Abstract

This study tested components of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) Risk Reduction Model (ARRM) for a sample of methamphetamine-using offenders in drug treatment. Analyses included the first two stages of the ARRM, problem recognition and intention to reduce risk (potential precursors to later possible behavior change), assessing predictors of intentions to increase condom use, reduce other sexual risk, and disinfect needles. Path analysis results showed potential applicability of the ARRM as a basis for intervention development for this population. There was a consistent effect of self-efficacy for risk reduction strategies, as well as direct or indirect effects of problem recognition factors (AIDS knowledge, peer norms), on the three intention indicators. Prior sex risk behavior (condom use) was directly negatively related to intention to use condoms; prior needle use was indirectly negatively related to intention to disinfect. Intention to use condoms was lower for women. Results can help identify areas for intervention development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Drug treatment programs are a common setting for HIV prevention because they are an access point for large numbers of high-risk drug users of diverse characteristics. They also are venues that allow staged multisession interventions to be delivered efficiently to treatment clients. Recently, the diversion of a large population of drug-using offenders into the publicly funded addiction treatment system (instead of incarceration) in California since 2001 is requiring adaptation of services to this potentially high-risk group. One significant challenge has been to accommodate the needs of the large proportion of methamphetamine (MA)-using offenders entering treatment, among which human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV) risk behaviors are common. The possible public health importance of reducing HIV risk among the population of MA-using offenders is suggested by the size of this group (about 25,000 per year in California), the substantially higher HIV prevalence among prison populations and among MA-using subpopulations than in the general population,1–5 and the high rates of HIV risk behaviors among offenders and among MA users.6–12

While intervention development has focused primarily on risk reduction for some MA-using subgroups such as men who have sex with men (MSM), HIV risk reduction among heterosexuals who use MA and, more specifically, MA-using offenders has received less attention. The current study focuses on intentions to use condoms, other safe sex strategies, and to disinfect injection devices in this potentially high-risk population and also addresses selected factors that may facilitate or inhibit these intentions.

An approach to developing HIV risk reduction interventions has been to identify “leverage” points in the structure of behavior change that would be amenable to intervention. The acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) Risk Reduction Model (ARRM) has been applied as a theoretical framework to examine and identify the predictors and structures of change in risk behaviors and possible leverage points for intervention.13–17 In the current study, the application of the ARRM has been extended to MA-using offenders to identify specific predictors and structures of precursors to change in HIV-related risk behaviors.

This study focuses on a population with a confluence of risk behaviors (crime, MA use, and HIV risk behaviors) and whose treatment participation may provide a critical opportunity for intervention to reduce those behaviors. Specifically, this analysis examines an ARRM-based path model of relationships among problem recognition factors (including AIDS knowledge, perceived HIV infection risk, and peer norms), constructs influencing commitment to change (including self-efficacy for risk reduction, response efficacy, and enjoyment of risk reduction strategies), and the expressed intention to change HIV-related sexual and injection risk behaviors.

Substance Abuse and Crime Prevention Act

Because in part of favorable research findings regarding the potential benefits of substance abuse treatment, California voters passed Proposition 36, which was enacted into law in 2001 as the Substance Abuse and Crime Prevention Act (SACPA). This law allows adults convicted of nonviolent drug offenses and who meet other SACPA eligibility criteria to be sentenced to probation with drug treatment instead of incarceration or probation without treatment. Since SACPA implementation, more than 250,000 drug offenders have been referred to treatment through SACPA referral. About two thirds are men, most have been using drugs for more than 10 years, although half have never received drug treatment before, and more than half report MA as their primary drug problem, a proportion that is continuing to increase.18

HIV prevalence in California prisons is estimated at 0.7%, about four times higher than in the California general population (0.017%)1,19; for the nation as a whole, the rate of HIV infection in prisons is about five times higher than in the general population.1,8 No rates are available specifically for the SACPA offender population. However, their convictions place them as potential prisoners; in addition, half have prior convictions, and 14% have been in prison and 36% in jail during the 30 months before their SACPA assignment.18

To be effective, HIV risk reduction strategies must be tailored to target an identified population and their specific behaviors and the psychosocial factors associated with such behaviors; otherwise, interventionists are likely to be “shooting in the dark.”20 Little is known about HIV attitudes, knowledge, and risk behaviors among the SACPA population overall and specifically of MA-using offenders.6 With a legislative renewal for funding for another 5 years, SACPA is maturing into an established criminal justice diversion option for drug offenders in California. Understanding possible opportunities for HIV risk reduction strategies, particularly among the little understood group of heterosexual MA-using offenders, can help stakeholders appropriately modify the program to improve its effectiveness in this important area.

Methamphetamine Use and Related Risk Behaviors

MA use is continuing its geographic penetration across the USA. Nearly half of county law enforcement officials in the USA now report that MA is the primary drug problem in their communities.21 Although injection users of heroin have been the primary focus of much of the HIV intervention research with drug users,22 the primary drug of abuse among treatment clients in California (especially among SACPA treatment clients) is MA. In California, the number of treatment admissions for MA increased sevenfold from 1992 to 2005, accounting for 36% of all admissions in fiscal 2006/2007.23–26 Half the SACPA participants reported MA as their primary drug.18

HIV prevalence is higher among certain MA-using subgroups than for the general population, with estimates ranging from 4 to at least 61% (e.g., 4% among heterosexual MA injectors in California, 9% among female MA injectors in San Francisco,4 14–61% among MSM MA users).3,5 Concordantly, HIV risk behaviors are common among users of illegal drugs and among at least some (thus far studied) MA-using subgroups.11,12,27–30 For example, Brecht et al.31 found that nearly half the individuals in a cohort who received treatment for MA use reported injection drug use at some point in their drug use history. The past year injection use was about 20% for users of MA in other studies of treatment populations.31,32

