Abstract

This paper deals with sibling rivalry dynamics and their impact on the succession outcome within family enterprises. While sibling rivalry plays a critical role in the succession process, there is only limited literature that addresses this important subject. This theoretical study reveals valuable insights on this topic and contributes to the existing literature. Particular attention is placed on parental behavior and attitude during childhood, sibling characteristics and the perception of parental fairness by the successors, which we advocate are the principal factors conducive not only to the emergence of rivalry among heirs but also to influencing the effectiveness of the succession outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Family-owned businesses are recognized today as an important and distinct organization in the world economy. A majority of businesses located around the world is family-owned with some of the most recognizable being Benetton, Estee Lauder and IKEA among others. But what exactly determines whether a business is a family-owned one? There are multiple definitions in answering this question. Three of the most representative are: (1) a business in which two or more extended family members influence the direction of the business (Davis and Tagiuri 1985); (2) the system that includes the business, the family, the founder and such linking organizations as the board of directors (Beckhard and Dyer 1983a), and; (3) family firms are defined as “a business governed and/or managed with the intention to shape and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family. . . in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family” (Chua et al. 1999, p. 35).

In terms of scholarship, a trend is emerging in the family business field in an attempt to integrate the thinking from multiple disciplines. This trend may result in the development of new theories that combine and synthesize the family firm and its concepts that are considered more mainstream in other disciplines. Such developments are already taking place along the fringes of family psychology and behavioral finance. As this trend continues, the family business field will become a discipline that gives back to other disciplines as much, if not more, than the field has received in theoretical and conceptual content, and this will help shape other disciplines as well (Zahra and Sharma 2004).

A recent review of family business research highlights the “jungle” of theories about family firms and their motivations (Rutherford et al. 2008). There are a slew of different approaches to understanding the behavior of family firms, the most common of which is agency theory. By comparing firms run by families to those not run by families, agency theory can be used to explain differences in performance and investment between the two. Family firms, who are run by the largest and most concerned shareholders, can be assumed to be run in a way most consistent with the firm’s shareholders. A focus on the potential agency theory implications of family businesses might help us understand how managers can appropriate family firm rents. However, by comparing family and non-family firms using agency theory suggests that one mode is perhaps more optimal for shareholder returns than another. This might not be the case. Indeed, other studies (e.g., Berrone et al. 2010; Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007) suggest that family members who run family firms make decisions in a way that is potentially very different from those run by professional managers. Firms that are run by families in most cases display and value socioemotional wealth rather than wealth per se, and family members who run a family firm have a longer-term focus and engage in more socially acceptable endeavors (such as polluting less than non-family firms for example) because their personal image is tightly wound into the behavior and operation of the family firm (Berrone et al. 2010). Additionally, family members have a more encompassing perspective on the firm as a whole and focus less exclusively on the firm’s profitability, as they gain additional socioemotional wealth through running the firm for the family and for just impersonal stockholders (Cruz et al. 2010).

By the same token however, it has been observed that many family businesses terminate their operation even before the founder passes the baton onto the second generation. One of the key reasons –among others- for such incidents is poisonous rivalry among heirs and more specifically among siblings within the family resulting from an uneven distribution of family and business benefits from the family and the family firm, or even a total lack of socioemotional wealth among the siblings.

Sibling rivalry can be defined as the competitive relationship between siblings and is often associated with the struggle for parental attention, affection and approval, but also for recognition in the world. There are many mythological, historical and literary examples that highlight the gravity of sibling rivalries: Cain and Abel, Romulus and Remus, Eteocles and Polyneices, Richard the Lion-Hearted and John Lackland, among others. Such examples can bring into light valuable lessons regarding sibling dynamics within the family firm that spans from sibling rivalry during youth spilling into adulthood, to ultimately serious family conflict and dysfunctional family business succession. This means that sibling rivalry and dynamics should be viewed and examined from many theoretical perspectives, such as psychological, social psychological, and social symbolic, and not just from a business, economic, or legal perspectives. Sharma et al. (2007, p. 1019) drove home this very point when they emphatically stated that current research themes of management, succession and finance will become less dominant in the literature as scholars discover productive areas of investigation in education, entrepreneurship, psychology, sociology, political science and other fields. Hence, this paper represents an effort to identify the factors that influence sibling rivalry from an interdisciplinary perspective and furthermore an attempt to examine how such a rivalry may affect the succession process in a family firm.

Literature review

One of the greatest challenges for a family firm is to successfully transfer the business to the next generation. Thus, it comes as no surprise that succession is considered by the family business field as one of the most important issues and consequently it is addressed by a vast body of literature (Bird et al. 2002; Dyer and Sánchez 1998; Lambrecht and Donckel 2006; Handler 1994). Perhaps the most fundamental mission of a family business is to pass the business to subsequent generations (Davis 1968), and thus a successful succession is the keystone to survival in family business (Cabrera-Suarez et al. 2001; Shepherd and Zacharakis 2000; Davis and Harveston 1998; Barnes 1988). Succession is described as the transfer of leadership from one family member to another (American Family Business Survey 1997). According to the literature, only about 30 % of family firms survive to the second generation and only around 15 % make it to the third generation (Sonnenfeld 1988; Morris et al. 1997; Beckhard and Dyer 1983a, b).

