Abstract

This article seeks to unravel the dual realities represented by the juxtaposition of the recent series of harsh regulatory impositions on Russian nonprofit organizations and the nearly simultaneous enactment of a series of laws and decrees establishing an impressive “tool box” of positive support programs for a large class of the so-called socially oriented Russian nonprofit organizations. To do so, the discussion proceeds in three steps. First, the article documents the considerable scale of the Russian NPO scene as it is visible through the lens of available empirical research. Next, it outlines the key policy measures affecting nonprofit organizations (NPOs) put in place by the Russian government beginning in the latter part of the first decade of the 21st century. Unlike some accounts, however, this one brings into focus both the interesting “tool box” of support programs for NPOs enacted during this period as well as the more restrictive regulatory measures, such as the “foreign agents law,” that also came into force. Finally, the article seeks to unravel the puzzle posed by these apparently competing realities of Russian government policy toward nonprofit organizations by bringing to bear the conceptual lenses that Graham Allison formulated to make sense of the strange series of actions that surrounded the Cuban Missile Crisis a little over 50 years ago.

Résumé

Cet article cherche à démêler la double réalité représentée par la juxtaposition de la récente série de règlementations sévères portant sur les organisations à but non lucratif russes, et l’adoption presque simultanée d’une série de lois et de décrets instituant une impressionnante « boîte à outils » de programmes de soutien positifs pour une vaste catégorie d’organisations à but non lucratif russes dites à vocation sociale. Pour ce faire, l’analyse procède en trois étapes. Tout d’abord, l’article contient des informations sur l’ampleur considérable de la scène russe des organisations à but non lucratif, telle que l’on peut la voir à travers le prisme des recherches empiriques disponibles. Ensuite, il décrit les mesures politiques clés qui affectent les organisations à but non lucratif (OBNL) mises en place par le gouvernement russe au début de la dernière partie de la première décennie du XXIe siècle. Contrairement à certains témoignages, cependant, celui-ci clarifie la « boîte à outils » des programmes de soutien pour les OBNL adoptés au cours de cette période, ainsi que des mesures règlementaires plus restrictives, comme la loi sur les « agents étrangers » , également entrée en vigueur. Enfin, l’article cherche à démêler l’énigme posée par les réalités apparemment concurrentes de la politique du gouvernement russe à l’égard des organisations à but non lucratif en mettant en valeur les visions conceptuelles formulées par Graham Allison pour comprendre l’étrange vague de mesures ayant entouré la crise des missiles de Cuba il y a un peu plus de 50 ans.

Zusammenfassung

Dieser Beitrag versucht, die duale Realität zu verdeutlichen, die sich in den einerseits neuesten strengen regulatorischen Anforderungen an russische gemeinnützige Organisationen und der andererseits nahezu zeitgleichen Verabschiedung einer Reihe von Gesetzen und Verordnungen, die eine beeindruckende „Toolbox“von positiven Unterstützungsprogrammen für eine große Gruppe so genannter sozialorientierter russischer gemeinnütziger Organisationen darstellt, zeigt. Dazu ist die Diskussion in drei Teile unterteilt. Zunächst dokumentiert der Beitrag das beträchtliche Ausmaß der russischen gemeinnützigen Organisationen, wie es in durchgeführten empirischen Forschungsarbeiten zu sehen ist. Anschließend werden die wichtigsten sich auf die gemeinnützigen Organisationen auswirkenden politischen Maßnahmen zusammengefasst, die von der russischen Regierung seit Ende des ersten Jahrzehnts im 21. Jahrhundert eingeführt wurden. Doch anders als bei anderen Schilderungen konzentriert man sich hier sowohl auf die in diesem Zeitraum entstandene interessante „Toolbox“von Unterstützungsprogrammen für gemeinnützige Organisationen als auch auf die restriktiveren regulatorischen Maßnahmen, wie das verabschiedete „Auslandsagenten-Gesetz“. Abschließend versucht der Beitrag, das Puzzle zu lösen, das sich aus diesen scheinbar konkurrierenden Realitäten der russischen Regierungspolitik gegenüber gemeinnützigen Organisationen ergibt, indem die von Graham Allison formulierten begrifflichen Perspektiven zur Anwendung gebracht werden, mit Hilfe derer er die kuriosen Maßnahmen im Zusammenhang mit der Kubakrise vor etwas mehr als 50 Jahren nachzuvollziehen versuchte.

Resumen

El presente artículo trata de desentrañar las realidades duales representadas por la yuxtaposición de la reciente serie de imposiciones regulatorias sobre las organizaciones rusas sin ánimo de lucro y la casi simultánea aplicación de una serie de leyes y decretos que establecen una impresionante “caja de herramientas” de programas de apoyo positivos para una amplia clase de las denominadas organizaciones rusas sin ánimo de lucro orientadas socialmente. Para hacerlo, el debate prosigue en tres pasos. En primer lugar, el artículo documenta la considerable escala de la escena de las OSL/NPO rusas ya que es visible a través de las lentes de la investigación empírica disponible. En segundo lugar, esboza las medidas políticas claves que afectan a las organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro (OSL/NPO) implantadas por el gobierno ruso a comienzos de la última parte de la primera década del siglo XXI. A diferencia de algunas consideraciones, sin embargo, esto centra la atención tanto en la interesante “caja de herramientas” de programas de apoyo para las OSL/NPO promulgadas durante este período, así como también en las medidas regulatorias más restrictivas, tales como las “leyes de agentes extranjeros” que también entraron en vigor. Finalmente, el artículo trata de desentrañar el rompecabezas planteado por estas realidades aparentemente contradictorias de la política gubernamental rusa hacia las organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro aplicando las lentes conceptuales que Graham Allison formuló para dar sentido a la extraña serie de acciones que rodearon la Crisis de los Misiles Cubanos hace poco más de 50 años.

摘要

本文努力揭示俄罗斯非盈利组织所面临的双重现实,俄罗斯一方面最近出台一系列针对其非盈利组织的严格规范,另一方面又在几乎同一时间颁布了一系列法律法令,为俄罗斯所谓的以社会为导向的非盈利组织的支持计划提供了阵容强大的“工具箱”。 为了揭示这一双重现实, 讨论按三个步骤进行, 第一步, 文章描述了通过现有的经验主义研究的视角看到的俄罗斯的非盈利组织的恢宏规模,第二步, 文章大致描绘了俄罗斯政府21世纪头十年制订的、影响非盈利组织的关键政策措施。 和其他的 描述不同, 本文的描述集中在这一时期为非盈利组织制订的支持计划的有趣的“工具箱”以及同时生效的更强的限制性规定,例如,“外国代理人法”。 最后, 文章利用格雷厄姆·阿利森(Graham Allison)揭开大约50年前的古巴导弹危机的一系列奇怪的行为所采用的概念视角,揭开了俄罗斯政府对非盈利组织采取的明显对立的政策的背后的谜团。

