Abstract

Scholars conceptualize entrepreneurial behavior (EB) as the actions taken for new venture creation, which are said to manifest from an individual’s intention to become an entrepreneur (EI). Though theoretically supported, predicting EB through EI faces many operationalization challenges, is rarely empirically reported, and presents methodological inconsistencies. Addressing these issues will improve our ability to identify emerging and successful new business venturers and facilitate further entrepreneurial stimulation of populations. Using both a cross-sectional and a 5-year longitudinal research design, we study the applicability of social cognitive career theory (SCCT) in explaining EI and EB for a sample of 1,149 Portuguese college students. The cross-sectional results support SCCT’s ability to explain students’ intentions in this large student population. Furthermore, with a smaller subsample, longitudinal analysis confirms intentions, as predictive of nascent EB, towards successful new business creation. In contrast to the theory’s propositions, we find that entrepreneurial self-efficacy beliefs and outcome expectations do not add to EI’s ability to predict EB. This study contributes to the currently scarce empirical support for SCCT as an appropriate model explaining EI and is the first to apply this theory’s core model to test the EI-EB link longitudinally. This study may be relevant to educators and policymakers who want to promote and assist college students in creating their own new businesses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship has been internationally viewed as a panacea for firm performance, technological innovation and economic development (e.g., Ireland and Webb 2007; Audretsch et al. 2015; Coad et al. 2016). As a result, many researchers, policymakers and educators are interested in explaining and predicting entrepreneurial behavior (EB). Intentions are proposed to mediate the long-researched relationship between attitude and behavior (Bagozzi et al. 1989), capturing the motivational factors that influence respective behaviors (Ajzen 1991; Gollwitzer 1993), and in the entrepreneurship setting, which can provide a cognitive perspective on the entrepreneurial process (Krueger et al. 2000; Liñán and Fayolle 2015; Esfandiar et al. 2019).

However, the specificities of the entrepreneurial context may be problematic for the empirical validation of the entrepreneurial intentions (EI)-EB link given that goals are frequently not clearly stated, are not set proximally to the intended behavior, and refer to actions that are not subject to personal control (Bird and Jelinek 1989; Krueger et al. 2000; Hills and Singh 2004; Lent and Brown 2006; Krueger 2009; Bird 2015; Liñán and Fayolle 2015). The possibility that EI levels change over time is real and based on accessing new information or encountering unforeseen obstacles to action among other reasons (e.g., Sheeran et al. 1999; Liñán and Rodríguez-Cohard 2008). Consequently, calls have been made for further empirical validation of the EI-EB relationship (Kautonen et al. 2015; Adam and Fayolle 2016; Liguori et al. 2018; Bogatyreva et al. 2019; Gieure et al. 2020), particularly in a longitudinal sense.

Drawing on social cognitive career theory (SCCT: Lent et al. 1994, 2000), we first test the theory’s ability to explain college students’ EI based on a sample of 1,149 Portuguese students. Although SCCT has already been proposed to explain EI and to be robust when compared to other more popular intention models (e.g., Segal et al. 2002; Liguori 2012; Liguori et al. 2018), required empirical support is still lacking.

Finally, drawing on SCCT, we analyze the explanatory power of an EB model based on EI and its direct cognitive antecedents as reported 5 years earlier by a subsample of 242 students. Furthermore, we test the theory’s capacity to predict nascent EB (i.e., trying to set up a new business) and actual new business creation (i.e., successful nascent EB). Within the context of new business creation, very few studies analyze the temporal progression of intention (Liñán and Rodríguez-Cohard 2015), and future research on this subject has already been called for by many (e.g., Heuer et al. 2009; Liñán and Fayolle 2015; Walter and Heinrichs 2015). While the number of longitudinal studies in the broader SCCT literature grows (Lent and Brown 2019), to date, there are no known longitudinal validations of the core SCCT model in entrepreneurship research. Our longitudinal study is deemed relevant since EI is proposed to be the optimal predictor of EB (Krueger et al. 2000), but the degree of confidence that one can ascribe to previously stated intentions leading to nascent EB and to new businesses actually being created is still to be clarified.

By studying the cognitive processes behind college students EI and EB, this research may be useful for educators and policymakers wanting to promote and support the most qualified individuals in a population to create their own new business ventures. Researchers, particularly those studying the determinants of EI and EB, may also benefit from this study’s findings and from its propositions related to the use of SCCT in entrepreneurship.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. A brief literature review presents theoretical support for the EI-EB relationship and provides an overview of SCCT as this study’s overarching theoretical framework. The hypotheses are then developed, noting a number of relevant methodological and temporal considerations. The methodological section details our data collection, testing and process of analysis before both the cross-section and longitudinal studies’ results are provided. A discussion elaborates on the results and interprets their novelty in the context of this study and the wider field. Finally, a conclusion addresses the implications of the findings for theory and practice and suggests directions for future research.

Literature review

Entrepreneurial behavior (EB) relates to the personal actions taken in the pursuit of new venture creation (Gartner 1988; Gartner et al. 2010), which include both pre-venture creation activities and those directly linked to new venture progression and scaling. Stemming from a lack of consensus in the quest for the entrepreneur’s distinctive personality traits (e.g., Gartner 1988; Wennekers and Thurik 1999; Mitchell et al. 2002; McKenzie et al. 2007; Shaver 2010), studying the decision to act and the active processes of the entrepreneur is pertinent to entrepreneurship scholarship. Examples of entrepreneurial activities include writing a business plan, putting together a start-up team, resource gathering and product/service development (McGee et al. 2009).

Sommer (2011) states that behavior is governed either by intentions or by automatic processes. Entrepreneurial intentions (EI) have been conceptualized as a state of mind directing a person’s attention, experience and actions towards the specific goal of creating a new business venture (Bird and Jelinek 1989). This transfer from intention to activation in the entrepreneur forms the focal point of this paper. Krueger et al. (2000, p. 411) suggest that “intentions have proven the best predictor of planned behavior, particularly when that behavior is rare, hard to observe, or involves unpredictable time lags” and considers the study of entrepreneurship to be a fitting context for intention-based inquiry. As a result, scholarly work on EI is prolific, as highlighted by the number of meta-analytic reviews on the topic alone (Zhao et al. 2010; Bae et al. 2014; Schlaegel and Koenig 2014). However, despite its popularity, the relationship between EI and EB is still debated and “still has a lot to reveal, leaving a gap in the literature” (Adam and Fayolle 2016, p. 81). Researchers have found varying strengths of this EI-to-EB relationship, which casts some doubt (Schlaegel and Koenig 2014). EI explained variance has greatly varied, ranging between 10% and 37% (e.g., Armitage and Conner 2001; Liñán and Fayolle 2015; Van Gelderen et al. 2015; Shirokova et al. 2016; Delanoë-Gueguen and Liñán 2019; Neneh 2019). Numerous EI-focused studies suffer from methodological idiosyncrasies (e.g., varying study timeframes, different measurement instruments, etc.), which may justify some of their results’ differences (Kolvereid and Isaksen 2006; Hulsink and Rauch 2010; Kautonen et al. 2013, 2015; Schlaegel and Koenig 2014). However, Lent and Brown (2006) raise some concerns about this predictability in contexts where goals are not clearly stated, are not set proximally to the intended behavior, and refer to actions that are not subject to personal control. Additionally, the specific measurement of EI is still not consensual and has been criticized for being inconsistent and ambiguous at times (Bird 2015).

In addition to the discussion on empirical considerations of the EI-to-EB relationship, researchers debate the critical and theoretical underpinnings of this process in deciphering how to detect EI itself and indeed when it emerges in these individuals. Zapkau et al. (2017), similar to others before them (e.g., Bird and Jelinek 1989; Hui-Chen et al. 2014), suggest that intentionality could initiate the entrepreneurial process. Other scholars argue that intentions develop long before a new venture opportunity is even identified (Shook et al. 2003) and that the entrepreneurial process is ‘triggered’ when the individual begins to commit thought and time to its pursuit, i.e., when he or she takes action (Degeorge and Fayolle 2011).

