Abstract

In the last years, the business creation and management literature has paid increasing attention to the entrepreneurship that occurs within organizations. Most empirical studies show a positive relationship between corporate entrepreneurship and performance. The objective of this article is to identify which internal and external factors condition corporate entrepreneurship. The study uses two different theoretical perspectives: Resource-Based Theory (for internal factors) and Institutional Economics (for external or environmental factors). Both theories have been widely used in the strategic management and entrepreneurship literature, however, very few studies in the corporate entrepreneurship field are grounded on them together. The research applies negative binomial regression and uses data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) for the period 2004–2008. Overall the sample has 339.071 observations and it provides information for 9 different European countries (Greece, Spain, Italy, Ireland, the Netherlands, France, the United Kingdom, Denmark and Finland). Results reinforce the importance of internal factors (knowledge, personal networks and being able to identify business opportunities) compared to external (having fear of failure, media impact and the number of procedures to create a company). Contributions of the study are both theoretical and practical. On the one hand, it contributes to the development of the literature in the corporate entrepreneurship field. On the other hand, it provides useful insights for those companies that are interested in entrepreneurship within the organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent decades, researchers have paid increasing attention to the role of entrepreneurship for productivity, innovation, employment and economic and social development (Audretsch 2012; Wennekers et al. 2005). Most of the studies agree that the creation of new companies stimulates economic growth. Thus, both researchers and policy makers consider that fostering entrepreneurship means fostering the development of economies (Anderson et al. 2012; Fritsch 2008; Grilo and Thurik 2005). In addition, the literature in the area of business creation and management has paid increasing attention to the entrepreneurship that occurs within organizations (Lumpkin and Dess 1996).Footnote 1 Corporate entrepreneurship has been considered to be an important element in organizational and economic development, due to its beneficial effects on the revitalization and performance of firms (Antoncic and Hisrich 2001; Chang et al. 2011; Guth and Ginsberg 1990; Idris and Tey 2011; Zahra 1991). Therefore corporate entrepreneurship has increasingly been recognized as a legitimate path to high levels of organizational performance (Hornsby et al. 2009).

The objective of this article is to identify which internal and external (environmental) factors condition corporate entrepreneurship. Previous research has tried to identify which organizational or environmental factors influence corporate venturing (Gomez-Haro et al. 2011; Yang and Li 2011; Pinchot 1985; Ribeiro-Soriano and Urbano 2009). However, our research uses Resource-Based Theory (RBT) and Institutional Economics (IE) as theoretical frameworks. Despite the fact that both theories have been widely used in the strategic management and entrepreneurship literature, very few studies in the corporate entrepreneurship field are grounded on them together (Castrogiovanni et al. 2011). In fact, most of the studies in this area do not use a specific theoretical framework. Besides this, we analyse the differences between two groups of European countries (high income per capita countries and middle income per capita countries). In this sense, previous research has had a primarily American basis and cross-country (or cross-cultural) comparisons of the corporate entrepreneurship model have been minimal (Antoncic 2007). Using negative binomial regression and data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) for the 2004–2008 period, our results highlight the importance of internal factors compared to external ones. In addition, there are also differences between countries, because the role of the environment is weaker in richer countries. The implications of the study are both conceptual and practical. On the one hand, it contributes to the development of the corporate entrepreneurship literature using an integrative model that considers both RBT and IE. Specifically, results contribute to the discussion of whether internal or environmental factors are more important for corporate entrepreneurship. On the other hand, it provides useful insights for those companies that are interested in fostering corporate entrepreneurship.

After this brief introduction, the paper is structured as follows. The conceptual part of the study is presented in “Corporate entrepreneurship, resource-based theory and institutional economics”. In “Methodology” the description of variables, data analysis and the model are detailed. “Results and discussion” present the main findings of the work and finally, the conclusions and future research lines are discussed in “Conclusions” section.

Corporate entrepreneurship, resource-based theory and institutional economics

Scholars and practitioners have shown interest in the corporate entrepreneurship concept since the beginning of the 1980s, due to its beneficial effect on the revitalization and performance of firms (Burgelman 1985; Guth and Ginsberg 1990; Pinchot 1985; Zahra 1991). Corporate entrepreneurship has been considered as a method to offer an organization a strategic option to refine its business concept, to meet changing customer needs and expectations, and to enhance its competitive position (Burgelman 1985; Guth and Ginsberg 1990; Pinchot 1985; Zahra 1991).

The concept of corporate entrepreneurship may appear straightforward, but researchers use different definitions and names for the entrepreneurship phenomenon within existing organizations (Menzel et al. 2007). Terms such as intrapreneurship (used by, amongst others, Pinchot 1985), corporate entrepreneurship (used by, amongst others, Burgelman 1985), and corporate venturing (MacMillan 1986) have all been used to describe the same phenomenon. One of the most broad and widely accepted definitions for the corporate entrepreneurship is “entrepreneurship within an existing organization” (Antoncic and Hisrich 2001). Corporate entrepreneurship includes entrepreneurial behaviour and orientation in existing organizations, for example, when the firm acts entrepreneurially in pursuing new opportunities; in contrast, a non-intrapreneurial firm would be more concerned with the management of the existing enterprise (Antoncic and Hisrich 2003) and would make decisions predominantly on the basis of the currently controlled resources (Stevenson and Jarillo 1990). Miller (1983) defined corporate entrepreneurship as the activities that an organization undertakes to enhance its product-innovation, risk-taking, and proactive response to environmental forces. Antoncic (2007) classifies intrapreneurship into the following four dimensions: (1) new business venturing (or corporate venturing) (Stopford and Baden-Fuller 1994); (2) innovativeness (Covin and Slevin 1991; Knight 1997); (3) self-renewal (Guth and Ginsberg 1990; Stopford and Baden-Fuller 1994; Zahra 1991); and (4) proactiveness (Covin and Slevin 1991; Knight 1997; Stopford and Baden-Fuller 1994). That is, firms may engage in internal innovation in order to introduce new products or services or to enter new markets; they may rejuvenate themselves by innovating and altering internal processes, structures, or capabilities; they may identify and adopt new ways of competing in existing markets; or they may proactively create entirely new product markets that other companies have not recognized or actively exploited (Covin and Miles 1999).

