Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to evaluate the care receiver's satisfaction with the continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) interfaces.

Methods

A questionnaire with visual analog scales was sent to all our CPAP patients (0 = absolutely unsatisfied, 100 = very satisfied). From the ResMed ResScan program, we obtained the CPAP daily use and air leak values.

Results

We received 730 answers (70 % of participants); females comprised 22 %. A total of 391 patients had ResMed interfaces, 227 had Respironics, 87 had Fisher & Paykel (F&P), and 25 patients had other interfaces. Interfaces were nasal for 79 %, nasal pillows for 9 %, oronasal for 9 %, and unidentified for 3 % of cases. The mean ± SD satisfaction rate was 68 ± 25. No statistically significant differences were found regarding the type or brand of interface, previous interface experience, or the age or gender of the patient. Users of ResMed interfaces had significantly (p < 0.01) fewer cases of disturbing leaks than did users of Respironics or F&P interfaces (60 vs. 70 and 72 %, respectively). The ResMed Ultra Mirage interface had the fewest cases of disturbing leaks. Values for the measured median leaks were a mean of 5.9 ± 7.2 l/min, and those for the maximum leaks were 39.3 ± 22.2 l/min with no differences between brands. The users of F&P interfaces experienced significantly (p < 0.01) more comfort and used the CPAP device significantly (p < 0.007) more than did users of ResMed or Respironics interfaces (88 % of cases vs. 65 and 57 % and 6.2 ± 2.6 vs. 5.3 ± 2.8 or 5.8 ± 2.8 h/day, respectively).

Conclusions

The majority of patients consider the use of the CPAP interface disturbing even though the satisfaction rate is good with no differences between brands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

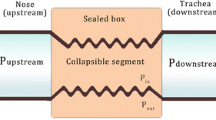

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), an effective treatment for sleep apnea [1, 2], consists of a pump which blows air into a patient's nose and/or mouth during sleep to hold and open the airways and to stop obstructions from occurring. The pump is connected to the patient via a connecting hose and an “interface” which rests on the patient's face. Types of interface available for CPAP use include masks which fit into the nostrils (nasal pillows) or which cover the nose (nasal mask), the mouth, both the nose and mouth (oronasal), or even the entire face. Local side effects, such as pressure sores, skin ulceration, air leaks, mask dislodgement, claustrophobia, or local allergic reactions, occur in up to 50 % of patients [3, 4].

Adherence to CPAP therapy in the community has shown rates ranging from 65 to 88 % [4–6]. Recently, air leaks were reported to be associated with poor adherence [7]. The intrusive nature of CPAP therapy into the sanctity of the bedroom and the natural aversion to wearing unattractive headgear to bed have often been cited as the reasons for nonadherence [8]. Despite numerous improvements in the technology of CPAP interfaces and devices, however, the major challenge for physicians is to increase acceptance of and adherence to this treatment [9]. Moreover, either the progressive changes in mask type improve adherence or are simply a reflection of marketing strategies remains unclear [8].

The choice of interface for a particular person must be tailored to the individual. Proper mask fitting and patient education are important and may lead to fewer air leaks, better adjustment of the mask, and improved adherence to treatment [4]. Nasal pillows may be useful alternatives when a patient is unable to tolerate conventional nasal masks [10]. Nevertheless, there is no evidence of the superiority of nasal pillows over conventional nasal masks [10]. An oronasal mask may be considered if nasal obstruction or dryness limits the use of a nasal mask [11].

Given the numbers of CPAP masks used worldwide, it is surprising to note the lack of properly powered, randomized superiority or equivalence studies comparing interfaces [11]. The choice of the right interface often depends on the experience of the sleep nurse, the feedback of the care receiver, and the availability of the desired interfaces. The increasing number of CPAP patients and the need to replace the interface regularly add more pressure to the already overloaded medical costs. Choosing suitable CPAP interfaces therefore requires some selection criteria. We used a questionnaire to evaluate the care receiver's opinion about CPAP interfaces and their side effects.

Methods

Subjects and questionnaire

We sent a questionnaire to all our patients who are followed up for CPAP therapy for more than 3 weeks. Visual analog scales served to determine patient satisfaction levels with their CPAP interface (Table 1). We inquired about the frequency of side effects and the presence of a disturbing factor, such as beard, moustaches, or eyeglasses. We also asked the patients to report their mean daily CPAP use and to write suggestions for a better interface.

