: (1) the clinician’s reluctance and/or lack of training; (2) the person with SMI lacking “information, empowerment, motivation, and self-efficacy”; and (3) the lack of computer infrastructure to support client decision support and clinician training.2 A significant ongoing barrier for young adults in particular has the deep tradition of psychiatric paternalism, in which clients are seen as irrational by the very nature of their illness.14 Many psychiatrists have demonstrated limited awareness that young adults with SMI have a right to informed consent—that is, to make treatment decisions based on the best evidence of a treatments benefits, side effects, and alternatives. Psychiatrists are further constrained by the perceived limited amount of time they are paid to spend with their clients.26

This study’s findings are also generally consistent with recent studies which focused on young adults with major mood disorders.1 , 15 Many clients lack the knowledge, confidence, and support to be active participants in their care.15 This lack of self-efficacy among many youth transitioning from the adolescent system stemmed from a child/adolescent system with constricted choices and rules.4 Upon reaching the age of capacity, some young adults take advantage of new freedoms to become aware of to become more inquisitive and assertive. This process is critical to young adults with SMI because often their social development, formal schooling, and vocational growth have been impeded.15 With early opportunities to learn about their role as responsible adults, these young adults may experience “personal growth” or maturation.5 The best opportunities for growth present when they find psychiatrists who reduce professional boundaries, engage in respectful and caring communications, and encourage the client to participate as collaborator.8 A by-product or component of these respondents’ improved self-efficacy was their achieving greater control over their life and psychiatric condition.10

There are two findings that are new to the literature. The first is the positive impact of psychiatrists on activation when they make themselves available outside of office hours. Beyond the relief this provides to clients when faced with difficult medication side effects, it sends a clear message to clients that the psychiatrist really cares about them. A second interesting finding is the positive role other providers can play in enhancing the client’s voice in treatment decisions as coaches, advocates, and supporters.

Study Limitations

This study has some important limitations. The small sample of respondents, all young adults, suggests caution in making inferences to other populations. In addition, companion data regarding the perspectives of their psychiatrists were not included in this study. There are various perspectives on the use of singular analysts with grounded content analysis.23 A singular analyst may be able to attain an in-depth analysis that a research team would be challenged to achieve since the team members would not have conducted all the interviews together and might not be equally invested in the study. Also, a principal investigator working within a team structure may need to compromise his/her more focused analysis in order to reach consensus with his/her team members. On the other hand, a limitation of this analysis technique is the possibility for subjectivity and bias that may be introduced by a sole analyst. However, this limitation was addressed directly, through continued reflexivity throughout the research, and by discussing field notes, code assessments, and themes with the co-PI during and after the data were being collected.

Implications for Behavioral Health

The results of this study identify important implications for behavioral health providers who work with young adults. Even those psychiatrists who express a desire for a more collaborative relationship often qualify that desire with their pessimism for achieving that result, in part due to systemic limits placed on the amount of time they can spend with clients.26 Nevertheless, studies have shown active client participation in treatment decision making can take place without increasing the length of consultation time when the psychiatrist is a skilled communicator or the client has access to a good decision support tool.27 Psychiatrists encourage activation by their willingness to reduce the relationship’s power imbalance and by relinquishing control in order to compromise.10 As broadly stated by Finfgeld, this is not a light undertaking: “Health care providers are urged to accept the trial-and-error approach, provide meaningful feedback if needed, and be prepared to rescue clients when necessary.”10, p. 47 Training, education, and mentoring for psychiatrists on incorporating client preferences in decision making should include approaches to taking and expressing an interest in their client’s life, encouraging the client to take an active role in treatment, and negotiating with the client when there is a disagreement.