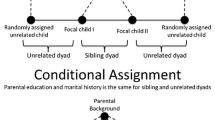

In order to most appropriately map an ongoing succession process, and identify its critical elements, Handler (1994) identified two interactive succession dimensions, namely, the satisfaction with the succession process and the effectiveness of the succession per se. The majority of research on family business succession has focused on how families can best prepare to hand the business over to the next generation while very little research has been devoted to studies that attempt to discover a set of factors that may prevent intra-family succession, such as sibling rivalry. Furthermore, according to Pyromalis and Vozikis (2009), the successful succession process whether intra-family or extra-family, entails succession effectiveness and satisfaction with succession by the rest of the family and non-family members. Their model focuses on five critical success factors that can influence and assist to a great extent the outcome of the succession process in a family firm: 1) The incumbent’s propensity to step aside, 2) the successor’s willingness to take over, 3) positive family relations and communication, 4) succession planning, and 5) the successor’s appropriateness and preparation (Exhibit 1).

Based on the model developed by Pyromalis and Vozikis (2009), we shall draw our attention toward relationship R5 (as depicted in Exhibit 1), namely, the relationship between Positive Family Relations and Communication and the Effectiveness of Succession Process as it applies to sibling relations and their influence in the effectiveness of the succession process. It is interesting to note here that there is a great deal of research regarding sibling relationships, but as mentioned earlier, mainly from a psychological and sociological point of view (Cicirelli 1994; Felson 1983; Goetting 1986; Lamb and Sutton-Smith 1982; Stewart et al. 1998). Most of this research focuses on the relationships of siblings during childhood and adolescence, whereas sibling relationships in adulthood have received very little research attention no matter what discipline we pick. Various articles (Boles 1996; Davis and Harveston 2001; Kaye 1991; Sorenson 1999) examined only the conflict in general within the family firm’s management, without dealing directly with sibling rivalry and how it influences the effectiveness of the succession process in a family firm. Thus, throughout this paper, we will attempt to formulate a conceptual framework for both researchers and practitioners aiming at filling this gap in the literature that hopefully will provide some guidance and better understanding of this very soft and delicate issue relating to succession in the family business and the business family.

Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework used in this paper is based upon an integration of the existing business literature on the issue of succession in family businesses, where the successors are siblings and children of the incumbent owner, as well as the literature from the fields of sociology and psychology concerning family and sibling dynamics. It also sets the foundations for forming a theoretical model, consisting of antecedent and intervening factors influenced by the former. The antecedent factors consist of the parental role during childhood, the specific sibling characteristics and the way the siblings perceive fairness in given family and business situations. These variables will first impact an intervening variable, namely, the quality of sibling relationships along with the degree of rivalry among siblings in adulthood, which in turn will ultimately affect the critical for the future of the family firm dependent variable of the overall effectiveness of the succession process. The conceptual framework as a theoretical model is graphically presented in Exhibit 2 depicting the direct and indirect influences among the variables mentioned above.

This theoretical conceptual model serves as a guide in formulating our main research propositions. We shall first present propositions concerning the impact of the intervening variable of the quality of sibling relationships in adulthood in terms of the degree of rivalry among siblings on the effectiveness of the succession process. We will then turn our attention to the effects of the antecedent variables, namely, the parental role, attitudes and behavior during the sibling childhood, the sibling characteristics, and the way the siblings perceive their treatment as fair relative to their brothers and sisters in given family and business situations, and formulate research propositions on their impact on the intervening variable of the quality of sibling relationships in adulthood in terms of degree of rivalry among them.

Succession outcome

Succession refers to the transfer of the management and/or the ownership of the family business (Griffeth et al. 2006) and as mentioned earlier, it has been one of the most vastly analyzed topics in the family business theoretical and empirical domain whether it is an intra or extra family succession (Bird et al. 2002; Dyer and Sánchez 1998). The focus of this paper however, is specifically placed on the case of an intergenerational transfer and intra-family succession, where a direct member or members of the incumbent’s family are the actual successors and possibly heirs (Griffeth et al. 2006).

The fact that only a mere 30 % of family businesses survives past the first generation, and only 10 % to 15 % survive to a third generation (Davis and Harveston 1998), raises the intriguing question as to what should be considered a successful succession outcome. According to Breton-Miller et al. (2004) a successful succession outcome is determined by two pillars: (1) the subsequent positive performance of the business and its viability, i.e. effectiveness of the succession process, and (2) the satisfaction of the stakeholders, either family or non-family members, with the overall succession process.

Previous literature has also identified a long list of characteristics and factors that affect the successful succession process which entails succession effectiveness and satisfaction with succession by the rest of the family and non-family members. The successful succession process whether intra-family or extra-family, i.e. outside the family, relies and is facilitated by five facilitating critical success factors identified by Pyromalis and Vozikis (2009) above, namely: 1) The incumbent’s propensity to step aside, 2) the successor’s willingness to take over, 3) positive family relations and communication, 4) succession planning, and 5) the successor’s appropriateness and preparation. Furthermore, and in contrast to succession critical success factors, De Massis et al. (2008) identified critical family firm succession hindering critical factors and forces of succession that serve as direct explanations and conditions inhibiting a successful intra-family succession in terms of effectiveness and family satisfaction with succession. Inhibiting a successful intra-family succession in terms of effectiveness and family satisfaction means that an efficacious succession does not materialize, because: 1) all potential family successors decline the management leadership of the business, 2) the dominant coalition rejects all potential family successors, and 3) the dominant coalition decides against family succession although acceptable and willing potential family successors exist.

Sibling relationship - sibling rivalry in adulthood

The relationship among siblings has been described as “the most enduring of all familial relationships” (Stewart et al. 1998). Moreover, the sibling bond is recognized for its uniqueness, attributed not only to the longevity of the relationship, but also to the shared genetic and social background of the siblings. More specifically, the adult sibling relationship plays a significant role in influencing the adult life in general, both psychologically and cognitively (Kang 2002). Nonetheless, the nature of the sibling relationship in adulthood is very complex, with many different factors affecting the sibling relationship and its various dimensions, one of them being past rivalry in childhood and adolescence (Stocker et al. 1997).

