Abstract

For over four decades the Eclectic Paradigm has experienced a myriad of interdisciplinary advancements and evolved into an ever-broader and complex accumulation of different macro- and micro-level concepts. Despite its persistent validity for research on multinational enterprise activity, subject-related studies have often failed to correlate to previous findings and have independently drawn upon various versions of the Eclectic Paradigm, which exacerbates the comparability of the respective results. Yet, the literature lacks a systematic analysis of the heterogeneous development within a consistent body of knowledge. This paper contributes to the contemporary debate in that it systematically reviews and classifies the diverse developments within a unified context and, consequently, synthesizes and integrates the extant knowledge into a state-of-the-art presentation of the Eclectic Paradigm. Here, the study has set out to provide future research with a coherent basis and conceptual starting point. At this, a systematic literature review is conducted, analyzing 66 journal articles published between 1980 and 2017. Deduced thereof, the study (i) scrutinizes the largely neglected basic prerequisites (intention, underlying context, level of analysis), (ii) analyzes the imperative developments of the Eclectic Paradigm, and (iii) encapsulates the above within a coherent, state-of-the-art macro-level envelope of the Eclectic Paradigm. In light of the findings, the study concludes by identifying issues that deserve more attention or remain under-researched and, hence, provides suggestions for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

For over 40 years the Eclectic Paradigm has provided an impetus for an interdisciplinary debate and has motivated proponents and critics alike to pose new questions, introduce amplifications and critically scrutinize the peculiarities of its components (e.g., Cantwell 2015; Eden and Dai 2010; Dunning 2003a). John Dunning himself has worked extensively on the intellectual rationale, advocacy, and revision of what has become his most prominent work, hence perpetually stimulating further conversations (Eden and Dai 2010; Rugman 2010). Within the contemporary literature, the Eclectic Paradigm is generally considered the dominant theoretical concept for explaining the extent, pattern, and geographic dispersion of an enterprise’s foreign value-adding activity (Cantwell 2015; Ferreira et al. 2011; Franco et al. 2010; Harðardóttir et al. 2008). Its strength and uniqueness lies within the juxtaposition between a set of three interdependent variables which define “(i) the extent to which a firm engages in foreign production, (ii) the form which this production takes (FDI vs. non-equity alliances), and (iii) the location of this production” (Dunning 2003a, p. 4).

Notwithstanding Buckley’s (2004, pp. 7, 13) admittedly provocative remark insinuating a lack of a clear and significant research question in contemporary international business (IB) research, the Eclectic Paradigm has experienced a persistent evolution of various advancements and multidisciplinary developments. Over time, the motivation amongst scholars driving this development has soon evolved beyond a mere focus on IB, and included contributions from adjacent business and strategy fields. Indeed, the ample controversial debate as formative characteristic of the ever-changing global economy corroborates the continuous relevance of the Eclectic Paradigm (Mark I). However, despite its pioneering role and its prevailing utilization in explaining a multinational enterprise’s (MNE) internationalization process (Cantwell et al. 2010; Buckley and Hashai 2009), the Eclectic Paradigm has ever since been subject to copious criticism. Unsurprisingly, scholars have devoted substantial energy to advance the taxonomy towards an ever-broader combination of topics and sub-topics, leading to a multitude of different and rather complex versions. Consequently, its initial “analytical and intellectual elegance” has attenuated (Narula 2010, p. 36). Indeed, the literature has developed inconsistently, yielding contradicting notions regarding the Eclectic Paradigm’s normative intention and structure (Mark II). Authors have continuously drawn upon different versions of the Eclectic Paradigm. This hampered the comparability and pertinence of (empirical) studies (Eden and Dai 2010) as well as the integration of the respective findings into a homogeneous body of knowledge. Thus, we can recognize an increasing fragmentation of the research stream (Mark III). Consequently, several scholars have considered the typology as being confusing (Eden and Dai 2010; Rugman 2010), contradictory (Hennart 2012; Rivoli and Salorio 1996), or ambiguous (Nayak and Choudhury 2014; Devinney et al. 2002). Although attempts have been made to unravel the complexity by providing more tangible modifications or simplifications of the Eclectic Paradigm,Footnote 1 the current literature lacks a systematic synthesis of the heterogeneous development of the research field, which orchestrates the extant knowledge and provides a coherent understanding of the taxonomy and its underlying purpose (Mark IV). Indeed, the lack of a coherent understanding and uniform presentation of the Eclectic Paradigm offers a hitherto untapped potential within the IB field, which is crucial towards a meaningful further debate for theory and practice (Mark V).

Accordingly, this study seeks to approach these limitations and bring more clarity to the IB research stream. The aims, therefore, are threefold: (i) to review the IB literature on the Eclectic Paradigm by providing a scientifically rigorous, systematic contextualization and synthesis of the core developments over the last four decades (1980–2017); (ii) to deduce the main conclusions and integrate the resulting knowledge into a state-of-the-art presentation of the Eclectic Paradigm; and (iii) to identify further research opportunities on the basis of the new conceptual framework. At this, I believe that scrutinizing the widely neglected normative intention, underlying context, and level of analysis is pivotal for a coherent understanding of the basic prerequisites of the Eclectic Paradigm and, thus, for a meaningful further conversation. Consequently, this study will connect the past, present, and future and broaden the focus beyond the mere taxonomy of the Eclectic Paradigm. It equips those interested in this line of research with a uniform conceptual foundation that presents greater clarity, applicability, and integration.

To achieve the objectives, the paper first describes the methodology employed. Second, it discusses the main findings of the systematic review. Third, the study integrates the findings coupled with new perspectives into a conceptual framework, before concluding with suggestions for further research.

2 Designing the systematic literature review

The methodological framework followed a two-phased, sequential approach. In particular, I conducted a systematic literature review as advocated by Macpherson and Jones (2010), Tranfield et al. (2003), and Webster and Watson (2002), followed by a state-of-the-art review (see Booth et al. 2012; Grant and Booth 2009). Denyer and Tranfield (2009) as well as Tranfield et al. (2003) characterized the systematic literature review as a distinct, scientifically rigorous, transparent, and replicable process that seeks to minimize bias. The aim was to go beyond simply analyzing individual studies, but to synthesize and contextualize existing knowledge within a coherent framework (Fink 2010; Denyer and Tranfield 2009). Building thereupon, the state-of-the-art review utilized the key findings to provide a heuristic approach that offers new perspectives and points towards avenues for further research (Grant and Booth 2009). Accordingly, in its constitutive structure the resulting research process corresponded to the practice of past IB-related review articles (especially Kim and Aguilera 2016; López-Duarte et al. 2016), while also considering Fisch and Block (2018) and Turner et al. (2013). It followed a fourfold approach: (i) defining the research aim, objectives as well as the conceptual boundaries; (ii) defining and applying explicit search criteria in the selection of studies; (iii) ensuring the quality of the research by adopting a replicable and systematic search strategy; and (iv) synthesizing the relevant IB literature on the basis of an analytical framework which allows an impartial and critical presentation of the findings.

Given the broad spectrum of the concepts of foreign MNE activity within the IB field that are intellectually rooted in various received theories, I developed two distinct conceptual boundaries to narrow down the scope of potential studies to the most relevant sample (refer to Table 1). First, I delimited the thematic scope to the development of the Eclectic Paradigm and its components by deducing two main categories for the literature selection process. On the one hand, suitable articles were defined by an explicit focus on the Eclectic Paradigm. On the other hand, to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the cumulative advances in knowledge of the single components, I defined a more nuanced context of themes, namely Ownership Advantages, Location Advantages, Internalization Advantages, Multinational Enterprise, Foreign Direct Investment, and Investment Motives. In order to properly depict the full extent of both categories’ themes, each included a set of pervasive keywords, which eventually defined the search string. Second, in terms of data location, studies eligible were those full-length academic journal articles written in English and published between 1980 and 2017. Other forms of publication (e.g., books, book reviews or conference proceedings) were neglected.

