Abstract

Purpose

The main goals of this study were to investigate (1) the behavior of microbial communities in response to low-dose bioavailable anthracene addition in lightly contaminated sediment from Bizerte Lagoon and (2) the effects of bioremediation treatments on microbial biomass, activity, and community structure.

Methods

Sediment microcosms amended with 1 ppm anthracene were incubated in triplicate during 30 days. Biostimulation (addition of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer) and bioaugmentation (inoculation of a hydrocarbonoclastic bacterium) were used as bioremediation treatments. Bacterial biomass was estimated using flow cytometry. Sediment oxygen consumption was measured with oxygen microelectrodes. Bacterial community structure was assessed by molecular fingerprints (terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism; T-RFLP) analysis.

Results

Anthracene contamination resulted in a significant reduction of bacterial abundance with an impact on cell integrity. Concomitantly, sediment oxygen consumption was strongly inhibited. Correspondence analysis on T-RFLP data indicated that bacterial community structures from anthracene-contaminated microcosms were different from that of the control. Interestingly, the changes observed in microbial biomass, structure, and activities as a result of anthracene contamination were not alleviated even with the use of biostimulation and combination of biostimulation and bioaugmentation strategy for anthracene bioremediation. Nevertheless, both treatment methods resulted in different community structures relative to the contaminated and control microcosms with the appearance of distinct populations.

Conclusion

Anthracene spiking severely affected microbial communities, suggesting dominance of nontolerant populations in this lightly-contaminated sediment. Although biostimulation and/or bioaugmentation treatments did not alleviate the anthracene toxic effects, the changes observed in microbial population and structure suggest that the proposed treatments might be promising to promote bacterial growth. Further works are still required to propose a more efficient strategy to stimulate biodegradation that takes into account the complex interactions between species for resource access.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Pollution of coastal marine ecosystems by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) is a ubiquitous environmental problem (Tam et al. 2001). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are present in petroleum and formed during the incomplete combustion of almost any organic material (Atagana 2006). These compounds are considered hazardous because of their cytotoxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic effects (Samanta et al. 2002). Petroleum hydrocarbons have been shown to affect life history parameters (Bridges et al. 1994) and immune systems (Tahir et al. 1993) of benthic organisms, as well as the structure of entire benthic communities (Nance 1991). Significant toxicological effects of PAHs on macrobenthic organisms have been observed at concentrations below 1 mg PAH/kg dry sediment (e.g., Long 1992), while in polluted sediments meio- and microbenthic communities were not significantly influenced by the addition of sublethal concentration of PAHs (0.3–3 mg kg−1; Carman et al. 1995). Similarly, PAHs have been found to exhibit rather low toxicity toward sediment microbial activity (Myers et al. 1994) even at high concentrations (Bauer and Capone 1985).

Anthracene belongs to anthropogenic pollutants recommended for investigations by the US Environmental Protection Agency (Dabestani and Ivanov 1999) because of its high toxicity and wide occurrence in the environment. Anthracene is a three-fused-aromatic ring PAH, present in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems primarily as a result of runoff from former wood-treating operations and coal gasification plants, and as a result of other types of petrochemical pollution (Brenner et al. 2002; Mueller et al. 1989). Anthracene was the first PAH for which phototoxicity was reported in aquatic systems (Bowling et al. 1983) and anthracene has been used as a representative phototoxic PAH (Kochevar et al. 1982). This molecule is known to be phototoxic to the luminescent bacterium Vibrio fischeri (El-Alawi et al. 2001; McConkey et al. 1997). Nevertheless, growth and activities of the bacterium were not affected by addition of photomodified or intact anthracene for concentrations up to 4 mg L−1 (El-Alawi et al. 2002).

Bioremediation has been recognized as an attractive decontamination strategy for a variety of polluted environments. The degradation of PAH by microorganisms depends to a large extent on their molecular weights among many other factors (Weissenfels et al. 1990). Two major bioremediation schemes have been proposed, biostimulation and bioaugmentation (Miyasaka et al. 2006). Biostimulation is defined as addition of various forms of rate-limiting nutrients and electron acceptors such as phosphorus, nitrogen, oxygen, or carbon in order to increase the population or activity of naturally occurring microorganisms available for bioremediation. Bioaugmentation is the addition, to the polluted environment, of microorganisms that can biotransform or biodegrade contaminants. The added microorganisms can be new for the environment or already observed on site. These techniques of bioremediation provided contrasting results in PAH biodegradation depending on the type of PAH and the sediment composition (Yu et al. 2005).

Polycyclic aromatic compounds are hydrophobic and readily adsorbed onto particulate matter, therefore, sediments represent the ultimate sinks and elevated concentrations have been recorded in coastal environments (Hughes et al. 1997; James 2002). As many Mediterranean coastal lagoons, the Bizerte lagoon (Tunisia) is a polluted ecosystem subject to both urbanization and industrialization (cement works, metallurgical industry, boatyard, and tire production factories), as well as naval and commercial shipping harbors. Runoff and discharges of urban and industrial wastes lead to significant pollution of sediments by anthracene and others PAHs (Louiz et al. 2008; Trabelsi and Driss 2005), pollution that promotes to the co-selection of strains able to cope with multiple contaminants (Ben Said et al. 2010). The aim of the present study was firstly to investigate the behavior of microbial communities in response to low-dose bioavailable anthracene addition (1 ppm) in lightly contaminated (4 ppm) sediment from Bizerte Lagoon. Secondly, the effect of bioremediation treatments on microbial biomass, activity, and community structure was investigated. Bioremediation schemes tested included biostimulation and the combination of biostimulation and bioaugmentation by the inoculation of a marine PAH-degrading bacterium, Acinetobacter sp., previously isolated from Bizerte lagoon sediment.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Site description and sampling