High levels of sex risk behaviors also appear typical among individuals who use MA, consistent with the physiological and psychological properties of MA.33–35 The majority of studies of MA use and sex risk, however, have utilized samples of MSM.36,37 This prior focus is consistent with the historically higher incidence and prevalence of HIV among MSM and with the use of MA as part of the cultural landscape of some MSM subpopulations. While HIV prevalence has remained lower in most heterosexual subgroups than among MSM, recent research also indicates that heterosexuals who use MA also engage in high-risk sexual behaviors.9,12,38 For example, studies of heterosexual drug users have shown that those who used MA were more likely than users of other drugs to report engaging in anal sex, having intercourse with an injection drug user or sex worker, having more sexual partners, and less frequent condom use.10,38 Moreover, both male and female MA-using injection drug users have been found to engage in more acts of vaginal intercourse, and MA use was found to be an independent predictor of less frequent condom use.39 Finally, based on Centers for Disease Control surveillance data, heterosexual exposure to HIV remains a major route of transmission, with about 13% of adult/adolescent men and 72% of women currently living with HIV or AIDS having been exposed through high-risk heterosexual contacts,1 and with significantly increasing numbers of annual cases among certain subpopulations such as Hispanics (both men and women).40 In particular, offenders both when institutionalized or on community supervision have been called a “hidden” HIV risk group, as their HIV risk behaviors have been less extensively studied than some other risk groups.41

AIDS Risk Reduction Model

The ARRM has led to useful empirically supported insights regarding leverage points for risk behavior change and has identified correlates of HIV risk behavior that should be considered in designing interventions.13,17,42 Our version of a simplified schematic of the ARRM appears in Figure 1 (see also the Catania et al.13 diagram). From the ARRM perspective, behavior change is viewed as a process occurring in three major stages. In stage 1 (problem recognition), people arrive at the perception that their behavior is placing them at risk for HIV infection, through such constructs as AIDS knowledge, perceived infection risk or susceptibility, and social context. Then, based on that recognition, in stage 2 (development of commitment to change behaviors), they develop a commitment (i.e., an intention) to change, dependent on and facilitated through such constructs as self-efficacy with respect to risk reduction strategies and response efficacy (i.e., whether a given course of action can produce a particular attainment).43 Finally, in stage 3 (enactment or behavior change), they act on their commitment to effect behavior change by taking action, for example, by adopting condom use and other safe sex strategies, disinfecting needles used by others, or avoiding use of “dirty” needles. The process may also be influenced by individual characteristics (e.g., gender, ethnicity, past history of risk behavior) or by other aspects of the external context. The ARRM can explicitly guide the search for leverage points at which intervention may directly or indirectly affect behavior change.

The ARRM has been applied to data on sexual and injection behaviors among several groups of drug users.15–17,44 These studies have identified both direct and indirect effects across the stages of the model for both sexual and injection risk behaviors among substance users. The ARRM has also been used as the basis for developing HIV risk reduction interventions45–50 (see also recent reviews in Lyles et al.51 and Herbst et al.52), but few studies have focused specifically on heterosexual MA users. Furthermore, the relatively high prevalence of risk seeking and impulsivity among individuals who use MA calls into question the applicability of interventions built solely upon reason-based models.36,53–55 Thus, assessing the applicability of models such as ARRM is warranted to examine the process involved in risk behavior change specifically for populations who use MA.

While the current study is not a longitudinal study with follow-up that allows observation of actual change in risk behaviors, it does allow focus on the relationships from the first two stages of the ARRM. Our analyses represent a first step in assessing ARRM applicability to MA users and can suggest intervention focus for influencing later possible behavior change. Future longitudinal studies can then expand analyses to include all three stages of the model for a more comprehensive understanding of the process of change. Beyond the importance of the commitment (intention to change) stage within the theoretical model, possible clinical implications of examination of the first two stages of the model rest on the assumption that increasing commitment (intention to change risk behaviors and influences on that intention including self-efficacy, response efficacy, and enjoyment of risk reduction strategies) will ultimately lead to a reduction of risk behavior. That theoretical relationship of commitment/intention to subsequent actual behavior change has formed a basis for the development of HIV risk reduction interventions targeting components of commitment (e.g., self-efficacy), with subsequent related behavior change.48,56–58 Several additional studies have provided empirical support for the stage 2 (commitment/intention and/or its components such as self-efficacy) to stage 3 relationships (actual behavior change). For example, Longshore et al.17 found that commitment to safe sex strategies was a significant predictor of lower sex risk-taking behavior at follow-up for both men and women substance abusers. Other examples of studies showing relationships between commitment/intention and subsequent behavior change include Anderson et al.,59 Bowen,60 and Sanderson and Yopyk.61 Conner et al.14 found that self-efficacy (one of the commitment facilitators) was a predictor of subsequent condom use behavior among offenders in substance abuse treatment. Other examples supporting a relationship (direct or indirect) of self-efficacy with subsequent behavior change include Heeren et al.,62 Naar-King et al.,63 Robertson et al.,64 and Sanderson and Yopyk.61

The treatment milieu is an optimal setting for the efficacious and cost-efficient delivery of HIV prevention protocols targeting sexual and injection risk behavior among MA users. Most theory-based HIV-preventive interventions target psychosocial “leverage points,” i.e., cognitive, emotional, and interpersonal factors strongly associated with HIV risk behavior and potentially amenable to change. Numerous studies have shown that treatment-based interventions are effective in promoting injection risk reduction but have had less than consistent success with sexual behavior.52,65–67 While some studies have provided evidence of sex risk reduction for specialized interventions for gay men who use MA,36,53–55,68 little research has focused on interventions specifically for heterosexual MA-using offenders.

Methods

Sample

The sample comprises the first 163 cases (i.e., subjects with data processed to date, recruited in 2006 and 2007) of a study of risk behaviors among heterosexual MA-using offenders referred to substance abuse treatment through the California SACPA offender diversion program. Subjects were approached for possible study participation while they awaited intake processing for treatment at the Kern County processing center in Kern County, CA. Kern County is located in central California, is the third largest county geographically in the state, and is a combination of growing urban (e.g., city of Bakersfield) and rural agricultural areas. The county population is approximately 50% racial/ethnic minority. Study participation was voluntary; eligibility included SACPA referral to treatment and MA use self-reported as the offenders’ primary drug. Study participants completed informed consent and were given a $20 grocery store gift card for their participation in an interview, which included questions on sexual and injection risk behaviors, substance use history, risk taking, impulsivity, and basic demographics. The study procedures were approved by the University of California—Los Angeles Institutional Review Board.