Next, as a preparatory step in determining the sample of journal outlets to include, I restricted the search to high-quality journals focusing primarily on IB topics. Yet, in order to ensure an impartial selection process, the quality evaluation was based on the merit of the respective journal. This perspective is important, since influential journals provide seminal theoretical and empirical contributions, which tend to shape the ongoing debate by presenting the underlying cause and current evolution of research within the respective frame of reference (Furrer et al. 2008). For this reason and in line with previous literature reviews published within the Management Review Quarterly (MRQ) (e.g., Goede and Berg 2018; Thiele 2017; Grisar and Meyer 2016; Schmidt and Günther 2016; Roth and Bösener 2015), the VHB-JOURQUAL 3 ranking in international management was used to determine the final journal selection.Footnote 2 On the one hand, VHB is considered a major and renowned IB journal ranking list (Tüselmann et al. 2016; see also Vogel et al. 2017; Theußl et al. 2014). According to Schrader and Hennig-Thurau (2009), expert-based rankings such as the VHB treat scientific quality of articles and review processes as proof of perceived quality instead of the mere citation quantity, as focused upon in citation-based rankings. Furthermore, they found a strong and significant correlation between VHB and other major international journal rankings, such as the ISI Journal Citation Impact Factors or the British Association of Business Schools Academic Journal Quality Guide. On the other hand, VHB’s ranking in international management evaluates journals with an international perspective from the disciplines economics, international business, and business/management, thus allowing for a more interdisciplinary approach. In addition, several journals included in the VHB ranking, such as the Global Strategy Journal (GSJ), International Business Review (IBR), International Marketing Review (IMR), Journal of International Business Studies (JIBS), Journal of International Management (JIM), Journal of World Business (JWB), Management International Review (MIR), and Multinational Business Review (MBR) were identified as core IB journals by previous review studies (e.g., Kim and Aguilera 2016; Xu et al. 2008; Griffith et al. 2008; Chan et al. 2006), which incorporate seminal contributions on the Eclectic Paradigm. As a result, I initially considered all 20 journals ranked therein as C or higher.

Lastly, EBSCO Host Global Search was identified as an appropriate database, since it draws upon several content providers, such as Business Source Complete, Complementary Index, Academic OneFile, Emerald Insight, JSTOR Journals or SwePub. I conducted a comprehensive database search with multiple screening rounds. Moreover, in order to ensure consistency and replicability of the search results, the database search was also conducted by another independent researcher. At this, we employed a Boolean search mode by applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria defined through the above conceptual boundaries. This means, our search string included the keywords of both categories, which were restricted to title (TI), author-supplied keywords or subject terms (SU), and abstract (AB). At least one keyword of both categories had to be contained per article.Footnote 3 After excluding journals that did not publish research on the Eclectic Paradigm or yielded no results based on the specific search string, 10 journals have been identified as relevant for the review (refer to Table 2).

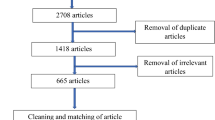

The initial search yielded a preliminary sample of 192 results. After exact duplicates have been removed automatically from the results (n = 82), a subsequent manual screening for remaining duplicate papers was conducted (n = 13). Consequently, this yielded a residual sample of 97 articles. Thereupon, I conducted a qualitative analysis of all 97 articles by screening and interpreting the content of both titles and abstracts, in order to allow a refining of the sample. At this stage, only those articles, which explicitly focused on the Eclectic Paradigm (primary focus), were included in the further process. Those studies that briefly addressed the Eclectic Paradigm within a wider context of entry mode or general IB theories (subordinate focus) (e.g., Gerbl et al. 2015; Mathews and Zander 2007; Liu et al. 2005; Macharzina and Engelhard 1991) or lacked pertinence to the present study (e.g. Czinkota et al. 2009) were excluded. Additionally, I screened the body of the excluded articles in order to verify the final decision. Eventually, 25 articles were discarded, whereas 23 articles yielded rather ambiguous results, thus inducing a more profound screening. Despite the general rigid process of the systematic review, this step was intended to reduce the risk of eliminating potentially valuable contributions. Hence, a full-text screening of all remaining 72 articles was performed, resulting in the exclusion of another 14 studies. Yet, eliminations in the current phase were based on more substantial factors, such as a lacking contribution towards the development or current/future state of knowledge of the Eclectic Paradigm. The remaining 58 articles were further examined for possible cross-references. As a result, the International Journal of the Economics of Business (IJEB) was added to the sample, since it contributed with a special issue on the Eclectic Paradigm, containing nine articles. After applying the above process, eight out of nine articles were additionally included. Consequently, the search resulted in a total of 66 journal articles eligible for the in-depth and full-text analysis, of which 42 were theoretical/conceptual contributions and 24 were empirical (Appendix A provides a full list of the studies included). The sampling process of the search results is illustrated in Fig. 1 below. Appendix B depicts a descriptive analysis of the structure and evolution of the literature reviewed.

3 The development of the Eclectic Paradigm

The Eclectic Paradigm drew upon and synthesized the seminal IB theories of the 1960s and 1970s, which were centered around the different aspects of foreign production. Yet, contrary to those approaches, the Eclectic Paradigm was neither intended to be a theory of the MNE nor of foreign direct investments (henceforth FDI) per se. Rather, it depicted a conceptual framework for determining the scope and pattern of a firm’s foreign activity within a unified context. At this, it combined and deployed selected aspects of Hymer’s theory of monopolistic advantage (1960) and Kindleberger’s structural market imperfection theory (1969) (as ownership-specific or O advantages), Vernon’s product cycle theory (1966) (as location-specific or L advantages), and Buckley and Casson’s internalization theory (1976) (as internalization or I advantages) (refer to Appendix C for a more detailed introduction of the antecedents of the Eclectic Paradigm). Dunning recognized that neither are firms purported black boxes nor markets the exclusive facilitators of economic transaction (Dunning 1977, 1979, 1993a, b). Furthermore, as opposed to most approaches at that time, Dunning (1977, 1979) amalgamated two kinds of market imperfections within his concept, which might cause firms to prefer international production in lieu of international trade, later classified as structural market imperfections and transactional market imperfections (Dunning and Rugman 1985; Dunning 1988a). MNE activity hence, concerned the distinctive characteristic to combine the cross-border dimension of value-adding activities with controlling and orchestrating these activities (Cantwell 2015; Ferreira et al. 2011; Pitelis 2007; Dunning 1973, 1977, 1979, 1988a, 1993a, b). The following systematic review scrutinized the literature on the Eclectic Paradigm in more detail. The investigation period (1980–2017) was divided into four segments. To allow for a coherent and comprehensible structure, each segment dedicates a separate section to the general, period-specific development of the related literature and of the OLI taxonomy’s overarching perception within received theory, respectively, before exploring the specific adaptations of the single components individually, where applicable. Figure 2 serves as a roadmap through the single stages by outlining a simplified, self-explanatory reflection of the main developments.

3.1 The first development stage (1980–1989)

3.1.1 General development

Within the first segment (1980–1989), the debate progressed the cross-disciplinary perspective on the economics of organizations, reflecting the approach of Dunning’s earlier studies (1977, 1979). Yet, whereas these preceding contributions focused upon the single components of the OLI taxonomy rather individually, Dunning has offered a more holistic and interconnected derivation. On the one hand, Dunning (1980) recognized the interdependency of O and L endowments. Since one type of O endowments may be related to home or host country-specific endowments (e.g., availability and acquisition of particular resources), the resulting O advantages thus depict bygone L advantages. By implication, Dunning empirically corroborated that O capabilities are either derived from the MNE’s home country or generated within the (foreign) network it operates. Conversely, L endowments facilitate the creation of and provide access to indigenous L capabilities. On the other hand, Dunning (1988a) differentiated between O and I advantages, which determine the MNEs’ capability (provided by O advantages) and their willingness or motivation (provided by I advantages) to internalize the respective markets, respectively. Therefore, neither endowment approach alone sufficed to explain international production, but trade (export) and non-trade (FDI) routes of internationalization were seen as dependent on the interplay and reciprocity of all three OLI conditions.