Bizerte lagoon, the third important lagoon in Tunisia, is located in an economically important area in North Tunisia (Fig. 1). It is a 150 km² surface area depression known for its geostrategic position since it is connected to the Mediterranean Sea by a straight channel (Louiz et al. 2009). Sediment was collected by scuba diving from one site (Echaraà) located in the low-contaminated part of the lagoon (Ben Said et al. 2010; Trabelsi and Driss 2005). Handcores of 10 cm² were used to a depth of 15 cm to transfer sediment into a bucket. On return to the laboratory, sediments were homogenized by gentle hand stirring with a large spatula before microcosm setup and contamination. Buckets and spatula were all acid rinsed before use.

2.2 Microcosm set-up

Microcosms consisted of 1,600 ml glass bottles. One control and three treatments were setup. Contaminated microcosms (C) were gently filled with 200 g (wet weight) of homogenized sediment (100 g of natural sediment and 100 g contaminated sediment) topped up with 1 L of filtered (1 μm) natural lagoon water at 30 PSU. Sediment used for contamination was first alternately frozen (−80°C) and thawed three times to defaunate it (Gyedu-Ababio and Baird 2006), and then it was wet sieved to remove the larger particles (>63 μm). Stock solution of high purity anthracene (100 mg L−1; Sigma–Aldrich Chemical A8, 920–0), was dissolved in acetone. Next, 2 ml of the anthracene solution was added into the sediment slurry and shaken overnight to let the PAH adsorbed onto the sediments. Final concentration of anthracene in sediment was 1 ppm. Control consisted of uncontaminated and defaunated sediment (T). Each bottle was stoppered with a rubber bung with two holes and aerated via an air stone diffuser. Air flux was filtered on 0.2 μm to prevent contamination. All microcosms were performed in triplicates and incubated for 30 days in laboratory at room temperature (20–22°C).

Bioremediation treatments were started 1 day after anthracene contamination. Biostimulation (CBS) was achieved by amending two types of slow-release particle fertilizers 70 mg kg−1 of nitrogen fertilizer (NaNO3) and 35 mg kg−1 of phosphorus fertilizer (KH2PO4) using the protocol of Jacques et al. (2008). Biostimulation–bioaugmentation (CBS + BA): was achieved by adding the bacterium Acinetobacter sp. strain isolated from Bizerte-polluted sediments (Ben Said et al. 2008). The strain was previously grown in 50 ml of LB broth. After 1 week cultivation, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 15 min at 4°C. Cells were suspended in nutrient solution and introduced into the microcosms previously amended with nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer). The initial inoculum was 5.30 × 108 cell ml−1. After bacterium inoculation and nutrient addition, sediment was agitated for half an hour for homogenization.

2.3 Flow cytometry measurements

The method of bacteria extraction from sediment was derived from the protocol of Duhamel and Jacquet (2006). Sediment samples (1 g wet weight) were fixed with formalin (2 % final concentration) then 5 μl Tween 80 (10 %) + 1 ml sodium pyrophosphate solution (10 mM) + 4 ml MilliQ water were added. The samples were then sonicated three times for 1 min in a water bath and shaken manually after every minute. The samples were then centrifuged 1 min (800×g), filtrate supernatant on a 5-μm membrane and were diluted in TE-buffer 490 μl TE (prefiltered across 0.02 μm). For the enumeration of heterotrophic bacteria, cells were stained with the nucleic acid stain SYBR Green I (Marie et al. 1997). Working stocks of SYBR Green I (10−3 of the commercial solution, Molecular Probes) were freshly prepared on the day of analysis and then 2.6 % at final concentration of work solution was used to stain bacteria sample incubated at 4°C for 15 min before analysis. The stained bacterial cells, excited at 488 nm, were enumerated using side scatter and green fluorescence at 530 nm. Fluorescent beads (1 and 2 μm; Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA, USA) were added to each sample as an external standard. True count beads (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) were added to determine the volume analyzed. Samples were analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson), equipped with a 15 mW argon ion laser emitting at 488 nm for excitation. Data analyses were carried out with CellQuest Pro 5 software obtained from BD Biosciences.

2.4 Oxygen microsensor measurements

2.4.1 Oxygen microsensor

Oxygen concentration was measured using a Clark-type oxygen microelectrode (Revsbech 1989) manufactured by Unisense (Denmark). These Clark-type oxygen microsensors are largely used in microbial ecology studies and contain a guard electrode to prevent internal oxygen consumption (Revsbech 2005). The electrode had a 90 % response time lower than 1 s and a stirring sensitivity of 1 %. Oxygen microprofiles were performed with a depth resolution of 100 μm using a motor-driven micromanipulator. The oxygen microprobe was manually positioned at the sediment surface, profiling and data acquisition were then controlled by computer. Linear calibration of the microprobe was determined from the electrode readings in air-saturated water above the sediment and in the anoxic part of the sediment. Oxygen concentration in air-saturated water was calculated from the solubility equation according to Garcia and Gordon (1992).

