Abstract

In this study, cobalt ferrite/mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4) nanocomposites were successfully synthesized by using a two-step protocol. Firstly, monodispersed CoFe2O4 nanoparticles (NPs) were synthesized via thermal decomposition of metal precursors in a hot surfactant solution and then they were assembled on mpg-C3N4 via a liquid phase self-assembly method. The sonocatalytic performance of as-synthesized CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites was evaluated on the methylene blue (MB) removal from water under ultrasonic irradiation. For this purpose, response surface methodology (RSM) based on central composite design (CCD) model was successfully utilized to optimize the MB removal over CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to investigate the significance of the model. The results predicted by the model were obtained to be in reasonable agreement with the experimental data (R2 = 0.969, adjusted R2 = 0.942). Pareto analysis demonstrated that pH of the solution was the most effective parameter on the sonocatalytic removal of MB by CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites. The optimum catalyst dose, initial dye concentration, pH, and sonication time were set as 0.25 g L−1, 8 mg L−1, 8, and 45 min, respectively. The high removal efficiency of MB dye (92.81%) was obtained under optimal conditions. The trapping experiments were done by using edetate disodium, tert-butyl alcohol, and benzoquinone. Among the reactive radicals, •OH played a more important role than h+ and \( {O}_2^{-\bullet } \) in the MB dye removal process. Moreover, a proposed mechanism was also presented for the removal of MB in the presence of CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites under the optimized sonocatalytic conditions. Finally, a reusability test of the nanocomposites revealed a just 9.6% decrease in their removal efficiency after five consecutive runs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Human beings and aquatic life are exposed to harmful effects caused by toxic organic dyes present in aqueous environments. Furthermore, light diffusion into aqueous phase is hindered by organic dye sewages discharged into waterways (Gholivand et al. 2015; Gürses et al. 2014). The printing, paper, textile, pulp mill, carpet, cosmetics, and food industries extensively use those substances containing substantial coloring capability (Hassani et al. 2014). Many efforts have been spent on the development of an effective way for the removal of organic dyes from the water phases because of the detrimental impacts of dye pollutants on aquatic life and human health (Darvishi Cheshmeh Soltani et al. 2016; Moura et al. 2016; Shankaraiah et al. 2014). Nonetheless, the efficiency of conventional biological treatment technologies is questionable for the treatment of synthetic organic dyes since synthetic dyes are stable, less biodegradable, and contain abundant quantities of aromatic compounds (Grčić et al. 2013). Consequently, attempts have been made to use traditional physicochemical techniques such as adsorption, nanofiltration, and coagulation-flocculation processes for the elimination of dye pollutants (Hassani et al. 2018c). However, these treatment approaches are considered to be nondestructive for transferring dye molecules only from aquatic phase to another one, which leads to the formation of secondary pollutants (Wang et al. 2007). In order to eliminate toxic chemicals, remarkable endeavors have now focused on developing more effective solutions (Hassani et al. 2018a; Taherian et al. 2013). In this regard, numerous investigations have recently been dedicated to the use of advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) generating hydroxyl radicals (•OH) as one of the most potent oxidizing agents for the elimination of various organic contaminants from water phase (Meijide et al. 2017; Modirshahla et al. 2012; Sabri et al. 2018). Additionally, electrocatalytic hydrogenation and hydrogenolysis (ECH) have been recognized as a promising technology for the elimination and decomposition of recalcitrant compounds. Especially for water purification, ECH has been demonstrated with high efficiency in treating the persistent contaminants (Jiang et al. 2017; Jiang et al. 2018). Sonocatalytic processes that use suitable catalysts under ultrasonic irradiation are one of the more favorable technologies among the AOP techniques for the production of •OH in aqueous solution and thus effective exclusion of refractory organic compounds (Areerob et al. 2018; Darvishi Cheshmeh Soltani et al. 2016). Recently, sonochemical removal of organic pollutants in aqueous solution has been reported as a novel AOP in which reactive species including •OH, hydrogen (H•), and perhydroxyl (\( H{O}_2^{\bullet } \)) radicals are formed via acoustic cavitation described as the cyclic formation, growth, and implosive collapse of tiny bubbles in aqueous phase subjected to high-intensity ultrasound (Chadi et al. 2018; Khataee et al. 2018a). The ultrasonic irradiation produces positive holes and free radicals, which supports to the catalyst for the generation of more •OH radicals in water (Khataee et al. 2018b; Weng and Huang 2015). Nevertheless, full organic contaminant elimination using ultrasound alone is time-consuming and energy demanding. These drawbacks can be surmounted by combining sonolysis with an appropriate heterogeneous catalyst being activated under ultrasonic irradiation gaining ground recently. The use of a proper catalyst noticeably promotes the formation of •OH and efficient sonocatalysis of pollutant elimination, which is probably caused by a synergistic effect between the ultrasonic irradiation and the solid semiconductor catalyst (Hassani et al. 2018a). Existing evidence indicates the use of various semiconductors as sonocatalysts including CeO2-biochar (Khataee et al. 2018b), CoFe2O4@ZnS (Farhadi et al. 2017), Fe2.8Ce0.2O4 (Khataee et al. 2018c), Ce/ZnTiO3 (Eskandarloo et al. 2016), TiO2/MMT (Hassani et al. 2017), Ni-ZnO (Saharan et al. 2015), LaFeO3 (Dükkancı 2018), KNbO3 (Zhang et al. 2016), CdSe/GQDs (Sajjadi et al. 2017), WO3 (Li et al. 2018), CdS (Song et al. 2018), and β-Bi2O3 (Chen et al. 2016). Thus, it is necessary to develop new magnetic sonocatalysts with elevated catalytic activity.

