Abstract

Objectives

We completed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the available empirical literature assessing the influence of accusatorial and information-gathering methods of interrogation in eliciting true and false confessions.

Methods

We conducted two separate meta-analyses. The first meta-analysis focused on observational field studies that assessed the association between certain interrogation methods and elicitation of a confession statement. The second meta-analysis focused on experimental, laboratory-based studies in which ground truth was known (i.e., a confession is factually true or false). We located 5 field studies and 12 experimental studies eligible for the meta-analyses. We coded outcomes from both study types and report mean effect sizes with 95 % confidence intervals. A random effects model was used for analysis of effect sizes. Moderator analyses were conducted when appropriate.

Results

Field studies revealed that both information-gathering and accusatorial approaches were more likely to elicit a confession when compared with direct questioning methods. However, experimental studies revealed that the information-gathering approach preserved, and in some cases increased, the likelihood of true confessions, while simultaneously reducing the likelihood of false confessions. In contrast, the accusatorial approach increased both true and false confessions when compared with a direct questioning method.

Conclusions

The available data support the effectiveness of an information-gathering style of interviewing suspects. Caution is warranted, however, due to the small number of independent samples available for the analysis of both field and experimental studies. Additional research, including the use of quasi-experimental field studies, appears warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bright lights have been shone on both military and police interrogation methods in recent years. The effectiveness of military or intelligence interrogations has come under intense scrutiny as a result of the use of “enhanced” interrogation methods in Iraq and Afghanistan and heated debate over the use and efficacy of torture for eliciting information (see Evans et al. 2010; Hartwig et al. 2014; Redlich 2007). At the same time, police interview and interrogation methods in the criminal justice arena are being called into question because of the incidence of false confessions leading to wrongful conviction (see Kassin et al. 2010; Redlich and Meissner 2009).

The elicitation of false confessions is an international problem that has been documented in almost every continent (Kassin et al. 2010; Lassiter and Meissner 2010). Two general factors have been linked to the incidence of false confessions: personal (psychological) vulnerabilities of the individual and the use of accusatorial (psychologically-based) interrogative methods. While accusatorial methods are commonly trained in countries such as the United States, Canada, and many Asian nations (Costanzo and Redlich 2010; Leo 2008; Ma 2007; Smith et al. 2009), some European countries have, under the influence of article 6 para. 1 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR), banned using closed-ended or confirmatory questions and deception (e.g., by presenting false evidence) in the interrogation of suspects. Countries such as the United Kingdom, Norway, New Zealand, and Australia, have amended their interrogation practices to employ information-gathering methods of interrogation (Bull and Soukara 2010). Systematic research examining these two approaches to interviewing and interrogation has been conducted over the past decade, with studies generally demonstrating that accusatorial methods increase the likelihood of false confession, while information-gathering methods protect the innocent yet preserve interrogators’ ability to elicit confessions from guilty persons (see Meissner et al. 2010b).

The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate the diagnostic value of information-gathering and accusatory (or guilt-presumptive) interrogative methods for persons suspected of committing crimes. Interviewing and interrogation methods can be considered “diagnostic” when they produce a higher ratio of true to false confessions and/or when they yield the ability to discriminate accurate from inaccurate information (in the context of deception detection). When assessing the effectiveness of questioning techniques on investigative outcomes, it is important to consider the accuracy of the outcome (i.e., not simply use “confession” as the outcome). It is equally important to assess efficacy when suspects are both guilty and innocent, as these two contexts may produce different levels of effectiveness. As such, field studies and experimental (laboratory) studies offer different perspectives regarding the effectiveness of certain interrogative methods depending upon these conditions. Specifically, field studies permit the opportunity to examine the production of confessions or admissions as a function of method under real-world conditions; however, the effectiveness of such methods cannot be conditioned on “ground truth”. Only laboratory studies allow scientists to randomly assign participants to relevant conditions (e.g., guilt or innocence, accusatorial or information-gathering, etc.) and assess the causal mechanisms underlying various methods, though such studies may be limited in the degree of ecological validity and experimental realism (see Meissner et al. 2010b). The current systematic review explores information-gathering and accusatorial methods as assessed within both types of studies.

Generally speaking, information-gathering and accusatorial interrogation methods can be distinguished along five dimensions. As displayed in Table 1, information-gathering methods seek to establish rapport within the interview, and use direct, positive confrontation of the suspect to elicit confessions or other self-incriminating statements. In contrast, accusatorial methods seek to establish control of the suspect and use psychological manipulation to achieve confession. As such, these two methods result in distinct questioning approaches, with information-gathering methods relying upon open-ended, exploratory approaches and accusatorial methods employing closed-ended, confirmatory approaches. Additionally, the two methods differ in their primary intended outcome. Whereas the information-gathering method places a premium on obtaining information, the accusatorial approach aims to obtain confessions. Finally, the two methods can be contrasted based upon the model of deception detection that they invoke: information-gathering methods yield cognitive cues (see below) to deception, while accusatorial methods yield anxiety-based cues to deception. These two methods are explored in greater detail below.

The accusatorial method (as defined here) is typified by certain training approaches within the United States (cf. Inbau et al. 2001) and by field studies and surveys of police practice in the United States (Kassin et al. 2007; Leo 2008). It is generally contradictory to the information-gathering style in that it is confrontational and guilt-presumptive. According to an accusatorial method, police questioning of suspects consist of two phases. In the first phase, the investigator generally conducts a non-accusatorial interview to determine whether the person of interest is indeed the “suspect” and should therefore be formally interrogated (e.g., the “Behavioral Analysis Interview”, or BAI, proposed by Inbau et al. 2001). A major facet of this determination of guilt is a reliance on non-verbal behavioral cues and analyses of linguistic and paralinguistic styles that are believed to indicate deception, but which consistently have been found by scientific methods to be unreliable (see DePaulo et al. 2003; Sporer and Schwandt 2006, 2007).

According to an accusatorial approach, it is only following a determination of “guilt” on the part of the investigator that a formal interrogation of the suspect—the second phase—begins. The investigator is then recommended to employ a variety of psychologically manipulative tactics that are designed to elicit compliance from a suspect in the form of a confession to the crime. As summarized by Kassin and Gudjonsson (2004), interrogations generally involve three components: (1) custody and isolation, in which the suspect is detained in a small room and left to experience the anxiety, insecurity, and uncertainty associated with police interrogation; (2) confrontation, in which the suspect is presumed guilty and told (sometimes falsely) about the evidence against him/her, is warned of the consequences associated with his/her guilt, and is prevented from denying his/her involvement in the crime; and finally (3) minimization, in which a now sympathetic interrogator attempts to gain the suspect’s trust, offers the suspect face-saving excuses or justifications for the crime, and implies more lenient consequences should the suspect provide a confession. The strong belief in “guilt” on the part of interrogators has been shown to lead to the use of longer interrogations that involve more psychologically manipulative tactics—ultimately leading to the elicitation of both true and false confessions that confirm the beliefs of the interrogator (see Kassin et al. 2003; Meissner and Kassin 2002, 2004; Narchet et al. 2011). The psychological manipulation of consequences in this context, and the associated manipulation of perceived culpability on the part of the suspect, have been shown to directly influence the incidence of false confessions (see Horgan et al. 2012).

