Abstract

Objectives

Approximately 95 % of convictions in the United States are the result of guilty pleas. Surprisingly little is known about the factors which judges, prosecutors, and defense attorneys consider in these decisions. To examine the legal and extralegal factors that legal actors consider in plea decision-making, we replicated and improved upon a 40-year-old study by asking legal actor participants to review a variety of case factors, and then make plea decisions and estimate sentences for pleas and trials (upon conviction).

Methods

Over 1,500 defense attorneys, prosecutors, and judges completed an online survey involving a hypothetical legal case in which the presence of three types of evidence and length of defendant criminal history were experimentally manipulated.

Results

The manipulated evidence impacted plea decisions and discounts, whereas criminal history only affected plea discounts (i.e., the difference between plea and trial sentences). Defense attorneys considered the largest number of factors (evidentiary and non-evidentiary), and although legal actor role influenced the decision to plead, it did not affect the discount.

Conclusions

In replicating a landmark study, via technological advances not available in the 1970s, we were able to increase our sample size nearly six-fold, obtain a sample representing all 50 states, and include judges. However, our sample was nonrepresentative and the hypothetical scenario may or may not generalize to actual situations. Nonetheless, valuable information was gained about the factors considered and weighed by legal actors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The overwhelming majority— 94–97 % —of state and federal convictions in the US are the result of guilty pleas (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2013; Oppel 2011). In these cases, defense attorneys must decide how to advise clients, prosecutors must decide what plea offers to make and judges must decide whether to accept or reject the negotiated plea deal made between the two attorneys and the defendant (as well as consider many other factors relevant to voluntary, knowing, and intelligent decision-making). Surprisingly, very little is known about the factors which legal actors consider relevant to plea decisions. Thus, the purpose of the present research is to first determine what legal and extralegal factors defense attorneys, prosecutors, and judges consider when making plea offer/acceptance decisions, and second to examine the degree to which certain factors influence plea decision-making by legal actor type. This is accomplished using an innovative extension of an approximately 40-year-old study, entitled “Plea Bargaining in the United States,” in which Miller et al. (1978) administered a hypothetical plea bargaining simulation game to attorneys (see generally, McDonald 1979; McDonald and Cramer 1980, and below for more detail).

Plea decision-making

A major proposed mechanism for plea decision-making is the “shadow of trial” model (Mnookin and Kornhauser 1979; Nagel and Neef 1979). In this model,Footnote 1 decisions to offer, accept, or reject pleas are derived from the perceived likelihood of a trial outcome (Kalven and Zeisel 1966; Landes 1971; Smith 1986). That is, in theory, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and defendants base their plea decisions on what evidence they anticipate jurors will hear and weigh. Indeed, in a study of defense attorneys responding to a hypothetical scenario, Edkins (2011) found “likelihood of conviction based on evidence” to be the most important factor in their decisions to recommend plea bargains.

In addressing plea decision-making within the “shadow of trial” model, we must ask: what drives convictions at trial? The answer to this question is most often “the strength of the evidence” (SOE) (e.g., Devine et al. 2009). It is therefore simple inference to conclude that if SOE drives the finding of guilt at jury trials, it will also drive guilty pleas. The few studies that have investigated the role of SOE in pleas have focused on the existence of a plea bargain, rather than its value (Emmelman 1998); that is, the amount of the discount or the distance between the plea and trial sentences (if convicted at trial). However, the plea bargain decision explicitly combines the “conviction” decision with the “sentencing” decision. Bibas (2004; see also Stuntz 2004) cogently argued that structural (e.g., poor lawyering, agency costs) and psychological considerations (e.g., use of heuristics, differences in risk aversion) in plea bargains have sizeable influence, and that when these considerations are accounted for, the “shadow of trial” model falls apart. Indeed, organizational theories of legal cultures posit an opposite pattern to the shadow model; that is, exogenous events and internal culture shape the practice and interpretation of law in jurisdictions (see Edelman et al. 2010). The rational actor “shadow of trial” model stands in stark contrast to the cultural traditional model, which highlights the influence of social movements and organizations (see Morrill and Rudes 2010).

In an empirical test of the “shadow of trial” model, Bushway and Redlich (2012) found that whereas the model appeared to “work” in the aggregate—such that the probability of conviction and the estimated plea discount value were found to be near-identical—the model was unsupported at the individual-defendant level. Further, they showed “that although evidence does an excellent and predictable job of explaining the probability of conviction for those who go to trial, evidence cannot similarly explain variation in [our] estimates of the probability of conviction for those who pled guilty” (p. 451). Indeed, alternatives to the shadow of trial model suggest that plea negotiations are at least partially based on factors that have little to do with evidence, including caseload, amount of experience, courtroom workgroup relationships, and individual differences between legal actors (Bibas 2004). Thus, a clear next step is to determine what factors, both evidentiary and non-evidentiary, can help explain the variation in plea decision-making.

Evidentiary factors

A good working definition of “strength of the evidence” is lacking (Devine et al. 2001). There are many different qualifying adjectives to describe evidence, including direct and indirect. According to Heller (2006), direct evidence is evidence that “proves a fact without an inference or presumption and which in itself, if true, establishes that fact” (p. 248). In contrast, indirect (or circumstantial) evidence is evidence “from which the fact-finder can infer whether the facts in dispute existed or did not exist” (p. 250).

Confession evidence, a quintessential form of direct evidence, is considered by many to be the most potent form of evidence (see Kassin et al. 2010), probably because they are statements against one’s interest. One legal scholar claimed that confessions make the introduction of other types of evidence superfluous (McCormick 1983). Kassin and Neumann (1997) tested this notion by manipulating whether mock jurors considered confession, eyewitness, or character evidence. Across three separate studies and several crime types, confessions significantly increased guilty verdicts in comparison to the other types of evidence. Thus, there is some support that jurors weigh confessions more heavily than eyewitness testimony. However, eyewitness evidence, another form of direct evidence, is also highly valued, particularly when contrasted with the lack of an eyewitness or circumstantial evidence. Mock jury studies that have manipulated corroborating eyewitness testimony have noted up to a 70 percentage point difference between acquittal and guilty verdicts when eyewitness testimony is and is not present (Devine et al. 2001; Greene 1988; Savitsky and Lindblom 1986).

But what about DNA evidence, an indirect form of evidence? On the one hand, it has been called “the gold standard” of evidence (Thompson 2006) and has been instrumental in both convicting the guilty and exonerating the innocent. In the National Academy of Sciences (2009) report on forensic science, DNA was distinguished from other questionable forensic science analyses. The report stated, “DNA typing is now universally recognized as the standard against which many other forensic techniques are judged. DNA enjoys this preeminent position because of its reliability” (p. 5–3). In investigating this “gold standard” status, Lieberman et al. (2008) asked college students and jury members to rate the accuracy and persuasiveness (towards guilt) of different types of evidence, including DNA, suspect confessions, and eyewitness testimony. For both students and jurors, DNA was viewed as the most accurate (about 95 % accurate) and most persuasive (about 94 %). In comparison, confession evidence was rated as about 75 % accurate and 88 % persuasive, and eyewitness testimony as 66 % accurate and 72 % persuasive.

On the other hand, there is evidence from known wrongful conviction cases that confession evidence “trumps” DNA evidence (Kassin 2012), as well as studies indicating that mock jurors do not understand and/or incorrectly apply DNA-related statistical probabilities (Koehler 2001; Schklar and Diamond 1999). In the present study, we examine whether the presence of confession, eyewitness, and/or DNA evidence influences plea decision-making among legal actors. We also examine whether length of defendant’s criminal history, a non-evidentiary factor at trial, is influential.