Due to the noted gaps in the EI-EB literature, our study aims to reexamine the cognitive antecedents of EI and the robustness of this relationship over time adopting the more recent theoretical perspective of social cognitive career theory (SCCT).

Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT)

Intentionality studies are often modeled using the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB: Ajzen 1991, 2012) or Shapero's model of the ‘Entrepreneurial Event’ (SEE: Shapero and Sokol 1982). While these provide significant value to our understanding of the entrepreneur, they are considered to be quite linear in nature, which is suggested to limit their ability to account for reciprocal, exponential, and/or moderating relationships (Liguori et al. 2018). Emanating from the career literature, SCCT (Lent et al. 1994, 2000, 2002) is regarded as a promising theoretical basis for EI models given its robustness across domains and contexts (Liguori et al. 2018). As a result, it is growing in popularity in the study of EI and has already been used by several scholars to date (Zhao et al. 2005; Lent et al. 2010; Vázquez et al. 2010; Liguori 2012; Chen 2013; Lanero et al. 2015, 2016; Austin and Nauta 2016; Pfeifer et al. 2016).

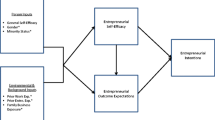

SCCT, drawing from self-efficacy theory and social cognitive theory, was proposed to direct research inquiry on individuals’ career-related decision processes (Lent and Brown 2006). It covers interrelated topics such as academic/career interest development, career choice, performance and satisfaction (Lent and Brown 2006); thus, its application to entrepreneurship appears unproblematic. This model posits that choice actions (the effort to transform goals into concrete behaviors) are predicted by goals/intentions as well as interests (Lent and Brown 2019). SCCT motivational theory relies on three main variables: self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and goal-directed activity. These constitute the core elements of the model (see Fig. 1) and represent the means through which individuals influence personal agency (Lent et al. 2002; Liguori et al. 2018).

The SCCT model adapted from Lent et al. (2017, p. 108) highlighting the core cognitive elements of the model

Self-beliefs are key to this new perspective, and self-efficacy beliefs specifically, as judgments about one’s capabilities (Bandura 1986), act as a mechanism of human agency for self-development, adaption, and change (cf. Bandura 1977, 1982, 1986). SCCT proposes that career-specific self-efficacy beliefs and outcome expectations are key cognitive antecedents of career interest, intentions/goals and actions (Lent et al. 1994) (see Fig. 1). In the entrepreneurship research domain, self-efficacy has been mostly conceptualized as entrepreneurial self-efficacy beliefs, but generalized self-efficacy measures have also been used. Outcome expectations (OE) denote individuals’ beliefs about the consequences of performing particular behaviors (Lent and Brown 2006) and “the extent to which they will be able to satisfy their primary values if they were to pursue particular career paths” (Lent 2005, p. 104).

SCCT acknowledges the effects of personal inputs and contextual and environmental factors on personal choices, creating a robust framework for studying an interplay of conditions (Lent et al. 1994; Liguori et al. 2018); however, it purposefully focuses on more dynamic and contextual personal attributes to explain certain career outcomes (Lent et al. 1994).

The first main aim of this paper is to validate the SCCT model within the context of this study by examining the effect of a parsimonious version of an SCCT model on a sample of Portuguese students. Testing the core SCCT model (Lent et al. 1994) requires one to test, at least, the following relationships: (1) the effects on career intentions from its main direct cognitive antecedents—career self-efficacy beliefs and career outcome expectations—and (2) the effect of specific self-efficacy beliefs as an antecedent of career outcome expectations.

Previously, SCCT has been suggested to be theoretically robust in predicting intentions for new venture creation, even when compared to the Theory of Planned Behavior (Liguori 2012; Lucas and Cooper 2012; Liguori et al. 2018). One of the first examples can be found in Segal et al. (2002), who tested a structural model to predict the self-employment goals/intentions of 115 American business students. The study notes strong effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy beliefs and outcome expectations on EI and concludes that the SCCT model has much higher explanatory power than other models. Chen (2013) also noted positive significant relationships between all elements of the parsimonious model while Lanero et al. (2015) found significant relationships in all but the link from outcome expectations to EI. Based on these previous works in the entrepreneurship context (Segal et al. 2002; Chen 2013; Lanero et al. 2015, 2016) as well as other career-focused studies applying SCCT to Portuguese students (Cordeiro et al. 2015; Lent et al. 2018), we hypothesize that the model will successfully predict EI in the student cohort.

-

H1: A parsimonious model of social cognitive career theory can explain the entrepreneurial intentions of college students.

Temporal considerations of Entrepreneurial Intentions (EI) and Behavior (EB)

Given that intent may develop well before an actual intended goal or behavior is achieved (Shook et al. 2003) and that high levels of EI may be reported by individuals with a wide range of career decision-making maturities (Hirschi 2013), intentions’ stability is key to empirically verifying the EI-EB link. However, regarding new business creation, “very few efforts have yet been made to analyze the temporal progression of intention” (Liñán and Rodríguez-Cohard 2015, p. 78), and future research on this subject has been requested (Heuer et al. 2009; Liñán and Fayolle 2015; Walter and Heinrichs 2015). Consequently, the second aim of this paper is to longitudinally examine the EI-to-EB relationship underpinned by SCCT.

In addition, the successful creation of a new business in the future often has a component that lies outside the control of the individual (Sheppard et al. 1988). Due to many external factors, there can be considerable temporal distance between formulating behavioral intentions and the behavior itself (cf. Lent and Brown 2006). The smaller the temporal gap between intentions and actual behavior, the more accurate intention models are posited to be. “This is because goals, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and so forth are fluid percepts that are subject to change with increasing experience” (Lent and Brown 2006, p. 23). However, it should be noted that cognitive variables stability may improve “as skills crystallize and performance experiences mount up” (Lent and Brown 2006, p. 32). While it is acknowledged that due to a range of factors, the strength of relationships may vary within the model, we propose that SCCT is robust enough to predict EB via EI even after a significant time lag. For the purposes of our study and to cover a greater proportion of the SCCT model, EB will be studied at both the action and attainment levels (see Fig. 1). Specifically, we investigate how well entrepreneurial self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations and EI can predict nascent EB and successful new business creation.

Shaver and Scott (1991) propose the existence of a series of prior discontinuous events that will eventually result in a new business being created. These activities are considered to be precursors to new venture creation, which Carter et al. (1996) suggest signal increased EI strength and their temporal proximity to and probability of new business creation (e.g., preparing a plan, developing models, saving money to invest, organizing a start-up team and looking for facilities). However, there is disagreement among scholars on the gestation period and normal sequence of such nascent entrepreneurial activities,Footnote 1 as difficulty lies in pinpointing the exact process initiator or marker (Davidsson and Gordon 2011, p. 861). Due to this difficulty, some authors have compiled a list of nascent entrepreneurial behaviors, suggesting that individuals who have performed at least two activities from this list should be considered involved in the process of creating a new business (e.g., McGee et al. 2009), while others have simply asked individuals if they were actively trying to start their own business (e.g., Reynolds et al. 2004). Studying nascent EB in a longitudinal sense has particular merit, as there may be more nuanced reasons for the longer gestation period between intention and start-up. In fact, actual goal achievement may present a considerable delay from the formation of its respective intentions (Shook et al. 2003). The degree of intention formation (i.e., intention intensity: high versus low level intentions) and EI stability over time are considered the main factors shaping the validity of and interest in EI cognitive models for predicting EB (cf. Liñán and Rodríguez-Cohard 2008; Heuer et al. 2009). In fact, Sheeran et al. (1999, p. 724) noted that “intention stability moderated the intention-behavior relation such that stable intentions were more likely to be enacted than unstable intentions.” Thus, we posit that a cognitive model including entrepreneurial self-efficacy beliefs, entrepreneurial outcome expectations and EI will allow us to predict nascent EB and the successful creation of a new business over time.