Measures

A parsimonious subset of background variables was examined for inclusion in the model. Earlier application of the ARRM on drug users’ data suggested possible differences in relationships by gender and previous risk behaviors,17 and additional variables that might impact intervention development were also examined for possible inclusion in the models as background control variables. Demographics included gender, age, and education (high school graduate or higher vs less than high school). Race/ethnicity was included as a five-category variable coded as follows: non-Hispanic white, African-American, American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic, and Other. Where subjects indicated two race/ethnicities, they were categorized for this analysis into a single minority category in the following order if listed: African-American, American Indian/Alaska Native, or Hispanic. Those listing other ethnicities or more than two ethnicities were combined into the “Other” category. For the path model analysis, African-American, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Other categories were combined into a more comprehensive “Other Races” category. Background substance use history was included as age first MA use, MA use during the past 6 months, any previous heroin use, and any previous cocaine use. Two dichotomous measures indicated prior risk behavior: (1) prior risky sex behavior during the previous 6 months (0 = no sex partners or always used condoms, 1 = any unprotected sex) and (2) any prior injection drug use (0 = no injection use, 1 = injection use). Preliminary bivariate analyses showed nonsignificant relationships of age, education, recent MA use, and cocaine use with intention outcomes and also showed multicollinearity of heroin use with baseline risky injection behavior; thus, for parsimony, these background variables were not included in the path model.

Two instruments contributed items for creating construct scores for the ARRM factors: HIV/AIDS Risk Assessment and the AIDS Knowledge and Attitudes Form.69,70 Most items used Likert-type scales (e.g., 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree); a few items used other scoring as described below. Relevant item scores were averaged to form composites as developed in earlier risk behavior papers.15–17 Participants with no sexual partners in the previous 6 months or no reported injection use were assigned the lowest risk scores for items specific to condom or injection use, respectively. Note that fear of AIDS has been included as a recognition construct in previous applications of the ARRM; however, this construct was not significantly related to intention measures in the current data and was not included in this analysis.

Problem recognition

AIDS knowledge was created as the average of ten items, with a higher score indicating more knowledge. Examples of items included “Only gay men get AIDS” (reverse scored) and “You cannot get AIDS by sharing food.”

Perceived infection risk was a composite of four items plus an additional score indicating perceived probability of personal infection risk across five specific behaviors (ranging from 1 = very unlikely to 4 = very likely). A higher score indicated greater perceived personal HIV risk. An example item was “I’ve already done things that could have exposed me to AIDS.”

Peer norms was composed of six items related to behavioral norms for injection and sexual risk reduction. Example items included “The drug users I know will clean their works before shooting up” and “My friends are not being careful about sex and the risk of AIDS” (reverse scored). Higher scores indicated greater peer concern about HIV risk behaviors and/or peer use of risk reduction strategies.

Partner preference for condom use included four items. An example item was “My main partner wants to use condoms for oral sex.” Higher scores indicated greater partner preference for condom use.

Commitment facilitators

The Commitment (or Intention) stage of the ARRM was considered in two parts, as previously examined by Longshore et al.17 The first part consisted of commitment facilitators, including self-efficacy, response efficacy, and enjoyment of risk reduction strategies; these commitment facilitators/barriers, in turn, are hypothesized to predict intention to change risk behaviors. The commitment facilitators thus become intervening variables in the current path model, forming potential direct and indirect paths between problem recognition and the intention outcomes in the current analysis.

Two self-efficacy composites were created reflecting the participant’s confidence in his/her ability to exert control over risk taking: one for sexual risk reduction strategies (five items) and one for needle risk reduction strategies (four items). Item examples include “Using a condom is easy for me” and “It’s easy for me to clean my works with bleach” for the two scales, respectively. Higher scores indicated greater self-efficacy with respect to using risk reduction strategies.

Response efficacy indicated perception of the efficacy of specific risk reduction behaviors. This scale was created from four items, including “People who share ‘dirty’ works are at greater risk of getting AIDS” and “Using a condom (barrier) reduces the chance of spreading AIDS.” Higher scores indicated greater perceived response efficacy.

Enjoyment of risk-reduction strategies was created from 13 items relating to enjoyment/comfort of specific sexual and injection risk reduction behaviors. Higher scores indicated greater enjoyment of these strategies. Items included “Using condoms (barriers) can make sex more stimulating” and “When I’m shooting up, I enjoy it more if I have already cleaned my works with bleach.”

Commitment (intentions)

Three measures indicating commitment/intention to use risk reduction strategies for different types of behavior were included, specific to condom use, other safer sex strategies (including partner behavior), and disinfecting needles. Higher scores indicated greater intention to use the risk reduction strategies. Intent to use condoms was a composite of two items, including “In the future I will use a condom (barrier).” Intent to use other safer sex strategies was a composite of two items: “In the future I may have sex with someone I don’t know at all” (reverse scored) and “In the future I will not have sex with anyone I know to be an IV drug user.”

Intent to disinfect was a composite of five items indicating intention to disinfect and/or to reduce injection use. An example was “From now on, if I inject drugs I will always disinfect the works before using them.”

Analysis

Relationships among problem recognition, commitment facilitators, and commitment/intention variables were considered as a path model. For parsimony, a separate model was examined for each of the three commitment/intention outcomes. The separate analyses also allowed inference of common pathways across the models to identify both common and distinct leverage points that should be considered for intervention development. Analyses used the EQS structural equation modeling program, which compares a proposed theoretically based hypothetical model with a set of actual data.71 The closeness of the variance–covariance matrix implied by the hypothetical model to the empirical variance–covariance matrix was evaluated with three goodness-of-fit indices. Fit was assessed with the comparative fit index (CFI), the maximum likelihood χ 2, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI values of 0.95 or greater are desirable. The RMSEA is a measure of lack of fit per degrees of freedom, controlling for sample size, and values less than 0.06 indicate a close-fitting model.

The hypothesized models were tested initially with no direct pathways from the stage 1 (problem recognition-related) variables of perceived infection risk, AIDS knowledge, peer norms, and partner preference for condoms to the intention outcomes (partner preference for condoms was not relevant to the model concerned with intention to disinfect needles and was not included in that particular model). The intervening commitment facilitators relevant to the specific intention outcome (e.g., prior risky sex and self-efficacy with sexual risk reduction strategies in the case of condom use or other sexual risk reduction strategies; prior injection use and self-efficacy with needle use in the case of intention to disinfect needles) and demographics were positioned as direct predictors of the outcomes. Perceived infection risk, AIDS knowledge, peer norms, and partner preference for condoms were positioned as predictors of the intervening variables.

