Abstract

Enabled by the underpinnings of critical theory, this article discusses research methodology developed with the aim of empowering beneficiaries within Third Sector Organisations, through their participation in organisational evaluation processes. The discussion on methodology in this article occurs at three levels: conceptual, processual, and reflexive. The conceptual level explores ontological and epistemological assumptions that shape the critical approach. At the processual level, research methods are explored, drawing on case studies involving interviews with beneficiaries. In interviewing beneficiaries, Third Sector research becomes a means of representing this group. Finally, the reflexive level explores how findings from the processual level enable praxis through the development of approaches supporting beneficiaries’ participation in organisational evaluation processes. As such, Third Sector research can engage beneficiary participation, in order to promote more effective beneficiary participation organisationally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This article explores methodology used within Third Sector research considering beneficiary participative evaluation. Beneficiary stakeholder groups are frequently underrepresented within Third Sector accountability and evaluation processes (Ebrahim, 2016; Mathison, 2018; Murtaza, 2012). This underrepresentation reflects organisational asymmetric power relations and beneficiaries’ limited ability to hold the organisation to account (Jacobs & Wilford, 2010). In this light, a lack of beneficiary voice or ability to be heard within Third Sector Organisations (TSOs) is identified as a broad research problem. Third Sector research has been motivated to respond to this underrepresentation through empowering marginalised beneficiary groups (Kennedy, 2019; Kilby, 2006) via both research design and outcomes (Kingston et al., 2020), and as such is embedded within critical theory motivations. Here, “critical research can be best understood in the context of the empowerment of individuals. Inquiry that aspired to the name critical must be connected to an attempt to confront the injustice of a particular society or public sphere within the society” (Kincheloe & McLaren, 2011, p. 300).

Beneficiary participative evaluation is considered a way to increase beneficiary voice and strengthen accountability toward beneficiaries (Ebrahim, 2003; Kingston et al., 2019; Wellens & Jegers, 2016). The case study research discussed within this article specifically questioned how participative evaluation (Greene, 1997) can enhance accountability to beneficiaries within TSOs (Kingston et al., 2020). Here, epistemological assumptions related to how the creation of knowledge can be empowering, point to an importance of directly asking beneficiaries their experiences of and thoughts on participative evaluation. This demonstrates a “commitment to involving the people in the setting being studied as co-inquirers” (Patton, 2015, p. 222). In this way, the research engages beneficiary participation, in order to promote more effective beneficiary participation organisationally.

Methodology can move beyond data collection and interpretation, toward becoming an active process enabling change. The “methodological aspects of critical theory can create this movement” (Laughlin, 1987, p. 482). Being aware of the potential to enable change (both positive and negative) is important when researching with typically underrepresented research participants. This article examines methodological approaches that aim to provoke change and empower beneficiaries through their involvement in research and its outputs. This is in response to research practices globally that note beneficiaries’ lack of power and identify recommendations for how this might be changed but fall short of contributing to facilitate that change. In light of this, whilst the methodology discussed here was used within an Australian context, findings may enhance research internationally, in contexts where beneficiary empowerment is focal.

In order to expose underlying research assumptions, the discussion on methodology occurs at three distinct levels: conceptual, processual, and reflexive. These levels provide three important yet complementary perspectives of how the methodological approach is shaped, employed, and applied. At the conceptual level, the ontological and epistemological assumptions that shape the research approach are illuminated. At the processual level, research methods are explored. A highlight of this level includes reflecting on case studies involving interviews with beneficiary stakeholders, a group known to be difficult to access within Third Sector research (Yang & Northcott, 2019). In this way, the research itself becomes a means of enabling empowerment towards this frequently underrepresented group through creating a platform to hear beneficiary voice. Finally, the reflexive level explores how the findings from the processual level enable praxis through the development of further organisational processes supporting beneficiaries’ participation in evaluation, as a means of evaluating with beneficiaries rather than on them (Patton, 2015). In exploring these three levels, the complexity and value of the research methodology is examined.

The article begins with a background discussion situating understanding of critical theory and of beneficiaries’ position in TSOs within extant literature. Following this, and in keeping with the focus upon methodology, the body of the article presents the conceptual, processual, and reflexive levels of methodology. The article concludes by illuminating contributions and limitations of the research methodology, particularly relevant when research involves participants with asymmetric power relations.

