Abstract

Public trust of nonprofits can augment social benefits of the nonprofit sector by enhancing engagement of the general population in the sector. This study analyzed cross sectional data collected from a random sample of Canadians (n = 3853) to test the effects of respondents’ perceptions of financial accountability, transparency, and familiarity of charitable nonprofits, along with the effects of trust in key institutions on their general trust in charitable nonprofits. Results show that each factor (except for trust in government institutions) has a significant effect on the level of trust respondents had in charitable nonprofits. The study helps advance our understanding of what contributes to trust in charitable nonprofits among Canadians and offers suggestions on how nonprofits can garner greater trust with the population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

NonprofitsFootnote 1 undertaking charitable activities rely on philanthropic support to achieve their missions, and this support is grounded on beliefs in an organization’s legitimacy and trustworthiness (Berman and Davidson 2003; Furneaux and Wymer 2015; Handy 2000; O’Neill 2009; Shier and Handy 2013). Hence, trust is critical to the charitable sector. While individual charities might not influence the perceptions of trust in the sector at large (Sargeant and Lee 2002), the potential is there. For example, recent scandals involving large, globally known charities (e.g., Oxfam’s sex scandal in Haiti) may have the potential to harm support for and perceptions of the sector overall (Carolei 2018; Brindle 2018; Rimington 2018). However, public’s trust in nonprofits is restorable (Bryce 2007), as seen in the case of the American Red Cross scandal involving funds raised for 9/11 (Sisco et al. 2010)

The notion that charities are a trusted set of organizations has traditionally been well-established. Hansmann (1980) first argued that the non-distribution constraint, which precludes distributing profits to stakeholders, makes nonprofits more likely to be trusted. Others have argued that the non-distribution constraint in and of itself does not guarantee that charities are trustworthy: surpluses could be used for higher salaries and privileges, or result in shirking of efficiencies (Handy 2000). However, over the years, many polls have found that people trust charities (Charities Aid Foundation 2018; Independent Sector 2016; Lasby and Barr 2013; Rutley and Stephens 2017), although the overall level of trust varies both across countries and over time. Importantly, the public is also likely to trust nonprofits more than other institutions such as for-profits or government organizations (O’Neill 2009) and this is recognized as a competitive advantage that nonprofits have over other sectors (Handy 1997). Indeed this trend is likely to continue given a recent global survey particularly in the US and UK (Ries et al. 2018). Finally, the empirical evidence of the increasing philanthropic resources that charities garner year after year from private sources suggests that, at the very least, the donating public do trust the charities to which they freely give their money and/or time (Turcotte 2015; Giving USA 2017). In the face of this evidence, a fundamental question arises: what factors influence the perception of trust in charities?

As questions regarding nonprofit spending, oversight, and effectiveness arise periodically, it is important to understand what factors constitute the perception of trust. For example, is being honest in financial transactions a sufficient condition to establish trust? What about giving donors full information about how their donations are spent? Or, perhaps, is it the judicious use of resources or experience with charities that contributes to trust?

In this research, we examine trust and the factors that constitute trust in Canadian charities. Canada provides an interesting case to explore the topic of trust in its nonprofit sector for two reasons. First, the sector is a substantial component of the Canadian economy. This sector constitutes an estimated 185,000 charities and nonprofits—equally divided between registered charities and nonprofits—and employs 13% of the total Canadian labor force while adding more than 8% to Canada’s GDP (Emmett and Emmett 2015). It is also the second-largest (behind the Netherlands) per capita nonprofit sector in the world when expressed in terms of the economically active population (Hall et al. 2005).

Second, although the Canadian charitable sector derives a substantial amount of its revenue from government transfers, the trend data suggests declining governmental support since the 1990s due to policies that aim to reduce government debt (Emmett and Emmett 2015). In effect, many charities had to adjust to funding reductions (Hall et al. 2005), which were further exacerbated by the economic downturn in 2008. Charities made up for the lost funding by generating revenues in multiple ways, relying on volunteer staff, and increasing fundraising efforts (Cave 2016). A successful shift from public to private resources implies that there existed some level of trust, a precondition for attracting private resources—of both time and money—on a voluntary basis. It must also be said that government transfers to the nonprofit sector are also predicated in public trust, as democratic governments would not easily transfer large sums of money to charities that the public did not trust. Hence, trust in Canadian charities is an important factor influencing the charitable sector’s existence and persistence. It is relevant and would be helpful to explore the determinants of trust in the Canadian charitable sector considering its non-trivial size and its changing funding dynamics.

The trustworthiness of Canadian charitable sector has also been the subject of public debate and increasing scrutiny, resulting in demands for ceilings on nonprofit executive salaries (Imagine Canada 2010), removing the charitable tax deduction (Coyne 2017), and developing charity watchdogs to separate “good” charities from “bad” (Donovan 2007). This makes ‘trust’ a salient issue for Canadian charities and the Canadian public.

We examine what influences Canadians’ trust in their charities. In particular, we ask if attributes like “accountability” and “transparency,” which were previously identified in the literature, associate with trust. We also examine if knowledge of the sector through experiences, i.e., “familiarity” is associated with trust. In addition, we examine if trust in the nonprofit sector is influenced by broader issues of trust such as trust in public institutions or trust in other people (Grønbjerg 2009; Light 2008).

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows: We discuss the extant literature on trust and its theoretical underpinnings for charities followed by a discussion of the attributes of trust based on findings by other scholars. We offer hypotheses for testing the association of these attributes with Canadians’ trust in their charities. The next section outlines our methods and the use of a nationally representative sample to explore the importance of several factors—institutional trust, perceptions of sector transparency and accountability, and familiarity with charities—in influencing trust of the Canadian nonprofit sector. This is followed by a discussion of our findings and implications. The last section presents our concluding thoughts.

Literature Review

Trust

Much of the literature exploring trust within the nonprofit sector is theoretically rooted in the principal-agent dilemma, a situation where one party (the principal) engages another party (the agent) to “perform some service on their behalf which involves delegating some decision-making authority to the agent” (Jensen and Meckling 1976, p. 308). Because information available to each party is not the same, trust issues can emerge as the principal often relies on the agent to make decisions that further the goals of the principal. However, in most cases, the goals of the principal and the agent are not aligned, giving rise to the principal-agent problem. For example, the nonprofit, which is the agent of the donor (the principal), must undertake efforts often unobserved by the donor in disbursing the donated funds, and since the agent’s efforts are not easily visible to the donor, the nonprofit can misuse the funds toward other goals including perquisites to the benefit of the agent (McDougle and Handy 2014; Sloan 2009). There are also asymmetrical information problems between charities and their clients since the quality of goods and services provided by charities may be hard for clients to judge (e.g., evaluating daycare services without direct parental monitoring).