Recently, graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4), a polymeric semiconductor, composed of C, N, and H atoms, has been in the focus of widespread catalytic uses (Hassani et al. 2018b; Zhu et al. 2014). However, g-C3N4 has several drawbacks such as fast recombination, limited surface area, and low conductivity (Dong et al. 2014). To suitably resolve these drawbacks, mesoporous g-C3N4 (mpg-C3N4) are prepared with a far greater surface area in which mpg-C3N4 is combined with various semiconductors containing ideal band gaps to enlarge the absorption range of mpg-C3N4 (Erdogan et al. 2016). Nevertheless, separation of sonocatalysts from treated water is difficult because their typical usage is in the form of nanoparticles (NPs). The practical uses of magnetic separation of sonocatalysts have rendered them a desirable and beneficial method. By keeping this in mind, the spinel structure and extraordinary properties of cobalt ferrite (CoFe2O4) NPs have presented them an effective magnetic material for environmental purification (Hassani et al. 2018a; Yao et al. 2016). Magnetic ferrite NPs are combined with mpg-C3N4, making it possible to prevent agglomeration and deactivation of the sonocatalyst within the regeneration process; moreover, the synergistic impacts in the hybrid structure might further improve the sonocatalytic activity of mpg-C3N4 (Yao et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2013). To the best of our knowledge, there is no report on modeling and optimizing the organic dye elimination from water via a sonocatalytic process using CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites as catalyst. The process modeling pays a substantial role in the development and enhanced identification of sonocatalytic processes. Therefore, the present study mainly focuses on the performance optimization of CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites for the elimination of methylene blue (MB) dye in water via sonocatalytic process. Response surface methodology (RSM) based on central composite design (CCD) was examined to further analyze the impacts of different operational parameters. The influence of catalyst dose, initial dye concentration, pH, and sonication time on the removal of MB via the sonocatalytic technique were examined to further analyze the impacts of different operational parameters. To determine the effectiveness of an experimental system, the current research selected RSM as an operative statistical and mathematical methodology (Hassani et al. 2015b; Khataee et al. 2013). RSM with a minimum number of experiments was employed to simultaneously evaluate a variety of parameters. Thus, application of RSM in a study help lessen the cost, reduce process variability, and lower the time needed comparing to the traditional one factor at a time statistical approach (Khataee et al. 2011a; Zolgharnein et al. 2014).

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Guanidine hydrochloride (≥ 99%), Ludox® HS40 colloidal silica (40 wt% suspension in H2O), ammonium hydrogen difluoride (NH4HF2, 95%), cobalt(II) acetylacetonate (Co(acac)2, 97%), iron(III) acetylacetonate (Fe(acac)3, 97%), oleic acid (OAc, 90%), oleylamine (OAm, > 70%), benzyl ether (BE, 99%), 1,2-tetradecanediol (1,2-TDD, 97%), hexanes (97%), isopropanol (99%), ethanol (99%) and acetone (97%), edetate disodium (EDTA-2Na), tert-butyl alcohol (t-BuOH), and benzoquinone (BQ) were provided from Sigma-Aldrich and used as they are. The MB dye was provided from Alvan Sabet Co. (Iran). The chemical structure and characteristics of the dye are represented in Table 1.

Instrumentation

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images were obtained using a Hitachi HT7700 TEM instrument equipped with the EXALENS HR-TEM lens operated at 120 kV. High-resolution scanning electron microscope (HR-SEM) was implemented by means of a Zeiss Sigma 300 SEM instrument. X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern was analyzed using a Panalytical Empyrean diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation (40 kV, 15 mA, 1.54051 Å). Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area and Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) pore size analyses were examined by a Micromeritics 3Flex instrument. The photoluminescence (PL) spectra were recorded with a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Varian, Cary Eclipse) using a Xe lamp as the excitation source.

Synthesis of mpg-C3N4 and monodispersed CoFe2O4 NPs

The detailed procedure for the synthesis of mpg-C3N4 via a silica templating method was reported elsewhere (Erdogan et al. 2016). Monodispersed CoFe2O4 NPs were synthesized by using a surfactant-assisted chemical decomposition of metal precursors in a hot organic solution, which is reported elsewhere (Hassani et al. 2018b).

Preparation of CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites

For synthesis of CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites, CoFe2O4 NPs were assembled on mpg-C3N4 via a liquid self-assembly method that is reported by our group at many times (Guo and Sun 2012). In a typical procedure, mpg-C3N4 (100 mg) was dispersed in ethyl alcohol (20 mL) with the help of sonication and then the hexane dispersion of CoFe2O4 NPs (100 mg) were added into the mpg-C3N4 dispersion. Then, the obtained mixture was sonicated for 3 h. The mixture was then centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 10 min after ethyl alcohol addition to separate the yielded CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites from the solution.

Experimental procedure

In a typical dye removal experiments, a 250-mL Erlenmeyer flask was placed into an ultrasonic bath apparatus (WUC-D10H, 40 kHz, 665 W). It should be noted that the bottom side of the Erlenmeyer flask was located at 1 cm afar from the ultrasonic irradiation source. The temperature of the ultrasonic bath was adjusted by water circulator during the experiments. The working power of the ultrasonic bath was kept constant at 400 W. For the sonocatalysis, simulated wastewater containing 100 mL of desired concentrations of MB and sonocatalyst were introduced into the reactor to start the experiment. Next, the pH of the suspension was adjusted to the desired values by using HCl/NaOH (0.1 M) and measuring the pH of solution with a pH meter (Mettler Toledo). Next, the suspension was stirred for 10 min in dark place before the sonication is performed to achieve the saturated adsorption between the MB dye and sonocatalyst. To ascertain the role of only adsorption in the removal process, the suspension was stirred magnetically. The catalyst dose, initial dye concentration, the pH of the solution, and the sonication time were chosen as the main operational factors. At given sonication times, the 4-mL sample was taken out, centrifuged (Universal 320 Hettich) at 9000 rpm for 10 min, and then MB concentration analyzed by UV-vis spectrophotometer (Varian Cary 100) at λmax = 665 nm. Equation (1) was used to calculate the removal efficiency (%) of MB.

where A0 and At refer to initial and final MB absorbance, respectively.