ملخص

تسعى هذه المقالة لكشف الحقائق المزدوجة التي يمثلها تجاور السلسلة الأخيرة من الأعباء التنظيمية القاسية على المنظمات الغير ربحية الروسية والتشريعات في وقت واحد تقريبا” لسلسلة من القوانين والمراسيم التي تنشئ “صندوق الأدوات” المثير للإعجاب من برامج الدعم الإيجابي لفئة كبيرة مما يسمى بالمنظمات الغير ربحية الروسية ذات الإتجاهات الإجتماعية. للقيام بذلك، المناقشة تقدمت في ثلاث خطوات. أولا”، توثق المقالة نطاق كبير من مشهد المنظمات الغير ربحية (NPO) الروسي كما هو واضح من خلال عدسة البحوث التجريبية المتاحة. بعد ذلك، الخطوط العريضة لتدابير السياسات الرئيسية التي تؤثر على المنظمات الغير ربحية (NPO) التي وضعتها الحكومة الروسية بدأت في الجزء الأخير من العقد الأول من القرن 21. على عكس بعض الحسابات، لكن هذا يجلب الإهتمام “لصندوق الأدوات” من برامج الدعم الغير ربحي التي تم إصدارها خلال هذه الفترة فضلا” عن تدابير تنظيمية أكثر صرامة، مثل “قانون العملاء الأجانب”، الذي جاء أيضا” للتركيز على حد سواء للقوة. أخيرا”، تسعى المقالة لكشف اللغز الذي تشكله هذه الحقائق التي تبدو متنافسة لسياسة الحكومة الروسية تجاه المنظمات الغير هادفة للربح من خلال الإفادة من العدسات المفاهيمية التي وضعها جراهام أليسون (Graham Allison) ليعطي معنى لسلسلة غريبة من الإجراءات التي تحيط بأزمة الصواريخ الكوبية منذ أكثر من 50 عام بقليل.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A striking sense of alternative realities seems to characterize the prevailing pattern of government–nonprofit relations in contemporary Russia. Viewed from the West, the overwhelming image of the Russian nonprofit scene is one of escalating authoritarian suppression reflected, for example, in a 2006 revision of the “Law on Noncommercial Organizations” that imposed new restrictions on Russian nonprofit organizations; the much-disputed “foreign agents” law of 2012 that requires Russian nonprofits receiving foreign support to register as “foreign agents,” to report to authorities regularly on their sources of funding and activities, and to endure limits on their participation in political activities; and the recent 2015 law placing additional burdens and penalties on the so-called “undesirable” organizations (see, for example, Bourjaily 2006; Maxwell 2006; ICA, INP 2007; Ljubownikow et al. 2013; BBC 2015).

Largely missing from this dominant external narrative, however, is much recognition of an alternative domestic reality that features the emergence of a fairly robust new “tool kit” of governmental supports to the so-called Russian “socially-oriented” nonprofit organizations and that calls to mind in some the “welfare partnerships” that characterize government–nonprofit relationships in huge swaths of western Europe and, to a lesser extent, the United States, as documented by the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project (Salamon et al. 2004, 2016, forthcoming).

How are we to make sense of these competing realities? Which one is the “real” nonprofit-government relationship in contemporary Russia?

No single answer to these questions may be possible. But some useful clues are available in the interesting analysis of U.S.-Soviet interaction during the Cuban missile crisis produced years ago by political scientist Graham T. Allison (1969, 1971). In an attempt to answer the questions of why the Soviet Union decided to place missiles in Cuba, why the U.S. government responded with a blockade that located farther from the shores of Cuba—and therefore closer to the Soviet Union than the President thought he had ordered—and why Russia ultimately withdrew, Allison posits three explanatory models. The dominant model in contemporary political analysis Allison identifies as the “Rational Actor Model.” According to this model, governmental actions can be explained as the “more or less purposive acts of unified national governments.” But governments may not be unified and fully hierarchical. This can give rise to what Allison terms the “Bureaucratic Politics Model,” which views government actions not as rational choices of individual decision-makers, but as the “outcomes of various overlapping bargaining games among players arrayed hierarchically” in a governmental system. Finally, even this model may fail to do justice to actual realities. In practice, what governments actually do may be substantially conditioned by the standard operating procedures hard-wired into governmental agencies and largely impervious to the choices of governmental leaders or the outcomes of bureaucratic bargaining process, at least in the short-run. Here, it is pre-cooked “Organizational Processes” that are in the driver’s seat to a significant extent.

A key feature of Allison’s analysis is that all three models can be at work at the same time in a country, and even in a particular policy arena. This is so because what appear from the outside to be single, unified actions, may be—and most likely are—actually composed of entire suites of actions, each of which may be a manifestation of a different decision dynamic and therefore explainable in terms of a different one of the explanatory models. The task of policy analysis, therefore, is to deconstruct any set of actions and separately examine which of the alternative models seems to be at work in the particular subset under scrutiny.

Manifestations of all three of these models can certainly be seen in the literature attempting to unravel the puzzle of Russia’s seemingly inexplicable and inconsistent pattern of government–nonprofit relationships, though there is a general tendency to seek a single, comprehensive explanation of what, in Allison’s logic, may be a collection of separate actions each of which may be explainable in terms of a different one of the three analytical models. The Rational Actor model, for example, finds expression among those few analysts wedded to the authoritarian-suppression view of Russian government–nonprofit relations who are willing to acknowledge the concurrent presence of policies of support to nonprofit organizations. According to this view, this apparent contradictory set of policies is not contradictory at all. Rather, they are twin pillars of a single, unified, and highly effective policy of repression. One especially inventive statement of this view is presented in Francois Daucé’s “The Duality of Coercion in Russia.” According to Daucé (2015, p. 59, 72): “In contemporary Russia, control of NGOs uses both repression by law-enforcement, on the one hand, and liberal management by public subsidy, on the other….[A]llocating public funding to Russian human rights groups is… the second part of the enforcement of the foreign agents law.” Even the apparently chaotic pattern of enforcement of the “foreign agents” law is viewed by Daucé as a part of the overall policy of repression, designed to sow uncertainty among affected nonprofits and thereby encourage some to break ranks and believe they can evade the restrictions if they merely lie low (Daucé 2015, pp. 68–70).

The Bureaucratic Politics explanation of these divergent features of Russian government interaction with the nonprofit sector emphasizes instead the presence of different circles of actors within the Russian government itself as well as divergent components of the nonprofit sector. According to this line of argument, the Russian government may not be as monolithic as it may appear. The old bureaucratic maxim that “where you stand depends on where you sit” may hold sway in Russian governmental agencies just as it does in other bureaucratic arenas. At the policy level as well, different perspectives can be at work. One analysis of the Russian scene identifies these as liberal, technocratic, and protective—or market-oriented, pragmatic, and conservative (Sakwa 2011). The fact that policies on the nonprofit sector are split widely among different ministries likely accentuates this fragmentation of policy outcomes. Different circles can push different approaches in the different spheres over which they exercise some control, and political leaders can function as umpires in this inter-organizational jostling rather than all-powerful autocrats wielding total power over all decisions. Fortescue (2010) attributes this phenomenon to what he terms the “logic of specialization,” the need in complex societies—even those with less than fully open political systems—to make provision in their policy processes for those with specialized functions and specialized knowledge to “be involved in those policy processes that are relevant to their area of specialization.” Adding to the persuasive power of this model is the possibility that diversity of views among governmental actors may be mirrored by varied perspectives among those outside the policy-making machinery, in the society at large, and even, in this case, among nonprofit organizations themselves. One line of argument here emphasizes the existence of a significant differentiation within the Russian nonprofit sector between the relatively small band of organizations that surfaced in the immediate post-Soviet period with support from Western donors eager to promote openness and democracy or such global issues as environmental protection and HIV/AIDS prevention in Russia, and the much larger array of organizations more fully “rooted” in Russian realities and focused less on promoting further democratic reforms than on practical tasks such as filling in for missing state services or advocating for help for particular social groupings, based on their own understanding of social priorities (Jakobson and Sanovich 2010).

Finally, the shape of government–nonprofit interaction as it plays out on the ground may result less from the choices of powerful central actors or the outcomes of bureaucratic struggles than from the operation of bureaucratic routines or, alternatively, their absence. The chaotic pattern of implementation of the foreign agent law that Daucé attributes to the devious intention of central leaders intent on sowing discord among affected nonprofits may thus be more easily explained by the failure of lawmakers to provide the clarity that implementing bureaucrats needed to carry out their enforcement job without fear of running afoul of prevailing laws or procedures, or of prevailing expectations of their superiors. So, too, as we will see, some part of the challenges that have emerged with the implementation of the subsidies designed to support nonprofit organizations may be attributed to adherence to contracting procedures designed for completely different types of procurements.