Hansmann (1980) highlights the sector’s non-distribution constraint as key to maintaining trust of the sector in the face of the principal-agent problem and information asymmetries. In contrast to institutions like businesses, charities (agents) are legally precluded from distributing profits to stakeholders, greatly reducing the motivation to cut corners or deceive principals (i.e., donors, clients, government). Although this non-distribution constraint may mitigate some of the problems outlined, it cannot completely erase the problems. Thus, principals must rely on the charity’s goodwill and trustworthiness to deliver promised societal benefits (Coleman 1990; Salamon 2012).

This reliance between the nonprofit sector and its various principals have been conceptualized both as trust (Handy et al. 2010; Salamon 2012) and confidence (Bekkers and Bowman 2009; Bowman 2004; McDougle 2014; O’Neill 2009), although some scholars draw strong distinctions between the two. Gaskin (1999), for example, argues that trust encompasses deeper personal engagement and increased vulnerability than confidence. Sargeant and Lee (2002) also distinguish ‘confidence’ from ‘trust,’ writing that the ‘confidence’ stems from knowledge (or, familiarity, in this study) and predictability, while ‘trust’ exists without confidence. Using this definition, knowledge (familiarity) is a critical factor in differentiating between trust and confidence. While this distinction is a useful frame for considering whether trust and confidence are truly separate concepts or exist on a spectrum, the vast number of studies using the terms interchangeably suggests that a relatively broad definition of trust is necessary for our purposes. To this end, we utilize Bourassa and Stang’s (2016) definition of trust: “the belief that an organization/sector and its people will never take advantage of stakeholder vulnerabilities by being fair, reliable, competent, and ethical” (p. 15).

Of course, trust in nonprofits does not exist within a vacuum; it must be contextualized within broader social and institutional trust. General social trust (Putnam 2000) is often understood as trust in strangers or a broadly trusting attitude toward other people. Institutional trust—trust in community organizations (Hager and Hedberg 2016) as well as businesses—is also part of general social trust and can encompass confidence. Although the nonprofit sector is not solely able to address issues that weaken general social and institutional trust, trust in the sector is undoubtedly influenced by both of these broader forms of trust (Bekkers 2003).

Opinion polls and various studies suggest diminishing levels of overall institutional trust both in America (Newport 2017; Nye et al. 1997; O’Neill 2009; Ries et al. 2018) and the U.K. (Hyndman and McConville 2016; Sargeant and Lee 2004), which have been accompanied by concerns of a similar “crisis of confidence” with charitable institutions (Brindle 2018; Herzlinger 1996; Hillier 2018; Light 2008; Rimington 2018; Salamon 2012). Despite these claims of a crisis, there is conflicting evidence regarding how changes in broader institutional and social trust affect the public trust in charities. For example, Grønbjerg (2009) found that among five different types of institutions (charities, businesses, local government, state government, and the federal government) charities demonstrated both the highest levels of trust and lowest levels of distrust. However, Grønbjerg (2009) found that individuals with high levels of trust in one institution rarely demonstrated low levels of trust in any of the other four, suggesting that individuals who are trusting of any institution are more trusting of institutions overall.

One argument suggests that the sector’s unique characteristics (e.g., voluntary nature of support and the inability to distribute profits to shareholders) lead people to identify these organizations as inherently more trustworthy than their governmental and for-profit counterparts (Frumkin 2002; Hansmann 1996). These claims are supported, in part, by research demonstrating that general trust in institutions does not influence charitable giving (Hager and Hedberg 2016) and that the level of nonprofit trust is stable over time when compared to other forms of institutions (O’Neill 2009).

Lastly, beyond institutional trust, extant literature has identified several demographic characteristics that influence trust of nonprofits. Grønbjerg (2009) found that individuals in higher social status categories related to race, education, and household income are more likely to trust charities than their counterparts with lower social status categories. Similar findings have been reiterated in other studies among racial minorities (Keirouz 1998; Wilson and Hegarty 1997) and with regards to both income (McDougle 2014; Schlesinger et al. 2004) and educational attainment (Keirouz 1998; Schlesinger et al. 2004). There are, however, no consistent findings regarding the influence of gender, age, political party, or religious affiliation on trust (Grønbjerg 2009; Light 2008).

Accountability and Transparency

Several studies have demonstrated the importance of accountability on influencing trust, although its effect is often mitigated by transparency. For example, Sloan (2009) found that unknown accountability ratings—whether positive or negative—did not influence donor support (arguably a signal of trust), suggesting that watchdog organizations must increase both general usability (Cnaan et al. 2011) as well as visibility (transparency) of ratings in order to influence accountability and trust. Similarly, Bekkers (2003), who examined the Dutch formal accreditation system, found that: “knowing that an accreditation seal exists does not automatically make people’s opinions with regard to charitable causes more positive” (p. 605). However, Bekkers (2003) does not dismiss the importance of accountability systems in meaningfully enhancing trust, although he argues that additional transparency in the form of “more media efforts, higher standards and more legal instruments” (p. 612) would be necessary to enhance trust.

Accountability is broadly understood to be a necessary component in promoting trust of the nonprofit sector for two reasons. First, the sector has low barriers to entry, making it easy for unethical entrepreneurs to enter the market. Second, donors (and other external stakeholders) often have no easy or costless mechanism by which to distinguish between trustworthy and untrustworthy organizations (Prakash and Gugerty 2010). Thus, charities that have good systems in place to be accountable to the public signal their trustworthiness to the broader public.

Despite the importance of “accountability” for the sector, there exists no simple definition of the term with respect to charities. Accountability is often conceptualized as responsibility to an outside entity; for example, Edwards and Hulme (1996) define accountability as “the means by which individuals and organizations report to a recognized authority (or authorities) and are held responsible for their actions” (p. 967). This emphasis on external authority and responsibility often focuses primarily on an organization’s finances, fundraising practices, and governance (Sloan 2009). In contrast, Cornwall et al. (2000) argue that accountability should not be wholly focused on external bodies: Taking responsibility for oneself is equally as important as being held responsible by another party. Both Kearns (1994) and Schmitz et al. (2011) offer a more inclusive definition, arguing that accountability is a multidimensional concept that encompasses not only the reporting of financial information but also the facets of performance evaluation, stakeholder engagement, and internal commitment to the organization’s mission.