3.1.2 Ownership advantages

A pivotal extension to the taxonomy of O advantages occurred with Dunning’s (1988a) seminal contribution, which was inter alia a response to the prevailing criticism from internalization theorists. It distinguished between two types of O advantages, videlicet those emerging from a firm’s proprietary ownership of distinct, income-generating assets (Oa) and those reflecting the MNE’s ability to capture and coordinate the cross-border transactional benefits of the various assets in order to create competitive advantages thereof (Ot). Reorganizing O advantages into asset-based and transactional O advantages was an attempt geared towards directly incorporating transaction costs into the O taxonomy. Indeed, market failures depicted the underlying condition for international activity and, consequently, determined both Oa and Ot advantages. Only then, once market imperfections exist, the spatial disposition of factor endowments as well as the cross-national transaction costs for intermediate products explain foreign activity within the scope of a general paradigm.

3.1.3 Investment motivation

Dunning (1988a) further suggested that both the identification and valuation of the Eclectic Paradigm’s single tenets influencing MNE activity are dependent upon a set of three underlying motives, namely market-seeking (i.e. import substituting), resource-seeking (i.e. supply oriented), and efficiency-seeking (i.e. rationalized investment) types of international production. Yet, Dunning still recognized the existing lack to explain each particular MNE activity sufficiently. Drawing hereupon, Boddewyn (1988) corroborated the need to consider the associated motivation and precipitating conditions in order to present a holistic explanation of an MNE’s behavior. In other words, aside from the possibility and favorability of internalizing foreign markets, it must also be intended and induced by the MNE itself. By considering various political, social or cultural non-market forces that may elicit or trigger further market imperfections—which were meant to be endogenized in lieu of merely being viewed as exogenous—Boddewyn has proposed a new explanatory perspective to the Eclectic Paradigm on the reasons of MNE existence that other theories thus far have failed to explicate.

3.2 The second development stage (1990–1999)

3.2.1 General development

So far, the Eclectic Paradigm has been entrenched within hierarchical capitalism, in which MNEs superseded external markets with internal hierarchies, i.e. through wholly owned entry modes (referred to as exit by Dunning 1995, p. 464). Here, the propensity of enterprises to internalize the markets was based on the conjecture that they regard market failures as exogenous (e.g., Dunning 1995; Johanson and Vahlne 1990). Yet, although already been insinuated towards the end of the previous period (Dunning 1988a), the period 1990–1999 clearly indicated a shift in emphasis to more informal and open intermediate modes of entry, hence adding a new dimension to the rationale for FDI (e.g., Banerji and Sambharya 1996; Pan 1996; Dunning 1995; Schroath et al. 1993). Firms increasingly adopted cooperative solutions, such as equity joint ventures (EJVs) or strategic alliances, to overcome endemic market failure (referred to as voice by Dunning 1995, p. 464). Especially the recent focus on emerging markets triggered the increased interest in cooperative entry modes. Yet, the novel trajectory, which Dunning (1995) referred to as alliance capitalism, changed the perception of the structure of MNEs, which were growingly seen as relational networks, and with it the composition of O advantages (e.g., Pan 1996; Banerji and Sambharya 1996; Brouthers et al. 1996). Accordingly, Dunning (1995) elucidated that the motivation for MNEs to go abroad could be based on both acquiring as well as exploiting O advantages. In other words, the MNE’s assets could consist, firstly, of internally generated assets and, secondly, of assets accessed through cooperative partnerships. Hence, strategic asset-seeking FDI were added as fourth component to the investment motive taxonomy. In order to embrace these cooperative entry modes, scholars were compelled to rethink the traditionally perceived constituent components of the Eclectic Paradigm, also to allow for a more dynamic approach. In essence, the observed implications were threefold.

3.2.2 Ownership advantages

Firstly, since strategic asset-seeking investments mainly concerned the augmentation of pre-existing O advantages, emphasis has been placed on the increasing importance of multinationality and prior internationalization experience, respectively, as a distinct asset (e.g., Brouthers et al. 1999; Pan 1996; Dunning 1995; Johanson and Vahlne 1990). For instance, Banerji and Sambharya (1996) empirically corroborated the positive correlation between multinationality and equity mode of entry of Japanese keiretsu affiliations in the US market, i.e. as part of an alliance-based strategy. Moreover, the literature recognized the reinforced role of knowledge and innovation in preserving and augmenting competitive advantages with respect to domestic or foreign competitors. By implication, cross-border alliances may stem from the motivation to create relational assets, allowing the respective MNE to access resources owned by a partner entity (Banerji and Sambharya 1996; Dunning 1995). Here, the established conjunction that a firm’s capabilities were limited to its O boundaries implied that factors beyond those boundaries, which affected the firm’s competitive capacity, were characterized as exogenous. However, this notion had lost its adequacy if a strategic partnership had direct impact on the MNE’s quality of efficiency-related decisions (Dunning 1995). Thus, strategic partnerships generally promoted the opportunity for joint value creation in terms of e.g. exchanging tangible and intangible resources, enhancing efficiency, or facilitating innovatory growth (Banerji and Sambharya 1996).

3.2.3 Location advantages

Secondly, scholars placed a renewed focus on the study of locations due to their role as contributors to the evolution of alliance capitalism. On the one hand, despite the availability of traditional L endowments, the presence of spatially connected business networks as well as (potential) partners became a locational pull factor for foreign investors. On the other hand, the underlying conditions and the country’s immobile assets enhancing those inter-firm alliances (e.g., an innovation-driven industrial economy) subsequently impinged upon the organizational form of the foreign investments (Dunning and Bansal 1997; Dunning 1995; Johanson and Vahlne 1990). At this juncture, the phenomenon of psychic distance—understood as the firm’s perception of cultural, institutional and economic disparities between the host and home country—and its effects on entry mode choices experienced a revived interest (Dunning and Bansal 1997; Banerji and Sambharya 1996; Schroath et al. 1993; Johanson and Vahlne 1990). Schroath et al. (1993) empirically found that a close psychic distance is leading to a greater degree of O advantage exploitation, thus corroborating the previously emphasized interdependency of O and L endowments (see Dunning, 1980). Consequently, several studies pointed towards a negative correlation between psychic distance and the propensity of firms to engage in equity investments (Banerji and Sambharya 1996; Schroath et al. 1993). Yet, contrary to the abovementioned, Pan’s (1996) empirical study on international EJVs in China found a positive correlation between a foreign partner’s willingness to own a majority share in a strategic relationship and the perceived cultural distance. In short, developed market multinationals (DMMs) were more determined in acquiring a majority EJV share in an emerging country in lieu of emerging market multinationals (EMMs) sharing comparable cultural values, thus implying a lower sensitivity of DMMs to distance effects. Yet, further empirical evidence to substantiate the claim was still due.

3.2.4 Internalization advantages

Thirdly, Dunning (1995) indicated that inter-firm alliances in lieu of traditional equity or non-equity investments may provide an additional and more effective option to circumvent market failures, especially regarding MNEs’ dynamic and competitiveness increasing goals. This means that cooperative entry modes do not necessarily prompt higher internalization incentives, but rather enable a more effective achievement of objectives or diversification of capital and risks of the investing firms. Banerji and Sambharya (1996) provided further empirical evidence that strategic partnership increase competitiveness.

3.2.5 Concluding remarks

Contrary to the above, Itaki (1991) provided a hitherto unprecedented critical view on the Eclectic Paradigm. First, similar to prior internalization theorists, he emphasized the redundancy of O advantages, since O endowments resulted from a firm’s organizational capability to internalize and integrate various assets. Second, Itaki was highly critical of the separate existence and independent determination of O and L advantages, since, in economic terms, O advantages are inevitably influenced by the respective L advantages. Schroath et al. (1993) corroborated Itaki’s claim regarding the interdependency between both advantages, for the exploitation of O endowments could only occur in conjunction with the specific host-country L endowments. Later, Brouthers et al. (1996) provided further empirical evidence of a positive correlation between O and L endowments. Last, Itaki critically pointed towards the methodological danger of the progressive accumulation of variables under the OLI taxonomy. Instead, he underscored the importance of a small number of decisive determinants as well as their non-substitutability to meaningful expound an economic phenomenon such as foreign investments.