Non-evidentiary factors

Non-evidentiary factors also play a role in jury decision-making. Over the past 50 years, studies have demonstrated that myriad factors influence jury verdicts, including juror and defendant demographics, attorney experience, and procedural aspects such as comprehensibility of jury instructions (Devine et al. 2001). Similarly, research has indicated that factors such as race and gender influence the acceptance (i.e., the existence) of pleas by defendants (Albonetti 1990; Elder 1989; Frenzel and Ball 2007; LaFree 1985) and prosecutorial dismissal decisions (Kellough and Wortley 2002).

Prior criminal history of the defendant has also been shown to affect trial and plea outcomes. Devine et al. (2001) reviewed seven juror decision-making studies that examined the influence of prior criminal history. Six of the seven found that trial conviction rates were higher when the defendant had prior arrests/convictions versus none. Because of the potential for prejudice associated with known criminal histories, the jury often does not hear of the defendant’s past, though there are exceptions relating to modus operandi and pattern behaviors (e.g., People v. Falsetta 1999). Thus, at trial, prior criminal history is often considered an extralegal factor, or a factor outside of or beyond what is legally relevant. In the original Miller et al. (1978) research replicated here, defendant’s past criminality was considered an extralegal factor.

In plea contexts, however, prior criminal history is not an extralegal factor. Unlike jury members, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and judges are typically aware of the defendants’ prior record in plea decisions. Indeed, it is one of two main factors used for sentencing guidelines in most jurisdictions (Tonry 1987) and an important factor in determining sentencing outcomes (Mitchell 2005; Spohn 2000). Having prior arrests and/or convictions often alters the resultant plea offer. For example, Kutateladze et al. (2015) determined that felony drug defendants in New York City with prior arrests were offered plea deals with significantly longer sentences than those without prior arrests. Thus in the present study, as in Miller et al. (1978), we examine how length of prior criminal history affects the willingness to plea and plea values, holding other factors constant.

In the present study, we also examine other non-evidentiary factors, including several related to the jurisdiction and the legal actor. One oft-cited factor believed to influence plea decision-making is caseload (i.e., the number of cases assigned per legal actor or to the system as a whole). Increased caseload pressure on the parts of judges and attorneys is believed to lead to increased plea bargaining. For example, Johnson (2005) found that courts with heavier caseload pressure were more likely to grant downward sentence departures than those with lighter caseload pressures (see also Ulmer and Johnson 2004). However, Nardulli (1979) did not find caseload (either the judge’s or the system’s caseload) to affect whether the case was dismissed or pled out, or the sentence length if there was a plea. Further, years employed in the legal system and how often legal actors plead cases could also plausibly affect decision-making. In comparison to attorneys who almost never go to trial, those who go to trial more often, for example, may be less likely to first accept or offer a plea deal, and second, accept or offer plea deals with larger or smaller discounts. However, Goodman-Delahunty et al. (2010) did not find that an attorneys’ experience affected their ability to accurately forecast case outcomes.

Legal actor plea decision-making

If plea decision-making truly occurs in the shadow of trial, then type of legal actor (defense attorney, prosecutor, or judge) should not affect what factors are considered. For instance, prosecutors and defense attorneys should both be concerned with a defendant’s confession, given its potential weight at trial. Pezdek and O’Brien (2014) compared defense attorneys’ and prosecutors’ plea decisions in the context of differing eyewitness scenarios, and found that although the two attorney types did not differ in perceptions of the influence of eyewitness identifications, only defense attorneys were found to make plea decisions consistent with the shadow of trial model (see also Bushway et al. 2014).

Pezdek and O’Brien (2014) also found that, in general, defense attorneys were much less willing to endorse the plea option than prosecutors. And not surprisingly, as the probability of conviction increases, prosecutors have been found to become less willing to plea bargain, whereas defense attorneys become more willing (McAllister and Bregman 1986; see also, Kramer et al. 2007). Finally, of importance to the present study, Edkins (2011) asked defenders to self-report what factors were important to them in plea decisions. She reported that, by their own account, defense attorneys do not consider extralegal factors (personal relationship with the prosecutor and judge, believing that the defendant is guilty, and current caseload) but do consider legal ones (e.g., the likelihood of a conviction based on the evidence and the severity of the sentence if convicted at trial, compared to the sentence offered in a plea deal).

The present study partially replicates research conducted by Miller et al. (1978). In the original set of studies, Miller and colleagues coded case files from six U.S. cities, observed in-court hearings, and administered a hypothetical plea-bargaining simulation game to attorneys (see generally, McDonald 1979; McDonald and Cramer 1980). In the simulation game, Miller et al. provided prosecuting (n = 136) and defense attorneys (n = 140) with 43 case facts about a robbery and a burglary. They manipulated strength of the evidence (labeled weak or strong), and the defendant’s prior criminal history (long or short), thus creating four conditions to which attorneys were randomly assigned. Attorneys were briefly informed about the case, including that the defendant was charged with armed robbery and was willing to plead guilty for a consideration. Then, attorneys were asked what additional information they needed in order to make an informed decision. Miller et al. met individually with attorneys and utilized an opened folder with the tops of 43 index cards showing. At the top of each card were written titles, such as “Defendant’s Sex” and “Trial Judges’ Reputation for Leniency.” Attorneys were instructed to select and view the cards that they would normally consider, and to stop viewing cards when they believed that they had enough information to make a decision and recommend a sentence.

On average, significant differences arose by attorney type. For example, defense attorneys considered more facts than prosecutors, although both tended to examine the same three facts (basic case information, prior record, and case strength) early in their considerations. Further, prosecutors were more likely to enter into plea bargains than defense attorneys, though this was qualified by case type and the manipulations. Specifically, when the case was robbery (but not burglary), the presence of strong evidence and a lengthy prior record increased attorneys’ willingness to plea. With regard to this finding, Rossman, McDonald, and Cramer (1980) stated that it is “particularly significant in that it suggests that the estimate of probability of conviction is not based only on strength of the case. Rather the estimate is colored by the factor of prior record. Prior record should be irrelevant, however, in that a judge or jury in trial would not likely have access to such information” (pp. 95–96).

The present study (in addition to Bushway et al. 2014) seeks to replicate and improve upon the original study in several ways. First, this study takes advantage of computers and the internet to increase the number of responses and facilitate more sophisticated manipulations and detailed data collection. Second, concerns have been raised about the Miller et al. data. For example, in discussing these data, McAllister and Bregman (1986) state, “Perhaps the most serious problem involved the manipulation of the strength of the prosecutor’s case; many subjects perceived the weak case in fact to be a strong case” (p. 687). The SOE manipulation consisted of the label “strong case.” In the present study, rather than using this label, we manipulate the presence of three evidence types (confession, eyewitness identification, and DNA match) as well as length of the defendant’s criminal history.

Third, the Miller et al. data may have suffered from order effects for the selection of case facts. The factors examined by almost all (91 % or more) prosecuting and defense attorneys were basic facts of the case, evidence, and defendant’s record (Rossman et al. 1980). However, these three factors always appeared in the same positions. In the present study, using a sophisticated online survey unavailable in Miller et al.’s time, we eliminate possible order effects by randomly ordering the facts for each participant viewing (more details below). Finally, we significantly increased the sample size of defense attorneys and prosecutors, as well as included a sample of judges. If bargaining is done in the shadow of trial, it stands to reason that judges are an important part of the plea process. Indeed, Lacasse and Payne (1999) found evidence of defendants bargaining in the shadow of the judge. Further, there are indications that judges are reluctant to go against the plea recommendations of prosecutors (Heumann 1981), and negotiated pleas may represent what prosecutors and defense attorneys expect the judge to accept. The perceived leniency or harshness of a judge has also been found to be an important consideration in plea negotiations; in the Miller et al. study, 70 % of defense attorneys, but only 29 % of prosecutors, chose this factor as a consideration (Rossman et al. 1980).