-

H2: A parsimonious model of social cognitive career theory can predict the nascent entrepreneurial behaviors of college students over a five-year period.

-

H3: A parsimonious model of social cognitive career theory can predict new business creation by college students over a five-year period.

Methodology

Research design and samples

Our confirmatory methodology is based on a cross-sectional and longitudinal research design, on testing a parsimonious version of the SCCT model in the entrepreneurship context, and on a sample of Portuguese college students who participated in the EEP Portugal research project (Belchior 2019) via the SurveyMonkey (2010/2011) and LimeSurvey (2015/2016) internet survey platforms. The tested model is defined as parsimonious given that we focus on the model’s core cognitive constructs and do not include the antecedents of ESE and EOE (the ‘learning experiences’ variable), interests, and variables related to ‘personality and contextual influences that are proximal to adaptive behavior’, which are all part of the full SCCT framework (Lent et al. 2017, p. 108). With AMOS software (version 25), we used structural equation modeling to test our hypotheses regarding the determinants of entrepreneurial intentions (EI) and behavior (Nascent EB and Business Creation).

Our initial sample was comprised of 1,309 students, included in the EEP Portugal dataset for the 2010–2011 academic year. After removing all cases with missing values, for the main variables of interest (i.e., listwise deletion for items related to EI, ESE, and EOE), our final samples included 1,149 students for the cross-sectional study and 242 students (21.06%) for the 5-year longitudinal study. From Table 1 (below), the samples’ descriptive statistics show an average age of 24.12 years (SD = 6.61) where 43.5% are male, 29.6% are graduate students, 47.2% are business students, 46.8% have had prior entrepreneurial education, 30.5% have five or more years of work experience, 15.0% have prior entrepreneurial experience and 57.6% report having family members with prior business experience.

Regarding follow-up survey attrition, we find very little variation (less than 5%) between the mean values of our main variables when comparing the initial (T0) and final sample (T5) means 5 years later. However, we do find that those with prior entrepreneurial experience, those who had graduated and those with entrepreneurial education at T0 were considerably more likely to participate for the whole duration of the study (57.3%, 37.9%, and 21.8% more likely, respectively). Those enrolled in business programs were less likely to participate across the study period (12.2% less likely).

Measurement instruments

EEP Portugal constructs were measured based on the same measurement instruments used in the international Entrepreneurship Education Project (Vanevenhoven and Liguori 2013). Table 2 (below) provides a summary of all constructs’ measurement models, scale items and mean values.

To measure entrepreneurial intentions (EI), a shorter 3-item Likert scale (1 = very untrue to 7 = very true) adapted from Thompson's (2009) original scale was used. An exploratory factor analysisFootnote 2 (EFA) provides evidence of a single factor structure explaining 66.08% of the items variability and is within the acceptable thresholds of KMO (Kaiser 1974) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (Schumacker and Lomax 2004) [KMO = 0.684; Bartlett's test of sphericity of χ2 = 773,200(3), p. = 0.000].

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy beliefs (ESE) were measured as a second order latent variable with an 18-item scale as in McGee et al. (2009) (scale: [0–100]; measuring confidence in one’s ability to successfully complete each of a series of entrepreneurial activities). Although the initial exploratory factor analysis suggested a 3-factor solution with several cross-loadings, no theoretical support could be found for this; therefore, based on McGee et al.’s original study, a 5-factor solution was imposed. With this final solution, items loaded on the expected ESE dimensions and only two relevant cross-loadings were removed from the measurement model (i.e., ESE items 7 and 8, which were originally expected to load only on ESE planning). The resulting factorial solution explained 71.11% of the items’ variability with an acceptable KMO of 0.913 and Bartlett's test of sphericity result of χ2 = 11,111.366(153), p. = 0.000.

Entrepreneurial outcome expectations (EOE) were measured with a 3-item Likert-type scale (1 = nothing, to 7 = very much), designed as a shorter version than the one described in Vanevenhoven and Liguori (2013). The EFA provides evidence of a single factor structure explaining 67.77% of these items’ variability with an acceptable KMO of 0.682 and Bartlett's test of sphericity result of (χ2 = 879.694(3); p. = 0.000).

New Business Creation (also referred to as ‘Business Creation’) was measured as a dichotomic variable (Yes/No) assuming a value of 1 when students disclosed in the last survey that they had started their own new business within the 5-year period between the first and last EEP Portugal survey waves.

Nascent entrepreneurial behavior (also referred to as ‘Nascent EB’) was also measured as a dichotomic variable (Yes/No) assuming a value of 1 when students disclosed that they had already performed at least one activity from a list of 13 nascent entrepreneurial activities (cf. Appendix: based on Carter et al. 1996; McGee et al. 2009; Vanevenhoven and Liguori 2013) over the same 5-year period. By definition, those classified with ‘Business Creation’ were also classified as having engaged in ‘Nascent EB’ during this period.

Measure reliability and validity

The EI measurement, originally a modified version of Thompson's (2009) scale with six items, was shortened to improve construct discriminant and face validity (regarding nascent EB) and internal reliability. Namely, the following items were removed: “Are saving money to start a business,” “Do not read books on how to set up a firm (R)” and "I spend time learning how to create a new business project". Additionally, EOE, in its initial 4-item structure, was found to be valued slightly below the desirable level of convergent validity (AVE = 0.479). As its fourth item, “Family security (to secure future for family members, to build a business to pass on, etc.)”, was the least loaded item, we decided to remove it, leaving EOE with only 3 items and acceptable convergent validity.

Regarding the psychometric properties of the measurement scales, we analyzed both their reliability and validity considering current best practices and thresholds (Fornell and Larcker 1981; Hair et al. 2010; Kline 2011). A confirmatory factor analysis, necessary to calculate composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), maximum shared variance (MSV) and construct intercorrelation, was performed using the bootstrap (1,000 samples) with maximum likelihood estimation method. The bootstrap procedure is advantageous in that “it can be used to generate an approximate standard error for many statistics that AMOS computes, albeit without having to satisfy the assumption of multivariate normality” (Byrne 2010, p. 334). Given a normalized Mardia's (1970) coefficient of multivariate kurtosis of 284.383 and a critical value of 136.435, it was clearly observed that the data were not multivariate normal (Byrne 2010). Table 2 summarizes the constructs’ measurement model, which includes each construct’s reliability (i.e., CA: Cronbach 1951; CR: Fornell and Larcker 1981) convergent validity (i.e., factor loadings from the rotated component matrix and AVE, all > 0.5) and discriminant validity (factor crossloadings, MSV < AVE and the square root of AVE > interconstruct correlations).

In terms of scale reliability, the constructs’ CA and CR were valued at > 0.7, indicating reliable measurement. Attesting for their convergent validity, factor loadings from the rotated component matrix ranged from 0.593 to 0.871, falling above the threshold, and AVE resulted in values between 0.493 and 0.567, approximately within the acceptable threshold (as AVE is considered a strict measure of convergent validity, Malhotra and Dash 2011). Regarding discriminant validity, no relevant crossloadings were found in the final factor solution.

Common method bias test

To check for common method bias, we first applied Harman's single factor test by constraining to one the number of factors extracted in an EFA, the single factor from the unrotated solution. The single factor accounted for 32.93%, alleviating concerns about the significance of such bias. We complemented this first analysis with the ‘common latent construct with marker variable’ method, which is considered more accurate (Podsakoff et al. 2003; Williams et al. 2010), and with a more appropriate bootstrapping ML estimation. To do so, another latent factor, ‘altruistic values’ (7-item, CA = 71.5; measured as in the EEP Project; Vanevenhoven and Liguori 2013), was added to the model and was not expected to correlate with the other latent factors in the model (correlations were found to be between -0.007 and 0.130). In comparing standardized loadings regression weights, with and without the marker variable and common latent factor, we report a 0.005 change in the ESE-EI effect; a 0.011 change in the EOE-EI effect; and a 0.022 change in the ESE-EOE effect. Thus, common method bias appears not to be a relevant source of systematic bias in our study.