Experimental design

A CCD was employed to determine the optimal conditions for the main parameters. For the sonocatalytic process, significant variables, such as the catalyst dose, initial dye concentration, pH, and sonication time, were regarded as independent and designated as X1–X4, respectively. A catalyst dose (X1) range of 0.1–0.3 g L−1, initial dye concentration (X2) range of 4–20 mg L−1, pH (X3) of 2–10, and sonication time (X4) range of 15–75 min were chosen, as given in Table 2.

The number of experiments was evaluated using Eq. (2):

where N, k, and x0 represented the number of experiments, variables, and replications, respectively (Hassani et al. 2015a). Therefore, 31 experimental runs were designed by the CCD (k = 4, x0 = 7). The relation between the variables (Xi) were coded as xi using Eq. (3):

where X0 and δX were the values of Xi at the center point and step change, respectively (Hassani et al. 2015a; Hassani et al. 2015c). The relationships between the response (Y) and the four input parameters were explained by using a quadratic equation as follows:

where Y was the predicted removal efficiency and b0, bi, bij, and bii were the constant, linear, interaction, and quadratic coefficients, respectively (Hassani et al. 2015c). Furthermore, xi and xj were the coded values for the experimental parameters. The Design-Expert Software (version 10) and the Minitab Software (version 16) were used to data analysis and factorial optimization.

Results and discussion

Characterization

Monodispersed CoFe2O4 NPs were synthesized by the thermal decomposition of metal (II or III) acetylacetonates in the solution of oleylamine, oleic acid, 1,2-tetradecanediol, and benzyl ether at 295 °C, which is a well-established protocol reported elsewhere (Sun et al. 2004). Figure 1a depicts a TEM image of colloidal CoFe2O4 NPs indicating the highly monodispersed particle size and morphology of the NPs with a mean particle size of 10 nm. As-prepared CoFe2O4 NPs were then supported on mpg-C3N4 via a liquid phase self-assembly method and the structures of yielded CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites were analyzed by TEM, HR-SEM, XRD, and ICP-MS. Figure 1b shows a TEM image of CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites revealing the successful assembly of CoFe2O4 NPs over mpg-C3N4 by preserving almost their initial particle size and morphology. Moreover, there were no agglomerated NPs encountered by the investigation of almost whole TEM grid. The CoFe2O4 loading ratio of CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites was found to be 12.3 wt% as a result of ICP-MS analysis. Figure 1c, d shows representative HR-SEM images of CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites showing the plenty of nanosheets with an aggregated structure of mpg-C3N4 and the nearly homogeneous distribution of CoFe2O4 NPs over mpg-C3N4 sheets which is well-consistent with the TEM image.

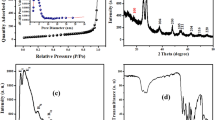

Figure 2a shows the XRD patterns of as-prepared CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites. The peaks arose at the 2θ value of 13.6° that corresponded to the (100) diffraction peak, which is related to interplanar structural packing. Moreover, the peak at 27.62° was due to the (002) plane of g-C3N4, and it showed interplanar graphitic stacking (JCPDS card 01-087-1526) (Erdogan et al. 2016; Heidari et al. 2018). The interlayer stacking distance for mpg-C3N4 was 0.322 nm. Additionally, the diffraction peaks that appeared at the 2θ value of 18.31°, 30.04°, 35.66°, 37.43°, 43.10°, 53.41°, 57.00°, 62.50°, 70.92°, 74.00°, and 74.99° (marked with “#”) on the CoFe2O4 NPs are readily assigned to the reflections of (111), (220), (311), (222), (400), (422), (511), (440), (620), (533), and (622) planes of the cubic spinel structured CoFe2O4 NPs (JCPDS card 00-022-1086), respectively (Hassani et al. 2018a). Plane (311) was applied to CoFe2O4 NPs to determine lattice values (cubic phase, a = b = c). The lattice parameter for the CoFe2O4 NPs was 8.342 Å. Based on these findings, the NPs were matched with the CoFe2O4 standards in JCPDS card 00-022-1086 (i.e., a = b = c = 8.391 Å).

The photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the mpg-C3N4 and CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites were recorded at an excitation wavelength of 325 nm to study the sonocatalytic activities (Fig. 2b). PL behavior demonstrates the separation recombination process of sono-generated electron-hole (e− − h+). It is observed that the CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites have the lowest PL intensity than the pure mpg-C3N4. Hence, sono-generated e− − h+ separation efficiency was significantly enhanced in CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites, which leads to prevent e− − h+ recombination and efficient sonocatalytic activity.

The BET surface area of mpg-C3N4 is 192.33 m2 g−1 and that of bulk g-C3N4 is 12 m2 g−1 (Xu et al. 2013), showing that preparation of mpg-C3N4 by silica templating method led to production of sample with high surface area in comparison to those of bulk g-C3N4. Besides the BET surface area, the average pore width and Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) pore volume of mpg-C3N4 catalyst were found to be 14.74 nm and 0.68 cm3 g−1, respectively. It is well known that the high surface area is helpful for the removal of target pollutant to achieve high sonocatalytic efficiency.

Removal of MB using different processes

A comparative study of sonocatalytic performance of pure mpg-C3N4 and CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites for the removal of the MB dye was studied. Figure 3 shows the efficiency of all tested materials under different processes for the removal of MB (8 mg L−1) from aqueous solution under the reaction conditions of catalyst dose of 0.25 g L−1, pH of 8, 400 W ultrasonic power, and 45 min of reaction time. As can be seen in Fig. 3, MB removal efficiency over treatment times of 45 min was less than 10% when only ultrasound (US, 1.46%) and mpg-C3N4 (9.86%) were separately used, which demonstrated the inefficiency of using sonication alone and adsorption in MB removal. The removal efficiencies of MB over mpg-C3N4 and CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites were found to be 34.58 and 92.81%, respectively, within 45 min under ultrasound irradiation (Fig. 3). This finding showed that the sonocatalytic activity of pure mpg-C3N4 could be improved by the incorporation of CoFe2O4 NPs along with the US. Moreover, the increment in removal efficiency in the presence of sonocatalyst might be related to the increasing number of cavitation bubbles formed on the surface of the sonocatalyst leading to more cleavage of water molecules and production of further •OH radicals. In addition, solid catalysts increase the mass transfer rate of MB molecules from liquid to the catalyst surface (Khataee et al. 2018b; Wang et al. 2010).