2.4.2 Diffusive oxygen flux calculation

Diffusive oxygen fluxes (J) were calculated from the steady-state oxygen profiles using Fick’s first law of one-dimensional diffusion, written as (Eq. 1):

where Do denotes the oxygen diffusion coefficient in water (Broecker and Peng 1974), C is the oxygen concentration, z is the depth and δC(z)/δz the oxygen gradient in the diffusive boundary layer. Sediment oxygen consumption (SOC) was estimated from O2 flux in the diffusive boundary layer according to Rasmussen and Jorgensen (1992). Depth profiles of SOC were estimated by using the software PROFILE (Berg et al. 1998). In this procedure, the rate of net consumption as a function of depth was calculated from steady-state oxygen microprofiles. The procedure is based on a series of least square fits of the second Fick’s law to the measured steady-state oxygen profiles, followed by comparisons of these fits through statistical F testing. Thus, the simplest consumption profiles are objectively selected, which reproduce the measured concentration profiles within the chosen statistical accuracy. More details of the procedure can be found in Berg et al. (1998).

Porosity (ɸ) in the top millimeters was assumed to be constant and equal to 0.8. Sedimentary diffusion coefficient was estimated from Do according to the relation of Ullman and Aller (1982; Eq.2):

For each microcosm, SOC vertical profiles were based on three oxygen microprofiles that were measured after 4 and 30 days of incubation.

2.5 T-RFLP analysis

Mixed community DNA was extracted directly from sediment microcosms using an Ultra Clean® Microbial DNA Isolation DNA Kit (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) by following the manufacturer’s protocol. Genes encoding 16S rRNA were PCR amplified from extracted samples using primers 8F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1489R (5′-TACCTTGTTACGACTTCA-3′). Primer 8F was fluorescently labeled with 5-tetrachloro-fluorescein E.SG.C. (Cybergene Group, France). PCR and terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis were carried out as described previously (Ben Said et al. 2010) using the Taq DNA polymerase (Eurobio). The fluorescent PCR products were cleaned using GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification kit (Amersham-Pharmacia) and 10 μL of purified product was digested separately with 3 U of enzyme HaeIII and HinfI for 3 h at 37°C (New England Biolabs). One microliter of restriction digests were then mixed with 20 μL of deionized formamide and 0.5 μL of a TAMRA-labeled Gene scan 500 bp internal size standard (Applied Biosystems), denatured for 5 min at 95°C and immediately transferred to ice. Samples were loaded onto an ABI PRISM 310 automated genetic analyser (Applied Biosystems). T-RFLP profiles were aligned by identifying and grouping homologous fragments and normalized by calculating relative abundances of each terminal-restriction fragment (T-RF) from height fluorescence intensity of each T-RF as described in Pringault et al. (2008). For statistical analysis, T-RF heights of the three microcosm replicates were averaged.

2.6 Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (Kruskal–Wallis test) was used to test for overall differences between controls and treatments and the Tukey HSD multiple comparisons test was used in pairwise comparisons of treatments and control. In all the above statistical significance, testing a significant difference was assumed when p < 0.05. For the statistical analysis of bacterial community structure, relative abundances of T-RFs have been transformed with arcsin (× 0.5) according to Legendre and Legendre (1998) to get a normal distribution of the data. Correspondence analyses (CA) were then performed with MVSP v3.12d software (Kovach Computing Service, Anglesey, Wales).

3 Results

3.1 Bacterial abundance

Anthracene spiking resulted in significant differences in the benthic bacterial abundances relative to the control microcosms (Fig. 2). After 30 days of incubation, bacterial abundance in T microcosms averaged 4.57 ± 0.89 × 107 cells cm−3. Anthracene contamination had a strong impact on bacterial biomass which was significantly reduced in all contaminated microcosms. In C microcosms, bacterial abundance (1.56 ± 0.31 × 107 cells cm−3.) was almost three times lower than in T microcosms. Similar strong reduction was observed for CBS and CBS + BA microcosms. Interestingly, CBS and biostimulation coupled with bioaugmentation (CBS + BA) resulted in similar (p < 0.05) bacterial biomass relative to the C microcosms (1.79 ± 0.69 × 107 and 1.89 ± 0.73 × 107 cells cm−3, respectively; Fig. 2).

The cytograms of the T microcosms clearly showed three distinct populations on the basis of nucleic acid content (NA) and the side scatter: NA1 (82 ± 4 %), NA2 (10 ± 3 %), and NA3(8 ± 3 %) with a positive growth (Fig. 3). Anthracene contamination resulted in the strong reduction of NA2 (3 ± 2 %), indicating inhibition of the bacterial growth for this population. Interestingly, biostimulation as well as combination of biostimulation and bioaugmentation resulted in similar cytograms as those observed in C microcosms with dominance of two distinct populations (NA1 and NA3). Nevertheless, in CBS and CBS + BA microcosms, two subpopulations were observed in NA1, suggesting the presence of different populations as compared with the C microcosms. In addition, in all contaminated microcosms, the cytograms revealed high concentration of organic matter, indicating cell lysis induced by anthracene addition.