SEM method and goodness-of-fit test

Structural equation modeling is considered an appropriate method for testing our hypotheses because (1) it takes a confirmatory approach to data analysis, which enables hypothesis testing; (2) it provides explicit estimates of measurement error for independent variables; and (3) it enables the incorporation of both observed and unobserved variables (Schumacker and Lomax 2004; Byrne 2010). Structural equation modeling has been extensively used in entrepreneurship research (e.g., McGee et al. 2009; Guerrero and Urbano 2014; Gieure et al. 2020) and in testing SCCT (e.g., Özyürek 2005; Wang 2013; Wright et al. 2014).

A plethora of goodness-of-fit indices exist, and several are reported here for both the cross-sectional and longitudinal models. Model fit was determined based on common practices of empirical research, namely, CFI ≥ 0.90, RMSEA ≤ 0.10, and SRMR ≤ 0.10 (Weston and Gore 2006). Moreover, the cross-sectional model (based on a larger sample size) is acceptable even when applying stricter criteria such as SRMR ≤ 0.09 and RMSEA ≤ 0.06 (cf. Mueller and Hancock 2008) without any empirically driven adjustments based on AMOS modification indices.

Results

When comparing the descriptive statistics of this study (Table 1; n = 1,149) to those of the international Entrepreneurship Education Project (cf. Vanevenhoven and Liguori 2013, Table 2; n = 14,396), we found similar mean levels for entrepreneurial self-efficacy beliefs (ESE: 68.87 vs. 68.83) and slightly higher entrepreneurial outcome expectations (EOE: 5.79 vs. 5.60) and entrepreneurial intentions (EI: 4.88 vs. 4.33) for the EEP Portugal sample. In terms of SCCT EI construct correlations, the Portuguese data displayed smaller correlations between all constructs with the most significant difference found between the ESE-EOE correlations (r = 0.17 vs. r = 0.28) followed by the EOE-EI correlations (r = 0.22 vs. r = 0.28) and, finally, the ESE-EI correlations (r = 0.39 vs. r = 0.44).

In analyzing the structural model, in Fig. 2 based on SCCT propositions, the cross-sectional analysis results provide empirical support for hypothesis H1. Using a parsimonious SCCT model, we were able to significantly explain Portuguese higher education students’ EI as reported in the initial study with EOE(T0) and ESE(T0) explaining 31.3% of the construct’s variance. This result is based on the EI(T0) squared multiple correlations value and the respective confidence intervals at 95% (IQ using bootstrap ML method, two-tailed with a bias-corrected percentile: cf. Efron and Tibshirani 1986; Azen and Sass 2008).

In line with the theory, we also found positive and significant relationships between ESE(T0) and EOE(T0) with a std. effect of 0.207 (p. = 002) and EOE(T0)’s squared multiple correlations of 0.043 (p. = 002) between ESE(T0) and EI(T0) with a std. effect of 0.492(p. = 002) and between EOE(T0) and EI(T0) with a std. effect of 0.183 (p. = 002). All confidence intervals at 95% exclude the zero value, and this holds true for all std. effects and squared multiple correlations. Finally, as shown in Fig. 2, the model’s goodness-of-fit value is acceptable given that CFI = 0.927, RMSEA = 0.058, and SRMR = 0.054 (cf. Weston and Gore 2006; Mueller and Hancock 2008).

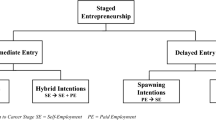

Regarding the longitudinal study, we start by reporting that of the 242 students who provided relevant information during the 5-year timeframe, 88 students (36.36%) tried to start their own businesses, and 40 students (16.53%) actually succeeded in doing so (see Table 1). However, it should be noted that percentages may be overestimated if those who did not try to create a new business were less likely to continue as participants in the EEP Portugal project. As a lower bound, if all 1,149 students (from the initial sample at T0) had reported having engaged in nascent EB and/or as new business creators, the percentages would instead be 7.66% and 3.48%, respectively.

Figure 3, while graphically preserving the cross-section component of the model (i.e., the arrows), only focuses and displays the longitudinal study results. The relationship between ESE, EOE and EI is reported above for the larger sample of 1,149 students.

Hypothesis H2 states that a parsimonious SCCT EI model can predict the nascent EB of college students for a 5-year period. As confirmed in Fig. 3, our longitudinal results provide mixed empirical support for this hypothesis. In line with SCCT propositions, we do find nascent EB(T0-T5) to be significantly predicted by a model including ESE(T0), EOE(T0) and EI(T0). Based on the squared multiple correlations value, together these cognitive constructs explain 20.8% (p = 0.006) of the variable’s variance, and we also find a strong significant EI(T0)-Nascent EB(T0-T5) relationship with a std. effect of 0.430 (p = 002). The confidence intervals at 95% for both results exclude the value zero. However, contrary to SCCT propositions, neither ESE(T0) nor EOE(T0) are found to be significantly and directly related to Nascent EB(T0-T5) with std. effects of 0.079 (p = 0.331) and -0.148 (p = 0.052), respectively.

Finally, the test of hypothesis H3 resulted in mixed empirical support in its attempt to predict active entrepreneurial behavior over a 5-year period. Namely, while 34.8% (p. = 0.003) of the Business Creation variance is explained by its determinants in the model, Nascent EB(T0-T5) and ESE(T0), contrary to what is predicted by the theory, ESE(T0) does not directly affect successful Business Creation, with an insignificant std. effect of 0.348 (p = 0.331). For the relationship between Nascent EB and Business Creation, a significant std. effect of 0.578 (p = 0.002) is found. In addition, the total indirect effect of EI on Business Creation is significant with a std. effect of 0.249 (p. = 0.002), which is computed simply by multiplying the std. effects of the relationships between EI and Nascent EB and Nascent EB and Business Creation. Notably, an alternative longitudinal model in which Nascent EB is not included was also estimated. Despite leaving the verdict on hypothesis H3 unchanged, the fact that this alternative model can only explain 6.5% (p. = 0.009) of Business Creation variance and EI std. direct effect is borderline insignificant at 0.175 (p. = 0.057) suggests the need to downplay the reported supporting evidence of EI as predictive of successful (nascent) EB.

Finally, our longitudinal results regarding ESE are not proof of the construct’s irrelevance in explaining Nascent EB and Business Creation. The total effects exist and are significant with the std. total (direct and indirect) effects of ESE on Nascent EB being 0.293 (p. = 0.002) and those on Business Creation being 0.205 (p. = 0.002). The alternative longitudinal model (without nascent EB) provides very similar results with ESE std. total effects on Business Creation of 0.208 (p. = 0.002). Thus, the insignificant direct effect only indicates that contrary to what is proposed by SCCT, EI captures/mediates ESE’s full effects on these variables. The same cannot be said for EOE effects, as the construct was found to be insignificantly related to both variables with values of -0.040 (p. = 0.594) and -0.023 (p. = 0.583), respectively.

Relative to the goodness-of-fit value, while displaying less overall fit than the cross-section model, taken together with CFI = 0.892, RMSEA = 0.067, and SRMR = 0.068, the longitudinal model still provides an acceptable fit (cf. Weston and Gore 2006; Mueller and Hancock 2008).