CCD modeling

To optimize the removal of MB using a sonocatalytic process, a four-variable CCD was employed. The individual and interactive effects of the input parameters and process output (removal efficiency) were evaluated using the CCD. The experimental and predicted dye removal efficiency for MB can be seen in Table 3.

The relation between the response (Y) and corresponding coded values is represented as Eq. (5):

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to investigate the suitability of the model (Hassani et al. 2014). Figure 4a depicts a favorable conformity between the predicted and experimental values. The regression model had a high coefficient determination (R2 = 0.969), which implies the model is capable of representing the process. There was no remarkable difference between the value of R2 and the value of the adjusted R2 (0.942), which indicates that the experiment’s results agreed with the predicted results (Khataee et al. 2011b).

The adequate precision for the ANOVA was 21.53, which is desirable because it is greater than 4 (Mannan et al. 2007). Moreover, the low coefficient of variation (CV = 4.75%) achieved in this study implied that the model was performed satisfactorily (Table 4).

Residuals, which are the differences between an experiment’s removal efficiency and predicted removal efficiency, are useful for evaluating the significance of a CCD model (Khataee et al. 2012). Figure 4b shows the normal probability compared to the residuals. As depicted, the residuals’ point formed a straight line; this confirmed the applicability of the model.

Furthermore, a random scattering of the residuals can be observed in the plots of the residuals compared to the expected values (Fig. 4c) and run number (Fig. 4d), which demonstrates a satisfactory fit of the model. The F value for the model was 36.03, which was superior to the tabulated F (2.37 at 95% significance), which confirms the validity of the model (Table 4) (Hassani et al. 2016).

A Pareto analysis can yield significant information that can help one interpret the results of a response surface model. This analysis was used to estimate the effect of each parameter on the response, as expressed in Eq. (6) (Abdessalem et al. 2008):

A Pareto graph analysis of MB can be seen in Fig. 5; the pH of the solution (35.12%) and the initial dye concentration (21.1%) had the greatest effects on removing MB in the sonocatalytic process.

To obtain the simplest model with the best fit for dye removal efficiency, insignificant terms with P values higher than 0.05 were eliminated from the model and the final quadratic model was rewritten as follows:

The significance of the regression coefficients

According to Table 5, the linear effects X1, X2, X3, and X4, the quadratic effects X11, X22, and X33, and the interactive effect X12 were significant with a confidence level of 95%. Hence, the statistically significant parameters were the linear effect of all the investigated parameters, the quadratic effect of the catalyst dose, the initial dye concentration, the initial pH, and the interaction effect of the catalyst dose with the initial dye concentration. According to the t and F values, the most effective model parameters were X2, X3, X33, X1, X11, and X22, respectively (see Table 5).

The effect of the parameters and their interactions on the dye removal

To assess the effect of four factors simultaneously on the removal of MB, a perturbation plot was used. A perturbation plot was used to identify the effective parameters on the response (Fig. 6). The steepest curve showed the most effective factor. However, a relatively flat line shows insensitivity toward response (Hassani et al. 2014).

As shown in Fig. 6, the catalyst dose (A), initial dye concentration (B), pH (C), and sonication time (D) were the control parameters to obtain the maximum efficiency for removing MB. A relatively steep curvature for the pH of the solution, catalyst dose, and the initial dye concentration indicated that the MB removal efficiency was sensitive to these parameters. The relatively flat curves for the sonication time showed that the influence of this factor was less on the dye removal than on the pH of the solution and the initial dye concentration. The sonication time curve was gradual, which indicates that this factor had a negligible effect on the response. The MB removal efficiency increased as the catalyst dose and pH increased and decreased, respectively, and the initial dye concentration increased (Fig. 6).

To assess the interactions of all four parameters, three-dimensional (3D) and two-dimensional (2D) were designed for the predicted responses based on quadratic model. Response surface plots are often used to estimate removal efficiencies for different values of tested parameters. In addition, contour plots are helpful in distinguishing types of interactions between tested parameters. Figure 7 shows the interaction between the initial MB concentration and the catalyst dose. The other two factors, the pH and the sonication time, were constant at 6 min and 45 min, respectively.

The 3D and 2D plots show a gradual increase in the removal efficiency (%) of MB as the dose of CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 increased from 0.1 to 0.25 g L−1. As shown in Fig. 7, the removal efficiency (%) increased as the dose of CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 increased, up to a specified value. Further dose increases did not lead to meaningful changes to the removal efficiency (%). Increasing the catalyst dose created additional nuclei for the cavitation bubbles to increase the production of free radicals (Song et al. 2012). The aggregation of CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 particles at higher doses resulted in a reduction of active surficial sites, which were generated in the solution. In addition, the excess sonocatalyst amount lowered the number of ultrasonic waves, which passed into the solution (Darvishi Cheshmeh Soltani et al. 2016; Hapeshi et al. 2013).

The pH of the solution was a vital parameter that influenced the physico-chemical properties of the solution and the surface of the nanocomposites. Figure 8 shows the interaction of the initial pH and the initial catalyst dose on the response, in which the initial dye concentration and the sonication time were constant at 12 mg L−1 and 45 min, respectively. The pHzpc value for the CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites was 6 (Hassani et al. 2018b). This value confirms the optimal pH ranges for removing dye from aqueous solutions. The pHzpc of the nanocomposites indicated that the surface of nanocomposites was positively charged at a pH of less than 6 and negatively charged at a pH of more than 6. As can be observed from Fig. 8, the removal efficiency reached its maximum at a pH 8.