3.3 The third development stage (2000–2009)

3.3.1 General development

As MNE activities have developed into new patterns within global capitalism, primarily fostered by economic, political and technological imperatives (Lundan and Hagedoorn 2001; Dunning 2000), the upcoming decade has experienced the occurrence of new approaches, which were more oriented towards strategic management and institutional theory (Dunning 2001, 2009; Madhok and Phene 2001). Moreover, it provided a more critical perspective on the OLI taxonomy, especially due to the incremental interest from scholars beyond the IB subject area. Particularly, the Eclectic Paradigm has been criticized for its one-sided focus on costs and static market failure as basic assumption of MNE activity (e.g., Li 2007; Li et al. 2005; Whitelock 2002), its assumption regarding the availability of perfect information while lacking to acknowledge the (dynamic) changing environmental conditions (e.g., Buckley and Hashai 2009; Li 2007; Singh and Kundu 2002), its pluralistic character restricting a formalization (Buckley and Hashai 2009), or, for instance, its missing focus on endogeneity (Pitelis 2007).

Research focusing on the strategic management strand has offered diversified contributions from various thematic viewpoints, yet often failed to integrate the rather micro-level oriented insights sufficiently into the general (macro-level) meta-framework. Generally, the dynamization of the Eclectic Paradigm evolved as a tent suffusing the OLI elements. Whereas IB- and economics-oriented scholars devoted their research to a more general, contrasting juxtaposition of the dynamic and static sub-components of the OLI advantages (e.g., Cuervo-Cazurra 2008; Dunning et al. 2007; Dunning 2000), strategy scholars intensified their research on a general reshaping of the Eclectic Paradigm towards a more strategic model (e.g., Brouthers et al. 2009; Pitelis 2007; Li et al. 2005). Indeed, by incorporating strategy as a distinct dynamic constituent, the conversation entered the micro-level. Similarly, Guisinger (2001) revised the OLI taxonomy towards OLMA, replacing I with M (mode of entry) as well as appending A (adjusting business processes to the environment), hence shifting emphasis towards the firm-level.

3.3.2 Ownership advantages

Yet, Dunning had already recognized that a potential link between strategy and the triumvirate can be ensued by means of firm-level motivations for foreign activities in his previous publications (e.g., Dunning 1988a), emphasizing that knowledge-based alliances are motivated through strategic asset-seeking investments (e.g., Dunning 1995). However, by shifting the focus from the exploitation of O advantages to the management of O assets (see Cantwell and Narula 2001; Lundan and Hagedoorn 2001), Dunning (2000) amplified the discussion towards the comparison of static and dynamic O advantages. In essence, market- and resource-seeking investments predominantly concern the exploitation of existing O advantages and thus were regarded as rather static investments. On the contrary, efficiency- and strategic asset-seeking investments primarily concern the exploration of knowledge and therefore are dynamic in nature. By implication, static O advantages provide income from a preexisting set of assets, whereas dynamic O advantages represent the firm’s subsequent ability to perpetuate and enhance income-generating assets over a period of time, thus sustaining long-term growth (Dunning et al. 2007; Lundan and Hagedoorn 2001; Dunning 2000, 2001).

3.3.3 Location advantages

Moreover, the discussion on the geographic locations has advanced from representing mere targets for exploiting immobile raw materials and local markets (static L advantages) to potential sources of distinct learning, knowledge, and innovation assets, inclusive of the presence of potential indigenous partners (dynamic L advantages) (e.g., Pak and Park 2005; Dunning 2000, 2001). In addition, studies contributing to the institutional strand have dedicated specific focus to the role of the political and cultural environment and to how the respective formal and informal institutions influencing MNEs’ strategic choices can be incorporated into the Eclectic Paradigm (e.g., Cuervo-Cazurra 2008; Stoian and Filippaios 2008; Pitelis 2007; Mudambi and Paul 2003; Dunning 2000). Those formal (e.g., investment incentives, taxation, entry and exit requirements) and informal institutional factors (e.g., social customs and norms, cultural peculiarities, and behavioral initiatives) advanced the location’s dynamic comparative advantages and, hence, critically determined locational choices of firms (Dunning 2000; Mudambi and Paul 2003). Indeed, Dunning (2009) underlined the impact of the institutional regimes on the dynamic interplay of the OLI triumvirate of MNEs (also corroborated by Cuervo-Cazurra 2008) as well as on the L component of the indigenous markets.

3.3.4 Internalization advantages

In a similar vein, whereas the explanation of how to most efficiently make use of the existing assets was referred to static I advantages, the identification and explanation of the optimal modality to organize asset-augmenting foreign activities depicted the dynamic dimension of I advantages (Dunning et al. 2007; Dunning 2000). Furthermore, Dunning (2000) critically elucidated that these new inter-firm organizational modalities resulting thereof may, however, not be fully explained by contemporary internalization theory. Consequently, Scott-Kennel and Enderwick (2004), building upon Dunning (1995), called for a defusing of the I component towards a conceptual inclusion of non-equity inter-firm cooperations. This intermediate stage is located “on a continuum between arm’s-length markets and complete hierarchies” (Dunning 1995, p. 465), i.e. quasi-internalization of a firm’s O advantages and resources into a strategic partnership or external network of a specific location.

3.3.5 Investment motivation

Additionally, on the intersection of institutional and strategy factors, various contributions have examined the nexus of new modes of entry (particularly networks, subsidiaries, and alliances) and the associated implications of knowledge or learning as dynamic capabilities (e.g., Buckley and Hashai 2009; Dunning et al. 2007; Pak and Park 2005; Scott-Kennel and Enderwick 2004; Singh and Kundu 2002; Guisinger 2001; Madhok and Phene 2001; Moore 2001). According to Li et al. (2005), the constituent component for a dynamic response to changing business environments, through incremental evolution or interspersed equilibria, is depicted by firm strategy. In a similar vein, Stoian and Filippaios (2008), referring to Guisinger (2001), illustrated the need for firms to adapt their operations to the respective environment by considering institutional theory. Both contributions highlighted the importance of a firm’s ability to endogenous learning as a reaction to exogenous changes. Yet, whereas Li et al. (2005) reappraised the Eclectic Paradigm by shifting focus from market failure (exogenous) towards the development and exploitation of an MNE’s endogenous components (investment motivation), i.e. strategy, resources and structure, to adapt to local environments effectively, Stoian and Filippaios (2008) empirically found the existence of a general learning curve within the process of international expansion. In particular, the learning curve enabled MNEs to cope with the environmental changes within the target location, hence reducing the significance of expropriation risk.

3.3.6 Concluding remarks

Lastly, we can draw several implications on the interaction effects of the OLI variables from the period-specific literature. For instance, corroborating previous contributions (see Brouthers et al. 1996, 1999; Dunning 1988a, 1993a), Buckley and Hashai (2009) empirically found a continuous in lieu of a dichotomous relationship between OLI variables, demonstrating a positive linear connection between O and I advantages. Pitelis (2007) further elucidated the dynamic interrelation of the triumvirate, specifically deducing four implications. First, L advantages convert into O advantages once realized. Second, I advantages relate to O and L advantages since the latter two concern the why and where of internalization (see also Owawa and Castello 2001). Third, I and L advantages are endogenously regarded as O advantages in the context of learning. Fourth, the OLI triumvirate can be shaped by the MNE’s own decision and motivation, respectively and is hence endogenized. With a stronger focus on a practical context, Singh and Kundu (2002) underlined the continuous development of real-life OLI variables due to the changing environmental conditions, as opposed to the rather static conceptual definition found in the majority of publications.Footnote 4

3.4 The fourth development stage (2010–2017)

3.4.1 General development

Within the last period (2010–2017), referred to as a new era of the information age (e.g., Alcácer et al. 2016), the literature dwelled upon the incremental development of and the interdependency amongst the single factors more comprehensively than the previous periods. Particularly the MBR (volume 18, issue 2) has devoted an entire issue to a controversial discussion regarding O advantages (Eden and Dai 2010; Lopes 2010; Lundan 2010; Narula 2010; Rugman 2010; Verbeke and Yuan 2010). Additionally, whereas the majority of previous studies was rather reluctant towards critically challenging the four investment motives, more than one third of the current research scrutinized and extended the typology of motives more profoundly. In sum, the findings generally underpinned the perpetual increase in complexity of the OLI taxonomy, and a thereof resulting dissent amongst scholars towards a contemporary elaboration of the Eclectic Paradigm. More precisely, the rather economics-oriented strand of research criticized that the continuous identification of new lacunae and the resulting expansions made the final composition ambiguous and unwieldy (e.g., Eden and Dai 2010), calling for a new gatekeeper function of the Eclectic Paradigm that responds to the complex shifts in IB (as suggested by Narula 2010). The strategy-oriented strand of research, on the contrary, explicitly called for further modification of the OLI taxonomy and investment motives towards a more micro-oriented framework.

