Abstract

This study compiles the main findings in the field of academic research on pure donation-based crowdfunding (DCF) soliciting monetary contributions for charitable causes. To this purpose, a systematic literature review is conducted, resulting in 92 scientific publications analyzed for the first time in this field of research. The prevailing thematic dimensions and research gaps are identified and discussed. The incipient literature on DCF, with a majority of publications from 2015 onward in the form of empirical articles using quantitative methodologies, focuses on antecedents related to individual donors, organizational promoters as main actors, and online channels and design-related features of campaigns as enablers. However, the effects of DCF on relevant stakeholders (particularly beneficiaries and society in general) remain largely obscure. Based on this analysis, an integrated conceptual framework on DCF is proposed to guide future research. This framework, susceptible of empirical evaluation, allows characterizing the DCF as a distinct and emerging type of philanthropic funding model based on specific and novel antecedents, actors, enablers and effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The umbrella phenomenon of crowdfunding (CF) emerges in the context relative to the funding of resources, goods and services in the new digital sphere. Belleflamme et al. (2014) define CF as an open call, essentially through the Internet, for the provision of financial resources, in the form of donations or in exchange for monetary or non-monetary rewards in order to support initiatives for specific purposes. CF campaigns consist of open online calls by promoters or fundraisers to contribute to a wide variety of causes with different objectives (e.g., technological, scientific, creative, business, cultural, artistic or social goals). Participation in CF campaigns, despite being mostly related to the contribution of monetary resources, is also possible by offering products or services in kind (De Buysere et al. 2012).

The development of Web 2.0 (i.e., tags, Really Simple Syndication (RSS), blogs, wikis, social networking sites (SNS), podcasts, among other Internet-based technologies and applications) is seen as a prerequisite to the significant growth of CF since it has facilitated larger levels of participation of the crowd (Gunes 2012; Kaplan and Haenlein 2010; Lee et al. 2008; O’Reilly 2005). Web 2.0 set up a suitable digital context where the development of CF campaigns was frequently channeled from new electronic spaces in the form of websites, e-portals, digital platforms, SNS, text messaging services or apps; and amplified through social media. Under the current Mobile Web—so-called Web 4.0—online access from increasingly convergent personal and portable devices like smartphones, tablets or laptops allows users to participate in CF campaigns not only through investing, lending, obtaining rewards or donating; but also through chatting, interacting and collaborating, anywhere and at any time.

CF is based on donation when funders donate to causes just for the sake of supporting them, without having any expectation for (material) compensation, also known as the pure donation model (Massolution 2012). In particular, pure donation-based crowdfunding (DCF) campaigns entail a request for contributions of monetary and/or non-monetary resources (e.g., time or expertise in the case of pro-bono services or volunteering) with no possibility of receiving material rewards, in contrast to other forms of donation crowdfunding where donors may receive material compensations.

DCF has attracted increasing scholarly attention over the last decade, as an alternative fundraising formula to attract support for a great variety of initiatives and, in particular, as a promising financing source for nonprofit organizations in their pursuit of public benefit causes. Within a global scenario of economic strains and pressing social challenges, promoters of DCF campaigns struggle for funds and societal support through the Internet. However, despite the fact that nonprofit crowdfunding projects are on average more successful than for-profit ones, only approximately 13–20% of overall crowdfunding projects are successfully funded (Forbes and Schaefer 2017; Belleflamme et al. 2013). In this context, the purpose of this research consists of providing a comprehensive map of the field of DCF for charitable causes—understood as initiatives for the public benefit or the common good-. In order to achieve that goal, first a systematic literature review is undertaken, and then a conceptual framework is proposed to better understand the emergent phenomenon of DCF. The focus of this research is on the pure DCF model (where material rewards do not exist, either financial or non-financial) as a new form of charitable or philanthropic giving by individuals. Furthermore, the focus is on monetary contributions, as opposed to other material resources (in-kind donations) or to non-material resources (such as volunteering time or pro-bono services).

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. The next two sections present the methodology of the systematic literature review conducted on DCF for charitable causes and its descriptive results. Then, the fourth section maps the antecedents, actors, enablers, and effects of DCF extracted from the review, together with a proposal for an integrated conceptual framework that paves the way for future analysis in this emerging field of research. The discussion of the results is subsequently presented in “Discussion and Conclusions” section, as well as the identification of a set of gaps that should be covered through future lines of research and main conclusions.

Methodology

A systematic literature review was conducted to obtain an overview of the prevailing themes and to analyze findings on the topic of DCF to date. The systematic review approach focuses on delimiting research question(s), applying clearly defined selection criteria in order to choose the target publications, and exhaustively analyzing the resulting contents, thus minimizing possible bias (Tranfield et al. 2003). Systematic reviews are useful to the extent that they allow for: (1) summarizing the existing evidence concerning a particular topic, (2) identifying gaps for further research, and (3) suggesting a new theoretical or conceptual framework within the concerned field of knowledge (Kitchenham 2004).

Regarding the research questions that guided the systematic review, they were delimited as follows:

-

1.

Why does DCF emerge? This question aims to identify the antecedents of DCF in the form of drivers and barriers that prompt/impede its emergence.

-

2.

Who are the actors involved in DCF? This question aims to identify the stakeholders interacting in the course of DCF campaigns mainly as promoters, donors and beneficiaries.

-

3.

How is DCF enabled? This question aims to detect the mechanisms used for deploying DCF.

-

4.

What is DCF for? This question aims to explore the effects of DCF on recipient organizations and target end-beneficiaries.

The systematic search of literature was conducted through ISI Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus, in order to screen the most complete databases of scientific documents published in indexed, peer-reviewed academic journals and collections of proceedings. For the sake of exhaustiveness, combinations of specific keywords in the fields of DCF and charitable causes were searched within the title, abstract and author-provided keywords (see Table 1). The target publications consisted of scientific, peer-reviewed, scholarly—both theoretical/conceptual and empirical—articles and proceedings, written in English, not limited by any time specifications, and within the Economics, Business, Finance, Management, Social Issues, Social Sciences, Communication, Technology, and Computer Science subject areas.

As a result, 6742 documents of potential interest were identified in the first place (Fig. 1). In the first phase of screening by title or abstract, duplicates were eliminated and only publications dealing directly or indirectly, totally or partially, with pure DCF for charitable causes specifically referred to monetary contributions were included. As a result, 506 potentially relevant and unduplicated documents were selected. In the second phase of screening, and after reviewing all three levels (title, abstract, and keywords), 160 relevant documents were extracted. After reviewing the full documents with particular attention to their methodological sections, 68 publications were discarded, as they were mostly related to DCF offering material rewards, thus falling outside the scope of the pure donation model.

The final sample of 92 publications was then subjected to a descriptive analysis, consisting of coding each of them by a number of preset variables and categories, such as the research approach employed, the prevailing research theme, or the level of analysis, among others (see Table 2).