It should be noted that MB is a cationic dye, and its removal on a CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 surface is not possible in an acidic solution because of repulsive forces between the nanocomposite surface and the MB dye. However, with high pH values, the conditions for forming active species are favorable, as the values improve not only transfers of holes to adsorbed hydroxyls but also electrostatic effects between negatively charged CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 and MB dye. However, in alkaline solutions (pH > 8), there is a repulsion between negatively charged surfaces of nanocomposites and OH−anions. This fact can hamper •OH radicals from forming and can thus decrease the removal efficiency of dye (Rasoulifard et al. 2016).

For the mentioned reasons, the removal efficiency of MB dye on CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 attained a maximum and then decreases. It can therefore be deduced that the removal efficiency of MB was considerably influenced by the interaction of the catalyst dose and the pH. This can be verified by the observation that the pH had a higher F value than the other factors. Figure 9 shows response surface and contour plots of the removal efficiency as a function of the sonication time and the initial pH for the catalyst dose of 0.2 g L−1 and the initial dye concentration of 12 mg L−1. As depicted in Fig. 9, the highest removal efficiency occurred when initial pH was kept at 8 under all sonication time conditions.

The effect of the catalyst dose on the removal efficiency of MB is shown in Fig. 10, where the initial MB concentration and the pH were set to 12 mg L−1 and 6, respectively. The figure shows that the removal efficiency had a positive correlation with the catalyst dose. The increased removal efficiency, accompanied by an increased catalyst dose, was due to the increased surface area and the accessibility of more active sites for the isolation of MB dye molecules.

Figure 10 shows that increasing the catalyst dose from 0.25 to 0.3 g L−1 did not have a major impact on the removal efficiency. This was due to a partial aggregation of the catalyst at the high dose, which decreased the effective surface area (Darvishi Cheshmeh Soltani et al. 2016). However, as shown in Fig. 10, unlike the catalyst dose, the effect of the sonication time on the removal efficiency was insignificant. As can be seen in the figure, the effect of the catalyst dose was higher than that of the sonication time in which increasing the catalyst dose increased the removal efficiency. As shown in Table 5, this result can be proven using the smaller F value for the sonication time than for the other parameters. Additionally, the positive coefficients confirmed that these variables affect the sonocatalysis of MB positively, while the negative coefficients affect it negatively (Table 5).

Process optimization

One of the major objectives of this work was to identify the optimum condition for maximizing removal of MB dye using the mathematical model proposed. For this aim, numerical optimization was employed to determine the desired values for each factor and to reach the maximum removal efficiency. The results of the optimization for the removal of MB onto CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites are given in Table 6. The results obtained by the numerical optimization revealed that a maximum removal efficiency (%) of 95.12% can be obtained with a catalyst dose of 0.25 g L−1, an initial dye concentration of 8 mg L−1, a pH of 8, and a sonication time of 45 min. In order to validate the obtained results, an additional experiment was conducted under optimized values. It was found that under the optimum operational parameters, the experiment’s MB removal efficiency was 92.81%. Thus, it displayed the predictability of the model for use in real conditions.

An analysis of the scavengers’ effect on MB removal

To determine the mechanism for the sonocatalytic removal of MB using CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites, trapping experiments with active species, including superoxide radical (\( {\mathrm{O}}_2^{-\bullet } \)), hole (h+), and hydroxyl radical (•OH), using sonocatalytic process was carried out. Different scavengers were used in individual sonocatalytic processes to quench a reactive species. The scavengers used in the study were t-BuOH, for the •OH scavenger; BQ, for \( {\mathrm{O}}_2^{-\bullet } \), and EDTA-2Na, for h+ scavenger (Hassani et al. 2018a). It was found that the CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 dose, the initial concentration of MB, the pH, and the sonication time were stable at 0.25 g L−1, 8 mg L−1, 8, and 45 min, respectively. The effects of scavengers on the sonocatalytic process are shown in Fig. 11. As can be seen, adding BQ, EDTA-2Na, and t-BuOH caused the sonocatalytic removal of MB to decrease from 90.91 to 42.40%, 38.68%, and 36.99%, respectively. These results show the participation of the radicals in the sonocatalytic activity. Among the radicals, •OH was more than h+ and \( {\mathrm{O}}_2^{-\bullet } \)in removing MB.

Reaction mechanism of MB removal

The mechanism of sonocatalytic removal of MB may be explained in terms of two standpoints, namely “hot spot” and “sonoluminescence.” The collapse of the cavitation bubbles in water phase as the first mechanism forms “hot spots” at temperatures as high as 105 °C or 106 °C and pressures up to about 1000 bar (Wang et al. 2009). The pyrolysis of H2O molecules can be stimulated by such hot spots to produce •OH radicals and hydrogen radicals H• as presented in Eqs. (8) and (9) (Vinoth et al. 2017). Oxygen molecules are also disintegrated to yield oxygen atoms, which generate •OH radical after reacting with water molecules (Eqs. (10) and (11)) (Merouani et al. 2015).

Besides, utilization of semiconductor catalysts in the sonocatalytic system can improve the efficiency of sonocatalytic system through formation of electron-hole (e− − h+) pairs after the excitation of e− from the valence band (VB) to conduction band (CB). The improvement in the presence of sonocatalyst can be described by the sonoluminescence mechanism. Sonoluminescence involves emission of light via recombination of the free radicals created within cavitation bubbles. •OH radicals are then produced by oxidation of H2O molecules or OH−anions adsorbed on the sonocatalyst surface by the h+, \( {O}_2^{-\bullet } \), and •OOH radicals are formed by interaction of the CB electrons with adsorbed O2 being capable of reacting with organic dye molecules and improving the removal efficiency (Eqs. (12)–(17)) (Zhou et al. 2015).

The reusability of CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4

The reusability of a sonocatalyst is an important aspect and makes the sonocatalyst effective for practical applications (Hassani et al. 2018a). Hence, the reusability of the CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites was tested using the optimized conditions for the sonocatalytic removal of MB. The CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites were recovered by magnet, washed with distilled water, and dried at 80 °C; this process was repeated after every experiment. Two photographs of a vial that contained aqueous CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites are in Fig. 12, and they show a favorable dispersion of the nanocomposites in the aqueous solution (Fig. 12(a)). A magnet placed near the vial resulted in a magnetic separation of the CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites (Fig. 12(b)). Accordingly, it can be concluded that the stable nanocomposites could easily be recycled after being used in solutions. It was observed that the MB removal efficiency of the CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites decreased by 9.6% after five successive experimental runs (Fig. 12(c)). This result clearly shows that the CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites are magnetically separable sonocatalysts that are highly stable for removing organic dyes from aqueous solutions.