In contrast, the information-gathering method of interviewing is typified by practices in England and Wales where, because of a spate of high-profile false confessions, the Police and Criminal Evidence (PACE) Act of 1984 (Bull and Soukara 2010; Home Office 2003) was enacted. This act allowed judges greater discretion in prohibiting the admission of confession testimony that was acquired via the use of certain coercive interrogation approaches and mandated the recording of custodial interrogations. In 1992, as a result of a national review of investigative interviewing initiated by the Association of Chief Police Officers and the relevant government ministry, the PEACE model (Planning and Preparation, Engage and Explain, Obtain an Account, Closure, Evaluation; see Bull and Soukara 2010; Milne and Bull 1999) was introduced. This model focuses on developing rapport, explaining the allegation and the seriousness of the offense, emphasizing the importance of honesty and truth gathering, and requesting the suspect’s version of events. Suspects are permitted to explain the situation without interruption and questioners are encouraged to actively listen. Only after suspects have been given a full opportunity to provide information are they questioned and presented with any inconsistencies/contradictions (e.g., information known to the interviewer but not yet revealed to the suspect). As mentioned, this interview method has the goal of “fact finding” rather than that of obtaining a confession (with an emphasis on the use of open-ended questions), and investigators are expressly prohibited from deceiving suspects (Milne and Bull 1999; Mortimer and Shepherd 1999; Schollum 2005).

The PEACE model is similar to components of the Cognitive Interview (CI; Fisher and Geiselman 1992; Memon et al. 2010). The CI was derived from basic memory research and involves a series of mnemonic elicitation techniques that have been shown to improve the recall of information from memory. One of the principal techniques is context reinstatement (i.e., attempts to reinstate emotions, perceptions, and sequences of the event to-be-remembered). Another technique is to vary the order in which events are recounted. For example, Vrij et al. (2008) assessed whether asking liars and truth-tellers to recall an event in reverse order (which, in theory, should be more difficult for liars than truth-tellers) would improve interviewers’ ability to accurately detect deception. Although the effectiveness of the CI has been researched extensively (see Memon et al. 2010), the majority of this research (but importantly, not all) has focused on witnesses and victims’ reports of events, not suspects (see Fisher and Perez 2007).

The scientific study of investigative interviewing has proliferated in the past two decades. The PEACE model and some of its individual components (e.g., strategic disclosure of evidence, use of open-ended questions) have been studied in the field and in the laboratory (Bull and Soukara 2010; Meissner et al. 2010b). Similarly, numerous experiments have been conducted on general (e.g., Russano et al. 2005a) and more specific accusatorial methods (e.g., presenting false evidence; Redlich and Goodman 2003).

The objectives of the current review were to systematically and comprehensively review published and non-published, experimental and observational studies on the effectiveness of interrogation methods. We focus on suspects as our population, interview style (information-gathering, accusatorial) as the intervention, and the elicitation of true and false confessions as the primary measure of efficacy. Our guiding question was whether information-gathering or accusatorial methods are more diagnostic in the accuracy of self-incriminating information that is produced when employed on guilty and innocent suspects. We note here that only experimental studies offer a sound perspective on the diagnostic value of an interrogative method—field studies cannot distinguish the “ground truth” that is necessary to assess the accuracy of a confession or the culpability of a suspect. While we review studies conducted in both contexts, the distinction between these types of studies and the ultimate conclusions that might be drawn from them is critically dependent upon this distinction. We also note that because a dichotomous, yes/no confession variable (as opposed to amount of information) has been the most-often used outcome in the studies we reviewed (and ultimately deemed eligible), our focal outcome measure by necessity is also confession (true and false). A novel experimental paradigm focusing on the elicitation of guilty knowledge from non-cooperative individuals has only recently been introduced to the empirical literature (see Evans et al. 2013).

Methods

We completed two separate meta-analyses of observational and quasi-experimental studies conducted in a field setting, and experimental studies conducted in a laboratory setting, respectively. Our search criteria were broad and intended to elicit a large sample of possible studies for inclusion in the analyses. Studies were selected based upon pre-specified inclusion/exclusion criteria, and relevant studies were coded on key variables by multiple researchers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Field studies

To be eligible for inclusion in the field study meta-analysis, published and unpublished studies must have met the following requirements:

-

Intervention: Systematic studies that examined interview and interrogation techniques used in actual law enforcement/military settings (i.e., the “field”) were included here. Studies could have involved quasi-experimental designs in which interrogators were assigned to use certain interrogative approaches. We also permitted the inclusion of studies that involved systematic observation of interviews/interrogations (live or on video) or the analysis of archival records (e.g., police reports, transcribed interviews) that provide sufficient detail regarding the interrogation methods employed in a given case. The study must have coded or quantified the use of at least one interview or interrogation technique. These techniques were then categorized (by reliable consensus) into information-gathering, accusatorial, or direct questioning approaches.

-

Outcomes: Eligible studies must have reported the analysis of confessions (partial, full outcome). In addition, sufficient quantitative data to calculate effect sizes must have been present, specifically including the relationship between the use of certain interview/interrogation methods and elicitation of a confession.

-

Population/Samples: The population of interest is suspects (of any age, nationality, or status) who are accused of committing a criminal act. Studies that assessed the interviewing of victims and witnesses were not included here, as the motivations and information to-be-gained (and thus the potential effectiveness of methods) likely differ. Thus, to be eligible, studies must have included “suspected perpetrators” or “suspected transgressors.”

Laboratory studies

To be eligible for inclusion in the laboratory study meta-analysis, published and unpublished studies must have met the following requirements:

-

Intervention: The intervention of interest was interviewing approach (information-gathering, accusatorial, and/or “control” or direct questioning methods). To be included here, the study must have involved the experimental manipulation of information-gathering and/or accusatorial methods with one another or with a control (direct questioning) interview method.

-

Outcomes: Outcome variables included the proportion of true and false confessions when the suspects were guilty and innocent. Eligible studies must have reported outcomes for “guilty” participants, “innocent” participants, either, or both (for example, several studies only include situations in which all participants are innocent). Further, at least one outcome measure (with sufficient quantitative data to calculate an effect size) must have been present.

-

Population/Samples: The population of interest involved “mock” suspects (of any age, nationality, or status) who are accused of committing mock crimes/transgressions or withholding important information. The interviewing of victims and witnesses was not included here, as the motivations and information to-be-gained (and thus the potential effectiveness of methods) likely differ. Thus, to be eligible, studies must have included “suspected perpetrators” or “suspected transgressors.”

Search strategy

Using a multi-step process, we searched for published and unpublished manuscripts describing experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational studies on information-gathering and accusatorial approaches to interviewing and interrogation (through September, 2013). We searched the following databases:

-

1.

Criminal Justice Periodical Index

-

2.

Criminal Justice Abstracts

-

3.

National Criminal Justice Reference Services (NCJRS) Abstracts

-

4.

PsychInfo [which includes PsychARTICLES]

-

5.

MEDLINE

-

6.

Sociological Abstracts

-

7.

Social Science Abstracts (SocialSciAbs)

-

8.

Social Science Citation Index

-

9.

Dissertation & Theses Abstracts

-

10.

Google, including Google Scholar—Advanced

-

11.

Australian Criminology Database (CINCH)

-

12.

Centrex (Central Police Training and Development Authority)—UK National Police Library

-

13.

Scopus

-

14.

Web of Knowledge

-

15.

Publisher databases, such as Springer and Wiley

-

16.

California POST Library

We used the following keywords, as well as combined keywords to produce more targeted searches, such as “interview and suspect,” and “confession and interrogation.”

-

1.

Interrogation(ory)

-

2.

Information (gathering)

-

3.

Inquisitorial

-

4.

Interview(ing)

-

5.

Suspect

-

6.

Confession

-

7.

Cognitive Interview

-

8.

Conversation Management

-

9.

Ethical interviewing

-

10.

Disclosure

-

11.

Strategic evidence

-

12.

Accusatory(ion)

-

13.

Deception detection

-

14.

PEACE model of interviewing

-

15.

PACE (Police Criminal and Evidence Act)

-

16.

Adversary(ial)

-

17.

Miranda

-

18.

Coercion (psychological coercion)

-

19.