Describing the Emerging Field of DCF for Charitable Causes

The analysis of the 92 selected publications shows that DCF for charitable causes is a very recently emerging field of research according to the distribution of publications over time, with a vast majority (66%) of the literature published from 2015 until mid-2017. As far as the geographical distribution of publications is concerned, authors’ origin can be traced back to 27 different countries. Nevertheless, the prevalence of the USA’s institutions is unquestionable, providing 45 (40%) over a total of 112 authors involved. Regarding the most prevalent research approach and methodology, it corresponds to empirical articles using quantitative methodologies (see Table 2 for summary details).

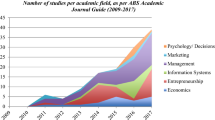

Regarding research themes, the vast majority of publications focus on specific aspects of DCF. Only nine publications explore DCF in the context of broader analyses on the phenomenon of CF, such as the ethical challenges of CF, or its effects on other fields such as finance, social innovation, or entrepreneurship. Within DCF-only publications, documents dealing with individual actors and technological features predominate, followed by those publications where the features of campaigns and promoters are central. Consistent with this, nearly half of the publications (42.4%) relate to the individual level of analysis. The organizational (28 papers) and institutional levels (16 papers) follow. Only nine publications take a multilevel approach, and seven of them combine analysis at the individual and organizational levels.

Regarding the type of channel employed, publications focused on online connection-based processes (i.e., those under computer and/or Internet-based network control) are the most prevalent in the literature reviewed. Aspects affecting both the online and offline processes (i.e., those that cannot be controlled by computer and/or the Internet) are featured in only 17% of the total. This category corresponds to publications aimed to identify and understand aspects underlying the donation process, regardless of the offline or online channels employed. As could be expected, none of the publications reviewed focuses on purely offline crowdfunding processes.

Mapping the Antecedents, Actors, Enablers and Effects of DCF for Charitable Causes

Why: Antecedents of DCF for Charitable Causes

The systematic literature review allowed for the identification of three perspectives on factors stimulating or hampering the emergence of DCF: (1) macro- or societal perspective, (2) meso- or organizational perspective, and (3) micro- or individual perspective.

Firstly, from a macro- or societal perspective, extant literature identifies three types of forces behind the recent development of DCF: (1) the levels of social capital and the size and dynamics of overall charitable sectors and their legal environment (institutional); (2) the levels of digital literacy (socio-technical); and (3) economic strains affecting public benefit areas and stimulating actors to pursue alternative funding models (financial).

Regarding social capital, those societies with a sense of social obligation to help others, where (in)tangible relations and resources are voluntarily allocated to charitable initiatives, provide a supportive environment for the success of DCF (Aprilia and Wibowo 2017; Kshetri 2015). Accordingly, drivers mainly respond to the maturity of charity marketplaces (Meer 2014, 2017; Budak and Rao 2016; Ghosh and Mahdian 2008), and their political, cultural, financial, and regulatory aspects (Bernardino and Santos 2016; Body and Breeze 2016; Bellio et al. 2015). Some authors proved the relation between other charitable mechanisms (i.e., matching grants), the existing dynamics (i.e., competition, efficiency), and the likelihood of a charitable campaign to succeed via DCF (Meer 2014, 2017; Budak and Rao 2016; Kshetri 2015). Furthermore, the need for public agencies to promote CF among social entrepreneurs was highlighted (Bernardino and Santos 2016).

Digital literacy and infrastructures were highlighted as the most relevant socio-technical factor acting both as a driver (presence of) and as a barrier (absence of). Social media literacy among potential users in particular (or beneficiaries in the case of medical DCF) results critical to ensuring campaign success and establishing deservingness (Berliner and Kenworthy 2017). The time lag between the moment a donation via text messaging is made, and the actual collection of money by the NPO (e.g., a 90-day lag) also emerges as a barrier (Bellio et al. 2015).

Finally, DCF has emerged in response to the effects of economic distress and public services commodification on both promoters (particularly nonprofits under financial strain searching for new income sources), and end-beneficiaries in need, especially in health care and social care. Berliner and Kenworthy (2017) contextualized the emergence of medical DCF campaigns in the USA in response to the austerity resulting from the 2008 global financial crisis, and anticipated a rise of this type of campaigns in the face of foreseeable cuts in public healthcare coverage under the Trump administration.

Secondly, from a meso- or organizational perspective, the existing literature identifies two DCF-specific drivers: (1) the area of public benefit activity that the promoter belongs to, and (2) the need by promoters to legitimate their online fundraising in order to reach out to new donors.

The area of activity of the promoter organization is a relevant driver when explaining the development of DCF for medical research (Choy and Schlagwein 2016; Dragojlovic and Lynd 2014). By contrast, other authors argue that the design and implementation of communication actions around DCF should transcend the particular cause to be supported, and instead convince potential donors to any type of charitable initiative about the convenience and security of online contributions in order to turn offline donors into online donors, with the associated costs savings (Treiblmaier and Pollach 2006). Additionally, Tanaka and Voida (2016) found that promoters’ need to convey the legitimacy of DFC campaigns could act as a driving force. Also, the need for online charities to reach out to younger audiences may foster DFC (Cockrell et al. 2016). Finally, the characteristic information asymmetry between nonprofits and potential donors can act in two different directions: as a barrier inhibiting DCF because of trust damage (Tremblay-Boire and Prakash 2017); and as an opportunity for organizations to demonstrate reliability through the promotion of DCF (Tremblay-Boire and Prakash 2017; Hsieh et al. 2011).

Thirdly, the micro-perspective was unfolded into the viewpoints of individual donors and of (target) end-beneficiaries. Regarding donors, a significant portion of the factors driving DCF substantially aligns with the broader literature on the drivers of individual giving, where eight basic mechanisms were identified (Bekkers and Wiepking 2011), and special attention was paid to the role of both (1) socio-demographic and (2) psychographic factors.

In the general giving literature, Neumayr and Handy (2017) found that education and income were significant predictors of donors’ decisions to give and of the amount donated when choosing among different charitable causes. Education, in particular, was proven to be positively related to the amount donated, since people attaining higher levels of education gave more compared to those with fewer years of education. Extant literature on DCF confirms donors’ age is a relevant antecedent of DCF. Cockrell et al. (2016) addressed the motivations of potential donors to contribute via crowdfunding, and found that younger respondents were the more likely to donate money via DCF websites in the future.

DCF literature also confirms the relevance of donor psychographic factors—individual values, motivations, lifestyles, and expectations—as antecedents. Ryu et al. (2016), for example, found a positive association between the wish to provide charitable assistance and the funding amounts, particularly in the earlier stages of donation. Consistent with the general literature, psychological rewards resulting from DCF donations in the form of warm glow (Gleasure and Feller 2016a), and sense of belonging to a community (Lacan and Desmet 2017; Choy and Schlagwein 2015; Ordanini et al. 2011) were confirmed as relevant drivers of this type of individual philanthropy.