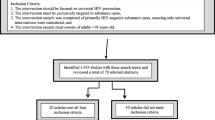

Once it was determined that direct paths from intervening variables were nonsignificant and consequently dropped from the model, further paths were added from the problem recognition variables to the outcome variables. In addition, the baseline behaviors and demographic variables were added as predictors to the intervening variables only after they were shown to be nonsignificant as direct predictors of the outcome variables. The Lagrange Multiplier test, which suggests additional relationships to add to models for fit improvement, was used to determine which additional direct paths were needed to improve the mediated models.72 Results (Figs. 2, 3, and 4) are presented for final models, showing only significant paths.

Path model showing significant paths predicting intent to use other sexual risk reduction strategies. Single-headed arrows represent regression coefficients. For readability, correlations among the predictors are not shown. Regression coefficients are standardized. a p < 0.05, b p < 0.01, c p < 0.001

Results

Sample description

Demographics

Table 1 reports the characteristics of the sample. Note that most results in Table 1 are not repeated in the text, but some are summarized or explored in more detail. The analysis sample (n = 163) was diverse in terms of gender and ethnicity, with identical gender distribution to that of MA treatment admissions in California and slightly higher minority representation (53% in the sample vs 45% statewide) than the total California group.26 The sample also has similar minority representation to the SACPA treatment population (which was 55% minority) but fewer men than SACPA (which was 73% male).18

Substance use

All study participants were substance users who identified MA as their primary drug; most (82%) had used MA within the preceding 6 months. Most had also used marijuana (91%) and alcohol (95%), but these substances were not included for consideration in the path model because of lack of variability.

Selected HIV risk behaviors

Twenty-three percent of the sample reported no sexual encounters during the 6 months preceding the interview; 58% reported sex only with main partners, 14% only with nonmain partners, and 5% with both main and nonmain partners (note that only 13% of the sample was legally married). Of those reporting sexual encounters, the average number of partners was 1.8 (standard deviation = 3.0); focusing only on those with any nonmain partners, the average was 4.3 (standard deviation = 5.5). There were no significant differences between men and women in the number of partners. Note that participants were not asked the total number of main partners. While a few participants may have had serially multiple main partners, most did not: 92% of those reporting sexual encounters with main partners also reported being with their main partner for 6 months or longer. Overall, a substantial majority (69%) reported not using condoms during sexual encounters in the 6 months preceding the interview. Women were more likely to report unprotected sex (78%) and use of drugs during sex (68%) than were men (61 and 51%, respectively; χ 2 = 5.89, df = 1, p = 0.015 and χ 2 = 4.96, df = 1, p = 0.026).

Forty-four percent of the sample reported a substance use history that included injection drug use, while 13% reported injection use within the 6 months preceding the interview. No differences were seen between men and women. Most of those with any prior injection use had also used heroin (33 of 36); however, 39 participants reported injection use but no previous heroin use. These two injection subgroups (prior heroin use vs no heroin use) did not differ significantly on intention to disinfect and were not distinguished in the ARRM model analysis.

Because of the sensitive nature of the question, the physical context of data collection (awaiting treatment intake in a centralized processing office), and the nonclinical nature of the current study, participants were not asked to disclose HIV status. We thus have no estimate of HIV prevalence in the sample. Over half of those admitted to substance use treatment in California report that they have not been tested for HIV or do not know test results (they are not asked to disclose HIV status).26

Constructs for ARRM

Among problem recognition constructs, while AIDS-related knowledge was relatively high (average of 3.4 on the 1–4 scale), perception of personal risk of infection was considerably lower (2.3). Other recognition-related construct scores ranged from averages of 2.8 to 3.1. Commitment facilitating constructs showed an average score of 3.0 or higher. Commitment/intention constructs varied in level from an average of 2.8 for intention to use condoms to 3.7 for intention to disinfect (or to not use needles).

Path analysis models

The final predictive path model predicting intent to use condoms is presented in Figure 2; nonsignificant paths and covariances were dropped serially until only significant ones remained. Notice in Figures 2, 3, and 4 that the stage 1 measures form the left-hand column of predictors, the stage 2 influences on commitment/intention form the upper portion of the center column, and the stage 2 outcome of intention appears on the right. Additional subject characteristics appear in the lower center column. Fit indexes are outstanding: ML χ 2 = 37.78, 34 df; CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.03. Intent to use condoms was directly predicted by self-efficacy for risk reduction, enjoyment of risk reduction strategies, greater perceived infection risk, less baseline risky sex, being male, and Hispanic ethnicity. There were also several significant indirect effects mediated through the intervening variables. These included an indirect impact of AIDS knowledge (p ≤ 0.001), peer norms (p ≤ 0.001), partner preference for condoms (p ≤ 0.05), a negative effect of perceived infection risk (p ≤ 0.001), and negative effect of non-Hispanic white ethnicity (p ≤ 0.05). Note that the direct effect of perceived infection risk was positive albeit rather small (0.13), but the negative indirect effect (regression coefficient = −0.14) was due to the negative paths to the intervening variables, which in turn positively predicted the intent to use condoms outcome intent variable.

The final predictive path model for intent to use other safe sex strategies is presented in Figure 3. Fit indexes are also outstanding: ML χ 2 = 42.25, 37 df; CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.03. Intent to use other safer sex strategies was directly predicted by self-efficacy for sexual risk reduction, more AIDS knowledge, less perceived infection risk, and being female. There were also a few significant indirect effects mediated through the intervening variable of self-efficacy for sexual risk reduction. These included AIDS knowledge (p ≤ 0.05), less perceived infection risk (p ≤ 0.05), and a negative effect of non-Hispanic white ethnicity (p ≤ 0.05).

The final path model predicting intent to disinfect is presented in Figure 4. Again, the fit indexes are outstanding: ML χ 2 = 37.85, 35 df; CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.02. Intent to disinfect was directly predicted by self-efficacy for needle risk reduction, more AIDS knowledge, less perceived infection risk, and peer norms. Baseline injection use did not directly predict intentions but was a powerful predictor of the intervening variables. There were also two significant indirect effects mediated through the intervening variable of self-efficacy for needle risk reduction. These included peer norms (p ≤ 0.01) and a powerful indirect negative effect of baseline injection use (p ≤ 0.001).