Entrapment

We also reviewed the reference sections of notable comprehensive reviews on interrogation (Bull et al. 2009; Fein 2006; Gudjonsson 2003; Justice et al. 2009; Kassin et al. 2010; Lassiter and Meissner 2010; Schollum 2005; Williamson 2006). Finally, researchers who have published in this area were contacted by the reviewers with a request to provide any unpublished or ‘in press’ studies that might be included in the review. Multiple follow-up requests were sent to those who failed to respond initially. A request for studies was also placed on a popular listserv for interviewing and interrogation researchers. Officials from government agencies were contacted, including program officers that manage research programs relevant to the current review. Requests were also sent to a self-formed group called FAIR (Federal Alliance for Interdisciplinary Research), which includes personnel from the Central Intelligence Agency, United States Secret Service, National Institute of Justice, Office of Science and Technology Policy, among others, and to PASILE, a group of national security psychologists from the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Coding of studies

All studies that passed an initial screening for eligibility (e.g., the study did not focus on cooperative witnesses) went through two additional rounds of coding. The first round involved an eligibility survey that determined ultimate eligibility for the present review. The second round of coding focused on details of the studies that might be used subsequently for descriptive purposes and moderator analysis of effect sizes.

Studies that were screened in based upon abstract information were subsequently reviewed for eligibility. In addition to documenting basic information about the publication, dates, and authors, we coded whether the study met all of the eligibility criteria to be included in the meta-analytic review (discussed previously). For studies that were deemed eligible for the field study meta-analysis, we coded the following information:

-

a.

Reference information (e.g., title, authors, publication, etc.);

-

b.

Purpose of the study;

-

c.

Methodological factors (e.g., method of coding, type of observation, etc.);

-

d.

Characteristics of the suspect, crime, interrogation, and interrogator; and

-

e.

Relevant outcomes and statistics provided.

For studies that were deemed eligible for the experimental laboratory study meta-analysis, we coded the following information:

-

a.

Reference information (e.g., title, authors, publication, etc.);

-

b.

Method/approach of interrogation;

-

c.

Manipulations (e.g., guilt/innocence, training, suspect/interviewer characteristics, etc.);

-

d.

Methodological factors (e.g., random assignment, suspect/interviewer status, etc.);

-

e.

Sample sizes by condition; and

-

f.

Relevant outcomes and statistics provided.

Two trained researchers independently coded all studies for initial screening. Upon determination of eligibility, these same researchers coded all eligible studies based upon key variables. Uncertainty and disagreement between the two coders were resolved through discussion and consultation with the first author, who ultimately reconciled all disagreements. When necessary, confidential, government documents were coded by authors Brandon and Bhatt, who maintained the appropriate security clearances.

Selected studies

Using the broad search strategy specified above, we initially located more than 2,000 studies in the 16 databases using the 22 distinct keywords. We first determined relevance by reading titles and abstracts. For example, titles that clearly referred to victim/witness accounts were excluded. Additionally, when abstracts revealed that systematic experimental, quasi-experimental, or observational methods were not utilized, these articles were excluded. When researchers were uncertain regarding key aspects of the study, articles were accessed and reviewed more completely. Trained coders were responsible for initial determinations of relevance, with the first two authors making all final decisions regarding inclusion/exclusion. Based upon the results of the screening process, 34 field studies and 22 laboratory studies were deemed eligible for complete coding.

Field studies

A total of 34 potentially eligible field studies were located; of these, only 5 studies were ultimately deemed eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Eligible studies are described in more detail below. The primary reason that field studies were determined to be ineligible involved the failure of the study to assess (or report on) associations between interview/interrogation approach and confession outcomes. Approximately half the studies were conducted in either the United Kingdom or Australia, and the other half in North America (United States and Canada). Excluded studies from the United Kingdom and Australia were: Baldwin (1993, see also, Baldwin 1992), Bull and Soukara (2010), Dixon (2007), Griffiths (2008), McConville and Baldwin (1982), McGurk et al. (1993), Medford et al. (2003), Moston et al. (1992), Pearse (2009), Pearse and Gudjonsson (1999), Softley (1980), Stephenson and Moston (1994), Walsh and Milne (2008), and Willis et al. (1988). Excluded studies from the United States and Canada included: Cassell and Hyman (1996), DesLauriers-Varin et al. (2011), Faller et al. (2001), Feld (2006, 2013), Lippert et al. (2010), Medalie et al. (1968), Neubauer (1974), New Haven Study (1967), Reiss and Black (1967), Seeburger and Wettick (1967), Vera Institute Study (1967), and Witt (1973).

Publication dates for the initial sample of field studies ranged from 1967 to 2013. A primary reason for several early studies in the United States was to examine the impact of the Miranda ruling (decided in 1966) on confession rates. Many of these early studies, however, were non-systematic and failed to examine key aspects of the interrogation approach (the focus of the current meta-analysis) or to include the necessary statistics. In reviewing the initial sample of field studies, we found that many failed to report basic descriptive information about the suspects or the interrogations. Of the 34 studies we coded, approximately half did not report gender or age of the suspect. Approximately one-third of the studies reported race/ethnicity. Additionally, characteristics of the detectives were frequently omitted, with the exception of years of experience or amount of training (particularly when the focus of the study concerned the influence of training). Most studies also failed to report the crime type/severity across suspects and only 8 studies attempted to code the strength of the evidence against the suspect (a key factor identified in producing confessions; see Gudjonsson 2003).

Our coding of the available literature demonstrated other factors that researchers associated with a confession outcome. Table 2 provides a listing of the various factors and the percentage of studies that examined each. Factors that were frequently reported included characteristics of the suspect and/or interrogator, the crime type and/or severity, and the time and location of the interviews and interrogations. In addition, case (14 %) and sentencing (6 %) outcomes were sometimes reported.

We note here that all of the field studies obtained from the literature involved systematic observation methods in which researchers coded the frequency of certain predictor and outcome variables via live observation (14.8 %), audio-video (44.4 %), verbatim transcripts (7.4 %), and/or other archival (court) records associated with the interrogation (40.7 %). No studies involving an experimental or quasi-experimental analysis of interrogation methods in a field setting were located. We return to the omission of such a research literature in our discussion.

Laboratory studies

Of the 22 potentially eligible experimental studies located, 12 were deemed eligible to be included in the meta-analysis. The eligible studies are described below. The remaining ten studies were deemed ineligible because they did not contrast interviewing/interrogation approaches, but rather examined the influence of only one type (most often, this involved accusatorial methods), failed to include an appropriate control (direct questioning) condition, or examined other factors that might influence true or false confession rates (such as anxiety, suggestibility, etc.). The nine excluded studies were: Abboud et al. (2002), Beune et al. (2009; see also Beune 2009), Forrest et al. (2006), Horgan et al. (2012), Horselenberg et al. (2003), Kebbell and Daniels (2006), Kebbell et al. (2006), Klaver et al. (2008), Nash and Wade (2009), and van Bergen et al. (2008). Three of these studies were conducted in the United States, two in Australia, three in the Netherlands, and one each in the United Kingdom and Canada. All studies included college students as subjects.

Characteristics of eligible studies

Field studies

A total of five empirical research articles were included in the meta-analysis representing data recorded from 608 interrogation sessions. Eight independent samples (k) across three effect size comparisons (accusatorial, information-gathering, and combined interrogative methods) were evaluated. Three of the studies were conducted in the United Kingdom, one in Canada, and one in the United States.

Based upon a priori characteristics of accusatorial and information-gathering approaches (see Table 1), the lead reviewers coded the interrogation approaches that were quantified in each of the 5 studies for whether the approach was consistent with accusatorial methods or information-gathering methods. A third category encompassed direct questioning methods that were common to both approaches. Coders demonstrated high agreement rates (>90 %), and all discrepancies were resolved via discussion. Brief descriptions of the five eligible field studies are provided below.

King and Snook (2009)

The authors coded 44 videotaped interrogations from Atlantic Canada. They used the Reid Technique (an accusatorial approach) and 23 (of 25) tactics noted by Leo (1996) as a guiding framework, as well as coding pre-defined coercive tactics. Interrogations had been conducted over a 10-year span. Most crimes were serious crimes against persons. Overall, 50 % of the suspects offered a full or partial confession.