Resource-based theory

According to RBT, firms are bundles of tangible and intangible resources and capabilities (Wernerfelt 1984). Unique resource endowments serve to explain differences in firms’ performances, so valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable resources are sources of a firm’s competitive advantage (Barney 1991). In the last two decades, the diffusion of RBT into strategic management and related disciplines has been both dramatic and controversial, and has involved considerable theoretical development and empirical testing (Barney et al. 2001). In the traditional entrepreneurship literature there are many empirical studies grounded on RBT (Hult and Ketchen 2001; Urbano and Yordanova 2008; Westhead et al. 2001, among others), but in the corporate entrepreneurship literature most studies do not use a specific theoretical framework (see Hornsby et al. 2002, among others). Yet in recent years, increasing attention has been focused on the combination and management of resources which enable the firm to pursue new business opportunities and develop innovative actions (Castrogiovanni et al. 2011), and which lead to more effective processes (Meyskens et al. 2010). These studies are consistent with the RBT approach which emphasizes the importance of a firm’s resources as the drivers of growth (Penrose 1959), high profits (Wernerfelt 1984) and competitive advantage (Barney 1991).

Institutional economics

RBT has been one of the key theories in the entrepreneurship and corporate entrepreneurship fields, as access to resources is central to the success of a new venture or project (Bhide 2000). However, it has become increasingly clear that issues such as culture, legal environment, tradition and history in an industry, and economic incentives can all impact on an industry and, in turn, on entrepreneurial success (Bruton et al. 2010).

Institutional theory proposes that organizations adopt structures, processes, programmes, policies and/or procedures because of the pressure that coexisting institutions exert on them (Kostova and Roth 2002). Institutions are the rules of the game in a society, and function as constraints and opportunities, shaping human interaction. Institutions can be formal, such as political and economic rules and contracts, or informal, such as codes of conduct, conventions, attitudes, values and norms of behaviour (North 1990, 2005). The application of IE is especially helpful to entrepreneurial research. In the entrepreneurship context, institutions represent the set of rules that articulate and organize the economic, social and political interactions between individuals and social groups, with consequences for business activity and economic development (Bruton et al. 2010). Despite the fact that many authors have used this institutional approach in the field of entrepreneurship (Bruton et al. 2010; Coduras et al. 2008; Guerrero and Urbano 2012; Liñán et al. 2011a, b; Thornton et al. 2011; Welter and Smallbone 2011), very few papers on the corporate entrepreneurship issue are grounded on this theory (Gomez-Haro et al. 2011).

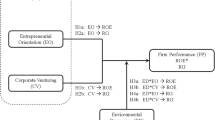

Using both RBT and IE to study internal and external factors, the research presents two different sets of hypotheses. The first three hypotheses gauge information about the company’s resources and capabilities (RBT), while hypotheses 4 to 6 have to do with institutional factors (IE).

Knowledge as a resource

Individuals with more or higher-quality human capital should be better at perceiving profitable opportunities, once engaged in the entrepreneurial process, and such individuals should also have superior ability to exploit opportunities successfully (Davidsson and Honig 2003; Keen and Etemad 2012; Renko et al. 2012). Formal education is one of the main components of human capital, as education may assist in the accumulation of explicit knowledge that may provide skills useful to entrepreneurs (BarNir 2012; Lepak and Snell 1999). More innovative organizations are managed by well-educated teams, whose functional areas of expertise are diverse. According to recent empirical studies on different cultures around the world, investments made in improve human capital and education seems to provide an increase in the organizational innovativeness (Alpkan et al. 2010). Similarly, Chen et al. (1998) identified a correlation between the level of entrepreneurial intention and the number of management courses taken by students. In fact, Dess et al. (2003) consider that a high level of human capital can create opportunities for knowledge creationand exploitation within corporate entrepreneurship activities.

If a company has well-qualified employees, the implementation and development of intrapreneurial projects will become easier, and, the chances of success will increase (Liñán et al. 2011a, b). In fact, academic entrepreneurs are likely to employ more people than their non-academic counterparts (Parker 2011). In addition, it is considered to be necessary for a company to offer specific training to its workers and to hand down skills from one generation of workers to the next in order to implement and develop innovative projects (Hayton and Kelley 2006). Therefore, we pose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 1:

It is more likely that individuals become corporate entrepreneurs when they have some high education experience or more.