The present study

The present study answers two primary questions: 1) What factors do defense attorneys, judges, and prosecutors consider in plea decision-making, and do differences by legal actor type emerge? and 2) Do certain factors (i.e., confession, eyewitness identification, and DNA evidence, and defendant’s criminal history) influence plea decision-making by legal actor type? Based on the research reviewed above, we formulated hypotheses about the differences between legal actors and about the legal and extralegal factors under study. With regard to legal actor, we expect that in comparison to judges and prosecutors, defense attorneys will 1) consider more factors overall, and more legally relevant factors; and 2) be significantly less likely to advise pleas. With regard to evidentiary and non-evidentiary factors, based on the shadow of trial model, we expect that the presence of a confession, positive eyewitness identification, and DNA match will increase legal actors’ willingness to plea, but lower the value of the plea (that is, the discount or the bargain). We also anticipate that DNA evidence will be the most impactful on plea decisions compared to eyewitness and confession evidence (see Lieberman et al. 2008). Because Bushway et al. (2014) found that judges did not bargain in the shadow of trial, we anticipate that whereas defense attorneys’ and prosecutors’ plea decisions and plea discounts will be impacted by the manipulated evidence, judges’ decisions will not. Finally, lengthier defendant criminal histories are expected to increase the willingness to plea (Rossman et al. 1980) but decrease the size of the plea discount.

Methods

Participants

Participants included defense attorneys, prosecuting/state attorneys and judges. Initially, 2,593 individuals viewed the survey, including 1,247 defense attorneys (48.13 %), 729 judges (28.14 %), and 615 prosecutors (23.74 %). Of the 2,593 people who viewed the survey, 1,664 completed it, for a completion rate of 64.17 %. Survey completion differed across roles, χ 2(2) = 46.96, p < .0001; the completion rate for judges was 54.46 % in comparison to completion rates of 69.77 % and 64.55 % for defense and prosecuting attorneys respectively. However, for each of the three groups, differences between completers and non-completers did not generally emerge (e.g., on race, gender, age, or years of practice) (see Bushway et al. 2014).

Of the 1,664 participants who completed the survey, a total of 79 participants were dropped from the final sample because they spent less than 5 min on the survey,Footnote 2 answered less than half of the manipulation-check questions correctly,Footnote 3 or answers to key questions were illogical. Our final sample thus consisted of 1,585 participants representing all 50 states and the District of Columbia: 378 prosecutors (23.85 %), 835 defense attorneys (52.68 %), and 372 judges (23.47 %). By comparison, the original Miller et al. (1978) study had 276 respondents. Our participants were predominately male (69.52 %) and white (90.59 %); age ranged from 24 to 80 years old with a mean of 48.32 (SD = 11.75). According to a survey done by the American Bar Association (2012) of more than 1.2 million licensed lawyers, 70 % are male, 88 % are white, and the median age is 49. Thus, our sample demographics on these three characteristics approximate national figures quite well. Respondents had an average of 13.54 years of experience (SD = 9.93) in their current role, ranging from less than 1 year to 57 years. Legal actors significantly differed by age, gender, cases handled per year, and county size but not by percent non-white or percent of cases pled annually (see Bushway et al. 2014, Table 1). In the below analyses, we control for these differences when appropriate.

Online survey instrument

The survey began with questions pertaining to demographics (e.g., gender, age, race), career (e.g., other roles in legal system, length of experience) and jurisdiction (e.g., state) Participants then underwent two primary tasks. First, as in the original Miller et al. study, participants were asked to imagine that a less-experienced junior colleague (of the same legal actor type) had come to them for advice about a case in their jurisdiction. They were also informed that the defendant in the case had been charged (but not indicted) with Armed Robbery in the 1st degree, that the maximum penalty is 25 years in prison, and that the defendant is willing to plead guilty for consideration. They were then presented with basic facts about the hypothetical robbery (see Bushway et al. 2014, for verbatim script).

All participants were presented with a set of 31 labeled fact files (in addition to the ‘basic facts’), each containing a different piece of information pertaining to the hypothetical case (e.g., ‘Defendant’s Race,’ ‘Alibi,’ etc.), which they could choose to view at their discretion. Folder labels were verbatim the same regardless of condition. A version of what participants viewed is in Appendix 1. As in the original study (Miller et al. 1978), participants were instructed to select and view the facts that they would normally consider, and to stop viewing the files when they believed they had enough information to make a decision. Of importance, the order of the facts was randomized for each participant to avoid primacy and other order effects. This randomization was successful: the position of checked folders did not differ significantly across the 31 randomized folders and did not differ significantly from the expected average position of 15.5 (χ 2 = 0.26, p > .999). The folder randomization was also checked to determine if it was successful within roles, which it was found to be.

Four factors were manipulated to create 16 separate conditions: 2 (presence vs absence of positive eyewitness identification) x 2 (presence vs absence of a confession) x 2 (presence vs absence of a DNA match) x 2 (short vs long criminal history of the defendantFootnote 4). Thus, for example, when participants clicked on the folder, ‘Confession Statement,’ they either read that the defendant confessed to the police or did not confess. Furthermore, additional evidence was available to all participants, including: (1) that there were no other witnesses to the crime; (2) the defendant’s account was that he was walking home from the movies at the time of the crime, but not near the location of the offense, and that he claimed not to have confessed to the police; and (3) that the victim’s identification and credit cards were found 5 feet from the defendant at the scene of arrest and the defendant had $116 in cash, including a $100 bill. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the 16 conditions.

After reading the case and viewing the facts they wished to consider, participants underwent the second primary task, which was to answer questions based on the scenario. First, they were asked to estimate the probability of conviction (POC) if the case were to go to trial. This decision was made by selecting a point on a line that ranged from 0 to 100 %. Participants were then asked to assess the average sentence for a trial conviction, as well as the least and most severe sentences the defendant in the hypothetical case could receive if convicted at trial. A drop-down menu was present which included a range of 1 month to 25 years, 11 months. Finally, respondents were asked to indicate either the most severe (defense attorneys), the least severe (prosecutors), or average sentence (judges) that would be acceptable for a plea deal (from 1 month to 25 years, 11 months), and what their likely course of action would be in this case. Participants were instructed that a plea sentence of 0 months–0 years was not allowed. Judges and defense attorneys were given the options of refusing or accepting a guilty plea. Prosecutors were given the options of not offering a plea deal and taking the case to trial, offering a guilty plea, or dismissing the case. Respondents were then asked manipulation-check questions about the evidence.

Procedures

To recruit participants, we relied primarily on email requests. We obtained collaboration from several national organizations, including the American Bar Association, the American Judges Association, the National Judicial College, the Association of Prosecuting Attorneys, and the National Legal Aid and Defender Association. We also worked with numerous state-level organizations, including the State Bars of South Carolina, Wisconsin, and Montana, the Pennsylvania District Attorneys Association, and the New York State Defenders Association. These organizations facilitated contact with their members either by forwarding the survey link on our behalf, providing email lists for our use, and/or by placing a description about the study and survey link on their website. In addition to national and state organizations, we obtained collaboration from over 30 district attorney and public defender offices, and contacted individual prosecuting and defense attorneys and judges through public email lists available online.