For young adults, medication decisions do not stop when the office door closes. They continue to experience both positive and negative medication effects in unexpected ways outside of normal office visits, gathering information that can enhance decision making. As that new information is accrued, an accessible psychiatrist to approve or otherwise negotiate a good solution is critical to an active client role. To the degree that psychiatrists’ have limited availability, one way to improve access to prescribers is the expansion of the use of nurse practitioners, who have prescribing power and are less costly than psychiatrists.28 Many clients have reported that outpatient nurses seem to be better listeners and more nurturing.28 In addition, researchers and psychiatrists have recommended the use of inter-professional team-based approach to maximizing client contact time.29 Here, the psychiatrist acts in close collaboration with other psychiatrists, nurses, case managers, and paraprofessionals to treat a group of patients. The economies of scale allow the team to triage client contacts and to have staff available who are familiar with the client’s situation.29

This inter-professional team model includes decision coaches, health professionals not involved in the treatment decision who prepare the client to share their preferences with their physician.30 Peer specialists, paraprofessionals who have an SMI and inspire and support the client’s recovery process, could also be capable coaches.17 A promising decision support approach for youth with serious mental health conditions is the “Achieve My Plan” (AMP) coach, whose goal is to increase the youth’s participation in the group-based Wraparound service planning process.31 This coaching model has been shown to improve the youth’s perception of improved planning participation and could presumably be used for medication decisions.31

Some of most promising approaches for young adults in particular are technology-driven solutions, including electronic web-based decision supports and the networked communications.32 These interventions place the client in the driver’s seat, with access to information and time to process it. The Internet was a popular source of health information for this study’s respondents, as it is for a large majority of young adults.33 In addition the broad adoption of mobile phones and the accelerated uptake of social networking sites among young people indicate these as key areas for further study. Current research is focusing on assessing the level of interactivity and other website characteristics that will encourage young adults to use electronic decision supports more frequently and in a way that supports active participation.33

For young adults with SMI, parents can be a strong decision support ally. Strong family relationships are associated with much better outcomes for these young adults.34 The literature does show that most parents are in favor of opportunities for young people with SMI to engage in skill development and mentoring relationships. Some parents have doubts about their child’s capacity for managing their treatment and/or or understanding the nature of their condition.35 But regardless of medication preference, young adults’ participation in treatment decision making can have positive effects.1 Parents can be educated on this matter, often through family psycho-education or in family therapy.

In this exploratory paper, young adults with mental illness who have achieved active participation have given us important information for including them in medication treatment decisions. Their active involvement in policy development, research, and as health workers (e.g., peer mentors) is essential to drive these changes.36

References

Simmons MB, Hetrick SE, Jorm AF. Experiences of treatment decision making for young people diagnosed with depressive disorders: a qualitative study in primary care and specialist mental health settings. BMC psychiatry 2011; 11(1): 194.

Drake RE, Deegan PE, Rapp C. The promise of shared decision making in mental health. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2010 34(1): 7-13.

United States Government Accountability Office. Young Adults with Serious Mental Illness: Some States and Federal Agencies are Taking Steps to Address Their Transition Challenges. Washington, DC: 2008.

Davis M, Vander Stoep A. The transition to adulthood for youth who have serious emotional disturbance: Developmental transition and young adult outcomes. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 1997 24(4): 400-427.

Jivanjee P, Kruzich J, Gordon LJ. Community integration of transition-age individuals: views of young with mental health disorders. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 2008; 35(4): 402-418.

Pottick KJ, Warner LA, Vander Stoep A, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outpatient Mental Health Service Use of Transition-Age Youth in the USA. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 2013: 1-14.

Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, et al. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis The Lancet 2009; 373(9657): 31-41.

Simmons MB, Hetrick SE, Jorm AF. Making decisions about treatment for young people diagnosed with depressive disorders: a qualitative study of clinicians' experiences. BMC Psychiatry 2013; 13(1): 335.

Cortes DE, Mulvaney-Day N, Fortuna L, et al. Patient–Provider Communication Understanding the Role of Patient Activation for Latinos in Mental Health Treatment. Health Education & Behavior 2009; 36(1): 138-154.

Finfgeld DL. Empowerment of individuals with enduring mental health problems: Results from concept analyses and qualitative investigations. Advances in Nursing Science 2004; 27(1): 44-52.

Kranke DA, Floersch J, Kranke BO, et al. A qualitative investigation of self-stigma among adolescents taking psychiatric medication. Psychiatric Services 2011; 62(8): 893-899.

Munson MR, Scott Jr LD, Smalling SE, et al. Former system youth with mental health needs: Routes to adult mental health care, insight, emotions, and mistrust. Children and Youth Services Review 2011; 33(11): 2261-2266.