Photographs showing the dispersion of the CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites in the aqueous solution (a), magnetic separation of the CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites from treated solution by using a magnet (b), and the reusability of CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites in the sonocatalytic removal of MB under optimized parameters (c)

Conclusion

To sum up, this study discussed the successful synthesis of highly efficient CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites and their sonocatalysis performance for the removal of MB from aqueous solution. An RSM based on a CCD was utilized to optimize the removal of MB dye using CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 nanocomposites. The effects of the experiment parameters such as catalyst dose, initial dye concentration, pH, and sonication time on MB removal efficiency were studied. The ANOVA results revealed a favorable reliability for sonocatalytic removal efficiency (R2 = 0.969 and adjusted R2 = 0.942). A Pareto graph analysis demonstrated that among the variables, pH had the largest effect on removal efficiency. Moreover, an optimized removal efficiency of 92.81% was attained with a catalyst dose of 0.25 g L−1, an initial dye concentration of 8 mg L−1, a pH of 8, and a sonication time of 45 min. A trapping experiment indicated that all radicals participated in the sonocatalytic activity. Among the reactive radicals, •OH was more important than h+ and \( {O}_2^{-\bullet } \) in MB dye removal. A possible mechanism was also proposed for the elimination of MB in the sonocatalytic system. Finally, a reusability test of the nanocomposites revealed a just 9.6% decrease in their removal efficiency after five consecutive runs. Thus, this study clearly shows that a response surface methodology with a CCD is a suitable method for optimizing operating conditions and maximizing MB dye removal.

References

Abdessalem AK, Oturan N, Bellakhal N, Dachraoui M, Oturan MA (2008) Experimental design methodology applied to electro-Fenton treatment for degradation of herbicide chlortoluron. Appl Catal, B 78:334–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2007.09.032

Areerob Y, Cho JY, Jang WK, Oh W-C (2018) Enhanced sonocatalytic degradation of organic dyes from aqueous solutions by novel synthesis of mesoporous Fe3O4-graphene/ZnO@SiO2 nanocomposites. Ultrason Sonochem 41:267–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.09.034

Chadi NE, Merouani S, Hamdaoui O, Bouhelassa M (2018) New aspect of the effect of liquid temperature on sonochemical degradation of nonvolatile organic pollutants in aqueous media. Sep Purif Technol 200:68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2018.01.047

Chen X, Dai J, Shi G, Li L, Wang G, Yang H (2016) Sonocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B catalyzed by β-Bi2O3 particles under ultrasonic irradiation. Ultrason Sonochem 29:172–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.08.010

Darvishi Cheshmeh Soltani R, Jorfi S, Safari M, Rajaei M-S (2016) Enhanced sonocatalysis of textile wastewater using bentonite-supported ZnO nanoparticles: response surface methodological approach. J Environ Manag 179:47–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.05.001

Dong G, Zhang Y, Pan Q, Qiu J (2014) A fantastic graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) material: electronic structure, photocatalytic and photoelectronic properties. J Photochem Photobiol C 20:33–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2014.04.002

Dükkancı M (2018) Sono-photo-Fenton oxidation of bisphenol-A over a LaFeO3 perovskite catalyst. Ultrason Sonochem 40:110–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.04.040

Erdogan DA, Sevim M, Kısa E, Emiroglu DB, Karatok M, Vovk EI, Bjerring M, Akbey Ü, Metin Ö, Ozensoy E (2016) Photocatalytic activity of mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (mpg-C3N4) towards organic chromophores under UV and VIS light illumination. Top Catal 59:1305–1318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-016-0654-3

Eskandarloo H, Badiei A, Behnajady MA, Tavakoli A, Ziarani GM (2016) Ultrasonic-assisted synthesis of Ce doped cubic–hexagonal ZnTiO3 with highly efficient sonocatalytic activity. Ultrason Sonochem 29:258–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.10.004

Farhadi S, Siadatnasab F, Khataee A (2017) Ultrasound-assisted degradation of organic dyes over magnetic CoFe2O4@ZnS core-shell nanocomposite. Ultrason Sonochem 37:298–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.01.019

Gholivand MB, Yamini Y, Dayeni M, Seidi S, Tahmasebi E (2015) Adsorptive removal of alizarin red-S and alizarin yellow GG from aqueous solutions using polypyrrole-coated magnetic nanoparticles. J Environ Chem Eng 3:529–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2015.01.011

Grčić I, Vujević D, Žižek K, Koprivanac N (2013) Treatment of organic pollutants in water using TiO2 powders: photocatalysis versus sonocatalysis. React Kinet Mech Catal 109:335–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11144-013-0562-5

Guo S, Sun S (2012) FePt nanoparticles assembled on graphene as enhanced catalyst for oxygen reduction reaction. J Am Chem Soc 134:2492–2495. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja2104334

Gürses A, Hassani A, Kıranşan M, Açışlı Ö, Karaca S (2014) Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution using by untreated lignite as potential low-cost adsorbent: kinetic, thermodynamic and equilibrium approach. J Water Process Eng 2:10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2014.03.002

Hapeshi E, Fotiou I, Fatta-Kassinos D (2013) Sonophotocatalytic treatment of ofloxacin in secondary treated effluent and elucidation of its transformation products. Chem Eng J 224:96–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.048

Hassani A, Alidokht L, Khataee AR, Karaca S (2014) Optimization of comparative removal of two structurally different basic dyes using coal as a low-cost and available adsorbent. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 45:1597–1607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2013.10.014