Email invitations described the purpose of the study, and that it was anonymous and voluntary. A link to the survey website was included, which persons could choose to follow. No financial or other incentives were offered to participate. After viewing and agreeing to an informed consent form, participants willing to be in the study were asked to indicate their current role (i.e., defense attorney, prosecutor/state attorney, or judge), which framed the questions appropriately. On average, participants took about 22 min to complete the survey.

Results

Analyses concentrate on two questions: 1) what factors do legal actors consider in plea decision-making?, and 2) whether certain factors influence plea decision-making. To address the second question, two main dependent measures were used for analyses: the plea decision and plea discount (see below).

What factors do legal actors consider in plea decision-making?

Overall, the average number of individual folders viewed was 20.91 (SD = 9.26). However, the number viewed differed significantly by legal actor role (see Table 1 for means). Defense attorneys, on average, viewed the most folders, compared to prosecutors and judges. Differences between the three actor roles were all significant. Appendix 2 presents the percentage of participants, overall and by role, who examined each of the 31 folders. Confession Statement was the most viewed folder (at 94 %), whereas the backlog of the judge’s docket was the least (at 43 %). However, the average position Confession Statement was viewed was 6.75, indicating that about six factors were viewed prior to clicking on Confession Statement (see Appendix 2). The factor examined first most often by 21.9 % of participants was Additional Evidence. In a close second was Defendant’s Prior Record, with 19.4 % of participants examining it first. For the manipulated evidence variables, 13.1 % chose Confession Statement first, whereas Eyewitness Identification and DNA Evidence were each examined first by 5.5 % of participants.

The 31 folders and the number of times they were viewed were entered into a principal components analysis with varimax rotation. Varimax rotation, the most commonly used rotation method, was selected because it maximizes the sum of the variances of the squared loadings orthogonally (Kerlinger and Lee 2000). Three factors with eigenvalues over 1.0 emerged, accounting for 54.86 % of the variance. The factors are listed in Table 2. Factor 1 was labeled ‘Non-evidentiary factors’, and included several aspects about the defendant, such as his or her race/nationality/ethnicity and aliases, and items about the process, such as probability of continuance and judge’s reputation for leniency. Factor 2 was labeled ‘Evidentiary Factors’, and included the three pieces of manipulated evidence, additional evidence, physical evidence, etc. Factor 3 was labeled ‘Defendant Characteristics’, and included the defendant’s drug use, physical and psychiatric health, and general characteristics. Mean composite scores were created from these three factors. All had sufficient internal reliability, with αs ranging from .74 to .95.

These three composite scores were then entered into a series of one-way analyses of co-variance, controlling for the number of total folders viewed, with legal actor role as the independent variable. Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 1. Regardless of role, Evidentiary Factors were more often examined than Non-Evidentiary Factors and Defendant Characteristics.

When examining differences between legal actor roles, for Non-Evidentiary Factors, significant differences were found between all three groups. Even after controlling for the number of total folders viewed, defenders viewed significantly more folders in this category than judges and prosecutors (see Table 1). The difference between judges and prosecutors was less robust (p = .03), with prosecutors viewing more than judges.

Defense attorneys and prosecutors were equally likely to examine Evidentiary factors, both significantly more so than judges. For Defendant Characteristics, perhaps unsurprisingly, defenders were the most likely to consider these aspects of the defendant, and were significantly more likely to do so than both judges and prosecutors, who did not differ from one another (see Table 1).

Do the factors impact plea decision-making among legal actors?

Before examining plea decisions and plea discounts, we first analyzed respondents’ perceived probability of conviction at trial by legal actor. Legal actor role did not significantly influence probability of conviction, F(2, 1582) = 1.38, p = .25, partial η2 = .002. Average probability of conviction ratings were 63.69 % for defense attorneys, 66.26 % for prosecutors, and 64.03 % for judges. Interestingly, the rate of conviction in large urban U.S. counties has consistently been right around 65 % (see http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbse&sid=27), and thus these perceived probabilities are in accordance with actual conviction rates. In interpreting findings of plea decisions and values, it is important to note that differences were not found by legal actor for probability of conviction. In addition, as described above, not all participants viewed the manipulated folder conditions. Thus we did analyses with the entire sample and with the subset who viewed the manipulated confession, eyewitness, DNA, and defendant criminal history folders (n = 1168, 73.7 % of total sample).

Plea decision

As in real life, the majority of our sample chose the plea option rather than go to trial: 86 % overall chose plea. Defense attorneys were the least likely to select plea (82 %) in comparison to judges (93 %) and prosecutors (91 %). Prosecutors were the only group to have the option of dismissal, though only 6 % (n = 24) chose this option. First, to determine whether the manipulated evidence and criminal history variables influenced plea decision-making, a series of chi-squares were computed for the entire sample, and for the three legal actor roles separately. As shown in Table 3, the presence of a confession, positive eyewitness identification, and DNA match increased the willingness to select the plea option. For example, when a confession was present, the odds of pleading (versus trial) was 1.6 times greater than when a confession was not present (95 % CI = 1.17–2.20). However, these findings were largely driven by the defense attorney sample (i.e., the sample with the largest n) who demonstrated the same pattern. In general, the evidence (and defendant’s criminal history) did not influence judges’ and prosecutors’ plea decisions, with one exception. The presence of an eyewitness significantly increased prosecutors’ willingness to plead compared to when an eyewitness was absent. Finally, the defendant’s criminal history did not influence the plea decision.

To further determine what predicted this decision and to account for differences by legal actor type, a logistic regression was conducted, first entering legal role and characteristics of respondents, and then entering the manipulated case factors and the total number of factors viewed. This analysis was significant, χ 2(14) = 145.86, p < .0001; Nagelkerke R2 = .24, with 88.2 % correctly classified.

Overall, results were quite similar to those found in the chi-square analyses (Table 4). Although legal actor type influenced plea decision-making, other legal actor characteristics (such as county type), were not impactful. The manipulated evidence predicted plea decisions. The presence (vs absence) of a confession, eyewitness ID, and DNA match raised plea rates by 5, 10, and 7 percentage points respectively. That is, when these pieces of evidence were present, legal actors were significantly less willing to advise the risk of trials. In contrast, the defendant’s prior history (short vs long) and the number of folders viewed did not influence plea decisions.

The same logistic regression was conducted again but only including the subset of participants (n = 1,168, 73.7 %) who viewed all of the manipulated folders of confession, eyewitness identification, DNA match, and defendant prior criminal history. Results remained identical, such that defendant prior history was not influential, and legal actor type and the three types of evidence remained highly influential.

Plea discount

Plea discount was calculated as the percent difference between participants’ answers to the maximum trial sentence and the plea sentence; greater numbers indicate ‘better’ plea offers (i.e., larger discounts). For example, if the maximum trial sentence was 15 years and the plea sentence was 3 years, the plea discount would be .80 (i.e., (15−3)/15 = 80 % discount). Plea discount ranged from 0 to 100 % (SD = 20.4) among individual respondents, and ranged from 57 to 78 % across the 16 conditions.