3.4.2 Ownership advantages

The majority of studies that focused primarily on O advantages (e.g., Alcácer et al. 2016; Li-Ying et al. 2013; Eden and Dai 2010; Lopes 2010; Lundan 2010; Narula 2010; Verbeke and Yuan 2010) incorporated the institutional approach introduced by Dunning and Lundan (2008a). It recognized the importance of institutions as endogenous constructs generating O advantages. More precisely, whereas the earlier nomenclature of O advantages, distinguishing between Oa and Ot advantages (see Dunning 1988a), explained MNEs’ growth and boundaries, the explanatory significance was bound to the binary selection between market and hierarchy (Lundan 2010). Yet, in order to take account of the new forms of MNEs’ (decentralized) governance structures and their engagement in non-market domains, institutional ownership advantages (Oi) have been introduced. Together with Oa and Ot, though distinct and separate therefrom, Oi represented the novel triumvirate of O advantages (refer to Eden and Dai 2010, pp. 26–28; Lopes 2010, pp. 75–76; Lundan 2010, p. 55). However, with the emergence of the new O typology, which was induced based on the general shift towards a more implicit micro-/firm-level analysis, the fundamental discussion between the economics and strategic perspective perpetuated (Narula 2010). In essence, authors such as Lopes (2010), Rugman (2010) or Verbeke and Yuan (2010) criticized the evident lack of incorporating the uniqueness of the single firm. Yet, whereas Rugman (2010) questioned the general legitimacy of O advantages and thus promoted the traditional FSA/CSA matrix instead, Lopes (2010, pp. 76–77) and Verbeke and Yuan (2010, pp. 94–100) both proposed adaptations to the O typology, focusing more on the individual firm. Conversely, proponents of Dunning’s original macro view on the Eclectic Paradigm (e.g., Eden and Dai 2010; Narula 2010) challenged the suitability of the OLI variables in general within a micro- or firm-level perspective. In fact, also critics acknowledged the typology’s embeddedness within neo-classical economics, which is grounded on assumptions not appropriable on studying the individual firm (e.g., Vahlne and Johanson 2013). Rather, as Eden and Dai (2010) pointed out (referring to Dunning 2002), the Eclectic Paradigm’s purpose is to explain international activity at the country level, emphasizing the reasons for an MNE’s propensity to invest overseas in lieu of domestically as well as explicating the pattern and structure of cross-border FDI. Furthermore, contrary to Rugman (2010), Eden and Dai (2010) defended both the imperative of O advantages and the novel threefold division. They referred to the underlying questions associated with each of the OLI components, namely why firms engage in international production (explained by O advantages), where firms engage (explained by L advantages), and how firms organize the respective foreign activities (explained by I advantages). By implication, each component is aimed at answering a different question and, hence, is distinct and non-interchangeable.

3.4.3 Location advantages

The increasingly complex spatial distribution of MNEs, including the role of L advantages, emphasized the concatenation of multiple locations and, hence, a firm’s interdependence therewith (Alcácer et al. 2016; Li-Ying et al. 2013). Here, similar to the above O-specific elaborations, a contrasting macro and micro perspective has mainly led the location-specific debate. Narula and Santangelo (2012) provided a synoptic and multi-level view hereunto. On the one hand, firms’ locational choices were influenced by their cognitive and resource-related constraints, including the potential repercussions of wrong choices, and thus represented strategic decisions, which insinuated a micro-perspective. On the other hand, firms were simultaneously constrained by the respective L advantages shaped by host governments and institutions, constituting to a macro-level perspective. Yet, whereas they presented a new classification of L advantages within three broad categories, namely country-level, industry-level, and firm-level or collocation L advantages (p. 10), Li-Ying et al. (2013), referring to Dunning and Lundan (2008a), suggested a dichotomous structure. This comprised resource- and asset-related L advantages (Lr), such as access to natural and human resources or critical (knowledge-intensive) assets, and institution-related L advantages (Li), referring to a host location’s formal and informal institutions.

3.4.4 Investment motivation

Buckley et al. (2012) further expanded on the host and home country linkages as institutional assets. On the one hand, a home country’s institutions and macroeconomic environment may constitute roots of a firm’s competitive advantage when being internalized. On the other hand, a host country’s location resources, assets and institutions influence the propensity of a firm to invest herein based on the respective motives. Hereunto, Wilson and Baack’s (2012, pp. 113–114) empirical contribution was generally in conformity with Buckley et al.’s (2012) notion of the association between L advantages and investment motives. Cuervo-Cazurra and Narula (2015, p. 5) critically scrutinized an extended typology of investment motives, adapted from Dunning (1993a), which featured supplementary or secondary motives in addition to the traditional fourfold classification. Yet, although challenging the segmentation into primary and secondary motives, they emphasized the existence of mixed motives in the course of the foreign activity (also briefly enunciated by Narula and Santangelo 2012). The study referred to Cuervo-Cazurra et al. (2015), who provided a simplification into four conceptually driven envelopes, namely buy better, sell more, upgrade, and escape. Moreover, Moghaddam et al. (2014) provided a nuanced debate concerning internationalization motives for EMMs. They criticized the traditional motives’ unsuitability regarding the adequate application of EMMs’ internationalization processes, and, hence, proposed a modified typology (refer to p. 368). Generally, the application of the Eclectic Paradigm for cases of EMM internationalization was controversially scrutinized. For instance, Hennart (2012) questioned the suitability of the taxonomy to elucidate the emergence of EMM activity. Due to the prevailing dichotomy between O and L advantages, he insinuated that the possession of O advantages as precondition for FDI (e.g. technology or brand names) was less available to EMMs. Yet, Narula (2012), albeit confirming the differences between EMMs’ and DMMs’ initial conditions, predicted that these will diminish once past the nascent MNE stage.

3.4.5 Concluding remarks

Lastly, as opposed to the mainstream literature, Zhou and Guillen (2016) recognized the concept of liability of foreignness (LoF), understood as the additional costs MNEs experience when operating in overseas markets, as a competitive disadvantage for foreign firms. They proposed a trichotomy of the LoF, linked to each component of the OLI triumvirate and reducing the associated advantage of MNEs when investing abroad (refer to p. 315). Although, for instance, Narula and Santangelo (2012, p. 9) referred to certain L advantages (that are made available discriminatively to indigenous and foreign firms by local governments) as a subset of the principle of LoF, it had otherwise not been sufficiently associated with the Eclectic Paradigm as a distinct element.