Furthermore, accountability requires an understanding of the parties to whom the organization is primarily accountable (Dumont 2013). Charities interact with multiple stakeholders—funders (donors as well as government grantors and corporate sponsors), service recipients, staff and volunteers, including board members—all of whom have unique expectations of the organization. To this end, Ebrahim (2005) articulates three types of nonprofit accountability: “upward” accountability toward donors, “downward” accountability to service recipients, and “internal” accountability to the organization’s mission. In response to the challenges of balancing the needs and expectations of so many stakeholders, Williams and Taylor (2013) advocate the use of a Holistic Accountability Framework, which attempts to “[specify] the complex combination of accountability requirements to each stakeholder,” requiring organization leadership to “understand the system relationships” (p. 575). While such an approach would certainly be ideal, it is unlikely to be feasible for anyone but the largest charities, and even they may not successfully incorporate all stakeholders.

The competing demands of multiple stakeholders shape how organizations approach accountability, with most charities prioritizing upward accountability, a focus that makes sense given that many organizations’ survival is dependent on resources from external funders (Cooley and Ron 2002). Charities demonstrate accountability (in the form of annual reports and financial statements) to alleviate information asymmetry that threatens trust between external stakeholders—namely funders—and the organization (Ebrahim 2003). Despite these actions, donors may still question the charitable sector’s trustworthiness; as Tremblay-Boire and Prakash (2014) point out:

The proliferation of nonprofit accountability mechanisms such as charity rating organizations, voluntary programs, and website disclosures suggests that nonprofits and their stakeholders recognize that claims about trusting nonprofits do not sufficiently persuade stakeholders of the quality of nonprofits’ products, governance, policies, and procedures. (p. 699)

While accountability might be broadly defined as fulfillment of requirements (Bourassa and Stang 2016), transparency can be understood as the voluntary disclosure of information, including program performance (Schatteman 2013), financial data (Keating and Frumkin 2003), and governance (Hale 2013). Transparency’s role in influencing trust of the nonprofit sector is rarely discussed without including accountability, a consequence of the two concepts being so closely related. In fact, both Koppell (2005) and Ebrahim and Weisband (2007) discuss transparency as a component of accountability rather than its own individual concept. In particular, Koppell (2005) conceptualizes transparency as “the literal value of accountability,” underscoring transparency’s role in assessing organizational performance as foundational to all other forms of accountability (p. 96). Implicit in the concept of transparency is the relative ease of accessing various forms of information, including fundraising costs, donation use, and regulation compliance (Hyndman and McConville 2016).

Familiarity

Extant research has identified familiarity with charitable organizations as a critical factor of trust in the sector. Familiarity can range from general awareness of charities in the community to more involved experiences such as volunteering and donating. Familiarity in the form of general awareness is usually operationalized as the ability to identify charities within a given community. This awareness of the local charitable sector has a demonstrated influence on trusting charities. Kissane’s (2003, 2010) qualitative work found that individuals in communities with fewer charities were more likely to hold negative attitudes toward the charitable sector, while McDougle and Lam (2014) identified strong and positive connections between density, awareness, and trust. Saxton (2004) argues for a more nuanced approach to understanding familiarity, arguing that trust may be influenced more by the general public’s (lack of) understanding of charities’ operations rather than simply the ability to identify charitable organizations. Existing literature supports this argument, with several studies finding that trust is strongly and positively influenced by knowledge and understanding of nonprofit roles, activities, and operations (Bekkers 2003; Bourassa and Stang 2016; Schlesinger et al. 2004). Sargeant and Lee (2002), however, found no evidence that familiarity impacted trust of the nonprofit sector.

The relationship between familiarity and trust in charities becomes even more complicated when considering individuals’ relative inability to distinguish between nonprofit, for-profit, and public entities (Handy et al. 2010; McDougle 2014; Schlesinger et al. 2004). This issue is driven by several factors: “mission vagueness” of charities that results from delivering similar services as public and for-profit firms (Weisbrod 1998, p. 289); adoption of methods needed to compete with for-profit firms (Clarke and Carroll 2016; Gaskin 1999; Kramer 2000); and increased contracting of charities with government (DiMaggio and Anheier 1990; Smith and Lipsky 1993), all of which may undermine public trust of charitable organizations (Schlesinger et al. 2004). McDougle and Lam (2014) found that the ability to distinguish charities from other types of organizations was a driving factor in more favorable attitudes toward the nonprofit sector.

Beyond general familiarity, several studies have explored whether and how the level of familiarity in the form of direct involvement with the charitable sector (as a donor or a volunteer) is related to trust, but findings have not been consistent about the presence, strength, or direction of the relationship. For example, Bowman (2004) initially found that volunteers were more likely to express confidence in charitable organizations, but later studies found no relationship after controlling for generalized social trust (Bekkers and Bowman 2009). Similarly, Handy et al. (2010) found no relationship between direct involvement with charities (either in the form of donating or volunteering) and trust in charities. In contrast, Grønbjerg et al. (2016) did identify a relationship between familiarity and trust of charities, although their study drew from a sample of local government officials rather than a more general population. Finally, several other studies (Burnett 1992; Sargeant 1999; Saxton 1995) that explore the relationship between trust and familiarity argue that trust is a prerequisite for individuals to become more involved and familiar with the sector rather than “direct” familiarity enriching trust.

Due to the mixed findings in the literature we examine volunteering and donating as separate items. Although both activities are philanthrophic in nature, they differ in the nature of the individual’s involvement, and hence may associate differently with trust.

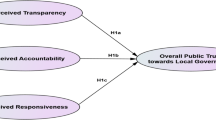

Based on the literature reviewed, we developed the following three sets of hypotheses. The first set of hypotheses tests the relationship between overall institutional trust and trust of the charitable sector; here we posit that general trust in charities will be higher than other institutions due to their non-distribution constraint on the surplus. Furthermore, we hypothesize that greater trust in for-profits or the government will be associated with higher levels of trust in the charitable sector. Additionally, greater trust in community leaders, which may include charities and other civil society organizations, will be associated with higher levels of trust in charities.

The next set of hypotheses first relates the perceived need for accountability in charities with the level of trust in charities. Here, we suggest that a higher need for accountability is more likely to be associated with lower trust in charities, as charities may be deemed less accountable than desired. Next, with respect to the perceptions on existing transparency levels in charities, we hypothesize that there is a positive association between higher levels of transparency and higher levels of trust in charities if charities are judged to be as transparent as desired.

The final group of hypotheses explore the role of familiarity in influencing trust. General familiarity will be associated with increased trust in charities, as discussed above. However, donating and volunteering are different behaviors with differing requirements of trust. In the first case, we posit that since most donations are undertaken at-arms length, donating requires donors to believe the specific charity is trustworthy, and this trust may diffuse to charities in general. On the other hand, volunteering, the donation of time, does not require the same level of trust as monetary donations as it is frequently undertaken in person. Volunteers are well-positioned to directly see the outcome of their volunteering, thus removing the perquisite of trust. Hence, volunteering for charities, while making the volunteer more familiar with charities, may also be associated with perceptions of trustworthiness in all charities.