Discussion

The ex ante literature identifies a shortage of research on the relationship between entrepreneurial intentions (EI) and entrepreneurial behavior (EB) and calls for more longitudinal research (Churchill and Bygrave 1990; Sheu et al. 2010; Fayolle and Liñán 2014; Liguori et al. 2018; Bogatyreva et al. 2019; Gieure et al. 2020; Meoli et al. 2020). The application of SCCT to entrepreneurship research is also scarce, despite the theory being an established theoretical framework in the career choice literature (Segal et al. 2002; Liguori et al. 2018). Furthermore, as far as we know, no research has yet tested the predictive power of the core SCCT EI model in determining future nascent EB and new business creation. Although SCCT is less commonly used as cognitive framework in entrepreneurship research, it has been proposed to offer a more comprehensive view of the joint effects of personal and environmental factors on the cognitive determinants of career-related interests, intentions and behaviors (Liguori et al. 2018; Meoli et al. 2020). The EEP Portugal research project (Belchior 2019), in the context of the greater international Entrepreneurship Education Project (Vanevenhoven and Liguori 2013), collected data from Portuguese college students with SCCT used as the theoretical framework of reference. This project created an opportunity to make a contribution: (1) by enabling a test of the SCCT’s applicability to different careers and populations—considered essential for its establishment outside of its original literature (Lent et al. 1994)—in this case to entrepreneurship and to Portuguese college students, and (2) by addressing calls for more integration of other disciplines contributions (cf. Ireland and Webb 2007) and for a careful application of all models imported from other areas of research (Kenworthy and McMullan 2012).

Measurement instrument issues

From the measurement model results, it is relevant to note that Thompson's (2009) 6-item EI scale (modified) was found to be less reliable than originally reported and to show less convergent validity than the proposed threshold. This result, together with a loose implicit definition that appears to venture into the concept of nascent behavior, led to substantial item reduction. The 4-item entrepreneurial outcome expectations (EOE) scale (Vanevenhoven and Liguori 2013) was also found to lack acceptable convergent and external validity given the likely motivations of a population of, mainly, young adults. Improving these shortcomings was possible by removing the item related to ‘Family security’. Finally, McGee et al.'s (2009) 19-item entrepreneurial self-efficacy beliefs (ESE) scale (here adapted to 20 items) was found useful for measuring the ESE of Portuguese HEI students.

In line with Bird (2015), these findings suggest that future research should try to improve EI measurement by aiming for greater discriminant validity rather than for a better link to subsequent behavior. Regarding EOE, this measure should probably be adapted to incorporate motivations and expectations of the studied population and/or to avoid a construct that is a mere sum of several types of entrepreneurship-related outcomes into a single construct, particularly since traditionally SCCT models have discarded the valence component of the expectancy-value model (cf. Lent and Brown 2006) and/or perhaps subdivided it into different types of EOE subconstructs (e.g., Lanero et al. 2015, 2016).

Cross-section analysis

Considering the confirmatory research design of this paper, in testing hypothesis H1 with a parsimonious version of the SCCT model (i.e., its core component, including ESE and EOE as the only determinants of EI) for a sample of 1,149 higher education students, evidence was found in support of such a model given that (1) it provided an acceptable fit to the sample and explained 31.3% of the students EI’s variance, and (2) all modeled effects of ESE and EOE on EI and of ESE on EOE were found to be statistically significant. Overall, these results confirm existing evidence of previous comparable research, i.e., using SCCT to explain the EI of college students, confirming model fit and providing explanatory power close to the known range of 33% to 53% of EI total variance explained (Lanero et al. 2015; Chen 2013; respectively). Regarding effect sizes, this study’s results are, approximately, within the following ranges from the literature, we find a std. effect of 0.492 for the structural path between ESE-EI, which is within the known range of 0.35 to 0.67; a std. effect of 0.183 for the structural path between EOE-EI, which is within the known range of insignificance to 0.51; and a std. effect of 0.207 for the structural path between ESE-EOE, which is close to the known range of 0.25 to 0.39 though slightly below this range (cf. Segal et al. 2002; Vázquez et al. 2010; Liguori 2012; Chen 2013; Lanero et al. 2015; Austin and Nauta 2016; Lanero et al. 2016; Pfeifer et al. 2016). The empirical evidence regarding the application of SCCT to EI is still in its infancy when compared to the use of the TPB (Ajzen 1991, 2012) and Shapero’s SEE (Shapero and Sokol 1982) models; however, thus far, and based on the present results and those of comparable research, it appears that SCCT, in its most parsimonious form, shows considerable promise.

Moreover, entrepreneurial outcome expectations (EOE) appear to be the weak link of the theory’s application to intentionality as evidenced by the small effect found and by the inconsistent loadings reported in the comparable literature (e.g., Segal et al. 2002; Lanero et al. 2015, 2016). This lesser effect is not only not predicted by SCCT but is also counterintuitive, as one is more likely to think of behavioral choice based on expectations of the most valuable outcomes from a list of (perceived) feasible activities. As such, it may be relevant to (1) further explore EOE measurement and the adjustment of its scale items to the studied population expectations and (2) to further study the EOE-EI relationship since outcome expectations and motivations related to EB can be varied (e.g., Shane et al. 1991; Birley and Westhead 1994; Kolvereid 1996).

In sum, from our cross-sectional analysis, it appears that students’ assessments of their own capabilities to perform entrepreneurship-related tasks and their expectations about the benefits associated with the creation of a new business are related to their intentions. In this respect, it must be added that ESE explained considerably more EI variance than EOE, which is not predicted by SCCT. This difference can be due to EOE measurement issues such as the expected outcomes not being the most desired by the specific population and/or outcomes that are not exclusive to an entrepreneurial career. If so, a potential solution to this problem may involve the use of population-specific EOE measures and limiting the investigated/measured outcomes to those that are perceived as intrinsic to entrepreneurship, rather than those that can also be expected from organizational employment.

Longitudinal analysis (5 years)

The final focus of the empirical analysis was to test the capability of a SCCT-based intentions model to predict Nascent EB (hypothesis H2) and Business Creation (hypothesis H3) within a time window of 5 years. A reduced number of 242 students completed both the first and last survey, which were implemented in the academic years of 2010–2011 (T0) and 2015–2016 (T5), respectively. Business Creation, intuitively, was identified when students reported having created their own new businesses, and Nascent EB, was identified when students reported the performance of any activity deemed conductive to new business creation (e.g., investing one’s own money, hiring personnel, buying or renting facilities or equipment, etc.) or actually having created their own businesses. Within this period, at least 7.66% of the participants (88 students) engaged in Nascent EB, and at least 3.48% (40 students) succeeded. These rates are in line with the 1.42% business creation rate given in Delanoë-Gueguen and Liñán (2019) study of French University students for a similar 5-year period.

As proposed by SCCT, the performance of nascent entrepreneurial activities was significantly explained by the model’s core cognitive constructs, which together explained 20.8% of the dependent variable’s variance. However, this only lends partial support to hypothesis H2, as only intentions were found to be significantly associated with the dependent variable. In fact, contrary to SCCT framework postulations, entrepreneurial self-efficacy beliefs and outcome expectations could not be found to add value to intentions’ predictive ability for Nascent EB. Hence, our results point to the centrality of intentions in translating the full effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and outcome expectations on the decision to act towards the creation of a new business. In terms of prediction, knowing students’ intentions appears to be sufficient, but caution is advised when trying to generalize such findings since this can relate to ESE and EOE measurement. Further research into these relationships is still needed before rejecting the respective SCCT framework propositions.

For hypothesis H3, we found mixed support for the ability of a parsimonious version of the SCCT model to predict the creation of a new business within the study’s 5-year timeframe. Namely, while the model was able to significantly explain 34.8% (p. = 0.003) of the dependent variable’s variance, contrary to SCCT propositions, entrepreneurial self-efficacy beliefs did not directly explain why some nascent entrepreneurs were able to create their own new businesses while others did not.

Given that self-efficacy beliefs have been related to important cognitive and behavioral outcomes such as goal difficulty, initiating and persisting at behavior under uncertainty, the likelihood of exposure to mastery experiences and reducing threat rigidity and learned helplessness (Bandura 1986; Markman et al. 2002), we find this result especially surprising. This result may be indicative of a measurement instrument shortcoming related to the specific ESE measure used here or a general limitation of ESE measures in capturing all entrepreneurship relevant self-efficacy effects. Thus, in future research, we suggest that new measures or conceptualizations of self-efficacy be implemented to shed further light on this finding.