Personal networks as a capability

Research emphasizes the importance of networks, and the social capital inherent in them, for the creation of new ventures (Aldrich and Zimmer 1986). However, despite the interest and research on the concept, it is still in an emerging phase, comprising different uses and connotations from various scholarly perspectives (Adler and Kwon 2000). Networks are considered the opportunity structures through which entrepreneurs obtain information, resources, and social support to identify and exploit opportunities (Aldrich and Zimmer 1986; Mousa and Wales 2012). Similarly, Burt (1992) believes networks are an asset that resides in an individual’s relationships and consists of the goodwill flowing from friends, colleagues, and other general contacts.

In addition, networks have been shown to act as providers of psychological and practical support (Johannisson 1986), access to opportunities (Burt 1992), and a host of other resources (such as finance or information) (Ostgaard and Birley 1996; Klyver et al. 2008). It is difficult to see how venture creation is possible without access to an effective set of network relationships (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). Social capital may also help to understand how resources are integrated and recombined in firms with dynamic capabilities. Finally, in mobilizing resources for one purpose, social capital also acts to release other resources (Blyler and Coff 2003). Ultimately, we present the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 2:

It is more likely that individuals become corporate entrepreneurs when they know other entrepreneurs.

Opportunity recognition as a capability

The opportunity recognition process has traditionally played a key role in research in the entrepreneurship field (Gaglio and Katz 2001; Zortea-Johnston et al. 2012). Previous works on the topic consider that discovering entrepreneurial opportunities constitutes an essential entrepreneurial skill (Ardichvili et al. 2003) and a source of competitive advantage (Alvarez and Busenitz 2001).

Being able to detect business opportunities allows one to develop new products, services, markets and competitive advantages. To take advantage of opportunities, firms must develop the ability to carry out a range of different tasks associated with intrapreneurship (Hostager et al. 1998). These tasks include being able to identify opportunities and ideas for new products or services, and turning these ideas into profitable products and services (Pinchot 1985). Hence, one of the most important points in research on opportunity recognition has been why certain individuals discover opportunities that others do not (Kirzner 1997; Shane 2000; Shane and Venkataraman 2000). Previous researchers have argued that entrepreneurial opportunities exist primarily because different members of society have different beliefs about the relative value (the potential to be transformed into a different state) of resources (Kirzner 1997). Assuming these different beliefs, all opportunities are not obvious to everyone all of the time. Based on these explanations, the following hypothesis is posed:

-

Hypothesis 3:

It is more likely that individuals become corporate entrepreneurs when they are able to identify business opportunities.

Fear of failure as an informal factor

The relationship between entrepreneurship and fear of failure has received some attention from scholars who have considered the relationship between entrepreneurial decisions and risk aversion (Kihlstrom and Laffont 1979). According to the literature, the perceived possibility of failure determines an individual’s decision to start a business, and the fear of failure has a negative effect on intrapreneurship. Since most individuals are risk averse, and since the perceived fear of failure (rather than the objective likelihood of failure) is an important component of the risk attached to starting a new business, a reduced perception of the likelihood of failure should increase the probability that a company will start a new business (Arenius and Minniti 2005; Boermans 2010). The willingness of individual intrapreneurs to take risks, and the risk permissiveness of top managers, allowing and encouraging the corporate entrepreneurs to be more innovative, require a tolerant understanding of managers towards those corporate entrepreneurs whose projects fail, especially in turbulent markets (Alpkan et al. 2010; Stopford and Baden-Fuller 1994). Therefore, management support is an important issue to take into account. This support considers many forms, including championing innovative ideas, providing necessary resources or expertise, or institutionalizing entrepreneurial activity within a firm’s systems and processes (Hornsby et al. 2002). Finally, this risk aversion behaviour cannot be changed by exogenous interventions such as government programmes, but can be modified through cultural factors that mould attitudes, perceptions, and risk profiles (Arenius and Minniti 2005). Hence, we pose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 4:

It is less likely that individuals become corporate entrepreneurs when they have a fear of failure when starting a business.

Media impact as an informal factor

Business news coverage is of particular importance to organizations attempting to manage issues, because much of what consumers and other external stakeholders learn about companies and the issues that surround them comes from the news media (Carroll and McCombs 2003). Stories reported by the media play a critical role in the processes that enable new businesses to emerge. Stories that are told by or about entrepreneurs define a new venture in ways that can lead to favourable interpretations of the wealth-creating possibilities of the venture. These stories are helpful to potential entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, and other institutional actors (such as investment banks, foundations, innovative organizations, etc.). Since many entrepreneurial ventures are unknown to external audiences, the creation of an appealing and coherent story may be one of the most crucial assets for a nascent enterprise (Lounsbury and Glynn 2001). The media plays an important role in transmitting these stories, and journalists are seen as authoritative sources of information (Deephouse 2000), thereby performing the role of institutional intermediaries (Pollock and Rindova 2003) and critics. As a result, media coverage sets the agenda for public discourse (Carroll and McCombs 2003), and affects the accumulation of reputation (Rindova et al. 2007). Ultimately, we pose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 5:

It is more likely that individuals become corporate entrepreneurs when the media often report stories about successful new businesses.