3.5 Conclusion

The review of the literature has perspicuously demonstrated the evolution of the Eclectic Paradigm into an envelope incorporating and tolerating novel and increasingly complex utilizations. These depicted the historical development of IB and adjacent environments (e.g., strategic management, institutional economics, or political sciences) over the last four decades. It is true of the Eclectic Paradigm that it has morphed into various forms and interdisciplinary versions, partially incorporating both meso- (i.e. industry) and micro-level (i.e. firm) perspectives. Yet, despite the perplexing abundance of changes and adaptations, its three main questions regarding MNE activity—the why (O), where (L), and how (I)—however, have demonstrated an ever-persevering validity. At this, the Eclectic Paradigm is idiosyncratic in that it was designed to being adapted and applied contextually to a plethora of IB situations. On the other hand, despite the prevailing centrality of the O, L, and I components, the taxonomy is now amplifying the general evolution of the MNE into novel organizational and cooperative structures, transcending the once restricted boundaries of firms, markets, and countries. This evolvement, however, is at the expense of clarity and stringency, marginalizing the uniformity and explanatory power of the Eclectic Paradigm. Furthermore, not least due to the lack of a uniform and topical version, empirical studies have drawn upon various versions and, indeed, period-specific characteristics. To illustrate this point, the 24 empirical studies analyzed within the literature review drew upon 40 publications from Dunning (and co-authors), ranging from 1973–2008 (refer to Appendix D for a full listing). This breadth, once more, highlights the contemporary lack of a consistent basis. Hence, we can conclude that, by corroborating Mark I to V of the introductory section, the above systematic literature review has provided ample evidence to support the initial call for a new state-of-the-art presentation of the Eclectic Paradigm.

4 State-of-the-art presentation of the Eclectic Paradigm

Thus far, we have explored the Eclectic Paradigm through a backward-looking lens, particularly following the questions of why and how it evolved over the past four decades, i.e. metamorphosing into a big tent or envelope paradigm (e.g., Eden and Dai 2010; Narula 2010; Dunning 2000). In what follows, I turned towards investigating and combining the current state of knowledge through a forward-looking lens. Here, extrapolated from the systematic literature review, I depicted a state-of-the-art presentation of the Eclectic Paradigm. This, however, implied the broadening of the object of investigation beyond the mere OLI taxonomy. More precisely, much of the current controversial debate around the Eclectic Paradigm was grounded on the plurality of notions concerning its (normative) intention and the respective context. Therefore, three steps defined the approach: (i) scrutinizing the basic prerequisites, (ii) analyzing four imperative developments of the Eclectic Paradigm, and (iii) encapsulating the above within a coherent state-of-the-art presentation.

4.1 Understanding context and perspective of the Eclectic Paradigm

Indeed, it is true for the understanding of any theory or paradigm that the guiding principle of its conception, as well as the underlying context, initially have to be comprehended and incorporated in its processing. Yet, it was commonly this nexus that was being neglected by a large proportion of studies dealing with the Eclectic Paradigm. The omission to factor in the rationale and target definition of the Eclectic Paradigm has led to the complex and ever-growing list of categories and variables on different levels of analysis. However, in order to facilitate a theoretical and empirical comparability and, hence, a homogeneous validity of results, a coherent and univocal basis must be agreed upon and utilized. Thus, the following section sought to provide such basis, by elaborating on the intention, the underlying context, and the level of analysis of the Eclectic Paradigm (three basic prerequisites).

The Eclectic Paradigm is a multicausal approach, which initially was an attempt to overcome the monism of the prevailing partial analytical theories of internalization and MNE theory, by integrating and accommodating these under a common analytical framework. The purpose was thereby to address the overarching level and pattern of MNE activity or foreign investments; hence, to explain the process and determinants of foreign activity (intention) (Dunning 2000).

Despite the metamorphosis from a theory into a paradigm along with the perpetual changes in the economic and political milieus (i.e., the metaparadigm), the intention maintained its validity. In general, this can be attributed to the underlying purpose of a paradigm (refer to Kuhn 1970, pp. VIII, 10). Accordingly, the Eclectic Paradigm was to offer a set of generic conjectures within a methodological framework that pointed towards a more specific set of operationally testable theories and associated variables which allowed the contextualized explanation of different types of foreign value-adding activities (underlying context) (Dunning 1980, 1988a, 1995, 2000, 2009).

More precisely, while the Eclectic Paradigm functions as an envelope providing the basic structure—originally addressing the why, where and how questions of MNE activity—the respective application and configuration of the individual OLI parameters are strongly contextual to the particular firm and its response hereunto. This means, that the characteristics of the investing entity’s objectives and strategies, together with the specific economic and political attributes of the home and target investment country are reflected herein, thus eventually answering the above questions. Yet, the contextualized configuration of the individual parameters—irrespective of their application and peculiarity—has no impact on the basic structure of the Eclectic Paradigm. Au contraire, the Eclectic Paradigm’s strength is the ability to juxtapose and apply its key constructs to a multitude of economic situations, and, hence, its ability to respond to various changes in the metaparadigm. For this reason, the scientific debate is in need of a fundamental rethinking vis-à-vis the central and superordinate role of the Eclectic Paradigm. Here, I agree with Moghaddam et al. (2014), Eden and Dai (2010) or Narula (2010) that the continuous modifications and adaptations of the taxonomy, albeit inevitably reflecting the historic evolution of IB, led to confusion and a cumbersome complexity that to some extent marginalized its attractiveness for many scholars. Furthermore, although supporting Narula’s (2010) notion of a simpler version, thus serving its role as an envelope, the proposed Eclectic Paradigm lite (consisting solely of the basic O, L, and I advantages and investment motives) yet omitted the opportunity to incorporate the pivotal basic elements that grasp the complex phenomena of contemporary IB, thereby making the proposition rather obsolete to modern requirements.

Hence, the balancing act between, firstly, the Eclectic Paradigm being sufficiently specific to be capable of appreciating the prevailing complexity in IB, without failing to fulfill its role as a paradigm, and, secondly, the contextual granularity of the underlying theory can be made by incorporating the respective level of analysis. Thus, the Eclectic Paradigm must be considered separately from applying its constituent components, in that the various applications of the latter, i.e. analyzing context-specific IB environments, all belong to the one conjoint classificatory envelope. By implication, the Eclectic Paradigm (EP) as macro-level envelope serves as a coherent and homogeneous basis, upon which case-specifically the contextual micro-level characteristics can be analyzed (EP*) (level of analysis). In other words, for the purpose of analyzing IB-related questions, the basic EP is applied and, consequently, case-specifically adapted on a more granular micro-level, incorporating contextual add-ons to the OLI taxonomy that suit the specific case (EP→EP*).

Therefore, following Eden and Dai (2010), the pervasive comparison of the Eclectic Paradigm (macro-level) with other micro-level theories, such as internalization theory including the concomitant criticism (e.g., redundancy of O advantages, see Hashai and Buckley 2014; Rugman 2010; Hennart 2009; Itaki 1991), generally lost its validity, due to the differences in perspective and emphasis. To illustrate this, whereas internalization theorists criticized that O advantages should be incorporated into I advantages (micro-level perspective), the Eclectic Paradigm extended beyond the mere theory of the firm to cross-border value-adding activities (macro-level perspective). At this, O and I advantages were seen as complementary, with the former reflecting the relevant capabilities needed for value-adding activities and the latter distinguishing between various aspects of firms’ cross-border activities, i.e. the firm’s willingness to internalize these (Dunning 1988a).

4.2 Understanding the OLI taxonomy

Built upon the process-characteristic of the Eclectic Paradigm (as indicated in Fig. 2), the second step analyzed and discussed four developments pivotal to the contemporary OLI taxonomy. These included (i) the interdependency of the four components and the influences of endogeneity and exogeneity, (ii) the importance of investment motives, (iii) the incorporation of a dynamic perspective as well as (iv) the critical role of institutional economics.

The Eclectic Paradigm juxtaposes the dynamically interdependent OLI advantages when approaching an investment choice (exit or voice strategy). Yet, since both the application of the triumvirate as well as the final investment decision are endogenous outcomes, and hence interrelated, their decision is based on the underlying investment motives. In other words, the process of international activity is based on an intertwining triumvirate of investment motives, OLI advantages, and entry mode choice. As a consequence, the fundamental questions of why firms engage in international production (O advantages), where firms engage (L advantages), and how firms organize the particular foreign activity (I advantages) must be complemented by a precedent and conceptual fourth question, videlicet what is the firms’ motivation to undertake fully internal foreign activity (investment motives) (drawing upon Cuervo-Cazurra and Narula 2015). I agree with Li et al. (2005) that the attention has to shift from a sole focus on international market failure (exogenous component) as foundation of O and I advantages, to include an endogenous component, i.e. investment motives (also Meyer 2015). This connection can be a potential link between strategy and the OLI determinants (Dunning 1988a).