Extant DCF literature likewise confirms that individual donors’ emotional skills and capacities may act as drivers, as suggested by the general literature on the importance of empathic concern and prosocial emotions for giving (Neumayr and Handy 2017). The authors highlight trustworthiness (Tremblay-Boire and Prakash 2017), pure altruism (Gleasure and Feller 2016a), high level of identification (Ordanini et al. 2011), and the psychological involvement with charities as relevant DCF drivers. According to the online experiment conducted by Cao and Jia (2017), participants with higher levels of psychological involvement with charities tended to have higher levels of concern for people in need.

However, DCF literature differs from general individual philanthropy literature to the extent that personal values, needs, and attitudes are mostly interpreted in the broader context of engagement with social media—web-based and mobile technologies to turn communication into an interactive dialogue—and belonging to physical/virtual communities (sociographics). Lacan and Desmet (2017) highlighted the central role of social utility and networking motivations for supporters within online communities. Choy and Schlagwein (2015) concluded that particular types of sociographic motivations as being part of a community, and/or showing social engagement, influence CF donations. Some authors argue DCF is a model whose funders are driven exclusively by social motivation (Castillo et al. 2014) and social participation (Ordanini et al. 2011). Donors’ own expectations are as important as those of third parties and communities’, since donors give what they think they are expected to give (Smith et al. 2015).

Chen and Givens (2013) found that a greater diversity of mobile phone use (e.g., send and receive emails or instant messages, access the Internet, play music or games, among others) increases the likelihood of mobile donation. In line with this, the influence of impulsiveness (Bennett 2009) was also highlighted. According to Mano (2014), the place of surfing also influences DCF. When users surf the Internet away from home or work, online donations increase; on the contrary, surfing at home or at work increases the volume of offline monetary contributions. The usage of social media also seems to be a good predictor of charitable giving intentions, particularly in emergency cases. In this regard, and due to the presence of a social media amplification effect, Korolov et al. (2016) evidenced that the use of Twitter can predict the volume of emergency relief donations in cases of natural disasters more accurately than conventional techniques. However, when there is no emergency to respond to, sociodemographics resulted more important to predict the intention to donate than the observed actions of peers.

As is the case with other types of individual giving, previous experiences in philanthropy and community engagement may also drive participation in DCF for charitable causes. Previous donation experience was proved a substantial element in trust-building to move potential donors to action (Tremblay-Boire and Prakash 2017). Althoff and Leskovec (2015) proved that successful donations in the past positively influence future donations, since donors experiencing success in their first DCF project, particularly in the case of small projects, are more likely to return. Reddick and Ponomariov (2013) found that online donations are a function of actual engagement in social groups (e.g., associations participation), rather than of frequent exposure to the internet and social media.

To finalize with antecedents related to donors, Neumayr and Handy (2017) found that, in general, being asked to donate was the determinant of individual giving with the highest explanatory capacity. By contrast, DCF literature has argued instead that most of the individual antecedents of DCF fall beyond the control of the campaign promoter to the extent that they refer to the psychographics and sociographics of donors; rather than to the existence of a call or asking.

Regarding the viewpoint of (potential) beneficiaries within the micro-perspective, the literature highlights that the reluctance of individuals to ask for money for themselves may hinder the development of DCF. In particular, individuals who may be the end-beneficiaries of DCF medical campaigns are hugely concerned on how the audience might judge them (Kim et al. 2017).

Who: The Actors of DCF for Charitable Causes

This crosscutting dimension encompasses the different parties interacting in the course of DCF campaigns, mainly those promoting them (and receiving the contributions in the first place), those donating to them, and those who may benefit from them in the end (directly or indirectly).

Since pure DCF targets public benefit causes in a very broad sense—from social ventures to scientific purposes or social care needs— the profile of individuals, groups, or organizations fostering them is accordingly diverse. However, most studies focus on traditional charities as promoters of DCF campaigns (Cao and Jia 2017; Body and Breeze 2016; Chung and Moriuchi 2016; Gleasure and Feller 2016a; Moqri and Bandyopadhyay 2016; Bellio et al. 2015; Ferguson et al. 2015; Lee et al. 2015; Steinemann et al. 2015; Castillo et al. 2014; Nogami 2014 ; Paulin et al. 2014a, b; Saxton and Wang 2014; Reinstein and Riener 2012 ; Smith et al. 2012 ; Ordanini et al. 2011; Ozdemir et al. 2010; Bennett 2005, 2009; Wojciechowski 2009 ; Eller 2008; Goecks et al. 2008).

Social entrepreneurs also emerge from our analysis as a distinct type of individual DCF promoter (Aprilia and Wibowo 2017; Bergamini et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2016; Meyskens and Bird 2015; Belleflamme et al. 2013). DCF campaigns promoted by individuals are the majority in the context of medical causes, where the patient, its relatives or friends, personally solicit contributions for individual medical treatments (Berliner and Kenworthy 2017; Kim et al. 2016b, 2017; Snyder et al. 2016; Farnel 2015; Burtch and Chan 2014). Beyond health care, individuals also promote DCF campaigns to ask for monetary assistance to cope with personal (e.g., funerals, education costs, and memorials) and collective causes (Ge et al. 2016; Gleasure and Feller 2016a; Kim et al. 2016a; Moqri and Bandyopadhyay 2016; Smith et al. 2015; Ordanini et al. 2011).

Other types of promoters that got lesser attention from the literature are the members of professional circles such as teachers (Meer 2014, 2017; Pak and Wash 2017; Althoff and Leskovec 2015; Wash 2013) or artists in the music industry (Ordanini et al. 2011); research units (Byrnes et al. 2014; Perlstein 2013); or hybrid arrangements as is the case with those campaigns promoted by the patients’ advocates (Dragojlovic and Lynd 2014) or resulting from the collaboration among businesses and charities through cause-related marketing activities (Choi and Kim 2016).

As regards donors, all the publications reviewed refer to individuals as the target donors of DCF. In relation to the end-beneficiaries of the campaigns, they mainly consist of individuals (e.g., individual patients, or individual promoters asking for contributions for their own personal needs), groups or population segments (e.g., vulnerable social groups, student or artist collectives), or society in general (as is the case when DCF campaigns aim at advancing medical research).

How: Enablers of DCF for Charitable Causes

DCF literature identifies a set of factors that may enable the successful deployment of DCF at three different levels: (1) the promoter’s capabilities, investments and transparency, (2) the online channel, and (3) the campaign.