First, we conducted a 2 (confession) x 2 (eyewitness ID) x 2 (DNA match) x 2 (prior criminal history) x 3 (legal actor role) ANOVA, using plea discount as the dependent variable. Significant main effects of eyewitness ID (F(1, 1521) = 21.71, p < .0001, partial η2 = .01), confession (F(1, 1521) = 13.28, p < .0001, partial η2 = .01), prior history (F(1, 1521) = 38.33, p < .0001, partial η2 = .03), and DNA match (F(1, 1521) = 24.86, p < .0001, partial η2 = .02) were found. When these types of evidence were present, plea discounts were significantly larger. The main effect of legal role was not significant, however. The average plea discount value for defenders, prosecutors, and judges was 67, 64, and 65 % respectively.

The eyewitness ID main effect was qualified by two significant 2-way interactions, involving the presence of a confession, F(1, 1521) = 8.19, p = .004, partial η2 = .01, and legal actor role, F(2, 1521) = 4.12, p = .02, partial η2 = .01. No other significant main or interaction effects were found. First, when a confession was not present, the influence of having an eyewitness ID remained significant; that is, without an ID (and no confession), the plea discount was 72.0 % (SD = 18.3) versus with an ID (and no confession), the discount was 63.2 % (SD = 21.2), partial η2 = .05. However, when a confession was present, plea discounts when an ID was (62.4 %, SD = 19.6) and was not (65.1 %, SD = 2.16) present were not significantly different, partial η2 = .004.

Second, when an eyewitness ID was absent, plea discount rates for defense attorneys, judges, and prosecutors were 69.9 % (SD = 20.6), 65.3 % (SD = 19.0), and 68.9 % (SD = 20.8) respectively. Only rates between defense attorneys and judges were significantly different (p = .01). When an eyewitness ID was present, plea discount rates for defense attorneys, judges, and prosecutors were 63.9 % (SD = 21.4), 64.3 % (SD = 15.8), and 59.1 % (SD = 21.8) respectively. Here, prosecutor ratings were significantly different from defense attorneys (p = .01) and judges (p = .01) (whom did not differ from each other, p = .85). Within legal actor role, the presence of an eyewitness ID significantly impacted plea discount rates for defense attorneys and prosecutors (both p < .001). Judges’ rates, however, were not significantly impacted by the presence of an ID (p = .57).

In order to account for demographic and experiential differences between the legal actor types, we next conducted a multivariate regression using plea discount as the dependent variable and the same independent variables in the above logistic regression, F(14, 1477) = 11.49, p < .0001; R2 = .10. As found in the dichotomous plea decision analysis, the three types of manipulated evidence were strong predictors (Table 5). The presence of a confession, eyewitness identification, and DNA match all served to reduce the bargain by 4 to 6 percentage points. In addition, a lengthy criminal history of the defendant reduced the bargain value by 7 percentage points.

As found with the ANOVA, legal actor role itself did not influence plea discounts, but legal actor traits were influential. Specifically, legal actors with more years of experience and those from suburban and rural jurisdictions (in comparison to those from urban jurisdictions) had larger discounts. Finally, the number of folders viewed did impact plea discount rates, such that those who examined more folders had lower discounts.

Again, we reran the regression analysis with only participants who viewed the four manipulated folders. Legal actor type remained nonsignificant and the four manipulations remained highly significant. However, the effect of suburban (in comparison to urban), which was marginally significant, as well as number of years of experience, were now nonsignificant. Number of folders viewed and rural (in comparison to urban) remained significant and in the same direction.

Discussion

In the present study, we replicated and extended a seminal study of plea decision-making, addressing two primary questions. First, what factors do legal actors examine when making plea decisions, and does examination differ by legal actor type? Second, do certain evidentiary and non-evidentiary factors influence the decision to accept, offer, or advise a plea, and the value of the plea itself?

What factors do legal actors consider in plea decision-making?

As did Miller et al. (1978) nearly 40 years ago, we found that defense attorneys, in comparison to prosecutors (and judges, whom Miller et al. did not examine), considered a larger number of factors in the hypothetical plea decision-making scenario, supporting our first hypothesis posited above. On average, defense attorneys examined 23 of the 31 factors, whereas prosecutors and judges viewed fewer than 20. Interestingly, however, the attorneys from the Miller et al. dataset viewed fewer folders than did respondents in our sample, even though Miller et al. respondents had more folder viewing options (i.e., 43 versus 31 in our sample). Specifically, the Miller et al. prosecutors viewed an average of 12.9 folders and defenders viewed 17.2 (see Rossman et al. 1980). It is possible that the differences are attributable to the methods used. That is, whereas our respondents viewed folders on their computer by themselves, respondents in the Miller et al. study viewed hard-copy folders with researchers present. This anonymous online method may have allowed participants to view more extralegal factors (such as defendant race and judges’ reputation for leniency) than would have been socially desirable with a researcher watching.

Even after controlling for the total number of folders viewed, defense attorneys viewed significantly more Non-Evidentiary Factors (Factor 1) and Defendant Characteristics (Factor 3). However, defense attorneys and prosecutors were equally likely to view Evidentiary Factors (Factor 2), and both groups did so near ceiling levels (see Table 2). Thus, although Edkins (2011) sample of defense attorneys reported that they mostly considered legally relevant factors, in our study, defense attorneys, more so than prosecutors and judges, were likely to examine “the whole case file” (or nearly the whole file). As found by Emmelman (1998) in interviewing court-appointed defense attorneys, “evidence to them is any information that is lawfully presented to convince judging authorities that a specific contention regarding a criminal matter is true, or in defense at criminal trials, in doubt” (p. 931; emphasis present in original).

When examining the factors that participants clicked on, defendant’s confession was the most often viewed, at 94 % (97 % of both attorney types and 86 % of judges). Given that confession evidence is quite weighty in court (Kassin 2012; Kassin et al. 2010), and has even been found to be more impactful than eyewitness testimony (Kassin and Neumann 1997), the fact that it was the most viewed folder is not surprising. However, confession evidence tended not to be the first folder participants went to, but rather, on average, the seventh (i.e., 6.75; see Appendix 2). The eyewitness identification folder was also viewed by most defense attorneys (95 %) and prosecutors (93 %) but only by 75 % of judges. Pezdek and O’Brien (2014) asked defenders and prosecutors to rate the influence of 17 eyewitness factors in affecting the reliability of the testimony. For the most part, they found few meaningful differences by attorney type, and found most factors to be considered highly influential. Because jurors tend to prefer direct forms of evidence (such as confessions and eyewitnesses) more so than indirect forms (Heller 2006; Wells 1992), the fact that most defense and prosecuting attorneys viewed these folders suggests that their decision-making aligns with the shadow of trial theory. Although DNA evidence, a form of indirect evidence, was also viewed by the majority of participants, it tended to be viewed less often than confession and eyewitness evidence (i.e., by about 89 % of attorneys and 68 % of judges), a finding inconsistent with the results of Lieberman et al. (2008) who found that DNA was viewed as the most accurate and persuasive towards guilt. Finally, Defendant’s Prior Record was viewed first by about one-fifth of the sample (although its average order viewed was seventh; 6.99, Appendix 2). In the Miller et al. dataset, for both prosecutors and defense attorneys, “defendant’s prior record was the second most important unit of information” (p. 83, Rossman et al. 1980). “Most important” was defined by the proportion of respondents examining it; by this criterion, this is precisely what we found as well—“defendant’s prior record” was viewed second most often (Appendix 2). Thus, despite the Miller et al. data suffering from confounded order effects of the folders, our findings converge in many ways.

Do the factors impact plea decision-making among legal actors?