Procedures as a formal factor

One of the main regulations that can be taken by SME and Entrepreneurship policy makers that seek to increase rates of new firm formation is to enable the starting of a business to take place as quickly and cheaply as possible (Van Stel et al. 2007). Entrepreneurs inside companies may be discouraged from starting a business if they have to follow many rules and procedures (Begley et al. 2005; Huarng and Yu 2011). In fact, the literature agrees that factors such as the number of procedures and the time and cost involved in starting a business have a negative effect on entrepreneurship. A heavier regulation of entry is generally associated with greater corruption and a larger unofficial economy. Also, entry is regulated more heavily by less democratic governments, and this regulation does not seem to yield visible social benefits (Djankov et al. 2002; Tanas and Audretsch 2011). That is why some governments and institutions focus attention upon lowering the entry “barriers” to the formation of new firms; such “barriers” include the length of time taken to start a business, the number and cost of any permits or licences required and any minimum capital requirements for a new firm (Van Stel et al. 2007). Overall, inefficient government regulation in the economy may be perceived negatively, especially by those interested in starting new businesses and innovative projects (Gnyawali and Fogel 1994). Hence, the following hypothesis is posed:

-

Hypothesis 6:

It is less likely that individuals become corporate entrepreneurs when they have to follow many procedures to create a company.

Methodology

The study uses a database created by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM). This database contains information for the 2004–2008 period and includes data from the following European countries: Greece, Spain, Italy, Ireland, the Netherlands, France, the United Kingdom, Denmark and Finland. Overall the sample has a total of 339,071 observations. In addition, the research complements the GEM data with data from the Doing Business project. The Doing Business project provides objective measures of business regulations and their enforcement across 183 economies. It was launched in 2002, and looks at domestic small and medium-sized companies, measuring the regulations applying to them through their life cycles. The fundamental premise of Doing Business is that economic activity requires good rules; thus, this database is an adequate proxy for formal institutions.

Description of variables

Dependent variable

The binary variable “corporate entrepreneurship activity” is used as the dependent variable, and is a measure of individuals who, alone or with others, are currently trying to start a new business or a new venture for their employer as part of their normal work. Other studies in the entrepreneurship field have used similar binary dependent variables from a GEM database (Arenius and Kovalainen 2006; Arenius and Minniti 2005; Minniti and Nardone 2007).

Independent variables

Two vectors of independent variables are considered in this study: resources and capabilities, and institutional factors. Each vector is measured by three different variables (see Table 1). These variables have already been used in other studies: knowledge (Aidis et al. 2008; Arenius and Kovalainen 2006; Arenius and Minniti 2005); personal networks (Alvarez and Urbano 2011; Arenius and Kovalainen 2006; Arenius and Minniti 2005); opportunity recognition (Arenius and De Clercq 2005; Arenius and Kovalainen 2006; Arenius and Minniti 2005); fear of failure (Arenius and Minniti 2005; Koellinger and Minniti 2006; Koellinger 2008); media impact (Tominic and Rebernik 2007); procedures (Alvarez and Urbano 2011; Djankov et al. 2002; Van Stel et al. 2007).

Control variables

Other factors may also influence entrepreneurial activity. Recent research has shown the importance of socio-demographic factors (Arenius and Minniti 2005; Langowitz and Minniti 2007), and the economic sector, in explaining entrepreneurial behaviour (Wennekers et al. 2005). Thus we have included two different control variables, to ensure that the results were not unjustifiably influenced by such factors. In each model, we controlled the individuals’ socio-demographic characteristics (gender) and the economic sector.

-

Gender. Previous research has indicated that women’s participation rates in entrepreneurship are significantly lower than men’s rates (Arenius and Minniti 2005; Langowitz and Minniti 2007), and that men are more likely to start a business than women (Blanchflower 2004). A binary variable for gender is included in this study to test for the significance of gender effects.

-

Country per capita income. Some authors identify a differing effect depending on the economic sector (Burgers et al. 2009). We therefore control for four different economic sectors (extractive, transforming, business service, consumer oriented).

Table 1 shows the definition of the variables used in this research.

Data analysis and model

We develop a static cross-sectional analysis and estimate the regressions using country random effects. In addition, since our dependent variable is binary (see Table 1) and clearly biased (only 2 % corporate entrepreneurs, see Table 2) we use negative binomial regression (Greene 2008). This method has been extensively used in other studies in the business economics literature (Owen-Smith and Powell 2004; Saxton and Benson 2005). Overall, we propose the following model:

Where:

- Z1it :

-

collects information related to resources and capabilities

- Z2it :

-

collects information related to institutions (formal and informal)

- X1it :

-

collects the effect of the control variables

- μi :

-

is the random effect; and

- eit :

-

is the random disturbance.

Results and discussion

Table 2 provides means, standard deviations, and pairwise correlation coefficients for the variables we studied; Table 3 provides the results of the negative binomial regressions.

The Table 2 correlations show that some variables may be highly correlated. Thus, we also conducted a multi-collinearity diagnostic test (examining the variance inflation factors–VIFs–of all variables in the analysis), and we found that multi-collinearity is not likely to be a problem for this dataset. Also, to address the possibility of heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation among observations pertaining to the same country, robust standard errors, clustered by country, were estimated (White 1980). In Table 3, Model 1 presents the results for all the countries in the sample, and Model 2 includes information for those countries with a smaller gross domestic product per capita (Greece, Spain, Italy and Ireland). Finally, Model 3 provides information for those countries with a higher income per capita (the Netherlands, France, the United Kingdom, Denmark and Finland).