Background

Critical theory is a theoretical tradition typically attributed to writers in the 1920-30s at the University of Frankfurt, referred to as the Frankfurt School (e.g., Adorno, Fromm, Marcuse). Critical theory attempts to disrupt and challenge the status quo (Kincheloe & McLaren, 2011) and places a judgement upon (a constructed) reality (Scotland, 2012). Applying a critical approach to research suggests a normative or prescriptive stance (Chiapello, 2017; Gendron, 2018). Whilst other research approaches may seek to describe or represent a phenomenon, critical research seeks to change social relations and enhance social equality (Catchpowle & Smyth, 2016; Rose & Johnson, 2020). In this light, this article examines research that has a core motivation to respond to social injustices through the empowerment of marginalised groups.

The focus here is upon beneficiaries of TSOs. Beneficiaries, described as stakeholders receiving services intended to benefit (Wellens & Jegers, 2017), are considered both the raison d'être of TSOs (Chen et al., 2019) and important organisational actors (Benjamin, 2020). Yet, they present as marginalised in relation to more powerful stakeholder such as regulators and resource providers (Cordery & Sim, 2018). Beneficiary participation in evaluation processes may be a means of reducing this marginalisation through increasing beneficiary representation, potentially leading to empowerment and enhanced social equality (Kingston et al., 2020). Practical rationales for stakeholder participation in evaluation, including organisational decision-making and problem-solving, sit alongside rationales that support increased social justice and empowerment (Cousins & Whitmore, 2007). Additionally, the participation of beneficiaries within evaluation processes may improve organisational accountability toward beneficiaries, a stakeholder group considered in need of increased accountability engagement (Yasmin et al., 2020). Yet despite the importance of accountability toward beneficiaries in TSOs (Chu & Luke, 2018), empirical research in this area is considered scarce (van Zyl et al., 2019).

The approach to researching with beneficiaries detailed in this article, presents potential benefits at both the individual and organisational level. At the individual level, benefits stem from beneficiaries’ participation within the research process, which creates a platform for their voices to be heard. This in itself is a potentially empowering process as beneficiaries are listened to, valued, and included within the research space. At an organisational level, the benefits of hearing beneficiaries’ voices include increased awareness and potential for enhanced evaluation practices, leading to more effective accountability processes.

Embarking on a research project that actively seeks to respond to social inequalities requires understanding and articulating underlying assumptions of the researcher, toward how social injustices are shaped and perpetuated. The following Section expressly considers these assumptions through illuminating the paradigm within which such research is situated. As noted by Martinez and Cooper (2020, p. 1), “…paradigms impact the way we both represent and intervene in the world…”. Therefore, it is important to uncover world views that inform and construct how research both represents and responds to reality. This uncovering can be aided by considering the conceptual, processual, and reflexive aspects of a methodological approach.

Methodology

Conceptual

Matching the ontological and epistemological underpinnings of a research project to the research objective is important toward ensuring there is no inherent conflict, after all “the types of research questions we generate grow out of our ontology” (Berryman, 2019, p. 273). Furthermore, ontological assumptions shape human action (Sullivan, 2017), impacting upon both the nature of the work of TSOs and what they are capable of achieving.

Ontology is the study of being, of what constitutes reality (Crotty, 1998; Scotland, 2012). Critical theory acknowledges realities are shaped and constructed by social, political, cultural, economic, ethnic, and gender values (Scotland, 2012), historically constituted, produced, and reproduced (Myers, 2009). Within this critical paradigm (Guba & Lincoln, 1998), language actively shapes reality and constructs relations of power, capable of empowerment or disempowerment (Scotland, 2012). Importantly for this research, Rexhepi and Torres (2011) suggest critical theory capable of empowering stakeholders.