In addition, in the case of a family firm, adult sibling relationships have been suggested to affect the family business succession (Griffeth et al. 2006). We would expect therefore to find a negative correlation between intense sibling rivalry and the effectiveness of the succession process. In fact, Miller et al. (2003) point out that the stagnation that characterizes some successions may be a result of rivalry between brothers and sisters as they block one another’s actions.

Sibling rivalry not only can induce this type of stagnation, but even if intense sibling rivalry does not cause succession prospect stagnation, it can be organizationally destructive because it undermines fundamental alliances among adult siblings that are critically essential in family firms (Birley et al. 1999; Friedman 1991). In extreme cases sibling rivalry can even lead to a complete collapse of any prospects for succession and even worse, a subsequent dissolution of the family firm, while a successful succession is more likely to occur with low levels of rivalry, high levels of trust and shared values among siblings (Morris et al. 1997). Therefore:

-

Research Proposition P1:

The lower the quality of sibling relationships in adulthood, the more likely the family firm succession process outcome will be unsuccessful, all else being equal.

-

Research Proposition P1a:

The lower the quality of sibling relationships in childhood, the more likely the quality of sibling relationships in adulthood will be also lower in family and family business situations conceivably resulting in sibling rivalry, all else being equal.

-

Research Proposition P1a:

Parental role: attitudes and behaviors during childhood

The role of the parents is extremely crucial for the quality of the sibling relationships during childhood. Parental attitudes and behavior exhibited through constant sibling comparisons, contrasts and inferences can have a profound effect on whether rivalry will be incited and bred among their children. As Friedman (1991) and Lamb and Sutton-Smith (1982) indicate, dysfunctional parental attitudes and behaviors, such as stereotyping or incessant preferential treatment, can foster hostile sibling rivalries in childhood. This happens because children develop feelings of competitiveness over parental love and attention and extreme resentfulness, if they do not get their way.

It would be interesting however, to explore whether these rivalries are carried over to adulthood. There is a debate in the literature whether such rivalries endure over time and stay alive in adulthood. Although Lamb and Sutton-Smith (1982) denote a diminishing in intensity of sibling rivalry with age, Friedman (1991) observes that “destructive rivalries can and do persist over the sibling life span”. Furthermore, he advocates that even if parents are no longer alive, the sibling dynamics set in motion during childhood tend to be more or less stable with very little change over time, just like an individual’s personality. Moreover, Tonti (1988) argues that intense residual rivalries from childhood may be reactivated under stressful family and family business situations, as during the critical process of a family firm transfer, succession and inheritance. Of course, the rivalry dimension of sibling relationships may be less pronounced in adulthood than in childhood, since adult siblings are hopefully more mature and are able to select the degree, the extent, and the timing of contact they have with each other, unlike their time together during childhood (Stocker et al. 1997). Additionally, more or less mature individuals can hide their true feelings easier than they were able to do as children. Any dysfunctional attitudes and behaviors of parents during childhood therefore, will create hostile sibling rivalries in childhood that are very likely to be carried over in adulthood and thus affect negatively adult sibling relationships in both family and family business situations.

Friedman (1991) identified three main dimensions of the positive and negative impact and outcomes of parental attitudes and behavior that influence sibling relationships: Inter-sibling relationship comparisons, sibling perception and sense of justice in parental treatment allocation of familial resources and parental role in their children’s conflict resolution attempts. These three dimensions are depicted below in the form of a continuum with the positive outcomes on the left end and the negative outcomes on the right (see Exhibit 3).

Comparisons of children by their parents are inevitable, but the way they are made and expressed by the parents can influence “how children ultimately value themselves as individuals” (Friedman 1991). In terms of excessive parental assistance Padilla-Walker et al. (2012) found that when parents cover everything financially regardless of justification, their children worked the fewest hours and were engaged in the greater number of risk behaviors defined as drinking, binge drinking, smoking and marijuana use. More than 60 % of today’s young adults have received financial help from their parents and those described as being more cheerful, self-reliant, and got along well with others before age 12, i.e. having more agreeable personalities overall, seem to be receiving more assistance than their other siblings in terms of financial gifts or loans as young adults (Jayson 2012). Parental assistance can be constructive to the extent that it bears on characteristics that can be influenced by a child’s efforts (e.g. level of achievement) and is based on the appreciation of each child’s unique qualities in terms of flexible individuation. In such case, children will feel loved for their own sake and will not be urged to outdo their “sibling rivals” in order to garner their parents’ affection. On the contrary, labeling and comparisons that are made on the basis of characteristics which cannot be controlled by the child such as gender or intelligence, (“your brother got all the brains”, for example), will result in rigid parental sibling stereotyped classifications that can even stick and remain in play for a lifetime and ultimately result in acute competitiveness among the siblings for parental rewards in an attempt to generate socioemotional wealth for them.

The sense of justice in terms of equity vs. equality in parental treatment is also extremely critical for preventing sibling rivalry. The way parents treat their children, as well as the way the family’s tangible and intangible resources, such as attention or affection for example, are allocated among children the stronger the impact on the quality of sibling relationships in childhood and later on in adulthood. Parents should avoid generating perceptions of preferential or unfair treatment and distribute tangible and intangible resources fairly, in the sense of acknowledging their offspring’s individual differences and individual needs (equity instead of equality). In this context, children will learn to value and respect the needs of others; otherwise feelings of ill will and resentment will emerge among siblings and linger through adulthood, because these kinds of detrimental perceptions become baggage carried from childhood to adulthood.