Leo (1996)

One of the largest field studies, Leo observed and coded 122 live interrogations and 60 videotaped interrogations (across three separate police stations in Northern California). Leo described the typical suspect in his sample as a “young, lower or working class, African-American male” (p. 273). The majority of crimes were serious (homicide, robbery, and assault), though about 20 % involved theft, burglary, or ‘other.’ Leo coded the number of interrogation tactics used, as well as the type of approach. He developed a list of 25 tactics, which he examined in relation to several other variables. These tactics included, for example, ‘appeal to suspect’s conscience,’ ‘identify contradictions,’ and ‘confront suspect with false evidence.’ Approximately 64 % offered some admission of guilt.

Pearse et al. (1998)

A primary intent of this study was to examine differences in psychological vulnerabilities between suspects who did versus did not confess during police questioning. The authors, however, also coded three interview tactics: introducing evidence, emphasizing the nature of the offense, and challenging a suspect by saying he or she was lying. Interviews of 160 suspects were conducted from December 1991 to April 1992 at two London, UK, police stations. Interviews were audiotaped and then transcribed. The interview tactics were then coded using the transcripts. Confessions were made in 58 % of the cases (50 % for vulnerable and 60 % for non-vulnerable, which was not a significant difference).

Soukara et al. (2009)

The authors obtained 80 audiotaped interviews of suspects and coded the presence/absence of 17 different interview tactics. The interviews were conducted in the UK by a “relatively large police force” (p. 497) and 22 distinct crimes were represented. Thirty-one of 80 suspects confessed during the interview (see also Bull and Soukara 2010).

Walsh and Bull (2010)

In this study, Walsh and Bull focused on social security benefit fraud. Using 142 British suspect interviews conducted between 2004 and 2007, the authors coded whether questioners were at, above, or below PEACE (i.e., information-gathering approach) standards. They coded the interviews for 19 specific skills/tactics, such as “displays active listening skills,” “uses pauses and silences,” and “conversation management skills.” The authors also examined associations between PEACE interviewing skills and confession outcomes (e.g., denials, partial admissions, detailed confessions).

Laboratory studies

A total of 30 independent sample (k) contrasts described in 12 experimental research manuscripts were included in the meta-analysis, representing the responses of 1,814 participants. The 12 eligible, experimental studies varied by publication status, interview-style contrast, and confession-type outcome. All but one of the studies was conducted in the United States (i.e., Hill et al. 2008 in Aberdeen, UK). Nine have been published in peer-reviewed journals (from 1996 to 2011) and three are currently unpublished.

Only one study contrasted all three interviewing styles (accusatory vs. information-gathering vs. direct questioning; Meissner et al. 2011), and only one additional study examined the information-gathering approach (Narchet et al. 2011). The remaining 10 studies contrasted a control (direct questioning) method with the accusatorial method. Six studies examined the impact of interviewing method on both true and false confessions, while the remaining six focused only on false confessions. We did not find an eligible, experimental study that examined only true confessions.

Eleven of the 12 studies used variations of either the Kassin and Kiechel (1996) or the Russano et al. (2005a) paradigm. The Kassin and Kiechel paradigm is one in which all participants are ‘innocent’ of the mock crime of crashing the computer. The Russano et al. paradigm includes participants randomly assigned to an innocent or guilty condition of a known, intentional act (i.e., cheating). (See Meissner et al. 2010b, for more complete descriptions of these two paradigms.) Eleven of the studies used undergraduate students as participants, with two studies including students from other minor age groups (i.e., Billings et al. 2007; Redlich and Goodman 2003). Brief descriptions of the 12 eligible laboratory studies are provided below.

Billings et al. (2007)

Billings and colleagues examined how reinforcement (i.e., receiving verbal reinforcement that the given answer was correct/desired) influenced children’s willingness to falsely confess or express guilty knowledge. Children from kindergarten through 3rd grade watched the staged theft of a toy in their classrooms. Then, children were randomly assigned to one of two interview conditions: control or reinforcement. In the control condition, children were asked straightforward suggestive questions about the theft. In the reinforcement condition, children were asked the same questions but also received reinforcement for the “right” answers. Children in both conditions were also asked if they themselves took the toy (which would be false confessions). For our purposes, the reinforcement condition was accusatory (thus, accusatory vs. control).

Blair (2007)

This study used the basic Kassin and Kiechel (1996) paradigm, though with some variations. Specifically, the author instructed participants not to touch the Control, ALT, and Delete keys (simultaneously) or the computer would crash (rather than just the ALT key). Undergraduate students were randomly assigned to the presentation of false evidence (i.e., being told that the computer server documented the keys hit and that indeed CTRL, ALT, and DEL were hit), and to the presentation of a minimization-maximization approach. The minimization-maximization tactic consisted of the following statement: “Look, there is no doubt that you pressed the Control, Alt, and Delete keys. That is the only way that this could happen. It has happened a few times during this study. There are usually only two reasons for someone to do something like this. Either they were just goofing around to see what would happen or they were trying to ruin the experiment. I want to believe that you were just goofing around, but the only way I can know it is if you tell the truth and sign this paper. Otherwise, I have to assume that you did it to ruin the experiment.” No differences were found by condition.

Cole et al. (2005; unpublished presentation)

The purpose of this study was to replicate a study done by Kassin and Kiechel (1996; see below) but using a different task. More specifically, in the original Kassin and Kiechel paradigm, participants are accused of hitting the ALT key (which they had been told to avoid) and crashing the computer, and then asked to sign a (false) confession statement. In the Cole et al. study, participants are accused of breaking a lamp, an act which the authors argue is much less ambiguous. Fifty-five undergraduate students were accused of breaking the lamp and randomly assigned to either an incriminating false evidence condition (an accusatory approach, which was a confederate eyewitness falsely claiming to have seen the subject hit the lamp) or to the no false evidence condition (direct questioning). No participants in either condition falsely confessed.

Hill et al. (2008)

This publication consisted of three separate studies. Only Study 2 was eligible to be included here. In this study, 64 undergraduates from the University of Aberdeen self-selected themselves to be either innocent or guilty of cheating (accepting answers from a confederate) during a laboratory task. Half of the guilty and half of the innocent participants were questioned with guilt-presumptive questions (accusatory style), whereas the other half were questioned with neutral questions (control) and confession outcomes were measured. A main effect of interview style did not emerge for either true or false confessions.

Kassin and Kiechel (1996)

In this study, college students were invited into the laboratory to participate in a reaction time study. However, the actual purpose of the study was to investigate why persons falsely confess. Participants were placed at a computer and told not to hit the ALT key or the computer would crash. The computer did crash and participants were asked one or two times to sign a statement taking responsibility for crashing the computer (i.e., the false confession). Participants were randomly assigned to either a slow or fast pace condition (pace of reading off keys to hit on the computer) and randomly assigned to a false-evidence or no-false-evidence condition. In the false-evidence condition, a confederate claims to have seen the participant hit the ALT key. The false evidence condition was considered accusatorial style, while the no false evidence was considered direct questioning (control). The primary outcome was the number who signed the false confession which ranged from 35 to 100 % depending upon condition.

Meissner et al. (2011; unpublished manuscript)

Across two studies, the authors conducted a comparative analysis of information-gathering and accusatorial methods of interrogation. Using the Russano et al. (2005a) paradigm (explained above), guilty and innocent participants were exposed to either information-gathering, accusatorial, or direct questioning tactics, and the elicitation of true versus false confessions was recorded. The authors consistently observed that information-gathering methods reduced the likelihood of false confessions and increased the likelihood of true confessions.