Discussion

Results provide evidence of sufficient levels of HIV-related sexual and injection risk behaviors to warrant public health concerns and use of intervention opportunities. This MA-using offender sample had high levels of lifetime injection use (44%), similar to the 47% among a more general MA-using California population in treatment before SACPA initiation.31 Likewise, results showed high levels of unprotected sex as found in other studies of MA users and use of alcohol/drugs during sexual encounters.11,12,14,31 For our sample, rates of sex with partners who inject were higher than reported by the Centers for Disease Control.9 Note that none of this sample reported sexual encounters with a person that they knew had HIV/AIDS. The fact mentioned earlier that more than half those admitted to treatment in California report not having been tested or not knowing test results could contribute to the lack of awareness. However, anecdotal reports from treatment providers in the county producing the sample suggest that there may be a “don’t ask, don’t tell” culture. This context provides another potential target for intervention development. We note also that this heterosexual sample was not asked about situational same-sex sex behaviors during any incarceration, a context in which such behaviors may not have been labeled as outside a heterosexual identification.

AIDS knowledge averaged slightly higher than found in earlier studies by Longshore et al.,15–17 which applied the ARRM to substance users, yet the perceived risk of HIV infection was considerably lower in the current study. The higher HIV/AIDS knowledge levels in the current study may indicate a higher generally pervasive level of awareness of HIV/AIDS issues than at earlier times or may indicate greater knowledge specifically among those who use MA than the primarily heroin samples in the aforementioned earlier studies. The results also show a substantial disconnect in this MA-using sample in linking cognitive knowledge to personal behaviors and/or understanding personal consequences of behaviors. Intentions to reduce risk behaviors are similar to those found in the earlier studies. Scores on all constructs indicate considerable “room for improvement” to be targeted through improved interventions.

Results indicated that the general ARRM structure predicting intention to reduce HIV-related sexual and injection risk behaviors appears to apply to MA-using offenders as well as to users of other substances and thus may be useful as a theoretical basis contributing to intervention development. While the estimated structure differed somewhat across the three intent constructs (for condom use, use of other safer sex strategies, and to disinfect needles), there were strong similarities in the effects of AIDS knowledge, peer norms, and self-efficacy for risk reduction strategies.

There was a consistent direct effect of perceived self-efficacy with risk reduction strategies on intention to reduce HIV risk behaviors, strongest for intent to disinfect, moderately strong for intent to use condoms, and least powerful for intent for other safer sex strategies. The weakness for the last intent indicator may be that most of the items in the self-efficacy with sexual risk reduction strategies relate to condom use. Results are consistent with other research also showing situational self-efficacy to be a predictor of intention to use condoms among heterosexual crack smokers or among juvenile offenders.64,73 These results identify self-efficacy as a possible leverage point for intervention that include focus on building clients’ skills and confidence related to specific risk reduction strategies, as well as directly raising their conscious commitment to risk reduction. Additional support for this view comes from Mausbach et al.,68 who have developed an intervention that has increased self-efficacy for condom use among MA-using MSM, which subsequently increased actual condom use behavior.

AIDS knowledge was also consistently related to intent to reduce HIV risk behavior, working either directly on intention and/or indirectly through self-efficacy. This, coupled with the less than complete knowledge of HIV/AIDS information in this sample, supports the continuing need for inclusion of risk transmission information in interventions.

As would be expected, partner preference for condom use also played a significant role in intent to use condoms or other safe sex strategies. Partner preference was related indirectly through self-efficacy in much the same way as are peer norms. Strategies to assist MA-using offenders in increasing their influence in sexual encounters may be appropriate. In addition, enjoyment of risk reduction strategies had a direct effect on intent to use condoms, emphasizing the importance of including positive imagery, and other MA users’ endorsement of enjoyable strategies, in intervention protocols. Note, however, that there could be a reciprocal relationship between enjoyment of risk reduction strategies and self-efficacy (which was not explored in the current analysis), such that improving self-efficacy related to condom use might also increase the related enjoyment of these strategies. That is, the accomplishment of having more confidence and a feeling of more control may be part of the experience of enjoying safe sex strategies.

Perceived risk of HIV infection had inconsistent direct effects on intentions to reduce risk behaviors. The effect was positive for intent to use condoms (greater perceived risk related to greater intent to use condoms). Yet, the effect was negative for the other two intention variables. These results suggest the possibility that MA users who have already engaged in behavior perceived to put themselves at risk for HIV (through injection use or sexual practices) yet have not contracted HIV may underestimate their risks and undervalue strategies to change risk behaviors.16,74 Interestingly and counter to expected ARRM relationships, perceived infection risk was negatively related to self-efficacy for sex risk reduction and enjoyment of sex risk reduction strategies; thus, those who perceived themselves as more at risk also reported less self-efficacy and less enjoyment of sex risk reduction strategies. This may identify a possible leverage point for intervention to facilitate the translation of the perception of risk into behaviors and strategies that in turn enhance perceived self-efficacy or enjoyment.

In contrast to the theoretical expectations from the ARRM, analysis results showed that response efficacy was not a significant direct predictor of any of the three intention indicators. This was also found to be the case in earlier studies by Longshore et al.16

Gender differences were observed, with men having greater intention to use condoms and women to use other safer sex strategies. These gender differences may be related to women’s lack of negotiation ability to initiate or control condom use.75,76 Results suggest that intervention approaches may need to include some gender-specific content.77–79 Ethnic effects appeared only for sex risk reduction intent. Hispanics were less likely than other races to report intention to use condoms; no other direct effects of ethnicity on intentions were observed. However, indirect effects were observed through self-efficacy for both condom and other sexual risk reduction intention. Non-Hispanic whites had lower self-efficacy scores (than other races) in both sex risk-related intention models. These effects suggest that ethnicity-specific intervention components may require special focus on self-efficacy for non-Hispanic whites and on directly changing intentions for Hispanics.