The purpose of this article is to examine recent patterns of government–nonprofit interaction in Russia in the light of these alternative models with an eye to determining what share each one can claim to explaining the outcomes that are evident. Since the Rational Actor model has gained the most traction in the available literature, much of our attention will focus on the traction available to the other two in explaining the curious patterns that exist. To do so, the discussion proceeds in three steps. In the first step, we examine some of the salient dimensions of the Russian nonprofit scene as they are visible through the lens of available empirical research. In step two, we outline the key policy measures affecting nonprofit organizations (NPOs) put in place by the Russian government beginning in the latter part of the first decade of the 21st century. Unlike some accounts, however, we bring into focus both the interesting “tool box” of support programs for NPOs enacted during this period as well as the more restrictive regulatory measures—such as the “foreign agents” law—that also came into force. Finally, in step three we bring the three models identified above to bear on the reality we will have laid out to assess what aspects of that developing reality each one is able to explain.

Inevitably, the reality that is covered here pertains mostly to the national level. The paper by Krasnopolskaya, Skokova, and Pape later in this special issue then carries the story down to the regional level, where an even more complex set of forces is likely to be at work.

Part I. The Scope and Resources of the Russian Third Sector

The state of the Russian nonprofit sector and the shape of its relations with the government are largely a product of the contradictory Soviet and post-Soviet development of the country. The restoration of a market economy and the attempts at building up a democratic state in Russia occurred after an unprecedented interruption of 80 long years. The Soviet system not only ran an economy based on central planning and restricted civil rights, but it conducted a focused effort at indoctrination of several generations of people with an ideology that claimed to be diametrically opposed to the market and democracy. In addition, it put in place a set of mass organizations heavily controlled by a dominating party and state. The length of the Soviet era could not but produce a certain path dependency as a consequence (see, for example, Howard 2003) affecting both the attitudes of citizens and the institutional structure of the post-Soviet nonprofit sector. In particular, at least some of the Soviet-era mass organizations transformed themselves into nonprofit organizations and survived into the post-Soviet era, often in possession of assets transferred to them during the transition. They were joined, however, by at least two other more or less distinct sets of organizations—a variety of citizen organizations formed, or newly expanded, in the immediate aftermath of the transition, partly with the help of outside funding, and dedicated to promoting long-ignored civil and political rights as well as consumer and environmental causes; and a substantial number of small nonprofit service-oriented organizations attempting to supplement services provided by state-owned institutions in the areas of education, child welfare, health, elderly services, and many more, to serve categories of people “falling through” the traditional Soviet social safety net (e.g. the homeless, the very poor, AIDS sufferers, etc.), or to address new policy priorities such as environmental protection.

This mixture of nonprofit entities was further complicated by the presence of a growing number of religious organizations belonging to the four Russian “traditional” confessions—Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Buddhism—now freed of the limiting power of the dominant state and party with their ideology of secularism. In short, the post-Soviet nonprofit sector was hardly a monolith, with old-style mass organizations mixing with fairly new human rights organizations, a variety of localized service organizations, and a growing and diverse, but generally conservative, and—at least in the case of the Russian Orthodox Church, fairly hierarchical—religious community.

While the resulting nonprofit sector is full of diversity, however, it was, and still is, hardly overwhelming in scale. Fortunately, thanks to a series of surveys conducted since 2006 by researchers at the National Research University Higher School of Economic (NRU HSE) through the Russian Civil Society Monitoring Project (RCSM), supplemented by data produced by Russia’s statistical agency, Rosstat, and assembled by NRU HSE researchers in cooperation with the Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies (Mersianova et al. 2016, forthcoming), it is possible to portray the basic contours of this Russian nonprofit sector, except for its religious congregation components, in solid empirical terms.Footnote 1 For these purposes, we define the nonprofit sector, following the definition formulated as part of the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project and subsequently incorporated into the official United Nations Handbook on Nonprofit Institutions in the System of National Accounts (UN 2003), as (i) a set of institutions that (ii) are not part of the structures of the government, that (iii) cannot distribute profits to their directors or members, that (iv) are self-governing, and that (v) people take part in freely and without compulsion (Salamon et al. 2003). Fortunately, this definition compares quite closely to that found in Russia’s Federal Law “On Noncommercial Organizations” of January 12, 1996 No. 7-FZ (Government of the Russian Federation 1996), which constitutes the essential legal basis for third sector institutions in Russia.

According to 2014 RCSM data, in excess of 430,000 such NPOs are officially registered in Russia. However, an estimated 60 % of these are de facto inactive, so that the population of operating nonprofits is closer to 200,000.

Most Russian NPOs are small. As noted in Fig. 1, 34 % of the organizations have no permanent paid staff and another 34 % have only 5 or fewer paid employees. Only 4 % claim to have over 31 persons on their permanent staff. Nearly 70 % of organizations have volunteers working for them; however, only 13 % have more than 50 volunteers working in a typical month.

Because of Russia’s size, even this collection of small organizations can add up to a sizable workforce, however. As of 2008, Russian NPOs employed 554,000 paid full-time equivalent (FTE) workers, or 0.7 % of the economically active population (EAP).Footnote 2 What is more, these organizations engaged nearly 2 million volunteers—which translate into the additional 316,000 FTE jobs—bringing the total workforce of Russian NPOs to 870,000 FTE workers, or 1.2 % of the country’s EAP. In absolute terms, this is a large number of people working in the civil society sector, larger than the number of nonprofit workers in all but five European countriesFootnote 3 on which data are available (Mersianova et al. 2016, forthcoming).

Still, the size of the nonprofit sector in Russia as a share of the country’s EAP is well below that of other countries. Thus, the Russian civil society sector’s 1.2 % share of EAP as of 2008 ranked substantially below the 5.7 % average for the 41 countries for which such data are available, as shown in Fig. 2.

Nonprofit FTE paid and volunteer work force as a share of economically active population, 41 countries. Source Salamon et al. (2016, forthcoming)

Most (about 57 %) of the NPO paid and volunteer workforce in Russia is engaged in expressive activities, especially advocacy (18 %); culture, sports, and recreation (16 %); and professional associations and unions (14 %). Service activities employ only 34 % of the workforce, of which social services account for 21 % (see Table 1). This may reflect in part the survival into the post-Soviet period of some of the Soviet-era mass organizations newly reconstituted as NPOs. Possibly reflecting this, these expressive organizations tend to be larger than the average nonprofit organization. Thus, though they account for 57 % of the workforce, expressive organizations make up a considerably smaller 50 % of the organizations.

The funding structure of the Russian nonprofit sector differs widely from that of most other countries, except for those in less developed regions. The total revenue of the civil society sector in Russia was 314.3 billion rubles (US$12.3 billion) in 2008. More than half of that amount (51 %) came from fees, as Table 2 shows. The second largest source is philanthropy, especially business philanthropy, which accounted for 33 % of income. Since a substantial proportion of fees likely take the form of membership dues—which are similar in character to charitable contributions—the philanthropy portion of the total may really be higher than this. Government, on the other hand, accounted for only 15 % of the total, well below the 41-country average of approximately 35 % and far from the Western European “welfare partnership” average of over 60 % (Salamon et al. 2016, forthcoming).

Reflecting this significant dependence on charitable giving, the financial situation of Russian NPOs can be described as strained, even before the 2009 economic crisis and 2014 collapse in the price of oil, Russia’s key source of income. Only around half of the respondents to the RCSM survey in 2008 were able to report that the financial resources at their disposal were sufficient to implement their current set of core activities. Others were experiencing various forms of fiscal stress even to keep current activities going.