Narchet et al. (2011)

This study investigated the role of interrogators’ perceptions of the guilt/innocence of suspect on the likelihood of eliciting true versus false confessions. Undergraduate students participated in a laboratory experiment using the Russano et al. (2005a) paradigm. The researchers evaluated the use of various interrogative approaches on the likelihood of confession, including both information-gathering and accusatorial methods, finding that information-gathering approaches significantly reduced the likelihood of false confessions.

Newring and O'Donohue (2008)

This study utilized a variant of the Kassin and Kiechel (1996) computer crash paradigm, but was the only study to employ a within-subject design. The authors did have a between-subjects condition of suspects (accused of crashing the computer) and witnesses (observed the computer crashing); only the suspect condition was included here. All subjects were interviewed in a 5-part process. The first part was a control question of “what happened” (direct questioning style). Subsequent parts, which were based on Reid approaches and thus categorized as accusatory for our purposes, included requests for written statement, verbal reviews of statements, and for explanations of what happened (the latter using the Reid Theme of “reducing the suspect’s feeling of guilt by minimizing the moral seriousness of the offense”, p. 93). Twenty-six undergraduates served as suspects. The main outcome was false confessions.

Perillo and Kassin (2011)

The authors conducted three studies examining the influence of the bluff technique on true (Study 3 only) and false (all studies) confessions. The bluff, categorized as an accusatorial approach here, is when interrogators insinuate there is incriminating evidence against suspects. Studies 1 and 2 utilized the Kassin and Kiechel (1996) paradigm. Study 1, which included 79 college students, had five conditions: no-tactics control, false witness evidence, the bluff technique, false witness and bluff combined, and a witness-affirmed innocence (another control condition). Study 2 included 44 college students using only the bluff and no-tactic control conditions. Study 3 utilized the Russano et al. (2005a) paradigm, and thus participants (72 college students) were randomly assigned to the guilt or innocent condition. The interview style conditions were bluff versus no-bluff (direct questioning control).

Redlich and Goodman (2003)

This study was a replication of the original Kassin and Kiechel study with some alterations. In addition to college students, juveniles aged 12 and 13, and 15 and 16 years were included to examine if juveniles were more likely to falsely confess than adults. The pace of reading keys was not manipulated and the false evidence was not an eyewitness confederate but rather a fake printout that demonstrated subjects (in that condition) hit the ALT key. Like the original study, the false-evidence condition was considered accusatorial, and no-false-evidence served as a direct questioning control condition. Also as in the original, all participants were innocent of the mock crime and thus false confessions were the outcome.

Russano et al. (2005a)

In this study, undergraduates came to a laboratory to participate in a study on problem-solving. During this task, half of the participants were induced to cheat via a confederate (the guilty condition), whereas the other half were not (innocent condition). All subjects were confronted with the possibility of cheating and interviewed using minimization techniques, a deal of leniency, both minimization and a deal, or neither (the direct questioning condition). The ratio of true to false confessions decreased with the use of accusatorial methods.

Russano et al. (2005b; unpublished presentation)

Using the Russano et al. (2005a) paradigm, the authors examined the influence of presenting false evidence to guilty and innocent participants on the likelihood of eliciting true versus false confessions, respectively. Participants in the false evidence condition were shown a written confession statement that appeared to have been signed by a second participant (a confederate to the experiment) prior to being asked to sign their own confession statement. Participants in the no false evidence condition were shown no such statement; they were simply asked to sign their own confession statement. Guilty participants were more likely to confess than innocent participants; however, there was no effect of presentation of false evidence on confession rates.

Results

Meta-analysis of observational field studies

The aim of the field study meta-analysis was to provide a quantitative assessment of the statistical association between the use of certain interrogation methods and the likelihood of eliciting confessions (regardless of veracity) in a real world context. Our primary measure of effect size was the logged odds-ratio (L OR ), consistent with the recommendations of Lipsey and Wilson (2001) for studies involving dichotomous outcomes (i.e., confess vs. not confess in the present analysis). The L OR , standard error (seL OR ), and weight (wL OR ) parameters were computed directly from the sample size and cell frequencies reported in each research article or were derived based upon the statistical information provided by authors (see Lipsey and Wilson 2001, pp. 52–55, for relevant formulae). The L OR was transformed into the Cox index, yielding the Hedge’s g effect size that is reported here (see Cox 1970; Lipsey and Wilson 2001; Sánchez-Meca et al. 2003).

We examined the relationship between the use of certain interrogative methods (accusatorial, information-gathering, or direct questioning methods) and the elicitation of a confession. A random effects model was used to estimate the mean weighted effect size for each association. Given the small number of samples within each effect size analysis (k ≤ 3), no moderator analyses were conducted.

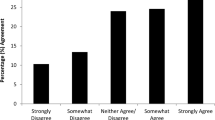

Table 3 provides the mean weighted effect size and 95 % confidence intervals calculated across each of the three interrogative methods. Estimates of homogeneity (Q) are also provided. Figure 1 provides a forest plot of effect sizes included in the analysis.

Accusatorial methods

Three empirical articles (k = 3, n = 306) assessed the relationship between use of accusatorial methods and elicitation of a confession statement in a real-world context. Consistent with the experimental literature, a random effects analysis demonstrated that the use of such methods was associated with a large and significant increase in confession rates (g = 0.90, z = 3.43, p < .001). There was no significant degree of variability across the studies (Q = 4.89, ns), and the findings appeared mildly robust given the small number of available studies.

Information-gathering methods

Two empirical articles (k = 2, n = 222) assessed the relationship between use of information-gathering methods and elicitation of a confession statement in a real-world context. Also consistent with the experimental literature, a random effects analysis found that the use of such methods was associated with a large and significant increase in confession rates (g = 0.86, z = 2.04, p < .05). A significant degree of variability between the two studies was observed (Q = 5.54, p < .05), though no moderator analysis was conducted due to sample size limitations. Sample size also limited the robustness of the finding.

Direct questioning methods

A number of tactics observed in these studies could reasonably be coded as a part of accusatorial and information-gathering approaches (as described previously). An analysis was conducted on the influence of these direct questioning methods in eliciting confessions in a real-world context as opposed to those methods that might be exclusively linked to either accusatorial or information-gathering approaches. Three empirical articles (k = 3, n = 422) assessed the relationship between such methods and elicitation of a confession statement. Results of a random effects analysis demonstrated no significant relationship between the use of these general methods and confession statements provided by suspects (g = 0.19, z = 0.41, ns). A significant degree of variability across the three samples was observed (Q = 25.35, p < .001), as might be expected from the combination of such generalized direct questioning methods. No moderator analysis was conducted due to sample size limitations.

Summary

The use of accusatorial and information-gathering methods of interrogation was significantly associated with the elicitation of confessions in a real-world context. While these results suggest that such methods are effective tools for elicitation of confessions, it is important to note that these findings fail to distinguish the diagnostic value of the information obtained—field studies offer little or no opportunity to distinguish between innocent and guilty suspects, and “ground truth” in such contexts is nearly impossible to determine. As such, researchers have assessed the diagnostic value of certain interrogative methods by modeling the interrogative process in an experimental, laboratory context. We turn now to a meta-analysis of these studies as a method for further assessing the diagnostic value of accusatorial and information-gathering approaches.

Meta-analysis of experimental laboratory studies

The aim of the current meta-analysis was to provide a quantitative assessment the statistical effect of certain interrogation methods on the likelihood of eliciting true versus false confessions for studies conducted in an experimental, laboratory context. Again, our primary measure of effect size was the logged odds-ratio (L OR ). The L OR was transformed into the Cox index, yielding Hedge’s g.

We examined the contrasting effects of accusatorial, information-gathering, and direct questioning (control) methods across the outcomes of both true and false confessions. The number of independent samples (k) contributing to each contrast differed substantially, as can be seen in Table 4. A random effects model was used to estimate the mean weighted effect size for each comparison. Our analysis of moderating variables was limited due to the small number of independent samples in each contrast, though we address the role of publication bias and include a moderator analysis when appropriate. Table 4 also provides the mean weighted effect size and 95 % confidence intervals calculated for outcomes of true confessions and false confessions across each of the three interrogative contrasts. Estimates of homogeneity (Q) are also provided.