Finally, the parental role in conflict resolution is important in the sense that for parents to allow their children to learn on their own how to resolve their differences independently so as to develop autonomy and self-reliance. Conversely, when parents become excessively involved in the siblings’ attempts to resolve conflict between and among them, the children will remain dependent on their parents’ authority to settle differences, and will most likely be unable to rely later on during adulthood on their own judgment to bring forth positive outcomes to ordinary and, even worse, sometimes extraordinary incidents of skirmishes within the family and the family firm. Such continuous and unquestionable parental interference and interjection in attempts for conflict resolution among siblings will more likely exacerbate sibling rivalry and render resolutions impossible to achieve later on when the children become adults and face the world on their own. In light of the above:

-

Research Proposition P2:

The higher the level of overall dysfunctional negative parental attitudes and behaviors during the siblings’ childhood, the more likely the quality of sibling relationships in adulthood will be lower in family and family business situations conceivably resulting in sibling rivalry, all else being equal.

-

Research Proposition P2a:

The more frequent and intense the inter-sibling competitive stereotyped classifications and differentiating comparisons made by parents during the sibling’s childhood, the more likely the quality of sibling relationships in adulthood will be lower in family and family business situations conceivably resulting in sibling rivalry, all else being equal.

-

Research Proposition P2b:

The higher the sense and the perception by children of unfairness and preferential treatment in the allocation by parents of familial resources creating socioemotional wealth during childhood, the more likely the quality of sibling relationships in adulthood will be lower in family and family business situations conceivably resulting in sibling rivalry, all else being equal.

-

Research Proposition P2c:

The more frequent and the higher the level of parental interference in children’s attempts for conflict resolution during childhood, the more likely the quality of sibling relationships in adulthood will be lower in family and family business situations conceivably resulting in sibling rivalry, all else being equal.

-

Research Proposition P2a:

Sibling characteristics

By sibling characteristics we refer to attributes such as the age gap among siblings (how many years apart are the siblings), gender (brothers, sisters or a combination of both), the number of siblings in the family, whether the offspring are multiple birth siblings (i.e. twins or triplets etc.), the educational background, as well as the professional expertise within or/and outside the family firm. The more exacerbated these characteristics are the higher the likelihood that the siblings will be sharing fewer experiences together and may grow as individual “islands” rather than true brothers and sisters. As a result these different experiences and characteristics from childhood may also transcend into later years causing sibling rivalry lasting into adulthood. Although there is scant literature concerning these characteristics and attributes, especially in the business field, we would expect that each one of them would have a different impact on the interpersonal dynamics among siblings, and subsequently a different association with sibling rivalry. Research, for example, has shown that siblings who are further apart in age perceive less conflict in their relationships than siblings who are closer in age (Stewart et al. 1998; Stocker et al. 1997).

A similar conclusion is drawn by Grote (2003), in the sense that “a sibling-boss” will feel less pressure from a much younger sibling than from one closer in age, justified by the fact that as the distance decreases, the threat of imitation and emulation that the older sibling feels from the younger counterpart is increased. Grote (2003) reinforces this viewpoint by further arguing that the extreme closeness of twin siblings, especially identical ones, is even more threatening, since twins often suffer from an extreme lack of differentiation.

Gender is another key factor affecting the nature of the sibling relationship (Connidis and Campbell 1995; Kang 2002; Spitze and Trent 2006). Studies have shown that of the three sibling pair types (brother-brother, sister-sister, brother-sister), sister-sister pairs seem the closest and brother-brother pairs are the most competitive, especially identical male twins (Leder 1993). Additionally, Akiyama et al. (1996) suggested that pairs of sisters constitute the most involved sibling dyads, in light of the principle of “femaleness”, according to which the more women influence and are involved in sister sibling pairs, the closer the relationship.

The argument concerning female dyads is justified by evidence indicating that women develop greater intimacy, affection and closer contact (Stewart et al. 1998). After all, according to Leder (1993), sisters are “the traditional kin keepers in our society and have a real commitment to keeping the relationship going” and are more adept in sharing their intimate feelings and expressing themselves. Brothers, on the other hand, are more antagonistic, especially in societies and cultures where men are supposed to be overly achievement-oriented and under the continuous notion of parental and societal comparison. This comparison often seems to remain and linger from home, to school, to the university, and finally to the workplace in terms of who is the best student, who makes the most money, who owns the best car, etc.

Apart from age and gender configuration, another important characteristic of the sibling structure to be taken into account in a sibling rivalry study is the number of siblings within the family, i.e. family size. Unfortunately, evidence dealing systematically with the effects of family size on the nature of sibling relationships is scant, but even so, several studies indicate that larger families experience more overt conflict (Newman 1996). This might occur for two basic reasons. Firstly, in larger families more sibling interactions take place and thus a greater and more dynamic complexity of relationships is involved, enhancing the potential for conflicts (Bowerman and Dobash 1974; Graham-Bermann et al. 1994). Secondly, in a large family, siblings compete for both tangible (property, space, and other goods) and intangible (parental attention, time, socioemotional wealth, etc.) resources. Thus, in larger families it is most likely that fewer resources are available to each child and more sibling competition is triggered over these resources (Felson 1983; Newman 1996). Therefore:

-

Research Proposition P3:

The more pronounced the differences in the characteristics among siblings, the more likely the quality of sibling relationships in adulthood will be lower in family and family business situations conceivably resulting in sibling rivalry, all else being equal.