The hypotheses are as follows:

Institutional Trust

H 1a

Charities will be perceived to be more trustworthy than for-profits or government organizations.

H 1b

Higher levels of trust in for-profits or government will be associated with increased trust in charitable sector.

H 1c

Higher levels of trust in community leaders will be associated with increased trust in the charitable sector.

Accountability and Transparency

H 2a

Higher demands for accountability will be associated with lower the levels of trust in charities.

H 2b

Higher perceptions of transparency will be associated with higher levels of trust in charities.

Familiarity

H 3a

Higher levels of general familiarity of charities will be associated with higher levels of trust in charities.

H 3b

Donating to charities will be associated with higher levels of trust in charities.

H 3c

Volunteering at charities will be associated with higher levels of trust in charities.

Literature suggests that perceived accountability and direct familiarity (through efforts of volunteering time and donating money) do not influence whether people find the charitable sector trustworthy. However, we maintain them in our model given that little research exists specifically about trust in charities in the Canadian context. As a result, this research highlights similarities or differences between the Canadian context and other sites of the current scholarly literature (such as in the United Kingdom, the United States, Netherlands, and Australia, where much of the extant literature is based, and all of which share a similar liberal welfare state history as Canada). It also contributes to the literature by investigating transparency and accountability as two separate constructs in understanding perceptions of the charitable sector.

Methods

This research analyzed secondary data collected by the Muttart Foundation among a simple random sample of Canadians (Lasby and Barr 2015).Footnote 2 A large survey questionnaire was developed, which focused on trust in charities and other institutions, accountability, familiarity, transparency, the role of charities, along with respondents’ direct involvement with charities and demographic characteristics.

Using Random Digit Dialing, Canadians residing in each of the ten provinces were interviewed by telephone for a total of 3853 respondents. The sample was designed to include English and French speaking Canadians 18 years of age or older. The sample across provinces was disproportionate; however, to arrive at a distribution that would represent a simple random sample of Canadian households, the sample used was corrected using weights based on the population estimates of each province. Those provinces that were over-represented were weighted less and those that were under-represented were weighted more.

Variables

Based on the various survey questions included in the Muttart Foundation’s comprehensive survey, we constructed several latent constructs assessing trust in charities, trust in other institutions (such as government, business, and community leaders), and perceptions of accountability, transparency, and familiarity with charities.

The dependent variable assessed in this study was the degree of self-reported trust in charities among study respondents. The latent construct was created from 12 items rated on a four-point Likert-type scale with response categories of not at all, a little, some, and a lot. Questions asked respondents about their general trust in charities (i.e., Thinking about charities in general, would you say you trust them…), along with trust in charities that participate in the following eleven types: environment, animals, health prevention and health research, social services, international development, children and children’s activities, education, the arts, hospitals, churches and places of worship and other religious organizations).

The internal consistency of the items was assessed to determine the reliability of this measure. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.86. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was undertaken to assess the construct validity of this variable utilizing the MPlus statistical software package (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012). The model fit indices were as follows: χ2 = 472.630, df = 49, p = 0.0000; TLI = 0.959; CFI = 0.969; RMSEA = 0.047. The results of the CFA show sufficient construct validity of this 12-item measure of extent of trust in charities (Kline 2011).

The independent variables in this analysis included respondents’ trust in the government, business, and community leaders, and their perceptions of accountability, familiarity, and transparency of charities and demographic characteristics of the study sample.

For trust in the government, business, and community leaders, three variables were constructed from general statements about how trust related to each of the institutional classifications. Items were measured on a four-point Likert-type scale with response categories of not at all, a little, some, and a lot. Following the same method utilized in constructing the dependent variable from existing survey items, trust in government was operationalized through the creation of a latent construct comprised of three items [How much trust do you have in… (a) The federal government; (b) The provincial government; and (c) The local government]. Trust in business was operationalized through the creation of a latent construct comprised of three items [How much trust do you have in… (a) Major corporations; (b) Small businesses; and (c) People who are business leaders]. Trust in community leaders was operationalized through the creation of a latent construct comprised of seven items [How much trust do you have in… (a) People who are medical doctors; (b) People who are lawyers; (c) People who are religious leaders; (d) People who are nurses; (e) People who are journalists and reporters; (f) People who are leaders of charities; and (g) People who are union leaders].

The internal consistency of the items was assessed for each variable to determine the reliability of the measures. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for Trust in Government was 0.78, Trust in Business was 0.59 (which is low, but kept in the model to maintain the differentiation in institutional types), and Trust in Community Leaders was 0.72. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was undertaken to assess the construct validity of each of these variables utilizing the MPlus statistical software package (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012). The model fit indices for Trust in Business and Trust in Government are just identified models (where there are no degrees of freedom left over), so we are unable to report indices of model fit. For Trust in Community Leaders the model results were: χ2 = 145.303, df = 18, p = 0.0000; TLI = 0.956; CFI = 0.972; RMSEA = 0.043. The results of the CFA show sufficient construct validity of this 7-item measure of extent of trust in Community Leaders (Kline 2011).

The independent variable ‘accountability’ was assessed similarly through the construction of a latent variable composed of five items measured on a four-point Likert-type scale with response categories of strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, and strongly agree. Items were composed primarily of statements that reflect general perceptions regarding the need for financial accountability of charities. For instance, items included: “More attention should be paid to the way charities spend their money,” “More attention should be paid to the amount of money that charities spend on program activities,” “More attention should be paid to the way charities should raise money,” More attention should be paid to the amount of money charities spend on hiring professionals to do their fundraising,” and “Charities should be required to disclose how donors’ contributions are spent.”

The internal consistency of the items was assessed to determine the reliability of this measure. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.73. A CFA was undertaken to assess the construct validity of this variable utilizing the MPlus statistical software package (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012). The model fit indices were as follows: χ2 = 21.591, df = 5, p = 0.0006; TLI = 0.991; CFI = 0.996; RMSEA = 0.029. The results of the CFA show sufficient construct validity of this 5-item measure of perceptions of the level of accountability by charities.

For the independent variable assessing public perceptions of the level of ‘transparency’ of charities, a latent variable was constructed based on four items measured on a Likert-type scale with four response categories: poor, fair, good, or excellent. Respondents were asked to rate the transparency of charities. Items included how well charities provided information about (1) the programs and services they deliver, (2) how they use donations, (3) their fundraising costs, and (4) the impact of their work on Canadians. Reliability and validity were assessed the same as other variables previously described in this analysis. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this four-item measure of perceived transparency of charities was 0.77. The results of the CFA demonstrated sufficient construct validity of this 4-item measure: χ2 = 11.750, df = 1, p = 0.0006; TLI = 0.984; CFI = 0.997; RMSEA = 0.053.