Hypotheses 1, 2 and 3 have to do with companies’ resources and capabilities. The results show that we cannot reject any of them, as all of them are significant at least at the 95 % level and with the expected sign. In addition, there are no significant differences between the countries with a high income per capita and those with a lower income per capita. Therefore, education level, knowing other entrepreneurs and being able to detect business opportunities increase the probability of corporate entrepreneurship. Education plays a role in the development of corporate entrepreneurship activities because it assists in the accumulation of knowledge (Davidsson and Honig 2003), so it can become a key source for promoting corporate entrepreneurship (Chandler et al. 2005). Similarly, personal networks can be seen as the structures through which corporate entrepreneurs obtain information, resources, and social support to identify and exploit opportunities (Aldrich and Zimmer 1986). Finally, being able to identify business opportunities also appears as a fundamental requirement for intrapreneurial behaviour (Stevenson and Jarillo 1990). The coefficients for resources and capabilities are high, indicating that education level, personal networks and being able to identify business opportunities in the short term increase the probability of corporate entrepreneurship. In this sense, personal networks particularly increase the probability of corporate entrepreneurship.

On the other hand, hypotheses 4, 5 and 6 regarding institutional factors are rejected. Models 1, 2 and 3 show that none of them are significant. Therefore, according to the results, institutional factors (both formal and informal) have a non-significant impact on corporate entrepreneurship. This means that the relevance of the environment in developing corporate entrepreneurship activities is limited (especially if we compare this to the effect of internal factors). In addition, it is remarkable that there are few differences between countries in terms of institutions, but these differences are significant.

Regarding control variables, gender appears as a non-significant variable, indicating that there are no relevant differences in the probability that men or women become corporate entrepreneurs. In the case of the control variable “sector”, the study uses the variable’s last category (“consumer oriented”) as a reference. Results show that the economic sector where the company operates may affect the existence of corporate entrepreneurship (Burgers et al. 2009). For example, in model 1 the fact of being in the extractive sector instead of the consumer oriented sector reduces significantly the probability of corporate entrepreneurship.

Overall, the results contribute to the literature that examines the antecedents of corporate entrepreneurship (Zahra 1991). The fact that the external environment does not appear as a significant issue for corporate entrepreneurship does not mean that it is not important. In fact, other studies such as Antoncic and Hisrich (2001), Gomez-Haro et al. (2011) or Zahra (1991) (among others) show the influence that external factors may have on an organization’s entrepreneurial activities. However, measuring internal and environmental factors together makes our results coincide with those studies that suggest that internal organizational factors play a more important role in encouraging corporate entrepreneurship than environmental factors (Covin and Slevin 1991; Hornsby et al. 2002). Environmental factors could influence corporate entrepreneurship but its effects are mitigated by the need of the company to achieve some economic results (in terms of reaching a certain level of revenues, profits or sales, for example). External factors appear as an exogenous variable, as a difficulty, challenge or as an advantage the company need to take into account when developing corporate entrepreneurship activities. On the other hand, having the appropriate internal resources or capabilities is a necessary condition the company controls. According to this, organizational support appears as one of the most fundamental issues for the development of intrapreneurial activities (Alpkan et al. 2010). This could be interpreted to suggest that potential corporate entrepreneurs might not express any interest in entrepreneurship nor seek directly any kind of start-up opportunity unless and until their work colleagues or managers present them with a suitable opportunity (Parker 2011). In any case, the outcome of the study also proposes some differences between corporate entrepreneurship and the traditional approach to entrepreneurship, as most studies in this area show the importance of institutional factors for entrepreneurship (Bruton et al. 2010).

Conclusions

Using GEM data for 9 different European countries for the period 2004–2008 and applying negative binomial regression, this research identified which factors, both internal and external, affect corporate entrepreneurship. The results show that internal factors (resources and capabilities factors) play a more important role than external factors (formal and informal institutions). In other words, education level, knowing other entrepreneurs and being able to identify business opportunities positively affect corporate entrepreneurship. On the other hand, environmental factors, such as a fear of failure, the effect of the media and the number of days required to start a business, are not significant factors.

The article has both theoretical and practical implications. From a theoretical perspective, this study takes forward the application of RBT and IE in the analysis of corporate entrepreneurship. There are very few studies which use this double theoretical approach to measure corporate entrepreneurship empirically. In addition, the study contributes to the discussion of whether internal or environmental factors are more important for corporate entrepreneurship. Moreover, it contributes to an understanding of the key internal factors for promoting corporate entrepreneurship (Battistella et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2012; Zahra and O’Neil 1998). From a practical perspective, identifying which factors affect the development of intrapreneurial activities can be relevant for company managers, especially for those managers who are interested in implementing new innovative projects in their companies.

Finally, we suggest some limitations and future research lines. First, more accurate proxies for both our dependent and our independent variables could be used. On the one hand, some authors consider corporate entrepreneurship to be a very wide concept (Antoncic 2007) but most of the studies (including this research) measure only a part of the whole phenomenon (Alpkan et al. 2010; Chaston and Scott 2012; Parker 2011; Zahra 1991, among others). On the other hand, using other independent variables to gauge information about the environment could be especially enriching (as we could see if the impact of the environment is still limited when using other variables). In addition, sometimes in social sciences the boundaries between different constructs are not very clear. In this case, the RBT variables and the IE ones measure different information, but in further studies better proxies could be used so that the differences were more evident and unambiguous. Second, the conditioning factors for the corporate entrepreneurship concept could be analyzed putting emphasis on the different levels of analysis (environment, organization, individual). In this sense, other theoretical approaches could be used (such as the expectancy theory or the motivation theory). Third, when we posed a direct relationship between environmental factors and corporate entrepreneurship, we found a non-significant relationship between them. The effect of the institutional factors on intrapreneurship could be studied differently in further research, as it could behave as a moderator between corporate entrepreneurship and other variables.