From the perspective of the promoter, organizational capabilities enabling DCF mainly refer to its technological and social media literacy (Bergamini et al. 2017; Bernardino and Santos 2016; Saxton and Wang 2014; Bennett 2005) in terms of the capability to optimize its “web capacity” to move potential donors to action. More specifically, the capacity to integrate and coordinate offline and online connections stands out, as it may result in: (1) favoring the establishment of like-minded sense of community (Choy and Schlagwein 2016), (2) increasing the campaign persuasiveness and the ease of use of interfaces to encourage (early) donations (Solomon et al. 2015), and (3) applying appropriate marketing strategies and control mechanisms on, for instance, privacy of donors’ details (Sura et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2016) through the use of fourth-generation technologies (Bellio et al. 2015; Goecks et al. 2008). Not surprisingly, previous expertise of promoters in DCF campaigns (Pak and Wash 2017; Wash 2013) and in DCF platforms (Althoff and Leskovec 2015) is also useful in order to enable successful DCF.

Along this line of reasoning, long-term investments to build a social media profile (Dragojlovic and Lynd 2014) and the size of social networking (Mano 2014; Saxton and Wang 2014) also emerge as relevant enablers. Investment in “ask” activities and effective framing of causes—with the use of emotional donation messages—strengthen the position of promoters in the eyes of donors and may increase amounts raised (Body and Breeze 2016; Chung and Moriuchi 2016). Overall success rates of DCF projects are positively associated with promoters’ investment in innovative donation methods and in initiatives to increase engagement and empowerment of donors. In line with this, Lee et al. (2016) proposed that promoters adopt a new agent-based donation system that allows a more effective allocation of donations to campaigns by increasing alignment with donor preferences. On their part, Beltran et al. (2015) proposed that they empower donors by allowing them to specify conditions for their contributions—for instance, requiring peers to also contribute to the campaign or requiring the campaign to attract a critical mass of donors or contributions-.

Furthermore, the volume of details and information disclosed about promoters largely determines the extent of donors’ support. Due to the aforementioned information asymmetry between charities and (potential) donors, more information on promoters and their previous projects seems a key requisite for success in DCF, in comparison with other CF models (Polzin et al. 2017). Similarly, maximizing the credibility of promoters through efficient performance and transparency on funding uses, avoiding holding back, and increasing honest behaviors are key factors, especially when the campaign aims at health-related purposes such as funding particular medical treatments, or rare diseases research (Snyder et al. 2016; Hsieh et al. 2011). Other crucial enablers are the capacity to generate sympathy through the use of imagery to illustrate the causes (Body and Breeze 2016; Snyder et al. 2016); to fulfill planning and timing commitments (Dragojlovic and Lynd 2014); and to build an audience around the causes. Finally, understanding what stimulates the “Facebook generation” is pivotal for those organizations seeking to be successful in promoting DCF in the social media age (Fondevila Gascon et al. 2015; Byrnes et al. 2014; Saxton and Wang 2014).

Regarding the online channel(s) employed to foster, promote, and spread DCF campaigns for charitable causes, enablers mainly relate to: (1) the choice of channels and (2) the channel strategies. The most prevalent channels in the literature are social media (Bergamini et al. 2017; Berliner and Kenworthy 2017; Bernardino and Santos 2016; Korolov et al. 2015, 2016; Li and Wu 2016; Tan et al. 2016; Lee and Hsieh 2013); SNS (Aprilia and Wibowo 2017; Bergamini et al. 2017; Sura et al. 2017; Zhong and Lin 2017; Castillo et al. 2014; Ordanini et al. 2011); DCF digital platforms (Bergamini et al. 2017; Berliner and Kenworthy 2017; Flanigan 2017; Hossain and Oparaocha 2017; Kim and De Moor 2017; Bernardino and Santos 2016; Gleasure and Feller 2016b; Ryu and Kim 2016; Wang et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2016; Belleflamme et al. 2015; Ordanini et al. 2011); DCF sites (Budak and Rao 2016; Snyder et al. 2016; Beaulieu and Sarker 2015; Solomon et al. 2015; Pitt et al. 2002); donor-to-nonprofit (D2N) online marketplaces (Ozdemir et al. 2010); use of mobile devices (Choi and Kim 2016; Bellio et al. 2015; Chen and Givens 2013); and text messaging (Bellio et al. 2015; Chen and Givens 2013).

From a channel perspective, the Information Technology (IT) component of DCF may fulfill donors’ motivations that remain unattended, or unsatisfactorily met, by offline charity (Choy and Schlagwein 2016). The multi-role, intermediary functions of online channels must be managed to efficiently increase the amount of capital raised, identifying priorities, and facilitating social and technological interaction among parties involved. For instance, online dialogues based on Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) around charitable causes impact the decision-making process of potential donors (Lacan and Desmet 2017; Du and Li 2016). Social media such as blogs and SNS (namely Facebook and Twitter) were proved useful in humanizing DCF platforms and fostering the interaction between promoters and the community (Bernardino and Santos 2016).

The use of effective channel strategies (i.e., the display of donations from others, the inclusion of celebrity endorsements, paying careful attention to the website atmosphere) was also analyzed (Panic et al. 2016; Tan et al. 2016; Bennett 2005). In this sense, Sura et al. (2017) proved that Internet technology features significantly affect the people’s general attitude toward online donation, positively influencing their intention to donate via SNS. Ozdemir et al. (2010) conceptualized a D2N marketplace as an online intermediary that offers database services to donors and certification services to nonprofits. This element was found to allow NPOs to generate larger fundraising revenues online than offline.

Finally, enablers at the campaign level mainly refer to: (1) design capabilities and disclosures aimed to optimize effectiveness in terms of moving users into action, and transforming potential donors into de facto donors; and (2) values and beliefs underlying the appeal.

As regards the design-related capabilities, previous literature underlines the positive influence of wide reaching launch and powerful pitch (Fondevila Gascon et al. 2015); information on the campaign and its objectives (Polzin et al. 2017; Choy and Schlagwein 2016; Belleflamme et al. 2015); and usage of text and images as pictures and videos (Aprilia and Wibowo 2017; Kim et al. 2016a, b) in the form of storytelling or narrative self-presentation (better if based on longer word counts) on the likelihood of DCF to succeed. All these elements were proved to help potential donors to empathize with the target beneficiaries, maximizing their chances of contributing (Gleasure and Feller 2016a; Althoff and Leskovec 2015; Choy and Schlagwein 2015), and allowing them to feel as active members of a like-minded donor community (Choy and Schlagwein 2016).