Direct questioning versus accusatorial contrast

The contrast between an accusatorial interrogative method and a direct questioning interview condition was most frequently represented in the experimental research literature, though researchers more often assessed the effects on false confessions (k = 14, n = 892) compared with true confessions (k = 6, n = 272). A random effects analysis across studies demonstrated that accusatorial methods yielded a significant increase in the frequency of both true confessions (g = 0.46, z = 2.24, p < .05) and false confessions (g = 0.74, z = 3.75, p < .001). While these represent medium-to-large effects, only the contrast on false confessions appears robust and tests of homogeneity were similarly only significant for the outcome of false confessions (Q = 32.99, p < .01). Figure 2 provides a forest plot of effect sizes for each study included in the analysis of true and false confessions.

A number of variables were considered for inclusion in a moderator analysis of the influence of accusatorial methods in eliciting false confessions. Unfortunately, studies varied little in several key variables of interest. For example, only 2 of the 14 independent samples involved children or adolescents (i.e., Billings et al. 2007; Redlich and Goodman 2003), while the remainder involved college students. In addition, none of the studies manipulated race or ethnicity in participant recruitment or analyses of the data. Similarly, only 1 of the 14 samples was conducted outside of the United States (i.e., Hill et al. 2008). Finally, a mix of accusatorial methods were employed across studies, including aspects of minimization, maximization, presentation of false evidence, and various combinations therein – although we coded the inclusion of such methods across studies, there was too much variability across studies in the application of accusatorial methods to conduct an informative moderator analysis along this dimension. This is rather unfortunate, as such a variable is likely to account for significant variance with respect to this effect size analysis.

One variable that appeared to vary systematically across studies involved the use of different experimental paradigms, including the Kassin and Kiechel (1996) “ALT key” paradigm (k = 6) and the Russano et al. (2005a) “cheating” paradigm (k = 6). A moderator analysis of these two sets of studies showed no significant difference in the effect sizes produced. Both the Kassin and Kiechel paradigm (g = 0.66, z = 2.14, p < .05, with 95 % CI: 0.05, 1.27) and the Russano et al. paradigm (g = 0.93, z = 4.00, p < .001, with 95 % CI: 0.47, 1.38) yielded medium-to-large effects demonstrating that accusatorial methods significantly increased false confession rates (when compared with a direct questioning condition).

Direct questioning versus information-gathering contrast

Only two studies examined the influence of information-gathering interrogative methods (versus that of a direct questioning control condition) in eliciting true confessions (k = 2, n = 110) and false confessions (k = 2, n = 110). A random effects analysis of these studies demonstrated that information-gathering methods yielded a greater frequency of true confessions (g = 0.67, z = 2.02, p < .05), but did not significantly influence the likelihood of eliciting false confessions (g = −0.23, z = −0.60, ns). Given the small number of studies, the lack of a robust effect on true confessions was not surprising, and neither effect size analysis demonstrated significant variability from which to assess moderator effects (Qs < 1.41, ns). Figure 3 provides a forest plot of effect sizes for each study included in the analysis of true and false confessions.

Accusatorial versus information-gathering contrast

Three studies assessed the direct contrast between accusatorial and information-gathering interrogative methods in eliciting true confessions (k = 3, n = 215) and false confessions (k = 3, n = 215). A random effects analysis demonstrated that information-gathering methods produced a significantly greater frequency of true confessions (g = 0.64, z = 1.97, p < .05), while significantly reducing the frequency of false confessions (g = −0.77, z = 2.19, p < .05), when compared with accusatorial methods. These medium-to-large effect sizes were not particularly robust. Similarly, neither analysis produced significant variability to warrant a moderator analysis (Qs < 4.43, ns). Figure 4 provides a forest plot of effect sizes for each study included in the analysis of true and false confessions.

Summary

A small, but growing, experimental literature has assessed the influence of information-gathering and accusatorial interrogative methods in eliciting true versus false confessions. While both methods increase the likelihood of obtaining a true confession from a guilty participant when compared with a direct questioning control condition, accusatorial methods also significantly increase the likelihood of obtaining a false confession from an innocent participant. When contrasted with one another, information-gathering methods of interrogation proved more diagnostic—they elicited a greater proportion of true confessions, while significantly reducing the likelihood of false confession.

Discussion

We begin by noting the relatively sparse experimental and field literature evaluating the systematic influence of interrogative methods in eliciting true and false confessions. Although we found significant and sometimes robust effects, the number of independent samples, particularly for information-gathering approach and for true confessions, limits our ability to make definitive conclusions. Here, we briefly discuss the findings of the field study and experimental study meta-analyses, then conclude our review by discussing the implications of our analyses for policy and practice.

Field study conclusions

Our review of the available field study literature located 33 potentially eligible observational studies on interrogation, though only 5 of these studies empirically assessed the relationship between interrogative approaches and elicitation of a confession. That so few studies have assessed this relationship was surprising to us, particularly in light of the clear need for research and evidence-based policy recommendations on this issue (see Kassin et al. 2010).

Analysis of the field studies suggests that both accusatorial and information-gathering methods are associated with a significant increase in the likelihood of obtaining a confession statement, producing large effect sizes that are not particularly robust given the small number of available studies. Interestingly, methods that might be considered general, direct questioning approaches that are shared across these methods failed to show a significant association with elicitation of a confession. Thus, it appears that the techniques that truly distinguish between the information-gathering and the accusatorial approach are those associated with generating confessions.

It is important here to note that field studies fail to offer us important information regarding the relative diagnostic value of the confession that is elicited. That is, such studies lack “ground truth” that would enable us to factually determine the veracity of the statement provided by a suspect, and thereby preclude our ability to assess the diagnostic value of the information elicited and therein the effectiveness of such techniques when employed in the field. One method often used to assess veracity in field studies has been to evaluate the “strength” of available evidence against the defendant (cf. Behrman and Davey 2001; Leo and Ofshe 1998); however, none of the studies took this approach to evaluating the likely credibility of the confession obtained as a moderator of interrogative efficacy.

We also note here that each of the studies included in the field study meta-analysis examined the bivariate relationship between certain interrogative methods and elicitation of a confession. As indicated in our review of the available literature, a number of control variables could reasonably be included in such analyses (e.g., factors related to interrogator experience, crime type, interrogator/suspect ethnic backgrounds, geographic characteristics, etc.), and more complex modeling approaches (such as multi-level modeling or path analysis) could have been pursued, albeit many (if not all) of these studies may not have had sufficient sample sizes to consider multiple factors simultaneously. We strongly encourage researchers to obtain larger samples and initiate more systematic, multi-level analyses of the influence of interrogative methods. Further, there is a great need for the use of quasi-experimental methods in this field context as our understanding of the effects of certain interrogative methods matures. Quasi-experimental methods could include the random assignment of certain factors in real-world interviews and interrogations, such as the use of the Cognitive Interview, whether suspects are told they are being recorded, and many of the variables under consideration here. Such quasi-experimental methods are effective tools for assessing the policy implications of alternative approaches to police interviewing and interrogation, and should be considered in the years ahead.

Experimental laboratory study conclusions

While a total of 22 experimental, laboratory studies on interrogation were potentially eligible, only 12 of these studies manipulated interrogative methods and assessed their influence on key outcomes (i.e., true and/or false confessions). The majority of the excluded studies were not focused on interrogation style per se, but rather on certain dispositional factors. For instance, studies conducted by Forrest et al. (2006), Horselenberg et al. (2003), and Klaver et al. (2008) utilized the Kassin and Kiechel paradigm but did not manipulate interrogation style. Klaver et al. manipulated plausibility of committing the crime, whereas Forrest et al. and Horselenberg et al. concentrated on individual suspect differences.