Cytograms in contour plot of bacterial populations in the different treatments (T uncontaminated, C contaminated, CBS biostimulation, CBS + BA biostimulation and bioaugmentation). The abscissa indicates the fluorescence intensity (FL 1) of cells stained with SYBR Green I. The ordinate indicates the relative granularity (side scatter) of cells. 1 and 2 μm calibration beads, TC Trucounts, NA nucleic acid

3.2 Sediment oxygen consumption

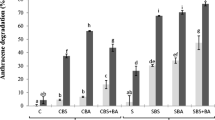

Oxygen consumption was measured 4 days after the microcosm settlement and after 30 days of incubation. At the beginning of the experiment, maximum oxygen penetration ranged from 0.22 to 0.38 cm, maximum penetration was observed in CBS + BA microcosms whereas minimum were observed in T microcosms (Fig. 4). Sediment oxygen consumption profiles were relatively similar in all microcosms, with a maximum value observed at the sediment surface and a second peak at the maximum oxygen penetration corresponding to the oxygen demand for the oxidation of reduced compounds. Areal sediment oxygen consumption rates (Fig. 5a) were similar in all microcosms with average rate of 1.25 nmol ± 0.28 O2 cm−2 min−1. After 30 days of incubation, oxygen penetrated deeper in the sediment irrespective of the treatment. In T microcosms, the maximum oxygen penetration averaged 0.6 cm, while for all contaminated microcosms oxygen penetration was significantly (p < 0.05) higher reaching 0.8 cm (Fig. 4). No significant difference was observed between contaminated microcosms. Interestingly, anthracene spiking resulted to a total inhibition of oxygen consumption at the sediment surface while for T microcosms surface activity was roughly similar as initially observed (0.14 vs. 0.12 nmol O2 cm−3 s−1, respectively). The strong inhibition of oxygen consumption by anthracene resulted to a significant decrease of sediment oxygen consumption (p < 0.05) relative both to the control (T) and to the rate measured at the beginning of the incubation (Fig. 5a). On average, rates measured at the end of incubation in anthracene microcosms represented only 25–30 % of the areal rates measured in T microcosms. As observed for bacterial biomass, both bioremediation treatments have no significant impact on oxygen consumption relative to the C microcosms; areal rates were not significantly different (Fig. 5a). Differences observed for sediment oxygen consumption between treatments were not explained by changes in total organic carbon since concentrations were roughly similar at the end of incubation in all microcosms (Fig. 5b).

Microprofiles oxygen (squares) and oxygen consumption (line) in the sediment of different treatments (T uncontaminated, C contaminated, CBS biostimulation, CBS + BA biostimulation and bioaugmentation). Solid squares and lines oxygen concentration and oxygen consumption after 4 days, respectively. Open squares and dotted lines oxygen concentration and oxygen consumption after 30 days incubation of microcosm, respectively

Sediment oxygen consumption and total organic carbon as a function of the different treatments (T uncontaminated, C contaminated, CBS biostimulation, CBS + BA biostimulation and bioaugmentation). a Oxygen fluxes at the sediment/water interface after 4 days (white bars) and 30 days (black bars) of incubation (average ± standard deviation). b Percentages of total organic carbon after 30 days of incubation (average ± standard deviation)

3.3 Bacterial community structure

At the end of incubation, T-RFLP profiles showed an average species richness (S) between 70 ± 10 and 85 ± 12 T-RFs (Fig. 2), the lowest was observed in anthracene-contaminated microcosms (C) while control microcosms (T) showed the highest (Fig. 2). The CA, based on T-RFLP fingerprints (Fig. 6), explaining more than 80 % of the distribution (53.3 and 27.5 % for axes 1 and 2, respectively) showed that bacterial communities from anthracene-contaminated microcosms were separated from the control according to axis 1 while the bacterial communities of the contaminated microcosms (C, CBS, CBS + BA) were distributed along axis 2. Among the different T-RFs observed, some T-RFs were detected in all microcosms with relative abundance >1 %, 33, 177, 192, 274 bp (HaeIII) and 116, 307, 331, 340 bp (HinfI). In contrast, relative abundance of specific T-RFs was subjected to changes as a function of the microcosm treatment. For example, T-RF 194 (HaeIII) showed a relative abundance of 5 % in anthracene microcosms while in T microcosms, its relative abundance was <1 %. In contrast, T-RF 269 (HaeIII) and 232 (HinfI) had a relative abundance >5 % in T microcosms and <1 % in anthracene microcosms, irrespective of the bioremediation treatment. Interestingly the T-RFs 255 (HaeIII) which could be related to members of the Acinetobacter genera, genera from which the strain added in the bioaugmentation treatment belongs, was found the most abundant in CBS + BA microcosms with a relative abundance of 2.1 % while it represented 0.3, 0.2, and 0.1 % in the C, CBS, and T microcosms, respectively.