Baseline sex risk behavior directly and negatively impacted intent to use condoms. Prior sexual practices thus may be a substantial barrier to influencing change in intentions that may not be overcome by targeting other commitment facilitators. This also suggests that attention should also be paid to sex risk reduction strategies early in the risk development trajectory/history. Intervention studies also need to investigate the effectiveness of increasing self-efficacy for risk reduction specifically within subgroups of MA users with high baseline sexual risk vs those with lower baseline sexual risk to determine whether such strategies work at all for initially high-risk MA users and if so, at what level they work relative to lower-risk MA users. For intent to disinfect, baseline injection risk was negatively related to self-efficacy but not directly to intent to disinfect.

In comparing results for users of MA to results from previous studies for users of other drugs, we observed both similarities and some differences. Relationships for intent to use condoms were similar to those found for users of other drugs,15 in terms of the direct effect of self-efficacy and indirect effect of AIDS knowledge through self-efficacy. For safer sex commitment, results for the MA-using sample showed direct effects of self-efficacy as did earlier analyses with female users of other drugs.17 In addition, there was a similar effect of AIDS knowledge on the intermediate variable of self-efficacy. However, further comparison for this intention indicator was difficult because earlier work estimated different models for men and women. The current sample was not large enough to support estimation of separate models.

For intent to disinfect, results with the MA-using sample showed an identical path coefficient from perceived self-efficacy to that shown in Longshore et al.16 In addition, there was a similar influence of AIDS knowledge on response efficacy and no effect of response efficacy on intention. However, for the MA-using sample, there was also a direct effect of AIDS knowledge on intent rather than an indirect effect through self-efficacy. For the MA sample, there were no gender differences as shown in earlier analyses of users of other drugs. These results suggest that some components of HIV risk reduction interventions, in particular those relating to AIDS knowledge and self-efficacy for risk reduction strategies, may be applicable for substance users including those who use MA. Yet, physiological and psychological effects of MA on both cognitive functioning and sexual behaviors warrant additional attention in terms of optimizing intervention content and timing for MA users.34,42,80 Future attention should also be addressed to ARRM relationships and implications within specific risk subgroups, e.g., by the injection use subgroup (past heroin users/injectors vs other injectors).

Limitations

The results of these analyses must be considered within the constraints of the study. Because random sampling was not used, the results are specific to the included sample. However, because the analysis sample is typical of the general SACPA population,18 the lack of random sampling should not greatly limit interpretation. Because the study was not longitudinal in design, causality cannot be definitively determined. However, interpretation of magnitude and direction of relationships within and between stage 1 and 2 domains of recognition and commitment can proceed as with other applications of the ARRM. The complexity of the models was constrained somewhat by the relatively small sample size, but it should be noted that major constructs found relevant for problem recognition and commitment/intention stages in previous ARRM applications were included in the current models.14–17 Further analysis should include a larger sample allowing additional model complexity and analysis of specific subgroups of MA users. In addition, further follow-up research should measure actual behavior change to expand the model’s application to MA users to include the Enactment (stage 3) portion of the model.

Implications for Behavioral Health

The results from ARRM-based models do support potentially relevant foci for the development of HIV risk interventions and their application during treatment for MA abuse, which together with other evidence-based approaches may guide intervention specialization for heterosexual MA-using offenders.34,51,52 Remember, however, that our application has considered only stages 1 and 2 of the ARRM, and the potential impact of interventions derived from these results relies on an assumption that intentions (and their facilitators such as self-efficacy) are related to actual behavior change as has been supported by several studies59–64 but not as yet among heterosexual MA users. The significance of peer norms in directly or indirectly predicting intentions to change HIV risk behaviors in this population emphasizes the need for strategies to help build facilitating support structures to establish new or modified social networks and for the potential impact of wider social interventions designed to change general attitudes/norms for risk reduction. Such general “culture” change did have a dampening effect of HIV spread among the gay male population earlier in the HIV/AIDS epidemic; however, changing peer norms may pose a significant challenge among MA-using offenders because of lower HIV rates than among MSM. The relevance of AIDS knowledge and perceived infection risk confirms the appropriateness of providing information on HIV transmission and risk factors, typically included in all HIV risk reduction interventions. However, the potential impact of MA use on cognitive performance should be considered when developing the intensity, frequency, and timing of such interventions.80,81 Repetition of information, as well as discussion and practice of risk reduction strategies, may be needed several times across the recovery trajectory (not just a short, one-time dose). The strong direct effect of self-efficacy and its role as an intermediary between problem recognition-related constructs and intention to change risk behaviors underscores the importance of building into risk reduction interventions components designed to increase self-efficacy with respect to specific risk reduction behaviors. Strategies might include exercises to promote the cognitive “accessibility” of risk reduction skills,82 intentions and goal-setting exercises,83 and behavioral skills involving, e.g., condom use and negotiation skills.68,79

The adaptation of HIV risk reduction intervention strategies to the MA offender population has the potential to affect a large number of drug treatment clients and potentially reduce HIV, hepatitis, and sexually transmitted disease transmission for this population. Further research should also examine the impact of risk taking and impulsivity on intent to reduce HIV risk behaviors and possible differences in leverage points to facilitate specialization of interventions as appropriate for different client characteristics.

References

Centers for Disease Control. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2005. 17th edn. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2007 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports (Accessed 12/3/07).

Maruschak L. HIV in Prisons, 2005. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2007 Available at http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/abstract/hivp05.htm (Accessed 12/3/07).

Garofalo R, Mustanski BS, McKirnan DJ, et al. Methamphetamine and young men who have sex with men: understanding patterns and correlates of use and the association with HIV-related sexual risk. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(6):591–596.

Lorvick J, Martinez A, Gee L. Sexual and injection risk among women who inject methamphetamine in San Francisco. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83:497–505.

Shoptaw S, Reback C. Associations between methamphetamine use and HIV among men who have sex with men: a model for guiding public policy. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1151–1157.

Farabee D, Prendergast M, Cartier J. Methamphetamine use and HIV risk among substance-abusing offenders in California. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34(3):295–300.

Kantor E. HIV transmission and prevention in prisons. HIV InSite Knowledge Base Chapter. San Francisco: University of California San Francisco HIV InSiteAvailable at http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page = kb-07–04–13. (Accessed 12/8/07).

Krebs C. High-risk transmission behavior in prison and the prison subculture. The Prison Journal. 2002;82(1):19–49.

Centers for Disease Control. Methamphetamine use and HIV risk behaviors among heterosexual men—preliminary results from five northern California counties, December 2001–November 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55:273–277.