-

Research Proposition P3a:

The shorter the age gap among siblings, the more likely the quality of sibling relationships in adulthood will be lower in family and family business situations conceivably resulting in sibling rivalry, all else being equal.

-

Research Proposition P3b:

The more siblings of male gender, the more likely the quality of sibling relationships in adulthood will be lower in family and family business situations conceivably resulting in sibling rivalry, all else being equal.

-

Research Proposition P3c:

The greater the number of siblings within the family, the more likely the quality of sibling relationships in adulthood will be lower in family and family business situations conceivably resulting in sibling rivalry, all else being equal.

-

Research Proposition P3a:

Perception of fairness

Finally, a solid reason for including a perception of fairness variable into our conceptual framework is the fact that the issue of fairness has been very closely linked to conflict over succession in family firms (Desmarais and Lerner 1994). The same holds true obviously for strictly inheritance issues as well. Yet, fairness can be determined on various grounds and underpinnings and consequently many competing interpretations may exist on what is really fair (Titus et al. 1979). Lerner (1987) suggested that the sense of fairness of an individual in a family is shaped by the perceived entitlement (“who” is entitled to “what” from “whom”) in a given situation. This perceived entitlement is dictated by four rules of fairness: (1) fairness according to need, where rewards are distributed according to the needs of the stakeholders; (2) fairness according to equity, where rewards are distributed on the basis of each stakeholder’s contributions; (3) fairness based on equality, where rewards are allocated equally among the stakeholders regardless of specific needs or contributions; and (4) fairness based on competition, where rewards are allotted to the one who prevails in a family’s competitive race, whatever that may be (Desmarais and Lerner 1994; Taylor and Norris 2000).

There are also suggestions in the literature about the implications due to the existence of the possibility of a degree of change and/or escalation among these rules of fairness (Desmarais and Lerner 1989; Taylor and Norris 2000), in the sense that the acceptance and permanence of fairness based on need for example, is associated with the closest of sibling relationships, whereas acceptance and permanence of fairness based on competition is linked to the least close sibling relationships. Furthermore, Taylor and Norris (2000) infer in their study that higher levels of sibling rivalry are predicted when the siblings in a family accept a priori different rules of fairness. Hence, it is most likely that when siblings do not agree upon a common rule of fairness regarding the family firm’s succession or even inheritance issues, in the sense that for instance one sibling believes fairness based on equality is the most appropriate rule and the other leans toward fairness based on competition, intense sibling rivalry could erupt. In light of the above:

-

Research Proposition P4:

The more divergence in the perception of fairness exists among siblings, the more likely the quality of sibling relationships in adulthood will be lower in family and family business situations conceivably resulting in sibling rivalry, all else being equal.

Discussion

Parental attitude and behavior during childhood, sibling characteristics and the congruity or incongruity of perception of fairness by the sibling family firm potential successors will be influencing indirectly the succession process, through their impacts on the quality of sibling relationships and subsequently the levels of and the intensity of sibling rivalry in family and family business situations.

The correlation between sibling rivalry and the succession outcome should be positive in the sense that the higher the levels of sibling rivalry, the higher will the prospects for a negative succession outcome for the family business. We believe that in extreme cases sibling rivalry can even lead to a complete failure of succession and even eventual dissolution of the family firm.

With respect to how parental attitudes, roles, and behaviors influence sibling relationships during childhood and how subsequently they affect sibling relationships in adulthood, we expect empirical research findings to confirm that dysfunctional attitudes and behaviors of parents during childhood, such as, stereotyping, preferential treatment and intrusion in their children’s efforts for settlement of differences, will create hostile sibling rivalries in childhood that are very likely to be carried over in adulthood and thus affect negatively adult sibling relationships in both family and family business situations.

Furthermore, with regard to how sibling characteristics such as, age gap, gender composition and number of siblings may impact sibling relationships and subsequently create sibling rivalry in adulthood in family and family business situations, we postulate that as far as the age gap is concerned, we expect research to corroborate that siblings with a greater age distance will have lower probability to experience rivalry. On the other hand, in terms of the impact of gender sibling composition on sibling rivalry, it seems that male siblings may have a higher likelihood to experience rivalry than female siblings, therefore, the greater the number of male siblings within the family, the higher the prospects for a sibling rivalry. Lastly, we expect that the number of siblings in terms of family size is also important as far as sibling rivalry is concerned, and we anticipate that the greater the number of siblings, the less cohesive and stable the relationship will be among siblings, and thus, the more opportunities for sibling rivalry will emerge.

Finally, as far as how sibling perceptions of fairness shape sibling relationships, we anticipate that the lack of homogeneity in such perceptions has a negative correlation with sibling rivalry. Put in a different way, when no common agreement exists among siblings on how fairness is or should be assessed, in other words, when different siblings perceive that fairness is or should be assessed and based on different underpinnings of need, equity, equality, or competition, then, there is a higher probability for sibling rivalry to erupt in family and family business situations.

Theoretical and practical implications

From a theoretical perspective, this paper could be considered as a theoretical and conceptual framework that will contribute to the existing literature concerning family conflicts and more particularly sibling rivalry, as a major determining factor of the succession outcome within family enterprises. This is because this paper has investigated in a more comprehensive manner than the existing business literature on the subject, various streams and fields of research that affect sibling rivalry dynamics and examined their core components in order to generate a more inclusive context of the different concepts and viewpoints from an interdisciplinary perspective into the family business succession discussion. Although conflict management is a widely analyzed research topic, conflict in terms of sibling rivalry and especially in relation to the succession outcome within family firms still lacks thorough investigation, and thus, this paper provides a good groundwork for future research in the sibling rivalry area which is currently quite limited, because there are certain perspectives of sibling rivalry that are yet to be analyzed from a non-business perspective. More specifically, key points to be taken into account are:

-

Parents must avoid any favoritism, stereotyping of their children, preferential treatment and excessive interference in offspring conflicts, since these actions and behaviors will generate bitter feelings among the children not only at present, but also bitter mindsets and sentiments that can be carried over, even at a later age and manifest themselves with disastrous results during the family firm’s succession process.