Correspondence analysis (CA) of the microbial communities based on T-RFLP data (16S rRNA genes) as a function of the different treatments after 30 days of incubation (T uncontaminated, C contaminated, CBS biostimulation, CBS + BA biostimulation and bioaugmentation). The data analyzed correspond to the average for triplicate samples of HaeIII and HinfI-digested 16S rRNA genes yielding 5-end T-RFLP patterns

4 Discussion

Using a microcosm approach, we observed significant effects of anthracene on microbial biomass, activity and community structure despite the relative low concentration of anthracene added (1 ppm). Anthracene concentration in the studied sediment was around 4 ppm (unpublished results). As a consequence, the spiked concentration represented a small enrichment of the in situ concentration. Nevertheless, effects of this low contamination were obvious for the microbial community suggesting that the in situ anthracene contamination of the studied sediment did not allow the dominance of tolerant anthracene populations as it can be observed in polluted environments (Carman et al. 1995; Paisse et al. 2010). Impact of pollutant on benthic organisms depends on its bioavailability. A pollutant can be in high concentration in a polluted system but moderately impact the microbial community because of strong adsorption onto particles decreasing its potential toxic effects (Talley et al. 2002). Anthracene is largely associated with organic particles in sediments decreasing its bioavailability (Talley et al. 2002). Nevertheless, our results suggest that the low anthracene concentration added was sufficient to induce significant changes in biomass and structure suggesting thus that the spiked anthracene was bioavailable for microorganisms in the experimental conditions imposed.

Analysis by flow cytometry showed that anthracene had a significant effect on bacterial abundance with inhibition of the population NA2 identified from acid nucleic content (Fig. 3). The decrease in bacterial abundance can be explained by the inhibition of bacterial growth of non-adapted populations. In addition, cytograms of contaminated microcosms showed that cell integrity was strongly impacted. Anthracene is considered toxic, but toxicology data specific to anthracene is uncommon, or somewhat conflicting. Dean-Ross et al. (2001) state that anthracene is neither genotoxic nor carcinogenic, but is a threat to the environment because of its toxicity to aquatic life, especially through photo-induced toxicity which was confirmed by El-Alawi et al. (2002) who showed that anthracene is very toxic in the presence of ultraviolet radiation for luminescent bacteria. In the present study, the photo-toxicity of anthracene can be excluded because microcosms were incubated in laboratory conditions, under free UV and solar radiations. Therefore, we measured the direct toxicity of anthracene on indigenous bacteria in marine coastal sediments. Flores et al. (2010) observed growth inhibition upon anthracene contamination (IC50 6 ppm) of microbial consortium isolated from polluted sediments. They suggested that the toxic effects of anthracene is due to the accumulation and mutagenic activity of anthracene, similar to the effects induced by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on Salmonella strain YG1041 (Kummrow et al. 2006). Anthracene has a high octanol–water partition coefficient (log K ow = 4.1), and therefore can readily adsorb onto organic phases such as the phospholipids of bacterial membranes (Flores et al. 2010). This interaction provokes a hydrophobic region inside the bacterial membrane, which can act as a reservoir for anthracene accumulation (Bugg et al. 2000) enhancing its potential toxic effects.

Impact of anthracene on microbial biomass can also strongly change the sediment oxygen consumption since heterotrophic bacteria play a key role in the mineralization of the organic matter. The use of oxygen microelectrodes offers the possibility to determine with high-vertical resolution the sediment oxygen consumption, proxy of the organic matter mineralization under aerobic conditions (Viret et al. 2006). After 30 days of sediment contamination, anthracene had a strong impact on sediment oxygen consumption (Fig. 5) with a complete inhibition of the oxygen consumption in the first 5 mm (Fig. 4), the oxygen consumption observed around 8 mm depth corresponding to the oxygen demand (biotic and abiotic) for the oxidation of reduced compounds. Inhibition of sediment oxygen consumption was demonstrated for various pollutants such as atrazine (Laursen and Carlton 1999), metals (Viret et al. 2006), and uranium (Lagauzere et al. 2009). Interestingly, in the present study, the specific activity (activity/biomass) after 30 days of incubation was similar in all treatments (control and contaminated microcosms) although the biomass strongly decreased in contaminated microcosms concomitant with high reduction in bacterial population NA2 (Fig. 3). This suggests that the remaining microbial populations observed at the end of the incubations in the contaminated microcosms were in the same physiological state than those observed in the control. In contrast, Hjorth et al. (2007) observed an increase of the specific activity for the bacterio- and phytoplankton upon pyrene few days of exposure. For both compartments, abundance strongly decreased while activity remained stable. They suggest a functional redundancy to explain this increase of the specific activity. Effect of pyrene was strong enough to eliminate sensitive groups, living space and resources to more tolerant and/or opportunistic groups, which responded with high specific activities (Hjorth et al. 2007). In our study, even so, anthracene had a strong selective pressure by decreasing abundance of nontolerant population, it did not apparently alleviate the competition for space and resources since specific activities were the same in all microcosms (contaminated and control).

The toxic effects of anthracene observed on biomass and cell integrity is accompanied by strong changes in bacterial community structure (Fig. 6) and in moderate decrease of species richness (Fig. 2). T-RFLP profiles revealed an important bacterial diversity in all microcosms as previously reported in marine sediments (Ben Said et al. 2010). The correspondence analysis, based on T-RFLP fingerprints (Fig. 6) showed that bacterial communities from anthracene-contaminated microcosms were separated from the control. Bacterial community structure changes as response to PAH addition have been often observed using a single molecule, e.g., anthracene (Zhang et al. 2011), phenanthrene (Muckian et al. 2009), or a complex mixture of PAH (Zhou et al. 2009). Changes in hydrocarbon content resulted in characteristic shifts of substrate utilization patterns which can correspond to similar changes in abundance of hydrocarbon-utilizing bacteria and the occurrence of specific bacterial groups (Wunsche et al. 1995). Interestingly, at the end of incubation, the T-RF 194 (HaeIII) was observed in abundance >5 % in the contaminated microcosms while its relative abundance was <1 % in the control. According to the Ribosomal Database Project, this T-RF may correspond to an uncultured Proteobacterium frequently observed in PAH-contaminated environments (e.g., Paisse et al. 2010). It is likely that the dominance of this population could be attributed to the selective pressure exerted by anthracene and its degradation metabolites. The selective pressure can also result to the diminution of nontolerant populations as observed for the T-RFs 269 (HaeIII) and 232 (HinfI) for which a strong decrease of the relative abundance was observed in anthracene microcosms relative to the control.