Molitor F, Truax S, Ruiz JD, et al. Association of methamphetamine use during sex with risky sexual behaviors and HIV infection among non-injection drug users. Western Journal of Medicine. 1998;168:93–97.

Reback CJ, Kamien J, Amass L. Characteristics and HIV risk behaviors of homeless, substance-using men who have sex with men. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:647–654.

Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. The context of sexual risk behavior among heterosexual methamphetamine users. Addictive Behavior. 2004;29:807–810.

Catania J, Kegeles S, Coates T. Towards an understanding of risk behavior: an AIDS Risk Reduction Model (ARRM). Health Education and Behavior. 1990;17:53–71.

Conner BT, Stein JA, Longshore D. Are cognitive AIDS risk-reduction models equally applicable among high- and low-risk seekers? Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38:379–393.

Longshore D, Stein JA, Kowalewski M, et al. Psychosocial antecedents of unprotected sex by drug-using men and women. AIDS and Behavior. 1998;2:293–306.

Longshore D, Stein JA, Conner B. Psychosocial antecedents of injection of risk reduction: a multivariate analysis. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:353–366.

Longshore D, Stein JA, Chin D. Pathways to sexual risk reduction: gender differences and strategies for intervention. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:93–104.

Urada D, Longshore D, Evans E, et al. Evaluation of the California Substance Abuse and Crime Prevention Act: Final Report. Los Angeles: UCLA Integrated Substance Programs; 2007.

California Department of Public Health, Office of AIDS HIV/AIDS Case Registry Section. HIV/AIDS cases in California, data as of October 31, 2007. Sacramento, CA: CA Dept. of Public Health, Office of AIDS; 2007 Available at http://www.cdph.ca.gov/data/statistics (Accessed 12/8/07).

Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Theoretical approaches to individual-level change in HIV risk behavior. In: Peterson JL, DeClemente RJ, eds. Handbook of HIV Prevention. New York: Kluwer; 2000:3–55.

NACO (National Association of Counties). The Meth Epidemic: The Changing Demographics of Methamphetamine. Washington, DC: National Association of Counties, Research Division; 2007.

Metzger DS, Navaline H. Human immunodeficiency virus prevention and the potential of drug abuse treatment. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;37(Supplement):S451–S456.

Anglin MD, Urada D, Brecht M.-L, et al. Criminal justice treatment admissions for methamphetamine use in California: a focus on Proposition 36. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;4(SARC Suppl):367–382.

Brecht M-L, Greenwell L, Anglin MD. Methamphetamine treatment: trends and predictors of retention and completion in a large state treatment system (1992–2002). Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29:295–306.

Rutkowski B. California Substance Abuse Research Consortium, September 2005: update on recent methamphetamine trends in four California regions. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2006;3(SARC Suppl):369–375.

California Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs (CA ADP). Treatment admissions, California Outcomes Measurement System. Sacramento: CA ADP; 2007 Available at http://www.adp.ca.gov/oara/pdf/AOD%20Use_1-1-06%20to%2012-31-06.pdf (Accessed 11/7/07).

Corby NH, Wolitski RJ. Condom use with main and other sex partners among high-risk women: intervention outcomes and correlates of reduced risk. Drugs and Society (New York). 1996;9:75–96.

Gonzales R, Marinelli-Casey P, Shoptaw S, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection among methamphetamine-dependent individuals in outpatient treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:195–202.

Halkitis P, Parsons J, Stirratt M. A double epidemic: crystal methamphetamine drug use in relation to HIV transmission among gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2001;41:17–35.

Shoptaw S, Peck JA, Reback CJ, et al. Psychiatric and substance dependence comorbidities, sexually transmitted diseases, and risk behaviors among methamphetamine-dependent gay and bisexual men seeking outpatient drug abuse treatment. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(Suppl 1):161–168.

Brecht M-L, O’Brien A, von Mayhauser C, et al. Methamphetamine use behaviors and gender differences. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:89–106.

Hser Y-I, Evans E, Huang Y-C. Treatment outcomes among women and men methamphetamine abusers in California. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:77–85.

Larkins S, Reback CJ, Shoptaw S. The methamphetamine–sex connection among gay males: a review of the literature. Connections (AIDS Project LA). 2005;Summer:2–5.

Shoptaw S, Reback CJ. Methamphetamine use and infectious disease-related behaviors in men who have sex with men: implications for interventions. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 1):130–135.

Volkow N, Wang G-J, Fowler J, et al. Stimulant-induced enhanced sexual desire as a potential contributing factor in HIV transmission. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:157–160.

Reback CJ, Larkins S, Shoptaw S. Changes in the meaning of sexual risk behaviors among gay and bisexual male methamphetamine abusers before and after drug treatment. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8:87–98.

Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. A comparison of injection and non-injection methamphetamine-using HIV positive men who have sex with men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76:203–212.

Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. Determinants of condom use stage of change among heterosexually-identified methamphetamine users. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8:391–400.

Molitor F, Ruiz JD, Flynn N, et al. Methamphetamine use and sexual and injection risk behaviors among out-of-treatment injection drug users. American Journal of Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25:475–493.

Espinoza L, Hall HI, Hardnett F, et al. Characteristics of persons with heterosexually acquired HIV infection, United States 1999–2004. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1–6.

Belenko S, Langley S, Crimmins S, et al. HIV risk behaviors, knowledge, and prevention education among offenders under community supervision: a hidden risk group. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16:367–385.

Hoffman S, Exner TM, Leu C, et al. Female-condom use in a gender-specific family planning clinic trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1897–1903.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman; 1997.

Cox J, Prithwish D, Morissette C, et al. Low perceived benefits and self-efficacy are associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection-related risk among injection drug users. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66:211–220.

Boyer CB, Barrett DC, Peterman TA, et al. Sexually transmitted disease (STD) and HIV risk in heterosexual adults attending a public STD clinic: evaluation of a randomized controlled behavioral risk-reduction intervention trial. AIDS. 1997;11(3):359–367.

Dworkin S, Exner T, Melendez R, et al. Revisiting “success”: posttrial analysis of a gender-specific HIV/STD prevention intervention. AIDS Education and Behavior. 2006;10:41–51.

Kline A, VanLandingham M. HIV-infected women and sexual risk reduction: the relevance of existing models of behavior change. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1994;6(5):390–402.