In parallel, previous studies confirmed the critical role of disclosing campaign-specific information to increase the campaign perceived credibility, and to maximize its chances of success (Aprilia and Wibowo 2017; Berliner and Kenworthy 2017; Kim et al. 2016a, b). Additional factors increasing the perceived credibility of the campaigns consist of the use of appropriate language (e.g., words demonstrating precision and distinction) (Kim et al. 2016a); visualizing beneficiaries’ merits (Berliner and Kenworthy 2017; Kim et al. 2016b); information on external financial support and off-site verification (Kim et al. 2016b); disclosure of the beneficiary organizations (Hsieh et al. 2011); inclusion of personal comments (Choy and Schlagwein 2016; Du and Li 2016; Kim et al. 2016b; regular updates (Tremblay-Boire and Prakash 2017; Kim et al. 2016a, b; Fondevila Gascon et al. 2015); and communication of final funding uses (Tremblay-Boire and Prakash 2017; Choi and Kim 2016; Althoff and Leskovec 2015; Byrnes et al. 2014).

In addition, the type of values and beliefs to which the charitable campaign appeals can also affect the volume of contributions raised via online and offline. Mano (2014) revealed that online contributions prevail in the case of ideological-based campaigns, in comparison with faith-related ones that attract more offline donations. Other campaign factors enabling successful DCF relate to the capacity to be sharable and spreadable via online social media and networks, enlarging its potential effect (Snyder et al. 2016; Tanaka and Voida 2016; Choy and Schlagwein 2015; Mano 2014; Saxton and Wang 2014); the inclusion of emotional appeals (Kim et al. 2016a, b; Snyder et al. 2016); the visualization of others’ donations (Tan et al. 2016); the focus on small monetary goals (Cockrell et al. 2016); and a length under 40 days (Damgaard and Gravert 2017; Fondevila Gascon et al. 2015).

What For: Outcomes of DCF for Charitable Causes

Regarding the effects of DCF, a distinction should be made between the consequences for (1) the promoter organizations that receive the contributions, and (2) the outcomes for end-beneficiaries, be they direct or indirect (the latter including the communities around direct beneficiaries and society at large).

As regards the potential effects on promoter organizations, they relate to their increased perception as being trustworthy (Gras et al. 2017; Tremblay-Boire and Prakash 2017; Choy and Schlagwein 2016; Althoff and Leskovec 2015; Hsieh et al. 2011); the effects of conveying the legitimacy of the campaigns (Tanaka and Voida 2016); the possibility of learning from failed campaigns (Pak and Wash 2017); the increased control and knowledge on donors through the exploitation of 4G technologies (Bellio et al. 2015); and the growth of their social bases, transforming offline donors into online ones (Treiblmaier and Pollach 2006).

When it comes to mobile donations to DCF campaigns, positive effects on end-beneficiaries mainly consist of facilitating civic engagement by disadvantaged social groups, and overcoming age, race, and socioeconomic status gaps (Chen and Givens 2013). A second set of positive effects on end-beneficiaries relates to a broader access to both specialized healthcare services and advances in medical research (Berliner and Kenworthy 2017; Kim et al. 2017; Snyder et al. 2016; Burtch and Chan 2014; Dragojlovic and Lynd 2014; Mejova et al. 2014). Effects on indirect beneficiaries and on society at large refer to the creation of social value (Meyskens and Bird 2015) and to an increased awareness about the social causes that justify the donation, both among potential donors and society as a whole (Bergamini et al. 2017).

However, paradoxical effects emerge for end-beneficiaries specifically in contexts of insufficient health insurance coverage. DCF can reproduce and even aggravate the socioeconomic inequalities that it seeks to initially correct, as far as it may imperil entitlement to public benefits based on income and poverty levels, since the funds raised via DCF may qualify as income. In line with this, DCF platforms can further marginalize end-beneficiaries in poverty conditions by crowding out public health expenditures, while strengthening a hyper-individualized system of choosing who deserves, and who does not deserve, to receive assistance (Berliner and Kenworthy 2017; Dragojlovic and Lynd 2014).

A Proposal for a Conceptual Framework

The four thematic dimensions emerging from the analysis of extant literature, namely the antecedents, actors, enablers, and effects of DCF—captured, respectively, by the Why, Who, How, and What For questions—articulate the integrated conceptual model that is synthesized in Fig. 2. This conceptual framework identifies significant relationships between the antecedents, enablers, and effects of DCF. Antecedents of DCF at the micro-, meso-, and macro-levels of analysis may stimulate or condition DCF actors and enablers. Enablers, in turn, have a positive and direct impact on DFC effects. At the same time, DCF effects are indirectly influenced by antecedents.

Discussion and Conclusions

This paper presents a review of pure DCF soliciting monetary contributions for charitable causes. Based on the analysis of 92 scientific publications, this study contributes to the literature in a twofold way. Firstly, for the first time, it compiles and systematically analyzes the main findings in this emerging field of research. Secondly, it provides a conceptual framework to better understand the phenomenon of DCF.

The review of the literature shows pure DCF as an alternative fundraising formula to provide support through digital media to a wide range of common good causes (from social care to scientific or medical purposes, among others) in a context of financial and societal strains. Pure DCF is a very recent field of scholarship, broadly developed via empirical quantitative research. Its emergence is closely connected to digital transformation and the view of individuals as the main guarantors of societal well-being. Consistent with this, documents dealing with the drivers of individual donors and technological enablers predominate. Other enabling aspects related to the features of promoters, or the design and development of campaigns, are also explored to a significant extent.

Findings show that those antecedents driving or impeding the emergence of DCF take multiple forms, and operate at macro-, meso-, and micro-perspectives. Although most findings of DCF literature are consistent with the broader philanthropy literature, some distinct relationships (and also research gaps) emerge from our analysis. At the macro-perspective, structural factors of giving regimes such as social capital, or the legal and regulatory frameworks for fundraising (among other characteristics underlying institutional trust), were previously explored in the context of successful international and national charitable giving (Casale and Baumann 2015; van Leeuwen and Wiepking 2013). However, the limited presence of publications focused on the institutional dimension of DCF represents a first significant gap identified in this study.

At the meso-perspective, antecedents on the side of promoter organizations are in line with extant literature on the need for nonprofits to develop new processes and products in order to improve their effectiveness and, as result, increase the access to new targets in the context of transformative services (Sanzo-Perez et al. 2015). Furthermore, the role of information asymmetry between nonprofits and potential donors in inhibiting the intention of giving has also been analyzed in the context of toxic charity, especially when promoters provide charitable services abroad (Hou et al. 2017; van Leeuwen and Wiepking 2013; Bekkers and Wiepking 2011). However, the emphasis on DCF as a means to increase legitimacy on the virtual sphere, access to prospective donors who are digital natives, or transform offline donors into online, less costly ones, are distinct findings of DCF literature.

Similarly, previous studies on individual giving have shed light on the significant role of socio-demographic and psychographic characteristics in driving monetary contributions (Bekkers and Wiepking 2011; Bekkers 2010). However, two distinct DCF relationships emerge from the analysis: the pivotal role of sociographics—communities and social media—when it comes to explaining donor behavior, and the diminished importance of being asked by a promoter—as individual participation on DCF apparently depends on a constellation of specific socio-technical factors mostly beyond promoters’ control.