Part II. The Expanding Tool Kit of Government Programs Targeting Nonprofit Organizations

Against a backdrop of the growth of a fairly sizable but relatively weak nonprofit sector, Russia undertook a fairly significant program of supports to at least a subset of the so-called “socially oriented” NPOs in the latter part of the first decade of the 21st century. At the same time, these supports were followed up by the introduction of the “foreign agents” law (Federal Law No. 121-FZ, 2012, see: Government of the Russian Federation 2012) and the “undesirable” organizations law (Federal Law No.129-FZ, 2015, see: Government of the Russian Federation 2015)—two pieces of legislation that restrict access to foreign funding, depriving NPOs of one important source of support. Beyond that, many observers, both Western and Russian, criticize the “foreign agents” law for making advocacy an uneasy choice of activity for any NPO in Russia, and for its capacity to inflict damage on the reputation of nonprofit organizations relying on foreign grants as a source of income, irrespective of the field of activity they are engaged in.

In this section, we describe the basic components of these two sets of policy measures before turning, in the next section, to an attempt to understand what is really at work and what it shows about the government’s long-term intentions with respect to the nonprofit sector.

The Rationale for Government–Nonprofit Cooperation

A powerful rationale exists for the forging of mutually supportive collaboration between governments at all levels and private, nonprofit organizations. But as the prior paper in this special issue by Salamon and Toepler demonstrated, that rationale has had to make its way against some heavy ideological headwinds and early economic theories of the nonprofit sector (Salamon 1987). Both those on the political left and those on the political right have had reason to oppose such collaboration, or to ignore it when it developed. For those on the right, the presence of a private nonprofit sector has long been perceived not as a partner with the state, but as a convenient excuse for resisting state expansion, leaving the task of social and economic protections to the tender mercies of wealthy individuals rather than tax-financed governmental protections. For those on the left, too warm an embrace of the nonprofit sector could weaken the case for robust state action. These ideological blinders were then reinforced by academic economic theories justifying the existence of nonprofit organizations on the highly limited basis of satisfying the unsatisfied demands for collective goods created by the twin limitations—indeed “failures”—of both markets and democratic governments. Such theories left little basis for supporting government–nonprofit cooperation, let alone for considering such cooperation to be intellectually legitimate, since nonprofits could only be justified operating in fields where government is absent.

In fact, however, governments around the world have kept finding their way to cooperative ties with nonprofits. A significant part of the German social welfare system established by Bismarck in the late 19th century built on a foundation of partnership between the state and church-inspired social welfare institutions that was later powerfully expanded in the post-WWII era. In 1917, as the paper by Brandsen and Pape in this special issue makes clear, the Netherlands solved a significant battle over control of its public education system by launching state-financed vouchers that gave parents the opportunity to send their children to private, nonprofit, religiously affiliated schools at state expense, and this model was followed in subsequent expansions of the Dutch welfare state. When the U.S. finally expanded its national support for publicly funded social welfare services under President Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society,” it similarly chose what analyst Lester Salamon has termed “third-party government”—the reliance by government on third parties, particularly nonprofit organizations, to deliver the services that government was financing.

Underlying these pragmatic decisions lay a fundamental realization that filled a conceptual gap left by prior theories that no one type of institution has a monopoly on the skills or capabilities to solve complex social and economic problems, that each has its own strengths and limitations, and that when these strengths and limitations are mirror images of each other it creates opportunities for win–win outcomes. And in the case of government and the nonprofit sector, these respective strengths and limitations are well matched, with government equipped to generate resources through its command of the tax authority but ill-equipped to deliver human services at a human scale, and nonprofits poorly equipped to generate revenue but ideally suited to deliver benefits in a personal and sensitive way.

For such partnerships to work, however, care must be taken to acknowledge the special qualities of the respective partners. And this is where the choice of “tool” of public action comes in, for different tools—grants, contracts, loans, loan guarantees, vouchers, regulation, and others—can affect the inherent viability and strengths of the respective partners. Hence, the concept of “third-party government” has come to be linked with a new field of public administration study focusing on the choice, design, and operation of the different tools through which such partnerships are structured (Salamon 2002). Some tools are more indirect than others. Some are more coercive. And some tilt the balance between nonprofit and for-profit providers, often with unexpected consequences.

During the first decade of the 21st century, the Russian government took some significant steps toward creating its own tool kit for connecting to the country’s nonprofit sector. Whether it followed the conceptual trail outlined here or some other set of preoccupations remains to be explored, but a first step is naturally to identify the machinery that it put in place.

Russia’s New Government–Nonprofit Tool Kit

This machinery was first heralded in a document entitled “A Concept to Facilitate the Development of Charitable Activities and Volunteering in the Russian Federation” issued by the Government of the Russian Federation on July 30, 2009 (Government of the Russian Federation 2009). In this Concept document, the Russian government signaled its intention to open the way to increased cross-sector cooperation in the delivery of social services in order to promote philanthropy and volunteering, encourage innovation, and augment the resources available to address social welfare. This was then followed by an Address to the Federal Assembly “On Budgetary Policy” in which President Medvedev outlined an ambitious agenda calling for tax incentives for service-providing NPOs; expanded NPO access to purchase-of-service contracting at all levels of government; expanded government grant-making to NPOs; legal changes to facilitate NPOs in endowment building; and a careful review of legislative norms and regulations to identify and revise any that put socially oriented NPOs at a competitive disadvantage compared to state-owned institutions providing social services (Medvedev 2011).

Over the next several years, a series of laws and regulations was issued to translate these proposals into concrete programs. The resulting Russian government tool kit for interacting with NPOs thus includes the following, fairly comprehensive set of tools:

-

(1)

Direct and indirect grants, known in Russian as “federal government subsidies;”

-

(2)

Purchase of service contracts;

-

(3)

Transfer of property rights to allow for access to office space at subsidized rental payments or for free;

-

(4)

Tax incentives for NPOs, their donors, the recipients of charitable contributions, and the beneficiaries of charitable services;

-

(5)

Information support, technical assistance, and training; and

-

(6)

Regulation.

What is more, the Federal law leaves the list of forms of support for NPOs open-ended, subject to extension by the Federal Parliament, by legal acts adopted by legislative assemblies of Russian regions, or by legal acts of local governments (Federal Law No. 40-FZ, 2010, see: Government of the Russian Federation 2010).

Let us look briefly at each of these authorized tools.

Federal Subsidies (Grants)

A key part of the tool kit put in place to implement government–nonprofit cooperation is a series of government grants. Two such programs were enacted by a Government Decree issued in August of 2011 (Decree No. 713, 2011, see: Government of the Russian Federation 2011a) and are managed by the Ministry for Economic Development (MED). One of these provides federal subsidies to regional governments to extend the reach of regional programs supporting NPOs. The second establishes a program of federal subsidies provided directly to nonprofit organizations in support of efforts to improve the overall operations of Russian NPOs.

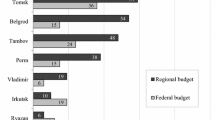

The program of federal subsidies to regional governments is designed to support regional programs of support to NPOs. Regional authorities are invited to apply for this support; applications are considered on a competitive basis by MED and experts it recruits to help with the process. The first round of the competition was held in 2011 (Shadrin 2014, pp. 6–7). Forty-nine out of 52 applications by regional governments received federal support and 600 million rubles (US$18.2 million) of federal funding were disbursed. The next round was held in 2013. In 2013–2014 federal co-funding amounted to 1290 million rubles (US$39.0 million). In 2013, 69 regions applied and again 49 were supported, and in 2014, there were 71 applicants and 45 winners. Since a condition of support is evidence that the regions are utilizing their own resources to support NPOs, MED has an incentive to provide support to the widest possible array of regions in order to stimulate regions to support NPOs. This strategy seems to be working as the number of Russian regional administrations establishing their own programs of support for NPOs increased from 7 regions in 2010—the year before MED launched its co-funding program—to 71 (out of 85) as of 2014 (Shadrin 2014, p. 7).