-

Raising and nurturing a team of differentiated siblings is essential because differentiating the children from each other and from the parents does not necessarily entail rivalry or isolation (Cicirelli 1985). The idea is “to foster such respect for their different qualities and interests that there is plenty of self-esteem to go around” (Kaye 1992). Consequently, not only will each child be appreciated for his/her talent and uniqueness, but also sibling rivalry will be diluted due to distinct profiles and backgrounds. In evolutionary terms, a shared gene encourages creatures containing copies of this gene to collaborate with each other and in order to eventually prosper. Since the best way to be sure that you share genes is to be related to each other, as Hamilton’s rule in evolutionary biology postulates, this degree of altruistic collaboration might be expected as being proportional to the degree of relatedness (The Economist 2013b).

-

When siblings are of the same or similar age, there is higher probability for sibling rivalry to erupt. In such cases it is important to set specific compelling succession models, in order to hinder the potential sources of conflict.

-

Likewise, when the portion of males among siblings is higher than that of females, more chances for sibling conflicts exist. It is therefore appropriate to proactively develop well-defined and crystal clear succession processes in such a way that siblings would have a hard time questioning their rationale.

-

In families with more than two children, more emphasis should be placed on the specific delegation of responsibilities, processes and rights, since there is high risk of competition among heirs or heiresses.

-

Parents within family firms have to determine a common basis and foundation of what fairness means for this family, at this specific point of time and within specific parameters, so that successors get accustomed to the exact definition of what fairness means for the family and for the family business without any room for misinterpretation.

-

Mentoring can be of great importance whenever siblings are candidates for successors. This, along with clear job descriptions, predefined job expectations, and performance reviews, will lead to a smoother succession process, based on a specific, common, agreed-upon concept of fairness.

-

Parents should instill to their children the conviction that leaving the family business because working there is not part of a successor’s dream, is not something wrong. This will make offspring more responsible, more autonomous and more eager to increase and enrich their competencies in order to succeed in other firms, and maybe, just maybe they will return to the family firm stronger, wiser, and more competent. This option will provide additional motivation for them to pursue their real dreams rather than imitate or compete with their siblings in challenging the same position within the family firm, especially that of the successor. Extreme parental altruism, in the sense that parents will lay down their own personal interests and occasionally their own lives in extreme situations for the sake of their children might make evolutionary sense in terms of preserving your biological legacy (The Economist 2012), but makes no business sense in terms of preserving the family business legacy into the hands of competent and self-confident offspring. This is especially true since across a single generation some children of especially rich and doting seemingly altruistic parents are bound to suffer random episodes of bad luck that will render them with little resilience when facing the challenges of family business as successors in spite of the fact that 70–80 % of economic advantage seems to be transmitted from generation to generation (The Economist 2013a).

From a practical point of view, the paper’s conceptual and theoretical framework should be of particular interest to members of family businesses, and should serve as a ground analysis of sibling rivalry dynamics and the related drivers of a successful succession Therefore, it could serve as a blueprint for identifying reasons why sibling rivalries occur and in the search of effective ways to hopefully avoid them, or at least render them less harmful for the family and the family firm. Last but not least, the results of our analysis constitute a practical pathway for family business consultants when they encounter and come across sibling rivalry or similar situations.

Concluding remarks

Succession planning has always been an area and a time of turmoil in family enterprises. Relationship among heirs and its impact on the succession outcome has been a highly debated topic, due to its multidimensional nature. The concept of sibling rivalry as delineated in this study results in identifying the fundamentals of the relationships among siblings in childhood and later on in adulthood in family and family business situations and especially during the succession process. Given the enormously critical implications of sibling rivalry during the succession process, incumbent parent/owners and/or managers of family firms should be sensitized on the origins of this sibling rivalry as well as the reasons that steered the family into these potentially explosive circumstances. Since sibling rivalry can be attributed to the dynamics of the parental roles, the sibling characteristics and the perceived sense of fairness, interested parties can trace such potential sources of conflict beforehand, in order to avoid poor succession planning in terms of succession effectiveness and family and stakeholder satisfaction with the succession process. Consequently, the conceptual and theoretical framework outlined in this paper is of interest not only to family members who are considered succession candidates, but also has an external focus in the sense that it provides important insights to family members that are not candidates for succession or even to non-family member stakeholders who will impacted by the negative implications of a serious sibling rivalry in the family firm, such as non-family employees, customers, suppliers, or lenders.

One possible limitation of the conceptual framework advanced in this paper was that the scope of the current paper was to analyze the impact of the aforementioned antecedent factors, namely parental role, characteristics of the siblings and perceived fairness, on sibling rivalry and the succession process. It, therefore, intentionally focused on these three elements and evaluated their impact in a singular and autonomous approach, and attempts to trace and measure their influence by isolating them in order to elicit clear and unbiased conclusions. This approach however, means that the theoretical framework does not probe the potentially cumulative or combined effect of all or some of the antecedent factors cited here on sibling rivalry and indirectly on the family firm succession process, and does not encompass other additional factors that could possibly affect sibling rivalry and the succession outcome, such as the personality traits of the siblings, the family’s ethnicity, culture, and religious beliefs for example, which could be equally influential in producing or averting sibling rivalry.