Epistemology concerns what it means to know, or how knowledge can be created and communicated (Scotland, 2012). Within a social-constructionist view, “knowledge itself is socially constructed and facts are social products” (Cunliffe, 2008, p. 125). Framing this epistemological view within a critical paradigm reinforces that knowledge is shaped by societal structures and the dominant ideology (Patton, 2015). Here, socially constructed knowledge is entangled within power relations and historically positioned (Scotland, 2012; Wedeen, 2010). Within a critical paradigm researchers seek to understand both social life and lived experience (Schwandt & Gates, 2018) and address issues of social justice and marginalisation. However, to go beyond a merely conceptual representation, research within this critical positioning needs to move toward activating social change. This movement begins within the processual level.

Processual

The methodology of critical theory questions ideology and attempts to create action in order to instigate social justice (Crotty, 1998). An aim of critical research methodology is to empower the disempowered, in doing so acknowledging the politicality of research design (Lather, 2013). Indeed, even the quality of critical research may in part be determined by “its ability to act as a catalyst for social or political change” (Rose & Johnson, 2020, p. 437).

Within the critical paradigm, the achievement of change frequently involves an iterative relationship between theory, data, research questions, and analysis (Scotland, 2012). This recursive relationship within critical methodology positions research as abductive in relation to theory development (Saunders et al., 2016).

The focus of this article reflects upon case study research involving two Australian-based TSOs, that specifically questioned how participative evaluation can enhance organisational accountability to beneficiaries (see Kingston et al., 2020). The case study research involved data from semi-structured interviews and organisational and legislative documents. The multiple sources of data helped to strengthen the credibility of findings (Shenton, 2004).

Whilst interviewing is a common qualitative research method and is not particular to a critical paradigm, the critical motivation moves interviewing away from seeking truths toward constructing new knowledge (Kvale, 2008), with the aim of enabling social change. Semi-structured interviews are appropriate to a critical research paradigm due to their ability to make use of dialogue as a knowledge-producing agent (Brinkmann, 2018). Denzin (2001) imagines a world where language empowers, stressing that words matter and interviews to be dialogic conversations. The semi-structured approach supported beneficiaries’ shaping the interview process and questions asked, impacting upon the research itself. This structure enabled and encouraged beneficiaries to tell their stories. In this regard, a beneficiary commented “I've got a bit of a hard-luck story and it is empowering to hear my story” (beneficiary interviewee). In keeping with these views, interviewing beneficiaries supports a research motivation to empower beneficiaries through hearing their voices within the research process and using those voices to influence further change (as described in the Reflexive Section). In this regard, interview transcripts are viewed as “…critically empowering texts…” (Denzin, 2001, p. 24).

As noted earlier, beneficiaries are considered a difficult stakeholder group to access within Third Sector research, especially where services received are sensitive in nature (Yang & Northcott, 2019). Yet, embedding research within critical motivations seeking to empower marginal stakeholder groupings, emphasises the importance of talking directly with beneficiaries, rather than allowing someone else to speak for them (Alcoff, 1992). The perspectives of beneficiaries have been heard through interviews within Third Sector research (Awio et al., 2011; Connolly & Hyndman, 2017; Mercelis et al., 2016; Walsh, 2016). Whilst some have involved beneficiaries in the data collection process, few have systematically analysed and reflected on the importance of this methodological approach as a means of empowerment via research participation.

Within the case study research (Kingston et al., 2020), identifying beneficiaries willing to be interviewed was aided by a trusted third party within each organisation’s external environment, who was able to introduce participants to the researcher through snowball sampling techniques. Snowball sampling is considered appropriate when members of a population are hard to locate and for exploratory research (Babbie, 2015).

How to engage beneficiaries in the interviews was an important consideration. After deliberation, the most suitable way to engage beneficiaries mirrored the ways they interact within their respective organisations. Where beneficiaries engaged regularly onsite, the interviews were conducted onsite. Where beneficiaries did not regularly engage onsite, beneficiaries nominated their preferred venue for the interview. Highlighted here is the need for researcher flexibility in adapting to individual beneficiaries’ needs.

Ensuring beneficiaries felt comfortable and safe within the interview was also a key consideration toward encouraging participation. Again, the approach mirrored beneficiaries’ involvement within their TSO and differed across the two organisations. Where beneficiaries physically engaged regularly within their TSO, more vulnerable beneficiaries felt safer to be interviewed within their organisation. This setting assisted in reducing power imbalances between the researcher and beneficiaries, by placing the researcher in the foreign place, rather than the beneficiary. Leaving this familiar environment could have amplified power asymmetries between the researcher and beneficiary. Where beneficiaries did not regularly engage onsite and had less dependency upon the TSO, interview locations were influenced by beneficiary convenience. Thus, the importance of minimising discomfort within interview settings (a potential source of disempowerment) is highlighted.