Hassani A, Çelikdağ G, Eghbali P, Sevim M, Karaca S, Metin Ö (2018a) Heterogeneous sono-Fenton-like process using magnetic cobalt ferrite-reduced graphene oxide (CoFe2O4-rGO) nanocomposite for the removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution. Ultrason Sonochem 40:841–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.08.026

Hassani A, Darvishi Cheshmeh Soltani R, Kıranşan M, Karaca S, Karaca C, Khataee A (2016) Ultrasound-assisted adsorption of textile dyes using modified nanoclay: central composite design optimization. Korean J Chem Eng 33:178–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11814-015-0106-y

Hassani A, Eghbali P, Ekicibil A, Metin Ö (2018b) Monodisperse cobalt ferrite nanoparticles assembled on mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4): a magnetically recoverable nanocomposite for the photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes. J Magn Magn Mater 456:400–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2018.02.067

Hassani A, Karaca C, Karaca S, Khataee A, Açışlı Ö, Yılmaz B (2018c) Enhanced removal of basic violet 10 by heterogeneous sono-Fenton process using magnetite nanoparticles. Ultrason Sonochem 42:390–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.11.036

Hassani A, Khataee A, Karaca S, Karaca C, Gholami P (2017) Sonocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin using synthesized TiO2 nanoparticles on montmorillonite. Ultrason Sonochem 35:251–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.09.027

Hassani A, Khataee A, Karaca S, Karaca M, Kıranşan M (2015a) Adsorption of two cationic textile dyes from water with modified nanoclay: a comparative study by using central composite design. J Environ Chem Eng 3:2738–2749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2015.09.014

Hassani A, Kıranşan M, Soltani RDC, Khataee AR, Karaca S (2015b) Optimization of the adsorption of a textile dye onto nanoclay using a central composite design. Turk J Chem 39:734–749. doi:10.3906/kim-1412-64

Hassani A, Soltani RDC, Karaca S, Khataee A (2015c) Preparation of montmorillonite–alginate nanobiocomposite for adsorption of a textile dye in aqueous phase: isotherm, kinetic and experimental design approaches. J Ind Eng Chem 21:1197–1207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2014.05.034

Heidari S, Haghighi M, Shabani M (2018) Ultrasound assisted dispersion of Bi2Sn2O7-C3N4 nanophotocatalyst over various amount of zeolite Y for enhanced solar-light photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline in aqueous solution. Ultrason Sonochem 43:61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.01.001

Jiang G, Lan M, Zhang Z, Lv X, Lou Z, Xu X, Dong F, Zhang S (2017) Identification of active hydrogen species on palladium nanoparticles for an enhanced electrocatalytic hydrodechlorination of 2,4-dichlorophenol in water. Environ Sci Technol 51:7599–7605. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b01128

Jiang G, Wang K, Li J, Fu W, Zhang Z, Johnson G, Lv X, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Dong F (2018) Electrocatalytic hydrodechlorination of 2,4-dichlorophenol over palladium nanoparticles and its pH-mediated tug-of-war with hydrogen evolution. Chem Eng J 348:26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.04.173

Khataee A, Alidokht L, Hassani A, Karaca S (2013) Response surface analysis of removal of a textile dye by a Turkish coal powder. Adv Environ Res 2:291–308. http://dx.doi.org/10.12989/aer.2013.2.4.291

Khataee A, Eghbali P, Irani-Nezhad MH, Hassani A (2018a) Sonochemical synthesis of WS2 nanosheets and its application in sonocatalytic removal of organic dyes from water solution. Ultrason Sonochem 48:329–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.06.003

Khataee A, Gholami P, Kalderis D, Pachatouridou E, Konsolakis M (2018b) Preparation of novel CeO2-biochar nanocomposite for sonocatalytic degradation of a textile dye. Ultrason Sonochem 41:503–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.10.013

Khataee A, Hassandoost R, Rahim Pouran S (2018c) Cerium-substituted magnetite: fabrication, characterization and sonocatalytic activity assessment. Ultrason Sonochem 41:626–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.10.028

Khataee AR, Naseri A, Zarei M, Safarpour M, Moradkhannejhad L (2012) Chemometrics approach for determination and optimization of simultaneous photooxidative decolourization of a mixture of three textile dyes. Environ Technol 33:2305–2317. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593330.2012.665495

Khataee AR, Zarei M, Fathinia M, Jafari MK (2011a) Photocatalytic degradation of an anthraquinone dye on immobilized TiO2 nanoparticles in a rectangular reactor: destruction pathway and response surface approach. Desalination 268:126–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2010.10.008

Khataee AR, Zarei M, Ordikhani-Seyedlar R (2011b) Heterogeneous photocatalysis of a dye solution using supported TiO2 nanoparticles combined with homogeneous photoelectrochemical process: molecular degradation products. J Mol Catal A Chem 338:84–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2011.01.028

Li T, Song L, Zhang S (2018) A novel WO3 sonocatalyst for treatment of rhodamine B under ultrasonic irradiation. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25:7937–7945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-1086-8

Mannan S, Fakhru'l-Razi A, Alam MZ (2007) Optimization of process parameters for the bioconversion of activated sludge by Penicillium corylophilum, using response surface methodology. J Environ Sci 19:23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1001-0742(07)60004-7

Meijide J, Rosales E, Pazos M, Sanromán MA (2017) p-Nitrophenol degradation by electro-Fenton process: pathway, kinetic model and optimization using central composite design. Chemosphere 185:726–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.07.067

Merouani S, Hamdaoui O, Rezgui Y, Guemini M (2015) Sensitivity of free radicals production in acoustically driven bubble to the ultrasonic frequency and nature of dissolved gases. Ultrason Sonochem 22:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.07.011

Modirshahla N, Behnajady MA, Rahbarfam R, Hassani A (2012) Effects of operational parameters on decolorization of C. I. acid red 88 by UV/H2O2 process: evaluation of electrical energy consumption. CLEAN–Soil, Air, Water 40:298–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/clen.201000574

Moura JM, Gründmann DDR, Cadaval TRS, Dotto GL, Pinto LAA (2016) Comparison of chitosan with different physical forms to remove reactive black 5 from aqueous solutions. J Environ Chem Eng 4:2259–2267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2016.04.003