As regards enablers, they mostly relate to a set of digital resources, processes, and routines available for promoters to successfully develop and coordinate DCF campaigns. These campaigns, far from being once-only events—as traditional offline fundraising campaigns are—(Wiepking 2008), constitute permanent content to be accessed, shared, and commented through the online channels and strategies employed. In order to ensure that, DCF campaigns require specific design and development mechanisms and capabilities from both a technical perspective and a content perspective, useful enough to reflect those values and beliefs that activate the (emotional) appeal of the campaign among potential donors.

Successful DCF positively affects the performance of promoter organizations, with effects at two levels. At an internal level, benefits refer to trial-and-error learning from previous DCF campaigns and increased knowledge of donors thanks to the use of data analysis provided by fourth-generation technology-based devices. At an external level, they include strengthened reputation, legitimacy and reliability, and increased support. The role of end-beneficiaries in the DCF realm is residual, except in the case of medical campaigns where they usually play a dual role as beneficiaries and campaign promoters, with paradoxical effects. The outcomes of DCF for beneficiaries and society in general constitute the second significant gap that future lines of research should aim to balance, as far as they directly relate to DCF accountability. In particular, the weak presence of end-beneficiaries within DCF literature seems to be in consonance with broader findings in the nonprofit literature (Rey-Garcia et al. 2017).

Lastly, the third research gap is related to the scarce presence within the literature of multilevel analyses or empirical evidence from an integrated relationship model perspective. Further research is needed to provide insight into the potential connections between specific thematic dimensions (e.g., actors) and perspectives (e.g., macro). This would help to shed light on, for instance, which profiles of DCF actors are the most prominent in the promotion of DCF in countries with and without public welfare programs, among many other potential correlations. Aiming to cover this material gap, an integrative conceptual framework was proposed, thus paving the way for future research and guiding further empirical explorations.

References

Althoff, T., & Leskovec, J. (2015). Donor retention in online crowdfunding communities: A case study of DonorsChoose.org. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web (pp. 34–44).

Aprilia, L., & Wibowo, S. S. (2017). The impact of social capital on crowdfunding performance. South East Asian Journal of Management, 11(1), 44–57.

Beaulieu, T., & Sarker, S. (2015). A conceptual framework for understanding crowdfunding. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 37(1), 1–31.

Bekkers, R. (2010). Who gives what and when? A scenario study of intentions to give time and money. Social Science Research, 39(3), 369–381.

Bekkers, R., & Wiepking, P. (2011). A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: Eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(5), 924–973.

Belleflamme, P., Lambert, T., & Schwienbacher, A. (2013). Individual crowdfunding practices. Venture Capital, 15(4), 313–333.

Belleflamme, P., Lambert, T., & Schwienbacher, A. (2014). Crowdfunding: Tapping the right crowd. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(5), 585–609.

Belleflamme, P., Omrani, N., & Peitz, M. (2015). The economics of crowdfunding platforms. Information Economics and Policy, 33, 11–28.

Bellio, E., Buccoliero, L., & Fiorentini, G. (2015). Marketing and fundraising through mobile phones: New strategies for nonprofit organizations and charities. In Marca D., & van Sinderen M. (Eds.), ICE-B 2013—10th international conference on E-business, part of the ICETE 2013: 10th international joint conference on E-business and telecommunications.

Beltran, J. F., Siddique, A., Abouzied, A., & Chen, J. (2015). Codo: Fundraising with conditional donations. In UIST 2015—Proceedings of the 28th annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (pp. 213–222).

Bennett, R. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of website atmosphere in online charity fundraising situations. Journal of Website Promotion, 1(1), 131–152.

Bennett, R. (2009). Impulsive donation decisions during online browsing of charity websites. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 8(2–3), 116–134.

Bergamini, T. P., Navarro, C. L. C., & Hilliard, I. (2017). Is crowdfunding an appropriate financial model for social entrepreneurship? Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 23(1), 44–57.

Berliner, L. S., & Kenworthy, N. J. (2017). Producing a worthy illness: Personal crowdfunding amidst financial crisis. Social Science and Medicine, 187, 233–242.

Bernardino, S., & Santos, J. F. (2016). Financing social ventures by crowdfunding: The influence of entrepreneurs’ personality traits. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 17(3), 173–183.

Body, A., & Breeze, B. (2016). What are ``unpopular causes’ and how can they achieve fundraising success? International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 21(1), 57–70.

Budak, C., & Rao, J. M. (2016). Measuring the efficiency of charitable giving with content analysis and crowdsourcing. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Web and Social Media, ICWSM 2016 (pp. 32–41).

Burtch, G., & Chan, J. (2014). Reducing medical bankruptcy through crowdfunding: Evidence from give forward. In 35th International Conference on Information Systems “Building a Better World tThrough Information Systems”, ICIS 2014.

Byrnes, J. E. K., Ranganathan, J., Walker, B. L. E., & Faulkes, Z. (2014). To crowdfund research, scientists must build an audience for their work. PLoS ONE, 9(12), e110329.

Cao, X., & Jia, L. (2017). The effects of the facial expression of beneficiaries in charity appeals and psychological involvement on donation intentions: Evidence from an online experiment. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 27(4), 457–473.

Casale, D., & Baumann, A. (2015). Who gives to international causes? A sociodemographic analysis of U.S. donors. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44(1), 98–122.

Castillo, M., Petrie, R., & Wardell, C. (2014). Fundraising through online social networks: A field experiment on peer-to-peer solicitation. Journal of Public Economics, 114, 29–35.

Chen, W., & Givens, T. (2013). Mobile donation in America. Mobile Media and Communication, 1(2), 196–212.

Choi, B., & Kim, M. (2016). Donation via mobile applications: A study of the factors affecting mobile donation application use. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 32(12), 967–974.

Choy, K., & Schlagwein, D. (2015). It affordances and donor motivations in charitable crowdfunding: The “earthship kapita” case. In 23rd European conference on information systems, 2015 (May).

Choy, K., & Schlagwein, D. (2016). Crowdsourcing for a better world on the relation between IT affordances and donor motivations in charitable crowdfunding. Information Technology & People, 29(1, SI), 221–247.

Chung, C., & Moriuchi, E. (2016). The effectiveness of donation advertising: An experimental study for felt ethnicity and messages on in-groups and out-groups. In K. Kim (Ed.) Celebrating America’s Pastimes: Baseball, Hot Dogs, Apple Pie and Marketing? Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science (pp. 745–746). Cham:Springer.

Cockrell, S. R., Meyer, D. W., & Smith, A. D. (2016). Electronic intervention and platforms and their impacts on crowdfunding behavior. International Journal of Business Information Systems, 23(3), 263–286.