Within the two case studies, interviews were also conducted with staff and board members. These interviews were all conducted within the participant’s organisation, excepting one board member who nominated a phone interview. Interviews with participants from three stakeholder groups (beneficiary, staff, and board members) enabled a richer understanding of similarities and differences amongst participants and a more contextualised understanding. In total, 14 interviews were conducted across the two cases. As Miles et al. (2014) highlight, within qualitative research, researchers typically work with small samples of people located within their case, providing opportunity for theoretical rather than statistical generalisation.

Data was analysed thematically, searching for themes and patterns (Saunders et al., 2016). The analysis was assisted by the use of the QSR NVivo software which helped to support data analysis, arrangement, and management (Ponelis, 2015). To strengthen the credibility of the findings, phases of thematic analysis suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006) were followed. These included becoming familiar with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and lastly, producing the report. Interpretation and analysis involved developing case records and case narratives (Patton, 2015). The analysis included a cross-case comparison which was used to enhance the “situationally and complex interaction of case knowledge”, subsequently deepening understanding of the individual cases (Stake, 2006, p. 83).

The processual level included developing research findings that emphasised participants’ thoughts on beneficiaries’ participation in evaluation. However, the critical motivation moved the research beyond a discussion of findings. The aim was to both give beneficiaries a voice in the research project and, through listening to that voice, develop further processes capable of enabling beneficiaries’ voices to be heard beyond the research project. In this way, findings were used to enable praxis, or “reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it” (Freire, 2017, p. 25). Here the reflexive level of the research arises from the research praxis.

Reflexive

Reflexivity is considered an important issue within qualitative research (Hertz, 1996). At the individual researcher level, reflexivity includes the researcher’s self-awareness and consideration of assumptions they bring to the project (Woods et al., 2016). In the context of the case study research, the Conceptual and Processual Sections of this article have highlighted how this individual level of researcher reflexivity was achieved. However, through the methodology itself, an additional level of reflexivity was enabled – labelled here as methodological reflexivity.

Methodological reflexivity is conceived as a movement beyond researcher self-awareness or reflection, toward a reflective use of research findings to inform further methodological development. Within the case study research, methodological reflexivity was enabled through the development of beneficiary evaluation surveys for each organisation to use (see Kingston et al., 2020) for a more detailed presentation of these evaluation surveys). These surveys (or evaluative tools) were developed directly from the findings of the case studies and based on the voices of both beneficiaries and organisational staff and board members. In this way, the surveys enable the beneficiaries’ voices to continue to be heard, beyond the interview process. Two surveys were developed in response to the beneficiaries’ differing needs across the two TSOs. The difference in survey styles reflects the distinct ways the beneficiaries interact within their respective organisations.

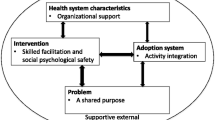

The beneficiaries’ reflections upon their current involvement, or lack thereof, in evaluation processes, their ideas for participative evaluation formats, questions, concerns, and insights enabled methodological reflexivity. The research findings were used to create avenues for further beneficiary participation, leading to the development of a more reflexive organisational environment. The methodological reflexivity of the research is represented within (Fig. 1)

As illustrated within (Fig. 1), the research methodology was designed to impact upon the broad research problem of addressing beneficiary marginality through creating platforms to hear beneficiary voice. Platforms for hearing beneficiary voice were enabled twofold: (1) within the research methodology and (2) within the organisation. By engaging in praxis, the researchers were able to reflect upon the case study findings and underlying theoretical assumptions within the critical methodology, to develop organisational practice-related evaluative tools. In essence, these evaluative tools are new instruments to be used within each case and as a reference for other organisations.