Overall, the present study shows that addition of a low dose of anthracene strongly modified biomass, structure and function of the microbial community. Bioremediation using addition of fertilizers (CBS) and/or addition of hydrocarbonoclast bacteria (BA) can be attractive solutions to enhance degradation of organic pollutants, decreasing thus their potential toxic effects. Irrespective of the bioremediation treatments, the toxic effects of anthracene could not be diminished for microbial biomass, structure and function. Unfortunately, anthracene concentration was not measured at the end of incubation, nevertheless, the observed patterns clearly suggest that its toxic effects were still present after 30 days of incubation in both CBS and CBS + BA microcosms. Yu et al. (2005) observed that biostimulation and bioaugmentation are not always efficient in PAH biodegradation which can be explained by the bioavailability of PAHs and the competition between species for organic and inorganic substrates. In our study, the enrichment in nutrients (N and P) followed the protocols of Jacques et al. (2008) and represented an N/P ratio of 4. The cytograms of the CBS microcosms observed at the end of the incubations showed the presence of two subpopulations in the NA1 population (Fig. 3). These subpopulations were not observed in the C and T microcosms. This stimulation of these subpopulations was followed by a moderate change of the microbial community structure relative to the contaminated sediment (Fig. 6). The Bizerte lagoon exhibits N/P ratio around 2.5 in winter and around 20 in summer, suggesting different nutrient limitation for each season, N limitation in winter and P limitation in summer (Hlaili et al. 2006). According to the Redfield ratio, the N/P ratio used for the biostimulation should alleviate a P limitation. The presence of two subpopulations in NA1 population specific to CBS and CBS + BA microcosms suggests that the nutrient amendment partly alleviated P limitation resulting to different microbial community structures (Fig. 6) as also observed in other bioaugmentation studies (Di Gennaro et al. 2009; Miyasaka et al. 2006). However, this nutrient stimulation did not compensate the toxic effects of anthracene since total biomass and sediment oxygen consumption were similar in CBS and C microcosms. This noncompensation of the anthracene toxic effects was also observed when a hydrocarbonoclastic bacterium (Acinetobacter sp.) was inoculated together with the nutrients. The strain used for the bioaugmentation was isolated from contaminated sediments of Bizerte lagoon and was chosen for its capacities to degrade hydrocarbons (Ben Said et al. 2008). The analysis of microbial community by T-RFLP fingerprints indicated that the T-RF255 (HaeIII) corresponding to this bacterium species had a relative abundance of >2 % in the CBS + BA microcosms while in other microcosms its relative abundance was <0.3 %. This suggests that the experimental conditions imposed favored the growth of Acinetobacter sp.; however, its potential hydrocarbon degradation capacities did not alleviate the toxic effects of anthracene. This might be due to the competition for resources as suggested by Yu et al. (2005) to explain the absence of effective biodegradation with bioaugmentation treatments as it is often reported (e.g., Perelo 2010). The fact that specific activities were similar in all treatments (see above) suggests that anthracene did not alleviate competition between microorganisms, which would support this hypothesis.

5 Conclusion

Using a microcosm approach, we showed that a low dose of anthracene (1 ppm) severely affect the microbial community, biomass, structure, and function in a sediment slightly contaminated by anthracene, suggesting the dominance of nontolerant microbial populations. The toxic effects of anthracene were not alleviated when bioremediation treatments, biostimulation, and/or bioaugmentation were used even so changes in microbial populations and structures were observed, suggesting that the proposed treatments might be promising to promote bacterial growth but further works are still required to propose a more efficient strategy to stimulate biodegradation that takes into account the complex interactions between species for resource access.

References

Atagana HI (2006) Biodegradation of polyacyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in contaminated soil by biostimulation and bioaugmentation in the presence of copper(II) ions. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 22:1145–1153

Bauer JE, Capone DG (1985) Degradation and mineralization of the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons anthracene and naphthalene in intertidal marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 50:81–90

Ben Said O, Goni-Urriza MS, El Bour M, Dellali M, Aissa P, Duran R (2008) Characterization of aerobic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria from Bizerte lagoon sediments, Tunisia. J Appl Microbiol 104:987–997

Ben Said O, Goni-Urriza M, El Bour M, Aissa P, Duran R (2010) Bacterial community structure of sediments of the Bizerte Lagoon (Tunisia), a Southern Mediterranean Coastal Anthropized Lagoon. Microb Ecol 59:445–456

Berg P, Risgaard-Petersen N, Rysgaard S (1998) Interpretation of measured concentration profiles in sediment pore water. Limnol Oceanogr 43:1500–1510

Bowling JW, Leversee GJ, Landrum PF, Giesy JP (1983) Acute mortality of anthracene-contaminated fish exposed to sunlight. Aquat Toxicol 3:79–90