The second question addressed was whether the factors impacted plea decision-making, recognizing that simply examining the factors does not necessarily translate into giving effect to them. With regard to the plea decision, the majority of the sample opted to plead, although, as hypothesized, defense attorneys (82 %) were significantly less likely than prosecutors and judges (~92 %) to do so. These differences in willingness to plead cannot be explained by differences in perceptions of likelihood of conviction, as all three actors were found to have very similar perceptions. Yet this decreased willingness to plead among defenders has been a consistent finding. For example, Pezdek and O’Brien (2014) reported that whereas 74 % of prosecutors in their sample were willing to offer pleas, only 44 % of defenders were willing to recommend pleas. McAllister and Bregman (1986) noted a bias among prosecutors towards plea bargaining whereas defenders were more likely to favor trials. In the present sample, prosecutors demonstrated a similar partiality towards pleas; at one end of the spectrum, only 6 % of prosecutors reported that they would dismiss the case, whereas at the other end, only 3 % reported they would proceed to trial. As stated by a prosecutor interviewed by Alschuler (1968) some 50 years ago, “When we have a weak case for any reason, we’ll reduce to almost anything rather than lose” (p. 59).

In general, the presence of the manipulated pieces of evidence increased the selection of the plea option. However, this pattern really only emerged for the defense attorneys, and thus our hypothesis that the presence of confession, eyewitness, and DNA match evidence would also increase willingness to plead for prosecutors is only partially supported. Plea rates among prosecutors and judges, as mentioned, approached ceiling levels even in the absence of confession, positive eyewitness ID, and DNA match evidence. The one exception to this pattern was that prosecutors’ willingness to offer pleas significantly increased when there was eyewitness evidence, as opposed to when there was not. In line with the shadow of trial model, prosecutors are probably aware that jurors favor direct evidence, such as eyewitness testimony. However, confession evidence, which is also a form of direct evidence and which also sways juries towards conviction (see Kassin et al. 2010), did not show a similar pattern. It is possible that prosecutors believe eyewitness testimony to be a larger risk (more unpredictable) with the jury, thus prompting them to plead the case. In contrast, confession evidence (as well as DNA evidence) would be proffered by law enforcement officers (and forensic scientists) whom prosecutors may view as less risky with juries. Another possible explanation of these findings has to do with the specific details about the eyewitness identification and confession. For example, the live line-up identification took place 1 day after the crime (in which the victim did or did not positively ID the defendant). The defendant was interrogated for 6 hours (and either did or did not confess). Whether the same patterns of findings would emerge, if, for example, the line-up took place 6 weeks after the crime, or the defendant was interrogated for 30 min, are open questions.

The length of the defendant’s criminal history did not influence the plea decision by any of the three legal actors. Thus, whether the defendant had a long or short criminal history did not influence the decision to go to trial or plead, a finding which contrasted with our hypothesis and the original research replicated here (Rossman et al. 1980). With some exceptions, juries typically do not hear about the defendant’s criminal history. However, the presence of a defendant’s criminal history may play into the decision whether to put the defendant on the stand to testify (Eisenberg and Hans 2009), a decision which typically follows the choice to plead versus go to trial. In the present research, participants were presented with defendants who had prior records, or records that were either shorter or longer in length. In contrast, in prior jury decision-making studies, mock jurors were presented with scenarios in which the defendant had a criminal past versus none (see Devine et al. 2001). Thus, the presence–absence of a criminal history record, but not its length, may influence plea decision-making. In addition to the number of prior criminal events (i.e., length), the type and severity of past charges/convictions are also likely to influence the decision to plead or go to trial.

Finally, we did not find demographic or experiential characteristics of legal actors, beyond role itself (i.e., judge, defender, prosecutor) to predict plea versus trial decisions. Similarly, Goodman-Delahunty et al. (2010) did not find attorney years of experience to influence the ability to forecast case outcomes. We also did not find jurisdiction size or caseload to influence the decision, replicating what Nardulli (1979) found more than three decades ago. More recently, Kramer et al. (2007) found that defense attorneys rated having a high caseload as unimportant to their plea decision-making. And in examining real-life plea offers in a large urban county, Kutateladze et al. (2015) also did not find prosecutors’ caseloads (nor their or defendant demographic characteristics) to influence charge or sentence plea offers. Rather, the most robust factors to influence plea charge offers were evidentiary (e.g., recordings of the crime), the defendant’s prior prison record and pre-trial detention status, and whether the plea offer had changed from the initial one made.

In contrast to the findings for the plea decision, legal actor type did not influence plea discounts. Thus, although defenders were less willing to plead than prosecutors and judges, among those who did choose to plead rather than go to trial (which was the majority), discount rates did not differ between the three actor types. The plea discount ranged from 64 to 67 % by legal actor type, a discount that could be considered quite large. For example, a defendant who was convicted at trial and sentenced to 20 years would only receive a plea sentence of about 7 years (20 years x .35). In coding more than 500 district attorney case files across two NY counties, Redlich et al. (2014) calculated plea values by examining initial arrest charges (and the relevant sentence risk) and the final outcome charges. Although the average plea discount was about 56 %, the median plea discount was 75 %. Thus, the plea discounts of about 65 % reported here in response to a hypothetical scenario are not dissimilar to discounts found in actual cases.

A significant interaction effect emerged involving actor type, however. When an eyewitness ID was absent, the differences in plea discount rates by actor type remained nonsignificant (i.e., 65 to 70 %). When an eyewitness ID was present, however, prosecutors’ discounts were significantly smaller (59 %) than both defenders and judges (both 64 %). This latter finding makes sense given that prosecutors have been found to be the most likely to bargain in the shadow of trial (Bushway et al. 2014) and that jurors are known to prefer direct evidence, such as eyewitness evidence (Wells 1992).

As expected, the three manipulated pieces of evidence did significantly influence plea discount rates. In some respects, however, the plea discounts when the evidence was present versus absent were quite small, ranging from 4 to 6 percentage points for confession, eyewitness ID, and DNA match evidence. Moreover, the influence of the presence of an eyewitness ID was qualified by two significant interactions. First, the presence of confession evidence negated the influence of the eyewitness ID. That is, when a confession was present, plea discount rates were similar when an eyewitness was (62 %) and was not present (65 %). Thus, it may be that one piece of evidence, especially evidence that is direct rather than circumstantial (Heller 2006), is sufficient to meet some pre-determined plea discount threshold. However, why this was the case for eyewitness IDs and not for confession or DNA evidence is perplexing. It is possible that the specific details supplied in the hypothetical scenario about the eyewitness ID and the confession drove these findings. Future research should investigate differing circumstances to determine if this is the case.

Finally, although defendant’s criminal history did not influence willingness to plead among the three legal actor types, it did affect plea values. When defendant’s criminal history was shorter rather than longer, plea discounts increased by 7 percentage points. This finding is commensurate with sentencing guidelines, as prior history—its presence and its length—is one of the two main factors jurisdictions consider (Tonry 1987). It is also consistent with prior research. For example, as noted, Kutateladze et al. (2015) found that having prior arrests was associated with plea offers with longer sentences. Bushway and Redlich (2012) also found that number of prior felony arrests and having a juvenile record independently predicted incarceration time for defendants who pled guilty, though they did not influence the estimated probability of conviction at trial (if the defendants had gone to trial).