Finally, the conceptual framework presented here does not account for any specific timing or situational dimensions. Therefore, it is difficult to predict how the effects of sibling rivalry will vary if succession occurs at an early or a late stage of the siblings’ lifetime (for example, when the siblings are younger or older), or how sibling rivalry will play out in the case where there is only one incumbent patriarch or matriarch rather than an incumbent parental couple or even a non-family member incumbent. Similarly, it is difficult to foretell how the existence of only two versus three or more siblings will intensify sibling rivalry or moderate it uniting the siblings against a serious non-family member candidacy for the succession of the family firm. Likewise, it is uncertain how sibling rivalry will play out when not all siblings are currently employed in the family firm or no one is. Finally, an abrupt and sudden unplanned succession due to illness or unexpected death of the patriarch or matriarch incumbent may intensify or moderate sibling rivalry during these extraordinary circumstances compared to a situation where the succession has been planned, predictable, and widely communicated beforehand.

All these issues and timing and the related situational possibilities can become the focus of empirical research that could be undertaken to examine all these variations in sibling dynamics as they unfold over different phases of the succession process. Furthermore, it would be really interesting to investigate some additional variables or factors that may affect the quality of sibling ties. From the family side, such variables could be the personality traits of individual siblings, their education or professional background, as well as the family ethnicity, culture and religion. Additionally, from the theoretical and empirical perspective, some additional issues could be examined, such as, whether a formal succession plan does or does not exist, as well as the particular structure of the incumbent management and governance of the family firm, (such as, the number of key family and non-family managers; whether the incumbent is a single parent, a parental couple, a non-family member, or even another sibling; whether parents are actively involved in the management of the firm and remain so even after their retirement, something that could be more likely to exacerbate or diminish sibling rivalry). Finally, the impact of exogenous forces on sibling rivalry are worthy of consideration and empirical investigation, such as economic or competitive pressures for example, which may or may not bring siblings closer in their efforts to combat critical external threats.

References

Akiyama, H., Elliott, K., & Antonucci, T. C. (1996). Same-sex and cross-sex relationships. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 51B(6), 374–382.

American Family Business Survey. (1997). The Arthur Andersen/Mass Mutual American family business survey. http://www.arthurandersen.com/CFB.97surv.asp.

Barnes, L. B. (1988). Incongruent hierarchies: daughters and younger sons in company CEOs. Family Business Review, 1(1), 9–21.

Beckhard, R., & Dyer, W., Jr. (1983a). Managing change in family firm–issues and strategies. Sloan Management Review, 24(3), 59–65.

Beckhard, R., & Dyer, W. (1983b). Managing continuity in the family-owned business. Organizational Dynamics, 12(1), 5–12.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gómez-Mejía, L. R., & Larraza-Kintana, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: do family-controlled firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(1), 82–113.

Bird, B., Welsch, H., Astrachan, J. H., & Pistrui, D. (2002). Family business research: the evolution of an academic field. Family Business Review, 15(4), 337–350.

Birley, S., Ng, D., & Godfrey, A. (1999). The family and the business. Long Range Planning, 32(6), 598–608.

Boles, J. S. (1996). Influences of work-family conflict on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and quitting intentions among business owners: the case of family-operated businesses. Family Business Review, 9(1), 61–74.

Bowerman, C. E., & Dobash, R. M. (1974). Structural variations in inter-sibling affect. Journal of Marriage and Family, 36(1), 48–54.

Breton-Miller, I. L., Miller, D., & Steier, L. P. (2004). Toward an integrative model of effective FOB succession. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 305–328.

Cabrera-Suarez, K., De Saa-Perez, P., & Garcia-Almeida, D. (2001). The succession process from a resource and knowledge based view of the family firm. Family Business Review, 14(1), 37–46.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(4), 19–40.

Cicirelli, V. G. (1985). Sibling relationships throughout the life cycle. In L. L’Abate (Ed.), The handbook of family psychology and therapy (Vol. 1). Homewood: Dorsey Press.

Cicirelli, V. G. (1994). Sibling relationships in cross-cultural perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56(1), 7–20.

Connidis, I. A., & Campbell, L. D. (1995). Closeness, confiding, and contact among siblings in middle and late adulthood. Journal of Family Issues, 16(6), 722–745.

Cruz, C., Gómez-Mejía, L. R., & Becerra, M. (2010). Perceptions of benevolence and the design of agency contracts: CEO-TMT relationships in family firms. Academy of Management Journal, 53(1), 69–89.

Davis, S. M. (1968). Entrepreneurial succession. Administrative Science Quarterly, 13(3), 402–416.

Davis, P. S., & Harveston, P. D. (1998). The influence of family on the family business succession process: a multigenerational perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22(3), 31–49.

Davis, P. S., & Harveston, P. D. (2001). The phenomenon of substantive conflict in the family firm: a cross-generational study. Journal of Small Business Management, 39(1), 14–30.

Davis, J. A., & Tagiuri, R. (1985). Bivalent attitudes of the family firm. Paper presented at the Western Academy of Management Meeting, March 29.

De Massis, A., Chua, J. H., & Chrisman, J. J. (2008). Factors preventing intra-family succession. Family Business Review, 21(2), 187–199.

Desmarais, S., & Lerner, M. J. (1989). A new look at equity and outcomes as determinants of satisfaction in close personal relationships. Social Justice Research, 3, 105–119.