CPAP device and CPAP interfaces

All patients underwent a 1-h familiarization session at the hospital with the CPAP device and masks, as previously described [12]. Later, masks were also adjusted or changed when problems occurred.

The brand and type of the CPAP interfaces are chosen in our sleep units every 2 years, according to local legislation. Since the year 2004, we have used only CPAP devices from ResMed (ResMed Corp. San Diego, CA, USA), whereas previously, we used interfaces from different manufacturers to broaden the selection and to reduce the cost. We used ResMed, Fisher & Paykel (F&P) (Healthcare Limited, New Zealand), and Philips Respironics (Respironics, Inc., Murrysville, PA, USA) interfaces. National public health insurance fully covers the cost of CPAP devices and interfaces delivered to our patients.

Adherence and CPAP use

From the program provided by the manufacturer, we obtained the CPAP daily use in hours and the median and maximum values of unintentional air leaks in liters per minute. Patients were also asked to estimate their mean CPAP daily use in hours and minutes.

Statistics

For descriptive purposes, we reported values as means, standard deviation, and range. We used the Mann–Whitney test and the Student's t test for continuous variables, the χ 2 test for categorical variables, and a Spearman rank correlation for correlation analysis. Results were generated using a computerized statistical package (IBM SPSS® Statistics 19.0, Armonk, NY, USA). All p values are two-sided, and the significance level was set at 0.05 throughout. The local ethics committee approved the study, and the participants provided their written informed consent.

Results

We sent 1,043 questionnaires and received 730 answers, yielding a participating rate of 70 %; females constituted 22 % of the participants. The mean ± SD age was 58 ± 12 years (range 21–88 years) and the mean duration of CPAP therapy was 696 ± 676 days (range 23–5,849 days) (Fig. 1).

A total of 391 patients had ResMed interfaces, 227 had Respironics, 87 had F&P, and 25 patients had other interfaces. Nasal interfaces constituted 79 % of all interfaces, nasal pillows 9 %, oronasal interfaces 9 %, and in 3 % of cases, the type of interface was not identified (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

A total of 287 (43 %) patients had previously used another interface for at least one night. Actual users of F&P interfaces had used significantly (p < 0.002) more previous masks than did users of ResMed and Respironics interfaces (60 vs. 43 and 35 %, respectively).

The mean satisfaction rate for all interfaces was 68 ± 25. No statistically significant differences were found regarding the type or brand of the interface, previous interface experience, or the age or gender of the patient.

Disturbing leaks and measured leaks

A total of 454 patients (65 %) reported that leaks frequently disturb them. Users of ResMed interfaces had significantly (p < 0.01) fewer cases of disturbing leaks than did users of Respironics or F&P interfaces (60 vs. 70 and 72 %, respectively; Fig. 2). Moreover, cases of disturbing leaks were significantly (p < 0.05) less frequent in Ultra Mirage interface users than in other ResMed interface users (54 vs. 65 %, respectively).

Values of the measured median leaks were a mean of 5.9 ± 7.2 l/min, and that of the maximum leaks, a mean of 39.3 ± 22.2 l/min. We found no significant difference in values of the measured median or maximum leaks between interface brands or between patients who reported disturbing leaks and those who did not or in those with or without a moustache.

Local skin problems

The CPAP interface left a morning print on the face at 53 ± 33 (0 = never, 100 = everyday), meaning that about half of patients have a morning print every other day. Users of F&P interfaces experienced significantly (p < 0.001) more morning prints than did users of ResMed or Respironics interfaces (69 vs. 50 and 53, respectively). We found no significant difference in the presence of a morning print between the different types of interfaces and no correlation between the presence of a morning print and the age or gender of the patient.

We observed that 48 % of users experienced CPAP interface pressure on the skin. Users of the oronasal mask reported significantly (p < 0.01) more pressure on the skin than did users of other interfaces (65 vs. 46 % of cases). We found no statistically significant difference in interface pressure on the skin between the different brands.

As many as 20 % of patients reported that the CPAP interface caused minor skin lesions, although we found no statistically significant differences between CPAP brands or types of interface. The most common site of skin lesions was on the lateral sides of the nose (32 % of cases), followed by the nasal bridge (23 %) and the lower part of the nasal area (21 %; Fig. 3).