The subsidies going directly to NPOs are also administered by the MED on a competitive basis. Eligible to participate are NPOs proposing projects aimed at providing information assistance, consultation, and technical support to other NPOs, including projects aimed at training organizations in how to attract volunteers and at the collection, analysis, and proliferation of best practices among NPOs. This combination of capacity-building assistance to support organizations and financial support to operating organizations through the regions is an especially noteworthy feature of the new Russian NPO support program, acknowledging the government’s responsibility to improve not just the financial ability of NPOs to assist in the delivery of social services, but their technical capability as well. According to MED, in 2012–2014 a total of 1736 nonprofit organizations applied for these capacity-building grants and 139 applications were supported. The total subsidies disbursed through 3 years of competition amounted to 694.5 million rubles (roughly equivalent to US$21 million at the exchange rate in effect in the 2011–2014 period)Footnote 4 (Shadrin 2014, pp. 14–15).

Another federal decree (Decree No. 2553, 2012) opened an additional window of support to Russian NPOs, this time through the Ministry of Labor and Social Support. Under its “social support of citizens” initiative, this Ministry was also granted authority to launch a program of “Increasing the effectiveness of government support of socially-oriented NPOs” delivering social services to citizens (Ministry of Labor and Social Support 2012). The amount of funding earmarked for this grant program for the period 2013–2020 was 13,482 million rubles (US$408 million), though the amount actually committed in the initial years (2013–2014) was considerably below this. On the other hand, however, the Ministry of Labor operates two other grant programs delivering assistance to NPOs: “Accessible environment”—a program supporting initiatives of associations of people with disabilities—and another supporting NPOs giving help to children in difficult life situations. The total grant budget of the Ministry of Labor and Social Support amounted in 2013–2014 to 6482 million rubles (US$196.4 million).

The grant tool is also utilized in another program of direct grants to Russian NPOs that was created in 2010 and is run out of the Presidential Administration, the so-called “Presidential grants to NPOs for the implementation of socially important projects.” Presently, six umbrella NPOs have been selected by the Administration of the President to run this program. These umbrella organizations then manage open grant competitions among Russian NPOs. The amount of funds disbursed by way of this tool grew from 1 billion rubles in 2010 (US$30 million) to 3.7 billion rubles in 2014 (US$112 million) (President of the Russian Federation 2010–2014).

Taken together, a small “cottage industry” of grant programs providing assistance to Russian NPOs has thus blossomed in Russia in recent years. As noted in Table 3 below, in 2014, no fewer than seven different Russian Federal Ministries or Agencies were involved in the operation of these subsidy grants to NPOs. These programs delivered a total of 10.3 billion rubles (US$311 million) of assistance to Russian NPOs in 2014 alone—a more than two-fold increase over the 4763.1 million rubles (US$144.3 million) delivered 2 years earlier when the NPO tool kit was launched in earnest (Shadrin 2014, p. 5). The harsh economic and budgetary circumstances resulting from the collapse of the market for the natural resources on which Russia’s economy and government budget have come to depend has halted this growth for the foreseeable future, however.

Purchase-of-Service Contracting

Grants are perhaps the most attractive tool through which NPOs can receive government support since, at least in theory, they reach organizations directly, are designed to support activities that the NPOs want to carry out, and tend to have fewer constraints attached to them (Salamon 2002, pp. 25–27). However, governments around the world have also utilized the tool of contracting. Traditionally, this tool has been used to purchase goods and services that government agencies need for their own operations (e.g., supplies, equipment, facilities, military hardware). Increasingly, however, governments have utilized the contracting tool to purchase services it wants to deliver to citizens (e.g., health care, day care, nursing home care). Such “purchase of service contracting” has its own peculiar operating procedures, demands, and challenges but also allows governments to tap the capabilities and skills of other societal actors, of which nonprofit organizations have been particularly prominent (de Hoog and Salamon 2002, pp. 319–339).

Theoretically, equal access to government and municipal contracts for organizations irrespective of their legal form or form of ownership was established in Russian laws governing contracting since 2005. However, the specific provisions regulating the administration of tenders of the Federal Law No. 94 “On Placing Contracts for Goods, Works and Services Required by State and Municipalities” disfavored NPOs. Implementation of these provisions resulted in government and municipal funds earmarked for social services going almost exclusively to government-owned institutions across the social service fields of health, education, and human services alike.

An attempt to correct this discriminatory situation was introduced in Federal Law No. 44-FZ of April 5, 2013 “On the Federal Contract System in the Area of Procurement of Goods, Works and Services Required by the State and Municipalities” (Government of the Russian Federation 2013). As of January 1, 2014, the law requires all levels of governments to contract with small businesses and “socially-oriented” nonprofit organizations (SONPOs) for at least 15 % of the total annual value of contracts. The value of a single contract falling under this provision is set at up to 20 million rubles (slightly above US$600,000). The 20 million ruble limit actually covers the bulk of typical government contracts for diverse social services.

Free or Reduced Cost Access to Office Space

In addition to providing financial support, governmental units in Russia have deployed another resource that may be uniquely available to formerly socialist countries: access to state-owned real property for free or at reduced cost.Footnote 5 Enacted by government Decree No. 1478 of December 30, 2012, this Decree obliges government agencies to compile, maintain, update, and publish lists of nonresidential properties owned by the Federal government that can be leased out to SONPOs on a long-term basis for free or at rents up to 50 % of the going market rate. The Decree specifies the criteria and procedures to be used in the selection of NPOs to be given access to long-term leases of such property, as well as applicable restrictions on the use of such property and safeguards against mismanagement and corruption. It also encourages regional and local governments to introduce similar norms and regulations to increase the supply of office space for SONPOs from the stock of properties owned by regional and local governments.

The Decree pays particular attention to ensuring transparency and competitiveness in the process of transferring property rights to NPOs. MED has prepared guidelines for regional and local governments detailing the design of procedures that these governments can utilize to issue their own regulations in compliance with the letter and spirit of the Federal Government Decree (Ministry of Economic Development 2013a).

Tax Incentives

Tax incentives, also referred to as “tax expenditures,” have been a favored tool through which to deliver benefits to particular constituencies, especially in the current era of fiscal austerity. Unlike outright grants or contracts, tax expenditures deliver their benefits by allowing particular classes of taxpayers to avoid taxes that would otherwise apply to them. Russia set the stage for the use of this tool to assist NPOs through its prior tax treatment of such organizations and their clients and donors. For example, under Russian tax law, NPOs that receive fees for the services they provide, even if these services are clearly within the missions of the organizations, such as providing education or delivering day care, must pay taxes on these fees at the same rates as for-profit firms. Defenders of this provision point out that without it thousands of for-profit companies might quickly re-organize as nonprofits since the enforcement of Russian prohibitions on the nondistribution of profits by nonprofits tends to be extremely lax, which would allow the businesses to run their companies as nonprofits, escape taxation, and still collect profits (Jakobson 2012). Also particularly painful for organizations supporting the most needy was the treatment of charitable donations made to such people, even in the form of food or clothes, as income liable to personal income tax, which neither the recipient, nor the nonprofit organization, knew how to pay. Similarly, prevailing law required recipients of social services provided by NPOs to pay value added taxes (VAT) on these services even if the service was free of charge for the recipient and funded through donations. During the period from 2011 through 2013, however, a variety of reforms was introduced into the tax regime applicable to NPOs (Ministry of Economic Development 2013b).