Conclusions and limitations

The purpose of the present study was to determine the different types of evidence and other factors that practicing criminal justice actors consider and take into effect in the context of plea decision-making. We also aimed to replicate and improve upon a landmark study done in the 1970s by Miller et al. (1978). Via technological advances not available in the 1970s, we were able to increase our sample size nearly six-fold (i.e., from 276 to 1,585), obtain a sample representing all 50 states, include judges, and eliminate order effects by randomizing the order of files. We also demonstrated that this online file-folder method is a viable tool for research on legal actors. However, unlike Miller et al., we did not sit down personally with our sample and see the process of decision-making unfold as they did. Our anonymous recruitment strategies and sampling did not allow us to follow up with non-responders and/or non-completers. Our completion rate of 64 % of practicing legal professionals is quite acceptable for these types of study, however. Further, our sample is nonrepresentative as we relied on sampling strategies that did not randomly select attorneys and judges from the entire US population of these actors (though our sample demographics are very similar to national ones). Findings may or may not generalize to legal actors in other countries which utilize different trial and plea models.

And finally, like all scenario-based research, the present research did not replicate real-world circumstances and pressures that legal actors face during plea decision-making. For example, we did not account for the defendant’s plea wishes, the resources or the culture of the court, or temporal constraints. We also did not measure the risk-taking proclivities of our participants, which will be an important next step. Additionally, although we included 31 potential factors for participants to consider; in the real world, there are many more factors available to decision-makers. Thus, the set of choices supplied to our respondents may have induced them to select factors that may be given less weight, or ignored entirely, in actual plea contexts. To wit, research by Ebbeson and Konecni (1975) demonstrated that the factors judges claim to consider in response to a hypothetical bail case did not align with their actual decisions on bail. Although valuable information was gained about the factors considered and weighed by legal actors, it will be important for researchers to assess plea decision-making in actual cases.

In the present research, we learned that, in contrast to judges, for the most part, defense attorneys and prosecutors considered evidentiary factors to the same degree. We also learned that whereas legal actor role influenced the willingness to advise, offer, or accept a guilty plea, it did not influence the value of the plea. What implications do our findings have for practice and policy? In a system in which only 3 % of convictions are the result of jury trials, information on the factors that judges and attorneys consider when making plea decisions is valuable. Although responding to a hypothetical scenario, the legal actors in the present study also appeared to reject the option of trial. Even in the absence of a confession, an eyewitness, and a DNA match, the majority of attorneys and judges chose to advise/offer, or accept the plea. Further, all three legal actor types perceived the probability of conviction at trial to be around 65 %, but on average were willing to plead more than 85 % of the time. This pattern of results may help to explain the relatively high plea discount rates we found. That is, lower perceived likelihood of conviction at trial would be expected to lead to higher plea discounts to entice defendants to accept the plea offer, resulting in a certain conviction. In large part, we also found the existence of a guilty plea as well as the value of the plea to be driven by evidentiary factors. This suggests that attention should be paid to evidentiary collection processes; in particular, making sure that due process is followed, and that errors such as erroneous eyewitness IDs and false confessions are avoided. Future investigations should continue to work towards determining whether and under what circumstances plea decision-making occurs. Because nearly all convictions in the U.S. are the result of guilty pleas, developing a better understanding of these decisions is critical.

Notes

We note here that other ‘shadow’ models have been put forth, such as Standen’s (1993) “shadow of the guidelines” and Lacasse and Payne (1999)’s “shadow of the judge.” Nonetheless, these models share the same basic underlying premise that decision-making is made on the expectations of trial/sentencing outcomes.

The average amount of time spent on the survey for all completers was 21.94 min. The amount of time spent did not differ significantly across roles (p = .51).

There were four manipulation-check questions, each asking the participant whether each type of manipulated evidence was present or absent. Respondents were given the options of “Yes,” “No,” and “I don’t know.” An answer was considered correct if the participant (1) was in a condition in which the evidence was present and answered “Yes,” (2) was in a condition in which the evidence was not present and answered “No,” or (3) did not choose to view the folder for that particular type of evidence and answered, “I don’t know.”

In the defendant’s prior record, long condition, participants read that the defendant had: (1) Three juvenile contacts, one at age 14 for assault, two at age 16, both for unlawful entry; disposition unknown, (2) Arrest for burglary, age 18; convicted, 1 year of probation; (3) Arrest for robbery, age 19; convicted, 2 years; (4) Arrest for attempted rape, age 21; dismissed; and (5) Arrest for robbery, age 24, convicted, 3 years. In the defendant’s prior record, short condition, participants read that the defendant had: (1) one juvenile contact at age 14 for malicious mischief, disposition unknown, and (2) one arrest at age 18 for disorderly conduct, dismissed. These were the same as used in Miller et al. (1978).

References

Albonetti, C. A. (1990). Race and the probability of pleading guilty. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 6, 315–334. doi:10.1007/BF01065413.

Alschuler, A. (1968). The prosecutor’s role in plea bargaining. University of Chicago Law Review, 36, 50–112.

American Bar Association. (2012). Lawyer demographics. Retrieved from: http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/marketresearch/PublicDocuments/lawyer_demographics_2012_revised.authcheckdam.pdf.

Bibas, S. (2004). Plea bargaining outside the shadow of trial. Harvard Law Review, 117, 2463–2547.

Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2013). Felony defendants in large urban counties, 2009. Retrieved from http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/fdluc09.pdf, on April 15, 2016.

Bushway, S. D., & Redlich, A. D. (2012). Is plea bargaining in the “shadow of trial” a mirage? Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 28, 437–454. doi:10.1007/s10940-011-9147-5.

Bushway, S. D., Redlich, A. D., & Norris, R. J. (2014). An explicit test of plea bargaining in the “shadow of the trial”. Criminology, 52, 723–754.

Devine, D. J., Clayton, L. D., Dunford, B. D., Seying, R., & Pryce, J. (2001). Jury decision-making: 45 years of empirical research. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 7, 622–727. doi:10.1037//1076-8971.7.3.622.

Devine, D. J., Buddenbaum, J., Houp, S., Studebaker, N., & Stolle, D. P. (2009). Strength of the evidence, extraevidentiary influence, and the liberation hypothesis: data from the field. Law and Human Behavior, 33, 136–148. doi:10.1007/s10979-008-9144-x.

Ebbeson, E. B., & Konecni, V. J. (1975). Decision making and information integration in the courts: the setting of bail. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 805–811.

Edelman, L. B., Leachman, G., & McAdam, D. (2010). On law, organizations, and social movements. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 6, 653–685.

Edkins, V. A. (2011). Defense attorney plea recommendations and client race: does zealous representation apply equally to all? Law and Human Behavior, 35, 413–425. doi:10.1007/s10979-010-9254-0.

Eisenberg, T., & Hans, V. (2009). Taking a stand on taking the stand: the effect of a prior criminal record on the decision to testify and on trial outcomes. Cornell Law Review, 94, 1353–1390.

Elder, H. W. (1989). Trials and settlements in the criminal courts: an empirical analysis of dispositions and sentencing. The Journal of Legal Studies, 18, 191–208.

Emmelman, D. S. (1998). Gauging the strength of evidence prior to plea bargaining: the interpretive procedures of court-appointed defense attorneys. Law and Social Inquiry, 22, 927–955. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.1997.tb01093.x.

Frenzel, E. D., & Ball, J. D. (2007). Effects of individual characteristics on plea negotiations under sentencing guidelines. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 5, 59–82. doi:10.1300/J222v05n04_03.

Garvey, S. P., Hannaford-Agor, P., Hans, V. P., Mott, N. L., Munsterman, G. T., & Wells, M. T. (2004). Juror first votes in criminal trials. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 1, 371–399.