Comfort of CPAP interface

A total of 20 % of the men in our study have moustaches with no beard, and 34 % have both a beard and a moustache; 88 % of these patients reported that their beard or moustache disturbed their use of the CPAP interface. Wearing eyeglasses was reported to disturb the use of CPAP devices in 15 % of patients. Females were significantly (p < 0.05) more disturbed by their eyeglasses than were males (22 vs. 14 %, respectively), yet we found no correlation between the type of the interface and the disturbance caused by the eyeglasses.

Altogether 30 % of patients found their interface uncomfortable, mainly because of a poorly fitting, bulky, or unstable interface (38 % of cases). Straps were the second major cause (18 % of cases), followed by the noise of the air turbulence of the CPAP device (9 %).

Significantly (p < 0.01) more users of the F&P interfaces than users of the ResMed or Respironics interfaces felt their interfaces were more comfortable (88 % of patients vs. 65 and 57 %, respectively). We found no statistical differences regarding the type of interface.

Sleep habits

A total of 23 % of patients reported that the use of their CPAP devices has completely modified their sleep habits, 21 % experienced important modifications, 14 % moderate modifications, and 42 % experienced few or no modifications in their sleep habits. As many as 26 % of patients reported that their use of the CPAP interface has completely modified their sleep position, 26 % experienced important modifications, 16 % moderate modifications, and 32 % experienced few or no modifications in their sleep position.

CPAP device and CPAP use

All of our patients used ResMed CPAP devices, and 397 patients (54 %) used Autoset S7 or Autoset S8 devices with the automatic pressure function. A total of 333 (46 %) patients used CPAP fixed-pressure devices, 297 (41 %) used Escape, 31 (4 %) used S7, and 7 (1 %) patients used Elite CPAP devices. The 95th CPAP pressure was a mean of 10.4 ± 2.2 cmH2O.

Patients significantly (p < 0.01) overestimated their CPAP daily use at a mean of 6.8 ± 1.5, whereas the mean daily use measured was 5.6 ± 2.8 h, yielding an overestimation of 1.2 h/day. Users of nasal interfaces used their CPAP daily significantly (p < 0.001) more than did users of nasal pillow or oronasal interfaces (5.8 ± 2.8 vs. 4.7 ± 3.2 or 4.7 ± 2.8 h, respectively). Users of F&P interfaces used their CPAP devices daily significantly (p < 0.007) more often than did users of ResMed or Respironics interfaces (6.2 ± 2.6 vs. 5.3 ± 2.8 or 5.8 ± 2.8 h, respectively). We found no statistically significant correlation between the reported CPAP daily use and the satisfaction rate with the CPAP interface.

Suggestions

Patients offered suggestions to improve the CPAP interfaces. They proposed better and more adjustable straps (38 % of suggestions), a more personalized mask to fit the shape of the face more closely (30 %), a skin-friendly interface (13 %), a robust and easy-to-assemble interface (9 %), and finally, a lighter mask (9 %).

Discussion

Patients were generally satisfied with their CPAP interfaces. We found no significant differences in the CPAP interface satisfaction rate between users of ResMed, Respironics, or F&P devices. Given the wide choice of CPAP interfaces and the increasing numbers of users worldwide, our findings seem useful.

Studying satisfaction is difficult, as 18 % of patients are described as “difficult” and “unsatisfied” [13]. We found that the major cause of discomfort for an interface was poor fit, bulkiness, or instability; uncomfortable straps were the next major cause. We noticed that the users of F&P interfaces consider their interfaces significantly more comfortable than do users of other brands. It is also worth noting that F&P users had previously tried significantly more masks than did users of other brands.

Our findings agree with those of Kakar et al. [3] in that CPAP therapy is perceived as uncomfortable and constraining. We found that the presence of leaks disturbed more than half of our patients, about half experienced morning print, and one fifth suffered from minor skin lesions. Despite these inconveniences, the daily CPAP use was high (exceeding 4 h). We may think that the presence of uncomfortable tools, such as CPAP, hampers good adherence, and that more “comfort” leads to better adherence. Effectively, this conclusion is questionable. Although the treatment of arterial hypertension is relatively easier and more comfortable than CPAP therapy, arterial hypertension treatment has far-from-good adherence. Moreover, it is less than optimal, as outcomes with arterial hypertension treatment failed to reach their target [14]. Accordingly, we found no correlation between our patients' satisfaction rates and daily CPAP use.