Rasoulifard MH, Dorraji MSS, Taherkhani S (2016) Photocatalytic activity of zinc stannate: preparation and modeling. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 58:324–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2015.06.008

Sabri NA, Nawi MA, Abu Bakar NHH (2018) Recyclable immobilized carbon coated nitrogen doped TiO2 for photocatalytic degradation of quinclorac under UV–vis and visible light. J Environ Chem Eng 6:898–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2017.12.043

Saharan P, Chaudhary GR, Lata S, Mehta SK, Mor S (2015) Ultra fast and effective treatment of dyes from water with the synergistic effect of Ni doped ZnO nanoparticles and ultrasonication. Ultrason Sonochem 22:317–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.07.004

Sajjadi S, Khataee A, Kamali M (2017) Sonocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by a novel graphene quantum dots anchored CdSe nanocatalyst. Ultrason Sonochem 39:676–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.05.030

Shankaraiah G, Saritha P, Pedamalla NV, Bhagawan D, Himabindu V (2014) Degradation of Rabeprazole-N-oxide in aqueous solution using sonication as an advanced oxidation process. J Environ Chem Eng 2:510–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2013.10.007

Song L, Li Y, Zhang S (2018) Sonocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B in presence of CdS. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25:10714–10719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-1369-8

Song L, Zhang S, Wu X, Wei Q (2012) A metal-free and graphitic carbon nitride sonocatalyst with high sonocatalytic activity for degradation methylene blue. Chem Eng J 184:256–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2012.01.053

Sun S, Zeng H, Robinson DB, Raoux S, Rice PM, Wang SX, Li G (2004) Monodisperse MFe2O4 (M = Fe, Co, Mn) Nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc 126:273–279. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja0380852

Taherian S, Entezari MH, Ghows N (2013) Sono-catalytic degradation and fast mineralization of p-chlorophenol: La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 as a nano-magnetic green catalyst. Ultrason Sonochem 20:1419–1427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.03.009

Vinoth R, Karthik P, Devan K, Neppolian B, Ashokkumar M (2017) TiO2–NiO p–n nanocomposite with enhanced sonophotocatalytic activity under diffused sunlight. Ultrason Sonochem 35:655–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.03.005

Wang J, Jiang Y, Zhang Z, Zhao G, Zhang G, Ma T, Sun W (2007) Investigation on the sonocatalytic degradation of Congo red catalyzed by nanometer rutile TiO2 powder and various influencing factors. Desalination 216:196–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2006.11.024

Wang J, Jiang Z, Zhang L, Kang P, Xie Y, Lv Y, Xu R, Zhang X (2009) Sonocatalytic degradation of some dyestuffs and comparison of catalytic activities of nano-sized TiO2, nano-sized ZnO and composite TiO2/ZnO powders under ultrasonic irradiation. Ultrason Sonochem 16:225–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2008.08.005

Wang J, Lv Y, Zhang L, Liu B, Jiang R, Han G, Xu R, Zhang X (2010) Sonocatalytic degradation of organic dyes and comparison of catalytic activities of CeO2/TiO2, SnO2/TiO2 and ZrO2/TiO2 composites under ultrasonic irradiation. Ultrason Sonochem 17:642–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2009.12.016

Weng C-H, Huang V (2015) Application of Fe0 aggregate in ultrasound enhanced advanced Fenton process for decolorization of methylene blue. J Ind Eng Chem 28:153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2015.02.010

Xu J, Wu H-T, Wang X, Xue B, Li Y-X, Cao Y (2013) A new and environmentally benign precursor for the synthesis of mesoporous g-C3N4 with tunable surface area. Phys Chem Chem Phys 15:4510–4517. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3CP44402C

Yao Y, Lu F, Zhu Y, Wei F, Liu X, Lian C, Wang S (2015) Magnetic core–shell CuFe2O4@C3N4 hybrids for visible light photocatalysis of Orange II. J Hazard Mater 297:224–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.04.046

Yao Y, Wu G, Lu F, Wang S, Hu Y, Zhang J, Huang W, Wei F (2016) Enhanced photo-Fenton-like process over Z-scheme CoFe2O4/g-C3N4 heterostructures under natural indoor light. Environ Sci Pollut Res 23:21833–21845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-7329-2

Zhang H, Wei C, Huang Y, Wang J (2016) Preparation of cube micrometer potassium niobate (KNbO3) by hydrothermal method and sonocatalytic degradation of organic dye. Ultrason Sonochem 30:61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.11.003

Zhang S, Li J, Zeng M, Zhao G, Xu J, Hu W, Wang X (2013) In situ synthesis of water-soluble magnetic graphitic carbon nitride photocatalyst and its synergistic catalytic performance. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 5:12735–12743. https://doi.org/10.1021/am404123z

Zhou M, Yang H, Xian T, Li RS, Zhang HM, Wang XX (2015) Sonocatalytic degradation of RhB over LuFeO3 particles under ultrasonic irradiation. J Hazard Mater 289:149–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.02.054

Zhu J, Xiao P, Li H, Carabineiro SAC (2014) Graphitic carbon nitride: synthesis, properties, and applications in catalysis. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 6:16449–16465. https://doi.org/10.1021/am502925j

Zolgharnein J, Bagtash M, Asanjarani N (2014) Hybrid central composite design approach for simultaneous optimization of removal of alizarin red S and indigo carmine dyes using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide-modified TiO2 nanoparticles. J Environ Chem Eng 2:988–1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2014.03.017

Acknowledgements

Paria Eghbali gratefully acknowledges the support of Atatürk University as a post-doctoral researcher.

Funding

The financial support by the Science Academy in the context of “Young Scientists Award Program (BAGEP)” is highly acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Responsible editor: Philippe Garrigues

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hassani, A., Eghbali, P. & Metin, Ö. Sonocatalytic removal of methylene blue from water solution by cobalt ferrite/mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4) nanocomposites: response surface methodology approach. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25, 32140–32155 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-3151-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-3151-3