Brenner RC, Magar VS, Ickes JA, Abbott JE, Stout SA, Crecelius EA, Bingler LS (2002) Characterization and FATE of PAH-contaminated sediments at the Wyckoff/Eagle Harbor superfund site. Environ Sci Technol 36:2605–2613

Bridges TS, Levin LA, Cabrera D, Plaia G (1994) Effects of sediment amended with sewage, algae, or hydrocarbons on growth and reproduction in 2 opportunistic polychaetes. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 177:99–119

Broecker WS, Peng TH (1974) Gas exchange rates between air and sea. Tellus 26:21–35

Bugg T, Foght JM, Pickard MA, Gray MR (2000) Uptake and active efflux of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by Pseudomonas fluorescens LP6a. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:5387–5392

Carman KR, Fleeger JW, Means JC, Pomarico SM, McMillin DJ (1995) Experimental investigation of the effects of polynuclear aromatic-hydrocarbons on an estuarine sediment food web. Mar Environ Res 40:289–318

Dabestani R, Ivanov IN (1999) A compilation of physical, spectroscopic and photophysical properties of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Photochem Photobiol 70:10–34

Dean-Ross D, Moody JD, Freeman JP, Doerge DR, Cerniglia CE (2001) Metabolism of anthracene by a Rhodococcus species. FEMS Microbiol Lett 204:205–211

Di Gennaro P, Moreno B, Annoni E, Garcia-Rodriguez S, Bestetti G, Benitez E (2009) Dynamic changes in bacterial community structure and in naphthalene dioxygenase expression in vermicompost-amended PAH-contaminated soils. J Hazard Mater 172:1464–1469

Duhamel S, Jacquet S (2006) Flow cytometric analysis of bacteria- and virus-like particles in lake sediments. J Microbiol Methods 64:316–332

El-Alawi YS, Dixon DG, Greenberg BM (2001) Effects of a pre-incubation period on the photoinduced toxicity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to the luminescent bacterium Vibrio fischeri. Environ Toxicol 16:277–286

El-Alawi YS, McConkey BJ, Dixon DG, Greenberg BM (2002) Measurement of short- and long-term toxicity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons using luminescent bacteria. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 51:12–21

Flores GP, Badillo CM, Cortazar MH, Hipolito CN, Perez RS, Sanchez IG (2010) Toxic effects of linear alkylbenzene sulfonate, anthracene and their mixture on growth of a microbial consortium isolated from polluted sediment. Rev Int Contam Ambient 26:39–46

Garcia HE, Gordon LI (1992) Oxygen solubility in seawater—better fitting equations. Limnol Oceanogr 37:1307–1312

Gyedu-Ababio TK, Baird D (2006) Response of meiofauna and nematode communities to increased levels of contaminants in a laboratory microcosm experiment. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 63:443–450

Hjorth M, Vester J, Henriksen P, Forbes V, Dahllof I (2007) Functional and structural responses of marine plankton food web to pyrene contamination. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 338:21–31

Hlaili AS, Chikhaoui MA, El Grami B, Mabrouk HH (2006) Effects of n and p supply on phytoplankton in Bizerte Lagoon (western Mediterranean). J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 333:79–96

Hughes JB, Beckles DM, Chandra SD, Ward CH (1997) Utilization of bioremediation processes for the treatment of PAH-contaminated sediments. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 18:152–160

Jacques RJS, Okeke BC, Bento FM, Teixeira AS, Peralba MCR, Camargo FAO (2008) Microbial consortium bioaugmentation of a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons contaminated soil. Biores Technol 99:2637–2643

James ID (2002) Modelling pollution dispersion, the ecosystem and water quality in coastal waters: a review. Environ Model Softw 17:363–385

Kochevar IE, Armstrong RB, Einbinder J, Walther RR, Harber LC (1982) Coal–tar photo-toxicity—active compounds and action spectra. Photochem Photobiol 36:65–69

Kummrow F, Rech CM, Coimbrao CA, Umbuzeiro GA (2006) Blue rayon-anchored technique/Salmonella microsome microsuspension assay as a tool to monitor for genotoxic polycyclic compounds in Santos estuary. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 609:60–67

Lagauzere S, Pischedda L, Cuny P, Gilbert F, Stora G, Bonzom JM (2009) Influence of Chironomus riparius (Diptera, Chironomidae) and Tubifex tubifex (Annelida, Oligochaeta) on oxygen uptake by sediments. Consequences of uranium contamination. Environ Pollut 157:1234–1242

Laursen AE, Carlton RC (1999) Responses to atrazine of respiration, nitrification, and denitrification in stream sediments measured with oxygen and nitrate microelectrodes. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 29:229–240

Legendre P, Legendre L (1998) Numerical ecology. Elsevier, Amesterdam

Long ER (1992) Ranges in chemical concentrations in sediments associated with adverse biological effects. Mar Pollut Bull 24:38–45

Louiz I, Kinani S, Gouze ME, Ben-Attia M, Menif D, Bouchonnet S, Porcher JM, Ben-Hassine OK, Ait-Aissa S (2008) Monitoring of dioxin-like, estrogenic and anti-androgenic activities in sediments of the Bizerta lagoon (Tunisia) by means of in vitro cell-based bioassays: Contribution of low concentrations of polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Sci Total Environ 402:318–329