Desmarais, S., & Lerner, M. J. (1994). Entitlements in close relationships: a justice-motive analysis. In M. J. Lemer & G. Mikula (Eds.), Entitlement and the affectional bond: justice in close relationships. New York: Plenum.

Dyer, W. G., Jr., & Sánchez, M. (1998). Current state of family business theory and practice as reflected in Family Business Review 1998–1997. Family Business Review, 11(4), 287–296.

Felson, R. B. (1983). Aggression and violence between siblings. Social Psychology Quarterly, 46(4), 271–285.

Friedman, S. D. (1991). Sibling relationships and intergenerational succession in family firms. Family Business Review, 4(3), 3–20.

Goetting, A. (1986). The developmental tasks of siblingship over the life cycle. Journal of Marriage and Family, 48(4), 703–714.

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J. L., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106–137.

Graham-Bermann, S. A., Cutler, S. E., Litzenberger, B. W., & Schwartz, W. E. (1994). Perceived conflict and violence in childhood sibling relationships and later emotional adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 8, 85–97.

Griffeth, R. W., Allen, D. G., & Barrett, R. (2006). Integration of family-owned business succession with turnover and life cycle models: development of a successor retention process model. Human Resource Management Review, 16, 490–507.

Grote, J. (2003). Conflicting generations: a new theory of family business rivalry. Family Business Review, 16(2), 113–124.

Handler, W. (1994). Succession in family business: a review of the research. Family Business Review, 7(2), 133–158.

Jayson, S. (2012). Parents play favorites when helping adult kids out. USA Today, May 3.

Kang, H. (2002). The nature of adult sibling relationship—literature review. Paper prepared by Children and Family Research Center, School of Social Work, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Kaye, K. (1991). Penetrating the cycle of sustained conflict. Family Business Review, 4(1), 21–44.

Kaye, K. (1992). The kid brother. Family Business Review, 5(3), 237–256.

Lamb, M. E., & Sutton-Smith, B. (1982). Sibling relationships: their nature and significance across the lifespan. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lambrecht, J., & Donckel, R. (2006). Towards a business family dynasty: a lifelong, continuing process. In P. Poutziouris, K. X. Smyrnios, & S. B. Klein (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Family Business, (pp. 388–401). Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Leder, J. M. (1993). Adult sibling rivalry. Psychology Today, 26, 56–58.

Lerner, M. J. (1987). Integrating societal and psychological rules of entitlement: the basic task of each social actor and fundamental problem for the social sciences. Social Justice Research, 1(1), 107–125.

Miller, D., Steier, L., & Breton-Miller, I. L. (2003). Lost in time: intergenerational succession, change, and failure in family business. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 513–531.

Morris, M. H., Williams, R. O., Allen, J. A., & Avila, R. A. (1997). Correlates of success in family business transitions. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(5), 385–401.

Newman, J. (1996). The more the merrier? Effects of family size and sibling spacing on sibling relationships. Child: Care, Health and Development, 22(5), 285–302.

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Nelson, L. J., & Carroll, J. S. (2012). Affording emerging adulthood: parental financial assistance of their college-aged children. Journal of Adult Development, 19(1), 50–58.

Pyromalis, V. D., & Vozikis, G. S. (2009). Mapping the successful succession process in family firms: evidence from Greece. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 5(4), 439–460.

Rutherford, M. W., Kuratko, D. F., & Holt, D. T. (2008). Examining the link between “familiness” and performance: can the F-PEC untangle the family business theory jungle. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32, 1089–1109.

Sharma, P., Hoy, F., Astrachan, J. H., & Koiranen, M. (2007). The practice-driven evolution of family business education. Journal of Business Research, 60, 1012–1021.

Shepherd, D. A., & Zacharakis, A. (2000). Structuring family business succession: an analysis of the future leader’s decision making. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 24, 25–39. Summer.

Sonnenfeld, J. (1988). The hero’s farewell: what happens when CEOs retire. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

Sorenson, R. L. (1999). Conflict management strategies used by successful family businesses. Family Business Review, 12(4), 325–339.

Spitze, G., & Trent, K. (2006). Gender differences in adult sibling relations in two-child families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 977–992.

Stewart, R. B., Verbrugge, K. M., & Beilfuss, M. C. (1998). Sibling relationships in early adulthood: a typology. Personal Relationships, 5, 59–74.

Stocker, C. M., Lanthier, R. P., & Furman, W. (1997). Sibling relationships in early adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 11(2), 210–221.

Taylor, J. E., & Norris, J. E. (2000). Sibling relationships, fairness, and conflict over transfer of the farm. Family Relations, 49(3), 277–283.

The Economist. (2012). Time’s arrows. 405(8810), 84. November 10.

The Economist. (2013a). Nomencracy. 406(8822), 75. February 9.

The Economist. (2013b). Darwin’s retriever. 406(8827), 85. March 16.

Titus, S. L., Rosenblatt, P. C., & Anderson, R. M. (1979). Family conflict over inheritance of property. The Family Coordinator, 28(3), 337–346.

Tonti, M. (1988). Relationships among adult siblings who care for their aged parents. In M. D. Kahn & K. G. Lewis (Eds.), Siblings in therapy: life span and clinical issues (pp. 4 17–434). New York: Norton.

Zahra, S., & Sharma, P. (2004). Family business research: a strategic reflection. Family Business Review, 17(4), 331–46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Avloniti, A., Iatridou, A., Kaloupsis, I. et al. Sibling rivalry: implications for the family business succession process. Int Entrep Manag J 10, 661–678 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0271-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0271-6