Indeed, identifying and classifying investment motives is of vital importance, i.e. the basic precondition for FDI which relate to the respective asset the investing entity is seeking to acquire or access. Although Dunning (1998a, 2000) has recognized the important differentiation between asset exploitation and asset augmentation, the review of the literature suggested that the sub-categorization thereof yet lacks unambiguity (e.g., Moghaddam et al. 2014). Especially when focusing on the macro-level perspective, it seems that both Dunning’s typology of the four investment motives as well as the various adaptations provided a rather contextual, micro-level, perspective. Against this backdrop, I point towards Cuervo-Cazurra and Narula’s (2015) suggestion of conceptually driven envelopes of investment motives, albeit challenging their original categorization (based on Cuervo-Cazurra et al. 2015). Rather, appreciating Narula’s (2010) call for simplification, I suggest a trichotomy of motives, consisting of asset exploitation, asset augmentation, as well as a novel asset protection. This structure has various benefits. The novel asset protection motive incorporates the escape investment motive of Cuervo-Cazurra and Narula (2015) or Dunning (1993a), and may hereby also be directed at overcoming or counteracting potential competitive weaknesses. This threefold structure yet facilitates that both Dunning’s and Cuervo-Cazurra and Narula’s remaining motives could be combined under the traditional categorization of asset exploitation and asset augmentation, yet contrary to the former, does not restrict to a predefined sub-categorization.

Furthermore, the impact of both a dynamic and an institutional perspective to the traditional taxonomy was accentuated, yet both perspectives were integrated differently into the sub-paradigms. More precisely, whereas Dunning et al. (2007) and Dunning (2000) proposed a segmentation of O, L, and I advantages into static and dynamic components, yet neglecting their integration into the distinct nomenclature of each of the sub-paradigms, the institutional perspective has been integrated as distinct component into O and L advantages (e.g., Lundan 2010). However, although the dichotomous consideration of static and dynamic characteristics is imperative to the contemporary discussion, the need for a succinct terminological implementation is, at least, debatable. Especially when referring to the analysis of the literature, the dynamization is strongly contingent upon the exploitation (static dimension) and augmentation (dynamic dimension) of assets, hence, inevitably linked to the investment motives. At this, the dynamic context is moreover strongly associated to the exploration of knowledge and the advent of cooperative entry modes. As a consequence, the existence of a static and dynamic dimension should rather implicitly be rooted within the entire process of foreign activity. Furthermore, although we agree with the general macro-oriented contributions (e.g., Li-Ying et al. 2013; Lundan 2010; Dunning et al. 2007) that the traditional O, L, and I components remain central in IB and appropriate as sub-paradigms of the envelope, one adaptation protruded. The concept of LoF, introduced by Zhou and Guillen (2016) as well as Narula and Santangelo (2012), depicted a novel, yet valuable addition to the Eclectic Paradigm, describing the respective disadvantages and costs associated with foreign activity. It enabled a further critical scrutiny of the entire process of foreign activity and thus enhanced the validity of the Eclectic Paradigm.

4.3 Encapsulating the key propositions towards a state-of-the-art presenation

Finally, combined with new perspectives, the above key propositions and current state of knowledge are encapsulated into the following coherent state-of-the-art presentation of the Eclectic Paradigm (illustrated in Fig. 3). It also offers an initial approach to quantify and formalize the determinants.

The Eclectic Paradigm epitomizes three basic prerequisites that guide the explanation of foreign value-adding activities of MNEs. More precisely, it functions as a macro-level envelope that explains the process of international activity (intention). It offers a generic methodology, consisting of three sub-paradigms (O, L, and I advantages) along with associated investment motives (underlying context), that allow for a subsequent contextualized and micro-level analysis of different types of value-adding activities (level of analysis). At this juncture, I suggest a fourfold hypothesis of the Eclectic Paradigm, divided into a descriptive as well as three evaluative conditions. At first, the descriptive condition is shaped by the exogenous and endogenous motivation to engage in cross-border activities. This means, the foundation for MNE activity is based on the exogenous existence of international market failure and is endogenously induced through the firm’s strategic motivation to invest, namely to exploit, augment, or protect its assets. The investment motives (IMj) of a particular firm j, which build one important part of the firm’s strategic orientation (Sj), follow the question of what motivates the firm to go abroad. Thereupon, the extent, composition, spatial distribution, and form of an enterprise’s engagement in a foreign value-adding activity is dependent on the classification of three interdependent (evaluative) conditions:

Condition 1 is underpinned by the question why to go abroad and represents the strength and significance of a company’s possession of net, idiosyncratic firm-specific assets when exploring a new market. These O advantages comprise (i) the possession of superior assets (Oa), (ii) the capacity to capture transactional benefits, derived from the employment of common governance (Ot), and (iii) the exposure to institutions specific to the firm (Oi) (Lundan 2010; Lopes, 2010; Dunning 2000). The advantages are yet compared against the incurred additional costs associated with a foreign activity that reduce the general O advantages (O-specific liability of foreignness, LoFO) (Zhou and Guillen 2016; Narula and Santangelo 2012). In symbolic terms, let us assume that O advantages represent the dependent variable (denoted as Oj), indicating whether a firm j is in possession of O advantages that entail a competitive advantage over indigenous (and foreign) competitors. The respective Oa, Ot, Oi, and LoFO components influence the expected presence of Oj, which then evokes the following assumption:

with + and − denoting the direction (positive and negative, respectively) of the expected effect that each component has on the presence of Oj.

Assuming condition 1 is fulfilled, i.e. the possession of competitive Oj, the inter-firm transactions must be superior to external or contractual market transactions in order for the company to exploit/augment/protect its O advantages within the firm itself. That is, it must be more beneficial to internalize the firm’s advantages through expanding its operations to other markets than to externalize them by means of export or licensing agreements. At this, however, the additional costs and higher risks (governance and appropriation costs) of managing foreign investment in lieu of non-equity modes have to be factored in (LoFI) (Zhou and Guillen 2016; Li-Ying et al. 2013; Narula and Santangelo 2012; Lundan 2010). Condition 2, the existence of I advantages, thus, pursues the question of how to go abroad. By implication, the I advantages (denoted as Ij, dependent variable) of a firm j represent the form of international involvement which is shaped by the existence of superior inter-firm transactions (for differentiation purposes characterized as It) and LoFI. It follows the assumption:

with + and − denoting the direction (positive and negative, respectively) of the expected effect that each component has on the presence of Ij.

Lastly, assuming that conditions 1 and 2 are met, videlicet the firm’s possession of competitive Oj together with the advantageousness of exploiting or augmenting these within the enterprise itself (Ij), it must be more profitable for the firm to utilize its O advantages along with certain factor inputs outside its home country (Dunning 1988a). Those L advantages are based on non-transferable resources or assets (Lr) as well as institutional advantages (Li) supplied exclusively or in a specific quantity or quality by the particular foreign market. In addition, host country government induced detriments for foreign firms, such as discrimination costs, that diminish the ability to acquire both Lr and Li, have to be considered, too (LoFL) (Zhou and Guillen 2016; Eden and Dai 2010; Lundan 2010; Dunning 1995, 2000). Condition 3, hence, follows the questions of where to go. Accordingly, the strength of L advantages of a country k (denoted as Lk, dependent variable) is influenced by the existence and significance of Lr and Li against potential LoFL of firm j, thus evoking the following assumption:

with + and − denoting the direction (positive and negative, respectively) of the expected effect that each component has on the presence of Lk.