The independent variable, ‘general familiarity of the work of charities,’ was operationalized through the creation of a latent construct comprised of 5 items measured on a four-point Likert-type scale. One item was a general statement relating to the respondents’ degree of familiarity with the work of charities (i.e., “Thinking about what you know about charities in general, the work that they do, and the role they play, would you say you are very familiar, somewhat familiar, not very familiar, or not at all familiar?”), and four items reflected specific actions demonstrating their degree of familiarity. These four items were assessed with response categories of strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, and strongly agree, and included the following items: (1) “I usually pay a lot of attention to media stories about charities”; (2) “I know less about charities than do my friends and family members”; (3) “Over the years, I have had many dealings with charities”; and (4) “If a friend or family member asked me how to choose a charity to support, I would be able to give them useful advice.” Reliability and validity were assessed the same as other variables previously described in this analysis. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this five-item measure of degree of familiarity with charities was 0.70. The results of the CFA demonstrated sufficient construct validity of this 5-item measure: χ2 = 22.437, df = 5, p = 0.0004; TLI = 0.989; CFI = 0.994; RMSEA = 0.030.

‘Direct familiarity’ was assessed through two items: volunteering and donating behaviors. Each was measured by a single item measure of whether or not respondents had volunteered time or donated money to charities in the 12 months preceding the survey. Response categories for each were a ‘0’ if they had not done either donating or volunteering, and a ‘1’ if they had.

Respondent demographics utilized in the analysis included their gender (a two category variable representing male or female), age (a six category variable representing age cohorts between 18 and over 65 years old), relationship status (a two category variable representing either single or having an intimate partner), highest level of education attained (a three category variable including less than high school, high school, and post-secondary), employment status (a three category variable including unemployed, part-time employed, and full-time employed), and household income category (a six category variable comprising income ranges from less than $20,000 to more than $150,000).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed by way of multiple regression, utilizing maximum likelihood estimation techniques, and were supported by the MPlus statistical software package (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012). This statistical software package was utilized because it allows for the simultaneous measurement and structural analysis (Kline 2011), which is a necessary condition for the use of the various latent variables constructed for this analysis.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 provides the frequencies and proportions of respondent demographic characteristics. The majority of respondents in this random sample were female (61.38%). The majority of respondents were over the age of 55. However, more than 42% of respondents were between the ages of 25 and 64, demonstrating good variability across different age cohorts. The majority of respondents indicated having an intimate partner—which could include being married or living common law. For the most part, respondents had completed post-secondary education, however a large proportion of the sample was unemployed. This—along with the general age of respondents—is characteristic of a generally older and retired sample of respondents (a point discussed further in the limitations of the study). There was broad variability in income categories among participants.

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics for the perceptions of trust in charities and other institutions, along with the perceptions of accountability, transparency, and familiarity.

General trust in charities was relatively high. In a response range from 0 to 3, the average level of trust reported by respondents was 1.88. In comparison to trust in business, government, and community leaders generally, the level of perceived trust in charities was higher on average. This provides support for our first hypotheses that charities will be rated as more trustworthy than other forms of institutions.

With regard to perceptions of accountability, transparency, and familiarity, the descriptive results in Table 2 suggest that respondents had a high regard for the need to be accountable and low regard for how well they perceived charities as transparent, and that they were moderately familiar with the work that charities do. For instance, the items used in our assessment of accountability reflected general statements about charities needing to be more financially accountable, and respondents indicated a high need for accountability. Likewise, with the assessment of public perceptions of transparency among charities, on average respondents had a low level of perceived transparency. Based on the items assessing this construct, this indicates that respondents perceived that charities did not do enough to be transparent about the programs and services they deliver, how they use donations, their fundraising costs, and the impact of their work on Canadians.

Finally, with regard to familiarity, the descriptive results show that respondents were moderately familiar with the work of charities based on our general assessment of familiarity. Direct familiarity was high among study participants through levels of donating, however the majority of respondents had not volunteered time with charities in the preceding 12 months. These results are in line with national surveys of volunteering and donating in Canada (Turcotte 2015).

Multiple Regression Analysis

Table 3 provides the results of the multiple regression analysis assessing the influence of the institutional trust, accountability and transparency of charities, and familiarity with charities as well as demographic variables on general perceptions of trust toward charities. The results show that a number of important variables contribute to an individual’s assessment of the level of trust they have in charities.

For instance, with regard to our second hypothesis, the results of the regression analysis show that trust in for-profits is associated with a statistically significant increase in the level of trust in charities. Similarly, trust in community leaders generally (a proxy of civil society actors, which is inclusive of more than just charities) has a significant positive effect on trust in charities.

Interestingly, and possibly counter to our original hypothesis, trust in government was not statistically significantly related to trust in charities. However, we note that based on the descriptive results from Table 2, participants in this study had very low levels of trust in government, on average. The results from the multiple regression analysis provides partial support for our first set of hypotheses.

Perceptions of the need for accountability, transparency, and familiarity of charities all had statistically significant effects on individual levels of trust in charities. For accountability, among this study sample, respondents who perceived the need for more financial accountability from charities had statistically significant lower levels of trust in charities, supporting our proposition. However, those who perceived that charities were transparent about their programs, how money was spent, and their overall impact on Canadians, had statistically significant higher levels of trust in charities. Thus, the results from the multiple regression analysis provides partial support for our second set of hypotheses.

The results for general familiarity of charities were also positively associated with trust in charities. That is, those that were more familiar with the work of charities generally had statistically significant higher levels of trust in charities. Further support for the role of familiarity in charities on trust is evidenced by the statistically significant positive findings that those who donate money are likely to have higher levels of trust in charities. However, with respect to volunteering, as a direct familiarity with charities, the association with trust in charities was not statistically significant. The results from the multiple regression analysis provide partial support for our third set of hypotheses.

Thus, while accountability in previous literature was not associated with trust, our study results show that among this random sample of Canadians, those who determine charities need to be more financially accountable have significantly lower levels of trust toward charities. Furthermore, while previous research has indicated that there is no relationship between direct familiarity (through behaviors such as donating and volunteering) and trust in charities, our findings show that those who donated money had higher levels of trust. However, no statistically significant results were found for volunteer behavior.

Finally, the results show that those with higher levels of education are more likely to trust in charities, those that are of lower age cohorts are less likely to trust in charities, and those that are single are less likely to trust in charities. These findings can be important findings for charities as they try to increase their levels of trust and engagement within their local communities (Table 4).