A major goal of these provisions was to improve the income side of NPO operations by encouraging charitable giving, the building of endowments, and fee-for-service activities. Among the provisions put in place in pursuit of this goal were the following:

-

A provision allowing individuals to deduct from their taxable income, up to a maximum of 25 %, the contributions they make to NPOs (including religious organizations) in support of their mission-based activities. Under consideration by the Russian Government is a further provision that would allow an individual to transfer the right to reclaim the tax rebate to the recipient NPO. This would free the individual donor of the associated administrative burden and make mass fundraising campaigns more attractive for NPOs;

-

An extension of the types of expenditures NPOs can treat as valid costs in calculating their taxable income and hence the tax it owes;

-

Permission for NPOs to accept securities and real estate as charitable contributions to their endowments; and

-

Waivers on VAT obligations on NPO costs for a wide assortment activities, such as providing care services to the ill the elderly, or the handicapped who are officially considered in need of such services by federal health care/social institutions; providing social services to support children, handicapped, and elderly people in a difficult life situation; organizing and delivering mass physical culture events; transferring property rights for a charitable purpose; and conducting social advertising campaigns.

Other changes to the tax regime affecting NPOs were aimed at reducing the cost side of NPO balance sheet. Included here were the following:

-

Waiver of personal income taxes on charitable donations provided to individuals;

-

Elimination of personal income taxes on any income received from NPOs by orphans, children without parental care, or children living in families with per capita income not above the legal subsistence level;

-

Elimination of personal income tax on reimbursements of a variety of costs related to volunteer work, including accommodation, transfers, medical insurance, individual protection costs, and meal costs up to a specified limit;

-

A 20 % reduction in rates of mandatory social insurance paid by NPOs that have chosen to use the simplified taxation system, provided they comply with established restrictions related to the kinds of eligible activities and sources of funding; and

-

Waiver of property tax obligations on assets, other than real estate, acquired by NPOs after 2013.

Capacity-Building

In addition to financial and in-kind support tools, the new NPO tool kit also includes some direct capacity-building assistance utilizing the tool of information. Thus, for example:

-

A portal on the internet administered by MED contains a section on SONPOs that contains a wealth of information on the activities of the Government aimed at supporting NPOs, on the volunteer movement, and on the development of civil society in Russia. This includes laws, norms, regulations (both acting and planned), analysis, information on competitions for direct financial support, methodological recommendations, and model regulation acts. The information helps both NPOs and regional and municipal governments connect to the available programs and is intended to speed up the dissemination of best practices of government support tools across the country. Work to equip regional governments to supply similar information on their websites is also under way.

-

In 2012, MED sponsored the development and launch of a training program aimed at developing cooperation skills for NPO staff and volunteers and public servants working for agencies and departments in charge of NPO support programs or in charge of the delivery of social services. Designed by HSE, the training program is delivered by the Russian Presidential Academy of the National Economy and Public Administration. The Academy is well represented in Russian regions, and the training courses are tailored both for in-class delivery and for online distance training so that the program is readily accessible across the country. The training program is government licensed to count as an official skills improvement course, which allows regional and municipal governments to use public funds to pay for the participation of their employees, thus ensuring a degree of financial sustainability.

Regulation

Side by side with the promotional activities associated with the new Russian NPO tool kit has come another set of programs that utilize the tool of regulation. Regulation, of course, is one of the most coercive tools in the government tool kit. It is used typically to restrict actions, though it can also be used to draw distinctions among classes of actors considered eligible for certain benefits or forms of activity. The launch of the Russian NPO tool kit was accompanied by at least three uses of the tool of regulation. Below, we first describe one instance of regulation drawing distinctions within the sector, which carved out a subsector of socially oriented NPOs eligible for the tool kit benefits. Then we discuss the two measures mentioned earlier that impose restrictions on various classes of NPOs.

-

Carving Out Socially Oriented NPOs An early regulatory provision of the NPO tool kit took the form of a regulation defining the sub-class of NPOs that would be considered eligible to access the various benefits that the tool kit offered. For this purpose, Article 31.1 of Federal Law No. 40-FZ of April 5, 2010 (Government of the Russian Federation 2010), carves out a sub-class of NPOs called “Socially-Oriented NPOs,” or SONPOs in English, that alone are considered to be eligible for most of the benefits outlined in the rest of the NPO tool kit. The act first excludes from eligibility nonprofits that are not covered by the key Russian law on nonprofits, the Federal Law No. 7-FZ of January 1, 1996 “On Nonprofit Organizations” (Government of the Russian Federation 1996). This makes ineligible consumer cooperatives, homeowner societies, government institutions, government corporations, autonomous institutions, and political parties.

The law then further limits eligibility for socially oriented status by defining the charter purposes of the remaining NPOs that the lawmakers considered to be of particular public benefit. Among such charter purposes are the following:

-

(1)

Social support and social protection of citizens;

-

(2)

Activities aimed at preparing the population to overcome the consequences of natural disasters, environmental or technogenic accidents, or at preventing such accidents;

-

(3)

Aid to victims of natural disasters, environmental, technogenic, or other accidents, aid to victims of social, national, or religious conflicts, refugees, and involuntary migrants;

-

(4)

Environmental protection and the protection of animals;

-

(5)

Protection of artifacts (including buildings and constructions) and territories of particular historic, cultural, religious, or environmental value, including places of burial;

-

(6)

Legal aid provided free of charge or at reduced fees to citizens and nonprofit organizations, legal education of the population, protection of human rights, and civil liberties;

-

(7)

Prevention of socially dangerous behavior patterns of citizens;

-

(8)

Philanthropic activities as well as activities to facilitate charity and volunteering;

-

(9)

Activities in education, research, culture, arts, health care, disease prevention, the promotion of healthy life styles and of physical culture, activities to improve the moral and psychological condition of citizens, as well as support for the above activities, and facilitation of spiritual development of the individual.

Subsequent to the initial legislation, the Parliament added a number of additional categories of NPOs eligible for the special SONPO categorization. Included here were organizations combatting corruption, protecting national culture, promoting patriotism and military-patriotic education, fighting forest fires, honoring unknown soldiers, and promoting labor mobility (Federal Law No. 325-FZ of December 30, 2012; Federal Law No. 172-FZ of July 2, 2013; Government Decree No. 21-84p of November 3, 2014).

To adjust for the diversity of regional and local features of the Russian social sphere, as well as to facilitate co-sponsoring of the support measures for NPOs from regional and local government budgets, the law identifying SONPOs leaves the list of eligible SONPO activities open-ended. It includes a provision for expanding the list of activities aimed at solving social problems and at the development of civil society in Russia through regional legislation and by adopting corresponding norms and regulation by local (municipal) governments.

As of 2012 the Russian statistical agency—Rosstat—reported the population of Russian SONPOs to number 113,327 organizations. This means that roughly half of all actively working Russian NPOs are in a position to apply for government funding.

-

The Foreign Agent Law The second significant regulatory program relating to NPOs enacted within the time frame of the other NPO tool kit proposals was Federal Law No. 121-FZ of July 20, 2012 (Government of the Russian Federation 2012), entitled “On Introducing Amendments to Selected Legal Acts of the Russian Federation Related to the Regulation of Activities of Noncommercial Organizations Performing the Functions of Foreign Agents.” Unlike the other major provisions of the NPO tool kit, this widely criticized regulatory provision establishes a particularly discriminatory distinction among legal NPOs. In particular: “Any Russian nonprofit organization that receives financial resources or other goods from foreign states, their agencies, international or foreign organizations, foreign citizens, stateless persons or their representatives, or from Russian organizations receiving funds from those sources, and which takes part, particularly in the interests of foreign entities, in political activity within the territory of the Russian Federation” are required to register officially with the Justice Ministry, publish a half-yearly record of their activities, and indicate their status as a “foreign agent” on their documentation.