Our patients overestimated their CPAP daily use by more than 1 h, which is consistent with the results of previous studies [15, 16]. Few papers have compared CPAP interfaces, although CPAP devices and their algorithms have been widely studied [17].

Our findings disagree with the recent results of Teo et al. [18], which found that nasal masks were more comfortable and were associated with fewer leaks than were oronasal masks, in that we found no differences between oronasal masks and nasal masks with regard to comfort or leaks; they effectively excluded subjects with previous oronasal operations as well as patients with a history of clinically severe nasal or sinus disease. Meanwhile, we found that users of nasal masks had higher CPAP daily use than did users of other interfaces. Massie et al. [19] used different nasal pillows from those used in this study and found no differences in CPAP daily use between nasal masks and nasal pillows.

More than half or our patients experienced continuously disturbing leaks. This disturbance did not correlate to the size of the measured leak. In fact, unintentional air leaks may appear in cases of a poorly fitting mask, defective tubing, unsealing circuit, and an open mouth. A substantial leak may go unnoticed by the patient; alternatively, a small leak blowing on a sensitive area, such as the eye, may disturb considerably. Although their measured median and maximum leaks did not differ from those of users of the other interface brands, users of ResMed interfaces nevertheless experienced fewer cases of disturbing leaks. Among the ResMed interfaces, the Ultra Mirage mask was the best in terms of the absence of disturbing leaks; the Ultra Mirage mask features an adjustable forehead portion that may prevent possible leaks from blowing on the eyes.

CPAP therapy has changed our patients' sleep habits and sleep positions. The CPAP interface may be especially cumbersome when sleeping in the prone position.

About one third of our men have moustaches, and most of them (men with moustaches) felt their moustaches disturbed their use of the CPAP interface. Masks are effectively designed to relay on the skin without interference. Some men lighten their moustaches, but the majority prefer to keep them despite the inconvenience. Surprisingly, measured and reported disturbing leaks showed no differences regardless of whether the patient has a moustache. In fact, we interfered early to minimize leaks, which may explain our findings.

We found no correlation between the type of interface and the disturbance caused by eyeglasses. In fact, we often propose nasal pillows when patients wish to use their eyeglasses while their CPAP device is on. Eyeglasses significantly disturb women more than men, probably because women read more than men do.

More than half of our patients suffered from a morning print every other day. Users of F&P interfaces experienced significantly more morning prints than did users of ResMed or Respironics interfaces. A morning print is the consequence of the continuous application of pressure caused by the mask or straps. The applied pressure locally reduces the edema, and the print takes the shape of the mask or straps. The print appears when the mask is removed in the morning. Any fluid that has accumulated in the lower extremities while standing upright during the day could shift rostrally into the neck and face on assuming the recumbent position during sleep. Such fluid displacement could cause distension of the great veins and/or edema [20, 21]. The amount of displaced fluid could explain the degree of edema, but the amount of applied pressure explains the increased prevalence of the morning print among F&P interface users.

The limitations of this study are that it is descriptive and based on a questionnaire. Moreover, our nurses proposed to the patients a “suitable” interface that may well have been proportional to the drive and enthusiasm of the local company representative. In addition, we tried to anticipate problems and propose solutions on an individual basis. Taking into consideration these limitations, we present the finding that daily CPAP use among F&P interface users was significantly higher than that of users of other brands. Moreover, the rapid turnover of the CPAP interfaces and the continuous arrival of new models give the impression that the models used in this study are relatively old [22]. We also noticed that the designs and materials of the interface have improved considerably in order to reduce discomfort. In fact, severe skin ulceration is nowadays rare [23].

We conclude that CPAP patients were satisfied with their interfaces despite the presence of several inconveniences. Moreover, we found no significant differences in the total satisfaction rate between users of ResMed, Respironics, or F&P interfaces.