Discussion and Conclusion

We set out to explore predictors of trust within the Canadian charitable sector, including broad institutional trust, the need for accountability, the level of transparency, and the importance of familiarity. This study extends our understanding of trust in charities in several ways. First, it leverages data on the Canadian charitable sector, one of the larger (by per capita) nonprofit and voluntary sectors in the world. Much of the literature on trust in charities has been conducted in other contexts (e.g., the United States, United Kingdom, Australia), and this study provides the opportunity to explore how these findings might translate to similar (but not identical) liberal welfare states. Second, rather than exploring the influence of trust on outcomes like donating or volunteering, this study extends existing research on the determinants of nonprofit trust, exploring how accountability, transparency, familiarity, and general trust in institutions may uniquely be associated with perceptions of trustworthiness of their charitable sector.

Consistent with extant literature, our findings demonstrate that Canadian charities are perceived as more trustworthy than the business sector, government, or other community leaders. However, our findings also suggest that this perception of trustworthiness is positively associated with overall trust; in other words, individuals who generally trust their community leaders and the business sector are more likely to also trust charities. However, one striking exception to this relationship is trust in government. Respondents in our sample demonstrated an overall low level of trust in government—more than half a point below charities and the lowest of the sectors included in our model—and our model demonstrated no statistically significant relationship between trust in government and trust in the charitable sector.

While these findings provide tentative support for our hypothesis that charities benefit from general trust (and calls into question whether charities are truly facing a crisis of confidence due to lower levels of overall trust), they also suggest charities may benefit by highlighting their disassociation with government since trust in government is low. Considering research (Handy et al. 2010) that suggests challenges exist in distinguishing charities from both for-profit and governmental actors, charities may enhance trust by more clearly emphasizing distinction from their for-profit and governmental counterparts.

One possible avenue for emphasizing this distinction is increased public knowledge and awareness of the charitable sector. Both McDougle (2014) and Bourassa and Stang (2016) argue that enhancing overall understanding of this sector is a foundational step to improving trust: any campaign that seeks to improve confidence in the sector must necessarily begin with helping the public to better comprehend who charities are and what charities do. This distinction is particularly important given the sector’s ever-increasing role in the development and administration of social services. This growth was spurred, in a large part, by general decreases in governmental support.

Given that we found a strong and positive relationship between familiarity and trust, marketing efforts that enhance overall understanding of the sector could be beneficial in two ways. First, public awareness campaigns that emphasize charities’ unique and distinct contribution to the Canadian culture, economy, and safety net would underscore its role as a critical sector and one deserving of support. Second, enhanced knowledge of the sector as a whole and charitable operations in general could reduce misconceptions that ultimately damage trust. As Saxton (2004) writes, “The gap between public understanding and nonprofit reality is not sustainable. Because each time the public ‘accidentally’ bumps into the reality of modern charities they are likely to be left more suspicious, more cynical, more wary and less supportive” (p. 189).

Schlesinger et al. (2004) also emphasize the relationship between familiarity and trust, suggesting that one way to enhance trust among individuals unfamiliar with the sector (particularly charities’ unique ownership structure) is to highlight organizational accountability. Our findings provide some support for this argument. Respondents, on average, agreed that charities need to be more financially accountable; stronger agreement with this sentiment was associated with lower levels of trust in the sector. In other words, respondents who believed charities should be subject to greater financial oversight were less likely to trust organizations. However, this finding needs to be explored in future research to better understand the impetus for this link.

Additionally, transparency was strongly and positively correlated with trust in charities: respondents who believed charities provided adequate information about their operations and programming were more likely to find the sector trustworthy. Given the relatively low perception of charities as transparent, organizations should seek new or enhanced ways to share information about service delivery, donation use, fundraising costs, and overall impact. Ideally, this information would not only be more clearly communicated to existing stakeholders like donors and volunteers but would also be readily accessible by individuals who may be exploring the organization (or the sector) online or in person for the first time.

As with all research, there are limitations to this study and its generalizability. First, our sample over-represents both women and older adults, likely a function of the survey recruitment method (random digit dialing was conducted during daytime hours). Second, as articulated by Bourassa and Stang (2016), the dichotomous nature of our direct familiarity variables does not capture intensity of givingFootnote 3 or volunteering. This structure suggests familiarity with charities would not differ between an individual who gave or volunteered only once in the past year compared with someone who had done so multiple times, an assumption that is likely to be untrue. Thus, the role of direct familiarity in influencing organizational trust is likely to be conservatively estimated. Furthermore, future research might also consider how frequency and depth of volunteering influence organizational trust. By virtue of more directly working with organizational staff and/or service recipients, volunteers are uniquely embedded within the charity, yet our findings yielded no significant impact of volunteering on trust. Understanding whether this is simply a function of measurement challenges (e.g., blunt dichotomization) or indicative of how volunteers relate to organizations would provide meaningful direction for future studies. It could also imply that trust levels are captured by the other variables and volunteering neither enhances it or diminishes it.

One final limitation of our study is that the accountability measure relates only to financial accountability. As discussed earlier, other areas of accountability might include program related outcomes, social impact, and mission adherence, but the items available within this survey did not effectively capture these additional areas. Future research should more fully explore the different forms of accountability, including how they are communicated by organizations, understood and valued by donors (or other stakeholders), and their comparative influence on trust in charities. Understanding the relative weight of organizational outcomes versus organizational spending could provide fruitful direction for leadership and marketing staff in messaging their work and organization as trustworthy. Each of our findings contributes to practical implications for positive branding, marketing, and public engagement strategies with the general population to increase trust in the charitable sector.

Notes

These are nonprofits that are tax-exempt [(501(c)(3) designation in the US] and whose primary activities are charitable, religious, educational, scientific, and literary. They test for public safety, foster amateur sports competition, prevent cruelty to children, or prevent cruelty to animals. In this paper, we refer to such nonprofits as ‘charities’ both to distinguish them from the many other nonprofits and to be consistent with the term used in the Canadian context where this research is based.

A copy of this survey is publicly available at: https://www.muttart.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/3.-Talking-About-Charities-Full-Report-2013.pdf.

We dichotomized this variable from the question “As far as you can remember, did you donate to charities in 2012?” Regarding volunteering, participants were asked whether they volunteered for any charity in 2012.

References

Bekkers, R. (2003). Trust, accreditation, and philanthropy in the Netherlands. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 32(4), 596–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764003258102.

Bekkers, R., & Bowman, W. (2009). The relationship between confidence in charitable organizations and volunteering revisited. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(5), 884–897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764008324516.

Berman, G., & Davidson, S. (2003). Do donors care? Some Australian evidence. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 14(4), 421–430. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:VOLU.0000007467.74816.a4.

Bourassa, M. A., & Stang, A. C. (2016). Knowledge is power: Why public knowledge matters to charities. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 21(1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1537.