Goodman-Delahunty, J., Granhag, P. A., Hartwig, M., & Loftus, E. F. (2010). Insightful or wishful: Lawyers’ ability to predict case outcomes. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 16, 133–157.

Greene, E. (1988). Judge’s instruction on eyewitness testimony: evaluation and revision. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 18, 252–276. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1988.tb00016.x.

Heller, K. J. (2006). The cognitive psychology of circumstantial evidence. Michigan Law Review, 105, 241–305.

Heumann, M. (1981). Plea bargaining: The experiences of prosecutors, judges, and defense attorneys. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Johnson, B. D. (2005). Contextual disparities in guidelines departures: courtroom social contexts, guidelines compliance, and extralegal disparities in criminal sentencing. Criminology, 43, 761–796.

Kalven, H., & Zeisel, H. (1966). The American jury. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kassin, S. M. (2012). Why confessions trump innocence. American Psychologist, 67, 431–445. doi:10.1037/a002812.

Kassin, S. M., & Neumann, K. (1997). On the power of confession evidence: an experimental test of the fundamental difference hypothesis. Law and Human Behavior, 21, 469–484. doi:10.1023/A:1024871622490.

Kassin, S. M., Drizin, S., Grisso, T., Gudjonsson, G., Leo, R. A., & Redlich, A. D. (2010). Police-induced confessions: risk factors and recommendations. Law and Human Behavior, 34, 3–38. doi:10.1007/s10979-009-9188-6.

Kellough, G., & Wortley, S. (2002). Remand for plea: bail decisions and plea bargaining as commensurate decisions. British Journal of Criminology, 42, 186–210. doi:10.1093/bjc/42.1.186.

Kerlinger, F. N., & Lee, H. B. (2000). Foundations of behavioral research (4th ed.). Belmont: Cengage Learning.

Koehler, J. J. (2001). When are people persuaded by DNA match statistics? Law and Human Behavior, 25, 493–513. doi:10.1023/A:1012892815916.

Kramer, G. M., Wolbransky, M., & Heilbrun, K. (2007). Plea bargaining recommendations by criminal defense attorneys: evidence strength, potential sentence, and defendant preference. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 25, 573–585. doi:10.1002/bsl.759.

Kutateladze, B. L., Lawson, V. Z., & Adiloro, N. R. (2015). Does evidence really matter? An exploratory analysis of the role of evidence in plea bargaining in felony drug cases. Law and Human Behavior. doi:10.1037/lhb0000142.

Lacasse, C., & Payne, A. A. (1999). Federal sentencing guidelines and mandatory minimum sentences: do defendants bargain in the shadow of the judge? Journal of Law and Economics, 42, 245–270.

LaFree, G. D. (1985). Adversarial and non-adversarial justice: a comparison of guilty pleas and trials. Criminology, 23, 289–312. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1985.tb00338.x.

Landes, W. (1971). An economic analysis of the courts. Journal of Labor Economics, 14(1), 61–107.

Lieberman, J. D., Carrell, C. A., Miethe, T. D., & Krauss, D. A. (2008). Gold versus platinum. Do jurors recognize the superiority and limitations of DNA evidence compared to other types of forensic evidence? Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 14, 27–62.

Lynch, T. (2003). The case against plea bargaining. Regulation, 24–27.

McAllister, H. A., & Bregman, N. J. (1986). Plea bargaining by prosecutors and defense attorneys: a decision theory approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 686–690. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.71.4.686.

McCormick, C. T. (1983). Handbook of the law of evidence (2nd ed.). St Paul: West.

McDonald, W. F. (1979). The prosecutor. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

McDonald, W. F., & Cramer, J. A. (1980). Plea bargaining. Lexington: Lexington Books.

Miller, H. S., McDonald, W. F., & Cramer, J. A. (1978). Plea bargaining in the United States. Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice.

Mitchell, O. (2005). A meta-analysis of race and sentencing research: explaining the inconsistencies. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 21, 439–466. doi:10.1007/s10940-005-7362-7.

Mnookin, R. H., & Kornhauser, L. (1979). Bargaining in the shadow of the law: the case of divorce. Yale Law Journal, 88, 950–997.

Morrill, C., & Rudes, D. S. (2010). Conflict resolution in organizations. Annual Review of Law and Social Sciences, 6, 627–651.

Nagel, S. S., & Neef, M. G. (1979). Decision theory and the legal process. Lexington: Lexington.

Nardulli, P. F. (1979). The caseload controversy and the study of criminal courts. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 70, 89–101.

National Academy of Sciences. (2009). Strengthening forensic science in the United States: a path forward. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

Niedermeier, K. E., Kerr, N. L., & Messe, L. A. (1999). Jurors’ use of naked statistical evidence: exploring bases and implications of the Wells Effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 533–542.

Oppel, R. A. (2011). Sentencing shift gives new leverage to prosecutors. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/26/us/tough-sentences-help-prosecutors-push-for-plea-bargains.html?pagewanted=all&_r=2&

People v. Falsetta 986 P. 2d 182 (1999).

Pezdek, K., & O’Brien, M. (2014). Plea bargaining and appraisals of eyewitness evidence by prosecutors and defense attorneys. Psychology Crime and Law, 20, 222–241. doi:10.1080/1068316X.2013.770855.

Redlich, A. D., Bushway, S. D., Norris, R., & Yan, S. (2014). Bargaining in the shadow of trial? Examining the reach of evidence outside the jury box. Award # 2009-IJ-CX-0035. Final report submitted to the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Washington, DC.

Rossman, H. H., McDonald, W. F., & Cramer, J. A. (1980). Some patterns and determinants of plea-bargaining decisions: A simulation and quasi-experiment. In W. F. McDonald & J. A. Cramer (Eds.), Plea bargaining (pp. 77–114). Lexington: Lexington Books.

Savitsky, J. C., & Lindblom, W. D. (1986). The impact of the guilty but mentally ill verdict on juror decisions: an empirical analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 16, 686–701. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1986.tb01753.x.

Schklar, J., & Diamond, S. S. (1999). Juror reactions to DNA evidence: errors and expectancies. Law and Human Behavior, 23, 159–184. doi:10.1023/A:1022368801333.

Smith, D. A. (1986). The plea bargain controversy. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 77, 949–968.

Spohn, C. (2000). Thirty years of sentencing reform: The quest for a racially neutral sentencing process. National Institute of Justice: Criminal Justice 2000. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

Standen, J. (1993). Plea bargaining in the shadow of the guidelines. California Law Review, 81, 1471–1538.

Stuntz, W. J. (2004). Plea bargaining and criminal law’s disappearing shadow. Harvard Law Review, 117, 2548–2569.

Thompson, W. C. (2006). Tarnish on the gold standard: recent problems in forensic DNA testing. The Champion, 30(1),10-16.

Tonry, M. (1987). Sentencing guidelines and their effects. In A. Von Hirsch, M. Tonry, & K. Knapp (Eds.), The sentencing commission and its guidelines. New York: UPNE.

Ulmer, J. T., & Johnson, B. D. (2004). Sentencing in context: a multilevel analysis. Criminology, 42, 137–178.

Wells, G. L. (1992). Naked statistical evidence of liability: is subjective probability enough? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 739–752. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.62.5.739.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

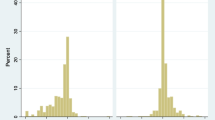

Screenshot of Case File Folders

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Redlich, A.D., Bushway, S.D. & Norris, R.J. Plea decision-making by attorneys and judges. J Exp Criminol 12, 537–561 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-016-9264-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-016-9264-0