Notes

Although entrepreneurship that occurs within organizations has been described in various terms (intrapreneurship, corporate entrepreneurship, corporate venturing or internal entrepreneurship, among others), in this article we use generally the term corporate entrepreneurship.

References

Adler, P., & Kwon, S. (2000). Social capital: The good, the bad and the ugly. In E. Lesser (Ed.), Knowledge and social capital: Foundations and applications (pp. 80–115). Boston: Butterworth-Heineman.

Aidis, R., Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. (2008). Institutions and entrepreneurship development in Russia: a comparative perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 23(6), 656–672.

Aldrich, H., & Zimmer, C. (1986). Entrepreneurship through social networks. In D. L. Sexton & R. W. Smilor (Eds.), The art and science of entrepreneurship (pp. 2–23). Cambridge: Ballinger.

Alpkan, L., Bulut, C., Gunday, G., Ulusoy, G., & Kilic, K. (2010). Organizational support for intrapreneurship and its interaction with human capital to enhance innovative performance. Management Decision, 48(5), 732–755.

Alvarez, S., & Busenitz, L. (2001). The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. Journal of Management, 27(6), 755–775.

Alvarez, C., & Urbano, D. (2011). Environmental factors and entrepreneurial activity in Latin America. Academia, Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 48, 31–45.

Anderson, A. R., Dodd, S. D., & Jack, S. L. (2012). Entrepreneurship as connecting: some implications for theorising and practice. Management Decision, 50(5), 958–971.

Antoncic, B. (2007). Intrapreneurship: a comparative structural equation modeling study. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 107(3), 309–325.

Antoncic, B., & Hisrich, R. D. (2001). Intrapreneurship: construct refinement and cross-cultural validation. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(5), 495–527.

Antoncic, B., & Hisrich, R. D. (2003). Clarifying the intrapreneurship concept. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 10(1), 7–24.

Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., & Ray, S. (2003). A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 105–123.

Arenius, P., & De Clercq, D. (2005). A network-based approach on opportunity recognition. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 249–265.

Arenius, P., & Kovalainen, A. (2006). Similarities and differences across the factors associated with women’s self-employment preference in the Nordic countries. International Small Business Journal, 24(1), 31–59.

Arenius, P., & Minniti, M. (2005). Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 233–247.

Audretsch, D. (2012). Entrepreneurship research. Management Decision, 50(5), 755–764.

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Barney, J. B., Wright, M., & Ketchen, D. J. (2001). The resource-based view of the firm: 10 years after 1991. Journal of Management, 27(6), 625–641.

BarNir, A. (2012). Starting technologically innovative ventures: reasons, human capital, and gender. Management Decision, 50(3), 399–419.

Battistella, C., Biotto, G., & De Toni, A. (2012). From design driven innovation to meaning strategy. Management Decision, 50(4), 718–743.

Begley, T. M., Tan, W., & Schoch, H. (2005). Politico-economic factors associated with interest in starting a business: a multi-country study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(1), 35–55.

Bhide, A. (2000). The origin and evolution of new businesses. New York: Oxford University Press.

Blanchflower, D. G. (2004). Self-employment: More may not be better. NBER Working Paper No.10286. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Blyler, M., & Coff, R. W. (2003). Dynamic capabilities, social capital, and rent appropriation: ties that split ties. Strategic Management Journal, 24(7), 677–686.

Boermans, M. A. (2010). The entrepreneurial society. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 6(4), 523–526.

Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H. L. (2010). Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3), 421–440.

Burgelman, R. A. (1985). Managing the new venture division: research findings and implications for strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 6(1), 39–54.

Burgers, J. A., Jansen, J. J. P., Van den Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. (2009). Structural differentiation and corporate venturing: the moderating role of formal and informal integration mechanisms. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(3), 206–220.

Burt, R. (1992). The social structure of competition. In N. Nitkin & R. Eccles (Eds.), Networks and organizational structure, form and action (pp. 57–91). Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Carroll, C. E., & McCombs, M. (2003). Agenda-setting effects of business news on the public’s images and opinions about major corporations. Corporate Reputation Review, 6(1), 36–46.

Castrogiovanni, G. J., Urbano, D., & Loras, J. (2011). Linking corporate entrepreneurship and human resource management in SMEs. International Journal of Manpower, 32(1), 34–47.

Chandler, G. N., Honig, B., & Wiklund, J. (2005). Antecedents, moderators, and performance consequences of membership change in new venture teams. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(5), 705–725.

Chang, Y. Y., Hughes, M., & Hotho, S. (2011). Internal and external antecedents of SMEs’ innovation ambidexterity outcomes. Management Decision, 49(10), 1658–1676.

Chaston, I., & Scott, G. J. (2012). Entrepreneurship and open innovation in an emerging economy. Management Decision, 50(7), 1161–1177.

Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295–316.

Coduras, A., Urbano, D., Rojas, A., & Martínez, S. (2008). The relationship between university support to entrepreneurship with entrepreneurial activity in Spain: a GEM data based analysis. International Advances in Economic Research, 14(4), 395–406.