Bowman, W. (2004). Confidence in charitable institutions and volunteering. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(2), 247–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764004263420.

Brindle, D. (2018). Oxfam scandal is a body blow for the whole UK charity sector. Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/voluntary-sector-network/2018/feb/13/oxfam-scandal-body-blow-uk-charity-sector-sport-relief. Accessed 6 July 2018.

Bryce, H. J. (2007). The public’s trust in nonprofit organizations: The role of relationship marketing and management. California Management Review, 49(4), 112–131.

Burnett, K. (1992). Relationship fundraising. London: White Lion Press.

Carolei, D. (2018). How is Oxfam being held accountable over the Haiti scandal? British Politics and Policy at LSE. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/89096/1/politicsandpolicy-how-is-oxfam-being-held-accountable-over-the-haiti.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2018.

Cave, J. (2016). A shifting sector: Emerging trends for Canada’s nonprofits in 2016. The Philanthropist. http://thephilanthropist.ca/2016/01/a-shifting-sector-emerging-trends-for-canadas-nonprofits-in-2016/. Accessed 2 Dec 2017.

Charities Aid Foundation. (2018). CAF UK Giving 2018: An overview of charitable giving in the UK [PDF document]. Kent. https://www.cafonline.org/docs/default-source/about-us-publications/caf-uk-giving-2018-report.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2018

Clarke, L., & Carroll, L. E. (2016). Sociological and economic theories of markets and nonprofits: Evidence from home health organizations. American Journal of Sociology, 97(4), 945–969.

Cnaan, R., Jones, K., Dickin, A., & Salomon, M. (2011). Nonprofit watchdogs: Do they serve the average donor? Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 21(4), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.20032.

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Cooley, A., & Ron, J. (2002). The NGO scramble: Organizational insecurity and the political economy of transnational action. International Security, 27(1), 5–39.

Cornwall, A., Lucas, H., & Pasteur, K. (2000). Introduction: Accountability through participation—Developing workable partnership models in the health sector. Institute of Development Studies Bulletin, 31(1), 1–13.

Coyne, A. (2017). Take the politics out of charity? Far better to just cancel the tax break. National Post. http://nationalpost.com/opinion/andrew-coyne-take-the-politics-out-of-charity-far-better-to-just-cancel-the-tax-break. Accessed 14 Mar 2017.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Anheier, H. K. (1990). The sociology of nonprofit organizations and sectors. Annual Review of Sociology, 16, 137–159.

Donovan, K. (2007). Charity scams bust public trust. The Star. https://www.thestar.com/news/investigations/2007/06/02/charity_scams_bust_public_trust.html. Accessed 10 July 2017.

Dumont, G. E. (2013). Transparency or accountability? The purpose of online technologies for nonprofits. International Review of Public Administration, 18(3), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2013.10805261.

Ebrahim, A. (2003). Accountability in practice: Mechanisms for NGOs. World Development, 31(5), 813–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00014-7.

Ebrahim, A. (2005). Accountability Myopia: Losing sight of organizational learning. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 34(1), 56–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764004269430.

Ebrahim, A., & Weisband, E. (Eds.). (2007). Global accountabilities: Participation, pluralism, and public ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Edwards, M., & Hulme, D. (1996). Too close for comfort? The impact of official aid on nongovernmental organizations. World Development, 24(6), 961–973.

Emmett, B., & Emmett, G. (2015). Charities in Canada as an Economic Sector [PDF document]. Toronto, CA. http://www.imaginecanada.ca/sites/default/files/imaginecanada_charities_in_canada_as_an_economic_sector_2015-06-22.pdf. Accessed 5 June 2017.

Frumkin, P. (2002). On being nonprofit: A conceptual and policy primer. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Furneaux, C., & Wymer, W. (2015). Public trust in Australian charities: Accounting for cause and effect. Third Sector Review, 21(2), 99–127.

Gaskin, K. (1999). Blurred vision: Public trust in charities. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 4(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.66.

Giving USA. (2017). The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2016. Chicago: Giving USA Foundation.

Grønbjerg, K. A. (2009). Are nonprofits trustworthy? Bloomington: Indiana Nonprofit Sector: Scope and Community Dimensions. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8f49/b7cd608b841af771989b8707b73d4f0cbf32.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2017.

Grønbjerg, K. A., McGiverin-Bohan, K., Gallagher, A., Dula, L., & Miller, R. (2016). Briefing series: Indiana government officials and trust in nonprofits. Bloomington: Indiana Nonprofit Sector: Scope and Community Dimensions.

Hager, M. A., & Hedberg, E. C. (2016). Institutional trust, sector confidence, and charitable giving. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 28(2), 164–184.

Hale, K. (2013). Understanding nonprofit transparency: The limits of formal regulation in the american nonprofit sector. International Review of Public Administration, 18(3), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2013.10805262.

Hall, M. H., Barr, C. W., Easwaramoorthy, M., Sokolowski, S. W., & Salamon, L. M. (2005). The Canadian Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector in Comparative Perspective [PDF document]. Toronto: Imagine Canada. http://sectorsource.ca/sites/default/files/resources/files/jhu_report_en.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2017.

Handy, F. (1997). Co-existence of nonprofits, for profits, and public sector institutions. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 68(2), 201–223.

Handy, F. (2000). How we beg: The analysis of direct mail appeals. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29(3), 439–454.

Handy, F., Seto, S., Wakaruk, A., Mersey, B., Mejia, A., & Copeland, L. (2010). The discerning consumer: Is nonprofit status a factor? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39(5), 866–883. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764010362113.

Hansmann, H. B. (1980). The role of nonprofit enterprise. The Yale Law Journal, 89(5), 835–901. https://doi.org/10.2307/796089.

Hansmann, H. (1996). The ownership of enterprise. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press.

Herzlinger, R. E. (1996). Can public trust in nonprofits and governments be restored? Harvard Business Review, 74(2), 97–107.

Hillier, A. (2018). Oxfam: A crisis to end all crises. Third Sector. https://www.thirdsector.co.uk/oxfam-crisis-end-crises/communications/article/1459831. Accessed 10 July 2018.

Hyndman, N., & McConville, D. (2016). Transparency in reporting on charities’ efficiency: A framework for analysis. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterlyn, 45(4), 844–865. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764015603205.

Imagine Canada. (2010). Bill C-470: Twelve frequently asked questions [PDF document]. Toronto, CA: Imagine Canada. http://www.imaginecanada.ca/sites/default/files/c-470_top12_faq_en.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2017.

Independent Sector. (2016). United for charity: How Americans trust and value the charitable sector [PDF document]. https://www.independentsector.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/United-for-Charity-v5.pdf. Accessed 9 June 2017.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360.