The law created a “Register of Non-profit Organizations Fulfilling the Function of Foreign Agents” to list those organizations receiving foreign money and participating in political activities in Russia. These groups have to inform the federal authorities of the amount of funds received and their use. After being registered, they have to inform the authorities in advance of their participation in any political activity (i.e., any activity likely to influence the decision-making of state agencies or influence public opinion). The law also stipulates the auditing of the accounts of organizations registered as “foreign agents.” For those that refuse to register as such, the law requires the cessation of their activity for 6 months. Organizations under such restrictions can only resume functioning once they have registered as foreign agents. If a group refuses to comply with the law, it is subject to a fine of up to 500,000 rubles and its officers risk a sentence of up to 2 years in prison.

The act explicitly excludes from the foreign agent status “noncommercial religious organizations, government corporations, any noncommercial organizations established by government or government corporations, as well as ‘budgetary institutions’” (government-owned schools, research centers, clinics etc.). Also excluded are employers’ associations, such as trade and industry chambers.

The definition of the “political activity” that makes an organization eligible for coverage by this law is quite broad, including taking part in “organizing and implementing,” including “funding,” actions aimed at “influencing governmental decision-making with the purpose to achieve changes of government policy” as well as “actions aimed at forming public opinion to achieve the above purposes.” Although the act excludes from coverage such actions in particular policy spheres—such as science, culture, the arts, public health, and social supportFootnote 6—the language remains highly ambiguous and apparently open to wide interpretation.

-

“Undesirable” Organization Law A third regulatory provision, passed on second reading in the Russian Duma in May 2015 and signed by President Putin on May 22, 2015, allows authorities to deem foreign NGOs “undesirable” and shut them down. According to the Law, prosecutors would be able to label some foreign organizations undesirable if they pose “a threat to the foundation of the constitutional order of the Russian Federation, the defense capability of the country, or the security of the state.” Not only the organizations, but anyone working for these blacklisted groups could face steep fines or jail terms of up to 6 years. The Law would also apply to Russian organizations that receive funding from and cooperate with such foreign groups. The Ministry of Justice will be responsible for keeping the list of “undesirables” (Federal Law of May, 23, 2015 No. 129-FZ, see: Government of the Russian Federation 2015).

Part III. Explaining the Result

How can we explain this curious combination of promotion and persecution of Russian NGOs? To what extent can this result be attributed to the Rational Actor model and to what extent is it possible to see in the results the workings of the other two models introduced earlier?

The answers to these questions are of more than academic interest. They have practical implications as well for how we assess the true intents of the Russian government toward the nonprofit sector and hence the likely prospects for this set of institutions and for the support programs recently put in place to assist them. At the same time, however, without fuller access to the inner workings of the Russian government, it is impossible to answer these questions definitively. What is possible is to venture some reasonable suppositions based on the limited evidence available, and that is what we will do below.

Our central conclusion is that Allison’s (1969, 1971) fundamental insight into the disjointedness of policy decision-making in complex governments applies to Russian policy toward NPOs. Russian governmental policy toward NPOs can thus fruitfully be seen as a series of only partially inter-connected decision processes, each of which has its own dynamics, and each of which therefore potentially fits a different one of the analytical models that Allison articulates. It is therefore important analytically to deconstruct the overall policy into its separate policy streams and see how far each of the models takes us in explaining what is going on. In what follows, we therefore take a series of separate “cuts” at explaining features of the observed policy as we have described it to see if we can come to a more nuanced explanation of the true dynamics that may be at work. We begin with the Bureaucratic Politics model.

First Cut: The Bureaucratic Politics Model

Certainly, from the evidence at hand, it seems reasonable to see in at least the early formulation and execution of the NPO tool kit program the workings of the Bureaucratic Politics model, with its emphasis on multiple nodes of policy initiative pursued by various policy entrepreneurs through the fairly structured policy clearance processes that Fortescue (2010) argues convincingly characterize the Russian governmental system as they necessarily do of any complex society. In fact, the impetus for the reforms that ultimately led to what we have termed the “tool kit” of NPO support programs began early in the post-Soviet period and was among the core features of the so-called “Gref program” of 2000 calling, among other things, for a major reform of the social welfare system inherited from the Soviet past (Wines 2000). The Gref program “… mapped in some detail a re-orientation of the state’s role from directly providing social welfare to constructing, overseeing, and in some cases subsidizing the institutional mechanisms for private and other non-state provision, including mortgage and health insurance markets and educational voucher schemes,” signaling the potential advent of third-party government in Russia (Cook 2007, p. 154).

The justifications for these reforms were clear to many in the policy community. The democratic transformation after 1991 went side by side with market reforms that were accompanied by a drastic deterioration of standards of living for many Russians. The government at that time balanced on the edge of default, defaulted on many of its social obligations, and failed to enforce social protection laws. At the same time the post-Soviet transformation opened the door to a great variety of civic initiatives, calling into life new-style nonprofit institutions with a potential to improve social service provision.

However, this reform urge stalled as the growing price of oil at the beginning of the millennium allowed for abundant fiscal resources, and cooled the pressures for major reforms. It took the global financial crisis of 2007–2008 to allow government officials responsible for the social sector to get the reform process back on track and to attract the attention of political leadership to the fact that, by the mid-2000s, the ineffective system of social services inherited from the Soviet era still remained largely unreformed—despite considerable efforts spent on reform designs and various experiments. Persistent evidence of popular dissatisfaction with the unreformed human service delivery system doubtless strengthened the reformers’ hand. For example, despite an almost doubling of general government expenditures devoted to the “social sphere” between 2006 and 2009, representative population surveys conducted by the Center for Civil Society and the Nonprofit Sector Studies of the Higher School of Economics in 2008 showed that less than 10 % of Russians believed that the branches of the social sphere—including education, healthcare, research and development, culture, and social welfare services—were in “good shape.” Forty percent of Russians said these sectors were in “bad condition,” with another 40 % believing that they were in more or less “satisfactory shape.” Health care and social welfare (i.e., the pension system for the most part) fared worst in the survey with 53 and 56 % of respondents, respectively, rating these sectors as in “bad condition” (Jakobson and Mersianova 2012).

While the majority of Russian citizens remained firmly committed to state paternalism as a necessary and highly desirable feature of a distinctive Russian path to development, most remained deeply dissatisfied with the practical work of government agencies. Thus, 74 % of Russian citizens told Levada Center interviewers that “most people will not be able to survive without tutelage from the state” (up from 72 % in 1997), but only a minority considered that in Russia “the state lives up to its obligations to the citizens” (a meager 5 % in 1998 at the height of the economic crisis, and a more respectable but still highly limited 30 % in 2014) (Levada Center 2014, p. 46). Special sources of public dissatisfaction were “state” services in the fields of health care, education, and social care, which in Russia up to this date remained almost exclusively in state hands.

Beyond that, Russian policy makers were also quite aware that although the Russian population predominantly continued to hold the government responsible for the delivery of social services, sizeable segments were not at all averse to engaging private donors and independent charitable organizations in providing relief to the needy. According to the results of one such survey, 77 % of Russians felt it important to hold “government institutions” responsible for helping people who are considered “socially vulnerable.” However, a sizeable 30 % of them believed that such help should come as well from “local charitable organizations and foundations,” and 21 % thought that “major companies and businessmen” should help. According to the same survey, 44 and 42 % of the Russian population believed, respectively, that “wealthy people” and “Russian independent charitable organizations” should be engaged in philanthropy (Mersianova and Jakobson 2010).