Covin, J. G., & Miles, M. P. (1999). Corporate entrepreneurship and the pursuit of competitive advantage. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(3), 47–63.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1991). A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(1), 7–25.

Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331.

Deephouse, D. (2000). Media reputation as a strategic resource: an integration of mass communication and resource-based theories. Journal of Management, 26(6), 1091–1112.

Dess, G. G., Ireland, R. D., Zahra, S. A., Floyd, S. W., Janney, J. J., & Lane, P. J. (2003). Emerging issues in corporate entrepreneurship. Journal of Management, 29(3), 351–378.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2002). The regulation of entry. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 1–37.

Fritsch, M. (2008). How does new business formation affect regional development? introduction to the special issue. Small Business Economics, 30(1), 1–14.

Gaglio, C. M., & Katz, J. A. (2001). The psychological basis of opportunity identification: entrepreneurial alertness. Small Business Economics, 16(2), 95–111.

Gnyawali, D. R., & Fogel, D. S. (1994). Environments for entrepreneurship development: key dimensions and research implications. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 18(4), 43–62.

Gomez-Haro, S., Aragon-Correa, J. A., & Cordon-Pozo, E. (2011). Differentiating the effects of the institutional environment on corporate entrepreneurship. Management Decision, 49(9–10), 1677–1693.

Greene, W. (2008). Functional forms for the negative binomial model for count data. Economics Letters, 99(3), 585–590.

Grilo, I., & Thurik, R. (2005). Latent and actual entrepreneurship in Europe and the US: some recent developments. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1(4), 441–459.

Guerrero, M., & Urbano, D. (2012). The development of an entrepreneurial university. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 37(1), 43–74.

Guth, W. D., & Ginsberg, A. (1990). Guest editors’ introduction: corporate entrepreneurship. Strategic Management Journal, 11(4), 5–15.

Hayton, J. C., & Kelley, D. J. (2006). A competency-based framework for promoting corporate entrepreneurship. Human Resources Management, 45(3), 407–427.

Hornsby, J. S., Kuratko, D. F., & Zahra, S. A. (2002). Middle managers’ perception of the internal environment for corporate entrepreneurship: assessing a measurement scale. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(3), 253–273.

Hornsby, J. S., Kuratko, D. F., Shepherd, D. A., & Bott, J. P. (2009). Managers corporate entrepreneurial actions: examining perception and position. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(3), 236–247.

Hostager, T. J., Neil, T. C., Decker, R. L., & Lorentz, R. D. (1998). Seeing environmental opportunities: effects of intrapreneurial ability, efficacy, motivation and desirability. Journal of environmental change management, 11(1), 11–25.

Huarng, K. H., & Yu, T. H. K. (2011). Entrepreneurship, process innovation and value creation by a non-profit SME. Management Decision, 49(2), 284–296.

Hult, G. T. M., & Ketchen, D. J. (2001). Does market orientation matter?: a test of the relationship between positional advantage and performance. Strategic Management Journal, 22(9), 899–906.

Idris, A., & Tey, L. S. (2011). Exploring the motives and determinants of innovation performance of Malaysian offshore international joint ventures. Management Decision, 49(10), 1623–1641.

Johannisson, B. (1986). Network strategies: management technology for entrepreneurship and change. International Small Business Journal, 5(1), 19–30.

Keen, C., & Etemad, H. (2012). Rapid growth and rapid internationalization: the case of smaller enterprises from Canada. Management Decision, 50(3–4), 569–590.

Kihlstrom, R. E., & Laffont, J. J. (1979). A general equilibrium theory of firm formations based on risk aversion. Journal of Political Economy, 87(4), 719–748.

Kirzner, I. (1997). Entrepreneurial discovery and the competitive market process: an Austrian approach. Journal of Economic Literature, 35(1), 60–85.

Klyver, K., Hindle, K., & Meyer, D. (2008). Influence of social networks structure on entrepreneurship participation—a study of 20 national cultures. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(3), 331–347.

Knight, G. A. (1997). Cross-cultural reliability and validity of a scale to measure firm entrepreneurial orientation. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(3), 213–225.

Koellinger, P. (2008). Why are some entrepreneurs more innovative than others? Small Business Economics, 31(1), 21–37.

Koellinger, P., & Minniti, M. (2006). Not for lack of trying: American entrepreneurship in black and white. Small Business Economics, 27(1), 59–79.

Kostova, T., & Roth, K. (2002). Adoption of an organizational practice by subsidiaries of multinational corporations: institutional and relational effects. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 215–233.

Langowitz, N., & Minniti, M. (2007). The entrepreneurial propensity of women. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 21(3), 341–364.

Lee, S. M., Hwang, T., & Choi, D. (2012). Open innovation in the public sector of leading countries. Management Decision, 50(1), 147–162.

Lepak, D. P., & Snell, S. A. (1999). The human resource architecture: toward a theory of human capital allocation and development. Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 31–48.

Liñán, F., Urbano, D., & Guerrero, M. (2011a). Regional variations in entrepreneurial cognitions: start-up intentions of university students in Spain. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development., 23(3–4), 187–215.

Liñán, F., Rodríguez-Cohard, J. C., & Rueda-Cantuche, J. M. (2011b). Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: a role for education. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(2), 195–218.