The research discussed in this article was strongly motivated to research with beneficiaries rather than on beneficiaries. At the outset of designing the research project, hearing beneficiaries’ voices was considered imperative toward understanding their perspectives on participating in evaluating TSOs. Through the unfolding of the research project the importance of not only hearing beneficiary voice, but also acting upon it was emphasised. In order to achieve any sort of benefit for the beneficiaries, their words needed to matter. This emphasis motivated the researchers to not only gain beneficiaries’ perspectives on participative evaluation, but to also develop the organisational evaluation tools to enable beneficiaries’ voices to continue being heard. Without this level of reflexivity, the research project may have concluded with a valid yet merely descriptive understanding of beneficiaries’ thoughts on evaluation. Although this may have contributed to extant literature, it would have done little to enable these beneficiaries’ evaluative voices to continue being heard within their TSOs. It should be noted that it is outside the scope of this research to explore the use of the evaluation tools within each organisation. However, soon after receiving the evaluation tool, the manager of one organisation commented that they were making use of it immediately. This suggests the TSO values the instrument developed from its beneficiaries, for its beneficiaries.

Contribution, Conclusion, and Limitations

The purpose of this article has been to reflect upon critical research methodology seeking to empower beneficiaries within TSOs. The presented methodological reflection involves three distinct methodological levels: conceptual, processual, and reflexive; resulting in methodological reflexivity and praxis.

As a contribution to critical Third Sector research internationally, other researchers exploring the construction and reduction of societal power asymmetries may benefit from considering methodology at conceptual, processual, and reflexive levels. Doing so may prompt researchers to be more ontologically, epistemologically, and methodologically sensitive and lead to the design of research projects that go beyond process, toward influencing social change. This supports underpinnings of critical theory, toward enhanced equality through organisational practices. Here beneficiary participative evaluation meets both practical and empowerment related rationales (Cousins & Whitmore, 2007).

In extending extant TSO literature considering research with beneficiaries, this research emphasises the importance of matching the motivation of the study to the underlying research assumptions. A research motivation seeking social change and enhanced equality corresponds to a critical ontology. Importantly, a critical motivation to include the voices of marginalised stakeholders involves a responsibility to consider how those voices can be heard in a way that provides for their safety and attempts to reduce power asymmetries. In this regard, matching the way beneficiaries engage within their TSOs to the interview location and style proved beneficial. Reflexively, the importance of the beneficiaries’ voices not only being heard but being considered and acted upon, helped to move the research beyond offering a single opportunity to the heard, toward the development of participative evaluation instruments capable of enabling beneficiary voice to be ongoingly heard within their respective TSOs. This offers potential for increased and more meaningful accountability to be directed toward beneficiaries, thereby contributing to the limited empirical research in this area (van Zyl et al., 2019).

However, the methodology presented is not without its limitations. Research involving groups with power asymmetries is difficult and eliminating power differentials and affects is questionable. Whilst embedding research of this nature into a critical paradigm does not eliminate power dynamics, it does attempt to bring them to the fore. In this way, critical research is able to engender a reflexive approach. Critically reflexive research can probe into power relations that construct the world in which we live, whilst also accepting that it cannot provide all the answers. Instead, research can continue to pose challenging questions in the pursuit of social justice, and shine a light on ontological, epistemological, and methodological assumptions that construct not only how we see, what we see, and why we see it, but also importantly who we see.

Additionally, it is important to recognise the onus upon TSOs to consider how to progress current operations in ways that involve beneficiaries within evaluation processes. Evaluation processes will have little impact upon enabling beneficiary voice at an organisational level without being utilised. Beneficiaries can be empowered within their TSOs through having their feedback heard, valued, and applied. The evaluation tools arising from this critical methodological research may enable a means for TSOs seeking to authentically listen to their beneficiaries, to do that. Whilst this level of organisational participation is beyond the scope of this research, researchers can continue to acknowledge the importance of hearing, listening to, and engaging with the voices of beneficiaries within Third Sector research, as a way of continuing to disrupt disempowering societal structures.

References

Alcoff, L. (1992). The problem of speaking for others. Cultural Critique, 20, 5–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/1354221

Awio, G., Northcott, D., & Lawrence, S. (2011). Social capital and accountability in grass-roots NGOs: The case of the Ugandan community-led HIV/AIDS initiative. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 24(1), 63–92. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571111098063

Babbie, E. R. (2015). The Practice of Social Research (14th edn.). US: Cengage Learning.