Damgaard, M. T., & Gravert, C. (2017). Now or never! The effect of deadlines on charitable giving: Evidence from two natural field experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 66, 78–87.

De Buysere, K., Gajda, O., Kleverlaan, R., & Marom, D. A. (2012). Framework for European crowdfunding. http://www.crowdfundingframework.eu.

De Oliveira, A. C. M., Croson, R. T. A., & Eckel, C. (2011). The giving type: Identifying donors. Journal of Public Economics, 95(5–6, SI), 428–435.

Dragojlovic, N., & Lynd, L. D. (2014). Crowdfunding drug development: The state of play in oncology and rare diseases. Drug Discovery Today, 19(11), 1775–1780.

Du, L., & Li, X. (2016). The influence of micro-charity online comments on the decision making of the donors. In Z. Yang (Ed.), Proceedings of 2016 China Marketing International Conference: Marketing theory and practice.

Eller, A. (2008). Solidarity.com: Is there a link between offline behavior and online donations? Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 11(5), 611–613.

Farnel, M. (2015). Kickstarting trans{*}: The crowdfunding of gender/sexual reassignment surgeries. New Media & Society, 17(2), 215–230.

Ferguson, R., Gutberg, J., Schattke, K., Paulin, M., & Jost, N. (2015). Self-determination theory, social media and charitable causes: An in-depth analysis of autonomous motivation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45(3), 298–307.

Flanigan, S. T. (2017). Crowdfunding and diaspora philanthropy: An integration of the literature and major concepts. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28(2), 492–509.

Fondevila Gascon, J. F., Rodriguez, J. R., Monforte, J. M., Lopez, E. S., & Masip, P. M. (2015). Crowdfunding as a formula for the financing of projects: An empirical analysis. Revista Cientifica Hermes, 14, 24–47.

Forbes, H., & Schaefer, D. (2017). Guidelines for successful crowdfunding. Procedia CIRP, 60, 398–403.

Ge, L., Guo, Z., & Luo, X. (2016). Intermediaries vs peer-to-peer: A study of lenders’ incentive on a donation-based crowdfunding platform. In AMCIS 2016: Surfing the IT innovation wave. Association for Information Systems.

Ghosh, A., & Mahdian, M. (2008). Charity auctions on social networks. In Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (pp. 1019–1028).

Gleasure, R., & Feller, J. (2016a). Does heart or head rule donor behaviors in charitable crowdfunding markets? International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 20(4), 499–524.

Gleasure, R., & Feller, J. (2016b). Emerging technologies and the democratization of financial services: A metatriangulation of crowdfunding research. Information and Organization, 26(4), 101–115.

Goecks, J., Voida, A., Voida, S., & Mynatt, E. D. (2008). Charitable technologies: Opportunities for collaborative computing in nonprofit fundraising. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (pp. 689–698).

Gras, D., Nason, R. S., Lerman, M., & Stellini, M. (2017). Going offline: Broadening crowdfunding research beyond the online context. Venture Capital, 19(3), 217–237.

Gunes, S. (2012). Wisdom of firms versus wisdom of crowds. International Journal of Business, Humanities & Technology, 2(3), 55–60.

Hossain, M., & Oparaocha, G. O. (2017). Crowdfunding: Motives, definitions, typology and ethical challenges. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 7(2), 1–14.

Hou, J., Zhang, C., & Allen, R. (2017). Understanding the dynamics of the individual donor’s trust damage in the philanthropic sector. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28, 648–671.

Hsieh, G., Hudson, S. E., & Kraut, R. E. (2011). Donate for credibility: How contribution incentives can improve credibility. In Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 3435–3438).

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68.

Kim, P. H., Buffart, M., & Croidieu, G. (2016a). TMI: Signaling credible claims in crowdfunding campaign narratives. Group and Organization Management, 41(6), 717–750.

Kim, J. G., Kong, H. K., Karahalios, K., Fu, W.-T., & Hong, H. (2016b). The power of collective endorsements: Credibility factors in medical crowdfunding campaigns. In 34th Annual CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 4538–4549).

Kim, H., & De Moor, L. (2017). The case of crowdfunding in financial inclusion: A survey. Strategic Change, 26(2), 193–212.

Kim, J. G., Vaccaro, K., Karahalios, K., & Hong, H. (2017). Not by money alone: Social support opportunities in medical crowdfunding campaigns. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 1997–2009.

Kitchenham, B. (2004). Procedures for performing systematic reviews. Keele University: UK 33(TR/SE-0401), 28.

Korolov, R., Peabody, J., Lavoie, A., Das, S., Magdon-Ismail, M., & Wallace, W. (2015). Actions are louder than words in social media. In S. F. Pei, & J. Tang (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (pp. 292–297).

Korolov, R., Peabody, J., Lavoie, A., Das, S., Magdon-Ismail, M., & Wallace, W. (2016). Predicting charitable donations using social media. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 6(1), 31, 1-10.

Kshetri, N. (2015). Success of crowd-based online technology in fundraising: An institutional perspective. Journal of International Management, 21(2), 100–116.

Lacan, C., & Desmet, P. (2017). Motivations for participation and e-WOM among supporters of crowdfunding campaigns. In A. Kavoura, D. Sakas, & P. Tomaras (Eds.), Strategic Innovative Marketing. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics (pp. 315–321). Cham: Springer.

Lee, S., Dewester, D., & Park, S. (2008). Web 2.0 and opportunities for small businesses. Service Business, 2(4), 335–345.

Lee, Y.-H., & Hsieh, G. (2013). Does slacktivism hurt activism? The effects of moral balancing and consistency in online activism. In Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 811–820).

Lee, U., Song, A., Lee, H.-I., & Ko, M. (2015). Every little helps: Understanding donor behavior in a crowdfunding platform for non-profits. In Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems—Proceedings, 18 (pp. 1103–1108).

Lee, Y.-C., Yen, C.-H., & Fu, W.-T. (2016). Improving donation distribution for crowdfunding: An agent-based model. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 9708, 3–12.

Li, Y.-M., & Wu, J.-D. (2016). A social recommendation mechanism for social fundraising. In Pacific Asia conference on information systems, PACIS 2016.

Mano, R. S. (2014). Social media, social causes, giving behavior and money contributions. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 287–293.

Massolution (2012). The Crowdfunding Industry Report: Market Trends, Composition and Crowdfunding Platforms. Crowdsourcing LLC.

Meer, J. (2014). Effects of the price of charitable giving: Evidence from an online crowdfunding platform. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 103, 113–124.

Meer, J. (2017). Does fundraising create new giving? Journal of Public Economics, 145, 82–93.

Mejova, Y., Weber, I., Garimella, V. R. K., & Dougal, M. C. (2014). Giving is caring: Understanding donation behavior through email. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (pp. 1297–1307).