Yet, the omission of all three conditions being satisfied eliminates the validity of an FDI. Foreign markets would thus rather be served by two alternative routes. If a company initially possesses distinct ownership advantages, which are an essential precondition of any form of international involvement, their exploitation by contractual agreements, such as licensing, is suggested. If additional internalization advantages exist, the exploitation of both ownership and internalization advantages by exports is suggested. Consequently, only if all three conditions are met, i.e. the possession of distinct Oj, Ij, and Lk advantages, it is beneficial for a firm to engage in FDI (Dunning 2001). Here, incorporating the MNE’s IMj, a firm may choose between an exit or a voice strategy to react to market failure, i.e. hierarchical or cooperative entry mode choices (EMj). The EMj is contingent upon the respective single or mixed IMj, and hence depicts the other part of the firm’s strategic orientation (Sj). At this, both the strategic orientation and the OLI taxonomy are dynamically interrelated, whereas the former builds the descriptive component and the latter the evaluative components of the Eclectic Paradigm. The general, macro-level Eclectic Paradigm can finally be expressed by:

where the Eclectic Paradigm (EP) depicts the dependent variable; the independent variables are expressed by the corporate strategy (S), ownership-specific advantages (O), location-specific advantages (L), and internalization advantages (I); with # denoting the descriptive component and ± denoting the evaluative components along with j indicating the investing entity and k the host country.

The formulations of (1), (2), and (3) reflect the conjecture that the presence of the respective advantages is explained by several independent and contextual variables within a micro-level perspective. Therefore, we can conclude that the above state-of-the-art EP addresses the what, why, where, and how questions as the overarching macro-level envelope, whereas the EP* seeks to answer these questions case-specifically on a micro-level.

5 Concluding comments and an agenda for future research

This review on the development of the Eclectic Paradigm has illustrated that the wealth of rather separate and primarily conceptual advancements and ever-complex adaptations has fostered a continued fragmentation of the research field. A key element of IB theorizing, which serves the niche on the nexus between economics and business, is to incorporate and fuse perspectives across various disciplines (see Cantwell 2015; Chen et al. 2009; Dunning 1989a). However, similar to Kim and Aguilera (2016), we can recognize a multidisciplinary propensity amongst a vast number of the 66 articles reviewed instead of an interdisciplinary approach. Especially with the emergence of the constitutive micro-level perspectives to the wider agenda, the literature has generally missed the opportunity to integrate the contributions sufficiently into the existing paradigm. Instead, the emphasis has changed towards the firm level, leading to a conceptual shift in the notion regarding the normative intention and, as a consequence, the central role and level of analysis of the Eclectic Paradigm. Here, previous research has failed to clearly differentiate between addressing the overarching what, why, where, and how questions of internationalization (macro-level EP), and answering those questions case-specifically (micro-level EP*), which posits a contextualized configuration (see also Eden 2003). Meanwhile, simply adding general categories or variables as (normative) extensions may only meet the needs of certain markets and situations. Along with rather neglecting the L component and the fixation on MNEs as central focus of the Eclectic Paradigm, this adds fuel to the fire of dealing with the inherently increasing complexity of contemporaneous IB phenomena and of the Eclectic Paradigm specifically (see also Cantwell 2015; Eden and Dai 2010; Narula 2010). Thus, the subject-specific conversation increasingly lacks a consistent argumentation as well as a common ground. The consequence may very well be a ‘barbarization’ and further fragmentation of OLI-related literature. In particular, studies applying the Eclectic Paradigm based their research progressively on different versions. This does not only further increase the heterogeneous proliferation of the literature, but has a negative impact on the comparability of (empirical) results. On the one hand, studies referring to older versions of the Eclectic Paradigm (e.g., Dunning 1988a, 1993a) omit, for instance, the institutional perspective, as embedded into the OLI taxonomy in later publications (e.g., Dunning and Lundan 2008a). On the other hand, research built upon more recent contributions might miss out on understanding and factoring in a more holistic and formal modeling of the Eclectic Paradigm (as presented in the endowment/market failure paradigm of international production, see Dunning 1988a) or are forced to compile the components of the taxonomy from various sources. Hence, a meaningful development of the research field around the Eclectic Paradigm rests in part on a clear, systematic, topical, and uniform definition (Cantwell 2015; Eden and Dai 2010; Narula 2010), which orchestrates the extant knowledge, so that scholars are equipped with a holistic and coherent understanding of the taxonomy and its underlying purpose. It is here where I believe this review offers its greatest strength and contribution to theory and practice alike.

In particular, this review departs from recent studies dealing with the OLI taxonomy in that it is the first attempt to systematically contextualize and synthesize the widespread literature on the Eclectic Paradigm, corroborated by a rigorous and replicable methodological approach. By reconciling the heterogeneous development of the Eclectic Paradigm over the last 40 years, the study aimed at providing a more nuanced understanding and interdisciplinary approach. Broadening the object of investigation beyond the mere OLI taxonomy has delineated the boundary condition of the Eclectic Paradigm as meta-framework. I proposed a conceptual state-of-the-art framework of the Eclectic Paradigm which preserved the basic notion and richness of the original paradigm (especially Dunning 1988a), by uniquely unravelling its largely neglected normative intention, underlying context and level of analysis. In combination with integrating recent developments across disciplines, this macro-level framework (EP) equips future research with a conceptual foundation and starting point. More precisely, it presents a formal envelope of a decision-making process to approach the localization and type of cross-border activity dilemmas. As such, while remaining simple at the macro-level, the coherent structure enables a contextualized application and micro-level configuration of variables, sub-variables, and proxies to meet the needs of individual investment cases. Here, dividing the framework into descriptive and evaluative conditions allows us to emphasize several contributions and implications for a theoretical and practical application.

First, the descriptive condition depicts the foundation of MNE activity based on the existence of an exogenous (market failure) and endogenous (investment motive) motivation. By corroborating previous studies (e.g., Meyer 2015; Li et al. 2005; Dunning 2000), this segmentation facilitates the meaningful integration of the firm’s strategic motivation for foreign activities into the meta-framework. Together with the choice between an exit or a voice strategy to react to market failure, i.e. hierarchical or cooperative entry modes, the framework introduced the firm’s strategic orientation component, which enabled the integration of a strategic perspective into the macro-level. Second, by simplifying the investment motives into three overarching categories, i.e. asset exploitation, asset augmentation, and asset protection, we are now able to allow for the emergence of more contextualized and specific motives as compared to the prevailing and rather restricting predefined sub-categorization. Last, through an initial approach to quantify the evaluative conditions, the framework enables scholars and decision-makers to formalize and assess each component of the OLI taxonomy and to derive refutable hypotheses. Here, to evaluate the respective dependent variables of the OLI taxonomy, a set of meaningful proxies can be derived and case-specifically adapted for each of the corresponding independent variables. Moreover, integrating the concept of liability of foreignness increases the analytical relevance of the proposed framework, since evaluating each of the dependent variables is contingent upon the total utility derived from its independent variables. That is, it factors in the incurred additional costs and risks associated with FDI in comparison to trade. This paves the way to test foreign investment cases empirically, while at the same time ensuring the comparability of findings due to the homogenous basis. This need was identified repeatedly within the articles reviewed.

As a second step, we must now shift focus towards reporting on context, which, concomitantly, creates possibilities to generate and deduce novel ideas and brings originality to the discussion (see Delios 2017). At this, scholars should be receptive to confine their research to more descriptive and exploratory studies in order to understand the peculiarities of the underlying institutional, economic, and social structures that shape the determinants and processes of FDI. For instance, reporting context means to enter the country level by classifying region- or industry-specific cases into coherent clusters, and to explore the idiosyncrasies (i) of a specific target country (for studies on inward FDI), or (ii) of the respective MNEs’ home country (for outward FDI). At this juncture, attention shall be drawn to the contribution of Buckley et al. (2007). In their study on Chinese outward FDI, Buckley and his colleagues went beyond a generic economic modelling of FDI determinants to provide a comprehensive contextualization on the specificities of Chinese capital market imperfections, ownership advantages of Chinese MNEs and the associated institutional factors influencing Chinese outward FDI. By aligning macro- and micro-level elements, the study serves as an example for future empirical research that conceptually draws upon the Eclectic Paradigm. Consequently, as further contextualized research is introduced, the level of heterogeneity decreases. Hence, in the light of the above, the study concludes by briefly delineating a subjective view on what I feel might be fruitful further avenues to investigate, focusing particularly on enhancing the applicability of the Eclectic Paradigm to the context of emerging markets.