Benjamin, L. M. (2020). Bringing beneficiaries more centrally into nonprofit management education and research. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764020918662

Berryman, D. R. (2019). Ontology, epistemology, methodology, and methods: Information for librarian researchers. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 38(3), 271–279.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brinkmann, S. (2018). The Interview. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (5th edn.). Sage.

Catchpowle, L., & Smyth, S. (2016). Accounting and social movements: an exploration of critical accounting praxis. Accounting Forum, 40(3), 220–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2016.05.001

Chen, J., Dyball, M. C., & Harrison, G. (2019). Stakeholder salience and accountability mechanisms in not-for-profit service delivery organizations. Financial Accountability & Management, 36(1), 50–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12217

Chiapello, E. (2017). Critical accounting research and neoliberalism. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 43, 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2016.09.002

Chu, V., & Luke, B. (2018). NGO accountability to beneficiaries: examining participation in microenterprise development programs. Third Sector Review, 24(2), 77–104.

Connolly, C., & Hyndman, N. (2017). The donor–beneficiary charity accountability paradox: a tale of two stakeholders. Public Money & Management, 37(3), 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2017.1281629

Cordery, C., & Sim, D. (2018). Dominant stakeholders, activity and accountability discharge in the CSO sector. Financial Accountability & Management, 34(1), 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12144

Cousins, J. B., & Whitmore, E. (1998). Framing participatory evaluation. New directions for evaluation, 1998(80), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1114.

Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. Sage.

Cunliffe, A. L. (2008). Orientations to Social constructionism: relationally responsive social constructionism and its implications for knowledge and learning. Management Learning, 39(2), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507607087578

Denzin, N. K. (2001). The reflexive interview and a performative social science. Qualitative Research, 1(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100102

Ebrahim, A. (2003). Accountability in practice: mechanisms for NGOs. World Development, 31(5), 813–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00014-7

Ebrahim, A. (2016). The many faces of nonprofit accountability. In D. O. Renz & R. D. Herman (Eds.), The Jossey-Bass handbook of nonprofit leadership and management. Wiley.

Freire, P. (2017). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin Modern Classics.

Gendron, Y. (2018). On the elusive nature of critical (accounting) research. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 50, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2017.11.001

Greene, J. C. (1997). Participatory evaluation. In L. Mabry (Ed.), Evaluation and the post-modern dilemma (pp. 171–189). JAI Press.

Guba, E., Lincoln, Y. S. (1998). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin Y., S. Lincoln (Eds.), The landscape of qualitative research (3rd edn., pp. 195–220). SAGE.

Hertz, R. (1996). Introduction: ethics, reflexivity and voice. Qualitative Sociology, 19(1), 3–9.

Jacobs, A., & Wilford, R. (2010). Listen first: a pilot system for managing downward accountability in NGOs. Development in Practice, 20(7), 797–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2010.508113

Kennedy, D. (2019). The Inherently Contested Nature of Nongovernmental Accountability: The Case of HAP International. VOLUNATS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30(6), 1393–1405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00134-3

Kilby, P. (2006). Accountability for empowerment: dilemmas facing non-governmental organizations. World Development, 34(6), 951–963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.11.009

Kincheloe, J. L., McLaren, P. (2011). Rethinking critical theory and qualitative research. In K. Hayes, S. R. Steinberg, K. Tobin (Eds.), Key works in critical pedagogy (pp. 285–326). SensePublishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-397-6.

Kingston, K. L., Furneaux, C., de Zwaan, L., & Alderman, L. (2019). From monologic to dialogic: accountability of nonprofit organisations on beneficiaries’ terms. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 33(2), 447–471. https://doi.org/10.1108/aaaj-01-2019-3847

Kingston, K. L., Furneaux, C., de Zwaan, L., & Alderman, L. (2020). Avoiding the accountability ‘sham-ritual’: an agonistic approach to beneficiaries’ participation in evaluation within nonprofit organisations. Critical Perspectives on Accounting. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2020.102261

Kvale, S. (2008). Doing interviews. Sage.