Meyskens, M., & Bird, L. (2015). Crowdfunding and value creation. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 5(2), 155–166.

Moqri, M., & Bandyopadhyay, S. (2016). Please share! Online word of mouth and charitable crowdfunding. In AMCIS 2016: Surfing the IT innovation wave—22nd Americas conference on information systems.

Neumayr, M., & Handy, F. (2017). Charitable giving: What influences donors’ choice among different causes? VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30, 783–799.

Nogami, T. (2014). What makes disaster donors different from non-donors? Disaster Prevention and Management, 23(4), 484–492.

Ordanini, A., Miceli, L., Pizzetti, M., & Parasuraman, A. (2011). Crowdfunding: Transforming customers into investors through innovative service platforms. Journal of Service Management, 22(4), 443–470.

O’reilly, T. (2005). What is Web 2.0? design patterns and business models for the next generation of software. http://oreilly.com/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html.

Ozdemir, Z. D., Altinkemer, K., De, P., & Ozcelik, Y. (2010). Donor-to-nonprofit online marketplace: An economic analysis of the effects on fund-raising. Journal of Management Information Systems, 27(2), 213–242.

Pak, C., & Wash, R. (2017). The rich get richer? Limited learning in charitable giving on donorschoose.org. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Web and Social Media (pp. 172–181).

Panic, K., Hudders, L., & Cauberghe, V. (2016). Fundraising in an interactive online environment. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(2), 333–350.

Paulin, M., Ferguson, R. J., Jost, N., & Fallu, J.-M. (2014a). Motivating millennials to engage in charitable causes through social media. Journal of Service Management, 25(3), 334–348.

Paulin, M., Ferguson, R. J., Schattke, K., & Jost, N. (2014b). Millennials, social media, prosocial emotions, and charitable causes: The paradox of gender differences. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 26(4), 335–353.

Perlstein, E. O. (2013). Anatomy of the Crowd4Discovery crowdfunding campaign. Springer Plus, 2(1), 560.

Pitt, L., Keating, S., Bruwer, L., Murgolo-Poore, M., & De Bussy, N. (2002). Charitable donations as social exchange or agapic action on the internet: The case of hungersite.com. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 9(4), 47–61.

Polzin, F., Toxopeus, H., & Stam, E. (2017). The wisdom of the crowd in funding: Information heterogeneity and social networks of crowdfunders. Small Business Economics, 50(2), 251–273.

Reddick, C. G., & Ponomariov, B. (2013). The effect of individuals’ organization affiliation on their internet donations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 42(6), 1197–1223.

Reinstein, D., & Riener, G. (2012). Reputation and influence in charitable giving: An experiment. Theory and Decision, 72(2), 221–243.

Rey-Garcia, M., Liket, K. C., Alvarez-Gonzalez, L. I., & Maas, K. (2017). Back to basics. Revisiting the relevance of beneficiaries for evaluation and accountability in nonprofits. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 27(4), 493–511.

Ryu, S., & Kim, Y.-G. (2016). A typology of crowdfunding sponsors: Birds of a feather flock together? Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 16, 43–54.

Ryu, S., Kim, K., & Kim, Y.-G. (2016). Reward versus philanthropy motivation in crowdfunding behavior. In Pacific Asia conference on information systems.

Sanzo-Perez, M. J., Alvarez-Gonzalez, L. I., & Rey-Garcia, M. (2015). How to encourage social innovations: A resource-based approach. The Service Industries Journal, 35(7–8), 430–447.

Saxton, G. D., & Wang, L. (2014). The social network effect: The determinants of giving through social media. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(5), 850–868.

Smith, R. W., Faro, D., & Burson, K. A. (2012). More for the many: The influence of entitativity on charitable giving. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(5), 961–976.

Smith, S., Windmeijer, F., & Wright, E. (2015). Peer effects in charitable giving: Evidence from the (Running) field. Economic Journal, 125(585), 1053–1071.

Snyder, J., Mathers, A., & Crooks, V. A. (2016). Fund my treatment! A call for ethics-focused social science research into the use of crowdfunding for medical care. Social Science and Medicine, 169, 27–30.

Solomon, J., Ma, W., & Wash, R. (2015). Don’t wait! How timing affects coordination of crowdfunding donations. In CSCW 2015—Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (pp. 547–556).

Steinemann, S. T., Mekler, E. D., & Opwis, K. (2015). Increasing donating behavior through a game for change: The role of interactivity and appreciation. In CHI PLAY 2015—Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Symposium on Computer–human Interaction in play (pp. 319–330).

Sura, S., Ahn, J., & Lee, O. (2017). Factors influencing intention to donate via social network site (SNS): From Asian’s perspective. Telematics and Informatics, 34(1), 164–176.

Tan, X., Lu, Y., & Tan, Y. (2016). An examination of social comparison triggered by higher donation visibility over social media platforms. In 2016 international conference on information systems, ICIS 2016.

Tanaka, K. G., & Voida, A. (2016). Legitimacy work: Invisible work in philanthropic crowdfunding. In Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems—Proceedings (pp. 4550–4561).

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207–222.

Treiblmaier, H., & Pollach, I. (2006). A framework for measuring people’s intention to donate online. In PACIS 2006—10th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems: ICT and Innovation Economy (pp. 808–819).

Tremblay-Boire, J., & Prakash, A. (2017). Will you trust me? How individual American donors respond to informational signals regarding local and global humanitarian charities. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28(2), 646–672.

van Leeuwen, M. H. D., & Wiepking, P. (2013). National campaigns for charitable causes: A literature review. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 42(2), 219–240.

Wang, B., Lim, E. T. K., & Van Toorn, C. (2016). Gimme money! Designing digital entrepreneurial crowdfunding platforms for persuasion and its social implications. In Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, PACIS 2016—Proceedings (p. 377).

Wash, R. (2013). The value of completing crowdfunding projects. In ICWSM (13).

Wiepking, P. (2008). For the love of mankind. A sociological study on charitable giving (Ph.D. Dissertation). Faculty of Social Sciences, VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Wojciechowski, A. (2009). Models of charity donations and project funding in social networks. In Meersman R., Herrero P., & Dillon T. (Eds.), On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems: OTM 2009 Workshops. Vol. 5872 (pp. 454–463).

Yang, Y., Wang, H. J., & Wang, G. (2016). Understanding crowdfunding processes: A dynamic evaluation and simulation approach. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 17(1), 47–64.

Zhong, Z.-J., & Lin, S. (2017). The antecedents and consequences of charitable donation heterogeneity on social media. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 23(1), 1–11.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salido-Andres, N., Rey-Garcia, M., Alvarez-Gonzalez, L.I. et al. Mapping the Field of Donation-Based Crowdfunding for Charitable Causes: Systematic Review and Conceptual Framework. Voluntas 32, 288–302 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00213-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00213-w