A meta-analysis of the eligible experimental literature demonstrated several key findings that may have implications for policy and practice. First, while accusatorial methods significantly increased the likelihood of obtaining a true confession (when compared with a direct questioning control condition), these methods also significantly increased the likelihood of obtaining a false confession—a medium-to-large effect that is consistent with many cases of wrongful conviction in the United States (see Kassin et al. 2010). In contrast to this, information-gathering approaches significantly increased true confession rates, but showed no significant increase in the rate of false confessions when compared with a direct questioning condition. In fact, information-gathering approaches appeared to show a numerical decrease in the rate of false confessions obtained. When compared directly against accusatorial methods, information-gathering approaches showed superior diagnosticity by significantly increasing the elicitation of true confessions and significantly reducing the incidence of false confessions. Although not particularly robust due to the small number of studies, these medium-to-large effects suggest that information-gathering approaches may be preferable for the collection of more diagnostic confession evidence.

Given the small number of available studies in this literature, it is not surprising that the current findings lack a degree of robustness. Although the studies included met appropriate standards of methodological rigor, it is imperative that further research be conducted to replicate and extend the current findings.

Policy implications

In accomplishing this systematic review, it became readily clear to us that the current experimental and field study literatures must continue to mature if we are to offer a complete understanding of the various psychological, sociological, criminological, and cultural factors that influence the interrogative process. While we have a robust understanding of factors that lead to false confessions in an interrogative context (see Kassin et al. 2010), only a limited literature exists to assess the value of alternative methods of interrogation that might promote the diagnostic elicitation of confession evidence in the law enforcement context (see Meissner et al. 2010a), or the elicitation of critical knowledge in a military or intelligence context (see Evans et al. 2010; Hartwig et al. 2014; Redlich 2007). The current analysis suggests that information-gathering approaches introduced by the United Kingdom and other countries (see Bull and Soukara 2010) can be equally effective in eliciting confessions when compared with accusatorial methods, but also have the advantage of eliciting more diagnostic information. In the experimental meta-analysis, when the information-gathering and accusatorial approaches were contrasted, the information-gathering approach clearly produced more advantageous outcomes (although caution is warranted given the small number of eligible studies). Specifically, the information-gathering approach produced significantly more true confessions, whereas the accusatorial approach produced significantly more false confessions. As such, the current analysis suggests that law enforcement, military, and intelligence agencies should consider the use of information-gathering approaches to interrogation. Finally, we emphasize that additional research should be conducted to further refine and solidify our understanding of the effects of various interrogative methods in eliciting true and false confessions, therein providing a stronger foundation for evidence-based practice and policy recommendations.

References

* Studies included in the meta-analysis are denoted with an asterisk.

Abboud, B., Wadkins, T. A., Forrest, K. D., Lange, J., & Alavi, S. (2002, March). False confessions: Is the gender of the interrogator a determining factor? Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the American Psychology-Law Society, Austin, TX.

Baldwin, J. (1992). Videotaping police interviews with suspects: A national evaluation. Police Research Series Paper 1. London: Home Office.

Baldwin, J. (1993). Police interview techniques: establishing truth or proof? British Journal of Criminology, 33, 325–352.

Behrman, B. W., & Davey, S. L. (2001). Eyewitness identification in actual criminal cases: An archival analysis. Law & Human Behavior, 25, 475–491.

Beune, K. (2009). Talking heads: Interviewing suspects from a cultural perspective. Doctoral dissertation, University of Twente.

Beune, K., Giebels, E., & Sanders, K. (2009). Are you talking to me? Influencing behavior and culture in police interviews. Psychology, Crime & Law, 15, 597–617.

* Billings, F. J., Taylor, T., Burns, J., Corey, D. L., Garven, S., & Wood, J. M. (2007). Can reinforcement induce children to falsely incriminate themselves? Law & Human Behavior, 31, 125–139.

* Blair, J. P. (2007). The roles of interrogation, perception, and individual differences in producing compliant false confessions. Psychology, Crime, & Law, 13, 173–186.

Bull, R., & Soukara, S. (2010). What really happens in police interviews. In G. D. Lassiter & C. A. Meissner (Eds.), Police interrogations and false confessions: Current research, practice, and policy recommendations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bull, R., Valentine, T., & Williamson, T. (2009). Handbook of psychology of investigative interviewing. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Cassell, P. G., & Hyman, B. S. (1996). Dialogue on Miranda: police interrogation in the 1990s: an empirical study of the effects of Miranda. UCLA Law Review, 43, 839.

* Cole, T., Teboul, J. C., Zulawski, D., Wicklander, D., & Sturman, S. (2005). Trying to obtain false confessions through the use of false evidence: A replication of Kassin and Kiechel’s study. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, New York, NY. Retrieved December 19, 2008. http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p13137_index.html.

Costanzo, M. & Redlich, A. (2010). Use of physical and psychological force in criminal and military interrogations. In J. Knuttsson, & J. Kuhns (Eds.), Policing around the world: Police use of force. Santa Barbara: Praeger Security International.

Cox, D. R. (1970). Analysis of binary data. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC.

DePaulo, B. M., Lindsay, J. J., Malone, B. E., Muhlenbruck, L., Charlton, K., & Cooper, H. (2003). Cues to deception. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 74–118.

DesLauriers-Varin, N., Lussier, P., & St-Yves, M. (2011). Confessing their crime: factors influencing the offender’s decision to confess to the police. Justice Quarterly, 28, 113–145.

Dixon, D. (2007). Interrogating images: Audio-visually recorded police questioning of suspects. Sydney: Sydney Institute of Criminology.

Evans, J. R., Meissner, C. A., Brandon, S. E., Russano, M. B., & Kleinman, S. M. (2010). Criminal versus HUMINT interrogations: the importance of psychological science to improving interrogative practice. Journal of Psychiatry and Law, 38, 215–249.

Evans, J. R., Meissner, C. A., Ross, A. B., Houston, K. A., Russano, M. B., & Horgan, A. J. (2013). Obtaining guilty knowledge in human intelligence interrogations: comparing accusatorial and information-gathering approaches with a novel experimental paradigm. Journal of Applied Research in Memory & Cognition, 2, 83–88.

Faller, K. C., Birdsall, W. C., Henry, J., Vandervort, F., & Silverschanz, P. (2001). What makes sex offender confess? An exploratory study. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 10, 31–49.

Fein, R. (2006). Educing information. Interrogation: Science and art. Intelligence science board, phase 1 report. Washington, DC: National Defense Intelligence College.

Feld, B. C. (2006). Police interrogation of juveniles: an empirical study of policy and practice. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 97, 219–316.

Feld, B. C. (2013). Kids, cops, and confessions: Inside the interrogation room. New York: New York University Press.

Fisher, R. P., & Geiselman, R. E. (1992). Memory enhancing techniques for investigative interviewing: The cognitive interview. Springfield: Charles C Thomas.

Fisher, R. P., & Perez, V. (2007). Memory-enhancing techniques for interviewing crime suspects. In S. Christianson (Ed.), Offenders’ memories of violent crimes (pp. 329–350). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Forrest, K. D., Wadkins, T. A., & Larson, B. A. (2006). Suspect personality, police interrogations, and false confessions: maybe it is not just the situation. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 621–628.

Griffiths, A. (2008). An examination into the efficacy of police advanced investigative interview training. Doctoral dissertation, University of Portsmouth.

Gudjonsson, G. H. (2003). The psychology of interrogations and confessions. Chichester: Wiley.

Hartwig, M., Meissner, C. A., & Semmel, M. D. (2014). Human intelligence interviewing and interrogation: Assessing the challenges of developing an ethical, evidence-based approach. In R. Bull (Ed.), Investigative interviewing (pp. 209–228). Springer.