References

Jenkinson C, Davies RJ, Mullins R, Stradling JR (1999) Comparison of therapeutic and sub-therapeutic nasal continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized prospective parallel trial. Lancet 353:2100–2105

Corda L, Redolfi S, Montemurro LT, La Piana GE, Bertella E, Tantucci C (2009) Short- and long-term effects of CPAP on upper airway anatomy and collapsibility in OSAH. Sleep Breath 13:187–193

Kakkar RK, Berry RB (2007) Positive airway pressure treatment for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 132:1057–1072

Pepin JL, Leger P, Veale D, Langevin B, Robert D, Lévy P (1995) Side effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure in sleep apnea syndrome: study of 193 patients in two French sleep centers. Chest 107:375–381

Sin DD, Mayers I, Man GC, Pawluk L (2002) Long-term compliance rates to continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea: a population-based study. Chest 121:430–435

Bachour A, Maasilta P (2004) Mouth breathing compromises adherence to nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Chest 126:1248–1254

Valentin A, Subramanian S, Quan SF, Berry RB, Parthasarathy S (2011) Air leak is associated with poor adherence to autoPAP therapy. Sleep 34:801–806

Weaver TE, Grunstein RR (2008) Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: the challenge to effective treatment. Proc Am Thorac Soc 5:173–178

Berry RB (2000) Improving CPAP compliance—man more than machine. Sleep Med 1:175–178

Ryan S, Garvey JF, Swan V, Behan R, McNicholas WT (2011) Nasal pillows as an alternative interface in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome initiating continuous positive airway pressure therapy. J Sleep Res 20:367–373

Chai CL, Pathinathan A, Smith BJ (2006) Continuous positive airway pressure delivery interfaces for obstructive sleep apnoea. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Issue 4. Art. no.: CD005308

Bachour A, Virkkala J, Maasilta P (2007) AutoCPAP initiation at home: optimal trial duration and cost-effectiveness. Sleep Med 8:704–710

Hinchey SA, Jackson J (2011) A cohort study assessing difficult patient encounters in a walk-in primary care clinic; predictors and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 26:588–594

Mika K, Riitta A, Markku P, Tiina L, Barengo Noel C, Antti J, Veikko S, Pekka J, Aulikki N, Erkki V, Jaakko T (2009) Prevalence, awareness and treatment of hypertension in Finland during 1982-2007. J Hypertens 27:1552–1559

Kribbs NB, Pack AI, Kline LR, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, Schubert NM, Redline S, Henry JN, Getsy JE, Dinges DF (1993) Objective measurement of patterns of nasal CPAP use by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis 147:887–895

McArdle N, Devereux G, Heidarnejad H, Engleman HM, Mackay TW, Douglas NJ (1999) Long-term use of CPAP therapy for sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159:1108–1114

Mulgrew AT, Cheema R, Fleetham J, Ryan CF, Ayas NT (2007) Efficacy and patient satisfaction with autoadjusting CPAP with variable expiratory pressure vs standard CPAP: a two-night randomized crossover trial. Sleep Breath 11:31–37

Teo M, Amis T, Lee S, Falland K, Lambert S, Wheatley J (2011) Equivalence of nasal and oronasal masks during initial CPAP titration for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep 34:951–955

Massie CA, Hart RW (2003) Clinical outcomes related to interface type in patients with obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome who are using continuous positive airway pressure. Chest 123:1112–1118

Redolfi S, Yumino D, Ruttanaumpawan P, Yau B, Mao-Chang Su, Lam J, Douglas Bradley T (2009) Relationship between overnight rostral fluid shift and obstructive sleep apnea in nonobese men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179:241–246

Tang SC, Lam B, Lam JC, Chan CK, Chow CC, Ho YW, Ip MS, Lai KN (2012) Impact of nephrotic edema of the lower limbs on obstructive sleep apnea: gathering a unifying concept for the pathogenetic role of nocturnal rostral fluid shift. Nephrol Dial Transplant 0:1–6

Wimms AJ, Richards GN, Benjafield AV (2012) Assessment of the impact on compliance of a new CPAP system in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. doi:10.1007/s11325-012-0651-0

Virkkula P, Rinne J, Bachour A (2008) Kuorsaajan nenä. Duodecim 124:641–648

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr. Antoni Anouf, a student at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Université Laval, Québec, for his helpful assistance with the graphics.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bachour, A., Vitikainen, P., Virkkula, P. et al. CPAP interface: satisfaction and side effects. Sleep Breath 17, 667–672 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-012-0740-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-012-0740-0