In sum, a parsimonious version of the SCCT model was able to explain college students’ entrepreneurial intentions, and the model’s explanatory power and effect sizes between constructs were of similar magnitude to those reported in comparable studies. Despite empirically unsurprising, when considering previous results of the literature, finding outcome expectations much less explicative of intentions than self-efficacy beliefs is still unintuitive and not theoretically supported. We see this as a research opportunity to further the ability for SCCT to predict entrepreneurial intentions.

Under a 5-year longitudinal research design and focusing only on the theory´s core cognitive constructs, the SCCT model proved capable of predicting both nascent entrepreneurial behavior and successful new business creation. However, only entrepreneurial intentions were predictive of later engagement in nascent entrepreneurial activities—and, to a minor degree, of successful new business creation—while self-efficacy beliefs and outcome expectations, surprisingly, were not. New business creation, while following nascent behavior, could not be significantly explained by entrepreneurial self-efficacy as proposed in the model. Consequently, we again call for research focusing on construct measurement improvement and/or on new construct conceptualization.

Finally, in line with more recent research, we do not find support for the model’s superior explanatory power of EI, as suggested by Segal et al. (2002), when compared to more popular models (i.e., SEE: Shapero and Sokol 1982; Ajzen 1991, 2012). Likewise, the study’s preliminary evidence on SCCT’s predictive ability for nascent entrepreneurial behavior and successful new business creation is also in line with other models in the literature.

Conclusions

Implications and avenues for future research

As Churchill and Bygrave stated, “Entrepreneurship is a process of becoming rather than a state of being. It is not a steady state phenomenon. Nor does it change smoothly. It changes in quantum jumps” (1990, p. 21). This study illustrates the relevant application of social cognitive career theory in the prediction of entrepreneurial intentions and behavior for cross-sectional and longitudinal research. With our cross-sectional analysis, we contributed to the scarce empirical evidence in the literature regarding the use of an SCCT model to predict intentions. Our results, together with those of others, suggest a need for a better measurement of the entrepreneurial outcome expectations construct, which is frequently observed to have less impact on intentions than entrepreneurial self-efficacy beliefs. Population-specific measures and constructs focusing on entrepreneurship-intrinsic outcome expectations may be needed to find more balanced and explicative cognitive intentions models.

Based on our 5-year longitudinal analysis, we were able to study, for the first time, the predictive ability of SCCT’s core cognitive constructs to predict college students’ entrepreneurial behavior. Only partial support was found given past intentions relevance and entrepreneurial outcome expectations and self-efficacy beliefs irrelevance in predicting nascent behavior and, residually, new business creation. Regarding self-efficacy, a lack of relevance explaining entrepreneurial behavior beyond intentions suggests the need for novel construct conceptualization or improved measurement.

SCCT proposes intentions to be formed by perceptions of capability and outcome expectations, and we find support for such a proposition, though more than two-thirds of entrepreneurial intentions variance was left unexplained. These results did not significantly differ from those of the ex ante literature, i.e., based on SCCT or other more popular intentions models applied to entrepreneurship. Despite being theoretically supported, empirically testing the intentions-behavior link in entrepreneurship faces many challenges. Our results confirm intentions as the model’s relevant cognitive construct for predicting entrepreneurial behavior but also pinpoint several inconsistencies that must still be resolved. Addressing these issues will improve our ability to explain and predict emerging and successful new business ventures and to support educators and policymakers seeking to promote and support college students’ new business creation.

Limitations

While this study’s methodology is considered robust, a number of limitations are acknowledged. First, with respect to data collection and measurement, the survey instruments used were imported from other studies and may not be fully adapted to the specific context of the studied population. In addition, both entrepreneurial outcome expectations and intentions were trimmed in terms of considered items, due to reliability and validity issues. Researchers are encouraged to check for measurement instrument robustness in their respective contexts if mirroring this study. As with most empirical studies, the reader should be cautious when venturing into generalizing this study’s findings outside the context of Portuguese higher education students. For example, our sample is mostly comprised of business school students, with Business and Business and Economics students accounting for 80.9% of the final sample.

Additionally, the entrepreneurial intentions measure used did not impose a time window for intentions implementation (i.e., engagement in entrepreneurial behavior), resulting in a decrease in the model’s explanatory power every time: (1) students’ high intention levels refer to plans falling outside the study’s timeframe and (2) students changed their intentions during the study. Future longitudinal research using lengthier time windows is welcomed, however causation could be more confidently inferred if intention levels were periodically assessed and if stability were measured, and incorporated into the model, until intentions are acted upon. Using shorter time windows may also improve the results and quality of the research design, but it may be argued that it reduces practical interest in studying intentions for future behavior.

Due to follow-up survey attrition, only 21.06% of the students participated for the entire duration of the longitudinal study. Though not ideal, this was expected, given previous reports from the ex ante literature (e.g., Audet 2004; Liñán and Rodríguez-Cohard 2008: Goethner et al. 2012; Shinnar et al. 2018). In analyzing differences between the fully participating respondents and dropouts, we found that at T0, those with prior entrepreneurial experience, those who were graduates and those with entrepreneurial education were considerably more likely to participate for the full duration of the study while those enrolled in business program were less likely to do so. However, our study focused on constructs relationships and not mean values. Therefore, we find no reason to believe that such attrition may be a relevant source of bias.

Data availability

The data from EEP Portugal Dataset, in which this study was based upon, may be provided upon request to the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Nascent entrepreneurs are defined as “individuals who initiate serious activities that are intended to lead to the formation of a viable new venture, but have not finally become legal business owners” (Zapkau et al. 2017, p. 56).

Following McGee’s et al. (2009) seminal article, all EFAs were performed via principal component analysis (PCA) extraction and varimax with Kaiser normalization as the rotation method.

Although some authors (e.g., McGee et al. 2009) have used a validation criterium of ‘at least two activities’ to identify a nascent entrepreneur, here, to be more confident of real nascent behavior, three activities were excluded from the previous list, as these did not meet the same standards as the rest in assuring the identification of dedicated/purposeful EB. Namely, the following activities were considered ineligible: (7) ‘Developed models’, (12) ‘Attended a ‘start your own business’ seminar or conference’ and (13) ‘Wrote a business plan or participated in seminars that focus on writing a business plan.’ To compensate for this reduced domain of eligible activities, it was considered sufficient for only one of all other nascent activities to be completed for someone to be identified as having behaved entrepreneurially.

References

Adam, A. F., & Fayolle, A. (2016). Can implementation intention help to bridge the intention–behaviour gap in the entrepreneurial process? An experimental approach. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 17(2), 80–88.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Ajzen, I. (2012). The theory of planned behavior. In P. Lange, A. Kruglanski, & E. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 438–459). London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–499.

Audet, J. (2004). A longitudinal study of the entrepreneurial intentions of university students. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 10(1), 3–16.

Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., & Desai, S. (2015). Entrepreneurship and economic development in cities. The Annals of Regional Science, 55(1), 33–60.

Austin, M. J., & Nauta, M. M. (2016). Entrepreneurial role-model exposure, self-efficacy, and women’s entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Career Development, 43(3), 260–272.

Azen, R., & Sass, D. A. (2008). Comparing the squared multiple correlation coefficients of non-nested models: An examination of confidence intervals and hypothesis testing. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 61(1), 163–178.

Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217–254.

Bagozzi, R. P., Baumgartner, J., & Yi, Y. (1989). An investigation into the role of intentions as mediators of the attitude-behavior relationship. Journal of Economic Psychology, 10(1), 35–62.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Belchior, R. F. (2019). Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions & behavior: Social cognitive career theory test, new propositions and longitudinal analysis. Tese de doutoramento. Lisboa: ISCTE-University Institute of Lisbon.

Bird, B. (2015). Entrepreneurial intentions research: A review and outlook. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 13(3), 143–168.