* Hill, C., Memon, A., & McGeorge, P. (2008). The role of confirmation bias in suspect interviews: A systematic evaluation. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 13, 357–371.

Home Office. (2003). Police and criminal evidence act 1984. Codes of practice A-E revised edition. London: HMSO.

Horgan, A. J., Russano, M. B., Meissner, C. A., & Evans, J. (2012). Minimization and maximization techniques: assessing the perceived consequences of confessing and confession diagnosticity. Psychology, Crime & Law, 18, 65–78.

Horselenberg, R., Merckelbach, H., & Josephs, S. (2003). Individual differences and false confessions: a conceptual replication of Kassin and Kiechel. Psychology, Crime & Law, 9, 1–8.

Inbau, F. E., Reid, J. E., Buckley, J. P., & Jayne, B. C. (2001). Criminal interrogation and confessions (4th ed.). Gaithersberg: Aspen.

Justice, B. P., Bhatt, S., Brandon, S. E., & Kleinman, S. M. (2009). Army field manual 2–22.3 interrogation methods: A science-based review. Unpublished manuscript.

Kassin, S. M., Goldstein, C. C., & Savitsky, K. (2003). Behavioral confirmation in the interrogation room: On the dangers of presuming guilt. Law & Human Behavior, 27, 187–203.

Kassin, S. M., & Gudjonsson, G. H. (2004). The psychology of confessions: a review of the literature and issues. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5, 33–67.

* Kassin, S. M., & Kiechel, K. L. (1996). The social psychology of false confessions: compliance, internalization, and confabulation. Psychological Science, 7, 125–128.

Kassin, S. M., Leo, R. A., Meissner, C. A., Richman, K. D., Colwell, L. H., Leach, A.-M., et al. (2007). Police interviewing and interrogation: a self-report survey of police practices and beliefs. Law and Human Behavior, 31, 381–400.

Kassin, S. M., Drizin, S. A., Grisso, T., Gudjonsson, G. H., Leo, R. A., & Redlich, A. D. (2010). Police-induced confessions: risk factors and recommendations. Law and Human Behavior, 34, 3–38.

Kebbell, M. R., & Daniels, T. (2006). Mock-suspects’ decisions to confess: the influence of eyewitness statements and identifications. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law, 13, 261–268.

Kebbell, M. R., Hurren, E. J., & Roberts, S. (2006). Mock-suspects’ decisions to confess: the accuracy of eyewitness evidence is critical. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20, 477–486.

* King, L. & Snook, B. (2009). Peering inside a Canadian interrogation room: an examination of the Reid model of interrogation, influence tactics, and coercive strategies. Criminal Justice & Behavior, 36, 674–694.

Klaver, J., Lee, Z., & Rose, V. G. (2008). Effects of personality, interrogation techniques, and plausibility in an experimental false confession paradigm. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 13, 71–88.

Lassiter, G. D., & Meissner, C. A. (2010). Police interrogations and false confessions: Current research, practice, and policy recommendations. Washington, DC: APA.

* Leo, R. A. (1996). Inside the interrogation room. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 86, 266–303.

Leo, R. A. (2008). Police interrogation and American justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Leo, R. A., & Ofshe, R. (1998). The consequences of false confessions: deprivations of liberty and miscarriages of justice in the age of psychological interrogation. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 88, 429–496.

Lippert, T., Cross, T. P., Jones, L. M., & Walsh, W. (2010). Suspect confession of child sexual abuse to investigators. Child Maltreatment, 15, 161–170.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Ma, Y. (2007). A comparative view of the law of interrogation. International Criminal Justice Review, 17, 5–26.

McConville, M., & Baldwin, J. (1982). The role of interrogation in crime discovery and conviction. British Journal of Criminology, 22, 165–175.

McGurk, B., Carr, M., & McGurk, D. (1993). Investigative interviewing courses for police officers: An evaluation. Police Research Group Paper 4. London: Home Office.

Medalie, R. J., Zeitz, & Alexander. (1968). Custodial police interrogation in our nation’s capital: the attempt to implement Miranda. Michigan Law Review, 66, 1347.

Medford, S., Gudjonsson, G. H., & Pearse, J. (2003). The efficacy of the appropriate adult safeguard during police interviewing. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 8, 253–266.

Meissner, C. A., & Kassin, S. M. (2002). “He’s guilty!”: investigator bias in judgments of truth and deception. Law and Human Behavior, 26, 469–480.

Meissner, C. A., & Kassin, S. M. (2004). “You’re guilty, so just confess!”: Cognitive and behavioral confirmation biases in the interrogation room. In D. Lassiter’s (Ed.), Interrogations, confessions, and entrapment (pp. 85–106). Kluwer Academic / Plenum Press.

Meissner, C. A., Hartwig, M., & Russano, M. B. (2010a). The need for a positive psychological approach and collaborative effort for improving practice in the interrogation room. Law and Human Behavior, 34, 43–45.

Meissner, C. A., Russano, M. B., & Narchet, F. M. (2010b). The importance of a laboratory science for improving the diagnostic value of confession evidence. In G. D. Lassiter & C. Meissner’s (Eds.), Interrogations and confessions: Research, practice, and policy. Washington, DC: APA.

* Meissner, C. A., Russano, M. B., Rigoni, M. E., & Horgan, A. J. (2011). Is it time for a revolution in the interrogation room? Empirically validating information-gathering methods. Unpublished manuscript.

Memon, A., Meissner, C. A., & Faser, J. (2010). The Cognitive Interview: a meta-analytic review and study space analysis of the past 25 years. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 16, 340–372.

Milne, R., & Bull, R. (1999). Investigative interviewing: Psychology and practice. Chichester: Wiley.

Mortimer, A., & Shepherd, E. (1999). Frames of mind: Schemata guiding cognition and conduct in the interviewing of suspected offenders. In A. Memon & R. Bull (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of interviewing (pp. 293–315). Chichester: Wiley.

Moston, S., Stephenson, G. M., & Williamson, T. M. (1992). The effects of case characteristics on suspect behaviour during questioning. British Journal of Criminology, 32, 23–40.

* Narchet, F., Meissner, C. A., & Russano, M. B. (2011). Modeling the influence of investigator bias on the elicitation of true and false confessions. Law and Human Behavior, 35, 452–465.

Nash, R. A., & Wade, K. A. (2009). Innocent but proven guilty: eliciting internalized false confessions using doctored-video evidence. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23, 624–637.

Neubauer, D. W. (1974). Confessions in Prairie City: some causes and effects. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 65, 103–112.

New Haven Study. (1967). Interrogations in New Haven: the impact of Miranda. Yale Law Journal, 76, 1519.

* Newring, K. A. B., & O'Donohue, W. (2008). False confessions and influenced witness statements. Applied Psychology in Criminal Justice, 4, 81–107.

Pearse, J. J. (2009). The investigation of terrorist offences in the United Kingdom: The context and climate for interviewing officers. In R. Bull, T. Valentine, & T. Williamson (Eds.), Handbook of psychology of investigative interviewing (pp. 69–90). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Pearse, J., & Gudjonsson, G. (1999). Measuring influential police interviewing tactics: a factor analytic approach. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 4, 221–238.

* Pearse, J., Gudjonsson, G. H., Clare, I. C. H., & Rutter, S. (1998). Police interviewing and psychological vulnerabilities: predicting the likelihood of a confession. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 8, 1–21.

* Perillo, J. T. & Kassin, S. M. (2011). Inside interrogation: the lie, the bluff, and false confessions. Law and Human Behavior, 35, 327–337.

Redlich, A. D. (2007). Military versus police interrogations: similarities and differences. Peace & Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 13, 423–428.

* Redlich, A. D., & Goodman, G. S. (2003). Taking responsibility for an act not committed: the influence of age and suggestibility. Law and Human Behavior, 27, 141–156.