Lounsbury, M., & Glynn, M. A. (2001). Cultural entrepreneurship: stories, legitimacy, and the acquisition of resources. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 545–564.

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 2(3), 135–172.

MacMillan, I. C. (1986). Progress in research on corporate venturing. In D. L. Sexton & R. W. Smilor (Eds.), The art and science of entrepreneurship (pp. 241–263). Cambridge: Ballinger Publishing Company.

Menzel, H. C., Aaltio, I., & Ulijn, J. M. (2007). On the way to creativity: engineers as intrapreneurs in organizations. Technovation, 27(12), 732–743.

Meyskens, M., Robb-Post, C., Stamp, J. A., Carsrud, A., & Reynolds, P. D. (2010). Social ventures from a resource-based perspective: an exploratory study assessing global ashoka fellows. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(4), 661–680.

Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29(7), 770–791.

Minniti, M., & Nardone, C. (2007). Being in someone else’s shoes: the role of gender in nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 28, 223–238.

Mousa, F. T., & Wales, W. (2012). Founder effectiveness in leveraging entrepreneurial orientation. Management Decision, 50(1–2), 305–324.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

North, D. C. (2005). Understanding the process of economic change. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ostgaard, T., & Birley, S. (1996). New venture growth and personal networks. Journal of Business Research, 36(1), 37–50.

Owen-Smith, J., & Powell, W. W. (2004). Knowledge networks as channels and conduits: the effects of spillovers in the Boston biotechnology community. Organization Science, 15(1), 5–21.

Parker, S. (2011). Intrapreneurship or entrepreneurship? Journal of Business Venturing, 26(1), 19–34.

Penrose, E. T. (1959). Teoría del crecimiento de la empresa. Madrid: Ed. Aguilar.

Pinchot, G. (1985). Intrapreneuring. New York: Harper & Row Publisher.

Pollock, T. G., & Rindova, V. P. (2003). Media legitimation effects in the market for initial public offerings. Academy of Management Journal, 46(5), 631–642.

Renko, M., Shrader, R. C., & Simon, M. (2012). Perception of entrepreneurial opportunity: a general framework. Management Decision, 50(7), 1233–1251.

Ribeiro-Soriano, D., & Urbano, D. (2009). Overview of collaborative entrepreneurship: an integrated approach between business decisions and negotiations. Group Decision and Negotiation, 18(5), 419–430.

Rindova, V. P., Petkova, A. P., & Kotha, S. (2007). Standing out: how new firms in emerging markets build reputation. Strategic Organization, 5(1), 31–70.

Saxton, G. D., & Benson, M. A. (2005). Social capital and the growth of the non-profit sector. Social Science Quarterly, 86(1), 16–35.

Shane, S. (2000). Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organization Science, 11(4), 448–469.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226.

Stevenson, H. H., & Jarillo, J. C. (1990). A paradigm of entrepreneurship: entrepreneurial management. Strategic Management Journal, 11(5), 17–27.

Stopford, J. M., & Baden-Fuller, C. W. F. (1994). Creating corporate entrepreneurship. Strategic Management Journal, 15(7), 521–536.

Tanas, J. K., & Audretsch, D. B. (2011). Entrepreneurship in transitional economy. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(4), 431–442.

Thornton, P., Ribeiro-Soriano, D., & Urbano, D. (2011). Socio-cultural factors and entrepreneurial activity: an overview. International Small Business Journal, 29(2), 105–118.

Tominic, P., & Rebernik, M. (2007). Growth aspirations and cultural support for entrepreneurship: a comparison of post-socialist countries. Small Business Economics, 28(2–3), 239–255.

Urbano, D., & Yordanova, D. (2008). Determinants of the adoption of HRM practices in tourism SMEs in Spain: an exploratory study. Service Business, 2(3), 167–185.

van Stel, A., Storey, D. J., & Thurik, R. (2007). The effect of business regulations on nascent and young business entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 28(2–3), 171–186.

Welter, F., & Smallbone, D. (2011). Institutional perspectives on entrepreneurial behaviour in challenging environments. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 107–125.

Wennekers, S., van Stel, A., Thurik, R., & Reynolds, P. (2005). Nascent entrepreneurship and the level of economic development. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 293–309.

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180.

Westhead, P., Wright, M., & Ucbasaran, D. (2001). The internationalization of new and small firms: a resource-based view. Journal of Business Venturing, 16, 333–358.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance-matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48(4), 817–838.

Yang, T. T., & Li, C. R. (2011). Competence exploration and exploitation in new product development: the moderating effects of environmental dynamism and competitiveness. Management Decision, 49(9), 1444–1470.

Zahra, S. A. (1991). Predictors and financial outcomes of corporate entrepreneurship: an exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(4), 259–285.

Zahra, S. A., & O’Neil, H. M. (1998). Charting the landscape of global competition: reflections on emerging organizational challenges and their implications for senior executives. The Academy of Management Executive, 12(4), 13–21.

Zortea-Johnston, E., Darroch, J., & Matear, S. (2012). Business orientations and innovation in small and medium sized enterprises. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 8(2), 145–164.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Projects ECO2010-16760 (Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation) and 2005SGR00858 (Catalan Government Department for Universities, Research and Information Society).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Urbano, D., Turró, A. Conditioning factors for corporate entrepreneurship: an in(ex)ternal approach. Int Entrep Manag J 9, 379–396 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0261-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0261-8