Bird, B., & Jelinek, M. (1989). The operation of entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 13(2), 21–30.

Birley, S., & Westhead, P. (1994). A taxonomy of business start-up reasons and their impact on firm growth and size. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(1), 7–31.

Bogatyreva, K., Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T. S., Osiyevskyy, O., & Shirokova, G. (2019). When do entrepreneurial intentions lead to actions? The role of national culture. Journal of Business Research, 96, 309–321.

Byrne, B. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York: Routledge.

Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., & Reynolds, P. D. (1996). Exploring start-up event sequences. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(3), 151–166.

Chen, L. (2013). IT entrepreneurial intention among college students: An empirical study. Journal of Information Systems Education, 24(3), 233–243.

Churchill, N. C., & Bygrave, W. D. (1990). The entrepreneurship paradigm (II): Chaos and catastrophes among quantum jumps? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 14(2), 7–30.

Coad, A., Segarra, A., & Teruel, M. (2016). Innovation and firm growth: Does firm age play a role? Research Policy, 45(2), 387–400.

Cordeiro, P. M., Paixão, M. P., Lens, W., Lacante, M., & Luyckx, K. (2015). Cognitive–motivational antecedents of career decision-making processes in Portuguese high school students: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 90, 145–153.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334.

Davidsson, P., & Gordon, S. R. (2011). Panel studies of new venture creation: A methods-focused review and suggestions for future research. Small Business Economics, 39(4), 853–876.

Degeorge, J. M., & Fayolle, A. (2011). The entrepreneurial process trigger: A modelling attempt in the French context. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 18(2), 251–277.

Delanoë-Gueguen, S., & Liñán, F. (2019). A longitudinal analysis of the influence of career motivations on entrepreneurial intention and action. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 36(4), 527–543.

Efron, B., & Tibshirani, R. (1986). Bootstrap methods for standard errors, confidence intervals, and other measures of statistical accuracy. Statistical Science, 1(1), 54–75.

Esfandiar, K., Sharifi-Tehrani, M., Pratt, S., & Altinay, L. (2019). Understanding entrepreneurial intentions: A developed integrated structural model approach. Journal of Business Research, 94, 172–182.

Fayolle, A., & Liñán, F. (2014). The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 663–666.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388.

Gartner, W. B. (1988). “Who is an entrepreneur?” is the wrong question. American Journal of Small Business, 12(4), 11–32.

Gartner, W. B., Carter, N. M., & Reynolds, P. D. (2010). Entrepreneurial behavior: Firm organizing processes. In Z. J. Acs & D. B. Audretsch (Eds.), Handbook of entrepreneurship research (pp. 99–127). New York: Springer, New York.

Gieure, C., Benavides-Espinosa, M., & d. M., & Roig-Dobón, S. . (2020). The entrepreneurial process: The link between intentions and behavior. Journal of Business Research, 112, 541–548.

Goethner, M., Obschonka, M., Silbereisen, R. K., & Cantner, U. (2012). Scientists’ transition to academic entrepreneurship: Economic and psychological determinants. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(3), 628–641.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1993). Goal achievement: The role of intentions. European Review of Social Psychology, 4(1), 141–185.

Guerrero, M., & Urbano, D. (2014). Academics’ start-up intentions and knowledge filters: An individual perspective of the knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 43(1), 57–74.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. A global perspective. New Jersey: Pearson.

Heuer, A., Aouni, Z., Pirnay, F., & Surlemont, B. (2009). The evolution of new venture creation intention: A longitudinal study. ICSB world conference (pp. 1–19). Washington: International Council for Small Business (ICSB). Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/conference-papers-proceedings/evolution-new-venture-creationintention/docview/192412291/se-2?accountid=39066

Hills, G. E., & Singh, R. P. (2004). Opportunity recognition. In W. B. Gartner, K. G. Shaver, N. M. Carter, & P. D. Reynolds (Eds.), Handbook of entrepreneurial dynamics: The process of business creation (pp. 259–272). London: Sage Publications Inc.

Hirschi, A. (2013). Career decision making, stability, and actualization of career intentions: The case of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Career Assessment, 21(4), 555–571.

Hui-Chen, C., Kuen-Hung, T., & Chen-Yi, P. (2014). The entrepreneurial process: An integrated model. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(4), 727–745.

Hulsink, W., & Rauch, A. (2010). The effectiveness of entrepreneurship education: A study on an intentions-based model towards behavior. ICSB world conference (pp. 1–25). Cincinnati: International Council for Small Business.

Ireland, R. D., & Webb, J. W. (2007). A cross-disciplinary exploration of entrepreneurship research. Journal of Management, 33(6), 891–927.

Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39(1), 31–36.

Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M., & Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(3), 655–674.

Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M., & Tornikoski, E. T. (2013). Predicting entrepreneurial behaviour: A test of the theory of planned behaviour. Applied Economics, 45(6), 697–707.

Kenworthy, T. P., & McMullan, W. (2012). Importing theory (Summary). Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 32(20), Article 1.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Publications.

Kolvereid, L. (1996). Organizational employment versus self-employment: Reasons for career choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 20(3), 23–31.

Kolvereid, L., & Isaksen, E. (2006). New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(6), 866–885.

Krueger, N. (2009). Entrepreneurial intentions are dead: Long live entrepreneurial intentions. In M. Brännback & A. L. Carsrud (Eds.), Understanding the entrepreneurial mind (pp. 51–72). New York: Springer, New York.

Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5–6), 411–432.

Lanero, A., Vázquez, J. L., & Aza, C. L. (2016). Social cognitive determinants of entrepreneurial career choice in university students. International Small Business Journal, 34(8), 1053–1075.

Lanero, A., Vázquez, J. L., & Muñoz-Adánez, A. (2015). Un modelo social cognitivo de intenciones emprendedoras en estudiantes universitarios. Anales de Psicología, 31(1), 243–259.

Lent, R. W. (2005). A social cognitive view of career development and counseling. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 101–127). Hoboken: Wiley.

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2006). On conceptualizing and assessing social cognitive constructs in career research: A measurement guide. Journal of Career Assessment, 14(1), 12–35.

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2019). Social cognitive career theory at 25: Empirical status of the interest, choice, and performance models. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 115, 103316.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2000). Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(1), 36–49.

Lent, R. W., do CéuTaveira, M., Cristiane, V., Sheu, H. B., & Pinto, J. C. (2018). Test of the social cognitive model of well-being in Portuguese and Brazilian college students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 109, 78–86.

Lent, R. W., do CéuTaveira, M., Cristiane, V., Sheu, H. B., & Pinto, J. C. (2018). Test of the social cognitive model of well-being in Portuguese and Brazilian college students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 109, 78–86.

Lent, R. W., Ireland, G. W., Penn, L. T., Morris, T. R., & Sappington, R. (2017). Sources of self-efficacy and outcome expectations for career exploration and decision-making: A test of the social cognitive model of career self-management. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 99, 107–117.

Lent, R. W., Paixão, M. P., Silva, J. T., & d., & Leitão, L. M. . (2010). Predicting occupational interests and choice aspirations in Portuguese high school students: A test of social cognitive career theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(2), 244–251.

Liguori, E. (2012). Extending social cognitive career theory into the entrepreneurship domain: Entrepreneurial self-efficacy’s mediating role between inputs, outcome expectations, and intentions. Doctoral Thesis. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College.

Liguori, E. W., Bendickson, J. S., & McDowell, W. C. (2018). Revisiting entrepreneurial intentions: A social cognitive career theory approach. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(1), 67–78.

Liñán, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 907–933.

Liñán, F., & Rodríguez-Cohard, J. C. (2008). Temporal stability of entrepreneurial intentions: A longitudinal study. In 48th congress of the european regional science association (pp. 1–18). Liverpool, UK.

Liñán, F., & Rodríguez-Cohard, J. C. (2015). Assessing the stability of graduates’ entrepreneurial intention and exploring its predictive capacity. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 28(1), 77–98.