Floersch J, Townsend L, Longhofer J, et al. Adolescent experience of psychotropic treatment. Transcultural Psychiatry 2009; 46(1): 157-179.

Adams JR, Drake RE. Shared decision-making and evidence-based practice. Community Mental Health Journal. 2006; 42(1): 87-105.

Munson MR, Jaccard J, Smalling SE, et al. Static, dynamic, integrated, and contextualized: A framework for understanding mental health service utilization among young adults. Social Science & Medicine 2012; 75(8): 1441-1449.

Bruns EJ, Rast J, Peterson C, et al. Spreadsheets, service providers, and the statehouse: Using data and the wraparound process to reform systems for children and families. American Journal of Community Psychology 2006; 38(3): 201-212.

Deegan PE. A web application to support recovery and shared decision making in psychiatric medication clinics. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2010;34(1):23-28.

Farrell SP, Mahone IH, Guilbaud P. Web technology for persons with serious mental illness. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 2004; 18(4): 121-125.

Pierce PF, Hicks FD. Patient decision-making behavior: An emerging paradigm for nursing science. Nursing Research 2001; 50(5): 267-274.

Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley EE. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. John Wiley & Sons, 2004

Charmaz K, Belgrave, LL. Modern Symbolic Interaction Theory and Health. In: WC Cockerham (Ed.) Medical Sociology on the Move. Netherlands: Springer, 2013, pp. 11-39.

Mertens DM, McLaughlin JA. Research and Evaluation Methods in Special Education. Corwin Press, Thousand Oaks; 2004

Rennie DL, Fergus KD. Embodied categorizing in the grounded theory method methodical hermeneutics in action. Theory & Psychology 2006; 16(4): 483-503.

Kavathe RS. Patterns of access and use of online health information among Internet users: a case study [dissertation], Bowling Green State University; 2009.

Seale C, Chaplin R, Lelliott P, et al. Sharing decisions in consultations involving anti-psychotic medication: a qualitative study of psychiatrists’ experiences. Social Science & Medicine 2006; 62(11): 2861-2873.

Torrey WC, Drake RE. Practicing shared decision making in the outpatient psychiatric care of adults with severe mental illnesses: redesigning care for the future. Community Mental Health Journal 2010; 46(5): 433-440.

Loh A, Simon D, Wills CE, et al. The effects of a shared decision- making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling 2007; 67(3): 324-332.

McCann T, Boardman G, Clark E, et al. Risk profiles for non‐adherence to antipsychotic medications. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 2008; 15(8): 622-629.

Légaré F, Stacey D, Gagnon S, et al. Validating a conceptual model for an inter‐professional approach to shared decision making: a mixed methods study. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 2011; 17(4): 554-564.

Stacey D, Kryworuchko J, Belkora J, et al. Coaching and guidance with patient decision aids: A review of theoretical and empirical evidence. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2013; 13(Suppl 2): S11.

Walker JS, Pullmann MD, Moser CL, et al. Does team-based planning “work” for adolescents? Findings from studies of wraparound. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 2012; 35(3): 189.

Sutcliffe P, Griffiths F, Sturt J, et al. The use of communication technologies for the engagement of young adults and adolescents in mental healthcare. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2011; 65(Suppl 2): A15-A15.

Andrews SB, Drake T, Haslett W, et al. Developing web-based online support tools: the Dartmouth decision support software. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 2010; 34(1): 37-41.

Podmostko M. Tunnels and cliffs: A guide for workforce development practitioners and policymakers serving youth with mental health needs. Washington, D.C. National Collaborative on Workforce and Disability for Youth, Institute for Educational Leadership, 2007

Mahone IH, Farrell S, Hinton I, et al. Shared decision making in mental health treatment: qualitative findings from stakeholder focus groups. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 2011; 25(6): e27-e36.

Delman J. Participatory action research and young adults with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 2012; 35(3): 231.

Conflict of Interest

I declare no conflict of interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Delman, J., Clark, J.A., Eisen, S.V. et al. Facilitators and Barriers to the Active Participation of Clients with Serious Mental Illnesses in Medication Decision Making: the Perceptions of Young Adult Clients. J Behav Health Serv Res 42, 238–253 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-014-9431-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-014-9431-x