Lather, P. (2013). Methodology-21: what do we do in the afterward? International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(6), 634–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788753

Laughlin, R. C. (1987). Accounting systems in organisational contexts: a case for critical theory. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 12(5), 479–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(87)90032-8

Martinez, D. E., & Cooper, D. J. (2020). Seeing Through the Logical Framework. VOLUNATS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 31(6), 1239–1253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00223-8

Mathison, S. (2018). Does evaluation contribute to the public good? Evaluation, 24(1), 113–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389017749278

Mercelis, F., Wellens, L., & Jegers, M. (2016). Beneficiary participation in non-governmental development organisations: a case study in Vietnam. The Journal of Development Studies, 52(10), 1446–1462. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2016.1166209

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis : A methods sourcebook (3rd edn.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Murtaza, N. (2012). Putting the Lasts First: The Case for Community-Focused and Peer-Managed NGO Accountability Mechanisms. VOLUNATS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 23(1), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-011-9181-9

Myers, M. D. (2009). Qualitative research in business & management. Sage.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods : Integrating theory and practice (4th edn.). SAGE Publications, Inc

Ponelis, S. R. (2015). Using interpretive qualitative case studies for exploratory research in doctoral studies: A case of information systems research in small and medium enterprises. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 10, 535–550. https://doi.org/10.28945/2339 .

Rexhepi, J., & Torres, C. A. (2011). Reimagining critical theory. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 32(5), 679–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2011.596363

Rose, J., & Johnson, C. W. (2020). Contextualizing reliability and validity in qualitative research: toward more rigorous and trustworthy qualitative social science in leisure research. Journal of Leisure Research, 51(4), 432–451.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2016). Research methods for business students (7th edn.). Pearson.

Schwandt, T. A., & Gates, E. F. (2018). Case study methodology. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (5th edn., pp. 341–358). SAGE.

Scotland, J. (2012). Exploring the philosophical underpinnings of research: relating ontology and epistemology to the methodology and methods of the scientific, interpretive, and critical research paradigms. English Language Teaching, 5(9), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n9p9.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-2004-22201

Stake, R. E. (2006). Multiple case study analysis. Guilford Press.

Sullivan, S. (2017). What’s ontology got to do with it? on nature and knowledge in a political ecology of the’green economy’. Journal of Political Ecology, 24(1), 217–242.

van Zyl, H., Claeyé, F., & Flambard, V. (2019). Money, people or mission? accountability in local and non-local NGOs. Third World Quarterly, 40(1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1535893.

Walsh, S. (2016). Obstacles to NGOs’ accountability to intended beneficiaries: the case of ActionAid. Development in Practice, 26(6), 706–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2016.1200537.

Wedeen, L. (2010). reflections on ethnographic work in political science. Annual Review of Political Science, 13(1), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.052706.123951

Wellens, L., & Jegers, M. (2016). From consultation to participation: the impact of beneficiaries on nonprofit organizations’ decision making and output. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 26(3), 295–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21191

Wellens, L., & Jegers, M. (2017). Beneficiaries’ participation in development organizations through local partners: a case study in Southern Africa. Development Policy Review, 35(S2), 196–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12279

Woods, M., Macklin, R., & Lewis, G. K. (2016). Researcher reflexivity: exploring the impacts of CAQDAS use. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 19(4), 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2015.1023964

Yang, C., & Northcott, D. (2019). Together we measure: Improving public service outcomes via the co-production of performance measurement. Public Money & Management, 39(4), 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2019.1592906

Yasmin, S., Ghafran, C., & Haslam, J. (2020). Centre-staging beneficiaries in charity accountability: insights from an Islamic post-secular perspective. Critical Perspectives on Accounting. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2020.102167

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank the Special Issue guest editors Paloma Raggo and Mirae Kim for their feedback and editing insights which have improved the quality of this paper. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive and very helpful reviews.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Queensland University of Technology (QUT), through the School of Accountancy’s Accelerate Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Kylie Kingston and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval and Consent

Research explored within this manuscript followed procedures in accordance with ethical standards including receiving informed consent from all research participants; Queensland University of Technology (QUT) Ethics Approval Number: 1700000820.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kingston, K.L., Luke, B., Furneaux, C. et al. A Reflection on Critical Methodology: Accountability and Beneficiary Participative Evaluation in Third Sector Research. Voluntas 33, 1148–1155 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00395-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00395-x