Against this background, it is not surprising that researchers at the National Research University Higher School of Economics found through the Russian Civil Society Monitoring Project survey that 76 % of Russians expressed the wish that nonprofits take an active part in the resolution of social problems, e.g., exercise control over public institutions providing health care or educational services, or provide such services themselves. At the same time, public opinion favored cooperative interaction between nonprofits and the authorities in the solution of social problems—an attitude shared by more than half of the respondents.

As a result, alert Russian policy makers and advocates of the need for change found themselves mid-way through the first decade of the new millennium in very much the same position as their counterparts in France 13 years earlier—facing a citizenry still committed to a strong state role in the provision of social welfare services, but increasingly frustrated by the quality and responsiveness of the system through which those services were being delivered (Ullman 1998; see also: Archambault, this volume). And they responded in much the same way as did progressive French leaders of the early 1980s—by advocating a modernization of the delivery system for social welfare services through cross-sectoral cooperation with NPOs—thereby reaching out to capture some of the innovativeness and responsiveness, not to mention access to resources, of the nonprofit sector without surrendering the leading role of the state in financing responses to social ills. Work on such reforms began in the Ministry of Economic Development 2006 in response to a presidential decree instructing the government to elaborate a long-term (2008–2020) national strategy of social and economic development (Ministry of Economic Development 2008).

It turns out, moreover, that leaders of service-providing nonprofit organizations were more than happy to support such interaction with the state, even if this involved some limitation on their involvement in advocacy activity. One reason for this, of course, was the strained economic circumstances of most Russian NPOs, which made the prospect of meaningful government assistance highly attractive. The share of organizations avoiding any kind of cooperation with authorities on ideological or political grounds is therefore small. Even human rights organizations, such as the Moscow Helsinki Group, or Memorial, have applied for and received government grants awarded under the auspices of the Presidential Administration. Sociological data gathered in the course of the Russian Civil Society Monitoring Project suggest that most leaders of NPOs have at most a passing interest in political change. Exemplary are answers to the question: “If there is a change of political regime in the country in the near future, will such change favorably affect an organization like yours?” Only 4 % of respondents answered “yes” to this question, another 12 % answered “probably yes.” “No” or “Probably not” were the answers of 38 % of respondents, while the largest group of respondents—46 %—had no specific opinion. Therefore, it is not surprising that a typical Russian NPO is prepared to cooperate with authorities and develops such relationships based on very pragmatic considerations, rather than on ideological grounds.

This has been confirmed, moreover, by representative surveys of nonprofit leaders carried out in recent years by the Center for Studies of Civil Society and the Nonprofit Sector at the NRU HSE as part of Russian Civil Society Monitoring. According to the results of the most recent of these empirical studies,Footnote 7 52 % of surveyed Russian NPOs indicated their readiness to cooperate with authorities in designing and implementing socially important programs. Indeed, substantial proportions of NPOs indicated that they already had some experience of interaction with authorities, at least at the local level.

By late 2009, the basic outlines of the NPO tool kit had thus cleared the internal hurdles and secured a place in a pivotal Presidential Address on September 10, 2009, that endorsed a substantial program of initiatives to engage NPOs and foster closer government–nonprofit cooperation (Medvedev 2009).

Further support for the Bureaucratic Politics explanation for the shape of evolving Russian governmental policy toward nonprofits can be found in the basic structure of the resulting new initiatives. The telling fact here is that the government did not create a coherent single center for dealings with SONPOs so as to concentrate resources and expertise, minimize administrative duplication, and formulate a coordinated approach. Instead, what we earlier termed a “cottage industry” of separate programs was scattered across seven different federal ministries and agencies, each of which proceeded to put its own spin on program operations. This suggests the need for advocates of this strategy to find allies in the different ministries in order to move their agenda ahead. And what better way than to cut them into a share of the action by giving them resources through which they could play in the new policy approach. Lending further credence to this line of argument is the fact that the pivotal “concept document” that put the government officially on record in support of something like the NPO tool kit bore the name “A Concept to Facilitate the Development of Charitable Activities and Volunteering,” suggesting the need to win the support of the Ministry of Finance by emphasizing the savings this concept would bring to the government budget by stimulating greater charitable support and reliance on volunteers instead of paid government personnel to address social welfare problems.

Second Cut: The Rational Actor Model

Convincing though the Bureaucratic Politics explanation of the evolution of Russian government policy toward nonprofits may be, it may not account for the full story. On the surface, at least, a stunning contradiction seems to exist between the carefully structured decision process leading up to the new initiative of state support for NPOs and the sharp turn toward stigmatization and repression of certain internationally funded nonprofit groups, and the likely collateral damage to the reputations of a much broader portion of the nonprofit community, represented by the “foreign agent law.”

How can we explain this apparent contradiction? In the absence of inside information, we can ultimately only speculate on the possible answers to this question and see what the limited information available suggests about which of these answers seems most plausible.

Perhaps the most obvious answer is the one advanced by observers who begin with the Rational Actor model but forget Allison’s caution about deconstructing complex government actions and analyzing their component parts separately. We can refer to this as the “all-or-nothing” form of the Rational Actor model. Those who espouse this view challenge the idea that there is any contradiction at all between these two strands of policy or conveniently overlook, or downplay the significance of, the NPO tool kit set of programs and focus only on the regulatory dimensions of Russian government policy toward NPOs. In this view, the support programs represent, at best, just one prong of a two-prong effort to co-opt the Russian nonprofit sector by effectively restricting the sector’s access to sources of support outside the regime’s control while using local resources to draw the more pliant service-oriented organizations closer to the governing authorities.

Such a strategy certainly seems consistent with some of the available evidence. Indeed, the notion of splitting the Russian nonprofit sector into acceptable and unacceptable components, and rewarding the one while penalizing the other, was already evident well before the new NPO tool kit was assembled. In his address to the Federal Assembly on May 26, 2004, for example, President Putin outlined the rationale for this strategy, noting that:

In our country, there are thousands of public associations and unions that work constructively. But not all of the organizations are oriented towards standing up for people’s real interests. For some of them, the priority is to receive financing from influential foreign foundations. Others serve dubious group and commercial interests while the most acute problems of the country and its citizens remain unnoticed. I must say that when violations of fundamental and basic human rights are concerned, when people’s real interests are infringed upon, the voice of such organizations is often not even heard. And this is not surprising: they simply cannot bite the hand that feeds them. Of course, such examples cannot become for us a reason to accuse citizens’ associations wholesale. I think, such inevitable charges are of temporary character (Putin 2004).

The link between suppression and support then seemed to be drawn more directly in a 2012 statement in which the president noted that: “As far as nonprofit organizations are concerned, I agree with those colleagues who consider that if we introduce harsher working frameworks for these organizations, we should obviously increase our own financial support for their activities” (Putin 2012b). In other words, the support programs seem portrayed as ways to support the policy of de-politicization and elimination of troublesome outside funding.

Another potential source of support for this all-or-nothing Rational Actor interpretation can be found in the record of financing of the new NPO tool kit initiatives. In a word, as a share of Russian federal government expenditures on the social sector, including health, education, physical culture and sports, and social policy (but excluding pensions), spending on government support of NPOs in 2012 barely amounted to a rounding error—4.7 billion rubles out of a total of 2.5 trillion rubles of social sector spending—or less than 2/10ths of 1 percent.Footnote 8 The record of government support seems more robust when compared to the overall spending of the NPO sector, but at about 15 % it falls well below the 41-country average estimated by the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project (Mersianova et al. 2016, forthcoming), leaving Russian NPOs well behind even some of their Central European cousins in terms of the extent of their government support. Viewed through the lens of the all-or-nothing version of the Rational Actor model the NPO tool kit could thus be viewed as merely a symbolic initiative intended to distract attention from the real government effort to crack down on nonprofits, cut off alternative sources of funds, and tie organizations to funding streams more firmly under government control.