Louiz I, Ben-Attia M, Ben-Hassine OK (2009) Gonadosomatic index and gonad histopathology of Gobius niger (Gobiidea, Teleost) from Bizerta lagoon (Tunisia): evidence of reproduction disturbance. Fish Res 100:266–273

Marie D, Partensky F, Jacquet S, Vaulot D (1997) Enumeration and cell cycle analysis of natural populations of marine picoplankton by flow cytometry using the nucleic acid stain SYBR Green I. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:186–193

McConkey BJ, Duxbury CL, Dixon DG, Greenberg BM (1997) Toxicity of a PAH photooxidation product to the bacteria Photobacterium phosphoreum and the duckweed Lemna gibba: effects of phenanthrene and its primary photoproduct, phenanthrenequinone. Environ Toxicol Chem 16:892–899

Miyasaka T, Asami H, Watanabe K (2006) Impacts of bioremediation schemes on bacterial population in naphthalene-contaminated marine sediments. Biodegradation 17:227–235

Muckian LM, Grant RJ, Clipson NJW, Doyle EM (2009) Bacterial community dynamics during bioremediation of phenanthrene- and fluoranthene-amended soil. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 63:52–56

Mueller JG, Chapman PJ, Pritchard PH (1989) Creosote-contaminated sites—their potential for bioremediation. Environ Sci Technol 23:1197–1201

Myers CR, Alatalo LJ, Myers JM (1994) Microbial potential for the anaerobic degradation of simple aromatic compounds in sediments of the Milwaukee Harbor, Green Bay and Lake Erie. Environ Toxicol Chem 13:461–471

Nance JM (1991) Effects of oil gas-field produced water on the macrobenthic community in a small gradient estuary. Hydrobiologia 220:189–204

Paisse S, Goni-Urriza M, Coulon F, Duran R (2010) How a bacterial community originating from a contaminated coastal sediment responds to an oil input. Microb Ecol 60:394–405

Perelo LW (2010) Review: in situ and bioremediation of organic pollutants in aquatic sediments. J Hazard Mater 177:81–89

Pringault O, Duran R, Jacquet S, Torreton JP (2008) Temporal variations of microbial activity and diversity in marine tropical sediments (New Caledonia lagoon). Microb Ecol 55:247–258

Rasmussen H, Jorgensen BB (1992) Microelectrode studies of seasonal oxygen uptake in a coastal sediment—role of molecular diffusion. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 81:289–303

Revsbech NP (1989) An oxygen microsensor with a guard cathode. Limnol Oceanogr 34:474–478

Revsbech NP (2005) Analysis of microbial communities with electrochemical microsensors and microscale biosensors, environmental microbiology. Methods in enzymology. Elsevier, San Diego, pp 147–166

Samanta SK, Singh OV, Jain RK (2002) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: environmental pollution and bioremediation. Trends Biotechnol 20:243–248

Tahir A, Fletcher TC, Houlihan DF, Secombes CJ (1993) Effect of short-term exposure to oil-contaminated sediments on the immune response of dab, Limanda limanda (L). Aquat Toxicol 27:71–82

Talley JW, Ghosh U, Tucker SG, Furey JS, Luthy RG (2002) Particle-scale understanding of the bioavailability of PAHs in sediment. Environ Sci Technol 36:477–483

Tam NFY, Ke L, Wang XH, Wong YS (2001) Contamination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface sediments of mangrove swamps. Environ Pollut 114:255–263

Trabelsi S, Driss MR (2005) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in superficial coastal sediments from Bizerte Lagoon, Tunisia. Mar Pollut Bull 50:344–348

Ullman WJ, Aller RC (1982) Diffusion coefficients in nearshore marine sediments. Limnol Oceanogr 27:552–556

Viret H, Pringault O, Duran R (2006) Impact of zinc and nickel on oxygen consumption of benthic microbial communities assessed with microsensors. Sci Total Environ 367:302–311

Weissenfels WD, Beyer M, Klein J (1990) Degradation of phenanthrene, fluorene and fluoranthene by pure bacterial cultures. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 32:479–484

Wunsche L, Bruggemann L, Babel W (1995) Determination of substrate utilization patterns of soil microbial communities—an approach to assess population-changes after hydrocarbon pollution. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 17:295–305

Yu KSH, Wong AHY, Yau KWY, Wong YS, Tam NFY (2005) Natural attenuation, biostimulation and bioaugmentation on biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in mangrove sediments. Mar Pollut Bull 51:1071–1077

Zhang SY, Wang QF, Xie SG (2011) Microbial community changes in contaminated soils in response to phenanthrene amendment. Int J Environ Sci Technol 8:321–330

Zhou HW, Wong AHY, Yu RMK, Park YD, Wong YS, Tam NFY (2009) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-induced structural shift of bacterial communities in mangrove sediment. Microb Ecol 58:153–160

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a funding of the CMCU (n° 09G 0189) and PHC-Utique (20894TE) programs, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS/DGRST n°22629), and the Ministère Tunisien de la Recherche scientifique.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor Philippe Garrigues

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Louati, H., Said, O.B., Got, P. et al. Microbial community responses to bioremediation treatments for the mitigation of low-dose anthracene in marine coastal sediments of Bizerte lagoon (Tunisia). Environ Sci Pollut Res 20, 300–310 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-012-0860-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-012-0860-x