Kearns, K. (1994). The strategic management of accountability in nonprofit organizations: An analytical framework. Public Administration Review, 54(2), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.2307/976528.

Keating, E. K., & Frumkin, P. (2003). Reengineering nonprofit financial accountability: Toward a more reliable foundation for regulation. Public Administration Review, 63(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00260.

Keirouz, K. S. (1998). Public perceptions and confidence in Indiana nonprofit organizations. Indianapolis: Indiana University Center of Philanthropy.

Kissane, R. J. (2003). What’s need got to do with it? Barriers to use of nonprofit social services. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 30(2), 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016565426011.

Kissane, R. J. (2010). The client perspective on nonprofit social service organizations. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(3), 632–637. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.

Kline, R. B (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Koppell, J. G. S. (2005). Pathologies of accountability: ICANN and the challenge of “multiple accountabilities disorder”. Public Administration Review, 65(1), 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00434.x.

Kramer, R. M. (2000). A third sector in the third millennium? VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 11(1), 1–23.

Lasby, D., & Barr, C. (2013). Talking about charities 2013: Canadians’ opinions on charities and issues affecting charities [PDF document]. Edmonton. https://www.muttart.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/3.-Talking-About-Charities-Full-Report-2013.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2017.

Lasby, D., & Barr, C. (2015). Giving in Canada: Strong philanthropic traditions supporting a large nonprofit sector. In P. Wiepking & F. Handy (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of global philanthropy (1st ed., pp. 25–43). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Light, P. C. (2008). How Americans view charities: A report on charitable confidence, 2008 [PDF document]. Washington, DC. https://wagner.nyu.edu/files/faculty/publications/04_nonprofits_light.pdf. Accessed 2 Dec 2017.

McDougle, L. (2014). Understanding public awareness of nonprofit organizations: Exploring the awareness–confidence relationship. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 19(3), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.

McDougle, L., & Handy, F. (2014). The influence of information costs on donor decision making. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 24(4), 465–485. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21105.

McDougle, L., & Lam, M. (2014). Individual and community-level determinants of public attitudes toward nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(4), 672–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764013479830.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th edn.). Los Angeles: Muthén and Muthén.

Newport, F. (2017). Americans’ confidence in institutions edges up. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/212840/americans-confidence-institutions-edges.aspx. Accessed 7 July 2018.

Nye, J. S., Zelikow, P. D., & King, D. C. (Eds.). (1997). Why people don’t trust government. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

O’Neill, M. (2009). Public confidence in charitable nonprofits. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(2), 237–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764008326895.

Prakash, A., & Gugerty, M. K. (2010). Trust but verify? Voluntary regulation programs in the nonprofit sector. Regulation and Governance, 4(1), 22–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2009.01067.x.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Ries, T. E., Bershoff, D. M., Adkins, S., Armstrong, C., & Bruening, J. (2018). 2018 Edelman Trust Barometer Trust Barometer: Global Report [PDF document]. New York. https://cms.edelman.com/sites/default/files/2018-01/2018%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Global%20Report.pdf. Accessed 10 July 2018.

Rimington, J. (2018). Five tips to avoid a scandal like Oxfam Great Britain’s. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/five_tips_to_avoid_a_scandal_like_oxfam_great_britain. Accessed 9 July 2018.

Rutley, R., & Stephens, I. (2017). Public Trust And Confidence in Australian Charities. http://www.acnc.gov.au/ACNC/Publications/Reports/Public_Trust_2017.aspx.

Salamon, L. M. (2012). The resilient sector. In L. M. Salamon (Ed.), The state of nonprofit America. (2nd ed., pp. 3–88) Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Sargeant, A. (1999). Charitable giving: towards a model of donor behaviour. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(4), 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725799784870351.

Sargeant, A., & Lee, S. (2002). Individual and contextual antecedents of donor trust in the voluntary sector. Journal of Marketing Management, 18(7–8), 779–802. https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257022780679.

Sargeant, A., & Lee, S. (2004). Donor trust and relationship commitment in the U.K. charity sector: The impact on behavior. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(2), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764004263321.

Saxton, J. (1995). A strong charity brand comes from strong beliefs and values. Journal of Brand Management, 2(4), 211–220.

Saxton, J. (2004). Editorial: The Achilles’ Heel of modern nonprofits is not public “trust and confidence” but public understanding of 21st century charities. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 9(3), 188–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.246.

Schatteman, A. (2013). Nonprofit accountability: To whom and for what? An introduction to the Special Issue. International Review of Public Administration, 18(3), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2013.10805260.

Schlesinger, M., Mitchell, S., & Gray, B. H. (2004). Restoring public legitimacy to the nonprofit sector: A survey experiment using descriptions of nonprofit ownership. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(4), 673–710. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764004269431.

Schmitz, H. P., Raggo, P., & Bruno-van Vijfeijken, T. (2011). Accountability of transnational NGOs: Aspirations versus practice. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(6), 1175–1194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011431165.

Shier, M. L., & Handy, F. (2013). Understanding online donor behavior: the role of donor characteristics, perceptions of the internet, website and program, and influence from social networks. International Journal of Nonprofit & Voluntary Sector Marketing, 17(3), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1425.

Sisco, H. F., Collins, E. L., & Zoch, L. M. (2010). Through the looking glass: A decade of Red Cross crisis response and situational crisis communication theory. Public Relations Review, 36(1), 21–27.

Sloan, M. F. (2009). The effects of nonprofit accountability ratings on donor behavior. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(2), 220–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764008316470.

Smith, S. R., & Lipsky, M. (1993). Nonprofits for hire: The welfare state in the age of contracting. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tremblay-Boire, J., & Prakash, A. (2014). Accountability.org: Online disclosures by U.S. Nonprofits. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26(2), 693–719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9452-3.

Turcotte, M. (2015). Volunteering and charitable giving in Canada [PDF document]. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-652-x/89-652-x2015001-eng.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2017.

Weisbrod, B. A. (1998). The nonprofit mission and its financing. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 17(2), 165–174.

Williams, A. P., & Taylor, J. A. (2013). Resolving accountability ambiguity in nonprofit organizations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24(3), 559–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9266-0.

Wilson, M., & Hegarty, N. (1997). Public perceptions of nonprofit organizations in Michigan. Lansing: Institute for Public Policy and Social Research.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to have this data which were made available to us by generosity of the Muttart Foundation (Canada) and Imagine Canada. The authors are very grateful to the Muttart Foundation and Imagine Canada for the use of their 2013 dataset.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Farwell, M.M., Shier, M.L. & Handy, F. Explaining Trust in Canadian Charities: The Influence of Public Perceptions of Accountability, Transparency, Familiarity and Institutional Trust. Voluntas 30, 768–782 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-00046-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-00046-8