Lucas, W. A., & Cooper, S. Y. (2012, November). Theories of entrepreneurial intention and the role of necessity. In Proceedings of the 35th ISBE Conference (pp. 7–8). Dublin, Ireland: Institute of Small Business and Entrepreneurship.

Malhotra, N. K., & Dash, S. (2011). Marketing research an applied orientation. London: Pearson Publishing.

Mardia, K. V. (1970). Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika, 57(3), 519–530.

Markman, G. D., Balkin, D. B., & Baron, R. A. (2002). Inventors and new venture formation: The effects of general self-efficacy and regretful thinking. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(2), 149–165.

McGee, J. E., Peterson, M., Mueller, S. L., & Sequeira, J. M. (2009). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: Refining the measure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(4), 965–988.

McKenzie, B., Ugbah, S., & Smothers, N. (2007). “Who is an entrepreneur?” Is it still the wrong question? Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 13(1), 23–44.

Meoli, A., Fini, R., Sobrero, M., & Wiklund, J. (2020). How entrepreneurial intentions influence entrepreneurial career choices: The moderating influence of social context. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(3), 105982.

Mitchell, R. K., Busenitz, L., Lant, T., McDougall, P. P., Morse, E. A., & Smith, J. B. (2002). Toward a theory of entrepreneurial cognition: Rethinking the people side of entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(2), 93–104.

Mueller, R. O., & Hancock, G. R. (2008). Best practices in structural equation modeling. In J. W. Osborne (Ed.), Best practices in quantitative methods (pp. 488–508). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Neneh, B. N. (2019). From entrepreneurial alertness to entrepreneurial behavior: The role of trait competitiveness and proactive personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, 273–279.

Özyürek, R. (2005). Informative sources of math-related self-efficacy expectations and their relationship with math-related self-efficacy, interest, and preference. International Journal of Psychology, 40(3), 145–156.

Pfeifer, S., Šarlija, N., & Zekić Sušac, M. (2016). Shaping the entrepreneurial mindset: Entrepreneurial intentions of business students in croatia. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(1), 102–117.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Reynolds, P. D., Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., & Greene, P. G. (2004). The prevalence of nascent entrepreneurs in the united states: Evidence from the panel study of entrepreneurial dynamics. Small Business Economics, 23(4), 263–284.

Schlaegel, C., & Koenig, M. (2014). Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta-analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 291–332.

Schumacker, R., & Lomax, R. (2004). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. London: Routledge.

Segal, G., Borgia, D., & Schoenfeld, J. (2002). Using social cognitive career theory to predict self-employment goals. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 5(2), 47–56.

Shane, S., Kolvereid, L., & Westhead, P. (1991). An exploratory examination of the reasons leading to new firm formation across country and gender. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(6), 431–446.

Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In C. A. Kent, D. L. Sexton, & K. H. Vesper (Eds.), Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship (pp. 72–90). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Shaver, K. G. (2010). The social psychology of entrepreneurial behavior. In Z. J. Acs & D. B. Audretsch (Eds.), Handbook of entrepreneurship research (pp. 359–385). New York: Springer, New York.

Shaver, K. G., & Scott, L. R. (1991). Person, process, choice: The psychology of new venture creation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(2), 23–46.

Sheeran, P., Orbell, S., & Trafimow, D. (1999). Does the temporal stability of behavioral intentions moderate intention-behavior and past behavior-future behavior relations? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(6), 724–734.

Sheppard, B. H., Hartwick, J., & Warshaw, P. R. (1988). The theory of reasoned action: A meta-analysis of past research with recommendations for modifications and future research. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(3), 325–343.

Sheu, H. B., Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., Miller, M. J., Hennessy, K. D., & Duffy, R. D. (2010). Testing the choice model of social cognitive career theory across Holland themes: A meta-analytic path analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(2), 252–264.

Shinnar, R. S., Hsu, D. K., Powell, B. C., & Zhou, H. (2018). Entrepreneurial intentions and start-ups: Are women or men more likely to enact their intentions? International Small Business Journal, 36(1), 60–80.

Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O., & Bogatyreva, K. (2016). Exploring the intention–behavior link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. European Management Journal, 34(4), 386–399.

Shook, C. L., Priem, R. L., & McGee, J. E. (2003). Venture creation and the enterprising individual: A review and synthesis. Journal of Management, 29(3), 379–399.

Sommer, L. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour and the impact of past behaviour. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 10(1), 91–110.

Thompson, E. R. (2009). Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 669–694.

Van Gelderen, M., Kautonen, T., & Fink, M. (2015). From entrepreneurial intentions to actions: Self-control and action-related doubt, fear, and aversion. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(5), 655–673.

Vanevenhoven, J., & Liguori, E. (2013). The impact of entrepreneurship education: Introducing the entrepreneurship education project. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(3), 315–328.

Vázquez, J., Lanero, A., Gutiérrez, P., García, M., Alves, H., & Georgiev, I. (2010). Entrepreneurship education in the university: Does it make the difference? Trakia Journal of Sciences, 8(3), 64–70.

Walter, S. G., & Heinrichs, S. (2015). Who becomes an entrepreneur? A 30-years-review of individual-level research. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 22(2), 225–248.

Wang, X. (2013). Why students choose STEM majors: Motivation, high school learning, and postsecondary context of support. American Educational Research Journal, 50(5), 1081–1121.

Wennekers, S., & Thurik, R. (1999). Linking entrepreneurship and economic growth. Small Business Economics, 13(1), 27–56.

Weston, R., & Gore, P. A. (2006). A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(5), 719–751.

Williams, L. J., Hartman, N., & Cavazotte, F. (2010). Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 477–514.

Wright, S. L., Perrone-McGovern, K. M., Boo, J. N., & White, A. V. (2014). Influential factors in academic and career self-efficacy: Attachment, supports, and career barriers. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(1), 36–46.

Zapkau, F. B., Schwens, C., & Kabst, R. (2017). The role of prior entrepreneurial exposure in the entrepreneurial process: A review and future research implications. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(1), 56–86.

Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272.

Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2010). The relationship of personality to entrepreneurial intentions and performance: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Management, 36(2), 381–404.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge financial support received from FCT- Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (Portugal) national funding, provided through research grant UIDB/04521/2020 and doctoral grant ref: SFRH/BD/73520/2010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RFB wrote the initial draft of this manuscript, after being directly involved in data collection (as the coordinator of the EEP Portugal research group), and its analysis (as part of his Ph.D. thesis: Belchior 2019).

RL has critically reviewed the paper’s first draft and made a major contribution to its final structure, focus and readability.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Nascent Entrepreneurial Behavior (Nascent EB) measurement was conducted based on the international Entrepreneurship Education Project’sFootnote 3 first follow-up survey citing Carter et al. (1996) for items 1 to 11 and McGee et al. (2009) for items 12 to 16 as questions asked of participants if they had completed any of the following nascent activities:

-

(1)

Bought facilities / equipment;

-

(2)

Rented facilities / equipment;

-

(3)

Looked for facilities;

-

(4)

Invested own money;

-

(5)

Asked for funding;

-

(6)

Got financial support;

-

(7)

Not applicable (see footnote)

-

(8)

Devoted fulltime to business;

-

(9)

Applied for license / patent;

-

(10)

Formed a legal entity;

-

(11)

Hired employees;

-

(12)

Not applicable (see footnote)

-

(13)

Not applicable (see footnote)

-

(14)

Put together a start-up team;

-

(15)

Saved money to invest in the business;

-

(16)

Developed a product or service.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Belchior, R.F., Lyons, R. Explaining entrepreneurial intentions, nascent entrepreneurial behavior and new business creation with social cognitive career theory – a 5-year longitudinal analysis. Int Entrep Manag J 17, 1945–1972 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-021-00745-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-021-00745-7

Keywords

- Entrepreneurial intentions

- Nascent entrepreneurial behavior

- Entrepreneurial outcome expectations

- Entrepreneurial self-efficacy

- Social cognitive career theory