Malow R, West J, Corrigan S, et al. Outcome of psychoeducation for HIV risk reduction. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1994;6(2):113–125.

Peterson J, Coates T, Catania J, et al. Evaluation of an HIV risk reduction intervention among African-American homosexual and bisexual men. AIDS. 1996;10:319–325.

Stall R, Paul J, Barrett P, et al. An outcome evaluation to measure changes in sexual risk-taking among gay men undergoing substance use disorder treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:837–845.

Lyles C, Kay L, Crepaz N, et al. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:133–143.

Herbst J, Beeker C, Mathew A, et al. The effectiveness of individual-, group-, and community-level HIV behavioral risk-reduction interventions for adult men who have sex with men. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(4S):S38–S67.

Hosak L, Preiss M, Malif M, et al. Temperament and character inventory (TCI) personality profile in methamphetamine abusers: a controlled study. European Psychiatry. 2004;19:193–195.

Patterson T, Semple S, Zians J, et al. Methamphetamine-using HIV-positive men who have sex with men: correlates of polydrug use. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82(Suppl 1):i120–i126.

Semple SJ, Zians J, Grant I, et al. Methamphetamine use, impulsivity, and sexual risk behavior among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2006;25:105–114.

Catania J, Coates T, Kegeles S. A test of the AIDS Risk Reduction Model: psychosocial correlates of condom use in the AMEN Cohort Survey. Health Psychology. 1994;13(6):548–555.

Hoffman S, Exner T, Leu C-S, et al. Female-condom use in a gender-specific family planning clinic trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(11):1897–1903.

Malow R, Ireland S. HIV risk correlates among non-injection cocaine dependent men in treatment. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1996;8(3):226–235.

Anderson E, Wagstaff W, Heckman T, et al. Information–Motivation–Behavioral skills (IMB) Model: testing direct and mediated treatment effects on condom use among women in low-income housing. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;31(1):70–79.

Bowen A. Predicting increased condom use with main partners: potential approaches to intervention. Drugs in Society. 1996;9(102):57–74.

Sanderson C, Yopyk D. Improving condom use intentions and behavior by changing perceived partner norms: an evaluation of condom promotion videos for college students. Health Psychology. 2007;26(4):481–487.

Heeren G, Jemmott J, Mandeya A, et al. Theory-based predictors of condom use among university students in the United States and South Africa. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2007;19(1):1–12.

Naar-King S, Wright K, Parsons J, et al. Health choices: motivational enhancement therapy for health risk behaviors in HIV-positive youth. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2006;18(1):1–11.

Robertson A, Stein J, Baird-Thomas C. Gender differences in the prediction of condom use among incarcerated juvenile offenders: testing the information–motivation–behavior skills (IMB) model. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:18–25.

Des Jarlais DC, Guydish J, Friedman SR, et al. HIV/AIDS Prevention for Drug Users in Natural Settings. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 2000.

Semaan S, Des Jarlais DC, Sogolow E, et al. A meta-analysis of the effect of HIV prevention interventions on the sex behaviors of drug users in the United States. Journal of AIDS. 2002;30:S73–S93.

van Empelen P, Kok G, van Kesteren NM, et al. Effective methods to change sex-risk among drug users: a review of psychosocial interventions. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:1593–1608.

Mausbach B, Semple SJ, Strathdee S, et al. Efficacy of a behavioral intervention for increasing safer sex behaviors in HIV-positive MSM methamphetamine users: results from the EDGE study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87:249–257.

Joe G, Simpson D. HIV risks, gender, and cocaine use among opiate users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;37:23–28.

Longshore D, Hsieh S, Anglin MD. AIDS knowledge and attitudes among injection drug users: the issue of reliability. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1992;4:29–40.

Bentler PM. EQS 6 Structural Equations Program Manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software; 2006.

Chou C-P, Bentler PM. Model modification in covariance structure modeling: a comparison among likelihood ratio, Lagrange Multiplier, and Wald tests. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:115–136.

Bowen A, Williams M, Dearing E, et al. Male heterosexual crack smokers with multiple sex partners: between- and within-person predictors of condom use intention. Health Education Research. 2006;21:549–559.

Perloff R. Persuading People to have Safer Sex: Application of Social Science to the Crisis. Mahweh, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001.

Amaro H. Love, sex, and power: considering women’s realities in HIV prevention. American Psychologist. 1995;50:437–447.

Pulerwitz J, Amaro H, De Jong W, et al. Relationship power, condom use and HIV risk among women in the USA. AIDS Care. 2002;14:789–800.

Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. Female methamphetamine users: social characteristics and sexual risk behavior. Women and Health. 2004;40:35–49.

Sterk C, Theall K, Elifson K. Effectiveness of a risk reduction intervention among African American women who use crack cocaine. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15:15–32.

Wechsberg W, Lam W, Zule W, et al. Efficacy of a woman-focused intervention to reduce HIV risk and increase self-sufficiency among African American crack abusers. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1165–1173.

Hoffman W, Moore M, Templin R, et al. Neuropsychological function and delay discounting in methamphetamine-dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology. 2006;188:162–170.

Kalechstein A, Newton T, Green M. Methamphetamine dependence is associated with neurocognitive impairment in the initial phases of abstinence. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2003;15:215–220.

Norris A, Ford K. Condom use by low-income African American and Hispanic youth with a well-known partner: integrating the health belief model, theory of reasoned action, and the construct accessibility model. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1995;25:1801–1830.

Strecher V, Seijts G, Kok G, et al. Goal setting as a strategy for health behavior change. Health Education Quarterly. 1995;22:190–200.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the University-wide AIDS Research Program UARP no. ID05-LA-011. Analysis was assisted by funding from NIDA P01-DA 01070-33. The authors thank Lily Alvarez and Etta Robin from Kern County Behavioral System of Care for assistance with subject recruitment and data collection, Umma Warda and Gisele Pham for assistance with the analysis and manuscript, and Douglas Anglin for reviewing the manuscript. Douglas Longshore provided the design and basis for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brecht, ML., Stein, J., Evans, E. et al. Predictors of Intention to Change HIV Sexual and Injection Risk Behaviors among Heterosexual Methamphetamine-Using Offenders in Drug Treatment: A Test of the AIDS Risk Reduction Model. J Behav Health Serv Res 36, 247–266 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-007-9106-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-007-9106-y